Abstract

Background: To investigate the association between resting heart rate and the risk of developing impaired fasting glucose (IFG), diabetes and conversion from IFG to diabetes.

Methods: The prospective analysis included 73 357 participants of the Kailuan cohort (57 719 men and 15 638 women). Resting heart rate was measured via electrocardiogram in 2006. Incident diabetes was defined as either the fasting blood glucose (FBG) ≥ 7.0 mmol/l or new active use of diabetes medications during the 4-year follow-up period. IFG was defined as a FBG between 5.6 and 6.9 mmol/l. A meta-analysis including seven published prospective studies focused on heart rate and diabetes risk, and our current study was then conducted using random-effects models.

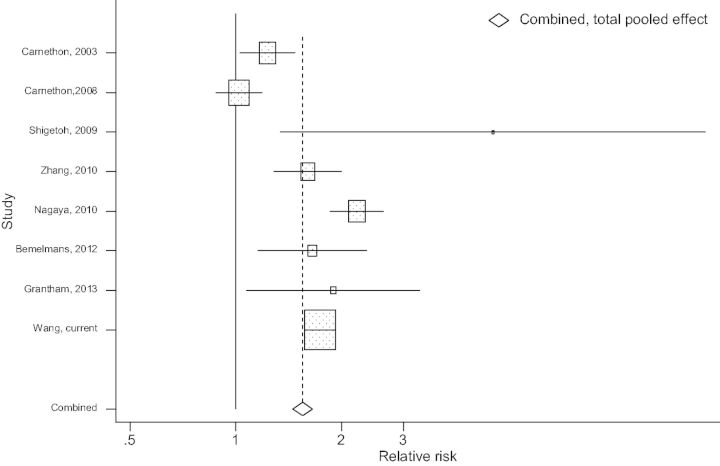

Results: During 4 years of follow-up, 17 463 incident IFG cases and 4 649 incident diabetes cases were identified. The corresponding adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) for each 10 beats/min increase in heart rate were 1.23 [95% confidence interval (CI): 1.19, 1.27] for incident diabetes, 1.11 (95% CI: 1.09, 1.13) for incident IFG and 1.13 (95% CI: 1.08, 1.17) for IFG to diabetes conversion. The risks of incident IFG and diabetes were significantly higher among participants aged < 50 years than those aged ≥ 50 years (P-interaction < 0.02 for both). A meta-analysis confirmed the positive association between resting heart rate and diabetes risk (pooled HR for the highest vs lowest heart rate quintile = 1.59, 95% CI:1.27, 2.00; n = 8).

Conclusion: Faster resting heart rate is associated with higher risk of developing IFG and diabetes, suggesting that heart rate could be used to identify individuals with a higher future risk of diabetes.

Keywords: Heart rate, diabetes, prospective study

Key Messages.

Diabetes mellitus is a worldwide epidemic; approximately 12% Chinese adults have diabetes and 50% have prediabetes.

We observed that faster heart rate was significantly associated with increased risk of developing diabetes and impaired fasting glucose, and with conversion from impaired fasting glucose to diabetes among 73 357 Chinese adults without diabetes at the baseline.

A meta-analysis, based on seven previously published prospective studies and the current study, confirmed the positive association between resting heart rate and diabetes risk, suggesting that heart rate could be used to identify individuals with a higher future risk of diabetes.

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is a worldwide epidemic with an estimated prevalence projected to approach 366 million cases worldwide by 2030.1 In the USA, approximately 18.8 million US people were diagnosed with diabetes mellitus and another 7.0 million had undiagnosed diabetes in 2010.2 In China, diabetes mellitus has also been becoming one of the greatest public health burdens. A national survey in 2007–08 showed that there were 92.4 million adults with diabetes (50.2 million men and 42.2 million women) and 148.2 million adults with prediabetes, defined as impaired fasting glucose (IFG) and/or impaired glucose tolerance (IGT).3 A recent study showed that the prevalence of diabetes was 11.6% and of pre-diabetes (based on FG, IGT or HbA1c concentrations) was 50.1%, respectively in the Chinese adult population in 2010.4 Thus identification of risk factors for the development of diabetes and prediabetes is urgently needed, to better understand and prevent this public health epidemic in China. 5

In a previous cross-sectional study based on a national representative sample in China,3 several factors, including fast heart rate, have been identified to be associated with an increased likelihood of having diabetes. Heart rate is a crude index of the autonomic nervous system tone, reflecting a balance of sympathetic and parasympathetic inputs, and correlates with muscle sympathetic nerve activity and noradrenaline serum levels.6 Examining its potential role in diabetes risk could improve our understanding of the pathogenesis of diabetes. However, previous studies generated mixed results.7–9 Most previous studies have been conducted in developed countries such as the USA,9–11 Japan,8,12 Australia7 and the Netherlands.13 In the only prospective study conducted in China in which only female participants were included, a positive relationship between resting heart rate and type 2 diabetes was observed.14 However, the ascertainment of diabetes in that study was based on self-report and was more likely to be subject to some misclassification. In China, diabetes is generally under-diagnosed—only ∼30% of individuals with diabetes have been diagnosed.3,4

Another important knowledge gap is whether faster heart rate can predict risk of developing IFG, and conversion from IFG to diabetes. IFG is an intermediate stage between normal glucose tolerance and diabetes. IFG is associated with increased risk of developing diabetes and cardiovascular events.15 Studying potential risk factors for IFG is particularly significant for the Chinese population, as it has been estimated that more than 50% of Chinese adults may have prediabetes and 27% may have IFG.4 However, the relationship between heart rate and prediabetes or IFG has been investigated in very limited cross-sectional studies.16–18

In the context of these public health issues, we aimed to investigate the association between resting heart rate, determined by electrocardiogram, and the risks of developing IFG among participants with normal glucose levels, and of developing diabetes among individuals with normal glucose levels or IFG, in a large prospective study of Chinese adults who were followed carefully with biannual examinations over 4 years (the largest longitudinal study investigating this question to date). We then combined our results with those of previously published prospective studies in a meta-analysis.

