Abstract

Purpose

To systematically review experimental evidence for interventions mitigating gender bias in employment. Unconscious endorsement of gender stereotypes can undermine academic medicine's commitment to gender equity.

Method

The authors performed electronic and hand searches for randomized controlled studies since 1973 of interventions that affect gender differences in evaluation of job applicants. Twenty-seven studies met all inclusion criteria. Interventions fell into three categories: application information, applicant features, and rating conditions.

Results

The studies identified gender bias as the difference in ratings or perceptions of men and women with identical qualifications. Studies reaffirmed negative bias against women being evaluated for positions traditionally or predominantly held by men (male sex-typed jobs). The assessments of male and female raters rarely differed. Interventions that provided raters with clear evidence of job-relevant competencies were effective. However, clearly competent women were rated lower than equivalent men for male sex-typed jobs unless evidence of communal qualities was also provided. A commitment to the value of credentials before review of applicants and women's presence at above 25% of the applicant pool eliminated bias against women. Two studies found unconscious resistance to “antibias” training, which could be overcome with distraction or an intervening task. Explicit employment equity policies and an attractive appearance benefited men more than women, whereas repeated employment gaps were more detrimental to men. Masculine-scented perfume favored the hiring of both sexes. Negative bias occurred against women who expressed anger or who were perceived as self-promoting.

Conclusions

High-level evidence exists for strategies to mitigate gender bias in hiring.

The success of female physicians is recognized and celebrated both in popular television series such as “ER,” “Providence,” and “Strong Medicine” and by the National Library of Medicine.1 Despite explicit support for gender equity in academic medicine, however, female physicians advance more slowly toward seniority than do male physicians, earn less than male physicians in similar positions, and have not entered the ranks of leadership at rates predicted by their proportional presence in academic medicine for the past 30 years.2–4

Physicians are committed to evidence-based practice.5 Studies with random assignment of participants to an intervention or control group, in particular, provide high levels of evidence in informing physician decision making.5,6 Decades of social cognitive research exists on how gender stereotypes lead to assumptions—both implicit (unconscious) and explicit (conscious)— that consistently impede women's advancement in historically male-dominant fields.7,8 The success of a job applicant in obtaining a position is a major determinant of that person's ability to advance in any career. To facilitate the adoption of evidence-based employment practices in academic medicine, we performed a systematic review of studies with randomized controlled designs that investigated the impact of an intervention on the activation and application of gender bias in hiring settings.

Method

Study selection

The studies we selected met the following inclusion criteria: random assignment of participants to the intervention or control group, assumption by participants of the role of personnel decision makers evaluating applicants for employment, publication after 1972 (the year that Congress passed the Title IX Amendment1 to the Civil Rights Act), blinding of participants to the intervention, the presence of both men and women in the contrived applicant pool and the participant (rater) groups, and comparison of the impact of an intervention on ratings of male and female applicants with identical qualifications. We excluded studies that assessed bias only by reaction time or accuracy in matching gender-linked stereotypic words or pictures, studies in which the participants were stated to be less than 18 years old, studies with only women in the applicant pool (e.g., pregnant and nonpregnant participants), and studies that did not specifically indicate random assignment of the intervention. We also excluded dissertations, letters, and abstracts. Although searches had no language restriction, all studies identified were in English. When the presence of an inclusion criterion was in doubt, the authors achieved resolution through consensus. This effort usually involved distinguishing between an intervention that had an impact on gender bias and one that simply documented gender bias in a different hiring setting (e.g., jobs supervising men or women9).

Data sources and search strategy

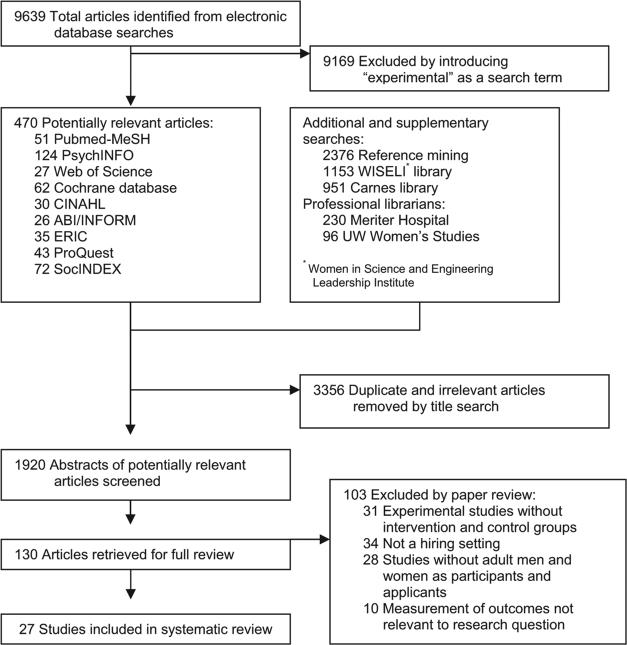

The authors electronically searched the following sites from 1973 (when possible) to June 2008: PubMed, PsychINFO, Web of Science (including Social Science Citation Index), Cochrane Library, CINAHL, ProQuest, ABI/INFORM (U.S. and international articles on business and management), ERIC, and SocINDEX. Terms entered from the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) of the National Library of Medicine were Human, Female, Prejudice, and Stereotype(s). Other terms entered individually or in combination were Gender, Women, Hire/hiring, Bias, Sex roles, Sex, Discrimination, and Research. The authors narrowed database searches using the term Experimental to identify studies with randomized controlled designs. Professional librarians performed supplemental searches of ProQuest, PubMed, and Women's Studies International. Additional reference mining included selected author searches, hand searches of bibliographies of retrieved studies and meta-analyses, and review of files of senior faculty who study gender and leadership. The search was considered saturated when relevant articles reappeared in multiple searches. The authors identified and reviewed abstracts from citations through each of the above searches (N = 1,920) and retrieved and examined articles that seemed to meet inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Because of the heterogeneity in interventions and outcomes, the data were not pooled.

Figure 1.

Search strategy and final selection of studies for inclusion in systematic review. UW, University of Wisconsin; WISELI, Women in Science and Engineering Leadership Institute.

Data extraction

We three authors independently reviewed in detail 130 studies. One of us (B.L.), a statistician, evaluated articles for quality and effectiveness of controls, validity checks on interventions, and appropriateness of statistical tests. We scored articles for quality by using a modified Jadad numerical system of one to four points (a point was allowed for single blinding).10 Inclusion required a score of at least 2. After verification of inclusion criteria, we extracted the following information: author, year, and country in which study was performed; intervention; outcome variables; study design; demographic information on study participants (i.e., gender and race–ethnicity); the construct measured; results; and the P values of statistical procedures.

When an article described more than one experiment, we included only those substudies that met our inclusion criteria. If more than one of the substudies in a given paper met the criteria, we reviewed each one but still counted the citation as one study. Twenty-seven studies met all inclusion criteria. See the Appendix (http://links.lww.com/ACADMED/A1).

The Jadad score was 3 for 4 of the studies11–14 and 2 for the other 23 studies.

Results

Overview of selected studies

Participants in 18 of the 27 studies were college students. Other studies used business (MBA) or graduate students (3 studies and 1 substudy),15–18 managers,12,19,20 adult workers,21,22 and members of human resource associations.14 Twenty-three studies were conducted in the United States: 3 at specified universities,11,13,17 7 in identified regions,12,14,19–21,23,24 and 13 at unspecified locations. Two studies were conducted in the Netherlands25,26 and 2 in Germany.27,28 Participants in all studies were categorized by gender; 11 had descriptors of age (means or ranges),13,14,17,19,21,23,27–31 and 2 provided some description of race and ethnicity.21,23 Whites made up 72% to 90% of participants in these two studies. Studies established applicant gender visually by photograph19,28,29,32–36 or video,13,21,37 designation of sex on the application,18,24 in-person interview,27,37 and/or the use of gendered names and pronouns (modifications of the Goldberg paradigm38).11,12,14–18,22–32,34 Twenty-four studies11–13,15,16,18–30,32,34–37,39 examined gender bias in decision making with regard to applicants for “male sex-typed jobs,” the term applied in much of this research to positions historically or predominantly occupied by men and/or assumed to require stereotypically male traits. Such positions included mechanical engineer,11,24 assistant vice president for financial affairs,18 chair of a district's association of physicians,25,26 sales manager for a heavy-machinery company,12 high-ranking chief executive officer,21 and police officer.22,39 Twelve studies12–14,17,21,24,27,30,33,34,36,39 examined outcomes for female sex-typed jobs (e.g., nurse,39 dental receptionist,12 and day care worker24) or gender-neutral jobs (e.g., copy editor,24 assistant trainee,21 and compensation analyst14). One study13 manipulated the sex-typing of a neutral job (computer lab manager) by emphasizing the requirement of either stereotypic male traits (i.e., technically skilled and able to work under pressure) or stereotypic female traits (i.e., helpfulness and sensitivity to coworkers). Studies confirmed job sex-typing with pretested scales11,22–24,26–29,35 or previous studies12–17,19–22,25,27,28,30–34,36,37 that used, for example, job sex-typing inventories.40–44 Twenty-three studies used ANOVA,11–27,29,30,32–34,36,37 MANOVA,14,16,19,35 or ANCOVA28,36 to compare main effects of the intervention and other independent variables and to test for interactions with gender on the dependent variables of interest. These comparisons were followed by individual comparisons of findings for male and female applicants with previously planned contrasts or appropriate post hoc tests. The remaining study used the chi-square test.31

