Abstract

Background.

The hormone klotho is encoded by aging-suppressor gene klotho and has multiple roles, including regulating mineral (calcium and phosphate) homeostasis. Vitamin D also regulates mineral homeostasis and upregulates klotho expression. Klotho positively relates to longevity, upper-extremity strength, and reduced disability in older adults; however, it is unknown whether circulating klotho relates to lower-extremity physical performance or whether the relation of vitamin D with physical performance is mediated by klotho.

Methods.

Klotho and 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] were measured in 860 participants aged ≥ 55 years in Invecchiare in Chianti, “Aging in Chianti” (InCHIANTI), a prospective cohort study comprising Italian adults. Lower-extremity physical performance was measured using the Short Physical Performance Battery, a summary score of balance, chair stand ability, and walking speed. Weighted estimating equations related plasma klotho and serum 25(OH)D concentrations measured at one visit to Short Physical Performance Battery measured longitudinally at multiple visits.

Results.

Each additional natural log of klotho (pg/mL) was associated with 0.47 higher average Short Physical Performance Battery scores (95% confidence interval: 0.08 to 0.86, p value = .02) after adjustment for covariates, including 25(OH)D. Each natural log of 25(OH)D (ng/mL) was associated with 0.61 higher average Short Physical Performance Battery scores (95% confidence interval: 0.35 to 0.88, p value < .001) after adjustment for covariates, a result that changed little after adjustment for klotho.

Conclusions.

Plasma klotho and 25(OH)D both positively related to lower-extremity physical performance. However, the findings did not support the hypothesis that klotho mediates the relation of 25(OH)D with physical performance.

Key Words: Biomarkers, Epidemiology, Physical f, unction, Metabolism, Physical p, erformance.

Poor lower-extremity physical performance is associated with mortality, morbidity, and poor quality of life in older adults (1,2). Beyond exercise and physical activity interventions, there are limited options for preventing physical performance decline in older adults. Therefore, identifying factors associated with poor performance that may be modifiable targets for interventions is central to gerontology research. Klotho, a recently discovered hormone with antiaging properties in animal models (3), may play a role in physical performance. The aging-suppressor gene klotho encodes klotho, a single-pass transmembrane protein that is predominantly expressed in the distal tubule cells of the kidney, parathyroid glands, and choroid plexus of the brain. Klotho-deficient mice exhibit accelerated aging, including low bone mineral density, sarcopenia, and shortened life span; whereas mice that overexpress klotho exhibit enhanced longevity and health span (3–5).

Two homologous, yet functionally distinct, forms of klotho exist: membrane and secreted. These forms share about 41% amino acid identity, but are expressed in different tissues (6). Membrane klotho, known as β-klotho, is coreceptor for fibroblast growth factor 23, a hormone produced by bone cells that regulates phosphate homeostasis (7). Secreted klotho, known as α-klotho, is involved in calcium homeostasis in the kidney and inhibition of intracellular insulin and insulin-like growth factor-1 signaling (5). Klotho has been shown to positively relate to longevity (8), upper-extremity strength (9), and negatively relate to activities of daily living disability (10) and morbidity (11) in older community-dwelling adults; however, it is unknown whether klotho relates to lower-extremity physical performance in this population.

The discovery of klotho has altered the traditional conceptual framework of mineral (calcium and phosphate) homeostasis, which was based on the pathway involving circulating vitamin D and parathyroid hormone (PTH) (12,13). Recent research suggests that the vitamin D/PTH pathway regulates the klotho/fibroblast growth factor 23 pathway, and vice versa. Specifically, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D [1,25(OH)D2], the metabolically active form of vitamin D, upregulates expression of klotho (14), PTH may indirectly upregulate klotho by upregulating 1,25(OH)D2 (12), and klotho may indirectly downregulate PTH as a fibroblast growth factor 23 coreceptor, although the latter mechanism is more controversial (15).

Multiple reports have shown that circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D], the gold standard for vitamin D body stores and substrate for 1,25(OH)D2, positively relates to physical performance in older adults (16–20). However, it is unknown whether the relation of 25(OH)D with lower-extremity physical performance can be explained (ie, is mediated) by its putative effect on klotho.

We hypothesize that, independent of confounders, (i) plasma klotho concentrations positively relate to lower-extremity physical performance in older adults and (ii) the relation of serum 25(OH)D with lower-extremity physical performance is mediated in part by klotho. We test these hypotheses in a large prospective study of older community-dwelling adults.

