Abstract

Research in behavioral economics suggests that certain circumstances, such as large numbers of complex options or revisiting prior choices, can lead to decision errors. This paper explores the enrollment decisions of Medicare beneficiaries in the Medicare Advantage (MA) program. During the time period we study (2007–2010), private fee-for-service (PFFS) plans offered enhanced benefits beyond those of traditional Medicare (TM) without any restrictions on physician networks, making TM a dominated choice relative to PFFS. Yet more than three quarters of Medicare beneficiaries remained in TM during our study period. We analyze the role of status quo bias in explaining this pattern of enrollment. Our results suggest that status quo bias plays an important role; the rate of MA enrollment was significantly higher among new Medicare beneficiaries than among incumbents. These results illustrate the importance of the choice environment that is in place when enrollees first enter the Medicare program.

Keywords: Health insurance choice, Medicare, Status quo bias

1. Introduction

The question of the role of consumer choice in health insurance markets has featured prominently in recent health policy debates, with advocates of expanded choice arguing that increasing plan choices will better match insurance products with the diverse preferences of consumers. Consumer choice of health plans is a significant feature in the current Medicare Advantage program, the Medicare Part D prescription drug benefit, and the health insurance exchanges created by the Affordable Care Act. However, a growing body of research in behavioral economics has documented decision-making biases among consumers. Recent empirical work in health economics suggests that choices made in health insurance markets where there are many complex options may result in errors (Abaluck and Gruber, 2011; Frank and Lamiraud, 2009). Nevertheless, it can be challenging to identify circumstances where complexity clearly results in errors: two recent examples are McWilliams et al. (2011) and Sinaiko and Hirth (2011).

In this paper, we explore the enrollment decisions of Medicare beneficiaries in the Medicare Advantage (MA) program. MA (also known as Medicare Part C) offers all Medicare beneficiaries the opportunity to join a privately run health plan instead of enrolling in the government-run, traditional Medicare (TM) program. Following program changes enacted through the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003, the MA program has seen tremendous growth: enrollment more than doubled from 7.1 M in 2006 to 16.3 M in 2014, and currently represents 31% all Medicare beneficiaries (Centers for Medicare & Medicare Services, 2006, 2014b). A principal source of this growth has to do with the generous payments offered to MA plans, often significantly higher than those made in the TM program, which have allowed MA plans to offer enhanced benefits for enrollees including reduced cost sharing, partial or complete refunds of the Medicare Part B and/or Part D premiums, and additional services such as vision care.1

The increase in MA plans enrollment since the mid-2000s was accompanied by an increase in MA plan choices, and in particular, the availability of private fee-for-service (PFFS) plans. Unlike other plan offerings in the MA program that employ selective contracting and negotiate prices with providers, during the 2000s PFFS plans were not required to maintain a provider network. In addition, these plans were granted “deeming authority” in 2003, giving them the ability to impose prices from the TM fee schedule on providers (McGuire et al., 2011). The Medicare Improvements for Patients and Providers Act (MIPPA) of 2008 changed the rules for PFFS plans and their role in the MA program starting in 2011, including the requirement that these plans have a physician network. We focus on the period before these changes were implemented, 2007–2010. The advent and expansion of this PFFS option during these years offers an opportunity to better understand decision-making errors on the part of beneficiaries.

Like other MA plans, PFFS plans offer enhanced benefits beyond those of TM: reduced premiums for Medicare Part B or Part D, reduced cost sharing requirements, or additional benefits (e.g., vision coverage). In the subset of counties we focus on in this paper, payment rates were particularly generous relative to TM, making MA even more attractive than in other markets. Because PFFS plans offered these additional benefits without any restrictions on access to physicians, we argue that in these counties PFFS plans were in effect a dominant alternative in comparison to TM. That is, for all possible health states for all beneficiaries, TM was no better than PFFS on some dimensions (e.g., provider choice) and worse than PFFS on other dimensions (e.g., cost sharing).2 For these reasons, neoclassical economic theory predicts that all beneficiaries should have preferred the PFFS option to TM. (It is less clear whether beneficiaries should have preferred a managed plan, such as an HMO or PPO, to a PFFS plan. These plans restrict provider choice, but may also pass on additional benefits, achieved from the savings due to their selective contracting efforts.)

In spite of these expectations, more than three quarters of these Medicare beneficiaries remained in TM during our study period, and only 4–5% joined PFFS. Several explanations exist for why beneficiaries left “money on the table” and enrolled in TM instead of a PFFS plan. First, status quo bias in health plan enrollment, observed in previous empirical work (Sinaiko et al., 2013), may result in low rates of plan switching among incumbent Medicare beneficiaries already enrolled in TM. Second, limited cognitive capacity may make it difficult for some beneficiaries to recognize that the TM option is dominated by PFFS (McWilliams et al., 2011). Third, the number of choices offered by MA insurers, together with the large number of dimensions to evaluate with each option, may create frictions in beneficiaries’ decision making, leaving them in TM. Finally, the preference for TM may also be explained by the complexity of the decision beneficiaries face. The differences between TM and MA may be unobservable or difficult to measure. For example, MA insurers are allowed to modify the coverage rules of their policies across dozens of dimensions. The TM coverage rules, while also complicated, may seem simpler in comparison. Medicare beneficiaries may find it daunting to compare these options across so many categories of coverage, leading them to opt instead for TM.

We analyze the role of status quo bias in decisions by Medicare beneficiaries to enroll in TM instead of MA. We compare the enrollment decisions of new 65-year-old Medicare beneficiaries to those of incumbent beneficiaries enrolled in TM in the prior year. The plan choice by a 65 year-old represents a “forced choice” situation, where an active choice is required. If status quo bias plays a role in the selection of the dominated plan, we should see higher rates of TM enrollment among the incumbents compared to the new beneficiaries.3

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the previous literature on choice inconsistency, and provides some background on the Medicare Advantage program. Section 3 describes the data used in our study and presents our analytic approach. Section 4 presents our results, which indicate that status quo bias plays an important role in the choice of MA plans. Section 5 concludes.

2. Background

2.1. Consumers, health plans, and choice inconsistency

In standard consumer theory, expanding the number of choices makes it more likely that consumers will choose a product that matches their preferences. Greater choice promotes price and quality competition, leading to improved products at a given price (Bundorf et al., 2012; Salop, 1979). Standard theory also recognizes that consumer search is costly. Rational consumers search individually until the costs of additional searching outweigh its expected benefits. More choice may also confer other benefits, such as a sense of greater autonomy and control.

A growing literature in psychology and economics questions whether and in what contexts consumers make decisions according to the rational choice model, which is a critical assumption underlying the theory described above. One important idea is status quo bias, first identified by Samuelson and Zeckhauser (1988), which posits that certain choices are prone to frictions. While the standard economic model of consumer choice offers some explanations for this behavior, Samuelson and Zeckhauser conclude that the bias is more likely the result of psychological deviations from this model. Loss aversion as well as “anchoring” effects may play a role: the status quo option may win out over other options because it holds an asymmetric position in the list of choices. Psychological biases around commitment also provides a compelling explanation for the phenomenon, such as seeking to justify past choices by continuing to commit to them in the present, avoidance from the “decision regret” from outcomes that are the consequence of action versus inaction, cognitive dissonance (a desire for consistency in one’s actions), and a deference to one’s own past decisions as a guide to present and future choices.

The perspective that “more choice is better” has largely guided empirical work on health insurance plan choices, which focuses on how price and product attributes affect choice. While there are a number of studies on the price elasticity of health plan choice, search costs and switching costs have received less attention in this literature. Several of the papers that have considered this topic in private insurance settings find evidence consistent with status quo bias. Royalty and Solomon (1999) estimate models of price response in health plan choice under employer-sponsored insurance and find that consumers who are likely to face low switching costs (e.g., younger employees, new hires, and those with no chronic conditions) respond more to prices in making a health plan choice. Strombom et al. (2002) and Handel (2013) also present evidence of status quo bias among enrollees with employer-sponsored health insurance coverage. Sinaiko and Hirth (2011) investigate a case of enrollees faced with a clearly dominated plan choice. In this case, inertia was associated with at least a portion of these consumers choosing to remain in the dominated plan option.

Another branch of recent empirical work suggests that consumer choices in health insurance markets with large numbers of choices may result in errors. Using data from Switzerland, Frank and Lamiraud (2009) find an inverse relationship between the decision to revisit health care plan choice and the number of plan choices, suggesting that consumers may suffer from choice overload. A number of papers have focused on the quality of consumer enrollment decisions in the Medicare Part D program. Abaluck and Gruber (2011) find that Part D enrollees overemphasize the importance of plan premiums, and under-emphasize expected out-of-pocket costs, when making their plan choices. Similarly, Heiss et al. (2010) present evidence that Part D enrollees overemphasize their current drug utilization when making choices. Ketcham et al. (2012) use longitudinal data to demonstrate that at least some Part D enrollees were able to improve their choices in their second year of the program. Abaluck and Gruber (2013) use more comprehensive data over a longer time period to reach the opposite conclusion, documenting significant foregone savings in the program and demonstrating that inertia in plan choices plays an important but not an exclusive role in this behavior among enrollees. These errors on the part of beneficiaries also have implications for the supply side; Ericson (2012) finds that Part D insurers are able to exploit this inertia in decision-making, raising prices on existing enrollees while introducing cheaper alternative plans for new enrollees. This suggests that decision-making errors could become costlier over time.

