Abstract

Given the growing number of arthritis patients and the limitations of current treatments, there is great urgency to explore cartilage substitutes by tissue engineering. In this study, we developed a novel decellularization method for menisci to prepare acellular extracellular matrix (ECM) scaffolds with minimal adverse effects on the ECM. Among all the acid treatments, formic acid treatment removed most of the cellular contents and preserved the highest ECM contents in the decellularized porcine menisci. Compared with fresh porcine menisci, the content of DNA decreased to 4.10%±0.03%, and there was no significant damage to glycosaminoglycan (GAG) or collagen. Histological staining also confirmed the presence of ECM and the absence of cellularity. In addition, a highly hydrophilic scaffold with three-dimensional interconnected porous structure was fabricated from decellularized menisci tissue. Human chondrocytes showed enhanced cell proliferation and synthesis of chondrocyte ECM including type II collagen and GAG when cultured in this acellular scaffold. Moreover, the scaffold effectively supported chondrogenesis of human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Finally, in vivo implantation was conducted in rats to assess the biocompatibility of the scaffolds. No significant inflammatory response was observed. The acellular ECM scaffold provided a native environment for cells with diverse physiological functions to promote cell proliferation and new tissue formation. This study reported a novel way to prepare decellularized meniscus tissue and demonstrated the potential as scaffolds to support cartilage repair.

Introduction

Cartilage damage is the leading cause of disability in the United States today, and by the year 2030, the prevalence of arthritis is projected to be 25% of the population.1–4 Articular cartilage allows for the relative movement of opposing joint surfaces under heavy loads, and cartilage defects are accompanied by persistent pain and functional limitations of the joint, but damaged articular cartilage displays a limited capacity for self-regeneration.5,6 Current clinical practices for cartilage repair include microfracture, autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI), and cartilage transplantation.7 Microfracture is a relative simple procedure but usually leads to a repair with fibrocartilage, which is inferior to hyaline cartilage in the joints.8 ACI involves two steps of operation on patients and is a lengthy process. The outcomes of ACI and its improved procedure (matrix-induced autologous chondrocyte implantation) were not always satisfactory due to fibrocartilage formation and tissue hypertrophy.9,10 Cartilage transplantation is a widely used procedure, but its success is limited by the scarcity of allogeneic donor tissues and potential risk of pathogen transmission.11 Given the growing number of patients, the significant impairment to the quality of life, and the limitations of current treatments, there is an urgency to explore alternative treatment strategies for degenerative cartilage diseases; thus, this has been a major motivation in cartilage tissue engineering.12

“Tissue engineering” focuses on developing functional substitutes for damaged tissues by combining cells, scaffolds, and signals or stimuli.13 Cartilage consists of a unique extracellular matrix (ECM) that is produced and maintained by chondrocytes. The ECM includes collagen fibrils of predominantly type II collagen, proteoglycans such as aggrecan, glycosaminoglycan (GAG), and hyaluronic acid (HA). The ECM contributes to the mechanical properties of cartilage, has a feedback regulatory role in chondrocyte activities, and also characterizes the chondrocyte phenotype.14 Chondrocytes are an exclusive cell type in cartilage, but only (1.8–4.5)×105 chondrocytes can be acquired by an arthroscopic surgery from a minor load-bearing area on the single upper medial femoral condyle of the knee defect.15,16 These cells are insufficient for subsequent in vivo transplantation; accordingly, the in vitro expansion of cells is essential. However, isolated chondrocytes easily lose their phenotype in two-dimensional monolayer culture, and this is accompanied by a shift toward a fibroblast-like morphology characterized by an increased expression of type I collagen. Fortunately, this process can be reversed when chondrocytes are relocated into a three-dimensional (3D) environment, and this observation confirms the importance of scaffolds in supporting the chondrocytic phenotype.17,18

For current scaffolds that have been approved for use in cartilage repair,17 type I and III collagen membranes (such as Maix, Chondro-gide, and Permacol collagen Ossix) are clinically available for ACI; Hyalograft C is a tissue-engineered graft composed of autologous chondrocytes grown on the hyaluronan-based scaffold; Bio-Seed-C is a porous 3D scaffold made of polyglycolic acid (PGA), polylactic acid (PLA), and polydioxanone. Despite promising clinical results of these scaffolds, ECM scaffold derived from tissue could additionally provide biophysical and biochemical cues to modulate the neo-tissue formation by mimicking the functional and structural characteristics of the native environment, and regulating cellular functions through various existing bioactive molecules, such as the ECM, growth factors, and cytokines.19,20 For example, Beatty et al.21 seeded chondrocytes in polyglycolic acid-poly-l-lactic acid matrix (PGA-PLLA) scaffolds or ECM-derived scaffolds from porcine small intestinal submucosa (SIS), and implanted them into athymic mice. Higher GAG content and chondroid-like tissues appeared in the SIS group, demonstrating the biological activity of ECM scaffold.

To harvest the bioactivity of ECM, many native tissues are considered for regenerative medicine. The components of the ECM are generally conserved among species and tolerated well even by xenogeneic recipients; however, xenogeneic or allogeneic cellular antigens may induce severe inflammation or immune-mediated rejection. To minimize the immunogenicity and preserve the ECM, many decellularization methods are developed.19,22,23 Decellularization methods can be classified into physical, enzymatic, and chemical treatments and vary widely depending on the types of tissue and species of origin.19 A number of acellular ECM scaffolds and related decellularization protocols have received regulatory approval for use in humans, for example, human dermis (Alloderm®, LifeCell), porcine SIS (SurgiSIS®, Cook Biotech; Restore®, DePuy Orthopaedics), porcine urinary bladder (MatriStem®, ACell), and porcine heart valves (Synergraft®, CryoLife).24 While decellularization is quite successful with soft connective tissues, the success in decellularization of compact tissues such as cartilage and meniscus are limited. Elder et al.25 evaluated the effects of different decellularization treatments (sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], tributyl phosphate, Triton X-100, and a hypotonic followed by a hypertonic solution) on articular cartilage, and found that treatment with 2% SDS for 1 or 2 h significantly reduced the DNA content, while maintaining the biochemical and biomechanical properties. Furthermore, SDS treatment for 6 or 8 h resulted in the complete elimination of cell nuclei, but the GAG content and compressive properties significantly decreased.

The knee joint contains cartilage and menisci. The menisci are a pair of fibrocartilages comprised of cells and ECM. The ECM is generated and maintained by a heterogeneous cell population (chondrocytes, fibroblasts, or intermediate cells exhibiting characteristics of both). In general, collagens make up the majority of the ECM (75%), followed by GAG (17%), glycoproteins (<1%), and elastin (<1%). Both the cartilage and meniscus have almost similar compositions and functions,26 and the abundance of menisci made them a cost-effective alternative for cartilage, so a decellularized meniscus may be used as an alternative scaffold for cartilage regeneration. Besides, it has been reported that decellularized meniscus tissue seeded with mesenchymal stem cells showed chondroprotective effect in rat model.27 Therefore, the development of effective decellularization methods for porcine menisci holds promise in engineering scaffolds for cartilage repair. However, decellularization of meniscus tissues remains challenging. Yamasaki et al. decellularized rat menisci with sodium ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA), ethanol for 3 days and freeze-thawed several times. An ovine meniscus acellular scaffold was fabricated with a multistep enzymatic process of trypsin/collagenase/protease by Maier et al.28 The lengthy and expensive processes removed the cells but resulted in loss of ECM.

Acid treatments have been used in decellularization protocols to solubilize the cytoplasmic component of cells and remove nucleic acids. Peracetic acid was reported to render the porcine SIS acellular, and maintain a complex mixture of structural proteins in the native 3D architecture.29,30 Similarly, the urinary bladder basement membrane and urinary bladder submucosa (UBS) of pigs were decellularized and disinfected by immersion in peracetic acid, ethanol, and then deionized water.31 In this study, we developed a simple and effective acid-based decellularization method for porcine menisci. The formic acid treatment removed most of cellular materials while minimizing the adverse effect on GAG and type II collagen. To demonstrate the functionality of this acellular ECM scaffolds, the growth of human chondrocytes and the differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) were evaluated in vitro. Human chondrocytes showed enhanced cell proliferation and significant synthesis of ECM, and hMSCs underwent chondrogenic differentiation when cultured in the acellular scaffolds. Furthermore, the biocompatibility of the acellular ECM scaffolds was evaluated in vivo. Positive in vitro activity and a minimal inflammatory response in vivo established a possible clinical utility of this acellular ECM scaffold for cartilage regeneration.

