Significance

Most proteins are long polymers of amino acids with 20 or more chemically distinct side-chains, whereas transmembrane domains are short membrane-spanning protein segments with mainly hydrophobic amino acids. Here, we have defined the minimal chemical diversity sufficient for a protein to display specific biological activity by isolating artificial 26-aa-long transmembrane proteins consisting of random sequences of only two hydrophobic amino acids, leucine and isoleucine. A small fraction of proteins with this composition interact with the transmembrane domain of a growth factor receptor to specifically activate the receptor, resulting in growth transformation. These findings change our view of what can constitute an active protein and have important implications for protein evolution, protein engineering, and synthetic biology.

Keywords: synthetic biology, oncogene, traptamer, E5 protein, PDGF receptor

Abstract

We have constructed 26-amino acid transmembrane proteins that specifically transform cells but consist of only two different amino acids. Most proteins are long polymers of amino acids with 20 or more chemically distinct side-chains. The artificial transmembrane proteins reported here are the simplest known proteins with specific biological activity, consisting solely of an initiating methionine followed by specific sequences of leucines and isoleucines, two hydrophobic amino acids that differ only by the position of a methyl group. We designate these proteins containing leucine (L) and isoleucine (I) as LIL proteins. These proteins functionally interact with the transmembrane domain of the platelet-derived growth factor β-receptor and specifically activate the receptor to transform cells. Complete mutagenesis of these proteins identified individual amino acids required for activity, and a protein consisting solely of leucines, except for a single isoleucine at a particular position, transformed cells. These surprisingly simple proteins define the minimal chemical diversity sufficient to construct proteins with specific biological activity and change our view of what can constitute an active protein in a cellular context.

The chemical diversity of the 20 standard amino acid side-chains found in proteins supports myriad biochemical activities essential for life, and additional chemical diversity is generated by posttranslational amino acid modifications. The number of potential protein sequences is enormous: for proteins only 300 amino acids long, ∼10400 possible sequences exist, a number larger by many orders-of-magnitude than the number of atoms in the known universe. This immense number of sequences and the chemical and conformational complexity of naturally occurring proteins hinder our ability to understand protein structure, folding, and function, and complicate protein engineering efforts. In addition, many different related amino acid sequences can fold into nearly identical structures, and even proteins with quite divergent sequences or protein folds can use similar chemistry to carry out related functions or display the same catalytic activity (e.g., refs. 1–3). These considerations further complicate attempts to clearly identify and understand the key structural features of proteins. Thus, the isolation of biologically active proteins with drastically reduced chemical complexity would represent a significant advance in protein science by facilitating the correlation of specific structural features with function.

Up to 30% of all proteins contain ∼20–25-amino acid, primarily hydrophobic segments that span cell membranes (4). These transmembrane domains often play critical roles in cellular processes by engaging in highly specific protein–protein and protein–lipid interactions required for the proper folding, oligomerization, and function of transmembrane proteins (5–8). For example, receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) such as the PDGF-β receptor (PDGFβR) usually consist of an extracellular ligand binding domain, a single transmembrane domain, and a cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase domain. RTKs typically exist as catalytically inactive monomers, and ligand binding induces RTK dimerization, kinase activation, autophosphorylation of the receptor on cytoplasmic tyrosine residues, and mitogenic signaling. Mutations in the transmembrane domains of some RTKs, such as ErbB2, can cause constitutive activation of the receptor (9).

Some naturally occurring proteins consist of only one or a few helical transmembrane domains with little additional folded structure, and computational methods have been used to design artificial transmembrane peptides with biochemical or biological activity (10–13). The dimeric 44-amino acid bovine papillomavirus (BPV) E5 protein is the smallest known naturally occurring oncoprotein (14–16). This very hydrophobic protein, essentially a free-standing transmembrane domain with short extramembraneous segments, binds specifically to the transmembrane domain of the PDGFβR, resulting in constitutive activation of this receptor (14, 16–21). Sustained mitogenic signaling by the activated PDGFβR confers the transformed phenotype on cells, including loss of contact inhibition, morphologic transformation, focus formation, growth factor independence, and tumorigenicity in animals. Coimmunoprecipitation studies in detergent extracts of transformed cells demonstrated that the E5 protein and PDGFβR exist in a stable complex, and extensive mutational analysis, isolation of compensatory mutants between the E5 protein and the PDGFβR, and molecular modeling suggest that the E5 protein interacts directly with the transmembrane domain of the PDGFβR. This transmembrane interaction appears to be mediated by interactions between specific hydrophilic residues in the two proteins as well as by packing interactions.

We have developed genetic methods to select short biologically active transmembrane proteins modeled on the E5 protein from libraries expressing many thousands of artificial proteins with randomized hydrophobic segments (named transmembrane protein aptamers or “traptamers”) (22–25). Because of the relative simplicity of transmembrane domains, we reasoned that this approach could be used to define the minimal chemical complexity sufficient to construct biologically active proteins. Here, we isolate short transmembrane oncoproteins that are the simplest proteins ever described with specific biological activity. These proteins change our understanding of the chemical diversity required for protein function.

Results

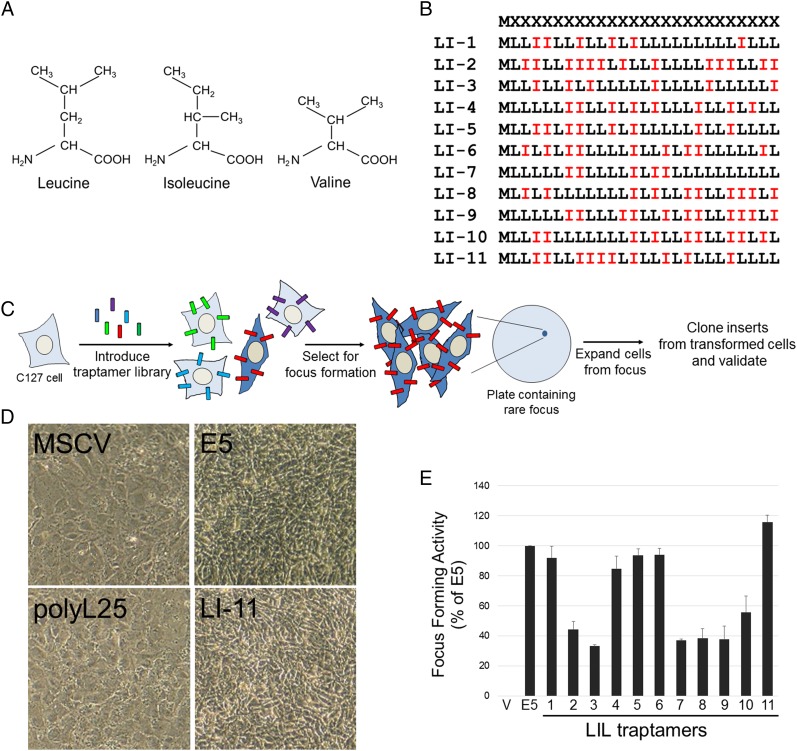

To isolate ultrasimple oncoproteins, we constructed a retroviral library (designated UDv6) expressing traptamers in which a methionine initiation codon was followed by 25 codons encoding equimolar leucine and isoleucine in random order (Fig. 1 A and B). The theoretical complexity of this library is 225 = ∼33.5 million. For the experiments reported here, we pooled ∼5.5 million bacterial colonies to generate the library, setting an upper limit on the number of independent sequences in the library. Normal C127 mouse fibroblasts were infected at low multiplicity with ∼160,000 clones from the library, and rare foci of transformed cells were isolated and expanded into cell lines (Fig. 1C). Individual traptamer genes recovered from the DNA of these cells were tested for transforming activity. Eleven recovered traptamers, each with a different sequence (Fig. 1B), induced morphologic transformation in C127 cells and in human primary foreskin fibroblasts (HFFs) (Fig. 1D and Fig. S1). Several of these traptamers strongly induced focus formation in C127 cells (approximately 40 transformed foci per 1,000 infectious units, similar to the BPV E5 protein) (Fig. 1E), although we cannot normalize the transforming activities of the various traptamers to their expression because the abundance of these untagged proteins cannot be measured. In contrast, a clone consisting of methionine followed by 25 leucines (designated polyL25) did not induce transformation (Fig. 1D), nor did traptamers randomly chosen from the library without biological selection (Fig. S2). Codon-optimized versions of traptamers LI-7 and LI-11, which contained numerous nucleotide changes that did not affect the amino acid sequence, transformed cells, whereas introduction of a single translation stop codon abolished activity (Fig. S3). Thus, the encoded proteins and not the RNA structures are responsible for transformation.

Fig. 1.

Proteins composed of only leucine and isoleucine transform cells. (A) Isoleucine and leucine side-chains differ in the position of a methyl group. Valine is identical to isoleucine except for the absence of a terminal methyl group. (B) Sequences of the UDv6 library and the active traptamers. The first line shows the design of the library, where M represents methionine and X represents positions randomized to be equimolar leucine (L) and isoleucine (I). The other lines show the sequences of the 11 active traptamers. (C) Scheme to isolate traptamers with transforming activity. C127 mouse fibroblasts were infected with a retrovirus library expressing traptamers (the different colored cylinders represent different traptamer sequences) and incubated at confluence for 3 wk. The red traptamer induces transformation (indicated by the dark blue cells) and focus formation. Genes encoding the traptamers were cloned from genomic DNA isolated from cells expanded from individual transformed foci. Traptamer activity was validated by reintroduction into naïve C127 cells. (D) C127 cells were infected with high-titer stocks of empty vector (MSCV), or MSCV expressing BPV E5, polyL25, or traptamer LI-11. Photomicrographs were taken at 100× magnification 10 d later. Transformed cells are refractile and irregularly pile on each other after loss of contact inhibition. (E) C127 cells were infected with low-titer stocks of the viruses expressing traptamers listed in B, and foci of transformed cells were counted 3 wk later. Focus-forming activity (number of foci formed normalized to viral titer) of traptamers is shown relative to E5 activity (set at 100%). V, cells infected with empty MSCV vector. The results show the average of three independent experiments with SE.

Fig. S1.

Traptamers transform primary HFFs. HFFs were mock infected or infected with high-titer stocks of MSCV expressing BPV E5 or the indicated traptamer. Cells were photographed at 100× magnification 7 d later.

