Abstract

We compared the cost burdens of potentially preventable hospitalizations for cardiovascular disease and diabetes for Asian Americans, Pacific Islanders, and Whites using Hawai’i statewide 2007–2012 inpatient data. The cost burden of the 27,894 preventable hospitalizations over six years (total cost: over $353 million) fell heavily on Native Hawaiians who had the largest proportion (23%) of all preventable hospitalizations and the highest unadjusted average costs (median: $9,117) for these hospitalizations. Diabetes-related amputations (median cost: $20,167) were the most expensive of the seven preventable hospitalization types. After adjusting for other factors (including age, insurance, and hospital), costs for preventable diabetes-related amputations were significantly higher for Native Hawaiians (ratio estimate:1.23; 95%CI:1.05–1.44), Japanese (ratio estimate:1.44; 95%CI:1.20–1.72), and other Pacific Islanders (ratio estimate:1.26; 95%CI:1.04–1.52) compared with Whites. Reducing potentially preventable hospitalizations would not only improve health equity, but could also relieve a large and disproportionate cost burden on some Pacific Islander and Asian American communities.

Keywords: Hospitalization, costs, diabetes, heart disease, Asians, Pacific Islanders, Native Hawaiians

Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders include some of the fastest growing racial/ethnic groups in the United States (U.S.).1,2 Many Asian American and Pacific Islander groups have notably high burdens of cardiovascular disease and diabetes,3 conditions that necessitate ongoing chronic care management to avoid the expensive and debilitating complications that can result from these diseases.4 Yet many within these groups also have social and economic vulnerabilities, comorbid health conditions, and poor access to high-quality health care.5 This presents challenges to chronic care management and can result in high disease severity and adverse events.3,6

Potentially preventable hospitalizations are defined by the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality (AHRQ) as hospital admissions that are likely preventable through effective chronic care management and access to high-quality, primary care.7 Potentially preventable hospitalizations for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and diabetes (DM) include the most common preventable hospitalizations and incur substantial costs.8 Reducing potentially preventable hospitalizations is a major policy goal as this has the potential to improve health care quality while also reducing health care costs.9–10 Additionally, because Medicare has stopped paying for some potentially preventable hospitalizations and other health care payers have followed, much more of the burden of preventable hospitalizations is now falling on hospitals in terms of uncompensated care, making this a topic of considerable interest in health care administration.11

Significant disparities have been seen in potentially preventable hospitalizations among Asian American and Pacific Islander groups in previous studies.6,12–14 Specifically, Native Hawaiians, Filipinos, and Japanese have higher preventable hospitalizations rates for diabetes and cardiovascular disease than Whites.6,12–13 Resolving potentially preventable hospitalization disparities is an important health equity goal.6,12–14

Cost information is critical to policy and administrative considerations, yet little is known about the cost burdens of potentially preventable hospitalizations among Asian American and Pacific Islander populations. Nationally, the total annual cost of potentially preventable hospitalizations for DM and CVD is over $15 billion and the cost of potentially preventable hospitalizations for congestive heart failure alone is over $8 billion.8 As national analyses typically combine Pacific Islanders with Asian Americans, inequalities across heterogeneous subgroups with distinct socioeconomic and health profiles are obscured.15–16 This aggregation makes it challenging to understand fully the cost burdens on vulnerable communities. This issue is particularly relevant to groups, such as Native Hawaiian, with known disparities not only in potentially preventable hospitalizations, but also in socioeconomic status and other health determinants.3

The objectives of this study were (1) to examine whether the average cost per hospitalization differed by race/ethnicity after adjustment for other factors and (2) to estimate the total cost burden of preventable hospitalizations for each racial/ethnic group. Hawai’i is an excellent location to perform this work as the state is home to 29% of the total U.S. Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander population,17 and over 40% of the population in Hawai’i identifies as Asian.18

Methods

Hawaii Health Information Corporation data

Hawaii Health Information Corporation (HHIC) inpatient data from 2007–2012 were analyzed, which includes data from the 25 acute care public and private hospitals in the state operating during the study period. Data from HHIC includes detailed information on discharges from all hospitalizations by all payers, including patient race/ethnicity, insurer, age, gender, and International Classification of Diseases – 9th revision – Clinical Modification (ICD-9) primary diagnosis, secondary diagnosis, and procedure codes.19

Sample

All non-pregnancy-related hospitalizations by any individual aged 18 years or older from December 2007–2012 were considered (N=523,370). Hospitalizations at Tripler (the Department of Defense hospital) (n=36,200) were excluded as these they did not consistently report racial/ethnic data during the study period. Hospitalizations were also excluded if they otherwise did not report race/ethnicity data (n=8,561). Non-Hawai’i residents (n=20,052) were excluded. Finally, transfers or unknown admission source (n=21,408) were excluded to meet AHRQ potentially preventable hospitalizations guidelines.7 After exclusions, the total number of eligible hospitalizations was 437,149 (83.5% of total hospitalizations).

The HHIC data include a master patient identification variable, used to track individuals across all hospitals in the state. Considering unique individuals confirms that multiple admissions by members of certain racial/ethnic groups are not driving health disparities, a particularly important issue in diabetes and cardiovascular disease, where racial disparities are seen in readmissions.20,21

For cumulative costs overall and across race/ethnicity, all admissions by individuals were included to identify the full cost burden by racial/ethnic groups. The multivariable analyses of cost differences by race/ethnicity were done once per individual so that the characteristics of individuals with multiple admissions were only considered once and those with readmissions would not disproportionately impact analyses. For individuals with multiple admissions, the first admission was used for these analyses.

