Abstract

Background

Smaller businesses differ from their larger counterparts in having higher rates of occupational injuries and illnesses and fewer resources for preventing those losses. Intervention models developed outside the United States have addressed the resource deficiency issue by incorporating intermediary organizations such as trade associations.

Methods

This paper extends previous models by using exchange theory and by borrowing from the diffusion of innovations model. It emphasizes that occupational safety and health (OSH) organizations must understand as much about intermediary organizations as they do about small businesses. OSH organizations (“initiators”) must understand how to position interventions and information to intermediaries as added value to their relationships with small businesses. Examples from experiences in two midwestern states are used to illustrate relationships and types of analyses implied by the extended model.

Results

The study found that intermediary organizations were highly attuned to providing smaller businesses with what they want, including OSH services. The study also found that there are opinion leader organizations and individual champions within intermediaries who are key to decisions and actions about OSH programming.

Conclusions

The model places more responsibility on both initiators and intermediaries to develop and market interventions that will be valued in the competitive small business environment where the resources required to adopt each new business activity could always be used in other ways. The model is a candidate for empirical validation, and it offers some encouragement that the issue of sustainable OSH assistance to small businesses might be addressed.

Keywords: small business, occupational safety, occupational health, intervention model

INTRODUCTION

About 79% of business establishments in the United States have fewer than 100 employees, and they employ about 35% of the workforce. Workers in these smaller businesses endure a disproportionate share of the burden of occupational injuries, illnesses, and fatalities [Jeong, 1998; Hinze and Gambatese, 2003; Fabiano et al., 2004; Fenn and Ashby, 2004; Morse et al., 2004; Mendeloff et al., 2006; Buckley et al., 2008; Page, 2009]. They also engage in fewer safety activities than larger businesses. A national survey of U.S. firms with fewer than 250 employees found that 87% of the firms did not have a safety committee, 39% did not include safety awareness information in new employee orientation, 45% did not have written safety rules or policies, and 87% had not used a safety consultant in the past 5 years [Dennis, 2002]. The smallest firms (<10 employees) reported being engaged in safety activities less than somewhat larger firms (10–19 employees), which reported less engagement than even larger firms (20–249 employees).

There are a number of likely reasons for these differences. Smaller businesses have less capacity than larger organizations to devote to activities that are not necessarily viewed as production related [Page, 2009]. Managers’ inexperience and isolation from peer networks, and their inaccurate perceptions about illness and injury risk (because of low frequency) may also contribute to their lack of occupational safety and health (OSH) knowledge and low motivation to engage in prevention activities [Dennis, 2002; Champoux and Brun, 2003; Barbeau et al., 2004; Walker and Tait, 2004; Hasle and Limborg, 2006; Haslam et al., 2010]. Communications between managers and employees about the causes of workplace injuries can be counterproductive as managers sometimes attribute safety issues to external causes such as bad luck rather than to circumstances within the control of the organization [Hasle et al., 2009].

Although all employers are responsible for protecting the health and safety of their workers, smaller businesses may need more assistance from external organizations (e.g., government and insurance agencies) to do that than larger businesses. But external forces are often ill-suited to supporting OSH in smaller businesses. The likelihood of facility inspections by external organizations is lower for smaller businesses. In addition, traditional social structures and processes, such as OSH regulations, consultation services, and professional practices, often do not suit conditions in smaller enterprises [Eakin et al., 2010]. Assistance is often too technical, perceived to be too expensive, or in too-limited supply.

Recent models from Denmark and New Zealand for providing small businesses with information and services have introduced the concept of intermediary organizations as delivery channels. These organizations bridge the gap between initiating public health/safety organizations and small businesses as a means to overcome the resource scarcity issue [Hasle and Limborg, 2006; Hasle et al., 2012; Olsen et al., 2012]. Intermediary organizations are organizations that deliver goods or services to small businesses and that might also deliver OSH information and programs.

From our own experiences in the US, we concluded that for the initiator-intermediary-small business intervention diffusion model to work, initiating organizations must understand and cultivate intermediary organizations as much as they do small businesses because both have to be motivated to act. We also observed that organizations interact on an exchange basis, that is, that there is an expectation that each side will gain something in business-to-business relationships and that this too must be considered by those wishing to bring more OSH information, products, and services to small businesses.

The purpose of this paper is to extend existing safety and health intervention diffusion models for small businesses. We do this by applying theoretical perspectives that elevate the essential element of organizational relationships—the exchange. We will do the following:

Review existing small business intervention models that feature intermediary organizations.

Using ideas from diffusion of innovations and social exchange theory, extend these models by adding steps to the initiator-intermediary organization relationship that parallel the intermediary-small business relationship steps of other models.

Use our recent experiences working with small businesses and two local chambers of commerce in the US to illustrate the advantages of the extended model.

