Abstract

Type II toxin-antitoxin (TA) modules are thought to mediate stress-responses by temporarily suppressing protein synthesis while cells redirect transcription to adapt to environmental change. Here, we show that YoeB, a ribosome-dependent mRNase toxin, is activated in Escherichia coli cells grown at elevated temperatures. YoeB activation is dependent on Lon protease, suggesting that thermal stress promotes increased degradation of the YefM antitoxin. Though YefM is efficiently degraded in response to Lon overproduction, we find that Lon antigen levels do not increase during heat shock, indicating that another mechanism accounts for temperature-induced YefM proteolysis. These observations suggest that YefM/YoeB functions in adaptation to temperature stress. However, this response is distinct from previously described models of TA function. First, YoeB mRNase activity is maintained over several hours of culture at 42°C, indicating that thermal activation is not transient. Moreover, heat-activated YoeB does not induce growth arrest nor does it suppress global protein synthesis. In fact, E. coli cells proliferate more rapidly at elevated temperatures and instantaneously accelerate their growth rate in response to acute heat shock. We propose that heat-activated YoeB may serve a quality control function, facilitating the recycling of stalled translation complexes through ribosome rescue pathways.

Keywords: A-site mRNA cleavage, mRNA turnover, ribosome pausing, RNase II, tmRNA

Introduction

In Escherichia coli, prolonged translational arrest often leads to mRNA degradation into the ribosome A site (Hayes and Sauer 2003; Sunohara et al. 2004; Li et al. 2006, 2008; Garza-Sánchez et al. 2008). This A-site mRNA cleavage activity results in truncated A-site codons, which prevent further decoding and produce stalled translation complexes. Such non-productive ribosomes are “rescued” by at least three quality control systems in bacteria (Janssen and Hayes 2012). tmRNA-SmpB mediates the primary ribosome rescue pathway, and this system is found in all eubacteria and some plastids (Tu et al. 1995; Keiler et al. 1996, 2000; Gueneau de Novoa and Williams 2004). tmRNA is a stable RNA with both transfer-RNA and messenger-RNA functions and recycles stalled ribosomes in a process termed trans-translation. During trans-translation, tmRNA-SmpB enters the ribosome A site, and the nascent peptide is transferred to alanine-charged tmRNA. The truncated message is then released from the ribosome and translation resumes using a short open reading frame within tmRNA. In this manner, tmRNA provides a stop codon in trans, thereby allowing normal translation termination and ribosome recycling (Hayes and Keiler 2010). More recently, two alternative ribosome rescue pathways have been identified. ArfA (alternative rescue factor A) was discovered in a synthetic lethal screen for genes that are essential for the viability of mutants that lack tmRNA (Chadani et al. 2010). ArfA is a small peptide that binds the ribosome and allows release factor-2 to catalyze nascent chain release in the absence of an A-site stop codon (Chadani et al. 2012; Shimizu 2012). YaeJ (ArfB) is a release factor homolog that lacks the canonical stop codon recognition domain (Baranov et al. 2006; Hayes and Keiler 2010). Thus, YaeJ can bind the ribosome A site in the absence of a stop codon and catalyze nascent peptide release (Chadani et al. 2011; Handa et al. 2011; Gagnon et al. 2012; Feaga et al. 2014). Because A-site cleavage produces nonstop transcripts in response to translational pausing, this nuclease activity is thought to function in molecular quality control by facilitating ribosome rescue (Hayes and Sauer 2003; Sunohara et al. 2004).

In E. coli there are at least two enzymes, RelE and YoeB, which have ribosome-dependent A-site nuclease activity (Pedersen et al. 2003; Feng et al. 2013). RelE and YoeB are encoded by type II toxin–antitoxin (TA) modules together with cognate antitoxins that specifically neutralize nuclease activity. These mRNases have been termed “toxins” because their activities inhibit cell growth and can lead to cell death under some circumstances. In general, toxins are activated under stress or other conditions that prevent continued antitoxin synthesis. Antitoxins are labile to proteolysis and their degradation liberates the cognate toxins to exert growth inhibition activities. The physiological functions of TA systems remain controversial. They have been proposed to play roles in stress-response, persistence, genomic stability and programmed cell death (Engelberg-Kulka et al. 2005; Gerdes et al. 2005; Magnuson 2007; Tsilibaris et al. 2007; Nariya and Inouye 2008; Maisonneuve et al. 2011). Though RelE and YoeB have the potential to catalyze A-site mRNA cleavage during translational arrest, mutants lacking these enzymes and other known toxins retain A-site cleavage activity (Hayes and Sauer 2003; Sunohara et al. 2004; Garza-Sánchez et al. 2009; Janssen et al. 2013). Thus, the identity of the A-site nuclease is unknown, but it remains possible that an unidentified toxin catalyzes cleavage in response to the stress of translational pausing.

Though the A-site nuclease has not been identified, the phenomenon clearly requires the 3′-to-5′ exoribonuclease activity of RNase II (Garza-Sánchez et al. 2009; Janssen et al. 2013). In Δrnb mutants, which lack RNase II, prolonged translational arrest produces transcripts that are truncated 12 nucleotides downstream of the ribosome A site (Garza-Sánchez et al. 2009; Janssen et al. 2013). This position corresponds to the “toeprint” of the paused ribosome, suggesting that the ribosome physically blocks further mRNA degradation into the A site. However, purified RNase II only degrades mRNA to the +18 position (with respect to the A-site codon) when incubated with translation complexes in vitro (Garza-Sánchez et al. 2009). Moreover, the deeply recessed active site of RNase II is incompatible with the ability to directly catalyze A-site mRNA cleavage (Frazao et al. 2006; Zuo et al. 2006). Because RNase II is unable to degrade the A-site codon itself, the enzyme must play an indirect role in A-site mRNA cleavage. One possibility is that RNase II-mediated mRNA degradation to the 3′-edge of the ribosome is required for subsequent degradation into the A site by an unknown nuclease. This model is supported by experiments showing that secondary structures placed on the 3′-side of paused ribosomes are sufficient to inhibit RNase II activity and also block A-site cleavage (Garza-Sánchez et al. 2009).

We previously reported that A-site mRNA cleavage is suppressed in response to heat shock at 42°C (Garza-Sánchez et al. 2009). This observation suggests that A-site nuclease activity is heat labile, and therefore we revisited these experiments in an effort to identify the enzyme responsible. Although acute heat shock temporarily inhibits A-site mRNA cleavage, the experiments presented herein demonstrate that prolonged growth at elevated temperature actually restores the activity. This heat-induced mRNase activity is dependent on the Lon protease, suggesting the activation of one or more TA modules during thermal stress. Taking a candidate-gene approach, we discovered that the yefM-yoeB TA operon is required for heat-induced A-site mRNA cleavage activity. Remarkably, YoeB mRNase activity remains constant over several hours of culture at 42°C. Cells proliferate rapidly under these conditions, demonstrating that growth arrest is not necessarily concomitant with toxin activation. Moreover, global protein synthesis is not suppressed by the active toxin. Together, these findings show that type II toxins can be activated at low levels in response to environmental stress. We propose that YoeB facilitates the recycling of stalled translation complexes, thereby playing a role in molecular quality control during thermal stress.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

All bacterial strains were derived from E. coli X90 (DE3) and are listed in Table1. The ΔclpB::kan, ΔhtpG::kan, Δlon::kan, and ΔclpP::kan alleles were obtained from the Keio collection (Baba et al. 2006) and were transferred between strains using bacteriophage P1-mediated transduction (Moore 2011). The ΔdnaK::kan disruption was generated as described (Hayes and Sauer 2003). Briefly, a region upstream of dnaK was amplified with primers (restriction sites are underlined) dnaK-Sac (5′-GAT GAG CTC CCA CTA GTT TAC TGC TGA TAA AGA G) and dnaK-Bam (5′-AAC GGA TCC ACT ATA TAT TCG GTC ATC ATG TGG); and a downstream region with dnaK-Eco (5′-GCT GAA TTC GAA GAA GTC AAA GAC AAA AAA TAA TCG) and dnaK-Kpn (5′-AAC GGT ACC AAA AAT ATC GCT GAA GTC TGC GCC). The two polymerase chain reaction (PCR) products were sequentially ligated to plasmid pKAN to generate pKAN-dnaK. Plasmid pKAN-dnaK was digested with SacI/KpnI and the small fragment was used to delete the dnaK gene by Red-mediated recombination (Thomason et al. 2014). Kanamycin-resistant cassettes were removed with flippase (FLP) recombinase to allow the construction of strains carrying multiple gene deletions (Cherepanov and Wackernagel 1995). All mutations were confirmed by locus-specific PCR amplification.

