Abstract

Over the past 20 years, the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) has regularly published and annually updated a global strategy for asthma management and prevention that has formed the basis for many national guidelines. However, uptake of existing guidelines is poor. A major revision of the GINA report was published in 2014, and updated in 2015, reflecting an evolving understanding of heterogeneous airways disease, a broader evidence base, increasing interest in targeted treatment, and evidence about effective implementation approaches. During development of the report, the clinical utility of recommendations and strategies for their practical implementation were considered in parallel with the scientific evidence.

This article provides a summary of key changes in the GINA report, and their rationale. The changes include a revised asthma definition; tools for assessing symptom control and risk factors for adverse outcomes; expanded indications for inhaled corticosteroid therapy; a framework for targeted treatment based on phenotype, modifiable risk factors, patient preference, and practical issues; optimisation of medication effectiveness by addressing inhaler technique and adherence; revised recommendations about written asthma action plans; diagnosis and initial treatment of the asthma−chronic obstructive pulmonary disease overlap syndrome; diagnosis in wheezing pre-school children; and updated strategies for adaptation and implementation of GINA recommendations.

Short abstract

This paper summarises key changes in the GINA global strategy report, a practical new resource for asthma care http://ow.ly/ObvYi

Introduction

Asthma is a serious global health problem affecting all age groups, with global prevalence ranging from 1% to 21% in adults [1], and with up to 20% of children aged 6–7 years experiencing severe wheezing episodes within a year [2]. Although some countries have seen a decline in asthma-related hospitalisations and deaths [3], the global burden for patients from exacerbations and day-to-day symptoms has increased by almost 30% in the past 20 years [4]. The impact of asthma is felt not only by patients, but also by families, healthcare systems and society. Asthma is one of the most common chronic diseases affecting children and young adults, and there is increasing recognition of its impact upon working-age adults, the importance of adult-onset asthma, and the contribution of undiagnosed asthma to respiratory symptoms and activity limitation in the elderly.

The Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) was established in 1993 in collaboration with the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute and the World Health Organization, under the leadership of Drs Suzanne Hurd and Claude Lenfant, with the goals of disseminating information about asthma management, and providing a mechanism to translate scientific evidence into improved asthma care. The landmark report “Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention”, first published in 1995 [5] and annually updated on the basis of a routine review of evidence, has formed the basis for clinical practice guidelines in many countries.

Substantial advances have been made in scientific knowledge about the nature of asthma, a wide range of new medications, and understanding of important emotional, behavioural, social and administrative aspects of asthma care. However, in spite of these efforts, and the availability of highly effective therapies, international surveys provide ongoing evidence of suboptimal asthma control [6–8] and poor adherence to existing guidelines [9–11]. New approaches are needed.

Since the last major revision of the GINA report in 2006 [12], there has been a transition in understanding of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) as heterogeneous and sometimes overlapping conditions, awareness of the contribution of common problems such as adherence, inhaler technique and health literacy to poorly controlled asthma, an expanding research evidence base that incorporates highly controlled efficacy studies, pragmatic studies and observational data in broad populations [13], increasing interest in individualised healthcare, and growing attention to effective strategies for changing health-related behaviour. This context is reflected in key changes in evidence, recommendations and format in the major revision of the GINA strategy report that was published in May 2014, and further updated in April 2015.

The aim of this article is to summarise the key changes in the GINA strategy report, with a description of the rationale for each change and a sample of clinical tools from the full report. More detail about clinical recommendations and supporting evidence, and the full range of clinical tools, are available in the latest update of the full GINA report (published in April 2015), which is available from the GINA website (www.ginasthma.org).

Methodology

Work on the GINA revision by members of the GINA Science Committee and Dissemination and Implementation Committee began in 2012. An over-arching aim was to substantially restructure the report in order to facilitate its implementation in clinical practice, while maintaining the existing strong evidence base. Recognising that key images and tables in the report would have the greatest impact, we began by soliciting broad input on three areas: the definition of asthma, assessment of asthma control, and control-based management. Members of the multinational GINA Assembly, primary care clinicians, respiratory specialists and other expert advisers were asked to provide feedback about existing GINA materials on these topics, with regard to their evidence, clarity and feasibility for implementation in clinical practice, and to identify other sections in need of substantial revision. Over 50 responses were received. Following this initial scoping process, the report text was revised, and new figures and tables drafted to communicate key clinical messages; new evidence from the routine twice-yearly review of new research by the Science Committee in 2012–13 was also incorporated, and a chapter providing interim clinical advice about the asthma−COPD overlap syndrome (ACOS) was developed in collaboration with the Science Committee of the Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD; www.goldcopd.org). Importantly, the clinical relevance of recommendations, and strategies for their implementation, were considered in parallel with the review of scientific evidence.

The final draft of the report was extensively peer-reviewed, with strongly supportive feedback received from over 40 reviewers including seven external reviewers. The report was published on World Asthma Day in May 2014, with an update of new evidence in April 2015. Copies of past GINA reports and pocket guides, and a tracked-changes copy of the 2015 report are archived on the GINA website (www.ginasthma.org).

A new approach: practical, practice-oriented and evidence-based

Providing a summary of evidence about asthma care is not sufficient to change outcomes; there is now a strong evidence base about effective (and ineffective) methods for implementing clinical guidelines and achieving behaviour change by health professionals and patients [14]. Evidence-based recommendations need to be presented in a way that is both accessible and relevant to clinicians, and integrated into strategies that are feasible for health professionals to use in their busy clinical practice. The GINA report, therefore, now focuses not only on the existing strong evidence base about what treatment should be recommended, but also on clarity of language and on inclusion of clinical tools (evidence-based where possible) for how this can be done in clinical practice. Recommendations are now presented in a user-friendly way, with clear language and extensive use of summary tables, clinical tools and flow-charts. The electronic report includes hyperlinked cross-references for figures, tables and citations. The main report includes the rationale and evidence levels for key recommendations, with more detailed supporting material and information about epidemiology, pathogenesis and mechanisms moved to an online appendix. The result is a report that is less like a textbook, and more like a practical manual, that can be adapted to local social, ethnic, health system and regulatory conditions for national guidelines. Additional resources including pocket guides and slide kits are also available on the GINA website (www.ginasthma.org).

Chapter 1: Definition, description and diagnosis

Key changes

• A new definition of asthma

• Practical tools

Clinical flow-chart for diagnosis of asthma and table of diagnostic criteria

Advice about confirming asthma diagnosis in patients already on treatment, and in special populations, including pregnant women and the elderly

Rationale for change

Improving the diagnosis of asthma is the first step to improving outcomes. At a global level asthma is both under- [2] and over-diagnosed [15–18], with under-diagnosis contributing to unnecessary burden for patients and families and increased costs for the health system, and over-diagnosis increasing treatment costs and exposing patients to unnecessary risk of side-effects. Past “definitions” of asthma have been lengthy descriptions, focusing on types of inflammatory cells, hyperresponsiveness, symptoms, and the assumed relationship between these features. A key priority for GINA was that the new definition should be feasible for use in diagnosing asthma in clinical practice, while also reflecting the complexity of asthma as a heterogeneous disease; the definition also needed to display flexibility within the context of rapidly emerging evidence that different mechanisms underlie the cardinal clinical features of variable respiratory symptoms and variable expiratory airflow limitation by which asthma is defined.

