Abstract

Hepatic splenosis, one type of manifestation of ectopic spleen tissue, is rarely reported. It cannot be distinguished from hepatic malignancies because of lack of significant radiological features. By means of this case report and 31 literature reviews, potential treatment modalities concerning clinical diagnostics, patient's management could be discussed.

The report presents the case of a 33-year-old man with a liver lesion. Finally, after a mini-incision laparotomy, the lesion was resected and the diagnosis confirmed it as hepatic splenosis. A literature search for case reports published between January 1, 1900, and August 1, 2014, was performed on PubMed.

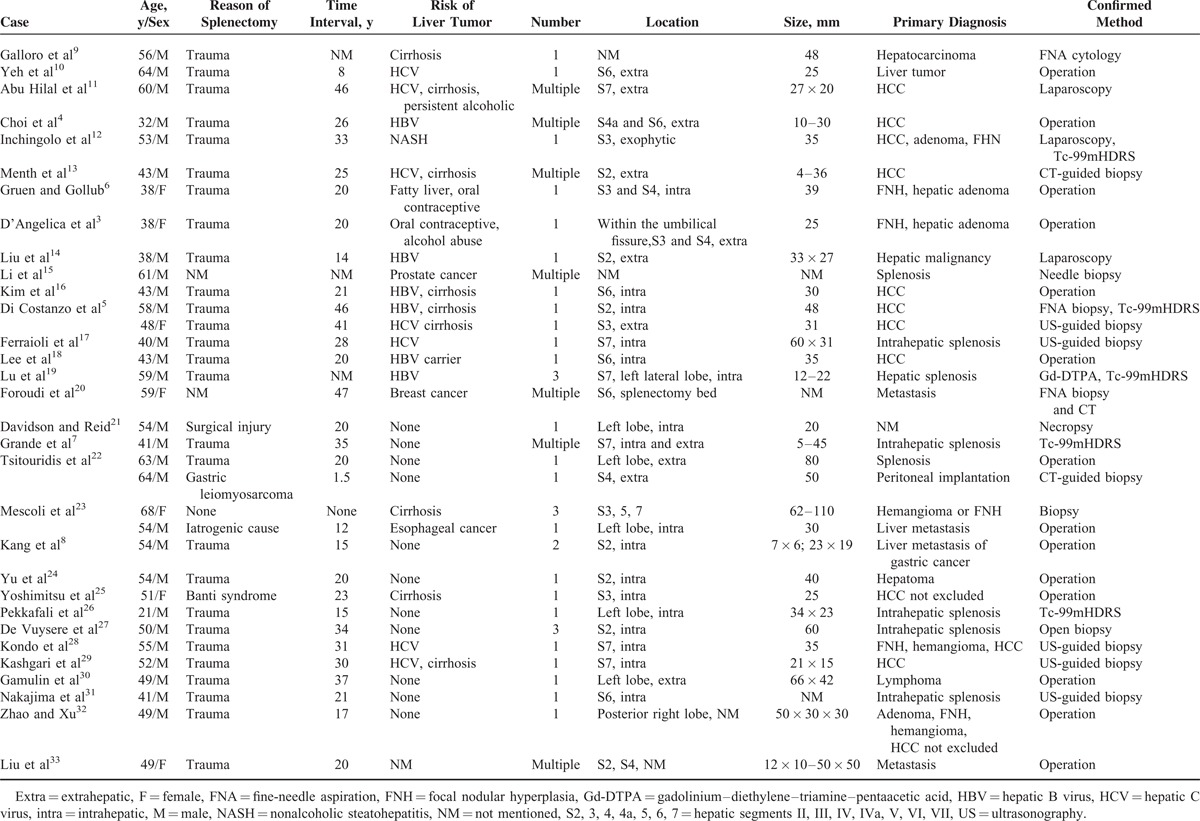

Approximately 80% (27/34) of patients diagnosed with hepatic splenosis had a history of splenectomy. The mean time interval between splenectomy and hepatic splenosis detection was 25 (1.5–47) years. The median size of reported hepatic splenosis is 30 mm in diameter. Technetium-99m-labeled heat denatured red-blood-cells scintigraphy or superparamagnetic iron oxide-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging is now considered to be the optimal method of diagnosing splenosis.

