Abstract

Recent studies have indicated that microglia originate from immature progenitors in the yolk sac. After birth, microglial populations are maintained under normal conditions via self-renewal without the need to recruit monocyte-derived microglial precursors. Peripheral cell invasion of the brain parenchyma can only occur with disruption of the blood-brain barrier. Here, we report an autopsy case of an umbilical cord blood transplant recipient in whom cells derived from the donor blood differentiated into ramified microglia in the recipient brain parenchyma. Although the blood-brain barrier and glia limitans seemed to prevent invasion of these donor-derived cells, most of the invading donor-derived ramified cells were maintained in the cerebral cortex. This result suggests that invasion of donor-derived cells occurs through the pial membrane.

Key Words: Differentiation, Microglia, Progenitor, Stem cell, Umbilical cord blood

INTRODUCTION

Microglia, the only immunocompetent cells in the CNS, originate from progenitors derived from the yolk sac (1, 2). Studies have shown that, after birth, microglia maintain their numbers under normal conditions by self-renewal without the recruitment of monocyte-derived microglia precursors (2, 3). Although there is currently no specific marker for distinguishing resident microglia from monocyte-derived macrophages unequivocally, some studies have shown that microglia and peripheral blood cell–derived macrophages can be distinguished by the presence of surface markers, such as CCR2 and CX3CR1, even under inflammatory conditions (4, 5). Moreover, a study has shown that human Y chromosome–bearing male cells cannot differentiate into microglia in the CNS of a female host after bone marrow transplantation (6). By contrast, bone marrow stem cells and peripheral monocytes can differentiate into microglia-like cells in vitro (7, 8), suggesting that one of the most important barriers to the recruitment of microglial precursors from peripheral blood is the blood-brain barrier (BBB). Indeed, cranial irradiation or administration of the alkylating agent busulfan can disrupt the BBB, enabling bone marrow–derived cells to invade the brain parenchyma and remain there (9).

Stress was found to induce the recruitment of bone marrow–derived monocytes to the brain parenchyma in mice (10), but the results of many other studies did not clarify the origin of microglia in human adult brains. Here, we report the findings of a human autopsy case in which umbilical cord blood stem cell–derived cells differentiated into ramified microglia in the recipient brain parenchyma.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Case Report

A 51-year-old Japanese woman noticed swelling of her nasal floor at age 48 years; she was diagnosed as having natural killer/T-cell lymphoma at our hospital. She received focal radiation therapy targeting the paranasal, maxillary, and ethmoid sinuses, the parotid glands, and the right and left orbits (40 Gy), and Novalis Shaped Beam Surgery (12 Gy). After radiation therapy, she received 3 courses of DeVIC (dexamethasone, etoposide, ifosfamide, and carboplatin) chemotherapy. After treatment, she achieved complete remission; 2 months after chemotherapy, she received a cord blood stem cell transplant (CBSCT) from a male donor with whom she had 2 human leukocyte antigen (HLA) mismatches (donor: A*31:01, A*33:03, B*51:01, B*40:03, DRB1*08:02, DRB1*14:05; recipient: A*31:01, A*02:01, B*51:01, B*40:02, DRB1*08:02, DRB1*14:05). Acute graft-versus-host disease was mild and well controlled by oral administration of tacrolimus. Four months after CBSCT, the patient presented with shingles of the right 12th thoracic segment and was treated with acyclovir; however, herpes zoster developed into cervical myelitis. Combined therapy with steroid pulse treatment and intravenous administration of gamma globulin was effective. Two years after CBSCT, she experienced muscle weakness and sensory disturbance of the lower extremities. Her symptoms gradually worsened, although steroid pulse treatment provided slight improvement. Positron emission tomography showed tumor relapse in the liver. Her general condition worsened, and her consciousness deteriorated. In addition, she was given a single intrathecal administration of methotrexate (15 mg) 2 weeks before her death. She died 29 months after CBSCT.

A general autopsy was performed 3 hours after death. Neuropathologic examination demonstrated the presence of lymphoma in the spinal cord (including a lesion at C5) and inflammation of the left medulla, with no evidence of tumor in the cerebrum and cerebellum.

