Abstract

Ocular cysticercosis refers to parasitic infections in humans. Most cases were treated by medicine. The case we reviewed was rarely reported with successful surgical intervention treatment.

This case report describes a patient with cysticercosis existing in superior oblique tendon. The main symptom of the patient was recurring history of painless orbital swelling and double vision in upgaze. Ocular motility examination revealed a restriction of the right eye in levoelevation. A contrast-enhanced computed tomographic scan of the orbit revealed the presence of a well-defined hypodense cystic lesion within the right superior oblique muscle.

The patient was diagnosed with orbital space-occupying mass with acquired Brown syndrome. Surgical exploration of the superior oblique muscle was performed, and the cyst was removed from the eye and confirmed by histopathological examination. After surgery, an ocular motility examination revealed orthotropia in the primary position and downgaze, with mild restriction in levoelevation.

Surgical removal could substitute for medical therapy when the cysticercosis is lodged in the superior oblique muscle, although, prior to surgery, important factors, such as patient requirements, surgical skills of the surgeon, and cyst placement, should be considered.

INTRODUCTION

Ocular cysticercosis is one of the most common parasitic infections in humans. Humans are occasionally infected with Taenia solium through the ingestion of contaminated water or uncooked pork and through autoinfection.1 This article describes an unusual case in which a cysticercosis exists in the superior oblique tendon. The cysticercosis was removed from the eye, as confirmed by histopathological examination.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 28-year-old male patient with a 1-month recurring history of painless orbital swelling and double vision in upgaze since June 2013 presented himself at the Orbital and Plastic Department of Tianjin Eye Hospital. He displayed symptoms after a high fever, which has also been recurring since June 2013. No histories of decreased vision, trauma, or animal bite were reported. In addition, no previous histories of tapeworm infection or surgical operations were stated. The patient denied traveling to endemic regions. The patient reported an old habit of eating baked meat but could not recall the exact date of the last incident before his illness. No abnormalities were detected after a general examination (eg, physical, systemic, and neurological).

