Abstract

Purpose

To examine the significance of the proposed International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society (IASLC/ATS/ERS) histologic subtypes of lung adenocarcinoma for patterns of recurrence and, among patients who recur following resection of stage I lung adenocarcinoma, for postrecurrence survival (PRS).

Patients and Methods

We reviewed patients with stage I lung adenocarcinoma who had undergone complete surgical resection from 1999 to 2009 (N = 1,120). Tumors were subtyped by using the IASLC/ATS/ERS classification. The effects of the dominant subtype on recurrence and, among patients who recurred, on PRS were investigated.

Results

Of 1,120 patients identified, 188 had recurrent disease, 103 of whom died as a result of lung cancer. Among patients who recurred, 2-year PRS was 45%, and median PRS was 26.1 months. Compared with patients with nonsolid tumors, patients with solid predominant tumors had earlier (P = .007), more extrathoracic (P < .001), and more multisite (P = .011) recurrences. Multivariable analysis of primary tumor factors revealed that, among patients who recurred, solid predominant histologic pattern in the primary tumor (hazard ratio [HR], 1.76; P = .016), age older than 65 years (HR, 1.63; P = .01), and sublobar resection (HR, 1.6; P = .01) were significantly associated with worse PRS. Presence of extrathoracic metastasis (HR, 1.76; P = .013) and age older than 65 years at the time of recurrence (HR, 1.7; P = .014) were also significantly associated with worse PRS.

Conclusion

In patients with stage I primary lung adenocarcinoma, solid predominant subtype is an independent predictor of early recurrence and, among those patients who recur, of worse PRS. Our findings provide a rationale for investigating adjuvant therapy and identify novel therapeutic targets for patients with solid predominant lung adenocarcinoma.

INTRODUCTION

Despite curative-intent surgical resection, tumor recurrence and spread remain the primary causes of cancer-related death among patients with early-stage lung cancer.1 Among patients with stage I lung adenocarcinoma—the most common histologic subtype of lung cancer—outcomes after surgical resection vary. The current staging system fails to distinguish patients at a higher risk of recurrence following surgical resection.2 With the results of the National Lung Screening Trial and the recent approval of Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Service coverage for screening computed tomography (CT) scans, an increase in the detection and treatment of early-stage lung cancer is expected.3–5 This underscores the need for better prognostic factors to identify patients at risk of early recurrence after curative-intent surgical resection and those who have a high risk of death after recurrence.

The new International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society (IASLC/ATS/ERS) classification characterizes lung adenocarcinoma as a heterogeneous mixture of histologic subtypes, with the predominant histologic subtype able to stratify recurrence-free survival.6–8 To date, few studies have investigated the prognostic utility of this classification with respect to recurrence patterns and postrecurrence survival (PRS).9 Several researchers have investigated the effects of clinicopathologic factors on PRS among patients with lung cancer (Appendix Table A1, online only).9–14 However, the cohorts in these studies were heterogeneous with respect to histologic profile (adenocarcinoma or nonadenocarcinoma) and/or TNM stage (early or advanced). In this study, we examined the prognostic significance of histologic subtypes and clinicopathologic factors in a large, homogeneous cohort of patients with stage I lung adenocarcinoma treated at a single institution during a 10-year period. In addition, by focusing on patients who recurred following initial surgical resection, we were able to investigate the effects of both primary tumor factors and postrecurrence factors on PRS.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patient Cohort

This retrospective study was approved by the institutional review board at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC). We reviewed the medical records of all patients diagnosed with pathologic stage I solitary lung adenocarcinoma who had undergone surgical resection at MSKCC between January 1999 and December 2009. Our inclusion criterion was a diagnosis of lung adenocarcinoma, with hematoxylin and eosin–stained slides available for pathologic review. Our exclusion criteria were that the patient must have had multicentric, metachronous, or metastatic disease, undergone lung cancer surgery within the last 2 years, undergone incomplete resection (R1 or R2), or received induction therapy. Correlative clinical data were retrieved from our prospectively maintained Thoracic Surgery Service Lung Cancer Database. Analysis for recurrence was performed on all eligible patients who underwent resection, and analysis for PRS was performed on all patients who experienced recurrence.

Histologic Evaluation

All available hematoxylin and eosin–stained tumor slides (mean, five slides per patient; range, one to 12 slides per patient) were reviewed by two pathologists who were blinded to patient clinical outcomes (K.K. and W.D.T.); an Olympus BX51 microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) with a standard 22-mm diameter eyepiece was used. Any discrepancies between the pathologists during determination of predominant subtypes were resolved via consensus by using a multiple-headed microscope. The percentage of each histologic pattern was recorded in 5% increments. Tumors were classified according to the IASLC/ATS/ERS classification as adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS), minimally invasive adenocarcinoma (MIA), and invasive adenocarcinoma, which was subdivided into lepidic predominant (LEP), acinar predominant (ACI), papillary predominant (PAP), micropapillary predominant (MIP), solid predominant (SOL), colloid predominant (COL), and invasive mucinous (MUC) adenocarcinoma.15 Tumors were grouped by architectural grading as low (AIS, MIA, or LEP), intermediate (PAP or ACI), or high (MIP, SOL, COL, or MUC).6,7 The following factors were also investigated: visceral pleural invasion, lymphatic and vascular invasion, and the presence of necrosis. Lymphatic invasion was defined as the presence of tumor cells within endothelium-lined lymphatic spaces. Vascular invasion was defined as the presence of tumor cells within blood vessels.6–8

