Abstract

Background

Numerous sets of principles have been developed to guide the conduct of community-based participatory research (CBPR). However, they tend to be written in language that is most appropriate for academics and other research professionals; they may not help lay people from the community understand CBPR.

Methods

Many community members of the National Black Leadership Initiative on Cancer assisting with the Educational Program to Increase Colorectal Cancer Screening (EPICS) had little understanding of CBPR. We engaged community members in developing culturally-specific principles for conducting academic-community collaborative research.

Results

We developed a set of CBPR principles intended to resonate with African-American community members.

Conclusions

Applying NBLIC-developed CBPR principles contributed to developing and implementing an intervention to increase colorectal cancer screening among African Americans.

Keywords: community-based participatory research, principles, African American, cancer

INTRODUCTION

As community-based participatory research (CBPR) has gained currency among researchers and their community partners, the number of sets of guiding principles has proliferated (Table 1). One of the earliest listing of principles (eight) appeared in a review by Israel et al. (1998). Green et al. (2003) developed a 23-item checklist by which CBPR grant applications could be reviewed and rated. A review commissioned by the Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research proposed a set of 11 “critical elements” (Viswanathan et al. 2004). The organization, Community-Campus Partnership for Health (CCPH), which promotes CBPR, formulated 10 “Principles of Good Community-Campus Partnerships.” The NIH Council of Public Representatives developed 13 values for community-engaged research and 12 criteria for grant applications for research involving communities (Ahmed & Palermo, 2010). More recently, the International Collaboration for Participatory Health Research has articulated 11 characteristics of participatory health research (International Collaboration for Participatory Health Research, 2013).

Table 1.

Comparison of CBPR principles

| Principles/Characteristics of CBPR |

Israel, et al. (1998) | CCPH | Horowitz, et al. (2009) | Rhodes, et al. (2010) | NBLIC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Unit of identity | x | - | x | - | x |

| 2. | Builds on resources within the community | x | x | x | - | x |

| 3. | Equitable collaboration | x | x | - | x | |

| 4. | Mutual trust between partners | - | x | x | x | x |

| 5. | knowledge and action integration for mutual benefit of all partners | x | - | x | - | x |

| 6. | Cyclical and iterative process | x | - | - | - | x |

| 7. | Positive and ecological perspectives of health | x | x | - | - | x |

| 8. | Dissemination of findings and knowledge gained to all partners | x | - | - | x | x |

| 9. | Long - term commitment by all partners. | x | x | x | - | x |

| 10. | Promotes a co-learning and empowering process | x | x | x | x | x |

| 11. | Attends to social inequalities/ Health disparities | x | - | - | - | x |

X: principle included in the proposed CBPR structure

-: principle not included in the proposed CBPR structure

CCPH: Campus-Community Partnership for Health

NBLIC: National Black Leadership Initiative on Cancer

CBPR calls for equitable partnerships resulting in long-term commitments from researchers and communities; co-learning leading to widespread dissemination of results; and capacity building linked to systems development for sustainability. A common characteristic of CBPR principles is that they largely appear to have been written by academics in terms that reflect an academic conceptual framework. To the extent that they share this apparent bias, they may violate one or more of their own principles. The National Black Leadership Initiative on Cancer (NBLIC), headquartered at the Morehouse School of Medicine, developed an alternative approach through an interaction between the school’s academic team and its community partners. The need for more “community-developed” principles became apparent at a meeting of NBLIC participants in 2004 at which many community members professed a lack of understanding of CBPR. NBLIC staff subsequently met with NBLIC-organized community coalitions to develop an approach for explaining CBPR that resonated with non-academics. The resulting principles, which are expressed in terms familiar to African-American communities, are presented here. Also offered are examples of the way in which the principles are currently applied in a dissemination research project conducted through NBLIC community coalitions.