Immunohistochemistry

The brain was fixed in 10% buffered formalin. Multiple tissue blocks were embedded in paraffin, and 6-μm sections were cut and immunostained using a Liquid DAB+ Substrate Chromogen System kit (DAKO, Tokyo, Japan) and a TMB Peroxidase Substrate Kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). The sections were counterstained with hematoxylin. Primary antibodies included rabbit polyclonal anti-Iba1 (1:8000; Wako, Osaka, Japan), anti–glial fibrillary acidic protein (1:10000; Sigma, Tokyo, Japan), anti-CX3CR1 (1:100; Abcam, Tokyo, Japan), rabbit monoclonal anti-CCR2 (1:4000; Abcam), and mouse monoclonal anti–HLA-A2 (1:100; MBL, Nagoya, Japan). Appropriate antigen retrieval methods were applied to each primary antibody.

In Situ Hybridization

We used a commercial kit to identify the Y chromosome. Briefly, 5-μm sections from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded blocks were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and predigested with 1 drop of pepsin solution. The sections were incubated with hybridization solution containing ZytoDot CEN Yq12 Probe (ZytoVision, Bremerhaven, Germany) overnight at 37°C. The ZytoDot CISH Implementation Kit (ZytoVision) was used to visualize hybridization products. After staining, the slides were double-stained with anti-Iba1 antibody.

RESULTS

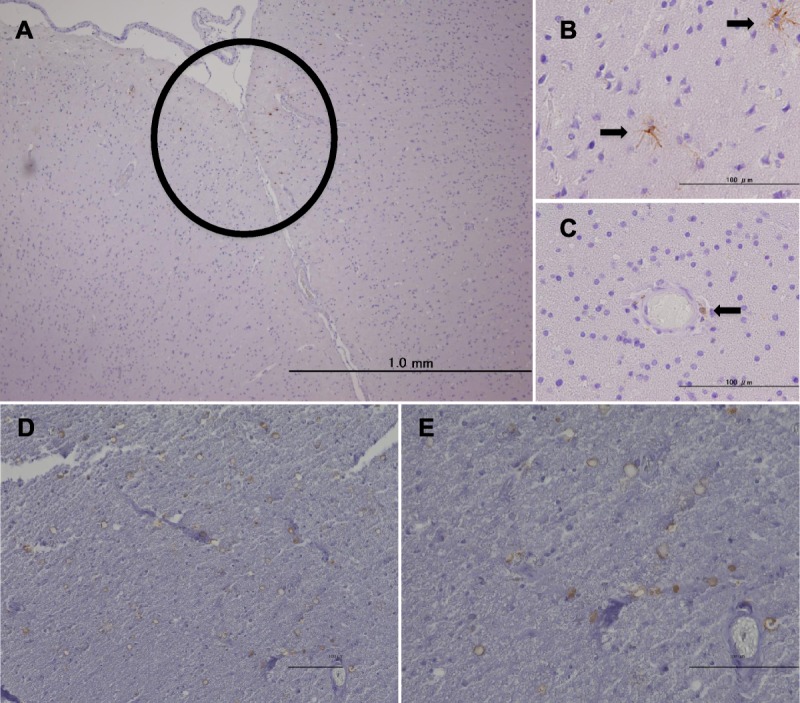

To study the migration of donor-derived cells into the patient’s brain, we performed immunohistochemistry with anti–HLA-A2 antibody, which could distinguish donor-derived cells from host cells. Interestingly, donor-derived HLA-A2–positive cells were found in the cortex and around vessels (Figs. 1A–C). HLA-A2–positive cells often seemed to have accumulated in cortical regions (Fig. 1A); very few were observed in the deep white matter. Invading HLA-A2–positive cells in the cortical region had a ramified morphology similar to that of microglia (Fig. 1B). By contrast, immunohistochemical staining of the C5 lesion with anti–HLA-A2 antibodies showed more HLA-A2–positive cells in the parenchyma (Figs. 1D, E). Moreover, HLA-A2–positive cells in that area were round or ring-shaped but did not have a ramified morphology (Figs. 1D, E).

FIGURE 1.

