Abstract

Background and study aims: Early detection of superficial pharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (SPSCC) using narrow-band imaging as well as the increasing use of ER for gastrointestinal cancers may increase the number of ER for SPSCC. The aims of this study were to clarify the feasibility of ER for SPSCC and its long-term outcomes.

Patients and methods: In total, 84 patients with 115 lesions were treated by endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) or endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) between March 2004 and August 2012. We retrospectively assessed the en bloc and R0 resection rates, complications, lymph node metastasis (LNM), local recurrence, metachronous pharyngeal and esophageal SCC, 5-year overall and cause-specific survival rates.

Results: Higher proportions of en bloc and R0 resection were achieved with ESD compared to EMR (en bloc 100 % vs. 60 %, P < 0.001; R0 59 % vs. 26 %, P < 0.005). There were no significant complications in both groups. None of the patients died from primary SPSCC during the median follow-up of 34 months (range, 3 – 115). LNM occurred in three patients and local recurrence was detected in seven patients (8.3 %) with eight lesions. Tumor thickness over 1000 μm (P < 0.005) and positive or inconclusive horizontal margins (P < 0.05) were significant risk factors for LNM and local recurrence, respectively. Twelve patients died because of co-existing clinical conditions. The 5-year overall and cause-specific survival rates were 80.7 % and 100 %, respectively.

Conclusions: ER for SPSCC is a feasible treatment with promising results. Tumor thickness over 1000 μm is a significant risk factor for LNM and positive or inconclusive horizontal margin is a risk factor for local recurrence.

Introduction

Recent improvements in endoscopic imaging including narrow-band imaging (NBI) and magnification as well as raising awareness among endoscopists of superficial pharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (SPSCC) have increased the detection of such lesions 1 2. ER for SPSCC is now being used more frequently since endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) for gastrointestinal cancer have become established in clinical practice 3 4. Previously, most pharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas (SCC) were detected at advanced stages and treated by extensive surgical resection and chemoradiotherapy as standard treatment. These therapies frequently compromised taste, swallowing and speech function, resulting in a lower quality of life for the patients 5. ER is a minimally invasive treatment preserving the organ and the patient’s quality of life 6 7 8 9.

The indications for ER and the pathological criteria for curative resection are currently entrusted to the judgment of individual institutions. Clear guidelines to standardize current clinical practice are urgently needed. Pharyngeal SCC differs from other gastrointestinal cancers because the pharynx has no muscularis mucosae apart from in a hypopharyngeal area close to the entrance of the esophagus. Furthermore, the association between depth of invasion, lymphovascular infiltration, and lymph node metastasis (LNM) has not been assessed clearly in previous reports. There are no clinical Japanese guidelines for the endoscopic treatment of SPSCC mainly due to the structural difference between the pharynx and other digestive sites. Long-term outcomes including recurrence, metachronous lesions, and survival rate after ER for SPSCC have not yet been fully evaluated. In this study, we assessed the short-term and long-term outcomes of ER for SPSCC.

Patients and methods

We retrospectively assessed the short-term and long-term outcomes of all 84 consecutive patients with 115 lesions who underwent ER for SPSCC between March 2004 and August 2012 at the National Cancer Center Hospital in Tokyo, Japan. The institutional review board of our hospital approved this study and informed consent was obtained from all patients in accordance with our institutional protocol. Clinical outcomes were divided into ESD and EMR groups, including EMR with cap method and a strip biopsy. In terms of short-term outcomes, we assessed tumor size, technical results, procedure time, adverse events, length of hospitalization, and histopathological results. En bloc resection was defined as resection of the lesion in one piece as opposed to piecemeal resection defined as at least two pieces needed to achieve complete resection. R0 resection was defined as en bloc resection with tumor-free margins. Long-term outcomes included cause of death, LNM, local recurrence, metachronous pharyngeal and esophageal SCC, cumulative incidence of metachronous SPSCC, and the rates of overall and cause-specific survival after ER.

Indication for endoscopic treatment

There are no national guidelines for endoscopic treatment of SPSCC in Japan. In our hospital, indications for ER after the detection of SPSCC are (i) SCC or high grade intraepithelial neoplasia detected by biopsy including suspicion of the diagnosis; (ii) no highly protruding areas or ulceration beyond suspected minor invasion to the subepithelial layer; (iii) endoscopic diagnosis as a carcinoma in situ or a carcinoma with invasion to the subepithelial layer by conventional white light imaging and NBI with magnification; (iv) no findings of LNM and distant metastasis at computed tomography or ultrasonography. Patients with hypopharyngeal lesions involving the laryngeal cavity and/or with a high risk of stenosis owing to the wide resection were considered to be outside the criteria of this study.