The National Black Leadership Initiative on Cancer (NBLIC)

With funding from the National Cancer Institute (NCI), NBLIC was established in 1986 in response to a body of literature pointing out that African-American mortality rates for each major type of cancer exceeded those for other racial and ethnic groups (Baquet & Ringen, 1986). The organization’s original leader was Dr. Louis W. Sullivan, the founding President of Morehouse School of Medicine, who served as U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services from 1986–1990. The organization carried out its mission of education, research, and service through a national network of community coalitions that included cancer survivors and advocates as well as health professionals. In 1996, NBLIC’s 24 coalitions were organized into four regions, each with a regional office.

As an NCI-funded Community Network Program (CNP), NBLIC was directed to conduct CBPR, as were the other 21 CNPs. Each of the CNPs responded to this mandate, some with more success than others (Braun, et al. 2012). In pursuit of this mandate, NBLIC developed its seven “Guiding Principles.” NCI discontinued funding of NBLIC in 2010, but most of the community coalitions have continued to function.

Educational Program to Increase Colorectal Cancer Screening (EPICS)

EPICS is the acronym for an intervention addressing the disparities in colorectal cancer mortality between African Americans and other racial/ethnic groups (29.4/100,000 in black men compared to 19.2 in white men and 13.1 in Asian men, the group with the lowest mortality rate; 19.4 in black women compared to 13.6 in white women and 9.7 in Asian women). EPICS is also the name of a cluster-randomized controlled trial to test various approaches to disseminating the intervention.

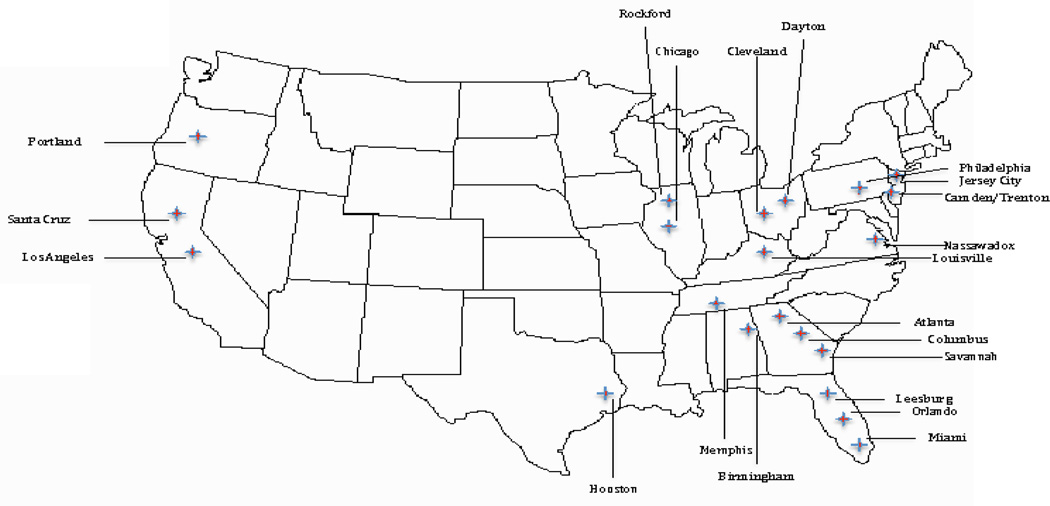

The study design and protocol for the EPICS have been described elsewhere (Smith & Blumenthal, 2013). Briefly, a 5-year, randomized controlled trial was conducted to test three interventions (one-on-one education, group education, and financial incentives) aimed at increasing colorectal cancer screening among age-eligible African-American men and women who were non-adherent on current guidelines (Blumenthal, Smith, Majett & Alema-Mensah, 2010). After the group education approach proved efficacious, a local pilot was conducted to test its effectiveness in real-world settings (Smith, et al. 2012). This evidence-based intervention was accepted for broader dissemination through the NCI’s Research Tested Intervention Programs (RTIPs). Now, 18 NBLIC community coalitions (Figure 1) are participating in the dissemination and implementation trial (Smith, & Blumenthal, 2012). The EPICS intervention was developed and tested through a CBPR project that was informed by the seven principles outlined below.

