Abstract

Patient: Female, 73

Final Diagnosis: Giant liver hemangioma

Symptoms: Abdominal discomfort • abdominal enlargement • Icterus

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: Enucleation after embolization of liver failure-causing giant liver

Specialty: Surgery

Objective:

Unusual clinical course

Background:

Hepatic hemangioma is a congenital tumor of the mesenchymal tissues of the liver. While typically benign, these tumors can occasionally grow to sufficient size to cause a number of symptoms, including pain, severe hepatic dysfunction, or, rarely, consumptive coagulopathy. In such instances, surgical treatment may be warranted.

Case Report:

We present a case of a symptomatic giant hepatic hemangioma in an elderly patient who presented with impending liver failure. She was successfully treated with a combination of surgical enucleation and liver resection after preoperative arterial embolization. We also provide a brief discussion of current treatment options for giant hepatic hemangiomas.

Conclusions:

Early referral to experienced surgical centers before the onset of dire complications such as severe hepatic dysfunction and liver failure is recommended.

MeSH Keywords: Embolization, Therapeutic; Hemangioma, Cavernous; Liver Failure, Acute; Surgical Procedures, Elective

Background

Hepatic hemangioma is a congenital tumor of the mesenchymal tissues of the liver. While typically benign, these tumors can occasionally grow to sufficient size to cause a number of symptoms, including pain, severe hepatic dysfunction, or, rarely, a consumptive coagulopathy (Kasabach-Merritt syndrome). In such instances, surgical treatment may be warranted. While multiple surgical techniques are described in the literature, enucleation is considered the safest and most effective approach. However, in the case of unusually large tumors, a multistage approach with a goal of pre-operative reduction in tumor size and vascularity with embolization may be advantageous. We present a case of a symptomatic giant hepatic hemangioma in an elderly patient that was successfully treated with combination of surgical enucleation and liver resection after preoperative arterial embolization. We also provide a brief discussion of current treatment options for giant hepatic hemangiomas.

Case Report

The patient was a 73-year-old African American woman with history of atrial fibrillation, hypothyroidism, diabetes, and hypertension. She had been diagnosed with a hepatic hemangioma approximately 35 years ago when she underwent an abdominal hysterectomy. She was managed conservatively and remained asymptomatic over the subsequent decades. She presented to our Emergency Department with recent onset of scleral icterus and increasing intensity of dull right upper-quadrant pain. This was accompanied by 1 week of light-colored stools and dark urine. Physical examination at presentation was significant for scleral icterus and a firm, distended, non-tender abdomen. The patient’s Karnofsky Performance Scale Index was 70%.

