Abstract

Background:

Serine hydrolases (SHs) are among the largest classes of enzymes in humans and play crucial role in many pathophysiological processes of cancer. We have undertaken a comprehensive proteomic analysis to assess the differential expression and cellular localization of SHs, which uncovered distinctive expression of Carboxylesterase 2 (CES2), the most efficient carboxyl esterase in activating the prodrug irinotecan into SN-38, in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC). We therefore assessed the extent of heterogeneity in CES2 expression in PDAC and its potential relevance to irinotecan based therapy.

Methods:

CES2 expression in PDAC and paired nontumor tissues was evaluated by immunohistochemistry. CES2 activity was assessed by monitoring the hydrolysis of the substrate p-NPA and correlated with irinotecan IC50 values by means of Pearson’s correlation. Kaplan-Meier and Cox regression analyses were applied to assess the association between overall survival and CES2 expression in patients who underwent neoadjuvant FOLFIRINOX treatment. All statistical tests were two-sided.

Results:

Statistically significant overexpression of CES2, both at the mRNA and protein levels, was observed in PDAC compared with paired nontumor tissue (P < .001), with 48 of 118 (40.7%) tumors exhibiting high CES2 expression. CES2 activity in 11 PDAC cell lines was inversely correlated with irinotecan IC50 values (R = -0.68, P = .02). High CES2 expression in tumor tissue was associated with longer overall survival in resectable and borderline resectable patients who underwent neoadjuvant FOLFIRINOX treatment (hazard ratio = 0.14, 95% confidence interval = 0.04 to 0.51, P = .02).

Conclusion:

Our findings suggest that CES2 expression and activity, by mediating the intratumoral activation of irinotecan, is a contributor to FOLFIRINOX sensitivity in pancreatic cancer and CES2 assessment may define a subset of patients likely to respond to irinotecan based therapy.

Serine hydrolases (SHs) are among the largest and most diverse classes of enzymes in humans consisting of approximately 278 expected members that encompass proteases, esterases, thioesterases, amidases, and lipases (1,2). SHs have crucial roles in numerous pathophysiological processes being implicated in angiogenesis, tumorigenesis, and metastasis (3–7). A growing number of selective inhibitors have been developed for this enzyme class for different therapeutic applications (8). Subsets of SHs, which are involved in the detoxification of xenobiotics, also play important roles in drug metabolism and their activity has been considered to be relevant for therapies currently in use for cancer (8).

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is the fourth leading cause of cancer mortality in the United States (9). Multimodality therapy including surgical resection of the primary tumor and regional lymph nodes represents the only curative treatment, but because of late diagnosis most patients present at an advanced stage and are not eligible for surgical intervention (10). The recent emergence of active combination chemotherapy regimens has led to incremental improvements in overall survival. FOLFIRINOX (11) and gemcitabine with nab-paclitaxel (12) represent clinically meaningful improvements over single-agent gemcitabine. However, PDAC is characterized by profound resistance to anticancer drugs and there is a lack of predictive markers to guide the choice of therapeutic agents for individual patients.

Given the role of SHs in drug metabolism and their relevance to therapies currently in use for cancer, we initially undertook a comprehensive proteomic analysis to determine the range of SHs expression in 82 human cancer cell lines using mass spectrometry, with a focus on potential differential expression of SHs in PDAC. Carboxylesterase 2 (CES2) protein expression levels were remarkably elevated in some PDAC cell lines. CES2 is the most efficient carboxyl esterase in converting irinotecan, a prodrug applied to the treatment of PDAC and a number of other solid tumors, into its active form SN-38, which induces apoptosis by inhibiting topoisomerase I (13). Hepatic activation of irinotecan has been shown to be only partially predictive of tumor response, given the large variability in CES2 activity in the liver (14,15). In this study we have assessed the extent of variability in CES2 expression in PDAC and its potential relevance to FOLFIRINOX treatment, which includes irinotecan as an active component.

Methods

Patients and Clinical Specimens

PDAC specimens were obtained from patients who underwent resection for curative intent at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. Patients provided written informed consent under a research protocol approved by our institutional review board. Clinico-pathologic patient characteristics, including age, sex, and race, and clinical, radiological, and pathologic variables, were obtained from a translational and clinical database maintained by the Department of Surgical Oncology (16). Tissue samples from 118 PDAC patients who did not receive any form of preoperative therapies, with clinical features described in Supplementary Table 1 (available online), were utilized for tissue microarray immunohistochemical analysis. Clinical features of 22 patients who underwent neoadjuvant FOLFIRINOX treatment are described in Supplementary Table 2 (available online). Our group has a well-documented bias toward the administration of preoperative chemotherapy and/or chemoradiation prior to intended surgical resection to most patients with resectable or borderline resectable pancreatic cancer (17); the patients included herein had localized cancers and a performance status and comorbidity profile appropriate for systemic FOLFIRINOX treatment and were treated either on or off protocol (18). For patients treated on protocol, FOLFIRINOX (oxaliplatin 75mg/m2 d1+ irinotecan 150mg/m2 d1+ 5-FU 2000mg/m2 46h CI for 6 cycles) was administered to patients with either borderline resectable anatomy or high-risk clinical features (elevated CA 19-9 or nonspecific imaging findings suggestive of metastatic disease) prior to EBRT 50.4 Gy with weekly Gemcitabine 350mg/m2 and surgery. For each patient treated off protocol, the specific regimen employed was chosen based on the individual’s clinical status by a multidisciplinary team of surgeons, medical oncologists, and radiation oncologists; preoperative chemoradiation was still favored in most cases. Primary tumor resection was performed four to eight weeks later in the absence of disease progression to all patients who had an acceptable performance status following a complete clinical and radiographic evaluation (19).