Materials and Methods

Development of a decellularization method and fabrication of scaffolds

Whole menisci were harvested from adult porcine knee joints, which were bought from pork retailer, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Biowest), and then freeze-dried (Eyela FD-5N). Lyophilized menisci were finely shattered (Yunghsing), and 0.2 g of menisci was suspended in 10 mL of acetic acid (monoprotic acid, >99%; Sigma-Aldrich), formic acid (monoprotic acid, >99%), peracetic acid (monoprotic acid, 0.15% and 15%; Panreac Química S.L.U.), malic acid (diprotic acid, 60%; Merck), succinic acid (diprotic acid, 5%; Showa), and citric acid (triprotic acid, 60%; Riedel-de Haën) while stirring at room temperature. The period of acid immersion was 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, or 12 h. Minced menisci immersed in PBS for 12 h with the same processing steps were served as a control group. At predetermined time points, the suspensions were homogenized (Kinematica AG) and dialyzed (Cellu Sep). After the removal of any excess acid and cellular debris by dialysis, the meniscus slurry was placed into cylindrical molds, and freeze-dried to fabricate the scaffolds. These scaffolds were sterilized with ethylene oxide and then degassed for further evaluations. The success of decellularization was determined by a biochemical analysis to compare the amount of DNA and major ECM components (GAG and collagen).

Characterizations of acellular ECM scaffolds

Biochemical analysis

To measure the amounts of DNA, GAG, and total collagen, samples were first digested with a papain solution (0.56 U/mL in 150 mM sodium chloride, 55 mM sodium citrate, 5 mM cysteine hydrochloride, and 5 mM sodium EDTA) (all from Sigma-Aldrich) at 60°C for 16 h. The content of double-stranded DNA was measured with a PicoGreen Quantification Kit (Molecular Probes), and the previously reported value of 7.7 pg of DNA per chondrocyte was used to approximate the cell number.32 The fluorescence of the DNA-free blank was subtracted from that of the experimental groups to account for the fluorescence of the scaffold alone. The amount of GAG was determined with a Blyscan® GAG assay kit (Biocolor) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The absorbance against the background control was obtained at a wavelength of 656 nm with a microplate spectrophotometer (Bio-Tek). Chondroitin sulfate was used as a standard to calculate concentrations of GAG.

The papain digestion was further acid-hydrolyzed and reacted with a chloramine-T and p-dimethylaminobenzaldehyde solution to determine the quantity of hydroxyproline. The hydroxyproline content was converted to that of total collagen using a mass ratio of 7.25.33 The optical density was detected with a microplate reader at 560 nm (Bio-Tek). A standard curve was established using a series of concentrations of hydroxyproline.

Amounts of types I and II collagen were investigated by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using type I and II collagen detection kits (Chondrex) as described by the supplier. Briefly, samples were digested in a pepsin solution at 4°C with gentle mixing for 48 h and then a pancreatic elastase solution at 4°C overnight. The optical density values of the ELISA reaction were read at 490 nm in a microplate reader (Bio-Tek).

Histological and immunohistochemical staining

Menisci before and after decellularization were fixed in 10% (v/v) neutral buffered formalin (Sigma-Aldrich) overnight, dehydrated through an ethanol series, and embedded in paraffin. Specimen longitudinal sections of 5–10 μm in thickness were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) (Sigma-Aldrich) to visualize nuclei, or stained with Alcian blue (Sigma-Aldrich) for GAG deposition,34,35 or stained with Masson's trichrome (Sigma-Aldrich) to observe total collagen.36,37 Type II collagen was immunolocalized by an anti-type II collagen antibody (bs-0709r; Bioss) with a 1:100 dilution in Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20 solution, and the signal was amplified with an UltraVision Quanto Detection System (Thermo Scientific) for 10 min, followed by diaminobenzidine for visualization as described by the manufacturer. Nuclei were counterstained with hematoxylin. Slides were scanned with ScanScop (Aperio).

Scanning electron microscopy

The microstructure and pore size of the scaffold were observed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (Hitachi-2400). Specimens were first gold-coated using a sputter coater (Hitachi IB-2) before SEM observation. The average pore size of the scaffold was estimated from the SEM images.

Water absorption ability and porosity

Dried scaffolds and vials of PBS were weighed as W0 and W1, respectively. The scaffolds were placed in PBS vials in an incubator at 37°C overnight to allow free absorption. Scaffolds were then removed, and the vials of PBS were weighed as W2. The percentage water absorption was calculated according to the following equation38:

|

The porosity of the scaffolds was measured according to Archimedes' principle, and it was assumed that the scaffolds were unable to swell any further after overnight immersion in water so that the volume of the water absorbed was equal to the pore volume. The porosity was calculated according to the following formula:

|

where V is the volume of the scaffold and dwater is the density of water.

In vitro studies

In vitro cytotoxicity test

Sterilized scaffolds (6 mm in diameter and 2 mm in height) were incubated in serum-containing medium for 24 h at 37°C. The scaffold extract medium (150 μL) was taken out for a later in vitro cytotoxicity test. NIH 3T3 mouse fibroblast cells were seeded onto a 96-well plate at a seeding density of 104 cells/well and incubated at 37°C overnight. The medium was then replaced with either the scaffold extract or fresh medium, and incubated further. After incubation for 24 h, the medium was replaced with fresh medium containing Alamar blue reagent (Invitrogen Life Technologies) and again incubated for 2 h. The fluorescent intensity of the Alamar blue/medium mixture was measured with a microplate reader (TeCan) at an excitation wavelength of 560 nm and emission wavelength of 590 nm. The value of the fluorescence is proportional to the number of living cells and corresponds to the toxicity of the scaffold.

In vitro chondrocyte proliferation study

After a confluent cell layer had formed, human primary chondrocytes (ScienCell Research Laboratories; number of donor was one) were detached using 0.025% trypsin plus EDTA (Biowest) in PBS, resuspended in the supplemented growth medium containing basal medium, fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin/streptomycin solution, and chondrocyte growth supplement (ScienCell Research Laboratories), and used for the in vitro chondrocyte proliferation experiments. Before cell seeding, scaffolds (6 mm in diameter and 2 mm in height) were immersed in PBS and medium for 5 min each, and the excess liquid was removed with sterile tissue paper, and the scaffolds then put on 96-well plates. Chondrocyte suspensions with the passage number of 2–5 (10 μL; 105 cells) were dropped directly into the scaffolds using a pipette. The cells/scaffold constructs were placed in an incubator (at 37°C with 5% CO2) for 2 h for cell adhesion before 0.2 mL of fresh growth medium was added, and chondrocytes were cultured in the scaffold with the medium changed every 3 days. Scaffolds without cells were also similarly cultured and taken as a blank.

Live/dead cell staining

As to the live/dead cell staining, calcein AM is capable of permeating the membrane of viable cells, where it is cleaved by intracellular esterase and produces a green fluorescence. Ethidium bromide homodimer-1 is able to enter cells with damaged membranes and bind to fragmented nucleic acids, thereby producing red fluorescence in dead cells. On days 7, 14, 21, and 28, the cell/scaffold constructs were rinsed with sterile PBS, and incubated with a Live/dead Assay Kit (Molecular Probes) (8 μM calcein-AM and 4 μM ethidium homodimer-1). Sections were immediately examined with an inverted fluorescence microscope linked with a confocal imaging system (Leica TCS SP5; Leica Microsystem) using FITC/Texas red filter.

Total RNA extraction and real-time polymerase chain reaction

To quantify gene expressions of aggrecan, and types I, II, and X collagen, total cellular RNA was extracted from chondrocytes grown on scaffolds on days 7, 14, 21, and 28, respectively, according to the standard TRIzol (Invitrogen Life Technologies) protocol. The concentration and purity of the extracted RNA were evaluated with a NanoDrop ND-1000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo) with UV absorbance. Only samples that exhibited a 260/280-nm ratio of >1.8 were used in the following experiments. Isolated messenger (m)RNA was transcribed into complementary (c)DNA with a ReverTra Ace kit (Toyobo).

Gene expressions of aggrecan, and types I, II, and X collagen were quantified by a real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) on a LightCycler 480 system (Roche Applied Science). Primers were designed by the Roche Universal ProbeLibrary (UPL) Assay Design Center for the Human ProbeLibrary (www.roche-applied-science.com), and human ProbeLibrary probe nos. 9 (sequence: 5′-tggtgatg-3′) and 80 (sequence: 5′-cctggaga-3′) (Roche Applied Science) were used. UPLs are hydrolysis probes of 8- to 9-nucleotide locked nucleic acid that are labeled at the 5′ end with the fluorescent dye and at the 3′ end with a quencher dye. The combination of the hydrolysis probe and the corresponding primer pair offered the specificity required for each particular genomic locus of interest.39 Target genes were amplified using specific primers for aggrecan (NM_001135, forward: 5′-cagatggacaccccatgc-3′ and reverse: 5′-cattccactcg cccttctc-3′), type I collagen (NM_000088, forward: 5′-gccaa cctggtgctaaagg-3′ and reverse: 5′-caggagcaccaacattacca-3′), type II collagen (NM_001844, forward: 5′-gtgaacctggtgtctctggtc-3′ and reverse: 5′-tttccaggttttccagcttc-3′), and type X collagen (NM_000493, forward: 5′-agcttcagaaagctgccaag-3′ and reverse: 5′-gcagcatattctcagatggattct-3′). The housekeeping gene, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphatedehydrogenase (GAPDH), was used as a reference gene (NM_002046, forward: 5′-acgggaagcttgtcatcaat-3′ and reverse: 5′-catcgccccacttgatttt-3′). For each reaction, a LightCycler TaqMan Master kit (Roche Applied Science) was used with 400 nM of each primer, 0.2 μL of the probe, and 900 ng of cDNA in a total volume of 10 μL. All amplifications were carried out in a LightCycler 480 instrument (Roche Applied Science) under the following conditions: preheating for 1 cycle at 95°C for 15 min; amplification for 45 cycles of 95°C for 10 s, 58°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 3 s; and final cooling to 40°C. Based on the threshold cycle (CT) values for each target and reference gene, a comparative CT method was used to quantify the relative amounts of the target genes.40 The mRNA expression levels of aggrecan, types I, II, and X collagen was normalized to the value of GAPDH level of that sample at that time point. Because cells were seeded on day 0 and no gene expression was evaluated on that day, the mRNA expression on day 7 was set as 1, and the expression levels on days 14, 21, and 28 were relative to day 7. The target genes expression levels on days 14, 21, and 28 relative to day 7 were analyzed by comparative CT method using GAPDH as the internal control.41,42