The new definition of asthma. “Asthma is a heterogeneous disease, usually characterized by chronic airway inflammation. It is defined by the history of respiratory symptoms such as wheeze, shortness of breath, chest tightness and cough that vary over time and in intensity, together with variable expiratory airflow limitation.” The term “asthma” is now deliberately used as an umbrella term like “anaemia”, “arthritis” and “cancer”; these terms are very useful for communication with patients and for advocacy, and they facilitate clinical recognition of heterogeneous diseases that have readily recognisable clinical features in common. By contrast with anaemia, arthritis and cancer, evidence about the underlying mechanisms in asthma is much less well-established, with most existing evidence coming from patients with long-standing and clinically severe asthma; further research in broader populations is needed. However, an overarching principle in the new GINA report is the importance of individualising patient management not only by using genomics or proteomics, but also with “humanomics” [19], taking into account the behavioural, social and cultural factors that shape outcomes for individual patients.

The word “usually” in the definition of asthma has concerned some readers. The rationale is that, although chronic airway inflammation is characteristic of most currently known asthma phenotypes, the absence of inflammatory markers should not preclude the diagnosis of asthma being made in patients with variable expiratory airflow limitation and variable respiratory symptoms. This should not be taken to suggest a lesser emphasis on anti-inflammatory treatment; on the contrary, as described below, indications for inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) treatment have been expanded. Importantly, the definition also avoids past assumptions about the relationship between airway inflammation, airway hyperresponsiveness, symptoms and exacerbations, and the inclusion of heterogeneity in the definition reinforces the need for ongoing research to identify specific treatment targets [20].

Practical tools for diagnosis of asthma. The key changes in this section are consequent upon the new definition of asthma, and are aimed at reducing both under- and over-diagnosis. There is an emphasis on making a diagnosis in patients presenting with respiratory symptoms, preferably before commencing treatment, and on documenting the basis of the diagnosis in the patient's medical records. The chapter includes a table of specific criteria for documenting variable expiratory airflow limitation, a key component of asthma diagnosis, for use in clinical practice or clinical research. Other tests used in diagnosis of asthma are described in the report and appendix, with a reminder that statements in the literature about the sensitivity and specificity of “diagnostic” tools must be interpreted in the light of the definition of asthma that was used and the population that was studied; many studies, particularly those in which physician diagnosis was the gold standard, have primarily included patients with a classical allergic asthma phenotype. A list of common asthma phenotypes is provided, to prompt clinicians, including those in primary care, to recognise different clinical patterns among their patients, even if they lack access to complex investigations.

Confirming the diagnosis of asthma in patients already on treatment. Evidence to support a diagnosis of asthma is often not documented in case notes, and over-diagnosis is common (25–35%) in developed countries [15–18]. Different approaches are suggested for confirming the diagnosis in patients already on treatment, depending on their clinical status. Advice is provided about how to step down treatment if needed for diagnostic confirmation, based on available evidence and practical considerations, such as ensuring the patient has a written asthma action plan, and choosing a suitable time (no respiratory infection, not travelling, not pregnant).

Diagnosis of asthma in special populations (e.g. pregnancy, occupational asthma, older patients, smokers and athletes). These sections are consistent with the emphasis in GINA on tailoring asthma management for different populations.

Chapter 2: Assessment of asthma

Key changes

• Asthma control is assessed from two domains: symptom control and risk factors

• Lung function is no longer included among symptom control measures, but after diagnosis it is used primarily for initial and ongoing risk assessment

• Asthma severity is a retrospective label, assessed from treatment needed to control asthma

• Practical tools

Template for assessing asthma control, including key risk factors

Clinical algorithm for distinguishing between uncontrolled and severe refractory asthma

Rationale for change

A combined approach to assessment of asthma control from both “current clinical control” (symptoms, night waking, reliever use and activity limitation) and “future risk” (risk of exacerbations, development of fixed airflow limitation or medication side-effects) was adopted in GINA 2010, following the recommendations of an American Thoracic Society (ATS)/European Respiratory Society (ERS) task force [21]. The significance of this change was not necessarily obvious, since in typical allergic asthma and with a conventional ICS-based treatment model, short-term improvement in symptoms is often paralleled by longer-term reduction in exacerbations. However, in different asthma phenotypes or with different treatments, discordance may be seen between symptoms and risks. For example, symptoms can be reduced by placebo [22] or with long-acting β2-agonist (LABA) monotherapy [23, 24], without any reduction in the risk of exacerbations from untreated airway inflammation; and newer regimens or treatments such as ICS/formoterol maintenance and reliever therapy [25] and anti-interleukin (IL)-5 [26] reduce exacerbation risk with little difference from comparators in levels of symptom control. Discordance in treatment response between symptoms and risk can be biologically informative about the underlying mechanism [27].

Asthma control is assessed from two domains: symptom control and risk factors. The previous term, “current clinical control” was renamed “symptom control”, to emphasise its relatively superficial nature. The template for assessing asthma control now includes an expanded list of modifiable and non-modifiable factors that are predictors of risk for future adverse outcomes, independent of asthma symptoms. Given the diverse mechanisms underpinning these various risks, and that not all risk factors require a step-up in asthma treatment, symptoms and risk factors were not combined arithmetically or in a grid.

Lung function and symptoms should be considered separately. In the GINA assessment of asthma control, lung function is no longer numerically combined with symptoms, as low or high symptoms can outweigh a discordant signal from lung function [24], instead of prompting a different response. For example, if symptoms are frequent and lung function normal, alternative or comorbid causes such as vocal cord dysfunction should be considered; if symptoms are few but lung function is low, poor perception of airflow limitation or a sedentary lifestyle should be considered. The between-visit variability in forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) (up to 12% week to week and 15% year-to-year in healthy individuals, and higher in patients with airway disease [28]) substantially limits its utility for adjusting treatment, so once the diagnosis of asthma has been confirmed, spirometry is primarily useful for identifying patients at increased risk of exacerbations [29, 30].

Peak expiratory flow (PEF) monitoring may be used short-term in the diagnosis of asthma, including work-related asthma [31], and in assessing triggers, flare-ups and response to treatment. Long-term PEF monitoring is largely reserved for patients with more severe asthma, those with impaired perception of airflow limitation, and other specific clinical circumstances. When PEF is used, data should be displayed on a standardised chart with low aspect ratio to avoid misinterpretation [32].

Asthma severity is a retrospective label, assessed after a patient has been on treatment for at least several months [21]. The recommendations about assessment of severe asthma follow the 2014 ERS/ATS task force guidelines [33], with the caution that the task force lung function criterion (a pre-bronchodilator FEV1 of <80% predicted in the previous year) may lead to over-classification of asthma as severe.

A clinical algorithm for distinguishing between uncontrolled asthma and severe refractory asthma. Specialist protocols for identifying severe refractory asthma often start with confirmation of the diagnosis of asthma [34]. The GINA report takes a more pragmatic approach, with the algorithm starting with the most common causes of uncontrolled asthma, namely incorrect inhaler technique (up to 80% of patients) [35] and poor adherence (at least 50% of patients) [36]. This is an efficient approach, as these problems are often readily identifiable, can be corrected in primary care [37], and, if improved inhaler technique and adherence lead to substantial improvements in symptoms and lung function, may avoid the need for additional investigations or specialist referral to confirm the diagnosis of asthma.

Chapter 3: Treating to control symptoms and minimise future risk

Key changes

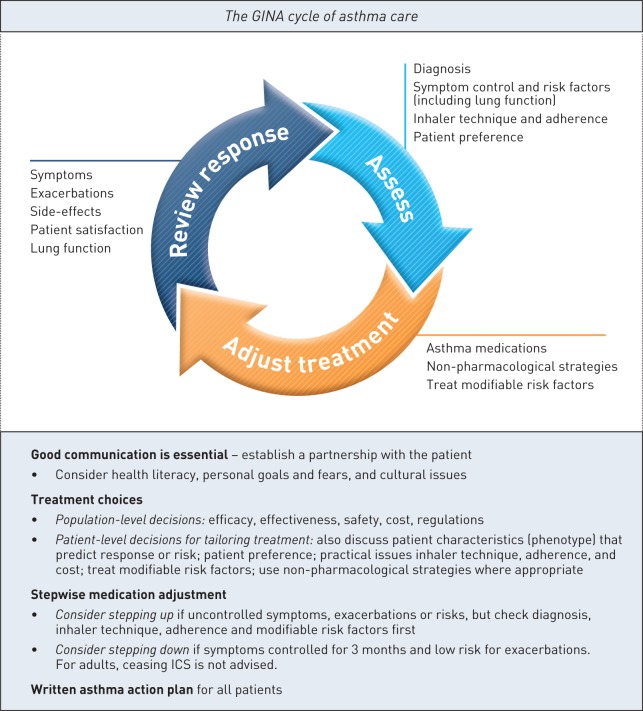

• A control-based asthma management cycle (assess – adjust treatment – review response), to prompt a comprehensive but clinically feasible approach (figure 1)

FIGURE 1.

The Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) control-based cycle of asthma care. This figure highlights key priorities in management of asthma in the GINA global asthma strategy. Further details can be found in boxes 3–3 and 3–5 in the full GINA 2015 report (“Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention”), available online (www.ginasthma.org). ICS: inhaled corticosteroids. Figure modified with permission of GINA.

• An explicit framework for tailoring treatment to individual patients

• New indications for initial controller treatment, including in mild asthma

• A strong emphasis on checking diagnosis, inhaler technique and adherence before considering any treatment step-up

• Advice about tailoring treatment for special populations and clinical contexts

• Practical tools

Strategies to reduce the impact of impaired health literacy

A new stepwise treatment figure, visually emphasising key concepts

Current options for stepping down treatment

Treatment of modifiable risk factors

Non-pharmacological interventions

Indications for referral for expert advice

Strategies to ensure effective use of inhaler devices

How to ask patients about their adherence

Summary of investigations and management for severe asthma

Rationale for change

In clinical practice, a common response to uncontrolled asthma is to step up treatment, with an attendant increase in healthcare costs and risk of side-effects; yet, as highlighted in the previous section, there are many modifiable contributors to both uncontrolled symptoms and exacerbations. There was a general perception that asthma guidelines over-emphasised pharmacological treatment, and promoted a “one-size-fits-all” approach to asthma management. The latter concern also applied to the prominence previously given to avoidance of asthma “triggers”. While avoidance strategies are essential in some contexts, such as occupational asthma or confirmed food allergy, broad avoidance recommendations may lead to the perception that all patients should avoid anything that provokes their asthma symptoms. This could not only unwittingly discourage healthy behaviour, such as physical activity or laughing, but could also contribute unnecessary burden and/or cost for patients. During the review process, many contributors also requested advice about how to implement treatment recommendations in clinical practice.

Control-based care. Figure 1 summarises key concepts in the GINA cycle of asthma care. “Assess” includes not only symptom control (e.g. with tools such as Asthma Control Test [38] or Asthma Control Questionnaire [39]), but also risk factors, inhaler technique, adherence and patient preference, to ensure that treatment can be tailored to the individual. “Adjust treatment” (up or down) includes not only medications but also non-pharmacological strategies and treatment of modifiable risk factors. “Review response”, including side-effects and patient satisfaction, is essential to avoid over- or under-treatment.

Alternative strategies for adjusting treatment are briefly described, including sputum-guided treatment, which is currently recommended for patients in centres that have routine access to this tool; the benefits are primarily seen in patients with more severe asthma requiring secondary care.

An explicit framework for tailoring treatment. The GINA report now draws a clear distinction between population-level (e.g. national guidelines, health maintenance organisations) and patient-level treatment decisions. The former are generally based on group mean data for symptoms, lung function and exacerbations, as well as safety, availability and overall cost. By contrast, when choosing between options for individual patients, clinicians should also take into account patient phenotype or characteristics that may predict their risk of exacerbations and/or treatment response (e.g. age, smoking status, sputum eosinophils if available), as well as patient preference, and practical issues of inhaler technique, adherence and cost to the patient. The extent to which treatment can be tailored depends on local regulations and access, and is limited at present by lack of long-term evidence in broad populations.

Expansion of the indication for low dose ICS. During the review of evidence for stepwise treatment options, Step 1 treatment (as-needed short-acting β2-agonist (SABA) alone) emerged as having the weakest evidence, although SABA is obviously better than placebo for short-term relief of asthma symptoms. Despite the long-standing acceptance of asthma as a chronic inflammatory condition, and evidence of airway inflammation even in so-called “intermittent” asthma (e.g. [40]), the past criteria for commencement of Step 2 treatment with ICS for “persistent” asthma appear to have been based on historical perceptions of a lack of risk for patients with symptoms less than 1–3 days per week. The GINA approach is based on evidence for the benefits of low dose ICS, including the halving of the risk of asthma-related death [41] and reduction in asthma-related hospitalisations by one third [42] in large nested case−control studies of unselected asthma populations, the halving of risk of severe exacerbations in the START study, in which almost half of patients reported symptoms less than 2 days per week at baseline [43], and the benefits seen in small studies in so-called “intermittent” asthma [44, 45]. By contrast, there is a lack of evidence for safety of treating asthma with SABA alone. GINA now recommends that treatment with SABA alone should be reserved for patients with asthma symptoms less than twice per month, no waking due to asthma in the past month, and no risk factors for exacerbations, including no severe exacerbations in the previous year. ICS treatment is recommended once symptoms exceed this level, not necessarily to reduce the (likely low) burden of symptoms, but to reduce the risk of severe exacerbations. Further studies are needed, including rigorous cost-effectiveness analyses based on current pricing structures.

Before considering any step-up, check diagnosis, inhaler technique, and adherence. Although most guidelines mention inhaler technique and adherence, general awareness of their importance remains low and clinical skills in their assessment poor [46]; optimisation of use of current medications is rarely included in the design of randomised controlled trials that involve stepping up for uncontrolled asthma. By contrast, there is strong evidence for the high prevalence of poor adherence and/or incorrect technique and their contribution to uncontrolled asthma [35, 36], and for the improvement in asthma control achieved with feasible primary care interventions [37, 47, 48]. In GINA, every recommendation about treatment adjustment now includes a reminder to first check inhaler technique and adherence and to confirm that the symptoms are due to asthma.

Two “preferred” regimens are recommended for ICS/LABA in Steps 3 and 4. In Step 3, low-dose budesonide/formoterol as maintenance and reliever therapy has been recommended in GINA since 2006 (and more recently expanded to beclometasone/formoterol) as an alternative to maintenance low-dose ICS/LABA with as-needed SABA, but to avoid confusion, both regimens are now explicitly shown in the stepwise treatment figure and the accompanying text.

Special populations and clinical contexts. The emphasis on tailoring treatment includes a summary of management in special contexts (surgery, exercise-induced bronchoconstriction); for patients with comorbidities (e.g. obesity, anxiety, rhinosinusitis); and in special populations (e.g. elderly, aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease, pregnancy). Active treatment of asthma in pregnancy, with review every 4–6 weeks, is strongly recommended, with a new recommendation against down-titration of treatment during the short duration of pregnancy (except if the ICS dose is very high), because of the high priority placed upon avoiding any exacerbations in order to reduce risk to the fetus.

Several new practical tools provided in this chapter include the following.

Strategies to reduce the impact of impaired health literacy. In addition to long-standing recommendations promoting a partnership between the patient and the healthcare provider, the importance of impaired health literacy is now also emphasised, and practical evidence-based strategies [49] to help reduce its impact are provided. Examples include prioritising information from most to least important, and asking a second person (nurse, family member) to repeat key messages.