Methods

Study population

We used data from the Kailuan prospective study, which is a prospective cohort study based on the Kailuan community in Tangshan city in northern China, that represented the Chinese population from a socioeconomic perspective. Details of the study can be seen elsewhere.19,20

Briefly, in 2006–07 (i.e. the baseline of current study), a total of 101 510 participants (81 110 men and 20 400 women) completed questionnaires by interviews, and had clinical examinations that were conducted in the 11 hospitals responsible for healthcare of this community. These participants were then followed through 2010 with repeated questionnaires and clinical and laboratory examinations every 2 years. In the current study, participants were excluded if they had missing information on heart rate in the baseline examination (n = 4743), if they had known diabetes at baseline (n = 9486), physician-diagnosed cancer or cardiovascular disease at the baseline or during follow-up (n = 1309) or if they did not participate in the subsequent 2008 or 2010 survey (n = 12 615). Following these exclusions, a total of 73 357 were included in the current analyses of diabetes risk. To examine the relationship between heart rate and IFG, we further excluded 17 269 participants who had IFG at baseline (2006), leaving 56 088 participants for the incident IFG analyses. The association between heart rate and risk of converting from IFG to diabetes was investigated among 17 269 participants with IFG at the baseline (eFigure 1, available as Supplementary data at IJE online).

The protocol for this study was in accordance with the guidelines of the Helsinki Declaration, and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Kailuan Medical Group, Kailuan Company, and Brigham and Women’s hospital, Boston MA. All the participants gave their written informed consent.

Assessment of resting heart rate

Heart rate was measured in the baseline examination in 2006–07. After a 5-min or longer rest, heart rate was recorded based on the results of a 12-lead electrocardiogram performed with participants in the supine position. The inverse of the interval between R-waves for five consecutive QRS complexes was used to determine heart rate. Ectopic beats were excluded and only normal heart beats were taken into account. In the current study, participants were classified into five categories according to quintile cut-points of resting heart rate, and the first quintile was used as the reference group.

Assessment of potential covariates

Demographic data (age, sex) and smoking status, alcohol drinking status, education, occupation, physical activity and family history of diabetes and cardiovascular disease were obtained from questionnaires at baseline in 2006. Physical activity was evaluated from responses to questions regarding the frequency of physical activity (of 20+ min) during leisure time, with the possible responses including: never, 1–3 times per week, and ≥ 4 times per week. Menopausal status in women was recorded in 2010.

Anthropometric parameters and blood pressure were measured during the interview. Height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm using a tape rule, and weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg using calibrated platform scales. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in metres squared. Waist circumference (WC) was measured in centimetres.

Blood pressure (BP) was measured on the left arm to the nearest 2 mmHg using a mercury sphygmomanometer with a cuff of appropriate size, following the standard recommended procedures. Two readings each of systolic BP and diastolic BP were taken at a 5-min intervals after participants had rested in a chair for at least 5 min. The average of the two readings was used for data analysis. If a difference of more than 5 mmHg was observed between the two measurements, then a third reading was taken. Finally, the average of the three readings was used for data analysis. In the current study, hypertension was defined as systolic BP ≥ 140 mmHg or diastolic BP ≥ 90 mmHg or use of antihypertensive medications in past 2 weeks irrespective of BP.

Blood samples, after an overnight fast, were repeatedly collected at the baseline and in the 2008 and 2010 surveys. Fasting blood glucose (FBG) was measured with the hexokinase/glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase method. The coefficient of variation using blind quality control specimens was < 2.0%. Triglyceride (TG) was measured enzymatically (interassay coefficient of variation < 10%; Mind Bioengineering, Shanghai, China). C-reactive protein (CRP) was measured by high-sensitivity nephelometry assay (Cias Latex CRP-H, Kanto Chemical, Tokyo, Japan). All blood samples were tested using an auto-analyser (Hitachi 747; Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) at the central laboratory of the Kailuan General Hospital. Hyperlipidaemia was defined by the presence of any of the following: a history of hyperlipidaemia, current use of cholesterol-lowering agents or total cholesterol level ≥ 5.17 mmol/l or triglycerides ≥ 1.7 mmol/l.

Incident IFG and diabetes

In line with the American Diabetes Association guidelines, participants were identified as having diabetes mellitus if they were currently treated with insulin or oral hypoglycaemic agents, or had a fasting blood glucose (FBG) concentration ≥ 7.0 mmol/l in the 2008 and 2010 surveys.21 IFG was defined as a FBG concentration between 5.6 and 6.9 mmol/l.

Statistical analyses

Participants were divided into five categories based on resting heart rate quintiles. Person-years were calculated from the date of the 2006 interview was conducted to the date when either IFG or diabetes was detected (depending on the analysis in question), date of death or date of participating in the last interview in this analysis, whichever came first. For the analysis of IFG, we censored participants with diabetes onset during follow-up at diagnosis of the disease. In contrast, we did not exclude the participants with IFG at the baseline and onset during follow-up for the analysis of diabetes.

Cox proportional hazards regression was used to estimate the risk of diabetes by calculating the hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). To account for the potential confounding effect due to 11 participating hospitals, we used the Cox proportional hazards model with a sandwich covariance matrix as a random effect. Tests for linear trend in risk across heart rate quintiles were performed using the median value for each heart rate quintile and computing these five indices as continuous variables. We fitted three multivariate proportional hazards models, confirmation of the proportional hazards assumption being satisfied. Model 1 adjusted for age and sex. Model 2 further adjusted for BMI (since BMI is the strongest risk factor of diabetes and shows a dose-dependent risk).12,22 Model 3 further adjusted for smoking, alcohol drinking, education, physical activity, presence of hypertension and hyperlipidaemia, CRP, menopausal status(women only) and family history of diabetes and cardiovascular disease. We also conducted several sensitivity analyses to test the robustness of our findings. The blood pressure was also used instead of hypertension in the adjusted models. Because hypertension or use of antihypertensives (e.g. β-blockers) could impact on heart rate and future diabetes risk,23,24 we repeated our aforementioned analysis by excluding individuals with hypertension. Because approximately one-third of the participants were coal miners, who had different lifestyles and working environments than the rest of the participants, we conducted another sensitivity analysis by excluding the coal miners.