The small business intervention models considered here focus primarily on social systems. In that respect, they are different from health behavior theories that inform a great deal of public health practice and research, including some small business OSH research [Brosseau et al., 2002]. Such theories focus on changing the knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, emotions, and behaviors of individuals as well as altering some environmental or social systems factors. By contrast, the models considered here include those elements but shift emphasis to environmental factors and characteristics of OSH interventions. There is significant overlap in these types of intervention models, and both are needed.

The development of the model presented here was informed by the authors’ efforts with smaller businesses over the past three years as managers of the Small Business Assistance and Outreach Program of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). We worked with a small group of state and local organizations in Ohio and Kentucky to better understand initiator-intermediary and intermediary-small business relationships. For purposes of this paper, NIOSH is the initiator organization. The intermediary organizations included 15 local chambers of commerce (ranging from 50 to 4,000 members), two state-level trade associations (construction and food service), the Ohio Bureau of Workers’ Compensation, and small business development centers (funded by federal, state, and local sources combined). The authors assisted those organizations in their efforts to transmit OSH information and to train more than 2,000 small business owners or managers about OSH best practices. In so doing, we have been able to talk with both intermediary and small business managers directly about their views of OSH activities.

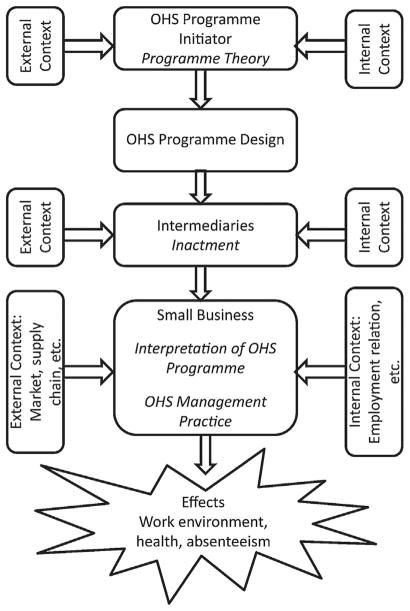

EXISTING MODELS FOR OSH INTERVENTION DIFFUSION TO SMALL BUSINESSES

Hasle and Limborg summarized studies that used different kinds of organizations to deliver OSH interventions to small businesses. Researchers found these intermediary organizations were necessary because (a) OSH interventions for small businesses must be simple so that they can be delivered by organizations who are not necessarily OSH experts, (b) OSH interventions are better conveyed by face-to-face communications, and (c) the number of small businesses is beyond the capacity of most government OSH programs [Hasle and Limborg, 2006]. Examples of intermediary organizations are occupational health service providers, insurance companies, labor unions, accountants, and chambers of commerce. Hasle and Limborg concluded their review with a model for OSH interventions in small businesses (Fig. 1). The model reflects two stages of information exchange, first between the initiating organization and an intermediary organization and then between the intermediary and small businesses. The small business then goes through an internal adoption process of integrating interventions with current processes and measuring intervention effects. As simple as the model is, it represents a significant step forward. It compels consideration of the organizations that interact with small businesses. Partial support for this model was found by a study in Denmark that used small business accountants as OSH intermediaries [Hasle et al., 2010].

FIGURE 1.

Model for intervention research in small enterprises [Hasle and Limborg, 2006] used with permission.

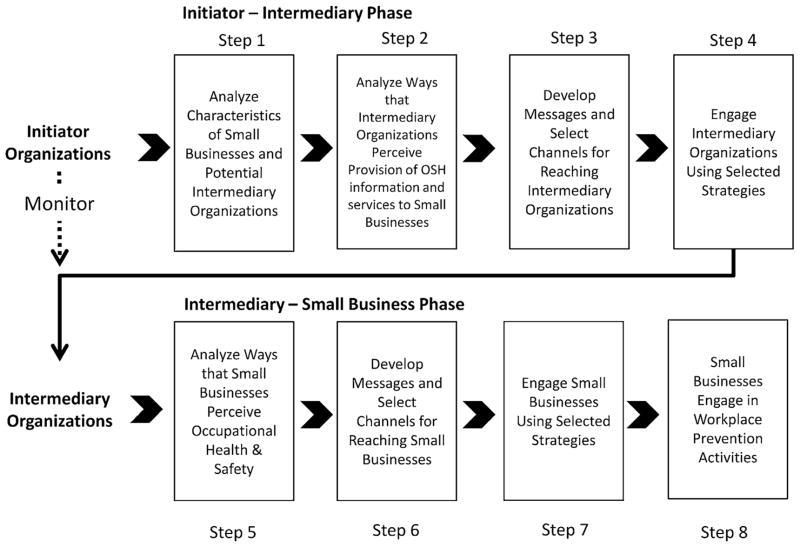

Olsen et al. [2012] (including Hasle) used program theory to add useful detail to the first model (Fig. 2). Program theory presumes that three mechanisms affect changes in small business OSH: (1) provision of information, (2) incentives, and (3) demands or controls, with the threat of sanctions for non-compliance attendant to the demands. In Olsen’s model, these mechanisms are employed strategically by the “initiator” organization, often a governmental body. The initiator develops OSH-focused interventions for small businesses. Intermediary organizations play a role in the delivery of those interventions to small businesses. The model recognizes that all three types of organizations (initiator, intermediary, and small business) are affected by internal and external issues, which underscores the complexity of the social system and the difficulties for initiators in achieving objectives. The authors used example OSH programs from government agencies in New Zealand to show practical applications of the model.

