Abstract

Objectives

Massachusetts (MA) public schools conduct mandated body-mass index (BMI) screening and until recently, communicated results in a letter to parents/caregivers, to encourage primary care visits and provide aggregate data to the state Department of Public Health. This study assessed the letter's readability and qualitatively explored parents’ responses to it.

Methods

Readability of the BMI letter was calculated. Audio-taped 1-h focus groups were conducted with parents/caregivers of 8- to 14-year-old obese (≥95th BMI-for-age percentile) children. A semistructured interview guide was used to elicit responses. Qualitative content analysis was conducted on transcripts to identify emergent themes.

Results

Readability analysis showed higher grade levels than recommended. Eight focus groups consisting of two to six parents each were conducted (n = 29); 83% were female, mean age 41 ± 9 years, and 65% self-identified as Hispanic/Latino. Key themes identified included usefulness of the BMI letter, concerns about utility of BMI for screening, concerns about impacting self-esteem, and failure to understand the letter.

Conclusions

The MA BMI letter may not have been achieving its desired goal with some parents. Practice implications: Emergent themes from this study could be used to test effectiveness of similar BMI letters nationwide and develop strategies to improve communication to parents.

Keywords: Body mass index screening, BMI, Patient–provider communication, Health literacy, Weight communication

1. Introduction

Nearly one-third of U.S. children are obese or overweight [1]. School-based obesity screening is one of many strategies recently employed to address this epidemic. As of 2010, 20 U.S. states required school-based body-mass index (BMI) or body composition screening; nine of these also required parental notification [2]. In 2009, Massachusetts (MA) mandated school-based BMI screening for students in grades 1, 4, 7, and 10, confidential reports to parents, and provision of aggregate screening data to the state Department of Public Health (DPH) [3]. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that schools evaluate the impact of screening programs on BMI and weight-related knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors among students and families [4]. However, there have been few studies of BMI screening programs’ effectiveness, and none, to the best of our knowledge, of the MA program [5–7]. Further, the MA Public Health Council recently voted to continue BMI screening but end the state's parent notification program, amid criticisms that notification led to bullying and increased costs for schools [8].

BMI screening parent notification programs have been critiqued for relying on BMI as a predictor of excess adiposity and future health risks [9]. A high BMI-for-age has been found to have a 70–80% sensitivity for identifying excess body fat and is a highly specific (95%) indicator, but this may vary among white, Black, and Asian children [9]. In addition, BMI performs better in identifying body fatness among obese children than in over-weight children [9]. BMI notification programs have also been criticized for a lack of evidence to show efficacy as an intervention for reducing childhood obesity [10,11] and the potential risk for disordered eating behaviors and heightened body dissatisfaction [10,12,13]. Examining research on parent and student reactions to BMI screening and notification programs can help elucidate future research needs in this area to improve communication strategies.

To be effective, letters reporting results of BMI screening must be readable by all parents, and therefore be targeted to those with limited literacy skills. There is a relative lack of data about how parents interpret BMI and BMI percentiles. In one study, color-coded BMI charts promoted comprehension among parents with low numeracy skills [14]. In California, where screening is mandated but parent notification is optional, only 12% of letter formats used statewide contain any explanation of BMI [15]. However, little research evaluates the efficacy of the letters in other states [10,11], with no prior studies in MA. Some research has found modest improvements in how parents assess their children's weight status [5,6] or in their intent to change children's diets or physical activity [7] as a result of receiving the BMI letter. More research is needed to understand how to clearly communicate BMI data to parents and their preferences for receiving this information. Such research can inform efforts to maximize these letters’ effectiveness in other states.

Effective BMI letters must also communicate key messages about children's weight to parents in an acceptable and respectful manner. Two U.S. surveys with parents of school-age children have focused on preferred terms used to describe children's excess weight. The majority of parents (51%) seeking care for their children in a general practice clinic said physicians should use the phrase gaining too much weight to describe their concerns, rather than overweight (26%), fat, obese, or too heavy [16]. In a larger online survey, parents rated the term weight most desirable, followed by unhealthy weight, high BMI, and weight problem [17]. Obese was among the terms rated least desirable [17]. Qualitative research is needed to understand parents’ language preferences in the context of the BMI letter in order to develop effective BMI messages.

The primary objective of this study was to qualitatively explore parents’ understanding of and responses to the MA BMI letter. We also explored specific potential barriers to effectiveness in two ways: we tested the readability of the MA BMI letter and the educational materials that accompany it, and we explored parents’ previous experiences with health care professionals discussing their child's weight.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

Parents of obese children (≥95th BMI-for-age percentile) 8–14 years of age who were enrolled in a community-based, family-centered pediatric weight management program between October 2011 and February 2012 were eligible for participation in this study. The pediatric weight management program was a referral-based program. Primary care providers referred children for a variety of reasons, including a parent bringing in a BMI letter from school. The decision-making process for seeking assistance was not assessed in this study.

The six-month weight management program met for 2 h on 12 alternating weeks and included sessions with a nutritionist, exercise specialist, and behavioral specialist. Families met for 1 h of interactive nutrition or behavioral education and support, followed by 1 h for parents and children to exercise separately. Parents were eligible for the study if they were comfortable speaking, reading, and understanding English and could attend a 1-h focus group during the second scheduled parent exercise time of the program. Parents of children enrolled in the weight management program were selected for this study because they were among the population of families that the BMI letter is intended to help. Their input was desired to improve the BMI letter's efficacy in reaching parents of obese children. It was not known whether participants were prompted to enroll in the program as a result of receiving a BMI letter.