Table 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| X90 | F′ lacIq lac′ pro′/ara Δ[lac-pro] nalA argE[am] rifr thi-1 | Beckwith and Signer (1966) |

| CH12 | X90 (DE3) | Hayes et al. (2002a) |

| CH113 | X90 (DE3) ssrA::cat, CmR | Hayes et al. (2002a) |

| CH165 | X90 ΔssrA | This study |

| CH950 | X90 (DE3) Δlon::kan, KanR | This study |

| CH951 | X90 (DE3) ssrA::cat Δlon::kan, CmR KanR | This study |

| CH972 | X90 (DE3) ssrA::cat ΔrelBE::kan, CmR KanR | Hayes and Sauer (2003) |

| CH1019 | X90 (DE3) ssrA::cat ΔyefM-yoeB::kan, CmR KanR | Hayes and Sauer (2003) |

| CH1023 | X90 (DE3) ssrA::cat ΔdinJ-yafQ::kan, CmR KanR | Hayes and Sauer (2003) |

| CH1129 | X90 ΔyefM-yoeB::kan, KanR | Hayes and Sauer (2003) |

| CH1207 | X90 (DE3) ssrA::cat Δrnb::kan, CmR KanR | Garza-Sánchez et al. (2009) |

| CH3550 | X90 (DE3) ssrA::cat ΔrelBE ΔchpBIK ΔyefM-yoeB ΔmazEF ΔdinJ-yafQ ΔyhaV, CmR | Garza-Sánchez et al. (2009) |

| CH4646 | X90 Δrnb ssrA::cat, CmR | This study |

| CH5820 | X90 Δrnb | This study |

| CH6157 | X90 (DE3) ΔssrA ΔclpPX-lon::cat, CmR | This study |

| CH6158 | X90 (DE3) ΔssrA ΔclpPX-lon::cat Δrnb::kan, CmR KanR | This study |

| CH6262 | X90 (DE3) ssrA::cat ΔclpP::kan, CmR KanR | This study |

| CH6595 | X90 (DE3) ssrA::cat ΔrelBE ΔchpBIK ΔyefM-yoeB ΔmazEF ΔdinJ-yafQ ΔyhaV Δrnb::kan, CmR KanR | This study |

| CH6608 | X90 (DE3) ssrA::cat Δrnb ΔclpP::kan, CmR KanR | This study |

| CH6609 | X90 (DE3) ssrA::cat Δrnb Δlon::kan, CmR KanR | This study |

| CH7212 | X90 (DE3) ssrA::cat Δrnb ΔrelBE::kan, CmR KanR | This study |

| CH7213 | X90 (DE3) ssrA::cat Δrnb ΔyefM-yoeB::kan, CmR KanR | This study |

| CH7214 | X90 (DE3) ssrA::cat Δrnb ΔdinJ-yafQ::kan, CmR KanR | This study |

| CH7215 | X90 (DE3) ssrA::cat ΔmazEF::kan, CmR KanR | Hayes and Sauer (2003) |

| CH7216 | X90 (DE3) ssrA::cat Δrnb ΔmazEF::kan, CmR KanR | This study |

| CH7217 | X90 (DE3) ssrA::cat ΔchpBIK::kan, CmR KanR | Hayes and Sauer (2003) |

| CH7218 | X90 (DE3) ssrA::cat Δrnb ΔchpBIK::kan, CmR KanR | This study |

| CH7219 | X90 (DE3) ssrA::cat ΔyhaV::kan, CmR KanR | This study |

| CH7220 | X90 (DE3) ssrA::cat Δrnb ΔyhaV::kan, CmR KanR | This study |

| CH7360 | X90 ΔssrA ΔyefM-yoeB::kan, KanR | This study |

| CH7361 | X90 ΔssrA Δlon::kan, KanR | This study |

| CH7362 | X90 (DE3) ΔyefM-yoeB::kan, KanR | This study |

| CH7440 | X90 Δrnb ssrA::cat ΔyefM-yoeB::kan, CmR KanR | This study |

| CH7442 | X90 Δrnb ssrA::cat Δlon::kan, CmR KanR | This study |

| CH12151 | X90 (DE3) ssrA::cat Δrnb ΔdnaK::kan, CmR KanR | This study |

| CH12301 | X90 (DE3) ssrA::cat Δrnb ΔhtpG::kan, CmR KanR | This study |

| CH12314 | X90 (DE3) ssrA::cat Δrnb ΔclpB::kan, CmR KanR | This study |

| CH12402 | X90 (DE3) ssrA::cat Δrnb ΔyefM-yoeB ΔdnaK::kan, CmR KanR | This study |

| CH12403 | X90 (DE3) ssrA::cat Δrnb Δlon ΔdnaK::kan, CmR KanR | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pSIM6 | Temperature-induced expression of phage λ Red recombinase proteins, AmpR | Datta et al. (2006) |

| pCP20 | Temperature-induced expression of FLP recombinase, AmpR CmR | Cherepanov and Wackernagel (1995) |

| pCH450 | pACY184 derivative carrying arabinose-inducible araBAD promoter and araC, TetR | Hayes and Sauer (2003) |

| pKAN | pBluescript SK+ with FRT-flanked kanamycin-resistant cassette, AmpR, KanR | Hayes et al. (2002a) |

| pKAN-dnaK | Construct for deletion of Escherichia coli dnaK, AmpR KanR | This study |

| pFLAG-(m)YbeL-PP | Expresses FLAG epitope fused to the C-terminal 49 residues of YbeL(E159P), AmpR | Janssen and Hayes (2009) |

| pFLAG-(m)YbeL(E28Am)-PP | Variant of FLAG-(m)YbeL-PP with amber termination codon at Glu28, AmpR | This study |

| pCH450-lon | Arabinose-inducible expression of lon, TetR | This study |

| pCH450-lon(S679A) | Arabinose-inducible expression of catalytically inactive lon, TetR | This study |

| pCH450-yoeB | Arabinose-inducible expression of yoeB, TetR | This study |

| pCH450-yefM | Arabinose-inducible expression of yefM, TetR | This study |

| pCH450-yefM-yoeB | Arabinose-inducible expression of yefM-yoeB operon, TetR | This study |

| pCH410-relB | Arabinose-inducible expression of relB, TetR | This study |

| pCH450-rpoH | Arabinose-inducible expression of σ32 heat-shock transcription factor, TetR | This study |

AmpR, ampicillin resistant; CmR, chloramphenicol resistant; KanR, kanamycin resistant; TetR, tetracycline resistant.

Escherichia coli cells were grown in lysogeny broth (LB) media supplemented with the appropriate antibiotics (ampicillin, 150 μg/mL; chloramphenicol, 66 μg/mL; kanamycin, 50 μg/mL; and tetracycline 25 μg/mL). Cells from overnight cultures were resuspended at optical density (OD600) ∼0.05 in fresh LB supplemented with the appropriate antibiotics. Cells were grown to mid-log phase (at the indicated temperatures) with shaking, then flag-(m)ybeL-PP expression was induced with isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at a final concentration of 1.5 mmol/L. After 30 min, the induced cultures were poured into an equal volume of ice-cold methanol to arrest growth. The effects of Lon, YefM, YoeB, RelB, and σ32 on mRNA processing were determined by expressing the corresponding genes from a plasmid-borne PBAD promoter (Hayes and Sauer 2003). Cells were grown to mid-log phase at the indicated temperatures and flag-(m)ybeL-PP induced with 1.5 mmol/L IPTG. After 30 min, l-arabinose was added to 0.4% and incubation continued for an additional 15 min. Cultures were then poured into an equal volume of ice-cold methanol. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and the cell pellets frozen at −80°C for subsequent RNA isolation. The growth-rate response to acute heat shock was determined in LB medium without antibiotics. Cells were grown for 2.5 h at 30°C in an environmental shaker. Cultures were then split in two, with one culture maintained at 30°C while the other was transferred to a shaking-water bath equilibrated at 42°C. The growth of each culture was monitored during the acute heat shock and for an additional 4.5 h. Long-term growth at various temperatures was performed on LB agar without antibiotics. Cells were grown to mid-log phase in shaking LB medium at 30°C. Culture density was adjusted to OD600 = 1.0, then subjected to 10-fold serial dilutions in LB medium. Samples (2 μL) from each dilution were spotted onto LB agar and incubated at the indicated temperatures for 15 h.

Plasmid constructs

Plasmid pFLAG-(m)YbeL-PP has been described previously (Janssen and Hayes 2009; Seidman et al. 2011). An amber stop codon was introduced at codon 28 of pFLAG-(m)YbeL-PP using the megaprimer PCR approach (Aiyar and Leis 1993). Plasmid pFLAG-(m)-YbeL-PP was first amplified with primers Glu28Amb (5′-GGC TGG GAA ATC TGG TCT GCT AGA AAT GTC ACT TCC ATC TCC) and pET-Eco (5′-CGT CTT CAA GAA TTC TCA TGT TTG ACA GC). The resulting product was used as a megaprimer with pET-Sph/Pst (5′-CAA GGA ATG GTG CAT GCC TGC AGA TGG CGC CC) to amplify the flag-(m)ybeL-PP coding sequence and T7 promoter. The final product was digested with SphI/EcoRI and ligated to plasmid pET11d. The relB, rpoH, yefM, and yoeB genes were all amplified from E. coli genomic DNA and ligated to plasmids pCH410 or pCH450 to generate l-arabinose-inducible expression constructs. The relB gene was amplified with relB-Nde (5′ - GAG GTG TAA CAT ATG GGT AGC ATT AAC CTG CG) and relB-Sac-rev (5′-AAT GAG CTC TCA GAG TTC ATC CAG CGT CAC ACG), digested with NdeI/SacI and ligated to plasmid pCH410 (Hayes and Sauer 2003). The rpoH gene was amplified with rpoH-Eco (5′-ATA GAA TTC AAG GAG ATA TCA TAT GAC TGA CAA AAT GCA AAG TTT AGC) and rpoH-Xho (5′-TAT CTC GAG AAA TTA CGC TTC AAT GGC AGC), digested with EcoRI/XhoI and ligated to plasmid pCH450. The yefM gene was amplified with yefM-Eco (5′-TTT GAA TTC CAT ATG AAC TGT ACA AAA GAG G) and yefM-Sac (5′-TGA GAG CTC AGA CCA GAT TAG TTT CAC TCA ATG ATG), digested with EcoRI/SacI and ligated to pCH450. The yoeB gene was amplified with yoeB-Eco (5′-GGA GAA TTC CAT ATG AAA CTA ATC TGG TCT GAG G) and yoeB-Sac (5′-ATA GAG CTC CGC TAG CGT ATC AAA ACT GAC AAT TC), digested with EcoRI/SacI and ligated to pCH450. The yefM-yoeB operon was amplified with primers yefM-Eco and yoeB-Sac, digested with EcoRI/SacI and ligated to pCH450. The wild-type and Ser679Ala alleles of lon were excised from plasmids pBAD33::lon and pBAD33::lon(S679A) (Gur and Sauer 2008) by SacI/SbfI digestion, and the fragments ligated to SacI/PstI-digested plasmid pCH450.