All but one study24 confirmed that male applicants are evaluated more positively than female applicants for employment in male sex-typed jobs. See the Appendix (http://links.lww.com/ACADMED/A1). It was easier for men than for women with identical qualifications to be recommended for advancement in the job-acquisition process, such as being granted an interview or being hired. Other than in a few comparisons within six studies,11,22,24,28,33,37 male and female participants did not differ in their ratings. Interventions fell into one of three categories (List 1): varying the information provided to raters in the written application (12 studies); changing the behavior, scent, or appearance of the applicant (9 studies); or altering the conditions under which raters assessed applicants (10 studies). Four studies had interventions in two of the categories.13,28,32,33

List 1.

Three categories of interventions on gender bias in hiring settings as found in a review of 27 published reports from 1973 to 2008*

| Information provided to raters in application |

| • Job-relevant individuating information (educational background,16,17,24 past work experience,33 scholasticstanding,24,33 personality,30 performance ability29) |

| • Gender stereotypic, counterstereotypic, or neutral individuating intormation12,13,16,30,33,34 |

| • Parental status17,18,23 |

| • Ambiguous or explicit gender34 |

| • Marital status17 |

| • Life philosophy statements13 |

| • Employment discontinuities14 |

| Applicant behavior, scent, or appearance |

| • Physical attractiveness19,28,32,33,36 |

| • Interview style (self-promoting or self-effacing speech and mannerisms37; direct, self-confident [agentic] interview style13) |

| • Masculine or feminine appearance28 |

| • Masculine, feminine, or no perfume27 |

| • Expression of anger21 |

| Conditions under which raters assessed applicants |

| • Threat of accountability11 |

| • Order of rating separate qualifications and providing summary judgments32 |

| • Priming with counterstereotypic information35 |

| • Proportion of women in the applicant pool15 |

| • Evaluation after counterstereotype training, with or without distraction or filler task25 |

| • Evaluation after counterstereotype training, before or after trait rating task26 |

| • Employment equity directives20,39 |

| • Attentional demand during evaluation28 |

| • Commitment to value of credentials before or after reviewing applicants22 |

The categories were (1) varying the information provided to raters in the application (n = 12), (2) changing the behavior, scent, or appearance of the applicant (n = 9), and (3) altering the conditions under which raters assessed applicants (n = 10).

Information provided to raters in written applications

Six of the 12 studies in this group assessed the impact on bias against female applicants for a male sex-typed job of providing clear evidence of job-related competence (relevant educational or work background,16,17,24,33 high scholastic standing,24,33 job-congruent personality characteristics,30 or designation as a “finalist in the job competition” by “a panel of experts”29). Such individuating information was effective in reducing24,30,33 or eliminating16,17,29 hiring bias. Other studies assessed the impact of matching gender-stereotypic, gender-counterstereotypic, or gender-neutral traits of applicants with job sex-type.12,13,16,30,33,34 For example, Futoran and Wyer34 selected traits shown to be gender-linked on the Bem Sex Role Inventory40 (i.e., aggressive, competitive, industrious, and outgoing for males, and appreciative, considerate, gentle, and helpful for females) to describe male, female, or gender-ambiguous candidates for jobs that normative occupational data studies have shown to be considered to require stereotypic male or female traits. Both an applicant's gender and traits influenced job suitability ratings. Heilman16 found that including positive but job-irrelevant information about female applicants (e.g., having a biology/ political science degree rather than a business/economics degree when applying for a lower management position) resulted in lower ratings than did the absence of such information. Glick and colleagues12 provided individuating information that established gender-counterstereotypic personality traits (e.g., men working in retail sales at a jewelry store and women working in grounds maintenance) but that was job-irrelevant; they found higher employability ratings for both male and female applicants with stereotypic masculine traits, although the preference of raters for a match between job sex-type and applicant gender remained. To measure the degree of gender stereotyping, the participants in the study by Heilman16 assessed applicants by using five adjectival scales associated with gender-related work attributes (e.g., emotional–rational, ambitious–unambitious, tough–soft). Providing a high degree of job-relevant information about a female applicant eliminated the difference in gender stereotyping between male and female applicants seen with low job-relevant information or no information. Furthermore, when composites of these adjectival scores were covaried with applicant ratings, the perceptions of gender-related attributes rather than the applicant's actual gender accounted for assessments of hireability and of potential for advancement. Rudman and Glick13 found that highly competent female applicants benefited from applications that included a written “life philosophy” endorsing communal (stereotypically female) rather than agentic (stereotypically male) values, particularly when they were applying for female sex-typed jobs.

Two studies examined the impact of including information on parental status in the application.18,23 Male and female applicants without children received comparable ratings on all employment-relevant measures. Parenthood resulted in lower ratings for both male and female applicants, but women whose applications indicated that they had children were more disadvantaged. Although both female and male parents were rated as less committed and less dependable than nonparents, only female applicants with children were rated lower on measures of hiring and promotion.18,23 One study included both marital and parental status information in the applications.17 Marital status had little effect on applicant ratings, although married men with children and single women were ranked as the most suitable applicants for two neutral sex-typed positions. One study examined the impact of applications that contained discontinuities in employment and found that men were generally judged more harshly than women in such cases.14

One study compared the effect of gender ambiguity in the application.34 When an applicant's gender was apparent from the application, women were disadvantaged; however, when applicants had gender-ambiguous names (e.g., Pat or Chris), job suitability was based solely on the applicants’ qualifications (even if the inferred gender was female).

Applicant behavior, scent, or appearance

Three studies assessed the impact of interview behavior on gender bias.13,21,37 All found negative reactions to women who exhibited stereotypic male behaviors. Rudman37 found that, when applicants of either gender violated behavioral norms— men by being self-effacing and women by being self-promoting—both were rated lower than applicants who behaved in a more gender-congruent manner. In one of the few differences by participant gender, female raters judged self-promoting women more harshly than did male raters. Rudman and Glick13 found that women who exhibited an agentic interview style were rated lower on social skills than were men, although this difference was eliminated when women's applications included a communal life philosophy statement. Brescoll and Uhlmann21 found that the expression of anger by an applicant enhanced the evaluation of men and lowered the evaluation of women, particularly women applying for a high-status position. The existence of a specific external cause for anger mitigated but did not eliminate the negative bias toward women; external attribution for anger improved the status and salary ratings for women who expressed anger but had no impact on the lower rating of competence.

Sczesny and Stahlberg27 and Sczesny and Kühnen28 found that visual and olfactory cues can activate gender stereotypes independent of the actual biological sex of the applicant. Male and female applicants wearing a masculine-scented perfume or submitting paper applications to which such a scent was applied received more positive ratings than did identically qualified applicants who used a feminine scent.27 This group also found that both men and women who looked more stereotypically masculine in photographs were favored for hiring into a leadership position.28

Five studies examined the impact of physical attractiveness and found that overall attractiveness is advantageous, but more so for men than women.19,28,32,33,36 Highly attractive women can be disadvantaged in applying for male sex-typed jobs, and less attractive women can be disadvantaged in applying for female sex-typed and neutral jobs. Heilman and Saruwatari36 found that attractiveness predicted ratings of stereotypic male or female traits among applicants and that, when these ratings were factored out, the impact of attractiveness was eliminated.