Surveillance Protocol

Postoperative lung cancer surveillance was performed in accordance with National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines.16 During the first 2 years after surgery, each patient received a physical examination, interval history, and chest/upper-abdominal CT scan with or without contrast every 6 to 12 months. Bronchoscopy, serum markers, and positron emission tomography (PET) scans were not used during routine follow-up. Follow-up visits and surveillance CT scans were performed yearly after the first 2 years. At each follow-up visit, all new studies were reviewed by the clinician. Patients were monitored either by their thoracic surgeon or by a nurse practitioner trained in thoracic survivorship care.

The study had two primary end points: recurrence after initial resection with curative intent (evaluated in all patients) and death after development of recurrence (evaluated in patients who experienced recurrence only). The data extracted included type of recurrence (distant, regional, or local), method of detection, and whether the event was detected at a scheduled clinic visit as part of routine surveillance or at an unscheduled visit outside the follow-up protocol.17,18 Recurrences were defined as in our previous publication19: local recurrence was defined as any new lesion adjacent to a staple line or the bronchial stump or in the residual lobe (in cases of sublobar resection). Regional recurrence was defined as evidence of a tumor in a second ipsilateral lobe, in the ipsilateral hilar lymph nodes (N1), or in the ipsilateral mediastinal lymph nodes (N2). Distant recurrence was defined as evidence of a tumor in the contralateral lung, in the contralateral mediastinal or ipsilateral supraclavicular lymph nodes (N3), or elsewhere outside the hemithorax.19 Diagnosis of recurrence was confirmed via biopsy, and imaging (ie, PET scan or brain magnetic resonance imaging) was performed to support the clinical diagnosis and the decision to initiate treatment. In cases in which a new tumor developed in the lung or pleura and a biopsy specimen was available, the histologic profile was reviewed to determine whether the new tumor was a metachronous primary tumor or a recurrence or metastasis, in accordance with the method developed by our group.20 A combined recurrence was defined as the detection of both locoregional and distant metastasis, either simultaneously or within 30 days of each other.21

Statistical Analysis

The risk of recurrence was evaluated among all patients included in the study by using competing risks methods, which account for deaths in the absence of a documented recurrence as competing events. The cumulative incidence function was used to estimate the cumulative incidence of recurrence (CIR) after surgical resection with curative intent.22 Patients who did not experience recurrence or die during the study period were censored at the time of the last available follow-up. Differences in CIR between groups were assessed by using the Gray method23 (for univariable nonparametric analyses) and the Gray and Fine24 model (for multivariable analyses). Overall survival (OS) from time of surgery was estimated by using the Kaplan and Meier method and was compared across groups by using the log-rank test.

For patients who experienced recurrence, PRS was estimated by using the Kaplan-Meier method. Patients were monitored from the time of cancer recurrence until the time of death as a result of any cause. Patients who were alive at the end of the study were censored at the last available follow-up. Differences in PRS between groups were evaluated by using the log-rank test (for univariable analysis) and Cox proportional hazards model (for multivariable analysis). For architectural grade analysis, the low and intermediate grades were combined because there were few events being observed among patients with low-grade disease, and the effect of high-grade disease was evaluated separately for predominant micropapillary and predominant solid subtypes. Hazard rates were estimated by using the kernel-smoothing method.25,26 Statistical analyses were performed by using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R version 2.14.1. All significance tests were two-sided, and 5% was set as the level of statistical significance.