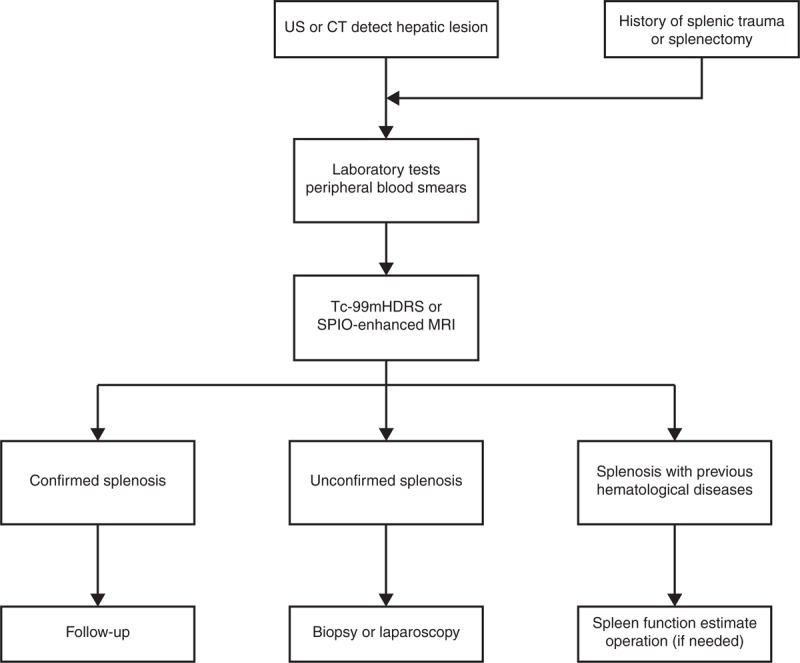

Hepatic splenosis requires no treatment in most cases. Operation should be performed if it is accompanied by hypersplenism in hematological diseases. When the diagnosis remains unclear, further biopsy or laparoscopy is recommended. If hepatic splenosis is confirmed, careful follow-up is beneficial.

INTRODUCTION

Splenosis is one manifestation of ectopic spleen tissue, which usually occurs after splenic trauma or splenectomy. The pathogenesis is possibly the autotransplantation of spleen fragment. It is mostly found in the peritoneal, pelvic, or thoracic cavity. However, hepatic splenosis, especially solitary perihepatic splenosis mimicking liver lesion, was rarely reported in the literature. With the deficiency of significant features, normal radiological examination cannot distinguish this from hepatic malignancies. Here, we report a patient with hepatic splenosis mimicking liver lesion. Literatures were reviewed and analyzed to provide information for clinicians to distinguish and treat this disease. Ethical approval was neither obliged nor sought because all management strategies and treatment procedures were part of routine health care. However, we have obtained the approval from the patient to report the case.