FIGURE 2.

Schematic simple model of the programme theory chain [Olsen et al., 2012] used with permission.

One limitation of the Olsen model is that it does not reflect that the three drivers must be strategically applied by the initiator to interactions with the intermediary organizations as surely as the intermediaries must apply them to interactions with small businesses. The model also implies that the initiator is a national force with the all-important commensurate resources to affect changes down to the employer/employee level. But that degree of reach and those resources are seldom available at the initiator level. After trying to stimulate Danish accountants to deliver OSH information to their small business clients, researchers concluded that outside resources would be needed from somewhere to sustain accountant training and accountants’ interest in engaging their clients on OSH issues [Hasle et al., 2010]. In addition, the “powerful initiator” construct neglects the perspectives of small businesses and intermediary organizations in the change process. The next section describes how these issues may be partially addressed through attention to the nature of the transactions between organizations.

SOCIAL EXCHANGE THEORY

Social exchange theory was developed more than fifty years ago as a way to explain human relationships [see Miller, 2005 for an introduction]. It presumes that an intuitive cost-benefit analysis drives those relationships; that people and organizations act to maximize their benefits and minimize their costs. If the costs exceed the benefits, the relationship will not survive. People and organizations engage in relationships with an expectation of reciprocity; there is an assumption that the other side is acting in a similar manner.

Small businesses have relationships with goods and service providers that serve production processes. Other typical services include accounting, finance, legal, insurance, human resource, marketing, and peer networking. Human resource services include drug screening, workers’ compensation, health care benefits, and occupational health clinic services. These relationships usually involve an economic exchange—goods or services delivered for a fee. They also likely involve a social exchange—interpersonal, reciprocal exchanges that result in increased trust and loyalty, conferred credibility, and more knowledge [Cropanzano and Mitchell, 2005]. The objective of the relationships is mutual benefit, and that comes from each side finding value in what the other side offers [Gronroos, 2011]. Suppliers enhance their relationships with small businesses by tailoring their goods and services to small business needs [Rahikka et al., 2011].

Social exchange theory guides OSH intervention diffusion at the social systems level to focus on positioning OSH as value-added to business-to-business relationships. A supplier is not likely to be a conduit for OSH information and prevention services to small businesses unless it is either paid to do so by a third party—which is unlikely on any sustained basis—or it knows that small businesses see value in that information and those services. This perspective refocuses OSH initiating organizations on how to convince suppliers that on both an economic and a social exchange basis, offering OSH information and/or services will enhance their value to small businesses. Once both parties see the value of an exchange, it is sustainable until benefits no longer outweigh costs for one or both parties. This helps solve the lack of resources problem for OSH initiating organizations. Thus the job of the initiator is to understand and demonstrate the value of OSH to suppliers and the small businesses they serve.

AN EXTENDED MODEL FOR SMALL BUSINESS OSH INTERVENTION

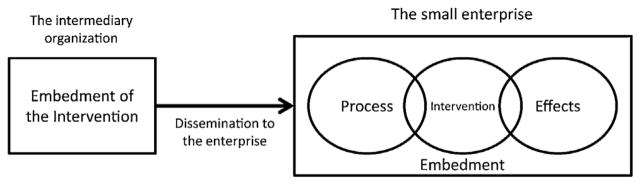

The diffusion of innovations model is the primary influence on the extended small business OSH intervention research model that we propose (Fig. 3). A communications model that is based on ideas about social exchange, the diffusion of innovations model maps how new ideas move through a social system over time. It focuses research on characteristics of the intervention, characteristics of the target audiences, communication channel selection, and time to adoption, or the “purchase decision” in marketing terms. The diffusion model has been used extensively to investigate the adoption of innovations by organizations as well as individuals, particularly in public health and healthcare [Rogers, 2003; Brownson et al., 2007; Wilson et al., 2010; Greiver et al., 2011; Bowen et al., 2012; Cragun et al., 2012; Pombo-Romero et al., 2012; Wood et al., 2012].

FIGURE 3.

Extended model for small business OSH intervention research.

OSH activities may not be viewed as “innovations,” but they are often new to small businesses. The elements of the model offer guidance for both the “initiator to intermediary” stage (top half of Fig. 3) and the “intermediary to small business” stage of diffusion (bottom half). The steps in each stage are similar, but different types of organizations execute them to achieve different objectives. OSH initiator organizations often have a public health mission. However, any organization seeking to advance small business OSH objectives with the assistance of other organizations may be an initiating organization, for example, a university, a professional society, or a non-government organization.