Conditions under which raters assessed applicants

Five studies sought to manipulate automatic gender bias in hiring by informing raters of employment equity directives11,20,39 or by prior training of raters with an exercise to decrease the response time to gender-counterstereotypic word associations.25,26 In response to employment equity directives, Ng and Wiesner39 found that men who were less qualified than women for a female sex-typed job (i.e., nurse) were more likely to be hired, but this positive bias for the underrepresented candidate did not hold true for women who were less qualified than male applicants for a male sex-typed job (i.e., police officer). In the study by Biernat and Fuegen,11 raters with the expectancy of accountability for their hiring decisions were less likely to hire a female applicant. Rosen and Mericle20 found that, even under strong employment equity directives, female applicants were recommended for lower salaries than were men with identical qualifications. Kawakami and colleagues25,26 engaged raters in “antibias” training that successfully reduced response time in matching gender-counterstereotypic words that were displayed sequentially on a computer screen. However, this training did not reduce gender bias in a subsequent mock-hiring situation unless an intervening task or concurrent cognitive distraction prevented subjects from correcting against the perceived coercion of training.25 If participants were able to correct for perceived coercion on an initial task, the preference for male over female job candidates and the attribution of gender-stereotypic traits were eliminated.26

Two studies varied the order in which aspects of the hiring process occurred.22,32 Uhlmann and Cohen22 found that requiring raters to commit to the value of credentials before reviewing any applicants eliminated gender bias in hiring a police chief. Cann et al32 found better correlation between applicant ratings and recommendations to hire when raters were forced to rate applicants’ qualifications separately before, rather than after, providing summary employability judgments.

Heilman15 found that, when women composed 25% or less (i.e., no more than two) of the applicants in a pool of eight, they were viewed as less qualified than male applicants for a managerial job and as being more stereotypically female on gender-related adjectival scales than when women made up at least 37.5% of the pool (three of eight applicants). Covariance analysis of gender-stereotypic and hireability ratings indicated that the impact of gender proportion in the applicant pool could be completely accounted for by the stronger attribution of female gender stereotypes to women when they made up 25% or less of the pool. In a study by Heilman and Martell,35 priming raters with data that women are succeeding in a relevant male-dominated field eliminated bias against female applicants, although priming with information about a single successful woman did not.

Sczesny and Kühnen28 found that rating applicants in the presence of a competing cognitive demand (i.e., memorizing a nine-digit number) enhanced the evaluation of male applicants for leadership competence and certainty of hiring. This effect was most pronounced in female raters.

Discussion

This systematic review reaffirmed the ubiquity of unconscious stereotypes regarding the behaviors and traits associated with being male or female, the ease with which these stereotypes are activated, and the consequent negative bias against women applicants for jobs historically occupied by men. More important, however, this review documents the capability for mitigating the automatic activation and subsequent application of these biases.

Taken together, these studies indicate that, when ambiguity exists in an individual's qualifications or competence, evaluators will fill the void with assumptions drawn from gendered stereotypes. Providing individuating proof of competence and past performance excellence that are relevant to the employment opportunity seems to be effective in mitigating gender bias,16,17,24,29,30,33 provided that raters do not feel coerced,25,26 conditions enable raters to fully attend to the information provided,28 and raters commit to the value of specific credentials both before the review22 and before giving an overall rating.32 Informing raters about research confirming women's competence in sex-typed male tasks is also effective.35

Given the large number of competent women physicians and scientists, this approach would seem to be a fairly straightforward way to ensure gender equity. The studies reviewed also indicate, however, that the issue is more complex than expected. Women who are clearly competent in male sex-typed roles may engender negative reactions37 and lower ratings simply because their competence violates the prescriptive norms for female behavior.31 This outcome seems particularly likely for women who exhibit anger (a “male” emotion45) and for women who use self-promoting, powerful verbal and nonverbal status cues.37 At the same time, men are penalized in evaluations for exhibiting communal or stereotypic female behaviors (e.g., parenthood or self-effacing speech).23,37 Providing evidence that agentic, competent women also behave in gender-congruent communal ways helps mitigate this negative bias13,31,37; however, women must be careful not to seem overly communal by bringing attention to the fact that they are parents or by seeming too feminine in appearance or scent.18,23,27,28 The potential benefit to a woman who is applying for a male sex-typed job of having a gender-ambiguous name34 is worth noting.

Diversity training and employment equity policies would seem logical institutional initiatives to promote gender equity. Evidence from our review suggests, however, that these directives do not ensure gender equity in hiring.20,39 Furthermore, if such directives result in women's presence as a small proportion of an applicant pool, individuating from the stereotypes of the social group that women occupy becomes more difficult, and they may be less likely to be hired.15 Counterstereotype training was effective only under certain circumstances.25,26

This review covered more than 30 years of publications. More recent studies often built on previous work and tended to employ more sophisticated interventions and analyses, but there was no clear diminution of gender bias in the findings between earlier and more recent studies. Several studies did not meet all inclusion criteria but are worth mentioning. Bragger and colleagues46 found that structured interviews with standardized, sequential questions that were relevant to the position eliminated the hiring bias against pregnant applicants found when the same information was obtained through haphazard conversation. Glick and colleagues47 found “sexy” attire was a particular disadvantage, as compared with neutral dress, for women applying for a managerial position. Wiley and Eskilson48 found that applicants with tentative speech patterns, regardless of gender, received lower ratings. The benefit of gender ambiguity was striking in a study comparing employer response to identical resumes with female names or initials.49 Davies and colleagues50 found that affirmation that both men and women are equally capable prevented female-stereotype priming from undermining women's subsequent leadership aspirations. McConnell and Fazio51 found that use of the title “chairman” primed raters to give a position more stereotypic masculine ratings than did the use of “chairperson” or “chair.” Martell52 found that gender bias in rating police officers was eliminated by the reducing time pressure and cognitive distraction during evaluation. Heilman and Okimoto31 confirmed the importance for highly agentic women of providing evidence of communality, to prevent negative ratings. Hugenberg and colleagues53 found less gender bias in selection when raters decided whom to include rather than whom to exclude from a list of individuals in a male sex-typed job.

This study had some limitations. Evidence-based recommendations are limited by the predominant use of college students as participants,54–56 although gender bias in evaluation was also found in the six studies with adult nonstudent participants.12,14,19–22 Furthermore, Marlowe and colleagues19 found gender biases even in the evaluations of experienced managers. The absence of any study in an academic medicine setting is a limitation in the capacity to generalize our findings to academic medicine. We also have little information on the ethnic–racial diversity of the participants, but, given the populations from which these studies drew participants, it is likely that nearly all were white. Finally, although the randomized controlled design of these studies is important for establishing a causal relationship between the intervention and the outcome, the success of these interventions in actual employment settings is unknown.

Conclusions

This review identifies several institutional interventions with a high level of evidence promising the possibility of promoting gender equity in hiring (List 2). The limitations of the studies, in combination with the continual and rapid evolution of social norms, make us reluctant to dictate to individual female applicants behaviors that may enhance their hireability. Whereas we are mindful of these caveats, we also provide recommendations for individual applicants that are supported by the existing research evidence (List 2).

List 2.