Cell Lines and Mass Spectrometry Analysis

Eighty-two cell lines were subjected to mass spectrometry based proteomic profiling of their whole cell lysates, cell surface and secretome (Supplementary Table 3, available online). Detailed analysis procedures and methods for cell culture, subcellular fractionation, mass spectrometry, and statistical analysis are provided in the Supplementary Methods (available online). Cell transfection, viral transduction, cell viability assay, and Western blot analysis are described in the Supplementary Methods (available online).

RNA-Sequencing and Quantitative Real-Time Reverse Transcription–Polymerase Chain Reaction

Details on quantitative real-time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR), RNA-sequencing data processing, and The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) RNA-seq data analysis are provided in the Supplementary Methods (available online).

CES2 Activity Assay

CES2 activity was measured by following the hydrolysis of para-nitrophenyl acetate (p-NPA, 3mM) at 405nm as previously described (20,21). Details are given in the Supplementary Methods (available online).

Tissue Microarray and Immunohistochemical Analysis

The tissue microarrays were constructed as described previously (22). Immunohistochemical staining for CES2 is described in the Supplementary Methods (available online). Slides for CES2 expression were reviewed by two pathologists (HW and WT) and graded as: high CES2, strong staining (score 3) in 10% or more cells; intermediate CES2, moderate staining (score 2) in 10% or more cells; low CES2, negative or weak staining.

Patient-Derived Xenograft Models

Heterotopic engraftment of patient-derived xenograft model (PDAC) patient primary tumors removed surgically at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center into immunodeficient mice and expansion of direct xenograft tumors were performed as previously described (23,24). Animal care was in accordance with institutional guidelines. Details are provided in the Supplementary Methods (available online).

Statistical Analysis

Categorical data were compared by Fisher’s exact test. Student’s t test, Welch’s t test, or Mann-Whitney t test was used to assess the differences in continuous variables, as appropriate. Pearson’s correlation was applied to assess the linear association between two variables. Overall survival curves were constructed using the Kaplan-Meier method, and the log-rank test was used to evaluate the statistical significance of differences. Overall survival was defined as the time from initial neoadjuvant FOLFIRINOX therapy to the date of death attributed to pancreatic cancer or last follow-up, at which point the data were censored. Progression-free survival was defined as the time elapsed between treatment initiation and tumor recurrence or progression after surgery. Multivariable Cox regression analysis was performed to test the combination of CES2 expression along with the other variables from baseline clinicopathological parameters. Assumption of proportionality was checked by plotting the log(-log(S(t)) over time. Variables were included simultaneously in the statistical model and selected by a backward stepwise method (P for removal .05). Statistical analysis was done using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (IBM SPSS Statistics 22; IBM Corporation, Somers, NY), MedCalc (Version 14.10.2; MedCalc Software, Ostend, Belgium), and GraphPad Prism (Version 6.0; GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA) software. We used a two-sided statistical significance level of .05 for all statistical analyses.

Results

Proteomic Profiling of Serine Hydrolases in a Panel of Human Cancer Cell Lines

In-depth proteomic profiling by mass spectrometry (MS) was applied to established human cancer cell lines consisting of 11 PDAC, eight breast, eight ovarian, six colon, four small cell lung cancer, and 45 non–small cell lung cancer cell lines (Supplementary Figure 1, available online). Cells were grown in SILAC media to incorporate 13C-lysine into newly synthesized proteins. Proteomes from total cell lysate (TCL), conditioned media, and proteins from the cell surface tagged with biotin and captured by affinity to avidin were fractionated at an intact protein level and then subjected to trypsin digestion and MS-based analysis. Analysis of protein expression was based on MS2 spectral counts normalization in relation to the total MS2 spectral count for a given proteome. In total, we identified 135 of the 278 predicted SHs based on protein sequence homology, with five or more MS2 events detected per protein (Supplementary Table 4, available online). Subsets of 84, 93, and 113 members were identified in TCL, media, and cell surface compartments, respectively. The expression level and subcellular localization of SHs differed substantially among the cell lines. A comparison of relative abundance in different compartments across the entire panel of cancer cell lines revealed predominance of three, 21, and two SHs in TCL, media, and on the cell surface, respectively (Supplementary Table 5, available online), whereas the remaining 109 SHs were not enriched in any cellular compartment. Eight SHs exhibited statistically significantly elevated expression in PDAC cell lines relative to other cell lines (>5-fold, P < .05) in one or more cellular compartments (Table 1). Unsupervised hierarchical clustering analysis of surface SHs revealed a clustering of nine of the 11 PDAC cell lines, suggestive of a pancreatic cancer-restricted SH surface signature (Supplementary Figure 2, available online). CES2 was the protein most statistically significantly elevated in PDAC cell lines in all three cellular compartments analyzed. CES2, which has been known to be localized to the ER lumen (25), also occurred on the cell surface and in the media of PDAC cell lines.

Table 1.