CASE PRESENTATION

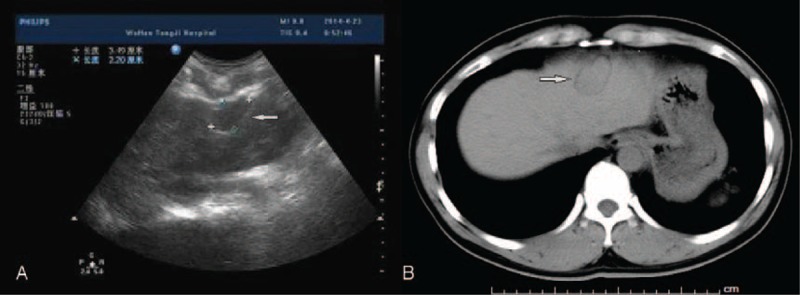

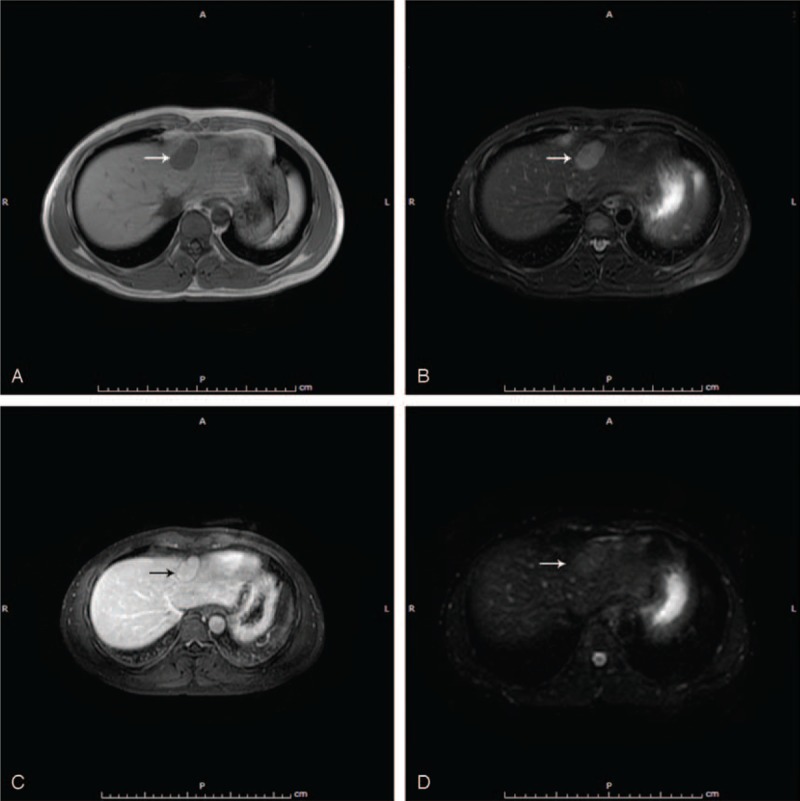

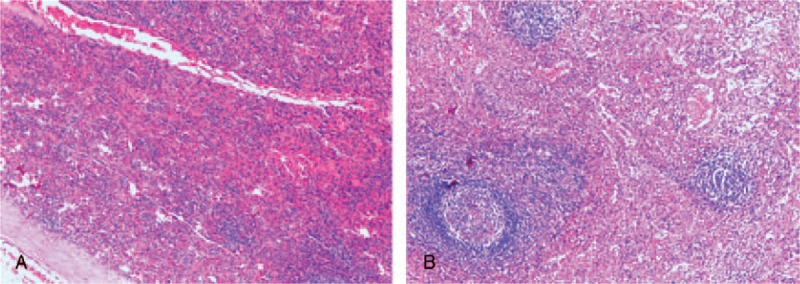

A 33-year-old man presented to our hospital after detection of a hepatic lesion from a routine examination. He claimed no discomfort. His medical history included an urgent splenectomy due to traumatic rupture of spleen from a traffic accident 12 years ago and hepatitis A virus (HAV) infection in childhood. No family or genetic history was found. There was no positive sign on physical examination except a previous operation scar. Blood routine and liver–renal function laboratory tests remained normal except mild elevated platelet count 372 ×109/L (normal range: 100–300 ×109/L) and total bilirubin 21.5 μmol/L (normal range: 3.4–20.5 μmol/L). The Child–Pugh grade was A (score 5). Besides tumor markers including α-fetoprotein, carcinoembryonic antigen, and carbohydrate antigen 19-9, HAV immunoglobulin M and hepatitis B virus (HBV) deoxyribonucleic acid were unremarkable. Abdominal ultrasonography revealed a 3.5 × 2.2 cm diameter hypoechoic lesion in the left hepatic lobe near diaphragm (Figure 1A). Electrocardiogram and chest radiography were normal. Plain computed tomography (CT) scan demonstrated a homogeneous hypodensity mass relative to the surrounding liver parenchyma, measuring 2.1 × 3.4 cm in diameter (Figure 1B). MRI with perfusion-weighted and diffusion-weighted imaging confirmed the presence of a solitary 3.5 × 2.0 cm lesion, which suggests hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), lying in segment II in a subcapsular position according to radiological features (Figure 2). Biopsy was recommended to the patient for clear diagnosis. However, being afraid of liver malignancy, the patient wanted to confirm the status of the lesion and chose surgery. With sufficient preoperative preparation, the patient underwent an exploratory surgery. Consulting with the previous operational adhesion, we performed the mini-incision laparotomy. Exploration showed that an extrahepatic 4 × 2 × 2 cm splenosis between liver segment II and diaphragm, and dent on the surface of liver could be seen. Intraoperative ultrasound was performed and excluded any other mass on the liver. Then the lesion was rapidly resected with no need of hepatic resection. The histopathological result confirmed the lesion as spleen tissue, with no indication of neoplasia (Figure 3). After 7 days recovery, the patient was discharged without complications. Follow-up examination including blood routine, liver function, and liver CT scanning at 30 days did not show any abnormality. No adverse or unanticipated event was presented.

Figure 1.