Chondrogenesis of bone marrow-derived hMSCs

Bone marrow-derived hMSCs were provided by Texas A&M University Health Science Center (Donor No. 8001L). hMSCs were cultured in a monolayer with hMSC growth medium (Lonza) at 37°C with 5% CO2 and medium changes every 3 days. After a confluent cell layer had formed, hMSCs were detached using 0.05% trypsin plus EDTA (Lonza), resuspended in hMSC growth medium, and used for the following chondrogenic induction experiments. hMSC suspensions with the passage number of 3–5 (10 μL; 105 cells) were dropped directly into 96-well plates (tissue culture polystyrene [TCPS] group)43 or scaffolds (6 mm in diameter and 2 mm in height, [S] group) in 96-well plates using a pipette. The TCPS and cell/scaffold constructs were placed in an incubator for 2 h for cell adhesion, after which 0.2 mL of growth medium was added ([M] group). For chondrogenesis, hMSC chondrogenic SingleQuots™ medium (Lonza) containing insulin/transferring/selenium, dexamethasone, ascorbate, sodium pyruvate, proline, GA-1000, l-glutamine, and transforming growth factor-β3 was added ([C] group). All TCPS and cell/scaffolds were kept in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 14 or 21 days and medium changes every 3 days. Further biochemical analysis, histological and immunohistochemical staining, and real-time PCR analysis were performed on hMSCs. The target genes expression levels relative to hMSCs cultured in a monolayer and growth medium (TCPS-M) on day 14 were analyzed by comparative CT method using GAPDH as the internal control. The value of hMSCs being in TCPS-M on day 14 was set to 1, and the expression when hMSCs cultured in different conditions on day 14 or 21 were compared to that of TCPS-M or TCPS-C on day 14. As to the biochemical analysis, first of all, the amount of GAG and collagen was normalized to that of DNA of that sample at that time point. Then, the value of TCPS-M on day 14 was set as the calibrator as 1, and the values of other treatment groups were relative to TCPS-M or TCPS-C on day 14.

In vivo immunobiocompatibility study

This animal experiment was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey (Approved protocol No. 94-048), and was in compliance with the Animal Welfare Act. Fifteen male 8–10-week-old Sprague Dawley rats were used. After anesthetization with isoflurane (Abbott) and disinfection with betadine and 70% alcohol, a 1-cm incision was made on the dorsum of each rat, and four subcutaneous pockets were made by blunt dissection. Each scaffold (8 mm in diameter×2 mm thickness) was subcutaneously inserted into a pocket, while three rats were treated as a sham-operated group, and the wound was closed with wound closure clips. The animals were then returned to the housing facility, where they had free access to food and water. Weighing was performed once a week to check the health of the rats. On days 7, 14, and 28, rats were humanely sacrificed (n=5) by carbon dioxide inhalation euthanasia in Laboratory Animal Service Center, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, and implants were harvested, fixed in 10% (v/v) neutral buffered formalin (Sigma-Aldrich) overnight, and embedded in paraffin. Specimen longitudinal sections were stained with H&E to assess for the presence of residual scaffold and inflammatory infiltrate (lymphocytes, macrophage, and neutrophils).44,45

Statistical analysis

Results of each independent experiment were based on repetitive samples, and data are expressed as the mean±standard deviation (SD). For each experiment, there were three scaffolds (belong to the same batch of scaffolds) tested. Each batch contained 12 menisci from three animals, and all were shattered and mixed together. Three different batches of scaffolds were conducted in every assay, so triplicate data were represented. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS statistical software (PASW Statistics 18.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL). Porcine menisci before and after decellularization were compared by Student's t-test. A one-way analysis of variance was used to determine whether significant differences in the biochemical analysis and mRNA expressions of chondrocytes and hMSCs grown on scaffolds existed at different time points. First, the homogeneity of variance was tested, and a post hoc Tukey's test or Dunn's method was used for subsequent pairwise comparisons. Differences were considered significant at a p-value of <0.05.

Results

Development of a decellularization method

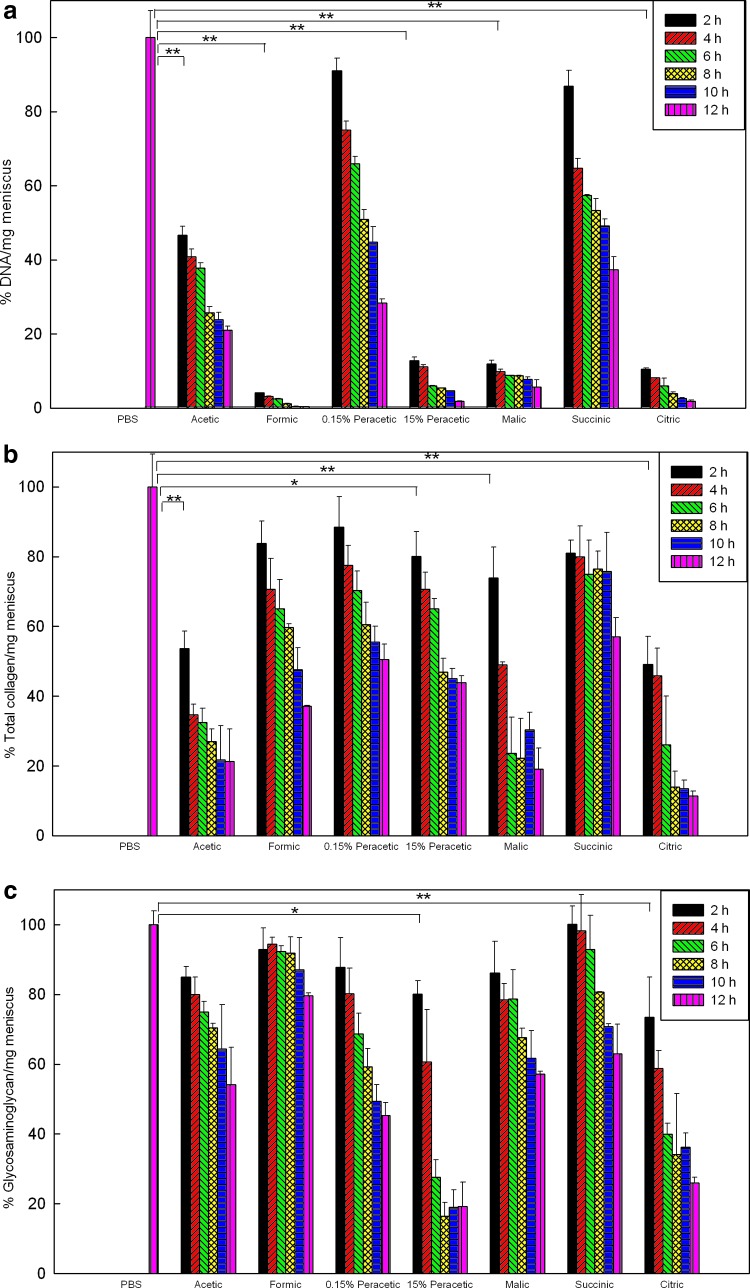

The amounts of DNA, GAG, and total collagen were first normalized to dry weight, and then compared to the fresh menisci treated with PBS under the same processing steps. Figure 1a shows the menisci immersed in formic acid solution for 2 h decreased the amount of DNA to 4.10%±0.03% (p<0.001) and to 0.40%±0.02% after 12 h. At 2 h, the DNA content decreased to 46.67%±2.40%, 12.85%±0.87%, 11.94%±0.93%, and 10.55%±0.27% when treated with acetic, 15% peracetic, 60% malic, and 60% citric acids, respectively; thus, these acids had significant decellularization effects (p<0.001). No obvious influences were found for menisci treated with 0.15% peracetic and 5% succinic acids for 2 h (p=0.059 and 0.074, respectively).

