Abstract

Objectives

The purpose of this study was to investigate the clinical features, radiologic findings, and treatment outcomes in patients of facial nerve paralysis with chronic ear infections. And we also aimed to evaluate for radiologic sensitivities on facial canal, labyrinth and cranial fossa dehiscences in middle ear cholesteatomas.

Methods

A total of 13 patients were enrolled in this study. Medical records were retrospectively reviewed for clinical features, radiologic findings, surgical findings, and recovery course. In addition, retrospective review of temporal bone computed tomography (CT) and operative records in 254 middle ear cholesteatoma patients were also performed.

Results

Of the 13 patients, eight had cholesteatomas in the middle ear, while two patients exhibited external auditory canal cholesteatomas. Chronic suppurative otitis media, petrous apex cholesteatoma and tuberculous otitis media were also observed in some patients. The prevalence of facial paralysis in middle ear cholesteatoma patients was 3.5%. The most common involved site of the facial nerve was the tympanic segment. Labyrinthine fistulas and destruction of cranial bases were more frequently observed in facial paralysis patients than nonfacial paralysis patients. The radiologic sensitivity for facial canal dehiscence was 91%. The surgical outcomes for facial paralysis were relatively satisfactory in all patients except in two patients who had petrous apex cholesteatoma and requiring conservative management.

Conclusion

Facial paralyses associated with chronic ear infections were observed in more advanced lesions and the surgical outcomes for facial paralysis were relatively satisfactory. Facial canal dehiscences can be anticipated preoperatively with high resolution CTs.

Keywords: Facial Paralysis, Ear, Infection, Cholesteatoma

INTRODUCTION

Complications from chronic ear infections are decreasing because of earlier diagnosis and initiation of appropriate treatments. However, chronic ear infections can still cause many intracranial and extracranial complications [1,2,3,4,5]. Among these complications, facial nerve paralysis is a potentially serious complication because it can result in facial asymmetry. In the literature, the incidences of facial paralysis were reported to range from 1%-3% in patients with chronic otitis media [6,7,8]. Facial nerve paralysis was frequently observed in cholesteatoma patients and in patients with chronic suppurative otitis media without cholesteatoma [6,8,9,10,11]. In this study, we aimed to investigate the clinical features, radiologic findings, and treatment outcomes in patients of facial nerve paralysis with chronic ear infections. And we also aimed to evaluate for radiologic sensitivities on facial canal, labyrinth and cranial fossa dehiscences in middle ear cholesteatomas. Our study includes a retrospective review of 13 patients with facial paralysis secondary to chronic ear infections. In addition, temporal bone computed tomographys (CTs) and operative reports of 254 cholesteatoma patients were reviewed to investigate for radiologic evidence of any fallopian canal, bony labyrinth and/or cranial base dehiscences.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