Based on the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA), a meta-analysis was also conducted combining the results of current study and those of previous studies on heart rate and the risk of developing diabetes. We searched relevant studies in Medline, PubMed, CINAHL and Cochrane library databases for articles published from 1960 through 31 December 2013, using the following terms: ‘heart rate’ and ‘type 2 diabetes, diabetes mellitus, impaired fasting glucose, prediabetes, or impaired glucose tolerance’. To be included in the meta-analysis, a study had to: (i) show available data on incidence of diabetes (referred to as a prospective study); (ii) examine the association between resting heart rate and the risk of developing diabetes; and (iii) be published in English. In addition, we manually searched the reference lists of relevant publications to identify more studies. In total, eight studies satisfied the criterias.7–14

We further excluded a study11 from the meta-analysis because, unlike the other seven studies, heart rate was treated as a continuous variable in this study, not in discrete categories. Thus, seven studies were included in the current meta-analysis, shown in eTable 1; eFigure 2 depicts the flow of study selection process (both available as Supplementary data at IJE online). Two authors independently extracted the data and, if they had disagreements, discussed with a third author. We extracted information about the authors, population and country where the study was conducted, sample size by sex and range of age, follow-up duration, covariates, outcome (diabetes) and the effect size [adjusted odds ratio (OR) or hazard ratio (HR)]. Cochran Q was used for examining heterogeneity among the studies.25 Because we observed a heterogeneity across studies, a random-effects model was used.26 The Begg and Egger tests were used to examine potential publication bias.27

The cohort analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), and the meta-analysis was performed using STATA software, version 9.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

Results

The mean age of participants was 50.3 ± 12.5 years for men and 47.2 ± 11.3 years for women at the baseline. The mean BMI was 25.1 ± 3.4 kg/m2 and blood glucose concentration was 5.1 ± 0.70 mmol/l in men, and 24.5 ± 3.7 kg/m2 and 4.9 ± 0.65 mmol/l, respectively, in women. Compared with participants with lower resting heart rate, those with faster resting heart rate were more likely to be current smokers, have hypertension, obesity and hyperlipidaemia, and have higher blood concentrations of TG and C-reactive protein (Table 1).

Table 1.

Age-standardized characteristics according to resting heart rate status in the Kailuan Study, China, 2006–07 (N = 73 357)

| Resting heart rate, median, b/m | Quintile of resting heart rate |

P-trend | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | ||

| (61) | (70) | (72) | (78) | (88a) | ||

| Men | ||||||

| n | 11 238 | 13 926 | 8608 | 14 542 | 9405 | |

| Age, years | 51.7(12.5) | 49.5(12.1) | 51.0(12.3) | 49.1(12.2) | 48.9(12.5) | <0.0001 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 24.8(3.2) | 25.2(3.3) | 25.2(3.4) | 25.2(3.4) | 25.0(3.5) | <0.0001 |

| Smoking status | ||||||

| Never, % | 51.4 | 52.0 | 48.1 | 49.0 | 47.5 | <0.0001 |

| Past, % | 7.5 | 6.3 | 7.0 | 6.0 | 6.2 | |

| Current, % | 41.1 | 41.7 | 44.9 | 45.0 | 46.3 | |

| Alcohol drinking status | ||||||

| Never, % | 47.9 | 50.8 | 47.4 | 49.0 | 47.8 | <0.0001 |

| Past, % | 4.2 | 4.0 | 4.5 | 3.7 | 3.9 | |

| Current, % | 47.9 | 45.2 | 48.1 | 47.3 | 48.3 | |

| Education | ||||||

| Illiteracy/Primary, % | 10.5 | 9.2 | 10.5 | 9.8 | 9.2 | <0.0001 |

| High school, % | 77.7 | 81.7 | 79.4 | 82.4 | 81.5 | |

| College or higher, % | 11.8 | 9.1 | 10.1 | 7.8 | 9.3 | |

| Exercise 2 x time/week, % | 17.1 | 15.3 | 18.9 | 15.5 | 11.8 | <0.0001 |

| Waist circumference, cm | 87.2(9.6) | 87.4(9.2) | 87.8(9.7) | 88.1(9.3) | 87.7(9.8) | <0.0001 |

| Hypertension, % | 34.3 | 41.5 | 40.6 | 45.8 | 49.5 | <0.0001 |

| Use of antihypertensive, % | 6.6 | 5.6 | 7.7 | 6.5 | 7.0 | <0.0001 |

| Hyperlipidaemia, % | 32.4 | 36.6 | 36.5 | 39.0 | 42.7 | <0.0001 |

| Serum triglyceride, mmol/L | 1.5(1.2) | 1.7(1.3) | 1.6(1.3) | 1.7(1.4) | 1.8(1.5) | <0.0001 |

| Serum total cholesterol, mmol/L | 4.9(1.1) | 1.9(1.1) | 5.0(1.0) | 5.0(1.1) | 5.0(1.0) | <0.0001 |

| Serum HDL cholesterol, mmol/L | 1.6(0.4) | 1.6(0.4) | 1.6(0.4) | 1.6(0.4) | 1.6(0.4) | 0.005 |

| Serum LDL cholesterol, mmol/L | 2.1(0.9) | 2.2(0.9) | 2.2(0.9) | 2.3(0.9) | 2.1(0.8) | <0.0001 |

| Serum C-reactive protein, mg/L | 0.76(4.6) | 0.78(4.6) | 0.72(4.7) | 0.82(4.5) | 0.82(4.8) | <0.0001 |

| Occupation | ||||||

| Coal miner, % | 41.8 | 41.1 | 40.8 | 40.6 | 40.5 | <0.0001 |

| Blue-collar workers except coal miners, % | 52.4 | 54.4 | 53.9 | 55.1 | 51.4 | |

