The past two decades have seen remarkable advances in our abilities to treat and prevent stroke. Better vascular risk factor control has lead to a decrease in stroke incidence by 50% since the early nineties [1]. Improvements in acute stroke care, especially at specialized centers, have led to a decline in overall stroke mortality. Over the past decade, the stroke death rate in the US decreased by one third, and stroke has moved from the third to the fifth leading cause of mortality [2]. If a patient with an acute ischemic stroke presents early enough to the hospital, systems should be in place to appropriately administer tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) within less than an hour of arrival, thereby often doubling their chances of achieving future independence [3, 4]. Some patients may continue on to the angio-suite for mechanical clot retrieval; those who do are two times more likely to be independent at 3 months [5-7].

Despite these remarkable advances, only around 5-7% of patients with acute ischemic stroke receive tPA [8, 9]. Mechanical thrombectomy is reserved for an even smaller proportion. Whereas community education may increase the proportion of patients calling for help sooner [10] and mobile CT scanners and pre-hospital treatment may shorten the time and increase the proportion of patients receiving tPA [11], for most patients, stroke remains disabling and often deadly. For these reasons, palliative care remains an important part of the stroke care that we deliver, especially for patients with severe stroke.

Here we provide a contemporary review of the literature and offer some recommendations on how stroke providers may integrate palliative care into the care of their patients with severe ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke, focusing on early interactions. Stroke palliative care is fundamental to high quality stroke care and needs to be a core component of our research as well as residency and fellowship training.

Palliative Care

Palliative care is an approach to medical care for patients with serious illness. It includes end-of-life and hospice care, but is much broader. Palliative care is not limited to those with a terminal prognosis, but rather is appropriate at any age and at any stage of a serious illness [12]. Palliative care focuses on improving communication about goals of care and maximizing comfort and quality of life of patients and families through the identification, prevention and relief of pain and suffering in body, mind and spirit (Table 1). The past decade has seen a remarkable growth in palliative care; the number of palliative care teams within US hospitals with 50 or more beds has nearly tripled to over 60% since 2000 [14].

Table 1. Definition of Palliative Care.

“Palliative care generally refers to patient and family-centered care that optimizes quality of life by anticipating, preventing, and alleviating suffering across the continuum of a patient's illness. Historically, palliative care referred to treatment available to patients at home and enrolled in hospice. More recently, palliative care has become available to acutely ill patients and its meaning has evolved to encompass comprehensive care that may be provided along with disease-specific, life-prolonging treatment. End-of-life (EOL) care refers to comprehensive care for a life-limiting illness that meets the patient's medical, physical, psychological, spiritual and social needs. Hospice care is a service delivery system that emphasizes symptom management without life-prolonging treatment, and is intended to enhance the quality of life for both patients with a limited life expectancy and their families”. (National Quality Forum [13])

| Primary Stroke Palliative Care Skills | |

|---|---|

| Pain and symptoms | Recognize early signs of pain, depression, anxiety, delirium Basic symptom management skills |

| Communication skills | Communicate with empathy and compassion Authentic and active listening Narrative competence to elicit the patient's story Effectively elicit individual treatment goals (see Goals of care) Effectively share information with the patient and family using terms they understand Communicate prognosis for quantity and quality of life Provide anticipatory guidance regarding illness and treatment trajectories Develop consensus for difficult decisions in a way that is sensitive to the patient's/family's preferred role of decision-making Identify and manage moral distress among interdisciplinary team members |

| Psychosocial and spiritual support | Identify psychosocial and emotional needs of patients and families Identify needs for spiritual or religious support and provide referral Access resources that can help meet psychosocial needs Practice cultural humility |

| Goals of care | Help family establish goals of care based on patent and family values, goals, and treatment preferences Willing and able to engage in shared decision-making and adapt shared decision-making approach to patient and family preferences Incorporate ethical principles In communication and decision-making |

| End-of-life care | Emphasize nonabandonment and provide continued emotional support through the dying process for patents and their families Provide anticipatory guidance regarding the dying process for patients and their families Facilitate bereavement support for family members |

The broad scope of palliative care and the complex and multifaceted needs of patients and their families require an interdisciplinary team of health professionals including physicians, nurses, therapists, pharmacists, spiritual care providers, social workers and others. Effective communication is fundamental to this team approach.