During the program's preliminary information session, research staff distributed a one-page flyer describing this study and inviting parents to participate. Parents were then recruited by a research team member (LM) and research assistant during the first of the 12 weight management sessions. Eligible parents provided written informed consent and completed a demographic survey. Parents participated in the focus group during the second weight management session without their child present. Health literacy was measured using the Newest Vital Sign (NVS) [18]. Although the NVS was originally validated for individual oral administration, in this study it was modified for use in a group setting with a paper-based answer sheet [19]. This study was approved by the University of Massachusetts Amherst and Baystate Medical Center Institutional Review Boards.

2.2. Readability

Readability refers to the predicted difficulty of reading printed material based on its vocabulary, word length, and sentence length [20]. Five validated measures were used to assess readability of the BMI letter and the educational materials sent home with the letter: (1) the Flesch Reading Ease Scale [21], (2) Flesch–Kincaid Reading Grade Level [22], (3) Simplified Measure of Gobbledygook (SMOG) [23], (4) Gunning Frequency of Gobbledygook (FOG) [24], and (5) the Fry Readability Graph [25]. Educational materials provided with the BMI letter by the MA DPH included the following: (1) Help Your Kids Eat Healthy at Home, (2) Give Your Kids the Right Amount of Food, (3) Your Child Needs to Be Active Every Day, and (4) Frequently Asked Questions about Body Mass Index (BMI) Screening. Readability was assessed with these five formulas so that results of the different measures could be compared, as has been done previously [26].

All readability scores were calculated using published instructions from the original authors; this involved counting word and sentence lengths within a sample of each document. These formulas estimate readability from a combination of measures such as average sentence length, syllables per word, and polysyllabic words. All formulas produce reading grade-level estimates, with the exception of Flesch Reading Ease, which rates ease of reading from 0 to 100. The Flesch–Kincaid Reading Grade Level modifies the Flesch Reading Ease Scale to generate a grade level estimate. In addition, the SMOG provides a particularly useful grade level estimate at which 100% of readers can be expected to understand the text [23]. For more information about the use of readability measures, see Burke and Greenberg [27].

2.3. Focus groups

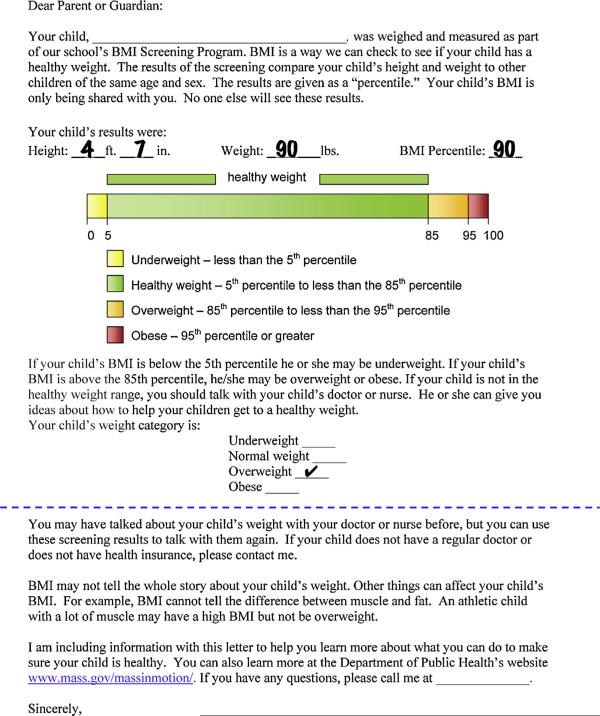

A semi-structured focus group guide was developed and pilot tested with two groups of low-income adults. Questions were designed to elicit responses to the MA BMI letter and recommendations for discussing a child's weight. A sample letter, which included height, weight, and BMI percentile results for a fictitious overweight child, was provided to prompt discussion (Fig. 1). This letter, developed by the MA DPH, contains a bar with segments colored yellow, green, yellow, and red to denote a child's weight as underweight, healthy weight, overweight, or obese, respectively (Fig. 1). Focus groups were led by one of the research team members (LM) with an assistant present to take field notes. New focus group sessions continued until saturation of major themes was observed [28], for a total of 29 participants. All sessions were audiotaped and professionally transcribed verbatim, with LM verifying the accuracy of the transcriptions separately. Content analysis of transcriptions and field notes was conducted in an iterative fashion to organize the text according to codes based on the original focus group guide and to identify emergent themes [29] and secondary findings. Content analysis was organized using NVivo 9 software (QSR International (Americas), Inc., Burlington, MA). LM was the primary reviewer of the qualitative data, and another member of the research team (EC) also reviewed data for consistency.

Fig. 1.

The MA BMI letter with information for a sample child.

3. Results

3.1. Readability

Grade-level estimates for the BMI letter and educational materials varied depending on the readability measure used (Table 3). The BMI letter scored at approximately a seventh-grade reading level using the Fry (7), FOG (7.5), and SMOG (7) formulas. However, the Flesch Reading Ease and Flesch–Kincaid formulas estimated the readability of the letter at grades 6 and 5.1, respectively. All but one of the educational materials (Give Your Kids the Right Amount of Food) had estimated reading levels higher than the recommended sixth grade maximum according to at least one readability measure (Table 3) [30].

