Abstract

Tuberculosis (TB) is a well-known endemic in developing countries. However calvarial TB is quiet rare even in such endemic areas. The most common sites affected are the frontal and parietal bones with destruction of both the inner and outer table. We hereby report a young male presenting to us with scalp swelling in the right temporal region with pus discharging sinus after an episode of tooth extraction for dental infection. Radiology revealed a loculated swelling within the right temporalis muscle and an associated bony defect in the right parietal bone. The patient was operated upon and the biopsy was suggestive of tubercular pathology. The patient improved on antitubercular therapy. The rare presentation of calvarial TB occurring secondary to dental infection along with relevant literature is discussed here.

Keywords: Calvarial, hematogenous, pulmonary, tuberculosis

Introduction

Reid first reported calvarial tuberculosis (TB) in 1842. Cranial and epidural TB are infrequent manifestations of extrapulmonary TB.[1] There have been isolated reports of calvarial TB due to direct extension from a nearby focus of infection.[2] About 75-90% of patients suffering from calvarial TB come under the age group of 20-30 years.[3,4] It usually involves the frontal and parietal bones due to the greater amount of cancellous bone with diploic channels in these bones.[5,6] It usually begins in the diploic space and affects the inner and outer table equally. If the outer table is affected they present as subgaleal swelling with discharging sinuses. On the other hand if the inner table is affected by and large, it leads to deposition of extradural granulation tissue. This extradural granulation tissue may increase in size and cause neurological deficits depending on its magnitude. The diagnosis relies upon a good clinical acumen and timely radiological investigations. X-ray and computed tomography (CT) head reveals punched out lesions in the frontal and parietal bones. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may show the presence of adjacent soft-tissue changes in the form of abscesses or intramuscular collections. Isolation of the bacilli is quiet diagnostic, which is not possible many a time. Surgery and anti-tubercular therapy are the mainstay of treatment. We are reporting a case of calvarial TB on account of its rarity and difficulty in diagnosis.