Multiple professional societies endorse the importance of early integration of palliative care into the care of critically or seriously ill patients [15], and the recent AHA/ASA guidelines for the management of stroke patients emphasized the importance of integrating palliative care into the general care of these patients [16]. Early involvement of palliative care specialists in the cancer setting has been associated with improved quality of life, symptom control, increased patient and caregiver satisfaction, more appropriate health resource use, health care savings, and even improved survival [17, 18]. However, palliative care is neither standardized nor established in the acute stroke setting, and guidance is lacking as to the best way to integrate palliative care specialists.

Palliative Care and Stroke in the Literature

Palliative care needs after stroke are common and substantial [16, 19-21], but the literature is scarce on the exact nature as well as the best methods to identify and manage these needs post-stroke. The literature on palliative care and stroke focuses largely on end-of-life care and dying with an emphasis on symptom control for the dying and support for family members as they grapple with difficult decisions and bereavement [19, 22, 23]. Only few studies have explored palliative care needs of hospitalized stroke patients who are not actively dying, mostly by examining the clinical characteristics of the subset of stroke patients seen by palliative care specialists [19, 24-26]: Compared to non-stroke patients receiving palliative care consultations, stroke patients are more often referred to palliative care for end-of-life decisions and less often for symptom management [24, 26]. Stroke patients seen by palliative care specialists are also more functionally impaired, less likely to have decision-making capacity, and more likely to die in hospital [24]. In addition, many stroke patients and their caregivers report a need for more information about prognosis [27]. One narrative review identified a large knowledge gap regarding specific palliative care needs of stroke patients and calls for “collaborative research between professionals in specialist palliative care and the stroke communities” [21]. Finally, the recent AHA/ASA guidelines on palliative and end-of-life care in stroke provides a detailed overview for stroke providers on palliative care skills such as communication techniques, goal setting, decision-making, symptom management and end-of-life care, and emphasizes the importance of palliative care provided at the same time as other evidence-based stroke treatments [16].

Integration of Primary and Specialist Palliative Care

Palliative care is provided by multiple members of the interdisciplinary care team. As the role of palliative care has expanded and the demand for early palliative care is increasing across the spectrum of serious illnesses, a model has been proposed that distinguishes primary palliative care (skills that all clinicians should have) from specialist palliative care, which is provided by clinicians who are boarded in palliative medicine and are trained in managing more complex and difficult cases [28]. The co-existence of primary and specialist palliative care seems especially relevant for patients with severe stroke where palliative care needs are often influenced by highly-specialized disease-specific prognostication and treatment options and where aggressive restorative therapy must often occur in close proximity with compassionate end-of-life care [29]. In addition, the acuity of presentation for acute stroke may act as a barrier to specialist palliative care involvement. Primary palliative care skills that should be expected from stroke providers and therefore taught to Neurology residents and stroke fellows are listed in table 2. Mastering their primary palliative care skills will serve the stroke team in several ways: it will strengthen their therapeutic relationship with the patient/family and may minimize fragmentation of care; it will sharpen the stroke team's awareness of palliative care needs (for example, symptom management and determination of goals of care) and, in a timely manner, help them recognize unmet needs that may benefit from specialist consultation. As with any consultation service, the timing and the degree to which specialist involvement is required, will depend on what the primary team is able to provide. Palliative care specialists offer an added layer of support to patients, families and clinicians and may be called upon to provide support for management of complex or refractory symptoms, help with the implications of conflicting goals of care, assistance with difficult family meetings, support for transitions towards end-of-life or hospice care, or bereavement support [28].

Table 2.