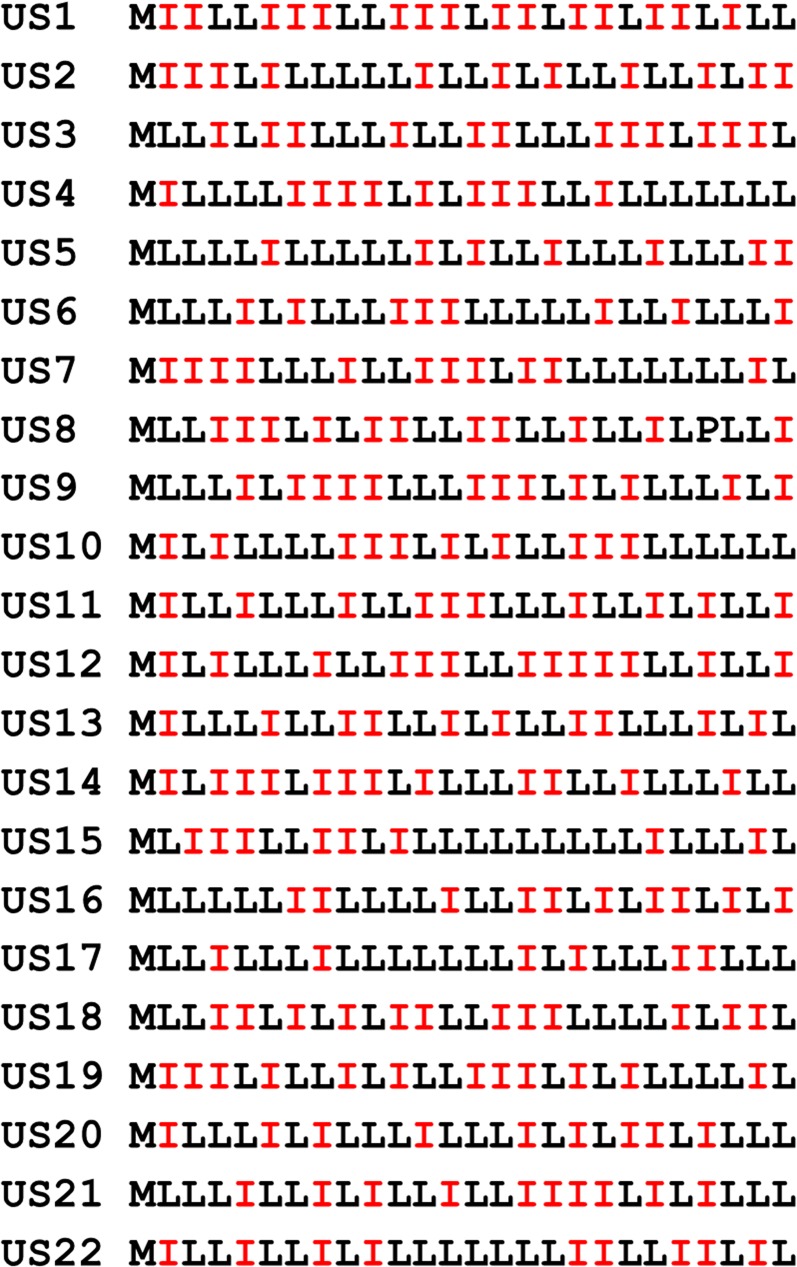

Fig. S2.

Sequences of 22 inactive unselected traptamers. Sequences displayed as in Fig. 1B. None of these proteins transform cells.

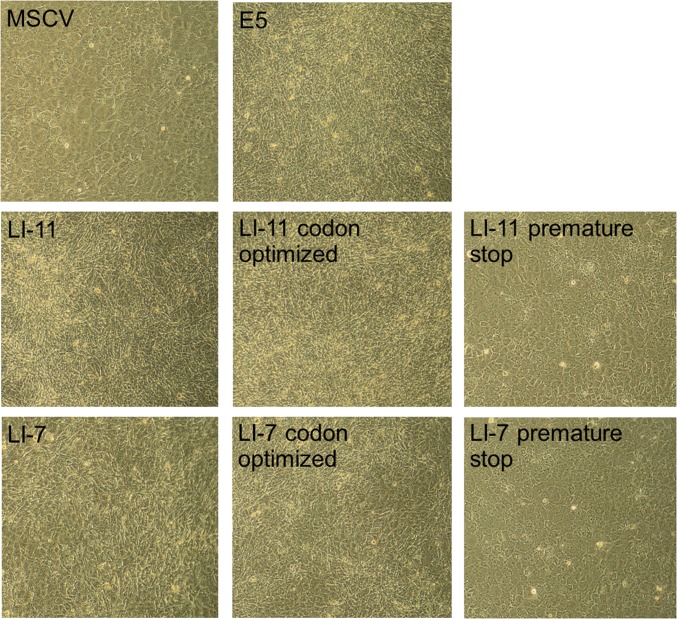

Fig. S3.

Traptamer activity is due to the expressed protein. C127 cells were infected with high-titer stocks of MSCV vector or MSCV expressing BPV E5, traptamer LI-11 or LI-7, a codon optimized version of LI-11 or LI-7, or LI-11 or LI-7 with a premature stop codon at position 13. Cells were photographed at 100× magnification 10 d later.

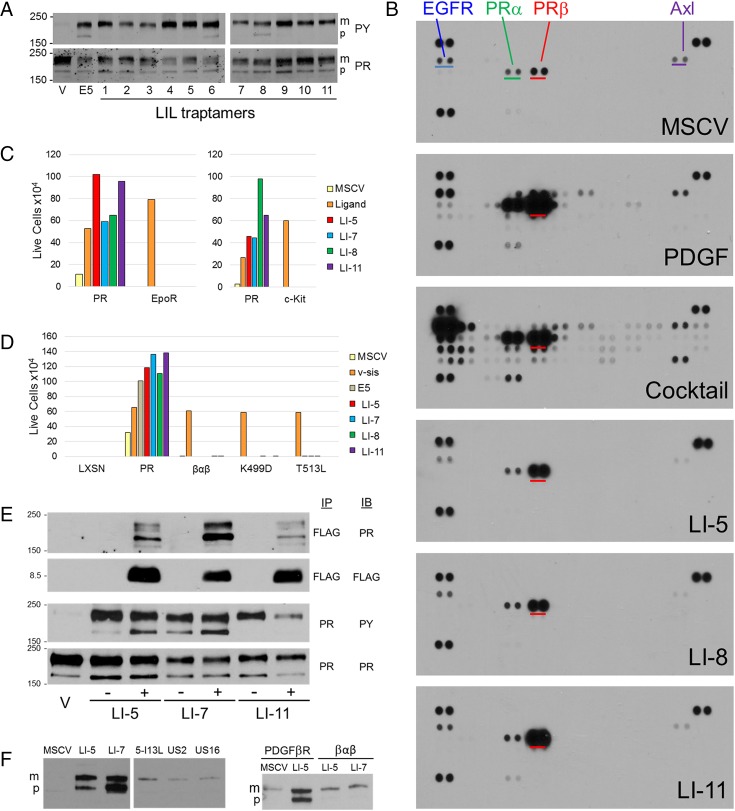

We hypothesized that the active traptamers induced transformation by interacting with a cellular target protein and activating a mitogenic signaling cascade. To determine if these traptamers, like the E5 protein, activate the PDGFβR, lysates of transformed C127 cells were immunoprecipitated with anti-PDGFβR and immunoblotted with anti-phosphotyrosine antibody. As shown in Fig. 2A, Upper, basal tyrosine phosphorylation of the PDGFβR in untransformed cells was very low. In contrast, substantial tyrosine phosphorylation of the PDGFβR was detected in cells expressing the E5 protein or any of the active traptamers, indicating that the traptamers activate the PDGFβR. Like the E5 protein, some of the traptamers activated not only the mature form of the receptor, but also a rapidly migrating precursor form of the PDGFβR containing immature carbohydrates. This might result from the localization of different traptamers (and hence the activated PDGFβR) in different intracellular compartments.

Fig. 2.

Traptamers specifically bind and activate the PDGFβR. (A) Extracts prepared from C127 cells expressing MSCV vector (V), the E5 protein, or the indicated traptamer were immunoprecipitated with anti-PDGF receptor (PR) antibody and blotted for phosphotyrosine (PY, Upper) or PDGFβR (Lower). m, mature PDGFβR; p, precursor form of the receptor with immature carbohydrates activated by the E5 protein and some of the traptamers. (B) Extracts were prepared from human diploid fibroblasts that were untreated (MSCV), acutely treated with PDGF-DD (PDGF) or with a mixture of growth factors, or stably transformed by traptamer LI-5, LI-8, and LI-11. phospho-RTK arrays were incubated with cell extracts, processed, and exposed to film for the same length of time. The spots representing PDGFβR are underlined in red on all arrays. EGF receptor, PDGFαR, and Axl are underlined in blue, green, and purple, respectively, on the array probed with the extract of control cells. The dark pairs of spots at the corners are standards. (C) BaF3 cells expressing the PDGFβR (PR), the erythropoietin receptor (EpoR) (Left), or the c-kit (Right) were infected with MSCV or MSCV expressing the indicated traptamer or v-sis (for PR cells) or treated with EPO (for EpoR cells) or stem cell factor (SCF, for c-kit cells). The number of live cells was counted 5 d after IL-3 removal. Each experiment was performed three times. Although the inherent variability of this assay precluded a rigorous statistical analysis, the same trends were observed in each experiment. The graphs show the results of a representative experiment. (D) BaF3 cells expressing the LXSN empty vector, the PDGFβR, a chimeric PDGFβR containing the transmembrane domain of the PDGFαR (βαβ), or a mutant PDGFβR were infected with MSCV or MSCV expressing v-sis, the E5 protein, or the indicated traptamer. The number of live cells was counted 5 d after IL-3 removal. The experiment was performed three times and the same trends were observed in each experiment. The graph shows the results of a representative experiment. (E) Detergent extracts were prepared from untransformed C127 cells harboring MSCV (V) or cells transformed by the indicated FLAG-tagged (+) or untagged (−) traptamer. Extracts were immunoprecipitated (IP) and immunoblotted (IB) with the indicated antibody. (F, Left) Detergent extracts were prepared from BaF3 cells expressing the PDGFβR and MSCV or the indicated FLAG-tagged traptamer. US2 and US16 are inactive unselected clones. Extracts were imunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG and immunoblotted with anti-PDGF receptor. Both panels were from the same exposure from the same gel; an irrelevant lane was removed. (Right) Detergent extracts were prepared from BaF3 cells expressing the PDGFβR or the βαβ chimeric receptor together with MSCV or FLAG-tagged LI-5 or LI-7. Extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG and immunoblotted with anti-PDGF receptor.

To examine the specificity of the traptamers, we used phospho-RTK arrays to assess activation of numerous RTKs. Extracts were prepared from serum-starved HFFs, from HFFs acutely treated with PDGF-DD [which nominally activates only the PDGFβR (26)] or a mixture of growth factors, or from HFFs stably transformed by traptamer LI-5, LI-8, or LI-11. These extracts were incubated with nitrocellulose membranes containing duplicate spots of antibodies that captured 49 individual RTKs, after which the membranes were probed with an antiphosphotyrosine antibody. The intensity of a spot corresponds to the extent of tyrosine phosphorylation of the target RTK. As shown in Fig. 2B, the PDGFβR, PDGF-α receptor (PDGFαR), EGF receptor, and Axl displayed a low basal level of constitutive tyrosine phosphorylation in control cells. PDGF-DD caused a dramatic increase in tyrosine phosphorylation of the PDGFβR and lesser increases in several other RTKs, whereas treatment with the growth factor mixture resulted in tyrosine phosphorylation of many RTKs. Strikingly, for all three tested traptamers, the only significant difference compared with control cells was markedly increased tyrosine phosphorylation of the PDGFβR (Fig. 2B), demonstrating that the traptamers are highly specific in their ability to activate the PDGFβR. Indeed, in this assay the traptamers were more specific for the PDGFβR than was PDGF itself. Minor differences in the intensity of some faint spots in response to a given traptamer were not reproducible.

We used murine BaF3 cells to determine if traptamer activity required the PDGFβR. BaF3 cells lack endogenous PDGFβR and require IL-3 for growth, but become IL-3–independent if an exogenous growth factor receptor is expressed and activated (Fig. 2C) (27, 28). Cells expressing the PDGFβR alone or the traptamer alone grew poorly in the absence of IL-3. However, when PDGFβR was coexpressed with v-sis, the viral homolog of PDGF, or any of the four tested traptamers, the cells proliferated in the absence of IL-3 (Fig. 2C), demonstrating that the traptamers require PDGFβR for activity. We also tested the traptamers in BaF3 cells expressing a different RTK, c-kit, or a cytokine receptor, the erythropoietin receptor (EPOR). Both of these receptors conferred IL-3 independence when stimulated with their cognate ligands but did not confer IL-3 independence in response to the traptamers (Fig. 2C). Thus, the ability of the traptamers to confer growth factor independence was specific for the PDGFβR. We also used this system to map the domain of the PDGFβR required for productive interaction. We first analyzed BaF3 cells expressing a chimeric receptor in which the transmembrane domain of the PDGFβR was replaced with the transmembrane domain of the PDGFαR (termed βαβ) (Fig. 2D) (29, 30). Cells expressing βαβ grew when they coexpressed v-sis, which binds the extracellular domain of the PDGFβR. In contrast, neither E5 nor the traptamers conferred IL-3 independence in cells expressing βαβ. Similarly, v-sis but not the traptamers cooperated with a PDGFβR mutant containing a Lys499 to aspartic acid or a Thr513 to leucine substitution in the transmembrane region. These data demonstrate that these four traptamers require the PDGFβR transmembrane domain for activity and that activity is inhibited by single amino acid substitutions in this segment of the receptor.