RNA isolation and analysis

Total RNA was isolated from frozen E. coli cell pellets using guanidinium isothiocyanate-phenol extraction as described (Garza-Sánchez et al. 2006). RNA was quantified by absorbance at 260 nm and 10 μg run on Tris-borate-ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid, 10% polyacrylamide gels containing 50% urea. Gels were electroblotted onto Nytran Supercharge nylon membranes and subjected to northern blot hybridization using oligonucleotide probes as described (Hayes and Sauer 2003; Garza-Sánchez et al. 2006). Radiolabeled oligonucleotide T7-SD probe (5′-GTA TAT CTC CTT CTT AAA GTT AAA C) was used as a probe to detect flag-(m)ybeL-PP transcript. Endogenous transcripts were detected with radiolabeled oligonucleotides: lpp 5′-probe (5′-CAT TAT TAA TAC CCT CTA GAT TGA G); lpp 3′-probe (5′-CTT GCG GTA TTT AGT AGC CAT G); ompA 5′-probe (5′-CAT TTT TTG CGC CTC GTT ATC ATC); grpE 5′-probe (5′-CAT GAA TTT CTC CGC GTT TTT TTC G); and ibpB 5′-probe (5′-CAT AGT CAT TTC TCC TTC TAA GAA GC). All northern blots were imaged with an FX phosphorimager using the Quantity One software package (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA USA).

Immunoblot analysis

Protein was extracted from frozen cells using freeze-thaw in urea lysis buffer (50% urea, 10 mmol/L Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 150 mmol/L NaCl) and lysates clarified by centrifugation at 15,000 × g for 15 min (Hayes et al. 2002b). Protein was quantified by the Bradford method and equal amounts of total urea-soluble protein were run on Tris–tricine sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) 10% polyacrylamide gels. Immunoblot analysis was performed as described (Janssen and Hayes 2009), and blots were imaged using a Odyssey® infrared imager (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE, USA). Lon antigen was detected with rabbit polyclonal antisera and IRDye® 680 (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE, USA) labeled anti-rabbit secondary antibodies.

Results

A-site nuclease activity is induced at elevated temperature

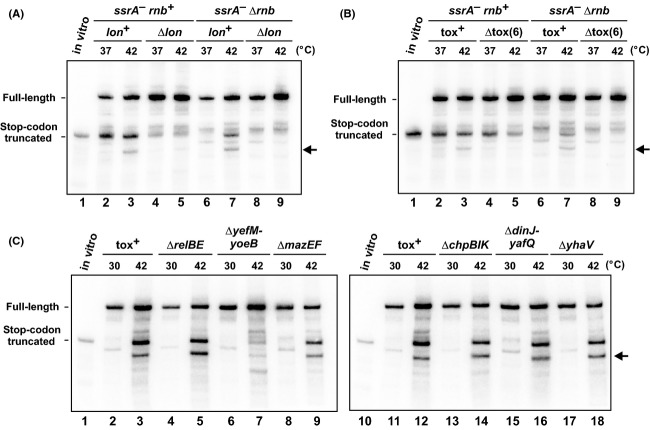

We previously reported that A-site mRNA cleavage is suppressed during heat shock (Garza-Sánchez et al. 2009), suggesting that the A-site nuclease is thermolabile. Alternatively, abrupt increases in temperature could disrupt protein synthesis temporarily and therefore indirectly affect A-site cleavage. To test this possibility, we revisited these experiments using the previously described flag-(m)ybeL-PP transcript as a reporter of A-site mRNA cleavage (Fig.1A) (Garza-Sánchez et al. 2009; Janssen and Hayes 2009). This transcript encodes a C-terminal Pro–Pro peptide motif, which interferes with translation termination and induces cleavage at the A-site stop codon (Mottagui-Tabar et al. 1994; Bjornsson et al. 1996; Hayes et al. 2002a; Hayes and Sauer 2003; Garza-Sánchez et al. 2008). A substantial proportion of flag-(m)ybeL-PP transcripts is truncated in the stop codon when expressed in ssrA– mutants, which lack tmRNA, but not in ssrA+ cells (Fig.1B, compare lanes 2 and 4). Presumably, mRNA processing also occurs in wild-type cells, but the truncated messages are rapidly degraded once released from the stalled ribosome through tmRNA activity (Hayes and Sauer 2003; Yamamoto et al. 2003). As reported (Garza-Sánchez et al. 2009), RNase II (encoded by the rnb gene) is required for this activity because truncated transcripts were not detected in ssrA− Δrnb cells (Fig.1B, lane 6). We next examined RNA isolated from cells that had been grown at 42°C for 2 h, and unexpectedly found that A-site mRNA cleavage was not suppressed (Fig.1B, lane 3). In fact, growth at 42°C actually restored A-site cleavage activity to ssrA− Δrnb cells (Fig.1B, compare lanes 6 and 7). Another smaller truncated transcript was also detected in ssrA− cells grown at 42°C (Fig.1B, marked by an arrow in lanes 3 and 7). These observations suggest that a new RNase activity is induced during growth at 42°C. Because tmRNA promotes nonstop mRNA turnover during ribosome rescue (Yamamoto et al. 2003; Richards et al. 2006; Ge et al. 2010), the apparent absence of truncated mRNA in ssrA+ cells suggests that cleavage may occur during translation. We tested this hypothesis by introducing an amber stop codon at position Glu28 in the flag-(m)ybeL-PP coding sequence (Fig.1A). Thus, ribosomes terminate translation at codon 28 in the Glu28Am transcript, rather than the original ochre stop at codon 61. Truncated Glu28Am transcripts were not detected in any of the examined backgrounds (Fig.1C), indicating that translation to the tandem Pro codons is required for the heat-induced mRNase activity.

Figure 1.

A-site nuclease activity is induced at elevated temperature. (A) The flag-(m)ybeL-PP reporter transcript is presented schematically. The sequence expansion depicts the P- and A-site codons during translation termination, and the position of the glutamate-28 codon is indicated. The 5′-UTR northern blot probe hybridizes immediately upstream of the start codon. (B) Northern blot analysis of A-site mRNA cleavage. flag-(m)ybeL-PP transcripts were expressed in cells of the indicated genotype at 37°C and 42°C, and total RNA was analyzed by northern hybridization. (C) Northern blot analysis of flag-(m)ybeL-PP transcripts carrying the Glu28 amber mutation (Glu28Am). Wild-type (wt) and Glu28Am transcripts were expressed in the indicated genetic backgrounds at 37°C and 42°C and analyzed by northern hybridization. The migration positions of stop codon truncated messages in (B and C) are indicated by control transcripts prepared by in vitro transcription. The horizontal arrows in (B and C) indicate an additional truncated transcript that is produced during growth at 42°C.