Evidence-based recommendations to reduce the application of bias that could disadvantage women applicants in hiring settings*

| Recommendations for Institutions |

| • Design process to allow applicants to provide individuating evidence of job-relevant competency16,17,24,30,33 |

| • Visibly display research evidence that men and women are equivalently successful in male sex-typed roles35,50† |

| • Work hard to ensure that women comprise at least 25% of an applicant pool15 |

| • Insist that raters commit to the value of specific credentials before seeing actual applicants22 |

| • Rate specific qualifications before making summary judgments about applicant32 |

| • Design equity directives and antibias training so that raters do not feel coerced during evaluation11,20,25,26,39 |

| • Do not ask about parenthood status in the application18,23 |

| • Encourage raters to spend adequate time and avoid cognitive distractions during evaluation28,52‡,58§ |

| • Use structured rather than unstructured Interviews46¶ |

| • Do not use man-suffix in job titles (e.g., use “chair” or “chairperson” as opposed to “chairman”)51‡ |

| • Implement training workshops for personnel decision makers that include examples of common hiring biases and group problem solving for overcoming such biases59§,60†† |

| • Encourage raters to use an inclusion rather than an exclusion selection strategy in constructing a final list of applicants53‡ |

| Recommendations for female applicants |

| • Provide some evidence of communal job-relevant behaviors (e.g., being helpful and sensitive to the needs of subordinates)13,18 |

| • Indicate clear evidence of competency (e.g., resume, third-party endorsements) but avoid appearing self-promoting in an interview12,16,29,30,37 |

| • Do not show anger or discuss previous job-related situations that made you angry21 |

| • Best to avoid feminine-scented perfume, but wearing masculine-scented perfume may be beneficial (although you would need to pretest the scent to ensure that it is considered “masculine”)27 |

| • Avoid revealing parenthood status until job and salary are secured18,23 |

| • In your initial application, if you have a female-gendered first name, consider using initials only, and if you have a gender-ambiguous name, consider removing gender-identifying information34,49¶ |

| • Strive for an “attractive” but neutral appearance for interviews or application photographs. Avoid interviewing in overly feminine clothing (more masculine clothing and facial features may be beneficial)28,32,36,47¶,61¶,62†† |

| • If you are visibly pregnant, it might be wise to obscure it with your clothing42¶ |

| • Avoid tentative speech patterns (e.g., use of intensifiers such as “really” and “definitely,” hedges such as “I guess” or “sort of,” and hesitations such as “well” or “let's see”)37,48†† |

All studies cited in this table, except those with superscript symbols, met inclusion criteria for the systematic review. The studies with superscripts are all experimental, controlled studies, but they were excluded from the systematic review for the reasons listed below. We include the citations in this table because the studies support the recommendation.

Self-selection of a leadership role by women.

Intervention involved a personnel evaluation or a selection decision but was not in a hiring setting.

Intervention and assessment of hiring bias, but ratings of applicants not broken down by gender.

No men in the applicant pool.

Intervention appeared to be randomly assigned, but this was not specifically stated.

The National Institutes of Health Roadmap calls for scientists to move beyond the limits of their own discipline and explore new organizational models for interdisciplinary science.57 Evidence-based practice has become a core value of academic medicine.5 With this systematic review, we encourage those within the institution of academic medicine to apply evidence from social science research to the practice of personnel decision making.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the assistance from the following individuals: Sandra Phelps and Heidi Marleau (Ebling Library librarians), Phyllis Holman Weisbard (Women's Studies librarian), and Jennifer Sheridan (Women in Science and Engineering Leadership Institute) at the University of Wisconsin–Madison; and Robert Koehler (chief librarian) at Meriter Hospital.

This research was funded by the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health and Meriter Hospital. Dr. Isaac was supported by grant no. T32 AG00265 from the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Carnes is employed part time by the William S. Middleton Veterans Hospital. This report is GRECC manuscript no. 2000-30.

Appendix

Appendix 1.

Twenty-seven Reports of Randomized Controlled Trials, Published from 1973 to 2008, Assessing the Impact of an Intervention on Gender Bias in the Evaluation of Job Applicants*

| Study, year, reference no. | Intervention | Outcome variable | Study design | Study participants | No. of participants | Construct measured | Results | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biernat and Fuegen, 200111 (Substudy 2) | Presence or absence of requirement to justify hiring decision and sign evaluation form | Gender differences in short-list and hiring selections for applicants with identical resumes | 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 Participant gender (M,F) by accountability (Y/N) by resume set (M,F) by decision (short list, hire) |

College students told to short-list 3 applicants from 14 resumes (7 M, 7 F); then hire 1 of the 3 for mechanical engineering (male sex-typed) position based on recommendation letter | 39 male (M) 25 female (F) |

Effect of accountability expectation on choice of M or F candidate for male sex-typed job | • No difference in short-listing M or F • F applicants more likely to be short-listed than hired • F students less likely to hire a F applicant • No effect of accountability on short listing • Both M and F chose to hire fewer women when held accountable |

NS P < .05 P < .03 NS P < .06 |

| Brescoll and Uhlmann, 200821 | Adults with work-place experience randomly assigned to view a videotaped job interview | Effects of anger (a gender-incongruent emotion) on evaluation of multiple work- related attributes | ||||||

| Substudy 1: Expression of anger or sadness by job applicant in response to losing an account |

Substudy 1: Composite measure of status, recommended salary, competence (1-11); external or internal attribution of emotion |

Substudy 1: 2 × 2 Applicant gender (M,F) by emotion (anger, sadness) |

Substudy 1: 39 M 30 F (85% white) |

Substudy 1: • Status, salary, and competence greater for angry vs sad M • Angry F lowest in status and competence • F anger attributed to internal factors |

P <.05 P <.05 P < .05 |

|||

| Substudy 2: Same as substudy 1 except no emotion rather than sadness for control and high (CEO) and low (assistant trainee) occupational ranks |

Substudy 2: Same as in substudy 1 with measure of being “in control” or “out of control” added |

Substudy 2: 2 × 2 × 2 Applicant gender (M,F) by emotion (anger, no emotion) by occupation (high vs low rank) |

Substudy 2: 70 M 110 F |

Substudy 2: • Status, salary, and competence all lower for angry F regardless of rank • Angry high rank F less competent than all other targets • Anger in F related to internal attribution of being out of control and this fully mediated relationship between anger and status |

P < .05 P < .05 P< .01 |

|||

| Substudy 3: As in substudy 2 but with no information on occupational rank and added statement of external attribution for anger or none |

Substudy 3: Same as in substudy 1 |

Substudy 3: 2 × 3 Applicant gender (M,F) by emotion (unexplained anger, explained anger, no emotion) |

Substudy 3: 51 M 82 F |

Substudy 3: • Higher status and salary for angry M without external attribution vs M with no emotion or external attribution • Higher status and salary but not competence for angry F with vs without external attribution but still lower than F with no emotion • Angry F with external attribution same as angry M in status, salary, and competence |

P < .05 P < .05 NS |

|||

| Cann et al., 198132 | Overall applicant rating or rating of separate qualifications varied in order; applicant physical attractiveness (pre-tested) also varied | Applicant qualifications (1-10), decision to hire (1-6); composite rating of 10 qualifications (each 1-10), self-assessment of applicant attractiveness on decisions | 2 × 3 × 2 × 2 Applicant gender (M,F) by attractiveness (low, medium, high) by order of evaluation by participant gender (M,F) |

College students randomly assigned to review 1 out of 24 job applicant with the order of rating separate qualifications either first or second | 96 M 148 F |

Impact on summary judgments in hiring of forcing raters to attend to specific qualifications first | • No effect of applicant gender or attractiveness on overall ratings, but M and attractive applicants more likely to be hired • Ratings of individual qualifications higher and more strongly correlated with hiring decision when made prior to overall rating • Rating order affected hiring only for average attractive applicants: hiring more likely when overall ratings came first (no gender breakdown) • Raters acknowledged influence of attractiveness |

NS (overall); P < .01 (hiring) |

| P < .01 (qualifications) (P value not given for correlation) | ||||||||

| P < .05 | ||||||||

| P < .0001 | ||||||||

| Dipboye et al., 197733 | Physical attractiveness (pre-tested) and qualifications of applicants varied | Willingness to hire (1–7), salary, and top candidate; rating of traits on adjectival scales | 2 × 3 × 2 × 2 × 3 Rater gender by rater attractiveness (low, moderate, high) by applicant qualifications (low, high) by applicant gender (M,f) by applicant attractiveness (low, moderate, high) |

College students reviewed 12 randomly ordered resumes; Two other college students viewed raters through a one-way mirror and rated their attractiveness | 110 (white; no gender breakdown) | Impact of attractiveness on bias in hiring decisions | • Attractive, high qualified M most likely hired, highest salary, selected as top candidate • M more likely than F to be hired in all conditions except M raters for low-qualified F applicants • Unattractive M rated higher than unattractive F • No difference between moderately attractive M and F • Attractiveness enhanced hiring only for highly qualified applicants • Rater attractiveness had no effect • Adjectival trait differences in M and F applicants aligned with gender stereotypes • No difference in competence or intelligence M vs F • Attractive applicants more favorable than unattractive on all traits except intelligence |

P < .05 |

| P < .05 | ||||||||

|

P < .05 NS | ||||||||

| P < .05 | ||||||||

| NS | ||||||||

|

P < .05 NS | ||||||||

| P < .05 (all traits); NS (intelligence) | ||||||||

| Fuegen et al., 200423 | Parental status of applicant varied | Ratings of applicant competence, job commitment, availability on job, gender ST behaviors; controls rated “ideal” workers | 2 × 2 × 2 Applicant gender (M,F) by parental status (Y/N) by participant gender (M,F) |