Table 3.

Reading grade level estimates.

| Letter | “Eat Healthy” | “Right Amount” | “Be Active” | BMI FAQs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fry | 7 | 4 | 3 | 8/9 | 10 |

| FOG | 7.5 | 5.8 | 6 | 9.2 | 10.1 |

| SMOG | 7 | 7 | 6 | 9 | 8 |

| Flesch Reading Easea (grade level) | 84.5 (6) | 91.1 (5) | 94.6 (5) | 69.7 (8–9) | 71.9 (7) |

| Flesch–Kincaid | 5.1 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 6.8 | 7.5 |

Score classification and estimated reading grade level: 90–100 = very easy (fifth grade), 80–90 = easy (eighth grade), 70–80 = fairly easy (seventh grade), 60–70 = standard (eighth-ninth grade).

3.2. Demographics and health literacy

A total of 29 individuals took part in eight focus groups (Table 1), which was adequate to observe saturation of major themes [28]. The number of participants per group was two (for three groups), four (three groups), five (one group), or six (one group). Participants were predominantly female (83%) with a mean age of 41 ± 9 years. Additional demographic data are provided in Table 1. Fifteen participants (52%) reported having received some form of a BMI letter. NVS scores ranged from 1 to 6 (on a scale of 0–6); scores for 12 participants (41%) indicated less than adequate health literacy (Table 2).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants.

| N | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 24 | 82.8 |

| Male | 5 | 17.2 | |

| Age (years) | 18–29 | 3 | 10.3 |

| 30–39 | 12 | 41.4 | |

| 40–49 | 9 | 31.0 | |

| 50–59 | 4 | 13.8 | |

| >60 | 1 | 3.4 | |

| Number of childrena (through age 19) | 0 children | 1 | 3.7 |

| 1 child | 10 | 37.0 | |

| 2 children | 5 | 18.5 | |

| 3 children | 8 | 29.6 | |

| 4–6 children | 3 | 11.1 | |

| Ages of childrena (years) | <1–5 | 5 | 8.5 |

| 6–10 | 18 | 30.5 | |

| 11–15 | 31 | 52.5 | |

| 16–18 | 5 | 8.5 | |

| Ethnicity | Hispanic/Latino | 17 | 58.6 |

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 9 | 31.0 | |

| Did Not Respond | 3 | 10.3 | |

| Raceb | American Indian or Alaskan Native | 0 | 0 |

| Asian | 0 | 0 | |

| Black or African American | 10 | 33.3 | |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 0 | 0 | |

| White | 11 | 36.7 | |

| Did Not Respond | 9 | 30.0 | |

| Education level | Some High School | 5 | 17.2 |

| High School Graduate/GED | 11 | 37.9 | |

| Some College/Associate's | 10 | 34.5 | |

| Bachelor's Degree | 3 | 10.3 | |

| Language spoken most often at home | English | 23 | 79.3 |

| Spanish | 5 | 17.2 | |

| Did Not Respond | 1 | 3.4 |

Two participants indicated a number of children that was not consistent with the number of ages listed and were omitted from the data shown here.

One participant self-identified as Black/African American and White. All other participants selected only one category or did not answer the question.

Table 2.

Distribution of Newest Vital Sign scores.

| Category | Score | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| High likelihood (50% or more) of limited literacy (Score = 0–1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 5 | 17.2 | |

| Possibility of limited literacy (Score = 2–3) | 2 | 5 | 17.2 |

| 3 | 2 | 6.9 | |

| Adequate literacy (Score = 4–6) | 4 | 9 | 31.0 |

| 5 | 3 | 10.3 | |

| 6 | 5 | 17.2 |

3.3. Focus groups

3.3.1. Initial reactions to the BMI letter

Three major themes emerged related to parents' initial reactions to the MA BMI letter: (1) the letter did not provide new information; (2) the letter was acceptable and could be helpful; and (3) the validity of BMI as a measure of children's excess weight was questionable (Table 4). Eight participants viewed the letter as positive, and another 11 participants saw it as potentially harmful or not the school's responsibility. Parents who thought the letter was acceptable or helpful also believed it was good to be aware of potential weight-related concerns about their child's health, and felt the BMI notification policy was welcome compared to a lack of notification in previous generations. As one parent noted, “This is very positive, and I think everybody should get [the letter] and get screened . . . I'm just glad the school noticed and they're out there to help the kids with their weight.” Among parents who questioned the validity of BMI as a measure of children's excess weight, some focused on a paragraph in the letter regarding muscle mass. This read, “BMI may not tell the whole story about your child's weight . . . An athletic child with a lot of muscle may have a high BMI but not be overweight.” One participant said, “The one thing that I do like about this letter is that it does say that BMI cannot tell the difference between muscle and fat.” Others did not regard the BMI as a valid measure of obesity because it only included height and weight. These parents did not like the fact that a child's build and heredity was not taken into account. Rather than relying on BMI, a number of parents evaluated children's weight status by making informal comparisons to other adults and children they knew. One parent said, “I had some friends come to me and tell me, ‘Do you believe the doctor said my child is overweight?’ and their kid's next to mine . . . they're crazy, they're not overweight.”

Table 4.