Serine hydrolase signature associated with pancreatic cancer cell lines

| Gene* | Total cell lysate | Media | Cell surface | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean MS2# | P † | Mean MS2# | P † | Mean MS2# | P† | |||||||

| Pancreatic cancer | Other cancers | Fold change | Pancreatic cancer | Other cancers | Fold change | Pancreatic cancer | Other cancers | Fold change | ||||

| CES2 | 10.3 | 1.4 | 7.2 | <.001 | 12.7 | 0.7 | 17.2 | <.001 | 6.4 | 0.1 | 57.9 | <.001 |

| DPP4 | 11.2 | 1.4 | 8.2 | .02 | 34.7 | 9.7 | 3.6 | .04 | 39.6 | 34.8 | 1.1 | .16 |

| LIPA | 9.0 | 1.3 | 6.9 | <.001 | 32.7 | 17.6 | 1.9 | .006 | 3.7 | 0.2 | 17.3 | <.001 |

| ACOT1 | 2.3 | 1.0 | 2.3 | .79 | 0.0 | 0.0 | - | - | 3.4 | 0.3 | 11.6 | .001 |

| KLK6 | 7.1 | 0.9 | 8.3 | <.001 | 209.1 | 46.0 | 4.6 | .14 | 8.3 | 1.2 | 6.8 | .004 |

| KLK10 | 2.7 | 0.1 | 19.0 | <.001 | 79.8 | 4.9 | 16.4 | <.001 | 8.9 | 1.0 | 8.9 | <.001 |

| KLK11 | 1.0 | 0.0 | - | - | 20.6 | 2.5 | 8.1 | <.001 | 3.1 | 0.0 | 100.6 | .002 |

| TMPRSS4 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 3.3 | .007 | 4.9 | 0.0 | 183.6 | <.001 | 16.9 | 2.1 | 8.1 | .006 |

* Mean MS2 counts (MS2#) for eight serine hydrolases with statistically significantly elevated protein expression in pancreatic cancer cell lines compared with other cancer type cell lines.

† P values were calculated by two-sided Mann-Whitney t test.

Analysis of CES2 Expression in Pancreatic Cancer Cell Lines and Tumor Tissue Specimens

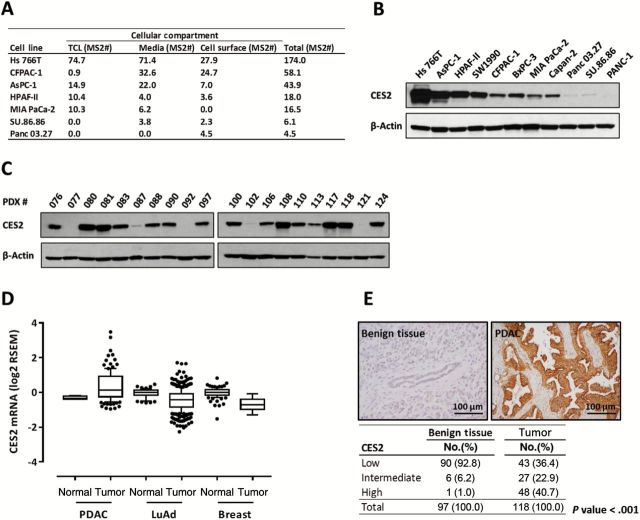

CES2 protein expression, based on MS analysis, occurred primarily among PDAC cell lines relative to other cancer types and substantial heterogeneity in both protein expression levels and subcellular localization was observed among cell lines (Figure 1A). CES2 peptide coverage by MS spanned the esterase domain in all three compartments analyzed (Figure Supplementary 3, available online), suggesting occurrence on the cell surface and secretion into the media of a potentially active protein, rather than protein fragments produced by proteolysis. CES2 mRNA levels measured by RNA sequencing in PDAC cell lines correlated with findings by MS (R = 0.76, P = .006, Pearson correlation) (Supplementary Figure 4, available online). Heterogeneity in CES2 protein expression among PDAC cell lines was confirmed by western blot analysis (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Analysis of CES2 expression in pancreatic cancer cell lines and tissues. A) Protein expression level of CES2 in pancreatic cancer cell lines based on normalized MS2 spectral counts (MS2#). Pancreatic cancer cell lines in which CES2 was identified with two or more different peptides by MS analysis in total cell lysate (TCL), media, or cell surface (CES2-positive) are listed. All colon, breast, and SCLC cell lines were CES2 negative. Only one out of 45 NSCLC (H2405) and one out of eight ovarian cancer cell lines (Skov3) were positive for CES2 by MS analysis. B-C) Western blot analysis of CES2 expression in pancreatic cancer cell lines (B) and patient-derived xenograft (PDX) tumors (C). β-actin served as a loading control. D) CES2 mRNA expression levels in normal pancreas (n = 4), pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC, n = 112), normal lung (n = 58), lung adenocarcinoma (LuAd, n = 423), normal breast (n = 108), and breast cancer (n = 610) tissues based on The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) RNA-seq data. Boxes indicate 25th and 75th percentiles, and horizontal lines inside the boxes indicate median. Bars indicate 10th and 90th percentiles. Data have normal tissue median value subtracted. P values were calculated by two-sided unpaired t test: normal pancreas vs PDAC P < .001, vs normal lung P = .58, vs normal breast P = .79; normal lung vs LuAd P < .001, vs PDAC P < .001; normal breast vs breast cancer P < .001, vs PDAC P < .001. E) Immunohistochemical analysis, using tissue microarray, of CES2 expression in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC). Representative micrographs showing strong cytoplasmic staining for CES2 in moderately differentiated PDAC and negative CES2 staining in nontumoral pancreatic tissue (upper panel). Percentages of analyzed PDAC and paired nontumoral pancreatic tissues segregated according to CES2 expression levels. High CES2: strong staining (score 3) in 10% or more cells (bottom panel). Intermediate CES2: moderate staining (score 2) in 10% or more cells. Low CES2: negative or weak staining. Fisher’s exact test was applied to calculate two-tailed P value. LuAd = lung adenocarcinoma; PDAC = pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma; PDX = patient-derived xenograft.