A new stepwise treatment graphic to emphasise key messages. A new stepwise treatment figure visually reinforces the link between the “assess − adjust treatment – review response” cycle (figure 1) and treatment selection. Step 2 treatment now comprises a larger component of the figure, to emphasise that most patients with asthma should be treated with, and are likely to respond to, low-dose ICS. For each step, the figure shows not only the “preferred controller choice” but also “other controller options” that may be considered in low-resource countries or as part of tailoring treatment. The two options for reliever medication are shown, i.e. SABA, or low dose ICS/formoterol for patients prescribed maintenance and reliever regimens. In the 2015 GINA update, add-on tiotropium by soft-mist inhaler is included in Step 4 and Step 5 as an “other controller option” for adults (≥18 years) with exacerbations, following regulatory approval for this indication. Key clinical messages are included beneath the stepwise figure, to ensure that it is complete in itself if the figure is viewed in isolation from the surrounding text.

A table of specific step-down options. This table includes practical advice about stepping down once asthma has been well controlled for 2–3 months, including choosing an appropriate time (no respiratory infection, not travelling, not pregnant). Step-down options based on the patient's current treatment are listed, with related evidence levels.

Treatment of modifiable risk factors. Not all risk factors require, or respond to, a step-up in asthma treatment. This table summarises interventions and evidence levels for modifiable risk factors, such as weight reduction for obesity, and smoking cessation strategies.

Non-pharmacological interventions. Recommendations about specific non-pharmacological strategies including physical activity, allergen avoidance or immunotherapy for sensitised patients, and breathing exercises are summarised in a table, with evidence levels for each. A full chapter of the online appendix is devoted to this topic, with more detail about each of the interventions and their impact on asthma outcomes.

Indications for referral. In many countries, asthma is largely managed in primary care. A table is provided, summarising in bullet-point format the clinical features that should prompt referral for expert advice.

Strategies for effective use of inhaler devices. Up to 70–80% of patients cannot use their inhaler correctly, and similar proportions of health professionals are unable to demonstrate correct use [35, 50, 51]. A mnemonic is provided for improving use of inhaler devices: Choose the most appropriate device for the individual patient and treatment, Check inhaler technique at every opportunity (ask the patient to show you how they use the inhaler rather than asking them if they know how to use it), Correct technique with a physical demonstration; and Confirm that staff can demonstrate correct technique for all inhalers.

How to ask patients about their medication adherence. Since this is such a sensitive question, specific wording is suggested for how to ask patients about their medication use in an open, non-critical way that normalises incomplete adherence [52, 53].

A summary of investigations and management for severe asthma. Readers are referred to the 2014 ERS/ATS guidelines for detailed GRADE-assessed recommendations [33]. A brief summary of investigations and management options is provided for those who lack access to specialist consultation.

Chapter 4: Management of worsening asthma and exacerbations

Key changes

• A continuum of care for worsening asthma (action plans, primary care, acute care, follow-up)

• The term “flare-up” is recommended for communication with patients

• Patients at increased risk of asthma-related death should be flagged

• An early rapid increase in ICS is recommended for action plans

• Severity of acute asthma is simplified into mild/moderate, severe, and life-threatening

• Revised recommendations for oxygen therapy, including an upper target for saturation

• Regular ICS-containing controller should be instituted or restarted after any severe exacerbation

• Practical tools

Action plan options for different controller regimens

Flow-chart for managing asthma exacerbations in primary care

Flow chart for managing asthma exacerbations in acute care facilities

Discharge management

Rationale for change

Previous GINA reports have presented recommendations about written asthma action plans within the context of asthma education, and separate from treatment of acute asthma in primary care or acute care settings. Based on feedback received from clinicians, these topics have been brought together into a single chapter in the GINA report, to provide a continuum for treatment and follow-up. A review of evidence led to new recommendations being provided about increasing controller therapy in action plans, initiating (or recommencing) ICS after severe exacerbations, and oxygen saturation targets. To enhance utility for development of clinical pathways, recommendations about management of exacerbations in primary care and acute care are summarised in new flow charts.

The term “flare-up” is now recommended for communication with patients. Although the term “exacerbations” is standard in medical literature, it is far from patient-friendly. “Attacks” is commonly used, but with such different meanings that it may cause misunderstandings [54]. For patients, the term “flare-up” was recommended, as it conveys the concept of inflammation, and signals that asthma is present even when symptoms are absent. Similar issues should be considered when recommendations are translated into other languages.

Patients at increased risk of asthma-related death should be flagged in medical notes for frequent monitoring; this was also recommended by the recent National Review of Asthma Deaths in the UK [55].

An early rapid increase in ICS now recommended for many action plans. Early guidelines recommended doubling of ICS when asthma begins to worsen. However, doubling of ICS dose was found not to be effective in three well-conducted randomised placebo-controlled trials in patients taking maintenance ICS [56–58], except possibly if the doubling led to a high ICS dose [59]. Publication of these studies led to a rapid shift in guidelines, with increasing doses of SABA considered to be sufficient until the exacerbation was severe enough to warrant the use of systemic corticosteroids.

Based on a review of all relevant evidence, GINA now recommends that an early increase in ICS dose should be advised in action plans, either by prescribing the ICS/formoterol maintenance and reliever regimen, or by a short-term increase in the dose of maintenance ICS/formoterol, or by adding an extra ICS inhaler. The rationale for these recommendations included the following considerations. Most exacerbations are characterised by increased inflammation [60, 61]; studies with doubling ICS comprise most of the strong evidence base that continues to support recommendations for asthma self-management and written asthma action plans [62]; action plans which include both increased ICS (usually doubling) and oral corticosteroids (OCS) consistently improve health outcomes but there is little evidence for benefit when OCS alone is recommended [63]; the risk of severe exacerbations is reduced by short-term treatment with quadrupled doses of ICS [64], quadrupled doses of budesonide/formoterol [65], or by a small but very early increase in ICS/formoterol with the maintenance and reliever regimen [66–68]; poor adherence with controller medications is a common precipitating factor for exacerbations [69] (adherence by community patients is often around 25% of the prescribed dose [69, 70]); the observed behaviour of people with asthma is to increase their use of controller late in the development of an exacerbation [71], and patients are known to delay seeking medical care through fear of side-effects of OCS [72]. With regard to the placebo-controlled studies themselves, the participants were required to be highly adherent with medications, visits and daily diaries, with adherence with maintenance medication of 97–98% in one study [56]); published timeline data revealed that study inhalers were not started until symptoms and airflow limitation had worsened for an average of 4–5 days [56, 57].

Further studies are needed to investigate patient attitudes and behaviours that influence use, delay or avoidance of maintenance medications and action plan recommendations when asthma worsens [71], and about ways of enhancing the delivery and use of written asthma action plans.

Exacerbation severity classification has been streamlined into mild/moderate, severe, and life-threatening. In both primary care and acute care, the initial management of mild and moderate exacerbations is the same, so they are combined into a single category.

Revised recommendations for oxygen therapy, including an upper target for saturation. Based on evidence of hypercapnia and adverse outcomes in patients with asthma given high flow oxygen [73, 74], the recommendation is now for controlled or titrated oxygen therapy where available, with a target saturation of 93–95% (94–98% for children 6–11 years).

Regular ICS-containing controller should be instituted or restarted after any severe exacerbation. As well as considering short-term outcomes when ICS controllers are given in the context of emergency department or hospital presentations [75], this recommendation is also based on evidence that any severe exacerbation increases the risk of another in the next 12 months [76], and that risk of rehospitalisation is reduced by almost 40% with regular use of ICS-containing controller [42].

Practical tools for managing worsening asthma or exacerbations in this chapter include:

A table of pharmacological options for written asthma action plans. This table, with evidence levels, provides specific action plan recommendations based on the patient's current treatment step and regimen.

Flow charts for managing asthma exacerbations in primary care and acute care. The emphasis in these flow charts is on a rapid triage assessment while bronchodilator treatment is being instituted, with a more detailed history and examination once the patient is stabilised, a review of response at 1 h or earlier, and a summary of discharge considerations.