Step 1: Analyze Needs of Small Businesses and the Characteristics of Intermediary Organizations That Serve Them

In Step 1, the initiator organization identifies the workplace health and safety needs of small businesses in its geographic area using quantitative and qualitative data from community sources such as government health departments, workers’ compensation insurers, occupational health clinics and community leaders. Then the initiator shifts focus to finding and understanding organizations that interact with targeted groups of businesses. The objective is to find organizations that may be persuaded to start or increase their delivery of OSH information, products, or services to small businesses.

Larger businesses may have expertise in OSH that they are willing to share, making them effective intermediaries, as most have business relationships with smaller enterprises. Larger businesses may even require a certain level of OSH competency from small suppliers as a condition of purchases, and they may help suppliers attain that competency in the interest of protecting themselves from interruptions in service or supplies due to OSH problems at the vendor.

Membership organizations (such as trade associations and chambers of commerce) and training/education organizations (such as community colleges and business schools), and government agencies may be good intermediaries. They provide information and assistance on business issues, often in exchange for membership or course fees, but there is a strong social exchange dimension to these relationships as the parties share experiences and knowledge through networking events. That dimension can be vital to securing and maintaining interest in OSH interventions. Suppliers of professional services such as accounting, legal, managerial, engineering, risk management, and business insurance may be good intermediaries. Providers of workplace health promotion services have an obvious connection with OSH services.

The potential use of customer groups to influence OSH activities in small businesses does not seem like a useful intermediary group at this time. A study found that concerns about negative publicity and/or public opinion affected small business’s attitudes and behavior on environmental issues but not OSH issues [Gunningham et al., 1998]. However, if societies begin to see increased connection of OSH with health, safety, or environmental issues, then those networks may be useful, too.

The initiator should find the best intermediaries by looking at their mission statements, strategic plans, management, and current product and service lines. No one characteristic signals a great intermediary, but better intermediaries may be:

Committed to alignment of OSH activities with their business interests.

Already engaged in delivery of OSH products and/or services.

Seeking new ways to provide goods and services to small businesses.

Connected to small businesses through formal, informal, or interpersonal relationships.

Innovative organizations with innovative management.

An innovative organization is indicated by structural complexity, lack of centralization and formality, interconnectedness, slack resources, larger size, and a positive attitude toward change among leadership, among other characteristics [Rogers, 2003; Medina et al., 2005]. Often multiple intermediary organizations working together or in parallel are likely to be more effective than the actions of a single organization. Intermediaries are often engaged in OSH as merely one aspect of their business relationships. The use of multiple intermediaries increases both the time available for OSH efforts and, since they have different client bases, increased reach to small businesses. Step 1 is complete when the initiator knows one or more organizations that meet one or more of the above criteria.

Step 2: Analyze How Intermediaries Perceive OSH

In Step 2, the initiator organization works to understand how selected intermediaries perceive OSH information and programs for small businesses. Perceptions about new products or ideas that affect their appeal include relative cost, advantages over other options, compatibility with existing systems, lack of complexity, trialability, and easily observable results of adoption [Dearing and Meyer, 1994; Rogers, 2003]. Intermediaries will be more accepting of the idea of adding OSH products and services if they perceive them as having as many of those characteristics as possible. For example, a chamber of commerce will be more likely to add small business safety workshops to its programming if it is convinced that such workshops fit with programming it already offers small businesses, that it can do so without significant added expense, and that safety workshops are as or more likely to attract new members than other content. Step 2 is complete when the initiator has talked with intermediary organizations and understands how they view OSH’s potential to add to their exchanges with small businesses.

Step 3: Develop Messages and Select Channels That Will Reach Intermediaries

Active diffusion begins when the initiator develops and delivers tailored information about OSH to selected intermediary organizations. In Stage 3, data from Stage 2 are used to make decisions about message content and channel for delivery. For example, if an insurance company (an intermediary) thinks that its sales agents are not capable of learning enough about OSH to be effective trainers of small business clients because of the technical nature of the issues, the initiator might focus on emphasizing that delivery of even rudimentary OSH information could be beneficial to the company’s policy holders. Practically, Steps 2 and 3 are most effectively done in an iterative manner. As the initiator organization learns about perceived strengths and weaknesses of OSH programming and as those perceptions change over time, it adjusts its messages for intermediaries.

A primary channel for these communications is interpersonal. Intermediaries must be convinced to commit a substantial amount of resources, and often decision makers are most effectively convinced by face-to-face interaction. However, other channels must be used too. Information-seeking research can identify which channels are most commonly used by targeted intermediaries. Those analyses should be augmented by strategic selection of message channels based on their “yield” of targets reached for a given cost. There is a large and growing array of communication channels that can be used, including webinars, social media, and mobile applications. The use of social media for business communications has considerably increased the number of such channels, but their relative effectiveness is not settled. Health communications researchers can be valuable members of the small business OSH research effort. Step 3 is complete when a strategic communication plan is in place.