Case Report

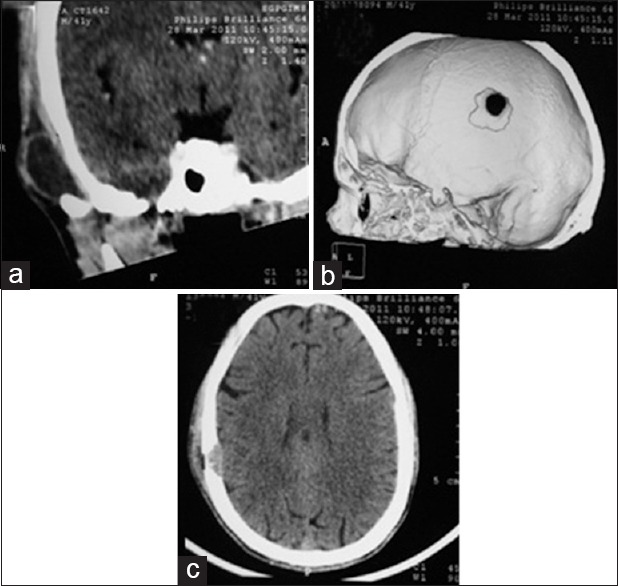

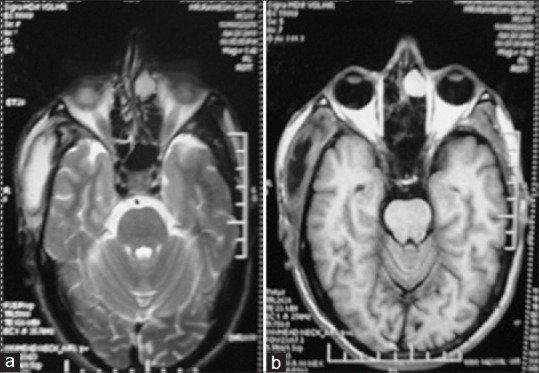

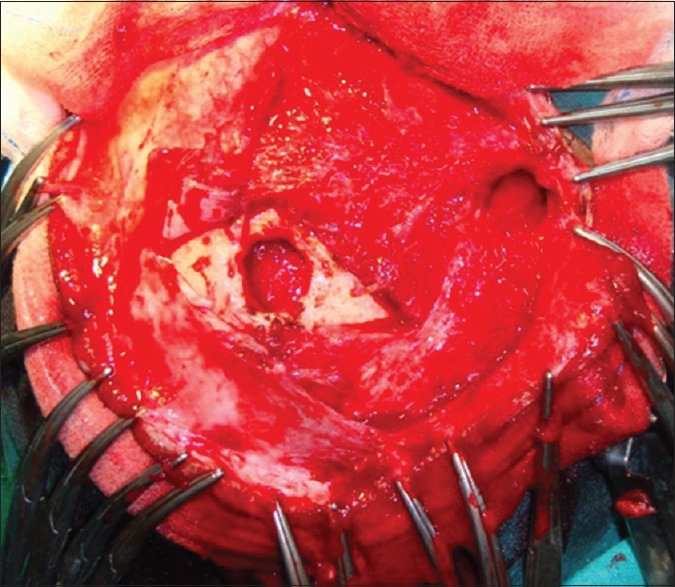

The present case report is about a 40-year-old male patient presented with the complaints of swelling in the right temporal region for 4 months. On detailed evaluation, he gave a history of dental infection leading to tooth extraction following which the swelling started. In addition, he also complained of holocranial headache of 15 days duration. On examination, the swelling was 3 × 3 × 4 cm in size and was non pulsatile, soft and fluctuant with ill-defined and diffuse borders. A small defect was palpable in the right parietal bone posterior to the swelling. At 24 h after admission, he developed sinuses over the swelling that were discharging pus. CT head revealed a defect of size 2 × 2 cm in the right parietal bone with irregular margins and the defect was involving both the inner and outer tables. The bony edge was undermined with an extradural collection of size 0.5 × 0.5 cm [Figure 1a and b]. There was a collection within the right temporal muscle that was extending down into the infrazygomatic region suggestive of an abscess [Figure 1c]. MRI revealed a T1 hypo T2 hyperintense well defined lesion situated within the right temporalis muscle and an extradural heterointense lesion below the bony defect [Figure 2a and b]. However there was no evidence of intracranial extension. Bone scan of the patient was done and showed increased uptake in the right parietal bone suggestive of osteomyelitis. However as it could be either pyogenic or tubercular in etiology, a detailed evaluation for TB was undertaken. His chest X-ray showed a well-defined opacity in the right upper lobe. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 60 mm at the end of 1st h and Mantoux was positive. TB interferon gamma was done and was positive. Since he had a discharging sinus and a temporal collection he was posted for surgery. A right sided reverse question mark incision was made exposing the temporalis muscle and the defect in the right parietal bone. A large portion of the temporalis muscle was replaced by necrosed tissue and pus [Figure 3]. The pus was extending inferiorly to involve the temporalis muscle below the zygoma. Thorough debridement of the devitalized tissue was done. The defect in the parietal bone was nibbled all around and sent for histopathological examination. There was granulation tissue located extradurally just beneath the defect. It was scooped out and sent for biopsy. After debridement, saline and betadine irrigation was done and the wound closed. Patient was started on antitubercular therapy with isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide and streptomycin as he was not receiving any antibiotics prior to surgery. Microscopy was negative for Grams staining and cultures were sterile. Histopathology report came as caseating granulomas with epitheloid cells, Langhans giant cells with acid fast bacilli seen. Post-operative period was uneventful. Sutures were removed on the 7th post-operative day and patient was discharged. At a follow-up of 4 weeks, patient has no swelling and the wound is well-healed.

Figure 1.

(a) Coronal computed tomography scan showing collection in the right temporalis muscle (b) 2D reconstructed films showing the defect in the right parietal bone (c) Axial computed tomography film showing the defect in the outer and inner table with extradural collection

Figure 2a and b.

Magnetic resonance imaging T2-WI showing T2 hyper intensity within the temporalis muscle that is hypo on T1-WI

Figure 3.

Intra-operative defect seen in the right parietal bone with sloughed off temporalis muscle with the abscess extending below the zygoma

Discussion

TB continues to be one of the greatest health problems in developing countries. Calvarial TB constitutes amongst a rare disorder even amongst the communities with high incidence of TB. It constitutes 0.1-3.7% of the skeletal TB.[7] Most cases are secondary to pulmonary TB, however direct spread from paranasal sinuses and mastoid air cells have been reported. Absence of lymphatic spread from a primary focus accounts for the rarity of calvarial TB as the skull is devoid of lymphatics.[8] After their colonization in the cancellous and diploic spaces of the skull, further development depends on the virulence of the organism and host resistance. The infection causes capillary obliteration and replacement of bony trabeculae by granulation tissue proliferating fibroblasts.[9] The outer table is destroyed first, though eventually both the tables are affected. Duramater is highly resistant to their invasion and hence most of the lesions are found extradurally. However calvarial TB with intradural involvement is occasionally observed in the form of subdural empyema, meningitis or tuberculomas. In our patient, the temporal sequence of events is largely speculative as no histopathology or antimicrobial culture report of the extracted tooth was available to substantiate our assumption. However this assumption was based on the fact that skull osteomyelitis from an odontogenic source is not infrequent in clinical practice. The dental infection probably spread hematogenously to the intradiploic space of the calvaria (of note, there is an abundance of red marrow in the frontal and parietal bone). Growth of tubercle bacilli probably led to destruction of both the tables of the bone. We believe the pus preferentially collected beneath the temporalis muscle because the resistance is probably lower there compared to the epidural space where the toughness of the dura along with its adherence to the under surface of the bone would naturally prevent any significant epidural collection.