Next we wished to investigate whether the traptamers interacted with the PDGFβR, but the very hydrophobic nature of the traptamers complicates biophysical analysis, which traditionally has been used to study the interaction of natural and artificial transmembrane domains with far greater chemical diversity (10, 31, 32). Therefore, we used coimmunoprecipitation to determine if the traptamers were present in a stable complex with the PDGFβR in transformed cells. We first added a FLAG epitope tag to the N terminus of traptamers LI-5, LI-7, and LI-11. Addition of the FLAG-tag caused no more than a ∼50% increase or decrease in focus-forming activity of these traptamers (Fig. S4), and all tagged traptamers induced tyrosine phosphorylation of the PDGFβR (Fig. 2E, third row). Detergent extracts of transformed C127 cells were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibody and subjected to immunoblotting. The anti-FLAG antibody detected a ∼8.5-kDa band in cells transduced with a FLAG-tagged traptamer gene (Fig. 2E, second row), confirming that the tagged traptamers were expressed.

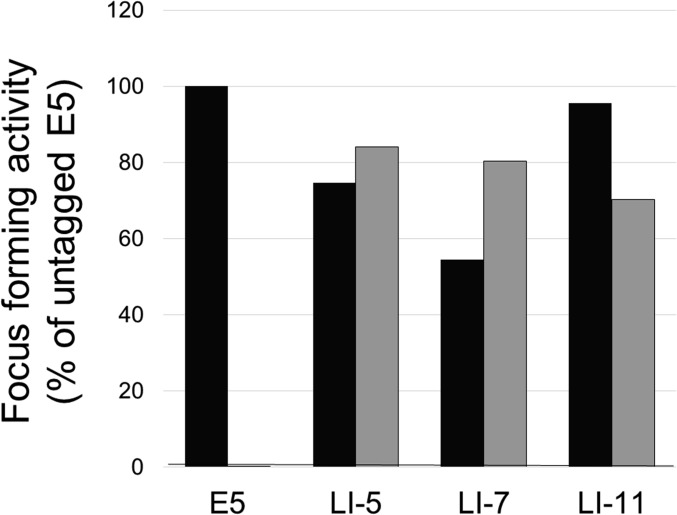

Fig. S4.

Effect of the FLAG tag on traptamer activity. C127 cells were infected with low-titer stocks of MSCV or MSCV expressing untagged (black bars) or FLAG-tagged (gray bars) versions of the BPV E5 protein or the indicated traptamer. Foci were counted after 3 wk, and activity was normalized for virus titer and expressed relative to untagged BPV E5. The graph shows results of a representative experiment. Similar results were obtained in multiple independent experiments.

Immunoblotting with anti-PDGFβR showed that anti-FLAG coimmunoprecipitated the mature and precursor PDGFβR from cells expressing the FLAG-tagged traptamers, but not from cells expressing their untagged counterparts, indicating that the traptamers were present in a stable complex with the PDGFβR (Fig. 2E, Top). We further showed that the defective LI-5 isoleucine 13 to leucine mutant (see next paragraph) as well as two unselected traptamers associated poorly with the PDGFβR in a coimmunoprecipitation experiment in comparison with the active traptamers, LI-5 and LI-7 (Fig. 2F). Furthermore, LI-5 and LI-7, which showed the most robust coimmunoprecipitation with wild-type PDGFβR, failed to coimmunoprecipitate with the βαβ receptor chimera, which contains an ectopic transmembrane domain and fails to cooperate with these traptamers in the BaF3 cell growth factor independence assay (Fig. 2F). This experiment shows that stable complex formation between the active traptamers and the PDGFβR correlates with transforming activity and requires the transmembrane domain of the receptor.

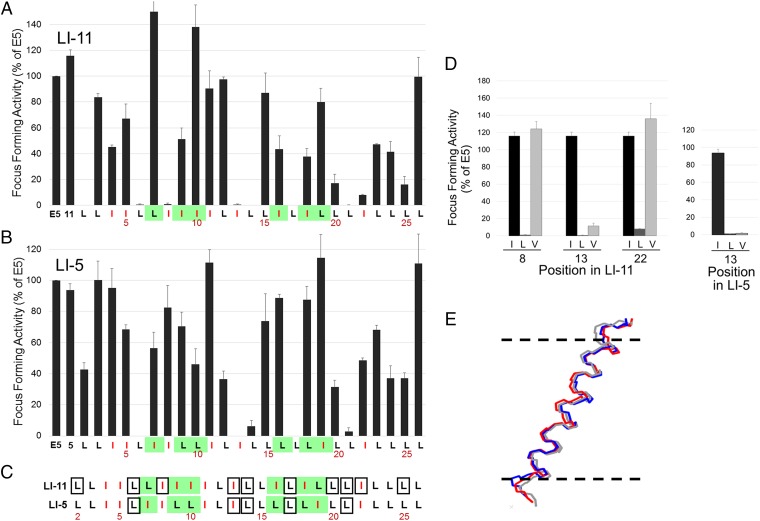

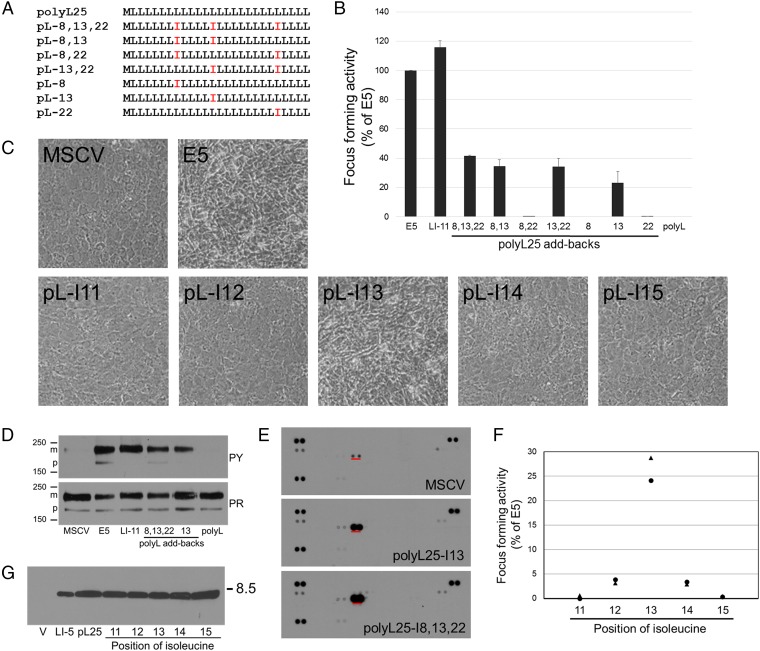

To determine if specific amino acids in the traptamers were required for activity, we conducted complete mutagenesis of LI-5 and LI-11, in which each leucine was changed individually to isoleucine and vice versa. Mutations at several positions dramatically inhibited focus formation (Fig. S5). LI-11 required isoleucines at positions 8, 13, and 22 and leucines at positions 2, 6, 14, 17, 20, 21, and 25 for high focus-forming activity (Fig. 3A). Leucine or isoleucine, as appropriate, was enriched at these positions in the active traptamers compared with the unselected traptamers (Fig. S6). LI-5 required a subset of these residues, L6, I13, L14, L17, and L21 (Fig. 3B). Thus, the requirements for LI-5 and LI-11 were similar but not identical. These mutagenesis results are summarized in Fig. 3C. Interestingly, none of the amino acids that differ between the two traptamers (shown in green in Fig. 3C) are required for activity. We then mutated the required isoleucines in LI-5 and LI-11 to valine, another hydrophobic amino acid (Fig. 1A). Substitution of a valine at position 13 abolished or severely inhibited the activity of both traptamers, but valine was tolerated at position 8 or 22 in LI-11 (Fig. 3D). These data suggest that isoleucine 13 is particularly important for traptamer activity and that the required isoleucines at positions 8 and 22 in LI-11 play a qualitatively different role than isoleucine 13 in transforming activity.

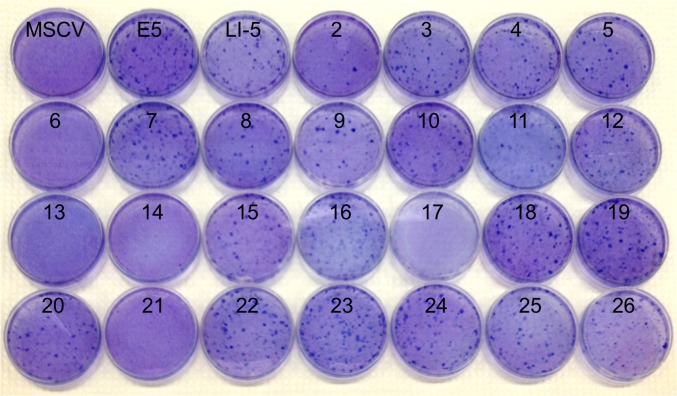

Fig. S5.

Complete mutagenesis of traptamer LI-5. C127 cells were infected with low-titer retrovirus stocks of MSCV vector or MSCV expressing BPV E5, wild-type LI-5, and a series of LI-5 mutants in which the wild-type amino acid at each position was changed to either leucine or isoleucine, as appropriate. Plates were stained with Giemsa 3 wk later. These plates were assembled from several different assays and not normalized for virus titer, but are representative of normalized activity.

Fig. 3.

Comprehensive mutational analysis of traptamers. (A) C127 cells were infected with low-titer retrovirus expressing the E5 protein, wild-type LI-11, or an LI-11 mutant in which a leucine was changed to isoleucine or an isoleucine was changed to leucine. Sequence of wild-type LI-11 starting at position 2 is shown at the bottom, with isoleucines shown in red and positions that differ between LI-5 and LI-11 highlighted in green. The bars above the sequence show the activity of the mutant with the substitution at that position. Transformed foci were counted after infected cells were incubated at confluence for 3 wk. Focus-forming activity displayed as in Fig. 1E. (B) Focus-forming activity of LI-5 mutants tested and displayed as in A. (C) Sequences of LI-5 and LI-11 are displayed as described in A. Residues that when mutated to leucine or isoleucine result in 80% or greater reduction in focus-forming activity are shown in boxes. (D) Focus-forming activity was measured and displayed as described in A for traptamers containing isoleucine (black), leucine (dark gray), or valine (light gray) at the indicated position in traptamer LI-11 (Left) or at position 13 in LI-5 (Right). (E) Molecular dynamics simulation indicates that the helical backbones of LI-11, LI-11-I13L, and LI-11-I13V are very similar. The diagram shows an overlay of lateral views of the backbones of three aligned helices. The horizontal dashed lines represent the approximate extent of the membrane bilayer hydrophobic region; the amino termini of the proteins are at the top.