Step 4: Engage Intermediary Organizations Using Selected Strategies

In Step 4, the initiator organization executes its persuasion campaign targeting intermediaries. An important strategy is to identify and enlist both opinion leaders and a champion. Opinion leaders are looked to by others within the organization for explicit or tacit endorsement of new ideas. Champions are skilled at getting things done. Time is also an important dimension of the diffusion model. The variable of time guides investigation of the “embedding” process proposed by Hasle and Limborg. Change does not occur in organizations instantly, but rather through stages. Within an organization, researchers have learned that innovation adoption is usually triggered by a perceived organizational performance deficiency [Rogers, 2003]. Unless those in the organization see that something is affecting organization performance, changes are unlikely. The recognition stage is followed by a search for interventions that lessen or eliminate the deficiency. When the best fit is found, the organization makes the intervention a routine part of operations [Rogers, 2003].

Step 4 is complete when targeted intermediary organizations decide to offer small businesses more OSH resources and assistance. Initiator organizations must monitor the activities of target organizations to detect such decisions and ensuing activities. They must do so because if their diffusion efforts are truly successful, the intermediary organizations will consider the decision to do more in OSH to have been a largely internal decision, and they will not think to advise the initiator organization. A regular phone call or other form of contact to inquire about the intermediaries’ activities along with the monitoring of their communications to others (newsletter or social media) will help track organizations’ behaviors.

Steps 5–8: Delivery of OSH Services to Small Businesses by Intermediaries

In Steps 5–8, intermediary organizations engage small businesses using the same process that the initiator organization used to engage intermediaries (see Fig. 3). They work to understand the needs of small business targets and their attitudes toward OSH (Step 5). They develop or select OSH products or services that they can offer and that will be valued. Then they develop strategies to make small businesses aware of what they now offer (Step 6). In Steps 7 and 8, they engage the businesses and deliver the products or service which are then used by the businesses. Throughout, the initiator must monitor these steps. The initiator organization is especially interested in Step 8, small businesses’ engagement, because that final step involves prevention activity by the small business that leads directly to fewer workplace injuries, illnesses, and fatalities.

Example: Chambers of Commerce

NIOSH is using this model to guide investigation of the potential of different kinds of intermediary organizations to reach small businesses. In this section the steps of the model are illustrated by NIOSH’s recent work as initiator with two chambers of commerce (intermediaries).

Step 1

There are more than 12,000 chambers worldwide with more than 40 million business members. There are more than 3,000 chambers in the U.S. with at least one staff person. There are thousands more that are entirely volunteer organizations [International Chamber of Commerce, 2013]. Geographically based, chambers work to support local businesses and communities with networking, programs, and advocacy services. In the model found in the US and many other nations, businesses pay a fee to become a chamber member which gives them access to these services for reduced or waived fees. Member organizations are also asked to donate volunteer time to chamber activities [American Chamber of Commerce Executives, 2009]. Chamber members are overwhelmingly small businesses, and they cross all industry sectors which makes chambers of commerce attractive as potential intermediaries.

Step 2

After talking with several chambers of commerce about their health and safety related activities, we were convinced that we needed to join a chamber and use observer-participant methods to adequately conduct Steps 2–4 of the model. From 2011 to the present, for research purposes, NIOSH joined two chambers in the midwest US. One had approximately 5,000 member organizations and the other 1,500. The authors attended numerous networking and programming events sponsored by both chambers. One chamber shared its strategic plan. We noted opportunities in selected strategic goals: “Slow increasing health care costs for businesses,” “Retrain and educate current and future workforce,” and “Provide start-up businesses resources and training.”

Step 3

To understand the ways that the chambers perceived OSH services, NIOSH staff joined internal, volunteer member, chamber steering committees for (a) small business, (b) health, and (c) workplace safety. Each committee is supported by a chamber staff person. The committees determine program content (usually workshops or seminars) that the chambers produce using mostly the expertise of its members. Decisions are made based on the priorities of attracting new members and servicing existing members. In evaluating alternatives, committee members frequently apply a group judgment about the needs and desires of the chamber’s members. Each committee has a different perspective on workplace health and safety. Members of the small business committee in one chamber see OSH issues as just one element of risk management and as one of many topics of interest to entrepreneurs. Within risk management, they find issues such as protection of tangible and intellectual property to be more compelling chamber programming topics than OSH, although they were willing to consider OSH programming. While focused primarily on workplace health promotion, the health committees are open to considering OSH programming if it is about a health issue. They were receptive to programming about the value of combining corporate workplace wellness and workplace safety and health efforts and stress reduction topics.

Both chambers have workplace safety committees, which is apparently not common in the US. These committees are fully engaged in OSH program development. Seminar and workshop content focuses more on safety than health issues. Members of the committee are usually employees of companies that are large enough to have a functioning OSH program. However, they are careful to try to serve the interests of small businesses. Programming about regulation-driven issues is common, but other issues receive attention too. The larger chamber’s workplace safety activities are subsidized by a state bureau of workers’ compensation. That support enables them to have monthly meetings. With less support and fewer members, the smaller chamber meets quarterly.