Primary palliative care skills for the stroke specialist

| Primary Stroke Palliative Care Skills | |

|---|---|

| Pain and Symptoms | Recognize early signs of pain, depression, anxiety, delirium Basic symptom management skills |

| Communication skills | Communicate with empathy and compassion Authentic and active listening Narrative competence to elicit the patient's story Effectively elicit individual treatment goals (see “Goals of care”) Effectively share information with the patient and family using terms they understand Communicate prognosis for quantity and quality of life Provide anticipatory guidance regarding illness and treatment trajectories Develop consensus for difficult decisions in a way that is sensitive to the patient's/family's preferred role of decision-making Identify and manage moral distress among interdisciplinary team members |

| Psychosocial and spiritual support | Identify psychosocial and emotional needs of patients and families Identify needs for spiritual or religious support and provide referral Access resources that can help meet psychosocial needs Practice cultural humility |

| Goals of care | Help family establish goals of care based on patient and family values, goals, and treatment preferences Willing and able to engage in shared decision-making and adapt shared decision-making approach to patient and family preferences Incorporate ethical principles in communication and decision-making |

| End-of-Life Care | Emphasize non-abandonment and provide continued emotional support through the dying process for patients and their families Provide anticipatory guidance regarding the dying process for patients and their families Facilitate bereavement support for family members |

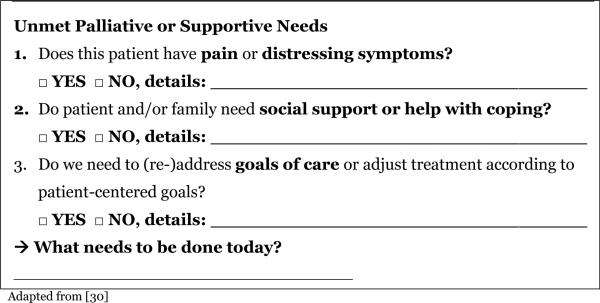

A “simple assessment tool” to identify palliative care needs specific to stroke patients [19, 21] may further enhance the stroke team's primary palliative care. We have developed a daily checklist that screens for palliative care needs as perceived by the clinicians on daily work rounds (table 3). This checklist aids the clinical team in recognizing specific needs and use family meetings or other supporting clinicians such as palliative care specialists, psychologists and others to meet those needs. We were able to show that such a tool encourages the team to consider using family meetings and other supporting clinicians including palliative care specialists to meet patient and family needs [30].

Table 3.

Palliative care needs checklist

|

Palliative Care Specific to Severe Stroke

While palliative care may be applicable to all patients and families with stroke, it is particularly relevant for those with severe stroke. With no agreed upon definition, one way to define “severe stroke” is by the NIH Stroke Scale (NIHSS): for example in the TOAST trial, 12% of all stroke patients had an NIHSS of 16 or greater [31]. Alternatively, severe stroke can be defined as stroke that is not survivable without aggressive medical or surgical interventions, such as intubation and mechanical ventilation or brain surgery, or by the need for long-term institutional care. This definition includes ischemic strokes, as well as intraparenchymal and subarachnoid hemorrhages. One in 10 stroke patients require mechanical ventilation on admission [32], one in 11 patients are discharged from the acute care hospital with a feeding tube [33], and one in 5 patients require institutional care at 3 months after the stroke [2]. Patients with severe stroke, by any of these definitions, are at high risk for early mortality, but also have the potential for considerable recovery and prolonged survival. Among those with prolonged survival, there is often significant disability, morbidity and a number of troubling symptoms [34], suggesting a high degree of palliative care needs. In addition, severe stroke patients often lack the capacity to participate in medical decision-making, requiring the involvement of surrogate decision-makers. These surrogate decision-makers, generally family members, are often placed in the position of assisting with decision-making in the context of substantial prognostic uncertainty and often have their own palliative care needs.

The decision to withdraw life-sustaining treatment is the most common cause of death after acute stroke [35, 36]. Surrogate decision makers actively involved in shared decision-making can experience tremendous stress and this stress – often measured as symptoms of anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder – can be lessened by clinician communication and behaviors [37]. Despite the importance of palliative care for patients with severe stroke, little guidance exists regarding best practices for integrating palliative care into the care of these patients for whom withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment is considered, resulting in dramatic variability in care [38].