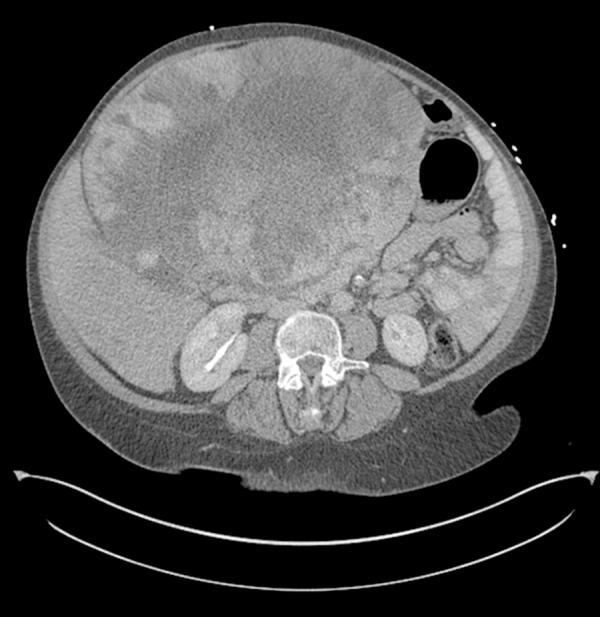

Laboratory evaluation revealed elevated liver enzymes (AST 840 U/L, ALT 515 U/L), hyperbilirubinemia (total bilirubin 14.5 md/dL, conjugated bilirubin 12.2 mg/dL), and coagulopathy (INR 3.1). Selected laboratory values are shown in Table 1. Computerized tomography of the abdomen showed multiple hypo-attenuating masses with peripheral nodular enhancement throughout the liver, suggestive of hemangiomas (Figure 1). The largest was located in the left hepatic lobe and measured 26.0×18.0×27.0 cm, with 2 other hemangiomas in the right lobe measuring 7.0×6.0 and 3.0×3.0 cm. The centers of these masses contained some hypodense areas, consistent with possible necrosis. There were no specific areas of biliary ductal dilation.

Table 1.

Selected laboratory values.

| Laboratory Value | Reference range | Admission | POD #1 | POD #3 | At 4-months |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liver function tests | |||||

| Aspartate aminotransferase (unit/L) | 0–50 | 521 | 320 | 104 | 35 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (unit/L) | 0–50 | 344 | 171 | 81 | 25 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (unit/L) | 0–120 | 132 | 77 | 49 | 115 |

| Bilirubin, total (mg/dL) | 0–1.3 | 15.7 | 12.7 | 9 | 0.5 |

| Bilirubin, conjugated (mg/dL) | 0.0–0.4 | 11.9 | 10.2 | 7.3 | 0.2 |

| Protein, total (g/dL) | 6.4–8.5 | 7.2 | 5.6 | 5.4 | 7.6 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.7–5.2 | 3.2 | 2.9 | 3.2 | 4.2 |

| Hematology | |||||

| White-cell count (109 cells/L) | 3.9–11.7 | 3 | 3.5 | 7.1 | 4 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 12–15 | 12 | 10.9 | 8.1 | 12.9 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 34.8–45 | 36.4 | 31.3 | 22.9 | 39.1 |

| Platelets (109 cells/L) | 172–440 | 149 | 157 | 92 | 171 |

| Coagulation | |||||

| Prothrombin time (seconds) | 12–14.6 | 17 | 17.2 | 16.1 | 13.3 |

| Activated prothrombin time (seconds) | 25–36 | – | 33 | 37 | – |

| International normalized ratio | 1 | 3.1 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 1 |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dL) | 200–450 | – | 298 | 484 | – |

POD – post-operative day.

Figure 1.

Computed tomography of the abdomen with large left lobe mass with compression of the right lobe.

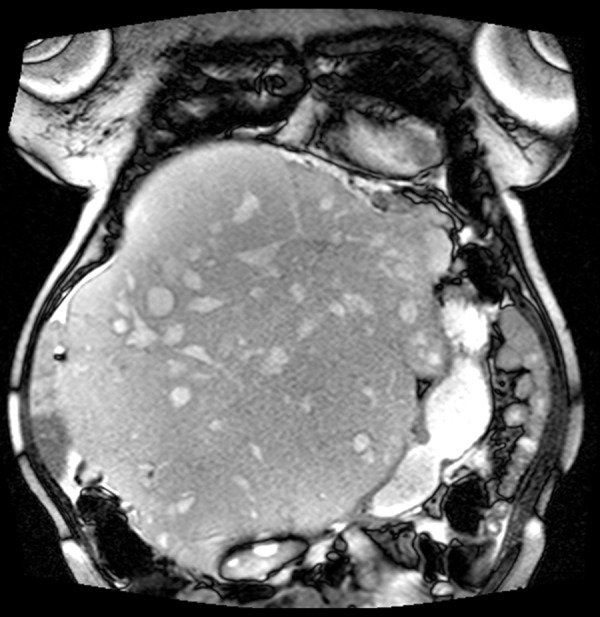

MRI of the abdomen (Figure 2) confirmed the presence of multiple masses in the liver with low T1 and high T2 attenuation, consistent with a diagnosis of massive hepatic hemangioma extending into the pelvis. Due to the patient’s advanced age, multiple medical co-morbidities, coagulopathy, and massive size of the tumor, hospice care at an outside hospital had been suggested. A transplant surgery opinion was sought by the consulting hepatologist at our center. A lengthy discussion was held with the patient and her family regarding risks and possible complications of surgical intervention. The patient decided against palliative care and consented to a high-risk surgical intervention.