Figure 1. Educational Program to Increase Colorectal Cancer Screening (EPICS).

National Black Leadership Initiative on Cancer (NBLIC) Community Coalitions

The Seven Guiding Principles

1. We are Family

This is the title and refrain of a 1977 hit song recorded by the group Sister Sledge. The song is a classic in the pop music world, perhaps because it is a kind of theme song for community solidarity. It thus represents research that is community-based (not community-placed) and supported by the community as a whole. This resonates with the historical context of the Black community. This principle is similar to Principle #1 of Israel, et al. (1998) “Recognizes community as a unit of identity.” CBPR provides a cooperative framework for working toward a common goal. Similar to a family, CBPR is based on an understanding of and respect for divergent interests within partnerships and communities. Mutuality allows researchers and communities, despite their differences, to address a health problem important to both. Although NBLIC community coalitions participating in EPICS share an affiliation, they vary in size and composition. Some are relatively large and comprised primarily of health professionals who are representatives of health care institutions and agencies such as health departments; others are smaller and comprised primarily of cancer advocates and cancer survivors. The former have more formal infrastructures; the latter tend to be less structured and more informal. Diversity of size and composition of NBLIC community coalitions has assisted investigators in understanding the trajectory of decision-making over time required to implement EPICS in real-world settings, thus allowing documentation of the process by which stakeholders and targeted settings are involved in the implementation process.

2. It Takes a Village

The African proverb, “It takes a village to raise a child” became well known as the title of a book written by then-First Lady Hillary Rodham Clinton in 1996. In the context of CBPR principles, it represents the mutual trust established between investigators, stakeholders, and the community so that all partners function as if they constituted a village. The ‘village’ facilitates co-learning, shared decision-making, and mutual ownership of the problem and its solutions. This is similar to Community-Campus Partnerships for Health (CCPH) Principle #2: “The relationship between partners is characterized by mutual trust, respect, genuineness, and commitment.” A growing consensus is that, for translation of evidence-based interventions, they must be implemented with methods engaging partners and stakeholders that treat their expertise and perspectives with equal weight to those of researchers. The principle of ‘village,’ as defined in NBLIC collaboration, includes organizational partners in the EPICS cluster-randomized controlled trial. Community coalitions participating in the study recruited at least three community stakeholders (i.e., church, clinic, and community site) to serve as settings for EPICS implementation. A total of 67 community partners are currently enrolled in the trial, partnering with facilitators trained by researchers to deliver colorectal cancer screening education in their communities.

3. Come as You Are

This phrase, originally a party invitation, has been used in popular as well as gospel music. It describes our call to the community and indicates the willingness of academic researchers to meet their community partners on their own turf and on their own terms. It rejects the proposition that the community must assume a posture of “readiness” in order to participate equitably in the research process. For scientists and community leaders, the goal is to enhance communities by empowering them to become full participants in research. This principle can be viewed as similar to CCPH Principle #3: “The partnership builds upon identified strengths and assets, but also addresses areas that need improvement.” This principle is demonstrated by EPICS facilitators, which include community health educators (CHEs) (i.e., agency staff with degrees in a health profession) or community health workers (CHWs) (i.e., community health advisors, natural helpers, and frontline workers without college or graduate school education in a health profession). For EPICS, individuals consenting to serve as facilitators (CHEs, n=97; and CHWs, n=111) participated in a one-and-a-half day training workshop that introduced basic vocabulary, concepts, and methods of community-based cancer control and instructional strategies to individuals of varying health literacy (August-November, 2012). A workshop was conducted at each of the 18 community coalition sites.