A summary of discharge management. This includes initiating or resuming controller therapy, advice about reducing SABA use, identifying the trigger for the exacerbation, checking self-management skills and written asthma action plan, and arranging a follow-up appointment within 2–7 days.

Chapter 5: Diagnosis and initial treatment of asthma−COPD overlap syndrome

Key changes

• A new chapter aimed at providing interim practical advice for primary care and non-respiratory specialists, and as a signal to regulators that evidence is needed about treatment for patients with features of both asthma and COPD

• A syndromic approach to recognising asthma, COPD and asthma−COPD overlap syndrome (ACOS) in primary care

• Advice about safety considerations for initial treatment

• Practical tool: a stepwise approach to diagnosis and initial treatment of ACOS

• Recommendations for future research about ACOS

Rationale

In their most typical forms, “asthma” and “COPD” are clearly distinguishable. However, the diagnosis of chronic respiratory symptoms in adults can be problematic, as many patients, particularly if older or with a significant smoking history, have features of both asthma and COPD. The clinical difficulty is compounded by the fact that the definitions of asthma and COPD, published in various guidelines and in previous GINA [77] and GOLD [78] strategy reports, are not mutually exclusive, and both asthma and COPD are now accepted as being heterogeneous diseases. Depending on the definitions used and the population studied, reports of the prevalence of overlapping asthma and COPD in patients with airflow limitation and/or respiratory symptoms have ranged from 15% to 55% [79–81].

This is not an academic issue, for three important reasons. First, evidence-based guidelines for asthma and for COPD include contrasting strongly worded safety cautions about treatment of these populations. In asthma, ICS is the cornerstone of treatment based on its significant effect in reducing deaths [41], hospitalisations [42] and symptoms;[43] and there are strong recommendations against use of LABA monotherapy (i.e. without ICS) because of the risk of severe exacerbations and asthma-related death [82]. By contrast, for COPD, LABA monotherapy is actively recommended for milder disease [78], and use of ICS-only medications is discouraged because of their lower benefit/risk ratio [83]. Secondly, most of the clinical trial evidence for asthma and for COPD excludes patients with a diagnosis of both conditions; a median of only 5–7% of patients with airways obstruction would have satisfied inclusion criteria for major asthma or COPD randomised controlled trials [84], limiting the clinical relevance of such evidence. Thirdly, patients with features or diagnoses of both asthma and COPD have worse clinical outcomes than patients with either condition alone [79, 85].

For these reasons, the Science Committees of GINA and GOLD collaborated to develop a chapter for non-specialist clinicians about diagnosis and initial treatment of asthma−COPD overlap syndrome (ACOS). This was published jointly by both groups in 2014, comprising chapter 5 of the GINA report; the text was substantially revised in GINA 2015 for clarification of some of the key issues. The aims of publishing this chapter in key global strategy reports were:

1) To provide interim advice for clinicians, especially in primary care and non-respiratory specialties, such as gerontology, for identifying patients with typical asthma and typical COPD, as well as those with overlapping asthma and COPD, and for guiding initial treatment, particularly by recognising those in whom either LABA-only or ICS-only medications should be avoided for safety reasons.

2) To signal to regulators and investigators that people with overlapping asthma and COPD form a sizeable and clinically important proportion of those with chronic airflow limitation, and that these patients should be included in future randomised controlled trials.

3) To prompt further research in broad populations (not only those with existing diagnoses of asthma or COPD) about underlying mechanisms.

ACOS cannot yet be defined. Given the paucity of evidence about ACOS, the restricted populations from which most existing evidence has been obtained, and the probability that heterogeneous underlying mechanisms will be identified, GINA and GOLD decided against proposing a specific definition of ACOS at this point of time, instead providing a description for clinical use: “Asthma−COPD overlap syndrome (ACOS) is characterised by persistent airflow limitation with several features usually associated with asthma and several features usually associated with COPD. ACOS is therefore identified by the features that it shares with asthma and COPD.” Further research in broad populations is encouraged, to characterise patients satisfying this description, and to identify predictors of treatment response or risk.

The remainder of the ACOS chapter is structured around an interim practical, consensus-based approach to diagnosis and initial treatment.

Step 1: Does the patient have chronic airway disease? The initial step is a history and physical examination to establish the probability of chronic airway disease, identify potential causes, and exclude alternative diagnoses [86, 87].

Step 2: Syndromic diagnosis of asthma, COPD and ACOS. A pragmatic approach is described for clinical practice. Two lists show features that, when present, best identify typical asthma and typical COPD; the clinician checks off these features for the patient, and counts the number of check-marks in each list. Empirically, it is suggested that having three or more of the features for either asthma or COPD in the absence of features for the other provides a strong likelihood of a correct diagnosis, and that if similar numbers of features of both asthma and COPD are seen, the diagnosis of ACOS should be considered. Validation of this approach is awaited, although in nurse-led clinics, a similar approach has been used effectively for other conditions [88].

Step 3: Spirometry. Measurement of lung function, preferably by spirometry, is essential for diagnosing chronic airflow limitation, but substantial barriers exist for access to, and utility of, spirometry in primary care [89]. A balance needs to be achieved between diagnostic confirmation and clinical urgency. It is often challenging to confirm a diagnosis after treatment has been commenced, so clinicians are encouraged to document spirometry as soon as possible.

Step 4: Commence initial therapy. Little evidence is available about treatment of ACOS, as these patients have generally been excluded from pharmacological studies. The treatment recommendations here are limited to considerations for initial treatment in primary care, with a pragmatic approach that focuses on safety as well as effectiveness. Given the lack of evidence for long-term safety of treating asthma without ICS, low/moderate dose ICS are recommended if the syndromic assessment suggests asthma or ACOS, with avoidance of LABA-only monotherapy. Conversely, if ACOS or COPD is likely, treatment should include a long-acting bronchodilator (LABA and/or long-acting muscarinic antagonist), and ICS monotherapy should be avoided.

Step 5: Referral for specialised investigations (if necessary). Outcomes are worse in ACOS than in asthma or COPD alone, so referral is recommended for patients with features that suggest an alternative or additional diagnosis, those with significant comorbidities, and those who fail to respond to initial treatment.

Future research. There is an urgent need for more research, to inform an evidence-based definition of ACOS and a more precise classification, and to encourage the development of specific interventions for clinical use. Given the expected heterogeneity of underlying mechanisms in ACOS, it is important for research to start with broad populations with airflow limitation, rather than only with patients with existing diagnoses of asthma and/or COPD.

Chapter 6: Diagnosis and management of asthma in children aged 5 years and younger

Key changes

• A probability-based approach to diagnosis and treatment for wheezing children replaces previous classifications by wheezing phenotype

• Asthma control assessment includes both symptom control and risk factors

• New indications for a therapeutic trial of controller treatment

• Emphasis on checking diagnosis, inhaler technique and adherence before considering any step-up

• Caution about risk of long-term side-effects with episodic parent-administered high dose ICS

• Action plans recommended for all children with asthma

• Upper limits for OCS dosage

• Revised oxygen saturation criterion for severe exacerbations, and revised saturation target for oxygen therapy

• Nebulised magnesium sulphate an option for add-on therapy in severe exacerbations

• Practical tools

A template for assessment of symptom control and risk factors

A stepwise treatment figure, similar to that for older children and adults

A new flow-chart for assessment and management of acute flare-ups or wheezing episodes in young children

Rationale for change

Asthma is the most common chronic disease of childhood, and the leading cause of childhood morbidity (e.g. school absences, emergency department visits and hospitalisations) from chronic disease. However, recurrent wheezing also occurs in a large proportion of children aged ≤5 years, particularly with viral infections, and not all wheezing in this age group indicates asthma. Deciding when wheezing with a respiratory infection represents asthma is a clinical and research challenge, particularly in very young children or when the initial presentation is severe.