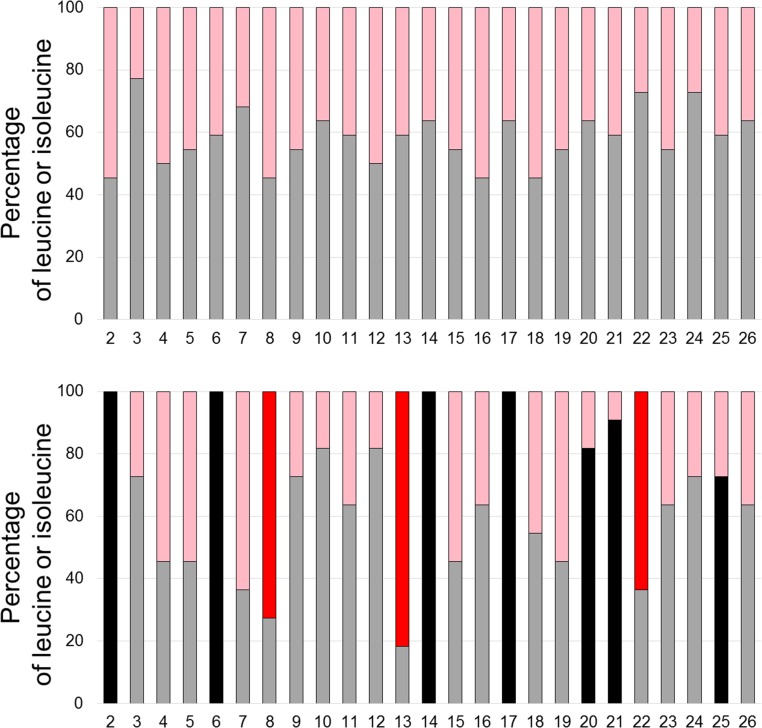

Fig. S6.

Enrichment of amino acids at specific positions in active traptamers. The graphs show the percentage of leucines (pink and red) and isoleucines (gray and black) at each position in 22 unselected inactive traptamers (Upper) and 11 active traptamers (Lower). Leucines required for LI-11 activity are shown by black bars in the lower panel, and required isoleucines are shown by red bars.

To ask if the inactivating mutations are likely to cause global disruption of traptamer structure, we used all-atom molecular dynamics simulations in explicit POPC (1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine) lipid bilayers in excess water to generate models of wild-type LI-11 and its defective mutants, 11-I13L and 11-I13V (see SI Materials and Methods for the modeling and references). After initial equilibration, the simulations were run for 150 ns. The models of all three traptamers converged on stable, extended α-helical backbone structures roughly perpendicular to the lipid bilayer (tilt ∼10° to 25°), with position 13 in the middle of the bilayer (Fig. 3E). Notably, the backbone models of wild-type LI-11 and its two mutants were very similar (the average peptide backbone RMSD of wild-type LI-11 compared with either mutant was <1.7 Å). As expected for an α-helix, the radially displayed amino acid side-chains did not interact with each other or with the hydrophilic groups in the protein backbone and the arrangement of side-chain carbon atoms at position 13 in wild-type LI-11 was markedly different from their arrangement in the mutants (Fig. S7). These results imply that the inactivating amino acid substitutions at position 13 do not cause global alterations in the structure of the protein, but rather cause a local structural perturbation at the site of the mutation.

Fig. S7.

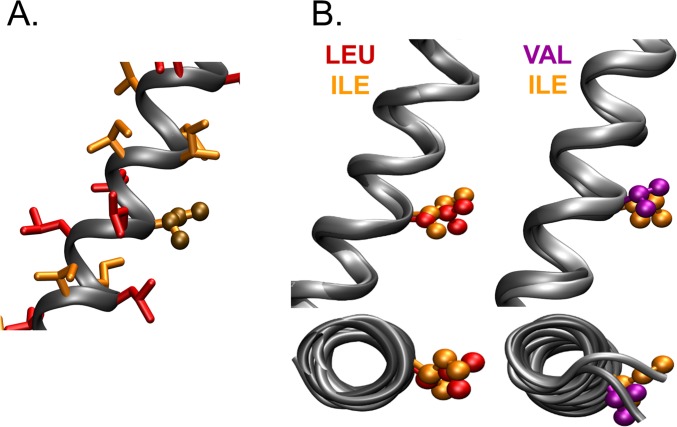

Molecular dynamics simulations reveal the disposition of amino acid side-chains in LI-11 and its mutants. (A) A lateral view of the LI-11 model illustrates the radial distribution of amino acid side-chains. Leucine side-chains, orange; isoleucine side-chains, yellow. Side-chains at position 13 are shown in ball-and-stick representation. None of the carbon atoms in different side-chains approach within 2 Å of each other. (B) The figure shows lateral (Upper) and axial (Lower) views of aligned LI-11 and its mutants containing leucine (Left) or valine (Right) at position 13, showing the average structures of the side-chains at position 13 in ball-and-stick representation. Leucine, yellow; isoleucine, orange; valine, purple.

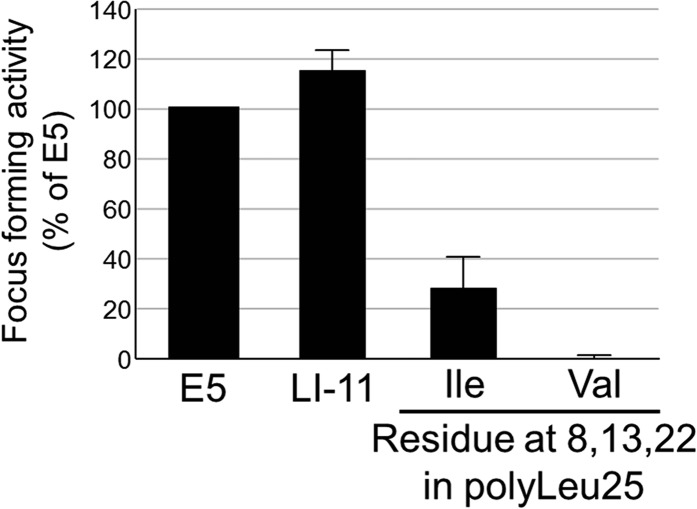

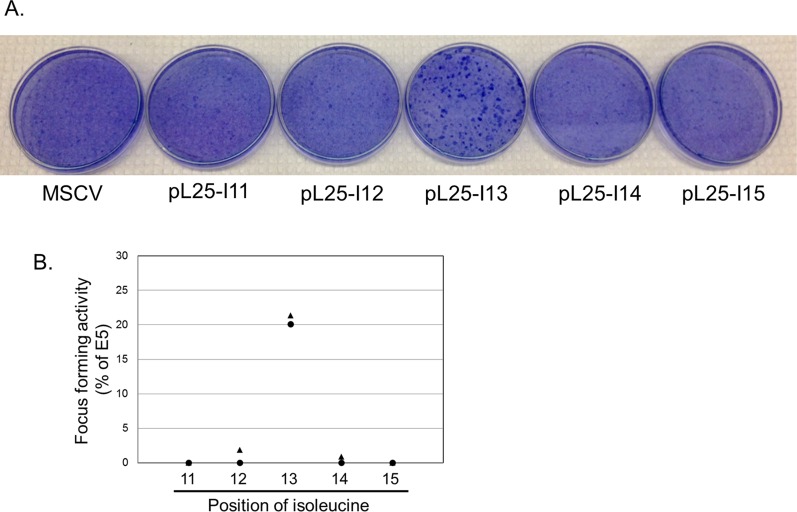

Previous work in other laboratories showed that insertion of defined dimerization motifs was sufficient to drive homodimerization of transmembrane peptides (33–35). Because our results suggested that the mutations interfere with the transforming activity of the traptamers by acting locally on the structure of the traptamer, we tested whether introduction of isoleucines at crucial positions in a simple sequence was sufficient for biological activity. We inserted isoleucines into polyL25 at positions 8, 13, and 22 singly and in combination and tested the ability of these mutants to transform cells (Fig. 4A). All polyL25 mutants containing isoleucine at position 13 displayed focus-forming activity, whereas mutants lacking Ile13 were inactive, as was polyL25 containing valines at positions 8, 13, and 22 (Fig. 4B and Fig. S8). Most strikingly, polyL25 containing a single isoleucine at position 13 (polyL25-I13) induced focus formation and morphologic transformation (Fig. 4 B and C and Fig. S9). Moreover, polyL25-I8,13,22, and polyL25-I13 induced specific tyrosine phosphorylation of the PDGFβR in transformed HFFs (Fig. 4 D and E). We also constructed polyL25 mutants containing a single isoleucine at positions 11 through 15 and scored their ability to induce morphologic transformation and focus formation in C127 cells. Although isoleucine at position 13 conferred activity, mutants with an isoleucine at other positions were defective in these assays, demonstrating that the position of the isoleucine was important for transforming activity. (Fig. 4B and Fig. S9). We also constructed FLAG-tagged versions of these traptamers and tested their activity in C127 cells. As expected, the isoleucine at position 13 conferred relatively high focus-forming activity (Fig. 4F). In addition, an isoleucine at flanking position 12 or 14 conferred ∼10-fold lower activity, whereas traptamers with isoleucine at position 11 or 15 were inactive (Fig. 4F), even though all traptamers were expressed at similar levels (Fig. 4G). Thus, insertion of a single isoleucine at a particular position in a stretch of leucines is sufficient to specifically activate the PDGFβR and transform cells, and isoleucine at an immediately adjacent position conferred weak transforming activity.

Fig. 4.

Insertion of isoleucine into polyL25 restores activity. (A) Sequences of add-back mutants in which isoleucines were inserted at the indicated positions in polyL25. (B) Traptamers listed in A were tested for focus forming activity as in Fig. 1E. The results show the average of three independent experiments with SE indicated. (C) C127 cells were infected with high-titer stocks of empty MSCV vector or MSCV expressing the E5 protein or a polyL25 mutant containing a single isoleucine at the indicated position. Photomicrographs were taken at 100× magnification 10 d later. The titer of all virus stocks was similar. (D) Extracts were prepared from C127 cells harboring empty MSCV or MSCV expressing the E5 protein, LI-11, polyL25-I8,13,22, polyL25-I13, or polyL25 (polyL). Extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-PDGFβR antibody, subjected to SDS/PAGE, and immunoblotted with antibody recognizing phosphotyrosine (Upper) or PDGFβR (Lower). (E) Extracts were prepared from serum-starved human diploid fibroblasts (MSCV) or cells stably transformed by polyL25-I18,13,22, or polyL25-I13. phospho-RTK arrays were processed as described in Fig. 2B. The tyrosine phosphorylated PDGFβR spots are underlined in red. (F) C127 cells were infected with low-titer retrovirus stocks of MSCV expressing BPV E5 or a FLAG-tagged polyL25 add-back clone containing isoleucine at the indicated position. Foci were counted 2 to 3 wk after infection, normalized for virus titer, and expressed relative to the activity of E5. Circles and triangles show independent experiments. Each symbol is the average of two plates of foci from a single infection. (G) C127 cells were infected with MSCV vector or MSCV expressing FLAG-tagged LI-5, polyL25, or a polyL25 clone with isoleucine inserted at the indicated position. After selection of puromycin-resistant cells, traptamer expression was determined by immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting with anti-FLAG antibody.

Fig. S8.

Valines do not rescue polyL25. C127 cells were infected with low-titer retrovius stocks of MSCV vector or MSCV expressing traptamer BPV E5, LI-11, polyL25-I8,13,22, or polyL25-V8,13,22. Focus-forming activity relative to E5 was determined and displayed as described in Fig. 1E.

Fig. S9.

Isoleucine at position 13 in polyL25 is required for focus formation. (A) C127 cells were infected with low-titer retrovirus stocks of MSCV vector or MSCV expressing untagged polyL25 containing a single isoleucine at position 11, 12, 13, 14, or 15. Plates were stained with Giemsa 3 wk later. (B) Quantitation of focus forming assays performed as in A for untagged polyL25 traptamers, normalized for virus titer and expressed relative to E5 activity. Circles and triangles show independent experiments. Each symbol is the average of two plates of foci from a single infection.

SI Materials and Methods

Cells and Retrovirus Production.