Endoscopic procedures

All of the procedures were performed in collaboration with the HN surgeons. EMR was mainly performed until 2010, and then gradually replaced by ESD from 2011 onwards. Currently in our unit, EMR is indicated for small lesions (≤ 10 mm) located in the pyriform sinus of the hypopharynx or uvula of the oropharynx where the mucosal layer allows a good lifting by injection. ESD is usually performed for lesions located in other areas or more than 10 mm in size. Until 2009, some procedures were performed under intravenous anesthesia in the endoscopy room such as EMR for lesions located in the uvula of the oropharynx. Since 2010, all procedures have been performed under general anesthesia controlled by an anesthesiologist in the operating room. Patients were intubated and set in the supine position. The HN surgeon elevated the larynx using a curved laryngoscope to allow sufficient viewing area and working space in the pharynx. SPSCC was initially examined by white light imaging and NBI with magnification followed by chromoendoscopy with 2 % Lugol staining to detect the unstained area with clear margins. A mucosal lifting was achieved by injecting the diluted epinephrine with normal saline (1:200 000) and a minute amount of indigo-carmine dye.

A transparent plastic cap (D-206-05; Olympus Medical Systems, Tokyo, Japan) was attached to the tip of the regular endoscope when EMR with cap method was performed. The lesion was suctioned into the cap and strangulated by the snare (SD-5U-1; Olympus). A double-channel endoscope (GIF-2T240; Olympus) was used to obtain a strip biopsy. A snare and grasping forceps were inserted through both channels and the lesion was strangulated by the snare after grasping. For ESD, marking dots were made around the lesion with a DualKnife™ (KD-650; Olympus). The DualKnife™ and insulation-tipped (IT) knife nano™ (KD-612; Olympus) were used for epithelial incision and subepithelial dissection. Immediate bleeding was treated using a hemostatic forceps (Coagrasper®, FD-411 QR; Olympus).

Follow-up examinations

No additional treatment was performed after ER regardless of pathological results. After ER, patients were usually followed up by the HN surgeons because there were no clear pathological criteria of a curative resection for SPSCC owing to the lack of sufficient numbers of cases and relatively short history of this procedure. The standard follow-up included laryngoscope and cervical palpation to detect lymph node enlargement every 3 months during the first 2 years of follow-up. A cervical CT scan was carried out to detect LNM every 6 months in cases of lymphovascular infiltration and/or subepithelial invasion. Follow-up endoscopy was performed every 6 months to detect local recurrence and/or metachronous lesions.

Statistical analysis

All variables in this study were described in terms of mean, median, standard deviation, and range. Clinical outcomes were analyzed using the χ2 test and Fisher's exact test, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Overall and cause-specific survival rates were calculated by the Kaplan-Meier method. We used SPSS version 17 software (SPSS Japan Inc., Tokyo, Japan) for statistical analysis.

Results

Patient characteristics and endoscopic findings

We included 84 consecutive patients (81 males and 3 females) with 115 lesions. Their mean age was 66.0 ± 7.1 years. Neither the patient nor the lesion characteristics differed significantly between ESD and EMR groups (Table 1). In total, 79 patients (94.0%) had a synchronous or previous history of esophageal or pharyngeal SCC. Among the 115 lesions, 24 were located in the oropharynx and 91 in the hypopharynx. According to the Japanese classification of esophageal cancer published by the Japan Esophageal Society, macroscopic types were as follows 10: 0-I, 2 lesions; 0-IIa, 50 lesions; 0-IIb, 56 lesions; 0-IIc, 7 lesions. Median tumor size was 10 mm (range, 2 – 40).

Table 1. Patient characteristics and endoscopic findings.

| ESD | EMR | |

| Patients, n Lesions, n |

17 22 |

67 93 |

| Age, mean ± SD, years | 67 ± 7.4 | 66 ± 7.0 |

| Male, n Female, n |

16 1 |

65 2 |

| Patients with synchronous or previous history of esophageal or pharyngeal SCC, n (%) | 17 (100) | 62 (93) |

| Hypopharynx, n (%) Oropharynx, n (%) |

19 (86) 3 (14) |

72 (77) 21 (23) |

| Macroscopic type, n 0-I 0-IIa 0-IIb 0-IIc |

0 10 12 0 |

2 40 44 7 |

| Median follow-up period (range), months | 19 (12 – 30) | 42 (3 – 115) |

ESD, endoscopic submucosal dissection; EMR, endoscopic mucosal resection; SD, standard deviation; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