We established a panel of 20 pancreatic cancer primary xenograft (PDX) models derived directly from patient tumor material. CES2 protein expression in these models was assessed by Western blot analysis (Figure 1C). Consistent with PDAC cell line findings, CES2 expression in PDX tissues was widely distributed. CES2 expression was either high or undetectable in half of PDX tissues, and intermediate expression levels were observed in the remainder. CES2 mRNA and protein expression in primary PDAC tissues were evaluated in comparison to nontumor pancreatic tissue. The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) RNA-seq data revealed that CES2 mRNA expression was statistically significantly higher in PDAC (n = 112) compared with nontumor pancreatic tissue (n = 4, P < .001, Welch’s t-test) (Figure 1D), while lung adenocarcinoma (n = 423) and breast cancer (n = 610) tissues did not reveal increased CES2 levels in tumor compared with normal tissue (lung: n = 58, breast: n = 108). Similarly, immunohistochemical analysis using tissue microarrays revealed that CES2 expression was statistically significantly higher in PDAC compared with benign pancreatic tissue (P < .001, Fisher’s exact test) (Figure 1E). Among the 118 analyzed pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas, 63.6% (75/118) were positive for CES2, compared with only 7.2% (7/97) of paired benign pancreatic tissues, and 40.7% (48/118) showed a high expression of CES2 (Figure 1E). CES2 expression was not statistically significantly associated with overall survival (log-rank P = .66) or any other clinical feature in this set of patients (data not shown).

Given the prominent expression of CES2 in PDAC tissues and PDAC cell lines, we investigated the effect of its knockdown on the viability of three PDAC cell lines with varying expression of CES2 (Supplementary Figure 5A, available online). MTS colorimetric assay revealed no cytotoxic effect of siRNA CES2 knockdown at 72 hours post-transfection (Supplementary Figure 5B, available online), suggesting that CES2 expression is dispensable for PDAC cell viability.

CES2 Expression and Response to Irinotecan-Based Treatment of Pancreatic Cancer Cells

Carboxylesterase enzymes play important roles in the hydrolysis of drugs and xenobiotics and CES2 is the most efficient carboxylesterase at activating the prodrug irinotecan in humans. Hydrolysis of irinotecan into SN-38 by CES2 induces apoptosis by inhibiting the DNA repair enzyme topoisomerase 1 (TOP-1). We hypothesized that conversion of irinotecan by CES2 in PDAC cells would enhance the antitumor efficacy and selectivity of the drug. Irinotecan exhibited a concentration-dependent cytotoxic effect on pancreatic cancer cells with half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values ranging from 4.19 to 40.4 μM (Figure 2, A and B). To address whether irinotecan sensitivity was dependent on CES2-mediated activation of the prodrug, we measured CES2 activity by monitoring hydrolysis of para-nitrophenyl acetate, a nonspecific substrate of various esterases (26), into para-nitrophenol acid in the presence or absence of the CES2-selective inhibitor, loperamide (Figure 2C) (27–29). CES2 activity and irinotecan IC50 values were inversely correlated (R = -0.68, P = .02, Pearson correlation) (Figure 2D), whereby PDAC cell lines with greater CES2 activity responded at relatively lower concentration of irinotecan. Interestingly, irinotecan sensitivity was statistically significantly higher in cell lines in which CES2 was identified in the cell surface or media compartments by MS (Supplementary Figure 6A, available online).

Figure 2.

Analysis of irinotecan sensitivity in relation to CES2 activity in pancreatic cancer cell lines. A) Half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values of irinotecan in pancreatic cancer cell lines. B) Percent survival of pancreatic cancer cell lines after treatment with increasing molar concentrations (log scale) of irinotecan. Curves were fitted by nonlinear regression analysis. C) CES2 activity in pancreatic cancer cell lines. Activity was assessed by monitoring transformation of para-nitrophenolic acetate into its hydrolyzed analogue, para-nitrophenol (p-NP), in the presence or absence of CES2-selective inhibitor, loperamide. Activity is expressed in unit of nmoles of p-NP formed per minute per one mg of cell lysate. D) Pearson’s correlation analysis between irinotecan IC50 and CES2 activity values in pancreatic cancer cell lines. Results are the mean ± SD (error bars) of three independent experiments of five replicates. Two-sided P value was calculated by Pearson’s correlation analysis. IC50 = half-maximal inhibitory concentration; p-NP = para-nitrophenol.

Because the irinotecan metabolic pathway is highly regulated (Supplementary Figure 6B, available online), we assessed the correlation between irinotecan IC50 and mRNA expression, measured by RNA sequencing analysis, of genes other than CES2 involved in irinotecan metabolism. Neither expression of the target of the drug, TOP-1, nor expression of the molecules that are involved in its export (ABCB1, ABCC2) or inactivation (CYP3A4, CYP3A5, UGT1A10), yielded a statistically significant correlation between their expression and irinotecan IC50 (Supplementary Figure 6C, available online).