Reactions to the BMI letter and BMI screening.

| Theme | Selected quotes |

|---|---|

| Initial reactions to the letter | |

| Provides no new information | Yeah, I mean I would look at it, but it's not telling me anything that I probably don't already know. |

| I've gotten something like this . . . I was kind of upset ‘cause I said,’ Who are these people?’ I take my kids to the doctor so I already know where they stand. | |

| Letter is helpful, acceptable | It's actually good that they do it because you get to see – back when you're younger they never did this so – you just get to see where they compare and where they should be. |

| [The letter] only encouraged me to move . . . I didn't have a problem with it. | |

| Questionable validity of BMI | The one thing that I do like about this letter is that it does say that BMI cannot tell the difference between muscle and fat. |

| They're not doing the water test, they're not doing the pinching and all that. They're just doing it by their formula weight – height – here's your index, you know? | |

| It depends – some have taller torso, some have smaller torsos, longer legs – whatever. Where do they come up with this stuff? | |

| Positive reactions to BMI screening | |

| Could be helpful, motivating | This is very positive, and I think everybody should get it and get screened . . . I'm just glad the school noticed and they're out there to help the kids with their weight. |

| Negative reactions to BMI screening | |

| Not a school's role | It really should be coming from a physician and not a nurse from a school. |

| Impact on child's self-esteem | The school nurses do . . . their little check-ups that they do in school, but they do them in groups. |

| When we get those BMIs from the school . . . I don't like the fact that my son gets to see that before I can look at it . . . they don't send it home in an envelope. |

3.3.2. Reactions to BMI screening in schools

Responding to the BMI letter prompted broader discussion of the BMI screening and notification that had been implemented in schools statewide. Parents voiced both positive and negative reactions to the BMI policy (Table 4). Positive reactions included the letter's potential to be helpful and motivate change, as discussed in some parents’ initial reactions. Conversely, some parents did not consider BMI screening and notification to be part of the school's role. As one parent said, “. . . it really should be coming from a physician and not a nurse from a school.”

Other themes reflected the potential negative impact of the BMI screening process and the letter itself on children's self-esteem. Not all parents were convinced that weight was measured in a sensitive manner to protect students from weight-related teasing. Further, state law that specified how to conduct the screening mandated “direct, confidential notification” in writing to parents or guardians; the associated guidelines from the MA DPH also specified that letters should not be sent home with students [3]. However, of the 15 focus group participants who reported having received a BMI letter, five said their child brought the BMI letter home from school. This study was not designed to assess the extent to which BMI screening practices adhere to DPH guidelines, but the experience of these parents lends support to their privacy concerns. One parent said, “When my son showed [the letter] to me [he said] Mom, I'm not this way am I?” Further, concerns about schools sending letters home with children to reduce costs—rather that mailing them as directed—was cited as one reason for ending the MA program [8]. Parents in the focus groups were also concerned about the screening process potentially resulting in weight-related teasing from peers. One participant voiced such concerns: “Kids are cruel and when you're getting up to the kids that are in the fourth, fifth grade they're smart, and if they know what this is and it's being circulated around then there's a problem.”

3.3.3. Understanding the letter's content

Two major themes regarding parents’ understanding of the BMI letter were identified: accurate understanding of the letter's recommendation (seek medical attention), and confusion about how to interpret the section presenting a child's weight status (Table 5). Parents generally recognized that the letter was asking them to seek medical attention for an overweight/obese child. However, not all parents realized that the sample child with a BMI in the overweight range was above a normal weight. For example, some erroneously believed that the area colored green to show the range for healthy weight represented the sample child because this green segment was prominent on the letter. In addition, some participants misinterpreted percentiles on the colored bar as pounds. Comparison of themes and NVS results showed that a majority (67%) of parents who expressed confusion about the letter or weight terminology received a low NVS score.

Table 5.

Understanding of the BMI letter.

| Themes | Selected quotes |

|---|---|

| Areas of understanding | |

| Request to seek medical attention | To see your son's pediatrician to hopefully get on the right track to get your son healthy or your child. |

| Basically see your doctor and see what you can do about it, what options your child has. | |

| Areas of confusion | |

| Interpreting the child's weight status | I have to read it a couple times before I actually knew how to understand the graph . . . Be more forward to it: |

| Your son falls right here. | |

| The green is healthy weight? But down here they question it as overweight. I think this child is fine. | |

| Think he has a healthy weight because it's green. | |

| It tells me that after 85 pounds and his height is going to be overweight and obviously after 95 pounds he's going to be obese or a percentage higher than that so my reaction to that is that there is definitely something wrong. | |

| [The colored bar shows that] it's a small percentage of kids that are either underweight or overweight. |

3.3.4. Recommendations for discussing weight

Because the purpose of the BMI letter was to encourage parents to talk with their health providers, this study also explored how parents would like providers to discuss their child's weight (Table 6). These conversations can help parents better understand reasons to take action and specific actions to take. Many parents who reported negative experiences said they did not like the words physicians used to discuss excess weight, such as obese or fat. Another participant described a doctor, who told her child he was “fat” for his age, stating “. . . and then the kid, he just looked down, sadly.” Throughout the focus groups, some participants indicated that they were drawing on their own prior experiences with communicating about personal weight struggles, which informed their preferences for discussing their children's weight. In addition to word choice, some parents also felt that physicians’ responses to weight concerns were inadequate—for example, saying the child would “grow out of it.”