RESULTS

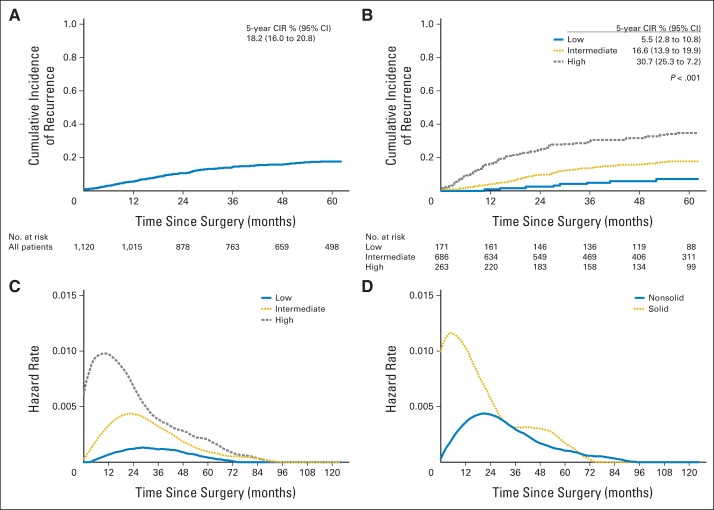

The study cohort consisted of 1,120 patients with resected stage I lung adenocarcinoma. Median follow-up was 60 months (range, 0.3 to 178 months); median age was 69 years (range, 23 to 96 years). Of the 1,120 patients identified, 188 (17%) experienced recurrence. At the end of the study period, 308 patients had died. The 5-year CIR for all patients was 18.2% (95% CI, 16% to 20.8%; Fig 1A). On univariable analysis, male sex (P = .038), sublobar resection (P < .001), lymphatic invasion (P < .001), vascular invasion (P < .001), pleural invasion (P < .001), stage IB disease (P < .001), and high architectural grade (P < .001; Fig 1B) were correlated with a higher risk of recurrence (Table 1). Of patients with stage IB disease (n = 273), 24 (10%) received adjuvant chemotherapy. In this small cohort of patients, adjuvant chemotherapy did not have any significant effect on risk of recurrence in the adjuvant chemotherapy group (5-year CIR, 21.5% [95% CI, 8.7% to 53.4%]) compared with the nonadjuvant chemotherapy group (5-year CIR, 29.6% [95% CI, 24.1% to 36.4%]; P = .15).

Fig 1.

(A) Cumulative incidence of recurrence (CIR) of patients with stage I lung adenocarcinoma. (B) CIR for patients with stage I lung adenocarcinoma for each architectural grade. (C) Hazard function of recurrence for architectural grade tumors. (D) Hazard function of recurrence for solid predominant tumors.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics and Univariable Analyses of Recurrence

| Characteristic | No. (%) | 5-Year CIR (95% CI), % | P* |

|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | 1,120 | 18.2 (16.0 to 20.8) | |

| Age, years | .45 | ||

| ≤ 65 | 404 (36) | 20.2 (16.4 to 24.9) | |

| > 65 | 716 (64) | 17.1 (14.4 to 20.3) | |

| Sex | .038 | ||

| Female | 696 (62) | 16.5 (13.7 to 19.7) | |

| Male | 434 (39) | 21.1 (17.4 to 25.7) | |

| Smoking history | .243 | ||

| Never | 197 (18) | 16.0 (11.3 to 22.6) | |

| Ever | 923 (82) | 18.7 (16.2 to 21.6) | |

| Surgical procedure† | < .001 | ||

| Lobectomy | 807 (72) | 15.5 (13.0 to 18.4) | |

| Sublobar resection | 313 (28) | 25.1 (20.5 to 30.7) | |

| T factor | < .001 | ||

| T1a | 632 (56) | 14.0 (11.4 to 17.2) | |

| T1b | 215 (19) | 17.2 (12.5 to 23.8) | |

| T2a | 273 (24) | 29.0 (23.7 to 35.5) | |

| Pathologic stage | < .001 | ||

| IA | 847 (76) | 14.8 (12.5 to 17.6) | |

| IB | 273 (24) | 29.0 (23.7 to 35.5) | |

| Predominant histologic subtype | < .001 | ||

| Adenocarcinoma in situ | 2 (0.2) | NA | |

| Minimally invasive adenocarcinoma | 32 (3) | 0 | |

| Lepidic | 137 (12) | 6.8 (3.5 to 13.4) | |

| Acinar | 453 (40) | 16.6 (13.3 to 20.7) | |

| Papillary | 244 (22) | 16.6 (12.2 to 22.7) | |

| Micropapillary | 68 (6) | 40.9 (29.9 to 56.0) | |

| Solid | 146 (13) | 29.1 (22.3 to 37.9) | |

| Invasive mucinous | 40 (4) | 19.8 (10.1 to 39.1) | |

| Colloid | 9 (0.8) | NA | |

| Architectural grade | < .001 | ||

| Low | 171 (15) | 5.5 (2.8 to 10.8) | |

| Intermediate | 686 (61) | 16.6 (13.9 to 19.9) | |

| High | 263 (23) | 30.7 (25.3 to 37.2) | |

| Lymphatic invasion | < .001 | ||

| Absent | 751 (67) | 11.6 (9.4 to 14.4) | |

| Present | 369 (33) | 31.6 (27.0 to 37.0) | |

| Vascular invasion | < .001 | ||

| Absent | 862 (77) | 13.5 (11.2 to 16.2) | |

| Present | 258 (23) | 33.8 (28.2 to 40.5) | |

| Pleural invasion | < .001 | ||

| Absent | 966 (86) | 16.2 (13.9 to 18.9) | |

| Present | 154 (14) | 30.9 (24.0 to 39.8) | |

| Mutation | .11 | ||

| Wild | 326 (29) | 20.6 (16.3 to 26.0) | |

| EGFR | 96 (9) | 12.8 (6.6 to 24.8) | |

| KRAS | 133 (12) | 16.2 (10.4 to 25.0) | |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy (stage IB) | |||

| No | 249 (90) | 29.6 (24.1 to 36.4) | .15 |

| Yes | 24 (10) | 21.5 (8.7 to 53.4) |

Abbreviations: CIR, cumulative incidence of recurrence; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; NA, not applicable.

Significant P values (< .05) are shown in bold type.

Lobectomy: pneumonectomy, bilobectomy, or lobectomy; sublobar resection: segmentectomy or wedge resection.