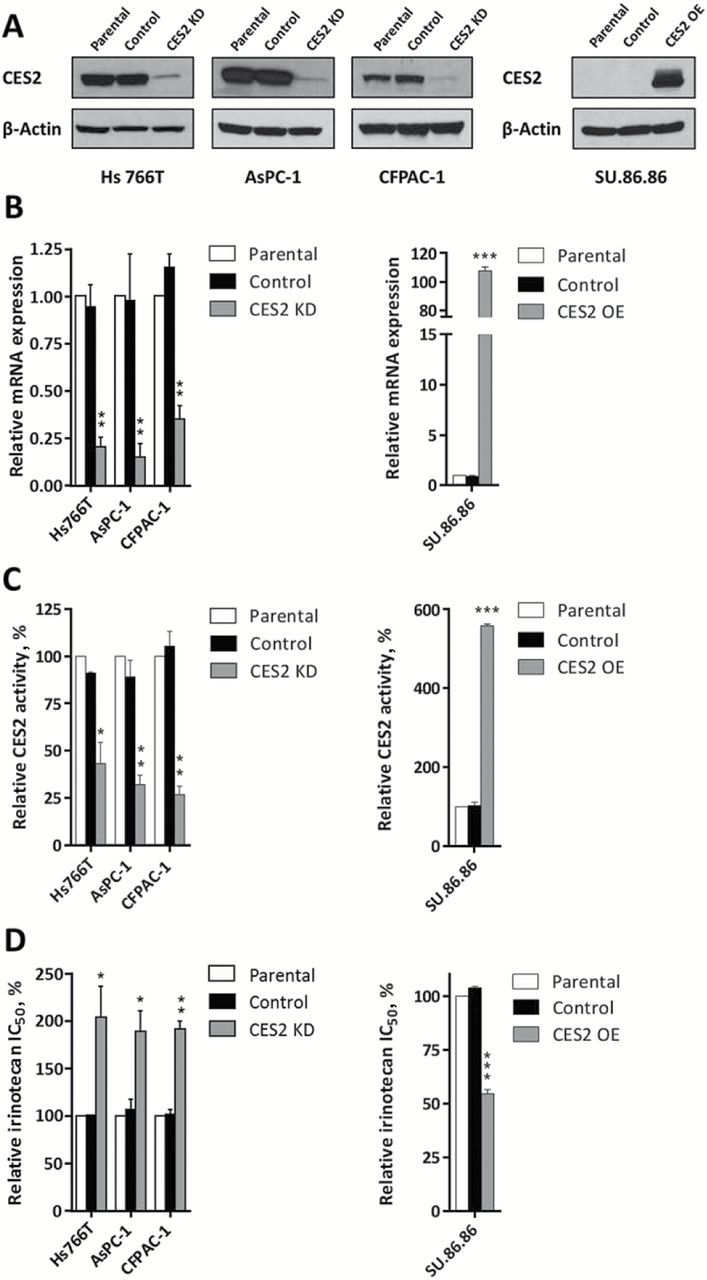

We assessed the effect of stable CES2 silencing or overexpression on the sensitivity of pancreatic cancer cells to irinotecan. Three PDAC cell lines, Hs 766T, AsPC-1 and CFPAC-1, with varying expression of CES2, were infected with a lentiviral vector (pLKO.1-puro) delivering a short hairpin RNA targeting CES2, while Su.86.86 cell line which displayed low CES2 expression was stably transduced with a lentiviral construct (pLenti-C-Myc-DDK-IRESPuro) overexpressing CES2. Both constructs affected CES2 expression at protein and mRNA levels by 70% to 90% (Figure 3, A and B). Enzymatic activity was concurrently modulated after CES2 knockdown or overexpression (Figure 3C). As observed with transient CES2 silencing (Supplementary Figure 5B, available online), stable alteration of CES2 expression did not affect cell viability (data not shown). Notably, all three knockdown cell lines were statistically significantly more resistant to irinotecan than control cells. Su.86.86 cells exhibited a statistically significant increase in sensitivity to the drug after CES2 overexpression (P < .001) (Figure 3D).

Figure 3.

Effect of CES2 knockdown and overexpression on pancreatic cancer cell irinotecan sensitivity. A) Western blot analysis of CES2 expression in: (left panel) Hs 766T, AsPC-1 and CFPAC-1 pancreatic cancer cell lines nontransduced (parental) and stably transduced with a shRNA targeting CES2 (CES2 KD) or a scrambled shRNA as a control (control); and (right panel) SU.86.86 pancreatic cancer cell line nontransduced (parental) and stably transduced with a lentiviral construct overexpressing CES2 (CES2 OE), and the respective empty vector as a control (control). β-actin was used as loading control. B) Quantitative real-time polyermase chain reaction analysis of CES2 transcript levels, C) relative CES2 activity, and D) relative half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of irinotecan in the above described pancreatic cancer cell lines after CES2 knockdown and overexpression. Results are the mean of three independent experiments ± SD (error bars) of triplicates. P values were calculated by two-sided unpaired t test. *P < .05, ** P < .01, *** P < .001 relative to parental cell lines. CES2 KD = CES2 knockdown; CES2 OE = CES2 overexpression; IC50 = half-maximal inhibitory concentration.