Potentially preventable hospitalizations

To measure preventable hospitalizations for cardiovascular disease and diabetes, we followed AHRQ definitions.7 For cardiovascular disease-related preventable hospitalizations, we included three types: (1) congestive heart failure, (2) angina, and (3) hypertension. For diabetes-related preventable hospitalizations, we included four types: (1) uncontrolled diabetes without mention of a short-term or long-term complication; (2) diabetes with short-term complications (e.g., ketoacidosis, hyperosmolarity, or coma); (3) diabetes with long-term complications (e.g., renal, eye, neurological, circulatory, or complications not otherwise specified); and (4) lower-extremity diabetes-related amputations. More detail about data specifications can be found at: http://www.qualityindicators.ahrq.gov/Modules/pqi_resources.aspx. Because the definition of lower-extremity diabetes-related amputations preventable hospitalizations can overlap with that of short or long-term diabetes-related preventable hospitalizations, all preventable hospitalizations that met criteria for lower-extremity diabetes-related amputations preventable hospitalizations and another hospitalization type (either short or long-term diabetes-related preventable hospitalizations) were placed into lower-extremity diabetes-related amputations to eliminate double-counting.

Costs

Costs were estimated by multiplying the total charges for each hospitalization supplied in the hospital discharge data by cost/charge ratio (CCR) using established guidelines.22 These allow for the conversion of charge data to cost estimates, including an adjustment factor (AF) for differences in case mix and severity of illness. The formula is: Hospital Charges*CCR*AF= Estimated Cost. All costs were adjusted to constant 2012 dollars using the Medical component of the Consumer Price Index.23

Race/ethnicity

The HHIC race/ethnicity variable was created from race/ethnicity categories available consistently across all hospitals in Hawai’i from 2007–2012.19 Race/ethnicity data are provided by patient self-report at intake and include only one primary race. Mixed-race individuals are represented by self-report of their primary race of identification. In 2006 (prior to the study period), HHIC performed community-wide training to ensure that the racial/ethnic data were uniformly collected with detail for Asian and Pacific Islander subgroups across all Hawai’i hospitals. Classification options for Pacific Islanders include Native Hawaiian, Fijian, Guamanian, Marshallese, Melanesian, Other Micronesian, Samoan, Tahitian, Tokelauan, and Tongan. Classification options for Asians include Chinese, Japanese, Filipino, Korean, Vietnamese, and Thai. The Hawaii Health Information Corporation also performs extensive ongoing quality assurance to confirm that racial/ethnic data are comparable across hospitals, including clear data specifications, monthly reports to identify discrepancies, and regular HHIC-provider stakeholder meetings.

The racial/ethnic groups considered in this analysis were Native Hawaiian, White, Japanese, Filipino, other race (e.g., Black, Hispanic, Mixed race as primary identity), Samoan, other Pacific Islander (e.g., Tongan, Micronesian), Chinese, and other Asian (e.g., Korean). These were the racial/ethnic groups with sufficiently large numbers for statistically reliable analyses.

Control variables

In multivariable models, we included factors that have been shown to affect preventable hospitalizations.6,12–14 These included gender (male/female), age group (younger than 50, 50–64, 65–79, and 80 years or older), co-morbidity, defined by the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI),24 and payer (Medicare, Medicaid, Private, and other). These also included location of residence (live on Oahu vs. other Hawaiian islands) based on evidence that access to care is often worse on the other islands, compared with the more urban Oahu, hospital, as costs vary by hospital,25 and substance abuse derived from ICD-9 codes26 based on evidence that this would likely be a significant factor in predicting preventable hospitalizations and potentially affecting costs.27

Statistical analysis

To describe the total cost burden by race/ethnicity, we summed the total costs of all preventable hospitalizations for each race/ethnicity for the six-year period. We also determined the average cost of preventable hospitalizations overall and by preventable hospitalization types for individuals by race/ethnicity.

Costs by hospitalization were compared by racial/ethnic group using Kruskal-Wallis tests due to the highly skewed distribution of cost data. Average costs by race/ethnicity adjusting for other factors were then predicted in a multivariable model using the gamma regression with log link.28 Multivariable models included control variables listed above, type of preventable hospitalizations, and interactions between racial/ethnic groups and type of preventable hospitalizations as well as racial/ethnic group by age group. (Interactions by gender and racial/ethnic groups were also considered, but were not included in the final model due to lack of statistical significance.) These models were used to calculate cost ratio estimates (RE) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for each racial/ethnic group compared with Whites after adjustment for other factors.

All data analyses were performed in SAS 9.3 (Cary, N.C., 2011). A two-tailed p-value of less than .05 was regarded as statistically significant. The study was deemed exempt by the University of Hawai’i Institutional Review Committee under Department of Health and Human Services criteria 4.

Results

The total number of preventable hospitalizations for cardiovascular disease and diabetes in Hawai’i over the six year period was 27,894 by 16,941 individuals for a total cost of $353,193,828. Descriptive information about potentially preventable hospitalizations are seen in Table 1. The largest proportion of total preventable hospitalizations came from Native Hawaiians (23.4%) followed by Whites (21.8%), Japanese (18.9%), Filipino (14.0%), other race (8.2%), other Pacific Islander (4.1%), Chinese (4.6%), Samoan (2.3%), and other Asian (2.6%).

Table 1.

DESCRIPTIVE INFORMATION FOR THOSE WITH A PREVENTABLE HOSPITALIZATION (PH) FOR CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE (CVD) OR DIABETES (DM) FROM HAWAI I HEALTH INFORMATION CORPORATION DATA, 2007–2012.

| Total PH | |

|---|---|

| N | 27,894 |

| N (%) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| Chinese | 1274 (4.6%) |