Immunohistochemistry for HLA-A2 with hematoxylin counterstaining. (A) HLA-A2–positive cells accumulate in the cerebral cortex (brown cells within the circle). (B) HLA-A2–positive cells with ramified morphology (arrows). (C) A round HLA-A2–positive cell around a vessel (arrow). HLA-A2–positive cells with a round or ring morphology in the C5 lesion of the spinal cord at lower magnification (D) and at higher magnification (E). Scale bar = 100 μm.

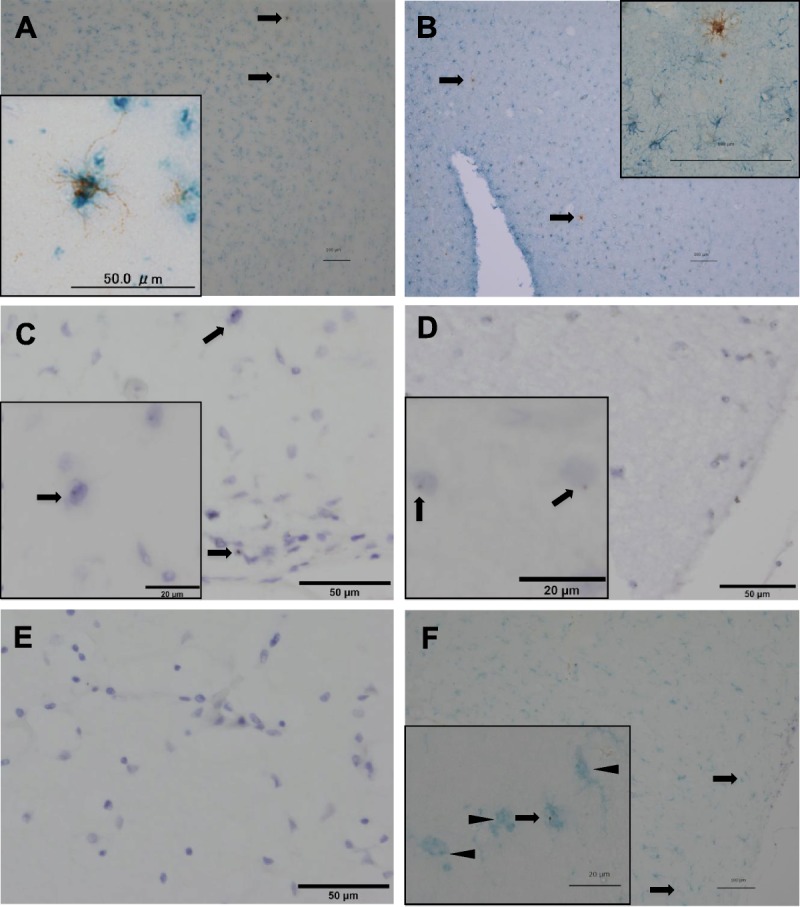

We next performed double staining to investigate the differentiation of graft cells into microglia or astrocytes. HLA-A2–positive cells stained positive for Iba1, which is representative of microglia (Fig. 2A), but not for glial fibrillary acidic protein, which is specific for astrocytes (Fig. 2B). Because these results suggested that graft cells differentiated into microglia, we also performed in situ hybridization with anti-Yq12 probes. Although most of the cells in the male positive control sample showed a brown dot in their nuclei, whereas cells in the female negative control sample had no brown dot in their nuclei, only a few cells in the transplant recipient sample had a brown dot in their nuclei, indicating Y chromosome–positive cells from the male donor (Figs. 2C–E). Moreover, in situ hybridization with anti-Yq12 probes after immunohistochemistry with anti-Iba1 antibodies showed that Y chromosome–positive cells from the male donor were Iba1-positive (Fig. 2F).

FIGURE 2.