(A) Ultrasonography indicates a 3.5 × 2.2 cm diameter hypoechoic lesion, which envelope is integrated (white arrow). (B) Plain CT scan demonstrated a homogeneous hypodensity mass relative to the surrounding liver parenchyma, measuring 2.1 × 3.4 cm in diameter (white arrow). CT = computed tomography.

Figure 2.

(A) T1-weighted MR image: the lesion is of low signal intensity (white arrow). (B) T2-weighted MR image: the lesion is of high signal intensity (white arrow). (C) Liver acceleration volume acquisition contrast: the lesion is of slight hypointensity (black arrow). (D) DWI: the lesion is of slight hyperintensity (white arrow). DWI = diffusion-weighted imaging, MR = magnetic resonance.

Figure 3.

(A) Pathological result (hematoxylin–eosin staining, original magnification: 10×). (B) Pathological result (hematoxylin–eosin staining, original magnification: 40×).

DISCUSSION

Albrecht1 firstly described this disease in 1896, but till 1939, Buchbinder and Lipkopff2 introduced the term “splenosis.” Splenosis was once considered to be rare because of its asymptomatic clinical features. Recent articles3,4 show that incidence of splenosis varies from 26% to 67% in patients with traumatic splenic rupture. However, the accurate rate is unknown on account of no epidemiologic survey. Among the patients with splenosis, most have been performed splenectomy due to trauma or hematological diseases. Herein, the authors have searched literatures related to hepatic splenosis. All results can be seen in Table 1. Approximately 80% (27/34) of patients had a history of splenectomy because of splenic trauma. The mean time interval between splenectomy and hepatic splenosis detection was 25 years, with a range of 1.5 to 47 years. The median size of reported hepatic splenosis is 30 mm in diameter. Splenosis can occur anywhere within abdominal or pelvic cavity, even in the chest when the diaphragm is damaged simultaneously.5 Even if the real pathogenesis remains unclear, splenosis is now considered of developing from seeding of splenic fragments into exposed serosal surfaces at the time of splenic trauma or splenectomy.4 Moreover, another mechanism, especially for intrahepatic splenosis, is hematogenous spread of splenic pulp or erythrocyte progenitor cells and secondary growth in response to tissue hypoxia.34 In our case, perihepatic splenosis is probably because the space between the diaphragm and liver segment II is near the spleen and can be easily reached by splenic fragments during operation.

Table 1.

Literature Review of Hepatic Splenosis

The limitation of this case is that we did not take splenosis as a possible diagnosis before operation, because of lack of experience. The splenic trauma was supposed to be essential to consider this diagnosis. We reviewed the related literatures to gain more knowledge about this disease. This case report and literature review would be helpful for clinicians to distinguish splenosis and select diagnostic methods and treatment.

Usually, splenosis is asymptomatic. However, some clinical features have been reported, which includes abdominal pain or bowel obstruction associated with compression or sudden torsion of the solid lesion.3,6 In addition, gastrointestinal bleeding was also reported. In some cases of splenectomy for hematological diseases, it leads to recurrence of hematological manifestations. It is probably because that splenosis overtakes some function of the spleen. Howell–Jolly bodies, which are normally retained by normal spleen, could be seen diminishing or absent on the peripheral blood smears in patients with functioning splenosis. Unfortunately, it is difficult to distinguish hepatic splenosis from liver tumor due to lack of typical radiological features using conventional ultrasound, CT and MRI. Up to now, technetium-99m-labeled heat denatured red-blood-cells scintigraphy (Tc-99mHDRS) is considered to be the optimal method of diagnosing splenosis, but it fails to confirm the accurate anatomical localization.7 Furthermore, it has also been reported that superparamagnetic iron oxide-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (SPIO-MRI) is a useful diagnostic tool to distinguish hepatic splenosis from malignant hepatic tumor. Normal reticuloendothelial tissue indicates loss of signal intensity on T2-weighted MRI because natural reticuloendothelial cells phagocytose SPIO particles.8 Tumor cells usually do not phagocytose particles, which results in a cancer-to-liver intensity difference, but well-differentiated HCCs is an exception. Therefore, biopsy or operation could be avoided with the application of Tc-99mHDRS and SPIO-MRI in most situations. In our case, the young patient still wanted to confirm the diagnosis pathologically after he was informed that the lesion may be benign. In account of possible abdominal adhesion caused by the previous operation, finally, we chose a mini-incision laparotomy.