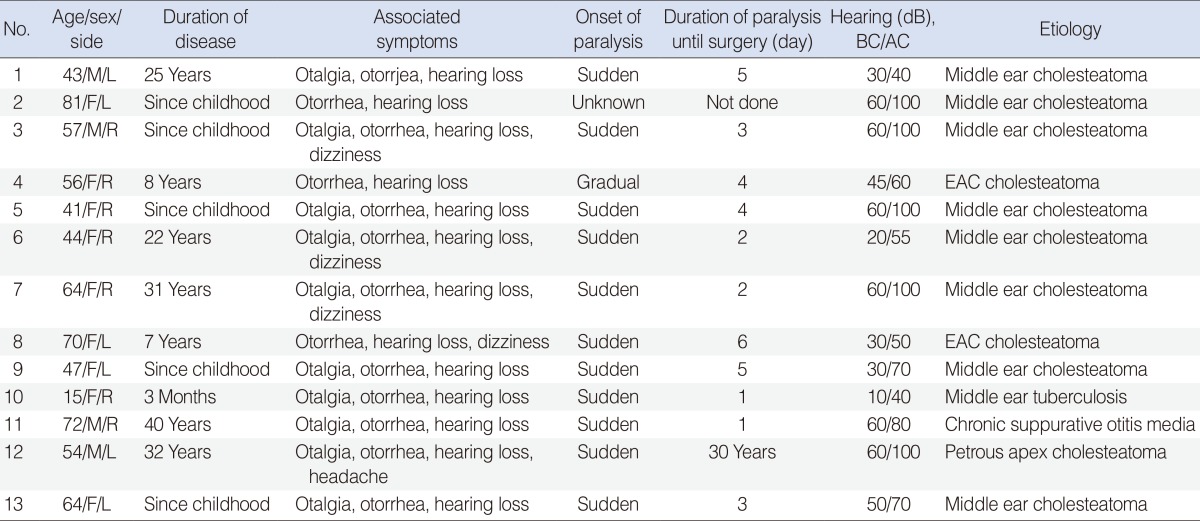

Between May 2004 and June 2009, there were 1,123 patients with chronic ear infections, of which 13 cases involving facial paralysis were investigated. The details described in our database included age at presentation, gender, affected side, associated symptoms, air-conduction and bone-conduction pure tone audiometry, and assessment of facial nerve function using the House-Brackmann grading system (Table 1).

Table 1. Clinical findings in 13 cases of chronic ear infections complicated by facial paralysis.

R, right; L, left; BC, bone conduction; AC, air conduction; EAC, external auditory canal.

Temporal bone CTs of these patients were also reviewed. Bony defects in the facial canal, and combined bony defects in the cranial base and bony labyrinth were analyzed. The preoperative and postoperative medications included antibiotics and corticosteroids in all but one patient who had complete facial paralysis managed conservatively. The type of surgery, operative findings, pathology, and the postoperative facial nerve functions were reviewed. A final assessment of facial nerve function was performed one year postoperatively.

All temporal bone CTs and operation records for 254 middle ear cholesteatoma patients were reviewed to evaluate for radiologic sensitivities on facial canal, labyrinth and cranial fossa dehiscences in middle ear cholesteatomas. Using the temporal bone CT, we evaluated for facial canal dehiscence, the presences of combined labyrinthine fistula and cranial base defects. The size of facial canal dehiscence was based on operative reports.

The differences in prevalence of bony labyrinth and cranial base defects between facial paralysis patients and nonfacial paralysis patients were examined using the Fisher exact test. Differences in facial canal dehiscence size between facial paralysis patients and nonfacial paralysis patients were compared using the Mann-Whitney U-test. P-values less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. GraphPad InStat 3 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA) and SPSS ver. 13 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) were used for the statistical analysis. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Chungnam National University Hospital.

RESULTS

Of the 13 patients, eight had cholesteatomas in the middle ear, while two patients exhibited external auditory canal cholesteatomas. Chronic suppurative otitis media, petrous apex cholesteatoma and tuberculous otitis media were also observed in one patient respectively. There were four males and nine females with a mean age of 54.4±17 years (range, 15 to 81 years). Affected ears included the right in seven cases and left in six cases. The duration of facial paralysis until surgery varied from 1 to 6 days except in two cases with complete paralysis. Many of the patients had a long history of ear disease. The onsets of facial nerve paralysis were sudden in 11 patients and gradual in one patient. Onset of paralysis was unknown in one patient who presented with complete paralysis. All patients presented with otorrhea and hearing loss, with five presenting with total deafness. Other frequently associated symptoms included otalgia in 10 patients and dizziness in four patients. The patient with petrous apex cholesteatoma also displayed signs of meningitis, but there were no other combined intracranial complications in other patients. The initial grades of facial paralysis according to the House-Brackmann grading system were II in one patient, III in nine patients, IV in one patient, and VI in two patients (Table 1).