FIG. 1.

Contents of DNA (a), total collagen (b), and glycosaminoglycan (c) of porcine menisci following various decellularization treatments at different time points are compared to fresh menisci treated with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) under the same processing steps. Values are presented as the mean±standard deviation (SD) (n=3). Statistical analysis were conducted for treatment at 2 h; *p<0.05 and **p<0.001 compared to fresh menisci treated with PBS. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tec

Figure 1b and c showed the preservation of major ECM components (total collagen and GAG) after different treatments. Treatment with formic acid for 2 h had no significant adverse effect on either the GAG (p=0.087) or collagen content (p=0.714), while treatment with formic acid for 12 h reduced the collagen amount to 37.09%±0.29% (p=0.011). Acetic, 15% peracetic, malic, and citric acids treatment for 2 h caused extensive damage to the collagen; 15% peracetic and citric acids greatly decreased the amount of GAG.

Characterizations of acellular ECM scaffolds

Biochemical analysis and histological staining

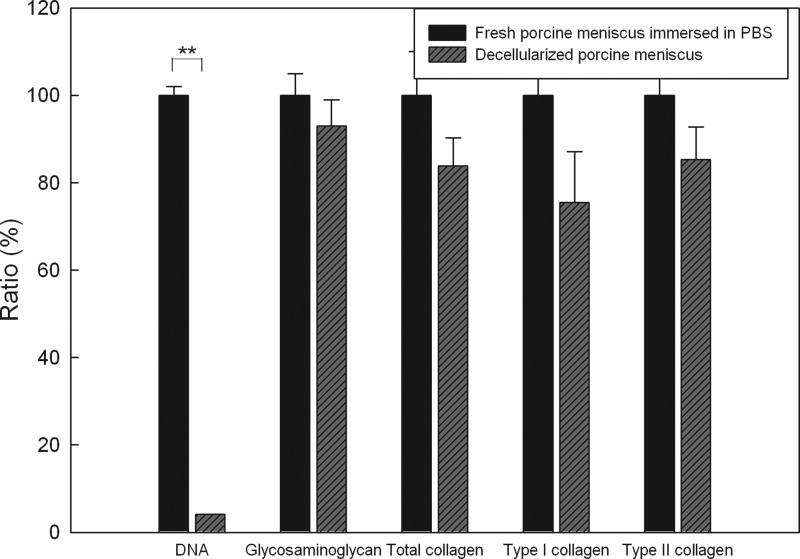

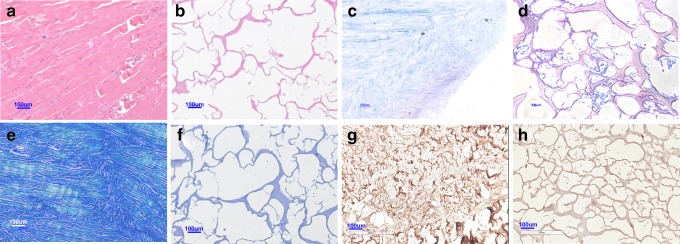

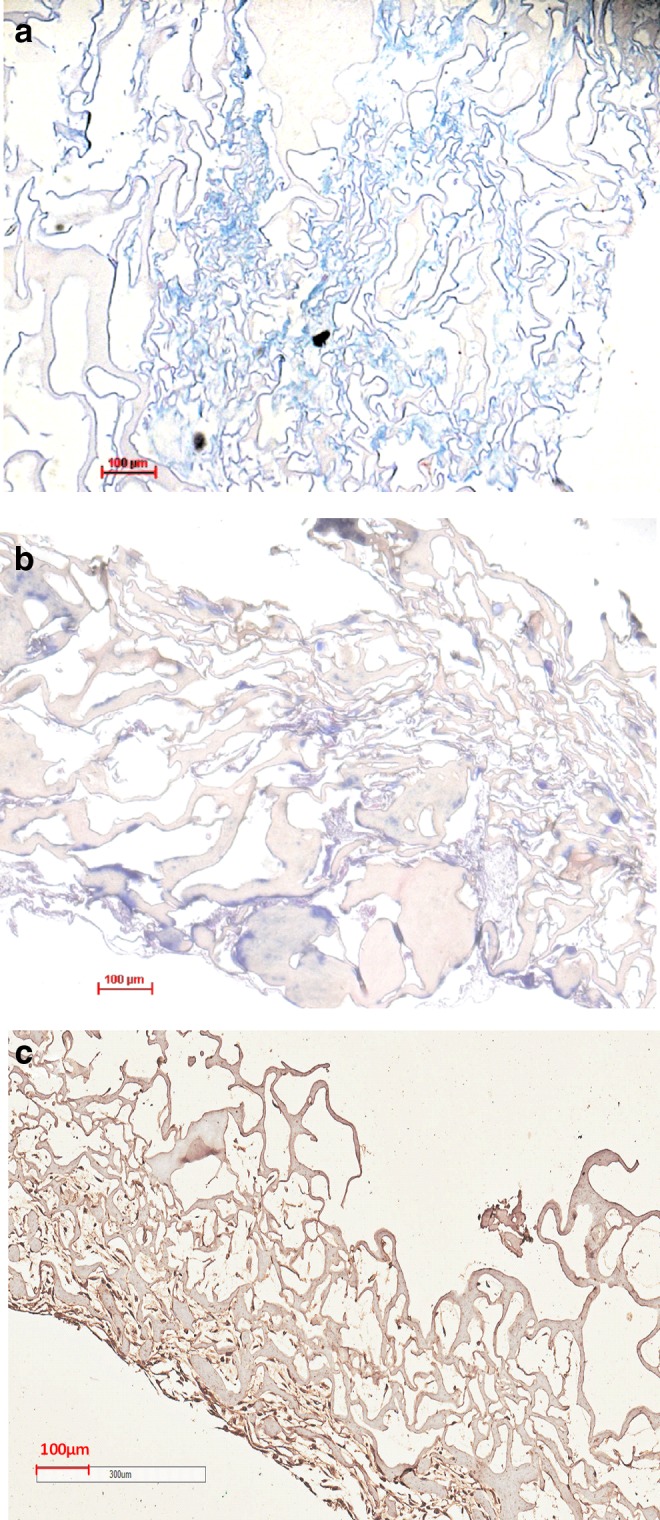

As shown in Figure 2, the content of DNA significantly decreased to 4.10%±0.03% (p<0.001) after treatment with formic acid for 2 h compared to fresh porcine menisci immersed in PBS, indicating the efficiency of the decellularization method. There was insignificant loss in the GAG content between fresh menisci and acellular ECM scaffolds (p=0.087). Amounts of total collagen and type II collagen decreased but still remained >80% in the acellular ECM scaffold (p=0.714 and 0.087, respectively). The decellularized scaffolds were further analyzed by histological staining. In a fresh porcine meniscus, H&E staining (Fig. 3a) showed that chondrocytes were round and embedded within lacunae. In contrast, no cells or cell fragments were present after decellularization as shown in Figure 3b. Alcian blue staining gave positive results for both fresh and decellularized menisci, indicating that GAG remained after decellularization (Figure 3c, d). Collagen was found to be a major component of the histoarchitecture in fresh porcine menisci and decellularized scaffolds through Masson's trichrome staining (Figure 3e, f). Figure 3g and h reveal the appearance of type II collagen after an immunohistochemical examination. Taken together, treatment with formic acid for 2 h efficiently removed most cellular materials while preserved the most ECM components. The decellularized scaffolds prepared using this method was further evaluated in vitro and in vivo.

FIG. 2.

Contents of DNA, glycosaminoglycan, total collagen, and types I and II collagen of porcine menisci treated with formic acid for 2 h are compared to the same weight of fresh menisci treated with PBS under the same processing steps. Values are presented as the mean±SD (n=3). **p<0.001 compared to fresh menisci treated with PBS.

FIG. 3.

Images of fresh porcine menisci (a, c, e, g), and those treated with formic acid for 2 h (b, d, f, h) after staining with hematoxylin and eosin (a, b), Alcian blue (c, d), Masson's trichrome (e, f), and immunohistochemistry for type II collagen (g, h). Scale bar: 100 μm at 100×magnification. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tec

Microstructure of acellular ECM scaffolds

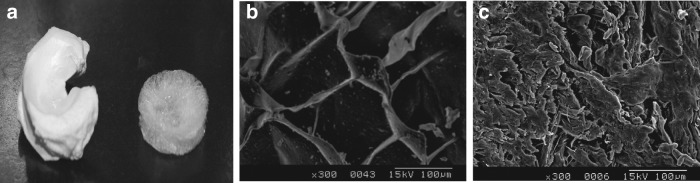

After decellularization of menisci by formic acid for 2 h, a sponge-like porous scaffold resulted. A macroscopic photograph is shown in the right of Figure 4a, and a fresh compact porcine meniscus is shown on the left of Figure 4a. Our fabrication method resulted in 3D scaffolds in which pores were open and interconnected with pore sizes ranging from 100–200 μm (Fig. 4b); while the fresh meniscus was very dense as shown in Figure 4c from SEM. The porosity of the acellular ECM scaffold was 85.76%±2.80% (n=4), and the percentage of water absorption was 1678.65%±65.17% (n=4).