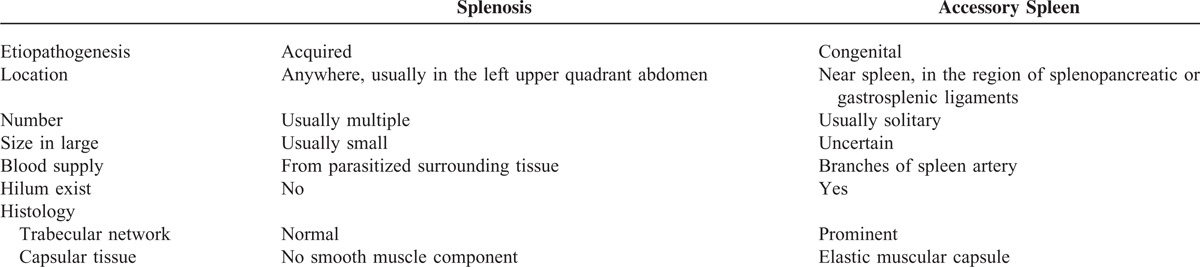

It is still challenging for clinicians to distinguish splenosis from hepatocellular carcinoma, hepatic adenoma, hemangioma, and focal nodular hyperplasia timely and correctly. A missed diagnosis of hepatic splenosis usually has a negative influence on patient's management. Besides, the most difficult differential diagnosis is of accessory spleen. We searched literatures and listed the main differences between these 2 ectopic spleen tissues in Table 2. The splenosis may have some immunologic value and splenic filtering function, which may be beneficial for organism. Thus, hepatic splenosis requires no treatment in most cases. In addition, splenosis with hematological diseases should be estimated on the basis of current spleen function. Operation should be performed if necessary. When the diagnosis remains unclear, further biopsy or laparoscopy is recommended. If hepatic splenosis is confirmed, careful follow-up is beneficial (Figure 4).

Table 2.

Differential Diagnosis Between Splenosis and Accessory Spleen

Figure 4.

Clinical algorithms for the evaluation of perihepatic splenosis. CT = computed tomography, Tc-99mHDRS = technetium-99m-labeled heat denatured red-blood-cells scintigraphy, MRI = magnetic resonance imaging, SPIO = superparamagnetic iron oxide, US, ultrasonography.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CT = computed tomography, DWI = diffusion-weighted imaging, HAV = hepatitis A virus, HBV = hepatitis B virus, HCC = hepatocellular carcinoma, SPIO-MRI = superparamagnetic iron oxide-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging, Tc-99mHDRS = Technetium-99m-labeled heat denatured red-blood-cells scintigraphy.

CW and BZ contributed equally to this article.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

This work is supported by The State Key Project on Inflection Disease of China (Grant No. 2012ZX10002016-004 and 2012ZX10002010-001-004), the Chinese Ministry of Public Health for Key Clinical Projects (No. 439, 2010), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.81372495) to Prof Xiaoping Chen.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albrecht H. A case of very large, throughout the peritoneal accessory spleen (German). Beitr Path Anat 1896; 20:513–527. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buchbinder J, Lipkoff C. Splenosis: multiple peritoneal splenic implants following abdominal injury. Surgery 1939; 6:927–934. [Google Scholar]

