Significance

Levels of CC chemokine receptor 5 (CCR5) on T cells are a critical factor influencing HIV/AIDS susceptibility. DNA methylation is an epigenetic feature associated with lower gene expression. Here we show that the DNA methylation status of CCR5 cis-regulatory regions (cis-regions) correlates inversely with CCR5 levels on T cells. T-cell activation induces demethylation of CCR5 cis-regions, upregulating CCR5 expression. Higher vs. lower sensitivity of CCR5 cis-regions to undergoing T-cell activation-induced demethylation is associated with increased vs. decreased CCR5 levels. Polymorphisms in CCR5 cis-regions that are associated with increased vs. decreased HIV/AIDS susceptibility are also associated with increased vs. decreased sensitivity to activation-induced demethylation. Thus, interactions among T-cell activation, CCR5 epigenetics, and genetics influence CCR5 levels on T cells and, by extension, HIV/AIDS susceptibility.

Keywords: HIV, CCR5, methylation, T-cell activation, polymorphism

Abstract

T-cell expression levels of CC chemokine receptor 5 (CCR5) are a critical determinant of HIV/AIDS susceptibility, and manifest wide variations (i) between T-cell subsets and among individuals and (ii) in T-cell activation-induced increases in expression levels. We demonstrate that a unifying mechanism for this variation is differences in constitutive and T-cell activation-induced DNA methylation status of CCR5 cis-regulatory regions (cis-regions). Commencing at an evolutionarily conserved CpG (CpG −41), CCR5 cis-regions manifest lower vs. higher methylation in T cells with higher vs. lower CCR5 levels (memory vs. naïve T cells) and in memory T cells with higher vs. lower CCR5 levels. HIV-related and in vitro induced T-cell activation is associated with demethylation of these cis-regions. CCR5 haplotypes associated with increased vs. decreased gene/surface expression levels and HIV/AIDS susceptibility magnify vs. dampen T-cell activation-associated demethylation. Methylation status of CCR5 intron 2 explains a larger proportion of the variation in CCR5 levels than genotype or T-cell activation. The ancestral, protective CCR5-HHA haplotype bears a polymorphism at CpG −41 that is (i) specific to southern Africa, (ii) abrogates binding of the transcription factor CREB1 to this cis-region, and (iii) exhibits a trend for overrepresentation in persons with reduced susceptibility to HIV and disease progression. Genotypes lacking the CCR5-Δ32 mutation but with hypermethylated cis-regions have CCR5 levels similar to genotypes heterozygous for CCR5-Δ32. In HIV-infected individuals, CCR5 cis-regions remain demethylated, despite restoration of CD4+ counts (≥800 cells per mm3) with antiretroviral therapy. Thus, methylation content of CCR5 cis-regions is a central epigenetic determinant of T-cell CCR5 levels, and possibly HIV-related outcomes.

CC chemokine receptor 5 (CCR5) is the major coreceptor for T-cell entry of HIV-1 (1). CCR5 levels on T cells influence HIV acquisition, disease progression rates, viral load, and immune recovery during antiretroviral therapy (ART), among other traits (1–4) (discussed in ref. 5). In these instances, lower CCR5 levels correlate with beneficial outcomes. Polymorphisms in the ORF and cis-regulatory regions (cis-regions) of CCR5 that correlate with higher vs. lower surface and/or gene expression levels are associated with increased vs. decreased HIV/AIDS risk and immune recovery (4–12). Classic examples are homozygosity and heterozygosity of the 32-bp deletion in the CCR5 ORF (CCR5-Δ32), which are associated with complete and reduced CCR5 levels, respectively (4, 12).

However, polymorphisms are unlikely to unify the four key features of T-cell CCR5 expression. (i) CCR5 levels vary widely on T-cell subsets. The differentiation state of T cells influences CCR5 levels. Expression is higher on memory compared with naïve T cells (13, 14). Among memory T cells, expression is higher on effector compared with central memory T cells (13, 14). (ii) There is wide interindividual variation in CCR5 levels that cannot be fully explained by polymorphisms. CCR5 levels differ by up to 20-fold on T cells and, paradoxically, many individuals without CCR5-Δ32 have CCR5 levels similar to CCR5-Δ32 heterozygotes (2, 3, 13). (iii) CCR5 levels are up-regulated in settings associated with increased T-cell activation (henceforth “activation”), such as HIV infection (15). (iv) The degree of activation-associated up-regulation of CCR5 varies significantly among individuals (15).

Although separate mechanisms can be invoked, we sought a unified mechanism for these four features of T-cell expression of CCR5. We conceptualized that epigenetic features such as DNA methylation status of cytidine phosphate guanidine (CpG) dinucleotides in the cis-regions of CCR5 may serve as a unifying mechanism. This thesis would be bolstered if the following four criteria were to be met (models are shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S1). There is a well-established link between higher DNA methylation content in cis-regions and lower gene expression (16). Hence, constitutive inter–T cell-type and interindividual differences in CCR5 levels may relate to constitutive inter–T cell-type (criterion 1) and interindividual (criterion 2) differences, respectively, in DNA methylation content of specific CCR5 cis-regions. Additionally, DNA methylation, in concert with other epigenetic mechanisms (e.g., histone modifications), interfaces between environmental/immune signals and gene expression programs that control T-cell differentiation and effector functions during inflammation (17). Hence, activation-induced up-regulation of CCR5 levels may relate to demethylation of CCR5 cis-regions (criterion 3). Finally, allele-specific methylation influences gene expression and disease outcomes (18). Hence, the well-documented association of CCR5 haplotypes with increased vs. decreased HIV/AIDS susceptibility may relate to their cis-regions manifesting greater vs. lower sensitivity, respectively, to activation-induced demethylation (criterion 4). To test our hypothesis, these criteria were examined using ex vivo and in vitro approaches and multiple study populations (SI Appendix, Materials and Methods).

Results

CCR5 cis-Regions Selected for Methylation Analyses.

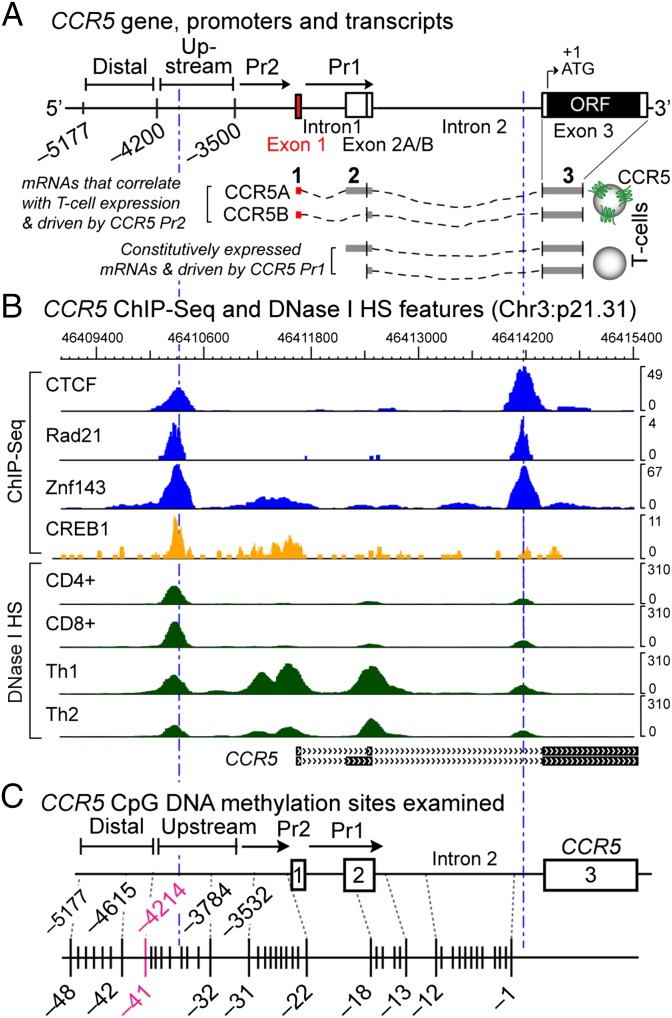

Fig. 1A depicts the nomenclature and numbering system and the three-exon gene structure of CCR5; the CCR5 ORF is in exon 3 (6, 19). We focused on the DNA methylation status of an ∼5.2-kb cis-region between CCR5 −5177 and +1 (Fig. 1A), because this cis-region is influential in regulating gene expression.

Fig. 1.

CCR5 gene, mRNA structure, and transcriptional and DNA methylation landmarks. (A) Three-exon CCR5 gene structure, two promoters, and exon 1-containing (full-length) vs. -lacking (truncated) mRNA isoforms (6). The upstream region starts ∼4.2 kb upstream of the ORF and indicates where increased micrococcal nuclease (Mnase) accessibility is apparent in memory cells compared with naïve cells (6). (B) Wiggle plots depict colocalization of CTCF, cohesin component Rad21, Znf143, and the transcription factor CREB1 (by ChIP-seq in GM12878 lymphoblastoid cells) and DNase I hypersensitivity sites in primary CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and Th1 and Th2 cells; derived from publicly available data. (C) CpG sites examined.