Palliative Care Specific to Acute Stroke

The time period immediately after stroke represents an important opportunity for primary palliative care. The first encounter between the stroke team and their patients is typically in the context of a crisis. For many patients, the acuity of neurologic devastation comes with a brief time window for the potential to reverse the injury, forcing an aggressive coordinated approach, and rapid treatment decisions. This fast-paced, chaotic environment is wrought with hope and disappointment, relief and anxiety. As options for thrombectomy, mechanical ventilation, craniotomy or ventriculostomy present themselves, stroke providers need to build a trusting relationship with patients and their families before engaging in shared decisions. Some treatments in the emergency setting may not require consent, but when the optimal treatment option depends on how the patient might value the potential benefits, risks, and consequences associated with those options, effective and compassionate communication is essential. Providing information in the most accurate and sensitive way also requires an assessment of the patients’ or families’ preferred method for receiving information and making decisions. Family members vary as to how detailed they want information about prognosis. In addition, some patients and families desire an active role in the decision-making process, while others prefer that the physicians take more responsibility for decisions [39, 40]. Stroke specialists need basic skills in assessing family members’ preferences and providing sensitive patient- and family-centered communication that incorporates cultural humility and adheres to medical ethical principles (table 2).

Establishing Individual Treatment Goals

In order to identify the most appropriate, patient-centered treatment decisions, an accurate diagnosis of patient preferences is important. Different people place different values on predicted future health states and potential trade-offs. Unfortunately, however, most people do not have a predefined set of preferences specific to each possible outcome, and, even if they do, these preferences are often unknown to their family and physicians. In addition, patients with severe stroke typically lack capacity to participate in medical decision-making. Instead, a patient's preferences need to be explored by gathering information from available sources, including through a narrative approach i.e. by developing the patient's story [41]. Neurologists are highly skilled medical detectives as they ask pertinent questions, recognize important symptoms, and identify specific syndromes. As we integrate primary palliative care into our practice, we need to refine our narrative competence to skillfully extract not only objective information but also the patients’ or their families’ own understanding of this disease, as well as their hopes and fears. Technological progress and economically driven time constraints have spurred clinician's fear of the open-ended question and a tendency to interrupt quickly. But the ability to engage authentically with the patient and family, to listen empathically, and to join with them in their suffering helps build a respectful and efficient partnership between the medical team, who are experts in diagnosing and treating the particular illness, and the patient and their family, who are experts on their own story, as well as their values, goals, and preferences.

Prognosis Communication

Decision-makers appreciate prognostic information early in the course of serious or critical illness, even if this prognostic information is framed with a statement of a high degree of uncertainty [42], yet physicians are often reluctant to provide this information [43]. Because prognostic uncertainty is the rule after stroke rather than the exception [44], stroke providers need to communicate effectively and provide anticipatory guidance regarding possible trajectories and issues that patients and family members may soon experience. Anticipatory guidance helps patients and family prepare for anticipated developments, expect complications and plan for potential decisions that may ensue. It is also important to realize that many surrogate decision-makers rely on multiple sources of information to inform their own view of prognosis, not just the physicians’ estimates [45].

Observational studies and expert opinion provide some guidance for talking about prognosis. It can be helpful to describe the anticipated best case and worst case scenarios at 3 or 6 months after stroke to help frame the potential outcomes. This is congruent with the palliative care model of balancing a “hope for the best” with “preparing for the worst” [46]. When communicating prognosis, the stroke provider needs to customize the amount and type of information to what is relevant and meaningful to this particular patient and family member. By effectively assessing the decision-maker's understanding and exploring the patient's values, the good communicator shares information in a way that encourages participation. The “Ask-Tell-Ask” approach involves asking what the patient or family member understands (Ask) before giving the news and information (Tell) and then assessing what the patient or family member understood (Ask) from the information given [47] (table 4). Genuinely shared decisions develop from curiosity and consensus, rather than negotiation and consent [48]. The skill of the clinician then lies in developing this consensus and being prepared to provide a corresponding treatment recommendation.

Table 4.