| White-collar workers, % | 5.8 | 4.6 | 5.3 | 4.3 | 5.1 | |

| Family history of diabetes, % | 6.8 | 6.8 | 7.1 | 7.5 | 7.3 | <0.0001 |

| Family history of cardiovascular disease, % | 6.2 | 5.5 | 6.4 | 5.3 | 6.0 | 0.24 |

| Women | ||||||

| n | 2823 | 3886 | 2740 | 3880 | 2309 | |

| Age, years | 48.5(11.1) | 46.8(11.1) | 47.9(11.2) | 46.3(11.3) | 45.9(12.2) | <0.0001 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 24.2(3.6) | 24.5(3.7) | 24.6(3.8) | 24.5(3.7) | 24.4(3.9) | 0.15 |

| Smoking status | ||||||

| Never, % | 97.0 | 97.7 | 98.1 | 98.5 | 98.6 | 0.02 |

| Past, % | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | |

| Current, % | 2.4 | 1.9 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 1.1 | |

| Alcohol drinking status | ||||||

| Never, % | 90.5 | 92.5 | 92.0 | 94.3 | 93.8 | <0.0001 |

| Past, % | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.4 | |

| Current, % | 8.8 | 7.1 | 7.6 | 5.5 | 5.8 | |

| Education | ||||||

| Illiteracy/Primary, % | 4.6 | 4.1 | 4.5 | 3.7 | 3.6 | 0.001 |

| High school, % | 78.5 | 81.6 | 81.7 | 83.5 | 81.4 | |

| College or higher, % | 16.9 | 14.3 | 13.8 | 12.8 | 15.0 | |

| Exercise 2 x time/wk, % | 13.1 | 12.5 | 18.1 | 11.7 | 9.4 | <0.0001 |

| Waist circumference, cm | 81.6(10.7) | 82.3(10.0) | 82.2(10.6) | 82.9(10.8) | 83.1(11.6) | <0.0001 |

| Hypertension, % | 22.7 | 26.3 | 28.7 | 27.9 | 32.4 | <0.0001 |

| Use of antihypertensive, % | 7.3 | 6.1 | 8.8 | 6.6 | 8.6 | 0.08 |

| Hyperlipidaemia, % | 28.9 | 28.7 | 30.0 | 29.8 | 30.8 | <0.0001 |

| Serum triglyceride, mmol/L | 1.3(1.0) | 1.4(1.1) | 1.4(1.0) | 1.4(1.1) | 1.5(1.2) | <0.0001 |

| Serum total cholesterol, mmol/L | 4.8(1.1) | 4.8(1.2) | 5.0(1.0) | 5.0(1.1) | 5.0(1.1) | <0.0001 |

| Serum HDL cholesterol, mmol/L | 1.55(0.4) | 1.56(0.4) | 1.53(0.4) | 1.51(0.4) | 1.56(0.4) | 0.001 |

| Serum LDL cholesterol, mmol/L | 2.2(0.9) | 2.4(0.9) | 2.3(0.9) | 2.5(0.9) | 2.4(0.9) | 0.01 |

| Serum C-reactive protein, mg/L | 0.80(4.6) | 0.80(4.7) | 0.76(4.5) | 0.83(4.5) | 0.80(4.8) | 0.98 |

| Occupation | ||||||

| Coal miner, % | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.2 | 0.2 | <0.0001 |

| Blue-collar workers except coal-miners | 83.7 | 86.0 | 84.5 | 87.0 | 86.5 | |

| White-collar workers | 15.9 | 13.6 | 15.5 | 12.8 | 13.3 | |

| Post-menopause in 2010, % | 67.3 | 67.4 | 72.3 | 74.1 | 75.6 | <0.0001 |

| Family history of cardiovascular disease, % | 8.9 | 7.0 | 7.7 | 6.4 | 7.2 | 0.02 |

| Family history of diabetes, % | 12.1 | 10.0 | 10.4 | 9.3 | 10.4 | 0.02 |

aRange of the top heart rate quintile was 81–180.

In total, 4649 participants were diagnosed as incident cases of diabetes during 333 024 person-years of follow-up. The adjusted HR for the highest vs lowest quintile of resting heart rate was 1.73 (95% CI: 1.57, 1.91), after adjustment for age, smoking, blood concentrations of TG and glucose, and other covariates. Each 10 beats/min increase in heart rate was associated with 23% (95% CI: 19%, 27%) increased diabetes risk, comparable to the risk related to 3 kg/m2 increase in BMI (adjusted RR = 1.26%, 95% CI: 1.23, 1.29). The positive association between resting heart rate and incident diabetes persisted when we further excluded participants with hypertension or those who were coal miners in our sensitivity analyses (Table 2).

Table 2.

Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for risk of diabetes according to resting heart rate quintiles in the Kailuan study, China, 2006–07

| Total diabetes | Quintiles of heart rate |

Each 10 b/m increment | P-trend | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | |||

| Resting heart rate, median, b/m | 61 | 70 | 72 | 78 | 88a | ||

| Number of cases | 690 | 988 | 718 | 1227 | 1026 | ||

| Crude incidence/100 000 person-years | 1059 | 1208 | 1385 | 1506 | 1943 | ||

| Model 1 | 1 | 1.22(1.11,1.35) | 1.34 (1.21, 1.49) | 1.47 (1.33, 1.61) | 2.01 (1.82, 2.21) | 1.29(1.25,1.34) | <0.0001 |

| Model 2 | 1 | 1.18(1.07–1.30) | 1.29 (1.16–1.43) | 1.40 (1.28–1.54) | 1.96 (1.78–2.16) | 1.29(1.24,1.33) | <0.0001 |

| Model 3 (overall) | 1 | 1.12(1.02–1.24) | 1.24 (1.12–1.38) | 1.32 (1.20–1.45) | 1.73 (1.57–1.91) | 1.23(1.19,1.27) | <0.0001 |

| Men | 1 | 1.14(1.03–1.27) | 1.21 (1.08–1.36) | 1.33 (1.20–1.47) | 1.76 (1.58–1.95) | 1.19(1.09,1.31) | <0.0001 |

| Women | 1 | 1.07(0.83–1.38) | 1.42 (1.10–1.84) | 1.29 (1.00–1.65) | 1.62 (1.25–2.11) | 1.24(1.19,1.28) | 0.0001 |

| Sensitivity analyses | |||||||

| Model 4 | 1 | 1.17(1.01–1.34) | 1.26 (1.08–1.46) | 1.39 (1.21–1.59) | 1.84 (1.59–2.12) | 1.25(1.19,1.32) | <0.0001 |

| Model 5 | 1 | 1.14(1.00–1.29) | 1.34 (1.17–1.53) | 1.30 (1.15–1.47) | 1.68 (1.48–1.91) | 1.21(1.15,1.26) | <0.0001 |

Model 1: Adjusted for age (years) and sex.