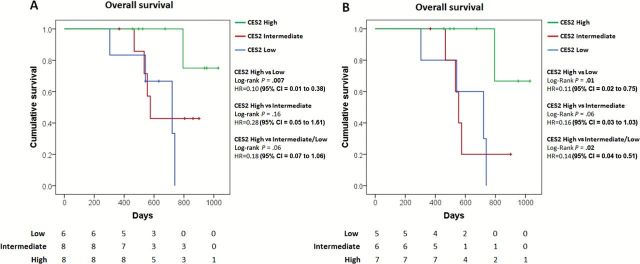

We assessed the clinical relevance of CES2 expression in relation to response to irinotecan-based therapy in PDAC. FOLFIRINOX is a combination chemotherapy which includes irinotecan as an active component, which is used in advanced pancreatic cancer as well as, increasingly, a preoperative therapy (30). We evaluated, through immunohistochemical analysis, CES2 expression in an independent set of PDAC patients (n = 22), presenting with resectable disease, who underwent FOLFIRINOX treatment as a first-line neoadjuvant therapy (Supplementary Table 2, available online). Patients whose tumors displayed high expression of CES2 exhibited a statistically significant increase in overall survival (OS) compared with patients with low CES2 expression (CES2 high vs low: log-rank P = .007, hazard ratio [HR] = 0.10, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.01 to 0.38) (Figure 4A) and had a trend towards better survival than patients with intermediate CES2 expression (CES2 high vs intermediate: log-rank P = .16, HR = 0.28, 95% CI = 0.05 to 1.61; CES2 high vs intermediate/low: log-rank P = .06, HR = 0.18, 95% CI = 0.07 to 1.06) (Figure 4A). An OS analysis restricted to resectable and borderline resectable cases showed that high CES2 expression was statistically significantly associated with improved OS compared with cases with low CES2 expression (CES2 high vs low: log-rank P = .01, HR = 0.11, 95% CI = 0.02 to 0.75) (Figure 4B) also when combined with intermediate CES2 expression cases (CES2 high vs intermediate/low: log-rank P = .02, HR = 0.14, 95% CI = 0.04 to 0.51; CES2 high vs intermediate: log-rank P = .06, HR = 0.16, 95% CI = 0.03 to 1.03) (Figure 4B). Consistently, high CES2 expression was statistically significantly associated with improved progression free survival in this set of patients (CES2 high vs low: log-rank P = .005, HR = 0.09, 95% CI = 0.01 to 0.36; CES2 high vs intermediate: log-rank P = .05, HR = 0.22, 95% CI = 0.04 to 0.97; CES2 high vs intermediate/low: log-rank P = .01, HR = 0.19, 95% CI = 0.05 to 0.67) (Supplementary Figure 7, available online). Multivariable Cox regression analysis applied to resectable and borderline resectable cases indicated that CES2 expression was, together with tumor size, the only independent predictor of OS (log-rank P = .02; HR = 0.03, 95% CI = 0.002 to 0.58) (Table 2) after stepwise selection of clinicopathological variables.

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier survival plot of pancreatic cancer patients who underwent first-line neoadjuvant FOLFIRINOX therapy stratified according to CES2 expression. A) All patients (CES2 high, n = 8; CES2 intermediate, n = 8; CES2 low, n = 6) or B) resectable and borderline resectable included in multivariable analysis (CES2 high, n = 7; CES2 intermediate, n = 6; CES2 low, n = 5) were segregated by CES2 expression as assessed trough immunohistochemical analysis. High CES2: strong staining (score 3) in 10% or more cells. Intermediate CES2: moderate staining (score 2) in 10% or more cells. Low CES2: negative or weak staining. Two-sided log-rank test was applied. CI = confidence interval; HR = hazard ratio.

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of overall survival of resectable and borderline resectable pancreatic cancer patients*

| Variable | Univariate analysis | Multivariable analysis† | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | |

| Sex | ||||

| F vs M | 0.27 (0.07 to 1.01) | .07 | ||

| Age, y | ||||

| <60 vs ≥ 60 | 0.25 (0.06 to 0.99) | .03 | ||

| Clinical stage | ||||

| Res vs BR | 0.68 (0.18 to 2.55) | .58 | ||

| CES2 | ||||

| High vs Int/Low | 0.14 (0.04 to 0.51) | .02 | 0.03 (0.002 to 0.58) | .02 |

| Grade | ||||

| Mod vs Poor | 0.73 (0.19 to 2.77) | .66 | ||

| Chemoradiation Therapy | ||||

| Yes vs No | 0.33 (0.05 to 2.15) | .10 | ||

| Nodal status | ||||

| Pos vs Neg | 2.04 (0.53 to 7.85) | .27 | ||

| Tumor size | ||||

| <3.3 vs ≥ 3.3 cm | 0.43 (0.08 to 2.38) | .21 | 0.09 (0.008 to 0.85) | .04 |

* Cox proportional hazards models. All statistical tests were two-sided. BR = borderline resectable; CI = confidence interval; HR = hazard ratio; Int = intermediate; Mod = moderate; Neg = negative; Pos = positive; Res = resectable.

† Variables included into the equation after stepwise selection.

Discussion

Our findings indicate marked heterogeneity in protein expression levels and subcellular localization of SHs among tested cancer cell types. In particular, CES2 protein expression was remarkably elevated in PDAC cell lines compared with other cancer lines. Analysis of TCGA RNA-seq and tissue microarray data showed a statistically significant higher CES2 expression in PDAC than in nontumor pancreatic tissue both at the mRNA and protein level, respectively. Western blot analysis of patient-derived xenograft tissues as well as tissue microarray analysis of PDAC tumors revealed substantial heterogeneity in CES2 levels and a subset of PDAC tissues showed high expression of CES2. Transcriptional regulation of CES2 has been reported to be mediated by the p53 pathway (31). However, our analysis revealed only a weak correlation between p53 mutation status and CES2 gene expression, suggesting the contribution of additional transcriptional regulators.

