Significance

Horizontal gene transfer is a major force in bacterial evolution, and a widespread mechanism involves conjugative plasmids. Albeit potentially beneficial at the population level, plasmid transfer is a burden for individual cells. Therefore, assembly of the conjugation machinery is strictly controlled, especially under stress. Here, we describe an RNA-based regulatory circuit in host–plasmid communication where a regulatory RNA (RprA) inhibits plasmid transfer through posttranscriptional activation of two genes. Because one of the activated factors (σS) is necessary for transcription of the other (RicI), RprA forms the centerpiece of a posttranscriptional feedforward loop with AND-gate logic for gene activation. We also show that the synthesis of RicI, a membrane protein, inhibits plasmid transfer, presumably by interference with pilus assembly.

Keywords: RprA, sRNA, feedforward control, plasmid conjugation, Hfq

Abstract

Horizontal gene transfer via plasmid conjugation is a major driving force in microbial evolution but constitutes a complex process that requires synchronization with the physiological state of the host bacteria. Although several host transcription factors are known to regulate plasmid-borne transfer genes, RNA-based regulatory circuits for host–plasmid communication remain unknown. We describe a posttranscriptional mechanism whereby the Hfq-dependent small RNA, RprA, inhibits transfer of pSLT, the virulence plasmid of Salmonella enterica. RprA employs two separate seed-pairing domains to activate the mRNAs of both the sigma-factor σS and the RicI protein, a previously uncharacterized membrane protein here shown to inhibit conjugation. Transcription of ricI requires σS and, together, RprA and σS orchestrate a coherent feedforward loop with AND-gate logic to tightly control the activation of RicI synthesis. RicI interacts with the conjugation apparatus protein TraV and limits plasmid transfer under membrane-damaging conditions. To our knowledge, this study reports the first small RNA-controlled feedforward loop relying on posttranscriptional activation of two independent targets and an unexpected role of the conserved RprA small RNA in controlling extrachromosomal DNA transfer.

Intercellular transmission of plasmid DNA is key to bacterial evolution and diversity (1). In the widespread family of F-like conjugative plasmids, environmental cues and mating partner availability affect conjugation frequency, and unregulated conjugation comes with significant fitness costs for the host (2). It is well understood how conjugation is regulated by plasmid-borne factors. For example, conjugation of the self-transmissible F-like plasmid pSLT [which encodes several virulence genes and is required for systemic disease (3)] of Salmonella species depends on TraJ, the transcriptional activator of the transfer (tra) operon (4). Synthesis of TraJ itself is precisely controlled by a cis-antisense RNA, FinP, which in concert with the dedicated RNA chaperone, FinO, inhibits translation of the traJ mRNA (5). As a result, most cells reside in a conjugational OFF-state under regular physiological conditions (6).

Besides plasmid-encoded factors, core genome-encoded proteins such as the leucine-responsive regulatory protein (Lrp), the ArcAB two-component system, and Dam methylation affect pSLT conjugation (7, 8). These factors usually respond to specific ecological cues; for example, ArcAB responds to microaerophilic conditions, the environment that bacteria will encounter in the intestine of infected hosts (9). In addition, host-produced compounds such as bile salts repress pSLT conjugation, but the underlying molecular mechanisms are unknown (10).

The regulatory networks of the host that restrict plasmid conjugation to permissive conditions must integrate various physiological signals. This may involve small RNAs (sRNAs) that can cross-connect gene expression at the posttranscriptional level through their ability to repress or activate multiple target mRNAs (11, 12). Intriguingly, the RNA chaperone Hfq, which helps many sRNAs to regulate their targets (13, 14), has been reported to affect the transfer of F-like plasmids (15), suggesting that host–plasmid communication does involve regulatory activities of noncoding RNA molecules. However, Hfq-dependent sRNAs controlling plasmid conjugation were hitherto unknown.

In this work, we have studied the role of RpoS regulator RNA A (RprA) in Salmonella enterica. RprA is one of three sRNAs (the others being DsrA and ArcZ) that activate translation of rpoS mRNA encoding the alternative sigma-factor σS (16–18). All three sRNAs act by an anti-antisense mechanism whereby their base pairing with the rpoS mRNA opens an inhibitory structure in the 5′-untranslated region (5′-UTR) to promote translation initiation (19). In Escherichia coli, expression of RprA is induced during stationary-phase growth (20) through either of two signal transduction pathways, Rcs (21) or CpxAR (22). The fact that both Rcs and CpxAR respond to insults to the bacterial cell envelope (23, 24) suggests a role for RprA in the extracytoplasmic stress responses and membrane homeostasis.

Here, we describe that in Salmonella RprA controls a large set of mRNAs in addition to rpoS, including ricI (STM4242) mRNA. Similar to its known rpoS target (21), RprA activates the ricI mRNA through opening of an inhibitory structure in the 5′-UTR. However, unlike rpoS regulation, which is regulated through the 5′ end of RprA, it is the conserved 3′ end of RprA that recognizes the ricI mRNA, revealing RprA as the first (to our knowledge) regulatory RNA with two activating seed-pairing domains.

From a physiological point of view, RicI is shown to inhibit pSLT conjugation through interaction with anchor protein TraV of the type IV secretion apparatus to restrict the number of conjugation pili. RprA activates the synthesis of RicI in the presence of bile salts, and components of the Rcs phosphorelay as well as σS are required for this process. Thus, RprA and σS act in concert to activate RicI synthesis via a feedforward loop (FFL) with AND-gate decision logic to control plasmid transfer. Donor cells lacking one component of this regulatory mechanism, i.e., RprA, σS, or RicI, display increased conjugation rates, a phenotype that is exacerbated under conditions of envelope stress.

Results

Two Isoforms of RprA Regulate Target mRNAs.

The function of RprA as a posttranscriptional activator of σS synthesis has been well established in E. coli (20, 21, 25, 26). By contrast, this “core” sRNA, which is conserved in many enterobacterial species, was reported to have little if any role in the closely related pathogen, Salmonella Typhimurium (27), although both RprA and its target region in the rpoS mRNA are fully conserved (28, 29). To address this discrepancy, we monitored RprA expression in Salmonella on a Northern blot using a probe complementary to the conserved 3′ end of the sRNA. Expression of RprA peaked during stationary phase, and we detected two forms of RprA: a full-length transcript of ∼107 nt and a shorter processed 3′-end fragment of ∼50 nt (Fig. 1 A and B). This is in agreement with previous studies in E. coli (30) and RNA-seq experiments in Salmonella (28, 31, 32).

Fig. 1.

Multiple target regulation by RprA in Salmonella. (A) Alignment of the rprA gene from selected enterobacterial species (ECA, Erwinia carotovora; ECO, Escherichia coli K12; KPN, Klebsiella pneumoniae; PLU, Photorhabdus luminescens; SFL, Shigella flexneri; STM, Salmonella enterica sv. Typhimurium). Transcription control regions −10 and −35 are boxed, the transcription initiation site is marked by an arrow. Scissors indicate the RprA processing site, and inverted arrows refer to the rho-independent terminator. (B) Northern blot analysis of RprA in Salmonella. Samples were collected at several stages of growth (OD600 of 0.5, 1.0, and 2.0, at 3 and 6 h after cells had reached OD600 of 2.0, and after 24 h of cultivation). 5S rRNA served as loading control. (C) Microarray analysis of RprA full-length and RprA processed pulse expression. Expression profiles of pulse-induced full-length and processed RprA were compared with samples carrying control plasmids. A heat map of genes regulated by full-length RprA (more than twofold) is shown and compared with regulation by processed RprA. (D) Western and Northern blot analyses of σS, RicI::3×FLAG, and RprA production after pulse expression of full-length and processed RprA. Wild-type and ΔrprA carrying the indicated plasmids were grown to early stationary phase (OD600 of 1.5) and induced for pBAD expression. 5S rRNA (Northern blot) and GroEL (Western blot) served as loading controls.

To identify mRNA targets of both RprA forms, we pulse-expressed (10 min) either the full-length or the processed sRNA from a pBAD promoter and scored global transcriptome changes on microarrays, comparing to an empty vector control (33). Induction of the full-length RprA altered the expression of 64 genes (Fig. 1C), one of which was rpoS (+2.5-fold), rectifying that σS activation by RprA is functionally conserved in Salmonella. As expected from the previously mapped RprA–rpoS RNA interaction (21, 34), processed RprA did not activate rpoS expression. Twelve genes were regulated by both the full-length and processed RprA, 11 of which were repressed by RprA (Fig. 1C). We did not observe the previously reported RprA-mediated repression of csgD (35, 36), perhaps because the csgD promoter was silent under the experimental conditions used here (37). This notwithstanding, our pulse expression data suggested that the two forms of RprA recognize several targets by different seed regions and predicted processed RprA to be a regulator in its own right.

One gene, ricI (also known as STM4242), was up-regulated by both forms of RprA (Fig. 1C). To test the contribution of each isoform to RicI synthesis, we added a 3×FLAG epitope to the chromosomal ricI gene and monitored RicI protein levels upon induction of full-length or processed RprA. Indeed, both forms of RprA equally activated RicI expression (Fig. 1D), whereas only full-length RprA induced σS production.

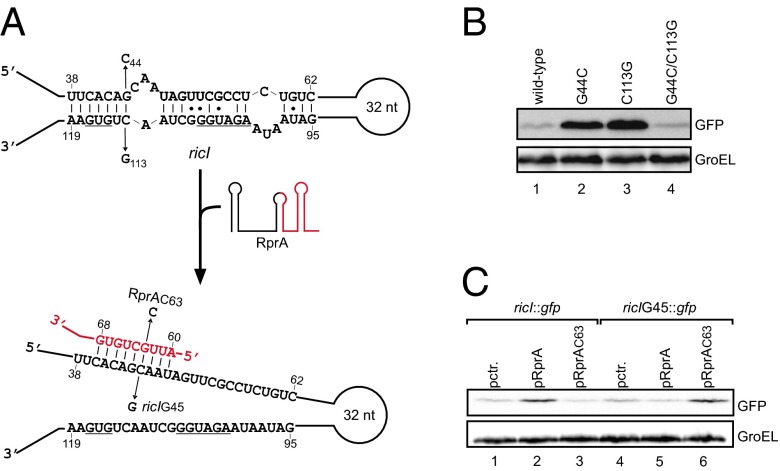

A Second Seed Region in RprA Activates RicI Synthesis.

Next, we sought to understand how RprA activates RicI production. As our pulse expression approach suggested posttranscriptional control, we looked for evidence of activation by the aforementioned “anti-antisense” mechanism (12), whereby the sRNA opens a self-inhibitory structure in the 5′-UTR of its target mRNA (21). Indeed, in silico analysis of the secondary structure of the ricI mRNA (from the transcriptional start site to the fifth codon; see below) using the Mfold algorithm (38) predicted a discontinued RNA duplex formed between nucleotides 38–62 and 95–119 (relative to the transcriptional start site; see below) of the ricI mRNA (Fig. 2A). This structure would sequester the Shine–Dalgarno sequence (SD) and the GUG translation start codon of ricI.