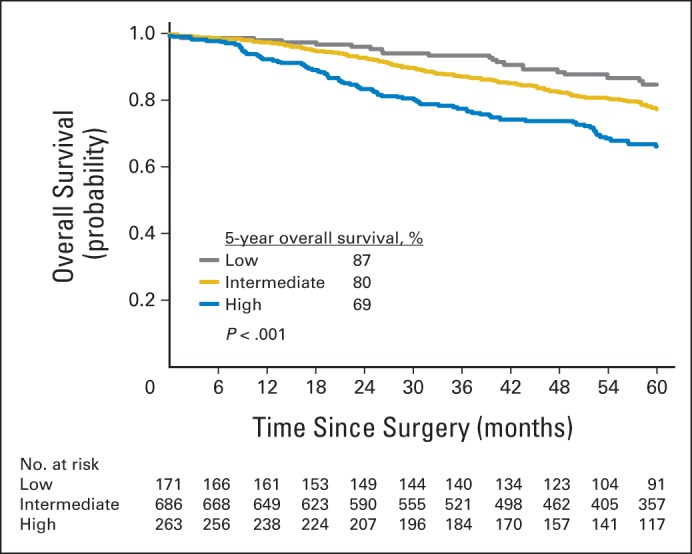

The smoothed graph of the hazard function for each architectural grade shows that the risk of recurrence was highest for high-grade tumors, followed by intermediate- and low-grade tumors (Fig 1B). In addition, the risk of recurrence peaked earlier for high-grade tumors (between 12 and 24 months) than for intermediate- or low-grade tumors (Fig 1C). The risk of recurrence was highest for solid predominant tumors (Fig 1D). Compared with patients with nonsolid tumors, patients with solid predominant tumors had earlier (recurrence within 2 years, 75% v 51%; P = .007), more extrathoracic (77% v 37%; P < .001), and more multisite (47% v 26%; P = .011) recurrences (Table 2). When analyzing OS by architectural grade, patients with high–architectural grade tumors had significantly worse OS compared with patients with intermediate- and low-grade tumors (5-year OS, high [69%] v intermediate [80%] v low [87%]; P < .001; Appendix Fig A1, online only).

Table 2.

Correlation Between Solid Predominant Histologic Pattern and Recurrence

| Variable | Solid No. (%) | Nonsolid No. (%) | P* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total No. of patients | 40 (21) | 148 (79) | |

| Recurrence pattern | < .001 | ||

| Locoregional | 6 (15) | 53 (36) | |

| Distant | 24 (60) | 76 (51) | |

| Both | 10 (25) | 19 (13) | |

| Recurrence pattern | < .001 | ||

| Intrathoracic | 9 (23) | 93 (63) | |

| Extrathoracic | 31 (77) | 55 (37) | |

| Recurrence pattern | .011 | ||

| Single site | 21 (53) | 110 (74) | |

| Multiple site | 19 (47) | 38 (26) | |

| Bone metastasis | |||

| Absent | 30 (75) | 119 (80) | .51 |

| Present | 10 (25) | 29 (20) | |

| Brain metastasis | |||

| Absent | 28 (70) | 131 (89) | .007 |

| Present | 12 (30) | 17 (11) | |

| Contralateral lung | |||

| Absent | 32 (80) | 122 (82) | .82 |

| Present | 8 (20) | 26 (18) | |

| Pleural effusion | |||

| Absent | 35 (88) | 126 (85) | .84 |

| Present | 5 (12) | 22 (15) | |

| Adrenal metastasis | |||

| Absent | 34 (85) | 141 (95) | .034 |

| Present | 6 (15) | 7 (5) | |

| Distant lymph node metastasis | |||

| Absent | 36 (90) | 134 (91) | > .99 |

| Present | 4 (10) | 14 (9) | |

| Liver metastasis | |||

| Absent | 35 (88) | 143 (97) | .038 |

| Present | 5 (12) | 5 (3) | |

| Chest wall metastasis | |||

| Absent | 39 (98) | 142 (96) | > .99 |

| Present | 1 (2) | 6 (4) | |

| Recurrence-free interval, months | |||

| ≤ 24 | 30 (75) | 75 (51) | .007 |

| > 24 | 10 (25) | 73 (49) |

Significant P values (< .05) are shown in bold type.