An ASK-TELL-ASK example for giving information to a family member of a patient with severe stroke.

| ASK (Stroke Neurologist): Before giving information, the provider explores what the patient or family understand about the illness and treatment and assesses their desire for information. This approach encourages an active dialogue, allows the patient/family to shape the direction of the conversation and helps the provider adjust their information to the individual setting, for example: |

| “What have the doctors told you about what is going on with your loved one and what your loved one's prognosis and treatment options are?” |

| TELL (Stroke Neurologist): After eliciting the patient/family's understanding, the provider frames the information in a way the patient/family understand. Giving a ‘warning shot’ (“I have difficult news for you”), allows the patient/family to prepare emotionally, for example: |

| “I'm concerned as well. I would like to tell you a little more about what I see is likely to happen down the road, and then I would like to review with you some things that we can do (pause to allow family to absorb information.) First, I am worried that she will get worse...” |

| ASK (Stroke Neurologist): The second Ask gives the provider the opportunity to explore how well their information was understood and which points may need more explanation. It is important that this not be perceived as testing the patient/family, but rather to avoid any misunderstandings, for example: |

| “I know that was a lot of new information. Who are you going to talk to about this meeting today? To make sure I did a good job of explaining to you, can you tell me what you are going to say to them?” |

Adapted from [47]

Conclusions

The palliative care needs of patients with severe stroke are immediate and consist of psychosocial support for patient and family, shared decision-making for preference-sensitive treatment decisions, determination of patient-centered goals of care, and pain and symptom management. Early stroke palliative care should be integrated with acute lifesaving and neuro-restorative treatments and should be provided by stroke providers, drawing on the skills of the interdisciplinary palliative care team when these specialists can provide additional support for patients, family members, or clinicians. A narrative approach in the acute setting can be challenging given time constraints, but is essential given the impact that treatment decisions will have on the lives of the patient and their family. Vascular Neurology fellowships need to include palliative care competencies to ensure all providers are proficient in primary palliative care skills (table 2) as well as effective in triaging identified needs to consulting specialties. Rigorous, multi-site evidence-based research is needed to determine best methods for prognosis communication, identifying patient treatment preferences and patient and family preferred roles in decision-making, and individualizing treatment decisions.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Creutzfeldt received support for article research from the Cambia Health Foundation, and the National Institutes of Health (NIH), NINDS Stroke Trials Network Regional Coordinating Stroke Center U10 NS08652501 (PI: David Tirschwell). Dr. Holloway consulted for Milliman Guidelines (Reviewer of neurology guidelines) and Neurology Today (Associate Editor). His institution received grant support form the NIH.

Footnotes

Disclosures: Dr. Curtis has no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Koton S, Schneider AL, Rosamond WD, Shahar E, Sang Y, Gottesman RF, et al. Stroke incidence and mortality trends in us communities, 1987 to 2011. JAMA. 2014;312:259–268. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.7692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2015 update: A report from the american heart association. Circulation. 2015;131:e29–322. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The national institute of neurological disorders and stroke rt-pa stroke study group Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1581–1587. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512143332401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hacke W, Donnan G, Fieschi C, Kaste M, von Kummer R, Broderick JP, et al. Association of outcome with early stroke treatment: Pooled analysis of atlantis, ecass, and ninds rt-pa stroke trials. Lancet. 2004;363:768–774. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15692-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berkhemer OA, Fransen PS, Beumer D, van den Berg LA, Lingsma HF, Yoo AJ, et al. A randomized trial of intraarterial treatment for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:11–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Demchuk AM, Goyal M, Menon BK, Eesa M, Ryckborst KJ, Kamal N, et al. Endovascular treatment for small core and anterior circulation proximal occlusion with emphasis on minimizing ct to recanalization times (escape) trial: Methodology. Int J Stroke. 2015;10:429–438. doi: 10.1111/ijs.12424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell BC, Mitchell PJ, Kleinig TJ, Dewey HM, Churilov L, Yassi N, et al. Endovascular therapy for ischemic stroke with perfusion-imaging selection. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1009–1018. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adeoye O, Hornung R, Khatri P, Kleindorfer D. Recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator use for ischemic stroke in the united states: A doubling of treatment rates over the course of 5 years. Stroke. 2011;42:1952–1955. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.612358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwamm LH, Ali SF, Reeves MJ, Smith EE, Saver JL, Messe S, et al. Temporal trends in patient characteristics and treatment with intravenous thrombolysis among acute ischemic stroke patients at get with the guidelines-stroke hospitals. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6:543–549. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.000303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morgenstern LB, Bartholomew LK, Grotta JC, Staub L, King M, Chan W. Sustained benefit of a community and professional intervention to increase acute stroke therapy. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:2198–2202. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.18.2198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ebinger M, Winter B, Wendt M, Weber JE, Waldschmidt C, Rozanski M, et al. Effect of the use of ambulance-based thrombolysis on time to thrombolysis in acute ischemic stroke: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311:1622–1631. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.2850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.About Palliative Care [April 22, 2015];Center to Advance Palliative Care. website: https://www.capc.org/about/palliative-care.