Step 4

NIOSH’s engagement strategies differ by chamber. For the larger one—already active in OSH seminars and supported financially—NIOSH is encouraging alternative OSH topics and seminar presentation methods. For example, we demonstrated how hazard mapping—a risk assessment technique—could be taught to employers by using small discussion groups instead of a presentation format. Affecting more changes in this larger chamber may be beyond NIOSH’s available resources as there are more decision makers who must be influenced.

Steps 5–8

Based on its judgment about where it could have the most influence, NIOSH has devoted more time to the smaller chamber and seen more results. With NIOSH’s encouragement, it applied (however, unsuccessfully) for a national grant to provide OSH training to local businesses. It planned and executed its first-ever conference on workplace health and safety. The half-day event included concurrent sessions on fire protection, personal protective equipment, the aging workforce, the role of the occupational health clinic, emergency planning for small businesses, workers’ compensation insurance, and legal aspects of health and safety. The conference achieved good attendance by area small businesses and achieved sufficient sponsor support to defray expenses. The chamber is considering repeating the conference because it sees the need for it among its members and that it may be sustainable through sponsorships. The sponsors for the event included a hospital with an occupational health clinic, a company that sells fire and personal protective equipment, and a manufacturing company. And, there may be other potential sponsors within the chamber. More importantly, the chamber is sharing its success with other chambers at the state and national level through a professional association of programming executives. Other activities that we stimulated at this chamber included a seminar on how to plan for and respond to an influenza outbreak (for their small business group), and a presentation on job stress reduction for their human resources group.

The health committees of both chambers saw the value of the idea of combining workplace health promotion with OSH management an idea suggested by the Total Worker Health approach [NIOSH, 2012]. Both committees staged a seminar on the topic for their chamber’s members. NIOSH arranged for speakers on hazard mapping, hazard communications, job stress, and manual materials handling equipment (to reduce injuries from lifting) for the larger chamber’s safety council. Additionally, NIOSH convinced the larger chamber to survey its smaller business members to identify potential topics for future safety council meetings.

The numerous lessons we have learned from working with these chambers support the model in the following ways.

The model’s emphasis on analysis of intermediaries is appropriate. We learned that the two chambers differed significantly. The larger chamber’s staff seem to take more leadership roles and to make more programming decisions, although sometimes with help from experts in content areas, whether OSH or other areas. The smaller chamber’s staff usually took more of a support role to membership committees. Those members made programming decisions. This difference may or may not be related to the chambers’ sizes. Learning about intermediaries, how they operate, and where the locus of power is within the organization is a critical task for initiators.

Intermediaries are driven by what small businesses want. There are opportunities for initiators to influence programming decisions, but in both chambers, the perspectives of their members was the most important determinant of their actions. Often employers’ concerns were driven by OSH-related issues in the news, for example, the threat to businesses of the H1N1epidemic or incidents of a “live shooter” at a business. But more basic topics were also selected for programming (developing safety climate, hazard recognition) by the members.

There are opinion leaders and potential OSH champions in intermediaries who are instrumental in achieving change. We found that larger businesses gave more volunteer time to developing and presenting OSH programming than smaller businesses. Often they were listened to by other members, that is, they were opinion leaders. Their reputations for organizational success with OSH conferred credibility. In addition, some individuals from those opinion leader organizations took leadership roles in planning and delivering a chamber’s OSH outreach to small businesses that is, they were champions for OSH. Whether in an opinion leader or a champion role, these individuals and organizations seemed willing to devote their time and resources to helping small businesses. Although the motivations for this behavior are not entirely clear, there was a significant desire on the part of larger organizations to provide OSH assistance and mentoring to smaller businesses in their communities.

DISCUSSION

The extended small business OSH intervention diffusion model accomplishes several things. It builds on previous models that feature intervention by intermediaries by fully detailing the implications of a two-stage approach to engagement. It considers those engagements with an exchange perspective—an expectation that there must be something for both parties in each interaction if the exchange is to be sustained across many small businesses. This perspective drives attention to the characteristics of small businesses and intermediary organizations; perceptions about characteristics of OSH innovations; business networks, opinion leaders, and innovation champions; and the time necessary to achieve widespread adoption of innovations. One of the most useful activities to pursue when initiators are assessing the characteristics of intermediaries and small businesses is to consider the strategic direction of each organization. If initiator organizations can find goals and priorities of intermediaries and small businesses that fit with OSH programs, those organizations will be more receptive to OSH initiatives. Similarly, if intermediaries find intersections of their own business goals with those of small businesses, they too will be more successful diffusing OSH. In some cases, an organization’s goals may shift as they discover community resources. A chamber of commerce might add a goal on workforce protection and development if it discovers OSH and workforce training support in its community. Changes in the goals of small businesses or intermediaries to align with initiators’ health objectives are signs of success of initiators’ efforts.

This model calls on initiators to be reflective about their role in improving workplace health and safety for small businesses. It calls on them to come to the effort with a sense that they must find common ground with other organizations in order to succeed. They can not simply present the regulatory, health, and business cases for OSH to intermediary organizations and small businesses. They must offer them something that they can convert into gain for their organizations.