Methods

Participants and Data Collection

Participants included men and women enrolled in the Invecchiare in Chianti, “Aging in Chianti” (InCHIANTI) Study aged ≥55 years at the time of their scheduled blood draw for klotho measurement. The design and conduct of InCHIANTI has been described elsewhere (21). Briefly, adults were randomly selected in 1998 from population registries of two Italian towns (Greve in Chianti and Bagno a Ripoli); 1,453 adults were enrolled during 1998–2000. Participants received an extensive description of the study and participated after providing written informed consent. The Italian National Institute of Research and Care on Aging Ethical Committee approved the study protocol. The Johns Hopkins University Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Among enrollees, 1,167 participants returned for a 3-year visit from 2001 to 2003, among whom 985 were aged ≥55 years. Among participants who would have been aged ≥55 years at the scheduled 3-year visit, 143 died before the visit. Of the 985 returning participants, 860 underwent a blood draw for analysis of klotho and were included in our study. Plasma klotho was measured at the 3-year visit owing to greater availability of stored plasma as compared with the enrollment visit. Of 860 participants aged ≥55 years with measured klotho, 734 returned for a 6-year visit (2004–2006), and 615 returned for a 9-year visit (2007–2009); 99 died before the 6-year visit, another 98 died before the 9-year visit, and the remainder were alive but missed follow-up visits.

Study visits consisted of trained interviewers administering in-home surveys, and physicians and physical therapists performing and administering medical examinations and physical function tests, respectively, in the study clinic.

Measures

Lower-extremity physical p

Performance

We included lower-extremity physical performance assessed at 3-, 6-, and 9-year visits. We operationalized lower-extremity physical performance using the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) derived from lower-extremity performance tests used in the Established Populations for the Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly (22). SPPB comprised assessments of balance, chair stand ability, and walking speed. Balance was measured by participants’ ability to stand in three increasingly difficult positions for 10 seconds each: a side-by-side position, a semitandem position, and a full-tandem position. Chair stand ability was measured by participants’ time to stand up and sit down in a chair with hands folded across their chest for five repetitions. Walking speed was the fastest of two 4-m walks at usual pace (canes and walkers permitted). Each measure was converted into a score ranging from 0 (unable) to 4 (highest level of performance). The three scores were summed to produce the SPPB summary score ranging from 0 (worst) to 12 (best). The summary and three component scores were the outcomes for the current study.

Biomarkers

Biomarkers were assessed using samples collected at the 3-year visit. Blood samples were collected in the morning after a 12-hour fast. Aliquots of serum and plasma were immediately obtained and stored at −80°C.

Klotho

Soluble α-klotho was measured in EDTA plasma using a solid-phase sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Immuno-Biological Laboratories, Takasaki, Japan) (23). The minimum assay detection limit is 6.15 pg/mL, which is lower than plasma concentrations found here. Intra-assay and interassay coefficients of variation were 4.1% and 8.9%, respectively, in one investigator’s (R.D.S.) laboratory. A published study and an internal pilot study found evidence that the klotho molecule is stable for multiple freeze-thaw cycles (23). The designation α-klotho describes the original klotho gene and its product (24) and distinguishes it from a homolog β-klotho (6). Henceforth, “klotho” refers to α-klotho.

25-hydroxyvitamin D

Serum 25(OH)D was measured using an enzyme immunoassay (OCTEIA 25-Hydroxy Vitamin D kit; Immunodiagnostic Systems, Inc., Fountain Hills, AZ) with intra-assay and interassay coefficients of variation ranging 5.3%–6.7% and 4.6%–8.7%, respectively.

Other biomarkers

Serum intact PTH concentrations were measured with two-site chemiluminescent enzyme-labeled immunometric assay (Intact PTH; Diagnostic Products Corporation, Los Angeles, CA) and an IMMULITE 2000 Analyzer (Siemens Medical Solutions Diagnostics, Tarrytown, NY) with intra-assay and interassay coefficients of variation ranging 4.2%–5.7% and 6.3%–8.8%, respectively. Serum creatinine levels were measured using a kinetic-colorimetric assay based on a rate-blanked and compensated modified Jaffé method for a Roche/Hitachi analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) with intra-assay and interassay coefficients of variation of 0.7% and 2.3%, respectively. Serum creatinine was standardized to estimate glomerular filtration rate via the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation (25).

Other Covariates

All covariates were collected at the 3-year visit, unless otherwise noted. Alcohol consumption (drinks/week) and calcium intake (mg/day) were assessed using the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition questionnaire. Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) measured cognitive function. Comorbidities (hypertension, congestive heart failure, peripheral arterial disease, stroke, diabetes, cancer, osteoporosis, and renal disease) were determined using adjudicated measures combining self-report, medical records, and clinical examination. Self-reported physical activity was categorized as moderate-to-intense exercise ≥3 hours per week (moderate-to-high activity), light exercise ≥2 hours per week or moderate exercise 1–2 hours per week (low activity), or sedentary/mostly sitting/some walking (inactive). We included physical activity at the enrollment visit, because subsequent activity may be affected by physical performance. We also ascertained age, education (years of schooling), smoking (pack-years), sex, and blood collection season. Body mass index (kg/m2) was measured.

