Abstract

Background

Managing hyperglycemia and diabetes is challenging in geriatric patients admitted to long-term care (LTC) facilities.

Methods

This randomized control trial enrolled patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) with blood glucose (BG) >180 mg/dL or glycated hemoglobin >7.5% to receive low-dose basal insulin (glargine, starting dose 0.1 U/kg/day) or oral antidiabetic drug (OAD) therapy as per primary care provider discretion for 26 weeks. Both groups received supplemental rapid-acting insulin before meals for BG >200 mg/dL. Primary end point was difference in glycemic control as measured by fasting and mean daily glucose concentration between groups.

Results

A total of 150 patients (age: 79±8 years, body mass index: 30.1±6.5 kg/m2, duration of diabetes mellitus: 8.2±5.1 years, randomization BG: 194±97 mg/dL) were randomized to basal insulin (n=75) and OAD therapy (n=75). There were no differences in the mean fasting BG (131±27 mg/dL vs 123±23 mg/dL, p=0.06) between insulin and OAD groups, but patients treated with insulin had greater mean daily BG (163±39 mg/dL vs 138±27 mg/dL, p<0.001) compared to those treated with OADs. There were no differences in the rate of hypoglycemia (<70 mg/dL) between insulin (27%) and OAD (31%) groups, p=0.58. In addition, there were no differences in the number of hospital complications, emergency room visits, and mortality between treatment groups.

Conclusions

The results of this randomized study indicate that elderly patients with T2D in LTC facilities exhibited similar glycemic control, hypoglycemic events and complications when treated with either basal insulin or with oral antidiabetic drugs.

Trial registration number

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01131052.

Keywords: Hypoglycemia, Elderly, Hyperglycemia, Insulin

Key messages.

This prospective randomized clinical trial compared differences in glycemic control, clinical outcome and frequency of hypoglycemic events in elderly patients with diabetes treated with basal insulin and OADs in LTC facilities.

We report that a similar glycemic control can be achieved with either basal insulin or with oral anti-diabetic agents in elderly patients with type 2 diabetes admitted to long-term care facilities.

No difference in the frequency of hypoglycemia, length of stay, need for emergency room visit, hospital admission or mortality was observed between treatment groups.

Introduction

Diabetes is an increasing global health burden with a highest age-specific prevalence in people 60–79 years of age.1 The estimated prevalence of diabetes in long-term care facilities is around 15% to 34%.2–8 Nursing home residents with diabetes have higher rates of serious comorbidities and have greater activity of daily living dependencies than residents without diabetes.5 In addition, persons with diabetes have higher risk of hypertension, heart disease, stroke depression, cognitive impairment and cardiovascular disease than individuals without diabetes.9

Management of hyperglycemia is challenging in the geriatric population in long-term facilities.10 Numerous factors place hospitalized patients at increased risk for hyperglycemia including aging, sedentary life, stress of medical and surgical comorbidities and changes in antidiabetic regimen.11 In addition, elderly patients often experience changes in their nutritional intake and organ dysfunction; these changes increase the risk of hypoglycemic events. In general, therapy is aimed at attaining optimal levels of serum glucose while avoiding the acute complications of hypoglycemia or uncontrolled hyperglycemia, and preventing or delaying the progression of the chronic complications of diabetes.12 The American Diabetes Association guidelines for management of healthy elderly patients with diabetes are not different from those for younger adults. In these participants, an glycated hemoglobin (HbA1C) level less than 7% (53 mmol/mol), fasting glucose between 90–130 mg/dL, and random glucose <180 mg/dL is recommended.13 The American Geriatric Society and other international societies recommend a goal HbA1C of 7–7.5% in healthy adults with good functional status.14 15 A higher level of HbA1C, ranging from 7% to 8% (64 mmol/mol), may be more appropriate in the presence of comorbidities, frailty and increased risk of hypoglycemia or drug side effects. A goal HbA1C of less than 8.5% has been recommended for those with limited remaining life expectancy due to the uncertain long-term benefit of glycemic control.13 14

Few retrospective studies in elderly patients have analyzed quality of diabetes care and glycemic control in long-term care facilities.6 16–19 However, no randomized controlled trials have compared insulin versus oral agent treatment on glycemic control, risk of hypoglycemia and complications in long-term care residents. Accordingly, we conducted a prospective, randomized controlled trial comparing the efficacy and safety of treatment with basal insulin, and OAD regimen in nursing home patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D).

