Significance

Mechanosensation underlies fundamental biological processes, including osmoregulation in microbes, touch and hearing in animals, and gravitropism and turgor pressure sensing in plants. The microbial large-conductance mechanosensitive channel (MscL) functions as a pressure-relief valve during hypoosmotic shock. MscL represents an ideal model system for investigating the molecular mechanism of the mechanical force transduction process. By solving and comparing the structures of an archaeal MscL in two different conformational states, we have revealed coordinated movements of the different domains of the MscL channel. Through this study, direct insights into the physical principle of the mechanical coupling mechanism, which coordinates the multiple structural elements of this highly sophisticated nanoscale valve, have been established.

Keywords: mechanosensitive channel, gating mechanism, crystal structure, membrane protein, osmoregulation

Abstract

The prokaryotic mechanosensitive channel of large conductance (MscL) is a pressure-relief valve protecting the cell from lysing during acute osmotic downshock. When the membrane is stretched, MscL responds to the increase of membrane tension and opens a nonselective pore to about 30 Å wide, exhibiting a large unitary conductance of ∼3 nS. A fundamental step toward understanding the gating mechanism of MscL is to decipher the molecular details of the conformational changes accompanying channel opening. By applying fusion-protein strategy and controlling detergent composition, we have solved the structures of an archaeal MscL homolog from Methanosarcina acetivorans trapped in the closed and expanded intermediate states. The comparative analysis of these two new structures reveals significant conformational rearrangements in the different domains of MscL. The large changes observed in the tilt angles of the two transmembrane helices (TM1 and TM2) fit well with the helix-pivoting model derived from the earlier geometric analyses based on the previous structures. Meanwhile, the periplasmic loop region transforms from a folded structure, containing an ω-shaped loop and a short β-hairpin, to an extended and partly disordered conformation during channel expansion. Moreover, a significant rotating and sliding of the N-terminal helix (N-helix) is coupled to the tilting movements of TM1 and TM2. The dynamic relationships between the N-helix and TM1/TM2 suggest that the N-helix serves as a membrane-anchored stopper that limits the tilts of TM1 and TM2 in the gating process. These results provide direct mechanistic insights into the highly coordinated movement of the different domains of the MscL channel when it expands.

Mechanosensitive channels (MSCs) are a fundamental class of membrane proteins capable of detecting and responding to mechanical stimuli originating from external or internal environments. They are widespread in animals, plants, fungi, bacteria, and archaea, with crucial functions in adaptation and sensation (1, 2). MSCs may share a common principle enabling them to transduce mechanical forces into electrochemical signals (3), although the divergent evolution of mechanosensitive channels has led to highly diverse protein sequences and different overall architectures among them (4). In animals, the sensations of touch and hearing require the functions of MSCs (2). Malfunctions of MSCs are associated with diseases like cardiac arrhythmias, hypertension, neuronal and muscle degeneration, polycystic kidney disease, etc. (5). In plants, the MSCs protect plastids from hypo-osmotic stress of the cytoplasm (6). In bacteria, they fulfill functional roles as emergency valves and protect cells from acute hypotonic osmotic stress in the environments (7, 8). When challenged by acute osmotic downshock, Escherichia coli cells lacking large-conductance and small-conductance MSCs (MscL and MscS) will have their membrane ruptured, resulting in cell lysis (9).

As one of the two main classes of microbial mechanosensitive channels (MscL and MscS; the MscS family includes MscS, MscK, MscM, etc.), MscL has the largest conductance (at ∼3 nS) at the fully open state and gates at the highest pressure threshold near the lytic limit of the cell membrane (10). Since it was originally identified in 1994 (11), MscL has been well recognized as a model system for studying the molecular basis of mechanosensation through electrophysiology, biochemistry, genetics, structural biology, and molecular dynamic simulation approaches (12). Pioneering works demonstrated that MscL can be converted into a light-activated nanovalve useful for the triggered release of compounds in liposomes (13–15). Recent studies suggest that the open pore of MscL permits entry of streptomycin and could potentially serve as a target for antimicrobial agents (16, 17).

The gating process of MscL involves large conformational changes when it transits from the closed state to the open state through several intermediates (18). In the open state, MscL dilates its central pore to ∼30 Å wide and becomes permeable to water, ions, metabolites, and even small proteins (19–21). To describe the gating-related structural changes of MscL, an iris-like open-state model was proposed based on computational modeling (22) and disulfide cross-linking data (23). This model was verified and revised by further studies through electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy (24) and an electrostatic repulsion test (25). More recently, a study through the native ion mobility–mass spectrometry demonstrated that MscL has the inherent structural flexibility to achieve large global structural changes in the absence of a lipid bilayer (26).

For an accurate characterization of the gating-related structural dynamics of MscL, it is essential to solve and perform quantitative analyses on the structures of MscL trapped in various conformational states. Previously, crystal structures of Mycobacterium tuberculosis MscL (MtMscL) in the closed state (27) and Staphylococcus aureus MscL (SaMscL, Δ95–120 mutant) in the expanded intermediate state (28) were solved in homo-pentameric and homo-tetrameric forms, respectively. These two structures adopt funnel-shaped pores that are wide open at the periplasmic side and constricted at a narrow hydrophobic region near the cytoplasmic surface. The pore lumens are mainly lined by the first transmembrane helix (TM1) and flanked by the second transmembrane helix (TM2) at the peripheral region facing the lipid bilayer. Comparison of the two structures revealed a dramatic pivoting movement of the transmembrane helices during transition from the closed state to the expanded intermediate state (28). Nevertheless, the oligomeric state discrepancy and species difference between the closed (pentamer) and the expanded intermediate (tetramer) MscL structures raised questions that need to be further addressed (29, 30). It was reported previously that the tetrameric state of SaMscL may arise from the detergent-dependent behavior and the protein exists mainly in the pentameric form under in vivo conditions (29, 30). Thus, a curious and pressing question emerges about whether the expanded-state conformation observed in the tetrameric SaMscL also occurs in the pentameric form. More importantly, it is largely open about how different parts of MscL cooperate with each other to achieve concerted movements (within each subunit and between subunits) during its gating process. The principles governing the mechanical coupling of the gating elements (TM1 and TM2) and the accessory parts (N-terminal helix, periplasmic loop, and C-terminal helix) of MscL are yet to be established. To this end, we have successfully solved the structures of a MscL homolog from Methanosarcina acetivorans (MaMscL) in the closed and expanded states. Both structures are in homo-pentameric form and thus yield bona fide comparative studies showing the dramatic structural changes of MscL between the two distinct conformational states.

Results and Discussion

Fusion Approach for Enhancing the Crystallizability of MscL.

MscL has relatively small or minimal hydrophilic regions on the cytoplasmic and periplasmic surfaces. This feature is generally unfavorable for the formation of stable packing in the crystal lattice when the hydrophobic surfaces are covered by detergent micelles. As a stretch-activated channel, its inherent flexibility makes it highly sensitive to the changes of surrounding environments, either in the membrane or in detergent micelles. The conformational and oligomeric-state heterogeneities of a MscL sample purified in detergent solutions (29–31) further reduce the chance of obtaining well-ordered crystal samples suitable for structural studies. To overcome these problems and enhance the crystallizability of MscL, a pentameric soluble protein named riboflavin synthase (MjRS, from Methanocaldococcus jannaschii) was fused to the carboxyl terminus of a MscL homolog from M. acetivorans (MaMscL exists as pentamers on the membrane or in detergent solutions, Fig. S1A). The MaMscL–MjRS fusion protein purified in two different types of detergent solutions was crystallized in different space groups with distinct crystal packing modes as shown in Fig. S1 B–G.

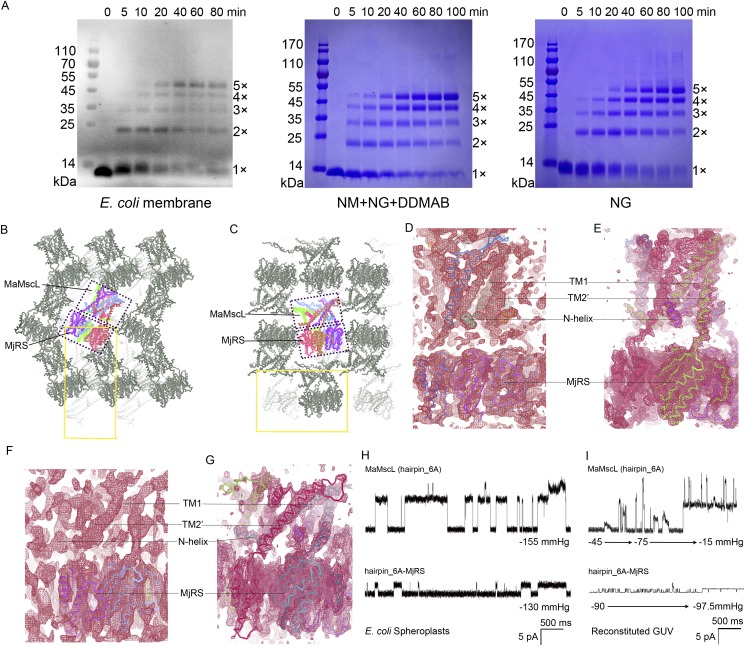

Fig. S1.

