Abstract

Objectives

To elicit sources of waste as viewed by hospital workers

Design

Qualitative study using photo-elicitation, an ethnographic technique for prompting in-depth discussion

Setting

U.S. academic tertiary care hospital

Participants

Physicians, nurses, pharmacists, administrative support personnel, administrators and respiratory therapists

Methods

A purposive sample of personnel at an academic tertiary care hospital was invited to take up to 10 photos of waste. Participants discussed their selections using photos as prompts during in-depth interviews. Transcripts were analyzed in an iterative process using grounded theory; open and axial coding was performed, followed by selective and thematic coding to develop major themes and sub-themes.

Results

Twenty-one participants (9 women, average number of years in field=19.3) took 159 photos. Major themes included types of waste and recommendations to reduce waste. Types of waste comprised four major categories: Time, Materials, Energy and Talent. Participants emphasized time wastage (50% of photos) over other types of waste such as excess utilization (2.5%). Energy and Talent were novel categories of waste. Recommendations to reduce waste included interventions at the micro-level (e.g. individual/ward), meso-level (e.g. institution) and macro-level (e.g., payor/public policy).

Conclusions

The waste hospital workers identified differed from previously described waste both in the types of waste described and the emphasis placed on wasted time. The findings of this study represent a possible need for education of hospital workers about known types of waste, an opportunity to assess the impact of novel types of waste described and an opportunity to intervene to reduce the waste identified.

Keywords: health care waste, photo-elicitation, hospital workers’, perspectives

INTRODUCTION

The United States spends more on health care than any other country and has the highest rates of spending growth among developed countries. (1) Although economists have argued that increased health care spending has economic benefits, (2) others have cautioned that it lowers economic growth and employment. (3) Additionally, even though increased utilization accounts for a substantial portion of increased health care spending, (4,5) higher utilization does not consistently correlate with better patient outcomes. (6–8)

Efforts to reduce health care spending began more than three decades ago. (9,10) Despite these efforts, a recent Institute of Medicine (IOM) report estimates that there were $765 billion dollars in excess health care costs in 2009. These costs were attributed to unnecessary and inefficiently delivered services, excess administrative costs, inflated prices, missed prevention opportunities and fraud. (11) Several strategies and tools have been developed in an attempt to reduce these types of waste, including Lean Six Sigma (LSS), which applies manufacturing quality improvement principles (12), the Institute for Health care Improvement’s (IHI) Hospital Inpatient Waste Identification Toolkit, which provides hospitals with worksheets designed to identify waste in five categories (13), the Agency for Health care Research and Quality’s (AHRQ) “Health Care Efficiency Measures” and Premier’s Waste Dashboard (14,15). Although interventions using these strategies have shown promise for improving care processes (16–22), it is less clear how these interventions impact utilization and patient outcomes. (23–25)

Photo-elicitation is a common ethnographic technique that involves use of photos to prompt discussions about the area of inquiry during in-depth interviews. (26, 27) Auto-photography (or reflexive photography) refers to a study design in which participants (rather than the investigator) take the photos used in the study. (28, 29) Auto-photography has been used to study questions related to health care processes and the impact of building design on patient recovery. (30–32)

In the study we describe here, we used photo-elicitation with auto-photography to identify sources of waste in the health care system from the hospital workers’ perspective. Recommendations for reducing waste were elicited from the health care workers as well. Our objective was to further explore how health care workers’ perceptions may inform the dialogue about waste reduction in health care.

METHODS

Study population

Participants were purposively sampled from high volume departments in the hospital (e.g., emergency room) and/or those that incur high costs (e.g., cardiac catheterization lab, intensive care units). This sampling strategy was designed to increase the likelihood of eliciting types of waste whose reduction would have substantial impact on costs or patient outcomes. Recommendations from research team members and colleagues were used to decide which individuals from the target departments were invited to participate in the study. As a secondary recruitment strategy, participants were asked to refer colleagues (snowball or chain-referral sampling) (33) whom they thought would have an interest in participating in the study.

Auto-photography and photo-elicitation

Auto-photography/photo-elicitation was chosen for this study because of the unique way in which still photography engages visual and verbal centers in the brain and stimulates discussion during an in-depth interview. (28, 29, 34). A photographic image is “true” in the sense that it is a visual representation of what the camera was pointed at. (28, 34) Yet, the photographer’s perspective on the picture can be further explored during an in-depth interview. (28, 29, 35) There is an element of reflexivity, or embedding of the participant’s perspective in the research, because the participants choose what to photograph and what to ignore. (28) Finally, use of auto-photography also allows the interviewer to more readily join the participant in the discussion since they share an empiric piece of data during the interview. (28, 29)

Study design and data collection

Participants were asked to limit themselves to 10 photos representing health care waste because repeated sampling of the same subject can lead to “intellectually and analytically thin work”. (35) Participants took photos with their own digital cameras or a digital study camera. No prompts for what might represent waste were provided so that participants could identify waste as they saw it. Participants were given two weeks to take photos. Shortly after the end of a participant’s photo-taking period, an in-depth semi-structured interview was held with RK. MR and/or SG were present at the interviews. RK led all interviews using a standardized interview guide (Appendix A). Photos were downloaded to a study computer at the time of the interview. During the interview, participants were asked to show each picture they had taken and describe the waste it depicted. The interview guide was updated in an iterative process to probe for emerging themes, such as contributors to waste. Interviews were audio-taped and professionally transcribed. This study was approved by the Baystate Medical Center Institutional Review Board. Informed consent, including permission to keep the photos, was obtained from each participant.