Two samples of college students randomly to review resume in 1 of 4 conditions; Midwest sample was 90% white, 3.8% Asian, 2.8% African American, 2.8% Hispanic; Eastern sample was 72.4% white, 8% African American, 4.6% Asian, 13.9% Hispanic, 1.1% West Indian | 49 M 58 F (Midwestern sample); 21 M 66 F (Eastern sample) |

The extent to which parenthood impacts employment standards for men and women | • No difference in competence, performance standards, hiring, promotion for nonparents regardless of gender | NS |

| • Availability: parents < nonparents; F parents < M parents | P < .0001; P < .02 | |||||||

| • Masc stereotype: parents < nonparents • Fern, stereotype: no differences |

P < .02 NS |

|||||||

| • Parents of both genders less committed than nonparents; • M rated F applicant more committed • F rated M applicant more committed |

P < .05 P < .03 P = .06 |

|||||||

| • Hiring and promotion lower for F but not M parent • Required performance standards and time commitment for hire: nonparents same, but F parent held to higher standards and M parent held to lowest standards |

P < .02 NS (nonparents) P < .01 (F vs M parent) |

|||||||

| Futoran and Wyer, 198634 | Gender of applicant was explicit or left ambiguous with a nongendered name (Pat, Chris) | Rating (0-5) of applicant suitability of 9 occupations (3 M sex-typed, 3 F sex-typed, 3 neutral) | 2 × 2 × 2 Applicant gender (M,F) by stereotype traits (masc, fem) by sex-typed job (M,F) 2 × 2 Stereotypic traits (masc, fem) by sex-typed job (M,F) for gender-ambiguous applicant |

College students randomly assigned to 1 of 6 groups: job suitability for M, F, ambiguous applicant when traits match or do not match job type | 134 M 114 F |

Separate contribution of stereotypic gender traits and biological sex to ratings of job suitability | • Inference of gender in ambiguous condition no different for applicants with stereotypic M or stereotypic F traits • Applicant assumed to be the gender of the sex-typed job • When gender was explicit, both gender and traits contributed independently to judgment of job suitability • When gender was inferred, (ambiguous) it was irrelevant and judgment of job suitability was based solely on applicants’ traits |

NS P < .03 |

| P < .05 | ||||||||

| NS | ||||||||

| Glick et al., 198812 | Type of stereotypic or counter-stereotypic gender individuating information (unrelated to job) about applicants varied in otherwise identical resumes | Likelihood of interview for job rated 1-5; Personality trait inferences rated masc or fem 1-5 | 2 × 3 × 3 Applicant gender (M,F) by individuating Information (masc, fem, neut as indicated by summer job, work-study job, extracurricular activities) by job sex-type (masc, fem, neut) |

Upper level managers and business professionals rated 1 of 6 possible resumes, randomly assigned | 205 M 5 F (44% of those mailed surveys) |

Ability of counterstereotypic individuating information to affect gender bias in hiring | • Individuating information matched personality inferences • Applicants with masc traits more likely to be interviewed for all jobs • Counterstereotypic information reduced trait rating bias, but bias favoring a match of job and gender remained |

P < .001 |

| P < .05 | ||||||||

| P < .001 | ||||||||

| Heilman and Saruwatari, 197936 | Physical attractiveness (pre-tested) of applicants for managerial and nonmanagerial jobs varied in otherwise identical resumes | Ratings (1-9) for job qualifications, hiring likelihood, and gender-stereotypic adjectival scales; ranked preferences among applicants; salary | 2 × 2 × 2 Applicant appearance (attractive, unattractive) by applicant gender (M,F) by job type (managerial, nonmanagerial) |

College students randomly assigned to managerial or nonmanagerial condition and evaluated applicants of both genders and levels of attractiveness | 23 M 22 F |

Impact of attractiveness on bias in hiring decisions | • Attractiveness benefited all applicants for all ratings except F applicants for a managerial position (e.g., unattractive F applicants recommended for higher pay than attractive applicants) • Attractive M judged more stereotypically masc and attractive F rated more stereotypically fem • When gender ratings were factored out, impact of attractiveness on all ratings for M and F were eliminated |

P < .05 (P < .10 for salary) |

| P < .001 | ||||||||

| NS | ||||||||

| Heilman, 198015 | Proportion of women in an applicant pool varied | Target F applicant rated 1-9 on qualifications, hiring likelihood, advancement potential, and gender stereotypic adjectival scales | 2 × 5 Rater gender (M,F) by gender pool proportion (Target F + 0, 1, 2, 3, or 7 F) |

MBA students rated target F in pool of 8 applicants for managerial job | 50 M 50 F |

Effect of gender proportion of applicant pool on activation and application of bias in decision-making | • Target F qualifications rated lower when pool had <37.5% females • Likelihood of target F hire greater when pool> 25% female • Potential for target F advancement greater with more F in pool, 12.5% vs 37.5% and 100% • Composite adjectival gender score more fem for target F with pool <37.5% and greatest for 12.5% • Composite adjectival scale completely accounted for all effects of gender pool proportion |

P < .05 |

| P < .05 | ||||||||

| P < .05 | ||||||||

| P < .05 | ||||||||

| P < .05 | ||||||||

| Heilman, 198416 | Information about applicant background varied | Ratings (1-9) for interview, likely success if hired, and potential for advancement; composite gender score from 5 scales of gender-stereotypic adjectival scales | 2 × 3 Applicant gender (M,F) by information type (high job relevance, low job relevance, no information) |

MBA students (blocked by gender) randomly assigned to 1 of 6 conditions: target M or F with each information type for lower management position | 42 M 35 F |

Ability of individuating information to affect gender bias in hiring | • No effect of information type on any job rating or gender score for M target • F target rated lower on all measures with low job-relevant information vs. no information or high job-relevant information • With high job-relevant information, M and F rated same on all measures • Target F rated more stereotypically fem in low job-relevant > no information > high job-relevant information • M = F gender-stereotypic with high job-relevant information • Factoring out gender score removed effect of applicant gender for all measures |

NS |

| P < .01 (for success and interview) | ||||||||

| NS | ||||||||

|

P < .05 NS | ||||||||

| NS | ||||||||

| Heilman and Martell, 198635 | Exposure to a neutral story or story about high-performing women individually or as a group in a field related or unrelated to the job before reviewing applicants | Composite rating of applicant–job match (qualifications, recommend to interview, predicted success in job), salary projection, and gender-related attributes relevant for employment | 2 × 2 × 2 Applicant gender (M,F) by information exposure relevance (Y,N) by competency information (individual F, F as a group), plus neut information control |

College students randomly assigned to 1 of 10 conditions: read article with group or individual competency information about F in a related or unrelated occupation, or nonrelevant information; then evaluated M or F applicant for position | 70 M 77 F |

Effect of priming on applicant evaluation by exposure to relevant counterstereotypic information before hiring decision for F in a male sex-typed job | • M applicants were rated more favorably than F | P < .01 |

| • Gender-stereotypic attributions for M and F applicants differed in neutral information condition | P < .001 | |||||||

| • High- performing related group (but not individual) information improved rating of F applicants and reduced gender stereotyping | P < .05 | |||||||

| Heilman et al., 198829 | Information about applicant's performance ability provided or not | Composite ratings from several scales (1-9) of competence potential and stereotypic gender-related traits | 2 × 2 × 2 Applicant gender (M,F) by job sex-type (extremely M, moderately M) by performance ability (high, unknown) |

College students reviewed work sample of M or F applicant for M sex-type jobs | 60 M 181 F |

Ability of counterstereotypic individuating information to affect gender bias in hiring | • With unknown performance, M rated higher than F for competence and potential for both sex-typed jobs • With high performance, F = M for moderate M sex-typed job and F > M for high M sex-typed job • Stereotypic gender traits lower with high performance information for F: greatest for extreme M sex-typed job |

P < .01 P < .001 |

| P < .01 | ||||||||

| Heilman and Okimoto, 200818 | Effect of parental status on gender bias in employee evaluation | |||||||

| Substudy 1: Information about being a parent or nonparent with children at home provided in application |