Research design and methods

Study population

Patients with T2D with a BG >180 mg/dL or with an HbA1C >7.5% treated with diet and/or oral antidiabetic agents (metformin, insulin secretagogues, thiazolidinediones or DPP-4 inhibitors) were enrolled in the study. The study was conducted at Bud Terrace and AG Rhodes, two long-term care facilities affiliated with the Emory Healthcare System in Atlanta, Georgia. Long-term residents and patients undergoing subacute rehabilitation in the two facilities were included in the study. Exclusion criteria included hyperglycemia without a previous diagnosis of T2D, history of hyperglycemic crises, clinically relevant hepatic disease, impaired renal function (creatinine ≥3.5 mg/dL), corticosteroid therapy and inability to comprehend the nature and scope of the study or to sign the consent form. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board at Emory University.

Design and intervention

We conducted a prospective, pilot, open-label randomized clinical trial. After identification of eligible patients, research staff obtained informed consent, and participants were randomized in a parallel design with a computer-generated assignment, to either basal insulin or to oral antidiabetic drug (OAD) therapy in a 1:1 ratio. Individuals independent of intervention delivery and outcome assessments, performed sequence generation and allocation concealment. At enrollment (0 week), patients were either randomized to receive a single dose of glargine (0.1 units/kg/day) or to continue OADs. The total daily dose of insulin glargine was increased by 10% every 3–5 days for fasting and premeal BG between 181 and 200 mg/dL, and by 20% for fasting and premeal BG >200 mg/dL. The dose was maintained if BG levels remained between 100 and 180 mg/dL. The dose of insulin glargine was reduced by 20% for fasting and premeal BG between 70 and 99 mg/dL, by 30% for BG between 41 and 69%, and by 40% for BG <40 mg/dL. Supplemental insulin with insulin glulisine was given for BG >200 mg/dL per sliding-scale. Patients randomized to OAD continued oral agents (metformin, sulfonylureas, repaglinide, nateglinide, pioglitazone, rosiglitazone or DPP-4 inhibitors) unless there were contraindications, and supplemental insulin with regular insulin was started for BG >200 mg/dL per sliding-scale protocol. The attending physician could further adjust oral medications and the insulin dose at his/her discretion in the presence of severe glycemic excursions.

Outcomes measures

The primary outcome of the study was to determine differences in glycemic control as measured by mean fasting and daily BG concentration between treatment groups. Secondary outcomes included differences between treatment groups in any of the following measures: occurrence rate of hypoglycemic events (<70 mg/dL) and severe hypoglycemia (<40 mg/dL). Each hypoglycemic event was considered as an index event with duration of up to 6 h, subsequent episodes were considered independent from the initial episode. In addition, information was collected on the total daily dose of insulin; length of stay; prevalence of infectious complications (pneumonia, urinary tract infections, bedsores, diabetic foot infection); need for emergency room visits or hospitalization during the study period, cardiac complications defined as myocardial infarction, cardiac arrhythmia requiring medical treatment and congestive heart failure; acute kidney injury defined as an increment >0.5 mg/dL from baseline or a serum creatinine >2.0 mg/dL; and hospital mortality defined as death occurring during admission.

Statistical analysis

We conducted an intention-to-treat analysis; no patients were lost to follow-up in the study. For the primary outcome, we performed non-parametric Wilcoxon tests to assess the difference between the two treatment groups. We conducted χ2 tests (or Fisher's Exact tests) to analyze discrete secondary outcomes including hypoglycemic or hyperglycemic events, cardiac complications and acute renal failure. A p value of <0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS (V.9.2, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

A total of 150 patients with T2D gave consent and were randomized to basal insulin (n=75) and OAD (n=75) therapy. The clinical characteristics of study patients are shown in table 1. Groups were well matched without significant differences in mean age, gender, racial distribution, BMI, duration of diabetes, previous diabetes therapy and comorbidities. In the OAD treatment group, 21 (28%) patients received treatment with metformin alone, 12 (16%) patients were treated with a combination of metformin and sulfonylurea, and 6 (8%) patients were treated with a combination of metformin and other agents. A total of 20 (26.7%) patients were treated with sulfonylurea alone and 6 (8%) were treated with a combination of sulfonylurea and a DPP-4 inhibitor. Six (8%) patients were treated with diet alone, 2 (2.7%) patients were treated with a TZD and 2 (2.7%) were treated with meglitinides.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of study patients