| Filipino | 3894 (14.0%) |

| Hawaiian | 6532 (23.4%) |

| Japanese | 5265 (18.9%) |

| Other Asian | 732 (2.6%) |

| Other Pacific Islander | 1154 (4.1%) |

| Other race | 2296 (8.2%) |

| Samoan | 654 (2.3%) |

| White | 6093 (21.8%) |

| PH Type | |

| Uncontrolled diabetes | 319 (1.1%) |

| Short-term complications | 2324 (8.3%) |

| Long-term complications | 4053 (14.5%) |

| Lower-extremity amputations | 956 (3.4%) |

| Hypertension | 1364 (4.9%) |

| Angina w/o procedure | 1156 (4.1%) |

| Congestive heart failure | 17722 (63.5%) |

| Insurance | |

| Dept of Defense | 374 (1.3%) |

| Medicare | 16837 (60.4%) |

| Medicaid | 5018 (18.0%) |

| Private | 4918 (17.6%) |

| Other | 747 (2.7%) |

| Age group | |

| <50 | 5520 (19.8%) |

| 50–64 | 6942 (24.9%) |

| 65–79 | 7073 (25.4%) |

| 80+ | 8359 (30.0%) |

| Island | |

| Oahu | 19968 (71.6%) |

| Maui | 2540 (9.1%) |

| Hawaii | 3979 (14.3%) |

| Kauai | 1301 (4.7%) |

| Other | 106 (0.4%) |

| Other variables | |

| Female | 12533 (44.9%) |

| Substance abuse | 2448 (8.8%) |

| Mean (±SD) | |

| Average Charlson (CCI) | 5.02 (±2.79) |

| Average # PH per person | 1.65 (±1.79) |

The most common type of preventable hospitalization was congestive heart failure (CHF), accounting for 63.5% of total preventable hospitalizations. The vast majority of preventable hospitalizations were paid by public sources (79.7%), with Medicare carrying the largest percentage (60.4%). Almost 20% of preventable hospitalizations were by those who were under 50 years, 25% were by those 50–64, 25% were also by those 65–79, and 30% were by those who were 80+ years. Men had higher rates of preventable hospitalizations (55.1%) than women. About 9% of preventable hospitalizations also included a substance use diagnosis. The average number of preventable hospitalizations per person was 1.65 (SD: 1.79).

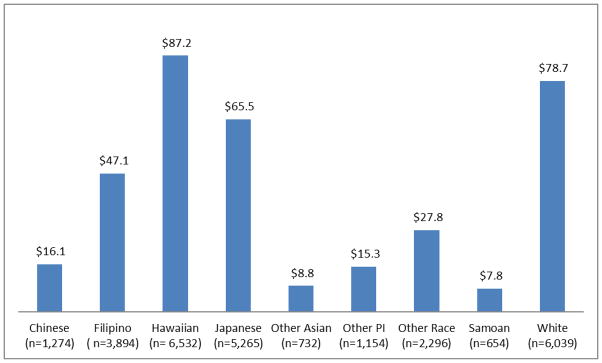

Figure 1 shows the total cost burden by race/ethnicity. As can be seen, the largest cost burden over the six years was seen in Native Hawaiians ($87.2 million), followed by Whites ($78.7 million) and Japanese ($65.4 million).

Figure 1.

Total unadjusted cost burden by race/ethnicity for potentially preventable hospitalizations in Hawai’i 2007–2012 (rounded to the nearest million).a

Note:

aCosts are in constant 2012 dollars.

Table 2 shows the descriptive data for preventable hospitalizations by race/ethnicity. The average number of hospitalizations per person varied significantly across race groups (p-value<.001). Samoans (mean: 2.22 visits/person) and Native Hawaiians (mean: 1.89 visits/person) had the highest number of multiple hospitalizations and Japanese (mean: 1.48 visits/person) had the lowest.

Table 2.

Descriptive data for all potentially preventable hospitalizations for CVD and diabetes by race/ethnicity in Hawai’i from Hawai’i Health Information Corporation Data, 2007–2012.a,b

| Chinese | Filipino | Native Hawaiian |

Japanese | Other Asian |

Other PI | Other Race |

Samoan | White | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total # of admissions | 1,274 | 3,894 | 6,532 | 5,265 | 732 | 1,154 | 2,296 | 654 | 6,093 | 27,894 |

| Total # of individuals | 837 | 2,411 | 3,435 | 3,567 | 470 | 713 | 1,329 | 295 | 3,884 | 16,941 |

| Average # of admissions per person | 1.52 | 1.63 | 1.89 | 1.48 | 1.51 | 1.62 | 1.74 | 2.22 | 1.56 | 1.65 |

| Median Costs | $8,834 | $8,389 | $9,117 | $8,670 | $8,638 | $8,821 | $8,372 | $9,155 | $9,042 | $8,798 |

| Mean (SD) Costs | $12,893 (±$16,026) | $11,667 (±$14,422) | $13,593 (±$25,180) | $12,341 (±$14,088) | $12,070 (±$11,080) | $13,385 (±$15,568) | $11,929 (±$12,621) | $12,623 (±$11,960) | $12,895 (±$15,586) | $12,662 (±$17,241) |

| Cost Range | $987–$269,081 | $1,263–$252,446 | $832–$1,073,377 | $667–$213,489 | $1,238–$76,337 | $1,333–$134,510 | $901–$192,071 | $2,261–$90,120 | $921–$290,490 | $667–$1,073,377 |

Average costs (medians and means) are by individuals (using data from first admission).

Costs are in constant 2012 dollars.

Average preventable hospitalization costs varied significantly by race/ethnicity (p<0.001). The groups with the highest average preventable hospitalization costs were Samoans (median: $9,155; mean: $12,623) and Native Hawaiians (median: $9,117; mean: $13,593). Other Race (median: $8,372; mean: $11,929) and Filipino (median: $8,389; mean: $11,667) had the lowest average preventable hospitalization costs. However, a wide range of preventable hospitalization costs were seen within each racial/ethnic group. In most groups, the ranges varied from under $1,000 to several hundred thousand dollars for each hospitalization. Visits from Native Hawaiians had the widest hospitalization cost range, going from slightly over $800 to over a million dollars.

Table 3 shows the cost differences by preventable hospitalization type overall and by racial/ethnic groups. Diabetes-relatable amputations (median cost: $20,167) had the most expensive average cost of the seven included preventable hospitalization types, a cost two times higher than any of the other tested types of preventable hospitalizations.

Table 3.