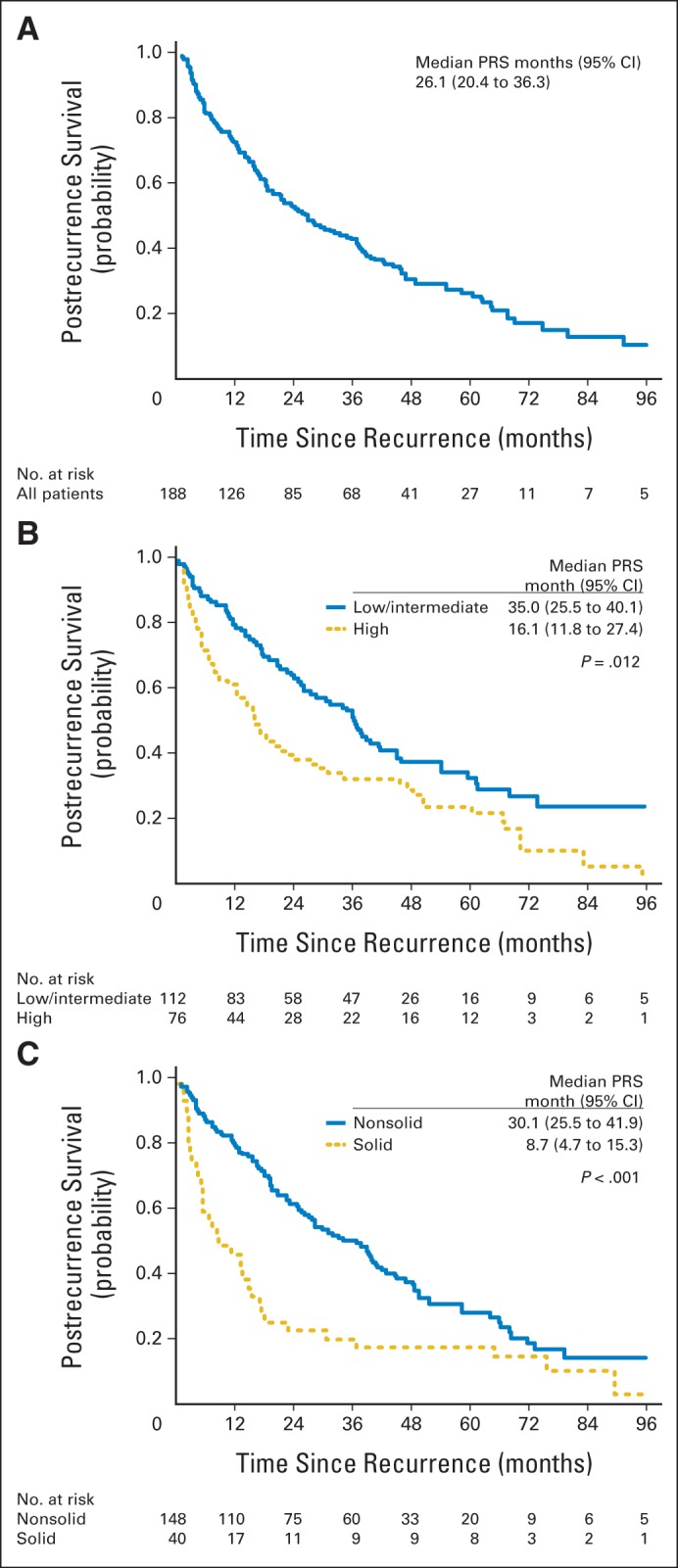

Of the 188 patients who experienced relapse, 59 (31%) had locoregional recurrence, 100 (53%) had distant recurrence, and 29 (15%) had both (Appendix Table A2, online only). The most commonly involved organs for distant recurrences were bone, contralateral lung, and brain. The majority of recurrences were detected by scheduled surveillance CT scan (123 [65%]: 56 locoregional and 67 distant). Symptomatic recurrences occurred in 60 patients (32%; two locoregional and 58 distant). Postrecurrence therapy was given to 157 patients (84%). Initial therapy was chemotherapy with or without radiation in 66 patients (35%); 69 patients (37%) received local therapy with either surgery or radiation (Appendix Table A2). Forty-nine patients received first-line chemotherapy, as detailed in Appendix Table A3 (online only). Of the patients who experienced recurrence, 134 died (103 as a result of cancer-related disease). Overall, 1- and 2-year PRS rates were 67% and 45%, respectively. Median PRS was 26.1 months (95% CI, 20.4 to 36.3 months; Fig 2A).

Fig 2.

(A) Postrecurrence survival (PRS) curve for patients with stage I lung adenocarcinoma. (B) PRS curves for patients with high–architectural grade tumors versus patients with low– and intermediate–architectural grade tumors. (C) PRS curves for patients with solid predominant tumors versus patients with nonsolid predominant tumors.

We next focused on the group of patients who experienced cancer recurrence during the study period. Because this set is a selected subgroup of the large cohort diagnosed with stage I tumors, the risk factors identified in the entire cohort (male, sublobar resection, stage IB, high architectural grade, and the presence of lymphatic, vascular, or pleural invasion) will be comparatively overrepresented among patients who recurred (Tables 1 and 3). We further evaluated risk factors related to the primary tumor and postrecurrence risk factors. On univariable analysis, the risk factors related to the primary tumor that were associated with PRS were age older than 65 years (P = .003), ever smoker (P = .037), sublobar resection (P = .043), vascular invasion (P = .019), high architectural tumor grade (P = .012; Fig 2B), and solid predominant histologic pattern (P < .001; Fig 2C). On multivariable analysis, solid predominant histologic pattern (hazard ratio [HR], 1.76; 95% CI, 1.11 to 2.77; P = .016), older age (HR, 1.63; 95% CI, 1.12 to 2.37; P = .01), and sublobar resection (HR, 1.60; 95% CI, 1.12 to 2.29; P = .01) remained independently associated with worse PRS. On univariable analysis of postrecurrence factors, age older than 65 years at recurrence (P = .003), distant metastasis (P = .007), multiple site recurrence (P = .001), extrathoracic metastasis (P < .001), and shorter (≤ 24 months) recurrence-free interval (P = .034) were significantly associated with worse PRS (Table 3). Of these factors, presence of distant (extrathoracic) metastasis (HR, 1.76; 95% CI, 1.13 to 2.76; P = .013) and age older than 65 years at recurrence (HR, 1.70; 95% CI, 1.12 to 2.6; P = .014) remained independent predictors of worse PRS on multivariable analysis (Table 4).