Figure 2.

Magnetic resonance imaging of the abdomen showing the cranio-caudal extent of the massive cavernous hemangioma.

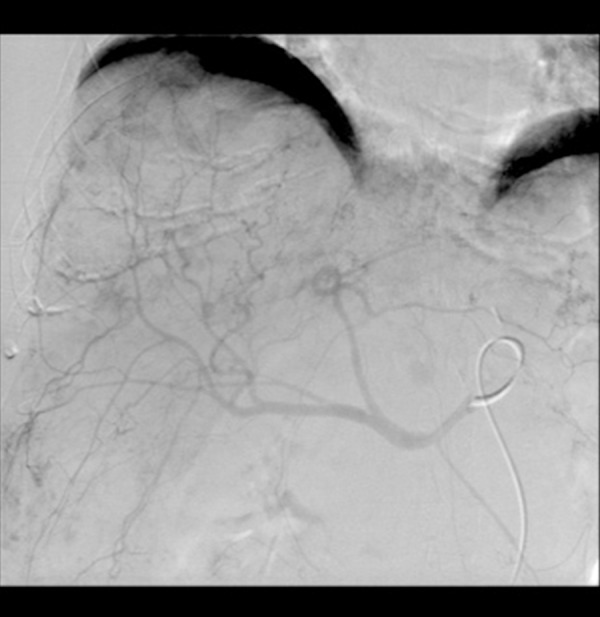

The patient underwent hepatic angiography (Figure 3) prior to the planned resection. An uncomplicated partial embolization of the giant hemangioma via the left hepatic artery using 2 vials of 500–700 micron diameter embospheres was performed. Two days later she was taken to the operating room. Our liver transplant team, including an anesthesiologist and support staff, participated in this surgery. Provisions were made for backbench ex vivo perfusion of the liver, if required. A massive transfusion protocol was set-up and a veno-venous bypass team was placed on standby. Surgical exposure of the giant hemangioma was obtained via a midline incision extending from the xiphoid process to the pubic symphysis with transverse extension to the right just above the level of the umbilicus (Figure 4). Lysis of omental adhesions revealed compression of the right lobe of the liver and near complete atrophy of segments II and III. The tumor was gently rotated to the right and an umbilical tape was used to encircle the hepatic hilum in case a Pringle maneuver was necessary.

Figure 3.

Pre-operative hepatic angiography. The left hepatic artery feeding the massive hemagioma was embolized successfully to achieve reduction in tumor size.

Figure 4.

Gross view of the massive hemangioma involving the entire left lobe. The operator’s gloved fingers are resting over the patient’s supra-pubic area. The thin, compressed right lobe is barely visible.

A Cavitron Ultrasonic Surgical Aspirator (CUSA, Valleylab, USA) was used to divide a thin rim of segment IV, which was bridging across the anterior aspect of the tumor. This allowed access to an avascular plane between the compressed right lobe and the hemangioma. Monopolar coagulation and CUSA were then used to for enucleation of the hemangioma without any significant blood loss. The left hepatic vein was isolated. Ligation of the left hepatic artery, hepatic duct, and portal vein allowed mobilization of the posterior aspect of the hemangioma. The left hepatic vein and a thin rim of segments II and III were divided using a 2.5-mm endostapler (Autosuture™ GIA™ UNIVERSAL stapler, Norwalk, CT, USA). The specimen was sent for histopathological examination. The patient was extubated after 24 h, had an uneventful recovery, and was discharged home on post-operative day 7.