Analysis

Applying grounded theory (36), transcripts of in-depth interviews were reviewed in an iterative process by SG and RK. SG performed open coding on the first four transcripts. Types of waste and recommendations to reduce waste were anticipated as broad themes based upon interview guide questions. RK then coded the same four transcripts independently, using the code book SG had developed. SG and RK then reviewed discrepancies in coding, resolving disagreements through discussion. Analysis proceeded in an iterative process with SG and RK performing open coding on each new transcript and resolving coding discrepancies through discussion. SG and RK performed independent coding on a total of four transcripts during the iterative process to assess inter-rater reliability. Notes (memos) about emerging concepts were made throughout analysis to track developing themes. Secondary coding (axial and selective) was performed by SG during the constant comparative process and secondary codes were refined through discussions with RK and MR. During secondary coding, four categories of waste emerged with associated sub-categories. Inductively and deductively derived recommendations for waste also emerged during this stage of coding. Inductively derived recommendations were inferred from comments about postulated contributors to waste while deductively derived recommendations were explicitly stated. After completion of secondary coding, SG performed theoretical coding with RK and MR. During this final stage of analysis, we compared our findings to existing frameworks for health care waste to arrive at the final themes. Although theoretical sampling (37) was not performed to challenge the theoretical framework, participants were recruited until no new concepts were introduced for four sequential interviews.

RESULTS

Of the 24 individuals invited to participate in this study, 3 declined. Participants took 159 photos; the number of photos taken ranged from 3–13 (median=8). The departments of internal medicine, pediatrics, anesthesiology, obstetrics and gynecology, radiology, emergency medicine, health care quality, respiratory therapy, pharmacy, and nursing were represented. Degrees held by participants included RN, MD, Bachelor’s, PharmD and RRT (respiratory therapy). Forty-three percent were women and the average number of years participants had spent in their field was 19.3 (SD=10.8) with 14.4 (SD=11.7) years at the study institution. Seventy-six percent had some form of administrative experience. Inter-rater agreement reached 85%.

Broad themes identified included types of waste and recommendations to reduce waste. Participants’ recommendations to reduce waste included both deductively and inductively derived elements. Broad themes, categories and sub-categories are described in detail below, along with illustrative quotes.

Types of Waste

Four major categories of waste were identified: Time, Materials, Energy and Talent, with sub-categories identified for Time and Materials. Time was the predominant category with 50% of photos depicting time wastage. (Table 1) Most participants (76%) provided examples from several categories of waste, while others provided multiple examples from a single category. Many of the categories and sub-categories identified overlapped with the sources of waste described by the IOM (e.g., “inefficiently delivered services”), LSS (e.g. “transporting”) and/or the IHI Inpatient Hospital Waste Toolkit (e.g. patient “flow delay”). (Table 1)

Table 1.

Categories of waste and their overlap with existing waste frameworks

| Waste Categories |

Number of Photos n/159 (%) |

Institute of Medicine |

Lean Six-Sigma |

Institute for Healthcare Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | 80 (50%) | |||

| Searching | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Waiting | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Transporting | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Excess Processing | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Materials | 68 (35%) | |||

| Overutilization | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Inventory | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Energy | 16 (10%) | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Talent | 6 (4%) | |||

Categories (bold) and sub-categories (italics) are described below. Categories of waste and contributing factors are shown in Table 2. Additional pictures with descriptive captions are provided in Appendix B.

Table 2.

Examples of waste and contributing factors with descriptive quotes

| Types of Waste | Contributing Factors | Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Time | ||

Searching

|

Separate cost centers/silos Staff inertia Lack of ownership Poor communication Poor inventory management Variation in resource needs False economies Poorly designed work space Lack of professionalism | “… if I can’t find a tongue blade in that room, and I have to come out, that’s inefficient. And, it would be so much more efficient, and less costly, for somebody who is ~ has a lower salary structure than the physician ~ to be able to go in, make sure all the rooms are stocked. So there's less of this Brownian movement trying to find supplies.” |

| “ - the nurse on the phone… it’s the amount of time spent trying to find out who’s covering, who is actually assigned to the patient, that is a huge deal. “ | ||

| “But, again, it also signifies ~ so every time we have a discharge, we have to go search for that wheelchair.” | ||

Waiting

|

Poor system design Inconsideration Outdated technology Poor communication | “This is a picture of the Kronos box and my favorite thing of all time regarding waste is people lined up waiting to swipe the Kronos box because if they swipe it too soon they don’t get credit for the full day. So it’s silly.” |

Transporting

|

False economies Understaffing | “He’s waiting for the elevator. Waiting was my sense of the wasted resource going on there.” |

| “We had a scale, it’s broken. It’s sent out to be fixed four months ago so we still haven’t gotten it back yet so we have to share with our sister floor… so it’s a big waste of time going back and forth to borrow it.” | ||