First, two sets of alternatively spliced CCR5 mRNA isoforms are derived from two CCR5 promoters (CCR5-Pr2 and CCR5-Pr1) in this cis-region (Fig. 1A) (6). CCR5-Pr2 drives the production of “full-length” mRNA isoforms that contain the 5′-most exon 1. Exon 1-containing CCR5 transcripts are more abundant in T cells that constitutively express higher compared with lower CCR5 levels (e.g., memory vs. naïve T cells, respectively) (19). In contrast, CCR5-Pr1 drives the production of “truncated” transcripts that lack exon 1; these mRNA isoforms are constitutively expressed in both naïve and memory T cells (19). Second, regions 5′ of CCR5-Pr2 and 3′ of CCR5-Pr1 also influence CCR5 gene expression (6, 19–21). Third, ChIP-seq (chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing) for factors such as CCCTC-binding factor (CTCF), cohesin, Rad21, and Znf143—all known to influence gene expression through insulator function and 3D chromatin organization (22)—reveals two sharp coincident enrichment peaks in this region (Fig. 1B). This cis-region is also enriched for transcription factors such as CREB1 (cAMP responsive element binding protein 1) that influence CCR5 regulation (20) (Fig. 1B). Two DNase I hypersensitivity sites (HSs) are coincident with the CTCF peaks; the other HSs were near CCR5-Pr2 and CCR5-Pr1 (Fig. 1B). The HS in CCR5-Pr2 is more prominent in Th1 cells, which have higher CCR5 levels than Th2 cells (23) (Fig. 1B), substantiating the idea that a transcriptionally active CCR5-Pr2 may correlate with higher CCR5 levels on T cells.

Inter–T Cell-Type Differences in DNA Methylation Patterns.

To test for criterion 1, we determined the methylation content of 48 CpGs in this ∼5.2-kb cis-region by bisulfite genomic sequencing of overlapping gene segments and pyrosequencing of representative CpGs in the upstream (CpGs −41 to −37), CCR5-Pr2 (CpGs −31 to −28), and intron 2 (CpGs −6 to −2) cis-regions (Fig. 1C and SI Appendix, Table S1). Because of polymorphisms, some CCR5 haplotypes have additional CpGs (SI Appendix, Table S1). We compared the methylation content of CD45RO− vs. CD45RO+, or CD45RA+ vs. CD45RA− T cells derived from HIV-negative donors before and after accounting for whether the sorted T-cell subsets did vs. did not express CCR5 (CCR5+ vs. CCR5−), CD45RO−, or CD45RA+, and CD45RO+ and CD45RA− are surface markers representative of naïve and memory T cells, respectively; CCR5+ CD45RO− and CCR5+ CD45RA+ T cells are markers representative of terminally differentiated effector memory T cells (TEMRA) (24).

In CD45RO− T cells, CpGs −1 to −31 were mostly methylated, except for those near CCR5-Pr1 (Fig. 2A). In contrast, in CD45RO+ T cells, these CpGs were extensively hypomethylated, except in intron 2 (Fig. 2B). CpGs in the CCR5-Pr1 core region (−17 to −14) were constitutively hypomethylated in CD45RO+ and CD45RO− T cells (Fig. 2 A and B), suggesting that this epigenetic feature may underlie the constitutive production of exon 1-containing, CCR5-Pr1–driven mRNAs in T cells. Two observations substantiate this idea. (i) The Jurkat T-cell line lacks surface CCR5 expression and transcribes only exon 1-lacking CCR5 mRNA (13, 19) and, except for CpGs in the core region of CCR5-Pr1, the remaining cis-regions are heavily methylated (SI Appendix, Fig. S2A, Left). This methylation pattern agrees with the report by Wierda et al. (25). (ii) In contrast, oral epithelial cells express very low CCR5 mRNA and surface levels, and the CpGs in the core of CCR5-Pr1 in these cells are heavily methylated (Fig. 2C).

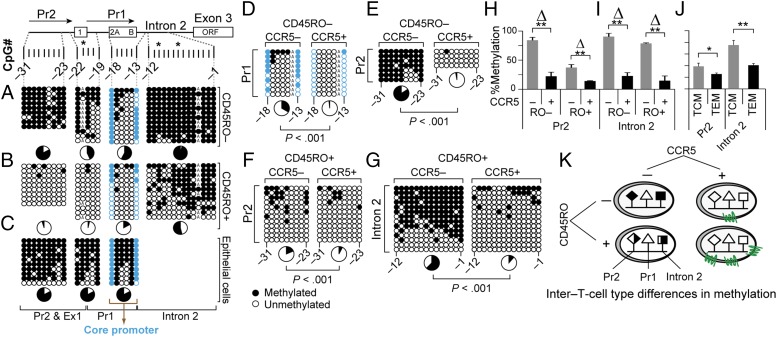

Fig. 2.

Distribution of DNA methylation content in CCR5-Pr2, -Pr1, and -intron 2 in T-cell subsets. (A–G) Methylation content of the indicated CpGs derived by bisulfite genomic sequencing (BGS) in (A) CD3+CD4+CD45RO− T cells; (B) CD3+CD4+CD45RO+ T cells; (C) oral epithelial cells; and (D–G) CCR5− or CCR5+ CD3+CD45RO− and CD3+CD45RO+ T cells. Each column represents the CpG site interrogated, and each row represents a single clone. Closed and open circles represent methylated and unmethylated CpG sites, respectively. The asterisks indicate a haplotype-specific polymorphism; CpG −4 is disrupted in one allele due to a private polymorphism in the donor shown in A and B. Pie charts, % methylation; CpGs −18 and −13 (blue) encompass a core of constitutively demethylated CpGs within CCR5-Pr1 in T cells. (H–J) Methylation content assessed by pyrosequencing of four representative CpGs located within (H) CCR5-Pr2 (CpG −31 to −28) and (I) intron 2 (CpG −5 to −2) in cell-sorted CCR5+ and CCR5− CD3+ T cells and (J) central memory (TCM; CD45RA−CD45RO+CCR7+) and effector memory (TEM; CD45RA−CD45RO+CCR7−) T cells. The pyrosequencing data are depicted as mean percentage methylation and error bars depict the standard error of the mean (SEM). Data are from three donors. **P < 0.01 and *P < 0.05, small vs. larger Δ, relative difference in methylation content. (K) Schema depicting the relative methylation content of CCR5-Pr2 and CCR5-intron 2 in cell-sorted CCR5-positive and CCR5-negative CD45RO+ and CD45RO− T cells, supporting criterion 1.

The methylation content of CpGs −31 to −1 was consistently lower in CCR5+ compared with CCR5− CD45RO− or CD45RO+ T cells (Fig. 2 D–I). However, in support of criterion 1, CCR5+ and CCR5− T-cell subsets exhibited a specific spatial distribution of methylation content in this cis-region (Fig. 2 E–I) and in T cells that naturally express higher vs. lower CCR5 (e.g., effector vs. central memory T cells; Fig. 2J). This distribution pattern is summarized in Fig. 2K. The methylation content of CCR5-Pr2 differentiated CCR5-expressing vs. -lacking CD45RO− T cells (Fig. 2 E, H, and K), whereas the methylation content of intron 2 differentiated CCR5-expressing vs. -lacking CD45RO+ or CD45RO− T cells (Fig. 2 G, I, and K). Differences in methylation content between T-cell subsets is also observed in publicly available genome-wide DNA methylation datasets; however, T cells were not sorted by CCR5 expression in these studies (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 B and C).

CpG −41 Demarcates Methylation Content.