MEDIAN COSTS BY TYPE OF PREVENTABLE HOSPITALIZATION BY RACE/ETHNICITY BY RACE/ETHNICITY IN HAWAI I, 2007–2012a,b

| Chinese | Filipino | Native Hawaiian | Japanese | Other Asian | Other PI | Other Race | Samoan | White | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes | ||||||||||

| Uncontrolled diabetes | c | $5,324 | $4,986 | $6,713 | $4,541 | $5,520 | $4,732 | c | $6,642 | $5,764 |

| Short-term complications | $9,033 | $7,776 | $7,507 | $8,265 | $7,952 | $6,699 | $6,661 | $4,957 | $7,840 | $7,700 |

| Long-term complications | $7,467 | $6,910 | $8,818 | $7,034 | $7,540 | $8,868 | $7,752 | $7,229 | $8,509 | $7,874 |

| Lower-extremity amputations | $29,535 | $17,941 | $18,968 | $25,900 | $18,993 | $20,996 | $22,385 | $18,326 | $18,763 | $20,167 |

| Heart Conditions | ||||||||||

| Hypertension | $6,989 | $6,613 | $7,922 | $7,376 | $6,532 | $6,719 | $6,641 | $7,694 | $6,984 | $7,036 |

| Angina w/o procedure | $5,736 | $6,725 | $6,932 | $5,958 | $6,834 | $8,569 | $6,415 | c | $5,980 | $6,358 |

| Congestive heart failure | $9,417 | $9,262 | $9,539 | $9,251 | $9,738 | $8,864 | $9,137 | $9,993 | $9,945 | $9,473 |

Notes:

Cost for short term complications (p=.003), long term complications (p<.001), and total diabetes (p<.001), and congestive heart failure (p=.01) vary significantly across race/ethnicity.

Costs are in constant 2012 dollars.

Sample too small to provide stable estimate.

Significant differences in average costs for preventable hospitalizations across racial/ethnic groups were seen for short-term complications, long-term complications, and angina. Interestingly, though overall Native Hawaiians had the highest average preventable hospitalization costs, different racial/ethnic groups had the highest average costs for specific types of preventable hospitalizations. For instance, Chinese (median: $9,033) had the highest unadjusted median costs for short-term complications, while other Pacific Islanders had the highest unadjusted median costs for long-term DM complications (median: $8,868) and angina (median: $8,569). Diabetes-relatable amputation costs did not differ significantly by race/ethnicity in unadjusted analyses.

Table 4 shows the results of the multivariable model predicting costs. For several types of preventable hospitalizations, costs were significantly higher for Asian American and Pacific Islander subgroups compared with Whites. Of particular note, costs for preventable diabetes-related amputation hospitalizations were significantly higher for Native Hawaiians (ratio estimate (RE): 1.23; 95% CI: 1.05–1.44), Japanese (RE: 1.44; 95% CI: 1.20–1.72), and other Pacific Islanders (RE: 1.30; 95% CI: 1.05–1.61) compared with Whites (Table 4). Moreover, for angina preventable hospitalizations, Native Hawaiians (RE: 1.14; 95% CI: 1.01–1.28) and Filipinos (RE: 1.16; 95% CI: 1.02–1.32) also showed significantly higher costs than Whites.

Table 4.

ADJUSTED RATIO ESTIMATE FOR THE COST OF A HOSPITALIZATION BY RACE/ETHNICITY COMPARED WITH WHITES FOR EACH PREVENTABLE HOSPITALIZATION TYPEa

| Chinese | Filipino | Hawaiian | Japanese | Other Asian | Other PI | Other | Samoan | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ratio Estimate [95% CI] |

Ratio Estimate [95% CI] |

Ratio Estimate [95% CI] |

Ratio Estimate [95% CI] |

Ratio Estimate [95% CI] |

Ratio Estimate [95% CI] |

Ratio Estimate [95% CI] |

Ratio Estimate [95% CI] |

|

| Diabetes | ||||||||

| Uncontrolled diabetes | 0.93 [0.55, 1.55] | 0.84 [0.62, 1.13] | 0.94 [0.72, 1.23] | 1.16 [0.88, 1.53] | 0.83 [0.53, 1.29] | 0.68 [0.46, 1.01] | 0.71 [0.53, 0.95]* | 0.96 [0.43, 2.14] |

| Short-term complications | 1.02 [0.81, 1.29] | 1.06 [0.92, 1.21] | 0.97 [0.86, 1.10] | 1.06 [0.93, 1.21] | 0.97 [0.78, 1.22] | 0.76 [0.63, 0.92]** | 0.87 [0.75, 1.00] | 0.53 [0.37, 0.75]*** |

| Long-term complications | 0.93 [0.82, 1.07] | 0.87 [0.78, 0.96]** | 1.09 [0.99, 1.18] | 0.88 [0.81, 0.96]** | 1.02 [0.86, 1.20] | 0.98 [0.86, 1.12] | 1.03 [0.92, 1.15] | 1.03 [0.82, 1.28] |

| Lower-extremity amputations | 0.98 [0.66, 1.46] | 1.11 [0.90, 1.38] | 1.23 [1.05, 1.44]* | 1.43 [1.19, 1.72]*** | 1.03 [0.75, 1.40] | 1.30 [1.05, 1.61]* | 1.24 [0.99, 1.56] | 1.16 [0.84, 1.61] |

| Heart Conditions | ||||||||

| Hypertension | 1.03 [0.83, 1.28] | 0.99 [0.87, 1.13] | 1.07 [0.94, 1.22] | 0.98 [0.86, 1.11] | 0.98 [0.75, 1.26] | 0.88 [0.71, 1.09] | 0.90 [0.76, 1.06] | 1.13 [0.85, 1.50] |

| Angina w/o procedure | 1.02 [0.79, 1.34] | 1.16 [1.02, 1.32]* | 1.14 [1.01, 1.29]* | 1.05 [0.92, 1.19] | 1.15 [0.83, 1.59] | 1.16 [0.89, 1.53] | 1.17 [0.99, 1.38] | 1.00 [0.61, 1.62] |

| Congestive heart failure | 0.99 [0.91, 1.08] | 0.94 [0.90, 0.99]* | 0.98 [0.94, 1.02] | 0.92 [0.88, 0.97]** | 0.82 [0.75, 0.90]*** | 0.77 [0.70, 0.84]*** | 0.92 [0.87, 0.98]** | 1.01 [0.90, 1.14] |

Notes:

p= <.05

p= <.01

p= <.001

Model controlling for insurance, age group, gender, preventable hospitalization (PH) type, comorbidity, substance use, hospital, island, and interactions for race/ethnicity with age group and with PH type.