Statistical Analysis

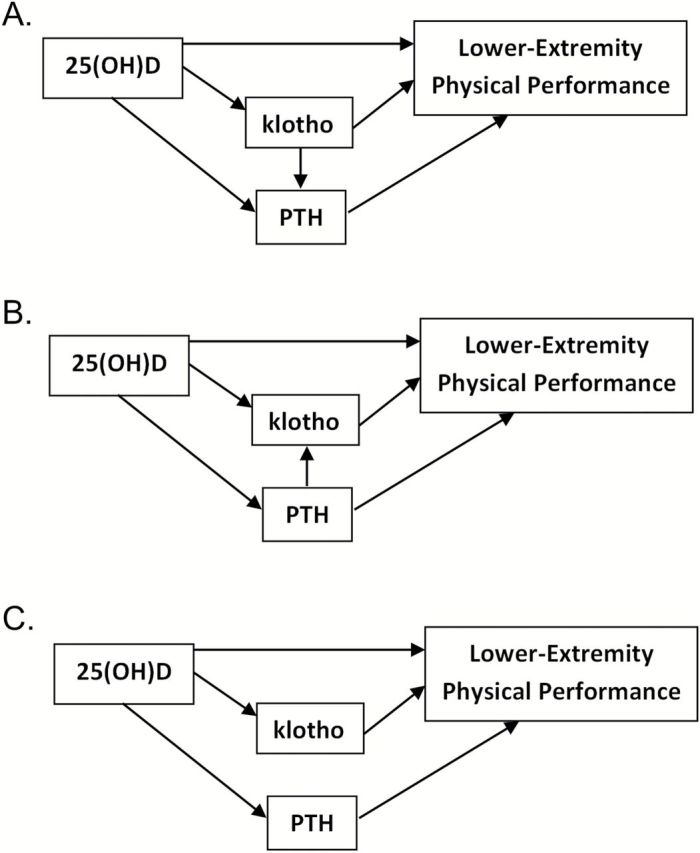

Weighted generalized estimating equations related longitudinal SPPB summary score and each component score (balance, chair stand, and walk) to the natural log of plasma klotho, ln(klotho). We fit three models for each outcome. Model 1 adjusted for study visit, age, sex, and visit-by-age interactions. Model 2 additionally adjusted for natural log of 25(OH)D (ln[25(OH)D]), estimated glomerular filtration rate, calcium and alcohol intake, smoking, body mass index, MMSE, years of education, physical activity, history of falls, and comorbidities. Model 3 additionally adjusted for PTH and a PTH-by-ln[25(OH)D] interaction. Models 2 and 3 included 25(OH)D as a potential confounder; however, there is uncertainty in the scientific community about regulation between klotho and PTH (particularly with simultaneously measured biomarkers) (15). Model 2 is appropriate to model the directed acyclic graph (26) in Figure 1A, where PTH mediates the effect of klotho on physical performance; Model 3 is appropriate to model Figure 1B, where PTH confounds the effect of klotho on physical performance; and both models are appropriate for Figure 1C where klotho and PTH independently affect lower-extremity physical performance. We used inverse-probability weighting to address missing data and selective survival (see Supplementary Material for details) (27). Directed acyclic graphs convey relations between variables differently than in the regulation pathway figures often used in endocrinology (eg, no feedback loops in directed acyclic graphs). Supplementary material (see Supplementary Figure 1) includes an explanation of these differences.

Figure 1.

Directed acyclic graphs depicting possible pathways linking 25(OH)D, klotho, and PTH to lower-extremity physical performance. In all pathways (A–C), klotho and PTH are hypothesized mediators of 25(OH)D on lower-extremity physical performance. (A) PTH mediates the effect of klotho on lower-extremity physical performance (Model 2 and Mediation Model 1 appropriate); (B) PTH confounds the effect of klotho on lower-extremity physical performance (Model 3 and Mediation Model 2 appropriate); (C) Klotho and PTH affect lower-extremity physical performance through separate pathways (all models appropriate). 25(OH)D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D; PTH, parathyroid hormone.