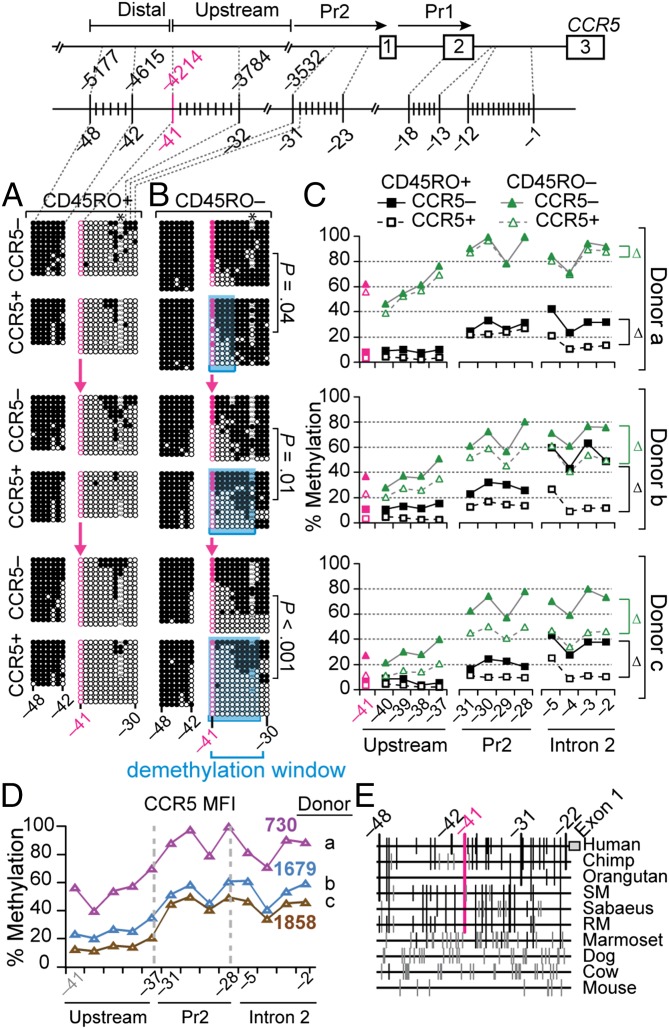

An abrupt transition in methylation status was observed at CpG −41. In CD45RO+ and CD45RO− T cells, CpGs upstream of CpG −41 (−48 to −42) were highly methylated, regardless of CCR5 expression (Fig. 3 A and B). In contrast, CpGs −41 to −30 showed striking differences by the differentiation state of the T cell: extensive hypomethylation in CCR5− or CCR5+ CD45RO+ T cells vs. heavy or moderate methylation in CCR5− and CCR5+ CD45RO− T cells. Methylation levels also differed by CCR5 expression levels. Although the CpGs downstream of CpG −41 were hypomethylated to a greater extent in CCR5+ compared with CCR5− CD45RO+ or CD45RO− T cells, the degree of hypomethylation was greater in T cells with higher compared with lower CCR5 surface levels (Fig. 3 A–D). Also, the length of the demethylation window in CCR5+ CD45RO− T cells correlated with CCR5 surface levels in the three donors (Fig. 3 A and D). CpG −41 is evolutionarily conserved in most nonhuman primates (Fig. 3E), and is in close proximity (∼120 bp) to the signals for CTCF and its interacting partners and DNase I HSs (Fig. 1 B and C).

Fig. 3.

Contrasting distribution of methylation content across an evolutionarily conserved CpG site distinguishes CCR5+ vs. CCR5− CD45RO+ or CD45RO− T cells. (A and B) CpG −41 (indicated in pink) is a transitional boundary from high to low methylation in the CCR5 locus in the indicated T-cell subsets. CpGs −41 and −32 demarcate a variable demethylation window shown in blue in CCR5+CD45RA+CD45RO− T cells, the length of which associates with CCR5 levels. Data are from three independent donors (denoted as donors a–c in C and D). P values, by χ2 for comparisons of the methylation content of CCR5+ vs. CCR5− sorted T cells. Closed and open circles represent methylated and unmethylated CpG sites, respectively. Absence of circles indicates polymorphisms or no data available. The asterisks indicate a polymorphism at CpG −33 in selected clones. The pink arrows indicate CpG −41 that marks the transition in methylation status. (C) Percent methylation (assessed by pyrosequencing) of the indicated CpG sites in the same T-cell subsets shown in A and B. Δ refers to the relative differences of methylation levels between CCR5+ vs. CCR5− CD45RA−CD45RO+ or CD45RA+CD45RO− CD8+ T cells in each of the three cis-regions examined. (D) Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) after sorting of CCR5+CD45RA+CD45RO− CD8+ T cells (same donors as in A–C) and corresponding methylation levels (assessed by pyrosequencing) at the indicated CpG sites. (E) Multispecies alignment of CpG sites upstream of exon 1 in CCR5. Chimp, chimpanzee; RM, rhesus macaque; SM, sooty mangabey. Lines connecting the data points in this figure are provided for better visualization of the data.

Methylation Levels, a Correlate of Interindividual Differences in CCR5 Expression.

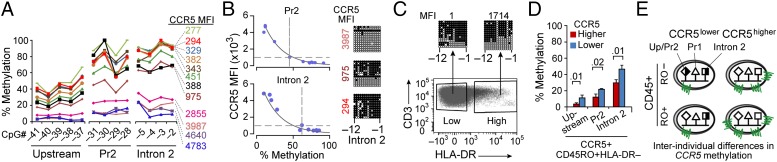

In support of criterion 2, sorted T cells with progressively higher CCR5 levels had incrementally lower methylation content in CCR5 cis-regions (Fig. 4 A and B). This inverse relationship was nonlinear; after reaching a threshold (mean fluorescence intensity of ∼1,000), small reductions in methylation were associated with exponentially higher CCR5 expression (Fig. 4B). However, methylation status was relatively similar in T cells sorted according to whether the levels of the activation marker HLA-DR were high vs. low (Fig. 4C), suggesting that the methylation status of CCR5 cis-regions more closely correlated with CCR5 expression than levels of activation. To substantiate this idea, we investigated methylation status in CD4+ memory T cells obtained from healthy blood donors before and after sorting according to HLA-DR status (negative vs. positive). Irrespective of HLA-DR status, methylation levels were lower in CD4+ memory T cells that constitutively expressed higher compared with lower CCR5 levels (Fig. 4D and SI Appendix, Fig. S3A). Further confirming that methylation status is a strong correlate for surface levels, in healthy donors who constitutively expressed lower vs. higher CCR5 on CD45RA+ (TEMRA) or CD45RO+, T cells had higher vs. lower methylation levels (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 B–D). The association of higher vs. lower methylation status with lower vs. higher expression of CCR5 mRNA and surface expression is shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S3 E–G.

Fig. 4.

Methylation content of CCR5 cis-regulatory regions as a basis for interindividual differences in CCR5 levels on T cells. (A) Methylation content at the indicated CpGs in sorted CCR5+CD3+ T cells obtained from four healthy donors with the indicated postsort levels of CCR5 MFI (four gates per donor), assessed by pyrosequencing of representative sites. Lines connecting the data points are provided for better visualization of the data. (B) Relationship between methylation status of CCR5 cis-regions (promoter 2 and intron 2) and CCR5 levels (MFI). The line of best fit was determined by fitting the data to a generalized linear model using the exponential distribution. CCR5 methylation was calculated as average percent methylation in indicated cis-regions from pooled data from the same donors as in A. (Right) BGS validation of the inverse correlation between CCR5 expression and DNA methylation content of the indicated CpGs in CCR5-intron 2 derived from CCR5+ T cells with the indicated postsort MFI. (C) HLA-DR+ CD3+ T cells were sorted based on HLA-DR MFI using two arbitrarily set cell-sorting gates designated as low and high HLA-DR–expressing T cells. The methylation content in the sorted cells was determined by BGS. The numbers above the BGS data indicate HLA-DR+ MFI in postsorted T-cell fractions. (D) Methylation levels assessed by pyrosequencing of representative CpGs in the indicated CCR5 cis-regions in CCR5+CD45RO+HLA-DR− CD4+ T cells from three HIV− persons with higher and three persons with lower CCR5 expression (for results from CCR5+CD45RO+HLA-DR+ CD4+ T cells, see SI Appendix, Fig. S3A). The mean percentage methylation values are shown and the error bars depict SEM. (E) Model based on criterion 2.

T-Cell Activation Induces Demethylation of CCR5 cis-Regions.

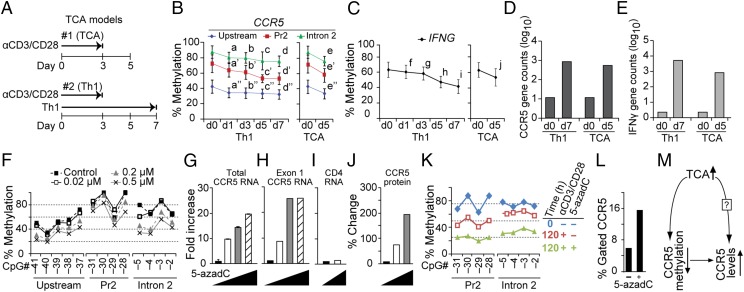

To test criterion 3, we used an in vitro activation model in which naïve T cells were activated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies for 72 h and then cultured for an additional 48 h in the absence of antibodies (Fig. 5A, model 1); this activation protocol is associated with an increase in Pr2-driven full-length transcripts and CCR5 expression (19). In a separate model, naïve T cells were activated and concurrently placed under conditions that favored their polarization toward Th1 cells (Fig. 5A, model 2), which is associated with higher expression of IFN-γ (interferon gamma) and CCR5 (23). T-cell activation models 1 and 2 were associated with a decrease in methylation levels in CCR5 and IFNG (Fig. 5 B and C) and a concomitant increase in CCR5 and IFNG mRNA expression (Fig. 5 D and E).

Fig. 5.