| Basal insulin | OAD | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 75 | 75 | |

| Gender, n (F/M) | 49/26 | 47/28 | 0.73 |

| Age, years | 79±8 | 79±8.1 | 0.97 |

| Race: black/white/other, n | 24/49/1 | 29/44/2 | 0.28 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 30±6 | 30±7 | 0.73 |

| Diabetes duration, years | 8.6±4.9 | 7.7±5.2 | 0.15 |

| HbA1C, % | 6.9±0.9 | 6.5±0.7 | 0.05 |

| Previous diabetes therapy | 0.95 | ||

| Metformin, n (%) | 19 (25) | 21 (28) | |

| Sulfonylurea (SU), n (%) | 21 (28) | 20 (27) | |

| DPP-4i, n (%) | 8 (11) | 6 (8) | |

| Other, n (%) | 27 (36) | 28 (37) | |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Hypertension, n (%) | 68 (91) | 61 (81) | 0.16 |

| Coronary heart disease, n (%) | 25 (36) | 22 (29) | 0.11 |

| Heart failure, n (%) | 29 (39) | 21 (28) | 0.17 |

| Acute kidney injury, n (%) | 21 (28) | 23 (31) | 0.72 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 34 (45) | 33 (44) | 0.87 |

| Dementia, n (%) | 27 (36) | 18 (24) | 0.11 |

| Mental illness, n (%) | 33 (44) | 25 (33) | 0.18 |

| Admission area | 0.99 | ||

| Subacute Rehab | 70 (93) | 69 (92) | |

| Long-term care | 5 (7) | 6 (8) | |

HbA1C, glycated hemoglobin; BMI, body mass index.

Patients randomized to the basal insulin group had a higher hemoglobin HbA1C compared to the OAD group (6.9±0.9% vs 6.5±0.7%, p=0.049). Most patients were admitted for a subacute rehabilitation program (SAR). The duration of admission was similar between groups (32±40 days vs 31±44 days, p=0.30).

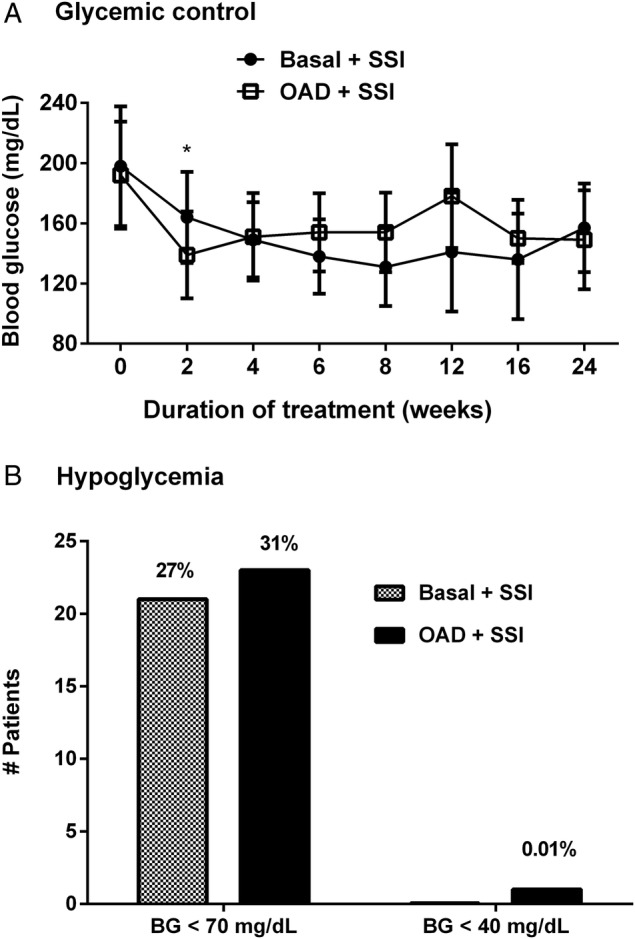

The admission BG (144±42 mg/dL vs 137±44, mg/dL, p=0.27) and randomization BG (198±40 mg/dL vs 192±35 mg/dL, p=0.20) were similar between basal insulin and OAD groups. Both treatment regimens resulted in a sustained improvement in mean daily BG concentration during the LTC stay (figure 1). Mean fasting BG during therapy was not significantly different between basal insulin and OAD groups (131±27 mg/dL vs 123±23 mg/dL, p=0.06). The overall mean daily BG level was lower in patients treated with OAD compared to basal insulin (138±27 mg/dL vs 163±39 mg/dL, p<0.05). Overall daily BG did not differ between groups (figure 1). As expected, the total daily insulin dose was higher in the insulin group compared to the OAD group (0.2±0.2 vs 0.1±0.3 U/kg/day, respectively, p<0.001).