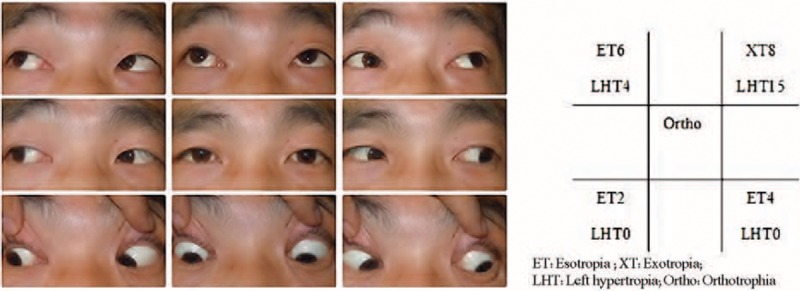

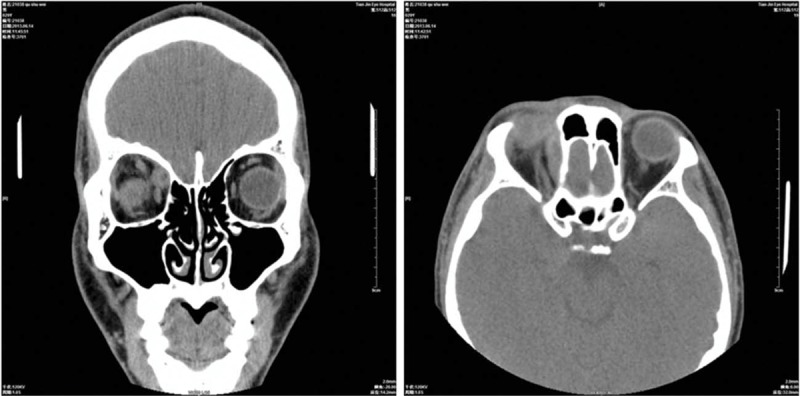

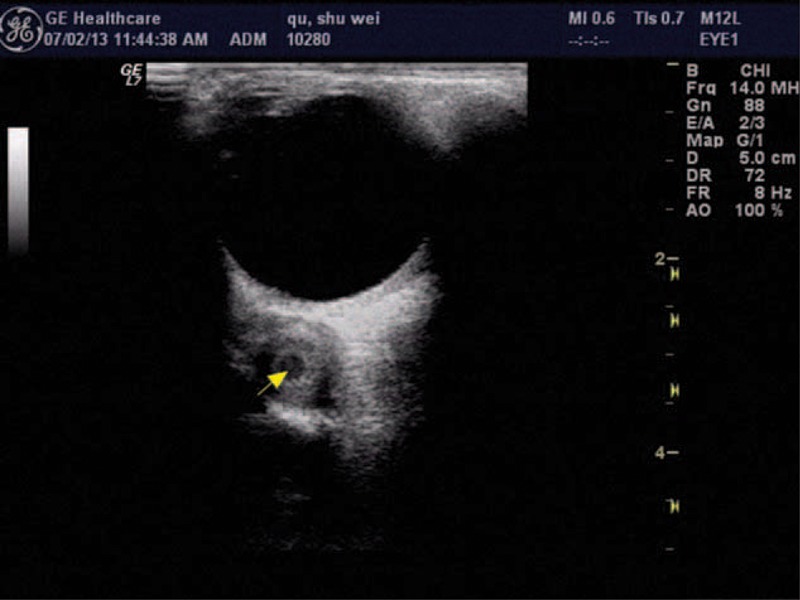

Upon ophthalmological examination, visual acuity was 20/20 in both eyes. The patient had normal stereoacuity of 40 seconds of arc. The ocular motility examination revealed orthotropia in the primary position; a restriction of the right eye in levoelevation was also noted (Figure 1). No significant incoordination of ocular movements was found in any gaze. Measurements revealed maximum diplopia in levoelevation. The patient exhibited 1 mm of left enophthalmos over the right eye, with erythema and mild edema in the tender right upper eyelid. A forced duction test of the right eye was positive for elevation in adduction. The anterior and posterior segments of both eyes showed no significant findings. A contrast-enhanced computed tomographic scan of the orbit revealed the presence of a well-defined hypodense cystic lesion within the right superior oblique muscle (Figure 2). The same lesion was observed using the orbital color Doppler ultrasound (Figure 3). No radiological signs indicating brain infection were found (neurocysticercosis). On the basis of the above findings, the patient was diagnosed with orbital space-occupying mass with acquired Brown syndrome.

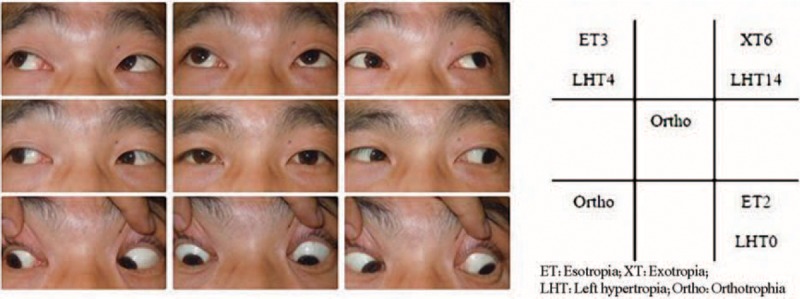

FIGURE 1.

Clinical photograph of 9 diagnostic positions before operation and the measurements of deviation (showing limitation of elevation in adduction of the right eye). ET = esotropia, LHT = left hypertropia, Ortho = orthotropia, XT = exotropia.

FIGURE 2.

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan of orbits showing a well-defined ring-enhancing lesion with an eccentric scolex in the right superior oblique muscle.

FIGURE 3.

Doppler ultrasonography showing cyst with scolex of superior oblique muscle (arrows) at the time of presentation.

Direct muscle infiltration of some organism was suspected. Treatment for the orbital space-occupying mass was divided into 2 parts: medication therapy and surgical method. All treatments, complications, and procedures were discussed. The patient decided to undergo early surgery because of the concern of long-term organism-induced changes in the muscle during medical treatment. The protocol for treatment was approved by our institutional ethics committee on human research (Tianjin Eye Hospital ethics committee).

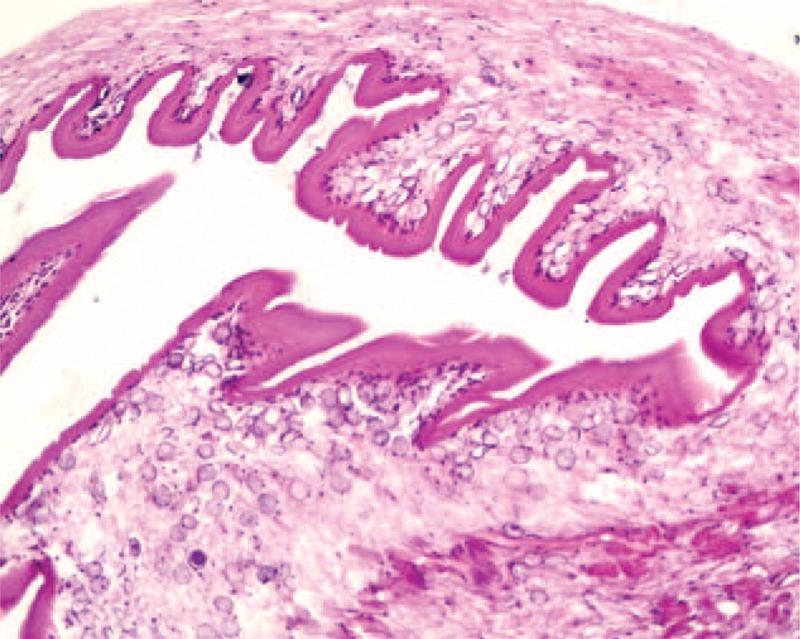

Surgical excision of the superior oblique muscle was performed under general anesthesia. Incisions that extended 1.5 cm to the lateral canthus were first made to widen the nasal side and to release soft tissue. Exploration was started through conjunctival (superior nasal fornix) incision. During surgical exploration of the superior oblique muscle, a swollen tendon came to view. The cyst flew from the tendon when the sheath was cut for almost 5 mm along the tendon (Figure 4). Pathological findings indicate a 25 mm of moderately firm pink–gray mass. The mass had cystic microscopic features, as confirmed through histopathological examination (Figure 5).