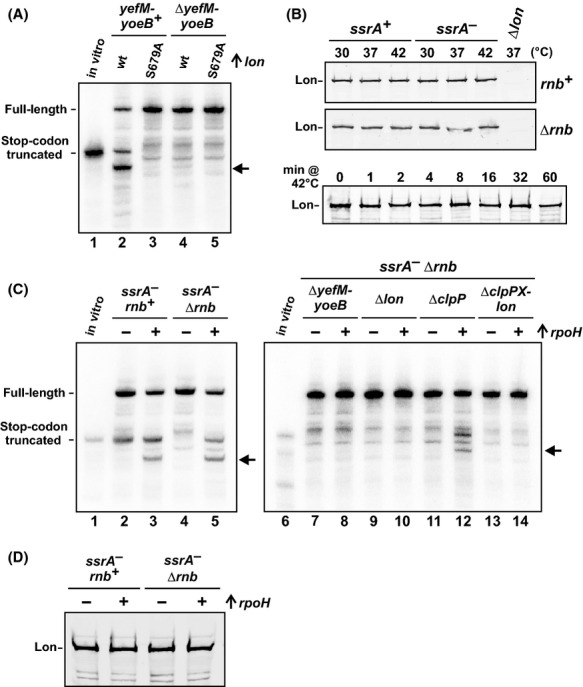

YoeB mediates A-site mRNA cleavage at elevated temperature

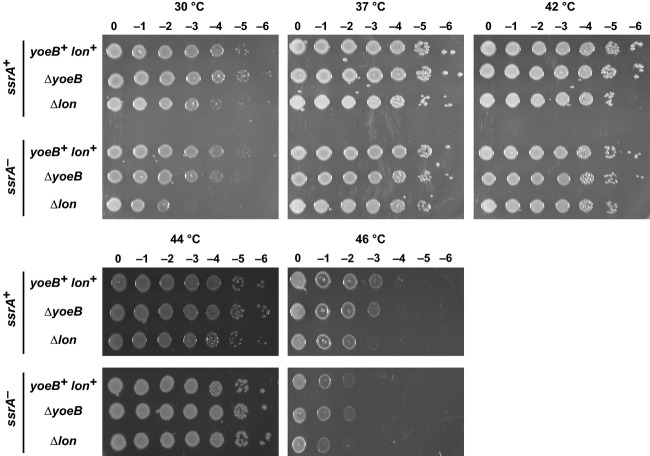

Some type II TA modules encode ribosome-dependent RNases that cleave A-site codons (Pedersen et al. 2003; Prysak et al. 2009; Feng et al. 2013). Toxins are typically activated through Lon protease-mediated degradation of antitoxins (Gerdes and Maisonneuve 2012; Brzozowska and Zielenkiewicz 2013); therefore we examined flag-(m)ybeL-PP transcript processing in Δlon cells. We observed less truncated mRNA in Δlon compared to lon+ backgrounds even at 37°C (Fig.2A, lanes 2 and 4), indicating that Lon influences A-site cleavage during translational pauses. But more importantly, we failed to detect heat-induced mRNase activity in Δlon mutants (Fig.2A, lanes 7 and 9). The latter result suggests that a toxin is responsible for heat-induced mRNase activity, which led us to test an E. coli strain that lacks multiple TA genes. The E. coli Δtox(6) strain lacks six validated TA systems encoded by the relBE, mazEF, yefM-yoeB, dinJ-yafQ, chpBIK and yhaV genes. As reported previously (Garza-Sánchez et al. 2009), flag-(m)ybeL-PP transcripts still undergo A-site cleavage in the ssrA− Δtox(6) background at 37°C (Fig.2B, lanes 2 and 4). However, ssrA− Δtox(6) Δrnb cells did not exhibit heat-induced mRNase activity (Fig.2B, lanes 7 and 9), strongly suggesting that one (or more) of the deleted toxins is responsible for activity. Further analysis of ssrA− Δrnb strains carrying individual TA gene deletions revealed that ΔyefM-yoeB mutants lack the heat-induced activity (Fig.2C).

Figure 2.

Lon and YoeB are required for temperature-induced A-site mRNA cleavage. (A) flag-(m)ybeL-PP transcripts were expressed in the indicated genetic backgrounds at 37°C and 42°C and analyzed by northern hybridization. (B) flag-(m)ybeL-PP transcripts were expressed in cells that lack six characterized toxin-antitoxin modules (Δtox(6)) at 37°C and 42°C, and compared to background that retain these toxin-antitoxin genes (tox+). (C) flag-(m)ybeL-PP transcripts were expressed in ssrA− Δrnb cells that carry deletions in the indicated toxin–antitoxin genes. Growth at 42°C induces truncated mRNA in all cells except those deleted for yefM-yoeB. The migration positions of stop codon truncated messages are indicated by control transcripts prepared by in vitro transcription. The horizontal arrows indicate an additional truncated transcript that is produced during growth at 42°C.

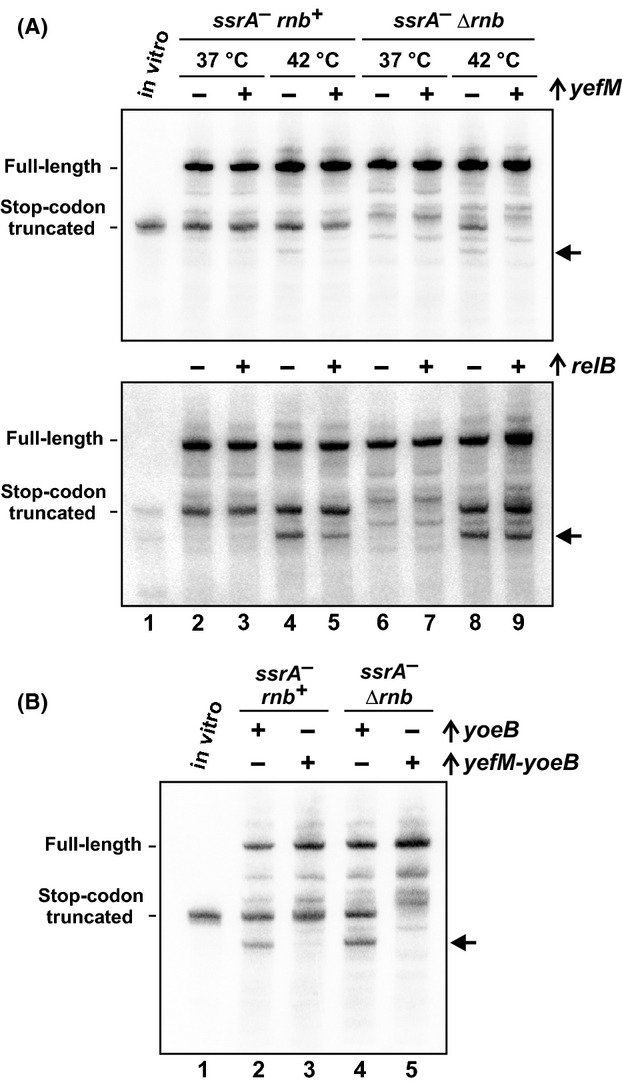

The YefM antitoxin specifically binds to YoeB toxin and neutralizes its RNase activity (Cherny et al. 2005; Kamada and Hanaoka 2005; Feng et al. 2013). Therefore, if heat-induced transcript cleavage is mediated by YoeB, then the activity should be specifically blocked by yefM overexpression. We cloned yefM under control of the PBAD promoter and induced expression in cells that coexpress flag-(m)ybeL-PP. In cells grown at 37°C, yefM expression had no discernible effect on mRNA cleavage (Fig.3A, lanes 2, 3, 6, and 7). However, yefM expression suppressed mRNA cleavage in ssrA− Δrnb cells at 42°C (Fig.3A, lane 8 and 9). This suppressive effect was specific because induction of relB, which encodes the antitoxin for RelE toxin, had little effect on heat-induced mRNase activity (Fig.3A, bottom blot). We then expressed yoeB from a plasmid-borne PBAD promoter to determine whether the toxin cleaves flag-(m)ybeL-PP transcripts. The two major truncated species that accumulate during thermal stress were also produced in response to yoeB induction at 37°C (Fig.3B, lanes 2 and 4). Thus, the heat-induced mRNA activity can be recapitulated by yoeB expression at lower temperature. In contrast, expression of the entire yefM-yoeB operon from the same plasmid vector did not induce mRNA cleavage (Fig.3B, lanes 3 and 5). Taken together, these data indicate that YoeB is responsible for the heat-induced mRNase activity.

Figure 3.

Overexpression of yefM suppresses temperature-induced A-site mRNA cleavage. (A) flag-(m)ybeL-PP transcripts were expressed in ssrA− rnb+ and ssrA− Δrnb backgrounds at 37°C and 42°C. Where indicated (+), the yefM or relB antitoxin genes were overexpressed from a plasmid-borne arabinose-inducible promoter. (B) flag-(m)ybeL-PP transcripts were expressed in ssrA− rnb+ and ssrA− Δrnb backgrounds at 37°C. Where indicated (+), the yoeB or yefM-yoeB genes were overexpressed from plasmid-borne arabinose-inducible promoters. The migration positions of stop codon truncated messages are indicated by control transcripts prepared by in vitro transcription. The horizontal arrows indicate an additional truncated transcript that is produced during growth at 42°C (A) or yoeB induction without yefM (B).

YoeB is activated during heat-shock stress

Christensen et al. 2004 have shown that overproduced Lon inhibits cell growth largely by activating YoeB. These findings indicate that YefM is particularly susceptible to proteolysis and suggest that thermal activation may be due to increased Lon levels. To address this possibility, we first confirmed that truncated flag-(m)ybeL-PP transcripts accumulate in cells that overexpress lon at 37°C (Fig.4A, lane 2). This mRNA processing was not observed when lon was induced in ΔyefM-yoeB cells (Fig.4A, lane 4). We also determined that protease activity is required for this effect, because truncated messages were not detected when catalytically inactive Lon(Ser679Ala) was overproduced (Fig.4A, lane 3) (Botos et al. 2004). Having established that increased Lon is sufficient to activate YoeB in our system, we then examined endogenous Lon levels by immunoblot. Given that Lon is considered to be a heat-shock protein (Phillips et al. 1984), we were surprised to find that Lon antigen levels were remarkably constant in cells cultured for 2.5 h at 30°C, 37°C, and 42°C (Fig.4B). Lon levels were also unchanged regardless of ssrA or rnb genetic background (Fig.4B). We further examined whether Lon levels increase transiently in response to temperature up-shift, but observed no significant increase over the first few minutes of heat stress (Fig.4B, lower blot). These data show that Lon overproduction can activate YoeB, but this mechanism does not account for activation at elevated temperature.

Figure 4.

Overexpression of lon and rpoH induces A-site mRNA cleavage. (A) Overexpression of lon induces A-site mRNA cleavage. flag-(m)ybeL-PP transcripts were expressed in ssrA− Δrnb backgrounds at 37°C. Where indicated, the lon or lon(S679A) genes were overexpressed from a plasmid-borne arabinose-inducible promoter. (B) Lon immunoblot analysis. Urea-soluble protein was isolated from cells of the indicated genotype that had been cultures at 30°C, 37°C or 42°C for 2.5 h. The bottom panel shows Lon levels in ssrA− Δrnb cells that had been cultured at 30°C for 1.5 h, then shifted to 42°C for the indicated number of minutes. (C) Overexpression of rpoH induces A-site mRNA cleavage. flag-(m)ybeL-PP transcripts were expressed in the indicated genetic backgrounds at 37°C. Where indicated (+), rpoH was overexpressed from a plasmid-borne arabinose-inducible promoter. In (A and C), the migration position of flag-(m)ybeL-PP transcript that is truncated at the stop codon is indicated, and horizontal arrows indicate an additional yoeB-dependent transcript. (D) Immunoblot analysis of Lon. Urea-soluble protein was isolated from cells of the indicated genotype that had been grown at 37°C. Where indicated (+), the σ32 heat-shock transcription factor (rpoH) was overexpressed. Samples were analyzed by immunoblot using polyclonal antisera to Lon protease.