Fig. 2.

Anti-antisense activation of ricI. (A) Graphical presentation of the ricI 5′-UTR alone (Top) or in complex with RprA (Bottom). Numbering of ricI and RprA is relative to their transcription start site. ricI base pairs with the 5′ terminal end of the processed RprA form. Arrows denote mutations introduced in ricI::gfp and RprA, respectively. (B) Western blot analysis of ricI::gfp variants (as indicated in A, Top) expressed in Salmonella ΔrprA cells. (C) Western blot analysis of ΔrprA Salmonella harboring plasmid pRprA or mutant plasmid, pRprAC63, in combination with either wild-type ricI::gfp or mutant ricIG45::gfp fusion plasmids. GroEL served as loading control.

To validate this predicted hairpin and its potential function in translation control, we cloned the sequence of the ricI mRNA—from its transcriptional start site to the 10th codon—into a gfp-based reporter plasmid designed to report posttranscriptional regulation (39). This construct gave only modest GFP expression. However, when we truncated the ricI mRNA at its 5′ end (transcription start at A48; Fig. S1A), essentially deleting the sequence predicted to sequester the translational start site, a >50-fold increase in the level of RicI::GFP was observed (Fig. S1B). Moreover, a single C→G change opposite the first nucleotide of the start codon (42 nt downstream of the transcriptional start site; see below) increased the expression of the full-length reporter ∼13-fold (Fig. S1B). In further support of our model that a 5′ hairpin sequesters the ricI start codon, two other mutations, G44→C or C113→G (Fig. 2 A and B, compare lane 1 vs. 2 and 3), also increased RicI::GFP synthesis. As expected, however, the combination of these two latter mutations restored wild-type expression levels of RicI::GFP, most likely by restoring mRNA hairpin formation. Together, this mutational analysis suggests that RicI synthesis is intrinsically repressed by intramolecular base pairing in the 5′ region of its mRNA.

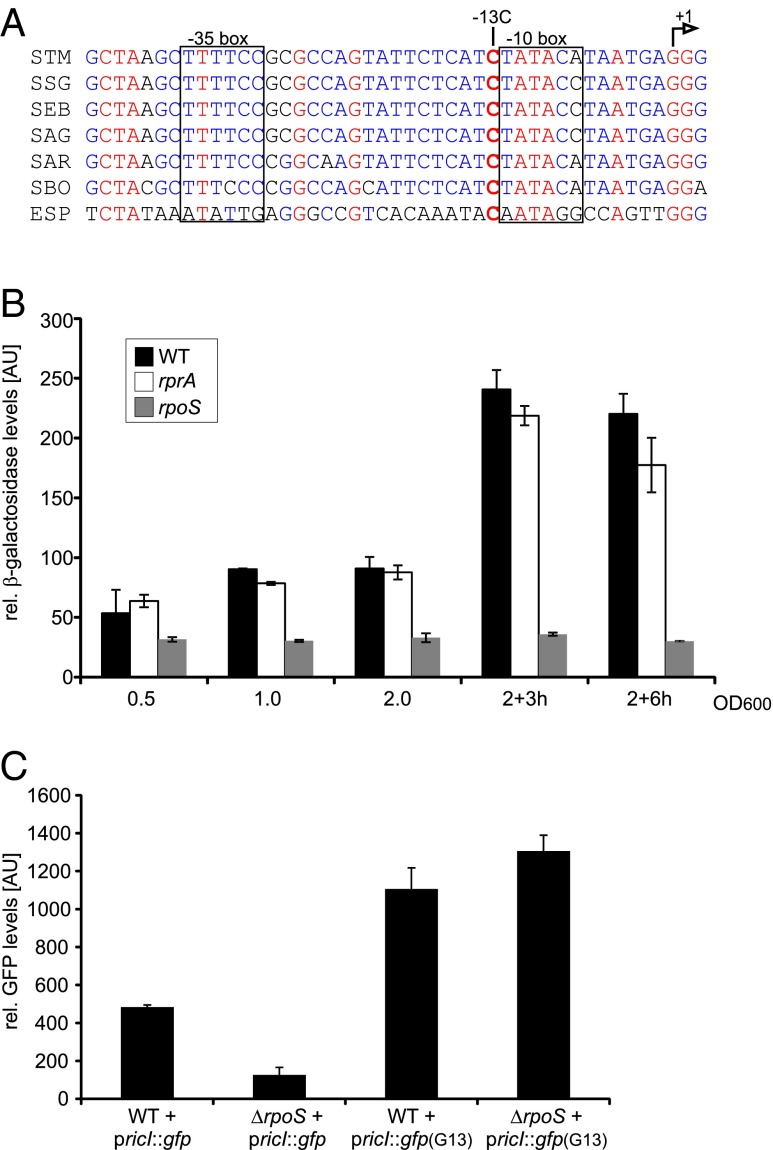

Fig. S1.

Posttranscriptional control of ricI. (A) Secondary structure of the ricI 5′-UTR. Truncations and mutations tested in B are indicated by arrows. The SD sequence and the start codon are underlined. (B) Salmonella ΔrprA cells carrying the indicated ricI::gfp variants were tested for GFP production by Western blot. (C) Salmonella carrying a GFP control plasmid (pXG-1) were cotransformed with a control plasmid (pctr.) or a RprA overexpression plasmid (pRprA) and tested by Western blot for GFP production. (D) Salmonella carrying the truncated ricI::gfp plasmid (pKP130; A) were cotransformed with a control plasmid (pctr.) or a RprA overexpression plasmid (pRprA) and tested by Western blot for GFP production. (E) Salmonella carrying the mutated ricI::gfp plasmid (pKP138; A) were cotransformed with a control plasmid (pctr.) or a RprA overexpression plasmid (pRprA) and tested by Western blot for GFP production. (B–E) GroEL served as loading control.

Next, we used the ricI::gfp reporter to establish that RprA activates translation of this target by preventing self-sequestration of the ricI mRNA. Indeed, coexpression of RprA from a compatible plasmid increased RicI::GFP levels by approximately threefold (Fig. 2C, lane 1 vs. 2), whereas it had no effect on GFP levels expressed from the pXG-1 control plasmid (Fig. S1C) (39). As expected if RprA acted by suppressing hairpin formation, the sRNA had no effect on the truncated (Fig. S1D) or “open” (C42→G) variants of ricI::gfp (Fig. S1E).

Because the processed RprA form sufficed for activation (Fig. 1 C and D), we used its sequence to search for an RprA binding site in the 5′-UTR of ricI. The RNA-hybrid algorithm (40) predicted a consecutive stretch of nine Watson–Crick base pairs formed between the proximal end of the processed RprA and the internal antisense element of the ricI mRNA (Fig. 2A). To test this prediction, we constructed an RprA variant with a point mutation in the seed region (G63→C, Fig. 2A); as expected, RprAC63 was unable to activate the ricI::gfp reporter (Fig. 2C, lane 3). Conversely, mutating the corresponding position 45 in the ricI 5′-UTR (ricIG45::gfp reporter, Fig. 2A) abrogated reporter activation by wild-type RprA (Fig. 2C; lane 5). Note that this nucleotide is not paired in the intrinsic hairpin and hence will not alter RicI::GFP expression (Fig. 2C; lane 1 vs. 4). By contrast, combining both mutants (RprAC63 and ricIG45::gfp) fully restored target activation (Fig. 2C; lane 6). Thus, RprA uses a similar mechanism but different seed sequences to activate the synthesis of σS and RicI.

Membrane Stress and the Rcs Phosphorelay Activate RicI Production.

The ricI gene (also known as STM4242) is conserved in all sequenced Salmonella species, including the ancestral Salmonella bongori and the human-specific serovar Salmonella typhi, but absent in other enterobacterial relatives such as E. coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Shigella flexneri (Fig. S2). Although its biological role has not been investigated, RicI has been reported as a bile salt-induced protein (41). To address this, we monitored production of 3×FLAG-tagged RicI protein in both wild-type and ΔrprA cells upon exposure to bile. In Salmonella wild-type cells, RicI levels increased approximately fourfold within 15 min after treatment, with a further increase to approximately eightfold after 120 min (Fig. 3A, lanes 1–5). By contrast, the ΔrprA mutant failed to increase RicI production (Fig. 3A, lanes 6–10). These results confirm bile as a potent activator of RicI production but also implicate RprA as an essential factor in this process.

Fig. S2.

Gene synteny analysis of ricI. The genomic regions upstream and downstream of ricI (STM4242) from related enterobacteria were inspected for sequence conservation (ECO, Escherichia coli K12; KPN, Klebsiella pneumoniae; SFL, Shigella flexneri; SL1344, Salmonella enterica sv. Typhimurium SL1344; STM, Salmonella enterica sv. Typhimurium LT2; STY, Salmonella typhi CT18). Coloring refers to the GC content of the individual genes.

Fig. 3.

Bile-induced expression of RicI. (A) Western blot analysis of RicI::3×FLAG expression. Wild-type and ΔrprA cells were grown to late exponential phase (OD600 of 1.0) and treated with bile salts (3% final concentration). Whole-protein samples were collected at the indicated time points and probed for RicI::3×FLAG production. (B) Wild-type and the indicated Salmonella mutants (ΔrprA, ΔrcsF, ΔrcsC, ΔrcsB, and ΔrpoS) were cultivated in LB media (with or without 3% bile salts) to OD600 of 1.0 and probed for bile-mediated activation of RicI::3×FLAG (Western blot) and RprA (Northern blot). (C) RicI::3×FLAG production in the context of RprA overexpression. Wild-type, ΔrprA, ΔrcsB, and ΔrpoS cells transformed with a control plasmid (pctr.) or the RprA overexpression plasmid (pRprA) were tested for RicI::3×FLAG expression on Western blot.

Bile is a detergent-like substance that can disrupt bacterial membranes (42) and thereby activate the Rcs stress response. Because the Rcs system strongly induces the rprA promoter in E. coli (21), and other cell envelope-damaging conditions trigger RprA synthesis through RcsB (21, 43–45), we hypothesized that the bile-induced increase in RicI synthesis is indirect, resulting from the Rcs-mediated activation of RprA. To test this, we constructed single-gene deletion strains of various components of the Rcs signaling cascade and evaluated bile-induced changes in the levels of RprA and RicI levels in these mutants. As expected, wild-type cells activated both RprA and RicI expression in the presence of bile (Fig. 3B, lane 1 vs. 2), whereas cells lacking rprA (lanes 3 and 4), rcsF (lanes 5 and 6), or rcsB (lanes 9 and 10) failed to activate RicI. This corresponded well with a loss of bile-induced activation of RprA in the ΔrcsB and ΔrcsF mutants, with the ΔrcsC mutant showing intermediate RprA induction that seemed insufficient for RicI activation (lanes 7 and 8). Given the known relationship of RprA and σS, we also tested a ΔrpoS strain. Surprisingly, bile did not increase RicI levels in the ΔrpoS strain, although RprA was fully activated (Fig. 3B, lanes 11 and 12). This suggested that also σS was essential for RicI activation but it would act downstream of RprA.