The oligomeric state of MaMscL and the effects of MjRS on the crystallization and single-channel behavior of MaMscL. (A) MaMscL forms stable pentamers on the E. coli membrane, in the NM+NG+DDMAB detergent mixture solution or in NG solution. The cross-linking of MaMscL on the membrane was carried out by incubating the homogenized membrane suspension with 2.5 mM N,N′-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCCD) and the cross-linked products in the membrane sample was probed with anti-histag antibody. For cross-linking the purified MaMscL protein (1 mg/mL) in detergent solutions, 3.3 mM glutaraldehyde was used and the products were stained with Coomassie Brilliant blue R250. (B and C) The role of MjRS in mediating the intermolecule packing within two different type of crystal lattices. The MaMscL-MjRS with MaMscL trapped in the closed-state conformation is packed in the P212121 lattice (B), whereas the other one with MaMscL trapped in the expanded state is packed in the P21212 lattice (C). In both cases, the MjRS serves as a scaffold protein providing large hydrophilic surfaces for stabilizing the intermolecule contacts in the crystals. The crystal contacts observed include the MjRS vs. MjRS′ interactions, MjRS vs. MaMscL′ interactions, and MaMscL vs. MaMscL′ interactions (the ′ symbol denotes the parts from neighboring molecules). (D) The 2Fo-Fc map of Form 1 crystal calculated with the phases from the initial molecular-replacement model (MtMscL plus MjRS). (E) The improved 2Fo-Fc map of Form 1 crystal calculated with the refined model of MaMscL-MjRS at the closed state. The structural models are shown as colored Cα traces. (F) The electron density map of Form 2 crystal calculated with the initial molecular-replacement model phases (MjRS only). Even though the phases are calculated without the models of MaMscL, the electron densities for TM1, TM2, and the N-helix are clearly visible. (G) The density map of Form 2 crystal calculated with the refined model of MaMscL-MjRS at the expanded state. All four maps are sigmaA-weighted 2Fo-Fc maps contoured at the 1.0 × σ level. (H and I) The effect of MjRS on the single-channel behavior of MaMscL recorded on E. coli spheroplasts (H) or reconstituted GUV membranes (I). MaMscL hairpin_6A mutant was used for this analysis due to its relatively more stable open state (longer open dwell time) than that of the wild-type protein. All data were recorded with excised inside-out patches held at +20 mV and negative pressure was applied at the indicated value through a stepwise or linear protocol. For the GUV samples, MaMscL hairpin_6A was reconstituted in the DPhPC+POPG+cholesterol (8:1:1/wt:wt:wt) liposomes through the electroformation method, whereas the hairpin_6A-MjRS fusion protein was reconstituted in the azolectin+cholesterol (95:5/wt:wt) liposomes through the modified sucrose method.

Do the MaMscL-MjRS fusion proteins form functional channels as the one without fusion protein attached? First, the two structures of MaMscL-MjRS solved in different space groups demonstrate that the MaMscL portions do form correctly assembled channel architectures and retain the flexibility to adopt two drastically different conformations (Fig. 1A). The C-terminal region of MaMscL and the N-terminal part of MjRS serve as a flexible linker ready to stretch when MaMscL changes its conformation. Second, it was previously shown that the introduction of polar residues to the pore constriction area of EcMscL, such as G26H mutation, confers a severe gain-of-function (GOF) phenotype to the cells expressing the leaky mutant channel (32). The Gly26 residue is conserved in MaMscL and the G26H mutant of the nonfusion MaMscL does exhibit a GOF effect, although slightly milder than that of EcMscL-G26H (Fig. 1B). Similarly, the G26H mutation on the MaMscL-MjRS fusion protein poses a GOF phenotype resembling that of the nonfusion MaMscL. Thereby, it is confirmed that the MaMscL-MjRS does form a functional channel on the cell membrane as the nonfusion MaMscL. Fusion of MjRS to the C-terminal end of MaMscL does not interfere with the assembling of MaMscL into a functional channel on the membrane. Third, the wild-type MaMscL is active, but not as good as EcMscL in rescuing the MJF465 cells during the osmotic downshock (Fig. 1C). Its single-channel conductance (0.2–0.3 nS) is significantly smaller than that of EcMscL (∼3 nS) (Fig. 1 D and E). Fusion of MjRS to MaMscL further reduces its conductance to 0.10–0.15 nS (Fig. S1 H and I). As a result, the MaMscL-MjRS fusion protein displayed a loss-of-function phenotype during osmotic downshock (9) (Fig. 1C). Therefore, the MjRS protein either serves as a flow restrictor below the open channel or prevents the channel from achieving a fully open state during the osmotic downshock. The fusion of homo-pentameric MjRS with MaMscL not only provides a large hydrophilic scaffold to mediate intermolecule contacts in the crystal lattice, but also contributes to the stabilization of the MaMscL channel in two discrete conformational states.

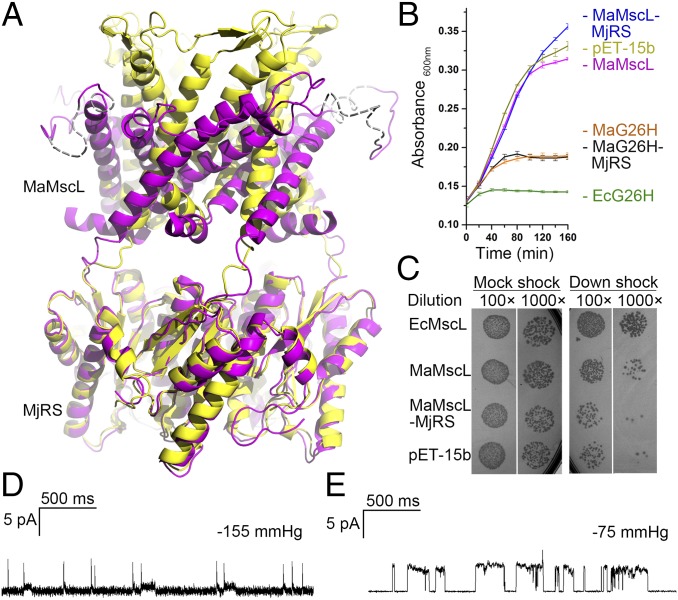

Fig. 1.

Fusion of MaMscL with MjRS. (A) Alignment of the two MaMscL-MjRS structures with their MjRS parts superposed. The yellow structure shows the one with MaMscL trapped in the closed state, whereas the magenta one contains MaMscL in the expanded conformation. The dashed lines in the magenta structure indicate the flexible periplasmic loop regions of MaMscL without distinguishable electron densities. (B) Cell growth assays showing the gain-of-function effect of G26H mutation on MaMscL-MjRS or MaMscL. The wild-type MaMscL/MaMscL-MjRS, empty vector pET15b, and the G26H mutant of EcMscL are included as controls. The error bar indicates the SD of the mean value (n = 3). (C) Osmotic downshock experiments showing the activities of MaMscL and MaMscL-MjRS fusion protein compared with EcMscL. The emptor vector pET-15b is included as the negative control and those expressing EcMscL are the positive controls for comparison. (D and E) Single-channel activities of the wild-type MaMscL on the membrane of E. coli spheroplast (D) or on the azolectin giant unilamellar vesicle membrane (E). Both data were recorded with excised inside-out patches held at +20 mV and the negative pressure applied is indicated above the traces.

Structures of MaMscL Trapped in the Closed and Expanded States.

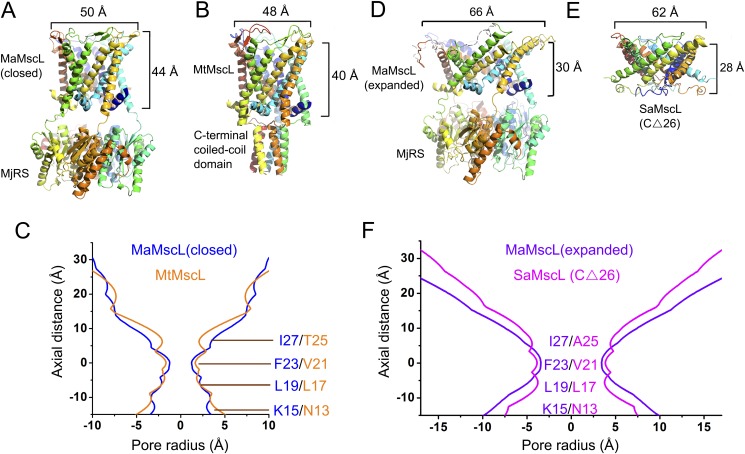

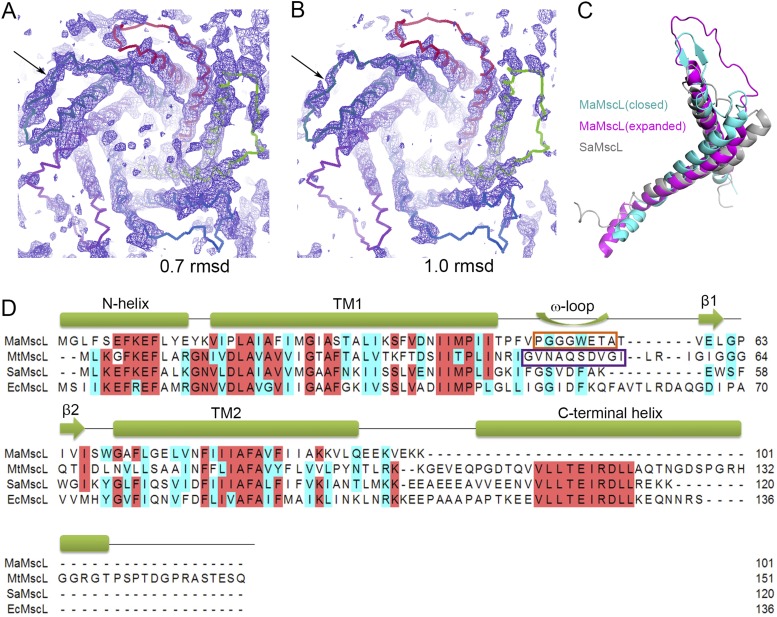

Within the two crystal forms, the structures of MaMscL portions are dramatically different from each other, whereas the MjRS parts of the fusion proteins are nearly identical in their overall structures (Fig. 1A). The MaMscL structure solved in Form 1 crystal aligns well with the closed-state MtMscL structure (Fig. S2 A–C), whereas the other structure solved in Form 2 crystal resembles the expanded intermediate-state structure of SaMscL-CΔ26 (Fig. S2 D–F). The values for the pore radii around the constriction sites, the tilt angles of TM1 and TM2, and the crossing angles of TM1–TM1′ (TM1 from the adjacent subunit) helices or TM2–TM2′ helices have been extracted from the two pairs of MscL structures and summarized in Table S1 for a quantitative comparison. These data clearly demonstrate that MaMscL in Form 1 crystal is in the closed-state conformation as the MtMscL structure, and the other one in Form 2 crystal is in the expanded conformation as the SaMscL-CΔ26 structure.

Fig. S2.