Both physiological functions and endogenous substrates of CES2 remain poorly understood. The main function of CES2 has been considered as protecting cells against harmful substances given its ability to break down xenobiotics (32,33). In our study, modulation of CES2 expression did not affect proliferation of PDAC cells. CES2 is the most efficient carboxylesterase at activating the prodrug irinotecan into its active metabolite, SN-38, a TOP1 inhibitor that is approximately 1000 times more potent than irinotecan in inducing apoptosis (34). Irinotecan is currently used as first- and second-line chemotherapy with promising activity against a number of solid tumors, including PDAC (35–38). The liver has been considered the major organ for irinotecan metabolism. However, a large intersubject variability in the hepatic expression of key irinotecan metabolizing enzymes, particularly CES2, has been observed and the extent of hepatic activation of irinotecan has been found to be partially predictive of tumor response (14,15). Local conversion of irinotecan to SN-38 occurs in human tumor tissues, and CES2 expression in cancer cells contributes to the variable responses of tumors to irinotecan chemotherapy (14,39,40). Our data raise for the first time the possibility that irinotecan could be selectively activated and its effect targeted to pancreatic tumors that express high level of CES2, enhancing the antitumor efficacy and selectivity of the drug. We observed indeed a statistically significant inverse correlation between CES2 activity and irinotecan IC50 values in PDAC cells. Consistently, CES2 stable knockdown or overexpression statistically significantly affected cell sensitivity to the prodrug. CES2 activity was moderately correlated with protein expression, suggesting the involvement of previously described post-translational mechanisms of regulation (41).

Several studies have investigated efficacy of irinotecan monotherapy in patients with previously untreated advanced pancreatic cancer or after progression on first-line gemcitabine-based therapy, yielding response rates of 7% to 27% (43–46). Results of a phase 3 clinical trial demonstrated the superiority of FOLFIRINOX, which includes irinotecan as an active ingredient, over gemcitabine in the first-line treatment of metastatic pancreatic cancer (11). Given the relatively high response rates reported in advanced disease, the potential role of FOLFIRINOX in both locally advanced and borderline resectable pancreatic cancer as a neoadjuvant treatment is currently being evaluated in several trials with promising results (30). However, molecular features of pancreatic tumors associated with response to FOLFIRINOX therapy remain to be explored. We have explored in our study the potential predictive value of CES2 expression for FOLFIRINOX treatment outcome as a first-line neoadjuvant therapy. Univariate and multivariable analysis indicated that high expression of CES2 was associated with a statistically significant increase in overall and progression-free survival compared with intermediate or low CES2 expression only in the set of patients who underwent neoandjuvant FOLFIRINOX therapy.

A limitation of our study stems from the challenge of identifying a sufficient number of patients treated with neoadjuvant FOLFIRINOX for whom tumor tissue is available for CES2 analysis and correlation with clinic-pathological characteristics and with survival. Our findings justify a prospective study to determine the value of CES2 expression and activity in predicting response to therapy with FOLFIRINOX. CES2 expression may define a subset of PDACs likely to respond to therapy that includes irinotecan. Moreover, if confirmed in a clinical trial setting our findings have implications for other prodrugs which have been reported to be activated by CES2 (47).

Funding

This work was supported by The National Cancer Institute Early Detection Network (No. U01 CA111294) and a Lustgarten Foundation award to SH.

Supplementary Material

We thank Dr. Adi F. Gazdar (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center) for providing NSCLC cell lines.

The study sponsors had no role in the design of the study, the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data, the writing of the manuscript, nor the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