The first GINA recommendations for children ≤5 years were published in 2009 as a stand-alone report [90]. All age groups are now incorporated in the full report, in order to support continuity of care for paediatric patients, and to facilitate annual GINA evidence updates. Substantial new evidence had emerged since 2009 about diagnosis and management of airways disease in young children, resulting in some key changes in the GINA report.

In young children, no current tests can diagnose asthma with certainty. Intermittent or episodic wheezing may represent isolated viral-induced wheezing episodes, isolated episodes of seasonal or allergen-induced asthma, or uncontrolled asthma. Asthma should be considered in any child with recurrent wheezing, but parents should be advised that the diagnosis may be revised as the child grows older.

Previous wheezing phenotypes have been replaced by a probability-based approach to diagnosis and treatment. In the past, two main systems for classification of wheezing children were advocated:

1) Symptom-based classification, proposed by an ERS task force [91]: episodic wheeze (wheezing with respiratory infections, symptom-free in the interval) and multi-trigger wheeze (episodic wheezing, with interval symptoms during sleep, activity, laughing or crying).

2) Time-trend classification into transient wheeze (ending before 3 years), persistent wheeze (starting before 3 years, persisting beyond 6 years) and late-onset wheeze (starting after 3 years); this population classification was based on analysis of the Tucson birth cohort [92].

However, these phenotypes are not stable over time, and lack clinical utility in predicting the need for regular treatment [93–96]. A probability-based approach is now recommended [97], based on the frequency/severity of symptoms during and between viral infections. Children with symptoms for >10 days during viral infections, severe or frequent episodes, interval symptoms during play, laughing or crying, and with atopy or a family history of asthma, are much more likely to be given a diagnosis of asthma or to respond to regular controller treatment than children with episodes only 2–3 times per year. Most wheezing children fall into the latter group, but symptom patterns may shift over time, so diagnosis and the need for controller treatment should be reviewed regularly. This approach provides a basis for making treatment decisions for each child individually, while postponing commitment to a firm diagnosis until the child is older.

Tests for atopy may provide additional predictive support [98], but absence of atopy in a young child does not rule out asthma. Early referral is prompted for children with any features suggesting alternative diagnoses, including neonatal onset of symptoms, failure to thrive, focal signs, or failure to respond to treatment.

Predictive tools to assist in diagnosis in pre-school children. Several risk profile tools have been evaluated to predict diagnosis of asthma by school-age [94]. The Asthma Predictive Index (API) has high negative predictive value in children with four or more wheezing episodes in a year [99]. Fractional concentration of exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) is feasible from 1 year of age, and reference values for pre-schoolers are available [100]; however, variation is seen between different FeNO devices. An elevated FeNO, recorded >4 weeks after any upper respiratory tract infection in children with recurrent coughing or wheezing increases the probability of physician-diagnosed asthma at school age, but the predictive value of API is not increased by adding FeNO [101]. For new tools, validation in broader populations is needed, since in children, as in adults, asthma may include non-allergic or Th2-low phenotypes.

Assess both symptom control and risk factors. Since engaging in play is so important for normal social and physical development [102], the consensus-based criteria for good symptom control are more stringent than for older age-groups, with an emphasis on assessing and maintaining normal activity levels. As in older children and adults, assessment should include risk factors for adverse outcomes. Risk factors for exacerbations within the next few months, fixed airflow limitation, and medication side-effects, should not be confused with risk factors for development of asthma per se. The evidence base about risk factors for exacerbations in children is less well-developed than for adults, but uncontrolled symptoms, poor adherence, incorrect inhaler technique, exposures (cigarette smoke, indoor or outdoor pollution, indoor allergens) and major psychological or socio-economic problems should be considered.

A therapeutic trial with regular controller treatment for at least 2–3 months is now recommended for children whose symptom pattern suggests a diagnosis of asthma, who have severe viral-induced wheeze, or who present with wheezing more than every 6–8 weeks. It is important to discuss the reasons for the medication choice with the parent/carer, and to schedule a follow-up visit to review the response. Marked clinical improvement during treatment, and deterioration when it is stopped, may assist in confirming the diagnosis of asthma.

General principles for choice of controller medication. As for older children and adults, medications decisions for pre-schoolers should take into account not only general population-level recommendations, but also how this child differs from the “average” child, in terms of their response to previous treatment, parental preferences and beliefs, and practical issues of cost to the family, inhaler technique and adherence. Young children are excluded from many clinical trials, with recommendations dependent on extrapolation from studies in older children.

Specific asthma treatment steps. A new stepwise figure shows treatment options for pre-school children with asthma, or those needing a therapeutic trial of controller. The cycle of “assess – adjust – review response” is linked with treatment decisions, and with symptom patterns. Controller recommendations are divided into “preferred” and “other”, with more details provided in the online appendix.

Step 1: inhaled SABA should be provided for all children with wheezing episodes (whether or not a diagnosis of asthma has been made), but the response should be assessed since SABA is not effective for all children.

Step 2: as in the past, regular low dose ICS is the preferred initial controller treatment for pre-schoolers. Alternative treatments include regular leukotriene receptor antagonist (LTRA), but improvements are less consistent than with ICS. As-needed [103] and episodic high-dose [104] ICS have also been studied, but there is substantial concern about the risk of side-effects with their over-use, so regular low-dose ICS should be tried first.

Step 3: before considering a step-up, check that symptoms are not due to an alternative diagnosis or comorbidity, and that inhaler technique and adherence are good; review the response to any step-up. By contrast with adults, the recommended step up for children is to moderate dose ICS. Add-on LTRA may also be considered, based on data from older children.

Step 4: the preferred recommendation is referral for expert advice and further investigation. Therapeutic strategies include increasing ICS, or adding LTRA, theophylline or short course low dose OCS, or intermittent ICS with viral infections, but evidence is lacking for these options. ICS/LABA is not recommended for pre-schoolers, due to lack of safety data.

Initial home management of acute wheezing episodes/exacerbations. Written asthma action plans are now recommended for all children with asthma, largely based on evidence from older children. For young children, lethargy, reduced exercise tolerance or difficulty feeding may indicate worsening asthma. The recommended initial home management is with inhaled SABA by spacer with/without facemask. Urgent medical care should be sought if the child is acutely distressed, if symptoms are not relieved promptly by SABA or worsen, or, in children under 1 year, SABA is needed over several hours. There is an emphasis on monitoring of side-effects if episodic parent-initiated high-dose ICS or oral corticosteroids are prescribed, particularly given the lack of benefit seen with the latter. Evidence for benefit from commencing LTRA at the start of an upper respiratory tract infection or wheezing is mixed [105, 106].

Primary care or hospital management of exacerbations. Key changes for primary care or emergency department management of exacerbations in young children are: conducting a rapid history and examination concurrently with the initiation of therapy, and a higher cut-off point for pulse oximetry (<92%) for classification of an acute exacerbation as severe; saturation of 92–95% is also associated with higher risk [107]. The indications for immediate transfer to hospital are based on clinical signs (e.g. unable to speak or drink, subcostal retraction, silent chest), the response to initial treatment, and the social environment at home.

Emergency treatment of acute asthma or severe wheezing episodes in children ≤5 years focuses on urgent treatment of hypoxaemia (now aiming for a target oxygen saturation of 94–98%), and frequent administration of SABA by pressurised metered dose inhaler plus spacer, addition of ipratropium bromide for the first hour if needed, and frequent re-assessment. Add-on nebulised magnesium sulphate is considered in children ≥2 years with severe exacerbations, particularly with recent onset symptoms (<6 h) [108]. Recommendations about oral corticosteroids for children with severe exacerbations (1–2 mg·kg−1·day−1 for 3–5 days) have been updated with upper dosage limits (20 mg·day−1 for 0–2 years, 30 mg·day−1 for 2–5 years).