To better understand the role of σS in RicI activation, we sought to override Rcs signal transduction by constitutive expression of RprA (from plasmid pKP-112) in the rprA, rcsB, and rpoS mutant strains. Midexponential cultures (low endogenous RprA expression; Fig. 1B) were probed for RicI production (Fig. 3C). In support of our previous results, plasmid-borne overexpression of RprA strongly induced RicI expression in wild-type cells and complemented the rprA and rcsB mutant strains (Fig. 3C, lanes 1–6). However, RicI levels remained low in the ΔrpoS mutant, suggesting that the function of σS was independent of RprA-mediated posttranscriptional activation of ricI mRNA.

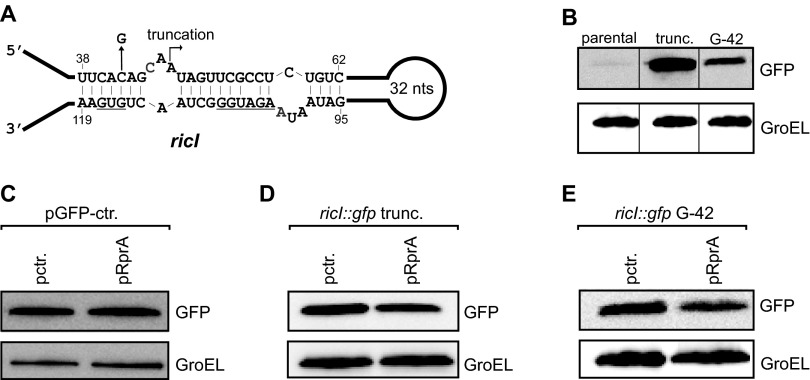

σS Is Required for Transcription of ricI.

To further address the requirement of σS for RicI synthesis, we tested whether RprA activated the ricI::gfp reporter (Fig. 2B, lane 1) in the ΔrpoS mutant strain. The ricI::gfp reporter gene is transcribed from a constitutive PLtetO promoter that is insensitive to absence of σS. There was no difference to the previously observed approximately threefold activation in wild-type Salmonella (Fig. S3A), suggesting that σS influences RicI expression at an earlier step, i.e., transcription.

Fig. S3.

Role of σS for ricI expression. (A) Same as Fig. 2C (lanes 1 and 2), but RicI::GFP expression was monitored in a Salmonella ΔrpoS strain. (B) 5′-RACE analysis of the ricI transcriptional start site. C, control (genomic DNA); M, DNA size marker; T−, no TAP treatment; T+, TAP-treated samples.

The transcriptional start site of ricI, mapped here by 5′-RACE (Fig. S3B) and previously by global dRNA-seq analysis of the Salmonella transcriptome (46), is a guanine that lies 114 nt upstream of the start codon (Fig. 4A). Intriguingly, the associated promoter contains a highly conserved cytosine at position −13, which is a hallmark of σS-dependent promoters; this nucleotide contacts amino acid E458 in σS and counterselects for binding of the housekeeping σ70 (47). To test a potential σS dependence of the ricI promoter, we inserted a lacZ reporter gene downstream of it in the Salmonella chromosome (48). Promoter activity assays in the wild-type and in a ΔrprA mutant revealed comparable transcriptional activity of the two strains with peaking activity under stationary-phase growth conditions (Fig. 4B). In contrast, Salmonella lacking the rpoS gene failed to activate the ricI promoter under all conditions tested, indicating that σS controls ricI transcription.

Fig. 4.

σS activates ricI transcription. (A) Alignment of the ricI promoter sequence from Salmonellae and Enterobacter species (ESP, Enterobacter sp. 638; SAG, S. enterica sv. Agona; SAR, S. enterica sv. arizonae; SBO, Salmonella bongori; SEB, S. enterica sv. Bovismorbificans; SSG, S. enterica sv. Schwarzengrund; STM, S. enterica sv. Typhimurium). Transcription control regions −10 and −35 are boxed, and the transcription initiation (+1) site is marked by an arrow. Residue C-13 is shown in bold. (B) Wild-type, ΔrprA, and ΔrpoS cells carrying the transcriptional ricI::lacZ reporter were monitored for β-galactosidase production at the indicated stages of growth. (C) Wild-type and ΔrpoS cells transformed with either a wild-type (pricI::gfp) or the mutant [pricI::gfp (G13)] reporter were cultivated to early stationary phase (OD600 of 2.0) and assayed for GFP production.

This was further confirmed by mutating C-13, which eliminated the σS dependency of ricI transcription as expected; i.e., a gfp reporter gene fused to a C-13→G variant of the ricI promoter was insensitive to the presence or absence of an intact rpoS gene (Fig. 4C). Collectively, these results suggest that both transcriptional activation by σS and posttranscriptional activation by RprA are essential for ricI expression.

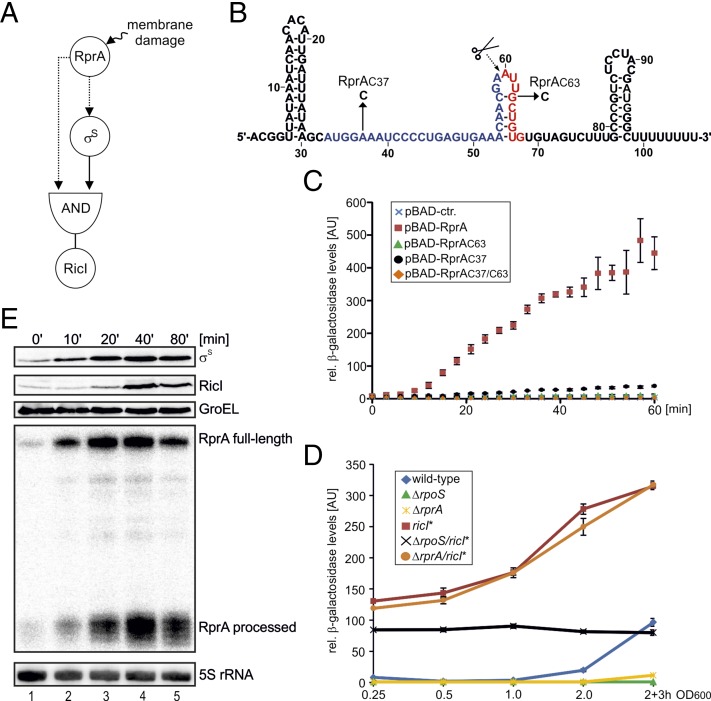

An RNA-Controlled FFL with AND-Gate Logic Regulates RicI Production.

The dual requirement of RprA and σS in the activation of RicI resembles a coherent type 1 FFL (49). However, whereas such FFLs are typically controlled by transcription factors, the type 1 FFL activating RicI depends on dual base-pairing interactions of a regulatory RNA, which we predicted to work through an AND-gate logic: the up-regulation of RicI synthesis requires both σS and RprA (Fig. 5A).

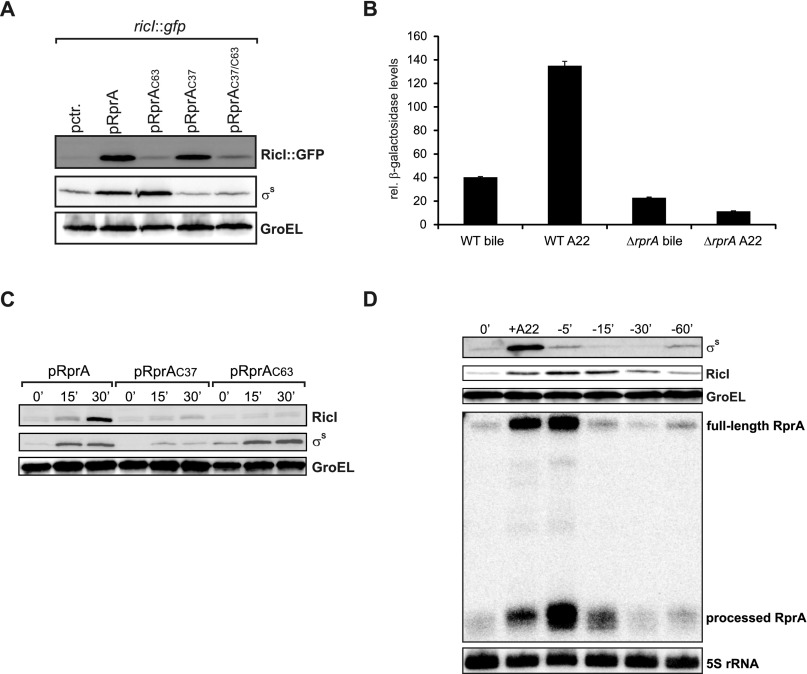

Fig. 5.

An FFL with AND-gate logic controls RicI production. (A) Schematic display of the FFL regulating RicI production. Both RprA and σS are required for RicI expression. Dashed lines indicated posttranscriptional regulation, and solid lines denote control at the transcriptional level. (B) Secondary structure of RprA. Mutations tested in C are indicated by arrows. Scissors mark the RprA processing site. (C) Salmonella carrying the translational ricI::lacZ reporter were transformed with the indicated plasmids and tested for β-galactosidase production upon induction of pBAD expression. (D) The indicated strains (wild type, ΔrpoS, ΔrprA, ΔricI*, ΔrpoS/ricI*, and ΔrprA/ricI*) carrying the translational ricI::lacZ reporter were assayed for β-galactosidase production at the indicated time points of growth. (E) Analyses of σS, RicI::3×FLAG, and RprA expression after A22-mediated induction of the Rcs pathways. Samples were collected at the indicated time points and probed for σS and RicI::3×FLAG (Western blot) as well as RprA (Northern blot) production. GroEL and 5S rRNA served as loading controls.

To examine the effectivity of this regulatory scheme, we mutated the rprA gene at two positions (Fig. 5B): we changed adenosine 37 to cytosine (RprAC37) abolishing activation of the rpoS mRNA (21), and guanine 63 to cytosine (RprAC63) to abrogate activation of the ricI mRNA (Fig. 2 A and C). These mutant rprA alleles were expressed from an inducible pBAD promoter to test their ability to up-regulate a chromosomal ricI::lacZ translational reporter under the control of the endogenous ricI promoter. Induction of wild-type RprA resulted in a >50-fold increase in reporter activity over the course of 60 min (Fig. 5C). By contrast, neither the RprAC63 nor the RprAC37/C63 double mutant could activate the reporter (Fig. 5C). Likewise, the RprAC37 single mutant, which fully activates the posttranscriptional ricI::gfp reporter (Fig. S4A), failed to activate the translational ricI::lacZ reporter (Fig. 5C). To further test this scheme, we treated ΔrprA cells carrying either the rprA, rprAC37, or rprAC63 allele (on a low-copy plasmid) with 3,4-dichlorobenzyl carbamimidothioate (A22) and followed the kinetics of RprA, σS, and RicI production. A22 inhibits the actin-like MreB protein and provides superior activation of the Rcs phosphorelay compared with bile salts (Fig. S4B) (45, 50). As expected from our previous results (Fig. 5C), only wild-type RprA provided full induction of RicI and σS, whereas RprAC63 failed to activate RicI and RprAC37 displayed only reduced σS induction and did not up-regulate RicI (Fig. S4C). Together, these data indicate that RprA acts in a sequential order: activation of rpoS precedes activation of ricI because σS must activate ricI transcription first.