The literature on choice of health plan within the MA program has predominantly focused on the issue of favorable selection into MA from TM on the basis of health care needs (Riley and Zarabozo, 2006). However, the question of whether beneficiaries make sub-optimal choices has begun to be addressed in MA as well. McWilliams et al. (2011) use data from the Health and Retirement Study to demonstrate choice overload among beneficiaries; the probability of MA enrollment was lower in markets with a larger number of MA plans available, relative to markets with a smaller number of MA plans. They also find that beneficiaries with impaired cognition were less likely to recognize and to be responsive to increases in MA plan benefit generosity. Sinaiko et al. (2013) investigate the MA enrollment decisions of Medicare beneficiaries from Miami-Dade County, and find evidence of status quo bias; beneficiaries new to Medicare are much more likely to enroll in an MA plan in that market (where MA penetration is quite high) than are incumbent beneficiaries.

2.2. The Medicare Advantage program

Private plans began to play a role in the Medicare program with the passage of the Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act (TEFRA) in 1982. Starting in 1985, Medicare has contracted with insurers willing to offer care to enrollees on a prospective basis. The rationale for the program was the potential for private managed care plans to provide better, more coordinated care to enrollees than what is available in TM, and to realize cost savings for the federal government. Plans are required to provide benefits that are actuarially equivalent to the standard TM benefit package.

The number of private plan choices has varied over the history of the MA program, and during the second half of the 2000s, the time period under study here, Medicare beneficiaries faced the largest and richest set of options in the program’s history. First, and most obviously, beneficiaries could have enrolled in TM. Because of holes in the basic Medicare benefit package, most of these enrollees also enroll in supplemental coverage (either through a former employer, by purchasing a Medigap insurance product, or through eligibility for Medicaid). Many enrollees also purchase a separate prescription drug product through Part D of Medicare. Alternately, beneficiaries could have chosen an MA plan, with or without Part D drug coverage. Within MA they could have chosen an HMO or PPO plan that engaged in selective contracting, negotiating prices with a network of health care providers. They could have also opted for a PFFS plan, which, because of its ability to impose the TM fee schedule on providers, did not engage in selective contracting or maintain a provider network. All MA plans offered cost sharing terms that were more generous than TM alone.

MA plan generosity is determined in part by rates of payment by Medicare to the plans. The MA payment rules for each county are set using a complicated formula that involves both administratively set rates and lagged measures of fee-for-service spending in the county (Biles et al., 2009). These rules have led to a significant amount of variation in the level of MA benefit generosity across counties.4

Important to this analysis are the details around payment rates in so-called “floor” counties.5 These floor rates were introduced to encourage MA options in highly concentrated markets (such as those in rural areas) where insurers found it difficult to bargain with providers, and were legislatively set to be more generous than MA payment rates in non-floor counties. Insurers embraced PFFS plans for these markets. Thus, while beneficiaries in PFFS plans across the US faced no restrictions on provider choices, in floor counties the PFFS benefits were, due to competitive pressures among insurers to pass through more generous payments to beneficiaries, certainly more generous than those provide through TM. To better isolate choice environments where the PFFS option clearly dominated TM, we focus our analyses on beneficiaries residing in these floor counties.

With the passage of MIPPA in 2008 and its imposition of network requirements on PFFS plans beginning in 2011, insurers withdrew many of their PFFS products from the market. Although PFFS enrollment currently constitutes a relatively small percentage of the MA market, the significant role these plans played in the MA program offer an opportunity to evaluate the role that dominated choices play in markets for health insurance.

3. Data and methods

3.1. Data

The data used in this analysis come from several sources. First, we use a 100% sample of Medicare enrollment data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), for the years 2007–2010. This file contains information on the age, race (black/non-black), sex, dual-eligible status, original reason for Medicare entitlement, and state and county of residence for every beneficiary. We separate this file into two samples of beneficiary-year observations: new entrants to Medicare aged 65 as of January of each calendar year, and incumbent beneficiaries aged 66 and older in January of each year. We do not study Medicare beneficiaries under the age of 65, whose MA enrollment rates are generally much lower than those of beneficiaries who qualify for the program due to old age, and many of whom (e.g., the disabled) likely have different set of considerations in plan choice than do old-age beneficiaries.

Second, for those beneficiaries who enrolled in an MA plan, we use the CMS Enrollment Database to identify their plan type (HMO, PPO, PFFS, other). Third, we employ inpatient hospital, outpatient hospital and physician/supplier claims for all TM enrollees, to generate 70 risk adjustment variables used by CMS in their “Hierarchical Condition Categories” model, which is used to adjust capitation payments to MA plans (Centers for Medicare & Medicare Services, 2007a). Because of data limitations, these claims are only available for a 20 percent random sample of beneficiaries who have been enrolled in TM for at least one year (i.e., beneficiaries aged 66 and older.) We analyze each beneficiary’s claims from the prior calendar year to code these variables. Fourth, we employ several publicly available data files from CMS: county-year data on MA plan offerings (Centers for Medicare & Medicare Services, 2007–2010a), county-year MA benchmark payment rates (Centers for Medicare & Medicare Services, 2007–2010d), county-year average TM spending and risk score data (Centers for Medicare & Medicare Services, 2007b, 2008–2010), county-year average MA capitation payment and risk score data (Centers for Medicare & Medicare Services, 2007–2010c), and plan-county-year Medicare Advantage enrollment counts (Centers for Medicare & Medicare Services, 2007–2010b).

Finally, we use estimates obtained from CMS of the out of pocket cost (OOPC) of each MA plan option, as well as the OOPC associated with TM. These OOPC estimates are calculated each year by CMS, and are presented to prospective MA enrollees shopping for coverage on the “Medicare Options Compare” website. The estimates are calculated based on a 2-year rolling sample of utilization records from TM enrollees in the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS), which CMS then applies to the benefit structure of each MA plan (along with TM) to come up with an OOPC estimate for each plan. Separate estimates are prepared for five health categories (using the self-reported health item from the MCBS), and six age categories (less than 65, 65–69, 70–74, 75–79, 80–84, 85-plus). We restrict attention to OOPC estimates for PFFS plans.

To evaluate the generosity of MA plan options at the county-level, we summarize these health-age-plan-level OOPC estimates in the following way. We first take a weighted average across the health status groups to collapse the estimates down to age groups for each plan, using the percentage of MCBS enrollees from that year’s survey as the weights. We then use the publicly available plan-county-year enrollment data described above to generate a county-weighted average OOPC estimate for each age group, county, and year.6 We perform a similar set of calculations for TM.7 Finally, we subtract the TM OOPC estimate from the MA OOPC estimate to produce a measure of the cost of joining MA in each county.

Our OOPC measure is net of premium. We also measure the premium associated with each plan, and how it differs from the Medicare Part B premium. A plan’s premium does not vary by enrollee age or health status, but we again construct an enrollment-weighted average of the premiums for all plans offered in each county. We also subtract the TM Part B premium from the calculated MA premium. The premium term and non-premium OOPC term enter separately in our regression models.

We note a few limitations of the OOPC estimates. While others have relied on these OOPC estimates (Dunn, 2010; McWilliams et al., 2011), they imperfectly capture MA benefit generosity. They are estimated using a relatively small sample of TM beneficiaries who appear in the MCBS, and do not capture the risk distribution realized by each plan. More importantly, the estimates do not capture any changes in health care demand related to the plan’s benefit structure (i.e., moral hazard). And our aggregation of these plan, age, and health status-level estimates to the county level to fit with our analysis introduces additional measurement error. Nevertheless, these measures are a useful measure of the relative generosity of the plans offered in each county.

3.2. Study population

From the set of beneficiaries aged 65 and older that were enrolled in Medicare as of January of each calendar year, we select the sample of beneficiaries residing in counties where the MA benchmark payment rate is set to either the urban or rural “floor” amount for all 4 years under study. We exclude MA enrollees in non-HMO/PPO/PFFS plans (e.g., cost-based plans), which are not marketed in any significant way to beneficiaries and have small enrollment rates. We exclude enrollees of Special Needs Plans, which are restricted to those with chronic conditions, those who are institutionalized, or those dually eligible for Medicaid. Some employers offer MA plans exclusively to their retirees, these enrollees are excluded from the study population as well. Finally, we drop cases from counties where enrollees lack a choice of at least one HMO/PPO plan and at least one PFFS plan.

Since Medicare beneficiaries also enrolled in Medicaid have little to no cost sharing when enrolled in TM, we exclude these dual-eligible beneficiaries from both samples. From the age-66-plus sample, we drop cases not enrolled in TM in the prior year: we are only interested in the MA decision-making of beneficiaries not currently in the program. We also drop those with any nursing home utilization in the prior year, and those who reside in a county without at least one MA plan option.

After these restrictions, our full analysis sample contains 54.6 M beneficiary observations. We run some regressions separately on the set of 65-year-olds and those 66-plus: those samples contain 4.3 and 50.3 M beneficiary-year observations, respectively.