FIG. 4.

Macroscopic view of a fresh porcine meniscus (a, left) and a decellularized one treated with formic acid for 2 h (a, right). Scanning electron microscopy photographs of a decellularized menisci treated with formic acid for 2 h (b) and fresh porcine menisci (c). Scale bar: 100 μm at 300×magnification (b, c).

In vitro studies

In vitro cytotoxicity test

After 2 days of culture, the Alamar blue assay shows there was no significant difference in fluorescence values between NIH 3T3 mouse fibroblast cells cultured with fresh medium (mean±SD: 33134.42±2573.10, n=6) and scaffold extract medium (mean±SD: 35195.14±5417.12, n=6) (p=0.167), indicating no cytotoxicity of the acellular ECM scaffold.

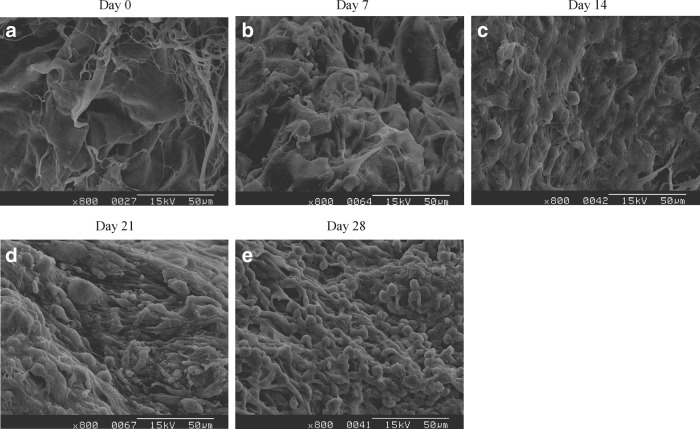

Chondrocyte attachment and viability

Human primary chondrocytes were seeded in the acellular ECM scaffold to evaluate cell proliferation and ECM synthesis. The morphology and distribution of chondrocytes in the scaffolds throughout the period of the experiment were observed by SEM. Figure 5 reveals that chondrocytes had a round or elliptic morphology and were well attached to the scaffolds, and some cells migrated and attached to interconnecting pores.

FIG. 5.

Scanning electron microscopy photographs of acellular extracellular matrix (ECM) scaffolds on which human chondrocytes were seeded for 0 (before cell seeding) (a), 7 (b), 14 (c), 21 (d), and 28 days (e). Scale bar: 50 μm at 800×magnification.

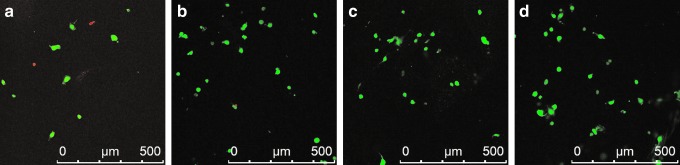

Figure 6 illustrated the live/dead cell staining. On day 7, most cells were stained with green fluorescence, except a few cells that had died. Afterward, green living cells were easily observed, and very few red dead cells appeared. These results indicated that human chondrocytes survived when cultured in the acellular ECM scaffold.

FIG. 6.

Fluorescent-stained photographs of live/dead cells when human chondrocytes were cultured in acellular ECM scaffolds for 7 (a), 14 (b), 21 (c), and 28 days (d). Scale bar: 500 μm. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tec

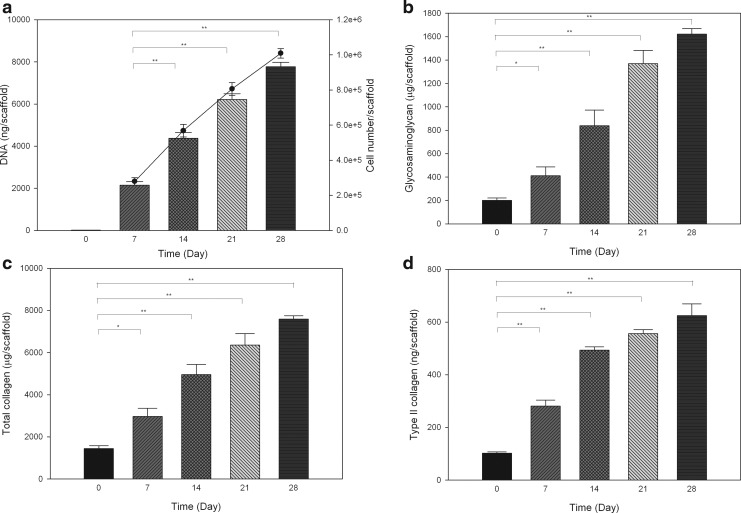

Biochemical analyses and histological staining of chondrocytes

The measurement of DNA, GAG, total collagen, and type II collagen per scaffold (Fig. 7a–d) was used to quantify the proliferation of chondrocytes and new ECM synthesis. The content of DNA, GAG, total collagen, and type II collagen that remained in the blank scaffold was shown as day 0. DNA contents showed 1.03-, 1.89-, and 2.62-fold increases compared with day 7 after chondrocytes were cultured in the ECM scaffold for 14, 21, and 28 days, respectively; whereas these results indicate increased cell numbers (black line in Fig. 7a). The total number of cells reached to 10.10×105 corresponded to a 10.10-fold increase over 28 days when 105 cells were initially seeded into the scaffold. Compared to blank scaffold, cells grown on the scaffolds synthesized 211.42±78.11, 638.18±133.96, 1168.84±114.94, and 1421.47±51.09 μg/scaffold GAG on days 7, 14, 21, and 28 when the values on that day were subtracted from blank scaffold, respectively. For total collagen relative to blank scaffold, there were increases of 1531.15±401.23, 3515.87±496.02, 4914.26±563.40, and 6141.65±212.75 μg/scaffold at days 7, 14, 21, and 28 when the values on that day were subtracted from blank scaffold, respectively. Regarding type II collagen content, 179.2±22.37, 391.2±14.04, 453.66±16.27, and 522.89±44.65 ng/scaffold was increased throughout the study period when the values on that day were subtracted from blank scaffold. In contrast, amounts of type I collagen were under the lower limit of quantitation quantity (LLOQ of <0.08 μg/mL). Human chondrocytes showed enhanced cell proliferation and synthesis of ECM including type II collagen and GAG when cultured in the acellular scaffolds.

FIG. 7.

Contents of DNA and cell number (black line) (a), glycosaminoglycan (b), total collagen (c), and type II collagen (d) in acellular ECM scaffolds (day 0) or on which human chondrocytes were cultured at different time points. Values are presented as the mean±SD (n=3). *p<0.05 and **p<0.001 versus DNA content on day 7 (a), and the amount of glycosaminoglycan, total collagen, and type II collagen on day 0 (b, c, d).

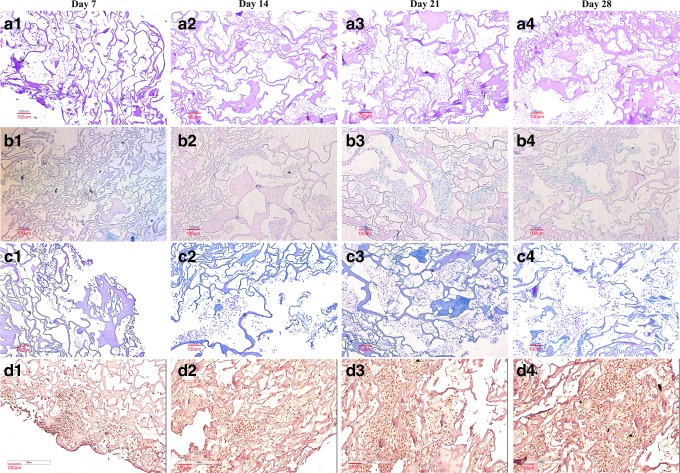

To confirm the specific morphology of chondrocytes and ECM secretion that occurred during the study period, the cell/scaffold constructs were evaluated by histological staining. Results showed that many chondrocytes with a round shape were evenly distributed (Fig. 8a1–a4). Increased labeling by Alcian blue (Fig. 8b1–b4), Masson's trichrome (Fig. 8c1–c4), and immunohistochemical staining (Fig. 8d1–d4) around cells indicates the deposition and new synthesis of GAG, total collagen, and type II collagen, respectively. The gradually increasing contents of GAG, total collagen, and type II collagen correlated well with the results of the DNA amount; concomitantly, these findings corresponded to the optical microscopic histological and SEM observations.

FIG. 8.