Technical results and complications of endoscopic treatments

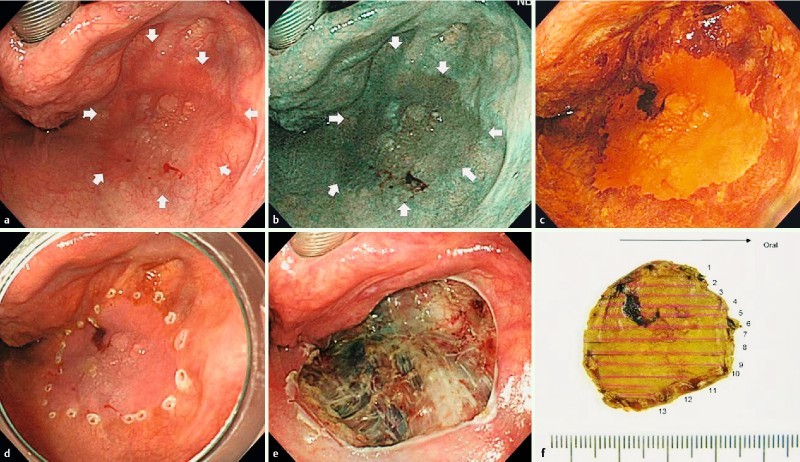

Table 2 shows the details of ER procedures. ESD (Fig. 1) and EMR were performed in 22 and 93 cases, respectively, and the median tumor size was 13 mm (5 – 32) and 11 mm (2 – 40) for ESD and EMR, respectively (P = 0.54). Higher proportions of en bloc and R0 resection were achieved during ESD when compared to EMR (en bloc 100 % vs. 60 %, P < 0.001; R0 59 % vs. 26 %, P < 0.01). The median procedure time for ESD was significantly longer than EMR (60 min [30 – 195] vs. 36 min [10 – 120], P < 0.01).

Table 2. Technical results and complications (n = 115 lesions).

| ESD (22 lesions) | EMR (93 lesions) | |

| Median tumor size (range), mm | 13 (5 – 32) | 11 (2 – 40) |

| Result of resection, n (%) En bloc R01 |

22 (100) 13 (59) |

56 (60) 24 (26) |

| Median procedure time (range), min | 60 (30 – 195) | 36 (10 – 120) |

| Complications, n (%) Edema Emphysema Stenosis Dermatitis |

2 (9) 1 (5) 0 (0) 0 (0) |

3 (3) 2 (2) 1 (1) 1 (1) |

| Median hospital stay (range), days | 6 (5 – 14) | 6 (4 – 12) |

ESD, endoscopic submucosal dissection; EMR, endoscopic mucosal resection.

En bloc with tumor-free margins.

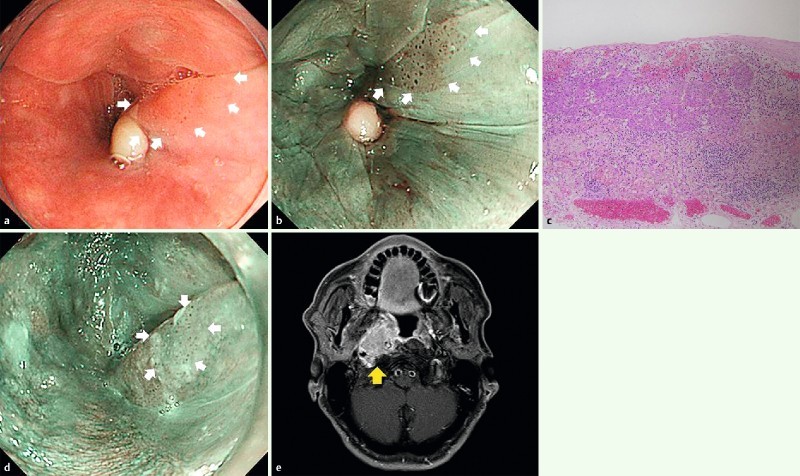

Fig. 1 a.

Reddish flat elevated lesion located in the right pyriform sinus of the hypopharynx. b A well demarcated brownish area demonstrated using narrow-band imaging. c Chromoendoscopy using Lugol staining demonstrated the unstained lesion. d Marking dots around the lesion. e Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) ulceration made by en bloc resection without any complications. f Macroscopic image of the resected specimen. Histopathological examination revealed squamous cell carcinoma with subepithelial invasion.

Delayed bleeding, the most common adverse event post ER, was not observed in our series. The recorded adverse events included laryngeal edema in two patients after ESD and in three patients after EMR followed by one reintubation and one preventive tracheotomy. A subcutaneous emphysema occurred in two patients in the ESD group and in one patient in the EMR group. A pharyngeal stenosis and a dermatitis around the mouth were only recorded in patients in the EMR group. All cases were successfully managed medically and discharged without any further complications including loss of swallowing and speech function. There was no significant difference in the median length of hospital stay between the ESD group [6 days (5 – 14)] and the EMR group [6 days (4 – 12)].