Model 2: Adjusted for Model 1 and further adjusted for BMI (kg/m2).

Model 3: Adjusted for Model 2 and further adjusted for smoking status (never, past smoker, current smoker 1–19 cigarettes/day or current smoker 20+ cigarettes/day), alcohol drinking status (never, past drinker, current drinker <1 time/day or current drinker 1+ times/day), education (illiteracy/primary, high school or college or above), physical activity (never, 1–3 times/week, or 4+ times/week), occupation (white-collar workers, coal miners, blue-collar workers except coal miners), presence of hypertension and dyslipidaemia, plasma concentration of CRP, family history of diabetes and cardiovascular disease, and menopausal status (yes/no, for women only).

Model 4: Adjusted for model 3 and further excluded individuals with hypertension.

Model 5: Adjusted for model 3 and further excluded individuals who were coal miners.

Q, quintile; CRP, C-reactive protein; IFG, impaired fasting glucose; TG, triglyceride.

aRange of the top heart rate quintile was 81–180.

Faster heart rate was also associated with a higher risk of developing IFG among participants with normal fasting glucose on the baseline 2006 examination (Table 3). The adjusted HR for the highest vs lowest heart rate quintile was 1.33 (95% CI: 1.27, 1.39). Similarly, we observed a positive association between heart rate and risk of developing diabetes among participants with IFG (P-trend < 0.0001), with the adjusted HR for the highest vs lowest heart rate quintile being 1.40 (95% CI: 1.24, 1.57) (Table 4). Blood pressure was also used instead of hypertension in the adjusted models, and the results remained the same (data not shown).

Table 3.

Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for risk of impaired fasting glucose (IFG) according to resting heart rate quintiles in the Kailuan study, China, 2006–07

| IFG | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Each 10 b/m increment | P-trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resting heart rate, median, b/m | 61 | 70 | 72 | 78 | 88a | ||

| Number of subjects | 11 408 | 14 106 | 8843 | 9116 | 12 615 | ||

| Number of cases | 3250 | 4204 | 2660 | 2931 | 4418 | ||

| Crude incidence/100 000 person-years | 6819 | 7267 | 7361 | 7973 | 9158 | ||

| Model 1 | 1 | 1.12 (1.07–1.18) | 1.09 (1.03–1.15) | 1.20 (1.14–1.26) | 1.39 (1.33–1.46) | 1.13(1.11,1.15) | <0.0001 |

| Model 2 | 1 | 1.11 (1.06–1.16) | 1.07 (1.02–1.13) | 1.18 (1.13–1.24) | 1.38 (1.32–1.44) | 1.13(1.11,1.15) | <0.0001 |

| Model 3 (overall) | 1 | 1.09 (1.04–1.14) | 1.07 (1.02–1.13) | 1.16 (1.10–1.22) | 1.33 (1.27–1.39) | 1.11(1.09,1.13) | <0.0001 |

| Men | 1 | 1.09 (1.03–1.14) | 1.06 (1.00–1.13) | 1.14 (1.08–1.20) | 1.32 (1.25–1.39) | 1.11(1.09,1.13) | <0.0001 |

| Women | 1 | 1.11 (0.99–1.23) | 1.10 (0.97–1.24) | 1.27 (1.13–1.43) | 1.35 (1.21–1.51) | 1.12(1.08,1.17) | <0.0001 |

| Sensitivity analyses | |||||||

| Model 4 | 1 | 1.13 (1.06–1.20) | 1.10 (1.03–1.18) | 1.22 (1.14–1.30) | 1.40 (1.32–1.49) | 1.13(1.11,1.16) | <0.0001 |

| Model 5 | 1 | 1.09 (1.02–1.15) | 1.12 (1.05–1.19) | 1.20 (1.13–1.28) | 1.35 (1.28–1.44) | 1.12(1.10,1.14) | <0.0001 |

Model 1: Adjusted for age (years) and sex.

Model 2: Adjusted for Model 1 and further adjusted for BMI (kg/m2).

Model 3: Adjusted for Model 2 and further adjusted for smoking status (never, past smoker, current smoker 1–19 cigarettes/day or current smoker 20+ cigarettes/day), alcohol drinking status (never, past drinker, current drinker <1 time/day or current drinker 1+ times/day), education (illiteracy/primary, high school or college or above), physical activity (never, 1–3 times/week, or 4+ times/week), occupation (white-collar workers, coal-miners, blue-collar workers except coal-miners), presence of hypertension and dyslipidaemia, plasma concentration of CRP, family history of diabetes and cardiovascular disease, and menopausal status (yes/no, for women only).

Model 4: Adjusted for model 3 and further excluded individuals with hypertension.

Model 5: Adjusted for model 3 and further excluded individuals who were coal miners.

Q, quintile; CRP, C-reactive protein; TG, triglyceride; b/m, beats per min.

aRange of the top heart rate quintile was 81–180.

Table 4.

Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for risk of conversion from impaired fasting glucose (IFG) to diabetes according to resting heart rate quintiles in the Kailuan study, China, 2006–07

| Diabetes | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Each 10 b/m increment | P-trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resting heart rate, median, b/m | 61 | 70 | 72 | 78 | 88a | ||

| Number of subjects | 3219 | 3568 | 4010 | 3097 | 3375 | ||

| Number of cases | 486 | 574 | 676 | 495 | 662 | ||

| Crude incidence/100 000 person-years | 3745 | 3914 | 4150 | 3982 | 4680 | ||

| Model 1 | 1 | 1.13 (1.00–1.28) | 1.19 (1.06–1.34) | 1.14 (1.00–1.29) | 1.48 (1.31–1.66) | 1.14(1.10,1.19) | <0.0001 |

| Model 2 | 1 | 1.11 (0.99–1.26) | 1.17 (1.04–1.32) | 1.13 (0.99–1.28) | 1.50 (1.33–1.69) | 1.15(1.11,1.20) | <0.0001 |

| Model 3 (overall) | 1 | 1.09 (0.96–1.23) | 1.16 (1.03–1.31) | 1.10 (0.97–1.25) | 1.40 (1.24–1.57) | 1.13(1.08,1.17) | <0.0001 |

| Men | 1 | 1.08 (0.95–1.23) | 1.13 (0.99–1.28) | 1.10 (0.96–1.26) | 1.39 (1.22–1.58) | 1.13(1.07,1.18) | <0.0001 |

| Women | 1 | 1.19 (0.85–1.69) | 1.27 (0.92–1.75) | 1.16 (0.80–1.66) | 1.43 (1.02–2.00) | 1.12(1.00,1.25) | 0.06 |

| Sensitivity analyses | |||||||

| Model 4 | 1 | 1.01 (0.85–1.20) | 1.10 (0.93–1.31) | 1.05 (0.87–1.26) | 1.41 (1.18–1.69) | 1.13(1.06,1.21) | <0.0001 |

| Model 5 | 1 | 1.19 (1.02–1.40) | 1.23 (1.05–1.43) | 1.09 (0.92–1.29) | 1.46 (1.25–1.70) | 1.13(1.07,1.19) | <0.0001 |

Model 1: Adjusted for age (years) and sex.

Model 2: Adjusted for Model 1 and further adjusted for BMI (kg/m2).

Model 3: Adjusted for Model 2 and further adjusted for smoking status (never, past smoker, current smoker 1–19 cigarettes/day or current smoker 20+ cigarettes/day), alcohol drinking status (never, past drinker, current drinker <1 time/day or current drinker 1+ times/daay), education (illiteracy/primary, high school or college or above), physical activity (never, 1–3 times/week or 4+ times/week), occupation (white-collar workers, coal miners, blue-collar workers except coal miners), presence of hypertension and dyslipidaemia, plasma concentration of CRP, family history of diabetes and cardiovascular disease, and menopausal status (yes/no, for women only).

Model 4: Adjusted for Model 3 and further excluded individuals with hypertension.

Model 5: Adjusted for Model 3 and further excluded individuals who were coal miners.

Q, quintile; CRP, C-reactive protein; TG, triglyceride; b/m, beats per min.

aRange of the top heart rate quintile was 81–180.

We found a significant interaction between resting heart rate and age (years) (P-interaction < 0.02 for both), but not for sex, BMI, physical activity, current smoking (yes/no) or drinking (yes/no) or presence of hyperlipidaemia (P-interaction > 0.05 for all), in relation to risk of diabetes and IFG. Similar results were observed in the subgroup analysis based on physical activity level (data not shown). The association was slightly stronger among participants aged younger than 50 years than those aged 50 years or older (eTable 2, available as Supplementary data at IJE online). The adjusted HRs for the each 10 beats/min increase in heart rate were 1.27 (95% CI: 1.20, 1.34) for diabetes and 1.15 (95% CI: 1.12, 1.18) for IFG among younger participants. The relevant HRs were 1.20 (95% CI: 1.15, 1.26) and 1.08 (95% CI: 1.06, 1.11) among older participants, respectively. In contrast, we did not observe a significant interaction between heart rate and age, in relation to risk of conversion from IFG to diabetes (P-interaction = 0.28).

Figure 1 summarizes the association between heart rate and diabetes risk, based on seven previously published prospective studies and the current study. Overall, faster heart rate was associated with a higher risk of developing diabetes (pooled HR for the highest vs lowest heart rate categories = 1.59, 95% CI: 1.27, 2.00). There was evidence of heterogeneity across studies (P < 0.001 for heterogeneity), which was mainly driven by a study with small sample size.8 The Begg and Egger tests did not suggest existence of potential publication bias (P > 0.1 for both).

Figure 1.

Meta-analysis of resting heart rate for the highest vs lowest heart rate categories and the risk of developing diabetes.

Discussion

The current study represents the largest longitudinal prospective study investigating the independent association between resting heart rate and risk of developing diabetes and IFG. We observed a dose-response association between higher resting heart rate and a higher risk of developing diabetes, IFG and conversion from IFG to diabetes, even after adjustment for potential confounders of this relationship. Furthermore, a meta-analysis of seven published studies and the current results confirmed the positive association between resting heart rate and diabetes risks. Altogether, this study strongly supports faster resting heart rate as an independent risk factor for incident diabetes and IFG, and suggests that this relationship may be common to developing and developed countries, as well as Asian and non-Asian populations.