Substudy 1: Composite ratings of commitment and anticipated competence, and recommendation for further consideration or not |

Substudy 1: 2 × 2 Applicant gender (M,F) by parental status (no children, children) |

Substudy 1: College students exposed to 4 conditions: 2 F and 2 M targets, one of each a parent |

Substudy 1: 18 M 47 F |

Substudy 1: • F regardless of parental status rated less committed • Parents regardless of gender rated less committed • M without children most committed • F and M without children equally competent and recommended to advance • F with children least committed, least competent, and least likely to be advanced |

P < .001 P < .001 P < .05 NS P < .001 |

||

| Substudy 2: Same as substudy 1 |

Substudy 2: Same as substudy 1 with addition of composite ratings for achievement striving, work dependability, and likelihood of agentic behaviors (e.g., be a leader, seek power) |

Substudy 2: Same as substudy 1 |

Substudy 2: MBA students who were full-time employees (74% with experience in hiring decisions) randomly assigned to evaluate one target application |

Substudy 2: 66 M 34 F |

Substudy 2: • Commitment and competence same as Study 1 (F and M without children comparable; F with children lower than M with children) • Parents also lower on achievement striving and dependability regardless of gender • Likely to engage in agentic behaviors: rated lower for F with vs F without children; ;no effect of children on rating for M • Recommendation to advance: lower for F but not M with children; equal for M and F nonparents |

NS (nonparents); P < .05 (F vs M parents) P < .05 P < .01 (F); NS (M) P < .001 (F); NS (M): NS (nonparents) |

||

| Hodgins and Kalin, 198530 | Type of individuating information about applicants: sex-typed personality descriptors vs no information | Effect of individuating information about applicant on gender and job sex-type match | ||||||

| Substudy 1 and 2: Suitability (1-9) of 3 M & 3 F student resumes for 8 sex-typed jobs |

Substudy 1: 2 × 2 × 2 Rater gender (M,F) by applicant gender (M,F) by job sex-type (M,F) |

College students in mock role of guidance counselor rated resumes of 3 M & 3 F; Raters were scored for explicit gender bias Same as substudy 1 | Substudy 1: 14 M 62 F |

Substudy 1 • Gender of applicant and sex-typed job were congruent; no effect of explicit gender bias Substudy 2 • Individuating information: neut = same as substudy 1; Masc or fem match with job-type more important than resume gender • Raters with greater explicit gender bias showed more bias in job suitability ratings |

P < .01; NS | |||

| Substudy 2: Same as substudy 1 with masc, fem, or neut individuating information added to resumes |

Substudy 2 : 2 × 2 × 2 × 3 Same as substudy 1 by individuating information (masc, fem, neut) |

Substudy 2: 33 M 82 F |

P < .001 | |||||

| P < .005 | ||||||||

| Kawakami et al., 200525 | Counterstereotype training with or without a filler task or distraction task or no training before applicant evaluation | Best candidate for leadership position from 4 applications (2 M, 2 F) | 2 × 4 Applicant gender (M,F) by training and task (No training or task, training only, training plus filler, training plus distraction) |

College students read applications and letters of recommendation and selected best out of 4 under one of four randomly assigned conditions | 19 M 33 F 18 unknown (Nether-lands) |

Ability to manipulate correction processes against “anti-bias” training | • Training did reduce response time for counterstereotypic responses • Hiring favored M over F equivalently for no training and training-only conditions • Hiring bias against F eliminated with training plus filler or training plus distraction |

P < .001 |

| P < 0.01 | ||||||||

| NS (M vs F) | ||||||||

| Kawakami et al., 200726 | Counterstereotype training with applicant evaluation before or after ranking candidates on gender stereotypic traits and instruction to either select the best candidate or the best candidate specifically based on leadership qualities | Best candidate for leadership position from 4 applications (2 M, 2 F) | 2 × 2 × 2 Counterstereotype training (Y/N) by order of job hire task after training (1st or 2nd to trait rating task) by instruction (attend to leadership vs general impression) |

College students randomly assigned to one of 8 conditions rated 4 resumes (2 M & 2 F) for masc or fem traits and job hire in varied order with or without leadership basis | 45 M 111 F (Nether-lands) |

Ability to manipulate correction processes against “anti-bias” training | • Training did reduce response time for counterstereotypic responses • More men chosen in no training or when job hire task immediately followed training • Hiring bias against women eliminated when job hire task 2nd after trait rating task • Trait rating aligned with applicant gender in no training • No effect of training when trait rating 1st; eliminated stereotypic rating when 2nd after job hire task • No effect of instruction to evaluate for leadership traits |

P < .001 |

| P < .05 (M vs F) | ||||||||

| NS (M vs F) | ||||||||

| P < .001 | ||||||||

| NS (1st); P < .01 (2nd) | ||||||||

| NS | ||||||||

| Marlowe et al., 199619 | Physical attractiveness (pre-tested) of applicant varied with identical, well-qualified applicants | Ratings (1-9) of suitability for hire and likelihood of advancement; ranking of applicants | 2 × 2 Applicant gender (M,F) by applicant appearance (highly attractive, marginally attractive) |

Managers in financial institutions assessed for experience evaluated 4 resumes varied for gender and attractiveness | 46 M 66 F |

Impact of applicant attractiveness on gender bias in hiring | • Hire and advancement: highly attractive > marginally attractive; M > F • Managers with low or moderate but not high levels of experience had positive bias for highly attractive M • All managers had negative bias for likelihood of advancement of marginally attractive F • For all levels of experience, highly attractive applicants most likely to be ranked number 1 with no gender difference |

P < .001 (appearrance); P < .02 (M vs F) |

| P < .01 (low and moderate); NS (high) P < .02 | ||||||||

| P < .02 (appearance), NS (M vs F) | ||||||||

| Muchinsky and Harris, 197724 | Scholastic standing and academic major varied for applicants for M, F, and neut sex-typed jobs | Rating (1-20) for hiring | 2 × 2 × 3 × 3 Rater gender (M,F) by applicant gender (M,F), by scholastic standing (low, average, high) by job sex-type (M, F, neutral) |

College students rated 24 applicants in random order (3 packets of 6 experimental + 2 sham resumes grouped by major); explicit bias toward F supervisors measured | 50 M 50 F |

Impact of qualifications on gender bias for sex-typed employment | • M rated F applicants higher for F sex-typed job (day-care center worker); F gave higher ratings to F applicants for M (mechanical engineer) and neutral (copy editor) sex-typed jobs and to M applicants for F sex-typed job | P < .025 |

| • Higher ratings for F applicants applying for M sex-typed job • F applicants with average or low scholastic standing rated higher than M for F sex-typed job • M with average scholastic standing rated higher than F for neutral sex-typed job |

P < .025 | |||||||

| P < .01 | ||||||||

| P < .01 | ||||||||

| Ng and Weisner, 200731 | Presence or absence of employment equity directives | Choice of hire for M or F as 1 of 3 applicants for job as nurse (sex-typed F job) or police officer (sex-typed M job) | 2 × 3 × 2 Job (nurse, police) by qualifications of underrepresented gender (less, equal, more) by equity directive (low or high urgency) |

Classes of college students randomly assigned to one of 6 conditions; students made two hiring decisions each:1 for nurse, 1 for police officer | 191 M 205 F |

Effect of equity directives on gender bias in hiring | • When underrepresented applicants less qualified, more M than F hired • When underrepresented applicants equally or more qualified, hiring for M = that for F • Basic and stronger equity statements increased hiring of less qualified M but not F • Equity directives and provision of employment equity information increased hiring of equally qualified M and F |

P < .05 |

| NS | ||||||||

| P < .05, P < .001 | ||||||||

| P < .05 | ||||||||

| Renwick and Tosi, 197817 | Marital status and job-relevant educational background varied | Suitability (1–7) for each of two positions; most and least suitable | 5 × 2 × 2 × 2 × 5 Undergraduate major (5 choices) by graduate degree (MBA, MS) by job (traveling, home office) by applicant gender (M,F) by marital status (married, single, divorced, married with 2 children, divorced with 2 children) |

Graduate students in Administration randomly assigned to review 10 resumes for 2 job descriptions | 64 M 16 F (39% single, 54% married, and 7% divorced; 39% parents) |