Histopathological results

All resected specimens were SCC as expected. Histopathological results are shown in Table 3. Of the 115 lesions, 55 lesions were carcinoma in situ and 60 lesions invaded into the subepithelium. Two of those micro-invasive lesions also had lymphatic invasion. The number of lesions with negative, positive, and inconclusive horizontal margins was 39, 28, and 48 lesions, respectively. The number of lesions with negative, positive, and inconclusive vertical margins was 108, 0, and 7 lesions, respectively.

Table 3. Histopathological results (n = 115 lesions).

| ESD (22 lesions) | EMR (93 lesions) | |

| Tumor depth, n (%) Epithelium Subepithelium |

11 (50) 11 (50) |

44 (47) 49 (53) |

| Lymphovascular invasion, n (%) Negative Positive Inconclusive |

22 (100) 0 (0) 0 (0) |

90 (97) 2 (2) 1 (1) |

| Horizontal margin, n (%) Negative Positive Inconclusive |

13 (59) 2 (10) 7 (31) |

26 (29) 26 (27) 41 (44) |

| Vertical margin, n (%) Negative Positive Inconclusive |

22 (100) 0 (0) 0 (0) |

86 (92) 0 (0) 7 (8) |

ESD, endoscopic submucosal dissection; EMR, endoscopic mucosal resection.

Patient clinical course and long-term outcomes

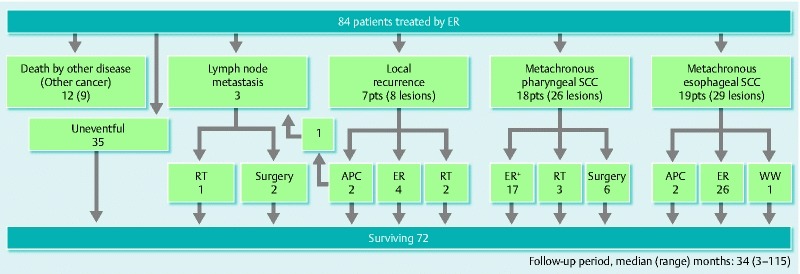

Fig. 2 shows a flow diagram for the clinical course of patients after ER. In total, 78 patients (93 %) were followed with the standard course strictly for at least 12 months and the median follow-up period was 34 months (3 – 115). However, six patients including four cases who died from co-existing diseases, and two who dropped out for personal reasons or for treatment of a brain contusion in another hospital, were followed for less than 1 year. Table 4 shows the clinicopathological results for the LNM cases. LNM occurred in three patients a median period of 24 months (21 – 48) after initial ER (Figs. 3, 4, 5). All lesions invaded into the subepithelium and measured more than 10 mm in size including one case with lymphovascular invasion detected in the specimen. Additional surgery was performed in two cases and radiation therapy (RT) in one case and the patients survived without any recurrence. The only significant risk factor for LNM was a tumor thickness over 1000 μm (P < 0.005) (Table 5).

Fig. 2.

Clinical course flow diagram of patients after ER. ER, ER; RT, radiation therapy; APC, argon-plasma coagulation; pts, patients; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; WW, watchful waiting; + Including two cases performed at another hospital.

Table 4. Lymph node metastasis (LNM) cases (n = 3 lesions).

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | |

|

Endoscopic findings and technical results

Location Macroscopic type Tumor size (mm) Procedure Number of resected specimens |

Hypopharynx 0-IIa 20 EMR 4 |

Hypopharynx 0-IIa 12 EMR 1 |

Hypopharynx 0-IIa 15 EMR 2 |

|

Histopathological results

Tumor depth Tumor thickness, μm Lymphovascular invasion Horizontal margin Vertical margin |

SEP 3500 Positive Positive Negative |

SEP 1000 Negative Positive Negative |

SEP < 500 Negative Inconclusive Negative |

| Follow-up period until detection of LNM, months | 42 | 21 | 24 |

| Treatment for LNM | Surgery | Surgery | RT |

LNM, lymph node metastasis; EMR, endoscopic mucosal resection; SEP, subepithelium; RT, radiation therapy.

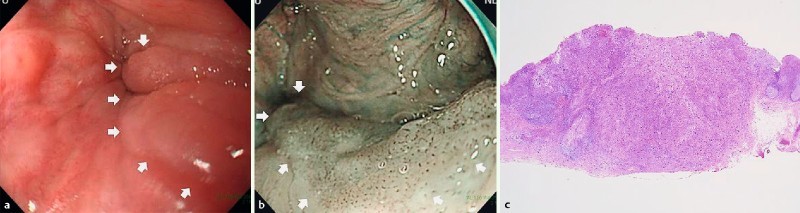

Fig. 3.