3.3. Methods

We estimate several regression models to examine the plan choice of beneficiary i in market m and year t between three broad enrollment options: PFFS (denoted by the indicator variable Aimt), managed MA plans (HMO or PPO, denoted by the indicator variable Bimt), and TM (denoted by the indicator variable Cimt). We specify the plan choice as a multinomial logit function, i.e.,

where Xi contains beneficiary-level characteristics (sex, black/non-black, and age group indicators: 66–69, 70–74, 75–79, 80–84, and 85-plus), Zim contains market level characteristics (the premium and non-premium OOPC measures described above, and three plan count terms: the number of plans, the number of plans above 15, and the number of plans above 44), and θt is a set of year fixed effects.8 Our key estimates of interest are the coefficients on the age group indicators.

We estimate a series of additional regression models to assess the sensitivity of our results. First, to assess whether the influence of the number of plan options on enrollment choice differs between new and incumbent beneficiaries we run our main regression model separately on 65-year-olds and those aged 66-plus. Second, to control for health status we include a series of 70 clinical condition indicators, coded using ICD-9 diagnosis codes from the inpatient hospital, outpatient hospital and physician supplier claims categories, in regressions using the age-66-plus sample for whom we have Medicare claims (20%). Third, to control for time-invariant characteristics of each MA market, we add county fixed effects to our main specification. (Due to computational limitations, we estimate this model on a 55% random sample of all beneficiaries in our main dataset.) Fourth, to better isolate any impact of status quo bias, we compare the plan choices of new beneficiaries (i.e., those aged 65), and those who are “nearly” new (i.e., those aged 67). Fifth, we add county fixed effects to this smaller sample. We cluster standard errors at the county level in all models.

Using our OOPC measure, we also perform calculations to quantify a lower bound for the “money left on the table” by enrollees who choose TM when that option is dominated in floor counties. We multiply the number of enrollees in TM by the difference in the expected OOPC (premium plus non-premium) between TM and MA, separately for each age group, county, and year. We then divide this amount by the number of Medicare beneficiaries, and summarize this estimate across age groups, counties, and in total for our sample.

4. Results

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics comparing the generosity of MA payment in rural floor, urban floor and non-floor counties in 2010, the latest year included in our analysis. The rural and urban floor benchmark payment rates of $740.16 and $818.04, respectively, are both less than the average payment rate in non-floor counties, $895.63. The table also shows that the risk-standardized, average cost rate for TM is lower in the floor counties. This translates into average payment generosity (the benchmark rate minus the TM cost rate) amounts of $86.76 and $138.09 in rural and urban floor counties, respectively. While the MA OOPC rate is higher in both types of floor counties than in non-floor counties, the opposite is the case for the TM OOPC rate. The average MA rebate (the portion of the difference between the benchmark and the plan bid that CMS directs insurers to spend on additional benefits for enrollees) is also smaller in floor counties. There are small differences in average risk scores across the groups of counties: for both MA and TM, enrollees in rural floor counties are the healthiest, enrollees in non-floor counties the least healthy. MA enrollees are healthier on average than TM enrollees.

Table 1.

Characteristics of rural floor, urban floor, and non-floor counties, 2010.

| Rural floor counties | Urban floor counties | Non-floor counties | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benchmark payment rate | 740.16 | 818.04 | 895.63 |

| TM average cost | 653.4 | 679.95 | 770.14 |

| Benchmark-TM cost | 86.76 | 138.09 | 125.49 |

| TM OOPC | 454.14 | 460.72 | 473.98 |

| MA OOPC | 323.5 | 326.92 | 307.6 |

| TM OOPC – MA OOPC | 130.65 | 133.79 | 166.38 |

| MA Rebate | 36.44 | 56.91 | 72.2 |

| Risk score, TM | 0.95 | 0.98 | 1.03 |

| Risk score, MA | 0.86 | 0.92 | 0.96 |

| Number of counties | 1,366 | 611 | 1,133 |

| Number of beneficiaries | 4,391,792 | 9,060,876 | 9,679,554 |

The “money left on the table” by the many TM beneficiaries in floor counties is significant, but varies across counties. As described in the previous section, for this calculation we multiply the difference between the TM and MA OOPC by the number of TM enrollees in the county, and then divide that amount by the number of Medicare beneficiaries in the county. Across counties, there is only moderate variation in the money foregone: $11 per month for the 25th percentile county, $27 for the 75th percentile county, and $19 for the median. Summarizing across counties by age group shows a small increase with age: $11 per month for non-incumbent beneficiaries, compared with $22 month for those aged 80–84. (Those 85 or older experience a loss of $16, perhaps because MA OOPC is higher for these older and sicker beneficiaries.)

Tables 2 and 3 compare TM and MA premiums and OOPC levels.9 Table 2 presents detailed descriptive statistics on six different measures of out of pocket cost: premium, facility-based spending, physician spending, dental spending, other spending and total non-premium OOPC. We performed these calculations on the 338 MA PFFS plans offered in 2007, weighting by the number of enrollees in each plan. On average, premiums for MA plans are $6 higher than the TM Part B premium of $94 per month. However, for most plans the premium difference is modest; average premium is equal or lower than the Part B premium for half the plans and MA PFFS plans at the 75th percentile have a premium of $103. In addition, virtually all MA enrollees had lower non-premium costs than enrollees in TM. And among those whose non-premium costs are greater (at the 99th percentile), the non-premium OOPC in MA plans was only $3 more ($135 per month, compared with average non-premium OOPC of $132 per month for enrollees in TM).10

Table 2.

Out-of-pocket cost estimates by spending category for MA PFFS plans offered in 2007.

| Spending category | Mean, TM | Mean, MA PFFS | 1st percentile | 25th percentile | 50th percentile | 75th percentile | 99th percentile |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Premium | 94 | 101 | 0 | 94 | 94 | 103 | 193 |

| Non-premium, total | 132 | 94 | 32 | 77 | 101 | 111 | 135 |

| Facility | 58 | 33 | 5 | 26 | 36 | 36 | 70 |

| Physician | 24 | 15 | 0 | 13 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| Other spending | 20 | 17 | 1 | 9 | 17 | 25 | 25 |

| Dental | 31 | 29 | 18 | 31 | 31 | 31 | 31 |

Note: This table presents enrollment-weighted descriptive statistics on the non-premium out-of-pocket cost for the 338 MA PFFS plans that were offered in 2007, separated by age group and health status group. The first column of the table presents the OOPC estimate for TM enrollees. The estimates indicate that the premium was higher for a significant fraction of MA PFFS plans, while total non-premium OOPC was lower for virtually all plans.

Table 3.

Percentage of beneficiaries whose 2007 county MA PFFS OOPC level exceed TM OOPC, by age group and health status.

| Age group and health status | Premium (%) | Non-premium (%) | Facility (%) | Physician (%) | Other (%) | Dental (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ages 65–69 | ||||||

| Excellent | 76 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 38 | 0 |

| Very good | 76 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 31 | 0 |

| Good | 76 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 0 |

| Fair | 76 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 17 | 0 |

| Poor | 76 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0 |

| Ages 70–74 | ||||||

| Excellent | 76 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 32 | 0 |

| Very good | 76 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 27 | 0 |

| Good | 76 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 0 |

| Fair | 76 | 4 | 11 | 0 | 19 | 0 |

| Poor | 76 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 18 | 0 |

| Ages 75–79 | ||||||

| Excellent | 76 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 29 | 0 |

| Very good | 76 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 33 | 0 |

| Good | 76 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 27 | 0 |

| Fair | 76 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 22 | 0 |

| Poor | 76 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 23 | 0 |

| Ages 80–84 | ||||||

| Excellent | 76 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 39 | 0 |

| Very good | 76 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 30 | 0 |

| Good | 76 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 24 | 0 |

| Fair | 76 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 25 | 0 |

| Poor | 76 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 8 | 0 |

| Ages 85-plus | ||||||

| Excellent | 76 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 38 | 0 |

| Very good | 76 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 32 | 0 |

| Good | 76 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 33 | 0 |

| Fair | 76 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 29 | 0 |

| Poor | 76 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 19 | 0 |

Note: Each cell of the table describes the beneficiary-weighted percentage of our sample of TM beneficiaries whose MA PFFS OOPC exceed the TM OOPC. The MA PFFS in each county is calculated as an enrollment-weighted average of the values for the PFFS plans operating in the county. For virtually all spending types, the MA OOPC was lower. The two broad exceptions are the MA premium (on average $25 higher than the TM level of $94, conditional on the MA PFFS premium being greater) and other spending (on average $3 higher than the TM level, conditional on the MA PFFS spending being greater).

Table 3 describes the premium and OOPC amounts faced by the 2007 beneficiaries in our sample. Separately for each age group and health status group, we report the percentage of enrollees who faced a higher average OOPC from the MA PFFS plans operating in their county when compared with TM. Once again, two results stand out. First, three-quarters of enrollees faced a higher premium in MA. Further analysis find that conditional on the MA premium in the county being greater than the TM level of $94, the additional cost was $25 per month. Second, with one exception, virtually none of the beneficiaries in our sample faced a non-premium OOPC that was higher in MA than in TM. The exception is the “other” spending category. While between 8 and 39% of enrollees faced a higher average OOPC level for “other” spending, the difference in dollar terms was small (on average, $3 higher than the TM level, conditional on the MA level being higher).