Comparing the two structures of MaMscL with those of MtMscL and SaMscL(CΔ26). (A) Structure of the MaMscL-MjRS with its MaMscL stabilized in the closed state. (B) The structure of MtMscL (PDB ID code 2OAR) representing its closed-state conformation. (C) The pore profile of the closed-state MaMscL superposed on that of MtMscL. (D) Structure of the MaMscL-MjRS with its MaMscL being expanded horizontally and compressed vertically. (E) The expanded intermediate-state structure of SaMscL with 26 residues deleted from the C terminus (PDB ID code 3HZQ). (F) The pore profiles of the expanded-state MaMscL superposed on that of SaMscL(CΔ26). The data used to draw the pore profiles of MaMscL (closed), MaMscL (expanded), MtMscL, and SaMscL(CΔ26) are all extracted from the crystal structures through the HOLE program. The zero points on the vertical axis are set at the hydrophobic constriction sites (F23/V21) of the MscL pores.

Table S1.

Geometric parameters extracted from the structures of MaMscL, MtMscL, and SaMscL

| TM1 | TM2 | ||||

| MscL structures | Pore radius, Å | Tilt angle*, ° | Crossing angle†, ° (TM1–TM1′) | Tilt angle*, ° | Crossing angle†, ° (TM2–TM2′) |

| MaMscL (closed) | 1.2 | 37 | −41 | 24 | −28 |

| MtMscL | 1.7 | 37 | −41 | 32 | −36 |

| MaMscL (expanded) | 3.8 | 58 | −60 | 42 | −46 |

| SaMscL(ΔC26) | 3.9 | 47 | −63 | 62 | −77 |

The tilt angles of TM1 and TM2 are defined as the angle between the helical axis and the pore axis.

The crossing angle is between two adjacent TM1 (or TM2) helices.

The closed-state MaMscL structure has a very narrow hydrophobic constriction site with a pore radius at 1.2 Å (Fig. S2C), a small TM1 (or TM2) tilt angle of 37° (or 24°), and a small TM1–TM1′ (or TM2–TM2′) crossing angle of −41° (or −28°). Despite overall similarities, differences between the closed-state MaMscL and MtMscL structures are also present. The pore-constricting residue in MaMscL is Phe23, whereas the MtMscL channel is constricted at Val21 (Fig. S2C). The tilt angle of TM2 and the TM2–TM2′ crossing angle of MaMscL are both 8° smaller than those of MtMscL, whereas the TM1 tilt angles and TM1–TM1′ crossing angles are identical between the two structures. Moreover, MaMscL naturally lacks the small cytoplasmic domain that forms a coiled-coil helical bundle structure in MtMscL (27) or EcMscL (33).

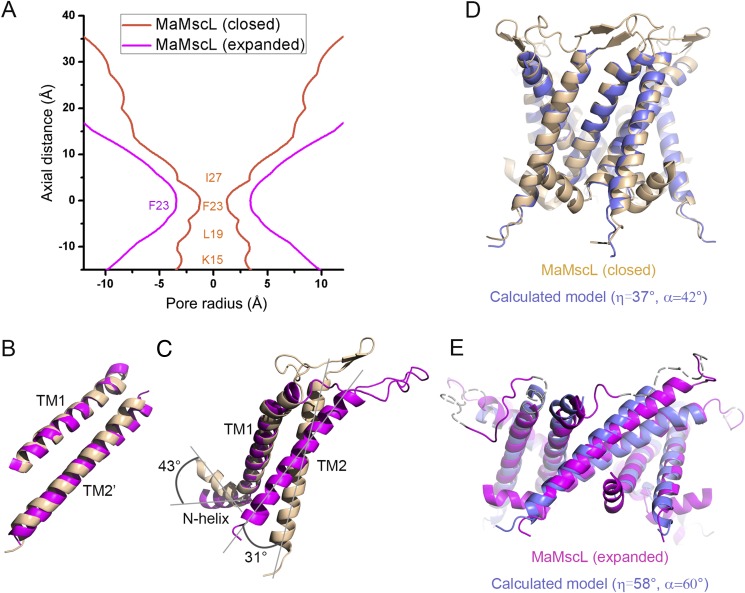

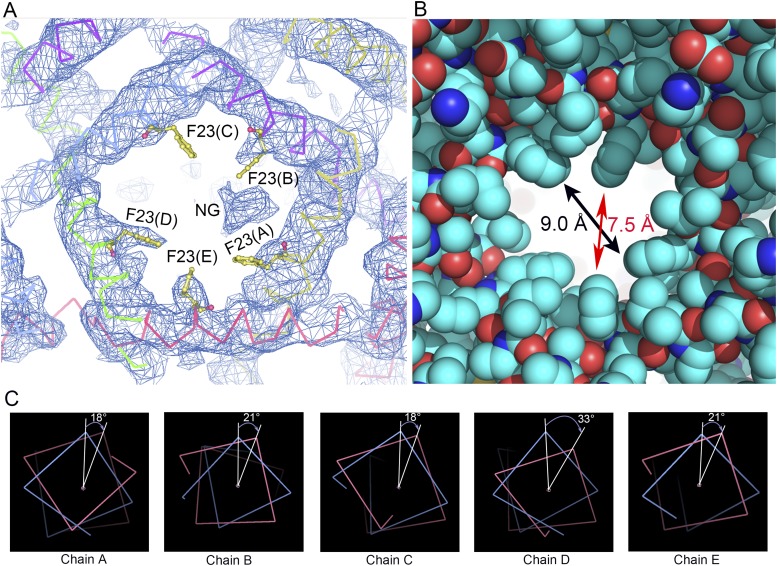

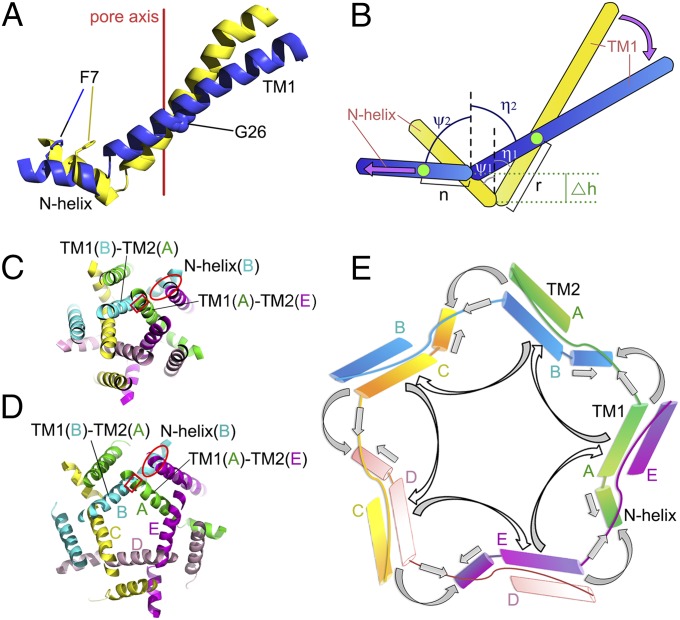

When the MaMscL switches from the closed state to the expanded state, massive structural rearrangements occur in the transmembrane region, the N-terminal helix (N-helix), and the periplasmic loop region (Fig. 2A). Meanwhile, the width of its periplasmic surface increases from 50 Å to 66 Å, leading to a dramatic expansion of the surface area (ΔA) by ∼1,457 Å2. This ΔA value is close to the in-plane protein area change of the first expanded substate (but smaller than that of the open state) derived from the energy-area profiles of E. coli MscL (34). The hydrophobic constriction site of MaMscL (located around Phe-23) increases its width from 2.4 Å (closed) to 7.5–9.0 Å (expanded) (Figs. S3A and S4 A and B). Accompanying the expansion within the membrane plane, the thickness of the channel decreases from 44 Å to 30 Å. Compared with the closed-state structures, the expanded-state MaMscL structure has more tilted TM1 and TM2 helices (with 58° and 42° tilt angles, respectively) and larger TM1–TM1′ (or TM2–TM2′) crossing angles at −60° (or −46°) (Table S1).

Fig. 2.

Dramatic rearrangement of the MaMscL structures between the closed state and the expanded state. (A) Alignment of the two MaMscL structures with their central pore axes superposed. The vertical positions of the two structures are aligned around Gly26. (B and C) The interactions between TM1 and TM1′–TM2′ from the adjacent subunit at the closed (B) and expanded states (C). The α-helices are shown as cylinders and the amino acid residues involved in the intersubunit contacts are presented as spheres. (D) Rotation of TM1′ against the TM1–TM2′ pair during the transition from the closed state (yellow) to the expanded state (blue). The pivot point for the rotation of TM1′ is located around Gly26.

Fig. S3.

Analyzing the structures of MaMscL in the closed and expanded states. (A) Superposition of the pore profiles of the two MaMscL structures. The width of the pore at the hydrophobic constriction (Phe23) is 2.4 Å (closed) or 7.5 Å (expanded), respectively. (B) The relative position of TM1 and TM2′ (TM2 from the adjacent subunit) is essentially unchanged within the two structures. (C) Alignment of the two MaMscL monomers on their TM1 helices. The N-helix and TM2 are rotated dramatically in respect to TM1 during the transition between the two conformational states. The degrees of their rotations are measured and labeled. (D and E) The experimental closed-state and expanded-state structures of MaMscL aligned to the theoretical models of closed-state and expanded-state structures, respectively. For the information about generating the calculated closed-state and expanded-state structural models of MaMscL, see Materials and Methods. Color codes: golden, closed-state structure; blue, theoretical models at the closed and expanded states; purple, expanded-state structure.

Fig. S4.

The pore constriction area of MaMscL in the expanded-state structure and the corkscrew-type rotation of TM1. (A) The 2Fo-Fc density map around the pore constriction (+1.0 × σ contour level). The view is along the pore axis from the periplasmic side. Whereas the side chains of Phe23 residues from subunits D and E exhibited relatively strong electron densities, the one from monomer C is fairly weak. Its side chain is tentatively modeled with rotamer 2, whereas it could also adopt rotamers 1 and 4 with its side chain pointing downward toward the cytoplasmic side (note that the Phe residue can adopt only four different rotamers and rotamer 3 of Phe23 is unlikely as it will clash into the backbone of TM1). The electron density feature between Phe23(A) and Phe23(B) is likely attributed to the head group of a detergent molecule (NG). (B) The van der Waals sphere model showing the width of the pore constriction region. (C) The slight corkscrew-type rotation of TM1 around its own axis. Blue, the theoretical expanded-state model without corkscrew-type rotation (as a reference); magenta, the expanded-state structure of MaMscL with slight (18°–33°) clockwise rotation of TM1 relative to the reference theoretical model. The view is from the periplasmic side along the helical axis.