In contrast, for CHF preventable hospitalizations, costs for Filipinos (RE: 0.92; 95% CI: 0.88–0.97), Japanese (RE: 0.92; 95% CI: 0.87–0.96), other Asians (RE: 0.82; 95% CI: 0.75–0.90), and other Pacific Islanders (RE: 0.77; 95% CI: 0.70–0.84) were significantly lower than those for Whites. Similarly, costs for DM short-term preventable hospitalizations were significantly lower for other Pacific Islanders (RE: 0.76; 95% CI: 0.63–0.92) and Samoans (RE: 0.53; 95% CI: 0.37–0.75) and costs for DM long-term preventable hospitalizations were significantly lower for Filipinos (RE: 0.87; 95% CI: 0.78–0.96) and Japanese (RE: 0.88; 95% CI: 0.81–0.96) compared with Whites. No significant differences were seen for costs for hypertension preventable hospitalizations by race/ethnicity in adjusted models.

The appendix provides the ratio estimates for other variables in the full model. Preventable hospitalization types varied significantly in costs after adjustment. Of particular note, lower extremity amputations were significantly higher than CHF in adjusted models. Women had significantly more expensive preventable hospitalizations as did those with higher comorbidity and those with a substance abuse diagnosis. All insurance groups were significantly more likely than private insurance to have higher costs. Other significant factors in the multivariable models were age group, island, and hospital.

Discussion

This study compared the cost burden of potentially preventable hospitalizations for cardiovascular disease and diabetes for Asian Americans, Pacific Islanders, and Whites using Hawai’i statewide 2007–2012 data. We found the largest cost burden was seen in Native Hawaiians who had the largest proportion (23%) of all preventable hospitalizations and the highest unadjusted median costs (median: $9,117).

This does not include indirect costs such as “lost productivity, lost wages, absenteeism, family leave, lower quality of life and premature death.”29 As a higher percentage of Native Hawaiians with preventable hospitalization are working age, these hospitalizations may have a greater impact on employment and related factors. This disparity indicates a substantial, multifaceted burden for the Native Hawaiian community, which already has a lower socioeconomic status than most other racial/ethnic groups in Hawai’i.3

Another group with a heavy burden is other Pacific Islanders, which includes Samoans, Tongans, and Micronesians. While the other Pacific Islander population, in total, was only responsible for 6.5% of total costs for preventable hospitalizations, other Pacific Islanders in Hawai’i have some of the poorest socioeconomic profiles in the state and often have poorer health status than other racial/ethnic groups, including Native Hawaiians. Though Hawai’i has high insurance coverage rates compared with most other states,30 other Pacific Islander groups may be more likely to be uninsured than many other racial/ethnic groups. Being uninsured can lead to higher costs for those patients for the same care.31 We considered Samoans specifically and found they had a higher average number of preventable hospitalizations per person compared with other studied groups. Considering this issue in more detail may be very useful; Samoans are a notably understudied racial/ethnic group in the U.S. and a better understanding of their health care challenges and burdens specifically is needed.

Preventable hospitalizations are driven by many factors, including poor access to health care or poorer quality of care. There are known disparities for Asian American and Pacific Islanders compared with Whites in access to care.3,5 Social vulnerabilities may help explain both higher costs for certain groups for the same type of hospitalization seen in this study as well as higher rates of these hospitalizations found in other work. 6,12–14 Reducing these hospitalizations is important. Community health clinics that focus on Native Hawaiian populations and other community health clinical who serve large proportions of Asian and Pacific Islander populations may be critical partners in efforts to reduce preventable hospitalizations, particularly by being trustworthy, culturally relevant, conveniently accessible sites for ongoing primary care. 3,5–6

The direct cost burdens of these hospitalizations, as well as the indirect impact on employment or family obligations for those hospitalizations, are challenges for any family, but may most directly affect families already struggling economically. The burdens of the same dollar amount are not equal across groups.31,32 Research has found that racial/ethnic minorities with low incomes “spend a greater proportion of their disposable income on health care.”31 Furthermore, the financial burden of medical care has been increasing for U.S. families in part due to “greater out-of-pocket costs for health insurance, as well as sluggish income gains.”33 As medical costs are a common reason for bankruptcy, this is an important policy issue. From a policy perspective, there is an additional concern that the Affordable Care Act will lead to higher copayments,34 which would mean additional burdens on already overburdened communities.

Interestingly, when examining preventable hospitalizations together, there were not significant differences in average cost of preventable hospitalizations by race and ethnicity. This was because differences in the average preventable hospitalization cost by race and ethnicity varied considerably by preventable hospitalization type. For instance, for CHF, Whites cost significantly more than some ethnic subgroups. However, significant disparities emerged for particular types of preventable hospitalization by race/ethnicity, particularly hospitalizations involving lower extremity amputations where Native Hawaiians, Japanese, and other Pacific Islanders cost more than Whites.

The costs of preventable hospitalizations are an important policy issue not only to address individual finances and family burdens, but also to address public and corporate spending. Almost 90% of the total preventable hospitalizations in this study were paid by the public system, which amounts to over 290 million dollars over six years, or approximately 50 million dollars annually, as costs incurred by just one state with a relatively small population. Furthermore, the multivariable analyses showed that costs for the public insurance system were higher than for private payers after adjusting for other factors. Additionally, many admissions were for readmissions. It is likely that if these admissions occurred today, Medicare or private payers would not pay for many of them due to new reimbursement rules. Thus, this would be uncompensated care for hospitals.

While there are many initiatives in place to address the high costs of preventable hospitalizations on the public system, many of these efforts are directed at hospitals to reduce their preventable readmission rates through penalties.11 Such efforts may not address the larger social and economic systems that lead to poorer access to and utilization of high quality chronic care management in the first place.35 Some have suggested that the focus and design of these efforts may thus actually increase racial/ethnic disparities.10,36 Yet there is a clear and urgent need to address preventable hospitalizations and readmissions, making it critical to have a strong understanding of current racial/ethnic disparities in order to consider future policy effects.

Racial/ethnic disparities impose a large cost on our health care system and society at large.29 Previous research has found that the indirect and direct medical costs faced by American minority groups from racial/ethnic disparities to be 1.2 trillion dollars over a three-year period.29 These costs fall not just on those individual and their families, but also on communities, health care organizations, employers, and the government.29 It may be necessary to include all these affected groups in order to find the most successful and sustainable solutions to reduce this cost and improve care.