Estimated blood loss during surgery was approximately 900 mL. The patient received 1 unit of packed red cells, 1 dose of platelets, 2 doses of fresh frozen plasma, and 350 mL of autologous blood transfusion (Cell Saver® Elite®, Hemonetics, USA). The specimen weighed 5.5 kg, with approximate size of 30 cm by 20 cm (Figure 5). The histopathological examination confirmed a number of cavernous hemangiomas with infarction and degenerative changes, with a pattern of bilirubinostasis in the resected liver.

Figure 5.

Specimen on the back table showing the massive cavernous hemangioma weighing 12.14 pounds (5.5 kg). The maximum dimension of the tumor was 30 cm.

Liver enzymes and hyperbilirubinemia completely normalized by approximately 4 months after surgery (Table 1). A follow-up abdominal MRI performed 2 years after the surgery revealed small, stable hemangiomas (the largest measuring 6.0 cm in diameter) in the residual right lobe of the liver. The patient continues to do well and is asymptomatic nearly 3 years after her surgery.

Discussion

We present a case of a massive cavernous hepatic hemangioma causing compression and impending liver failure in a septuagenarian female that was successfully managed using a combination of enucleation and hepatic parenchymal resection after pre-operative embolization. This case highlights the fact that size of hemangioma and patient age should not automatically exclude them from consideration for surgical management. Timely referral of patients to a center with liver resection/transplantation capabilities could prove life-saving.

Hepatic hemangiomas are common, typically benign, lesions arising from the mesenchymal tissues of the liver [1]. Lesions are typically categorized by size, with the distinction of “giant” being reserved for those greater than 4 cm in diameter [1]. Histologically, they are characterized by cavernous, blood-filled sinuses, which are lined by vascular endothelium. They are typically considered to be congenital rather than a neoplastic processes, with poorly understood biology in regards to growth patterns and factors. Estimates of incidence in the general population range from 0.6 to 7% [2], and occur predominantly in the female population (3:1) [1]. There is a known association between lesion size and estrogen/progesterone levels, with lesion growth observed during pregnancy and in conjunction with the use of oral contraceptives and hormone replacement therapies [1].

Hepatic hemangiomas are typically managed expectantly because they carry a very low risk for complications such as progression to malignant disease or rupture [1]. The indications for operative management include pain/discomfort (22.5%), liver or abdominal organ dysfunction related to mass effect (32%, typically manifested by impaired hepatic function), suspicion of malignancy or inability to definitively diagnose a lesion as a hemangioma (20%), and a syndrome of consumptive coagulopathy known as Kasabach-Merritt syndrome (7.5%) [1].

First described in 1940 [2], Kasabach-Merritt syndrome is a thrombocytopenic purpura associated with an enlarging hemangioma. The typical presentation is profound thrombocytopenia (often less than 20×109 platelets/L), accompanied by consumptive coagulopathy and intravascular hemolysis reminiscent of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). The proposed pathogenesis of this DIC is related to platelet activation and clumping when they come in contact with the abnormal endothelium of the tumor, leading to turbulent blood flow, shearing stresses, and hemolysis. Mainstays of therapy are primarily centered around obliteration of the tumor and its aberrant endothelium, which can be achieved by a number of techniques, including excision, embolization, radiotherapy, corticosteroids, or simply external compression with obliteration of the vascular space.

In our patient the main indication for surgery was evolving liver failure due to mass effect caused by the enormous hemangioma. Our choice of therapy and operative approach was based on the prior experience of a number of surgeons. Therapeutic options as described in the literature included ablation, enucleation, partial hepatic resection, and total hepatectomy with liver transplant [3–6]. While most case reports suggested enucleation (if technically feasible) as superior/non-inferior to hepatic resection [7–9], evidence supporting the role of preoperative angiography and ablation is less clear. A number of case reports [10,11] made attempts to use angiography as a primary therapy, with varying degrees of success. However, many reports [1,12] described the control of the hepatic pedicle, with periodic clamping, as a method to temporarily decrease tumor size in an effort to facilitate dissection and isolation of vessels supplying it.