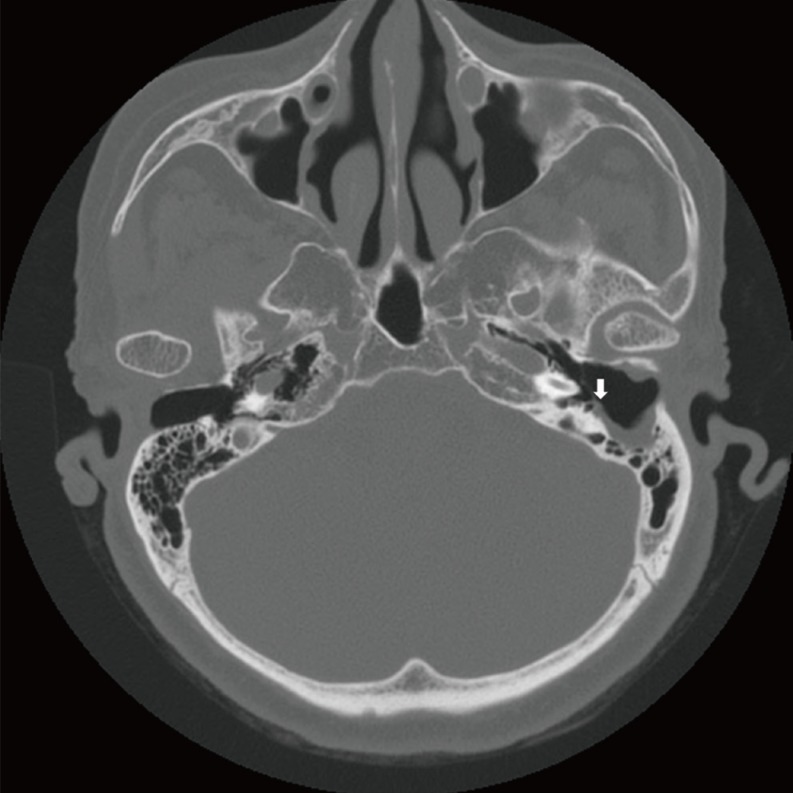

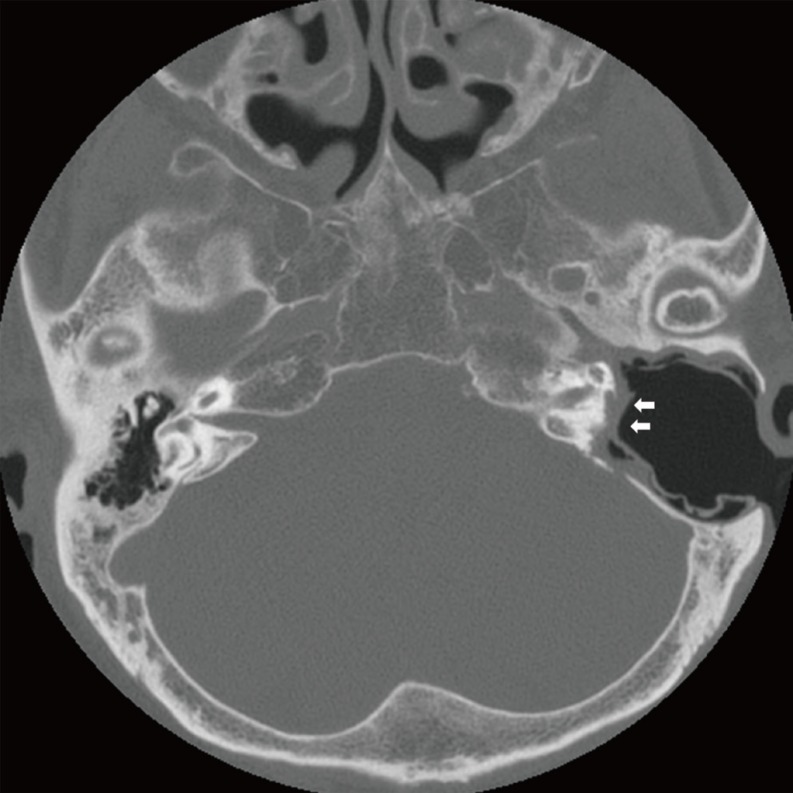

On high resolution temporal bone CT, 11 of them showed bony wall defects in the tympanic segment of the facial nerve, while two patients with external auditory canal cholesteatomas revealed bony dehiscences in the mastoid segment of the facial nerve (Fig. 1). There were two patients that showed canal defects in both tympanic and mastoid segments. Two patients with complete facial paralysis showed that wide segments of the facial nerve were involved. Combined bony defects in the tegmen tympani were observed in eight patients, and three of them also revealed the defects in the posterior cranial fossa. Destruction of bony labyrinths was observed in six patients in the lateral semicircular canal, and there was one patient who had destruction of all semicircular canals and vestibules (Fig. 2). Four patients with bony labyrinth destruction showed total deafness during audiogram testing.

Fig. 1. Preoperative temporal bone computed tomography of patient No. 8 showing a fallopian canal defect in the mastoid segment of the facial nerve (arrow).

Fig. 2. Computed tomography of patient No. 2 showing all semicircular canals and vestibular destructions. Note the absence of the facial nerve in the tympanic and mastoid segment with a combined posterior cranial base defect (arrows).