The common age group affected is between 10 and 20 years.[10] This was different in our case where the age was forty. The most common presentation is a painless scalp swelling or a discharging sinus in the scalp. When the inner table is affected there is excessive deposition of granulation tissue in the extradural space. This if excessive in amount can present as neurological deficits or seizures.

Depending on the nature of calvarial destruction there are three types of tubercular osteitis.[11] ‘Circumscribed lytic lesions’ are small punched out lesions with granulation tissue covering both the inner and outer tables of the calvaria. It is associated with little tendency to spread and there is no associated periosteal reaction. “Diffuse TB of the cranium” was the term used by Konig for lesions causing widespread destruction of the inner table of the skull. When these lesions are associated with extradural granulation tissue they are referred to as “spreading type”. Our case was of circumscribed lytic type. The mode of infection in our patient was probably through the dental space and then into the temporalis muscle. This was a site for colonization of the mycobacterium TB organisms, which eventually lead to the formation of an abscess.

Detection of acid fast bacilli in pus smear by Ziehl-Nielsen staining or isolation by culture is diagnostic.[12] Multiple epitheloid granulomas with Langerhans type giant cells are seen with necrotic material. A positive Mantoux and raised ESR provide clues for the diagnosis of TB. In our patient, microscopy did not yield any positive finding, however Mantoux, ESR and gamma interferon were helpful.

Plain X-ray of the skull can be helpful. Rarefaction is seen early in the disease that may later develop into punched out lesions. CT scan reveals involvement of outer and inner tables with extradural collection and as in our case presence of associated abscesses in the surrounding areas. However soft-tissue involvement is better delineated on MRI.

Treatment of calvarial TB includes surgery and antitubercular therapy.[13] Surgery is indicated for drainage of abscesses, to establish the diagnosis and in larger lesions causing mass effect and neurological deficits.[14] Antitubercular therapy should be continued for a period of 18 months and the patient should be monitored serially for response to antitubercular therapy. This is done by clinical examinations, ESR and CT scanning. Radiological evidence of healing is evident by 2 months of start of antitubercular therapy.[15] It is manifested by the appearance of new bone formation at the edges of the lesion.

Calvarial TB is a rare manifestation of an endemic disease-TB that we deal in our day-to-day life. Though the usual age group is 10-20 years, our patient belonged to the fourth decade. Trauma is usually the inclinating factor involved in the pathogenesis of calvarial TB. Though rare they may manifest as pus discharging sinus and abscess formation in temporalis muscles. The skull defect may ensue with extradural granulation tissue. Common radiological findings include punched out lesions in the scalp associated with extradural collections. Patients usually respond well to antitubercular therapy and surgical drainage if necessary. With good clinical acumen, radiological findings and prompt treatment, most of these patients respond well.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Strauss DC. Tuberculsis of the flat bones of vault of the skull. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1993;57:384–98. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barton CJ. Tubercolosis of the vault of the skull. Br J Radiol. 1961;34:286–90. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-34-401-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jadhav RN, Palande DA. Calvarial tuberculosis. Neurosurgery. 1999;45:1345–9. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199912000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raut AA, Nagar AM, Muzumdar D, Chawla AJ, Narlawar RS, Fattepurkar S, et al. Imaging features of calvarial tuberculosis: A study of 42 cases. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2004;25:409–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sundaram PK, Sayed F. Superior sagittal sinus thrombosis caused by calvarial tuberculosis: Case report. Neurosurgery. 2007;60:E776. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000255402.53774.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Pape AJ. Multiple pseudo-cystic tuberculosis of bone; report of a case. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1954;36-B:637–41. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.36B4.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gupta PK, Kolluri VR, Chandramouli BA, Venkataramana NK, Das BS. Calvarial tuberculosis: A report of two cases. Neurosurgery. 1989;25:830–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rudman IE. Tuberculosis of the bones of the skull. Med Times. 1965;93:910–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malhotra R, Dinda AK, Bhan S. Tubercular osteitis of skull. Indian Pediatr. 1993;30:1119–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.LeRoux PD, Griffin GE, Marsh HT, Winn HR. Tuberculosis of the skull – A rare condition: Case report and review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 1990;26:851–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miles J, Hughes B. Tuberculous osteitis of the skull. Br J Surg. 1970;57:673–9. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800570911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rajmohan BP, Anto D, Alappat JP. Calvarial tuberculosis. Neurol India. 2004;52:278–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prinsloo JG, Kirsten GF. Tuberculosis of the skull vault: A case report. S Afr Med J. 1977;51:248–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shahat AH, Rahman NU, Obaideen AM, Ahmed I, Zahman Au Au. Cranial-epidural tuberculosis presenting as a scalp swelling. Surg Neurol. 2004;61:464–6. doi: 10.1016/S0090-3019(03)00486-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allison JW, Abernathy RS, Figarola MS, Tonkin IL. Pediatric case of the day. Tuberculous osteomyelitis with skull involvement and epidural abscess. Radiographics. 1999;19:552–4. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.19.2.g99mr20552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]