Table 3.

Patient Characteristics and Univariable Analyses of Postrecurrence Survival

| Characteristic | No. (%) | Median PRS (95% CI), Months | P* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total No. of patients | 188 | 26.1 (20.4 to 36.3) | |

| Primary tumor factor | |||

| Age at surgery, years | |||

| ≤ 65 | 73 (39) | 37.1 (22.6 to 62.5) | .003 |

| > 65 | 115 (61) | 21.2 (16.1 to 28.7) | |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 104 (55) | 23.4 (17.3 to 38.2) | .66 |

| Male | 84 (45) | 26.3 (21.2 to 38.1) | |

| Smoking history | |||

| Never | 28 (15) | 46.5 (27.4 to NA) | .037 |

| Ever | 160 (85) | 23.4 (17.5 to 32.8) | |

| Surgical procedure† | |||

| Lobectomy | 113 (60) | 29.5 (21.1 to 42.1) | .043 |

| Sublobar resection | 75 (40) | 20.7 (14.8 to 34.3) | |

| T factor | |||

| T1a | 83 (44) | 27.5 (19.0 to 45.5) | .61 |

| T1b | 33 (18) | 30.8 (22.9 to 45.7) | |

| T2a | 72 (38) | 17.4 (13.2 to 38.1) | |

| Pathologic stage | |||

| IA | 116 (62) | 27.5 (22.9 to 38.2) | .62 |

| IB | 72 (38) | 17.4 (13.2 to 38.1) | |

| Predominant histologic subtype | |||

| Lepidic | 8 (4) | NA | < .001 |

| Acinar | 69 (37) | 27.6 (22.6 to 39.1) | |

| Papillary | 35 (19) | 38.1 (28.7 to NA) | |

| Micropapillary | 26 (14) | 43.8 (17.6 to NA) | |

| Solid | 40 (21) | 8.7 (4.7 to 15.3) | |

| Invasive mucinous | 8 (4) | NA | |

| Colloid | 2 (1) | NA | |

| Architectural grade | |||

| Low and intermediate | 112 (60) | 35.0 (25.5 to 40.1) | .012 |

| High | 76 (40) | 16.1 (11.8 to 27.4) | |

| Solid predominant | |||

| No | 148 (79) | 30.1 (25.5 to 41.9) | < .001 |

| Yes | 40 (21) | 8.7 (4.7 to 15.3) | |

| Micropapillary predominant | |||

| No | 162 (86) | 26.1 (18.9 to 36.2) | .68 |

| Yes | 26 (14) | 43.8 (17.6 to N/A) | |

| Lymphatic invasion | |||

| Absent | 80 (43) | 28.7 (16.3 to 45.5) | .96 |

| Present | 108 (57) | 26.1 (20.4 to 36.3) | |

| Vascular invasion | |||

| Absent | 107 (57) | 36.5 (25.5 to 45.7) | .019 |

| Present | 81 (43) | 17.4 (14.8 to 31.6) | |

| Pleural invasion | |||

| Absent | 144 (77) | 27.5 (20.7 to 37.4) | .53 |

| Present | 44 (23) | 17.2 (10.1 to 41.9) | |

| Postrecurrence factor | |||

| Age at recurrence, years | |||

| ≤ 65 | 53 (28) | 45.7 (20.4 to NA) | .007 |

| > 65 | 135 (72) | 23.4 (17.4 to 32.8) | |

| Recurrence pattern | |||

| Locoregional only | 59 (31) | 42.1 (31.6 to 60.3) | .007 |

| Distant | 129 (69) | 17.6 (15.2 to 27.4) | |

| Recurrence site | |||

| Single site | 131 (70) | 35.0 (26.2 to 43.8) | .001 |

| Multiple site | 57 (30) | 11.4 (6.2 to 17.5) | |

| Intrathoracic | 102 (54) | 41.9 (32.8 to 55.0) | < .001 |

| Extrathoracic | 86 (46) | 12.0 (9.8 to 17.5) | |

| Recurrence-free interval, months | |||

| ≤ 24 | 105 (56) | 17.2 (14.0 to 26.2) | .034 |

| > 24 | 83 (44) | 37.4 (31.6 to 48.3) |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; PRS, postrecurrence survival.

Significant P values (< .05) are shown in bold type.

Lobectomy: pneumonectomy, bilobectomy, or lobectomy; sublobar resection: segmentectomy or wedge resection.

Table 4.