Figure 1.

Mean daily glucose concentration and frequency of hypoglycemia in long-term care residents with type 2 diabetes. (A) Mean daily glucose concentration in patients treated with basal insulin (●) and oral antidiabetic agents (□). (B) Frequency of hypoglycemia (<70 mg/dL) and severe hypoglycemia (<40 mg/dL; *p value <0.05).

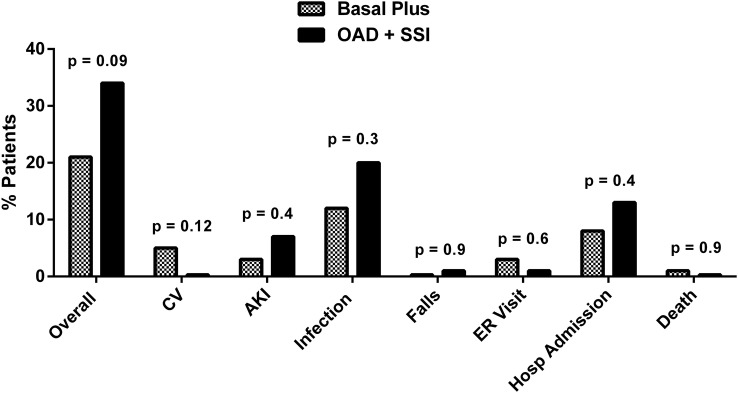

The rate of hospital complications including cardiovascular (acute myocardial infarction, cardiac arrhythmia requiring medical treatment and congestive heart failure), acute kidney failure, infection (pneumonia, urinary tract infections, bedsores and diabetic foot infection), falls, emergency room (ER) visits, hospital admissions or mortality (death occurring during admission) was similar between groups (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Composite of complications including cardiovascular (CV): acute myocardial infarction, cardiac arrhythmia requiring medical treatment and heart failure; acute kidney injury (AKI) defined as serum creatinine >2 mg/dL or an increment >0.5 mg/dL from baseline; infectious complications: pneumonia, urinary tract infections, foot infection; falls; emergency room visits; and mortality.

There were no differences in the frequency of hypoglycemia between patients treated with basal insulin or with OADs. BG values <70 were reported in 27% of patients with basal insulin and in 31% of patients treated with OADs. Nine (12%) patients in basal and 13 (17%) in OAD had ≥2 episodes of hypoglycemia. A non-statistically significant excess in the total number of hypoglycemic events was observed in the OAD group compared to basal plus supplements (62 events vs 43 events, p=0.4). In addition, there were no differences in the frequency of hypoglycemia in either group in patients treated with insulin or OADs (see online supplementary table).

In the OAD group, there was a higher but not statistically significant difference in the incidence of hypoglycemia between patients receiving sulfonylureas alone or in combination with other agents (34%) versus no-sulfonylurea use (28%), p=0.5. Severe hypoglycemia defined as a BG <40 mg/dL was uncommon (figure 1). Patients with hypoglycemia (n=43) had more episodes of acute kidney injury (12% vs 2%, p=0.02) and a higher rate of a composite of complications (40% vs 22%, p=0.033) compared to patients who did not develop hypoglycemia (n=107).

Discussion

This prospective randomized clinical trial compared glycemic control, clinical outcome and frequency of hypoglycemic events in elderly patients with T2D treated with basal insulin and OADs in LTC facilities. Most of the patients enrolled in our study were admitted to LTC facilities for subacute rehabilitation. We observed that both treatment regimens resulted in a rapid and sustained improvement in glycemic control without significant differences between patients treated with basal insulin or with OADs. In addition, we observed no differences in the frequency of hypoglycemia, length of stay, need for ER visit, hospital admission or mortality between treatment groups.