Finally, we estimated the direct effect of 25(OH)D on lower-extremity physical performance; that is, the effect not mediated by klotho. For each outcome, we first obtained an estimate of the total effect of ln[25(OH)D] on performance using inverse-probability weighted generalized estimating equations with adjustment for covariates in Model 2 and blood collection season (Total Effect Model). Next, we fit two models, one appropriate for Figure 1A (Mediation Model 1), and another appropriate for Figure 1B (Mediation Model 2). Mediation Model 1 added ln(klotho) to the Total Effect Model, where the resulting beta estimate for ln[25(OH)D] combines the direct effect of 25(OH)D and the indirect effect of 25(OH)D through PTH unmediated by klotho (ie, holding klotho “fixed”). Since this approach is only appropriate if no effects of 25(OH)D confound the relation of klotho with physical performance, and there is uncertainty about regulation pathways, we fit Mediation Model 2 using an alternative weighting strategy. Mediation Model 2 involved weighting to control for PTH as a confounder of the relation between klotho and lower-extremity physical performance (see Supplementary Material) (28). Statistical significance was defined as p value < .05 for all analyses.

Results

Table 1 shows that participants with plasma klotho >669 pg/mL (median), on average, were younger, consumed fewer alcoholic drinks, had higher MMSE scores, were more likely to be female and to have been diagnosed with congestive heart failure, and were less likely to have fallen than those with lower klotho (≤669 pg/mL; all p value < .05). We did not find significant associations of plasma klotho concentrations with 25(OH)D concentrations, PTH concentrations, or estimated glomerular filtration rate (all p value > .15). Participants with higher plasma klotho had higher average SPPB summary and component scores (balance, chair stand, and walk) at 3- and 6-year follow-up visits (all p value < .01). SPPB scores were higher at the 9-year follow-up visit for participants with higher versus lower plasma klotho; however, only chair stand scores were significantly different (p value = .03).

Table 1.

Characteristics of 860 InCHIANTI Participants by Plasma Klotho Concentration (median = 669 pg/mL)

| Characteristics | Klotho >669 pg/mL (N = 432) | Klotho ≤669 pg/mL (N = 428) | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD), Number (%), or Median (IQR) | N | Mean (SD), Number (%), or Median (IQR) | N | ||

| Age (y) | 74.3 (7.6) | 432 | 76.3 (8.2) | 428 | <.001 |

| Education (y) | 5.6 (3.2) | 432 | 5.8 (3.8) | 428 | .34 |

| Smoking (pack-years) | 11.0 (19.2) | 432 | 13.3 (20.4) | 427 | .09 |

| Alcohol consumption (drinks/wk) | 6.3 (8.3) | 409 | 7.6 (9.0) | 401 | .03 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 26.6 (4.0) | 422 | 26.3 (3.9) | 412 | .28 |

| MMSE score | 25.5 (4.5) | 430 | 24.5 (5.4) | 426 | .005 |

| Female sex | 255 (59.0%) | 432 | 223 (52.1%) | 428 | .04 |

| Hypertension | 154 (35.6%) | 432 | 132 (30.8%) | 428 | .14 |

| Congestive heart failure | 20 (4.6%) | 432 | 34 (7.9%) | 428 | .04 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 37 (8.6%) | 432 | 41 (9.6%) | 428 | .60 |

| Stroke | 23 (5.3%) | 432 | 33 (7.7%) | 428 | .16 |

| Diabetes | 44 (10.2%) | 432 | 52 (12.1%) | 428 | .36 |

| Cancer | 8 (1.9%) | 432 | 12 (2.8%) | 428 | .35 |

| Renal disease | 282 (65.3%) | 432 | 264 (61.7%) | 428 | .27 |

| Osteoporosis | 103 (23.8%) | 432 | 87 (20.3%) | 428 | .21 |

| Fallen in the past 12 mo | 77 (17.8%) | 432 | 100 (23.4%) | 428 | .044 |

| Physical activity: | 432 | 428 | .68 | ||

| Inactive | 71 (16.4%) | 76 (17.8%) | |||

| Low | 329 (76.2%) | 326 (76.2%) | |||

| Moderate-to-high | 32 (7.4%) | 26 (6.1%) | |||

| Blood collection season | 432 | 428 | .25 | ||

| Winter (December to February) | 149 (34.5%) | 173 (40.4%) | |||

| Spring (March to May) | 123 (28.5%) | 119 (27.8%) | |||

| Summer (June to August) | 41 (9.5%) | 39 (9.1%) | |||

| Fall (September to November) | 119 (27.5%) | 97 (22.7%) | |||

| 25-hydroxyvitamin D (ng/mL) | 29.8 (21.3, 51.2) | 432 | 29.7 (18.9, 45.3) | 427 | .16 |

| Calcium intake (mg/d) | 788 (625, 998) | 409 | 824 (673, 1,029) | 401 | .13 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 67.5 (56.1, 79.6) | 428 | 67 (55.2, 80.2) | 423 | .55 |