C127 and 293T cells and HFFs (obtained from the Yale Skin Diseases Research Center) were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) FBS, 2 mM l-glutamine, 20 mM Hepes, and antibiotics (penicillin-streptomycin). BaF3 cells were maintained in RPMI medium 1640 supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) heat-inactivated FBS, 6.6% (vol/vol) WEHI-3B cell-conditioned medium as a source of IL-3, 0.05 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and antibiotics (RPMI/IL-3). Calcium phosphate-mediated cotransfection of 10 μg retroviral plasmid DNA, 6 μg pCL-Eco, and 4 μg pVSVg into 2 × 106 293T cells in 10-cm dishes was used to produce retrovirus stocks (39). Forty-eight hours after transfection, supernatants were harvested and filtered through 0.45-μm filters. Virus stocks were used immediately or stored at −80 °C.

Retroviral Library Construction.

The UDv6 library was constructed using a long 5′ degenerate oligonucleotide (FWD long) consisting of a 5′ XhoI restriction site followed by a library-specific primer binding site for amplification, a methionine start codon, 25 degenerate codons encoding leucine and isoleucine, 2 tandem stop codons, a second library-specific primer binding site, and an EcoRI restriction site. The FWD long oligonucleotide was synthesized such that the randomized segment consisted of equimolar A and C in the first position of each codon, T in the second position, and equimolar A, C, and T in the third position. The randomized segment encodes an equimolar mixture of leucine and isoleucine. To convert the degenerate oligonucleotide to double-stranded DNA, the FWD long oligonucleotide was annealed to a nondegenerate 3′ oligonucleotide (REV long), which was complementary to the stop codons, 3′ primer binding site, and the EcoRI site. Extension was performed by a PCR consisting of 10 ng of each long oligonucleotide, Pfu reaction buffer, 0.2 mM dNTPs, and 1 μL Pfu Turbo polymerase (Agilent) in a total volume of 100 μL. PCR settings were 94 °C for 2 min; two cycles of 94 °C for 1 min, 38 °C for 1 min, and 72 °C for 1 min; and 72 °C for 10 min. To amplify the double-stranded DNA, short primers corresponding to the 5′ ends of the FWD and REV long oligonucleotides were added to the reaction at a final concentration of 500 nM, and PCR was conducted using the following settings: 94 °C for 5 min; 30 cycles of 94 °C for 1 min, 41 °C for 1 min, and 72 °C for 1 min; 72 °C for 10 min; incubate at 4 °C. The amplified products were digested with XhoI and EcoRI for 2 h, purified (QIAquick PCR Purification Kit, Qiagen), and ligated into the pMSCVpuro retroviral expression vector (Clontech), which contains a puromycin-resistance marker. The ligation reaction containing 1,432 ng of vector, 300 ng of insert, and 1 μL T4 DNA ligase (New England Biolabs) was incubated overnight at 16 °C and then purified as above. Electroporation was used to transform six 35-μL aliquots of DH10β Escherichia coli (Invitrogen) with 5 μL of the ligation, and each transformation was plated on a 15-cm LB-amp plate. Approximately 5,500,000 ampicillin-resistant colonies were pooled, and plasmid DNA was extracted and purified using the Nucelobond Xtra Midi kit (Clontech). The resulting library was named UDv6. To confirm the encoded amino acid composition and structures of clones in the library, DNA from randomly picked colonies was sequenced, revealing that 73% of unselected clones had the expected sequence structure.

Retroviral Library Recovery, Transformation, and Focus-Forming Assays.

To screen the UDv6 library for active traptamers, it was first converted into a retrovirus stock by transfection into 293T cells as described above. Ten 60-mm dishes of C127 cells at 70% confluence were infected with 3 mL of the UDv6 retrovirus library stock per dish with 4 μg/mL polybrene. After 24 h, the cells were split 1:2 and incubated at confluence for 2–3 wk with biweekly medium changes. Up to five transformed foci from each plate were isolated using cloning cylinders. Cells were expanded over five rounds until cells appeared uniformly morphologically transformed, and genomic DNA was isolated (DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit, Qiagen). Retroviral inserts in genomic DNA from transformed cells were amplified using the short primers specific to the library using the following PCR settings: 94 °C for 2 min; 30 cycles at 94 °C for 30 s, 62 °C for 30 s, and 67 °C for 30 s; 68 °C for 10 min; incubate at 4 °C. PCR products were purified, digested with EcoRI and XhoI, ligated into pMSCVpuro at a 1:10 molar ratio of vector to insert, and transformed by electroporation into DH5α E. coli. DNA was isolated from six colonies per focus and sequenced.

For transformation assays, retrovirus was produced as described above for each unique sequence recovered from transformed cells. To assess morphologic transformation, C127 and HFFs at 70% confluence in 60-mm dishes were infected with 1 mL of virus in 2 mL of medium containing 4 μg/mL of polybrene. One day later, the cells were passed 1:2 into a new 60-mm dish. After 7–10 d of incubation at confluence with biweekly media changes, cells were visualized microscopically. To measure focus formation, C127 cells in 60-mm dishes were infected as above except with 3 μL of virus. After 24 h, cells were split 1:3 and maintained at confluence for 2 to 3 wk with biweekly media changes. Foci were visualized by fixation in methanol followed by staining with a 5% (vol/vol) Giemsa solution (Sigma-Aldrich). To determine virus titer, ∼1% of the infected cells were plated into 100-mm dishes and incubated in medium containing 1.25 μg/mL puromycin. After all of the cells in the mock-infected culture died, colonies of virus-infected cells were stained with Giemsa as above and counted. The number of transformed foci was normalized to virus titer.

Mutagenesis and Cloning.

An N-terminal FLAG-tag followed by a triglycine linker (DYKDDDDKGGG) was inserted in-frame after the initiating methionine of active traptamers LI-7, LI-11, LI-5; two unselected traptamers (US2 and US16); polyL25; and polyL25 traptamers containing a single isoleucine at various positions by using gene blocks or mutagenic oliogonucleotides as described below. Clones expressing the polyL25, the codon optimized, and the premature stop codon traptamers were constructed using long oligonucleotides.

Gene blocks.

Gene blocks, designed to contain unique 5′ XhoI and 3′ EcoRI restriction sites, were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies. After reconstitution, gene blocks were digested with EcoRI and XhoI, purified (QIAquick kit), and ligated into pMSCVpuro at a 1:10 molar ration of vector to insert. Ligated DNA was then transformed into chemically competent DH10β E. coli (Life Technologies). Clones containing the appropriate insert were isolated and identified by sequencing.

Long oligonucleotides.

Long 5′ (FWD) and 3′ (REV) oligonucleotides (Integrated DNA technologies) were designed to be complementary except at their ends, which contained a unique XhoI and EcoRI site, respectively. Oligonucleotides (5 μM) were phosphorylated by incubating with 1 μM ATP and T4 polynucleotide kinase for 30 min at 37 °C, heated at 65 °C for 10 min to inactivate the kinase, and then annealed by slow cooling to room temperature. Annealed oligonucleotides were ligated into pMSCVpuro and cloned as described above.

Site-directed mutagenesis.

The QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis protocol (Agilent Technologies) was used to introduce amino acid substitution mutations in LI-5, LI-11, and polyL25. PCR was performed by using 125 ng of the FWD and REV primer, 50 ng of template plasmid, Pfu reaction buffer, 0.2 mM dNTPs, and 1 μL Pfu Turbo polymerase in a total volume of 50 μL. The following amplification settings were used: 95 °C for 2 min; 20 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, variable extension temperatures for 1 min, and 68 °C for 7.5 min; incubate at 4 °C. The temperature for extension was typically 5 °C less than the calculated Tm of the oligonucleotides. Products were digested with 1 μL DpnI at 37 °C for 1 h, then transformed into DH10β E. coli. Introduction of the designed mutation was confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Immunoprecipitation and Immunoblotting.

C127 cells stably expressing a traptamer or empty MSCVpuro were established by infecting cells in 60-mm dishes with 1 mL of retrovirus in 2 mL of medium containing 4 μg/mL polybrene. After 24 h, cells were passaged into 100-mm dishes and then selected in medium containing 1.25 μg/mL puromycin until the mock-infected cells died. After passage, cells at 80–90% confluence were serum-starved overnight, washed twice with PBS, and lysed in 1 mL of cold radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA)-Mops buffer [20 nM morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (pH 7.0), 150 mM NaCl, 1% deoxycholic acid, 0.1% SDS] for PDGFβR immunoprecipitation or l mL lysis buffer (50 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.4; 150 mM NaCl; 1% Triton X-100; 1 mM EDTA) for anti-FLAG immunoprecipitation. All lysis buffers contained Halt protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Thermo Scientific), 1 mM PMSF, and 0.5 mM sodium metavanadate.

For immunoprecipitation of the PDGFβR, lysates were incubated overnight at 4 °C with 5 μL anti-PDGFβR rabbit antiserum per milligram extracted protein followed by protein A Sepharose. For immunoprecipitation of FLAG-tagged traptamers, extracts were incubated overnight at 4 °C with 40 μL of the anti-FLAG M2 magnetic beads (Sigma-Aldrich, M8823) per sample according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Immunoprecipitates were washed three times in NETN buffer [100 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 8.0), 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.5% Nonidet P-40] supplemented with 1 mM PMSF and 0.5 mM sodium metavanadate, resuspended in 2× Laemmli sample buffer, boiled, and electrophoresed for 1.5–2 h at 150V on a 7.5% or 20% (wt/vol) polyacrylamide/SDS gel. Samples were transferred for 1.25 h at 100V to 0.45 μm nitrocellulose (to detect total or phosphorylated PDGFβR) or 0.2 μm polyvinylidene difluoride (to detect the FLAG-tag) in Tris/glycine transfer buffer [25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine, and 20% (vol/vol) methanol]. Transfer buffer supplemented with SDS to 0.1% was used for anti-PDGFβR and antiphosphotyrosine immunoblotting. Membranes were blocked in 5% (wt/vol) nonfat dry milk in TBST (10 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.4, 167 mM NaCl, 1% Tween-20) for 2 h and incubated overnight at 4 °C with antiphosphotyrosine antibody (PY100; Cell Signaling), anti-PDGFβR, or anti-FLAG antibody (Sigma-Aldrich), which were diluted 1:1,400, 1:500, and 1:5,000, respectively, in 5% (wt/vol) milk/TBST. Blots were washed 5× in TBST and incubated for 1 h at room temperature with HRP-conjugated donkey anti-mouse (Jackson ImmunoResearch; for antiphosphotyrosine and anti-FLAG blots) or HRP-protein A (GE Healthcare; for anti-PDGF receptor blots) diluted 1:10,000 or 1:7,000, respectively, in 5% (wt/vol) milk/TBST. Blots were then washed and visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate, Thermo Scientific).

BaF3 cells stably expressing PDGFβR or βαβ were established by retroviral infection and G418 selection (see next section), and then traptamers were introduced into them by retroviral infection and puromycin selection. Cells were maintained in the presence of IL-3 and 30 ng/mL PDGF-BB. Next, 107 cells were collected, washed twice with PBS, lysed and subjected to coimmunoprecipitation according to the anti-FLAG protocol described above.