Few prospective randomized studies have reported on the safety and efficacy of different treatment strategies in elderly patients with diabetes admitted to LTC facilities. In general, recommendations for the management of diabetes in this population are extrapolated from studies in the hospital setting or from ambulatory patients with diabetes.15 20–24 Most nursing home residents with T2D are managed with insulin and/or oral antidiabetic agents,12 25 26 with basal insulin being recommended as the first-line therapy,27 28 and OAD agents usually considered to be less safe and effective than insulin therapy. In contrast to previous beliefs, our results indicate no significant differences in efficacy and safety of insulin and OAD treatment in elderly nursing home patients with type 2 diabetes.

A major finding in our study is that treatment with a low dose of basal insulin and OAD resulted in a similar frequency of hypoglycemia, with ∼30% of patients in both groups. A higher but non-significant proportion of patients receiving sulfonylureas alone or in combination with other agents (34%) develop hypoglycemia compared to participants not exposed to sulfonylureas (28%). Previous studies have highlighted the importance of avoiding hypoglycemia in the elderly, as it may be associated with increased risk of complications and mortality.6 29–32 Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) gathered from 2001 through 2010 suggest that a large proportion of older adults with diabetes are potentially overtreated. Of the older adults with an HbA1C level of less than 7%, more than half were treated with either insulin or sulfonylurea, agents that may lead to severe hypoglycemia.33 In a recent observational study in 1409 LTC residents, we reported that 42% of patients had ≥1 episodes of hypoglycemia and patients with hypoglycemia were more likely to require emergency room, hospital transfers and had higher mortality, than patients without hypoglycemia.6 In agreement with these studies, we found that patients with hypoglycemia experienced more episodes of acute kidney injury and a higher rate of complications compared to patients without hypoglycemia. These results emphasize the need for prevention of hypoglycemia with agents not associated with hypoglycemia in this vulnerable population. In this regard, a multicenter study is currently underway comparing the safety and efficacy of DPP-4 inhibitors and low-dose basal insulin in LTC facilities (NCT02061969).

Our study confirmed the results of previous studies that showed that glycemic control in elderly nursing home residents with diabetes is more often tight than poor.34 35 The average HbA1C levels reported in numerous nursing home studies have ranged between 5.9% and 7.5%,35–38 with HbA1C goals achieved in more than three-fourths of nursing home patients.34 35 Current guidelines for older residents with diabetes mellitus suggest that HbA1C goals be individualized,24 39 40 with an HbA1C target of <7.5% in residents with good cognitive and functional status and without significant hypoglycemia.13 A target of 8–8.5% may be appropriate in residents with a history of severe hypoglycemia, limited life expectancy, comorbid conditions and longstanding diabetic complications.27 28 In our study, we randomized most patients with persistent fasting and premeal hyperglycemia. It is not known if tailoring therapy guiding for correction of fasting or daily hyperglycemia has the same impact in improving outcome or in reducing the frequency of hypoglycemia compared to a targeted HbA1C level in elderly participants with type 2 diabetes.

The main limitations of our study include its small sample size, and the relatively well-controlled population enrolled in the study based on HbA1C alone. The fact that patients were selected based on their previous regimen, including diet with or without oral agents, likely skewed our sample towards a better-controlled population, which probably does not reflect the overall glycemic control spectrum among all institutionalized patients with diabetes. Our study does suggest, however, that a significant proportion of patients are potentially overtreated in LTC or SAR (>50% were treated with sulfonylureas before enrollment). Another limitation is the relatively shorter length of stay (over a month) of most patients. Given the above limitations, the generalization of our results to all older adults with diabetes, in LTC or SAR facilities, is not possible, as patients treated with insulin or combinations of insulin with oral agents who are potentially more fragile (LTC residents particularly), might be at an even higher risk for hypoglycemia than the patients enrolled in our study. Larger and longer studies are needed to address these additional questions.

In summary, our randomized controlled study indicates that elderly residents with relatively well controlled T2D in LTC facilities and subacute rehabilitation settings can achieve and maintain similar glycemic control, and experience a similar rate of hypoglycemic events, when treated with either a low dose of basal insulin or with oral antidiabetic agents. Further studies that include patients with a wider range of glycemic control, including previous treatment with insulin are needed to further understand different therapeutic regimens, and to develop strategies aimed at preventing hypoglycemia in this vulnerable population.

Footnotes

Contributors: GEU is the guarantor of the study and takes full responsibility for the research work. GEU is the principal investigator and designed the study protocol. FP and GEU wrote the manuscript. WP, TJ, SY, MT, PA, CN and DS edited the manuscript and participated in conducting the study. LP performed data analyses.