Fig. S4.

Dual control of ricI expression. (A) Salmonella ΔrprA cells carrying the ricI::gfp reporter and cotransformed with the indicated plasmids (Fig. 5B) were grown to early stationary phase and tested for RicI::GFP and σS production by Western blot. GroEL served as loading control. (B) Wild-type and ΔrprA cells carrying the translational ricI::lacZ reporter were cultivated to early stationary phase and tested for β-galactosidase production in the presence of bile salts or A22. (C) Western blot analyses of σS and RicI::3×FLAG production in ΔrprA cells (transformed with a low-copy plasmid carrying either the rprA, rprAC37, or rprAC63 allele) after A22 treatment. GroEL served as loading controls. (D) Analyses of σS, RicI::3×FLAG, and RprA production following activation and deactivation of the Rcs pathway using A22. Samples were collected at the indicated time points and probed for σS and RicI::3×FLAG (Western blot) as well as RprA (Northern blot) production. GroEL and 5S rRNA served as loading controls.

To test this circuit under more physiological conditions, i.e., without RprA overexpression, we monitored expression of a ricI::lacZ fusion at various stages of Salmonella growth. In wild-type cells, reporter activity peaked in stationary phase after increasing ∼12-fold from exponential phase (Fig. 5D). As expected, introduction of either a ΔrpoS or a ΔrprA allele abrogated this increase in RicI::LacZ levels. To uncouple transcriptional activity of σS from posttranscriptional regulation by RprA, we introduced the mutation G44→C (Fig. 2A) in the ricI 5′-UTR (ricI*) on the Salmonella chromosome. This “ON” mutation interferes with stem-loop formation of the ricI untranslated leader, resulting in high RicI::GFP production in the absence of RprA (Fig. 2B). Similarly, this mutation induced RicI::LacZ expression by ∼16-fold at early stages of growth (Fig. 5D) and rendered reporter activity insensitive to a secondary deletion of the rprA gene, because translation is already derepressed. Introduction of the ricI* allele into a rpoS mutant also increased RicI::LacZ production at early stages of growth but failed to increase expression at higher cell densities (Fig. 5D). These results support the combinatorial activity (AND-function) of σS and RprA in activation of RicI.

A key characteristic of type 1 FFLs is their delay function upon signal perception (51). This is easy to understand in the context of RprA, σS, and RicI: RprA has to activate rpoS until sufficient σS is produced to generate the ricI mRNA serving as a second target for RprA. To investigate whether production of σS precedes RicI expression, we treated cells with A22 and followed the kinetics of RprA, σS, and RicI production. As predicted from the circuit (Fig. 5A), we detected approximately fourfold elevated σS expression already 10 min after addition of A22 (Fig. 5E, lane 1 vs. 2), and production increased further to approximately eightfold after 80 min when the experiment was terminated (lane 5). Induction of σS occurred synchronously to RprA, indicating immediate posttranscriptional activation of the rpoS mRNA. By contrast, a cross-comparison of σS and RicI levels showed that RicI production was significantly delayed. RicI levels increased ∼2.5-fold after 20 min of treatment and increased afterward to ∼15-fold (Fig. 5E, lanes 1, 3, and 5). Using a similar approach, we also monitored expression of RprA, RicI, and σS following deactivation of the circuit. Specifically, we treated wild-type cells with A22 for 30 min and collected and washed the cells followed by reinoculation into fresh media. We discovered that shutoff of σS production is almost immediate, whereas reduction of RicI expression to “prestress” levels required ∼60 min (Fig. S4D). These differences in protein levels might depend on specific proteolytic factors targeting the σS protein (50). Interestingly, we found that σS degradation also preceded inhibition of RprA expression: expression levels of full-length RprA and processed RprA reached the prestress status ∼15 min after cells were reinoculated in fresh media. Together, our data provide evidence for a previously unidentified variant of the type 1 FFL network that functions through the regulatory activity of two base-pairing domains of a single sRNA. Deactivation of the circuits depends on the individual stabilities of the three components, with RicI being most stable and σS showing almost immediate degradation once the stress is removed.

RicI Inhibits Salmonella Virulence Plasmid Transfer.

The RprA-mediated up-regulation of RicI and the evident connection with the σS stress response network prompted us to investigate the biological role of these three factors more closely. Although the biological function of RicI was unknown, BLAST-P searches suggested similarity of RicI to a variety of proteins from different bacterial genera (Fig. S5), most of which with candidate functions in plasmid conjugation.

Fig. S5.

Alignment of RicI protein sequences. The protein sequences of homologs of the RicI protein from various bacterial species were aligned (E22, Escherichia coli E22; ECA, Erwinia carotovora; ESP, Enterobacter sp. 638; ESA, Enterobacter sakazakii; PIN, Psychromonas ingrahamii; R64, Escherichia coli O26:H11; SEN, Salmonella enterica sv. Newport; SPU, Shewanella putrefaciens; STM, Salmonella enterica sv. Typhimurium LT2; SWO, Shewanella woodyi; VCO, Vibrio cholerae; VFI, Vibrio fischeri; VSH, Vibrio shiloni; VSP, Vibrio splendidus).

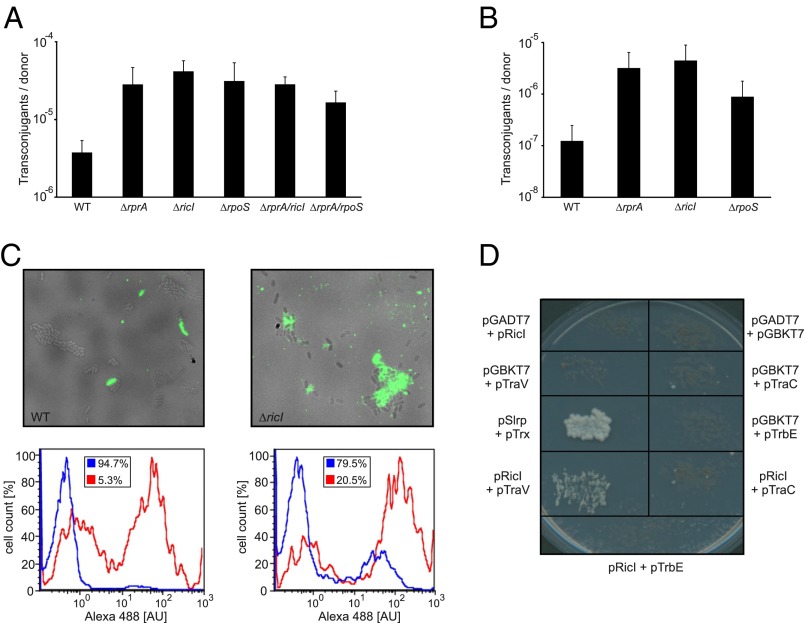

To investigate a potential role of RprA-mediated RicI activation in conjugation of the pSLT virulence plasmid in Salmonella, we compared the plasmid transfer rates of ΔrprA, ΔricI, and ΔrpoS donors with the transfer rate of the wild type. Deletions of ΔrprA, ΔricI, or ΔrpoS increased plasmid conjugation ∼8- to 11-fold (Fig. 6A, bars 1–4), suggesting an inhibitory function for RicI in pSLT transfer. Double mutants ΔrprA ΔricI and ΔrprA ΔrpoS yielded conjugation rates similar to those of the single-mutant variants (Fig. 6A), suggesting that RprA, RicI, and σS act in the same biological pathway to inhibit pSLT transfer.

Fig. 6.

RicI inhibits pSLT conjugation in Salmonella. (A) Conjugation rates of the pSLT plasmid in the indicated donor strains. (B) Same as A but conjugation was tested in the presence of 4% bile salts. (C, Top) Alexa 488-labeled R17 bacteriophage was used to visualize the pSLT conjugation pili in wild-type and ΔricI cells. (Bottom) Quantification of labeled wild-type and ΔricI cells using FACS analysis. Flow cytometry analysis of Alexa 488 fluorescence intensity and percentages of cells that do not show R17 binding (blue) and cells exhibiting R17 binding (red). Histograms represent the percentages of fluorescent (R17-bound) and nonfluorescent cells. (D) Yeast two-hybrid assays of RicI–TraV interaction. Combination of RicI and TraV fusion proteins restores growth of yeast cells on selective medium, whereas expression of the individual fusion proteins (in combination with the control plasmids pGBKT7 or pGADT7) is insufficient. SlrP-Trx provided a positive control (74), and the negative controls were RicI/TraC and RicI/TrbE.

Bile salts are an important factor for Salmonella pathogenicity (52) and have been reported to decrease pSLT transfer (9, 10). Because RprA expression is induced by bile (Fig. 3B), we wondered whether bile salts could affect conjugation frequency through RprA, σS, and RicI. To test this hypothesis, we compared conjugation rates of wild type, ΔrprA, ΔricI, and ΔrpoS mutants in the presence of 4% bile. As expected, bile strongly decreased conjugal transfer from wild-type donors (compare Fig. 6 A and B). However, under the same conditions, ΔrprA, ΔricI, or ΔrpoS donors displayed up to ∼36-fold (ΔricI) increased conjugation rates (Fig. 6B), similar to those of wild-type strains grown in rich medium (Fig. 6A). These data indicate a restrictive role for RicI during Salmonella virulence plasmid conjugation under membrane stress conditions.

Next, we sought to understand how RicI controls pSLT transfer. We first tested whether increased pSLT transfer of ΔricI Salmonella was also reflected in a higher rate of F-pili production. To this end, we treated cells with a fluorescently labeled derivative of bacteriophage R17. R17 specifically binds F-like pili and allows for accurate quantification of pili assembly (53). We used flow cytometry to compare pSLT-encoded F-like pili production in wild-type and ΔricI cells. Approximately 5% of wild-type cells displayed F-like pili on their surface, whereas this frequency was increased to >20% in ΔricI mutants (Fig. 6C). These data indicate that RicI inhibits production of pSLT-encoded pili and suggests that the increased conjugation rates of ΔricI mutants (Fig. 6 A and B) might be a consequence of increased F-like pili formation.