In descriptive analyses, significantly higher costs by race/ethnicity overall and for some conditions were observed. In multivariable analyses, we adjusted for factors that might impact the severity of the condition on admission (e.g., comorbidity, insurance, age) and found no systematic difference overall for higher costs by race/ethnicity. However, from our interaction terms, we did see differences across certain types of preventable hospitalizations after controlling for other variables. Diabetes-relatable amputations (median cost: $20,167) were the most expensive of the seven included preventable hospitalization types. Costs for preventable diabetes-relatable amputation hospitalizations remained significantly higher for Native Hawaiians, Japanese, and other Pacific Islanders than for Whites in multivariable models.

Because these diabetes-related amputations were the most expensive of the seven preventable hospitalization types included in our analyses and showed variation by racial/ethnic groups, we ran a post hoc descriptive comparison to determine if a longer length of stay in non-White racial/ethnic groups was a likely factor in explaining the higher costs for diabetes-related amputation hospitalizations. We found that length of stay did not vary significantly by race/ethnicity for diabetes-related amputation hospitalizations (p=.25). Thus, our post hoc analyses indicated that these differences did not appear to be due to differences in length of stay across racial/ethnic groups.

Our findings should be useful to policymakers who must allocate increasingly limited resources.37 The focus of efforts may depend on whether the goal is reducing health disparities or reducing total costs or both. In terms of meeting both goals, we note the high potential cost savings of reducing preventable hospitalizations for Native Hawaiians. In terms of total cost reduction, we show that reductions in congestive heart failure, as the most common type of preventable hospitalization, would provide the most cost savings. Congestive heart failure is responsible for 64% of the total diabetes-related and cardiovascular preventable hospitalizations. A focus on CHF preventable hospitalizations might particularly benefit Whites, who have a very high cost burden and particularly high costs for CHF hospitalizations. Asian American and Native Hawaiian ethnic groups also have high burdens of congestive heart failure preventable hospitalizations,13 though we find that the costs of their hospitalizations are not higher (and are in fact significantly lower in some cases) than those of Whites. Addressing CHF hospitalization may provide the most overall savings. However, this focus would not specifically address health equity without further targeting of vulnerable groups.

The focus of interventions may vary by the racial/ethnic group of interest. Previous studies have found that solutions to decrease the underlying prevalence of diabetes can help reduce inequalities and bring significant savings. For instance, a previous study in North Carolina found $225 million in potential savings from diabetes-related expenditures from addressing racial and economic disparities in diabetes prevalence.38 Other work highlights that for some racial/ethnic groups, such as working age and elderly Native Hawaiian men,12 reducing prevalence alone will help, but will not fully resolve, diabetes-related preventable hospitalization disparities. We also must improve health care access to quality primary care and issues of social and economic vulnerability.

There are successful examples of such efforts, such as CareOregon with a multidisciplinary, coordinated medical home program that has reduced potentially preventable hospitalization rates.39 There are costs to these efforts as well. However, “estimates of the excess costs associated with potentially preventable hospitalizations can help communities justify investments in primary care that ultimately lead to reduced hospitalizations.”16 In recent innovative work by the Commonwealth Care Alliance and Intermountain Healthcare, savings on preventable hospitalizations offset program costs.39

Limitations

This study has many strengths, including a sample with large numbers of understudied Asian American and Pacific Islander groups across multiple hospitals and payers. However, the study has some limitations. First, the cost estimates are based on facility claims. Though we adjust using a well-established method (cost to charge ratio), this may not truly represent actual costs. Furthermore, these costs are from the hospital only. We do not have information on physician services or other outpatient services. Additionally, our study is descriptive in nature. We are not able to elucidate reasons for cost differences. We are also using administrative data, which does not include many important sociodemographic or environmental factors that may be relevant, such as education or social support and caregiving.3,40 As mentioned above, these estimates of cost sharing do not account for indirect costs, which could be considerable, particularly if the hospitalized individual is the primary wage earner. An amputation is a particularly serious complication, with lasting repercussions long beyond the hospital. We are unable to measure the costs burdens of these issues, but these burdens are likely to fall disproportionately by race/ethnicity.

We are unable to compare findings with U.S. data for disaggregated Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders as, to our knowledge, such data do not exist. We believe this is both a limitation of our study, but also a strength as we hope that strong evidence from a state with substantial proportions of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders and the ability to capture this diversity in existing data systems can provide critical benchmarks for comparative research in other locations. This is an important topic for further research.

Future research should also include more detailed information from outpatient data to understand better the specific pathways to preventable hospitalizations for individuals and how these pathways might vary by race/ethnicity. More detailed inpatient experience data would also be helpful to consider which procedures and/or clinical factors impact the differences seen in health care costs by race/ethnicity. There may be disparities in care that paradoxically lower hospitalization costs. For instance, CHF care in Whites may be more costly because they have increased access to services compared to other racial/ethnic groups. Future research can provide insight on this topic.

Conclusions

Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders include some of the fastest growing racial/ethnic groups in the U.S. We identify a large cost burden for potentially preventable hospitalizations in Native Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders. While overall the cost per hospitalization did not differ significantly by race/ethnicity, variation was seen by race/ethnicity for some types of preventable hospitalizations. For instance, costs for preventable diabetes-relatable amputations (the most expensive of the seven types of tested preventable hospitalizations) were significantly higher for Native Hawaiians, Japanese, and other Pacific Islanders compared with Whites. In contrast, costs for preventable congestive heart failure hospitalizations (the most common of the seven types of tested preventable hospitalizations) were significantly higher for Whites than Native Hawaiians, Japanese, and other Pacific Islanders. Further research is needed to better understand the reasons why the direction of disparities differs by type of preventable hospitalizations. In any case, reducing potentially preventable hospitalizations would not only improve health equity, but could also relieve a large and disproportionate cost burden on some Pacific Islander and Asian American communities, the government, and hospitals.