Table 6.

Patient-provider weight communication.

| Theme | Selected quotes |

|---|---|

| Positive experiences | |

| Appropriate words used | My daughter's pediatrician, they use weight as a word, not obesity or fat, you know, weight, having weight issues and made her feel like a bigger part, saying that a majority of kids these days have weight issues: lower or higher. |

| They just said my daughter was gaining X amount of weight . . . They didn't say anything negative. They just said that they took her weight from previous years and then added it up to the next physical year. | |

| Helpful feedback and support | I don't think I ever had any negative, any kind of feedback is good feedback . . . just telling what kinds of foods to eat, the portion size, how often to eat, what time not to eat at. |

| My son ended up losing some weight and the doctor gave him a pat on the back. He said good and good job Mom. | |

| Addressed medical causes, consequences | I've had a good experience . . . they've been so polite with her . . . giving hope to her that she can lose weight and feel the way that she wants . . . for my granddaughter, that wasn't only what we were eating, was the new medication that she was taking increased her appetite and she gained weight, a lot of weight. |

| [The doctor] sent her to get a blood test and her sugar levels, they were too high. So it's a good thing she do that because the spots in her neck, she said it's not eczema, it's a sign of diabetes . . . I was so excited that she really figured that out. | |

| Negative experiences | |

| Inappropriate words used | The word that I don't like – it was used for me, but also for my kid – obese. I don't like that word, I really don't like that word. |

| They weighed [my child] and then the doctor told him, ‘Oh, for your age you're fat.’ . . . [The doctor was like] that's my way of making him understand that he needs to lose weight. | |

| Inadequate response to weight concerns | I had a concern with my son's previous pediatrician . . . and he said he'll grow out of it, he'll grow out of it – until recently, a couple of years ago, we changed the pediatrician and the first thing this new pediatrician said to us was the weight issue. |

Conversely, other parents said that any discussion of children's weight with health professionals was acceptable if it was motivated by concern for their child's health or risk for a health problem. Among those who reported positive interactions, they noted that providers used words deemed appropriate; provided helpful feedback and support; and adequately addressed possible medical issues related to their child's excess weight. One parent described use of appropriate words this way: “My daughter's pediatrician, they use weight as a word, not obesity or fat, you know, having weight issues . . . saying that a majority of kids these days have weight issues—lower or higher.” With regard to possible medical issues, individuals gave examples of productive encounters: a physician investigated the effects of a medication on their child's appetite, sent their child for a blood test to measure blood sugar levels and diabetes risk, or referred them to an endocrinologist.

3.3.5. Emotions

Although participants were not specifically questioned about their emotional reactions to the BMI letter, a wide range of emotions were expressed. Parents voiced feelings of denial, anger, rationalization, concern, guilt, fear, and acceptance (Table 7) in relation to discussions about their child's weight in general and to the MA BMI letter specifically.

Table 7.

Participants’ emotional reactions to their child's weight.

| Emotion | Context | Selected Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Concern | Health problems | I think it was the fact of having issues later on with his health . . . his heart was my main concern and my main reason why we kept on going to appointments. |

| Self-esteem | Kids are cruel and when you're getting up to the kids that are in the fourth, fifth grade they're smart, and if they know what this is and it's being circulated around then there's a problem. | |

| Provider sensitivity | Don't single them out. Don't make him feel like he has a problem, a big – a disease – you know? | |

| Guilt | Parent's role | You take most of the blame because you're like I'm the mother and I can't believe that I didn't pick healthy choices. |

| Did I do enough? You beat yourself up and the kids notice that too. | ||

| Fear | Child's reaction | [My son] heard things, not necessarily what the pediatrician said, but what he took away from it was – you're doing everything wrong – and his instant reaction was to just stop eating, which scared me. |

| Scary words | [Extremely obese is] scary, yeah that's scary. | |

| Upset | Offensive words | I hate [the word obese], I do. |

| Provider response | The only time [my daughter's pediatrician] talks about [weight] is on her physical when she shows me the growth on charts, compares age and weight, the BMIs and all that. | |

| Receipt of letter | I've gotten something like this [letter] . . . I was kind of upset ‘cause I said, ‘Who are these people?’ I take my kids to the doctor so I already know where they stand. | |

| School's role | This should not be coming from the school system. | |

| Rationalization | Muscle mass | Because a kid with muscle is not obese. |

| Heredity | Some people just don't thin out like that or some people just stay big or they have bigger bones. | |

| Obesity prevalence | The doctor should not be critical and they should be understanding because it's a world problem that we have, it's not just us here. | |

| Medical conditions | Let's think about something called thyroids, different metabolism inside the body, which might multiply their growth. | |

| Skepticism | Validity of BMI | They're not doing the water test, they're not doing the pinching and all that. |

| Acceptance | Focus on health | I think instead of saying, ‘We're going to give you a referral to the obesity clinic,’ they should say, ‘We're going to give you a referral to someone that's going to help you eat healthier and live a healthier life and show you ways to be more active.’ |

| Provider feedback | I don't think I ever had any negative, any kind of feedback is good feedback . . . just telling what kinds of foods to eat, the portion size, how often to eat, what time not to eat at. | |

| School's role | This is very positive, and I think everybody should get it and get screened. | |

| Information in letter | [The letter] only encouraged me to move. I didn't have a problem with it. |

4. Discussion and conclusions

4.1. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that explored the readability of a BMI letter sent to parents from schools and parents’ responses to the letter. Our study revealed that some of the educational materials accompanying the BMI letter are written at a higher than recommended reading level for parents with low literacy skills. We also found that parents had mixed reactions to the BMI letter, with some feeling it was useful and others feeling the school should not be responsible for assessing BMI. The BMI letter recommends that parents talk with their doctor or nurse if their child is not in the healthy weight range, but parents’ prior experiences discussing weight with health care providers demonstrated potential barriers to this action. Finally, we found that discussions about the BMI letter and weight in general were associated with numerous emotional responses.