The use of intermediaries has limitations. The complexity of two stages of change makes confirmation of outcomes and causal connections more difficult. When initiators turn to intermediary organizations, they may be exchanging one difficult target population for another. Intermediaries will not have as much expertise or interest in OSH issues as initiators do. That may undermine public health objectives as both initiators and intermediaries negotiate diffusion in ways that serve the intermediary first, small businesses second, and public health objectives third (or not at all). Public health practice must include careful monitoring of diffusion processes for their fidelity to public health objectives. Care must also be taken to not allow small businesses to become so dependent on outside resources that they abdicate their role as the primary party responsible for protection of their employees at work.

The wider lens used by this model is a limitation due to what it does not emphasize. While going considerably beyond the boundaries of each employing organization to explain the intervention process, the complex networks of intermediary organizations that might be needed to reach small businesses are not depicted. The study of the role of networks in social change will grow in importance as social media increase their penetration to business and health communications. The focus of this model on developing mutually beneficial business relationships is the basis for all business-based social media interactions. The horizontal, or business-to-business focus of the model also neglects vertical relationships between customers, employees, and managers and owners. Those relationships are vital to the success of OSH interventions and must be addressed with development of models that parallel and overlap this one. The alignment or partial alignment of business interests envisioned in the model may not be in the best interests of the employees who are the at-risk groups [Eakin et al., 2000].

Finally, more case studies and empirical validation are needed to improve the model. Chambers of commerce occupy a special place in most communities, usually as a well-known representative of both business and community development interests. If some chambers see their business assistance role as including regulatory compliance assistance, business, chamber, and public health objectives may be advanced. Only two chambers were examined in this report, and they differ substantially in their capabilities and interests. They also differ from other types of intermediary organizations in structure, community influence, and objectives. For example, they often have a deep pool of volunteer labor available from their business members, some of them large organizations. Those members also represent a broad range of expertise since chambers aspire to represent all industries in a community. Other types of intermediary organizations do not necessarily have access to the same types or amount of resources. The field will be advanced by recruiting and studying trade associations, insurance companies, occupational health clinics, and other types of community organizations to understand their potential to fill the intermediary role. A key issue is how to find intermediaries that can see OSH as part of their mission. That is the only way to sustainable assistance to small businesses. Initiators must also identify which groups of intermediaries that can act together to optimize delivery of information and services.

CONCLUSION

Given that public health and other agencies do not have the capacity to adequately assist small businesses with OSH because of their large numbers, those agencies must depend on intermediaries who have compatible interests in small enterprises. Partnering with such organizations brings a number of practical and research difficulties, but those partnerships may be the best hope for helping those workers and employers who are most in need of attention in a sustainable way.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Peter Hasle and Jørgen Limborg and to Kirsten Olsen and her colleagues for granting permission to reproduce their models. We are also grateful to Dr. Hasle, Lawrence Chapman, James Dearing, Anthony LaMontagne, and the anonymous reviewers for their comments on drafts of this paper.

Footnotes

The authors performed this work as employees of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. There are no known conflicts of interest. All authors are government employees, and we have no copy rights.

References

- American Chamber of Commerce Executives. Chambers of commerce: The basics. 2009 Retrieved May 7, 2013, from http://www.acce.org/index.php?src=documents&srctype=download&id=92&category=ACCE.

- Barbeau E, Roelofs C, Youngstrom R, Sorensen G, Stoddard A, LaMontagne AD. Assessment of occupational safety and health programs in small business. Am J Ind Med. 2004;45:371–379. doi: 10.1002/ajim.10336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen CM, Stanton M, Manno M. Using diffusion of innovations theory to implement the confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit. J Nurs Care Qual. 2012;27:139–145. doi: 10.1097/NCQ.0b013e3182461eaf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosseau LM, Parker DL, Lazovich D, Milton T, Dugan S. Designing intervention effectiveness studies for occupational health and safety: The Minnesota wood dust study. Am J Ind Med. 2002;41:54–61. doi: 10.1002/ajim.10029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownson RC, Ballew P, Dieffenderfer B, Haire-Joshu D, Heath GW, Kreuter MW, Myers BA. Evidence-based interventions to promote physical activity: What contributes to dissemination by state health departments. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33:S66–S73. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.03.011. quiz S74–S68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley JP, Sestito JP, Hunting KL. Fatalities in the landscape and horticultural services industry, 1992–2001. Am J Ind Med. 2008;51:701–713. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champoux D, Brun J-P. Occupational health and safety management in small size enterprises: An overview of the situation and avenues for intervention and research. Saf Sci. 2003;41:301–318. [Google Scholar]

- Cragun DL, DeBate RD, Severson HH, Shaw T, Christiansen S, Koerber A, Tomar SL, Brown KM, Tedesco LA, Hendricson WD. Developing and pretesting case studies in dental and dental hygiene education: Using the diffusion of innovations model. J Dent Educ. 2012;76:590–601. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cropanzano R, Mitchell MS. Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. J Manage. 2005;31:874–900. [Google Scholar]