4. Just Stand

This is a refrain from a gospel song. In the CBPR context, it points out that current research ‘stands on’ or is grounded in past research. With each new research cycle, new questions are expected to emerge from the research itself. Such an approach is cyclic, converging on a better understanding of processes as well as outcomes. This principle is comparable to Principle #6 of Israel, et al. (1998): “Involves a cyclical and iterative process,” which suggests that the process is not stagnant, but one that involves rounds of review, reflection, and revision before researchers and communities are satisfied with the outcomes. Down Home Healthy Living (DHHL), for example, was initiated as a local program by the NBLIC Philadelphia community coalition in 1999; implemented as a best practice by other community coalitions in 2000–2002; and tested as a small group education intervention in 2002–2008. It is currently disseminated as EPICS, an evidence-based intervention. Results of this 15-year process are reflected in the “Just Stand” principle, which supports maintaining direct and extended involvement with the community, building on past success, and not rushing the process of intervention development.

5. Health, Wholeness & Healing

This reflects the fact that most communities have little interest in being studied; however, they are concerned about education, jobs, health care, and other services – entities that will improve community health. Research must ensure that individuals have the opportunities, knowledge, attitudes, and skills needed for optimal health. Researchers who wish to conduct observational studies must be able to describe how their research will lead to an intervention or policy change that will improve community health. This resembles Principle #4 of Israel, et al (1998): “Integrates knowledge and action for mutual benefit of all partners.” NBLIC promotes an ecological approach to health, emphasizing physical, mental, and social well - being. Principle #5 is demonstrated in EPICS in several ways. First, in the context of cancer prevention, additional modifiable behaviors (i.e., dietary intake and physical activity) are included in the intervention curriculum. EPICS includes three one-hour educational sessions; session two, which is the most popular, focuses on nutrition and exercise. The initial goal was to partner with colorectal cancer screening providers; based on the needs of their communities, community coalitions requested an expanded listed of clinical partners for the trial. This expansion led to greater intervention dissemination than in our initial study, which resulted in fewer enrollments in clinical settings. Finally, NBLIC community coalitions have integrated EPICS into other organizational efforts. For example, in their partnership with senior citizen centers, the Florida coalition has delivered EPICS as a component of its SISTAAH Talk breast cancer support group, reaching more participants than coalitions without such integration. In order to partner with communities, researchers listen to community partners, understand the context, and develop a shared approach for implementation of the intervention.

6. Go Tell it on the Mountain

This is the title and refrain of a Negro Christmas spiritual. It reminds us of the role of the community in disseminating the results of CBPR, including scientific publications (which may be of less interest to the community), the popular media (e.g., newspapers, radio, organizational newsletters, and magazines), and policymakers. It reflects Principle #8 of Israel, et al. (1998): “Disseminates findings and knowledge gained to all partners.” For years, community members have participated in studies from which they did not see results or experience benefits. Since its inception, NBLIC has distributed information through relevant community channels appropriate to its communities. For researchers, this means peer-reviewed publications, scientific presentations, books, and reports; for communities, popular magazines, radio, church gatherings, and word-of-mouth. A shared data plan promotes co-ownership of data between researchers and communities. Additionally, this policy includes at least one NBLIC community coalition leader to contribute to and serve as a co-author on all EPICS publications, as is the case in the present paper.

7. We Shall Overcome, Someday

The civil rights anthem brings to mind the overriding goal of CBPR in the African-American community: reducing and eliminating the health disparities that plague this community. Mortality rates for African Americans are higher than those for other racial and ethnic groups for major causes of death. This must be overcome. This principle is relatively unique to NBLIC, partly because it reflects outcome rather than process and partly because it focuses particularly on racial/ethnic health disparities. The investigators and NBLIC community coalitions involved in EPICS have been addressing colorectal cancer screening disparities for more than a decade. From intervention development, to testing and dissemination, they have continued to address a disparity that leads to preventable morbidity and mortality in the African American community. Beyond current funding, our goal is to integrate EPICS so that its resources—toolkit, implementation protocol, and curriculum (all available on the RTIPs website) become integrated into NBLIC community coalition activities.