Acknowledgments

Funding: The research described was supported by National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) Grant P20 MD000173 and was also supported in part by NIMHD grants U54MD007584 and G12MD007601, grant P20GM103466 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, and grant RO1HS019990 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The opinions expressed in this document are those of the authors and do not reflect the official position of NIMHD, NIH, AHRQ, or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

List of Abbreviations

- AF

Adjustment factor

- AHRQ

Agency for Health Care Research and Quality

- CVD

Cardiovascular disease

- CCI

Charlson Comorbidity Index

- CI

Confidence Interval

- CHF

Congestive Heart Failure

- CCR

Cost/charge ratio

- DM

Diabetes

- HHIC

Hawaii Health Information Corporation

- RE

Ratio estimates

- SD

Standard Deviation

- U.S

United States

Appendix

Multivariable Model Predicting Preventable Hospitalization (PH) Costs Controlling For Other Factorsa,b

| Variable | Comparison | Ratio Estimate | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Race/Ethnicity | Chinese vs. Whites | 0.99 [0.88, 1.11] | 0.82 |

| Filipino vs. Whites | 0.99 [0.93, 1.05] | 0.73 | |

| Hawaiian vs. Whites | 1.06 [1.00, 1.12] | 0.06 | |

| Japanese vs. Whites | 1.06 [1.00, 1.12] | 0.07 | |

| Other Asian vs. Whites | 0.96 [0.87, 1.07] | 0.50 | |

| Other PI vs. Whites | 0.91 [0.82, 1.01] | 0.07 | |

| Others vs. Whites | 0.96 [0.90, 1.03] | 0.27 | |

| Samoan vs. Whites | 0.95 [0.79, 1.13] | 0.54 | |

| PH Type | DM Uncontrolled vs. CHF | 0.58 [0.51, 0.67] | <.0001 |

| DM short-term vs. CHF | 0.87 [0.82, 0.93] | <.0001 | |

| DM long-term vs. CHF | 1.05 [1.00, 1.09] | 0.04 | |

| DM extremity vs. CHF | 2.21 [2.04, 2.39] | <.0001 | |

| Hypertension vs. CHF | 0.75 [0.70, 0.79] | <.0001 | |

| Angina vs. CHF | 0.61 [0.56, 0.66] | <.0001 | |

| Insurance | DOD vs. Private | 1.25 [1.14, 1.38] | <.0001 |

| Medicare vs. Private | 1.12 [1.08, 1.16] | <.0001 | |

| Medicaid vs. Private | 1.11 [1.07, 1.15] | <.0001 | |

| Others vs. Private | 1.07 [1.00, 1.13] | 0.05 | |

| Age Group | 50–64 vs. <50 | 1.12 [1.07, 1.17] | <.0001 |

| 65–79 vs. <50 | 1.06 [1.00, 1.12] | 0.03 | |

| 80+ vs. <50 | 1.02 [0.96, 1.09] | 0.54 | |

| Gender | Female vs. Male | 1.04 [1.02, 1.06] | 0.0007 |

| Island | Maui vs. Oahu | 1.38 [1.16, 1.64] | 0.0002 |

| Hawaii vs. Oahu | 1.17 [1.03, 1.31] | 0.01 | |

| Kauai vs. Oahu | 1.27 [1.04, 1.54] | 0.02 | |

| Others vs. Oahu | 1.32 [1.06, 1.65] | 0.01 | |

| Substance Use | Substance use vs. No | 1.06 [1.02, 1.11] | 0.005 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | CCI | 1.04 [1.04, 1.05] | <.0001 |

Also controlling for hospital and interactions for race/ethnicity with age group and with preventable hospitalization type.

Gamma regression with log link was used for multivariable analysis.

Contributor Information

Tetine L. Sentell, Associate Professor with the Office of Public Health Studies at the University of Hawai’i at Manoa.

Hyeong Jun Ahn, Research Biostatistician with the Biostatistics Core at the John A. Burns School of Medicine, University of Hawai’i.

Jill Miyamura, Vice President at the Hawaii Health Information Corporation.

Deborah T. Juarez, Associate Professor at the Daniel K. Inouye College of Pharmacy, University of Hawai’i at Hilo.

References

- 1.Hoeffel EM, Rastogi S, Ouk Kim M, et al. The Asian population: 2010. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2012. Available at: https://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-11.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. Census Bureau. Asian/Pacific American heritage month: May 2013. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Commerce; 2013. Available at: http://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/pdf/cb13ff-09_asian.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mau M, Sinclair K, Saito E, et al. Cardiometabolic health disparities in Native Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders. Epidemiol Rev. 2009;31:113–129. doi: 10.1093/ajerev/mxp004. Epub 2009 Jun 16. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ajerev/mxp004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Chronic care: making the case for ongoing care. Princeton, NJ: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 2010. Available at: http://www.rwjf.org/content/dam/farm/reports/reports/2010/rwjf54583. [Google Scholar]