Hematoxylin and eosin (a1–a4), Alcian blue (b1–b4), Masson's trichrome (c1–c4), and immunohistochemical (d1–d4) staining images of acellular ECM scaffolds onto which human chondrocytes were seeded for 7 (a1, b1, c1, d1), 14 (a2, b2, c2, d2), 21 (a3, b3, c3, d3), and 28 days (a4, b4, c4, d4). Scale bar: 100 μm at 100×magnification. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tec

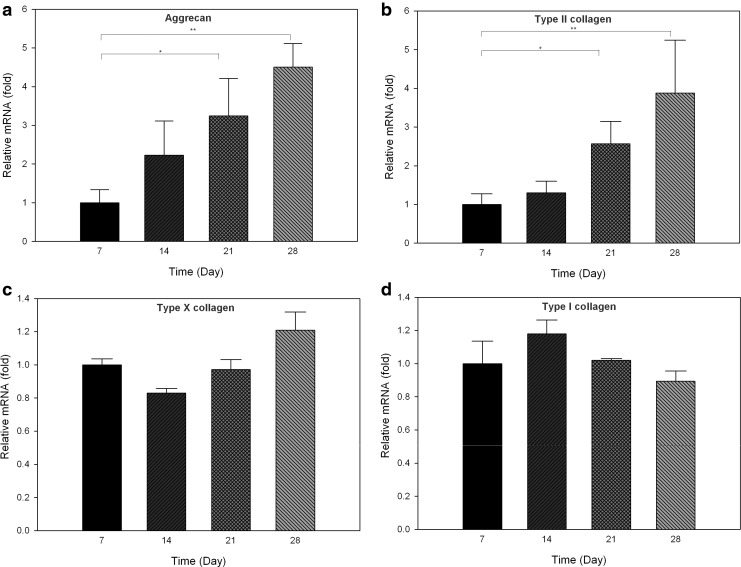

Expression of chondrocyte markers measured by quantitative real-time PCR

To evaluate the differentiation of chondrocytes seeded in the acellular ECM scaffold, changes in chondrogenic markers were determined by real-time PCR on days 7, 14, 21, and 28 (Fig. 9). The two positive markers of chondrogenesis, aggrecan, and type II collagen, significantly increased on days 21 (p<0.05) and 28 (p<0.001) compared with day 7. On the contrary, no significant change in fibroblastic marker type I collagen and hypertropic marker type X collagen compared to day 7 was observed (p=0.155 and 0.245, respectively). The gene expression results, together with that of biochemical quantification and histological staining indicated that human chondrocytes maintained their normal phenotypes, and cartilage-like tissue was engineered when cultured in acellular ECM scaffolds.

FIG. 9.

Gene expression levels of aggrecan (a), type II collagen (b), type X collagen (c), and type I collagen (d) in acellular ECM scaffolds seeded with human chondrocytes at different time points. The gene expression levels on days 14, 21, and 28 relative to day 7 were analyzed by comparative CT method using GAPDH as the internal control. Values are presented as the mean±SD (n=3). *p<0.05; **p<0.001 versus the value on day 7.

Chondrogenesis of bone marrow-derived hMSCs

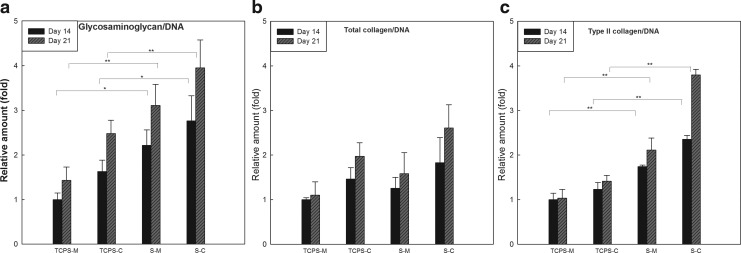

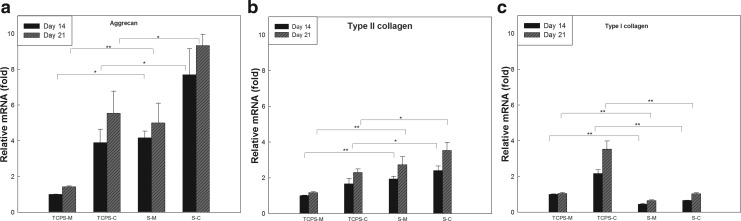

The differentiation of hMSCs on the acellular ECM scaffolds was evaluated by monitoring the protein accumulation of chondrogenic markers (Fig. 10) when hMSCs were cultured on acellular ECM scaffolds or TCPS and with growth medium or chondrogenic medium for 14 and 21 days. Compared to hMSCs cultured on TCPS with chondrogenic medium (TCPS-C) on day 14, hMSCs seeded in scaffold and chondrogenic medium (S-C) on days 14 and 21 synthesized greater amounts of GAG and type II collagen. Histological analysis showed the accumulation of GAG and type II collagen (Fig. 11). The gene expression of types I and II collagen and aggrecan was analyzed using quantitative real-time PCR. Compared with hMSCs cultured on TCPS-C on day 14, an increased gene expression of aggrecan and type II collagen in S-C was observed on days 14 and 21. Concomitantly, the expression of type I collagen, a dedifferentiation marker of chondrogenesis, was downregulated (Fig. 12). Interestingly, the hMSCs cultured in scaffolds without chondrogenic induction (S-M) also showed significantly greater amount of GAG and type II collagen, and higher expression of chondrogenic markers compared with TCPS-M on days 14 and 21, respectively. These results suggested that this acellular ECM scaffold not only promoted the growth of human chondrocytes, but also supported the chondrogenesis of hMSC.

FIG. 10.

Relative amounts of glycosaminoglycan/DNA (a), total collagen/DNA (b), and type II collagen/DNA (c) when bone marrow-derived human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) in various of culture conditions. hMSCs were cultured either in a monolayer (tissue culture polystyrene [TCPS]) or on acellular ECM scaffolds (S) and with either growth medium (M) or chondrogenic medium (C) for 14 and 21 days. The values were normalized to that when hMSCs were in a monolayer and with growth medium (TCPS-M) on day 14. Values are presented as the mean±SD (n=3). *p<0.05 and **p<0.001 versus the value of TCPS-M or TCPS-C on day 14.

FIG. 11.

Images of acellular ECM scaffolds seeded with bone marrow-derived hMSCs for 21 days and stained with Alcian blue (a), Masson's trichrome (b), and immunohistochemistry of type II collagen (c). Scale bar: 100 μm at 100×. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tec

FIG. 12.

Gene expression levels of aggrecan (a), type II collagen (b), and type I collagen (c) when bone marrow-derived hMSCs were cultured in a monolayer (TCPS) or on acellular ECM scaffolds (S) and with growth medium (M) or chondrogenic medium (C) for 14 and 21 days. The values were normalized to that when hMSCs were cultured in a monolayer and with growth medium (TCPS-M) on day 14. Values are presented as the mean±SD (n=3). The gene expression levels on various culture conditions relative to TCPS-M on day 14 were analyzed by comparative CT method using GAPDH as the internal control. *p<0.05 and **p<0.001 versus the value of TCPS-M or TCPS-C on day 14.

In vivo immunobiocompatibility study

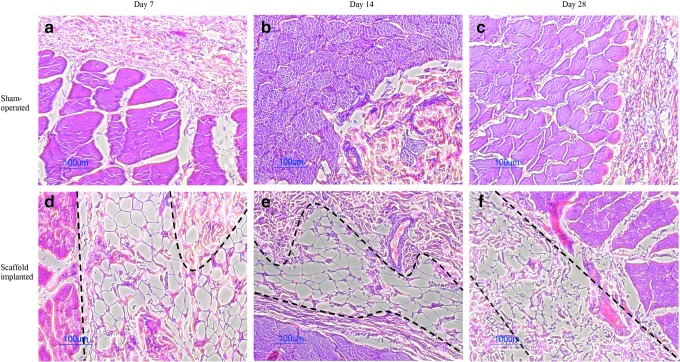

To determine the in vivo immunobiocompatibility of the acellular ECM scaffold, the scaffolds were subcutaneously implanted into immunocompetent rats for 7, 14, and 28 days. No inflammatory cell infiltration was detected in the implants (Fig. 13d–f). Scaffold structures are stable for over 14 days. At later time point (day 28), the resorption and turnover of the scaffolds were observed in vivo (Fig. 13f). The surrounding tissues of the implants showed no sign of inflammation and were comparable to the sham controls (Fig. 13a–c). With the completed removal of cells from the scaffold, immunogenic responses of the acellular tissue were also minimized.

FIG. 13.

Hematoxylin and eosin staining images of skin sections from Sprague Dawley rats with sham-operated (a–c) and subcutaneously implanted scaffold (d–f) on days 7, 14, and 28. Areas within the two black dashed lines indicate the implanted scaffolds. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tec

Discussion

One of the key components for tissue engineering is the scaffold.13 Recently, scaffolds fabricated with ECM materials have drawn much attention; in addition to providing temporary habitats for cells, ECM scaffolds offer a native environment and diverse physiological cues to promote cell growth. Nevertheless, it is difficult to construct a scaffold that has the same composition as that of in vivo ECM using conventional physicochemical methods; moreover, to mimic the complex structure of native cartilage is challenging. Consequently, decellularization of biological tissues has become an attractive strategy for obtaining ECM scaffolds. A variety of acellular tissues have been used for tissue engineering, including heart valves, blood vessels, skin, tendons, ligaments, SIS,29,46,47 UBS, and livers.20,22 However, the decellularization of dense and compact tissues such as cartilage and meniscus remains challenging.