Excess processing

|

Regulations/policies Poor administrative coordination Inconsistencies in patient care practices | “Okay, we do a lot of, I think, unnecessary running here in the ICU, meaning every day we go down to the mailroom to pick up our mail. Every day, we do blood runs… .so ~ there's people being pulled away from their [nursing] jobs to walk to the other end of the hospital, and that just seems crazy to me.” |

| “Another one of my long-term interests is the volume of email. This morning, I received my ninth, ninth, full notice of tomorrow’s grand rounds and workshop. Nine. None of them came from my division; they all came in from the Department of Medicine. I think that’s crazy. So, I received so many notices of that grand rounds that it started to irritate me to the point where I don't want to go.” | ||

| Materials | ||

Excess utilization

|

Defensive medicine Reimbursement system Patient/referring MD expectations Medical education Lack of knowledge Lack of feedback Medical uncertainty Physician inertia Regulations/Policies Need to use new technology | “But the thing with task you hit one, the biophysical, and it leads you to ten other things under that one and then you have to into each system to hit all the things and document and there’s duplication because then you have Braden scale and then you have a pain scale. And all this is in the biophysical but it’s duplicate.” |

Inventory

|

Avoidance of missing supplies/hoarding Poor planning Variation in resource needs | “.. .you know, the sad thing is if we didn’t waste all this money [on unnecessary tests], we wouldn’t be in the dilemma we were in, in terms of health care cost. And this is not just the United States, this is - I mean, it's a problem all over, although we’re probably worse.” |

| “We had a British guy come to our place a few years ago and we talked a little bit about utilization of resources and he said, “Just amazing in the States. You take the youngest, most inexperienced doctors and let them order the most expensive things ad lib.” It’s true.” | ||

Energy

|

Separate Cost Centers/Silos Conservation not a priority | “So, this is really on us; this has to do with procedures that we do that in our hearts we know don’t need to be done, that are referred by other cardiologists and they want their patients earned because they think they need to be earned. So, I mean, you know, if it’s totally egregious,”“ |

Talent

|

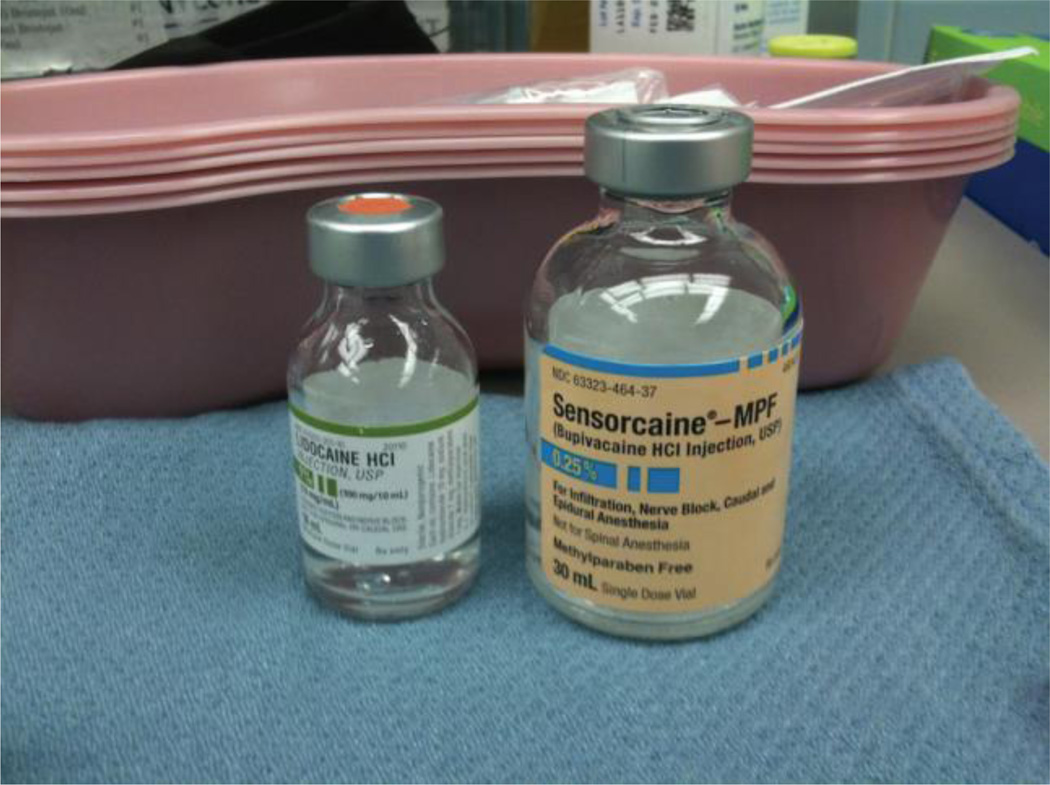

False economies Poor management Poor hiring practices | The first one here is a picture of two vials [10 and 30 cc with]… So, this is an instance of where we could use ~ several patients could receive drugs from, you know, one vial [but waste a lot have to use a new vial with each patient] We could have a solution maybe. A pharmacist draws up each 30cc into four or three lOcc, or six 5cc, or some combination thereof and we can use it, because we use standard amounts for most procedures” |

| “What’s happened is, as a result of not having an identified space that we could all see as a place to go and sit, is … every single person has their own refrigerator, and their own microwave, and their own toaster oven.” | ||

| “I can’t imagine these are efficient air conditioners in any way, shape or form, and they said there’s nothing they can do about them. This whole building has them. And they break all the time, but they said they have to fix them, because they can’t replace them.” | ||

| “with the process [of hiring have a tendency to take for granted our residents and not treat them as a customer… we don’t actively recruit them like we should. They’re applying to other places. And they -- they see the differences. And they feel insignificant when [another employer] is trying to hire them.” |