T-cell activation- and/or 5-azadC–induced demethylation of CCR5 cis-regions. (A) Schema of T-cell activation (TCA) models: in vitro TCA (model 1) and Th1 polarization of naïve T cells (model 2). Durations of culture periods with or without TCR (T-cell receptor) stimulation are shown. (B and C) Methylation levels of the indicated cis-regions of (B) CCR5 and (C) CpG sites in IFNG at the indicated time points after in vitro Th1 polarization (Left) or TCA (Right). For IFNG the average methylation content of the six CpG sites in three independent donors is shown. For CCR5 the CpG sites are the same as those examined in Fig. 4A. Error bars indicate SD. Letters denote significant P values by paired Student’s t test for the comparison of each time point at which methylation was assessed relative to the methylation values at baseline (t = 0) and are as follows: for a–j, 0.006, 0.002, 0.009, 0.002, 0.011, 0.093, 0.017, 0.001, 0.002, and 0.029, respectively; for a′–e′, 0.016, 0.017, 0.014, 0.003, and 0.006, respectively; and for a′′–e′′, 0.001, 0.000, 0.001, <0.0001, and <0.0001, respectively. (D and E) CCR5 and IFNG mRNA expression at the indicated time points post Th1 polarization or TCA. The y axis is the log10-transformed raw gene expression signals obtained by RNA-seq. Data are representative of one of three experiments. (F) 5-AzadC dose-dependent DNA demethylation of CCR5 cis-regions in the Jurkat T-cell line. Methylation was assessed by pyrosequencing at the indicated CpG sites in untreated Jurkat cells (closed squares) and treated with 0.02 (open squares), 0.2 (gray triangles), and 0.5 µM 5-azadC (crosses). (G–I) mRNA quantification of (G) total CCR5 mRNA isoforms, (H) CCR5 exon 1-containing transcripts, and (I) CD4 transcripts, all evaluated by quantitative RT-PCR. Data represent fold increase relative to untreated. The error bars in G represent ± SEM. 18S rRNA levels were used for normalization. Increasing concentrations of 5-azadC are represented by triangles (doses are indicated in F). (J) Plots represent the densitometric analysis of CCR5 expression in 5-azadC–treated Jurkat cells. The relative fluorescence intensities were assessed by confocal microscopy (SI Appendix, Fig. S4) and measured using NIH ImageJ software. Signals were normalized relative to actin. (K) Methylation content of the indicated CCR5 CpGs in PBMCs derived from one representative HIV− donor before (blue; t = 0 h) and after 120 h of TCA without 5-azadC (red; t = 120 h) and in the presence of 1 µM 5-azadC (green). (L) CCR5 surface expression (denoted as percent gated cells) after 120 h of TCA in the absence (−) or presence (+) of 1 µM 5-azadC. The data shown are representative of one of three experiments. (M) Three-way relationship between TCA, CCR5 methylation status, and CCR5 surface levels. ?, up-regulation via other mechanisms.

Relationship Between Demethylation and Gene Expression.

We used 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (5-azadC)–induced demethylation and the Jurkat T-cell line as experimental systems to probe the relationship between demethylation of CCR5 cis-regions and up-regulation of CCR5 gene expression. Our rationale was twofold: First, chemically induced demethylation with 5-azadC has been used to establish relationships between methylation and gene expression [e.g., for Foxp3 (26) and Pdcd1 (27)] and, second, Jurkat T cells do not constitutively express CCR5 protein (13) or the Pr2-driven, exon 1-containing transcripts that are a correlate of CCR5 on T cells (19). Increasing concentrations of 5-azadC were associated with a stepwise decrease in methylation levels in CCR5 cis-regions (Fig. 5F and SI Appendix, Fig. S2A, Right). This was associated with a progressive increase in total and exon 1-containing CCR5 transcripts (Fig. 5 G and H) but not of CD4 transcripts (Fig. 5I). 5-AzadC also induced expression of CCR5 protein in Jurkat cells (Fig. 5J and SI Appendix, Fig. S4).

To determine whether activation and 5-azadC had additive effects, we stimulated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) with anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies in the presence or absence of 5-azadC (Fig. 5K). Activation induced demethylation of CCR5 cis-regions (red vs. blue plots; Fig. 5K), but this effect was accentuated in the presence of 5-azadC (green vs. red plots; Fig. 5K), augmenting CCR5 surface expression (Fig. 5L).

Activation, Methylation, and CCR5 Levels.

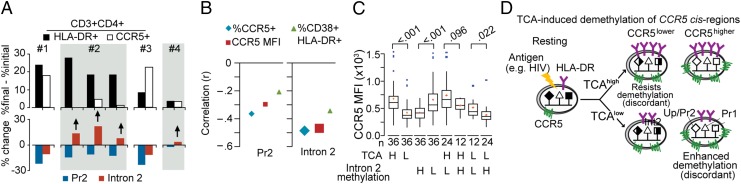

The above-mentioned data highlighted an intricate relationship among activation, CCR5 DNA methylation, and CCR5 surface levels (Fig. 5M). Using T-cell activation model 1 shown in Fig. 5A, we further analyzed this relationship in vitro (n > 20 blood donors). The extent of T-cell activation (categorized as activationhigh vs. activationlow) and changes in CCR5 surface expression levels (categorized as CCR5high vs. CCR5low) and DNA methylation levels in CCR5 cis-regions was classified into four groups (Fig. 6A): (1) Activationhigh-CCR5high was associated with demethylation in both CCR5-Pr2 and intron 2 (concordant epigenetic trait); (2) activationhigh-CCR5low was associated with demethylation in Pr2 but with increased methylation in intron 2 (a discordant epigenetic trait, as activationhigh was expected to be associated with demethylation in intron 2); (3) activationlow-CCR5high was associated with demethylation in both Pr2 and intron 2 (also a discordant trait, as activationlow was expected to be associated with higher methylation in CCR5 cis-regions); and (4) activationlow-CCR5low was associated with minimal changes in Pr2 and intron 2 (a concordant trait).

Fig. 6.

Interindividual differences in sensitivity of CCR5 cis-regions to HIV- or activation-induced demethylation. (A) In vitro TCR activation-induced demethylation of CCR5 cis-regions and the relationship to CCR5 levels and T-cell activation. Changes in (Top) CCR5 and HLA-DR expression on CD3+CD4+ T cells and (Bottom) % methylation of representative CpGs in CCR5-Pr2 and CCR5-intron 2 obtained by pyrosequencing. Changes were assessed in PBMCs from six representative blood donors stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies (19) (the protocol is in Fig. 5A). Data were computed from results at t = 0 h and t = 120 h of the TCA protocol. (B) Correlation (Pearson’s r) between % methylation of CpGs in CCR5-Pr2 (Left) and CCR5-intron 2 (Right) with % CCR5+, CCR5 MFI, and % CD38+HLA-DR+ CD8+ T cells. Large- and small-sized symbols indicate P < 0.01 and P < 0.05, respectively. Data are from 85 HIV+ individuals from the SCOPE (Observational Study of the Consequences of the Protease Inhibitor Era) cohort with ART-induced viral load suppression. (C) Box plots depict the CCR5 levels (MFI) on CD8+ T cells according to whether the activation levels were higher (H) vs. lower (L) than the median TCA in the overall cohort (activation was measured as % CD8+CD38+HLA-DR+ T cells) and/or whether the methylation levels of CCR5-intron 2 were higher vs. lower than median methylation content in this cis-region in the overall cohort. Data are from 72 individuals receiving ART (excluded those bearing the Δ32 mutation). P values are indicated between the groups. Horizontal line in the box, median; ends of the boxes, upper and lower quartiles; red dots in the box, mean; blue dots outside the box, outliers. (D) Model supporting criterion 3.

To determine whether these epigenetic traits existed ex vivo, we investigated methylation levels in PBMCs of 85 HIV-positive individuals (mostly European-Americans) receiving ART. These individuals maintain higher activation despite viral load suppression (i.e., residual activation) (28). This choice allowed evaluation of the relationships among activation, CCR5 methylation, and CCR5 expression without the confounding effects of active viral replication. Levels of activation and CCR5 were each significantly higher on CD8+ compared with CD4+ T cells (P < 0.001; SI Appendix, Fig. S5 A and B). Activation and CCR5 expression on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were positively correlated (r = 0.66 and 0.49; SI Appendix, Fig. S5 C and D). Although higher activation and CCR5 levels were each associated with lower methylation in CCR5-Pr2 and CCR5-intron 2, these inverse correlations were stronger for CCR5 levels than activation (Fig. 6B). This finding suggested that the degree of demethylation in CCR5 was more closely related to CCR5 levels than activation. The inverse correlations were also stronger for the methylation content in CCR5-intron 2 than CCR5-Pr2 (Fig. 6B and SI Appendix, Table S2, models 1 and 2). Reflecting the higher expression of CCR5 on CD8+, the latter associations were stronger in CD8+ vs. CD4+ T cells.

However, CCR5 methylation status was a closer indicator of CCR5 surface levels rather than activation status (Fig. 4 C and D). Furthermore, discordant epigenetic traits (2 and 3) were present (Fig. 6A). Together, these data indicated that the association of methylation status with CCR5 levels partly depended on whether the accompanying activation levels were high or low. To substantiate this possibility ex vivo, we conducted multivariate analyses using the methylation data from the 85 virally suppressed HIV+ patients. When placed in a single model, lower methylation in intron 2 but not in CCR5-Pr2 was associated with higher CCR5 surface levels (P < 0.001 and P = 0.31, respectively; SI Appendix, Table S2, models 1–3). The associations between methylation status of intron 2 and CCR5 levels persisted after controlling for the accompanying levels of T-cell activation and proportion of naïve T cells (P = 0.001), CCR5 haplotypes including the Δ32-bearing allele (P = 0.003), and variables such as CD4+ counts before ART (P = 0.006; SI Appendix, Table S2, models 4–6). The associations between CCR5-Pr2 with CCR5 levels were less robust (P = 0.05, P = 0.05, and P = 0.08; SI Appendix, Table S2, models 4–6). Naïve T cells were included in the models to mitigate potential confounding of interindividual differences in the proportions of naïve T cells, because the CCR5 cis-regions of CD45RO− T cells are more methylated compared with CD45RO+ T cells (Fig. 2 A and B). Similar associations were detected in CD4+ T cells. However, because of lower CCR5 levels on CD4+ compared with CD8+ T cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S5), the associations were statistically weaker.