Rearrangement of the Transmembrane Helices.

The thinning of the transmembrane domain of MaMscL is a consequence of large-degree pivoting of the TM1–TM2′ helix pair toward the membrane plane when the channel changes conformation from the closed state to the expanded state (Fig. 2A). The intersubunit TM1–TM2′ helix pair moves as a rigid body during the transition (Fig. S3B), consistent with the previous observation based on the comparison of MtMscL and SaMscL-CΔ26 structures (28). Accompanying the pivoting movement of TM1–TM2′ in MaMscL, its TM2 rotates by 31° relative to the TM1 within the same subunit (Fig. S3C). Meanwhile, TM1′ slides along the surface of the TM1–TM2′ helix pair and the A22′–A20 contact point between TM1′ and TM1 shifts to the S29′–A20 site. The contact between TM1′ and TM2′ alters from V37′–N77′ to V37′–I80′ (Fig. 2 B and C). When the TM1–TM2′–TM1′ triplets from the two MaMscL structures are superposed, it is evident that TM1′ undergoes a slight clockwise rotation around Gly26 by 18° with respect to the TM1–TM2′ pair (Fig. 2D).

According to Spencer and Rees (35), the helix-pivoting movement in a symmetrical homo-oligomeric channel follows the geometric relationship described by the following two equations, namely cosα = cos2η + sin2ηcosθ and R = d(tanηcot(α/2) − 1)/2. In these equations, α is the interhelical-crossing angles, η is the tilt angle of the TM1 helix with respect to the pore axis, θ = 72° for a pentameric channel, R is the minimum pore radius, and d is the diameter of a transmembrane helix. To verify this theory, we have generated a series of calculated models of MaMscL according to the above equations. The input model is a single pair of TM1–TM2′ helices extracted from the closed-state structure of MaMscL and realigned with their helical axes parallel to the pore axis. When the helix tilt angle η reaches 37° and 58°, the calculated structures match well with the experimental closed-state and expanded-state structures of MaMscL structures (Fig. S3 D and E). Thus, these two conformational states of MaMscL fit reasonably well in the rearrangement trajectory predicted by the Spencer–Rees equation. The transition of MaMscL from the closed state to the expanded state occurs through a coordinated helix-pivoting rearrangement in the transmembrane domain (Movie S1). It is also noteworthy that there might be slight (18°–33°) corkscrew-type rotation of TM1 accompanying the helix-pivoting movement (Fig. S4C). Such rotation was predicted to occur in larger degrees for the open state of EcMscL (24, 25, 32, 36).

Conformational Changes in the Periplasmic Loop Region.

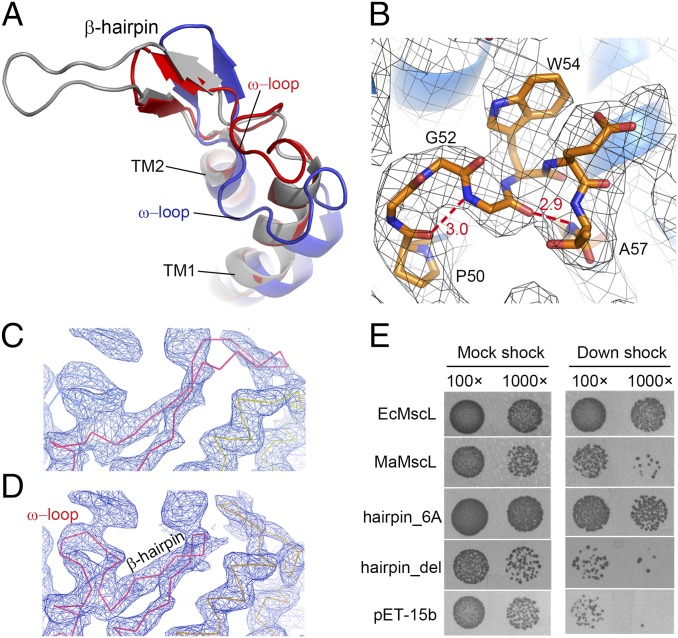

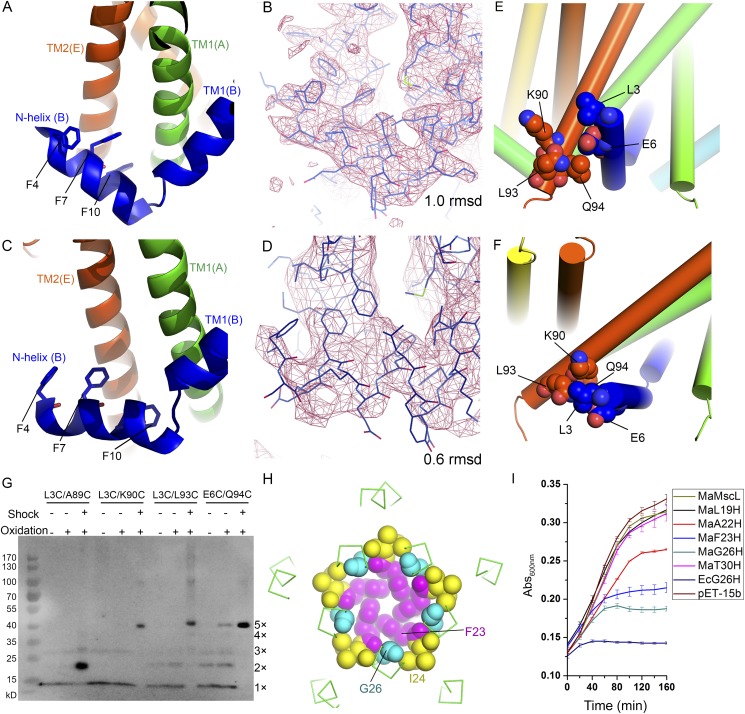

The periplasmic loop of MscL influences its gating kinetics and mechanosensitivity (37–39), but the structural basis underlying its regulatory function is not well understood. On the periplasmic side of MaMscL, the loop between TM1 and TM2 contains a folded region with an “ω”-shaped structure (ω-loop) between residues Pro50–Ala57 (PGGGWETA) and a short β-hairpin structure following the ω-loop (Fig. 3 A and B). For MtMscL, a careful reinspection of its electron density map has led to an improved structural model for its periplasmic loop region (Fig. 3 C and D). The result shows that similar ω-loop (residues Gly47–Ile56, GVNAQSDVGI) and β-hairpin structures also exist in the corresponding region of MtMscL.

Fig. 3.

Structure and function of the periplasmic loop region of MaMscL. (A) The ω-loop and β-hairpin structures in the periplasmic loops of MaMscL(blue) and MtMscL (red, with a rebuilt loop structure). The original structure of the MtMscL loop before being rebuilt (PDB ID code 2OAR) is shown in silver. (B) The local structure of the ω-loop of MaMscL with the hydrogen bonds indicated by the dashed lines. The unit for the numbers labeled around the dashed lines is angstroms. The 2Fo−Fc map (gray meshes) is contoured at 1.0 × σ. (C and D) Representations of the Cα traces of the original MtMscL structure (C) and the rebuilt MtMscL structure (D) superposed on the 2Fo-Fc electron density map (contoured at 1.8 × σ). (E) The phenotypes of MaMscL mutants with altered ω-loop sequences are demonstrated through the osmotic downshock experiments. The “hairpin_del” and “hairpin_6A” represent the MaMscL constructs with the ω-loop region (PGGGWETA) deleted or replaced by six alanine residues (GGGWET/6A). EcMscL, MaMscL, and empty vector (pET15b) are included as controls.

The structurally conserved ω-loop and β-hairpin motifs serve to fold the long polypeptide chain of the loop at the resting closed state. They also provide the flexibility for the loop to stretch out like a spring when the channel opens in response to mechanical force. The ω-loop of MaMscL in the closed state inserts into the pore lumen, with Trp54 forming van der Waals contacts and hydrogen bonds with amino acid residues from the C-terminal end of TM1. Meanwhile, the β-hairpin is associated with the C-terminal end of TM1 and the ω-loop from an adjacent subunit. The loop–TM1/TM1′ interactions and the hydrogen bonds formed within the ω-loop and the β-hairpin motifs collectively contribute to the stabilization of the channel at the resting closed state. Deletion of six residues (Gly51–Thr56) from the ω-loop region abolishes the channel’s function during osmotic downshock (Fig. 3E). On the other hand, when this segment (Gly51–Thr56) of the ω-loop is replaced by poly-Ala of the same length, the survivability of cells hosting this construct after osmotic downshock increases to a level close to those expressing E. coli MscL (the positive control, Fig. 3E). Compared with the wild-type MaMscL, the hairpin_6A mutant exhibits a slightly larger conductance (0.43–0.46 nS vs. 0.2–0.3 nS) (Fig. S1 H and I) and gates at a lower pressure threshold (pL/pS ratio ∼ 0.9 vs. 1.6). Thus, the ω-loop motif is involved in regulating the sensitivity of MscL to osmotic downshock.

Previously, the Q56P and K55T mutants (with mutations in the ω-loop region) of EcMscL were shown to gate at pressure thresholds lower than that of the wild-type channel (37, 40). These mutations may disrupt the hydrogen bonds within the ω-loop or affect the loop–TM1 interactions. The Q65R and Q65L mutations on the β-hairpin region of EcMscL lead to partial gain-of-function and loss-of-function phenotypes, respectively (39). Proteolytic cleavage on the periplasmic loop region increases the channel’s sensitivity to membrane tension (38), further underscoring the pivotal role of this region in modulating the mechanosensitivity of MscL. Curiously, the sequence and length of the periplasmic loop appear to be variable among different species (Fig. S5D). These considerations suggest that this region may be the result of divergent evolution entitling MscL channels from different species with the flexibility to adjust their mechanosensitivity to adapt to different living environments.

Fig. S5.

The extended conformation of the periplasmic loop region in the expanded-state MaMscL structure. (A and B) The weak but visible electron densities in the periplasmic loop regions of the expanded-state MaMscL. The blue subunit indicated by the arrow has relatively stronger and more visible densities compared with the other four subunits. The same map is contoured at 0.7 × σ (A) or 1.0 × σ (B) levels for comparison. (C) Comparison of the periplasmic loop regions from the closed-state and expanded-state MaMscL structures and the SaMscL structure. The model for the loop of the expanded-state MaMscL represents the subunit with the strongest electron density for the loop region. (D) Alignment of the amino acid sequences of MaMscL, MtMscL, SaMscL, and EcMscL. The orange and purple boxes show the ω-loop regions of MaMscL and MtMscL.