To investigate the gene-regulatory pattern underlying these phenotypes, we tested whether RicI affected expression of traJ. In F-family plasmids, TraJ is the major transcriptional activator of the tra operon encoding most of the proteins necessary for conjugation (54). Therefore, elevated expression of TraJ could well explain the increased F-pili production of ΔricI cells (Fig. 6C). However, expression of the transcriptional reporters traJ::lacZ and traB::lacZ [activated by TraJ (7)] remained unchanged in the ricI mutant, whereas levels of both reporters (Fig. S6 A and B) were significantly increased in dam-deficient cells, which served as a positive control (8). These data indicate that RicI inhibits plasmid transfer through a mechanism independent of TraJ.

Fig. S6.

Role of RicI in pSLT transfer. (A) Production of β-galactosidase from a traJ::lacZ reporter in wild-type, ΔricI, and Δdam cells. (B) Same as A, but activity of a traB::lacZ reporter was tested. (C) Fractionation of Salmonella cells producing the RicI::3×FLAG protein. RicI::3×FLAG, Lon, Dam, and TraT proteins were detected by Western blot using specific antibodies. (D) Silver staining of coimmunoprecipitated proteins using RicI::3×FLAG protein as bait. The PtetO-ricI::3×FLAG strain expresses the RicI::3×FLAG protein from the constitutive ptetO promoter. TraV and three additional proteins (STM14_0317, YhjJ, and StbA) coimmunoprecitated with RicI are indicated by arrows. Untagged (no FLAG epitope) Salmonella wild-type cells served as negative control. M, protein size marker.

Cell fractionation assays showed that RicI localizes to the inner membrane or periplasm of Salmonella (Fig. S6C), suggesting that RicI does not act at the gene-regulatory level but rather through interaction with other proteins. To identify interaction partners of RicI, we performed protein coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP) experiments in lysates of Salmonella expressing RicI::3×FLAG. Visualization of copurified protein by silver staining revealed enrichment of a small protein (∼18 kDa) in cells expressing the RicI::3×FLAG protein, compared with co-IP in wild-type cells used for control (Fig. S6D). Mass spectrometry identified this protein as TraV, which is a membrane-bound lipoprotein that functions as an anchor of the type IV secretion apparatus (55). To validate the predicted interaction of RicI and TraV, we made use of a yeast-two-hybrid system in which reconstitution of the GAL4 protein through two interacting protein partners is required to drive the expression of the HIS3 and ADE2 genes, which are required for cellular growth (56). Indeed, we observed that plasmid-borne expression of neither RicI nor TraV fusion proteins alone would allow growth on selective plates, whereas combination of the two would restore HIS3 and ADE2 expression (Fig. 6D). Together, our data indicate that the RprA-activated RicI protein inhibits F-pili production through an interaction with TraV.

Discussion

Studies aimed at understanding the interplay of regulatory factors have identified recurring patterns called network motifs (51). Typically, these network motifs are composed of two hierarchically acting transcription factors, but an increasing number of examples suggest that sRNAs can be integral parts of similar regulatory circuits (57, 58). One of the most common network motifs is the FFL wherein one regulator controls another regulator, which both regulate the expression of a third gene (59). When both regulators act in concert, the loop architecture is coherent, whereas opposing regulatory functions define an incoherent FFL (49). In this study, we describe a regulatory circuit paralleling a transcription factor-driven coherent FFL; however, in this arrangement, the RprA sRNA replaces the top-tier transcriptional regulator. RprA acts posttranscriptionally to activate two transcripts: the rpoS mRNA encoding the general stress sigma-factor σS, and the σS-controlled ricI mRNA encoding a membrane-associated protein (Fig. 5A). This FFL functions as a regulatory AND-gate whereby both regulators, RprA and σS, are essential for ricI activation (Fig. 5 C and D).

The AND-gate logic of this FFL has important implications for the regulatory dynamics of the circuit. For example, although the rpoS and ricI mRNAs are both activated through the same sRNA, production of RicI protein significantly lags the synthesis of σS (Fig. 5E). This regulatory pattern is also biologically relevant, allowing the FFLs to act as a “persistence detector” (59) in which only sustained activation of RprA, leading to accumulation of σS above the critical threshold required for ricI transcription, will trigger the FFL. In addition, the system can swiftly respond to OFF-pulses (Fig. S4D) as inhibition of either RprA or σS will terminate ricI activation.

Other bacterial sRNAs have been documented to be part of FFLs with globally acting transcription factors (60, 61). For example, the Spot 42 sRNA is repressed by the global regulator CRP and itself inhibits the translation of many CRP-dependent mRNAs (60). This multioutput FFL facilitates carbon source transition and minimizes leaky gene expression under steady-state conditions (60, 62). Both Spot 42 and RprA are components of coherent FFLs, and both regulate gene expression through direct base pairing with target mRNAs. However, the regulatory functions of the two sRNAs are conceptually different: Spot 42 serves as an accelerating factor in the regulation of CRP target genes (60), whereas RprA is strictly required for RicI production (Figs. 3A and 5D). In other words, repression of CRP-target genes by Spot 42 creates a regulatory OR-gate, whereas activation of RicI through RprA and σS establishes an AND-gate function.

Unlike Spot 42 and most other characterized sRNAs, which exist as a single transcript, RprA is a processed sRNA with two independent seed-pairing domains. The proximal domain base pairs with rpoS mRNA, whereas the distal domain targets ricI mRNA (Fig. 5B). Importantly, the two forms of RprA have different stabilities: the full-length RprA is cleaved by RNase E and relatively short-lived, whereas the processed RprA is more stable (31, 34). We predict the different stabilities of the two RprA forms to have important implications for the regulatory dynamics of the FFL. On one hand, the rapid turnover rate of full-length RprA might function as a timed “erase function” for the system that will eliminate information from previous signal transduction events. On the other hand, the higher stability of processed RprA will allow activation of ricI independent of full-length RprA, given that σS production is activated through an alternative pathway. Indeed, expression of processed RprA alone can be sufficient to activate RicI production in stationary-phase cells when σS is present (Fig. 1D).

Why does Salmonella limit pSLT transfer when the membrane is damaged? Despite the potential benefit of plasmid transfer at the population level, assembly of the conjugation pilus is a burden for individual donor cells and requires tight control, especially under stress conditions. In fact, synthesis of F-like pili causes bile sensitivity in E. coli (63) and bile inhibits transfer of pSLT, the Salmonella virulence plasmid (10). Synthesis of RicI inhibits conjugal transfer of pSLT (Fig. 6A), and rationalizing from its interaction with the pSLT-encoded periplasmic protein TraV (Fig. 6D), RicI is likely to directly interfere with pilus assembly (Fig. 7). This view is supported by our observation that adsorption of phage R17 occurs at reduced levels upon RicI production (Fig. 6C). Bile salts are bactericidal (64), and the RicI protein may provide a safety device that protects Salmonella from the danger of conjugation apparatus assembly when envelope integrity is in jeopardy. Since synthesis of both RprA and RpoS is activated in the presence of bile, inhibition of pilus formation might protect Salmonella against the membrane-damaging activities of bile salts and down-regulate the energy-intensive assembly of transenvelope machineries such as the conjugation apparatus. Interestingly, the CpxAR pathway has been shown to fulfill an analogous function in enteropathogenic E. coli: CpxAR-mediated activation of the protease–chaperone pair, HslVU, results in degradation of TraJ, the major transcriptional activator of plasmid transfer genes (65). Because all of these components are also conserved in Salmonella, the CpxAR and Rcs pathway might work in concert to control transfer of pSLT. In fact, two or more redundantly acting pathway could account for the residual inhibition of conjugation observed for bile-treated ΔrprA, ΔricI, or ΔrpoS donor cells (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 7.

Model of RicI-mediated conjugation inhibition in Salmonella. (Left) Under regular growth conditions (no membrane stress), the Rcs system is inactive and RprA is not produced. Therefore, RprA cannot activate rpoS and ricI will not be expressed. Expression and assembly of the pSLT conjugation apparatus is permitted. (Right) When the Rcs system is activated (e.g., by bile salts or A22), full-length RprA will activate the rpoS mRNA leading to σS production. σS activates the transcription of ricI, and the ricI mRNA can be activated by the processed RprA variant. Finally, RicI interacts with TraV to inhibit assembly of the pSLT conjugation pilus.

The regulatory AND-gate involving RprA illustrates how sRNAs can function as specialization devices in global regulons. E. coli and Salmonella control the production of σS at multiple levels (16, 17), and in turn σS controls a large regulon (66, 67). Nonetheless, even though a variety of environmental stresses activate σS production, not every of these stress conditions requires repression of plasmid transfer. The strict requirement for posttranscriptional activation of ricI through RprA ensures that conjugation is only inhibited when the membrane integrity is compromised and the Rcs or CpxAR pathways are activated. Other environmental factors activating σS independent of RprA will not affect RicI expression and plasmid transfer. In E. coli, a similar diversification of the σS regulon is present with csgD and ydaM: although σS activates these two genes for curli fiber and cellulose production, RprA represses their mRNAs (35, 68), suggesting that RprA promotes certain stress-related functions of the σS regulon but inhibits the functions of CsgD and YdaM.

Although our study has focused on understanding the activation of RicI synthesis by RprA, other putative RprA targets predicted here suggest additional roles for this sRNA in the control of pSLT-mediated functions. For example, our pulse expression results predict RprA to repress the pSLT-encoded traT mRNA (Fig. 1C). TraT belongs to the group of surface exclusion proteins, which block conjugative transfer of plasmids to cells bearing identical or closely related plasmids (69). Given that bile salts can induce curing of pSLT plasmid (10), repression of traT by RprA could allow the uptake of new plasmids. Other potential targets are the Salmonella-specific SL2594 and SL2705 loci from prophage regions. Similar to the repression of plasmid conjugation via RicI, RprA could inhibit the assembly of phage-derived structures under conditions of envelope stress. This regulatory pattern might further extend into virulence functions of Salmonella: invasion of the host cell epithelium requires a type 3 secretion system (T3SS) of virulence proteins into the host cell. The rtsA mRNA encodes an activator of this T3SS (70), and its repression by RprA (Fig. 1C) suggests that RprA inhibits the assembly of this T3 secretion apparatus when the bacterial envelope is damaged. The list of RprA targets also suggests additional regulatory circuits. For example, the yqaE gene is activated by CpxR (22) and RprA, which may constitute another FFL featuring both transcriptional and posttranscriptional control. For certain target candidates (e.g., guaA), we observed opposite regulation by both the full-length and processed RprA variants (Fig. 1C); the causes for such opposite regulations remain to be explored.

To our knowledge, RprA is the first processed sRNA controlling distinct sets of target mRNAs through two different isoforms (Fig. 1C), but additional work will be required to understand its regulatory full scope. We note that, of 64 potential RprA targets, 34 are predicted to be up-regulated (Fig. 1C). This number is unusually high compared with other well-characterized sRNAs, but it shrinks to a single activated target (ricI) when only the processed form of RprA is induced. This high number of activated genes could well result from the significant amount of σS protein that is produced even after short induction (15 min) of the full-length RprA sRNA (Fig. 1D). Indeed, cross-comparison with a recently published list of σS-dependent Salmonella genes (66) revealed that 22 of the 34 activated targets are regulated by σS; further experiments will tell which of these genes are directly regulated by σS, RprA, or both. This notwithstanding, our study suggests that the widely conserved RprA sRNA has a more complex biological role than previously anticipated.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains and Growth.