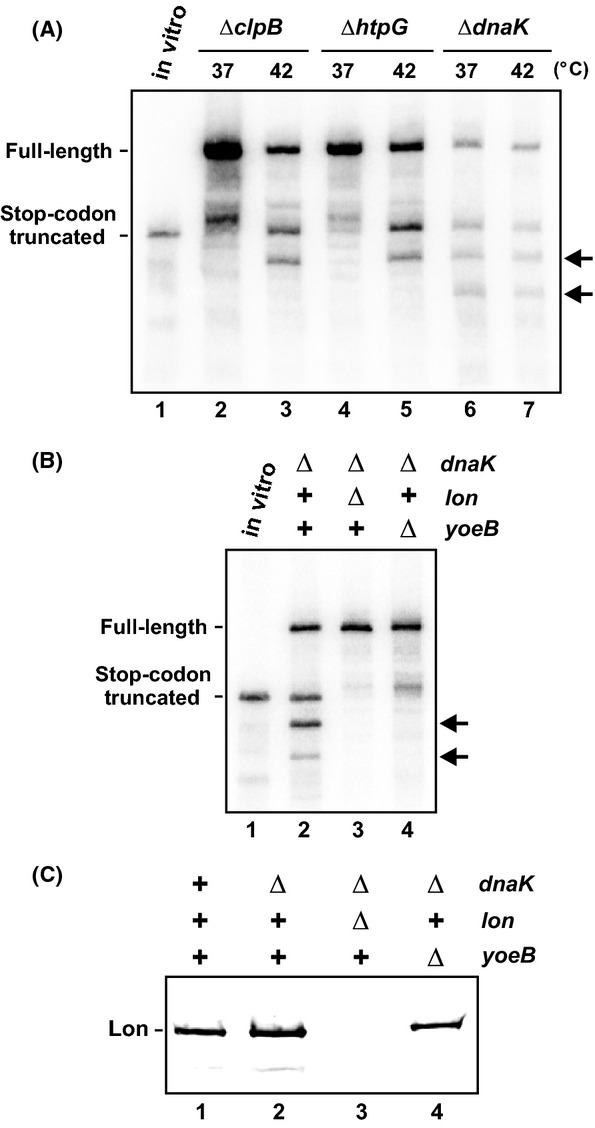

Heat shock activates the transcription of several genes that facilitate adaptation to thermal stress. We reasoned that an additional heat shock factor may collaborate with Lon to degrade YefM and therefore account for activation at high temperature. To test this hypothesis, we induced the heat-shock regulon through ectopic expression of rpoH, which encodes the σ32 heat-shock transcription factor (Nonaka et al. 2006; Guisbert et al. 2008). Expression of rpoH at 37°C induced an mRNase activity that is indistinguishable from that observed in cells grown at 42°C (Fig.4C, lanes 3 and 5). This activity was dependent on lon and yefM-yoeB, but not clpP (Fig.4C, lanes 8, 10, 12, and 14). We tested whether Lon increases in response to rpoH expression and found that protease levels remained constant (Fig.4D). Because YoeB is activated at lower temperature through induction of the heat-shock regulon, we tested whether known ATP-dependent chaperones facilitate activation. ClpB, HtpG, and DnaK are all induced during heat shock and have been implicated in the degradation and/or refolding of proteins at high temperature (Sherman and Goldberg 1992; Mogk et al. 1999; Thomas and Baneyx 2000; Huang et al. 2001). Therefore, we examined flag-(m)ybeL-PP transcripts expressed in ssrA− Δrnb cells that carry additional deletions of the clpB, htpG, or dnaK genes. The ΔclpB and ΔhtpG mutations had no effect on transcript processing at either 37°C or 42°C, but the ΔdnaK mutant showed increased mRNase activity even at 37°C (Fig.5A). In fact, yet another truncated flag-(m)ybeL-PP transcript accumulated in ssrA− Δrnb ΔdnaK cells (Fig.5A, indicated by lowest arrow in lanes 6 and 7). This additional truncation product presumably arises from YoeB-mediated cleavage at an upstream codon within the flag-(m)ybeL message. dnaK mutations are known to induce the heat-shock regulon at low temperature (Straus et al. 1990), suggesting that YoeB is activated in ΔdnaK cells by the same mechanism that underlies toxin activation during ectopic rpoH expression. In accord with this model, we found that lon and yefM-yoeB are both required for increased mRNase activity in the ΔdnaK background (Fig.5B, lanes 3 and 4). Additionally, immunoblot analysis showed that Lon protease levels do not increase dramatically in ΔdnaK mutants (Fig.5C). Collectively, these results demonstrate that YoeB is activated under three conditions – high temperature, rpoH expression and dnaK mutation – that induce the heat-shock regulon.

Figure 5.

YoeB is activated in ΔdnaK mutants. (A) Deletion of dnaK induces A-site mRNA cleavage activity. flag-(m)ybeL-PP transcripts were expressed in ssrA− Δrnb cells that carry additional deletions in clpB, htpG, or dnaK. The ΔclpB and ΔhtpG cells were grown at 37°C or 42°C as indicated. The ΔdnaK cells were grown at 37°C then maintained at 37°C or shifted to 42°C for the final 30 min of culture. (B) YoeB is activated in ΔdnaK mutants. flag-(m)ybeL-PP transcripts were expressed in ssrA− Δrnb cells carrying additional gene deletions as indicated. All cells were grown at 37°C and transcripts were detected by northern hybridization. In (A and B), the migration positions full-length and truncated flag-(m)ybeL-PP mRNA are indicated. The horizontal arrows indicate additional yoeB-dependent truncated transcripts. (C) Immunoblot analysis of Lon in ΔdnaK backgrounds. Urea-soluble protein was isolated from ssrA− Δrnb cells carrying additional gene deletions as indicated. All cells were grown at 37°C and Lon antigen was detected using polyclonal antisera.

Thermal activation of YoeB does not inhibit global protein synthesis

Previous work has shown that YoeB cleaves ompA and lpp transcripts in E. coli (Winther and Gerdes 2009; Zhang and Inouye 2009). Therefore, we tested whether YoeB cleaves these endogenous mRNAs in response to elevated temperature. We were unable to detect truncated lpp transcripts using probes to the 5′- and 3′-untranslated regions (Fig.6A). Similarly, the ompA transcript was not cleaved during culture at 42°C (data not shown). We also considered the possibility that YoeB may preferentially cleave heat-shock transcripts and provide a mechanism to fine-tune their translation. However, we did not detect yoeB-dependent cleavage in grpE and ibpB transcripts in response to growth at 42°C (Fig.6B). Although smaller ibpB transcripts were detected at 42°C in ssrA− cells, these fragments accumulated to similar levels in both yoeB+ and ΔyoeB backgrounds (Fig.6B). These data are seemingly at odds with the observation that flag-(m)ybeL-PP reporter transcripts are efficiently cleaved under the same growth conditions. We hypothesize that YoeB activity is focused on the reporter transcript due to a combination of overexpression and inefficient translation termination. We have shown previously that the entire pool of release factor-1 (RF-1) is sequestered on paused ribosomes during ybeL-PP overexpression (Janssen and Hayes 2009). RF-1 depletion then causes other ribosomes to stall at the ybeL-PP termination codon with unoccupied A sites (Janssen and Hayes 2009). Because YoeB must compete with translation factors to gain access to its A-site codon substrate, we propose that these latter ribosomes with unoccupied A sites are preferentially targeted by the nuclease.

Figure 6.

Thermal-induced YoeB activity is not detected on endogenous transcripts. (A) Total RNA from cells grown at 30°C and 42°C was analyzed by northern hybridization using oligonucleotide probes to the 5′- and 3′-untranslated regions of lpp mRNA in yoeB+ and ΔyefM-yoeB (ΔyoeB) backgrounds. (B) The same RNA samples from (A) were analyzed by northern hybridization using probes to the 5′-UTRs of grpE and ibpB messages.