4.1.1. Comprehension

Our study suggests that some parents may have struggled to understand the BMI letter. In the current study, the lower health literacy scores of some participants and higher than recommended readability of the BMI letter and some materials may in part explain these findings. The estimated reading level was as high as 10th grade for educational information to accompany the BMI letter, and the BMI letter itself scored at or above a seventh-grade reading level on most measures. Discrepancies found among the different measures may be explained in part by the Flesch–Kincaid underestimating the reading level of written materials by approximately two grades [27]. In general, participants who voiced confusion about the BMI letter or weight terminology had low NVS scores, which indicated a possibility or high likelihood of limited health literacy. These findings suggest that the BMI letter and many of the educational materials did not meet a reasonable standard for “easily understood” guidelines proffered by DPH [3]. Because the MA BMI letter was written for a higher reading grade level than recommended, it is plausible that similar readability issues contributed to the limited effectiveness of other BMI letters reported in prior research [31]. States with parent notification programs should assess whether modifying their BMI letters may make their messages more accessible to parents with lower literacy skills.

4.1.2. Responses to the letter

Whereas eight participants viewed the letter as positive, another 11 participants saw it as potentially harmful or not the school's responsibility. Existing research is mixed on questions of whether BMI letters change parents’ perceptions of their child's weight and affect their behaviors or intention to change behaviors [6,7,32,33]. Quasi-experimental research to date, limited to two studies, suggests that BMI letters may result in more accurate perceptions of children's weight by parents [5] but not affect BMI z-scores at two years’ follow-up [31]. The lack of research to demonstrate efficacy makes decision-making related to BMI screening and notification policies complex [4].

Participants offered a number of suggestions about how schools could effectively communicate weight information to reduce potential negative effects on children's self-esteem. Many participants said they would consider the letter acceptable if mailed to them directly, as was recommended by the MA DPH. In MA, schools were required to notify parents in advance to provide the opportunity to opt out of the BMI screening process. Previous research in other states supports the consensus that parents prefer results not be shared with students in schools and that communication be done via mail [7,33–35], which may also be more effective in prompting caregivers to read the letter than sending the letter home from school with a child [36]. Failure to send BMI letters home via mail was cited as one reason that MA voted to end its program [8].

Many questioned the validity of BMI as a measure of excess weight because of how BMI limitations were presented in the BMI letter. This finding suggests that further research regarding the optimal presentation of language that describes the limited utility of BMI (e.g., “BMI does not distinguish between muscle and fat”), and potential health risks associated with a high BMI, is warranted to inform the wording of these letters. This finding was also consistent with others’ critiques of BMI as an acceptable measure of obesity [9–13].

Participants expressed consistent preferences for language used in written and verbal communication about their child's weight. Parents want health professionals to be positive and sensitive with their children, and to explain concepts in ways they (both parents and children) could understand. Parents also described preferences for how health care providers discuss weight, both in terms of how words are used and the issue is framed. They indicated a preference for objective and depersonalized words, such as weight rather than obese. The latter term was viewed as insulting and stigmatizing, which is consistent with previous research [17]. It is noteworthy that the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends use of the terms overweight and obese for “documentation and risk assessment,” as opposed to use during actual patient encounters [37]. Yet, these two terms appear to have been universally adopted for communicating above-normal weight status to families in schools’ BMI screening programs. Parents also preferred that weight issues be framed in the context of existing health problems or risk for future health problems, which could be addressed with weight management and healthy lifestyle changes. These findings are consistent with prior studies of patients’ and parents’ preferences for how health care providers discuss their own weight [38–40] and their child's weight [16,17].

Parents’ emotional reactions to their children's excess weight found in this study are consistent with literature on stigma associated with obesity. Among 10 words commonly used to describe children's weight, parents in a national online survey rated chubby, obese, extremely obese, and fat as most stigmatizing and blaming [17]. Parents’ emotional responses can also be compared to individuals’ emotional reactions to diagnosis of a chronic illness. For example, in recent semi-structured interviews of 34 primarily low-income, ethnically diverse patients with diabetes, emotional responses to diagnosis were categorized according to Kübler-Ross’ stages of grief [41]. Patients expressed denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance in response to diabetes [41]. Some similar emotional themes – denial, anger, rationalization, being upset, and acceptance – were identified among parents in this study. Parents may respond with these emotions when their child is “diagnosed” with overweight or obesity in school screenings. This framework of emotions could help explain parents’ reactions to BMI letters, specific weight terminology, and patient–provider communications, and should be tested in future studies.