Mirroring the results of the multivariate models among individuals with comparable levels of T-cell activation (activationhigh or activationlow), a higher vs. lower methylation (methylationhigh vs. methylationlow) content of intron 2 was associated with lower vs. higher CCR5 levels (Fig. 6C). These findings revealed two concordant and two discordant activation-epigenetic traits (Fig. 6 C and D). The concordant traits were activationhigh-methylationlow, which associated with CCR5high, and activationlow-methylationhigh, which associated with CCR5low. Discordant traits were activationhigh-methylationhigh, as it was associated with CCR5low, and activationlow-methylationlow, as it was associated with CCR5high. Methylation status of CCR5-intron 2 explained 32% of the variability in CCR5 levels on CD8+ T cells, more than the explained variability related to activation (∼26%), the proportion of naïve T cells (∼23%), or possession of CCR5-Δ32 (2%). The discovery that CCR5-intron 2 and to a lesser extent CCR5-Pr2 predicted such a large proportion of the variability in CCR5 T-cell levels is consistent with the observation that methylation status of CCR5-intron 2 discriminates CCR5 expression on memory T cells to a greater degree than CCR5-Pr2 (Fig. 2 F–I).

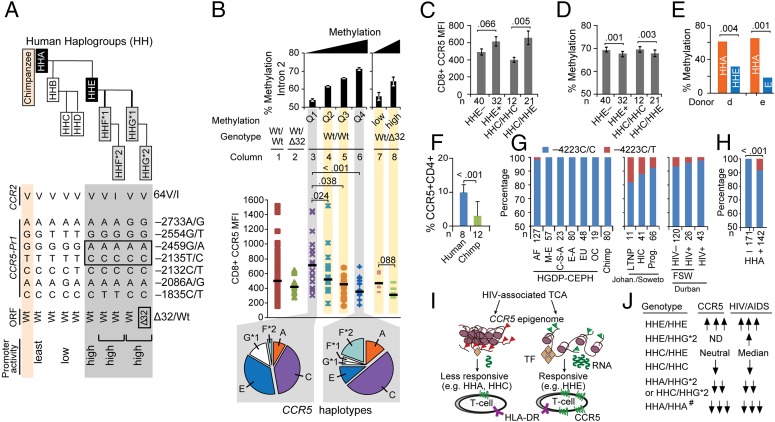

Allele-Specific Activation-Induced Demethylation of CCR5.

A possible reason for the above-mentioned discordant epigenetic traits was polymorphisms in CCR5 cis-regions that amplify vs. dampen the sensitivity of CCR5 cis-regions for activation-associated demethylation (criterion 4). To test this idea, we focused mainly on the ancestral −2459G/−2135T-containing CCR5-HHA haplotype (most comparable to chimpanzee CCR5) and the −2459A/−2135C-containing CCR5-HHE haplotype (Fig. 7A) for two reasons. Foremost, CCR5-HHA and -HHE haplotypes are antipodal with respect to transcriptional (promoter) strengths (least vs. highest, respectively), and thus represent evolutionarily nodal genetic backgrounds upon which additional promoter haplotypes that have low (e.g., HHC) vs. high (HHG) transcriptional activity arose (Fig. 7A) (6). Also, genotypes containing HHA and HHE haplotypes are associated with reduced vs. enhanced HIV/AIDS susceptibility, respectively (4, 5, 7, 10–12).

Fig. 7.

Associations among HIV/AIDS-modifying polymorphisms in CCR5 with increased vs. decreased sensitivity of CCR5 cis-regions to undergoing HIV- or activation-associated demethylation. (A) Polymorphisms in the coding regions of CCR5 [wild type (Wt) vs. Δ32] and CCR2 (V64I) and the CCR5 promoter were categorized into CCR5 human haplogroups (HH) A–G*2 using an evolutionarily based strategy (6). HHF*2 and HHG*2 represent the CCR2-64I– and CCR5-Δ32–containing haplotypes, respectively. Relative haplotype-specific promoter activity assessed by transcriptional reporter assays is indicated (Bottom) (8). (B) Association between DNA methylation (assessed by pyrosequencing of representative CpGs in CCR5-intron 2) and CCR5 levels on CD8+ T cells in 85 HIV+ individuals with stably suppressed viral load (from the SCOPE cohort). Before accounting for methylation content, CCR5 levels (MFI; ordinate) were assessed in subjects dichotomized as those lacking CCR5-Δ32 (Wt/Wt; n = 72) vs. those possessing a CCR5-Δ32 allele (Wt/Δ32; n = 13). Wt/Δ32 persons had a haploid range of CCR5 expression compared with Wt/Wt subjects (columns 1 and 2, respectively). CCR5 levels in Wt/Wt individuals were derived according to the quartiles of the average percent methylation of the representative CpGs in intron 2 (Top; columns 3–6). CCR5 levels in persons with the Wt/Δ32 genotype were dichotomized according to the median of the overall methylation content in intron 2 in these individuals (columns 7 and 8; low vs. high). Horizontal black lines indicate the median values of CCR5 MFI in each group. Pie charts show the frequency of the CCR5 haplotypes in individuals with Wt/Wt genotype whose methylation content in CCR5-intron 2 classified to the least (column 3) and most (column 6) methylated quartiles (Left and Right pie charts, respectively). P values are shown for the differences in CCR5 surface expression according to quartiles of intron 2 methylation in Wt/Wt subjects (with Q1 as the reference) and high vs. low methylation in CCR5-Δ32 heterozygotes. The error bars represent SEM. (C and D) Mean CCR5 expression (C) and mean percentage methylation level of representative CpGs in CCR5-intron 2 (D) in the same individuals (n = 72), categorized by whether they possessed (+) or lacked (−) at least one CCR5-HHE haplotype and whether they possessed the HHC/HHC vs. HHC/HHE genotypes. The error bars represent SEM. (E) In two healthy donors with the CCR5-HHA/HHE genotype, HHA-specific and HHE-specific methylation content was determined by bisulfite genomic sequencing after in vitro TCR stimulation (120 h) with anti-CD3/CD28 Abs. The rs2227010 polymorphism was used to discriminate HHA- vs. HHE-derived clones. (F) Percentage of CD4+ T cells expressing CCR5 in chimpanzee and HIV− humans. The error bars represent SEM. (G) Genotype frequency of CCR5 −4223C/T (rs553615728) in (i) the Human Genome Diversity Project (HGDP)-Centre d'Étude du Polymorphisme Humain (CEPH) populations (AF, Africa; C-S-A, Central South Asia; E-A, East Asia; EU, Europeans; M-E, Middle East; OC, Pacific Ocean) and 80 chimpanzee samples previously studied (44) (Left); (ii) black South Africans from Johannesburg/Soweto (Johan./Soweto) categorized as long-term nonprogressors (LTNP), HIV controllers (HIC), and progressors (Prog.), as defined in SI Appendix, Materials and Methods (Middle); and (iii) black female sex workers (FSW) from Durban, KwaZulu-Natal (CAPRISA cohort), South Africa categorized as those who remained HIV-seronegative (≥2 y follow-up; HIV−) vs. those who acquired HIV during follow-up (HIV+) and a separate cohort of women from the same region who were recruited during primary HIV infection (Right). The differences in genotype frequency should be compared separately in the study groups from the Johannesburg/Soweto and Durban sites, because geographic differences in SNP frequency may exist between these two sites. (H) Linkage disequilibrium of −4223T with CCR5-HHA. Data are from persons of African descent shown in G. (I) Model supporting criterion 4. TF, transcription factor. Red and green triangles represent histone marks. (J) Previously described associations of CCR5 haplotype pairs with CCR5 expression and HIV/AIDS susceptibility. #, inferred from chimpanzee. P values are shown for the compared groups in C–F and H.

For ex vivo analyses, we evaluated the 85 HIV+ individuals maintaining treatment-induced viral suppression (28) to enable study of activation stimuli (i.e., residual activation) that induce demethylation of CCR5 cis-regions in the absence of active viral replication. A substantial proportion of individuals without the CCR5-Δ32–containing HHG*2 haplotype (Wt/Wt) had CCR5 levels as low as those of CCR5-Δ32 heterozygotes (Fig. 7B, columns 1 and 2, respectively). A progressive increase in methylation content [quartile (Q) 1→Q4; i.e., hypermethylation] of intron 2 in Wt/Wt genotypes was associated with progressively lower CCR5 levels (Fig. 7B, columns 3–6). Modest differences in methylation content (∼8–10% between quartiles) were associated with prominent differences in CCR5 levels (Fig. 7B, columns 3–6). Methylation quartiles 3 and 4 were associated with CCR5 levels similar to those of CCR5-Δ32 heterozygotes (Fig. 7B, compare columns 5 and 6 vs. 2). Similarly, among CCR5-Δ32 heterozygotes, higher methylation status of intron 2 was associated with even lower CCR5 levels (Fig. 7B, compare column 7 vs. 8).