Time

A physician (internal medicine, hospitalist) described time as the most ubiquitous source of waste, and shared a picture of a clock when describing this source of waste:

“It’s time. It’s time. It’s our biggest wasted resource… our biggest waste of opportunity.”

Sub-categories of wasted time included time spent searching for needed items (e.g., materials, staff), waiting (e.g., for slow computers), transporting (e.g., materials, patients) or excess processing (e.g., duplicate e-mails, repetitive documentation). Participants identified numerous factors that they felt contributed to wasted time, including outdated technology, poorly designed work space, poor communication, false economies, lack of ownership of the problem, and cost center “silos”.

A nurse (internal medicine wards) offered an example of time she wasted searching for patient chairs. She explained that chairs were shared amongst all medical floors and managers had no incentive to buy new ones or repair broken ones:

“Fighting about chairs. It’s a resource… that we don’t have, but it’s also the time spent looking [for chairs]…I am wanting to get my patient…out of bed… and we have no place to put them. And I have no incentive…to buy them [chairs] because I can’t keep them [on my unit].”

The electronic medical record (EMR) was identified as a source of time wasted waiting by both nurses and physicians, (6% of photos) One physician (internal medicine, hospitalist) described the slow processing time of the EMR, while showing photo of the hourglass that appears on the computer screen while it is processing:

“….The EMR sometimes gets sluggish and slow …I’ve stared at the hour glass sometimes for as long as a minute…many times a day.”

Time wasted transporting patients or materials were identified by several nurses. Following a work re-design, nurses (internal medicine ward) found themselves not only wasting time transporting patients but also searching for wheelchairs to complete this task:

“ So when we had our reduction in workforce [transport services]… their solution was that discharges would…be handled by the nurses… I’ll have a wheelchair near my nursing station with a sign on it… “Please do not take, it is for discharge”…People take it.”

A number of participants expressed concern that time wasted searching, waiting and transporting resulted in less time for patient care. For example, while discussing time wasted due to duplicate documentation requirements (excess processing), a nurse (internal medicine wards) also expressed concern about the potential impact on patient care.

“So you are attached [to the computer], it’s taking you away from the patient. So you are with the patient less, which we don’t like.”

Materials

Over utilization of medical interventions (e.g., diagnostic lab tests, procedures and radiological tests) and excess inventory (e.g., excess food supplied at meetings) were two sub-categories of material waste. Examples of over utilization comprised 3% of photos. Factors identified as potential contributors to over utilization included defensive medicine, patient and referring physician expectations, medical education/trainees, and lack of physician knowledge. One physician (cardiologist) expressed strong negative feelings about the over-reliance on stress testing in the evaluation of chest pain:

“We do entirely too many stress tests plus doctors no longer know how to take a history…It's easier to order a test than to…take care of a patient, and…use your brain.”

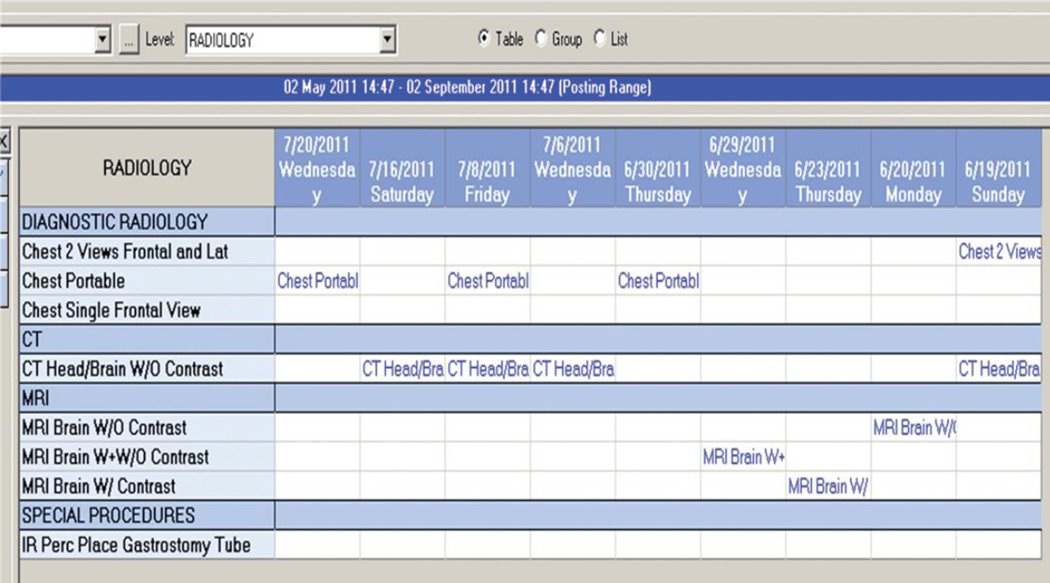

A sub-specialist in internal medicine felt that overuse of CT scans and MRIs contributes to waste, noting that one patient had 7 different head imaging studies done in a relatively short period of time.