DISCUSSION & CONCLUSIONS

CBPR is an approach to conducting research rather than a research design or method. Many observers and researchers have offered sets of principles that help to define the approach, and, although no two sets are exactly alike, they have much in common. One commonality is their relatively elevated degree of erudition, which may make at least some of the principles relatively remote to community partners.

The NBLIC developed a set of principles that resonate well in the African-American community and, because they reflect familiar themes, are readily committed to memory. They are fewer in number than the principles listed in other compilations but nonetheless capture the important points. Since they emphasize trust and solidarity, they support the CBPR approach without necessarily specifying details.

Like other sets of CBPR principles, these seven do not represent an algorithm or recipe for conducting community-based research. Rather, these principles, and others, help define the approach that researchers and community partners take in designing and implementing research projects. They may be consulted as protocols are drawn up and, subsequently, they may be used as criteria against which a project may be measured to determine the extent to which it is truly community-based (or community-centered) and participatory (Braun, K. L., 2012).

This report describes how one set of principles – designed for application in the African-American community – was used in developing and implementing a CBPR project. A potential limitation of these principles is that they may only resonate well in the African-American community; they would likely not be as familiar to members of, for instance, Haitian, Afro Carribean, Hispanic, Asian, Pacific Islander or Native American communities. This report on efforts by NBLIC and EPICS staff to develop CBPR principles for the African American community will hopefully interest other communities and cultures that may wish to consider similarly norming CBPR principles to their own contexts and traditions. A similar community-based participatory process could be used to create similarly guiding principles that are tailored to specific cultural traditions.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the National Cancer Institute (1R01CA166785-01).

References

- 1.Ahmed SM, Palermo AGS. Community engagement in research: frameworks for education and peer review. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(8):1380–1387. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.178137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baquet C, Ringen K. Cancer control in blacks: epidemiology and NCI program plans. Progress in clinical and biological research. 1986;216:215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blumenthal DS, Smith SA, Majett CD, Alema-Mensah E. A trial of 3 interventions to promote colorectal cancer screening in African Americans. Cancer. 2010;116(4):922–929. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braun KL, Nguyen TT, Tanjasiri SP, Campbell J, Heiney SP, Brandt HM, Hébert JR. Operationalization of community-based participatory research principles: assessment of the National Cancer Institute's Community Network Programs. American journal of public health. 2012;102(6):1195–1203. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Community-Campus Partnerships for Health: Principles of Good Community-Campus Partnerships. https://depts.washington.edu/ccph/pdf_files/summer1-f.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Green LW, George MA, Daniel M, Frankish CJ, Herbert CP, Bowie WR, O’Neill M. Guidelines for participatory research in health promotion. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. Vol. 27. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2003. p. 52. [Google Scholar]

- 7.International Collaboration for Participatory Health Research (ICPHR) Version: May 2013. Berlin: International Collaboration for Participatory Health Research; 2013. Position Paper 1: What is Participatory Health Research? [Google Scholar]

- 8.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual review of public health. 1998;19(1):173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith SA, Blumenthal DS. Community Health Workers Support Community-based Participatory Research Ethics:: Lessons Learned along the Research-to-Practice-to-Community Continuum. Journal of health care for the poor and underserved. 2012;23(4 Suppl):77. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2012.0156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith SA, Blumenthal DS. Efficacy to effectiveness transition of an Educational Program to Increase Colorectal Cancer Screening (EPICS): study protocol of a cluster randomized controlled trial. Implementation Science. 2013;8(1):86. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith S, Johnson L, Wesley D, Turner KB, McCray G, Sheats J, Blumenthal D. Translation to practice of an intervention to promote colorectal cancer screening among African Americans. Clinical and translational science. 2012;5(5):412–415. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-8062.2012.00439.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Viswanathan M, Ammerman A, Eng E, Garlehner G, Lohr KN, Griffith D, Whitener L. Community-based participatory research: Assessing the evidence: Summary. 2004 http://depts.washington.edu/ccph/principles.html#principles. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]