Discharge and follow-up. Earlier follow-up by the general practitioner is now recommended, within 2–7 days after discharge. Discharge recommendations, including providing parents with an action plan to recognise recurrence of symptoms, advice about medication usage, inhaler technique training, and providing a supply of medications, are continued.

Chapter 7: Primary prevention of asthma

Key changes

• Advice about primary prevention of asthma is now provided separately from advice about secondary prevention

• Specific recommendations aimed at reducing the risk of a child developing asthma

No exposure to tobacco smoke during pregnancy or after birth

Encourage vaginal delivery where possible

Discourage use of broad-spectrum antibiotics in the first year of life

• Breast-feeding is advised, but for reasons other than prevention of allergy or asthma.

Rationale for change

For clinical utility, advice about primary prevention of asthma has been separated from information about secondary prevention of symptoms in patients with an existing diagnosis of asthma. In this chapter, a summary is provided of evidence about potential factors contributing to the development of asthma, such as nutrition (breast-feeding, vitamin D, delayed introduction of solids, probiotics), exposure to allergens and pollutants, and the potential role of microbial effects, medications and psychosocial factors.

Present evidence supports the following recommendations for reducing the risk of a child developing asthma: 1) children should not be exposed to tobacco smoke during pregnancy or after birth; 2) vaginal delivery should be encouraged where possible; and 3) the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics in the first year of life should be discouraged.

Breast-feeding is still advised, but for reasons other than prevention of allergy and asthma.

Chapter 8: Implementing asthma management strategies into health systems

Key changes

• Summary of a stepwise approach to implementation of an asthma strategy

Rationale for change

Evidence-based recommendations must be disseminated and implemented at a national and local level, and integrated into clinical practice, in order to change health outcomes. As described in the introduction, the new GINA report was developed as an implementation-ready resource, with evidence for efficacy, effectiveness and safety considered in parallel with clinical utility.

A stepwise approach to implementation is described, starting with development of a multi-disciplinary working group; moving on to assessment of local asthma care delivery, care gaps and current needs; agreeing on primary goals, identifying the initial key recommendations and adapting them to the local context; identifying barriers to and facilitators for implementation; and selecting an implementation framework. This is followed by a step-by-step implementation plan, in which target populations are selected, local resources are identified, timelines are set, tasks distributed, and outcomes evaluated. A final core element is continuous review of progress to determine if the strategy needs modification, and to identify recommendations suitable for the next round of implementation.

More detailed information and advice about implementation concepts and processes is available in the GINA online appendix, in a 2012 publication entitled “A guide to the translation of the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) strategy into improved care” by Boulet et al. [14] in the European Respiratory Journal, and in implementation toolbox resources which will be published by GINA in 2015.

Future directions

The landmark Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention report published in 2014, and updated in 2015, focuses not only on the broad range of available evidence about asthma diagnosis, assessment and treatment, but also on providing practice-oriented and patient-centred recommendations in an implementation-ready format. Positive feedback from clinicians suggests that the new approach has been valued for its clinical relevance and practical utility, but we await evidence of uptake into clinical care. Work is underway on development of electronic tools and other clinical resources based on the report, in order to facilitate dissemination of the report and enhance its utility for clinical practice. As in the past, annual updates will be published based on a twice-yearly review of new evidence.

Importantly, if recommendations contained within this report are to improve the care of people with asthma, every effort must be made to encourage healthcare leaders to assure global availability of, and access to, medications, and to develop means to implement and evaluate effective asthma management programmes.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Kate Chisnall for assistance with graphics.

Footnotes

Editorial comment in: Eur Respir J 2015; 46: 579–582 [DOI: 10.1183/13993003.01084-2015]

Conflict of interest: Disclosures can be found alongside the online version of this article at erj.ersjournals.com

Support statement: During the period in which the GINA 2014 report was being prepared (2012–2013), the work of GINA was partly supported by unrestricted educational grants from the following companies: Almirall, Boehringer Ingelheim, Boston Scientific, CIPLA, Chiesi, Clement Clarke, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck Sharp and Dohme, Novartis and Takeda. Since 2014, the work of GINA has been supported only by income generated from the sale of its report, resources and related materials. Members of the GINA Committees serve in a voluntary capacity, and are solely responsible for the statements and recommendations in the GINA report and resources. Statements of interest for members of the GINA Science Committee and Board of Directors are published on the GINA website (www.ginasthma.org).

References

- 1.To T, Stanojevic S, Moores G, et al. Global asthma prevalence in adults: findings from the cross-sectional world health survey. BMC Public Health 2012; 12: 204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lai CKW, Beasley R, Crane J, et al. Global variation in the prevalence and severity of asthma symptoms: phase three of the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC). Thorax 2009; 64: 476–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2013; 380: 2095–2128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012; 380: 2163–2196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Global Initiative for Asthma. Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention. NHLBI/WHO workshop report. NIH Publication number 95-3659A. 1995. Available from www.ginasthma.org

- 6.Demoly P, Paggiaro P, Plaza V, et al. Prevalence of asthma control among adults in France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the UK. Eur Respir Rev 2009; 18: 105–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fuhlbrigge A, Reed ML, Stempel DA, et al. The status of asthma control in the U.S. adult population. Allergy Asthma Proc 2009; 30: 529–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gold LS, Thompson P, Salvi S, et al. Level of asthma control and health care utilization in Asia-Pacific countries. Respir Med 2014; 108: 271–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wisnivesky JP, Lorenzo J, Lyn-Cook R, et al. Barriers to adherence to asthma management guidelines among inner-city primary care providers. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2008; 101: 264–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Partridge MR. Translating research into practice: how are guidelines implemented? Eur Respir J 2003; 21: Suppl. 39, 23s–29s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baiardini I, Braido F, Bonini M, et al. Why do doctors and patients not follow guidelines? Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2009; 9: 228–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Global Initiative for Asthma. Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention 2006. Available from: www.ginasthma.com