An anesthesiologist cited the practice of discarding multi-dose medication vials after a single use because of infection prevention regulations as an example of excess inventory. Another example was a sterile procedure tray being stocked with rarely used items that were then discarded.

Excess inventory was hypothesized by participants to result from attempts to avoid wasting time searching for items needed during a procedure or from poor planning.

Energy

Eight participants (38%) offered 12 different examples of wasted energy. Some of the examples were similar to potential sources of wasted energy in homes, but on a larger scale; lights and appliances/computers left on when not in use, doors left open during heating and cooling seasons, thermostats set too high in winter and too low in summer, use of old/inefficient appliances and failure to use updated technology such as censored lights. One physician (OB-GYN) commented on energy wasted by lights left on all night.

“…I work on Thursday nights [in a large office building] and when I leave, lights are on, computers are on, the copier stays on. Everything stays on, all night long, every night…”

Another physician (oncologist) described amazement at how cold the hospital is kept in the summer and hypothesized that even small changes in thermostat settings could result in substantial savings.

“So I took a picture… of the thermostat… it was, like, 69 or 70 degrees… I think that we could probably save a fair amount…by having things be a little warmer in the summer and a little cooler in the winter… Could we save something by just making a degree difference?… I was walking from the hospital through the corridor over to [name of coldest hospital wing] and we could feel this cold breeze coming at you and I went, “Yep, it’s the differentials [between the two buildings]”… It’s amazing there wasn’t a tornado or something.”

Other sources of wasted energy described by participants were more specific to the health care setting: an O2 compressor left on all night while not in use, idling ambulances and use of large shuttle buses at times of day when they are essentially empty. Two participants commented on the use of large, largely empty shuttle buses. One (respiratory therapist) observed:

“And then… just the N-Lot bus; the huge buses… sometimes I come in for 11 [AM] and there’ll be two people [on] this huge bus.”

Lack of accountability and lack of awareness of the potential for savings were cited by participants as potential contributing factors to wasted energy.

Talent

Although less commonly reported than other sources of waste, 4 participants offered 6 examples of wasted talent and skill. These examples comprised three broad categories: being required to perform tasks below level of expertise, loss of good employees due to working conditions and failure to hire good candidates because of hiring practices. For example, a pharmacist felt the lack of a phone system that directs the caller to the right person pulled pharmacists away from their responsibilities to field calls that should have been handled by a technician, resulting in delays in patient care:

“We just have a general phone line, and everyone’s first instinct is “let me talk to the important person”. [the pharmacist]. When there's… four pharmacists… consistently doing orders, and …you constantly take them away, it delays order verification…”

While discussing concerns regarding nursing shortages and related additional responsibilities for nurses, a nurse in a management position expressed concern regarding loss of talented nurses because of the working conditions created by the shortages:

“…I have lost…two of…my best nurses…you have to go home… and know you did the best you could, but when doing the best you could sometimes leaves your nursing care so very wanting, you choose to leave [your job]…,and that’s what we’re seeing.”

Another example of wasted talent was a perceived failure to hire “good” internal trainees who were candidates for faculty positions because of recruitment strategies that were perceived to focus on external candidates. One administrator observed:

“So …our hospitalist hiring [process] has been less than adequate… there’s been a lot of unhappy people [residents] that have gone through and interviewed in… the past couple of years. And…who’ve not stayed because of their experience [with recruitment].”

Participants felt potential contributors to wasted talent included false economies, in which efforts to reduce costs by reducing staff resulted in other sources of waste. Misguided emphasis in hiring practices and poor system design were also considered to be contributors to wasted talent.

Participants’ recommendations to reduce waste

Responsibility for addressing waste lay at three organizational levels: micro-level (e.g., individual or ward), meso-level” (e.g. hospital or integrated health system) and macro-level (state or national government and/or insurance companies). Examples of both deductively and inductively derived recommendations made at each of these levels are described below.

Deductively derived recommendations

An example of a micro-level intervention was offered by a physician (OB-GYN) who was disturbed by the amount of energy wasted. She felt that if every person took small steps to conserve energy the savings would be substantial:

“… just… please turn the lights off when you’re done with the room…”

A meso- level recommendation made by a hospitalist was to provide all physicians and nurses in the hospital with cell phones, theorizing that text messaging could improve communication.

The few macro- level recommendations explicitly offered were general calls to “fix the health care system” with no detailed policy recommendations made.

Inductively derived recommendations

Although not explicitly offered as recommendations, participants’ comments about perceived contributors to waste suggested potential solutions. (Table 2) These inductively derived recommendations also fit the micro-, meso-, and/or macro- organizational levels.

Micro-level contributors included personal attributes such as “inconsideration”, “lack of professionalism”, “lack of knowledge”, “variation in clinical practices”, “staff and physician inertia” and “poor communication”.