| Klotho (pg/mL) | 813 (738, 930) | 432 | 522 (443, 596) | 428 | |

| Parathyroid hormone (ng/L) | 41 (30, 60) | 432 | 41 (29, 59) | 427 | .47 |

| SPPB summary score, 3-y visit | 8.2 (2.4) | 420 | 7.6 (3.0) | 414 | <.001 |

| SPPB summary score, 6-y visit | 8.0 (2.5) | 346 | 7.3 (3.1) | 311 | .001 |

| SPPB summary score, 9-y visit | 8.3 (2.4) | 260 | 7.8 (2.8) | 234 | .08 |

| SPPB balance score, 3-y visit | 3.5 (1.1) | 426 | 3.2 (1.4) | 424 | .001 |

| SPPB balance score, 6-y visit | 3.4 (1.1) | 354 | 3.1 (1.4) | 316 | .005 |

| SPPB balance score, 9-y visit | 3.4 (1.1) | 276 | 3.3 (1.3) | 255 | .09 |

| SPPB chair stand score, 3-y visit | 2.2 (0.9) | 426 | 2.0 (1.1) | 424 | .003 |

| SPPB chair stand score, 6-y visit | 2.1 (0.9) | 353 | 1.9 (1.1) | 318 | .004 |

| SPPB chair stand score, 9-y visit | 2.1 (0.9) | 278 | 2.0 (1.0) | 252 | .03 |

| SPPB walk score, 3-y visit | 2.5 (0.7) | 423 | 2.3 (1.0) | 418 | <.001 |

| SPPB walk score, 6-y visit | 2.4 (0.8) | 348 | 2.2 (1.0) | 313 | .002 |

| SPPB walk score, 9-y visit | 2.5 (0.8) | 262 | 2.4 (1.0) | 234 | .10 |

Notes: Continuous variables compared using two-sample t tests or Wilcoxon rank-sum tests; categorical variables compared using Fisher’s exact tests. MMSE (Mini-Mental State Examination) score range, 0–30; Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) summary score range, 0–12; SPPB balance, chair stand, and walk score range: 0–4. eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate; InCHIANTI = Invecchiare in Chianti, “Aging in Chianti”; IQR = interquartile range;

N = number with available data.

Participants with data missing due to death were older, had more comorbidities, lower MMSE scores, lower 25(OH)D and klotho, higher PTH, were more likely to be male, and had lower SPPB scores at earlier visits than survivors (all p value < .05). Similarly, survivors with missing data were older, had more comorbidities, lower MMSE scores, lower 25(OH)D, were more likely to be male, and had lower SPPB scores at earlier visits than survivors with complete data (all p value < .05; data not shown).

Table 2 shows estimated associations of klotho with SPPB summary and component scores. Higher klotho was associated with higher average SPPB summary, balance, chair stand, and walk scores after adjustment for age, sex, and visit (Model 1). After additional covariate adjustment (Model 2), each ln(klotho) was associated with 0.47 point higher average SPPB summary scores (beta estimate = 0.49, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.08 to 0.86, p value = .02). We also found statistically significant positive associations of ln(klotho) with balance (beta estimate = 0.21, 95% CI: 0.02 to 0.39, p value = .03) and walk scores (beta estimate = 0.16, 95% CI: 0.03 to 0.29, p value = .01). The estimate for chair stand scores was also positive, but not statistically significant (beta estimate = 0.11, 95% CI: −0.02 to 0.23, p value = .11). All estimates changed little after adjustment for PTH and PTH-by-ln[25(OH)D] interaction (Model 3).

Table 2.

Associations of ln(klotho) With SPPB Scores Among InCHIANTI Participants Aged ≥55 y

| SPPB Outcome | Model | Beta Estimate* | 95% Confidence Interval | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Summary | Model 1 | 0.63 | (0.07, 1.20) | .03 |

| Model 2 | 0.47 | (0.08, 0.86) | .02 | |

| Model 3 | 0.51 | (0.11, 0.91) | .01 | |

| Balance | Model 1 | 0.29 | (0.05, 0.53) | .02 |

| Model 2 | 0.21 | (0.02, 0.39) | .03 | |

| Model 3 | 0.22 | (0.04, 0.41) | .02 | |

| Chair stand | Model 1 | 0.17 | (0.01, 0.33) | .04 |

| Model 2 | 0.11 | (−0.02, 0.23) | .11 | |

| Model 3 | 0.11 | (−0.02, 0.25) | .09 | |

| Walk | Model 1 | 0.20 | (0.03, 0.36) | .02 |

| Model 2 | 0.16 | (0.03, 0.29) | .01 | |

| Model 3 | 0.17 | (0.04, 0.30) | .01 |

Notes: Model 1: adjustment for visit, age, sex, and visit-by-age interaction.

