Abstract

Coccidiosis is caused by the protozoan parasite belongs to the genous Eimeria spp. which parasitizes the epithelium lining of the alimentary tract. Infection damages the lining of the gut causing diarrhoea and possibly dysentery. Coccidiosis is primarily a disease of young animals but can affect older animals that are in poor condition. In a farm, seven adult cattle had foul smell bloody diarrhoea, anorexia, emaciation condition, smudging of the perineum and tail with blood stained dung. Laboratory examinations of the dung samples revealed the presence of coccidian oocysts. Animals were treated with 33.33 % (w/v) sulphadimidine, along with supportive and fluid therapy. After completion of 1 week of therapy all the affected cattle were recovered from the diarrhoea.

Keywords: Coccidiosis, Adult cattle, Treatment

Introduction

Bovine coccidiosis is one of the major constraints to livestock productivity. It is responsible for considerable morbidity and mortality in bovine population, particularly in calves aged upto 1 year. Nearly all cattle are infected with coccidia, but only a limited number of cattle suffers from clinical coccidiosis. The disease occurs mainly in young animals where as the immune status plays a role in the protection of older animals. Infection occasionally occurs in calves over 6 months of age or even in adult cattle. Many cattle are sub clinically infected, resulting in considerable economic losses (Joyner et al. 1966). It occurs commonly in overcrowded conditions, but also occurs in free-ranging conditions that have congregating areas, such as feed grounds and watering areas. Coccidiosis is uncommon in adult cattle but occasional cases and sometimes, epidemics of disease have been reported in dairy cows (Fox et al. 1991). Coccidiosis is transmitted from animal to animal by the faeco-oral route. Infected faecal material contaminating feed, water, or soil serves as carrier of the oocysts; therefore, the susceptible animal contracts the disease by eating and drinking, or by licking itself. The severity of clinical disease depends on the number of oocysts ingested. The more oocysts ingested, the more severe the disease. The prevalence of coccidiosis in cattle and buffaloes has been well reported from different parts of India (Nambiar and Devada 2002; Singh and Agarwal 2003), but the information regarding the reports of coccidiosis in adult cattle seems to be very little. Present communication is report on the occurrence of coccidiosis in adult cattle and its treatment.

Case history and observations

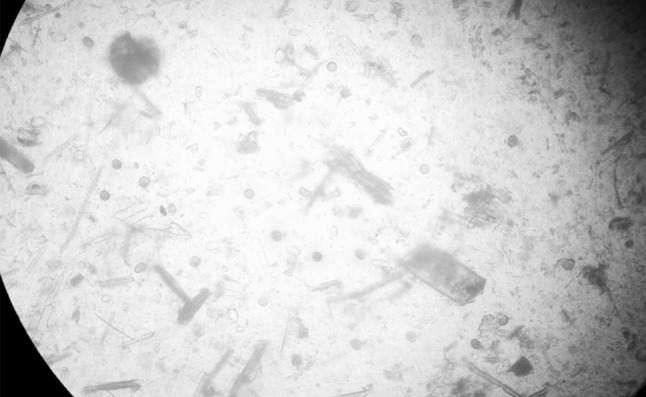

Seven Ongole cross breed cattle aged between five to six years had history of bloody diarrhoea with foul odour, anorexia and weakness for last 2 days in a shed containing of 78 cattle in a farm. In these, four cattle were recently introduced into the farm, after a long journey by lorry. The clinical examination of the sick animals revealed high temperature (103–105.2°F), increased heart rate (82–94/min), weak pulse, normal respiratory rate (16–22/min), suncken eye balls, dehydration, normal rumen motility and diminished milk yield. All the cattle had emaciation condition, smudging of the perineum and tail with blood stained dung, congested congenctival mucus membranes with normal lymph nodes. In two cattle during passage of dung, blood clotsin the dung, straining and tenesmus was also noticed. Dung samples (5–10 gm) were collected from all the adult affected cattle according to the techniques described by Mundt et al. (2005). All the samples were processed qualitatively by direct smear method, floatation technique for the presence of parasitic ova as demonstrated by Zajac and Conboy (2006). Laboratory examination of the dung samples were positive for coccidian oocysts (Figs. 1, 2). To know about the severity of infection each dung sample was examined by the modified McMaster technique to obtain the number of oocysts per gram of faeces (OPG). Samples were positive for coccidian oocysts, the maximum oocysts OPG count observed was 32,000 and the minimum count as 18,000.

Fig. 1.

Eimeria spp. in dung sample (10X)

Fig. 2.