Meso-level contributors to waste were the most commonly described among the three organizational levels and included elements such as “poor inventory management”, “poor space management”, “costs introduced by trainees’ inexperience”, “understaffing”, “outdated technology”, “poor coordination of administrative responsibilities”, “false economies” and “variation in resource needs”.

Macro-level contributors to waste included, “policies and regulations”, “defensive medicine”, “reimbursement structure” and “medical uncertainty”.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that health care workers’ perceptions of what constitutes waste may differ from the types of waste previously described. Sources of health care waste may be broadly categorized as operational or clinical in nature. (38) Participants in our study tended to describe operational sources of waste, such as workflow inefficiencies, more than clinical sources of waste such as excess utilization. Medical errors and fraud cited by the IOM as major sources of waste were not described at all. Participants also introduced two novel types of waste that have been less commonly discussed in reference to health care waste: energy and talent.

Our participants’ emphasis on operational sources of waste may be explained, in part, by reflexivity, which is inherent to the auto-photography methods used in this study. (28, 29) An example of reflexivity is how the participants’ employment status as health care workers may interact with their decisions of what to photograph and what not to photograph. (28, 29) For example, participants may have photographed examples of wasted time more often than problems related to over utilization because it may be more difficult, either consciously or sub-consciously, to call attention to waste you may personally contribute to. (28) The use of auto-photography may also have inhibited identification of more abstract forms of clinical waste because they are difficult to capture with still photography. One further potential explanation for the emphasis on organizational waste seen in our study was that some sources of waste may not have yet entered hospital workers’ consciousness because they are not readily apparent (e.g. price of services out of proportion to value). If the latter is true, this may support prior work calling for physicians to learn about waste in health care and to participate more fully in waste reduction efforts. (4)

The novel types of health care waste introduced in this study warrant further discussion. “Wasted talent” has not been commonly described in prior work on health care waste. However, this source of waste was described in the three contexts in our study: workers required to perform duties below their skill level, loss of “good” employees due to a perception of a sub-optimal work environment and failure to retain trainees because of ineffective hiring practices. Asking employees to perform duties below their skill level on a regular basis introduces inefficiencies and potentially job dissatisfaction (39) This may then lead to disengagement and reduced productivity (39, 40), which may then have a negative impact on patient care and patient satisfaction. (40) With health care reimbursement increasingly tied in part to patient satisfaction (41), this may have important financial ramifications. Employee turnover generates costs for recruitment and training of new employees (42), and may impact the morale or remaining employees (43), leading to disengagement. Further economic assessment of costs related to “wasted talent” may demonstrate a potential for cost-savings. A second novel type of waste discussed was “wasted energy”. Even though energy conservation has long been in the public consciousness, it is not commonly cited as a type of waste to be addressed in health care. Several participants in our study described wasted energy, such as lights left on and inappropriate thermostat settings, as a potential area for cost-savings for the health care system. Although no large scale efforts to reduce energy consumption in health care have been described, Practice Green Health is an organization devoted to reducing various sources of waste, including energy, in the health care industry. (44) Additionally, a recent study showed that working in a building specifically designed to reduce energy consumption led to greater conservation behaviors by people working in the building. (45)

The majority of participants’ recommendations to reduce waste required intervention at the micro- or meso- organizational level, which may be in part due to the enormity of macro-level issues in U.S. health care. Recommendations to reduce waste that may be most amenable to intervention included improving planning, reducing processing times on the current EMR, and organizing physical space to be more efficient. Contributors to waste that may be more challenging to address include workers’ attitudes, such as inertia, inconsideration and lack of ownership. Use of photo-elicitation may strengthen future interventions aimed at reducing waste, particularly when used in conjunction with methods such as process-mapping, because this method increases participant engagement and allows for a deeper understanding of their perspective. (34)

A number of recommendations to reduce the waste identified appeared feasible and relatively straightforward (e.g., as asking people to turn off lights and using text messages for communication between doctors). However, “fixing” many of the waste issues described in this study would be a complex undertaking, requiring re-engineering systems that have been in place for years and that often involve multiple stakeholders. Moreover, waste reduction efforts may generate other forms of waste. For example, if all potentially necessary items for a procedure tray were not pre-packaged as recommended by one study participant, time would be wasted searching for these items when they are needed. Although EMRs have demonstrated benefits, (46, 47), improving the EMR as suggested by participants in this study, would likely consume already strained information services resources. Replacing the EMR would require institutional dollars and substantial time investment by users to learn the new system. These findings highlight the importance of identifying potential challenges and proceeding with caution when intervening to reduce waste, precautions that have been previously advised. (48)

This study has limitations. First, auto-photography/photo-elicitation provided a unique method for identifying health care waste but may have restricted examples of waste identified to those items that were easily photographed, represented waste that was most frequently encountered or that were most personally intrusive. Second, this was a single center study, and examples of waste provided at other academic centers or community hospitals may differ. Third, although our purposive sample came from a broad range of departments with varying job descriptions, and we conducted interviews until no new concepts emerged, additional participants may have contributed novel concepts.