Bacterial strains and details on their construction are listed in Table S1. Strains were grown at 37 °C in Luria–Bertani (LB) broth or on LB plates. Ampicillin (100 µg/mL), kanamycin (50 µg/mL), chloramphenicol (20 µg/mL), and l-arabinose (0.2%) were added where appropriate. Salmonella wild-type (SL1344) or mutant strains were transformed by electroporation.

Table S1.

Bacterial strains used in this study

| Strain | Relevant markers/genotype | Reference/source |

| S. typhimurium | ||

| SL1344 | StrR hisG rpsL xyl | Ref. 83 |

| JVS-0159 | SL1344 ΔrprA::KmR | Ref. 33 |

| JVS-4065 | SL1344 ΔrprA::FRT | This study |

| JVS-4477 | SL1344 ΔricI::KmR | This study |

| JVS-3868 | SL1344 ricI::3×FLAG | This study |

| JVS-5487 | SL1344 ΔrpoS::CamR | Ref. 72 |

| JVS-3891 | SL1344 ΔrcsB::KmR | This study |

| JVS-4123 | SL1344 ΔrcsF::KmR | This study |

| JVS-4233 | SL1344 ΔrcsC::KmR | This study |

| JVS-3912 | SL1344 ricI::3×FLAG/ΔrprA | This study |

| JVS-3911 | SL1344 ricI::3×FLAG/ΔrcsB::KmR | This study |

| JVS-4155 | SL1344 ricI::3×FLAG/ΔrcsF::KmR | This study |

| JVS-4260 | SL1344 ricI::3×FLAG/ΔrcsC::KmR | This study |

| JVS-5483 | SL1344 PricI::lacZ | This study |

| JVS-5484 | SL1344 PricI::lacZ/ΔrprA | This study |

| JVS-5501 | SL1344 PricI::lacZ/ΔrpoS | This study |

| JVS-5486 | SL1344 ricI::lacZ | This study |

| JVS-5500 | SL1344 ricI::lacZ/ΔrpoS | This study |

| JVS-5485 | SL1344 ricI::lacZ/ΔrprA | This study |

| JVS-9879 | SL1344 ricI*::lacZ | This study |

| JVS-9880 | SL1344 ricI*::lacZ/ΔrpoS | This study |

| JVS-9882 | SL1344 ricI*::lacZ/ΔrprA | This study |

| JVS-4515 | SL1344 ΔrprA/ricI | This study |

| JVS-5587 | SL1344 ΔrpoS/ricI | This study |

| JVS-4861 | SL1344 PtetO-ricI::3×FLAG::CamR | This study |

| SV-5706 | ATCC 14028 spvA::KmR | Ref. 84 |

| SV-5799 | ATCC 14028 ΔrprA/spvA::KmR | This study |

| SV-5861 | ATCC 14028 ΔricI/spvA::KmR | This study |

| SV-5864 | ATCC 14028 rpoS::MudA/spvA::KmR | This study |

| SV-5865 | ATCC 14028 ΔrprA rpoS::MudA/spvA::KmR | This study |

| SV-5870 | ATCC 14028 ΔrprA ΔricI/spvA::KmR | This study |

| SV-4937 | ATCC 14028 trg::MudQ (CmR) pSLT– | Ref. 84 |

| E. coli | ||

| TOP10 | mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) Φ80lacZ ΔM15 ΔlacX74 deoR recA1 araD139 Δ(ara-leu)7697 galU galK rpsL endA1 nupG | Invitrogen |

| TOP10F′ | F′{lacIq Tn10 (TetR)} mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) Φ80lacZ ΔM15 ΔlacX74 deoR recA1 araD139 Δ(ara-leu)7697 galU galK rpsL endA1 nupG | Invitrogen |

| S. cerevisiae | ||

| Y2HGold | MATa, trp1–901, leu2–3, 112, ura3–52, his3–200, gal4Δ, gal80Δ, LYS2::GAL1UAS–Gal1TATA–His3,GAL2UAS–Gal2TATA–Ade2URA3:: MEL1UAS–Mel1TATA AUR1-C MEL1 | Clontech |

| Y187 | MATα, ura3–52, his3–200, ade2–101, trp1–901, leu2–3, 112, gal4Δ, gal80Δ, met–,URA3:: GAL1UAS–Gal1TATA–LacZ, MEL1 | Clontech |

Plasmids and Oligonucleotides.

Plasmids and DNA oligonucleotides are listed in Tables S2 and S3, respectively. Details on plasmid construction are provided in SI Materials and Methods. Target fusions to gfp were constructed as described previously (39).

Table S2.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid trivial name | Plasmid stock name | Relevant fragment | Comment | Origin, marker | Reference |

| pctr. | pJV300 | Control plasmid, expresses a ∼50-nt nonsense transcript. | ColE1, AmpR | Ref. 85 | |

| pBAD | pKP8-35 | pBAD control plasmid, expresses the same ∼50-nt nonsense RNA as pJV300 | pBR322, AmpR | Ref. 33 | |

| pBAD-RprA | pKP15 | RprA | RprA under the control of the inducible pBAD promotor | pBR322, AmpR | This study |

| pBAD-RprA proc. | pKP22 | RprA proc. | RprA proc. under the control of the inducible pBAD promotor | pBR322, AmpR | This study |

| pRprA | pKP112 | RprA | ColE1 plasmid, based on pZE12-luc, expresses RprA from a PLlacO promoter | ColE1, AmpR | This study |

| pRprAC63 | pKP141 | RprAC63 | Same as pKP-112 but carries a single-nucleotide exchange in the conserved 3′ end | ColE1, AmpR | This study |

| pBAD-RprAC37 | pKP198 | RprAC37 | Same as pKP-15 but carries a single-nucleotide exchange in 5′ end of RprA | pBR322, AmpR | This study |

| pBAD-RprAC63 | pKP199 | RprAC63 | Same as pKP-15 but carries a single-nucleotide exchange in 3′ end of RprA | pBR322, AmpR | This study |

| pBAD-RprAC63/C37 | pKP200 | RprAC63/C37 | Carries both mutations in rprA | pBR322, AmpR | This study |

| ricI::gfp | pKP114 | ricI 5′-UTR | GFP reporter plasmid. Carries the Salmonella ricI 5′-UTR and 30 bp of the ORF | pSC101*, CmR | This study |

| ricIG45::gfp | pKP150 | ricIG45 5′-UTR | Same as pKP-114 but carries a single-nucleotide mutation in the RprA interaction sequence | pSC101*, CmR | This study |

| ricI::gfp trunc. | pKP130 | ricI 5′-UTR | Truncated ricI 5′-UTR | pSC101*, CmR | This study |

| ricI::gfp G42 | pKP138 | ricI 5′-UTR | ricI::gfp reporter with single-nucleotide mutation at G42 | pSC101*, CmR | This study |

| ricI::gfp G44 | pKP225 | ricI 5′-UTR | ricI::gfp reporter with single-nucleotide mutation at G44 | pSC101*, CmR | This study |

| ricI::gfp C113 | pKP228 | ricI 5′-UTR | ricI::gfp reporter with single-nucleotide mutation at C113 | pSC101*, CmR | This study |

| ricI::gfp G44/C113 | pKP227 | ricI 5′-UTR | Carries both mutations in the ricI 5′-UTR | pSC101*, CmR | This study |

| pricI::gfp | pKP144 | ricI promoter | Transcriptional fusion of the ricI promoter to gfp | pBR322, CmR | This study |

| pricI::gfp (G13) | pKP247 | ricI promoter | ricI promoter with single-nucleotide mutation (C-13 to G) | pBR322, CmR | This study |

| pGFP-ctr. | pXG-1 | Control plasmid for GFP production | pSC101*, CmR | Ref. 39 | |

| pKD-3 | Template for CamR mutant construction | oriRγ, AmpR | Ref. 78 | ||

| pKD-4 | Template for KmR mutant construction | oriRγ, AmpR | Ref. 78 | ||

| pKD-13 | Template for in frame mutants construction | oriRγ, AmpR | Ref. 78 | ||

| pKD-46 | ParaB-γ-β-exo | Temperature-sensitive lambda red recombinase expression plasmid | oriR101, AmpR | Ref. 78 | |

| pCP20 | Temperature-sensitive FLP recombinase expression plasmid | oriR101, AmpR and CmR | Ref. 78 | ||

| pSUB11 | Template for construction of 3×FLAG-tag sequence linked to a KmR cassette | R6KoriV, AmpR | Ref. 80 | ||

| pCE40 | For FLP‐mediated lacZY integration to construct translational lac fusions | R6KoriV, KanR | Ref. 48 | ||

| pKG136 | For FLP‐mediated lacZY integration to construct transcriptional lac fusions | R6KoriV, KanR | Ref. 72 |

Table S3.

DNA oligonucleotides used in this study

| No. | Sequence | Description |

| JVO-0900 | GGAGAAACAGTAGAGAGTTGC | Plasmid construction |

| JVO-0901 | TTTTTTCTAGATTAAATCAGAACGCAGA | Plasmid construction |

| JVO-0907 | 5′P-ACGGTTATAAATCAACACATTG | Plasmid construction |

| JVO-0908 | TTTTTTCTAGATATCGCGGTGTTGAA | Plasmid construction |

| JVO-0922 | 5′P-ATTGCTGTGTGTAGTCTTTGC | Plasmid construction |

| PBADFW | ATGCCATAGCATTTTTATCC | Plasmid construction |

| PBADREV | TTATCAGACCGCTTCTGC | Plasmid construction |

| PLLACOB | CGCACTGACCGAATTCATTAA | Plasmid construction |

| PLLACOD | GTGCTCAGTATCTTGTTATCCG | Plasmid construction |

| JVO-3917 | AATTCCTGTGTGTAGTCTTTGC | Plasmid construction |

| JVO-3918 | ACAGGAATTCGTTGTTTCACT | Plasmid construction |

| JVO-3996 | TGGCAATCCCCTGAGTGA | Plasmid construction |

| JVO-3997 | ATTGCCATGCTTATAAATCAATGT | Plasmid construction |

| JVO-3643 | GTTTTATGCATGGGTCGATATTATAACAACAGG | Plasmid construction |

| JVO-3657 | GTTTTTGCTAGCAATCAGTGAAAGTTTGACGTTT | Plasmid construction |

| JVO-3044 | ATGCATGTGCTCAGTATCTCTATCAC | Plasmid construction |

| JVO-3790 | P∼ATAGTTCGCCTCTGTCCG | Plasmid construction |

| JVO-3898 | TTCAGAGCAATAGTTCGCC | Plasmid construction |

| JVO-3899 | TGCTCTGAAATAGTGATGTTAA | Plasmid construction |

| JVO-3900 | ACAGGAATAGTTCGCCTCT | Plasmid construction |

| JVO-3901 | TATTCCTGTGAAATAGTGATGTT | Plasmid construction |

| JVO 6578 | CTAAGTGTGAACAAAAACGTCA | Plasmid construction |

| JVO 6579 | CACACTTAGCCCATCTTATTATC | Plasmid construction |

| JVO 6580 | CACACCAATAGTTCGCCTC | Plasmid construction |

| JVO 6581 | ATTGGTGTGAAATAGTGATGTTAA | Plasmid construction |

| JVO-3979 | TTTTTTCCCGGGGCGTTGTGGTCTTTTCCAT | Plasmid construction |

| JVO-3980 | TTTTTTTCTAGACGAACTATTGCTGTGAAATAGTG | Plasmid construction |

| JVO-8687 | CTCATGTATACATAATGAGGGTC | Plasmid construction |

| JVO-8688 | GTATACATGAGAATACTGGCG | Plasmid construction |

| JVO-3985 | CCGGTAAAGCGTGGCGGAGGAATTACTTCACCTGATAATAGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC | Strain construction |