Double staining of donor-derived cells by immunohistochemistry (A, B) and in situ hybridization (C–F). (A) Double staining of donor-derived cells with anti–HLA-A2 antibody (brown) and anti-Iba1 antibody (blue). Inset: The image at higher magnification. (B) Double staining of donor-derived cells with anti–HLA-A2 antibody (brown) and anti–glial fibrillary acidic protein antibody (blue). Inset: The image at higher magnification. (C) In situ hybridization of the patient sample using anti-Yq12 probes (brown dot) with counterstaining of nuclei by Mayer hematoxylin solution. Arrows show Yq12-positive cells indicating donor origin. Inset: the image at higher magnification. (D) In situ hybridization of the sample from the positive control. Inset: the image at higher magnification. Arrows show Yq12-positive cells. (E) In situ hybridization of the sample from the negative control. (F) Double staining of donor-derived cells using anti-Yq12 probes (brown dot) and anti-Iba antibody (blue). Arrows show double-positive cells indicating donor origin; arrowheads show Iba1-positive and Yq12-negative cells indicating host origin. Inset: the image at higher magnification. Scale bar = 100 μm.

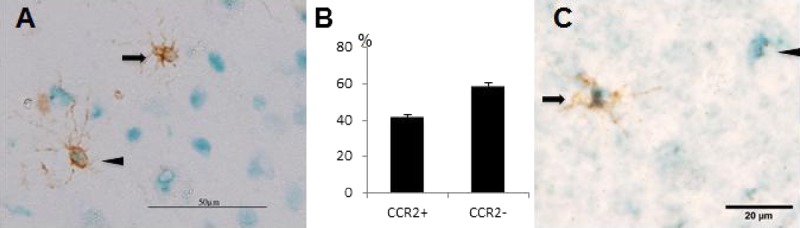

Because CCR2 and CX3CR1 are very important for distinguishing resident microglia from monocyte-originating microglia-like cells, we next explored the expression of CCR2 and CX3CR1 in HLA-A2–positive cells. Approximately 60% of HLA-A2–positive cells were CCR2-negative, and most of the invading HLA-A2–positive cells were CX3CR1-positive (Figs. 3A–C).

FIGURE 3.

Double staining of donor-derived cells by immunohistochemistry. (A) Double staining of donor-derived cells with anti–HLA-A2 antibody (brown) and anti-CCR2 antibody (blue). Arrows indicate CCR2-negative and HLA-A2–positive cells; arrowheads indicate double-positive cells. (B) Migrated HLA-A2–positive cells were counted in 3 independent sections; the frequency of CCR2-positive cells and CCR2-negative cells is shown in the bar graph. Bars indicate mean ± SD. (C) Double staining of donor-derived cells with anti–HLA-A2 antibody (brown) and anti-CX3CR1 antibody (blue). Arrow indicates a double-positive cell indicating donor origin; arrowhead indicates a CX3CR1-positive and HLA-A2–negative cell indicating host origin.

DISCUSSION

This case shows that umbilical cord blood stem cell–derived precursors can differentiate into CX3CR1-positive, CCR2-negative, and Iba1-positive ramified microglia even without brain irradiation, whereas previous studies did not find that donor-derived cells entering the CNS parenchyma can transform into microglia (6).

Clinical conditions between our case and previous cases differed. First, our patient had herpes zoster myelitis and relapse in the spinal cord, perhaps including meningitis of the whole brain. Moreover, a lesion of the cortex in the left midfrontal gyrus (data not shown) may indicate that there had been a trace of herpes zoster virus–induced encephalitis. Indeed, donor-derived cells can enter the recipient brain and differentiate into microglia after severe streptococcal meningitis (11). Bacterial meningitis often destroys the BBB and pial membrane, thereby allowing donor-derived cells to enter the CNS parenchyma. Even after meningitis, we often observe abnormal meningeal findings. Massengale et al (12) found that no donor-derived cells enter the CNS parenchyma even with brain injury. Ajami et al (13) reported that infiltrating monocytes at an inflammatory site have a short life span and do not contribute to the resident microglia pool. Although it is possible that diffuse leptomeningeal involvement by lymphoma may have occurred at the time of clinical relapse in the spinal cord, our case showed no trace of meningitis at autopsy.