Funding: This investigator-initiated study was supported by an unrestricted grant from Sanofi Aventis (Bridgewater, New Jersey, USA) to Emory University. GEU is supported in part by research grants from the American Diabetes Association (1-14-LLY-36), PHS grant UL1 RR025008 from the Clinical Translational Science Award Program (M01 RR-00039), has received unrestricted research support for inpatient studies (to Emory University) from Sanofi, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Boehringer Ingelheim and has received consulting fees or/and honoraria for participation in advisory boards from Novo Nordisk, Regeneron, Sanofi, Merck and Boehringer Ingelheim. DS has received research support (to Emory University) from Abbott, Merck, and Sanofi, and has received fees or/and honoraria for participation in advisory committees from Janssen, Sanofi and Boehringer Ingelheim.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board at Emory University.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Guariguata L, Whiting DR, Hambleton I et al. Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2013 and projections for 2035. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2014;103:137–49. 10.1016/j.diabres.2013.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mooradian AD, Osterweil D, Petrasek D et al. Diabetes mellitus in elderly nursing home patients. A survey of clinical characteristics and management. J Am Geriatr Soc 1988;36:391–6. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1988.tb02376.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Funnell MM, Herman WH. Diabetes care policies and practices in Michigan nursing homes, 1991. Diabetes Care 1995;18:862–6. 10.2337/diacare.18.6.862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hauner H, Kurnaz AA, Haastert B et al. Undiagnosed diabetes mellitus and metabolic control assessed by HbA(1c) among residents of nursing homes. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 2001;109:326–9. 10.1055/s-2001-17299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Travis SS, Buchanan RJ, Wang S et al. Analyses of nursing home residents with diabetes at admission. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2004;5:320–7. 10.1016/S1525-8610(04)70021-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Newton CA, Adeel A, Sadeghi-Yarandi S et al. Prevalence, quality of care and complications in long-term care residents with diabetes: a multicenter observational study. JAMDA 2013;14:842–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang X, Decker FH, Luo H et al. Trends in the prevalence and comorbidities of diabetes mellitus in nursing home residents in the United States: 1995–2004. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58:724–30. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02786.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moore KL, Boscardin WJ, Steinman MA et al. Age and sex variation in prevalence of chronic medical conditions in older residents of U.S. nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012;60:756–64. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03909.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morley JE. An overview of diabetes mellitus in older persons. Clin Geriatr Med 1999;15:211–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McNabney MK, Pandya N, Iwuagwu C et al. Differences in diabetes management of nursing home patients based on functional and cognitive status. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2005;6:375–82. 10.1016/j.jamda.2005.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smiley DD, Umpierrez GE. Perioperative glucose control in the diabetic or nondiabetic patient. South Med J 2006;99:580–9; quiz 590–581 10.1097/01.smj.0000209366.91803.99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haas L. Management of diabetes mellitus medications in the nursing home. Drugs Aging 2005;22:209–18. 10.2165/00002512-200522030-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Diabetes A. (10) Older adults. Diabetes Care 2015;38(Suppl):S67–69. 10.2337/dc15-S013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moreno G, Mangione C, Kimbro L et al. Guidelines abstracted from the American Geriatrics Society Guidelines for Improving the Care of Older Adults with Diabetes Mellitus: 2013 update. J Am Geriatr Soc 2013;61:2020–6. 10.1111/jgs.12513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sinclair A, Morley JE, Rodriguez-Manas L et al. Diabetes mellitus in older people: position statement on behalf of the International Association of Gerontology and Geriatrics (IAGG), the European Diabetes Working Party for Older People (EDWPOP), and the International Task Force of Experts in Diabetes. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2012;13:497–502. 10.1016/j.jamda.2012.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alsabbagh MW, Mansell K, Lix LM et al. Trends in prevalence, incidence and pharmacologic management of diabetes mellitus among seniors newly admitted to long-term care facilities in Saskatchewan between 2003 and 2011. Can J Diabetes 2015;39:138–45. 10.1016/j.jcjd.2014.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davis KL, Wei W, Meyers JL et al. Use of basal insulin and the associated clinical outcomes among elderly nursing home residents with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a retrospective chart review study. Clin Interv Aging 2014;9:1815–22. 10.2147/CIA.S65411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pandya N, Wei W, Meyers JL et al. Burden of sliding scale insulin use in elderly long-term care residents with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Am Geriatr Soc 2013;61:2103–10. 