4.1.3. Limitations

Several limitations of the current study merit discussion. First, the study population was made up of a small group of parents of obese children who were motivated to help their children lose weight, as evidenced by enrollment in an intensive pediatric weight management program. Further, parents in the study were already aware their child was obese when they read the sample BMI letter during the focus group. This may limit generalizability of our findings. Second, we collected no information about parents’ weight history or their own personal experiences communicating with physicians. While we observed throughout the focus groups that participants’ prior experience communicating about their own weight may have informed their reactions and preferences regarding their children's weight, we could not formally assess this association. Third, we did not collect data on reasons for participation or nonparticipation. It was not known whether individuals with particularly strong views for or against BMI screening volunteered to participate in this study, but many discussions included a mix of positive and negative reactions, suggesting that a range of opinions were represented. Fourth, because the focus groups were not offered in Spanish, some parents could not participate and others speaking English as a second language may not have been able to contribute fully to the discussion. Finally, it should be emphasized that the objective of this study was to qualitatively explore parents’ understanding of and responses to the letter. Some of these responses involved preferences about language and ways that information is communicated. However, preferences may be different from triggers to action. For example, some parents were more comfortable with phrases that normalized their child's weight (“saying that a majority of kids these days have weight issues”), but such phrases may not be the most effective in prompting the parents to take action.

4.2. Conclusions

This study found that the estimated readability of the MA BMI letter and some of the educational materials sent home with the letter was higher than recommended for parents with lower literacy skills. For many focus group participants, the BMI letter prompted them to question the validity of BMI to identify children with excess weight. Responses to the letter and screening in general included their potential to be helpful and motivate change; being outside of the school's accepted role; and the potential negative impact on children's self-esteem. When communicating about weight, parents wanted health care providers to use respectful weight-related terms and emphasize the health-related context of a child's excess weight. Across the qualitative results, a range of strong emotions–from concern, fear, and anger to acceptance–were observed. The framework of emotions may help explain parents’ reactions to BMI letters nationwide in future research and may have broader implications for designing effective messages about childhood obesity.

4.3. Practice implications

These findings suggest that further impact assessments of state BMI screening programs may be warranted and offer suggestions for health providers as they talk about children's weight with parents. States with BMI screening and parent notification programs should assess whether modifying BMI letters and associated educational materials may improve readability and acceptability. In particular, graphic formats to enhance interpretation of children's weight status and BMI-for-age percentiles may be helpful. The overarching theme of parents’ emotional reactions to children's weight should also inform approaches to BMI notification. Among these emotional reactions, the area of strongest consensus was concern for children's self-esteem. This finding suggests school districts should design BMI screening and notification programs that fully ensure confidentiality – including mailing results to parents at home – and communicate these practices to parents. Three additional themes can inform the development of more acceptable BMI messages: the tendency to rationalize children's excess weight or question validity of BMI, the preference for discussing children's weight in the context of health, and the greater acceptance of objective, depersonalized words (e.g., weight), rather than terms considered offensive (e.g., obese). These results suggest that both BMI letters and patient–provider interactions may be better accepted when they focus on health promotion and more clearly explain the benefits and drawbacks of using BMI as a measure of weight. Still, studies are needed to see whether the most preferred approaches are also the most effective.

I confirm all patient/personal identifiers have been removed or disguised so the patient/person(s) described are not identifiable and cannot be identified through the details of the story.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Brenda Peters, Hilary Weiner, and Kara Swain for their assistance in facilitating this research project. This project was funded by a Baystate Medical Center/UMass Amherst Collaborative Biomedical Research Program grant. Dr. Goff's time spent on the project was also supported by the National Center for Research Resources Grant Number KL2 RR025751 and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, Grant Number KL2 TR000074. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

References

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity and trends in body mass index among US children and adolescents, 1999–2010. J Amer Med Assoc. 2012;307:483–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Linchey J, Madsen KA. State requirements and recommendations for school-based screenings for body mass index or body composition, 2010. Prev Chronic Dis. 2011;8:A101. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Massachusetts Department of Public Health [08.05.13];BMI screening guidelines for schools. 2009 http://www.mass.gov/eohhs/docs/dph/com-health/school/bmi-screening-guidelines-for-schools.pdf.

- 4.Nihiser AJ, Lee SM, Wechsler H, McKenna M, Odom E, Reinold C, et al. Body mass index measurement in schools. J Sch Health. 2007;77:651–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2007.00249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chomitz VR, Collins J, Kim J, Kramer E, McGowan R. Promoting healthy weight among elementary school children via a health report card approach. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157:765–72. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.8.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.West DS, Raczynski JM, Phillips MM, Bursac Z, Heath Gauss C, Montgomery BEE. Parental recognition of overweight in school-age children. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:630–6. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harris CV, Neal WA. Assessing BMI in West Virginia schools: parent perspectives and the influence of context. Pediatrics. 2009;124:S63–72. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-3586I. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lazar K. [16.10.13];Massachusetts scraps controversial student obesity letters. 2013 Boston.com http://www.boston.com/lifestyle/health/2013/10/16/massachusetts-scraps-controversial-student-obesity-letters/7A35q2d552eSMViKYAfiEJ/story.html.