The authors disclose no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Rawlings ND, Barrett AJ, Bateman A. MEROPS: the peptidase database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(Database issue):D227-D233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Simon GM, Cravatt BF. Activity-based proteomics of enzyme superfamilies: serine hydrolases as a case study. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(15):11051–11055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nomura DK, Long JZ, Niessen S, et al. Monoacylglycerol lipase regulates a fatty acid network that promotes cancer pathogenesis. Cell. 2010;140(1):49–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shields DJ, Niessen S, Murphy EA, et al. RBBP9: a tumor-associated serine hydrolase activity required for pancreatic neoplasia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(5):2189–2194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Borgono CA, Diamandis EP. The emerging roles of human tissue kallikreins in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4(11):876–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Del Rosso M, Fibbi G, Pucci M, et al. Multiple pathways of cell invasion are regulated by multiple families of serine proteases. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2002;19(3):193–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jessani N, Humphrey M, McDonald WH, et al. Carcinoma and stromal enzyme activity profiles associated with breast tumor growth in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(38):13756–13761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bachovchin DA, Cravatt BF. The pharmacological landscape and therapeutic potential of serine hydrolases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2012;11(1):52–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, et al. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(1):9–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ryan DP, Hong TS, Bardeesy N. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(11):1039–1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, et al. FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(19):1817–1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Von Hoff DD, Goldstein D, Renschler MF. Albumin-bound paclitaxel plus gemcitabine in pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(5):479–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Khanna R, Morton CL, Danks MK, et al. Proficient metabolism of irinotecan by a human intestinal carboxylesterase. Cancer Res. 2000;60(17):4725–4728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Xu G, Zhang W, Ma MK, et al. Human carboxylesterase 2 is commonly expressed in tumor tissue and is correlated with activation of irinotecan. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8(8):2605–2611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jones RP, Sutton P, Greensmith RM, et al. Hepatic activation of irinotecan predicts tumour response in patients with colorectal liver metastases treated with DEBIRI: exploratory findings from a phase II study. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2013;72(2):359–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hwang RF, Wang H, Lara A, et al. Development of an integrated biospecimen bank and multidisciplinary clinical database for pancreatic cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15(5):1356–1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tzeng CW, Fleming JB, Lee JE, et al. Defined clinical classifications are associated with outcome of patients with anatomically resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma treated with neoadjuvant therapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19(6):2045–2053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Katz MH, Marsh R, Herman JM, et al. Borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: need for standardization and methods for optimal clinical trial design. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(8):2787–2795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Katz MH, Fleming JB, Bhosale P, et al. Response of borderline resectable pancreatic cancer to neoadjuvant therapy is not reflected by radiographic indicators. Cancer. 2012;118(23):5749–5756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Beaufay H, Amar-Costesec A, Feytmans E, et al. Analytical study of microsomes and isolated subcellular membranes from rat liver. I. Biochemical methods. J Cell Biol. 1974;61(1):188–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Simplicio AL, Coroadinha AS, Gilmer JF, et al. A methodology for detection and quantification of esterase activity. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;984:309–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wang H, Zhang W, Fuller GN. Tissue microarrays: applications in neuropathology research, diagnosis, and education. Brain Pathol. 2002;12(1):95–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kim MP, Evans DB, Wang H, et al. Generation of orthotopic and heterotopic human pancreatic cancer xenografts in immunodeficient mice. Nat Protoc. 2009;4(11):1670–1680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kim MP, Truty MJ, Choi W, et al. Molecular profiling of direct xenograft tumors established from human pancreatic adenocarcinoma after neoadjuvant therapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19(Suppl 3):S395-S403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Satoh T, Hosokawa M. The mammalian carboxylesterases: from molecules to functions. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1998;38:257–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Li B, Sedlacek M, Manoharan I, et al. Butyrylcholinesterase, paraoxonase, and albumin esterase, but not carboxylesterase, are present in human plasma. Biochem Pharmacol. 2005;70(11):1673–1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lamego J, Coroadinha AS, Simplicio AL. Detection and quantification of carboxylesterase 2 activity by capillary electrophoresis. Anal Chem. 2011;83(3):881–887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Crow JA, Borazjani A, Potter PM, et al. Hydrolysis of pyrethroids by human and rat tissues: examination of intestinal, liver and serum carboxylesterases. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2007;221(1):1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Quinney SK, Sanghani SP, Davis WI, et al. Hydrolysis of capecitabine to 5’-deoxy-5-fluorocytidine by human carboxylesterases and inhibition by loperamide. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;313(3):1011–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Papadatos-Pastos D, Thillai K, Rabbie R, et al. FOLFIRINOX - a new paradigm in the treatment of pancreatic cancer. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2014;14(10):1115–1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Choi W, Cogdell D, Feng Y, et al. Transcriptional activation of the carboxylesterase 2 gene by the p53 pathway. Cancer Biol Ther. 2006;5(11):1450–1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ellinger-Ziegelbauer H, Stuart B, Wahle B, et al. Characteristic expression profiles induced by genotoxic carcinogens in rat liver. Toxicol Sci. 2004;77(1):19–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hatfield MJ, Tsurkan L, Garrett M, et al. Organ-specific carboxylesterase profiling identifies the small intestine and kidney as major contributors of activation of the anticancer prodrug CPT-11. Biochem Pharmacol. 2011;81(1):24–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kawato Y, Aonuma M, Hirota Y, et al. Intracellular roles of SN-38, a metabolite of the camptothecin derivative CPT-11, in the antitumor effect of CPT-11. Cancer Res. 1991;51(16):4187–4191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cunningham D, Pyrhonen S, James RD, et al. Randomised trial of irinotecan plus supportive care versus supportive care alone after fluorouracil failure for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Lancet. 1998;352(9138):1413–1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rougier P, Van Cutsem E, Bajetta E, et al. Randomised trial of irinotecan versus fluorouracil by continuous infusion after fluorouracil failure in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Lancet. 1998;352(9138):1407–1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Vanhoefer U, Harstrick A, Achterrath W, et al. Irinotecan in the treatment of colorectal cancer: clinical overview. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(5):1501–1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fukuoka M, Niitani H, Suzuki A, et al. A phase II study of CPT-11, a new derivative of camptothecin, for previously untreated non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10(1):16–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Uchida K, Otake K, Tanaka K, et al. Clinical implications of CES2 RNA expression in neuroblastoma. J Pediatr Surg. 2013;48(3):502–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yano H, Kayukawa S, Iida S, et al. Overexpression of carboxylesterase-2 results in enhanced efficacy of topoisomerase I inhibitor, irinotecan (CPT-11), for multiple myeloma. Cancer Sci. 2008;99(11):2309–2314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Schiel MA, Green SL, Davis WI, et al. Expression and characterization of a human carboxylesterase 2 splice variant. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;323(1):94–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Xu Y, Villalona-Calero MA. Irinotecan: mechanisms of tumor resistance and novel strategies for modulating its activity. Ann Oncol. 2002;13(12):1841–1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sakata Y, Shimada Y, Yoshino M, et al. [A late phase II study of CPT-11, irinotecan hydrochloride, in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. CPT-11 Study Group on Gastrointestinal Cancer]. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 1994;21(7):1039–1046. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wagener DJ, Verdonk HE, Dirix LY, et al. Phase II trial of CPT-11 in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer, an EORTC early clinical trials group study. Ann Oncol. 1995;6(2):129–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ueno H, Okusaka T, Funakoshi A, et al. A phase II study of weekly irinotecan as first-line therapy for patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2007;59(4):447–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ko AH, Tempero MA, Shan YS, et al. A multinational phase 2 study of nanoliposomal irinotecan sucrosofate (PEP02, MM-398) for patients with gemcitabine-refractory metastatic pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 2013;109(4):920–925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Pratt SE, Durland-Busbice S, Shepard RL, et al. Human carboxylesterase-2 hydrolyzes the prodrug of gemcitabine (LY2334737) and confers prodrug sensitivity to cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(5):1159–1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.