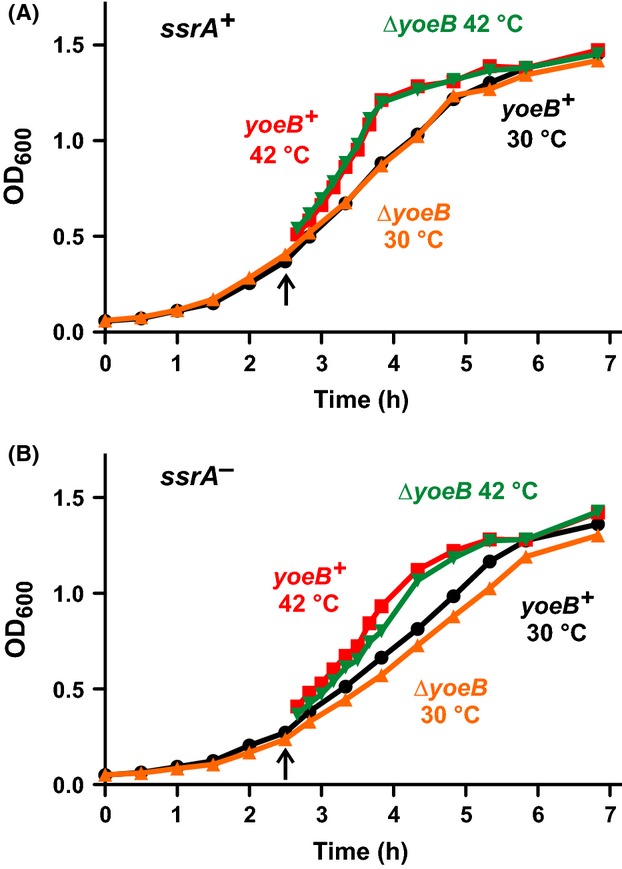

Cell growth is not inhibited during YoeB activation

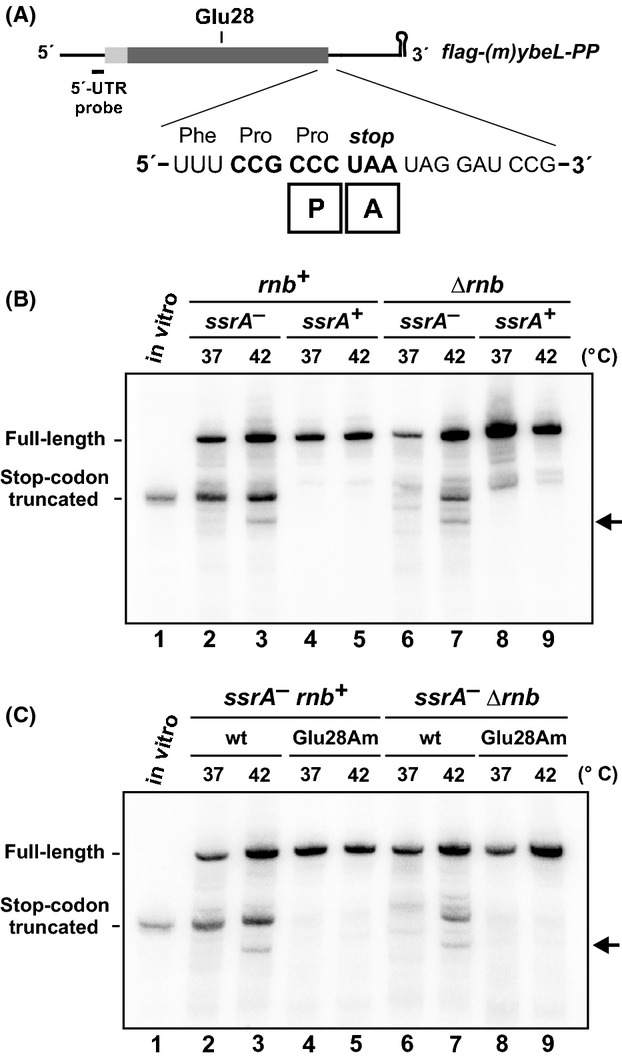

The stress-response model of TA function postulates that environmental stress activates mRNase toxins to temporarily inhibit translation while transcription is redirected to stress-response genes (Gerdes et al. 2005). Because YoeB is activated at high temperature, we asked whether acute heat shock leads to temporary growth arrest as predicted by the stress-response model. We monitored the growth of wild-type yoeB+ cells and observed no inhibition of growth during the transition from 30°C to 42°C (Fig.7A). Moreover, ΔyefM-yoeB mutants grew along the same trajectory as yefM-yoeB+ cells during the heat-shock treatment (Fig.7A). These results indicate that YoeB activity is not sufficient to arrest growth, consistent with the absence of detectable cleavage within endogenous messages at 42°C. tmRNA facilitates ribosome recycling after YoeB-mediated A-site cleavage, so we also examined the response of ssrA− cells to heat shock. Although ssrA− mutants grow more slowly than ssrA+ cells at 30°C and 42°C, the ΔyefM-yoeB mutation had little effect in this background (Fig.7B). Because YoeB activity persists over at least 2 h of culture at 42°C, we examined whether the toxin influences cell growth over longer time scales. We spotted yefM-yoeB+ and ΔyefM-yoeB cells onto LB agar for overnight incubation at temperatures ranging from 30°C to 46°C, but observed no differences in cell growth in various ssrA and lon backgrounds (Fig.8). In fact, the most prominent growth defects were observed with ssrA− cells at 46°C and Δlon cells at 30°C. The ssrA mutation reduced cell growth at 46°C about 10-fold in the yefM-yoeB and lon backgrounds (Fig.8). Additionally, Δlon cells grew more slowly than lon+ cells on solid medium at 30°C, and this effect was even more pronounced in the ssrA− background (Fig.8). Together, these results indicate that tmRNA and Lon contribute to fitness at high and low temperatures, but YefM and YoeB do not confer a discernible advantage under these conditions.

Figure 7.

Cell growth is not arrested during heat shock. (A) & (B) E. coli cells with the indicated genotypes were grown in shaking LB broth at 30°C for 2.5 h, then shifted to 42°C (indicated by the upward arrow) for continued culture. Cell growth was monitored by optical density at 600 nm (OD600).

Figure 8.

YoeB confers no growth advantage at elevated temperatures. Escherichia coli X90 cells of the indicated genetic backgrounds were adjusted to OD600 = 1.0, then serial diluted in LB medium and spotted onto LB agar for overnight growth at the indicated temperatures.

Discussion

The results presented here reveal temperature-induced mRNase activity in E. coli cells. Several observations argue that YoeB is responsible for this nuclease activity. First, transcripts must be actively translated in order to be cleaved. This is in accord with evidence that YoeB binds the ribosome and only cleaves translated messages in vivo (Christensen-Dalsgaard and Gerdes 2008; Feng et al. 2013). Second, temperature-induced mRNase activity requires Lon, consistent with the well-established role for this protease in antitoxin degradation (Gerdes et al. 2005; Tsilibaris et al. 2006; Gerdes and Maisonneuve 2012; Goeders and Van Melderen 2014). Third, expression of yoeB at lower temperatures recapitulates heat-induced mRNase activity; and yefM overexpression is sufficient to suppress mRNase activity at elevated temperature. Finally, ΔyefM-yoeB mutants do not exhibit heat-induced mRNase activity. Collectively, these results indicate that growth at elevated temperatures results in Lon-mediated degradation of YefM and concomitant activation of YoeB. These findings reinforce the conclusions of several previous studies showing that environmental stresses activate TA modules. Gerdes and colleagues have shown that RelE, MazF and other E. coli toxins become activated in response to amino acid starvation (Christensen et al. 2001; Christensen and Gerdes 2003). Additionally, the E. coli dinJ-yafQ operon contains a LexA box in its promoter, and its transcription is de-repressed in response to DNA damage (Prysak et al. 2009). Thus, our data are broadly consistent with a stress-response function and show that temperature stress is yet another environmental stimulus that activates TA modules.

Although YoeB activity becomes manifest at higher temperatures, the mechanism by which YefM is degraded preferentially over other antitoxins is not clear. Van Melderen and colleagues reported that gratuitous overproduction of Lon is sufficient to activate YoeB, but other known E. coli toxins were activated to a much lesser degree (Christensen et al. 2004). Similarly, the data presented here suggest that YoeB is the only toxin activated in response to elevated temperature. Together, these observations indicate that YefM is particularly sensitive to Lon activity. Although Lon is considered a heat-shock protein and lon transcription is upregulated during heat shock (Goff et al. 1984; Phillips et al. 1984), we find that Lon levels are essentially the same in cells grown at different temperatures. This argues that increased Lon concentration cannot account for thermal activation. It is also possible that YefM and YoeB dissociate in response to increased temperature, though it appears that YefM-YoeB is no more thermolabile than other TA complexes (Cherny et al. 2005). Moreover, we find that YoeB is activated at 37°C by inducing the heat-shock regulon through ectopic rpoH expression. This latter observation raises the possibility that an additional heat-shock factor may collaborate with Lon to degrade YefM. Indeed, there are reports of ATP-dependent chaperones working in concert with Lon to specifically degrade misfolded and damaged proteins (Sherman and Goldberg 1992; Huang et al. 2001). However, the ClpB, HtpG, and DnaK chaperones are not required for the thermal activation of YoeB. In fact, ΔdnaK mutants show constitutive activation of YoeB even at low temperature. This finding is consistent with recent data from the Chien and Laub laboratories showing that Caulobacter crescentus ΔdnaK mutants have increased Lon protease activity (Jonas et al. 2013). They find that unfolded proteins stimulate Lon activity allosterically. Because proteins tend to aggregate and misfold during thermal stress, the findings of Jonas et al. provide an explanation for increased protease activity in the absence of Lon overexpression. Their model may also account for YoeB activation in response to σ32 overproduction. DnaK binds to σ32 (Gamer et al. 1992; Liberek et al. 1992), and therefore overproduced transcription factor could potentially sequester the chaperone, preventing it from refolding other client proteins. Thus, super-physiological levels of σ32 could paradoxically lead to more unfolded proteins and increased Lon activity. Though this model accounts for Lon activity at high temperature, it does not explain why YefM is preferentially degraded while other antitoxins appear resistant to proteolysis. Presumably, YefM carries a unique recognition determinant that allows facile degradation. Given that Lon and YefM/YoeB are distributed widely throughout Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria (Nieto et al. 2007; Kumar et al. 2008; Yoshizumi et al. 2009; Sevillano et al. 2012), it will be of interest to determine whether thermal activation is conserved in other species.

Early biochemical studies showed that purified YoeB has intrinsic RNase activity in vitro (Kamada and Hanaoka 2005; Christensen-Dalsgaard and Gerdes 2008); but in vivo, the toxin only cleaves actively translated messages that are bound to the ribosome (Christensen-Dalsgaard and Gerdes 2008; Zhang and Inouye 2009; Feng et al. 2013). YoeB binds to the ribosome A site, where it cleaves the A-site codon to produce a truncated nonstop mRNA (Kamada and Hanaoka 2005; Feng et al. 2013). Although YoeB is generally accepted to be a ribosome-dependent A-site nuclease, there are conflicting reports about which stage of translation is affected. Inouye and colleagues have shown that YoeB acts during translation initiation (Yoshizumi et al. 2009; Zhang and Inouye 2009), whereas Gerdes and colleagues report YoeB-dependent cleavage in termination codons (Winther and Gerdes 2009). Both studies monitored the same endogenous lpp and ompA transcripts, but the experimental approaches differed. Zhang & Inouye overproduced YoeB from a plasmid vector, whereas the Gerdes group detected endogenous YoeB activity in response to ectopic VapC toxin overexpression (Winther and Gerdes 2009; Zhang and Inouye 2009). Our data show temperature-induced cleavage at two sites, one in the stop codon and another at an unidentified upstream position. Both cleavages are not observed when codon Glu-28 is mutated to an amber stop, indicating that the upstream cleavage site is well downstream of the start codon. Thus, our results are closer to those of Winther et al. and we conclude that endogenous YoeB activated at elevated temperature does not affect translation initiation.