Tables 4 and 5 present results from our multinomial logit regressions. Table 4 presents the results from the models on the full sample. The coefficient estimates for the age group indicators are all negative and statistically significant (P < 0.01), suggesting that status quo bias plays an important role in beneficiary decisions to enroll in MA. This is true for both pairwise comparisons (HMO/PPO and PFFS, with TM as the reference category). The results are substantively significant as well: holding all variables constant at their means (except for plan count, which we set to 30), 65-year-old beneficiaries join MA at a rate of 12 percent (7% for HMO/PPO plans and 5% for PFFS plans, respectively), while those 66 and older join at a rate of 3% (1% for HMO/PPO and 2% for PFFS, respectively). Table 5 presents results from a model including only 65 and 67 year olds and we see a similar pattern: 67-year-old beneficiaries are less likely to join MA. The coefficient estimates translate to predicted MA enrollment probabilities of 12 and 4% for 65- and 67-year-olds, respectively.

Table 4.

Regression results, ages 65-plus.

| Ages 65-plus | Age 65 | Ages 66-plus | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HMO | PFFS | HMO | PFFS | HMO | PFFS | |

| Age 66–69 | −1.397*** | −0.920*** | ||||

| 0.0222 | 0.0111 | |||||

| Age 70–74 | −1.719*** | −1.010*** | −0.305*** | −0.0874*** | ||

| 0.0406 | 0.0198 | 0.0229 | 0.0124 | |||

| Age 75–79 | −1.975*** | −1.109*** | −0.557*** | −0.187*** | ||

| 0.0458 | 0.0247 | 0.0283 | 0.0173 | |||

| Age 80–84 | −2.188*** | −1.261*** | −0.749*** | −0.334*** | ||

| 0.0549 | 0.0389 | 0.0401 | 0.0326 | |||

| Age 85-plus | −2.457*** | −1.456*** | −1.033*** | −0.528*** | ||

| 0.0429 | 0.0367 | 0.0272 | 0.0292 | |||

| Plan count | 0.259*** | 0.106*** | 0.275*** | 0.0835*** | 0.257**** | 0.110*** |

| 0.0477 | 0.0194 | 0.0527 | 0.0187 | 0.053 | 0.0199 | |

| Plan count above 16 | −0.211*** | −0.112*** | −0.221*** | −0.0858*** | −0.212*** | −0.116*** |

| 0.0479 | 0.0198 | 0.0522 | 0.019 | 0.0533 | 0.0203 | |

| Plan count above 45 | −0.0309*** | 0.0185*** | −0.0333*** | −0.0073 | −0.0309*** | 0.0232*** |

| 0.00395 | 0.00523 | 0.00436 | 0.00545 | 0.00433 | 0.0054 | |

| Premium | 0.00376** | −0.00738*** | 0.000545 | −0.0118*** | 0.00480*** | −0.00651*** |

| 0.00147 | 0.00125 | 0.00139 | 0.0014 | 0.00165 | 0.00125 | |

| Non-premium OOPC | 0.00272 | −0.00733** | −0.00846** | −0.0120*** | 0.00623** | −0.00667** |

| 0.00285 | 0.00287 | 0.00342 | 0.00312 | 0.00302 | 0.00287 | |

| Year 2008 | −0.870*** | −0.229*** | −0.885*** | 0.0893 | −0.871*** | −0.282*** |

| 0.0616 | 0.0736 | 0.0726 | 0.0676 | 0.0624 | 0.0763 | |

| Year 2009 | −0.609*** | −0.440*** | −0.359*** | 0.401*** | −0.682*** | −0.614*** |

| 0.0514 | 0.0554 | 0.0646 | 0.0547 | 0.0543 | 0.0581 | |

| Year 2010 | 0.195*** | −1.130*** | 0.471*** | −0.038 | 0.118** | −1.398*** |

| 0.0518 | 0.049 | 0.0706 | 0.0476 | 0.0552 | 0.0519 | |

| Black | 0.0617 | 0.519*** | −0.330*** | 0.127*** | 0.202*** | 0.592*** |

| 0.0455 | 0.0344 | 0.0506 | 0.0397 | 0.0464 | 0.0341 | |

| Male | −0.0686*** | −0.0564*** | −0.275*** | −0.238*** | 0.0138** | −0.0199*** |

| 0.00609 | 0.00597 | 0.00752 | 0.00602 | 0.00653 | 0.00694 | |

| Constant | −6.664*** | −4.059*** | −7.429*** | −4.181*** | −7.884*** | −4.976*** |

| 0.7 | 0.293 | 0.767 | 0.281 | 0.78 | 0.299 | |

| Observations | 53,929,660 | 4,266,963 | 49,662,697 | |||

Note: This table presents results from three multinomial logit regressions. All three regressions model the choice between traditional Medicare (TM, the omitted category), Medicare Advantage (MA) HMO/PPO plans, and MA private fee-for-service (PFFS) plans. The first regression was run on the full sample of beneficiaries aged 65 and above. The second model was run on beneficiaries aged 65 only. The third model was run on beneficiaries aged 66 and above. Standard errors are clustered at the county level.

p < 0.1.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

Table 5.

Regression results, ages 65 and 67.

| Ages 65 and 67 | ||

|---|---|---|

| HMO | PFFS | |

| Age 67 | −1.425*** | −0.940*** |

| 0.0238 | 0.0106 | |

| Plan count | 0.268*** | 0.0881*** |

| 0.0484 | 0.0186 | |

| Plan count above 16 | −0.215*** | −0.0917*** |

| 0.0481 | 0.0189 | |

| Plan count above 45 | −0.0322*** | −0.00121 |

| 0.00411 | 0.00528 | |

| Premium | 0.00138 | −0.0107*** |

| 0.00133 | 0.00137 | |

| Non-premium OOPC | −0.00625* | −0.0103*** |

| 0.00321 | 0.00306 | |

| Year 2008 | −0.884*** | −0.0389 |

| 0.0682 | 0.0663 | |

| Year 2009 | −0.417*** | 0.150*** |

| 0.059 | 0.0539 | |

| Year 2010 | 0.402*** | −0.339*** |

| 0.0641 | 0.0469 | |

| Black | −0.233*** | 0.229*** |

| 0.0465 | 0.0375 | |

| Male | −0.223*** | −0.189*** |

| 0.00719 | 0.00562 | |

| Constant | −7.211*** | −4.064*** |

| 0.704 | 0.279 | |

| Observations | 7,484,436 | |

Note: This table presents results from a multinomial logit regression that models the choice between traditional Medicare (TM, the omitted category), Medicare Advantage (MA) HMO/PPO plans, and MA private fee-for-service (PFFS) plans. The sample is comprised of beneficiaries aged 65 and 67. Standard errors are clustered at the county level.