Effect of job-relevant education and marital status on gender bias in hiring | • No gender differences for any measures or choice of most suitable candidate • Applicants more suitable with relevant majors or MBA • Most suitable job applicant = married M with 2 children with business major and MBA vs. least desirable = divorced M with history major and MS • Most suitable F applicant = single, industrial sociology major and MBA vs least suitable F = single history major with MA • No difference in most and least suitable M and F |

NS |

| P < .05 | ||||||||

| P < .01 | ||||||||

| P < .01 | ||||||||

| NS | ||||||||

| Rosen and Mericle, 197920 | Presence of weak or strong employee equity directives (including expectation of accountability) | Hiring recommendation (14), salary | 2 × 2 Applicant gender (M,F) by equity directive (weak, strong) |

Municipal administrators in managerial positions randomly assigned to review one applicant | 57 M 11 F |

Effect of equity directives on gender bias in hiring | • No gender difference in hiring recommendations for weak or strong equity policy • Lower salary recommended for F applicants with strong equity directives |

NS |

| P < .025 | ||||||||

| Rudman, 199837 (Substudies 2 and 3) | Ratings of task aptitude, social attraction and hireability; composite social desirability scale; self-promotion index; gender typicality scale | Impact of self-promoting or self-effacing behavior on evaluation of applicants | ||||||

| Substudy 2: Applicant responded in interview with either self-promoting or self-effacing verbal and nonverbal style, and raters were instructed to pick best applicant for project success (accuracy) and best score on game to be played together (outcome) |

Substudy 2: 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 Rater gender (M,F) by task goal (accuracy, outcome) by applicant gender (M,F) by style (self-promoting, self-effacing) |

Substudy 2: College students randomly assigned to view videotaped “practice job interview” under conditions of accuracy or outcome |

Substudy 2: 82 M 81 F |

Substudy 2: • Task aptitude and hireability: self-promoters of both genders> self-effacers for accuracy goal • Self-effacing M > F and self-promoting M = F for outcome goal • Social attraction: M raters gave F self-effacers higher scores for accuracy goal and F self-promoters higher ratings for outcome goal • F raters gave F self-effacers higher ratings in both goal conditions • F raters and raters with outcome goal preferred self-promoting M but no difference for M raters or raters with accuracy goal • Self-promoting M more likable and hireable than the self-promoting F • Self-promoting M more likable and hireable than the self-effacing M • Self-effacing M more likeable than self-promoting F but latter was more hireable • Self-effacing M = F for hireability |

P < .001 | |||

| P < .04 (effacers), NS (promoters) | ||||||||

| P < .01 | ||||||||

| P < .001 | ||||||||

| P < .01 (F raters, outcome goal); NS (M raters, accuracy goal) | ||||||||

| P < .05 | ||||||||

| P < .05 | ||||||||

| P < .05 | ||||||||

| NS | ||||||||

| Substudy 3: Similar to substudy 2 but all F applicants were self-promoting (M were either self-promoting or self-effacing) and outcome goal was the only condition |

Substudy 3: 2 × 2 × 2 Male applicant style (self-promoting, self-effacing) by rater gender (M, F) by target gender (M,F) |

Substudy 3: Same as substudy 2 except all rated for outcome condition and interview was in person rather than video |

Substudy 3: 19 M 21 F |

Substudy 3: • Task aptitude and hireability: F but not M raters gave self-promoting M higher scores than self-promoting F • Self-effacing M lower than self-promoting F • Social attraction: F but not M raters preferred M over F applicants; no effect of style • Partner selection: self-effacing F over self-effacing M; self-promoting M > self-promoting F (for F raters only) |

P < .05 (F raters); NS (M raters) | |||

| P < .001 | ||||||||

|

P < .05 (M vs F); NS (style) P < .01 | ||||||||

| Rudman and Glick, 200113 | Applicant's agentic (e.g. “my goal is to be a winner”) or “androgenous” I (e.g. “life is about being connected to other people”) life philosophy statement read before viewing and rating highly agentic applicant | Composite scores of competence, social skills, and hireability | 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 Applicant gender (M,F) by applicant attributes (agentic, androgynous) by job sex-typed (M,F) by rater gender (M,F) |

College students viewed videotaped interview of highly agentic applicant (responses in direct, self-confident manner); implicit bias and explicit gender bias assessed | 67 M 105 F |

Potential for backlash against agentic women applying for F sex-typed jobs | • Competence: agentic > androgynous regardless of gender | P < .01 |

| • Social skills: agentic M > F; androgynous M = F | P = .05; NS | |||||||

| • Hireability: androgynous M and F comparable; agentic M and F comparable for M sex-typed job but agentic F less hireable than M for F sex-typed job | NS (androgynous); NS (M sex-typed); P < .05 (F sex-typed) | |||||||

| • Raters with greater implicit (but not explicit) bias rated agentic F lower on social skills for F sex-typed job and rated agentic M as more hireable for M sex-typed job | P < .05 | |||||||

| Sczesny and Stahlberg, 200227 | Ability of olfactory cues to activate gender bias in hiring | |||||||

| Substudy 1: Pre-tested masc, fem, or no perfume applied to applications before rating |

Substudy 1: Decision to hire (Y/N), certainty of decision (1-5), scent detected (Y/N) and how pleasant (1 -5) |

Substudy 1: 3 × 2 Scent (masc, fem, none) by applicant gender (M,F) |

Substudy 1: College students acting as personnel managers randomly assigned to review one applicant |

Substudy 1: 37 M 37 F |

Substudy 1: • M and F applicants with masc scent hired with greater certainty than those with fem scent • No perfume most likely to be hired |

P = .003 | ||

| P = .001 | ||||||||

| Substudy 2: Same as substudy 1 but perfume on person rather than paper application |

Substudy 2: Same as substudy 1 |

Substudy 2: 3 × 2 × 2 Scent (M,F, none) by applicant gender (M,F) by rater gender (M,F) |

Substudy 2: College students randomly assigned to conduct a job interview for leadership position with scripted confederate |

Substudy 2: 57 M 59 F |

Substudy 2: • M and F applicants with masc scent hired with greater certainty than those with fem or no perfume • Fem scent no different than no scent |

P < .05 | ||

| NS | ||||||||

| Sczesny and Kühnen, 200428 | Rating of applicant with masc or fem appearance with or without concurrent attentional demand | Leadership competence on 10 items; certainty of decision to hire or not | 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 Physical appearance (fem, masc) by applicant gender (M,F) by attentional demand (Y/N) by rater gender (M,F) (attractiveness and likeability as covariates) |

College students randomly assigned to evaluate leadership competence of 1/12 applicants (3 per condition) | 72 M 72 F |

Separate effects of gendered physical appearance and biological sex on attribution of leadership competence and hiring | • Leadership competence higher for M & F applicants rated attractive • Without distraction: leadership competence greater for F; F (but not M) raters more certain to hire F • With distraction: M = F for leadership competence; F (but not M) raters more certain in hiring M • Higher leadership competence for masc vs fem appearance (regardless of distraction or applicant gender) |

P < .01 |

| P < .05 (competence); P < .01 (hiring) | ||||||||

| NS (competence); P < .01 (hiring) | ||||||||

| P < .001 | ||||||||

| Smith et al., 200514 | Presence or absence of employment discontinuities on resumes of prospective applicants | Recommend to interview (1–7) and further consideration (1–7); starting salary; summary scores for motivation and commitment; coded written commentary | 2 × 3 Applicant gender (M,F) by employment gap (none, single 9 months; three 12 weeks) by |

143 respondents out of 400 randomly selected members of human resource associations who were mailed one resume to review | 54% F | Gender differences in the impact of discontinuous employment on hiring | • No gap in employment: M > F salary; M = F for interview and consideration. | P < .01 (salary); NS (interview and consideration) |

| • Single gap: M = F | NS | |||||||

| • Multiple gaps: M = F salary; M < F for interview and consideration | NS (salary); P < .01 (interview); P < .001 (consideration) | |||||||

| • F rated more committed in all conditions • M applicants with multiple gaps rated least committed • M = F on motivation |

P < .01 P < .01 NS |

|||||||

| • Content coding: M judged more harshly than F for discontinuous employment | Qualitative | |||||||

| Uhlman and Cohen, 2005 (Study 3)22 | Presence or absence of commitment to value of applicant qualifications before assessment of applicant | Ratings (1-11) of strength of streetwise or educated characteristics of applicant and importance of characteristic to success as police chief | 2 × 2 × 2 Rater gender (M,F) by applicant gender (M,F) by prior commitment (Y/N) |

Visitors to local beach and town fair randomly assigned to evaluate either a M or F candidate for police chief | 63 M 51 F 3 unknown |

Tendency to revise the value of applicant qualifications to justify hire in way that appears to be without gender bias | • M and F applicants rated as similarly streetwise and educated • No-commitment group rated education less important when applicant was M • No-commitment M (but not F) raters favored M applicant • Prior commitment eliminated gender discrimination |

NS |

| P = .04 | ||||||||

| P = .009 | ||||||||

| NS |

M, male; F, female; masc, masculine; fem, feminine; neut, neutral; MBA, Master in Business Administration.