- 9.Freedman DS, Sherry B. The validity of BMI as an indicator of body fatness and risk among children. Pediatrics. 2009;124:S23–34. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-3586E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cogan JC, Smith JP, Maine MD. The risks of a quick fix: A case against mandatory body mass index reporting laws. Eat Disord. 2008;16:2–13. doi: 10.1080/10640260701771664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soto C, White JH. School health initiatives and childhood obesity: BMI screening and reporting. Policy Polit Nurs Pract. 2010;11:108–14. doi: 10.1177/1527154410374218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ikeda JP, Crawford PB, Woodward-Lopez G. BMI screening in schools: helpful or harmful. Health Educ Res. 2006;21:761–9. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Portilla MG. Body mass index reporting through the school system: potential harm. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011;111:442–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2010.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oettinger M, Finkle J, Esserman D. Color-coding improves parental understanding of body mass index charting. Acad Pediatr. 2009;9:330–8. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2009.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Madsen KA, Linchey J. School-based BMI and body composition screening and parent notification in California: methods and messages. J Sch Health. 2012;82:294–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2012.00700.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eneli IU, Kalogiros ID, McDonald KA, Todem D. Parental preferences on addressing weight-related issues in children. Clin Pediatr. 2007;46:612–8. doi: 10.1177/0009922807299941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Puhl RM, Peterson JL, Leudicke J. Parental perceptions of weight terminology that providers use with youth. Pediatrics. 2011;128:e786–93. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weiss BD, Mays MZ, Martz W, Castro KM, DeWalt DA, Pignone MP, et al. Quick assessment of literacy in primary care: the Newest Vital Sign. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3:514–22. doi: 10.1370/afm.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Welch VL, VanGeest JB, Caskey R. Time, costs, and clinical utilization of screening for health literacy: a case study using the Newest Vital Sign (NVS) instrument. J Am Board Fam Med. 2011;24:281–9. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2011.03.100212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Friedman DB, Hoffman-Goetz L. A systematic review of readability and comprehension instruments used for print and web-based cancer information. Health Educ Behav. 2006;33:352–73. doi: 10.1177/1090198105277329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flesch R. A new readability yardstick. J Appl Psychol. 1948;32:221–33. doi: 10.1037/h0057532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kincaid PJ, Fishburne RP, Rogers RL, Chissom BS. Research Branch Report 8-75. Naval Air Station Memphis; Millington, TN: 1975. [24.01.12]. Derivation of new readability formulas (automated readability index, fog count, and Flesch Reading Ease formula) for Navy enlisted personnel. Available from: http://digital-collections.lib.ucf.edu/u?/IST,26253. [Google Scholar]

- 23.McLaughlin GH. SMOG grading—a new readability formula. J Read. 1969;12:639–46. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gunning R. The technique of clear writing. McGraw-Hill; New York City: 1952. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fry E. A readability formula that saves time. J Read. 1968;11:513–6. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Agarwal N, Hansberry DR, Sabourin V, Tomei KL, Prestigiacomo CJ. A comparative analysis of the quality of patient education materials from medical specialties. J Amer Med Assoc Intern Med. 2013 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.6060. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burke V, Greenberg D. Determining readability: how to select and apply easy-to-use readability formulas to assess the difficulty of adult literacy materials. Adult Basic Educ Lit J. 2010;4:34–42. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patton MQ. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. 3rd ed. Sage Publications, Inc.; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15:1277–88. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Doak CC, Doak LG, Root JH. Teaching patients with low literacy skills. 2nd ed. J.B. Lippincott Company; Philadelphia, PA: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Madsen KA. School-based body mass index screening and parent notification: A statewide natural experiment. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165:987–92. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnson SB, Pilkington LL, Lamb C, He J, Deeb LC. Parent reactions to a school-based body mass index screening program. J Sch Health. 2009;79:216–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2009.00401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kubik MY, Fulkerson JA, Story M, Rieland G. Parents of elementary school students weigh in on height, weight, and body mass index screening at school. J Sch Health. 2006;76:496–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2006.00147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murphy M, Polivka B. Parental perceptions of the schools’ role in addressing childhood obesity. J Sch Nurs. 2007;23:40–6. doi: 10.1177/10598405070230010701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stalter AM, Kaylor M, Steinke JD, Barker RM. Parental perceptions of the rural school's role in addressing childhood obesity. J Sch Nurs. 2011;27:70–81. doi: 10.1177/1059840510394189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaczmarski JM, DeBate RD, Marhefka SL, Daley EM. State-mandated school-based BMI screening and parent notification: a descriptive case study. Health Promot Pract. 2011;12:797–801. doi: 10.1177/1524839911419289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barlow SE. Expert Committee Expert committee recommendations regarding the prevention, assessment, and treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity: summary report. Pediatrics. 2007;120:S164–92. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2329C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dutton GR, Tan F, Perri MG, Stine CC, Dancer-Brown M, Goble M, et al. What words should we use when discussing excess weight. J Am Board Fam Med. 2010;23:606–63. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2010.05.100024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wadden TA, Didie E. What's in a name? Patients’ preferred terms for describing obesity. Obes Res. 2003;11:1140–6. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Volger S, Vetter ML, Dougherty M, Panigrahi E, Egner R, Webb V, et al. Patients’ preferred terms for describing their excess weight: discussing obesity in clinical practice. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2012;20:147–50. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kahn LS, Vest BM, Karl R, Tumiel-Berhalter L, Taylor R, Schuster RC, et al. Living with diabetes on Buffalo, New York's culturally diverse West Side. Chronic Ill. 2013;9:43–56. doi: 10.1177/1742395312450895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]