In the expanded state, the periplasmic loop from one of the five subunits of the MaMscL channel exhibits continuous electron density with an extended conformation, whereas those in the other four subunits are mostly disordered. This observation indicates the loops are fairly flexible in the expanded state (Fig. S5 A and B). The loop extension also occurs in the expanded intermediate-state structure of SaMscL (Fig. S5C). Therefore, the transition from the closed state to the expanded state not only involves pivoting movement of the transmembrane helices, but also is accompanied by stretching of the periplasmic loop when the distance between the periplasmic ends of TM1 and TM2 helices increases.

Mechanical Coupling Between the N-helix and TMs.

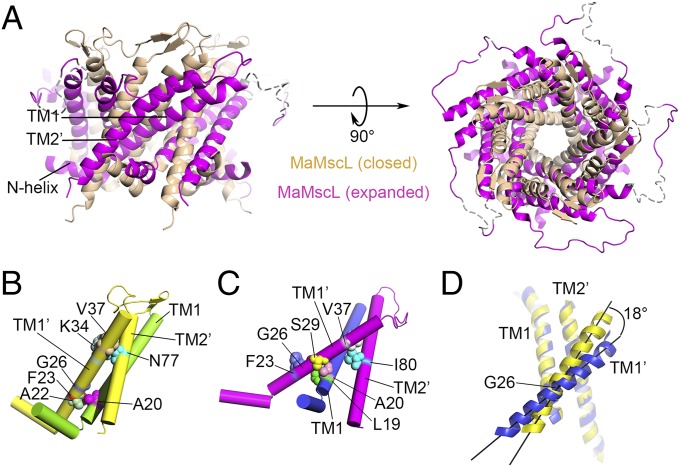

The N-helix is essential for the function of MscL as indicated by the previous studies showing that EcMscL with the N-terminal region deleted (Δ2–12) is nonfunctional (37, 41). Initially, it was proposed that this region forms a small helical bundle serving as a second gate underneath the pore (22, 23). Later, guided by an improved structural model of MtMscL (42), the functional characterizations of this region through cysteine scanning mutagenesis suggested that its function is likely a membrane anchor instead of a second gate (43). As shown in Fig. 4 A and B, repositioning of the N-helix with respect to the TM1 helix (and to the membrane plane) is observed when the two MaMscL structures are compared. In the closed state, the N-helix assumes a tilted position, forming a 34° angle with the membrane plane (or 56° with the membrane normal). It becomes nearly horizontal to the membrane surface in the expanded state. During the transition, the N-helix pivots toward the membrane plane in a direction opposite to that of TM1 (Fig. 4B). The pivot point is located at the joint (residue Lys15) between the N-helix and TM1. The crossing angle between the N-helix and TM1 increases from 90° to 137° during the transition from the closed state to the expanded state. Meanwhile, the angle between the N-helix and the membrane plane decreases from 34° to 8°.

Fig. 4.

Mechanical coupling among the N-helix, TM1, and TM2 during the transition from the closed state to the expanded state. (A) The rotation and horizontal sliding of the N-helix are coupled to the tilting of TM1. The closed-state and expanded-state structures are shown in yellow and blue, respectively. The view is along the membrane plane. (B) A schematic diagram showing the relationship between the N-helix and TM1. The green spot on TM1 is the pivot point around which it tilts. The other green spot on the N-helix is its membrane-anchoring point that allows it to slide along the membrane plane. The tilt angles of N-helix and TM1 with respect to the pore axis are ψ1 and η1 in the closed state (yellow) or ψ2 and η2 in the expanded state (blue). The vertical translation of the N-helix-TM1 joint is defined as Δh. The lengths from the joint to the pivot/anchor points on TM1 or N-helix are defined as r or n, respectively. (C and D) The sectional views of the closed-state (C) and expanded-state (D) structures of MaMscL near the pore constriction area. The intersubunit coupling area between the N-helix(B) and TM1(A)–TM2(E) pair is indicated by the red ellipses. A local view of this area is shown in Fig. S6 A–D. The red rectangles cover the coupling points between the two adjacent TM1 helices. (E) A cartoon diagram describing the mechanical bases for the coordinated movements of the various parts of a MaMscL pentamer. The block arrows indicate the estimated directions of force transmission when the TM1–TM2′ pairs tilt toward the membrane plane. The N-helix, TM1, and TM2 are shown as cylinders. The solid lines connecting the cylinders are the loop regions between two α-helices.

How is the movement of the N-helix coupled to those of the TM1 and TM2 helices during the gating transition? As shown in Fig. 4 C–E and Movie S1, when the TM1(A)–TM2(E) helix pair tilts toward the membrane plane, TM1(A) pushes on the TM1(B)–TM2(A) pair and TM1(B) pushes on the next pair TM1(C)–TM2(B) and so on, as in a domino effect (Fig. 4E). Furthermore, the TM1(A)–TM2(E) pair directly contacts the N-helix(B) (Fig. 4 C and D), primarily through van der Waals interactions between them. The bulky side chains of the Phe4 and Phe7 residues from the N-helix(B) form van der Waals interactions with TM2 of subunit E, whereas Phe10 intercalates into the space between the TM1(A)–TM2(E) pair and interacts with both of them (Fig. S6 A–D). The repositioning of the TM1(A)–TM2(E) pair drives the N-helix(B) toward the membrane plane. At the same time, the N-helix(B) is propelled by TM1(B) outwardly away from the pore center in the horizontal direction. Consequently, the C-terminal end of TM2(E) approaches the N-terminal Leu3 and Glu94 on the N-helix(B) at the expanded state, and their interactions can be validated by the disulfide-trapping experiments (44) under osmotic shock conditions (Fig. S6 E–G). Thereby, the movement of the N-helix is coupled to the tilting motions of the two transmembrane helices. Such a mechanism is reminiscent of the opening of an umbrella whereas the TM2 behaves like an umbrella stretcher and the N-helix resembles the rib that is pushed to open by the stretcher (Movie S1).

Fig. S6.

The regions around the anchor point on the N-helix and the pivot point on TM1. (A and B) The local structures of the N-helix–TM2′ interface (A) and the 2Fo-Fc electron density map (B) in this region from the closed-state structure of MaMscL. (C and D) The structure (C) and electron density map (D) of the same region in the expanded-state structure of MaMscL. (E and F) Close interactions between the N-helix and the C-terminal end of TM2 in the closed-state (E) and expanded-state (F) MaMscL structures. Leu3 in the expanded-state structure (not observed due to insufficient resolution and high flexibility) is at an estimated position based on a superposed model of the N-helix from the closed-state structure. (G) The disulfide-trapping analyses of four pairs of double cysteine mutants of MaMscL during osmotic downshock assay. These double cysteine mutants are chosen according to the sequence alignment between MaMscL and EcMscL. Previously, I3C/I96C, I3C/K97C, I3C/N100C, and E6C/K101C mutants of EcMscL were cross-linked into pentamers through treatment with Cu-phenanthroline (oxidizing reagent) during osmotic downshock and were trapped in a subconducting intermediate state under oxidizing conditions. The four double cysteine mutants shown in this gel correspond to those of EcMscL and were used to test the interactions between the N-terminal region and the C-terminal end of TM2 under mock-shock and downshock conditions. The results indicate that Leu3 and Glu6 residues at the N-terminal region of MaMscL likely have close interactions with the C-terminal end of TM2 under the expanded or open states but not much interaction at the resting closed state. (H) The crucial structural role of Gly26 as the pivot point of TM1 against the adjacent TM1. The Gly26 residues are sandwiched by the nearby Phe23 and Ile24 residues. The transmembrane helices TM1 and TM2 are simplified as green ribbons, and the Gly26, Phe23, and Ile24 residues are shown as sphere models in cyan, magenta, and yellow, respectively. (I) The cell growth phenotypes of the gain-of-function MaMscL mutants. The histidine mutations are introduced to the amino acid residues on TM1 (L19, A22, F23, G26, and T30) distributed along the surface of the pore lumen. Among the mutants tested, the G26H mutant yields a GOF phenotype resembling that of the F23H mutant (the one at the pore constriction site). The error bar denotes the SD of the mean value from three repeats.

At the other end of the gating transition, we ask whether the tilting of transmembrane helices will ever reach a limit during channel opening; i.e., What limits the tilt of the TM helices during the gating process? We have addressed these questions by modeling the geometric relationship between the N-helix and TM1 (Fig. 4B) and found that the tilt angle of the N-helix (ψ) is related to the tilt angle of TM1 (η) through the following equation: r(cosη1 − cosη2) = Δh = n(cosψ1 − cosψ2), where r and n are the lengths between the joint point and the pivot/anchor points on the TM1 and N-helix, respectively. Δh is the vertical translation of the joint point during the conformational change. In the closed state, η1 = 37° and ψ1 = −56°, whereas the expanded-state structure has η2 = 58° and ψ2 = −82°. Thereby, r/n = [cos(−56°) − cos(−82°)]/(cos37° − cos58°) = 1.56. The r/n parameter should be constant during the transition when the pivot point of TM1 is stable and the anchor point on the N-helix remains within the membrane plane under different conformational states. This is indeed verified by observations based on the closed- and expanded-state MaMscL structures (Fig. 4A). The pivot point of TM1 is located near Gly26, which contacts residues Phe23 and Ile24 from the adjacent TM1 (Fig. S6H), such that its position in the two conformational states remains nearly constant (relative to the adjacent TM1, Fig. 2D). Mutation of Gly26 to histidine leads to a severe gain-of-function phenotype (Fig. S6I), presumably by weakening the TM1–TM1′ association and affecting the stability of the nearby pore constriction. The Cα–Cα distance between Gly26 and Lys15 (joint point) is 18.1 Å, yielding a measured value for the r parameter. To search for the membrane-anchoring point, the distances between the Cα atoms of Lys15 and the residues on the N-helix were measured. Of these, Phe7 is located 11.5 Å from Lys-15 and the distance matches well with the calculated n parameter of 11.6 Å, when r = 18.1 Å and r/n = 1.56. This result consequently indicates that Phe7 on the N-helix most likely serves as the membrane-anchoring point during the gating transition. It is highly conserved among different MscL homologs (Fig. S5D) (43). Such an anchor point is not completely fixed but can slide horizontally along the membrane plane during the gating transition (Fig. 4B). In this scenario, ψ is related to η through the following equation:

In the fully expanded state, the N-helix can achieve a maximal tilt angle (ψ) at −90° only when it is coplanar with the membrane surface. Beyond this point, the amphipathic N-helix would protrude out of the membrane, leading to an energetically unfavorable status due to exposure of hydrophobic residues to the aqueous environment. When confined at the horizontal position by the membrane surface, the N-helix serves as a door stop, preventing TM1–TM2′ from tilting further. In this case, the mutual relationship between the N-helix and TM1 predicts the limit for the tilt angle of TM1 (η) at a maximum value of ∼64° when ψ = −90°. In the expanded MaMscL structure, the η angle of TM1 is at 58°, indicating this state is approaching the limit for helix-tilting movement. The full opening of the pore might consequently require a second step corresponding to the outward swinging of the TM1–TM2′ helix pair away from the pore axis in an iris-like opening motion (28), instead of by further tilting of the TM1–TM2 pair toward the membrane plane.