Multivariable Analysis in Predicting Postrecurrence Survival

| Factor | HR | 95% CI | P* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary tumor factors | |||

| Age at diagnosis (> 65 v ≤ 65 years) | 1.63 | 1.12 to 2.37 | .01 |

| Smoking (ever v never) | 1.64 | 0.94 to 2.88 | .083 |

| Surgical procedure (sublobar resection v lobectomy) | 1.6 | 1.12 to 2.29 | .01 |

| Vascular invasion (present v absent) | 1.41 | 0.97 to 2.06 | .073 |

| Histologic pattern | |||

| High-grade v low- or intermediate-grade SOL | 1.76 | 1.11 to 2.77 | .016 |

| High-grade v low- or intermediate-grade non-SOL† | 1.2 | 0.75 to 1.91 | .44 |

| Postrecurrence factors | |||

| Age at recurrence (> 65 v ≤ 65 years) | 1.7 | 1.12 to 2.6 | .014 |

| Recurrence-free interval (≤ 24 v > 24 months) | 1.22 | 0.84 to 1.77 | .31 |

| Recurrence pattern (multiple-site v single-site) | 1.5 | 0.99 to 2.28 | .058 |

| Distant, intrathoracic v locoregional | 0.88 | 0.51 to 1.49 | .62 |

| Distant, extrathoracic v locoregional | 1.76 | 1.13 to 2.76 | .013 |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; SOL, solid predominant.

Significant P values (< .05) are shown in bold type.

High-grade: SOL v non-SOL, P = .19.

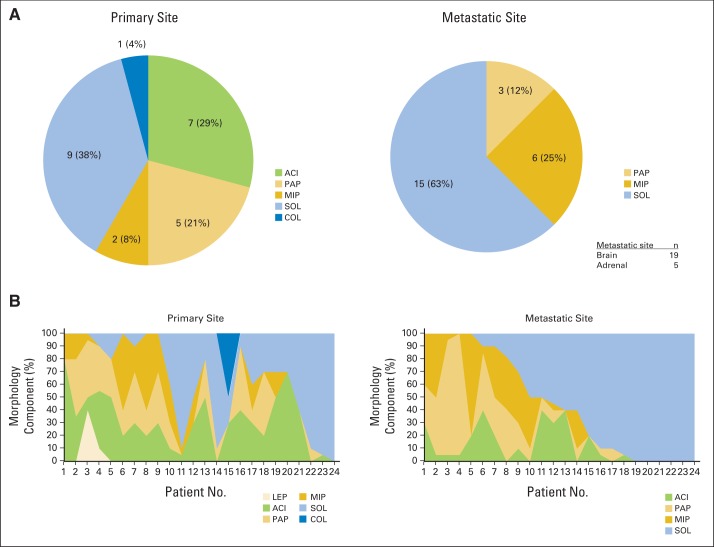

We compared 24 metastatic site (brain, 19; adrenal, five) morphology components with primary site morphology components. The predominant subtype of the metastatic sites in patients with primary tumors with solid predominant subtype was solid (100%). The solid predominant subtype occurred at a high frequency in metastatic sites, even in patients in whom the primary tumor showed other predominant subtypes (Appendix Table A4 and Appendix Fig A2A, online only). At metastatic sites, the solid morphology component had the greatest increase compared with any other component (Appendix Fig A2B).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have shown that high architectural grade tumors carry a high risk of recurrence after surgical resection and, among patients who recur, are associated with a uniquely unfavorable PRS. Of importance, we have identified that the risk of recurrence for tumors with solid predominant histologic subtype peaked within 12 months and that these tumors were associated with a higher incidence of extrathoracic, multiple-site recurrences in patients with stage I lung adenocarcinoma. Furthermore, our study showed that, in the selected group of patients who recurred after initial surgical resection for stage I lung adenocarcinoma, several factors determined at the time of initial surgery (solid predominant histologic pattern, sublobar resection, and age older than 65 years) were independently associated with worse PRS; among factors determined at time of recurrence, distant (extrathoracic) metastases and age older than 65 years at recurrence were independently associated with worse PRS.

The effect of disease pathology on recurrence has been reported before by our group and others; we were able to confirm it in a large, single-center cohort in this study. Furthermore, we focused on PRS to assess whether the effect of morphology on the primary tumor extends beyond affecting risk of recurrence and if, for patients who recur, it increases likelihood of early death.

The strengths of our study are that it includes the largest cohort of patients with stage I lung adenocarcinoma published to date with a median follow-up of 60 months, comprehensive clinicopathologic and histologic assessment were performed, detailed analysis of recurrence patterns was documented, and to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to analyze recurrence patterns and PRS in relation to the IASLC/ATS/ERS classification. Investigation of the hazard function27–29 indicated that the instantaneous risk of recurrence was highest and the risk of recurrence peaked earlier for solid predominant tumors than for the other tumor types. Most recurrences, including recurrences from solid predominant tumors, occurred within 2 years of surgery. Although our findings support the importance of routine CT surveillance, in accordance with National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, we have shown that regular surveillance is even more important when tumors of aggressive predominant subtypes (eg, solid predominant histologic pattern) are present.

Our previous publications have documented that the solid predominant subtype and the presence of solid pattern are associated with poor prognostic factors: higher maximum standardized uptake value on preoperative PET scan,30 higher mitotic count,8 visceral pleural invasion,31 high grade of tumor budding,32 presence of tumor spread throughout the alveolar space,33 high risk of occult lymph node metastases,34 thyroid transcription factor-1 negativity,35 and less frequent epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations.36 Our finding of a correlation between the presence of solid pattern and unfavorable prognosis is consistent with the observations of others. Bryant et al37 reported that tumors with solid pattern had more genes promoting cell proliferation, which correlated with decreased survival, compared with tumors without solid pattern.