Despite decades of efforts to improve the value of health care in the U.S., systemic waste remains a daunting challenge. The feasibility and merit of the interventions recommended by participants in this study should be explored further to see if they may meaningfully impact waste, particularly at the micro- and meso-levels. This study also demonstrates the potential for using photo-elicitation to study other areas of health care, such as to explore patient satisfaction, or to illuminate the challenges that patients in special populations may encounter during interface with the health care system.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1.

Time as a wasted resource

Figure 2.

Excessive use of radiological imaging

Figure 3.

Single use vials waste medication.

Figure 4.

Turning off light switches may reduce wasted energy.

Figure 5.

Adjusting thermostats may reduce wasted energy.

What this paper adds.

What is already known on the subject

There is substantial waste in the US health care system. Economists and experts in the field have described a wide range of sources of waste and hypotheses as to how waste can be reduced.

What this study adds

This study describes waste from the perspective of hospital workers. Their perspective reveals a disconnect between experts and those working “on the front lines.” Novel sources of waste are identified by the workers as well as challenges to reducing waste.

Footnotes

This work was presented in poster form at the Pediatric Academic Society Meeting, Boston, MA, April 29, 2012, as an oral presentation at the Society for General Internal Medicine Meeting, Orlando, FL, May 11, 2012 and will be presented in poster form at the AcademyHealth Research Meeting June 2013.

All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: this project was supported by the National Center for Research Resources Grant Number KL2 RR025751 and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, Grant Number KL2 TR000074 (the content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH); all authors have no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years, and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Dr. Goff had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

The Corresponding Author has the right to grant on behalf of all authors and does grant on behalf of all authors, an exclusive licence on a worldwide basis to the BMJ Publishing Group Ltd. and its Licensees to permit this article (if accepted) to be published in BMJ editions and any other BMJPGL products and sublicenses to exploit all subsidiary rights, as set out in our licence (http://resources.bmj.com/bmj/authors/checklists-forms/licence-for-publication).

SG, MR and RK contributed to the study conception and design, SG, MR, RK and PL analysis and interpretation of data, SG, MR, RK and PL, drafting of the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and all gave final approval of the version to be published.

References

- 1.Kaiser Family Foundation. [Accessed September 5, 2012];Snapshots: Health Care Costs. http://www.kff.org/insurance/snapshot/index.cfm.

- 2.Cutler DM, McClellan M. Is technological change in medicine worth it? Health Affairs. 2001;20(5):11–29. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.5.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Monaco RM, Phelps HJ. Health care prices, the federal budget, and economic growth. Health Affairs. 1995;14(2):248–259. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.14.2.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brook RH. The Role of Physicians in Controlling Medical Care Costs and Reducing Waste. JAMA. 2011;306(6):650–651. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swensen SJ, Kaplan GS, Meyer GS, et al. Controlling health care costs by removing waste: what American doctors can do now. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20(6):534–537. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs.2010.049213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andriole GL, Crawford ED, Grubb RL, 3rd, PLCO Project Team et al. Mortality results from a randomized prostate-cancer screening trial. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(13):1310–1319. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fisher ES, Wennberg DE, Stukel TA, et al. The implications of regional variations in Medicare spending. Part 2: health outcomes and satisfaction with care. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(4):288–298. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-4-200302180-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fisher ES, Wennberg DE, Stukel TA, Gottlieb DJ, Lucas FL, Pinder EL. The implications of regional variations in Medicare spending. Part 1: the content, quality, and accessibility of care. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(4):273–287. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-4-200302180-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dorsey JL. The Health Maintenance Organization Act of 1973 (P.L 93-222) and Prepaid Group Practice Plan. Medical Care. 1975;13(1):1–9. doi: 10.1097/00005650-197501000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diagnosis Related Groups (DRGs) and the Medicare Program: Implications for Medical Technology. [Accessed September 5, 2012];NTIS order #PB84-111525. 1983 Jul; http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/ota/Ota_4/DATA/1983/8306.PDF.

- 11.IOM (Institute of Medicine) Best care at lower cost: The path to continuously learning health care in America. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Koning H, Verver JPS, van den Heuvel J, et al. Lean Six Sigma in Health Care. Journal for Health care Quality. 2006;28(2):4–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1945-1474.2006.tb00596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Resar RK, Griffin FA, Kabcenell A, et al. IHI Innovation Series white paper. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Institute for Health care Improvement; 2011. Hospital Inpatient Waste Identification Tool. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agency for Health Care Research and Quality. [Accessed September 5, 2012];Health Care Efficiency Measures. Identification, Categorization and Evaluation, Chapter 1. http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/efficiency/hcemch1.htm.

- 15.Premier, Inc. [Accessed July 25, 2012];New efficiency dashboard helps hospitals pinpoint, quantify savings opportunities. https://www.premierinc.com/about/news/12-apr/eo.jsp.