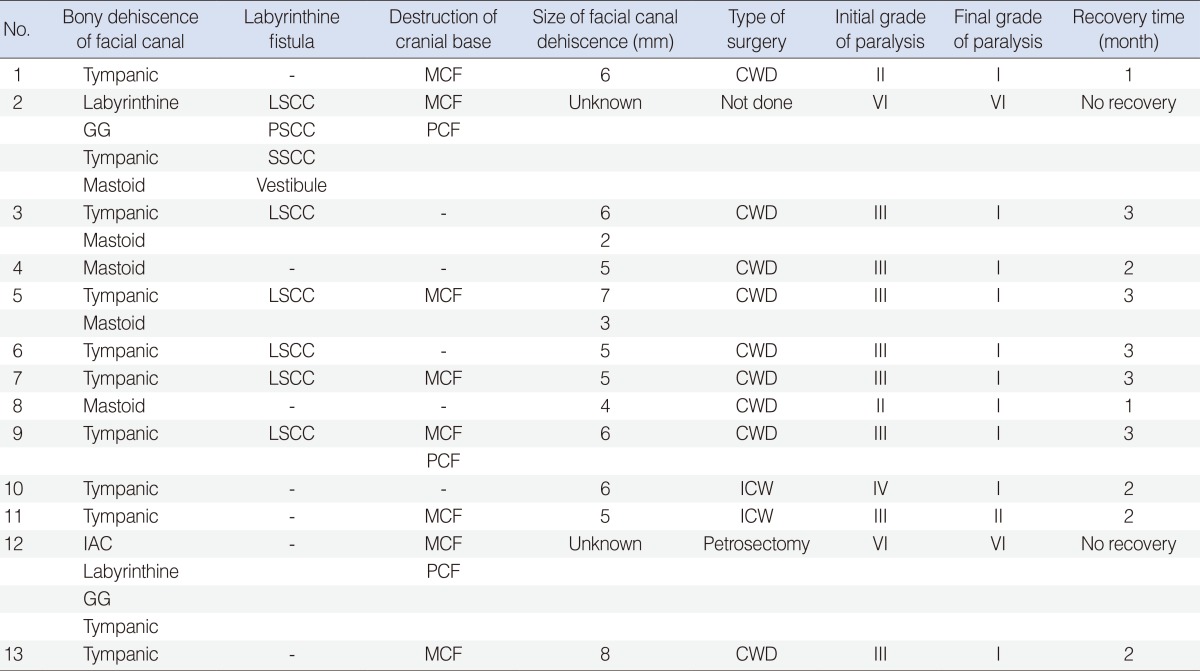

Surgical interventions were performed as early as possible using the transmastoid approach in 12 patients except in one patient who had complete facial paralysis requiring conservative management. Among 12 patients, nine patients underwent canal wall down mastoidectomy, two patients underwent intact canal wall mastoidectomy, and one patient with a petrous apex cholesteatoma underwent a subtotal petrosectomy. Total removal of the cholesteatoma lesions or granulation tissues around the facial nerve was performed. The one patient with a petrous apex cholesteatoma underwent a subtotal petrosectomy without facial nerve repair. Only limited bony wall decompression was performed around the dehiscent area and incision of the epineural sheath was not performed in all surgical cases. Exposed facial nerves were covered by temporal muscle fascia. Facial nerve paralysis was improved to House-Brackmann grade I in 10 patients within 3 months, while there was one patient who failed to show improvement beyond grade II one year after surgery (Table 2).

Table 2. Surgical findings and outcomes in 13 cases of chronic ear infections complicated by facial paralysis.

MCF, middle cranial fossa; CWD, canal wall down; GG, geniculate ganglion; LSCC, lateral semiciucular canal; PSCC, posterior semicircular canal; SSCC, superior semicircular canal; PCF, posterior cranial fossa; ICW, intact canal wall; IAC, internal auditory canal.