- 3.D’Angelica M, Fong Y, Blumgart LH. Isolated hepatic splenosis: first reported case. HPB Surg 1998; 11:39–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choi GH, Ju MK, Kim JY, et al. Hepatic splenosis preoperatively diagnosed as hepatocellular carcinoma in a patient with chronic hepatitis B: a case report. J Korean Med Sci 2008; 23:336–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Di Costanzo GG, Picciotto FP, Marsilia GM, et al. Hepatic splenosis misinterpreted as hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic patients referred for liver transplantation: report of two cases. Liver Transpl 2004; 10:706–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gruen DR, Gollub MJ. Intrahepatic splenosis mimicking hepatic adenoma. Am J Roentgenol 1997; 168:725–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grande M, Lapecorella M, Ianora AA, et al. Intrahepatic and widely distributed intraabdominal splenosis: multidetector CT, US and scintigraphic findings. Intern Emerg Med 2008; 3:265–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kang KC, Cho GS, Chung GA, et al. Intrahepatic splenosis mimicking liver metastasis in a patient with gastric cancer. J Gastric Cancer 2011; 11:64–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galloro P, Marsilia GM, Nappi O. Hepatic splenosis diagnosed by fine-needle cytology. Pathologica 2003; 95:57–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yeh ML, Wang LY, Huang CI, et al. Abdominal splenosis mimicking hepatic tumor: a case report. Kaohsiung J Med Sci 2008; 24:602–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abu Hilal M, Harb A, Zeidan B, et al. Hepatic splenosis mimicking HCC in a patient with hepatitis C liver cirrhosis and mildly raised alpha feto protein; the important role of explorative laparoscopy. World J Surg Oncol 2009; 7:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inchingolo R, Peddu P, Karani J. Hepatic splenosis presenting as arterialised liver lesion in a patient with NASH. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2013; 17:2853–2856. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Menth M, Herrmann K, Haug A, et al. Intra-hepatic splenosis as an unexpected cause of a focal liver lesion in a patient with hepatitis C and liver cirrhosis: a case report. Cases J 2009; 2:8335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu K, Liang Y, Liang X, et al. Laparoscopic resection of isolated hepatic splenosis mimicking liver tumors: case report with a literature review. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2012; 22:e307–e311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li H, Snow-Lisy D, Klein EA. Hepatic splenosis diagnosed after inappropriate metastatic evaluation in patient with low-risk prostate cancer. Urology 2012; 79:e73–e74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim KA, Park CM, Kim CH, et al. An interesting hepatic mass: splenosis mimicking a hepatocellular carcinoma (2003:9b). Eur Radiol 2003; 13:2713–2715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferraioli G, Di Sarno A, Coppola C, et al. Contrast-enhanced low-mechanical-index ultrasonography in hepatic splenosis. J Ultrasound Med 2006; 25:133–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee JB, Ryu KW, Song TJ, et al. Hepatic splenosis diagnosed as hepatocellular carcinoma: report of a case. Surg Today 2002; 32:180–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu HC, Su CW, Lu CL, et al. Hepatic splenosis diagnosed by spleen scintigraphy. Am J Gastroenterol 2008; 103:1842–1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Foroudi F, Ahern V, Peduto A. Splenosis mimicking metastases from breast carcinoma. Clin Oncol 1999; 11:190–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davidson LA, Reid IN. Intrahepatic splenic tissue. J Clin Pathol 1997; 50:532–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsitouridis I, Michaelides M, Sotiriadis C, et al. CT and MRI of intraperitoneal splenosis. Diagn Interv Radiol 2010; 16:145–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mescoli C, Castoro C, Sergio A, et al. Hepatic spleen nodules (HSN). Scand J Gastroenterol 2010; 45:628–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu H, Xia L, Li T, et al. Intrahepatic splenosis mimicking hepatoma. BMJ Case Rep 2009; 2009: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoshimitsu K, Aibe H, Nobe T, et al. Intrahepatic splenosis mimicking a liver tumor. Abdom Imaging 1993; 18:156–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pekkafali Z, Karsli AF, Silit E, et al. Intrahepatic splenosis: a case report. Eur Radiol 2002; 12 suppl 3:S62–S65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Vuysere S, Van Steenbergen W, Aerts R, et al. Intrahepatic splenosis: imaging features. Abdom Imaging 2000; 25:187–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kondo M, Okazaki H, Takai K, et al. Intrahepatic splenosis in a patient with chronic hepatitis C. J Gastroenterol 2004; 39:1013–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kashgari AA, Al-Mana HM, Al-Kadhi YA. Intrahepatic splenosis mimicking hepatocellular carcinoma in a cirrhotic liver. Saudi Med J 2009; 30:429–432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gamulin A, Oberholzer J, Rubbia-Brandt L, et al. An unusual, presumably hepatic mass. Lancet 2002; 360:2066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakajima T, Fujiwara A, Yamaguchi M, et al. Intrahepatic splenosis with severe iron deposition presenting with atypical magnetic resonance images. Intern Med 2008; 47:743–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao M, Xu HW. Splenosis simulating an intrahepatic mass. Chin J Traumatol 2004; 7:62–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu Y, Ji B, Wang G, et al. Abdominal multiple splenosis mimicking liver and colon tumors: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Med Sci 2012; 9:174–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kwok CM, Chen YT, Lin HT, et al. Portal vein entrance of splenic erythrocytic progenitor cells and local hypoxia of liver, two events cause intrahepatic splenosis. Med Hypotheses 2006; 67:1330–1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]