For the phospho-RTK arrays, normal HFFs or HFFs stably expressing LI-5, LI-8, LI-11, polyL25-I8,13,22, or polyL25-I13 traptamer or the MSCV empty vector were grown to confluence in 100-mm dishes and serum-starved overnight. In addition, unmanipulated serum-starved HFFs were incubated at room temperature for 10 min with PDGF-DD (25 ng/mL; R & D Systems) or a mixture of growth factors [25 ng/mL PDGF-BB (EMD Millipore), 40 ng/mL epidermal growth factor (EGF, provided by David Stern, Yale University, New Haven, CT), 40 ng/mL fibroblast growth factor (FGF, provided by Joseph Schlessinger, Yale University, New Haven, CT), 20 ng/mL neuregulin 1 (NRG1, provided by David Stern), 40 ng/mL human stem cell factor (SCF, ConnStem), 40 ng/mL protein Pros 1 (provided by Carla Rothlin, Yale University, New Haven, CT), and 40 ng/mL insulin (Sigma) in 50% (vol/vol) FBS] and then lysed. All steps thereafter were performed as described in the Human Phospho-RTK Array Kit (Proteome Profiler, R&D Systems). Briefly, the cells were lysed in the provided lysis buffer supplemented with HALT protease inhibitors, 1 mM PMSF, and 0.5 mM sodium metavanadate. Lysates were then incubated with the phospho-RTK array membranes overnight. After washing, the membranes were incubated with the anti-phospho-tyrosine-HRP detection antibody for 2 h, washed, and then visualized with the provided Chemiluminescence Reagent Mix.

IL-3 Independence Assay.

BaF3 cells stably expressing a receptor with or without traptamer, E5, or v-sis were generated as follows: first, 500,000 BaF3 cells in a T25 flask were infected in medium containing 4 μg/mL polybrene and 1 mL of LXSN retrovirus vector (which contains a G418 resistance marker) or LXSN expressing the wild-type PDGFβR, PDGFβR containing a mutant transmembrane domain, or the PDGFαR transmembrane domain [βαβ (40)], c-kit, or the human erythropoietin receptor (22). Five hours later, 8 mL of RPMI/IL-3 medium was added to each flask, and the cells were incubated overnight. Cells were then selected in RPMI/IL3 medium containing 1 mg/mL G418. Five to 7 d later, when the mock-infected cells died, cells were infected as described above with empty MSCVpuro or MSCVpuro expressing a traptamer, BPV E5, or v-sis and selected in medium containing 1 μg/mL puromycin. To assay for IL-3 independent proliferation, 5 × 105 G418- and puromycin-resistant cells were washed three times with PBS and incubated in 10 mL RPMI without IL-3 containing 2.5% (vol/vol) heat-inactivated FBS, 0.05 mM β mercaptoethanol, 250 μg/mL G418, 0.25 μg/mL puromycin, and antibiotics. As positive controls, cells expressing EpoR or c-kit were treated with 0.5 units per milliliter human erythropoietin (Epogen, Amgen) or 100 ng/mL human SCF, respectively, replenished every 2 to 3 d for the duration of the IL3-independence assay. The ligand control for PDGFβR cells was expressed v-sis. Live cells were counted at various times after IL-3 removal.

Molecular Modeling.

As an initial starting template for traptamer structures, we used an ideal α-helix backbone conformation (ϕ = −57.8 and ψ = −47.0) inserted in a POPC bilayer. The system was built using the graphical user interface for Chemistry at Harvard Molecular Mechanics, CHARMM-GUI (41). Each system consisted of a single traptamer, 144 POPC molecules (72 in each leaflet), and 5,760 water molecules, resulting in a total of 37,097 atoms for LI-11 and LI-11-I13L, and 37,094 atoms for LI-11-I13V, and a simulation cell size of 72 × 72 × 78 Å. Each helix was initially positioned in the center of the membrane with its axis perpendicular to the membrane surface and equilibrated. First, each system was minimized for 6,000 steps, followed by a 2-ns pre-equilibration simulation, with constraints on heavy atoms, at a temperature of 300 °K and with fixed volume. The heavy atom constraints were gradually released, and the models were then observed using a simulation run of 150 ns at a constant pressure of 1 atm and a temperature of 300 °K.

The simulations were performed using the NAMD 2.9 software (42). The CHARMM36 force fields (43) were used for protein and lipids and the TIP3P model 39 was used for the water molecules (44). The short-range interaction cut-off was set at 12 Å. The smooth particle mesh Ewald method (45) was used to calculate electrostatic interactions and a reversible multiple time-step algorithm (46) was used to integrate the equations of motion with time steps of 1 fs and 2 fs for bonded forces and short-range nonbonded or electrostatic forces, respectively. A Noseì–Hoover–Langevin piston and a Langevin dynamics scheme (47, 48) were used for pressure and temperature control, respectively.

Molecular graphics were performed with VMD 1.9.1 (49). The trajectories were analyzed for the last 12 ns of each trajectory.

Oligonucleotides for Library Construction and Recovery and for Mutant Construction.

Library construction and recovery.

FWD long: gcctctcgagtggtcaacggttaacaccatg mth mth mth mth mth mth mth mth mth mth mth mth mth mth mth mth mth mth mth mth mth mth mth mth mth tagtagagtactggatcc

(m is A:C at 1:1; h is A:C:T at 1:1:1)

REV long: ccttgaattcgtgacctctggatccagtactctacta

FWD short: gtaggtgcctctcgagtggtcaacggttaac

REV short: tgctgcccttgaattcgtgacctctggatcc

LI-5 site-directed mutagenesis.

L2I FWD: ggtcaacggttaacaccatgattctaatcatcctaattatcc

L2I REV: ggataattaggatgattagaatcatggtgttaaccgttgacc

L3I FWD: gtcaacggttaacaccatgcttataatcatcctaattatccttct

L3I REV: agaaggataattaggatgattataagcatggtgttaaccgttgac

I4L FWD: caacggttaacaccatgcttctactcatcctaattatccttct

I4L REV: agaaggataattaggatgagtagaagcatggtgttaaccgttg

I5L FWD: aacggttaacaccatgcttctaatcctcctaattatccttcttatac

I5L REV: gtataagaaggataattaggaggattagaagcatggtgttaaccgtt

L6I FWD: ggttaacaccatgcttctaatcatcataattatccttcttatactaattct

L6I REV: agaattagtataagaaggataattatgatgattagaagcatggtgttaacc

I7L FWD: aacaccatgcttctaatcatcctacttatccttcttatactaattctac

I7L REV: gtagaattagtataagaaggataagtaggatgattagaagcatggtgtt

I8L FWD: gttaacaccatgcttctaatcatcctaattctccttcttatactaattc

I8L REV: gaattagtataagaaggagaattaggatgattagaagcatggtgttaac

L9I FWD: catgcttctaatcatcctaattatcattcttatactaattctacttctcct

L9I REV: aggagaagtagaattagtataagaatgataattaggatgattagaagcatg

L10I FWD: gcttctaatcatcctaattatccttattatactaattctacttctcctact

L10I REV: agtaggagaagtagaattagtataataaggataattaggatgattagaagc

I11L FWD: gtaggagaagtagaattagtagaagaaggataattaggatgattagaag

I11L REV: cttctaatcatcctaattatccttcttctactaattctacttctcctac

L12I FWD: tctaatcatcctaattatccttcttataataattctacttctcctactcattc

L12I REV: gaatgagtaggagaagtagaattattataagaaggataattaggatgattaga

I13L FWD: ttctaatcatcctaattatccttcttatactacttctacttctcctactc

I13L REV: gagtaggagaagtagaagtagtataagaaggataattaggatgattagaa

L14I FWD: gaatgagtaggagaagtataattagtataagaaggataattaggatgattaga

L14I REV: tctaatcatcctaattatccttcttatactaattatacttctcctactcattc

L15I FWD: aatcatcctaattatccttcttatactaattctaattctcctactcattcttc

L15I REV: gaagaatgagtaggagaattagaattagtataagaaggataattaggatgatt

L16I FWD: catcctaattatccttcttatactaattctacttatcctactcattcttctaat

L16I REV: attagaagaatgagtaggataagtagaattagtataagaaggataattaggatg

L17I FWD: cttcttatactaattctacttctcatactcattcttctaatactcctac

L17I REV: gtaggagtattagaagaatgagtatgagaagtagaattagtataagaag

L18I FWD: cttcttatactaattctacttctcctaatcattcttctaatactcctacta

L18I REV: tagtaggagtattagaagaatgattaggagaagtagaattagtataagaag

I19L FWD: tactaattctacttctcctactccttcttctaatactcctactactc

I19L REV: gagtagtaggagtattagaagaaggagtaggagaagtagaattagta

L20I FWD: ctaattctacttctcctactcattattctaatactcctactactctag

L20I REV: ctagagtagtaggagtattagaataatgagtaggagaagtagaattag

L21I FWD: ttctacttctcctactcattcttataatactcctactactctagtag

L21I REV: ctactagagtagtaggagtattataagaatgagtaggagaagtagaa

I22L FWD: ctacttctcctactcattcttctactactcctactactctagt

I22L REV: actagagtagtaggagtagtagaagaatgagtaggagaagtag

L23I FWD: ttctacttctcctactcattcttctaataatcctactactctagta

L23I REV: tactagagtagtaggattattagaagaatgagtaggagaagtagaa

L24I FWD: cctactcattcttctaatactcatactactctagtagagtactgg

L24I REV: ccagtactctactagagtagtatgagtattagaagaatgagtagg

L25I FWD: tactcattcttctaatactcctaatactctagtagagtactggatc

L25I REV: gatccagtactctactagagtattaggagtattagaagaatgagta

L26I FWD: tcattcttctaatactcctactaatctagtagagtactggatcc

L26I REV: ggatccagtactctactagattagtaggagtattagaagaatga

I13V FWD: ttctaatcatcctaattatccttcttatactagttctacttctcctactc

I13V REV: gagtaggagaagtagaactagtataagaaggataattaggatgattagaa

LI-11 site-directed mutagenesis.