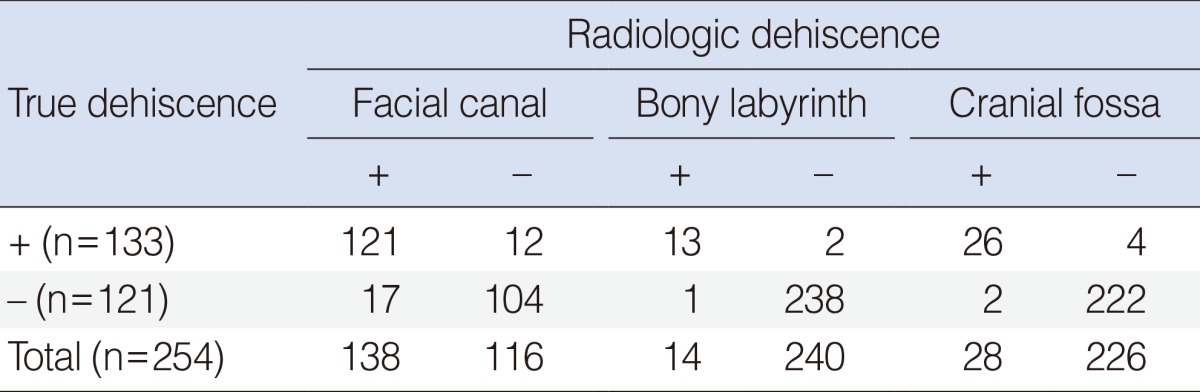

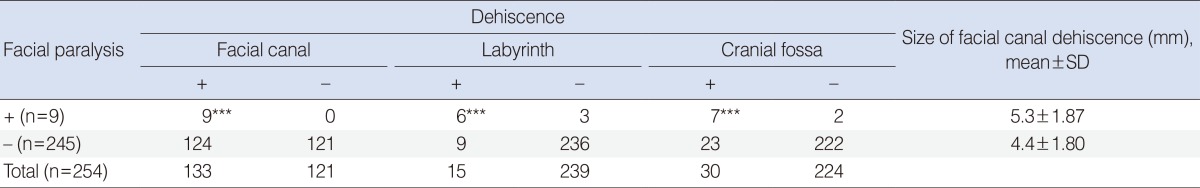

Among 254 patients with middle ear cholesteatomas, 54% of patients (138/254) revealed facial canal dehiscences based on high resolution temporal bone CTs. However, the true incidence of facial canal dehiscence was 52% in middle ear cholesteatoma patients (133/254). Only 3.5% of middle ear cholesteatoma patients (9/254) showed facial paralysis and it was 6.8% in patients with facial canal dehiscence (9/133). The radiological sensitivities were 91% in facial canal dehiscence (121/133), 87% in labyrinth (13/15), and 87% in cranial base defects (26/30) (Table 3). The median sizes of facial canal dehiscences were 5.3±1.87 mm in facial paralysis patients and 4.4±1.8 mm in nonfacial paralysis patients. There was no difference in the size of facial canal dehiscence between facial paralysis and nonfacial paralysis patients. The prevalence of labyrinthine fistula was significantly increased in facial paralysis patients (6/9) than in nonfacial paralysis patients as (9/245) (P<0.001). Cranial base defects were also significantly frequent in facial paralysis patients (7/9) than in nonfacial paralysis patients (23/245) (P<0.001) (Table 4).

Table 3. Comparisons of dehiscences in facial canal, bony labyrinth and cranial fossa between radiology and operation record in 254 middle ear cholesteatomas.

Table 4. Comparisons of dehiscences in facial canal, labyrinth, and cranial base between facial paralysis group and non-facial paralysis group in 254 middle ear cholesteatomas.

***P<0.001.

DISCUSSION

In the temporal bone, the facial nerve is an important structure that controls facial expression, lacrimation and taste sensation. It is generally surrounded by bony structures but can be exposed during the ossification process developmentally, during trauma, during otologic surgery and in inflammatory diseases such as otitis media and cholesteatoma. In the medical literature, the incidence of facial canal dehiscence was reported to be between 20%-74% in temporal bone studies [12,13,14]. The most common location of dehiscence is known to be the tympanic segment of the fallopian canal because it is located in the floor of middle ear and has very thin bony coverage. The tympanic part of the fallopian canal developed anteroposteriorly from the geniculate fossa to enclose the facial nerve embryologically. Incomplete closure of facial sulcus could lead to congenital bony defects of the tympanic segment [15].