Model 2: additional adjustment for ln[25(OH)D], eGFR, calcium intake, alcohol consumption, smoking, body mass index (continuous and quadratic terms), MMSE, years of education, physical activity level, history of falls, and comorbid conditions (hypertension, congestive heart failure, peripheral arterial disease, stroke, diabetes, cancer, renal disease, and osteoporosis).

Model 3: additional adjustment for PTH and PTH-by-ln[25(OH)D] interaction. 25(OH)D = 25-hydroxyvitamin D; eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate; InCHIANTI = Invecchiare in Chianti, “Aging in Chianti”; MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination; PTH = parathyroid hormone; SPPB = Short Physical Performance Battery.

*Mean difference in SPPB summary and component scores per ln(klotho) in pg/mL.

Table 3 presents findings from mediation analyses. Estimated total effects of ln[25(OH)D] on SPPB and component scores were all positive and statistically significant (all p value ≤ .001). Estimates of ln[25(OH)D] total effects and effects unmediated by ln[klotho] (i.e., direct effects) estimated by Mediation Models 1 and 2 were nearly identical. For example, after adjustment for covariates, each ln[25(OH)D] was associated with 0.61 point higher average SPPB summary scores (beta estimate = 0.61, 95% CI: 0.35 to 0.88, p value < .001); Mediation Models 1 and 2 estimated effects unmediated by klotho to be 0.61 (95% CI: 0.34 to 0.87, p value < .001) and 0.63 (95% CI: 0.36 to 0.90; p value < .001), respectively.

Table 3.

Mediation Analysis of ln[25(OH)D] and SPPB Scores by ln[klotho] Among InCHIANTI Participants Aged ≥55 y

| SPPB Outcome | ln[25(OH)D] Effect and Model | Beta Estimate* | 95% Confidence Interval | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Summary | Total | 0.61 | (0.35, 0.88) | <.001 |

| Direct (unmediated by klotho): Mediation Model 1 | 0.61 | (0.34, 0.87) | <.001 | |

| Mediation Model 2 | 0.63 | (0.36, 0.90) | <.001 | |

| Balance | Total | 0.29 | (0.17, 0.42) | <.001 |

| Direct (unmediated by klotho): Mediation Model 1 | 0.29 | (0.16, 0.42) | <.001 | |

| Mediation Model 2 | 0.30 | (0.17, 0.43) | <.001 | |

| Chair stand | Total | 0.15 | (0.06, 0.24) | .001 |

| Direct (unmediated by klotho): Mediation Model 1 | 0.15 | (0.06, 0.24) | .001 | |

| Mediation Model 2 | 0.15 | (0.06, 0.25) | .001 | |

| Walk | Total | 0.17 | (0.09, 0.25) | <.001 |

| Direct (unmediated by klotho): Mediation Model 1 | 0.17 | (0.09, 0.25) | <.001 | |

| Mediation Model 2 | 0.18 | (0.10, 0.26) | <.001 |

Notes: Total effect: adjustment for study visit, age, sex, visit-by-age interaction, eGFR, calcium intake, alcohol consumption, smoking, body mass index (continuous and quadratic terms), MMSE, years of education, physical activity level, history of falls, comorbid conditions (hypertension, congestive heart failure, peripheral arterial disease, stroke, diabetes, cancer, renal disease, and osteoporosis), and season of blood collection.

Mediation Model 1: additionally included ln(klotho).

Mediation Model 2: additional adjustment for PTH using weighting (see Supplementary Material). 25(OH)D = 25-hydroxyvitamin D; eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate; InCHIANTI = Invecchiare in Chianti, “Aging in Chianti”; MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination; PTH = parathyroid hormone; SPPB = Short Physical Performance Battery.

*Mean difference in SPPB summary and component scores per ln[25(OH)D] in ng/mL.

Discussion

This study found that plasma klotho concentrations are positively associated with lower-extremity physical performance, after adjustment for 25(OH)D and other confounders. These findings are consistent with the interpretation of klotho as an “anti-aging” hormone demonstrated in studies in mice (3–5,7,14,24,29–32) and in humans (8–11).

We found no evidence that klotho mediates the association of 25(OH)D with lower-extremity physical performance, because estimated total effects were negligibly different from estimated direct effects unmediated by klotho. One possibility is that klotho and 25(OH)D may affect performance through different mechanisms. Mediation analysis was motivated by mechanistic roles that klotho plays in mineral homeostasis and regulation of 1,25(OH)D2, and by reports of associations between klotho genetic variants and bone mineral density (33–36). However, klotho may impact physical performance through other mechanisms. First, klotho regulates growth factor signaling (3), such as inhibition of the insulin/insulin-like growth factor-1 signaling pathway (5,30), which positively relates to health in older adults (37). Second, klotho helps to maintain endothelial function (3), which protects against atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease. Third, klotho regulates ion channels in the kidney (3) responsible for increasing calcium reabsorption and potassium excretion (29,38). Lastly, klotho suppresses oxidative stress by inhibiting insulin/insulin-like growth factor-1 signaling pathway and upregulating antioxidant enzymes (32).