In summary, MscL gates like a nanoscale mechanical valve that exhibits highly coupled and well-coordinated movements of each individual part as shown in Movie S1 and Fig. 4E. The two new structures of MaMscL now provide direct evidence delineating the mechanism of physical coupling among its multiple structural elements during channel expansion.

Materials and Methods

The structure refinement statistics are presented in Table S2. The coordinates and diffraction data have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under accession codes 4Y7K (closed-state MaMscL) and 4Y7J (expanded-state MaMscL).

Table S2.

Data collection and structure refinement statistics of MaMscL-MjRS structures

| Crystal sample | MaMscL(closed)-MjRS (Form 1) | MaMscL(expanded)-MjRS (Form 2) |

| Data collection | ||

| Wavelength, Å | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Beamline* | BL-17U/SSRF | BL-17A/PF |

| Space group | P212121 | P21212 |

| Resolution, Å | 50–3.5 | 41–4.1 |

| Cell dimensions, Å° | a = 87.29 | a = 147.36 |

| b = 140.37 | b = 149.25 | |

| c = 182.54 | c = 99.17 | |

| No. observed reflections | 1,357,559 | 159,137 |

| No. unique reflections | 27,942 | 17,722 |

| Rmerge, % | 7.7 (>100) | 10.9 (93.8) |

| Rpim, % | 2.6 (39.3) | 4.0 (33.3) |

| I/σ | 26.2 (1.8) | 8.7 (2.3) |

| Completeness, % | 99.2 (100.0) | 99.7 (100.0) |

| Redundancy | 11.0 (11.2) | 9.0 (9.0) |

| Structure refinement | ||

| Resolution, Å | 42–3.5 | 41–4.1 |

| Rwork, % | 25.95 | 32.07 |

| Rfree, % | 28.71 | 37.58 |

| FOM | 0.68 | 0.66 |

| rmsd bond, Å | 0.012 | 0.013 |

| rmsd angle, ° | 1.568 | 2.116 |

| Ramachandran plot, preferred/additional allowed/generously allowed/outliers, % | 91.7/7.7/0.4/0.2 | 72.2/24.1/1.9/1.8 |

| All atoms (mean B factor, Å2) | 9,223 (171.0) | 8,938 (254.7) |

FOM, figure of merit.

Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF) and the Photon Factory (PF) at Tsukuba, Japan.

For details on the methods of protein purification, crystallization, data collection and processing, structure determination, and functional assays, please refer to SI Materials and Methods.

SI Materials and Methods

Plasmids and Cloning.

The genes encoding Methanosarcina acetivorans MscL and Methanocaldococcus jannaschii riboflavin synthase (PDB ID code 2B98) were synthesized with their codons optimized for protein expression in Escherichia coli. The two genes were amplified separately and ligated together by overlap extension PCR. The first version of the MaMscL-MjRS fusion gene (used for solving the expanded-state structure in Form 2 crystal) was obtained by fusing the first methionine residue of MjRS directly to the C terminus of MaMscL with zero linker between them. For the optimization of closed-state MaMscL structure in Form 1 crystal, the last lysine residue (K101) in MaMscL and the first methionine residue of MjRS were deleted to shorten the linkage between them. The fusion genes were ligated between the NdeI and BamHI sites of pET15b vector. For site-directed mutagenesis, the Quikchange protocol was applied.

Protein Expression and Purification.

For large-scale expression of the the MaMscL-MjRS fusion proteins in the C41(DE3) strain of E. coli cells (45), a 50-mL overnight culture grown in LB-Amp media was transferred into 2 L Terrific-Broth (TB) media with 0.1 mg/mL Amp. When the OD600nm reached ∼0.8, 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactoside (IPTG) was added to the culture to induce protein expression. Three hours later, the cells were harvested by centrifugation at 6,000 × g and stored as wet pellets at −80 °C.

The protein sample used for growing Form 1 crystals was prepared as follows. The cells were suspended in the lysis buffer [50 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 8.0, 200 mM NaCl, 1.5% (vol/vol) Triton X-100] at a ratio of 1 g cells per 10 mL buffer. The suspension was gently stirred for 40 min at 4 °C and then sonicated with a flat tip on a Misonix S-4000 sonicator for 2 min (total process time) at an amplitude of 80. After centrifugation at 18,000 rpm in JA25.5 rotor (Beckman) for 30 min, the supernatant was collected and applied onto the Ni-NTA column (1.5 mL resin per 10 g cells), which was preequilibrated with 5 column volumes (CV) of equilibration buffer [25 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 30 mM imidazonle, pH 8.0, 0.72% nonyl-β-d-maltoside (NM) (Anatrace)]. After the sample flowed through, the column was washed with 5 CV equilibration buffer and then 5 CV low imidazole buffer (25 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 100 mM imidazole, 0.64% NM). Finally, the target protein was eluted with high imidazole buffer (25 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 300 mM imidazole, 0.56% NM). The collected eluate with the target protein was concentrated in 50 kDa concentrator (Millipore) to around 15 mg/mL and then applied to a Superdex 200 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare) for further purification through size-exclusion chromatography (SEC). The protein was eluted in the SEC buffer containing 10 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.37% NM, 0.26% nonyl-β-d-glucoside (NG) (Anatrace), and 0.28% N-dodecyl-N,N-(dimethylammonio) butyrate (DDMAB) (Anatrace). The major peak fraction at ∼12.0 mL was collected and concentrated in a 100-kDa concentrator (Millipore) to around 17 mg/mL.

For the Form 2 crystal, the MaMscL-MjRS protein was prepared in a similar procedure but with different buffers. The recipe for the lysis buffer is 50 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 8.0, 200 mM NaCl, and 2% NG. The equilibration buffer for Ni-NTA column purification contains 25 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 30 mM imidazole (pH 8.0), and 0.8% NG. The low imidazole buffer contains 25 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 100 mM imidazole, and 0.6% NG, whereas the high imidazole elution buffer has 25 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 300 mM imidazole, and 0.4% NG. The SEC buffer is 10 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, and 0.4% NG.

Crystallization.

To crystallize MaMscL-MjRS in Form 1, 1 μL 17 mg/mL protein sample [doped with 1.2 mg/mL soy l-α-phosphatidylinositol (PI); Avanti Polar Lipids] was mixed with 1 μL reservoir solution (7% PEG4000, 0.4 M NH4SCN, and 0.1 M citric acid, pH 4.3) and then incubated through the sitting-drop vapor diffusion approach. Large rod-shaped crystals at a size of 0.1 × 0.1 × 0.4 mm usually grew within 1 wk at 16 °C. To harvest the crystals, they were gradually transferred to a drop of 10 μL cryoprotection solution with 10% PEG4000, 0.4 M NH4SCN, 0.1 M citric acid (pH 4.3), 0.37% NM, 0.26% NG, 0.28% DDMAB, 0.5 mg/mL soy PI, and 15% glycerol. The transfer was done with a small increment of 3% glycerol in each step to minimize osmotic shock on the crystal samples. At the final step, the crystals were harvested by nylon loops and quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen.

To obtain the Form 2 crystals, 1 μL protein sample at ∼15 mg/mL concentration was added to 1 μL reservoir solution containing 1.6 M (NH4)2SO4, 0.1 M NaCl, and 0.1 M Hepes (pH 7.5). Crystallization of the target protein was achieved through the hanging-drop vapor diffusion method. The Form 2 crystals grew much slower than the Form 1 crystals. These crystals grew in 5 mo after the drop was set up and had the morphology of thick and long rectangular plates. They were harvested directly from the drop and frozen in liquid nitrogen as fast as possible to avoid the formation of salt crystals, as the drop became severely dehydrated during the process.

Data Collection, Processing, and Structure Determination.

The X-ray diffraction data of the Form 1 crystal were collected at BL17U in the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF), whereas those of the Form 2 crystal were collected at BL17A in the Photon Factory (PF) at Tsukuba, Japan. The data were processed with HKL2000 (46) or imosflm-pointless-scala (47) programs. The anisotropy of the processed data was analyzed through the UCLA Diffraction Anisotropy Server (48). According to the server’s cutoff at 3.0 F/sigma, the data of Form 1 crystal have a resolution at 3.4 × 4.1 × 3.4 Å (a*×b*×c*), and the data of Form 2 crystal were nearly isotropic to 4.1 Å in all three directions. The overall statistics for data processing are summarized in Table S2.