A progressive increase in methylation in CCR5-intron 2 was associated with a stepwise decrease in the proportion of Wt/Wt chromosomes with the HIV disease-accelerating HHE haplotype (P = 0.002 by Cochran–Amitrage test for trend) and, conversely, an increase in the proportion of Wt/Wt chromosomes with HIV disease-retarding haplotypes (e.g., HHA, HHC, and HHF*2) (4, 5, 7, 10–12) (Fig. 7B, pie slices). The detrimental HHE was associated with an ∼70% lower likelihood, whereas the protective CCR5-HHC/HHC genotype (5, 7) was associated with a 3.7-fold higher likelihood of having higher compared with lower methylation in intron 2 [HHE: odds ratio (OR) = 0.28, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.11–0.74, P = 0.01; CCR5-HHC/HHC genotype: OR = 3.67, 95% CI = 0.90–14.90, P = 0.06].

These data indicated that T-cell CCR5 levels linked to a CCR5 haplotype pair (genotype) are, in part, related to whether one or both haplotypes manifest increased (e.g., HHE) vs. reduced (e.g., HHA or HHC) sensitivity to activation-associated demethylation. Congruent with this idea, genotypes containing at least one HHE compared with those lacking HHE were associated with higher CCR5 levels (Fig. 7C) and lower intron 2 methylation content (Fig. 7D). In contrast, HHC/HHC compared with HHC/HHE haplotype pairs were associated with lower CCR5 levels (Fig. 7C) and higher intron 2 methylation content (Fig. 7D). To mitigate confounding effects of the CCR5-Δ32 mutation on CCR5 levels, in these analyses we excluded individuals (n = 13) bearing one Δ32-containing HHG*2 haplotype. In our cohort, those lacking HHE mainly had the CCR5-HHA/HHC or -HHC/HHC haplotype pairs; these genotypes are associated with lower CCR5 expression, HIV disease retardation, and higher cell-mediated immunity (5). These methylation patterns linked to CCR5 genotype were confirmed in a cohort of 81 therapy-naïve HIV+ women from Ukraine (SI Appendix, Fig. S6A).

To further confirm that CCR5 haplotypes are associated with differential susceptibilities to undergoing activation-induced demethylation, we evaluated T cells derived from HIV-negative persons with the CCR5-HHA/HHE haplotype pair after in vitro TCR (T-cell receptor) stimulation with anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies. This approach had three advantages. First, it allowed us to evaluate the extent of activation-induced demethylation of the CCR5-HHA and -HHE haplotypes concurrently using identical in vitro T-cell activation conditions. We focused on CCR5-HHA and -HHE because, as noted above, they are associated with antipodal transcriptional and clinical outcomes, and HHA is the ancestral haplotype. Second, this approach mitigated the confounding that occurs when comparing persons with the CCR5-HHA/HHA vs. -HHE/HHE haplotype pairs, as differences in their immune health could influence methylation status. Third, this approach controls for racial differences, as HHA/HHA and HHE/HHE are prevalent mainly in persons of African vs. European descent (29).

We observed that CCR5-HHA and CCR5-HHE exhibited reduced vs. increased permissiveness, respectively, to undergo activation-induced demethylation in vitro (Fig. 7E). This was also associated with differential production of HHA (less) and HHE (more) specific mRNA in heterozygous HHA/HHE donors (SI Appendix, Fig. S6 B and C). The idea that the ancestral HHA is a correlate of reduced CCR5 transcription/expression was also highlighted by cross-species comparisons of CCR5 levels. Chimpanzees are homozygous for HHA (6), and % CD4+CCR5+ T cells expressing CD4+ cells was lower in chimpanzees vs. humans (Fig. 7F).

Genotype-dependent differences in responsiveness to activation-associated demethylation in humans may relate to the finding that single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in CCR5 cis-regions create or disrupt CpG dinucleotides in a haplotype-specific manner (SI Appendix, Fig. S7). These haplotype-specific polymorphisms could potentially alter the binding of several transcription factors, including those that were previously implicated in CCR5 regulation [e.g., C/EBPβ, CREB1, and POU2F2/Oct-2 (19–21)], and thus might impact CCR5 transcription and its expression (SI Appendix, Fig. S8).

Of note, an SNP designated −4223C/T (rs553615728) (30) disrupts the CpG −41 site (SI Appendix, Fig. S7) and alters the core consensus motif of a CREB1 binding site (SI Appendix, Fig. S8 A and B). This SNP is uniquely present in persons from southern Africa (Fig. 7G, Left), and it occurs on the background of HHA (Fig. 7H and SI Appendix, Fig. S7). To determine its associations, we examined blacks from two separate regions of South Africa. In blacks from Johannesburg/Soweto, the frequency of this SNP was greater in long-term nonprogressors and HIV controllers compared with progressors (Fig. 7G, Middle). In black female sex workers from Durban (31), this SNP was overrepresented in those resisting HIV infection compared with those who subsequently acquired HIV infection as well as a separate cohort of women recruited during primary HIV infection (Fig. 7G, Right). Although suggestive of a protective effect, these associations did not reach statistical significance because of the low prevalence of the SNP in the general population and small sample sizes. Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) showed reduced binding of CREB1 to the polymorphic −4223T compared with wild-type −4223C (SI Appendix, Fig. S8C). Notably, publicly available ChIP-seq data confirmed cell type-specific ex vivo CREB1 enrichment in this region (Fig. 1B and SI Appendix, Fig. S8D).

Collectively, these data support criterion 4 (Fig. 7I). They also provide an epigenetic mechanism for the reported associations of CCR5 genotype with HIV acquisition/disease shown in Fig. 7J. These associations reflect whether the CCR5 genotype contains one or two haplotypes with CCR5 cis-regions that correlate with (i) increased (e.g., HHE) vs. reduced (e.g., HHA, HHC) sensitivity to activation-induced demethylation and epigenetic remodeling, and (ii) whether the genotype did vs. did not contain the CCR5-Δ32–containing HHG*2 haplotype (Fig. 7J).

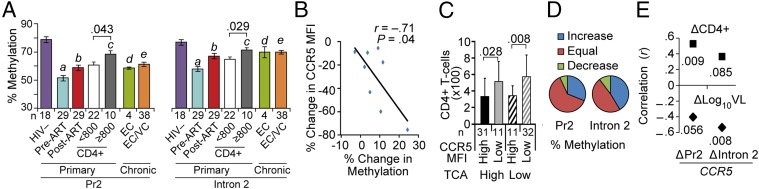

Association of CCR5 DNA Methylation and HIV Disease.

HIV-associated demethylation of CCR5 cis-regions was confirmed in a cohort with primary HIV infection (Fig. 8A) and two groups of patients with chronic untreated infection (SI Appendix, Fig. S9A). Suppression of viral replication by ART during primary infection was associated with increased methylation (Fig. 8A). Methylation in CCR5 cis-regions was similar in individuals with viral load suppressed by ART and in spontaneous virologic controllers [i.e., HIV+ individuals who maintain a low viral load without ART (32)], but the methylation content in both groups was significantly lower than that in HIV− persons (Fig. 8A).

Fig. 8.

Associations of DNA methylation status in HIV-infected patients. (A) Methylation status of representative CpGs in CCR5-Pr2 and CCR5-intron 2 assessed by pyrosequencing in PBMCs of (i) HIV-seronegative (HIV−) healthy persons; (ii) HIV+ individuals recruited during acute infection in whom methylation status was evaluated before (pre-ART) and after (post-ART) suppression of viral replication by ART initiated during acute infection; or (iii) elite or viremic controllers (EC/VC) accrued during acute infection (cohort from ii) or chronic infection in the SCOPE cohort. Significance values are for the following comparisons: a, pre-ART HIV+ vs. HIV−; b, pre-ART vs. post-ART; c, post-ART with CD4+ ≥800 cells per μL vs. HIV−; and d and e, EC or EC/VC vs. HIV−; a–e were each P < 0.001. Mean percentage methylation is shown and the error bars represent SEM. (B) Relationship between changes in CCR5 levels on CD8+ T cells and CCR5-intron 2 methylation content during ART in eight paired HIV+ subjects from SCOPE. (C) Conjoint impact of CCR5 expression and T-cell activation levels (% CD8+CD38+HLA-DR+ T cells) on current CD4+ T-cell counts in the 85 viral load-suppressed HIV+ subjects from SCOPE. Higher vs. lower activation was defined by whether values were higher vs. lower than the median. The mean cell counts are shown and the error bars represent standard deviation. (D) Changes in methylation content in 29 HIV+ therapy-naïve black women from Durban, South Africa (CAPRISA cohort). The net change in % methylation between two time points during early HIV infection was classified into three groups depending on whether the percent methylation of representative CpG sites in CCR5-Pr2 and CCR5-intron 2 increased or decreased at least 5%; otherwise they were considered to be “equal.” (E) Correlation (Spearman’s r) between net change (Δ) in methylation in CCR5-Pr2 and CCR5-intron 2 (i.e., ΔCCR5-Pr2 and ΔCCR5-intron 2; Bottom) observed in two paired samples with net change in log10 viral load (Bottom; ΔLog10VL) and CD4+ T-cell counts (Top; ΔCD4). Significance values for correlations are indicated.