10.1111/jgs.12547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feldman SM, Rosen R, DeStasio J. Status of diabetes management in the nursing home setting in 2008: a retrospective chart review and epidemiology study of diabetic nursing home residents and nursing home initiatives in diabetes management. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2009;10:354–60. 10.1016/j.jamda.2009.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.American Diabetes A. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2014. Diabetes Care 2014;37(Suppl 1):S14–80. 10.2337/dc14-S014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Association AMD. Diabetes management in the long term care setting. Columbia, MD: American Medical Directors Association, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sinclair AJ. Good clinical practice guidelines for care home residents with diabetes: an executive summary. Diabet Med 2011;28:772–7. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2011.03320.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sinclair AJ, Paolisso G, Castro M et al. European Diabetes Working Party for Older People 2011 clinical guidelines for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Executive summary. Diabetes Metab 2011;37(Suppl 3):S27–38. 10.1016/S1262-3636(11)70962-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zarowitz BJ, Stefanacci R, Hollenack K et al. The application of evidence-based principles of care in older persons (issue 1): management of osteoporosis. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2006;7: 102–8. 10.1016/j.jamda.2005.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Souto Barreto P, Sanz C, Vellas B et al. Drug treatment for diabetes in nursing home residents. Diabet Med 2014;31:570–6. 10.1111/dme.12354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pandya N, Thompson S, Sambamoorthi U. The prevalence and persistence of sliding scale insulin use among newly admitted elderly nursing home residents with diabetes mellitus. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2008;9:663–9. 10.1016/j.jamda.2008.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.[No authors listed] Summary of revisions for the 2009 Clinical Practice Recommendations. Diabetes Care 2009;32 1):S3–5. 10.2337/dc08-1206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.American Medical Directors Association. Diabetes management in the long-term care setting: clinical practice guideline. Columbia, MD: American Medical Directors Association, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gerstein HC, Miller ME, Byington RP et al. Effects of intensive glucose lowering in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2008;358:2545–59. 10.1056/NEJMoa0802743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duckworth W, Abraira C, Moritz T et al. Glucose control and vascular complications in veterans with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2009;360:129–39. 10.1056/NEJMoa0808431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patel A, MacMahon S, Chalmers J et al. Intensive blood glucose control and vascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2008;358:2560–72. 10.1056/NEJMicm066227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boussageon R, Bejan-Angoulvant T, Saadatian-Elahi M et al. Effect of intensive glucose lowering treatment on all cause mortality, cardiovascular death, and microvascular events in type 2 diabetes: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2011;343:d4169 10.1136/bmj.d4169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lipska KJ, Ross JS, Miao Y et al. Potential overtreatment of diabetes mellitus in older adults with tight glycemic control. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:356–62. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.7345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sjoblom P, Tengblad A, Lofgren UB et al. Can diabetes medication be reduced in elderly patients? An observational study of diabetes drug withdrawal in nursing home patients with tight glycaemic control. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2008;82:197–202. 10.1016/j.diabres.2008.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lofgren UB, Rosenqvist U, Lindstrom T et al. Diabetes control in Swedish community dwelling elderly: more often tight than poor. J Intern Med 2004;255:96–101. 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2003.01261.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holt RM, Schwartz FL, Shubrook JH. Diabetes care in extended-care facilities: appropriate intensity of care? Diabetes Care 2007;30:1454–8. 10.2337/dc06-2311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bouillet B, Vaillant G, Petit JM et al. Are elderly patients with diabetes being overtreated in French long-term-care homes? Diabetes Metab 2010;36:272–7. 10.1016/j.diabet.2010.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gill EA, Corwin PA, Mangin DA et al. Diabetes care in rest homes in Christchurch, New Zealand. Diabet Med 2006;23:1252–6. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01976.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brown AF, Mangione CM, Saliba D et al. Guidelines for improving the care of the older person with diabetes mellitus. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003;51(5 Suppl Guidelines):S265–80. 10.1034/j.1600-0579.2003.00211.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meyers RM, Broton JC, Woo-Rippe KW et al. Variability in glycosylated hemoglobin values in diabetic patients living in long-term care facilities. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2007;8:511–14. 10.1016/j.jamda.2007.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]