L2I FWD: gtggtcaacggttaacaccatgattctcataatacttctaataatc

L2I REV: gattattagaagtattatgagaatcatggtgttaaccgttgaccac

L3I FWD: attattagaagtattatgataagcatggtgttaaccgttgaccact

L3I REV: agtggtcaacggttaacaccatgcttatcataatacttctaataat

I4L FWD: caacggttaacaccatgcttctcctaatacttctaataatcattatcc

I4L REV: ggataatgattattagaagtattaggagaagcatggtgttaaccgttg

I5L FWD: cggttaacaccatgcttctcatactacttctaataatcattatcctt

I5L REV: aaggataatgattattagaagtagtatgagaagcatggtgttaaccg

L6I FWD: caacggttaacaccatgcttctcataataattctaataatcattatcctta

L6I REV: taaggataatgattattagaattattatgagaagcatggtgttaaccgttg

L7I FWD: gttaacaccatgcttctcataatacttataataatcattatccttatcctactta

L7I REV: taagtaggataaggataatgattattataagtattatgagaagcatggtgttaac

I8L FWD: caccatgcttctcataatacttctactaatcattatccttatcctacttat

I8L REV: ataagtaggataaggataatgattagtagaagtattatgagaagcatggtg

I9L FWD: gttaacaccatgcttctcataatacttctaatactcattatccttatccta

I9L REV: taggataaggataatgagtattagaagtattatgagaagcatggtgttaac

I10L FWD: ccatgcttctcataatacttctaataatccttatccttatcctacttatact

I10L REV: agtataagtaggataaggataaggattattagaagtattatgagaagcatgg

I11L FWD: acaccatgcttctcataatacttctaataatcattctccttatcctacttatac

I11L REV: gtataagtaggataaggagaatgattattagaagtattatgagaagcatggtgt

L12I FWD: aagaagtagtatgagtataagtaggataatgataatgattattagaagtattatgagaa

L12I REV: ttctcataatacttctaataatcattatcattatcctacttatactcatactacttctt

I13L FWD: gcttctcataatacttctaataatcattatccttctcctacttatactcatac

I13L REV: gtatgagtataagtaggagaaggataatgattattagaagtattatgagaagc

L14I FWD: gaggataagaagtagtatgagtataagtatgataaggataatgattattagaagtatta

L14I REV: taatacttctaataatcattatccttatcatacttatactcatactacttcttatcctc

L15I FWD: ggaggataagaagtagtatgagtataattaggataaggataatgattattagaag

L15I REV: cttctaataatcattatccttatcctaattatactcatactacttcttatcctcc

I16L FWD: tcataatacttctaataatcattatccttatcctacttctactcatactacttcttatc

I16L REV: gataagaagtagtatgagtagaagtaggataaggataatgattattagaagtattatga

L17I FWD: ataatacttctaataatcattatccttatcctacttataatcatactacttcttatcctc

L17I REV: gaggataagaagtagtatgattataagtaggataaggataatgattattagaagtattat

I18L FWD: ttatccttatcctacttatactcctactacttcttatcctcctactc

I18L REV: gagtaggaggataagaagtagtaggagtataagtaggataaggataa

L19I FWD: ggagtaggaggataagaagtattatgagtataagtaggataagg

L19I REV: ccttatcctacttatactcataatacttcttatcctcctactcc

L20I FWD: tcattatccttatcctacttatactcatactaattcttatcctcctactc

L20I REV: gagtaggaggataagaattagtatgagtataagtaggataaggataatga

L21I FWD: ctactaaaggagtaggaggataataagtagtatgagtataagtagga

L21I REV: tcctacttatactcatactacttattatcctcctactcctttagtag

I22L FWD: ccttatcctacttatactcatactacttcttctcctcctactccttta

I22L REV: taaaggagtaggaggagaagaagtagtatgagtataagtaggataagg

L23I FWD: agtactctactaaaggagtaggatgataagaagtagtatgagtataa

L23I REV: ttatactcatactacttcttatcatcctactcctttagtagagtact

L24I FWD: cagtactctactaaaggagtatgaggataagaagtagtatgag

L24I REV: ctcatactacttcttatcctcatactcctttagtagagtactg

L25I FWD: cagtactctactaaaggattaggaggataagaagtagtatgagt

L25I REV: actcatactacttcttatcctcctaatcctttagtagagtactg

L26I FWD: ggatccagtactctactaaatgagtaggaggataagaagta

L26I REV: tacttcttatcctcctactcatttagtagagtactggatcc

I8V FWD: caccatgcttctcataatacttctagtaatcattatccttatcctacttat

I8V REV: ataagtaggataaggataatgattactagaagtattatgagaagcatggtg

I13V FWD: gcttctcataatacttctaataatcattatccttgtcctacttatactcatac

I13V REV: gtatgagtataagtaggacaaggataatgattattagaagtattatgagaagc

I22V FWD: ccttatcctacttatactcatactacttcttgtcctcctactccttta

I22V REV: taaaggagtaggaggacaagaagtagtatgagtataagtaggataagg

Codon optimization and premature stop codon insertion.

LI-7 codon-optimized FWD: tcgagaccatgctcataatcttgatcctcctgttgctcttgctgttgattctgattcttctcatcctgctcctttgatagg

LI-7 codon-optimized REV: aattcctatcaaaggagcaggatgagaagaatcagaatcaacagcaagagcaacaggaggatcaagattatgagcatggtc

LI-7 premature-stop codon FWD: tcgagaccatgctcataatcttgatcctcctgttgctcttgctgttgattctgtgatagg

LI-7 premature-stop codon REV: aattcctatcacagaatcaacagcaagagcaacaggaggatcaagattatgagcatggtc

LI-11 codon-optimized FWD: tcgagaccatgctgctcattatcctcctgattatcataattcttatcctgttgatactgatcctccttttgattcttctcctgctgtagtagg

LI-11 codon-optimized REV: aattcctactacagcaggagaagaatcaaaaggaggatcagtatcaacaggataagaattatgataatcaggaggataatgagcagcatggtc

LI-11 premature-stop codon FWD: tcgagaccatgctgctcattatcctcctgattatcataattcttatctagtagg

LI-11 premature-stop codon REV: aattcctactagataagaattatgataatcaggaggataatgagcagcatggtc

Insertion of FLAG-tag.

LI-7 Long Oligo FWD: tcgagaccatggactacaaggacgacgatgacaagggcgggggactcctactccttcttattatacttctacttcttattcttattatactcctcctccttctcctacttctacttctctagtagg

LI-7 Long Oligo REV: aattcctactagagaagtagaagtaggagaaggaggaggagtataataagaataagaagtagaagtataataagaaggagtaggagtcccccgcccttgtcatcgtcgtccttgtagtccatggtc

LI-11 Long Oligo FWD: tcgagaccatggactacaaggacgacgatgacaagggcgggggacttctcataatacttctaataatcattatccttatcctacttatactcatactacttcttatcctcctactcctttagtagg

LI-11 Long Oligo REV: ctactaaaggagtaggaggataagaagtagtatgagtataagtaggataaggataatgattattagaagtattatgagaagtcccccgcccttgtcatcgtcgtccttgtagtccatggtc

US 16 Gene Block: gattactcgagaccatggactacaaggacgacgatgacaagggcgggggattgctgctcctccttattattctcttgctgctgattctcttgattatcctgattctcatcattttgattctcatctagtaggaattcatatc

US 21 Gene Block: gattactcgagaccatggactacaaggacgacgatgacaagggcgggggacttctgctcatcctgctgatactcattctcctgattctgttgattatcatcattctgatcctgatcttgcttctctagtaggaattcatatc

LI-5 FLAG tag Gene Block:

gattactcgagaccatggactacaaggacgacgatgacaagggcgggggacttctaatcatcctaattatccttcttatactaattctacttctcctactcattcttctaatactcctactactctagtaggaattcatatc

Construction of untagged polyleucine clones.

PolyLeucine Long Oligo FWD: tcgagaccatgctcctattattgctcctcctgttgctcttgctgttgcttctgctgcttctcttactgctcctttgatagg

PolyLeucine Long Oligo REV: aattcctatcaaaggagcagtaagagaagcagcagaagcaacagcaagagcaacaggaggagcaataataggagcatggtc

pL-8,13,22 Long Oligo FWD: tcgagaccatgcttctcctactacttctaatactccttctccttatcctacttctactcctactacttcttatcctcctactcctttagtagg

pL-8,13,22 Long Oligo REV: aattcctactaaaggagtaggaggataagaagtagtaggagtagaagtaggataaggagaaggagtattagaagtagtaggagaagcatggtc

pL-8,13 FWD: cctacttctactcctactacttcttctcctcctactcct

pL-8,13 REV: aggagtaggaggagaagaagtagtaggagtagaagtagg

pL-8,22 FWD: ctactacttctaatactccttctccttctcctacttctactc

pL-8,22 REV: gagtagaagtaggagaaggagaaggagtattagaagtagtag

pL-13,22 FWD: accatgcttctcctactacttctactactccttctcct

pL-13,22REV: aggagaaggagtagtagaagtagtaggagaagcatggt

pL-I8 FWD: ctgctcttgctcctgcttatcctcctgcttttgctgc

pL-I8 REV: gcagcaaaagcaggaggataagcaggagcaagagcag

pL-I13 FWD: ctgctcctgcttttgatcctgctcctgctcctc

pL-I13 REV: gaggagcaggagcaggatcaaaagcaggagcag

pL-I22 FWD: gctcctcttgctcctgatcctcttgctcttgta

pL-I22 REV: tacaagagcaagaggatcaggagcaagaggagc

pL-I11 FWD: cctgcttctgctcctgattttgctgctgctcctg

pL-I11 REV: caggagcagcagcaaaatcaggagcagaagcagg

pL-I12 FWD: ctgcttctgctcctgcttatcctgctgctcctgctcctc

pL-I12 REV: gaggagcaggagcagcaggataagcaggagcagaagcag

pL-I14 FWD: ctgctcctgcttttgctgatcctcctgctcctcttgctc

pL-I14 REV: gagcaagaggagcaggaggatcagcaaaagcaggagcag

pL-I15 FWD: ctcctgcttttgctgctgatcctgctcctcttgctcctg

pL-I15 REV: caggagcaagaggagcaggatcagcagcaaaagcaggag

Construction of FLAG-tagged polyleucine clones.

FLAG-pL-I11 gene block: gattactcgagaccatggactacaaggacgacgatgacaagggcgggggactgctcttgctcctgcttctgctcctgattttgctgctgctcctgctcctcttgctcctgctcctcttgctcttgtgataggaattcatatc

FLAG-pL-I12 FWD: gcttctgctcctgcttatcctgctgctcctgct

FLAG-pL-I12 REV: agcaggagcagcaggataagcaggagcagaagc

FLAG-pL-I13 FWD: cttctgctcctgcttttgatactgctcctgctcctcttg

FLAG pL-I13 REV: caagaggagcaggagcagtatcaaaagcaggagcagaag

To construct FLAG-pL-I14 and -I15, the same primers were used as for untagged pL-I14 and pL-I15 with a FLAG-tagged template.

Discussion

We have used a genetic selection to isolate exceptionally simple 26-amino acid proteins with specific biological activity. Remarkably, these proteins contain only leucine and isoleucine and appear to consist of only a single transmembrane helix. Leucine and isoleucine side-chains differ only in the position of a methyl group, lack chemically reactive groups, and are not subject to posttranslational modification. Despite their chemical simplicity, these proteins specifically activate the endogenous PDGFβR but no other receptors in transformed cells, and they confer growth factor independence in cooperation with wild-type PDGFβR but not with other receptors or mutant PDGFβRs containing substitutions in the transmembrane region. In addition, conservative amino acid substitutions at specific positions in the traptamers inhibit activity without affecting the overall structure of the helix, and repositioning a single side-chain methyl group at position 13 from the γ-carbon to the β-carbon (thereby converting leucine to isoleucine)—but not at other positions—in an otherwise monotonous inactive protein is sufficient to generate biological activity.

Our results strongly suggest that traptamers consisting of only leucine and isoleucine can induce cell transformation by selectively interacting in a sequence-specific manner with the transmembrane domain of a cellular protein, most likely the PDGFβR itself, resulting in specific activation of the receptor. Indeed, we showed that the active traptamers but not a defective mutant are present in a stable complex with the wild-type PDGFβR but not with a chimeric PDGFβR containing a foreign transmembrane domain. The specificity of the traptamers suggests that they are unlikely to transform cells by forming aggregates that cause nonspecific receptor clustering. Thus, they differ from repeat-associated non-ATG (RAN) translation products, simple naturally occurring proteins translated in multiple reading frames from trinucleotide or hexanucleotide gene expansions, which cause neurologic disease by nonspecific aggregation and induction of cell toxicity (36). Determining how traptamers with such a limited chemical repertoire specifically recognize a target transmembrane domain will provide new insights into the structural basis for protein–protein recognition. Because leucine and isoleucine side-chains can participate in packing interactions only, further study of these traptamers will provide a focused view of this important class of interactions in the absence of alternative binding solutions provided by chemically diverse side-chains.

These short, simple proteins can be subjected to a level of mutational analysis that would be difficult if not impossible with conventional proteins. A leucine at certain positions in traptamers LI-5 and LI-11 is required for activity, and an isoleucine is required at certain other positions. Whether or not an amino acid is required at a particular position is determined in part by its context. For example, the isoleucines at position 8 and 22 are required in LI-11 but not in LI-5, even though both traptamers contain isoleucine at these positions. Interestingly, none of the positions that differ between LI-5 and LI-11 are required for high activity of either traptamer (Fig. 3C). Thus, the amino acids at nonessential positions can dictate whether an amino acid at a shared position is required for optimal activity, presumably by affecting the packing of the helices.