The stress-response model of TA function postulates that activated toxins facilitate changes in gene expression in response to environmental stress (Christensen et al. 2003; Gerdes et al. 2005). The classic example is RelE activation in response to starvation. In this model, amino acid starvation slows protein synthesis, leading to depletion of RelB antitoxin due to its intrinsic instability. RelE then acts as an A-site nuclease to cleave translated messages and inhibit translation. The resulting stalled ribosomes are recycled by tmRNA-SmpB, which provides a burst of amino acids through proteolysis of ssrA-tagged nascent chains (Christensen and Gerdes 2003). The starved cells then alter transcription to express genes for amino acid biosynthesis and a new steady-state is eventually achieved. In principle, YoeB could function in the same manner to accelerate mRNA decay so that new heat-shock transcripts are translated more rapidly. However, we were unable to detect YoeB-dependent cleavages within endogenous messages. YoeB must compete with translation factors for access to the ribosome A site, and therefore it is more likely to cleave mRNA in the context of arrested ribosomes. Because heat shock does not inhibit global translation, YoeB activity is presumably limited to a small population of ribosomes that encounter difficulties during protein synthesis. In contrast, amino acid starvation stress not only activates RelE toxin, but also blocks protein synthesis to produce stalled ribosome complexes for RelE-mediated mRNA cleavage. Another discrepancy between our results and the stress-response model is the absence of growth arrest upon YoeB activation. In fact, E. coli cells show no growth lag in response to temperature up-shift, but rather accelerate their growth rate immediately. Moreover, YoeB activity is detectable over several hours of growth at elevated temperature. These data demonstrate that toxins can be activated at low levels, suggesting that they may actually promote more efficient protein synthesis under stress conditions. Heat shock and temperature stress has been shown to damage translation complexes and disrupt protein synthesis (Korber et al. 2000; Jiang et al. 2009). In our model, YoeB activity would perform a quality control function to help recycle translation complexes that stall stochastically during thermal stress. This is still adaptation to environmental stress, yet the proposed function is distinct from previously established roles for toxins in growth arrest and persistence (Maisonneuve et al. 2011; Gerdes and Maisonneuve 2012; Maisonneuve and Gerdes 2014).