The Form 1 and Form 2 crystal structures were both solved through molecular replacement (MR) methods, using the Phaser program (49) in the CCP4 suite (50). For the Form 1 data, the structural models of MjRS (PDB ID code 2B98, pentamer) and MtMscL (PDB ID code 2OAR, pentamer) were input to the program as two ensembles. A clear solution with high translation function Z (TFZ) score (22.3) and log likelihood gain (LLG) score (1,413) was found and contains one copy of MjRS pentamer and one copy of MtMscL pentamer (Fig. S1D). The model for the transmembrane domain (MaMscL) of the fusion protein was manually rebuilt in the Coot program (51). The sequence alignment among MaMscL, MtMscL, and SaMscL was used as a reference for guiding the model rebuilding process. The application of the deformable elastic network (DEN) in the CNS 1.3 program (52) proved to be helpful by providing additional restraints derived from the reference models for the refinement. The initial reference was the output model from the MR solution that combines the previously refined structures of MjRS (high resolution at 2.3 Å) and MtMscL (3.5 Å). The MaMscL part of the reference model was constantly updated with newly refined structure during the process. The noncrystallographic symmetry (NCS) restraint was applied throughout the structure refinement. Following refinement by the CNS program, the Refmac5 (53) program from the CCP4 suite was applied to further improve the model quality and the refinement was performed with local NCS and jelly-body restraints. The sigmaA-weighted 2Fo−Fc maps, the maps output from the DM program of the CCP4 suite, and the B-factor sharpened map obtained from Refmac5 were used to guide the model rebuilding process in Coot. The electron density maps computed with a parallel dataset with ellipsoidal truncation and anisotropic scaling provided detailed features of the amino acid side-chain information. After iterative cycles of program refinement and manual readjustment, the closed-state MaMscL-MjRS structure in the Form 1 crystal converged at 25.95% Rwork and 28.71% Rfree at an overall resolution of 3.5 Å (Fig. S1E).

For the data of the Form 2 crystal, the molecular replacement search with the MjRS pentamer alone yielded a solution with a TFZ score at 23.0 and LLG score at 904. The initial 2Fo-Fc electron density map was calculated with the model phases derived from the MjRS pentamer alone. The map exhibited clear and discernible features of 10 transmembrane helices (Fig. S1F). The N-helix and TM1 and TM2 helices taken from the refined structure of Form 1 crystal were placed into the tube-like electron densities to obtain the initial model of the MaMscL domain in Form 2 crystal. This model was further completed and optimized through iterative program refining and manual rebuilding processes. The final structure of Form 2 crystal was refined at 4.1 Å with Rwork at 32.07% and Rfree at 37.58% (Fig. S1G). Curiously, a well-defined electron density feature is found to intercalate in the hydrophobic constriction area around Phe23 residues (Fig. S4A) and can potentially be interpreted as a molecule of β-NG (detergent molecule) that may stabilize the channel at the expanded state.

Structure Analysis and Model Construction.

Graphic presentations were made by PyMOL (54) and Coot (51) programs. The HOLE program (55) was used to calculate the pore radii of the channels along their central axes. The geometric parameters (tilt angles and crossing angles) of the α-helices were measured in the Coot program. The data presented in Table S1 are the averaged values of the parameters extracted from all five subunits. The theoretical expanded-state pentameric MaMscL model was calculated based on the Spencer–Rees equation (35), using a protocol described in previous work (28). Briefly, a pair of TM1–TM2′ helices was aligned to the z axis with the Cα atom of Phe23 facing the origin and then pivoted about the x axis. The TM1–TM1′ crossing angle α varied from −40° to −60° in −1° steps. After the pivoting motion, the models were slightly readjusted to have their Gly26 residues following a short linear track between the start and end positions of the Gly26 residues in the experimental structures of closed-state and expanded-state MaMscL. The models of the N-helices shown in Movie S1 were constructed by using the PDBSET program from the CCP4 suite and then assembled with the TM1 and TM2 transmembrane helices.

Osmotic Downshock Assay.

The pET15b constructs carrying the target genes (wild-type or mutant MaMscL) or the control (EcMscL) were transformed into MJF465 (DE3) (mscl−, yggB−, kefA−) cells (9). The single colony picked from the plates was used to inoculate LB-Amp medium. The culture tubes were shaken at 220 rpm at 37 °C. Three hours later, 1 mL culture was taken and added to 1 mL prewarmed high-salt LB medium (1 M NaCl). The cells continued to grow for 2 h and then protein expression was induced with 0.5 mM IPTG for 2 h more. Afterward, the cultures were normalized to OD600 at ∼0.4 by adding LB-500 medium (regular LB mixed with high-salt LB at a 1:1 ratio). For the downshock tests, the cell cultures with normalized density were diluted into H2O by 100- or 1,000-fold. For the mock shock controls, the cells were diluted into isotonic LB-500 medium instead of water. After recovering at 37 °C for 20 min, 5 μL diluted cell suspension was pipetted on the LB-Amp agar plate and then incubated at 37 °C overnight to display the surviving colonies. The protein expression was confirmed through Western blot analysis by using the HRP-conjugated anti-Histag mAb antibody (Genscript) and the blots were developed with the Western Lightning ULTRA substrate (PerkinElmer).

Cell Growth Assay.

Single colonies of MJF465 (DE3) cells carrying the target/control genes (in pET15b vector) were transferred into LB medium with 100 μg/mL carbenicillin (Carb) and cultured for 5 h to OD600 at ∼1.0. The density of cultures was normalized to 0.1 OD600 through dilution with LB-Carb medium. Subsequently, 150 μL of the diluted culture was aliquoted into the wells on a 96-well plate (Costa) and then mixed with 10 μL of 0.32 mM IPTG stock solution to give a final concentration of IPTG at 0.02 mM. Each construct under test had three repeats. The plate was then placed into the infinite M1000 PRO plate reader (TECAN) and shaken linearly at 270 rpm. The absorbance of the cell culture in each well at 600-nm wavelength (Abs600) was continuously recorded every 20 min. The temperature was kept constant at 37 °C.

Electrophysiology.

The preparation of BL21(DE3)ΔmscL strain (56) E. coli giant spheroplasts expressing wild-type MaMscL, hairpin_6A mutant, or 6A-MjRS proteins was performed according to the protocol described previously (57, 58). The giant unilamellar vesicles (GUV) with target protein reconstituted (protein:lipid = 1:200, wt:wt; lipid, 95% azolectin + 5% cholesterol, wt:wt) were prepared through a modified sucrose method (59). Alternatively, the GUV samples were prepared through an electroformation protocol by using the dehydrated small unilamellar proteoliposome vesicles (protein:lipid = 1:100, wt:wt; lipid, 80% DPhPC + 10% POPG + 10% cholesterol, wt:wt:wt) obtained through a dialysis method on a Nanion Vesicle Prep Pro device (60).

The data on spheroplasts were acquired at +20 mV at a sampling rate of 20 kHz with a 5-kHz filter, using an AxoPatch 200B amplifier in conjunction with pClamp 10 software (Axon Instruments). The data on GUVs were acquired at +20 mV at 50 kHz with a 1-kHz filter and a 50-Hz notch filter, using an EPC-10 amplifier (HEKA). Negative pressure was applied manually through a syringe or through a Suction Control Pro pump (Nanion) with a stepwise or linear protocol while the voltage was held at +20 mV. The bath and pipette buffer both contained 200 mM KCl, 90 mM MgCl2, 10 mM CaCl2, and 5 mM Hepes (pH 6.0 for spheroplast or pH 7.0 for GUV).

Cross-Linking and Disulfide Trapping Experiments.

For cross-linking of MaMscL within the membranes, the BL21-gold (DE3) cells expressing MaMscL protein were resuspended in a buffer consisting of 50 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 8.0, and 200 mM NaCl. After sonication, the cell debris was removed by low-speed centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 30 min and the membrane fraction was collected by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g for at 4 °C for 1 h. The membrane pellet was resuspended in the buffer consisting of 100 mM Mes, pH 5.0, 150 mM NaCl, and then treated with 2.5 mM N,N′-Dicyclohexylcarbodiimide for 0–80 min at room temperature. The reactions were quenched by adding 100 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.5). The samples were loaded on SDS/PAGE and detected by Western blot, using the HRP-conjugated His-tag antibody (genscript).

For cross-linking in detergent solution, the purified MaMscL protein was diluted to 1 mg/mL in the reaction buffer consisting of 10 mM Hepes-Na (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl with 0.37% β-NM, 0.26% β-NG, and 0.28% DDMAB (or just 0.4% β-NG). The protein was cross-linked by 3.3 mM glutaraldehyde for 0–100 min at room temperature and the reactions were stopped by adding 100 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.5). The samples were loaded on SDS/PAGE and the gels were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R250.

The disulfide trapping experiments were performed according to the protocols described by Iscla et al. (44). The plasmids carrying the genes encoding the L3C/A89C, L3C/K90C, L3C/L93C, and E6C/Q94C mutants of MaMscL were transformed into the BL21(DE3) ΔmscL cells. Overnight cultures were diluted 1:100 to LB media and grown at 37 °C for 1 h. After adding the same volume of LB media with 1 M NaCl, the cells were further cultured for 1.5 h. Subsequently, IPTG was added to the culture at 0.5 mM final concentration to induce protein expression for 0.5 h. Then the cultures were treated by the mock-shock solutions (0.5 M NaCl without or with 1.5 μM copper-phenanthroline) or the down-shock solution (water with 1.5 μM copper-phenanthroline) at 1:20 dilution and incubated for 10 min at 37 °C. The samples were centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 20 min and then suspended in the SDS/PAGE loading buffer without any reducing agents. The samples were loaded on the gel and the protein bands were detected through Western blots, using His-tag antibody.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank D. C. Rees for reading the manuscript and the program used for generating the theoretical models of MaMscL, J. Y. Sun for sharing the electrophysiological devices, H. W. Pinkett and Y. H. Huang for discussion, M. Li for collecting the data of Form 2 crystals, X. Y. Liu and X. B. Liang for technical assistance on biochemistry, A. Laganowsky and T. Walton for BL21(DE3)ΔmscL cells, the staffs at the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility and the Photon Factory for their support during synchrotron data collection, and Y. Han at the core facility of the Institute of Biophysics for the help during in-house data collection. This project is financially supported by the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) (XDB08020302), the National 973 Project Grant 2014CB910301, the “135” Project of the CAS, and the “Startup Funding for the Awardees of the Outstanding PhD Thesis Fellowship” from the CAS. Z.L. is supported by the “National Thousand Young Talents” program from the Office of Global Experts Recruitment in China.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org [PDB ID codes 4Y7K (closed state) and 4Y7J (expanded state)].