This study had multiple strengths including a large longitudinal cohort, multiple biomarkers and other covariates, rigorous mediation analysis (including sensitivity analyses that address uncertainty about regulation between PTH and klotho), and rigorous handling of missing data and selective survival. Furthermore, the mediation analysis supports and extends previous work on 25(OH)D and lower-extremity physical performance in InCHIANTI (17) by using repeated SPPB measures.

Despite these strengths, some limitations must be acknowledged. First, biomarker concentrations were measured once, possibly with error. However, if error is unsystematic, then estimates may be conservative. Second, there were missing data due to nonresponse and mortality, but we attempted to reduce potential bias using modern statistical methods (27). Furthermore, the study would have benefited from measured phosphate concentrations, which were not available in InCHIANTI, given the role of klotho in phosphate regulation. Lastly, as in any observational study, there is potential for unmeasured confounding. We selected confounders based on current scientific knowledge about klotho and included relevant interaction terms to mitigate this possibility.

Future research on klotho can help to identify novel targets to be investigated in longitudinal studies of older adults. Also, assessing klotho concentrations as a secondary outcome in vitamin D supplementation trials may help determine whether klotho can be modified by vitamin D among vitamin D-deficient older adults. In the meantime, this and previous work in humans (8–11) and mice (3–5,7,14,24,29–32) provide an impetus for examining the role of klotho in health and aging, including whether klotho relates prospectively to other important conditions in older adults such as pain (39), sarcopenia (19), and frailty (40).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material can be found at: http://biomedgerontology.oxfordjournals.org/