In this case, we combined the techniques of embolization and periodic pedicle clamping to achieve the desired result – pre-operative angiographic left hepatic arterial embolization – to provide some degree of tumor size reduction (but not necrosis), and hepatic pedicle clamping for further reduction of tumor size or rapid in-flow control should the need arise. Most giant hemangiomas are most safely removed by enucleation when a good plane can be found between the tumor and liver parenchyma. With this ‘super’ giant cavernous hemangioma, we employed a combination technique of partly enucleating and partly resecting the liver parenchyma to achieve the desired outcomes with minimal blood product requirements. Additionally, a back table, as would be utilized during liver transplantation, was prepared in the event that uncontrollable hemorrhage mandated total hepatectomy with ex-vivo liver perfusion, tumor resection, and implantation of the right lobe.

Conclusions

Our experience with this patient serves to reinforce previously published reports suggesting the feasibility of safely resecting/enucleating giant hepatic hemangiomas. While technically challenging, these procedures can be accomplished successfully provided that sufficient support structure and facilities are available. We recommend that patients with giant, symptomatic hepatic cavernous hemangiomas are best served by early referral to experienced surgical centers before the onset of dire complications such as severe hepatic dysfunction or Kasabach-Merritt syndrome.

References:

- 1.Giuliante F, Ardito F, Vellone M, et al. Reappraisal of surgical indications and approach for liver hemangioma: single-center experience on 74 patients. Am J Surg. 2011;201(6):741–48. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2010.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hall GW. Kasabach-Merritt syndrome: pathogenesis and management. Br J Haematol. 2001;112(4):851–62. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.02453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Concejero AM, Chen CL, Chen TY, et al. Giant cavernous hemangioma of the liver with coagulopathy: adult Kasabach-Merritt syndrome. Surgery. 2009;145(2):245–47. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2007.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yildiz S, Kantarci M, Kizrak Y. Cadaveric liver transplantation for a giant mass. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(1):e10–1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vagefi PA, Klein I, Gelb B, et al. Emergent orthotopic liver transplantation for hemorrhage from a giant cavernous hepatic hemangioma: case report and review. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15(1):209–14. doi: 10.1007/s11605-010-1248-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumashiro Y, Kasahara M, Nomoto K, et al. Living donor liver transplantation for giant hepatic hemangioma with Kasabach-Merritt syndrome with a posterior segment graft. Liver Transpl. 2002;8(8):721–24. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2002.33689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hochwald SN, Blumgart LH. Giant hepatic hemangioma with Kasabach-Merritt syndrome: is the appropriate treatment enucleation or liver transplantation? HPB Surg. 2000;11(6):413–19. doi: 10.1155/2000/25954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhong L, Men TY, Yang GD, et al. Case report: living donor liver transplantation for giant hepatic hemangioma using a right lobe graft without the middle hepatic vein. World J Surg Oncol. 2014;12(1):83. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-12-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fu XH, Lai EC, Yao XP, et al. Enucleation of liver hemangiomas: is there a difference in surgical outcomes for centrally or peripherally located lesions? Am J Surg. 2009;198(2):184–87. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2008.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seo HI, Jo HJ, Sim MS, Kim S. Right trisegmentectomy with thoracoabdominal approach after transarterial embolization for giant hepatic hemangioma. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15(27):3437. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.3437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vassiou K, Rountas H, Liakou P, et al. Embolization of a giant hepatic hemangioma prior to urgent liver resection. Case report and review of the literature. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2007;30(4):800–2. doi: 10.1007/s00270-007-9057-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baer HU, Dennison AR, Mouton W, et al. Enucleation of giant hemangiomas of the liver. Technical and pathologic aspects of a neglected procedure. Ann Surg. 1992;216(6):673–76. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199212000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]