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1503202112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Haswell ES, Phillips R, Rees DC. Mechanosensitive channels: What can they do and how do they do it? Structure. 2011;19(10):1356–1369. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chalfie M. Neurosensory mechanotransduction. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10(1):44–52. doi: 10.1038/nrm2595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kung C. A possible unifying principle for mechanosensation. Nature. 2005;436(7051):647–654. doi: 10.1038/nature03896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martinac B, Kloda A. Evolutionary origins of mechanosensitive ion channels. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2003;82(1–3):11–24. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6107(03)00002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martinac B. Mechanosensitive ion channels: Molecules of mechanotransduction. J Cell Sci. 2004;117(Pt 12):2449–2460. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson ME, Maksaev G, Haswell ES. MscS-like mechanosensitive channels in plants and microbes. Biochemistry. 2013;52(34):5708–5722. doi: 10.1021/bi400804z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perozo E. Gating prokaryotic mechanosensitive channels. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7(2):109–119. doi: 10.1038/nrm1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perozo E, Rees DC. Structure and mechanism in prokaryotic mechanosensitive channels. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2003;13(4):432–442. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(03)00106-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levina N, et al. Protection of Escherichia coli cells against extreme turgor by activation of MscS and MscL mechanosensitive channels: Identification of genes required for MscS activity. EMBO J. 1999;18(7):1730–1737. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.7.1730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blount P, Moe PC. Bacterial mechanosensitive channels: Integrating physiology, structure and function. Trends Microbiol. 1999;7(10):420–424. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(99)01594-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sukharev SI, Blount P, Martinac B, Blattner FR, Kung C. A large-conductance mechanosensitive channel in E. coli encoded by mscL alone. Nature. 1994;368(6468):265–268. doi: 10.1038/368265a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walton TA, Idigo CA, Herrera N, Rees DC. MscL: Channeling membrane tension. Pflugers Arch. 2015;467(1):15–25. doi: 10.1007/s00424-014-1535-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koçer A, Walko M, Meijberg W, Feringa BL. A light-actuated nanovalve derived from a channel protein. Science. 2005;309(5735):755–758. doi: 10.1126/science.1114760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koçer A, Walko M, Feringa BL. Synthesis and utilization of reversible and irreversible light-activated nanovalves derived from the channel protein MscL. Nat Protoc. 2007;2(6):1426–1437. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iscla I, et al. Improving the design of a MscL-based triggered nanovalve. Biosensors. 2013;3(1):171–184. doi: 10.3390/bios3010171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iscla I, Wray R, Wei S, Posner B, Blount P. Streptomycin potency is dependent on MscL channel expression. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4891. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iscla I, et al. A new antibiotic with potent activity targets MscL. J Antibiot. 2015;68:453–462. doi: 10.1038/ja.2015.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sukharev SI, Sigurdson WJ, Kung C, Sachs F. Energetic and spatial parameters for gating of the bacterial large conductance mechanosensitive channel, MscL. J Gen Physiol. 1999;113(4):525–540. doi: 10.1085/jgp.113.4.525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cruickshank CC, Minchin RF, Le Dain AC, Martinac B. Estimation of the pore size of the large-conductance mechanosensitive ion channel of Escherichia coli. Biophys J. 1997;73(4):1925–1931. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78223-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Y, et al. Single molecule FRET reveals pore size and opening mechanism of a mechano-sensitive ion channel. eLife. 2014;3:e01834. doi: 10.7554/eLife.01834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van den Bogaart G, Krasnikov V, Poolman B. Dual-color fluorescence-burst analysis to probe protein efflux through the mechanosensitive channel MscL. Biophys J. 2007;92(4):1233–1240. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.088708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sukharev S, Durell SR, Guy HR. Structural models of the MscL gating mechanism. Biophys J. 2001;81(2):917–936. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75751-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sukharev S, Betanzos M, Chiang C-S, Guy HR. The gating mechanism of the large mechanosensitive channel MscL. Nature. 2001;409(6821):720–724. doi: 10.1038/35055559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perozo E, Cortes DM, Sompornpisut P, Kloda A, Martinac B. Open channel structure of MscL and the gating mechanism of mechanosensitive channels. Nature. 2002;418(6901):942–948. doi: 10.1038/nature00992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li Y, Wray R, Eaton C, Blount P. An open-pore structure of the mechanosensitive channel MscL derived by determining transmembrane domain interactions upon gating. FASEB J. 2009;23(7):2197–2204. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-129296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Konijnenberg A, et al. Global structural changes of an ion channel during its gating are followed by ion mobility mass spectrometry. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(48):17170–17175. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1413118111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chang G, Spencer RH, Lee AT, Barclay MT, Rees DC. Structure of the MscL homolog from Mycobacterium tuberculosis: A gated mechanosensitive ion channel. Science. 1998;282(5397):2220–2226. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5397.2220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu Z, Gandhi CS, Rees DC. Structure of a tetrameric MscL in an expanded intermediate state. Nature. 2009;461(7260):120–124. doi: 10.1038/nature08277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dorwart MR, Wray R, Brautigam CA, Jiang Y, Blount P. S. aureus MscL is a pentamer in vivo but of variable stoichiometries in vitro: Implications for detergent-solubilized membrane proteins. PLoS Biol. 2010;8(12):e1000555. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iscla I, Wray R, Blount P. The oligomeric state of the truncated mechanosensitive channel of large conductance shows no variance in vivo. Protein Sci. 2011;20(9):1638–1642. doi: 10.1002/pro.686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gandhi CS, Walton TA, Rees DC. OCAM: A new tool for studying the oligomeric diversity of MscL channels. Protein Sci. 2011;20(2):313–326. doi: 10.1002/pro.562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iscla I, Levin G, Wray R, Reynolds R, Blount P. Defining the physical gate of a mechanosensitive channel, MscL, by engineering metal-binding sites. Biophys J. 2004;87(5):3172–3180. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.049833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walton TA, Rees DC. Structure and stability of the C-terminal helical bundle of the E. coli mechanosensitive channel of large conductance. Protein Sci. 2013;22(11):1592–1601. doi: 10.1002/pro.2360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anishkin A, Chiang CS, Sukharev S. Gain-of-function mutations reveal expanded intermediate states and a sequential action of two gates in MscL. J Gen Physiol. 2005;125(2):155–170. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200409118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spencer RH, Rees DC. The alpha-helix and the organization and gating of channels. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2002;31:207–233. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.31.082901.134329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bartlett JL, Levin G, Blount P. An in vivo assay identifies changes in residue accessibility on mechanosensitive channel gating. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(27):10161–10165. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402040101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blount P, Sukharev SI, Schroeder MJ, Nagle SK, Kung C. Single residue substitutions that change the gating properties of a mechanosensitive channel in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93(21):11652–11657. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ajouz B, Berrier C, Besnard M, Martinac B, Ghazi A. Contributions of the different extramembranous domains of the mechanosensitive ion channel MscL to its response to membrane tension. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(2):1015–1022. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.2.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsai IJ, et al. The role of the periplasmic loop residue glutamine 65 for MscL mechanosensitivity. Eur Biophys J. 2005;34(5):403–412. doi: 10.1007/s00249-005-0476-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ou X, Blount P, Hoffman RJ, Kung C. One face of a transmembrane helix is crucial in mechanosensitive channel gating. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(19):11471–11475. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.19.11471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Häse CC, Le Dain AC, Martinac B. Molecular dissection of the large mechanosensitive ion channel (MscL) of E. coli: Mutants with altered channel gating and pressure sensitivity. J Membr Biol. 1997;157(1):17–25. doi: 10.1007/s002329900212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Steinbacher S, Bass RPS, Rees DC. Structures of the prokaryotic mechanosensitive channels MscL and MscS. In: Hamill OP, editor. Current Topics in Membranes. Academic; London: 2007. pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Iscla I, Wray R, Blount P. On the structure of the N-terminal domain of the MscL channel: Helical bundle or membrane interface. Biophys J. 2008;95(5):2283–2291. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.127423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Iscla I, Wray R, Blount P. The dynamics of protein-protein interactions between domains of MscL at the cytoplasmic-lipid interface. Channels. 2012;6(4):255–261. doi: 10.4161/chan.20756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miroux B, Walker JE. Over-production of proteins in Escherichia coli: Mutant hosts that allow synthesis of some membrane proteins and globular proteins at high levels. J Mol Biol. 1996;260(3):289–298. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. In: Carter CW, Sweet RM, editors. Methods in Enzymology: Macromolecular Crystallography, Part A. Vol 276. Academic; New York: 1997. pp. 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Powell HR, Johnson O, Leslie AGW. Autoindexing diffraction images with iMosflm. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2013;69(Pt 7):1195–1203. doi: 10.1107/S0907444912048524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Strong M, et al. Toward the structural genomics of complexes: Crystal structure of a PE/PPE protein complex from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(21):8060–8065. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602606103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McCoy AJ, et al. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Cryst. 2007;40(Pt 4):658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4 The CCP4 suite: Programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1994;50(Pt 5):760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66(Pt 4):486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schröder GF, Levitt M, Brunger AT. Super-resolution biomolecular crystallography with low-resolution data. Nature. 2010;464(7292):1218–1222. doi: 10.1038/nature08892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Murshudov GN, et al. REFMAC5 for the refinement of macromolecular crystal structures. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2011;67(Pt 4):355–367. doi: 10.1107/S0907444911001314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Delano WL. 2002. The PyMOL Molecular Graphic System, 1.7.0.1 (Delano Scientific, San Carlos, CA)

- 55.Smart OS, Neduvelil JG, Wang X, Wallace BA, Sansom MSP. HOLE: A program for the analysis of the pore dimensions of ion channel structural models. J Mol Graph. 1996;14(6):354–360, 376. doi: 10.1016/s0263-7855(97)00009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Laganowsky A, et al. Membrane proteins bind lipids selectively to modulate their structure and function. Nature. 2014;510(7503):172–175. doi: 10.1038/nature13419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Martinac B, Buechner M, Delcour AH, Adler J, Kung C. Pressure-sensitive ion channel in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84(8):2297–2301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.8.2297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Blount P, Sukharev SI, Moe PC, Martinac B, Kung C. Mechanosensitive channels of bacteria. Methods Enzymol. 1999;294:458–482. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)94027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Battle AR, Petrov E, Pal P, Martinac B. Rapid and improved reconstitution of bacterial mechanosensitive ion channel proteins MscS and MscL into liposomes using a modified sucrose method. FEBS Lett. 2009;583(2):407–412. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Barthmes M, et al. Studying mechanosensitive ion channels with an automated patch clamp. Eur Biophys J. 2014;43(2–3):97–104. doi: 10.1007/s00249-014-0944-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.