However, the prevalence of facial paralysis in chronic ear disease was not very high. Most involved middle ear cholesteatomas and chronic otitis media patients. According to Quaranta and colleagues, only 1.2% of more than 1,400 cholesteatomas showed facial paralysis and others reported less than approximately 3% of chronic otitis media with or without cholesteatoma [6,7,8,16,17,18]. In our series, 3.5% of cholesteatoma patients revealed facial paralysis and it was observed in around 1% of chronic infectious ear disease that underwent ear surgery. Interestingly there were two patients with external auditory cholesteatoma causing facial paralysis. Chronic suppurative otitis media and tuberculous otitis media were also observed. Although 52% of middle ear cholesteatoma patients exhibited facial canal dehiscences, only 6.8% of patients revealed facial paralysis. This result indicates that the facial nerve has a relatively high resistance to infection.

Although there were no significant size differences in facial canal dehiscence between facial paralysis patients and nonparalysis patients, combined bony labyrinth destructions and cranial base defects were more frequently observed in facial paralysis patients. According to Ikeda et al. [16], 56% of facial paralysis patients with cholesteatoma had bony labyrinth destruction and 63% of those patients had cranial base destruction [16]. Those result coincided well with our results. In our series, 67% of facial paralysis patients with middle ear cholesteatoma showed bony labyrinth destruction and 78% of those patients also had cranial base destruction. As a result, it appears that facial nerve paralysis occurs in more advanced diseases.

The precise etiology of facial paralysis in chronic ear infection is not well known, but the direct inflammatory involvement of the facial nerve through fallopian canal dehiscence and compression resulting from edema is believed to be the involved pathophysiology. Some believe that the cholesteatoma itself could cause facial paralysis through neurotoxic substances that it might secrete and or cause bony destruction via various enzymatic activities [9,19]. There was also a histopathological study showing degenerative and inflammatory changes of the facial nerve in patients with facial paralysis due to chronic suppurative otitis media [20]

Sometimes it may be difficult to visualize the facial canal dehiscence by temporal bone CT because the bone surrounding the tympanic segment can be very thin and soft tissue lesions such as a cholesteatoma or granulation tissues may be adjacent to the facial canal. However, diagnoses preoperatively can be more easily attained with high resolution CT, with its radiological sensitivity for facial canal dehiscence reported to be approximately 66% [21]. In our series, the radiologic sensitivity of facial canal dehiscence was approximately 91% with a specificity of 86%. These results reveal that preoperative high resolution CT is a useful diagnostic tool for facial canal dehiscence.

Early surgical intervention can lead to more favorable improvements in facial function. There was a report that patients who had underwent surgery more than 2 months after the onset of paralysis displayed poorer outcome [16]. In our series, we performed surgery as soon as possible, with preoperative duration of paralysis not exceeding 6 days except in the patient with the petrous apex lesion. Although we could not compare the treatment result between an early and late intervention group, we believe that our good results were in part due to early intervention.

There have been many disagreements regarding the extent of facial nerve decompression required for treatment. Some authors postulated that a neural sheath incision should be performed for cases of complete paralysis, while there was reporting bony decompression from the geniculate ganglion to the stylomastoid foramen [8,22]. We did not perform any wide decompressions, with only limited bony decompressions around the dehiscences completed. None of the procedures had a neural sheath incision performed. All cholesteatomas and granulation tissues could be dissected relatively easily from the facial nerve under magnified view of the microscope. We thought that those infectious conditions should be regarded as different with other facial paralysis condition such as temporal bone fracture and idiopathic facial paralysis. We felt that the neural sheath might not only be a powerful barrier itself from infection, but that incision of the neural sheath could induce further nerve injury and possibly make the site more vulnerable for infection.

Prognosis for facial paralysis was relatively good in our series. There were two patients exhibiting normal facial function within one month and all the others except the patient with the petrous apex lesion had improvement within 2 or 3 months postoperatively. However, there was one patient that had no improvement beyond House-Brackmann grade II 1-year following surgery. This patient was more elderly with other major comorbidities such as diabetes possibly affecting his recovery course.