Endoscopic findings of lymph node metastasis (LNM) case-1. a, b White light and narrow-band imaging showed 0 – IIa in the left pyriform sinus of the hypopharynx. Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) was performed for this lesion. c Histopathological examination revealed subepithelial invasive cancer (3500 μm), with ly1, v1.

Table 5. Risk factors for lymph node metastasis (LNM) (n = 115).

| LMN (+) (n = 3) |

LMN (–) (n = 112) |

P value | |

| Location Oropharynx Hypopharynx |

0 3 |

24 88 |

n.s. |

| Tumor size, mm < 20 ≥ 20 |

1 2 |

89 23 |

n.s. |

| Procedure ESD EMR |

0 3 |

22 90 |

n.s. |

| Number of resections En bloc Piecemeal |

1 2 |

77 35 |

n.s. |

| Depth Epithelium Subepithelium |

0 3 |

55 57 |

n.s. |

| Tumor thickness, μm < 1000 ≥ 1000 |

1 2 |

109 3 |

< 0.005 |

| Lymphovascular invasion Negative and inconclusive Positive |

2 1 |

111 1 |

0.052 |

| Horizontal margin Negative Positive and inconclusive |

0 3 |

39 73 |

n.s. |

| Vertical margin Negative Positive and inconclusive |

3 0 |

105 7 |

n.s. |

LNM, lymph node metastasis; ESD, endoscopic submucosal dissection; EMR, endoscopic mucosal resection; n.s., not significant.

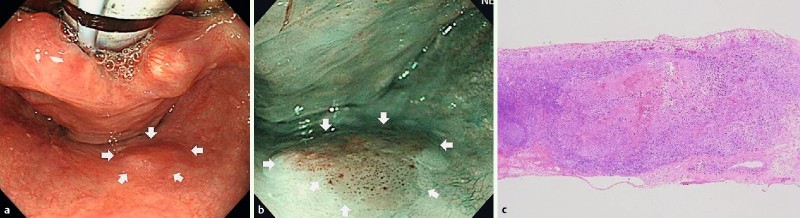

Fig. 4.

Endoscopic findings of LNM case-2. a, b White light and narrow-band imaging showed 0-IIa in the posterior wall of the hypopharynx. EMR was performed for this lesion. c Histopathological examination revealed subepithelial invasive cancer (1000 μm), with no lymphovascular invasion.

Fig. 5.

Endoscopic and CT findings of LNM case-3. a, b White light and narrow-band imaging showed 0-IIa in the left pyriform sinus of the hypopharynx. EMR was performed for this lesion. c Histopathological examination revealed slight subepithelial invasive cancer, with no lymphovascular invasion, horizontal margin positive, vertical margin negative. d Twelve months after ER, local recurrence was detected and argon plasma coagulation (APC) was performed on this lesion. e Twelve months after APC, CT showed lateral retropharyngeal lymph node enlargement.

Local recurrence occurred in seven patients (8.3 %) with eight lesions a median period of 22 months (10 – 45) after initial ER (Table 6, Fig. 2). Six lesions were located in the hypopharynx and two lesions in the oropharynx. The median size of recurrent tumors was 14 mm (9 – 30). All of these recurrent lesions were previously resected by EMR with en bloc resection in two cases and with piecemeal resection in six cases. In addition, in seven cases, invasion into the subepithelial layer was detected in the examined specimens. Neither lymphovascular invasion nor positive vertical margin were reported, but in all cases, the horizontal margin was either positive or inconclusive. The median tumor size was 6 mm (3 – 9) for recurrent lesions removed by ER, including EMR in four cases, algon plasma coaglation (APC; ERBE Elektromedizin, Tübingen, Germany) in two cases, and treated with RT in two cases. In the analysis of the risk factors, there was a statistically significant difference in the presence of positive and inconclusive horizontal margins in the group of patients with local recurrence compared to those without local recurrence (P < 0.05).

Table 6. Risk factors for local recurrence (n = 115).

| Local recurrence (+) (n = 8) |

Local recurrence (–) (n = 107) |

P value | |

| Location Oropharynx Hypopharynx |

2 6 |

22 85 |

n.s. |

| Tumor size, mm < 20 ≥ 20 |

5 3 |

86 21 |

n.s. |

| Procedure ESD EMR |

0 8 |

22 85 |

n.s. |

| Number of resections En bloc Piecemeal |

2 6 |

76 31 |

n.s. |

| Depth Epithelium Subepithelium |

1 7 |

54 53 |

n.s. |

| Lymphovascular invasion Negative and inconclusive Positive |

8 0 |

105 2 |

n.s. |

| Horizontal margin Negative Positive and inconclusive |

0 8 |

39 68 |

< 0.05 |

| Vertical margin Negative Positive and inconclusive |

7 1 |

101 6 |

n.s. |

ESD, endoscopic submucosal dissection; EMR, endoscopic mucosal resection; n.s., not significant.