p < 0.1.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

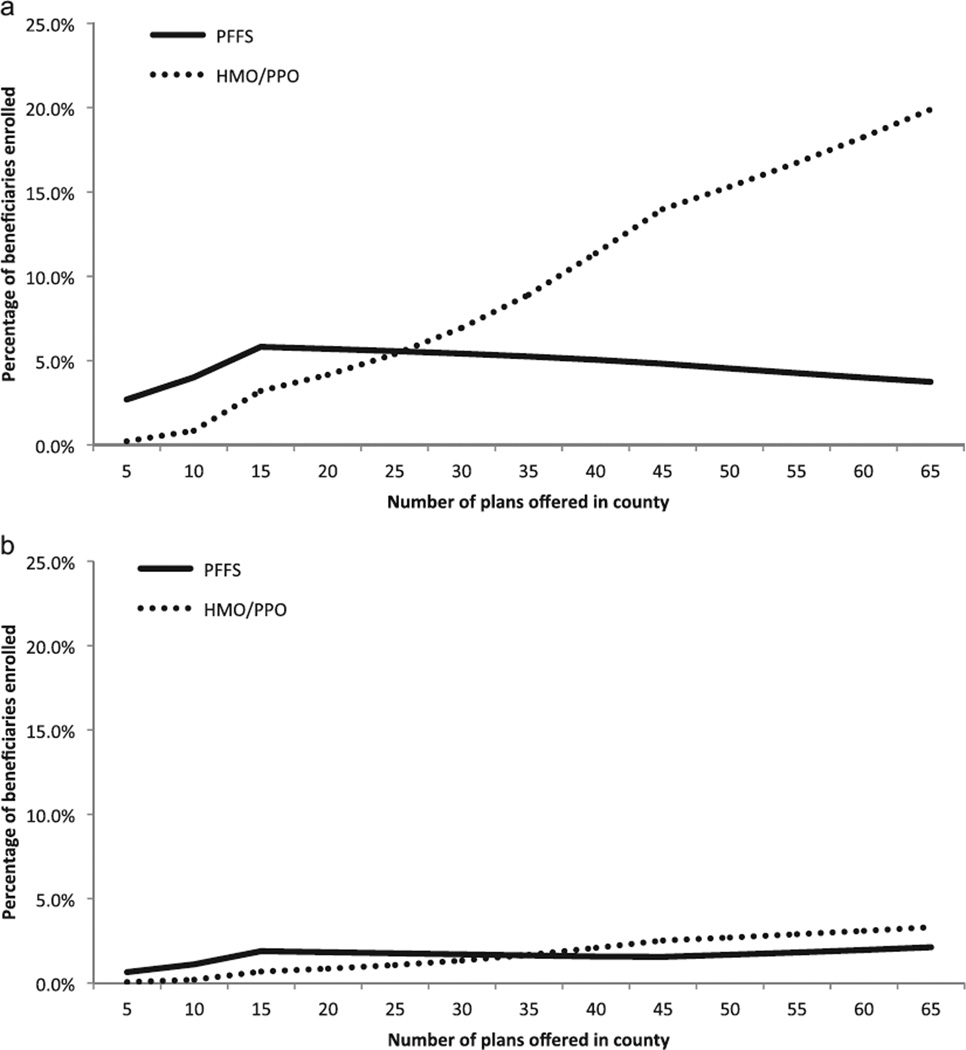

For the subsamples of 65-year-olds and those 66 and older, and for both pairwise comparisons, Table 4 shows that the coefficient estimates for each of the three plan count variables are statistically significant (P < 0.01). In Fig. 1a and b we illustrate how the regression-adjusted probability of each choice changes with the number of MA plans offered in the county for 65 year olds and for beneficiaries age 66-plus.11 While the probability of PFFS or HMO enrollment declines after the first cut point of 15 plans, there is no substantively significant decline in the probability of MA enrollment in response to a larger number of plan choices being offered.

Fig. 1.

(a) MA enrollment and plan choices, age 65 (regression adjusted). (b) MA enrollment and plan choices, ages 66-plus (regression adjusted). (a)Note: This figure depicts the predicted probability of enrollment in either MA PFFS or MA HMO/PPO plans, as a function of the number of plans offered in the county of residence. The predictions are generated using the coefficient estimates from a multinomial logit regression of enrollment choice on three spline terms describing the number of MA plans offered in the county, average premium, average non-premium OOPC, and indicators for male and black beneficiaries. The results indicate that enrollment in HMO/PPO plans increases with the number of plan options, while enrollment in PFFS plans declines slightly beyond 15 plans. (b) Note: This figure depicts the predicted probability of enrollment in either MA PFFS or MA HMO/PPO plans, as a function of the number of plans offered in the county of residence. The predictions are generated using the coefficient estimates from a multinomial logit regression of enrollment choice on age group indicators, three spline terms describing the number of MA plans offered in the county, average premium, average non-premium OOPC, and indicators for male and black beneficiaries. The results indicate that enrollment in HMO/PPO plans increases with the number of plan options, while enrollment in PFFS plans declines slightly beyond 15 plans.

The regression results offer two other important insights. First, among incumbent beneficiaries there is a monotonic and statistically significant decline in both HMO/PPO and PFFS enrollment as a beneficiary’s age increases. Second, enrollees are generally insensitive to premium and OOPC. For the full sample, an increase in the premium and OOPC terms (i.e., a reduction MA plan generosity) leads to higher HMO enrollment, which is contrary to what one would expect. For the PFFS choice, the coefficients for these terms are of the expected sign. But for both choices, the impact of each of these terms on the probability of selecting MA is quite small: a shift from the 25th percentile to the 75th percentile values for each term leads to a change of less than one-tenth of 1%. We observe similar results in models restricted to the sample of 65- and 67-year-olds, presented in Table 5. As we discussed in Section 3, the OOPC term contains significant measurement error, so these coefficient estimates may be biased toward zero.

Our sensitivity analyses do not alter the main results. Whether we add county fixed effects to a 5% random sample of beneficiaries 65 and older, health status terms to a 20% random sample of beneficiaries 66 and older, or county fixed effects to the full sample of 65- and 67-year-olds, we observe the same pattern in the analytic results: the probability of MA enrollment declines after age 65, and increases with the number of plan options.12

5. Discussion

The relatively low rates of MA enrollment among Medicare beneficiaries, even among those residing in floor counties where high payments to plans have led to generous benefits for enrollees, remains a puzzle. In this paper we analyzed a time period when PFFS plans were able to offer a combination of enhanced benefits and no restrictions on provider choice, yet less than a quarter of Medicare beneficiaries were enrolled in MA. However, we find that the rate of MA enrollment was significantly higher among new Medicare beneficiaries than among incumbents, suggesting that enrollees who chose TM before this period were unlikely to revisit their choice. This finding suggests that status quo bias plays an important role in the selection of TM over PFFS or other MA options, and that the choice environment in place when enrollees first enter the Medicare program is important. Because trends in MA penetration depend at least in part on inertia, when MA plans and benefits become less attractive to beneficiaries, a fall in aggregate MA penetration may take years to observe as it takes time for the ramifications of new entrants failing to take-up MA to be felt.

Our results indicate that beneficiaries’ anticipated out-of-pocket were not an important factor when choosing between TM and either PFFS or HMO/PPO plans. While this may reflect measurement error in our measure of relative plan generosity, it is consistent with other work on health insurance plan choice (Abaluck and Gruber, 2011; Heiss et al., 2010).

A potential concern with this analysis is that our results depend on the assumption that PFFS plans represent a better deal than TM. Despite the fact that PFFS plans offer lower OOPC on the vast majority of health spending and equivalent or lower premiums for half of plans, beneficiaries may prefer TM simply because of the complexity involved in comparing MA to TM. Beneficiaries may be overwhelmed by all of the dimensions along which MA plans differ from TM. Although we have attempted to mitigate the impact of this issue by focusing on PFFS plans, whose non-network provisions should be salient to beneficiaries, and note that MA versus TM comparisons are made easier due to the CMS “Medicare Options Compare” website presents the OOPC estimates for each MA plan (as well as TM), it is not at all clear what percentage of elderly Medicare beneficiaries use the web-based resources CMS offers when making their plan choice and beneficiaries may have a preference for TM.

Another concern with the characterization of PFFS as a better deal than TM is that beneficiaries enrolled in TM have the opportunity to gain first-dollar coverage by purchasing a Medigap policy, which is not an option for MA enrollees. Ideally, we would control for supplemental coverage among TM enrollees in our sample, but we do not have information on this coverage in the micro-level enrollment file we employ in our analyses. Some beneficiaries may prefer the certainty of a monthly Medigap premium (in combination with TM) to the uncertainty of out-of-pocket medical expenses. But many MA plans offer similar types of coverage to Medigap plans, even at the front end, and at little or no additional premium. Indeed, one can view the inflated payments to plans in the MA program as subsidies that partially flow through to beneficiaries, covering medical expenses that they would otherwise need to insure against by purchasing supplemental coverage. Thus the perception that TM offers more first-dollar coverage than MA is not always borne out in practice.

A related and more nuanced concern involves beneficiaries’ perceptions of MA plan and insurer stability compared to TM. Perhaps beneficiaries worry that MA plans may be canceled, which would disrupt their care and force them to transition plans again in the near future. While this is a concern consumers might justifiably have about life insurance or long-term care insurers (where premiums in the current period insure against risks that occur potentially far in the future), this is unlikely to be a serious issue for MA. The enrollment contract is only 1 year in length, and patients can move back to TM or can select an alternative MA contract with little cost to them.

It is not clear what drives the inertia we observe. One possibility is that a beneficiary’s initial entry into Medicare involves active participation in the plan enrollment process: these individuals have to fill out forms and perhaps make in-person trips to their local security office, and also contemplate the value of Medigap, stand-alone Part D, and MA plans. Though TM occupies a preferred or default position in Medicare enrollment materials, simply being made aware in such materials (or by an insurance agent) of MA plans may foster active decision-making. Conversely, incumbent beneficiaries must overcome switching costs to move from TM to MA, which include costs of reviewing provider networks for each plan and learning a new set of cost sharing rules. Incumbent beneficiaries who take no action are re-enrolled in TM. The decision to remain in TM is thus much more passive when compared with the decisions required of new entrants to the program.

Inertia in beneficiary plan choices has implications for the functioning of the MA program. For example, the network requirements that were a part of the MIPPA caused many PFFS plans to exit MA, upon which many enrollees in those plans would be “defaulted” back into TM if they failed to actively choose a new MA plan. If the inertia documented here is significant, beneficiaries would be likely to remain in TM following these plan exits. If however plan exits mimic the choice environment beneficiaries experience when turning 65, then their decision would be more of an active one, which our results suggest would lead to higher rates of enrollment in a new MA plan.

The evidence we have presented on inertia also has implications for the dynamics of MA plan offerings. MA insurers may respond to inertia in this market by reducing the benefit generosity of existing plans, and introduce new ones to entice non-incumbent Medicare beneficiaries in a manner similar to insurers offering stand-alone Part D plans, as documented by Ericson (2012). Future work should explore this question.