- Dearing JW, Meyer G. An exploratory tool for predicting adoption decisions. Sci Commun. 1994;16:43–57. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis WJ, editor. National small business poll: Workplace safety. Washington, DC: National Federation of Independent Businesses; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Eakin J, Lamm F, Limborg H. International perspective on the promotion of health and safety in small workplaces. In: Frick K, Jensen P-L, Quinlan M, Wilthagen T, editors. Systematic occupational health and safety management: Perspectives on an international development. Oxford UK: Elsevier Science; 2000. pp. 227–247. [Google Scholar]

- Eakin JM, Champoux D, MacEachen E. Health and safety in small workplaces: Refocusing upstream. Can J Public Health. 2010;101(Suppl 1):S29–S33. doi: 10.1007/BF03403843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabiano B, Curro F, Pastorino R. A study of the relationship between occupational injuries and firm size and type in the italian industry. Saf Sci. 2004;42:587–600. [Google Scholar]

- Fenn P, Ashby S. Workplace risk, establishment size and union density. Br J Ind Relat. 2004;42:461–480. [Google Scholar]

- Greiver M, Barnsley J, Glazier RH, Moineddin R, Harvey BJ. Implementation of electronic medical records: Theory-informed qualitative study. Can Fam Physician. 2011;57:e390–e397. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gronroos C. A service perspective on business relationships: The value creation, interaction and marketing interface. Ind Mark Manage. 2011;40:240–247. [Google Scholar]

- Gunningham N, Grabosky P, Sinclair D. Smart regulation. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Haslam C, Haefeli K, Haslam R. Perceptions of occupational injury and illness costs by size of organization. Occup Med. 2010;60:484–490. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqq089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasle P, Limborg HJ. A review of the literature on preventive occupational health and safety activities in small enterprises. Ind Health. 2006;44:6–12. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.44.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasle P, Kines P, Anderson LP. Small enterprise owners’ accident causation attribution and prevention. Saf Sci. 2009;47:9–19. [Google Scholar]

- Hasle P, Bager B, Granerud L. Small enterprises—Accountants as occupational health and safety intermediaries. Saf Sci. 2010;48:404–409. [Google Scholar]

- Hasle P, Kvorning LV, Rasmussen CD, Smith LH, Flyvholm MA. A model for design of tailored working environment intervention programmes for small enterprises. Saf Health Work. 2012;3:181–191. doi: 10.5491/SHAW.2012.3.3.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinze JW, Gambatese JA. Factors that influence the safety performance of specialty contractors. J Constr Eng Manage. 2003;129:159–164. [Google Scholar]

- International Chamber of Commerce. [Accessed May 7, 2013];World chambers network directory. 2013 http://chamberdirectory.worldchambers.com/

- Jeong BY. Occupational deaths and injuries in the construction industry. Appl Ergon. 1998;29:335–360. doi: 10.1016/s0003-6870(97)00077-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina CC, Lavado AC, Cabrera RV. Characteristics of innovative companies: A case study of companies in different sectors. Creativity Innov Manage. 2005;14:272–287. [Google Scholar]

- Mendeloff JM, Nelson C, Ko K, Haviland A. Small businesses and workplace fatality risks. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Miller K. Communication theories. New York: McGraw Hill; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Morse T, Dillon C, Weber J, Warren N, Bruneau H, Fu R. Prevalence and reporting of occupational illness by company size: Population trends and regulartoy implications. Am J Ind Med. 2004;45:361–370. doi: 10.1002/ajim.10354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIOSH. Research compendium: The NIOSH total worker health program: Seminal research papers 2012. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health; 2012. DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2012-146. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen K, Legg S, Hasle P. How to use programme theory to evaluate the effectiveness of schemes designed to improve the work environment in small businesses. Work. 2012;41:5999–6006. doi: 10.3233/WOR-2012-0036-5999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page K. Blood on the coal: The effect of organizational size and differentation on coal mine accidents. J Saf Res. 2009;40:85–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pombo-Romero J, Varela LM, Ricoy CJ. Diffusion of innovations in social interaction systems. An agent-based model for the introduction of new drugs in markets. Eur J Health Econ. 2012;14:443–455. doi: 10.1007/s10198-012-0388-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahikka E, Ulkuniemi P, Pekkarinen S. Developing the value perception of the business customer through service modularity. J Bus Ind Mark. 2011;26:357–367. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovations. 5. New York: Free Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Walker D, Tait R. Health and safety management in small enterprises: An effective low cost approach. Saf Sci. 2004;42:69–83. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson PM, Petticrew M, Calnan MW, Nazareth I. Disseminating research findings: What should researchers do? A systematic scoping review of conceptual frameworks. Implement Sci. 2010;5:91. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood MM, Mileti DS, Kano M, Kelley MM, Regan R, Bourque LB. Communicating actionable risk for terrorism and other hazards. Risk Anal. 2012;32:601–615. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2011.01645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]