Age, BMI and lifestyle factors are well established risk factors for the development of diabetes22,28,29 and also impact on heart rate. After adjusting for these confounders, the increasing trends in risk of developing diabetes were still observed across quintiles of resting heart rate in both sex. The findings of our study are generally consistent with previous prospective studies, as shown in the meta-analysis; however, our study contributes the largest study population to the meta-analysis. Consistently, in the aforementioned cross-sectional study including 46 239 Chinese adults aged 20 years or older, heart rate increase of 10 beats/min was associated with 29% increased odds of the prevalence of diabetes and 15% increased odds of the prevalence of prediabetes (based on FBG, IGT or HbA1c concentrations).3 The other cross-sectional study including 30 519 Chinese participants (aged 55 years or above) of the Guangzhou Biobank Cohort in Southern China reported that participants with a high vs low resting heart rate were 2.59 times more likely to have type 2 diabetes.16 The positive impact of heart rate was also observed on developing IFG among this Chinese population (adjusted OR = 1.47). Similar results were reported in a previous US study.17 In this cross-sectional study including 1267 adults (mean age = 72 years), IFG was associated with higher heart rate and lower heart rate variability, relative to those with normoglycaemia.17

A resting heart rate is generally considered as a surrogate marker for autonomic activity,6 and increased sympathetic nerve system activity induces both acute and chronic insulin resistance.30–32 Several mechanisms have been proposed by which sympathetic activation may lead to higher diabetes risk.33 One of the most important mechanisms might be that sympathetic activation causes vasoconstriction and decreases skeletal muscle blood flow, resulting in the impairment of glucose uptake into the skeletal muscle.34 Additionally, sympathetic activation has been associated with many diabetes-related risk factors, including reduced insulin sensitivity, high BP, obesity, subclinical inflammation and the metabolic syndrome.8,35–38 Ultimately, the exact mechanism by which increased heart rate is induced, or why sympathetic outflow would be increased in high-risk individuals, remains to be elucidated; however, our findings suggest that this area of investigation may be relevant for future preventive and prognostic indications. It has been suggested that the measurement of heart rate contributes to identifying subjects who are most likely to develop hypertension, obesity, the metabolic syndrome and diabetes.39

Interestingly, the association between heart rate and incident diabetes and IFG was stronger among younger individuals. This could be due to the fact that heart rate may be more representative of sympathetic predominance in participants of younger age. Carnethon et al. similarly observed a significant age-heart rate interaction in relation to diabetes mortality9 when they reported that higher heart rate was significantly associated with diabetes mortality in participants aged 35–49 years at baseline, but not among participants aged 50 years or older. In this study the authors did not observe a significant gender-difference in the association between heart rate and risks of diagnosis of diabetes.9 In this context, more studies are needed to replicate our findings and investigate potential biological mechanisms underlying the age-heart rate interaction.

Strengths

To our knowledge, this study is the first prospective study to address the independent effect of resting heart rate on the incidence of diabetes and IFG in both Chinese men and women and the first meta-analysis for investigating the association between heart rate and diabetes risk, providing a basis for the health policy implication of diabetes prevention. Other strengths of our study included electrocardiogram-determined resting heart rate, large sample size, and availability of several important potential confounders such as blood concentrations of C-reactive protein and glucose.

Limitations

Several limitations should be considered in interpreting the current results. Although we attempted to control for all relevant potential confounders available to us, we cannot eliminate the residual confounding due to observational study design and failure to collect information on insulin level/sensitivity, anxiety and use of antidepressants.7 Second, all participants were employees of the Kailuan Coal Company, and their health insurance policies were covered by the Kailuan Medical Group; therefore, they cannot be viewed as a representative sample of the Chinese general population. However, studying such a geographically confined and controlled population greatly reduces residual confounding due to diverse socioeconomic factors and lifestyle patterns. Third, the diagnosis of diabetes and prediabetes status was based on a single measure of FPG, which is due to lack of availability of oral glucose tolerance test data in such a large cohort.

The conclusions should be cautious regarding extension to prediction of prediabetes, because impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) was not included in the definition of prediabetes in the current study (likewise, predicting IGT to diabetes conversion). However, when the incident diabetes was restricted to those who had high glucose levels in both 2008 and 2010 follow-ups, we found similar association between heart rate and diabetes risk. We did not collect information regarding type of diabetes but, because of age range and lower prevalence of type 1 diabetes, a majority of incident cases should be type 2 diabetes.

Another limitation is that we failed to exclude participants with atrial fibrillation or other rhythm disturbances. However, all individuals with coronary artery disease and stroke were excluded in the primary analysis, and further excluding hypertensive patients did not change results materially, suggesting that the potential effects of these disorders could be modest. Further, due to its relative short follow-up, we are unable to examine the effects of changes in heart rate over time on diabetes risk, which would provide more insights regarding causality of the observed heart rate-diabetes relationship. Finally, heart rates ranged widely across the studies included in our meta-analysis. To reduce the potential effects of this heterogeneity on the pooled relative risk estimates, we used a random-effects model as it considers both within- and between-study variation.

Conclusions

Our findings provide further evidence that faster resting heart rate is associated with a higher risk of developing IFG and diabetes in a Chinese population, and the association is stronger in younger adults. Should these observations be confirmed, heart rate could be used to identify individuals with a higher future risk of diabetes.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data are available at IJE online.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [Nos. 81170244 and 81170090] and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health [Award Number K23HL111771]. None of the sponsors participated in the design of the study, nor in the collection, analysis or interpretation of the data.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Group Company of Chinese Kailuan. The contributions of the general practitioners of the Kailuan Study are gratefully acknowledged.

Contributions

X.G. and S.W. had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. L.W., L.C., S.W. and X.G. conceived study concept and design. L.W., L.C., Y.Wg, A.V., S.C., C.Z., Y.Z., D.L., F.H., S.W and X.G. contributed to data acquisition. L.W., L.C., F.H., S.W and X.G. did data analysis and interpretation. L.W., L.C. and X.G. drafted the manuscript. Y.W., A.V., S.C., C.Z., Y.Z., D.L., F.H. and S.W. critiqued the revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. L.W. and X.G. did statistical analysis. A.V. and S.W. obtained funding. Y.W., A.V., S.C., C.Z., Y.Z. and D.L. contributed to administrative, technical or material support. S.W. and X.G. supervised the study.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that there is no duality of interest associated with this manuscript.