Footnotes

Supplement digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text; simply type the URL address into any Web browser to access this content. Clickable links to this material are provided in the HTML text and PDF of this article on the journal's Web site (www.academicmedicine.org).

Contributor Information

Dr. Carol Isaac, Center for Women's Health Research, and lecturer, Department of Orthopedics and Rehabilitation, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, Wisconsin..

Dr. Barbara Lee, Tarpon Springs, Florida..

Dr. Molly Carnes, Center for Women's Health Research, University of Wisconsin–Madison and Meriter Hospital, Madison, Wisconsin; professor, Departments of Medicine and Psychiatry, School of Medicine and Public Health; professor, Department of Industrial & Systems Engineering, and codirector, Women in Science and Engineering Leadership Institute (WISELI), College of Engineering, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, Wisconsin; and director, Women Veterans Health Program, William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital, Madison, Wisconsin..

References

- 1.National Institutes of Health [June 29, 2008];Changing the Face of Medicine Web site. Available at: ( http://www.nlm.nih.gov/changingthefaceofmedicine).

- 2.Wright AL, Schwindt LA, Bassford TL, et al. Gender differences in academic advancement: Patterns, causes, and potential solutions in one US college of medicine. Acad Med. 2003;78:500–508. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200305000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carnes M, Morrissey C, Geller S. Women's health and women in academic medicine: Hitting the same glass ceiling? J Womens Health. 2008;17:1453–1462. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ash AS, Carr PL, Goldstein R, Friedman RH. Compensation and advancement of women in academic medicine: Is there equity? Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:205–212. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-3-200408030-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strauss SE, Richardson WS, Glaziou P, Haynes RB. Evidence-based Medicine: How to Practice and Teach EBM. 3rd ed. Churchill Livingstone; Edinburgh, UK: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 6. [July 1, 2008];Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine—Levels of Evidence. 2009 Mar; Available at: ( http://www.cebm.net/levels_of_evidence.asp).

- 7.Valian V. The Advancement of Women. MIT Press; Cambridge, Mass: 1998. Why So Slow? [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ridgeway C. Gender, status, and leadership. J Soc Issues. 2001;57:637–655. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rose GL, Andiappan P. Sex effects on managerial hiring decisions. Acad Manage J. 1978;21:104–112. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: Is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Biernat M, Fuegen K. Shifting standards and the evaluation of competence: Complexity in gender-based judgment and decision making. J Soc Issues. 2001;57:707–724. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glick P, Zion C, Nelson C. What mediates sex discrimination in hiring decisions? J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;55:178–186. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rudman LA, Glick P. Prescriptive gender stereotypes and backlash toward agentic women. J Soc Issues. 2001;57:743–762. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith FL, Tabak F, Showail S, Parks JM, Kleist JS. The name game: Employability evaluations of prototypical applicants with stereotypical feminine and masculine first names. Sex Roles. 2005;52:63–82. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heilman ME. The impact of situational factors on personnel decisions concerning women: Varying the sex composition of the applicant pool. Organ Behav Hum Perf. 1980;26:386–395. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heilman ME. Information as a deterrent against sex discrimination: The effects of applicant sex and information type on preliminary employment decisions. Organ Behav Hum Perf. 1984;33:174–186. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Renwick PA, Tosi H. The effects of sex, marital status, and educational background on selection decisions. Acad Manage J. 1978;21:93–103. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heilman ME, Okimoto TG. Motherhood: A potential source of bias in employment decisions. J Appl Psychol. 2008;93:189–198. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.93.1.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marlowe CM, Schneider SL, Nelson CE. Gender and attractiveness biases in hiring decisions: Are more experienced managers less biased? J Appl Psychol. 1996;81:11–21. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosen B, Mericle MF. Influence of strong versus weak fair employment policies and applicant's sex on selection decisions and salary recommendations in a management simulation. J Appl Psychol. 1979;64:435–439. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brescoll VL, Uhlmann EL. Can an angry woman get ahead? Status conferral, gender, and expression of emotion in the workplace. Psychol Sci. 2008;19:268–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uhlmann EL, Cohen GL. Constructed criteria: Redefining merit to justify discrimination. Psychol Sci. 2005;16:474–480. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2005.01559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fuegen K, Biernat M, Haines E, Deaux K. Mothers and fathers in the workplace: How gender and parental status influence judgments of job-related competence. J Soc Issues. 2004;60:737–754. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muchinsky PM, Harris SL. The effect of applicant sex and scholastic standing on the evaluation of job applicant resumes in sex-typed occupations. J Vocat Behav. 1977;11:95–108. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kawakami K, Dovidio JF, van Kamp S. Kicking the habit: Effects of nonstereotypic association training and correction processes on hiring decisions. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2005;41:68–75. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kawakami K, Dovidio JF, van Kamp S. The impact of counterstereotypic training and related correction processes on the application of stereotypes. Group Processes Intergroup Relat. 2007;10:139–156. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sczesny S, Stahlberg D. The influence of gender-stereotyped perfumes on leadership attribution. Eur J Soc Psychol. 2002;32:815–828. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sczesny S, Kühnen U. Meta-cognition about biological sex and gender-stereotypic physical appearance: Consequences for the assessment of leadership competence. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2004;30:13–21. doi: 10.1177/0146167203258831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heilman ME, Martell RF, Simon MC. The vagaries of sex bias: Conditions regulating the undervaluation, equivaluation, and overvaluation of female job applicants. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1988;41:98–110. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hodgins DC, Kalin R. Reducing sex bias in judgements of occupational suitability by the provision of sextyped personality information. Can J Behav Sci. 1985;17:346–358. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heilman ME, Okimoto TG. Why are women penalized for success at male tasks? The implied communality deficit. J Appl Psychol. 2007;92:81–92. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.92.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cann A, Siegfried WD, Pearce L. Forced attention to specific applicant qualifications: Impact on physical attractiveness and sex of applicant biases. Personnel Psychol. 1981;34:65–75. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dipboye RL, Arvey RD, Terpstra DE. Sex and physical attractiveness of raters and applicants as determinants of resume evaluations. J Appl Psychol. 1977;62:288–294. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Futoran GC, Wyer RS. The effects of traits and gender stereotypes on occupational suitability judgments and the recall of judgment-relevant information. J Exp Soc Psychol. 1986;22:475–503. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heilman ME, Martell RF. Exposure to successful women: Antidote to sex discrimination in applicant screening decisions? Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1986;37:376–390. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heilman ME, Saruwatari LR. When beauty is beastly: The effects of appearance and sex on evaluations of job applicants for managerial and nonmanagerial jobs. Organ Behav Hum Perform. 1979;23:360–372. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rudman LA. Self-promotion as a risk factor for women: The costs and benefits of counterstereotypical impression management. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1998;74:629–645. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.3.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goldberg P. Are women prejudiced against women? Transaction. 1968;5:316–322. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ng ES, Wiesner WH. Are men always picked over women? The effects of employment equity directives on selection decisions. J Bus Ethics. 2007;76:177–187. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bem S. The measurement of psychological androgeny. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1974;42:155–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gottfredson LS. Circumscription and compromise: A developmental theory of occupational aspirations. J Couns Psychol. 1981;28:545–579. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schein VE. A global look at psychological barriers to women's progress in management. J Soc Issues. 2001;57:675–688. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Broverman IK. Sex-role stereotypes: A current appraisal. J Soc Issues. 1972;28:59–78. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schein VE. Relationships between sex role stereotypes and requisite management characteristics among female managers. J Appl Psychol. 1975;60:340–344. doi: 10.1037/h0076637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Plant EA, Hyde JS, Keltner D, Devine PG. The gender stereotyping of emotions. Psychol Women Q. 2000;24:81–92. [Google Scholar]