When comparing individuals with chronic HIV infection for whom pre- and posttreatment CD4+ data were available (n = 8), initiation of ART was associated with decreased CCR5 levels (P = 0.04) and increased methylation content of CCR5-intron 2 (P = 0.02). In paired analyses, changes in methylation status of intron 2 and CCR5 levels were negatively correlated (rho = −0.71, P = 0.04; Fig. 8B). Previously, we showed that in patients receiving ART, normalization of CD4+ counts (>800 cells per μL) was associated with beneficial clinical and immune outcomes (33). In the present study, among HIV+ patients who received ART during primary infection, CD4+ ≥800 vs. <800 cells per μL was associated with higher intron 2 methylation status (Fig. 8A). However, despite reaching CD4+ normalization, methylation content in intron 2 remained lower than in HIV− persons (Fig. 8A). In the 85 HIV+ patients receiving ART, methylation status of intron 2 was an independent determinant of CCR5 levels (Fig. 6C and SI Appendix, Table S2). In these individuals, CCR5 levels and activation had additive effects on current CD4+ counts (Fig. 8C).

We also examined 29 therapy-naïve HIV+ South African women with known estimated dates of infection, from whom samples at two time points post HIV infection were available. Spontaneous (albeit incomplete) recovery of the methylation status of CCR5 cis-regions was associated with a lower viral load and higher CD4+ during the early stages of untreated HIV (Fig. 8 D and E). Representative examples are shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S9B.

Discussion

Using both in vitro and ex vivo approaches, we demonstrate that the methylation status of CCR5 cis-regions satisfies the criteria to serve as a unifying mechanism for the four characteristic features of CCR5 expression on T cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S1): manifesting differences among distinct T-cell subsets and individuals as a mechanism for inter–T cell-type and interindividual differences in CCR5 expression (criteria 1 and 2); responsiveness to activation as a mechanism for the positive correlation between activation and CCR5 levels (criterion 3); and CCR5 genotype-dependent differences in sensitivity to activation as a mechanism for interindividual differences in susceptibility to activation- or HIV-associated up-regulation of CCR5 expression (criterion 4). We therefore propose that the constitutive and activation-induced DNA methylation status of CCR5 cis-regions may contribute substantially to HIV risk and immune outcomes (SI Appendix, Fig. S1).

Our results indicate that CpG −41 represents an evolutionarily conserved epigenetic and transcriptional landmark. Downstream of this CpG site, CCR5 cis-regions manifest a specific hierarchy of methylation content (highest to least) that depends on both the differentiation and CCR5 expression status of T cells [i.e., RA+RO− CCR5− > RA+RO− CCR5+ (TEMRA) ≥ RA−RO+ CCR5− > RA−RO+ CCR5+ T cells]. This hierarchy suggests that upon activation and differentiation of T cells, DNA demethylation in the CCR5 cis-region commences close to this site. Further substantiating this possibility, this CpG site colocalizes within a region that exhibits increased nuclease sensitivity (chromatin accessibility) in memory compared with naïve T cells (19). The hierarchy of methylation content supports a model of CCR5 gene expression wherein the balance between the repressive vs. permissive effects of methylation vs. demethylation on the transcriptional activity/function of specific CCR5 cis-regulatory regions underlies the (i) differential activity of its two promoters in resting vs. activated T cells and (ii) contrasting expression patterns of CCR5 mRNA isoforms and surface levels across T-cell subsets (model is shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S10).

Relatively small differences in the methylation content of CCR5 cis-regions in T cells were associated with a large impact on CCR5 levels in both HIV− and HIV+ persons. This result is congruent with the finding from whole-methylome analyses of PBMCs, showing that up to 13% of differences in methylation levels differentiates highly expressed vs. silent genes (34). The observed inverse exponential relationship between methylation content of specific CCR5 cis-regions and CCR5 levels may represent the epigenetic corollary to the finding that once a threshold level of CCR5 on T cells is reached, small increases thereafter are associated with large increases in HIV infectivity, viral replication, and AIDS progression rates (35, 36). Conceivably, the demethylating impact of inflammatory stimuli, for example by coinfections (e.g., sexually transmitted diseases), may poise the CCR5 methylation content in T cells at threshold levels, whereupon exposure to HIV and the ensuing demethylating impact of HIV may tip the balance toward increased CCR5 levels, promoting HIV acquisition and/or disease progression.

The methylation status of CCR5-intron 2 closely tracked CCR5 levels on memory T cells, suggesting that its contribution to outcomes in HIV or other inflammatory diseases could potentially be substantial. Underscoring this point, (i) the association of CCR5-intron 2 methylation status with CCR5 levels was independent of T-cell activation and other covariates; (ii) CCR5 levels of genotypes bearing a hypermethylated intron 2 were comparable to CCR5 haploinsufficiency imparted by heterozygosity for the CCR5-Δ32 allele; and (iii) the methylation status of CCR5-intron 2 explained a higher proportion of the variability in CCR5 levels than that explained by either activation or CCR5 genotype.

Our data suggest that CCR5 haplotypes contain polymorphisms that by creating or destroying CpG sites may result in cis-regions that are more susceptible (e.g., HHE) vs. resistant (e.g., HHA, HHC) to undergoing activation-induced demethylation, despite comparable levels of activation. Thus, the effects associated with a CCR5 genotype (e.g., surface levels and HIV/AIDS risk) depend on both epigenetic and genetic mechanisms. However, epigenetic mechanisms could have dominant effects, as illustrated by the associations of HHE: (i) HHE/HHE is consistently associated with increased CCR5 expression and HIV/AIDS susceptibility, and (ii) pairing of HHE with HHA, HHC, or HHG*2 is also associated with adverse clinical outcomes (5, 12).

Our bioinformatics studies suggest that a possible mechanism for these epihaplotypes is the differential binding of transcription factors that influence methylation status (37). In proof-of-principle studies, we focused on the SNP −4223C/T, because it disrupts the CpG −41 site. This SNP alters the binding of CREB1. This alteration may have functional consequences, because DNA methylation levels correlate with sequence-specific binding of CREB1 to a TCR-responsive intronic enhancer of FoxP3 (38), and CREB1 plays a key role in the regulation of multiple T cell-specific genes (39) and CCR5 (20). The overrepresentation of this SNP in persons with protective HIV phenotypes needs confirmation, but is in general agreement with data suggesting that the ancestral CCR5-HHA haplotype on which this SNP arises is associated with lower CCR5 expression and a protective phenotype in humans and chimpanzees (5, 7, 11, 12). Our previous work suggested that balancing selection has shaped the pattern of variation in CCR5 and that HIV-1 resistance afforded by CCR5 5′ cis-regulatory region haplotypes may be the consequence of adaptive changes to older pathogens (40). The restriction of the SNP at CpG −41 to southern Africa, the epicenter of the HIV epidemic, and its observed associations further substantiate this thesis.

A pathogenic model can be conceptualized wherein upon infection, HIV-associated activation leads to a decline in methylation levels in CCR5 cis-regions. Thereafter, in therapy-naïve persons, because of relative susceptibility vs. resistance to the demethylating impact of HIV-associated activation, methylation status either remains low or displays spontaneous recovery, with greater levels of recovery (hypermethylation) associating positively with lower viral load and higher CD4+ T-cell counts. However, compared with HIV-negative individuals, these cis-regions remain in a relatively demethylated state in HIV+ persons, despite spontaneous or ART-induced undetectable levels of viral replication and normalization of CD4+ counts. Several lines of evidence indicate that higher CCR5 levels may directly promote T-cell activation (41–43). Hence, the higher CCR5 associated with a demethylated CCR5 cis-region in HIV+ persons, despite suppression of viral load and CD4+ normalization, may serve as a persistent stimulus for low-grade residual T-cell activation. This may explain why CCR5 blockers are associated with immunologic benefits unrelated to an antiviral effect (1).

In summary, our findings provide a paradigmatic example by which epigenetic mechanisms that regulate gene expression (e.g., DNA methylation of cis-regulatory regions) may interact with genetics (e.g., promoter polymorphisms) and environment-induced host responses (e.g., activation in response to HIV infection) to affect a trait (i.e., CCR5 surface levels) that influences disease outcomes (i.e., HIV/AIDS susceptibility). The coupling of activation with genetically determined differences in activation-induced demethylation provides a heretofore unrecognized link among activation and CCR5 epigenetic/genetic traits with HIV/AIDS susceptibility. Therapeutic exploitation of this link may have clinical utility. The proclivity of CCR5 cis-regions to undergo demethylation upon activation may promote the life cycle of HIV and sustain the HIV epidemic, especially because the CCR5 haplotype (HHE) with greatest susceptibility for demethylation upon activation, a central feature of HIV infection, is among the most prevalent CCR5 haplotypes in human populations (29).