Sandmann et al.48 decellularized human meniscus using SDS, ethanol, water, and PBS for 17 days. To shorten the processing time, menisci were processed with a multi-step decellularization by Stabile et al.37 Each dissected meniscus was placed in DNase/RNase-free water, EDTA, trypsin, FBS, Triton X-100, and peracetic acid. The acellular menisci demonstrated in vitro biocompatibility for murine NIH 3T3 embryonic fibroblast. Stapleton et al.49,50 decellularized menisci by exposing them to several freeze-thaw cycles and incubating them in hypotonic Tris buffer and SDS in hypotonic buffer plus protease inhibitors, nucleases, and hypertonic buffer followed by disinfection with peracetic acid. The menisci scaffold showed immunobiocompatibility, no evidence of the expression of the major xenogeneic epitope (galactose-α-1,3-galactose), and was capable of supporting the attachment and infiltration of human fibroblasts and porcine meniscal cells. However, a significant loss (59.4%) of GAG was observed with the reported method. The challenge of constructing acellular ECM scaffolds is to eliminate all immunogenic components while maintaining the ECM composition and biological activity at the same time to provide cell adhesion and growth; additionally, an easy and time-saving procedure is also preferred for product development.

Acid decellularization has been reported previously.29–31 The higher concentrations of acid solutions and shorter processing times were preferred to achieve the best decellularization effect. When Dong et al.51 decellularized bovine pericardia with acetic acid, most of the GAG was retained, but collagens and the strength were seriously damaged. Our studies also found that the collagen content was half of that of fresh menisci when treated with acetic acid for 2 h. These results indicate that acetic acid is not an ideal decellularization reagent due to its negative influence on collagen. In addition, peracetic acid is a common decellularization agent for porcine SIS and layers of the urinary bladder,52,53 and it was reported to be highly efficient at removing residual nucleic acids from thin tissues with minimal effects on the ECM composition at concentrations of 0.10–0.15%.30 However, here 0.15% peracetic had a limited decellularization effect on menisci in the first 2 h; furthermore, 15% peracetic acid treatment for 10 h decreased the DNA content to 4.68%±0.01%; while the amounts of collagen and GAG were respectively reduced to 44.98%±3.00% and 19.04%±4.01% compared to fresh menisci. Because of the dense architecture, it might be difficult for peracetic acid to permeate throughout the menisci in a short time. Prolonged treatment with peracetic acid, on the other hand, resulted in a compromised ECM. Formic acid treatment for 2 h effectively decellularized menisci while retaining the greatest proportion of the ECM. The mechanism of action of formic acid is most likely due to its high permeability through the dense architecture of menisci and caused the menisci swell to expose those embedded chondrocytes. Formic acid is a well-known decalcifying agent in histology of bone biopsies but was previously reported to cause DNA hydrolysis and degradation.54 With formic acid treatment for 2 h, the amount of DNA remained was 37.20±6.53 ng/mg in the dry menisci tissue. According to an accepted criterion for acellularity (less than 50 ng/mg dry tissue weight),55 formic acid-treated scaffold is considered as an acellular scaffold.

The present decellularization method was carried out with no surfactant treatment or enzymatic digestion, enabling a cost-effective and easy reproducible process compared to other decellularization procedures. No expensive recombinant enzymes were required, so the risk of inhomogeneous diffusion or insufficient washing out of reagents was avoided. With the gentle acid treatment and short processing time, the acellular menisci preserved GAG and collagen that are favorable for cell attachment and actively regulate diverse cellular communications. In addition, the high value of water uptake of the scaffold can be attributed to the high porosity and maintenance of HA. The scaffolds' hydrophilicity allowed the medium to reach the interior pores, and nutrients easily diffused to promote cell growth. As to the architecture, the scaffold had an interconnected porous structure to facilitate the mass transfer of oxygen and nutrients, and also provide sufficient space for cell growth. The 3D structure maintained the cell morphology and differentiation state of cultured chondrocytes. The structure and composition of the scaffolds were previously found to deeply affect the phenotype, attachment, and proliferation of cells. Unlike subcutaneous implantation in the in vivo immunobiocompatibility study, joint space is avascular and alymphatic and relatively immune privileged,25 so less damage is caused by immune cells and leading to slower degradation. Besides, the ECM produced rapidly by chondrocytes seeded in the scaffold compared to no cells incubation may be able to form a hyaline neocartilage in the hope of replacing defect tissue before scaffold degradation. Herein, the scaffold acts as a cell carrier and provides cell an environment to secrete ECM for neocartilage formation. Furthermore, the generated ECM can strengthen the mechanical property of cell-scaffold construct compared to scaffold without cells. Here, we also demonstrated this acellular scaffold derived from meniscus tissue promoted chondrocyte phenotype and supported chondrogenesis of hMSC. Compared with previous decellularization methods, our decellularization method is a time-saving, effective, and low cost process.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we developed a novel decellularization method with minimal deteriorative effects on the composition and functional characteristics of porcine menisci to prepare an acellular ECM scaffold for use in cartilage tissue engineering. The optimal scaffold with a 3D interconnected porous structure and high hydrophilicity was obtained when porcine menisci were treated with formic acid for 2 h. Compared with fresh porcine menisci, the content of DNA decreased to 4.10%±0.03%, and there was no significant damage to GAG or collagen. Acellular ECM scaffolds with preservation of ECM not only provided native-mimic environment for promoting differentiation of human chondrocytes and secrete new ECM, but also provided signals to drive hMSCs toward chondrogenesis. The acellular ECM scaffold proved to be biocompatible and highly feasible for clinical use serving as a matrix for tissue regeneration.