Eimeria spp. in dung sample (40X)

Treatment and discussion

Based on the history, clinical signs, clinical examination of the cattle and microscopic examination of dung samples, confirmed that cattle were suffering with clinical coccidiosis. Clinical Coccidiosis was commonly prevalent in animals under 1 year age old and susceptibility to infection sharply declined with advancement of age because of previous exposure and development of immunity to the disease (Nambiar and Devada 2002). A negative correlation exists between age of cattle and risk of infection. Younger animals depicted higher prevalence (27.23 %) of coccidial infection than older animals (15.65 %) as reported by Cicek et al. (2007). Higher oocysts counts have been observed in immature as compared to adults (Waruiru et al. 2000). Gasmir et al. (2006) noticed profuse foul smelling watery diarrhoea, dehydration, marked anemia in gastrointestinal infection with Eimeria bovis. Dung samples were positive for coccidian oocysts, the maximum oocyst OPG count observed was 32,000 and the minimum count as 18,000. Similar findings were reported by Boughton (1945) who conducted studies in order to record the spread of coccidiosis from carrier to clinical cases in cattle. Dedrickson (2002) reported clinical coccidiosis is a parasitic disease associated with bloody diarrhoea, poor growth and sometimes death. Infected animals were isolated from the other animals to avoid exposure to other cattle and treatment was started to the affected animals. All the affected cattle were treated with 33.33 % (w/v) sulphadimidine @ 100 mg/kg body weight IV for 7 days, inj zeet @ 0.5 mg/kg (chlorpheniramine maleate) IM for 7 days, Ecotas boli (Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Lactobacillus sporogenes, Aspergillus oryzae, Biotin, DL-methionine, copper sulphate, zinc sulphate, cobalt sulphate) two BID PO for 2 weeks, inj. Stryptochrome (adenochrome mono semicarbazone) 8 ml IM for first 2 days of therapy, parentral haematinics inj. feritas (Iron sorbitol citric acid complex, folic acid, hydroxocobalamin acetate) @ 7 ml to each animal at alternate days was given. To counteract the electrolyte loss, fluids were given (DNS @5 ml/kg body weight and Ringers lactate @ 5 ml/kg body weight) for first 3 days of therapy. Mancebo et al. (2002) reported Sulfadimidine (sulfamezathine) has better therapeutic efficacy against E. bovis. By the third day of therapy condition was improved with reduction in frequency of diarrhoea. Following treatment, in five animals’ condition was improved significantly, absence of bloody diarrhoea, increasing milk yield and general activity. After completion of therapy again dung samples were examined, which did not reveal any parasitic oocysts. But in two animals partial recovery was noticed by absence of diarrhoea, but the animal had anorexia and dullness. In these two cases metronidazole @ 10 mg/kg body weight IV BID for 3 days was given to counteract the secondary anaerobic bacterial infection. Improvement was noticed in the two animals after the above therapy.

Conclusion

Present communication reports the Coccidiosis in adult cattle and its therapeutic management.

References

- Boughton DC. Bovine coccidiosis from carrier to clinical cases. N Am Vet. 1945;26:147–153. [Google Scholar]

- Cicek H, Sevimli F, Kozan E, Kose M, Eser M, Dogan N. Prevalence of coccidia in beef cattle in western Turkey. Parasitol Res. 2007;101:1239–1243. doi: 10.1007/s00436-007-0627-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dedrickson BJ (2002) Coccidiosis in beef calves. Feed Lot Magazine Online 10(1)

- Fox MT, Higgins RJ, Brown ME, Norten CC. A case of Eimeria gilruthi infection in sheep in Northern England. Vet. Rec. 1991;129:141–142. doi: 10.1136/vr.129.7.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasmir GS, Osman AY, El-Amin, Zakia EA. Pathological changes in bovine coccidiosis in experimentally infected zebu calves. Sudan J Vet Res. 2006;15:256–257. [Google Scholar]

- Joyner LP, Norton CC, Davis SF, Watkins CV. The species of coccidia occurring in cattle and sheep in south-west of England. Parasitology. 1966;56:531–541. doi: 10.1017/S0031182000069018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancebo OA, Acevedo CM, Rossiter A, Suartz MD, Guardia N, Russo AM, Monzon CM, Bulman GM. Coccidiosis in goat kids in province of Formosa, Argentina. Vet Argentina. 2002;19:342–348. [Google Scholar]

- Mundt HC, Bangoura B, Rinke M, Rosenbrouch M, Daugschies A. Pathology and treatment of Eimeria Zuernii coccidiosis in claves: investigation in an infection model. Parasitol Int. 2005;54(4):223–230. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nambiar KS, Devada K. Prevalence of bovine coccidiosis in Trissur. Indian Vet Med J. 2002;26:211–214. [Google Scholar]

- Singh R, Agarwal RD. Incidence of coccidian infection in buffaloes in Mathura. J Vet Parasitol. 2003;17:169–170. [Google Scholar]

- Waruiru RM, Kyvsgaard NC, Thamsborg SM, Nansen P, Bogh HO, Munyua WK, Gathuma JM. The prevalence and intensity of helminth and coccidial infections in dairy cattle in central Kenya. Vet Res Commun. 2000;24:39–53. doi: 10.1023/A:1006325405239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zajac MA, Conboy GA (2006) Faecal examination for the diagnosis of Parasitism. 7th edn. Blackwell Publishing, Ames, pp 3–10