MA enrollment did not decline with an increase in the number of plans available. However, since enrollment levels off beyond a certain number of plans, reducing the number of plans offered in some markets would not adversely affect enrollment rates (especially among incumbent beneficiaries), and if properly structured could generate additional benefits for enrollees or taxpayers. In their review of the behavioral economics literature on health care choices, Liebman and Zeckhauser (2008) propose that a public mediator play such a role in limiting plan choice, although they recognize that there may be political constraints. In fact, CMS recently issued a proposed rule that would reduce the number of plans in both the Part D and MA programs (Centers for Medicare & Medicare Services, 2014a). However, as Abaluck and Gruber (2011) make clear, a random selection of plans is not sufficient to improve consumer welfare. What is necessary is for policymakers or regulators to restrict choice to plans among an efficient frontier. For example, if CMS selected a small number of plans on the basis of competitive plan bids, government payments could be reduced without adversely impacting beneficiary welfare.

Another reform idea would be to optimize the informational resources available to consumers. The Affordable Care Act explicitly provided a role for health insurance “Navigators” to help enrollees on the health insurance exchanges find coverage (Department of Health & Human Services, 2013). A similar program could help MA enrollees optimize their enrollment decisions, and in particular assist incumbent beneficiaries overcome inertia in plan choice. One idea would be to have program representatives engage beneficiaries on an annual basis to reconsider the tradeoffs between MA and TM. Doing so could improve the welfare of many beneficiaries who have foregone the enhanced benefits of MA.

Appendix A

Table A.1.

Out-of-pocket cost estimates, non-premium spending, for MA PFFS plans offered in 2007.

| Age group and health status | Mean, TM | Mean, MA PFFS | 1st percentile | 25th percentile | 50th percentile | 75th percentile | 99th percentile |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ages 65–69 | |||||||

| Excellent | 77 | 59 | 31 | 50 | 60 | 70 | 72 |

| Very good | 90 | 69 | 38 | 57 | 70 | 82 | 82 |

| Good | 103 | 74 | 29 | 58 | 74 | 91 | 91 |

| Fair | 195 | 119 | 32 | 91 | 133 | 133 | 202 |

| Poor | 281 | 181 | 29 | 157 | 210 | 220 | 369 |

| Ages 70–74 | |||||||

| Excellent | 81 | 62 | 34 | 52 | 64 | 73 | 74 |

| Very good | 103 | 77 | 36 | 62 | 77 | 91 | 94 |

| Good | 119 | 87 | 35 | 70 | 90 | 104 | 107 |

| Fair | 231 | 167 | 65 | 135 | 187 | 187 | 250 |

| Poor | 314 | 215 | 81 | 192 | 244 | 249 | 327 |

| Ages 75–79 | |||||||

| Excellent | 100 | 75 | 37 | 63 | 75 | 89 | 89 |

| Very good | 99 | 72 | 28 | 56 | 74 | 89 | 91 |

| Good | 135 | 95 | 33 | 76 | 98 | 116 | 127 |

| Fair | 174 | 112 | 23 | 91 | 126 | 137 | 183 |

| Poor | 245 | 167 | 29 | 137 | 187 | 198 | 307 |

| Ages 80–84 | |||||||

| Excellent | 104 | 75 | 36 | 61 | 77 | 89 | 91 |

| Very good | 107 | 78 | 27 | 61 | 82 | 94 | 107 |

| Good | 141 | 96 | 28 | 76 | 108 | 115 | 146 |

| Fair | 188 | 134 | 27 | 112 | 157 | 158 | 247 |

| Poor | 278 | 180 | 29 | 162 | 205 | 205 | 343 |

| Ages 85-plus | |||||||

| Excellent | 103 | 76 | 22 | 57 | 85 | 90 | 120 |

| Very good | 123 | 87 | 27 | 71 | 101 | 101 | 135 |

| Good | 129 | 86 | 19 | 69 | 97 | 102 | 136 |

| Fair | 161 | 116 | 15 | 97 | 132 | 140 | 205 |

| Poor | 265 | 206 | 93 | 197 | 216 | 222 | 323 |

Note: This table presents enrollment-weighted descriptive statistics on the non-premium out-of-pocket cost for the 338 MA PFFS plans that were offered in 2007, separated by age group and health status group. The first column of the table presents the OOPC estimate for TM enrollees. For every age-health status cell, the OOPC associated with the 75th percentile MA PFFS plan is lower than the TM OOPC. The estimates indicate that for those in fair or poor health, OOPC was higher under the least generous MA plans.

Table A.2.

Out-of-pocket cost estimates, facility spending, for MA PFFS plans offered in 2007.

| Age group and health status | Mean, TM | Mean, MA PFFS | 1st percentile | 25th percentile | 50th percentile | 75th percentile | 99th percentile |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ages 65–69 | |||||||

| Excellent | 13 | 8 | 1 | 5 | 10 | 10 | 15 |

| Very good | 20 | 11 | 3 | 9 | 14 | 14 | 19 |

| Good | 35 | 19 | 5 | 15 | 23 | 23 | 33 |

| Fair | 113 | 54 | 8 | 36 | 51 | 51 | 153 |

| Poor | 156 | 84 | 6 | 67 | 97 | 97 | 243 |

| Ages 70–74 | |||||||

| Excellent | 15 | 7 | 0 | 5 | 9 | 9 | 15 |

| Very good | 28 | 15 | 3 | 11 | 17 | 17 | 27 |

| Good | 43 | 25 | 8 | 20 | 28 | 28 | 43 |

| Fair | 140 | 96 | 41 | 74 | 97 | 97 | 195 |

| Poor | 214 | 135 | 61 | 116 | 145 | 145 | 230 |

| Ages 75–79 | |||||||

| Excellent | 23 | 11 | 1 | 9 | 14 | 14 | 22 |

| Very good | 28 | 14 | 1 | 10 | 17 | 17 | 31 |

| Good | 51 | 25 | 2 | 19 | 29 | 29 | 53 |

| Fair | 91 | 47 | 5 | 37 | 52 | 52 | 110 |

| Poor | 121 | 73 | 3 | 65 | 80 | 80 | 196 |

| Ages 80–84 | |||||||

| Excellent | 30 | 14 | 1 | 10 | 17 | 17 | 25 |

| Very good | 37 | 21 | 1 | 15 | 24 | 24 | 46 |

| Good | 63 | 33 | 2 | 25 | 37 | 37 | 79 |

| Fair | 102 | 64 | 2 | 51 | 70 | 70 | 167 |

| Poor | 165 | 94 | 4 | 83 | 99 | 99 | 235 |

| Ages 85-plus | |||||||

| Excellent | 51 | 35 | 4 | 24 | 39 | 39 | 76 |

| Very good | 54 | 31 | 1 | 24 | 33 | 35 | 75 |

| Good | 66 | 35 | 1 | 26 | 38 | 38 | 80 |

| Fair | 99 | 65 | 4 | 52 | 74 | 74 | 145 |

| Poor | 184 | 141 | 79 | 135 | 135 | 150 | 239 |

Note: This table presents enrollment-weighted descriptive statistics on facility out-of-pocket cost for the 338 MA PFFS plans that were offered in 2007, separated by age group and health status group. The first column of the table presents the OOPC estimate for TM enrollees. For every age-health status cell, the OOPC associated with the 75th percentile MA PFFS plan is lower than the TM OOPC. The estimates indicate that for those in fair or poor health, OOPC was higher under the least generous MA plans.

Table A.3.

Out-of-pocket cost estimates, physician spending, for MA PFFS plans offered in 2007.

| Age group and health status | Mean, TM | Mean, MA PFFS | 1st percentile | 25th percentile | 50th percentile | 75th percentile | 99th percentile |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ages 65–69 | |||||||

| Excellent | 17 | 8 | 0 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 12 |

| Very good | 17 | 9 | 0 | 8 | 11 | 11 | 12 |

| Good | 20 | 13 | 0 | 11 | 16 | 16 | 18 |

| Fair | 28 | 18 | 0 | 15 | 21 | 22 | 23 |

| Poor | 35 | 23 | 0 | 18 | 26 | 28 | 31 |

| Ages 70–74 | |||||||

| Excellent | 16 | 9 | 0 | 7 | 11 | 11 | 12 |

| Very good | 20 | 12 | 0 | 10 | 15 | 15 | 16 |

| Good | 24 | 15 | 0 | 13 | 18 | 19 | 21 |

| Fair | 33 | 20 | 0 | 16 | 24 | 25 | 26 |

| Poor | 31 | 21 | 0 | 17 | 24 | 26 | 27 |

| Ages 75–79 | |||||||

| Excellent | 20 | 12 | 0 | 10 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

| Very good | 22 | 14 | 0 | 12 | 17 | 17 | 19 |

| Good | 27 | 18 | 0 | 15 | 22 | 23 | 24 |

| Fair | 32 | 21 | 0 | 17 | 24 | 26 | 27 |

| Poor | 47 | 25 | 0 | 20 | 28 | 31 | 41 |

| Ages 80–84 | |||||||

| Excellent | 21 | 13 | 0 | 11 | 15 | 15 | 17 |

| Very good | 23 | 14 | 0 | 12 | 17 | 18 | 19 |

| Good | 28 | 18 | 0 | 14 | 21 | 22 | 23 |

| Fair | 31 | 20 | 0 | 17 | 24 | 25 | 26 |

| Poor | 37 | 22 | 0 | 18 | 25 | 27 | 29 |

| Ages [85-plus | |||||||

| Excellent | 21 | 12 | 0 | 10 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

| Very good | 24 | 14 | 0 | 12 | 17 | 18 | 19 |

| Good | 26 | 17 | 0 | 14 | 20 | 21 | 22 |

| Fair | 26 | 19 | 0 | 16 | 22 | 23 | 24 |

| Poor | 27 | 18 | 0 | 14 | 20 | 22 | 22 |

Note: This table presents enrollment-weighted descriptive statistics on physician out-of-pocket cost for the 338 MA PFFS plans that were offered in 2007, separated by age group and health status group. The first column of the table presents the OOPC estimate for TM enrollees. For every age-health status cell, the OOPC associated with the 99th percentile MA PFFS plan is lower than the TM OOPC.