References

- 1.Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, Sicree R, King H. Global prevalence of diabetes. Diabetes Care 2004;27:1047–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Fact Sheet: National Estimates and General Information on Diabetes and Prediabetes in the United States, 2011. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services (CDC), 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang W, Lu J, Weng J, et al. Prevalence of diabetes among men and women in China. N Engl J Med 2010;362:1090–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu Y, Wang L, He J, et al. Prevalence and control of diabetes in Chinese adults. JAMA 2013;310:94859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gu D, Gupta A, Muntner P, et al. Prevalence of cardiovascular disease risk factor clustering among the adult population of China: results from the International Collaborative Study of Cardiovascular Disease in Asia (InterAsia). Circulation 2005;112:658–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grassi G, Vailati S, Bertinieri G, et al. Heart rate as marker of sympathetic activity. J Hypertens 1998;16:1635–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grantham NM, Magliano DJ, Tanamas SK, Söderberg S, Schlaich MP, Shaw JE. Higher heart rate increases risk of diabetes among men: The Australian diabetes obesity and lifestyle study. Diabet Med 2013;30:421–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shigetoh Y, Adachi H, Yamagishi S, et al. Higher heart rate may predispose to obesity and diabetes mellitus: 20-year prospective study in a general population. Am J Hypertens 2009;22:151–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carnethon MR, Yan L, Greenland P, et al. Resting heart rate in middle age and diabetes development in older age. Diabetes Care 2008;31:335–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carnethon MR, Golden SH, Folsom AR, Haskell W, Liao D. Prospective investigation of autonomic nervous system function and the development of type 2 diabetes: the Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities study, 1987–1998. Circulation 2003;107:2190–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carnethon MR, Prineas RJ, Temprosa M, et al. The association among autonomic nervous system function, incident diabetes, and intervention arm in the Diabetes Prevention Program. Diabetes Care 2006; 29:914–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nagaya T, Yoshida H, Takahashi H, Kawai M. Resting heart rate and blood pressure, independent of each other, proportionally raise the risk for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Int J Epidemiol 2010;39:215–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bemelmans RH, Wassink AM, van der Graaf Y, et al. Risk of elevated resting heart rate on the development of type 2 diabetes in patients with clinically manifest vascular diseases. Eur J Endocrinol 2012;166:717–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang X, Shu XO, Xiang YB, et al. Resting heart rate and risk of type 2 diabetes in women. Int J Epidemiol 2010;39:900–06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeFronzo RA, Abdul-Ghani M. Assessment and treatment of cardiovascular risk in prediabetes: impaired glucose tolerance and impaired fasting glucose. Am J Cardiol 108(Suppl 3):3B–24B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.ó Hartaigh B, Jiang CQ, Bosch JA, et al. Independent and combined associations of abdominal obesity and seated resting heart rate with type 2 diabetes among older Chinese: the Guangzhou Biobank Cohort Study. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2011;27:298–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stein PK, Barzilay JI, Domitrovich PP, et al. The relationship of heart rate and heart rate variability to non-diabetic fasting glucose and the metabolic syndrome: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Diabet Med 2007;24:855–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Panzer C, Lauer MS, Brieke A, Blackstone E, Hoogwerf B. Association of fasting plasma glucose with heart rate recovery in healthy adults: a population-based study. Diabetes 2002;51:803–07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu S, Huang Z, Yang X, et al. Prevalence of ideal cardiovascular health and its relationship with the 4-year cardiovascular events in a northern Chinese industrial city. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2012;5:48793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Q, Zhou Y, Gao X, et al. Ideal cardiovascular health metrics and the risks of ischemic and intracerebral hemorrhagic stroke. Stroke 2013;44:2451–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Diabetic Association. Report of the expert committee on the diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes 2003;Suppl 1:S5–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hu FB, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, et al. Diet, lifestyle, and the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in women. N Engl J Med 2001;345:790–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoshide S, Kario K, Ishikawa J, Eguchi K, Shimada K. Comparison of the effects of cilnidipine and amlodipine on ambulatory blood pressure. Hypertens Res 2005;28:1003–08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuramoto K, Ichikawa S, Hirai A, Kanada S, Nakachi T, Ogihara T. Azelnidipine and amlodipine: a comparison of their pharmacokinetics and effects on ambulatory blood pressure. Hypertens Res 2003;26:201–08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Higgins JP, Thompson SC. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 2002;21:1539–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986;7:177–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics 1994;50:1088–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chan JM, Rimm EB, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC. Obesity, fat distribution, and weight gain as risk factors for clinical diabetes in men. Diabetes Care 1994;17:961–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Dan RM. The epidemiology of lifestyle and risk factor for type 2 diabetes. Eur J Epidemiol 2003;18:1115–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jamerson KA, Julius S, Gudbrandsson T, Andersson O, Brant DO. Reflex sympathetic activation induces acute insulin resistance in the human forearm. Hypertension 1993;21:618–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Masuo K, Mikami H, Ogihara T, Tuck ML. Sympathetic nerve hyperactivity precedes hyperinsulinemia and blood pressure elevation in a young, nonobese Japanese population. Am J Hypertens 1997; 10:77–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palatini P, Mos L, Santonastaso M, et al. Resting heart rate as a predictor of body weight gain in the early stage of hypertension. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011;19:618–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Julius S, Jamerson K. Sympathetics, insulin resistance and coronary risk in hypertension: the ‘chicken-and-egg’ question. J Hypertens 1994;12:495–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Julius S, Gudbrandsson T, Jamerson K, Andersson O. The interconnection between sympathetics, microcirculation, and insulin resistance in hypertension. Blood Press 1992;1:9–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Flanagan DE, Vaile JC, Petley GW, et al. The autonomic control of heart rate and insulin resistance in young adults. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1999;84:1263–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mancia G, Bousquet P, Elghozi JL, et al. The sympathetic nervous system and the metabolic syndrome. J Hypertens 2007;25:909–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sajadieh A, Nielsen OW, Rasmussen V, Hein HO, Abedini S, Hansen JF. Increased heart rate and reduced heart-rate variability are associated with subclinical inflammation in middle-aged and elderly subjects with no apparent heart disease. Eur Heart J 2004;25:363–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shibao C, Gamboa A, Diedrich A, et al. Autonomic contribution to blood pressure and metabolism in obesity. Hypertension 2007; 49:27–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Palatini P. Role of elevated heart rate in the development of cardiovascular disease in hypertension. Hypertension. 2011; 58:745–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.