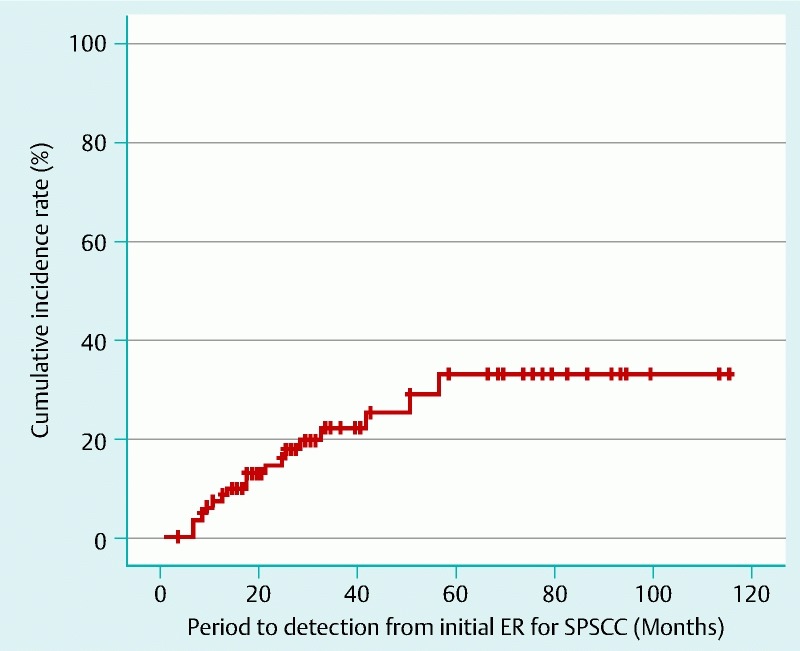

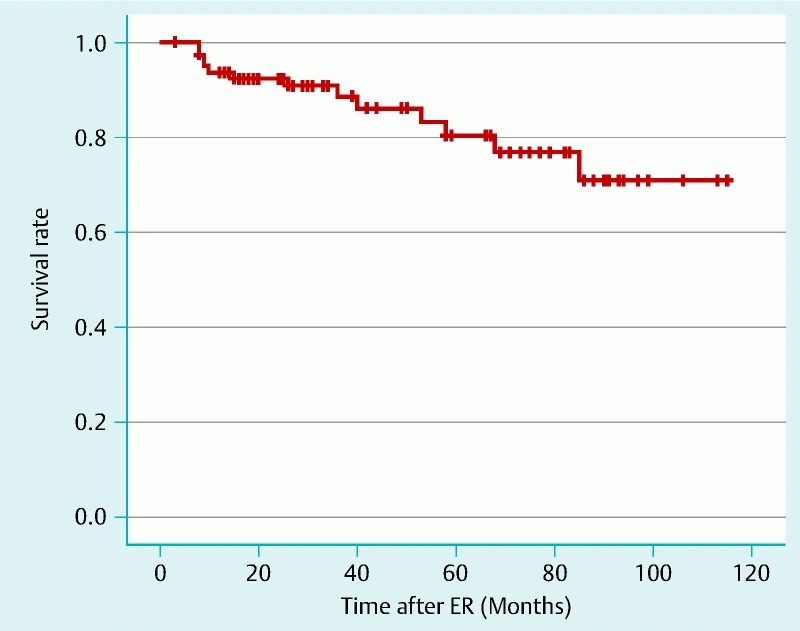

Metachronous pharyngeal SCC occurred in 18 patients (21 %) with 26 lesions a median period of 17 months (6 – 50) after initial ER. In total, 22 lesions were located in the hypopharynx and four lesions were located in the oropharynx. The median tumor size was 13 mm (5 – 50). The cumulative incidence rates at 3 and 5 years were 17.8 % and 25.3 %, respectively (Fig. 6). Regarding the treatment of these metachronous tumors, ER was performed in 17 lesions, RT in three lesions and the remaining six lesions underwent extensive surgical resection. Neither tumor-related death nor distant metastasis occurred among these patients. Metachronous esophageal SCC was also detected in 19 patients (23 %) with 29 lesions a median period of 34 months (3 – 115) after initial ER. Although 26 metachronous lesions were treated by ER and two lesions by APC is enough because of prior correction. In one case treatment has been postponed because of co-existing disease. No patient died from primary SPSCC, metachronous pharyngeal or esophageal SCC during the follow-up period. In total, 12 patients died from co-existing diseases including nine cancers (five esophageal SCCs, two lung cancers, one tongue cancer, and one cholangiocarcinoma) a median period of 31 months (8 – 85) after initial ER. The overall survival rates at 3 and 5 years were 91.1 % and 80.7 %, respectively (Fig. 7).