- 13.Palliative Care and End-of Life Care [June 12 2015];National Quality Forum website. http://www.qualityforum.org/projects/palliative_care_and_end-of-life_care.aspx.

- 14.National Palliative Care Registry Annual Survey Summary [April 22, 2015];Palliative Care Growth in U.S. Hospitals. https://registry.capc.org/cms/portals/1/Reports/Registry_Summary%20Re port_2014.pdf.

- 15.Lanken PN, Terry PB, Delisser HM, Fahy BF, Hansen-Flaschen J, Heffner JE, et al. An official american thoracic society clinical policy statement: Palliative care for patients with respiratory diseases and critical illnesses. Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 2008;177:912–927. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200605-587ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holloway RG, Arnold RM, Creutzfeldt CJ, Lewis EF, Lutz BJ, McCann RM, et al. Palliative and end-of-life care in stroke: A statement for healthcare professionals from the american heart association/american stroke association. Stroke. 2014;45:1887–1916. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, Gallagher ER, Admane S, Jackson VA, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:733–742. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morrison RS, Dietrich J, Ladwig S, Quill T, Sacco J, Tangeman J, et al. Palliative care consultation teams cut hospital costs for medicaid beneficiaries. Health aff. 2011;30:454–463. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burton CR, Payne S, Addington-Hall J, Jones A. The palliative care needs of acute stroke patients: A prospective study of hospital admissions. Age Ageing. 2010;39:554–559. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afq077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mead GE, Cowey E, Murray SA. Life after stroke - is palliative care relevant? A better understanding of illness trajectories after stroke may help clinicians identify patients for a palliative approach to care. Int J Stroke. 2013;8:447–448. doi: 10.1111/ijs.12061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stevens T, Payne SA, Burton C, Addington-Hall J, Jones A. Palliative care in stroke: A critical review of the literature. Palliat Med. 2007;21:323–331. doi: 10.1177/0269216307079160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wee B, Adams A, Eva G. Palliative and end-of-life care for people with stroke. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2010;4:229–232. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0b013e32833ff4f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burton CR, Payne S. Integrating palliative care within acute stroke services: Developing a programme theory of patient and family needs, preferences and staff perspectives. BMC Palliat Care. 2012;11:22. doi: 10.1186/1472-684X-11-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holloway RG, Ladwig S, Robb J, Kelly A, Nielsen E, Quill TE. Palliative care consultations in hospitalized stroke patients. J Palliat Med. 2010;13:407–412. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chahine LM, Malik B, Davis M. Palliative care needs of patients with neurologic or neurosurgical conditions. Eur J Neurol. 2008;15:1265–1272. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2008.02319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eastman P, McCarthy G, Brand CA, Weir L, Gorelik A, Le B. Who, why and when: Stroke care unit patients seen by a palliative care service within a large metropolitan teaching hospital. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2013;3:77–83. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2012-000331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Addington-Hall J, Lay M, Altmann D, McCarthy M. Symptom control, communication with health professionals, and hospital care of stroke patients in the last year of life as reported by surviving family, friends, and officials. Stroke. 1995;26:2242–2248. doi: 10.1161/01.str.26.12.2242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quill TE, Abernethy AP. Generalist plus specialist palliative care--creating a more sustainable model. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1173–1175. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1215620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Becker KJ, Baxter AB, Cohen WA, Bybee HM, Tirschwell DL, Newell DW, et al. Withdrawal of support in intracerebral hemorrhage may lead to self-fulfilling prophecies. Neurology. 2001;56:766–772. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.6.766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Creutzfeldt CJ, Engelberg RA, Healey L, Cheever CS, Becker KJ, Holloway RG, et al. Palliative Care Needs in the Neuro-ICU. [published online ahead of print April 11, 2015]. [June 8, 2015];Crit Care Med. 2015 doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001018. http://journals.lww.com/ccmjournal. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Wilterdink JL, Bendixen B, Adams HP, Jr., Woolson RF, Clarke WR, Hansen MD. Effect of prior aspirin use on stroke severity in the trial of org 10172 in acute stroke treatment (toast). Stroke. 2001;32:2836–2840. doi: 10.1161/hs1201.099384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mayer SA, Copeland D, Bernardini GL, Boden-Albala B, Lennihan L, Kossoff S, et al. Cost and outcome of mechanical ventilation for life-threatening stroke. Stroke. 2000;31:2346–2353. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.10.2346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.George BP, Kelly AG, Schneider EB, Holloway RG. Current practices in feeding tube placement for us acute ischemic stroke inpatients. Neurology. 2014;83:874–882. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Creutzfeldt CJ, Holloway RG, Walker M. Symptomatic and palliative care for stroke survivors. J Gen Int Med. 2012;27:853–860. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1966-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Diringer MN, Edwards DF, Aiyagari V, Hollingsworth H. Factors associated with withdrawal of mechanical ventilation in a neurology/neurosurgery intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:1792–1797. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200109000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Verkade MA, Epker JL, Nieuwenhoff MD, Bakker J, Kompanje EJ. Withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment in a mixed intensive care unit: Most common in patients with catastropic brain injury. Neurocrit Care. 2012;16:130–135. doi: 10.1007/s12028-011-9567-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lautrette A, Darmon M, Megarbane B, Joly LM, Chevret S, Adrie C, et al. A communication strategy and brochure for relatives of patients dying in the icu. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:469–478. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hemphill JC, 3rd, Newman J, Zhao S, Johnston SC. Hospital usage of early donot-resuscitate orders and outcome after intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2004;35:1130–1134. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000125858.71051.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heyland DK, Frank C, Groll D, Pichora D, Dodek P, Rocker G, et al. Understanding cardiopulmonary resuscitation decision making: Perspectives of seriously ill hospitalized patients and family members. Chest. 2006;130:419–428. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.2.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Curtis JR, Vincent JL. Ethics and end-of-life care for adults in the intensive care unit. Lancet. 2010;376:1347–1353. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60143-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Charon R. The patient-physician relationship. Narrative medicine: A model for empathy, reflection, profession, and trust. JAMA. 2001;286:1897–1902. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.15.1897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.LeClaire MM, Oakes JM, Weinert CR. Communication of prognostic information for critically ill patients. Chest. 2005;128:1728–1735. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.3.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Anderson WG, Cimino JW, Ernecoff NC, Ungar A, Shotsberger KJ, Pollice LA, et al. A multicenter study of key stakeholders' perspectives on communicating with surrogates about prognosis in intensive care units. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12:142–152. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201407-325OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Creutzfeldt CJ, Holloway RG. Treatment decisions after severe stroke: Uncertainty and biases. Stroke. 2012;43:3405–3408. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.673376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boyd EA, Lo B, Evans LR, Malvar G, Apatira L, Luce JM, et al. “It's not just what the doctor tells me:” Factors that influence surrogate decision-makers' perceptions of prognosis. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:1270–1275. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181d8a217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Back AL, Arnold RM, Quill TE. Hope for the best, and prepare for the worst. Ann Int Med. 2003;138:439–443. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-5-200303040-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Back AL, Arnold RM, Baile WF, Tulsky JA, Fryer-Edwards K. Approaching difficult communication tasks in oncology. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:164–177. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.3.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Epstein RM, Street RL., Jr. Shared mind: Communication, decision making, and autonomy in serious illness. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9:454–461. doi: 10.1370/afm.1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]