Materials and Methods

All studies were approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio and institutions participating in this study. Detailed methods for cell culture, PBMC isolation, flow cytometry and cell sorting, Th1 polarization, 5-azadC treatment, and statistical analyses are provided in SI Appendix, Materials and Methods. CCR5 numbering system is as described previously (6) and the CpG sites examined are shown in SI Appendix, Table S1. CCR5 polymorphisms were genotyped as previously described (7). DNA methylation status was assessed by bisulfite genomic sequencing and also by pyrosequencing assays. Primers and PCR conditions are listed in SI Appendix, Tables S3 and S4, respectively, and quality controls are shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S11 and Table S5. Methylation levels were measured in PBMCs for cohort studies except for subjects from Ukraine, in whom whole blood was used. We used previously published methods for conducting antibody mobility shift assays and RT-PCR (6, 19). Experimental details for RNA-seq are provided in SI Appendix, Materials and Methods. The sequences of the oligonucleotides used for performing allelic expression imbalance analysis and EMSA are shown in SI Appendix, Table S3. Details of motif analysis for transcription factor binding sites are in SI Appendix, Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments and funding agencies that supported this work are indicated in SI Appendix.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1423228112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Corbeau P, Reynes J. CCR5 antagonism in HIV infection: Ways, effects, and side effects. AIDS. 2009;23(15):1931–1943. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832e71cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paxton WA, et al. Reduced HIV-1 infectability of CD4+ lymphocytes from exposed-uninfected individuals: Association with low expression of CCR5 and high production of beta-chemokines. Virology. 1998;244(1):66–73. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reynes J, Baillat V, Portales P, Clot J, Corbeau P. Low CD4+ T-cell surface CCR5 density as a cause of resistance to in vivo HIV-1 infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;34(1):114–116. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200309010-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hladik F, et al. Combined effect of CCR5-delta32 heterozygosity and the CCR5 promoter polymorphism −2459 A/G on CCR5 expression and resistance to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transmission. J Virol. 2005;79(18):11677–11684. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.18.11677-11684.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Catano G, et al. Concordance of CCR5 genotypes that influence cell-mediated immunity and HIV-1 disease progression rates. J Infect Dis. 2011;203(2):263–272. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiq023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mummidi S, et al. Evolution of human and non-human primate CC chemokine receptor 5 gene and mRNA. Potential roles for haplotype and mRNA diversity, differential haplotype-specific transcriptional activity, and altered transcription factor binding to polymorphic nucleotides in the pathogenesis of HIV-1 and simian immunodeficiency virus. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(25):18946–18961. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000169200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gonzalez E, et al. Race-specific HIV-1 disease-modifying effects associated with CCR5 haplotypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(21):12004–12009. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.12004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kawamura T, et al. R5 HIV productively infects Langerhans cells, and infection levels are regulated by compound CCR5 polymorphisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(14):8401–8406. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1432450100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salkowitz JR, et al. CCR5 promoter polymorphism determines macrophage CCR5 density and magnitude of HIV-1 propagation in vitro. Clin Immunol. 2003;108(3):234–240. doi: 10.1016/s1521-6616(03)00147-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin MP, et al. Genetic acceleration of AIDS progression by a promoter variant of CCR5. Science. 1998;282(5395):1907–1911. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5395.1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tang J, et al. Distribution of chemokine receptor CCR2 and CCR5 genotypes and their relative contribution to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) seroconversion, early HIV-1 RNA concentration in plasma, and later disease progression. J Virol. 2002;76(2):662–672. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.2.662-672.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaslow RA, Dorak T, Tang JJ. Influence of host genetic variation on susceptibility to HIV type 1 infection. J Infect Dis. 2005;191(Suppl 1):S68–S77. doi: 10.1086/425269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu L, et al. CCR5 levels and expression pattern correlate with infectability by macrophage-tropic HIV-1, in vitro. J Exp Med. 1997;185(9):1681–1691. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.9.1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bleul CC, Wu L, Hoxie JA, Springer TA, Mackay CR. The HIV coreceptors CXCR4 and CCR5 are differentially expressed and regulated on human T lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94(5):1925–1930. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.5.1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ostrowski MA, et al. Expression of chemokine receptors CXCR4 and CCR5 in HIV-1-infected and uninfected individuals. J Immunol. 1998;161(6):3195–3201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cedar H, Bergman Y. Programming of DNA methylation patterns. Annu Rev Biochem. 2012;81:97–117. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-052610-091920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lim PS, Shannon MF, Hardy K. Epigenetic control of inducible gene expression in the immune system. Epigenomics. 2010;2(6):775–795. doi: 10.2217/epi.10.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schalkwyk LC, et al. Allelic skewing of DNA methylation is widespread across the genome. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;86(2):196–212. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mummidi S, et al. Production of specific mRNA transcripts, usage of an alternate promoter, and octamer-binding transcription factors influence the surface expression levels of the HIV coreceptor CCR5 on primary T cells. J Immunol. 2007;178(9):5668–5681. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.9.5668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuipers HF, et al. CC chemokine receptor 5 gene promoter activation by the cyclic AMP response element binding transcription factor. Blood. 2008;112(5):1610–1619. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-135111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosati M, Valentin A, Patenaude DJ, Pavlakis GN. CCAAT-enhancer-binding protein beta (C/EBP beta) activates CCR5 promoter: Increased C/EBP beta and CCR5 in T lymphocytes from HIV-1-infected individuals. J Immunol. 2001;167(3):1654–1662. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.3.1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heidari N, et al. Genome-wide map of regulatory interactions in the human genome. Genome Res. 2014;24(12):1905–1917. doi: 10.1101/gr.176586.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loetscher P, et al. CCR5 is characteristic of Th1 lymphocytes. Nature. 1998;391(6665):344–345. doi: 10.1038/34814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oswald-Richter K, et al. Identification of a CCR5-expressing T cell subset that is resistant to R5-tropic HIV infection. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3(4):e58. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wierda RJ, et al. Epigenetic control of CCR5 transcript levels in immune cells and modulation by small molecules inhibitors. J Cell Mol Med. 2012;16(8):1866–1877. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01482.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moon C, et al. Use of epigenetic modification to induce FOXP3 expression in naïve T cells. Transplant Proc. 2009;41(5):1848–1854. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2009.02.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Youngblood B, et al. Chronic virus infection enforces demethylation of the locus that encodes PD-1 in antigen-specific CD8(+) T cells. Immunity. 2011;35(3):400–412. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hunt PW, et al. Relationship between T cell activation and CD4+ T cell count in HIV-seropositive individuals with undetectable plasma HIV RNA levels in the absence of therapy. J Infect Dis. 2008;197(1):126–133. doi: 10.1086/524143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gonzalez E, et al. Global survey of genetic variation in CCR5, RANTES, and MIP-1alpha: Impact on the epidemiology of the HIV-1 pandemic. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(9):5199–5204. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091056898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Picton AC, Paximadis M, Tiemessen CT. Genetic variation within the gene encoding the HIV-1 CCR5 coreceptor in two South African populations. Infect Genet Evol. 2010;10(4):487–494. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2010.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ramsuran V, et al. Duffy-null-associated low neutrophil counts influence HIV-1 susceptibility in high-risk South African black women. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(10):1248–1256. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deeks SG, Walker BD. Human immunodeficiency virus controllers: Mechanisms of durable virus control in the absence of antiretroviral therapy. Immunity. 2007;27(3):406–416. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Okulicz JF, et al. Influence of the timing of antiretroviral therapy on the potential for normalization of immune status in human immunodeficiency virus 1–infected individuals. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(1):88–99. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.4010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li Y, et al. The DNA methylome of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. PLoS Biol. 2010;8(11):e1000533. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Platt EJ, Wehrly K, Kuhmann SE, Chesebro B, Kabat D. Effects of CCR5 and CD4 cell surface concentrations on infections by macrophagetropic isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1998;72(4):2855–2864. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.2855-2864.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin YL, et al. Cell surface CCR5 density determines the postentry efficiency of R5 HIV-1 infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(24):15590–15595. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242134499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leung A, Schones DE, Natarajan R. Using epigenetic mechanisms to understand the impact of common disease causing alleles. Curr Opin Immunol. 2012;24(5):558–563. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim HP, Leonard WJ. CREB/ATF-dependent T cell receptor-induced FoxP3 gene expression: A role for DNA methylation. J Exp Med. 2007;204(7):1543–1551. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wen AY, Sakamoto KM, Miller LS. The role of the transcription factor CREB in immune function. J Immunol. 2010;185(11):6413–6419. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bamshad MJ, et al. A strong signature of balancing selection in the 5′ cis-regulatory region of CCR5. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(16):10539–10544. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162046399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Camargo JF, et al. CCR5 expression levels influence NFAT translocation, IL-2 production, and subsequent signaling events during T lymphocyte activation. J Immunol. 2009;182(1):171–182. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.1.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Portales P, et al. The intensity of immune activation is linked to the level of CCR5 expression in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected persons. Immunology. 2012;137(1):89–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2012.03609.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schröder C, et al. CCR5 blockade modulates inflammation and alloimmunity in primates. J Immunol. 2007;179(4):2289–2299. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.4.2289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gonzalez E, et al. The influence of CCL3L1 gene-containing segmental duplications on HIV-1/AIDS susceptibility. Science. 2005;307(5714):1434–1440. doi: 10.1126/science.1101160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.