| JVO-3986 | ACGCTAAACCGGAGGCGTAGCGCCTCCGGTGAAAGCACCCCATATGAATATCCTCCTTAG | Strain construction |

| JVO-3627 | GCCTACGTCAAAAGCTTGCTGTAGCAAGGTAGCCCAATACGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC | Strain construction |

| JVO-3628 | ATAAGCGTAGCGCCATCAGGCTGGGTAACATAAAAGCGATGGTCCATATGAATATCCTCCTTAG | Strain construction |

| JVO-3857 | AAGCTCCTGATTCAATATCTGGCAATTAGAACATTCATTGGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC | Strain construction |

| JVO-3858 | AAACCGCCTGACGATAGCAGCCTGGCGTGCCGCTGGTAATCCATATGAATATCCTCCTTAG | Strain construction |

| JVO-3981 | TATCCGGCCCTTTTTCTTTGCCGTTGCGGGCTACGTCATTGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC | Strain construction |

| JVO-3982 | TTTTACAGGCCGGACAGGCGACGCCGCCATCCGGCATTTTCCATATGAATATCCTCCTTAG | Strain construction |

| JVO-3525 | TGAAACCTGGGGGGCAGGCGCGCAGCTTACAATGACATTCGACTACAAAGACCATGACGG | Strain construction |

| JVO-3526 | AGGGGCGTTACTATAGCATAACGCTAAACCGGAGGCGTAGCCATATGAATATCCTCCTTAG | Strain construction |

| JVO-6580 | CACACCAATAGTTCGCCTC | Strain construction |

| JVO-6581 | ATTGGTGTGAAATAGTGATGTTAA | Strain construction |

| JVO-8779 | CGCTGCGCGCAGAGTTTTTCAGCTTGCGCCAGTAACTCTTCCGTCTTACTGTCCCTAGTG | Strain construction |

| JVO-8780 | TACTCCGCTGCCATAATT | Strain construction |

| JVO-4383 | GACTCTGAAATTACCCCGCGACAATATATCGCCTGCTAAGAGTGCTTGGATTCTCACCA | Strain construction |

| JVO-4384 | AGGTGAAGTAATTCCTCCACCACGCTTTACCGGACAGAGGCTTTAATGAATTCGGTCAGTG | Strain construction |

| JVO-3529 | CAGTAACGCCGGATTTAATAGTA | 5′-RACE |

| JVO-4049 | GGGCAAAGACTACACACAGC | Probing RprA |

| JVO-0322 | CTACGGCGTTTCACTTCTGAGTTC | Probing 5S rRNA |

| STM4242-EcoRI-Fw | TTTTGAATTCGTGAACAAAAACGTCAAACTTTC | Y2H |

| STM4242-SalI-Rev | AAAAGTCGACTCAGAATGTCATTGTAAGCTGC | Y2H |

| TraV-pGADT7-Fw | TTTTGAATTCATGAACCGGATTTCATGCC | Y2H |

| TraV-pGADT7-Rev | AAAAGGATCCTTAATTAATCCGTGGCTTTCC | Y2H |

Sequences are given in 5′ → 3′ direction; 5′P denotes a 5′-monophosphate.

Western Blot Analysis, Fluorescence, and β-Galactosidase Assays.

Culture samples were taken according to 1 [OD600], centrifuged for 4 min at 16,000 × g at 4 °C, and pellets were resuspended in sample loading buffer to a final concentration of 0.01 OD/μL. Following denaturation for 5 min at 95 °C, 0.1 OD equivalents of sample were separated on SDS gels. Western blot analyses of σS, GFP, FLAG fusion proteins, and fluorescence assays followed published protocols (71). Quantitative Western blot data were obtained using a Fuji LAS-3000 imaging system (GE Healthcare), and band intensities were quantified using the AIDA software (Raytest). Probing for GroEL served as loading control. β-Galactosidase assays were performed as described before (72).

Northern Blot and Microarray Experiments.

Total RNA was prepared and separated in 5% or 6% (vol/vol) polyacrylamide–8.3 M urea gels (5–10 µg of RNA per lane) and blotted as described (73). Membranes were hybridized at 42 °C with gene-specific 32P–end-labeled DNA oligonucleotides in Rapid-hyb buffer (GE Healthcare). Microarray experiments were carried out as described before (33). Plasmids pKP15 and pKP22 allowed pulse expression of full-length and processed RprA, respectively. Microarray data have been deposited at GEO (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) (accession code GSE67187).

pSLT Conjugation Assays and R17 Phage Labeling.

Conjugation rates of pSLT plasmid were determined as described previously (10). Labeling of conjugation pili followed established protocols (53). For flow cytometry measurements, cells (20 μL) and R17 conjugated to Alexa 488 (5 μL) were mixed at room temperature for 60 min. Cells and bound bacteriophages were harvested by sedimentation for 4 min at 16,100 × g. Cell pellets were suspended in 1 mL of PBS. Fluorescent R17 was measured by flow cytometry. Data acquisition and analysis were performed using a Cytomics FC500-MPL cytometer (Beckman Coulter). Gates were drawn to separate cell showing high forward side (cells exhibiting R17 binding, higher cell size), and cells displaying low forward side (cells without R17 binding, smaller cell size). Alexa 488 fluorescence intensity was analyzed within the gates set as high or low forward side. Data were obtained and analyzed with MXP and FlowJo 8.7 software, respectively.

Yeast Two-Hybrid Assay.

Plasmids pIZ1872 (ricI) and pIZ1878 (traV) were transformed into strains Y2HGold and Y187, and transformants were selected on selective media (SD-Trp for pIZ1872 and SD-Leu for pIZ1878). Y2HGold/pIZ1872 and Y187/pIZ1878 were mixed on a YPD plate and incubated for 24 h at 30 °C. Mating mixtures were patched on yeast dropout medium (SD) lacking tryptophan and leucine (Clontech) and were incubated at 30 °C for 2 d before replica plating on agar lacking tryptophan, leucine, histidine, and adenine and on agar plates lacking tryptophan and leucine.

SI Materials and Methods

Plasmid Construction.

A complete list of all plasmids used in this study is in Table S3. To express plasmid-borne full-length and processed RprA from the tightly controlled l-arabinose inducible pBAD promoter (75), the following strategy was used: plasmid pBAD-His-myc was PCR amplified [cycling parameters: 95 °C/30 s, 25 times (95 °C/10 s, 59 °C/30 s, 72 °C/2 min), 72 °C/10 min] with primers JVO-0900/0901 (JVO-0901 introduces an XbaI restriction site upstream of the rrnB terminator sequence) and Phusion DNA polymerase (Finnzymes). The PCR product was digested with XbaI and DpnI, and purified. To PCR amplify the rprA inserts, the sense primers (JVO-0907 and JVO-0922) were designed such that they start with the sRNA +1 site (or at the RprA processing site) and that they carry a 5′-phosphate modification. The antisense primer (JVO-0908) binds downstream of the rprA terminator and adds an XbaI site to its sequence. Following amplification with Phusion DNA polymerase, the PCR product was digested with XbaI and gel-purified. Vector- and sRNA-derived PCR products were ligated with T4 DNA ligase (5′ blunt end/3′ XbaI site) and transformed, yielding plasmids pBAD-RprA (pKP-15) and pBAD-RprA proc. (pKP-22). Correct inserts were confirmed by sequencing of the plasmids with vector primers, pBad-FW and pBad-REV. The very same insert was used for construction of plasmid pRprA (pKP-112); here, a XbaI-digested PCR product obtained with primers pLlacoB and pLlacoD on plasmid pZE-12-luc (76) served as vector backbone. Plasmid pKP112 served as template for the construction of RprA mutant plasmids pKP141 using oligonucleotides JVO-3917/3918. The same oligos were used to obtain plasmid pKP198 (template pKP15) and pKP200 (template pKP199). Plasmid pKP199 was constructed by PCR mutagenesis of plasmid pKP15 using oligonucleotides JVO-3996/3997.

Construction of ricI::gfp fusion plasmid (pKP114) was achieved by PCR amplification of to the ricI 5′end (from the transcriptional start site 30 bp of ricI coding region) using primers JVO-3657/3643. This construct served as template for several ricI::gfp mutants plasmids: pKP130 (oligonucleotides JVO-3044/3790), pKP138 (oligonucleotides JVO-3898/3899), pKP150 (oligonucleotides JVO3900/3901), pKP225 (oligonucleotides JVO-6578/6579), and pKP228 (oligonucleotides JVO-6580/6581). Plasmid pKP225 served as template for construction of plasmid pKP227 (oligonucleotides JVO-6580/6581). The PricI::gfp transcriptional reporter (pKP144) was constructed based on plasmid pZEP08 (77) using PCR-amplified ricI promoter fragment (oligonucleotides JVO-3979/3980). This plasmid served as template for pKP247 (oligonucleotides JVO-8687/8688). Plasmids pIZ1872 and pIZ1878 were constructed by amplification of the ricI and traV genes (oligonucleotides STM4242-EcoRI-Fw/STM4242-SalI-Rev and TraV-pGADT7-Fw/TraV-pGADT7-Rev, respectively), and the PCR products were cloned into plasmids pGBKT7 and pGADT7 (Clontech), respectively.

Construction of Salmonella Mutant Strains.