In conclusion, we analyzed 13 patients with chronic ear infections and facial paralysis. The most common pathology involved a cholesteatoma affecting the middle ear, external auditory canal, and petrous apex. Tuberculous otitis media and noncholesteatomatous suppurative otitis media could also be the cause for facial paralysis. The prevalence of facial paralysis was about 1% in chronic ear infections and 3.5% in middle ear cholesteatomas. The tympanic segment was the most frequently affected location and patients with facial paralysis had more frequent destructions involving the bony labyrinth and cranial base. Facial canal dehiscences were observed in 52% of middle ear cholesteatoma patients. The radiologic sensitivity of facial canal dehiscence was 91% and careful preoperative examination will be helpful to anticipate the facial nerve exposure during surgery and the surgical outcomes for facial paralysis were relatively satisfactory.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Agrawal S, Husein M, MacRae D. Complications of otitis media: an evolving state. J Otolaryngol. 2005 Jun;34(Suppl 1):S33–S39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Juselius H, Kaltiokallio K. Complications of acute and chronic otitis media in the antibiotic era. Acta Otolaryngol. 1972 Dec;74(6):445–450. doi: 10.3109/00016487209128475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kangsanarak J, Fooanant S, Ruckphaopunt K, Navacharoen N, Teotrakul S. Extracranial and intracranial complications of suppurative otitis media. Report of 102 cases. J Laryngol Otol. 1993 Nov;107(11):999–1004. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100125095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pfaltz CR. Complications of otitis media. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 1982;44(6):301–309. doi: 10.1159/000275609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yorgancılar E, Yildirim M, Gun R, Bakir S, Tekin R, Gocmez C, et al. Complications of chronic suppurative otitis media: a retrospective review. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2013 Jan;270(1):69–76. doi: 10.1007/s00405-012-1924-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Savic DL, Djeric DR. Facial paralysis in chronic suppurative otitis media. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1989 Dec;14(6):515–517. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2273.1989.tb00415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takahashi H, Nakamura H, Yui M, Mori H. Analysis of fifty cases of facial palsy due to otitis media. Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1985;241(2):163–168. doi: 10.1007/BF00454350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yetiser S, Tosun F, Kazkayasi M. Facial nerve paralysis due to chronic otitis media. Otol Neurotol. 2002 Jul;23(4):580–588. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200207000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Antoli-Candela F, Jr, Stewart TJ. The pathophysiology of otologic facial paralysis. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1974 Jun;7(2):309–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harker LA, Pignatari SS. Facial nerve paralysis secondary to chronic otitis media without cholesteatoma. Am J Otol. 1992 Jul;13(4):372–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Redaelli de Zinis LO, Gamba P, Balzanelli C. Acute otitis media and facial nerve paralysis in adults. Otol Neurotol. 2003 Jan;24(1):113–117. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200301000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Di Martino E, Sellhaus B, Haensel J, Schlegel JG, Westhofen M, Prescher A. Fallopian canal dehiscences: a survey of clinical and anatomical findings. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2005 Feb;262(2):120–126. doi: 10.1007/s00405-004-0867-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takahashi H, Sando I. Facial canal dehiscence: histologic study and computer reconstruction. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1992 Nov;101(11):925–930. doi: 10.1177/000348949210101108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yetiser S. The dehiscent facial nerve canal. Int J Otolaryngol. 2012;2012:679708. doi: 10.1155/2012/679708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barnes G, Liang JN, Michaels L, Wright A, Hall S, Gleeson M. Development of the fallopian canal in humans: a morphologic and radiologic study. Otol Neurotol. 2001 Nov;22(6):931–937. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200111000-00038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ikeda M, Nakazato H, Onoda K, Hirai R, Kida A. Facial nerve paralysis caused by middle ear cholesteatoma and effects of surgical intervention. Acta Otolaryngol. 2006 Jan;126(1):95–100. doi: 10.1080/00016480500265950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ozbek C, Somuk T, Ciftci O, Ozdem C. Management of facial nerve paralysis in noncholesteatomatous chronic otitis media. B-ENT. 2009;5(2):73–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Quaranta N, Cassano M, Quaranta A. Facial paralysis associated with cholesteatoma: a review of 13 cases. Otol Neurotol. 2007 Apr;28(3):405–407. doi: 10.1097/01.mao.0000265189.29969.c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chu FW, Jackler RK. Anterior epitympanic cholesteatoma with facial paralysis: a characteristic growth pattern. Laryngoscope. 1988 Mar;98(3):274–279. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198803000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Djeric D, Savic D. Otogenic facial paralysis: a histopathological study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1990;247(3):143–146. doi: 10.1007/BF00175963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fuse T, Tada Y, Aoyagi M, Sugai Y. CT detection of facial canal dehiscence and semicircular canal fistula: comparison with surgical findings. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1996 Mar-Apr;20(2):221–224. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199603000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cawthorne T. Intratemporal facial palsy. Arch Otolaryngol. 1969 Dec;90(6):789–799. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1969.00770030791023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]