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants (R01AG027012 and R01HL094507 to R.D.S., K23DK093583 to R.R.K., R01AG041202 to G.E.H.); the Italian Ministry of Health (ICS110.1/RF97.71); National Institute on Aging contracts (263 MD 9164, 263 MD 821336, N.1-AG-1-1, N.1-AG-1-2111, N01-AG-5-0002); and the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Pieper CF, et al. Lower extremity function and subsequent disability: consistency across studies, predictive models, and value of gait speed alone compared with the short physical performance battery. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55:M221–M231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Studenski S, Perera S, Patel K, et al. Gait speed and survival in older adults. JAMA. 2011;305:50–58. :10.1001/jama.2010.1923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kuro-o M. Klotho. Pflugers Archiv: Eur J Physiol. 2010;459:333–343. :10.1007/s00424-009-0722-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kuro-o M, Matsumura Y, Aizawa H, et al. Mutation of the mouse klotho gene leads to a syndrome resembling ageing. Nature. 1997;390:45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kurosu H, Yamamoto M, Clark JD, et al. Suppression of aging in mice by the hormone Klotho. Science. 2005;309:1829–1833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ito S, Kinoshita S, Shiraishi N, et al. Molecular cloning and expression analyses of mouse betaklotho, which encodes a novel Klotho family protein. Mech Dev. 2000;98:115–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Urakawa I, Yamazaki Y, Shimada T, et al. Klotho converts canonical FGF receptor into a specific receptor for FGF23. Nature. 2006;444:770–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Semba RD, Cappola AR, Sun K, et al. Plasma klotho and mortality risk in older community-dwelling adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011;66:794–800. :10.1093/gerona/glr058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Semba RD, Cappola AR, Sun K, et al. Relationship of low plasma klotho with poor grip strength in older community-dwelling adults: the InCHIANTI study. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2012;112:1215–1220. :10.1007/s00421-011-2072-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Crasto CL, Semba RD, Sun K, Cappola AR, Bandinelli S, Ferrucci L. Relationship of low-circulating "anti-aging" klotho hormone with disability in activities of daily living among older community-dwelling adults. Rejuvenation Res. 2012;15:295–301. :10.1089/rej.2011.1268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Semba RD, Cappola AR, Sun K, et al. Plasma klotho and cardiovascular disease in adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:1596–1601. :10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03558.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lips P. Vitamin D physiology. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2006;92:4–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Haussler MR, Whitfield GK, Kaneko I, et al. Molecular mechanisms of vitamin D action. Calcif Tissue Int. 2013;92:77–98. :10.1007/s00223-012-9619-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Forster RE, Jurutka PW, Hsieh JC, et al. Vitamin D receptor controls expression of the anti-aging klotho gene in mouse and human renal cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;414:557–562. :10.1016/ j.bbrc.2011.09.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Martin A, David V, Quarles LD. Regulation and function of the FGF23/klotho endocrine pathways. Physiol Rev. 2012;92:131–155. :10.1152/physrev.00002.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dam TT, von Mühlen D, Barrett-Connor EL. Sex-specific association of serum vitamin D levels with physical function in older adults. Osteoporos Int. 2009;20:751–760. :10.1007/s00198-008-0749-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Houston DK, Cesari M, Ferrucci L, et al. Association between vitamin D status and physical performance: the InCHIANTI study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62:440–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Houston DK, Tooze JA, Davis CC, et al. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and physical function in older adults: the Cardiovascular Health Study All Stars. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:1793–1801. :10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03601.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Visser M, Deeg DJ, Lips P; Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam. Low vitamin D and high parathyroid hormone levels as determinants of loss of muscle strength and muscle mass (sarcopenia): the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:5766–5772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hirani V, Cumming RG, Naganathan V, et al. Associations between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations and multiple health conditions, physical performance measures, disability, and all-cause mortality: the Concord Health and Ageing in Men Project. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:417–425. :10.1111/jgs.12693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ferrucci L, Bandinelli S, Benvenuti E, et al. Subsystems contributing to the decline in ability to walk: bridging the gap between epidemiology and geriatric practice in the InCHIANTI study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:1618–1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, et al. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Gerontol. 1994;49:M85–M94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yamazaki Y, Imura A, Urakawa I, et al. Establishment of sandwich ELISA for soluble alpha-Klotho measurement: age-dependent change of soluble alpha-Klotho levels in healthy subjects. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;398:513–518. :10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.06.110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Imura A, Tsuji Y, Murata M, et al. alpha-Klotho as a regulator of calcium homeostasis. Science. 2007;316:1615–1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. ; CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration). A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:604–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Greenland S, Pearl J, Robins JM. Causal diagrams for epidemiologic research. Epidemiology. 1999;10:37–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shardell M, Hicks GE, Ferrucci L. Doubly robust estimation and causal inference in longitudinal studies with dropout and truncation by death. Biostatistics. 2015;16:155–168. :10.1093/biostatistics/kxu032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. VanderWeele TJ. Marginal structural models for the estimation of direct and indirect effects. Epidemiology. 2009;20:18–26. :10.1097/EDE.0b013e31818f69ce [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chang Q, Hoefs S, van der Kemp AW, Topala CN, Bindels RJ, Hoenderop JG. The beta-glucuronidase klotho hydrolyzes and activates the TRPV5 channel. Science. 2005;310:490–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Utsugi T, Ohno T, Ohyama Y, et al. Decreased insulin production and increased insulin sensitivity in the klotho mutant mouse, a novel animal model for human aging. Metabolism. 2000;49:1118–1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hu MC, Shi M, Zhang J, et al. Klotho: a novel phosphaturic substance acting as an autocrine enzyme in the renal proximal tubule. FASEB J. 2010;24:3438–3450. :10.1096/fj.10-154765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yamamoto M, Clark JD, Pastor JV, et al. Regulation of oxidative stress by the anti-aging hormone klotho. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:38029–38034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kawano K, Ogata N, Chiano M, et al. Klotho gene polymorphisms associated with bone density of aged postmenopausal women. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17:1744–1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ogata N, Matsumura Y, Shiraki M, et al. Association of klotho gene polymorphism with bone density and spondylosis of the lumbar spine in postmenopausal women. Bone. 2002;31:37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Riancho JA, Valero C, Hernández JL, et al. Association of the F352V variant of the Klotho gene with bone mineral density. Biogerontology. 2007;8:121–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yamada Y, Ando F, Niino N, Shimokata H. Association of polymorphisms of the androgen receptor and klotho genes with bone mineral density in Japanese women. J Mol Med (Berl). 2005;83:50–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tatar M, Bartke A, Antebi A. The endocrine regulation of aging by insulin-like signals. Science. 2003;299:1346–1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cha SK, Hu MC, Kurosu H, Kuro-o M, Moe O, Huang CL. Regulation of renal outer medullary potassium channel and renal K(+) excretion by Klotho. Mol Pharmacol. 2009;76:38–46. :10.1124/mol.109.055780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hicks GE, Shardell M, Miller RR, et al. Associations between vitamin D status and pain in older adults: the Invecchiare in Chianti study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:785–791. :10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01644.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Shardell M, D'Adamo C, Alley DE, et al. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D, transitions between frailty states, and mortality in older adults: the Invecchiare in Chianti Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:256–264. :10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03830.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.