Strains used in this study have been summarized in Table S1. The mouse-virulent strain SL1344 of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium is referred to as the wild-type strain throughout this study. Its derivates were constructed using the lambda red recombinase method (78). The rprA mutant (JVS-0159) strain was previously published (79), as well as strain JVS-5487 [ΔrpoS (72)]. Strain JVS-4065 (ΔrprA::FRT) is a markerless derivate of JVS-0159 using plasmid pCP20 (78). The mutant strains ΔricI (JVS-4477), ΔrcsB (JVS-3891), ΔrcsF (JVS-4123), and ΔrcsC (JVS-4233) were constructed using the same technology with oligonucleotides JVO-3985/3986, JVO-3627/3628, JVO-3857/3858, and JVO-3981/3982, respectively. The C-terminal flagged tagged version of ricI (JVS-3868) was constructed by a modified lambda red approach based on ref. 80 using primer pair JVO-3525/3526. For the chromosomal integration of the ricI* mutant (JVS-9879), the ricI gene was subcloned into plasmid pKP-253, and a single-nucleotide mutation was introduced using primer pair JVO-6580/6581 (resulting in plasmid pKP261) and integrated into a ΔricI strain (generated as described above using lambda red recombination with oligonucleotides JVO-8779/8780). Sequence identity of the ricI* allele was verified by sequencing of the genomic locus. For strain PtetO-ricI::3×FLAG (JVS-4861), the ptetO promoter of pXG-1 (39) was integrated upstream of the ricI::3×FLAG ORF using primer pair JVO-4383/4384. The single-copy transcriptional (JVS-5483) and translational (JVS-5486) ricI::lacZ fusions were constructed as previously described (48). All double and triple mutants derived from P22-transductions of the individual mutants.

5′-RACE experiments.

5′-RACE experiments were carried out as described in detail (81), using RNA extracted from Salmonella grown to an OD600 of 2 and the ricI-specific primer, JVO-3529. Analysis of seven independent cDNA clones suggested the +1 site designated in Fig. 3A.

Coimmunoprecipitation of RicI::3×FLAG.

Cell pellets of 10-mL overnight culture were resuspended in 1 mL of cold lysis buffer (120 mM NaCl, 4 mM MgCl2, 20 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.5, 2 mM EDTA, 1% Nonidet P-40 proteinase inhibitor mixture; Sigma) and lysed by sonication. After centrifugation, the supernatants were recovered and 33 µL of Dynabeads (Novex Life Technologies) and 3 µL of α-flag (Sigma-Aldrich) were added. Samples were incubated on a rotating wheel for 1 h at 4 °C. Immunoprecipitated samples were separated on a polyacrylamide gel and silver-stained (Silver Quest Staining Kit; Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Protein bands were cut and digested with trypsin. Separation and analysis of the tryptic digests were performed using a HPLC-MS/MS system consisting of an Agilent 1100 Series HPLC (Agilent Technologies) equipped with a m-well plate auto sampler and a capillary pump, connected to an Agilent Ion Trap XCT Plus Mass Spectrometer (Agilent Technologies) using an electrospray ionization interface.

Subcellular fractionation of proteins.

Subcellular fractionation was performed as previously described (82), with some modifications. Briefly, bacteria were cultivated in LB medium at 37 °C, centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 5 min at 4 °C and resuspended twice in cold PBS (pH 7.4). The bacterial suspension was either mixed with Laemmli buffer (total protein extract) or disrupted by sonication. Intact cells were removed by low-speed centrifugation (5,000 × g, 5 min, 4 °C). The supernatants were centrifuged at high speed (100,000 × g, 30 min, 4 °C), and the new supernatant was recovered as the cytosol fraction. The pellet containing envelope material was suspended in PBS with 0.4% Triton X-100 and incubated for 2 h at 4 °C. The sample was centrifuged again (100,000 × g, 30 min, 4 °C) and divided into the supernatant containing mostly inner membrane proteins and the insoluble fraction corresponding to the outer membrane fraction. An appropriate volume of Laemmli buffer was added to each fraction. After heating (100 °C, 5 min) and clearing by centrifugation (15,000 × g, 5 min, room temperature), the samples were analyzed for protein content by SDS/PAGE and Western blot.

Acknowledgments

We thank Nassos Typas, Chase Beisel, Cynthia Sharma, Kathrin Fröhlich, and members of the Vogel Laboratory for comments on the manuscript; Barbara Plaschke and Tim Welsink for excellent technical assistance; Philip Silverman for the gift of Alexa 488-labeled R17 bacteriophage; Maria Antonia Sánchez-Romero for help with FACS experiments; and Jay Hinton and Sacha Lucchini for assistance with the transcriptomic analyses. We also thank Modesto Carballo, Laura Navarro, and Cristina Reyes of the Servicio de Biología of the Centro de Investigación, Tecnología e Innovación de la Universidad de Sevilla for help with experiments performed at the facility. This work was funded by support from the Bavarian BioSysNet Program and the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung Project eBio:RNAsys (to J.V.), and Grants BIO2013-44220-R and CSD2008-00013 from the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (MINECO) of Spain and the European Regional Fund, and CVI-5879 from the Consejería de Innovación, Ciencia y Empresa, Junta de Andalucía, Spain (to J.C.). K.P. was supported by a long-term fellowship from the Human Frontiers Science Program, and E.E. was supported by a fellowship from the MINECO program “Formación del Personal Investigador.”

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The microarray data reported in this paper have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo (accession no. GSE67187).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1507825112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Thomas CM, Nielsen KM. Mechanisms of, and barriers to, horizontal gene transfer between bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3(9):711–721. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haft RJ, Mittler JE, Traxler B. Competition favours reduced cost of plasmids to host bacteria. ISME J. 2009;3(7):761–769. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2009.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fàbrega A, Vila J. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium skills to succeed in the host: Virulence and regulation. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2013;26(2):308–341. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00066-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wong JJ, Lu J, Glover JN. Relaxosome function and conjugation regulation in F-like plasmids—a structural biology perspective. Mol Microbiol. 2012;85(4):602–617. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arthur DC, et al. FinO is an RNA chaperone that facilitates sense-antisense RNA interactions. EMBO J. 2003;22(23):6346–6355. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koraimann G, Wagner MA. Social behavior and decision making in bacterial conjugation. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2014;4:54. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2014.00054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Serna A, Espinosa E, Camacho EM, Casadesús J. Regulation of bacterial conjugation in microaerobiosis by host-encoded functions ArcAB and sdhABCD. Genetics. 2010;184(4):947–958. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.109918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Camacho EM, Casadesús J. Conjugal transfer of the virulence plasmid of Salmonella enterica is regulated by the leucine-responsive regulatory protein and DNA adenine methylation. Mol Microbiol. 2002;44(6):1589–1598. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.García-Quintanilla M, Ramos-Morales F, Casadesús J. Conjugal transfer of the Salmonella enterica virulence plasmid in the mouse intestine. J Bacteriol. 2008;190(6):1922–1927. doi: 10.1128/JB.01626-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.García-Quintanilla M, Prieto AI, Barnes L, Ramos-Morales F, Casadesús J. Bile-induced curing of the virulence plasmid in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 2006;188(22):7963–7965. doi: 10.1128/JB.00995-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gottesman S, Storz G. Bacterial small RNA regulators: Versatile roles and rapidly evolving variations. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;3(12) doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003798. pii: a003798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Papenfort K, Vanderpool CK. Target activation by regulatory RNAs in bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2015;39(3):362–378. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fuv016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Lay N, Schu DJ, Gottesman S. Bacterial small RNA-based negative regulation: Hfq and its accomplices. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(12):7996–8003. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R112.441386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vogel J, Luisi BF. Hfq and its constellation of RNA. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011;9(8):578–589. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Will WR, Frost LS. Hfq is a regulator of F-plasmid TraJ and TraM synthesis in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2006;188(1):124–131. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.1.124-131.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Battesti A, Majdalani N, Gottesman S. The RpoS-mediated general stress response in Escherichia coli. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2011;65:189–213. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-090110-102946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mika F, Hengge R. Small RNAs in the control of RpoS, CsgD, and biofilm architecture of Escherichia coli. RNA Biol. 2014;11(5):494–507. doi: 10.4161/rna.28867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Papenfort K, et al. Specific and pleiotropic patterns of mRNA regulation by ArcZ, a conserved, Hfq-dependent small RNA. Mol Microbiol. 2009;74(1):139–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Soper T, Mandin P, Majdalani N, Gottesman S, Woodson SA. Positive regulation by small RNAs and the role of Hfq. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(21):9602–9607. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004435107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Majdalani N, Chen S, Murrow J, St John K, Gottesman S. Regulation of RpoS by a novel small RNA: The characterization of RprA. Mol Microbiol. 2001;39(5):1382–1394. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2001.02329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Majdalani N, Hernandez D, Gottesman S. Regulation and mode of action of the second small RNA activator of RpoS translation, RprA. Mol Microbiol. 2002;46(3):813–826. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vogt SL, Evans AD, Guest RL, Raivio TL. The Cpx envelope stress response regulates and is regulated by small noncoding RNAs. J Bacteriol. 2014;196(24):4229–4238. doi: 10.1128/JB.02138-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Majdalani N, Gottesman S. The Rcs phosphorelay: A complex signal transduction system. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2005;59:379–405. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.59.050405.101230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vogt SL, Raivio TL. Just scratching the surface: An expanding view of the Cpx envelope stress response. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2012;326(1):2–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2011.02406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Madhugiri R, Basineni SR, Klug G. Turn-over of the small non-coding RNA RprA in E. coli is influenced by osmolarity. Mol Genet Genomics. 2010;284(4):307–318. doi: 10.1007/s00438-010-0568-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Updegrove T, Wilf N, Sun X, Wartell RM. Effect of Hfq on RprA-rpoS mRNA pairing: Hfq-RNA binding and the influence of the 5′ rpoS mRNA leader region. Biochemistry. 2008;47(43):11184–11195. doi: 10.1021/bi800479p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones AM, Goodwill A, Elliott T. Limited role for the DsrA and RprA regulatory RNAs in rpoS regulation in Salmonella enterica. J Bacteriol. 2006;188(14):5077–5088. doi: 10.1128/JB.00206-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kröger C, et al. The transcriptional landscape and small RNAs of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(20):E1277–E1286. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1201061109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Soper TJ, Woodson SA. The rpoS mRNA leader recruits Hfq to facilitate annealing with DsrA sRNA. RNA. 2008;14(9):1907–1917. doi: 10.1261/rna.1110608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Argaman L, et al. Novel small RNA-encoding genes in the intergenic regions of Escherichia coli. Curr Biol. 2001;11(12):941–950. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00270-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chao Y, Papenfort K, Reinhardt R, Sharma CM, Vogel J. An atlas of Hfq-bound transcripts reveals 3′ UTRs as a genomic reservoir of regulatory small RNAs. EMBO J. 2012;31(20):4005–4019. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sittka A, et al. Deep sequencing analysis of small noncoding RNA and mRNA targets of the global post-transcriptional regulator, Hfq. PLoS Genet. 2008;4(8):e1000163. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Papenfort K, et al. SigmaE-dependent small RNAs of Salmonella respond to membrane stress by accelerating global omp mRNA decay. Mol Microbiol. 2006;62(6):1674–1688. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05524.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McCullen CA, Benhammou JN, Majdalani N, Gottesman S. Mechanism of positive regulation by DsrA and RprA small noncoding RNAs: Pairing increases translation and protects rpoS mRNA from degradation. J Bacteriol. 2010;192(21):5559–5571. doi: 10.1128/JB.00464-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]