Acknowledgments

We thank Bob Sauer for providing plasmids pBAD33-lon and pBAD33-lon(S379A), and Tania Baker for Lon antisera. This work was supported by grant GM078634 (to C. S. H.) from the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- Aiyar A. Leis J. Modification of the megaprimer method of PCR mutagenesis: improved amplification of the final product. Biotechniques. 1993;14:366–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baba T, Ara T, Hasegawa M, Takai Y, Okumura Y, Baba M, et al. Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2006;2:2006. doi: 10.1038/msb4100050. 0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranov PV, Vestergaard B, Hamelryck T, Gesteland RF, Nyborg J. Atkins JF. Diverse bacterial genomes encode an operon of two genes, one of which is an unusual class-I release factor that potentially recognizes atypical mRNA signals other than normal stop codons. Biol. Direct. 2006;1:28. doi: 10.1186/1745-6150-1-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckwith JR. Signer ER. Transposition of the lac region of Escherichia coli. I. Inversion of the lac operon and transduction of lac by phi80. J. Mol. Biol. 1966;19:254–265. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(66)80003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjornsson A, Mottagui-Tabar S. Isaksson LA. Structure of the C-terminal end of the nascent peptide influences translation termination. EMBO J. 1996;15:1696–1704. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botos I, Melnikov EE, Cherry S, Tropea JE, Khalatova AG, Rasulova F, et al. The catalytic domain of Escherichia coli Lon protease has a unique fold and a Ser-Lys dyad in the active site. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:8140–8148. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312243200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brzozowska I. Zielenkiewicz U. Regulation of toxin-antitoxin systems by proteolysis. Plasmid. 2013;70:33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2013.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chadani Y, Ono K, Ozawa S, Takahashi Y, Takai K, Nanamiya H, et al. Ribosome rescue by Escherichia coli ArfA (YhdL) in the absence of trans-translation system. Mol. Microbiol. 2010;78:796–808. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chadani Y, Ono K, Kutsukake K. Abo T. Escherichia coli YaeJ protein mediates a novel ribosome-rescue pathway distinct from SsrA- and ArfA-mediated pathways. Mol. Microbiol. 2011;80:772–785. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chadani Y, Ito K, Kutsukake K. Abo T. ArfA recruits release factor 2 to rescue stalled ribosomes by peptidyl-tRNA hydrolysis in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 2012;86:37–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherepanov PP. Wackernagel W. Gene disruption in Escherichia coli: TcR and KmR cassettes with the option of Flp-catalyzed excision of the antibiotic-resistance determinant. Gene. 1995;158:9–14. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00193-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherny I, Rockah L. Gazit E. The YoeB toxin is a folded protein that forms a physical complex with the unfolded YefM antitoxin. Implications for a structural-based differential stability of toxin-antitoxin systems. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:30063–30072. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506220200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen SK. Gerdes K. RelE toxins from bacteria and Archaea cleave mRNAs on translating ribosomes, which are rescued by tmRNA. Mol. Microbiol. 2003;48:1389–1400. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen SK, Mikkelsen M, Pedersen K. Gerdes K. RelE, a global inhibitor of translation, is activated during nutritional stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:14328–14333. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251327898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen SK, Pedersen K, Hansen FG. Gerdes K. Toxin-antitoxin loci as stress-response-elements: ChpAK/MazF and ChpBK cleave translated RNAs and are counteracted by tmRNA. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;332:809–819. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00922-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen SK, Maenhaut-Michel G, Mine N, Gottesman S, Gerdes K. Van Melderen L. Overproduction of the Lon protease triggers inhibition of translation in Escherichia coli: involvement of the yefM-yoeB toxin-antitoxin system. Mol. Microbiol. 2004;51:1705–1717. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen-Dalsgaard M. Gerdes K. Translation affects YoeB and MazF messenger RNA interferase activities by different mechanisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:6472–6481. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta S, Costantino N. Court DL. A set of recombineering plasmids for Gram-negative bacteria. Gene. 2006;379:109–115. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2006.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelberg-Kulka H, Hazan R. Amitai S. mazEF: a chromosomal toxin-antitoxin module that triggers programmed cell death in bacteria. J. Cell Sci. 2005;118:4327–4332. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feaga HA, Viollier PH. Keiler KC. Release of nonstop ribosomes is essential. MBio. 2014;5:e01916. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01916-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng S, Chen Y, Kamada K, Wang H, Tang K, Wang M, et al. YoeB-ribosome structure: a canonical RNase that requires the ribosome for its specific activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:9549–9556. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazao C, McVey CE, Amblar M, Barbas A, Vonrhein C, Arraiano CM, et al. Unravelling the dynamics of RNA degradation by ribonuclease II and its RNA-bound complex. Nature. 2006;443:110–114. doi: 10.1038/nature05080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon MG, Seetharaman SV, Bulkley D. Steitz TA. Structural basis for the rescue of stalled ribosomes: structure of YaeJ bound to the ribosome. Science. 2012;335:1370–1372. doi: 10.1126/science.1217443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamer J, Bujard H. Bukau B. Physical interaction between heat shock proteins DnaK, DnaJ, and GrpE and the bacterial heat shock transcription factor sigma 32. Cell. 1992;69:833–842. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90294-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garza-Sánchez F, Janssen BD. Hayes CS. Prolyl-tRNAPro in the A-site of SecM-arrested ribosomes inhibits the recruitment of transfer-messenger RNA. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:34258–34268. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608052200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garza-Sánchez F, Gin JG. Hayes CS. Amino acid starvation and colicin D treatment induce A-site mRNA cleavage in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;378:505–519. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.02.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garza-Sánchez F, Shoji S, Fredrick K. Hayes CS. RNase II is important for A-site mRNA cleavage during ribosome pausing. Mol. Microbiol. 2009;73:882–897. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06813.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge Z, Mehta P, Richards J. Karzai AW. Non-stop mRNA decay initiates at the ribosome. Mol. Microbiol. 2010;78:1159–1170. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07396.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdes K. Maisonneuve E. Bacterial persistence and toxin-antitoxin loci. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2012;66:103–123. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-092611-150159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdes K, Christensen SK. Lobner-Olesen A. Prokaryotic toxin-antitoxin stress response loci. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2005;3:371–382. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goeders N. Van Melderen L. Toxin-antitoxin systems as multilevel interaction systems. Toxins (Basel) 2014;6:304–324. doi: 10.3390/toxins6010304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goff SA, Casson LP. Goldberg AL. Heat shock regulatory gene htpR influences rates of protein degradation and expression of the lon gene in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1984;81:6647–6651. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.21.6647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gueneau de Novoa P. Williams KP. The tmRNA website: reductive evolution of tmRNA in plastids and other endosymbionts. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D104–D108. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guisbert E, Yura T, Rhodius VA. Gross CA. Convergence of molecular, modeling, and systems approaches for an understanding of the Escherichia coli heat shock response. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2008;72:545–554. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00007-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gur E. Sauer RT. Recognition of misfolded proteins by Lon, a AAA(+) protease. Genes Dev. 2008;22:2267–2277. doi: 10.1101/gad.1670908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handa Y, Inaho N. Nameki N. YaeJ is a novel ribosome-associated protein in Escherichia coli that can hydrolyze peptidyl-tRNA on stalled ribosomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:1739–1748. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes CS. Keiler KC. Beyond ribosome rescue: tmRNA and co-translational processes. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:413–419. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes CS. Sauer RT. Cleavage of the A site mRNA codon during ribosome pausing provides a mechanism for translational quality control. Mol. Cell. 2003;12:903–911. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00385-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes CS, Bose B. Sauer RT. Proline residues at the C terminus of nascent chains induce SsrA tagging during translation termination. J. Biol. Chem. 2002a;277:33825–33832. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205405200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes CS, Bose B. Sauer RT. Stop codons preceded by rare arginine codons are efficient determinants of SsrA tagging in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002b;99:3440–3445. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052707199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang HC, Sherman MY, Kandror O. Goldberg AL. The molecular chaperone DnaJ is required for the degradation of a soluble abnormal protein in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:3920–3928. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002937200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen BD. Hayes CS. Kinetics of paused ribosome recycling in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 2009;394:251–267. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen BD. Hayes CS. The tmRNA ribosome-rescue system. Adv. Protein Chem. Struct. Biol. 2012;86:151–191. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-386497-0.00005-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen BD, Garza-Sanchez F. Hayes CS. A-site mRNA cleavage is not required for tmRNA-mediated ssrA-peptide tagging. PLoS One. 2013;8:e81319. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L, Schaffitzel C, Bingel-Erlenmeyer R, Ban N, Korber P, Koning RI, et al. Recycling of aborted ribosomal 50S subunit-nascent chain-tRNA complexes by the heat shock protein Hsp15. J. Mol. Biol. 2009;386:1357–1367. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.10.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonas K, Liu J, Chien P. Laub MT. Proteotoxic stress induces a cell-cycle arrest by stimulating Lon to degrade the replication initiator DnaA. Cell. 2013;154:623–636. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamada K. Hanaoka F. Conformational change in the catalytic site of the ribonuclease YoeB toxin by YefM antitoxin. Mol. Cell. 2005;19:497–509. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keiler KC, Waller PR. Sauer RT. Role of a peptide tagging system in degradation of proteins synthesized from damaged messenger RNA. Science. 1996;271:990–993. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5251.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keiler KC, Shapiro L. Williams KP. tmRNAs that encode proteolysis-inducing tags are found in all known bacterial genomes: a two-piece tmRNA functions in Caulobacter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:7778–7783. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.14.7778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korber P, Stahl JM, Nierhaus KH. Bardwell JC. Hsp15: a ribosome-associated heat shock protein. EMBO J. 2000;19:741–748. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.4.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P, Issac B, Dodson EJ, Turkenburg JP. Mande SC. Crystal structure of Mycobacterium tuberculosis YefM antitoxin reveals that it is not an intrinsically unstructured protein. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;383:482–493. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.08.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Hirano R, Tagami H. Aiba H. Protein tagging at rare codons is caused by tmRNA action at the 3′ end of nonstop mRNA generated in response to ribosome stalling. RNA. 2006;12:248–255. doi: 10.1261/rna.2212606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Yagi M, Morita T. Aiba H. Cleavage of mRNAs and role of tmRNA system under amino acid starvation in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 2008;68:462–473. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberek K, Galitski TP, Zylicz M. Georgopoulos C. The DnaK chaperone modulates the heat shock response of Escherichia coli by binding to the sigma 32 transcription factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;89:3516–3520. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.8.3516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnuson RD. Hypothetical functions of toxin-antitoxin systems. J. Bacteriol. 2007;189:6089–6092. doi: 10.1128/JB.00958-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisonneuve E. Gerdes K. Molecular mechanisms underlying bacterial persisters. Cell. 2014;157:539–548. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisonneuve E, Shakespeare LJ, Jorgensen MG. Gerdes K. Bacterial persistence by RNA endonucleases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:13206–13211. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100186108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Mogk A, Tomoyasu T, Goloubinoff P, Rudiger S, Roder D, Langen H, et al. Identification of thermolabile Escherichia coli proteins: prevention and reversion of aggregation by DnaK and ClpB. EMBO J. 1999;18:6934–6949. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.24.6934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore SD. Assembling new Escherichia coli strains by transduction using phage P1. Methods Mol. Biol. 2011;765:155–169. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-197-0_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mottagui-Tabar S, Bjornsson A. Isaksson LA. The second to last amino acid in the nascent peptide as a codon context determinant. EMBO J. 1994;13:249–257. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06255.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nariya H. Inouye M. MazF, an mRNA interferase, mediates programmed cell death during multicellular Myxococcus development. Cell. 2008;132:55–66. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieto C, Cherny I, Khoo SK, de Lacoba MG, Chan WT, Yeo CC, et al. The yefM-yoeB toxin-antitoxin systems of Escherichia coli and Streptococcus pneumoniae: functional and structural correlation. J. Bacteriol. 2007;189:1266–1278. doi: 10.1128/JB.01130-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonaka G, Blankschien M, Herman C, Gross CA. Rhodius VA. Regulon and promoter analysis of the E. coli heat-shock factor, sigma32, reveals a multifaceted cellular response to heat stress. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1776–1789. doi: 10.1101/gad.1428206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen K, Zavialov AV, Pavlov MY, Elf J, Gerdes K. Ehrenberg M. The bacterial toxin RelE displays codon-specific cleavage of mRNAs in the ribosomal A site. Cell. 2003;112:131–140. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01248-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips TA, VanBogelen RA. Neidhardt FC. lon gene product of Escherichia coli is a heat-shock protein. J. Bacteriol. 1984;159:283–287. doi: 10.1128/jb.159.1.283-287.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prysak MH, Mozdzierz CJ, Cook AM, Zhu L, Zhang Y, Inouye M, et al. Bacterial toxin YafQ is an endoribonuclease that associates with the ribosome and blocks translation elongation through sequence-specific and frame-dependent mRNA cleavage. Mol. Microbiol. 2009;71:1071–1087. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards J, Mehta P. Karzai AW. RNase R degrades non-stop mRNAs selectively in an SmpB-tmRNA-dependent manner. Mol. Microbiol. 2006;62:1700–1712. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidman JS, Janssen BD. Hayes CS. Alternative fates of paused ribosomes during translation termination. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:31105–31112. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.268201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevillano L, Diaz M, Yamaguchi Y, Inouye M. Santamaria RI. Identification of the first functional toxin-antitoxin system in Streptomyces. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32977. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman M. Goldberg AL. Involvement of the chaperonin dnaK in the rapid degradation of a mutant protein in Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 1992;11:71–77. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05029.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu Y. ArfA recruits RF2 into stalled ribosomes. J. Mol. Biol. 2012;423:624–631. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus D, Walter W. Gross CA. DnaK, DnaJ, and GrpE heat shock proteins negatively regulate heat shock gene expression by controlling the synthesis and stability of sigma 32. Genes Dev. 1990;4:2202–2209. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.12a.2202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunohara T, Jojima K, Yamamoto Y, Inada T. Aiba H. Nascent-peptide-mediated ribosome stalling at a stop codon induces mRNA cleavage resulting in nonstop mRNA that is recognized by tmRNA. RNA. 2004;10:378–386. doi: 10.1261/rna.5169404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JG. Baneyx F. ClpB and HtpG facilitate de novo protein folding in stressed Escherichia coli cells. Mol. Microbiol. 2000;36:1360–1370. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01951.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomason LC, Sawitzke JA, Li X, Costantino N, Court DL. Recombineering: genetic engineering in bacteria using homologous recombination. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. 2014;106:16.1–1.16.39. doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb0116s106. 1, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsilibaris V, Maenhaut-Michel G. Van Melderen L. Biological roles of the Lon ATP-dependent protease. Res. Microbiol. 2006;157:701–713. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsilibaris V, Maenhaut-Michel G, Mine N. Van Melderen L. What is the benefit to Escherichia coli of having multiple toxin-antitoxin systems in its genome? J. Bacteriol. 2007;189:6101–6108. doi: 10.1128/JB.00527-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu GF, Reid GE, Zhang JG, Moritz RL. Simpson RJ. C-terminal extension of truncated recombinant proteins in Escherichia coli with a 10Sa RNA decapeptide. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:9322–9326. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.16.9322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winther KS. Gerdes K. Ectopic production of VapCs from Enterobacteria inhibits translation and trans-activates YoeB mRNA interferase. Mol. Microbiol. 2009;72:918–930. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto Y, Sunohara T, Jojima K, Inada T. Aiba H. SsrA-mediated trans-translation plays a role in mRNA quality control by facilitating degradation of truncated mRNAs. RNA. 2003;9:408–418. doi: 10.1261/rna.2174803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshizumi S, Zhang Y, Yamaguchi Y, Chen L, Kreiswirth BN. Inouye M. Staphylococcus aureus YoeB homologues inhibit translation initiation. J. Bacteriol. 2009;191:5868–5872. doi: 10.1128/JB.00623-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. Inouye M. The inhibitory mechanism of protein synthesis by YoeB, an Escherichia coli toxin. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:6627–6638. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808779200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo Y, Vincent HA, Zhang J, Wang Y, Deutscher MP. Malhotra A. Structural basis for processivity and single-strand specificity of RNase II. Mol. Cell. 2006;24:149–156. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]