FIGURE 4.

Gross appearance of the mass.

FIGURE 5.

Histopathology of the cyst.

The patient still complained of diplopia in the upgaze during his 9th-month follow-up. Ocular motility examination revealed orthotropia in the primary position and downgaze; a mild restriction in the superior adduction and abduction was also observed (Figure 6). Proptosis returned to normal, and hertel exophthalmometer readings were at 19 mm for both eyes. The eyelid abnormalities dissipated over time. Lateral canthus scarring showed improvement during the 9th-month follow-up.

FIGURE 6.

Clinical photograph of 9 diagnostic positions after operation and the measurements of deviation (showing limitation of elevation in adduction of the right eye). ET = esotropia, LHT = left hypertropia, Ortho = orthotropia, XT = exotropia.

DISCUSSION

The patient developed acquired Brown syndrome secondary to orbital cysticercosis, one of the most common intraorbital parasites. Ocular cysticercosis is found in the subconjunctival or orbital tissues (ie, extraocular) or in the anterior chamber, vitreous, or subretinal space (ie, intraocular).1–3 A retrospective case series study shows that 80.7% of patients had cysts in the extraocular muscle4; the lateral rectus, medial rectus, and superior oblique were shown to be affected to a greater extent.5

Cysticercosis commonly affects extraocular muscles,6 leading to restricted ocular movements and inflammatory signs.7 Orbital cysticercosis is medically managed in 95.18% of patients4 and has favorable cure rates.4,8 A combination of oral albendazole and prednisolone was provided to 89.76% of patients.

Surgical excision is another option in managing the infection. However, reports show that surgery was performed only on 8 of the 166 patients (5%).4 Surgery was available for only a few cases because of the small visualization space. Specifically, excision in the superior oblique muscle is difficult. Management principles and goals of different therapies were discussed with the patient, and the various complications were reviewed. By comparing our treatment with the previous medical therapy,8 we found that both therapies have residual effects of mild restriction in the extreme fields of the upgaze. The patient was anxious about possible cyst growth in the muscle under long-term medical therapy treatment. Therefore, we decided to perform surgery on the patient.

For a wider exploration field, lateral canthus incision was performed to release soft tissue into lateral space. We cut the sheath by using supportive instruments. A small incision (5 mm) was made without destroying the muscle to restore normal muscle functionality. Although the surgical excision was successful, motility restriction deficits still persisted during the 9th-month follow-up. Fortunately, no restriction in the downgaze was noted after surgery.

Surgery was not proven superior to medical treatment in this case. Prior to surgery, important factors, such as patient requirements, surgical skills of the surgeon, and cyst placement, should be considered.

CONCLUSION

Surgical removal could substitute for medical therapy when the cysticercosis is lodged in the superior oblique muscle. However, surgical treatment for ocular rectus muscle cysts is still contraindicated because of the extensive resections needed and the possibility of inducing a fibrotic reaction, which further restricts ocular movement after surgery.9

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs Yueping Li, MD, and Jie Zhang, MD, for helpful discussion.

Footnotes

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

JD contributed to reports’ retrieval and drafting of this article. HZ and JD contributed to the surgical procedures of this case report. JL contributed to the pathological analysis.

The authors have no funding and conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sawhney IM, Singh G, Lekhra OP, et al. Uncommon presentations of neurocysticercosis. J Neurol Sci 1998; 154:94–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loo L, Braude A. Cerebral cysticercosis in San Diego: a report of 23 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 1982; 61:341–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McComick G, Zec CS, Heiden J. Cysticercosis cerebri. Review of 127 cases. Arch Neurol 1982; 39:534–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rath S, Honavar SG, Naik M, et al. Orbital cysticercosis: clinical manifestations, diagnosis, management, and outcome. Ophthalmology 2010; 117:600–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sundaram PM, Jayakumar N, Noronha V. Extraocular muscle cysticercosis: a clinical challenge to the ophthalmologists. Orbit 2004; 23:255–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sekhar GC, Lemke BN. Orbital cysticercosis. Ophthalmology 1997; 104:1599–1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pushker N, Bajaj MS, Chandra M, et al. Ocular and orbital cysticercosis. Acta Ophthalmol Scand 2001; 79:408–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rao VB, Sahare P, Varada V. Acquired Brown syndrome secondary to superior oblique muscle cysticercosis. J AAPOS 2003; 7:23–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ziaei M, Elgohary M, Bremner FD. Orbital cysticercosis, case report and review. Orbit 2011; 30:230–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]