Table A.4.

Out-of-pocket-cost estimates, other spending, for MA PFFS plans offered in 2007.

| Age Group and Health Status | Mean, TM | Mean, MA PFFS | 1st percentile | 25th percentile | 50th percentile | 75th percentile | 99th percentile |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ages 65–69 | |||||||

| Excellent | 9 | 8 | 1 | 4 | 7 | 12 | 14 |

| Very good | 10 | 9 | 1 | 4 | 9 | 14 | 15 |

| Good | 18 | 14 | 1 | 6 | 14 | 23 | 23 |

| Fair | 28 | 22 | 2 | 12 | 23 | 34 | 34 |

| Poor | 67 | 53 | 2 | 38 | 50 | 73 | 79 |

| Ages 70–74 | |||||||

| Excellent | 10 | 9 | 1 | 5 | 9 | 13 | 15 |

| Very good | 14 | 12 | 1 | 5 | 12 | 19 | 19 |

| Good | 22 | 17 | 2 | 9 | 18 | 27 | 27 |

| Fair | 34 | 28 | 1 | 17 | 28 | 40 | 40 |

| Poor | 51 | 41 | 1 | 27 | 40 | 60 | 60 |

| Ages 75–79 | |||||||

| Excellent | 12 | 10 | 1 | 5 | 10 | 16 | 17 |

| Very good | 14 | 12 | 2 | 5 | 12 | 20 | 20 |

| Good | 22 | 19 | 2 | 10 | 19 | 30 | 30 |

| Fair | 32 | 26 | 1 | 15 | 27 | 39 | 39 |

| Poor | 53 | 46 | 2 | 32 | 47 | 64 | 64 |

| Ages 80–84 | |||||||

| Excellent | 10 | 9 | 1 | 4 | 9 | 15 | 15 |

| Very good | 14 | 12 | 1 | 6 | 12 | 19 | 19 |

| Good | 21 | 18 | 1 | 9 | 18 | 28 | 28 |

| Fair | 29 | 25 | 1 | 15 | 26 | 36 | 36 |

| Poor | 51 | 41 | 1 | 29 | 42 | 55 | 61 |

| Ages 85-plus | |||||||

| Excellent | 10 | 9 | 1 | 4 | 8 | 15 | 16 |

| Very good | 15 | 13 | 1 | 7 | 14 | 20 | 21 |

| Good | 17 | 15 | 1 | 8 | 16 | 22 | 22 |

| Fair | 24 | 21 | 1 | 13 | 22 | 31 | 31 |

| Poor | 41 | 35 | 1 | 26 | 38 | 46 | 53 |

Note: This table presents enrollment-weighted descriptive statistics on other out-of-pocket cost for the 338 MA PFFS plans that were offered in 2007, separated by age group and health status group. The first column of the table presents the OOPC estimate for TM enrollees. For every age-health status cell, the OOPC associated with the 50th percentile MA PFFS plan is lower than the TM OOPC.

Table A.5.

Out-of-pocket-cost estimates, dental spending, for MA PFFS plans offered in 2007.

| Age group and health status | Mean, TM | Mean, MA PFFS | 1st percentile | 25th percentile | 50th percentile | 75th percentile | 99th percentile |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ages 65–69 | |||||||

| Excellent | 38 | 35 | 22 | 38 | 38 | 38 | 38 |

| Very good | 43 | 40 | 26 | 43 | 43 | 43 | 43 |

| Good | 29 | 27 | 16 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 |

| Fair | 26 | 25 | 17 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 |

| Poor | 22 | 21 | 15 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 |

| Ages 70–74 | |||||||

| Excellent | 40 | 37 | 24 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 |

| Very good | 41 | 38 | 25 | 41 | 41 | 41 | 41 |

| Good | 31 | 29 | 19 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 |

| Fair | 24 | 23 | 15 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 |

| Poor | 19 | 18 | 13 | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 |

| Ages 75–79 | |||||||

| Excellent | 45 | 42 | 26 | 45 | 45 | 45 | 45 |

| Very good | 35 | 32 | 19 | 35 | 35 | 35 | 35 |

| Good | 35 | 32 | 21 | 35 | 35 | 35 | 35 |

| Fair | 19 | 17 | 10 | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 |

| Poor | 24 | 22 | 16 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 |

| Ages 80–84 | |||||||

| Excellent | 42 | 40 | 25 | 42 | 42 | 42 | 42 |

| Very good | 33 | 31 | 19 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 |

| Good | 29 | 27 | 17 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 |

| Fair | 26 | 25 | 17 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 |

| Poor | 24 | 23 | 17 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 |

| Ages 85-plus | |||||||

| Excellent | 21 | 20 | 11 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 |

| Very good | 30 | 28 | 19 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 |

| Good | 20 | 19 | 12 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| Fair | 13 | 11 | 6 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 |

| Poor | 13 | 12 | 7 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 |

Note: This table presents enrollment-weighted descriptive statistics on dental out-of-pocket cost for the 338 MA PFFS plans that were offered in 2007, separated by age group and health status group. The first column of the table presents the OOPC estimate for TM enrollees. Only a small percentage of MA plans offered dental coverage, so for most plans the OOPC for dental care was the same as TM.

Table A.6.

Additional regression results.

| County fixed effects, ages 65-plus | Condition categories, ages 66-plus |

County fixed effects, ages 65 and 67 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HMO | PFFS | HMO | PFFS | HMO | PFFS | |

| Age 66–69 | −1.364*** | −0.939*** | ||||

| 0.023 | 0.0193 | |||||

| Age 70–74 | −1.688*** | −1.033*** | −0.243*** | −0.0415*** | ||

| 0.039 | 0.0241 | 0.0218 | 0.0133 | |||

| Age 75–79 | −1.934*** | −1.132*** | −0.432*** | −0.0991*** | ||

| 0.046 | 0.0313 | 0.0258 | 0.0168 | |||

| Age 80–84 | −2.150*** | −1.261*** | −0.569*** | −0.209*** | ||

| 0.0503 | 0.0414 | 0.0342 | 0.031 | |||

| Age 85-plus | −2.462*** | −1.469*** | −0.840*** | −0.394*** | ||

| 0.0442 | 0.0412 | 0.0232 | 0.027 | |||

| Age 67 | −1.395*** | −0.941*** | ||||

| 0.0225 | 0.0111 | |||||

| Plan count | 0.135*** | 0.0787** | 0.254*** | 0.106*** | 0.155*** | 0.0602*** |

| 0.0495 | 0.0309 | 0.0514 | 0.02 | 0.022 | 0.0158 | |

| Plan count above 16 | −0.146*** | −0.0586* | −0.208*** | −0.113*** | −0.157*** | −0.0498*** |

| 0.0494 | 0.0307 | 0.0518 | 0.0205 | 0.0221 | 0.0154 | |

| Plan count above 45 | 0.00205 | 0.0219*** | −0.0307*** | 0.0234*** | 0.0011 | 0.00771*** |

| 0.00426 | 0.00609 | 0.00436 | 0.00531 | 0.00224 | 0.00242 | |

| Premium | 0.000608 | −0.00975*** | 0.00518*** | −0.00638*** | −0.000596 | −0.0105*** |

| 0.00153 | 0.00136 | 0.00167 | 0.00125 | 0.00111 | 0.0009 | |

| Non-premium OOPC | 0.00496* | −0.00557** | 0.00652** | −0.00648** | 0.00292 | −0.0112*** |

| 0.00284 | 0.00283 | 0.00303 | 0.00289 | 0.0024 | 0.00182 | |

| Year 2008 | 0.207* | −0.713*** | −0.882*** | −0.287*** | 0.192*** | −0.413*** |

| 0.109 | 0.0954 | 0.0636 | 0.0763 | 0.0741 | 0.0511 | |

| Year 2009 | 0.311*** | −0.889*** | −0.699*** | −0.626*** | 0.400*** | −0.142*** |

| 0.0905 | 0.078 | 0.0558 | 0.0584 | 0.0607 | 0.0437 | |

| Year 2010 | 0.540*** | −1.249*** | 0.107* | −1.392*** | 0.691*** | −0.456*** |

| 0.0686 | 0.0703 | 0.0553 | 0.0528 | 0.048 | 0.0355 | |

| Black | 0.268*** | 0.604*** | 0.219*** | 0.577*** | 0.0217 | 0.426*** |

| 0.0445 | 0.0324 | 0.046 | 0.0352 | 0.0445 | 0.0251 | |

| Male | −0.0821*** | −0.0736*** | 0.0441*** | 0.00613 | −0.235*** | −0.205*** |

| 0.00969 | 0.0109 | 0.00826 | 0.00891 | 0.00722 | 0.00576 | |

| Constant | −3.676*** | −4.122*** | −7.740*** | −4.836*** | −4.009*** | −4.149*** |

| 0.737 | 0.459 | 0.756 | 0.301 | 0.322 | 0.235 | |

| Observations | 2,461,442 | 9,932,390 | 7,155,814 | |||

Note: This table presents results from three multinomial logit regressions. All three regressions model the choice between traditional Medicare (TM, the omitted category), Medicare Advantage (MA) HMO/PPO plans, and MA private fee-for-service (PFFS) plans. The first regression was run on a 5% sample of beneficiaries aged 65 and above, and included county-level fixed effects. The second model was run on a 20% sample beneficiaries aged 66 and above, and included condition category indicator variables. The third model was run on beneficiaries aged 65 and 67, and included county-level fixed effects. The coefficient estimates are suppressed for the county fixed effects and condition category terms. Standard errors are clustered at the county level.

p < 0.1.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

Footnotes

Insurers submit bids to CMS based on these payment rates. Most plans bid below the payment rates, and are legally required to share the “rebate” they receive from CMS (a portion of the difference between the benchmark and the bid) on benefits for enrollees.