The effects of chemotherapy and focal radiation therapy should also be considered. Our finding that donor-derived cells had not invaded the deep white matter of the recipient is consistent with the possibility that there was no brain irradiation, as has been shown in head-shielded mouse models (14). Indeed, we rarely observed donor-derived microglia in the deep white matter, thalamus, and basal ganglia, although we found donor-derived perivascular cells; however, inflammation of the left medulla (as reported in the final diagnosis) might have been caused by the direct effects of focal irradiation. Because the alkylating agent busulfan can cause bone marrow–derived cells to penetrate the brain parenchyma (9), DeVIC chemotherapy may also disrupt the BBB. However, donor-derived ramified cells were rare in the deep region of the brain, suggesting that the BBB in our patient was sufficiently intact to prevent invasion of donor-derived cells. Although Unger et al (6) did not provide information pertaining to irradiation and chemotherapy, all patients likely received aggressive chemotherapy as pretreatment before bone marrow transplantation for leukemia or lymphoma. Nevertheless, no donor-derived cells were found to have differentiated into ramified microglia. Because donor-derived cells did not invade the deep white matter of the recipient in our case, we consider the possibility that chemotherapy had minimal effects. Moreover, even if a single intrathecal administration of methotrexate had disrupted the BBB, we consider it highly improbable that invading cells differentiated into CX3CR1-positive, CCR2-negative, and Iba1-positive ramified microglia (i.e. indicating the resting form) within 2 weeks.

In conclusion, we report an autopsy case in which cells derived from transplanted umbilical cord blood differentiated into ramified microglia in the host brain parenchyma. Although the BBB and glia limitans seem to have prevented the invasion of these donor-derived cells, most of the invading donor-derived ramified cells remained in the cortical zone. This result suggests that the invasion of donor-derived cells occurs through the pial membrane.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the patient and her family for consenting to this work and publication. We also thank Dr. Mukai and Dr. Ishida for making the final pathologic diagnosis.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ginhoux F, Greter M, Leboeuf M, et al. Fate mapping analysis reveals that adult microglia derive from primitive macrophages. Science 2010; 330: 841– 45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ajami B, Bennett JL, Krieger C, et al. Local self-renewal can sustain CNS microglia maintenance and function throughout adult life. Nat Neurosci 2007; 10: 1538– 43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Prinz M, Tay TL, Wolf Y, et al. Microglia: Unique and common features with other tissue macrophages. Acta Neuropathol 2014; 128: 319– 31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Saederup N, Cardona AE, Croft K, et al. Selective chemokine receptor usage by central nervous system myeloid cells in CCR2-red fluorescent protein knock-in mice. PLoS One 2010; 5: e13693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yamasaki R, Lu H, Butovsky O, et al. Differential roles of microglia and monocytes in the inflamed central nervous system. J Exp Med 2014; 211: 1533– 49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Unger ER, Sung JH, Manivel JC, et al. Male donor-derived cells in the brains of female sex–mismatched bone marrow transplant recipients: A Y-chromosome specific in situ hybridization study. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 1993; 52: 460– 70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Noto D, Takahashi K, Miyake S, et al. In vitro differentiation of lineage-negative bone marrow cells into microglia-like cells. Eur J Neurosci 2010; 31: 1155– 63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Noto D, Sakuma H, Takahashi K, et al. Development of a culture system to induce microglia-like cells from haematopoietic cells. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 2014; 40: 697– 713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kierdorf K, Katzmarski N, Haas CA, et al. Bone marrow cell recruitment to the brain in the absence of irradiation or parabiosis bias. PLoS One 2013; 8: e58544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wohleb ES, Powell ND, Godbout JP, et al. Stress-induced recruitment of bone marrow–derived monocytes to the brain promotes anxiety-like behavior. J Neurosci 2013; 33: 13820– 33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Djukic M, Mildner A, Schmidt H, et al. Circulating monocytes engraft in the brain, differentiate into microglia and contribute to the pathology following meningitis in mice. Brain 2006; 129: 2394– 403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Massengale M, Wagers AJ, Vogel H, et al. Hematopoietic cells maintain hematopoietic fates upon entering the brain. J Exp Med 2005; 201: 1579– 89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ajami B, Bennett JL, Krieger C, et al. Infiltrating monocytes trigger EAE progression, but do not contribute to the resident microglia pool. Nat Neurosci 2011; 14: 1142– 49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mildner A, Schmidt H, Nitsche M, et al. Microglia in the adult brain arise from Ly-6ChiCCR2+ monocytes only under defined host conditions. Nat Neurosci 2007; 10: 1544– 53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]