- 5.King GL, McNeely MJ, Thorpe LE, et al. Understanding and addressing unique needs of diabetes in Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders. Diabetes Care. 2012 May;35(5):1181–8. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0210. http://dx.doi.org/10.2337/dc12-0210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sentell TL, Ahn HJ, Juarez DT, et al. Comparison of potentially preventable hospitalizations related to diabetes among Native Hawaiian, Chinese, Filipino, and Japanese elderly compared with Whites, Hawai’i, December 2006–December 2010. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013 Jul 25;10:E123. doi: 10.5888/pcd10.120340. http://dx.doi.org/10.5888/pcd10.120340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agency for Health Research and Quality (AHRQ) Prevention quality indicators overview. Bethesda, MD: AHRQ; 2011. Available at: http://www.qualityindicators.ahrq.gov/modules/pqi_overview.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jiang HJ, Russo CA, Barrett ML. Nationwide frequency and costs of potentially preventable hospitalizations, 2006. Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 2009. Available at: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb72.jsp. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCarthy D, How SKH, Schoen C, et al. Aiming higher: results from a state scorecard on health system performance. New York, NY: The Commonwealth Fund; 2009. Available at: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/~/media/Files/Publications/Fund%20Report/2009/Oct/1326_McCarthy_aiming_higher_state_scorecard_2009_full_report_FINAL_v2.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hernandez AF, Curtis LH. Minding the gap between efforts to reduce readmissions and disparities. JAMA. 2011 Feb 16;305(7):715–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.167. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.2011.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joynt KE, Jha AK. A path forward on Medicare readmissions. N Engl J Med. 2013 Mar 28;368(13):1175–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1300122. Epub 2013 Mar 6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1300122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sentell TL, Ahn HJ, Juarez DT, et al. Disparities in diabetes-related preventable hospitalizations among working-age Native Hawaiians and Asians in Hawai’i. Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2014 Dec;73(12 Suppl 3):8–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sentell T, Miyamura J, Ahn HJ, et al. Preventable hospitalizations for congestive heart failure in Native Hawaiian, Filipino, and Japanese adults compared with Whites. J Immigr Minor Health. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s10903-014-0098-4. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moy E, Mau M, Raetzman S, et al. Ethnic differences in potentially preventable hospitalizations among Asian American, Native Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders: implications for reducing health care disparities. Ethn Dis. 2013 Winter;23(1):6–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghosh C. Healthy People 2010 and Asian Americans/Pacific Islanders: defining a baseline of information. Am J Public Health. 2003 Dec;93(12):2093–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.12.2093. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.93.12.2093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moy E, Barrett M, Ho K. Potentially preventable hospitalizations - United States, 2004–2007. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2011 Jan 14;60(Suppl):80–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hixson L, Hepler BB, Ouk Kim M. The Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander population 2010. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2012. Available at: http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-12.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 18.US Census Bureau. US Census Bureau delivers Hawaii’s 2010 census population totals, including first look at race and Hispanic origin data for legislative redistricting. Table 3. Population by race alone or in combination and Hispanic or Latino origin, for all ages and for 18 years and over, for Hawaii: 2000 and 2010. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2011. Available at: http://www.census.gov/2010census/news/releases/operations/cb11-cn41.html. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hawaii Health Information Corporation. Hawaii Health Information Corporation Inpatient Data, 2011. Honolulu, HI: Hawaii Health Information Corporation; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang HJ, Andrews R, Stryer D, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in potentially preventable readmissions: the case of diabetes. Am J Public Health. 2005 Sep;95(9):1561–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.044222. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2004.044222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joynt KE, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Thirty-day readmission rates for Medicare beneficiaries by race and site of care. JAMA. 2011 Feb 16;305(7):675–81. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.123. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.2011.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agency for Health Care Research and Quality (AHRQ) Cost To Charge Ratio Files. Rockville, MD: AHRQ; 2013. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Available at: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/state/costtocharge.jsp. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lipscomb J, Weinstein MC, Torrance GW. Time preference. In: Gold M, Siegel J, Russell LB, et al., editors. Cost-effectiveness in health and medicine. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Disease. 1987;40(5):373–83. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare provider utilization and payment data: inpatient. Baltimore, MD: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; 2014. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Medicare-Provider-Charge-Data/Inpatient.html. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lipsky S, Caetano R, Roy-Byrne P. Racial and ethnic disparities in police-reported intimate partner violence and risk of hospitalization among women. Womens Health Issues. 2009 Mar-Apr;19(2):109–18. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2008.09.005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schocken DD, Benjamin EJ, Fonarow GC, et al. Prevention of heart failure: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Councils on Epidemiology and Prevention, Clinical Cardiology, Cardiovascular Nursing, and High Blood Pressure Research; Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group; and Functional Genomics and Translational Biology Interdisciplinary Working Group. Circulation. 2008 May 13;117(19):2544–65. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.188965. Epub 2008 Apr 7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.188965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Basu A, Manning WG, Mullahy J. Comparing alternative models: log vs Cox proportional hazard? Health Econ. 2004 Aug;13(8):749–65. doi: 10.1002/hec.852. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/hec.852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.LaViest TA, Gaskin DJ, Richard P. The economic burden of health inequalities in the United States. Washington, DC: Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies; 2009. Available at: https://www.ndhealth.gov/heo/publications/The%20Economic%20Burden%20of%20Health%20Inequalities%20in%20the%20United%20States.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation. Health insurance coverage of the total population, states (2011–2012) Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2014. Available at: http://kff.org/other/state-indicator/total-population/ [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suthers K. Evaluating the economic causes and consequences of racial and ethnic health disparities. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association; 2008. Available at: http://hospitals.unm.edu/dei/documents/eval_cause_conse_apha.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, editors. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cunningham PJ. Overburdened and overwhelmed: the struggles of communities with high medical cost burdens. New York, NY: The Commonwealth Fund; 2007. Available at: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/usr_doc/Cunningham_overburdenedoverwhelmed_1073_ib.pdf?section=4039. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Daly R. Shifting burdens: hospitals increasingly concerned over effects of cost-sharing provisions in health plans to be offered through insurance exchanges. Modern Healthcare. 2013 Jun 15; Available at: http://www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20130615/MAGAZINE/306159953#. [PubMed]

- 35.Gilman M, Adams EK, Hockenberry JM, et al. California safety-net hospitals likely to be penalized by ACA value, readmission, and meaningful-use programs. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014 Aug;33(8):1314–22. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0138. http://dx.doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McHugh MD, Carthon JM, Kang XL. Medicare readmissions policies and racial and ethnic health disparities: a cautionary tale. Policy Polit Nurs Pract. 2010 Nov;11(4):309–16. doi: 10.1177/1527154411398490. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1527154411398490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hanlon C, Hinkle L. Assessing the costs of racial and ethnic health disparities: state experience. Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 2011. Available at: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/race/CostsofDisparitiesIB.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Buescher PA, Whitmire JT, Pullen-Smith B. Medical care costs for diabetes associated with health disparities among adult Medicaid enrollees in North Carolina. N C Med J. 2010 Jul-Aug;71(4):319–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Innovation profile: plan-funded team coordinates enhanced primary care and support services to at risk seniors, reducing hospitalizations and emergency department visits. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008. Available at: http://www.innovations.ahrq.gov/content.aspx?id=2243. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Billings J. Using administrative data to monitor access, identify disparities, and assess performance of the safety net. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2003. Available at: http://archive.ahrq.gov/data/safetynet/billings.htm. [Google Scholar]