Our mutational analysis also indicated that not all required amino acids are equivalent: the isoleucines at position 8 and 22 in LI-11 cannot be replaced by leucine but can be replaced by valine, which like isoleucine is a β-branched amino acid, suggesting that rotational restriction of a β-branched side-chain at these positions, rather than the isoleucine side-chain per se, is important for LI-11 activity. In contrast, the isoleucine at position 13 in LI-5 and LI-11 cannot be replaced with valine or leucine without loss of activity, implying that the isoleucine side-chain at position 13 makes specific packing contacts essential for transforming activity. The very similar structures of valine, leucine, and isoleucine imply that the terminal methyl group of Ile13 makes an essential packing contact that is missing from the valine mutant. Furthermore, the second terminal methyl group in leucine may sterically clash with its binding partner, or an essential methyl group on the β-carbon may be missing in the leucine mutant.

Single amino acid mutations can have dramatic effects on transmembrane domain interactions. For example, a leucine to isoleucine mutation at position 512 in the transmembrane domain of the PDFGFβR disrupts the direct interaction between the PDGFβR and the E5 protein, preventing transformation (17). Binding energy contributions from contacts at transmembrane helical interfaces have been measured, for example by Fleming et al. (37), who studied the homodimeric interaction of the GlycophorinA transmembrane domain. This study showed the free energy of dissociation of the wild-type dimer is 9 kcal/mol, and that the disruptive L75A and I76A substitutions decrease affinity by 1.1 kcal/mol and 1.7 kcal/mol, respectively. These changes were attributed to changes in van der Waals interactions between the helices. Although it has been suggested that these energies, measured with peptides in detergent micelles, overestimate energies in membranes (38), a change of only ∼1.3 kcal/mol is sufficient to change a “strong” to a “weakly associated” transmembrane dimer (33), probably as a result of constraints imposed by the helical conformation in the lipid bilayer. The limited rotation of isoleucine compared with leucine may make an additional, entropic contribution to binding energy.

It is remarkable that polyL25 is activated by isoleucine at position 13, activated poorly by isoleucine at position 12 or 14, and not activated by isoleucine at position 11 or 15, because in all cases the single isoleucine is embedded in a long stretch of leucines. Thus, an isoleucine near the middle of the lipid bilayer is required for traptamer activity, and activity drops the farther the isoleucine is from this central position. The match between the hydrophobic profile of the helix and the hydrophobic profile of the membrane stabilizes the position of a transmembrane helix across a membrane with respect to the displacement of the helix perpendicular to the plane of the membrane. The pattern of activity of the polyL25 add-back traptamers implies that there is a permitted range of helix displacements across the membrane. A displacement from the free-energy minimum will cost energy, and when the displacement energy exceeds the energy of binding of the critical isoleucine with its target, the productive interaction will be lost. We speculate that the isoleucine side-chain at position 13 makes an essential packing contact with the hydrophilic threonine residue at position 513 in the middle of the PDGFβR transmembrane domain, a residue that is required for traptamer activity (Fig. 2D) and is proposed to interact directly with Gln17 of the E5 protein (21). Alternatively, these traptamers may act as homodimers, and Ile13 may allow the self-association of two molecules of the traptamer to generate an active dimer.

Our results demonstrate that proteins consisting of only two different amino acids can display specific biological activity. This finding raises a number of interesting questions, which are under investigation. Do the active traptamers bind directly to the PDGFβR transmembrane domain or do they merely exist in a stable complex that contains the PDGFβR as well as other transmembrane proteins? Is the PDGFβR uniquely susceptible to activation by these ultrasimple traptamers, or can similar proteins modulate the activity of other cellular target proteins? Can similar approaches be used to isolate simple biologically active soluble proteins? Can such simple proteins serve as models for the design of biologically active peptides and peptidomimetic molecules? Do extant genomes encode similar simple biologically active proteins, or did such proteins exist in primordial times before the full complement of amino acids was available? Our results change the view of what can constitute an active protein.

Materials and Methods

Detailed experimental methods are presented in SI Materials and Methods.

Retroviral Library Construction.

The UDv6 library was constructed by using degenerate oligonucleotides containing library-specific primer binding sites for amplification, a methionine start codon, and 25 degenerate codons encoding equimolar leucine and isoleucine followed by stop codons. To synthesize the randomized segment, equimolar A and C were used in the first position of each codon, T was used in the second position, and equimolar A, C, and T were used in the third position. After primer extension and amplification, the amplification products were ligated into pMSCVpuro retroviral expression vector and transformed into DH10β Escherichia coli. Plasmid DNA was harvested from ∼5,500,000 pooled ampicillin-resistant colonies. Further details are in SI Materials and Methods.

IL-3 Independence Assay.

BaF3 lines stably expressing a receptor were generated by infecting BaF3 cells with retrovirus containing a receptor gene cloned in the pLXSN retroviral vector and selection for G418 resistance. The resulting stable cell lines were infected with empty MSCVpuro, or MSCVpuro expressing a traptamer, E5 or v-sis, and selected with puromycin. To assay for IL-3 independent proliferation, washed cells were incubated in RPMI lacking IL-3. Some samples expressing EpoR or c-kit were treated with human erythropoietin or human stem cell factor, respectively. Further details are in SI Materials and Methods.

RTK Array.

HFFs were infected with MSCV empty vector or viruses expressing a traptamer and selected in puromycin. Cells were serum-starved overnight before harvest. Some control samples were incubated with PDGF-DD or with a mixture of growth factors consisting of PDGF-BB, epidermal growth factor, fibroblast growth factor, neuregulin 1, stem cell factor, Sros 1, and insulin in 50% (vol/vol) FBS before lysis. All subsequence steps were performed as described in the Human Phospho-RTK Array Kit (Proteome Profiler, R&D Systems). Briefly, the cells were lysed in the provided lysis buffer with protease and phosphatase inhibitors, then incubated with the nitrocellulose membranes overnight. Membranes were then incubated with the anti-Phospho-Tyrosine-HRP detection antibody and visualized with Chemi Reagent Mix. Further details are in SI Materials and Methods.

Cloning, Tissue Culture, and Biochemical Analysis.

Standard procedures were used for tissue culture, retrovirus production, cloning, immunoprecipitation, and immunoblotting. See SI Materials and Methods for details.

Acknowledgments

We thank Emily Cohen and Kelly Chacon for helpful discussions; the Douglas Tobias (University of California, Irvine) group for guidance with the Molecular Dynamics simulations; and Jan Zulkeski for assistance in preparing this manuscript. This study was supported in part by National Institutes of Health training Grants T32GM007499 (to E.N.H.) and T32GM007223 (to R.S.F.); National Institutes of Health Grants CA037157 (to D.D.) and GM073857 (to D.M.E.); and by generous gifts from Ms. Laurel Schwartz (to D.D.). Computational modeling used the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment was supported by National Science Foundation Grant ACI-1053575 (to D.M.E.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1514230112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Rennell D, Bouvier SE, Hardy LW, Poteete AR. Systematic mutation of bacteriophage T4 lysozyme. J Mol Biol. 1991;222(1):67–88. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90738-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheek S, Zhang H, Grishin NV. Sequence and structure classification of kinases. J Mol Biol. 2002;320(4):855–881. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00538-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hamburger ZA, Brown MS, Isberg RR, Bjorkman PJ. Crystal structure of invasin: A bacterial integrin-binding protein. Science. 1999;286(5438):291–295. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5438.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lehnert U, et al. Computational analysis of membrane proteins: Genomic occurrence, structure prediction and helix interactions. Q Rev Biophys. 2004;37(2):121–146. doi: 10.1017/s003358350400397x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mackenzie KR. Folding and stability of alpha-helical integral membrane proteins. Chem Rev. 2006;106(5):1931–1977. doi: 10.1021/cr0404388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moore DT, Berger BW, DeGrado WF. Protein-protein interactions in the membrane: Sequence, structural, and biological motifs. Structure. 2008;16(7):991–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Popot JL, Engelman DM. Helical membrane protein folding, stability, and evolution. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000;69:881–922. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schneider D, Finger C, Prodöhl A, Volkmer T. From interactions of single transmembrane helices to folding of alpha-helical membrane proteins: Analyzing transmembrane helix-helix interactions in bacteria. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2007;8(1):45–61. doi: 10.2174/138920307779941578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bargmann CI, Hung MC, Weinberg RA. Multiple independent activations of the neu oncogene by a point mutation altering the transmembrane domain of p185. Cell. 1986;45(5):649–657. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90779-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yin H, et al. Computational design of peptides that target transmembrane helices. Science. 2007;315(5820):1817–1822. doi: 10.1126/science.1136782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DiMaio D. Viral miniproteins. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2014;68:21–43. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-091313-103727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hofmann MW, et al. De novo design of conformationally flexible transmembrane peptides driving membrane fusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(41):14776–14781. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405175101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lear JD, Wasserman ZR, DeGrado WF. Synthetic amphiphilic peptide models for protein ion channels. Science. 1988;240(4856):1177–1181. doi: 10.1126/science.2453923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burkhardt A, DiMaio D, Schlegel R. Genetic and biochemical definition of the bovine papillomavirus E5 transforming protein. EMBO J. 1987;6(8):2381–2385. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02515.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DiMaio D, Guralski D, Schiller JT. Translation of open reading frame E5 of bovine papillomavirus is required for its transforming activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83(6):1797–1801. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.6.1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schlegel R, Wade-Glass M, Rabson MS, Yang Y-C. The E5 transforming gene of bovine papillomavirus encodes a small, hydrophobic polypeptide. Science. 1986;233(4762):464–467. doi: 10.1126/science.3014660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edwards AP, Xie Y, Bowers L, DiMaio D. Compensatory mutants of the bovine papillomavirus E5 protein and the platelet-derived growth factor β receptor reveal a complex direct transmembrane interaction. J Virol. 2013;87(20):10936–10945. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01475-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lai CC, Henningson C, DiMaio D. Bovine papillomavirus E5 protein induces oligomerization and trans-phosphorylation of the platelet-derived growth factor beta receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(26):15241–15246. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petti L, DiMaio D. Stable association between the bovine papillomavirus E5 transforming protein and activated platelet-derived growth factor receptor in transformed mouse cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89(15):6736–6740. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.15.6736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petti L, Nilson LA, DiMaio D. Activation of the platelet-derived growth factor receptor by the bovine papillomavirus E5 transforming protein. EMBO J. 1991;10(4):845–855. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb08017.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Talbert-Slagle K, DiMaio D. The bovine papillomavirus E5 protein and the PDGF β receptor: It takes two to tango. Virology. 2009;384(2):345–351. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cammett TJ, et al. Construction and genetic selection of small transmembrane proteins that activate the human erythropoietin receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(8):3447–3452. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0915057107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Freeman-Cook LL, DiMaio D. Modulation of cell function by small transmembrane proteins modeled on the bovine papillomavirus E5 protein. Oncogene. 2005;24(52):7756–7762. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Freeman-Cook LL, et al. Selection and characterization of small random transmembrane proteins that bind and activate the platelet-derived growth factor beta receptor. J Mol Biol. 2004;338(5):907–920. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chacon KM, et al. De novo selection of oncogenes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(1):E6–E14. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1315298111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bergsten E, et al. PDGF-D is a specific, protease-activated ligand for the PDGF beta-receptor. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3(5):512–516. doi: 10.1038/35074588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Drummond-Barbosa DA, Vaillancourt RR, Kazlauskas A, DiMaio D. Ligand-independent activation of the platelet-derived growth factor beta receptor: requirements for bovine papillomavirus E5-induced mitogenic signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15(5):2570–2581. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.5.2570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Palacios R, Steinmetz M. Il-3–dependent mouse clones that express B-220 surface antigen, contain Ig genes in germ-line configuration, and generate B lymphocytes in vivo. Cell. 1985;41(3):727–734. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(85)80053-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nappi VM, Schaefer JA, Petti LM. Molecular examination of the transmembrane requirements of the platelet-derived growth factor beta receptor for a productive interaction with the bovine papillomavirus E5 oncoprotein. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(49):47149–47159. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209582200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]