- 16.Martinez EA, Chavez-Valdez R, Holt NF, et al. Successful implementation of a perioperative glycemic control protocol in cardiac surgery: barrier analysis and intervention using lean six sigma. Anesthesiol Res Pract. 2011;2011:565–569. doi: 10.1155/2011/565069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barnas K. ThedaCare's business performance system: sustaining continuous daily improvement through hospital management in a lean environment. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2011;37(9):387–399. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(11)37049-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Piggott Z, Weldon E, Strome T, Chochinov A. Application of Lean principles to improve early cardiac care in the emergency department. CJEM. 2011;13(5):325–332. doi: 10.2310/8000.2011.110284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Niemeijer GC, Trip A, Ahaus KT, Does RJ, Wendt KW. Quality in trauma care: improving the discharge procedure of patients by means of Lean Six Sigma. J Trauma. 2010;69(3):614–618. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181e70f90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ng D, Vail G, Thomas S, Schmidt N. Applying the Lean principles of the Toyota Production System to reduce wait times in the emergency department. CJEM. 2010;12(1):50–57. doi: 10.1017/s1481803500012021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rutledge J, Xu M, Simpson J. Application of the Toyota Production System improves core laboratory operations. Am J Clin Pathol. 2010;133(1):24–31. doi: 10.1309/AJCPD1MSTIVZI0PZ. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aldarrab A. Application of Lean Six Sigma for patients presenting with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: the Hamilton health sciences experience. Health care Quarterly. 2006;9(1):56–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glasgow JM, Scott-Caziewell JR, Kaboli PJ. Guiding inpatient quality improvement: a systematic review of Lean and Six Sigma. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2010;36(12):533–540. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(10)36081-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nicolay CR, Purkayastha S, Greenhalgh A, et al. Systematic review of the application of quality improvement methodologies from the manufacturing industry to surgical health care. Br J Surg. 2012;99(3):324–335. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bahensky JA, Roe J, Bolton R. Lean six sigma—will it work for health care? J Healthc Inf Manag. 2005;19(1):39–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mannay D. Making the familiar strange: Can visual research methods render the familiar setting more perceptible? Qualitative Research. 2010;10(1):91–111. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ball MS, Smith GWH. Technologies of Realism? Ethnographic Use of Photography and Film in. In: Atkinson P, Coffey A, Delamont S, Lofland J, Lofland L, editors. Handbook of Ethnography. London: Sage; 2001. pp. 302–320. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taylor EW. Using still photography in making meaning of adult educators’ teaching beliefs. Studies in the Education of Adults. 2002;34(2):123–139. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Douglas KB. Seeing as well as hearing: Responses to the use of an alternate form of data representation in a study of students’ environmental perceptions; Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Association for the Study of Higher Education.1998. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parke B, Hunter KF, Strain LA, et al. Facilitators and barriers to safe emergency department transitions for community dwelling older people with dementia and their caregivers: A social ecological study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marck PB, Lang A, Macdonald M, et al. Safety in home care: A research protocol for studying medication management. Implement Sci. 2010;5:43. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Radley A, Taylor D. Images of recovery: a photo-elicitation study on the hospital ward. Qual Health Res. 2003 Jan;13(1):77–99. doi: 10.1177/1049732302239412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Crabtree BF, Miller WL, editors. Doing Qualitative Research. 2nd edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harper D. Talking about pictures: A case for photo elicitation. Visual Studies. 2002;17(1):13–26. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Becker HS. Photography and sociology. Studies in the Anthropology of Visual Communication1. 1974:3–26. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Strauss A, Corbin J, editors. Basics of Qualitative Research Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. Chicago: Aldine; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bentley TG, Effros RM, Palar K, Keeler EB. Waste in the U.S. Health care system: a conceptual framework. Milbank Q. 2008;86(4):629–659. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2008.00537.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gallup. Harter JK, Schmidt FL, Killham EA, et al. [Accessed September 5, 2012];Meta-Analysis: The Relationship Between Engagement at Work and Organizational Outcomes. http://www.gallup.com/consulting/126806/Q12-Meta-Analysis.aspx.

- 40.Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, et al. Hospital nurse staffing and patient mortality, nurse burnout, and job dissatisfaction. JAMA. 2002;288(16):1987–1993. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.16.1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Press I, Fullam F. Patient satisfaction in pay for performance programs. Qual Manag Health Care. 2011;20(2):110–115. doi: 10.1097/QMH.0b013e318213aed0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schloss EP, Flanagan DM, Culler CL, Wright AL. Some hidden costs of faculty turnover in clinical departments in one academic medical center. Acad Med. 2009;84(1):32–36. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181906dff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dean BS, Krenzelok EP. The cost of employee turnover to a regional poison information center. Vet Hum Toxicol. 1994;36(1):60–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Practice Green Health. [Accessed February 8, 2013]; Found at: http://practicegreenhealth.org/.

- 45.Wu DW, Digiacomo A, Kingstone A. A sustainable building promotes pro-environmental behavior: an observational study on food disposal. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e53856. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Abramson EL, Barrón Y, Quaresimo J, et al. Electronic prescribing within an electronic health record reduces ambulatory prescribing errors. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2011;37(10):470–478. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(11)37060-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Silow-Carroll S, Edwards JN, Rodin D. Using electronic health records to improve quality and efficiency: the experiences of leading hospitals. Issue Brief (Commonwealth Fund) 2012;17:1–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dixon-Woods M, McNicol S, Martin G. Ten challenges in improving quality in healthcare: lessons from the Health Foundation’s programme evaluations and relevant literature. BMJ Qual Saf. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.