Fig. 6.

Cumulative incidence of metachronous pharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) after ER.

Fig. 7.

Overall survival after ER.

Discussion

This study confirms the effectiveness and safety of ER for SPSCC using EMR and ESD. Our long-term outcomes included cause of death, LNM, local recurrence, and occurrence of metachronous tumors. ESD yielded higher proportions of both en bloc and R0 resections compared to EMR in the short-term outcomes. All local recurrences were observed in patients who underwent EMR. These results are concordant with previous reports evaluating ESD as an effective and safe treatment for digestive tract cancers. Tumor thickness over 1000 μm and positive or inconclusive horizontal margins were associated with a higher risk of LNM and local recurrence, respectively. Although the long-term outcome of primary tumors was favorable with no deaths caused by SPSCC, 12 patients died from co-existing diseases including nine cases with other malignancies.

Several studies have reported that carcinoma in situ has no risk of LNM 11 12. In our study, we also showed that there was no LNM in the 56 cases of carcinoma in situ. LNM was observed in two of five cases (40 %) with a tumor thickness over 1000 μm, and one of two cases (50 %) with positive lymphovascular invasion. We found that the association between tumor thickness and LNM risk was statistically significant (P < 0.005), similarly to results previously reported by Taniguchi et al. 13. Although there was no significant association between lymphovascular invasion and LNM in this study (P = 0.052), the factor tumor thickness over 1000 μm proved to be statistically significant (P < 0.005).

Our study suggests that horizontal positive or inconclusive margins are associated with local recurrence, underlining the importance of en bloc resections. The larger size and piecemeal resections are equally associated with a higher risk of local recurrence in superficial esophageal SCC 14 15 16. One reason for a high proportion of local recurrence is probably pharyngeal anatomy with a fixed and complex structure that makes it difficult to achieve en bloc resection by EMR. But EMR can adapt for small lesions (≤ 10 mm) in the pyriform sinus of the hypopharynx or uvula of the oropharynx with a good lifting by injection, sufficient space, and a stable field to snare. Meanwhile, ESD is recommended for lesions located in other areas or larger than 10 mm in size for which en bloc resection by EMR can be difficult. Undoubtedly, ESD is a time consuming and difficult technique with a higher risk of complications than EMR 17 18. Thereupon, we have to consider the benefits of en bloc resection and adaptation of the better technique for local conditions. Considering the risk factors in our study, we perhaps should pay more attention to local recurrence after ER, especially cases with horizontal positive or inconclusive margins. In our series, local recurrences were detected a median follow up period of 22 months (10 – 45) after initial ER and could be treated with organ-preserving intervention, while Satake et al. reported a median follow-up period of 13 months (3 – 24) 19. Therefore, continuous careful follow-up and monitoring are essential for the early detection of local recurrence.

In the case of non-curative resection, guidelines for further treatment are urgently needed. Compared with gastric ESD, gastrectomy with lymph node dissection clearly improves the prognosis of patients in cases of non-curative resection 20. In the cervical region, HN surgeons can easily dissect LNM as they can be detected early by palpation and ultrasound examination. Extensive surgical resection can cause damage to speech and swallowing functions resulting in a lower quality of life for patients. However, this study shows an excellent prognosis after ER with a 5-year cause-specific survival of 100 %. There were no primary tumor-related deaths during a median follow-up period of 34 months. The overall survival rates at 3 and 5 years were 91.1 % and 80.7 %, respectively. Previous studies reported overall survival rates at 5 years as 71 – 85 % 16 19 21. According to these reassuring results, it appears necessary to clarify the indications for ER, the curative pathological criteria for ER, and the timing of RT, LNM dissection, or complementary surgery after ER.

Pharyngeal SCC is often associated with other metachronous cancers such as esophageal SCC. Our study showed extremely high proportions (94 %) of either synchronous or previous esophageal or pharyngeal SCC 21. Furthermore, metachronous esophageal and pharyngeal SCCs are respectively detected in 23 % and 21 % of cases after ER, therefore, it appears crucial to follow patients after ER for SPSCC. Continuous surveillance including endoscopy with NBI could detect metachronous pharyngeal SCC at an early stage in all cases. However, some cases could not be treated by ER because of the location close to the larynx or because of previous treatment with RT or surgery with a high risk of stenosis or respiratory issues. Selecting an appropriate method is required for the treatment of metachronous lesions. A large, multi-center cohort study is ongoing to increase our knowledge and to clarify the indications and definitions of curative resections.