- 13.Roche N, Reddel HK, Agusti A, et al. Integrating real-life studies in the global therapeutic research framework. Lancet Respir Med 2013; 1: e29–e30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boulet LP, FitzGerald JM, Levy ML, et al. A guide to the translation of the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) strategy into improved care. Eur Respir J 2012; 39: 1220–1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aaron SD, Vandemheen KL, Boulet LP, et al. Overdiagnosis of asthma in obese and nonobese adults. Can Med Assoc J 2008; 179: 1121–1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lucas AEM, Smeenk FWJM, Smeele IJ, et al. Overtreatment with inhaled corticosteroids and diagnostic problems in primary care patients, an exploratory study. Fam Pract 2008; 25: 86–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marklund B, Tunsäter A, Bengtsson C. How often is the diagnosis bronchial asthma correct? Fam Pract 1999; 16: 112–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Montnémery P, Hansson L, Lanke J, et al. Accuracy of a first diagnosis of asthma in primary health care. Fam Pract 2002; 19: 365–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.FitzGerald JM, Poureslami I. The need for humanomics in the era of genomics and the challenge of chronic disease management. Chest 2014; 146: 10–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson GP. Endotyping asthma: new insights into key pathogenic mechanisms in a complex, heterogeneous disease. Lancet 2008; 372: 1107–1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reddel HK, Taylor DR, Bateman ED, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: asthma control and exacerbations: standardizing endpoints for clinical asthma trials and clinical practice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009; 180: 59–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wechsler ME, Kelley JM, Boyd IOE, et al. Active albuterol or placebo, sham acupuncture, or no intervention in asthma. N Engl J Med 2011; 365: 119–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lazarus SC, Boushey HA, Fahy JV, et al. Long-acting beta2-agonist monotherapy vs continued therapy with inhaled corticosteroids in patients with persistent asthma: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2001; 285: 2583–2593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jenkins CR, Thien FCK, Wheatley JR, et al. Traditional and patient-centred outcomes with three classes of asthma medication. Eur Respir J 2005; 26: 36–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bateman ED, Reddel HK, Eriksson G, et al. Overall asthma control: the relationship between current control and future risk. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010; 125: 600–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pavord ID, Korn S, Howarth P, et al. Mepolizumab for severe eosinophilic asthma (DREAM): a multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2012; 380: 651–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haldar P, Pavord ID, Shaw DE, et al. Cluster analysis and clinical asthma phenotypes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008; 178: 218–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pellegrino R, Viegi G, Brusasco V, et al. Interpretative strategies for lung function tests. Eur Respir J 2005; 26: 948–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fuhlbrigge AL, Kitch BT, Paltiel AD, et al. FEV1 is associated with risk of asthma attacks in a pediatric population. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2001; 107: 61–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Osborne ML, Pedula KL, O'Hollaren M, et al. Assessing future need for acute care in adult asthmatics: the profile of asthma risk study: a prospective health maintenance organization-based study. Chest 2007; 132: 1151–1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moore V, Jaakkola M, Burge S. A systematic review of serial peak expiratory flow measurements in the diagnosis of occupational asthma. Eur Respir J 2011; 38: Suppl. 55, P4941. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jansen J, McCaffery KJ, Hayen A, et al. Impact of graphic format on perception of change in biological data: implications for health monitoring in conditions such as asthma. Prim Care Respir J 2012; 21: 94–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chung KF, Wenzel SE, Brozek JL, et al. International ERS/ATS guidelines on definition, evaluation and treatment of severe asthma. Eur Respir J 2014; 43: 343–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bel EH, Sousa A, Fleming L, et al. Diagnosis and definition of severe refractory asthma: an international consensus statement from the Innovative Medicine Initiative (IMI). Thorax 2011; 66: 910–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Melani AS, Bonavia M, Cilenti V, et al. Inhaler mishandling remains common in real life and is associated with reduced disease control. Respir Med 2011; 105: 930–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boulet LP, Vervloet D, Magar Y, et al. Adherence: the goal to control asthma. Clin Chest Med 2012; 33: 405–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Armour CL, Reddel HK, LeMay KS, et al. Feasibility and effectiveness of an evidence-based asthma service in Australian community pharmacies: a pragmatic cluster randomized trial. J Asthma 2013; 50: 302–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schatz M, Sorkness CA, Li JT, et al. Asthma Control Test: reliability, validity, and responsiveness in patients not previously followed by asthma specialists. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2006; 117: 549–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Juniper EF, O'Byrne PM, Guyatt GH, et al. Development and validation of a questionnaire to measure asthma control. Eur Respir J 1999; 14: 902–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vignola AM, Chanez P, Campbell AM, et al. Airway inflammation in mild intermittent and in persistent asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998; 157: 403–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Suissa S, Ernst P, Benayoun S, et al. Low-dose inhaled corticosteroids and the prevention of death from asthma. N Engl J Med 2000; 343: 332–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suissa S, Ernst P, Kezouh A. Regular use of inhaled corticosteroids and the long term prevention of hospitalisation for asthma. Thorax 2002; 57: 880–884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pauwels RA, Pedersen S, Busse WW, et al. Early intervention with budesonide in mild persistent asthma: a randomised, double-blind trial. Lancet 2003; 361: 1071–1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boulet LP, Turcotte H, Prince P, et al. Benefits of low-dose inhaled fluticasone on airway response and inflammation in mild asthma. Respir Med 2009; 103: 1554–1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reddel HK, Belousova EG, Marks GB, et al. Does continuous use of inhaled corticosteroids improve outcomes in mild asthma? A double-blind randomised controlled trial. Prim Care Respir J 2008; 17: 39–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fink JB, Rubin BK. Problems with inhaler use: a call for improved clinician and patient education. Respir Care 2005; 50: 1360–1374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Basheti IA, Reddel HK, Armour CL, et al. Improved asthma outcomes with a simple inhaler technique intervention by community pharmacists. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007; 119: 1537–1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wilson SR, Strub P, Buist AS, et al. Shared treatment decision making improves adherence and outcomes in poorly controlled asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010; 181: 566–577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rosas-Salazar C, Apter AJ, Canino G, et al. Health literacy and asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2012; 129: 935–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Plaza V, Sanchis J. Medical personnel and patient skill in the use of metered dose inhalers: a multicentric study. CESEA Group. Respiration 1998; 65: 195–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Basheti IA, Qunaibi E, Bosnic-Anticevich SZ, et al. User error with Diskus and Turbuhaler by asthma patients and pharmacists in Jordan and Australia. Respir Care 2011; 56: 1916–1923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Borrelli B, Riekert KA, Weinstein A, et al. Brief motivational interviewing as a clinical strategy to promote asthma medication adherence. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007; 120: 1023–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Foster JM, Smith L, Bosnic-Anticevich SZ, et al. Identifying patient-specific beliefs and behaviours for conversations about adherence in asthma. Intern Med J 2012; 42: e136–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Blaiss MS, Nathan RA, Stoloff SW, et al. Patient and physician asthma deterioration terminology: results from the 2009 Asthma Insight and Management survey. Allergy Asthma Proc 2012; 33: 47–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Royal College of Physicians. Why Asthma Still Kills. The National Review of Asthma Deaths (NRAD). Confidential Enquiry Report. RCP, London, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 56.FitzGerald JM, Becker A, Sears MR, et al. Doubling the dose of budesonide versus maintenance treatment in asthma exacerbations. Thorax 2004; 59: 550–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Harrison TW, Oborne J, Newton S, et al. Doubling the dose of inhaled corticosteroid to prevent asthma exacerbations: randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2004; 363: 271–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rice-McDonald G, Bowler S, Staines G, et al. Doubling daily inhaled corticosteroid dose is ineffective in mild to moderately severe attacks of asthma in adults. Intern Med J 2005; 35: 693–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Quon BS, Fitzgerald JM, Lemiere C, et al. Increased versus stable doses of inhaled corticosteroids for exacerbations of chronic asthma in adults and children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010; 10: CD007524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jayaram L, Pizzichini MM, Cook RJ, et al. Determining asthma treatment by monitoring sputum cell counts: effect on exacerbations. Eur Respir J 2006; 27: 483–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Message SD, Laza-Stanca V, Mallia P, et al. Rhinovirus-induced lower respiratory illness is increased in asthma and related to virus load and Th1/2 cytokine and IL-10 production. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2008; 105: 13562–13567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gibson PG, Powell H, Coughlan J, et al. Self-management education and regular practitioner review for adults with asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003; CD001117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gibson PG. Asthma action plans: use it or lose it. Prim Care Respir J 2004; 13: 17–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Oborne J, Mortimer K, Hubbard RB, et al. Quadrupling the dose of inhaled corticosteroid to prevent asthma exacerbations: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group clinical trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009; 180: 598–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Canonica GW, Castellani P, Cazzola M, et al. Adjustable maintenance dosing with budesonide/formoterol in a single inhaler provides effective asthma symptom control at a lower dose than fixed maintenance dosing. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 2004; 17: 239–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cates CJ, Karner C. Combination formoterol and budesonide as maintenance and reliever therapy versus current best practice (including inhaled steroid maintenance), for chronic asthma in adults and children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 4: CD007313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Patel M, Pilcher J, Pritchard A, et al. Efficacy and safety of maintenance and reliever combination budesonide–formoterol inhaler in patients with asthma at risk of severe exacerbations: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med 2013; 1: 32–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]