Supplemental coverage is an issue here. Those who purchase a Medigap plan to gain such coverage enjoy reduced cost sharing, but this must be weighed against an additional premium. We return to this question in the discussion section.

Choice overload may also play an important role in the decision between MA and TM. While not the main focus of our paper, we do include measures of the number of plan choices as independent variables in our regression models. However, these measures of plan availability and generosity may be endogenous: MA insurers are more likely to enter markets where enrollees have a preference for MA.

Some counties’ benchmark payment rates were based on a 5-year average of the per capita spending on TM beneficiaries, measured at several different points in time. Other counties’ rates were set to a national minimum rate, and still others’ to either an urban or rural “floor” rate. The rate that prevailed in any county was the highest of all of these rates.

The Balanced Budget Act of 1997 (BBA) first introduced the idea of an MA floor rate, and the subsequent Budget Improvement and Protection Act of 2000 (BIPA) created separate floor rates for counties in urban and rural areas. Urban floor counties were defined as those that were part of metropolitan statistical areas with 250,000 or more residents.

We use the July file from each calendar year. Since CMS masks enrollment for any combination of plan and county with fewer than 11 enrollees, we assume that enrollment for those cases is zero.

One important difference is that the TM OOPC estimates do not vary across counties.

Due to the exclusions described above, the county-level plan count includes non-employer, non-SNP plans of three plan types: HMO, PPO (both local and “regional” variants), and PFFS.

We exclude spending on prescription drugs, as well as any premium paid for Medicare Part D drug plans (either stand-alone or paired with MA plans). If we assume that most TM enrollees procure drug coverage through Part D or some other source, then to be conservative we also assume that MA does not dominate on this dimension.

In an appendix, we include tables that present these statistics by age group and health status group, for each of the five non-premium OOPC measures.

We calculate the predicted probabilities in these by setting all variables (except the plan count terms) to their mean values.

The results from these sensitivity analyses are available in an appendix.

Contributor Information

Christopher C. Afendulis, Email: afendulis@hcp.med.harvard.edu.

Anna D. Sinaiko, Email: asinaiko@hsph.harvard.edu.

Richard G. Frank, Email: frank@hcp.med.harvard.edu.

References

- Abaluck J, Gruber J. Choice inconsistencies among the elderly: evidence from plan choice in the Medicare Part D Program. Am. Econ. Rev. 2011;101(4):1180–1210. doi: 10.1257/aer.101.4.1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abaluck J, Gruber J. Evolving choice inconsistencies in choice of prescription drug insurance; National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series No. 19163; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Biles B, Pozen JP, Guterman S. C. Fund. New York: The Commonwealth Fund; 2009. The Continuing Cost of Privatization: Extra Payments to Medicare Advantage Plans Jump to $11.4 Billion in 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bundorf MK, Levin J, Mahoney N. Pricing and welfare in health plan choice. Am. Econ. Rev. 2012;102(7):3214–3248. doi: 10.1257/aer.102.7.3214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare & Medicare Services. Monthly Contract and Enrollment Summary Report, July 2006. [accessed on 27.02.14];2006 Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/MCRAdvPartDEnrolData/Downloads/Contract-Summary-July-2006.pdf.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicare Services. 2007 CMS-HCC and Rx Model Software. [accessed on 27.02.14];2007a Available at: https://http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Health-Plans/MedicareAdvtgSpecRateStats/Downloads/Risk_Model_Software_2007.zip.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicare Services. FFS Data. [accessed on 27.02.14];2007 Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Health-Plans/MedicareAdvtgSpecRateStats/FFS_Data05a.html.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicare Services. Medicare Options Compare Database. 2007–2010 [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare & Medicare Services. Monthly Enrollment by Contract/Plan/State/County. [accessed 27.02.14];2007–2010 Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/MCRAdvPartDEnrolData/Monthly-Enrollment-by-Contract-Plan-State-County.html.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicare Services. Plan Payment Data. [accessed on 27.02.14];2007–2010 Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Advantage/Plan-Payment/Plan-Payment-Data.html.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicare Services. Ratebooks & Supporting Data. [accessed on 27.02.14];2007–2010 Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Health-Plans/MedicareAdvtgSpecRateStats/Ratebooks-and-Supporting-Data.html.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicare Services. FFS Data. [accessed on 27.02.14];2008–2010 Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Health-Plans/MedicareAdvtgSpecRateStats/FFS-Data.html.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicare Services. Fact Sheet: CMS Proposes Program Changes for Medicare Advantage and Prescription Drug Benefit Programs for Contract Year 2015 (CMS-4159-P) [accessed on 05.03.14];2014 Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Fact-sheets/2014-Fact-sheets-items/2014-01-06.html.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicare Services. Monthly Contract and Enrollment Summary Report, July 2014. [accessed on 07.05.15];2014 Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/MCRAdvPartDEnrolData/Downloads/2014/July/Monthly-Summary-Report-2014-07.zip.

- Department of Health & Human Services. Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act; Exchange Functions: Standards for Navigators and Non-Navigator Assistance Personnel; Consumer Assistance Tools and Programs of an Exchange and Certified Application Counsellors; Final Rule. 78 Federal Register137. [17 July 2013];2013 :42824–42862. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn A. The value of coverage in the medicare advantage insurance market. J. Health Econ. 2010;29(6):839–855. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ericson KMM. Consumer Inertia and Firm Pricing in the Medicare Part D Prescription Drug Insurance Exchange; National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series No. 18359; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Frank RG, Lamiraud K. Choice, price competition and complexity in markets for health insurance. J. Econ. Behav. Org. 2009;71(2):550–562. [Google Scholar]

- Handel BR. Adverse selection and inertia in health insurance markets: when nudging hurts. Am. Econ. Rev. 2013;103(7):2643–2682. doi: 10.1257/aer.103.7.2643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiss F, McFadden D, Winter J. Mind the gap! consumer perceptions and choices of Medicare Part D prescription drug plans. In: Wise DA, editor. Research Findings in The Economics of Aging. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2010. pp. 413–484. [Google Scholar]

- Ketcham JD, Lucarelli C, Miravete EJ, Roebuck MC. Sinking, swimming, or learning to swim in Medicare Part D. Am. Econ. Rev. 2012;102(6):2639–2673. doi: 10.1257/aer.102.6.2639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebman J, Zeckhauser R. Simple Humans, Complex Insurance, Subtle Subsidies; National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series No. 14330; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- McGuire TG, Newhouse JP, Sinaiko AD. An economic history of Medicare Part C. Milbank Quart. 2011;89(2):289–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2011.00629.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McWilliams JM, Afendulis CC, McGuire TG, Landon BE. Complex Medicare advantage choices may overwhelm seniors—especially those with impaired decision making. Health Affairs. 2011;30(9):1786–1794. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley G, Zarabozo C. Trends in the health status of Medicare risk contract enrollees. Health Care Financ. Rev. 2006;28(2):81–95. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royalty AB, Solomon N. Health plan choice: price elasticities in a managed competition setting. J. Hum. Resour. 1999;34(1):1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Salop SC. Monopolistic competition with outside goods. Bell J. Econ. 1979;10(1):141–156. [Google Scholar]

- Samuelson W, Zeckhauser R. Status quo bias in decision making. J. Risk Uncertain. 1988;1(1):7–59. [Google Scholar]

- Sinaiko AD, Afendulis CC, Frank RG. Enrollment in Medicare advantage plans in Miami-Dade county: evidence of status quo bias? INQUIRY: J. Health Care Org. Provis. Financ. 2013;50(3):202–215. doi: 10.1177/0046958013516586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinaiko AD, Hirth RA. Consumers, health insurance and dominated choices. J. Health Econ. 2011;30(2):450–457. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strombom BA, Buchmueller TC, Feldstein PJ. Switching costs, price sensitivity and health plan choice. J. Health Econ. 2002;21(1):89–116. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(01)00124-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]