This study has several limitations. First, it is a retrospective analysis in a single center. Second, depth of invasion, presence of lymphovascular invasion, and vertical/horizontal margins are sometimes inconclusive because of piecemeal resection and/or coagulation. Third, the small number of LNM cases may limit analysis of the risk factor.

Conclusions

ER for SPSCC is a feasible and effective method and should become the standard treatment based on the favorable long-term outcomes in this study. Tumor thickness over 1000 μm is a significant risk factor for LNM. A positive or inconclusive horizontal margin is a risk factor for local recurrence. This is a frequent occurrence after EMR, particularly in cases with piecemeal resection. Careful follow-up of pharynx and esophagus using endoscopy with NBI is crucial for the early detection of frequent metachronous lesions after ER.

Acknowledgment

The authors express their appreciation to Magdalena Metzner MD, and Mathieu Pioche MD for their assistance in editing this manuscript.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None

References

- 1.Muto M, Minashi K, Yano T. et al. Early detection of superficial squamous cell carcinoma in the head and neck region and esophagus by narrow band imaging: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1566–1572. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nonaka S, Saito Y. Endoscopic diagnosis of pharyngeal carcinoma by NBI. Endoscopy. 2008;40:347–351. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-995433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Inoue H, Takeshita K, Hori H. et al. Endoscopic mucosal resection with a cap-fitted panendoscope for esophagus, stomach, and colon mucosal lesions. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993;39:58–62. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(93)70012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ono H, Kondo H, Gotoda T. et al. Endoscopic mucosal resection for treatment of early gastric cancer. Gut. 2001;48:225–229. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.2.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kraus D H, Zelefsky M J, Brock H A. et al. Combined surgery and radiation therapy for squamous cell carcinoma of the hypopharynx. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;116:637–641. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(97)70240-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suzuki H, Saito Y, Oda I. et al. Feasibility of endoscopic mucosal resection for superficial pharyngeal cancer: a minimally invasive treatment. Endoscopy. 2010;42:1–7. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1243807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shimizu Y, Yamamoto J, Kato M. et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for treatment of early stage hypopharyngeal carcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:255–259. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iizuka T, Kikuchi D, Hoteya S. et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for treatment of mesopharyngeal and hypopharyngeal carcinomas. Endoscopy. 2009;41:113–117. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1119453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iizuka T, Kikuchi D, Hoteya S. et al. A new technique for pharyngeal endoscopic submucosal dissection: peroral countertraction (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:1034–1038. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Japanese Classification of Esophageal Cancer 10th edn.Tokyo, Japan: Kanehara; 200812–13. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muto M, Satake H, Yano T. et al. Long-term outcome of transoral organ-preserving pharyngeal ER for superficial pharyngeal cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:477–484. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Imai K, Tanaka M, Hasuike N. et al. Feasibility of a “resect and watch” strategy with ER for superficial pharyngeal cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:22–29. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taniguchi M, Watanabe A, Tsujie H. et al. Predictors of cervical lymph node involvement in patients with pharyngeal carcinoma undergoing endoscopic mucosal resection. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2011;38:710–717. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Makuuchi H, Shimada H, Mizutani K. et al. Analysis of long term follow up patients after endoscopic mucosal resection for early esophageal cancer: with special reference to metachronous multiple cancers [in Japanese, English abstract] Stomach Intest. 1996;31:1223–1233. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oyama T, Miyata Y, Okaniwa S. et al. Local recurrence of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma after endoscopic esophageal mucosal resection [in Japanese, English abstract] Stomach Intest. 1996;31:1217–1222. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Esaki M, Matsumoto T, Hirakawa K. et al. Risk factors for local recurrence of superficial esophageal cancer after treatment by endoscopic mucosal resection. Endoscopy. 2007;39:41–45. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-945143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okada K, Tsuchida T, Ishiyama A. et al. Endoscopic mucosal resection and endoscopic submucosal dissection for en bloc resection of superficial pharyngeal carcinomas. Endoscopy. 2012;44:556–564. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1309720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iizuka T, Kikuchi D, Hoteya S. et al. Clinical advantage of endoscopic submucosal dissection over endoscopic mucosal resection for early mesopharyngeal and hypopharyngeal cancers. Endoscopy. 2011;43:839–843. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1271112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Satake H, Yano T, Muto M. et al. Clinical outcome after ER for superficial pharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma invading the subepithelial layer. Endoscopy. 2015;47:11–18. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1378107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oda I, Gotoda T, Sasako M. et al. Treatment strategy after non-curative ER of early gastric cancer. Br J Surg. 2008;95:1495–1500. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muto M, Hironaka S, Nakane M. et al. Association of multiple Lugol voiding lesions with synchronous and metachronous esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in patients with head and neck cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:517–521. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.128104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]