Acknowledgments

Financial support from the National Science Council of ROC is highly appreciated. The authors also acknowledge the support of the International College of Fellows for Biomaterials Science and Engineering, which provided funds for Y.-C.C. to participate in the Summer Exchange Program at the New Jersey Center for Biomaterials.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Felson D.T., Lawrence R.C., Dieppe P.A., Hirsch R., Helmick C.G., Jordan J.M., Kington R.S., Lane N.E., Nevitt M.C., Zhang Y., Sowers M., McAlindon T., Spector T.D., Poole A.R., Yanovski S.Z., Ateshian G., Sharma L., Buckwalter J.A., Brandt K.D., and Fries J.F. Osteoarthritis: new insights—part 1: the disease and its risk factors. Ann Intern Med 133, 635, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Felson D.T., and Zhang Y. An update on the epidemiology of knee and hip osteoarthritis with a view to prevention. Arthritis Rheum 41, 1343, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spiller K.L., Maher S.A., and Lowman A.M. Hydrogels for the repair of articular cartilage defects. Tissue EngPart B Rev 17, 281, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hootman J.M., and Helmick C.G. Projections of US prevalence of arthritis and associated activity limitations. Arthritis Rheum 54, 226, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chung C., and Burdick J. Engineering cartilage tissue. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 60, 243, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schulz R.M., and Bader A. Cartilage tissue engineering and bioreactor systems for the cultivation and stimulation of chondrocytes. Eur Biophys J 36, 539, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mollon B., Kandel R., Chahal J., and Theodoropoulos J. The clinical status of cartilage tissue regeneration in humans. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 21, 1824, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steadman J.R., Rodkey W.G., and Rodrigo J.J. Microfracture: surgical technique and rehabilitation to treat chondral defects. Clin Orthop Relat Res S362, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hambly K., Bobic V., Wondrasch B., Van Assche D., and Marlovits S. Autologous chondrocyte implantation postoperative care and rehabilitation: science and practice. Am J Sports Med 34, 1020, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harris J.D., Siston R.A., Brophy R.H., Lattermann C., Carey J.L., and Flanigan D.C. Failures, re-operations, and complications after autologous chondrocyte implantation—a systematic review. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 19, 779, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Temenoff J.S., and Mikos A.G. Review: tissue engineering for regeneration of articular cartilage. Biomaterials 21, 431, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuo C.K., Li W.J., Mauck R.L., and Tuan R.S. Cartilage tissue engineering: its potential and uses. Curr Opin Rheumatol 18, 64, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Langer R., and Vacanti J.P. Tissue engineering. Science 260, 920, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Randolph M.A., Anseth K., and Yaremchuk M.J. Tissue engineering of cartilage. Clin Plast Surg 30, 519, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brittberg M., Lindahl A., Nilsson A., Ohlsson C., Isaksson O., and Peterson L. Treatment of deep cartilage defects in the knee with autologous chondrocyte transplantation. N Engl J Med 331, 889, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin Y.-J., Yen C.-N., Hu Y.-C., Wu Y.-C., Liao C.-J., and Chu I.M. Chondrocytes culture in three-dimensional porous alginate scaffolds enhanced cell proliferation, matrix synthesis and gene expression. J Biomed Mater Res A 88A, 23, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vinatier C., Mrugala D., Jorgensen C., Guicheux J., and Noël D. Cartilage engineering: a crucial combination of cells, biomaterials and biofactors. Trends Biotechnol 27, 307, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benya P.D., and Shaffer J.D. Dedifferentiated chondrocytes reexpress the differentiated collagen phenotype when cultured in agarose gels. Cell 30, 215, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crapo P.M., Gilbert T.W., and Badylak S.F. An overview of tissue and whole organ decellularization processes. Biomaterials 32, 3233, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Badylak S. Xenogeneic extracellular matrix as a scaffold for tissue reconstruction. Transpl Immunol 12, 367, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beatty M.W., Ojha A.K., Cook J.L., Alberts L.R., Mahanna G.K., Iwasaki L.R., and Nickel J.C. Small intestinal submucosa versus salt-extracted polyglycolic acid-poly-l-lactic acid: a comparison of neocartilage formed in two scaffold materials. Tissue Eng 8, 955, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gilbert T., Sellaro T., and Badylak S. Decellularization of tissues and organs. Biomaterials 27, 3675, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taylor D., and Harald O. Decellularization and recellularization of organs and tissues. 2012. EP 2413946 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choi J.S., Kim B.S., Kim J.Y., Kim J.D., Choi Y.C., Yang H.J., Park K., Lee H.Y., and Cho Y.W. Decellularized extracellular matrix derived from human adipose tissue as a potential scaffold for allograft tissue engineering. J Biomed Mater Res A 97 A, 292, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elder B.D., Eleswarapu S.V., and Athanasiou K.A. Extraction techniques for the decellularization of tissue engineered articular cartilage constructs. Biomaterials 30, 3749, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Makris E.A., Hadidi P., and Athanasiou K.A. The knee meniscus: structure–function, pathophysiology, current repair techniques, and prospects for regeneration. Biomaterials 32, 7411, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamasaki T., Deie M., Shinomiya R., Yasunaga Y., Yanada S., and Ochi M. Transplantation of meniscus regenerated by tissue engineering with a scaffold derived from a rat meniscus and mesenchymal stromal cells derived from rat bone marrow. Artif Organs 32, 519, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maier D., Braeun K., Steinhauser E., Ueblacker P., Oberst M., Kreuz P.C., Roos N., Martinek V., and Imhoff A.B. In vitro analysis of an allogenic scaffold for tissue-engineered meniscus replacement. J Orthop Res 25, 1598, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Badylak S.F., Tullius R., Kokini K., Shelbourne K.D., Klootwyk T., Voytik S.L., Kraine M.R., and Simmons C. The use of xenogeneic small intestinal submucosa as a biomaterial for Achille's tendon repair in a dog model. J Biomed Mater Res 29, 977, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cobb M.A., Badylak S.F., Janas W., and Boop F.A. Histology after dural grafting with small intestinal submucosa. Surg Neurol 46, 389, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gilbert T.W., Wognum S., Joyce E.M., Freytes D.O., Sacks M.S., and Badylak S.F. Collagen fiber alignment and biaxial mechanical behavior of porcine urinary bladder derived extracellular matrix. Biomaterials 29, 4775, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Young-Yo K., Sah R.L.Y., Doong J.Y.H., and Grodzinsky A.J. Fluorometric assay of DNA in cartilage explants using Hoechst 33258. Anal Biochem 174, 168, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pal S., Tang L.H., Choi H., Habermann E., Rosenberg L., Roughley P., and Poole A.R. Structural changes during development in bovine fetal epiphyseal cartilage. Coll Relat Res 1, 151, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mandal B.B., Park S.-H., Gil E.S., and Kaplan D.L. Multilayered silk scaffolds for meniscus tissue engineering. Biomaterials 32, 639, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moriguchi Y., Tateishi K., Ando W., Shimomura K., Yonetani Y., Tanaka Y., Kita K., Hart D.A., Gobbi A., Shino K., Yoshikawa H., and Nakamura N. Repair of meniscal lesions using a scaffold-free tissue-engineered construct derived from allogenic synovial MSCs in a miniature swine model. Biomaterials 34, 2185, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Calvi E.N.C., Nahas F.X., Barbosa M.V., Calil J.A., Ihara S.S.M., Silva M.S., de Franco M.F., and Ferreira L.M. An experimental model for the study of collagen fibers in skeletal muscle. Acta Cir Bras 27, 681, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stabile K.J., Odom D., Smith T.L., Northam C., Whitlock P.W., Smith B.P., Van Dyke M.E., and Ferguson C.M. An acellular, allograft-derived meniscus scaffold in an ovine model. Arthroscopy 26, 936, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zheng X., Yang F., Wang S., Lu S., Zhang W., Liu S., Huang J., Wang A., Yin B., Ma N., Zhang L., Xu W., and Guo Q. Fabrication and cell affinity of biomimetic structured PLGA/articular cartilage ECM composite scaffold. J Mater Sci Mater Med 22, 693, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Terribas E., Garcia-Linares C., Lázaro C., and Serra E. Probe-based quantitative PCR assay for detecting constitutional and somatic deletions in the NF1 gene: application to genetic testing and tumor analysis. Clin Chem 59, 928, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Livak K.J., and Schmittgen T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-ΔΔCT method. Methods 25, 402, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ragetly G.R., Griffon D.J., Lee H.-B., Fredericks L.P., Gordon-Evans W., and Chung Y.S. Effect of chitosan scaffold microstructure on mesenchymal stem cell chondrogenesis. Acta Biomater 6, 1430, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen Y.L., Chen H.C., Chan H.Y., Chuang C.K., Chang Y.H., and Hu Y.C. Co-conjugating chondroitin-6-sulfate/dermatan sulfate to chitosan scaffold alters chondrocyte gene expression and signaling profiles. Biotechnol Bioeng 101, 821, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guo L., Kawazoe N., Fan Y., Ito Y., Tanaka J., Tateishi T., Zhang X., and Chen G. Chondrogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells on photoreactive polymer-modified surfaces. Biomaterials 29, 23, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lu H., Hoshiba T., Kawazoe N., and Chen G. Comparison of decellularization techniques for preparation of extracellular matrix scaffolds derived from three-dimensional cell culture. J Biomed Mater Res A 100 A, 2507, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lu H., Hoshiba T., Kawazoe N., and Chen G. Autologous extracellular matrix scaffolds for tissue engineering. Biomaterials 32, 2489, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kropp B.P., Rippy M.K., Badylak S.F., Adams M.C., Keating M.A., Rink R.C., and Thor K.B. Regenerative urinary bladder augmentation using small intestinal submucosa: urodynamic and histopathologic assessment in long-term canine bladder augmentations. J Urol 155, 2098, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Prevel C.D., Eppley B.L., McCarty M., Jackson J.R., Voytik S.L., Hiles M.C., Badylak S.F., and Cooley B.C. Experimental evaluation of small intestinal submucosa as a microvascular graft material. Microsurgery 15, 586, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sandmann G.H., Eichhorn S., Vogt S., Adamczyk C., Aryee S., Hoberg M., Milz S., Imhoff A.B., and Tischer T. Generation and characterization of a human acellular meniscus scaffold for tissue engineering. J Biomed Mater Res A 91, 567, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stapleton T.W., Ingram J., Katta J., Knight R., Korossis S., Fisher J., and Ingham E. Development and characterization of an acellular porcine medial meniscus for use in tissue engineering. Tissue Eng Part A 14, 505, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stapleton T.W., Ingram J., Fisher J., and Ingham E. Investigation of the regenerative capacity of an acellular porcine medial meniscus for tissue engineering applications. Tissue Eng Part A 17, 231, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dong X., Wei X., Yi W., Gu C., Kang X., Liu Y., Li Q., and Yi D. RGD-modified acellular bovine pericardium as a bioprosthetic scaffold for tissue engineering. J Mater Sci Mater Med 20, 2327, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hodde J., Janis A., Ernst D., Zopf D., Sherman D., and Johnson C. Effects of sterilization on an extracellular matrix scaffold: part I. Composition and matrix architecture. J Mater Sci Mater Med 18, 537, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hiles M.C., Badylak S.F., Geddes L.A., Kokini K., and Morff R.J. Porosity of porcine small-intestinal submucosa for use as a vascular graft. J Biomed Mater Res 27, 139, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lin Y.C., Tan F.j., Marra K.G., Jan S.S., and Liu D.C. Synthesis and characterization of collagen/hyaluronan/chitosan composite sponges for potential biomedical applications. Acta Biomater 5, 2591, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Soto-Gutierrez A., Wertheim J.A., Ott H.C., and Gilbert T.W. Perspectives on whole-organ assembly: moving toward transplantation on demand. J Clin Invest 122, 3817, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]