We have shown that the presence of micropapillary pattern in stage I lung adenocarcinoma is associated with a higher incidence of locoregional recurrence.19 By analyzing patterns of relapse in this study, we have shown that the solid predominant subtype is correlated with distant (extrathoracic) metastasis and multiple-site recurrence in patients with primary lung adenocarcinoma; there were especially high rates of metastasis to the brain, contralateral lung, and liver (Table 2). In this study, the solid subtype was predominant in two thirds of the metastatic tissues (brain and adrenal metastases) examined (n = 24; Appendix Table A4). Clay et al38 showed that the presence of solid histologic subtype at the site of metastasis was associated with shorter OS. These observations highlight the importance of performing a molecular characterization of solid lung adenocarcinomas to identify novel molecular targets. Our observations and those of others show that, despite curative-intent surgical resection, solid predominant histologic pattern is associated with an aggressive metastasis and recurrence profile, thereby providing a rationale for investigating the role of adjuvant therapies for this cohort of patients.

For early-stage lung adenocarcinoma, the predictive effect of the new classification system on adjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy remains unknown. Recently, in patients with advanced lung adenocarcinoma, Warth et al39 demonstrated that histologic pattern of the tumor influenced the effect of adjuvant chemoradiotherapy; in particular, solid predominant tumors had improved prognoses with adjuvant radiotherapy. However, this predictive effect of histologic pattern was not significant on multivariable analysis.

Publications from our group36 and others40 have shown that solid predominant lung adenocarcinomas are less likely to harbor EGFR mutations and more likely to harbor KRAS mutations compared with other predominant subtypes This finding implies that there is currently no actionable target for the treatment of most solid lung adenocarcinomas. Extended molecular and clinicopathologic analysis of lung adenocarcinomas revealed an association between KRAS mutation and both solid histologic subtype and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes.41 Zhang et al42 have shown that lung adenocarcinomas with positive programmed death-ligand 1 staining were most likely to be the solid predominant subtype. From these observations, it is tempting to speculate that immunotherapies can play a role in the treatment of solid predominant lung adenocarcinomas. Ongoing clinical trials on checkpoint blockade should document the histologic subtype of the lung adenocarcinomas encountered.

In conclusion, prognostic stratification using the IASLC/ATS/ERS classification system can be readily implemented in the treatment of patients with early-stage lung adenocarcinoma. Future clinical studies should collect data on the histologic subtype of the lung adenocarcinomas encountered, which may yield more accurate information on the relationship between subtype, risk of recurrence, and PRS and lead to improvements in the clinical assessment of and the therapeutic strategies for recurrent non–small-cell lung cancer. Our finding of early, multisite, extrathoracic metastases in patients with solid predominant stage I lung adenocarcinoma who have undergone curative-intent resection underlines the need to investigate adjuvant therapeutic strategies for these patients.

Acknowledgment

We thank Joe Dycoco for assisting with the Thoracic Surgery Service's Lung Cancer Database and David Sewell and Alex Torres for their editorial assistance (all from the Memorial Sloan Kettering Thoracic Surgery Service).

Appendix

Table A1.

Postrecurrence Survival of Patients in Previous Stage I NSCLC Series

| Reference | Year of Publication | No. of Patients | Histologic Profile | Recurrence | Recurrence No. (%) | PRS |

Independent Factors of Poor PRS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duration | % | |||||||

| Current study | 2014 | 1,120 | ADC: 1,120 | ADC: 188 | 188 (17) | 1-year | 67 | Solid predominant histologic pattern |

| LR: 59 (31) | 2-year | 45 | Sublobar resection | |||||

| D: 100 (53) | 3-year | 36 | Old age | |||||

| LR + D: 29 (15) | 5-year | 14 | Distant (extrathoracic) metastasis | |||||

| Shimada et al10 | 2013 | 919 | ADC: 706 | ADC: 124 | 170 (18) | 1-year | 73 | Male sex |

| Non-ADC: 213 | Non-ADC: 46 | LR: 43 (25) | 2-year | 51 | Non-postrecurrence therapy | |||

| D: 113 (66) | Poorly differentiated | |||||||

| LR + D: 14 (9) | ||||||||

| Song et al11 | 2013 | 475 | NSCLC | ADC: 46 | 72 (15) | 1-year | 88 | Recurrence-free interval ≤ 12 months |

| SCC: 15 | LR: 36 (50) | 3-year | 53 | Bad response for treatment | ||||

| Other: 11 | D: 36 (50) | |||||||

| Nakagawa et al12 | 2008 | 397 | ADC: 300 | NA | 87 (22) | 1-year | 67 | Non-postrecurrence therapy (surgery); symptoms at recurrence: liver or cervico-mediastinum metastasis |

| SCC: 89 | LR: 30 (34.5) | 3-year | 35 | |||||

| Other: 8 | D: 57 (65.5) | |||||||

| Hung et al13 | 2009 | 933 | NSCLC | ADC: 45 | LR: 123 (13) | 1-year | 48 | Non-postrecurrence therapy (surgery, chemotherapy, and/or radiotherapy) |

| SCC: 60 | LR: 74 | 2-year | 19 | |||||

| Other: 18 | LR + D: 49 | |||||||

| Hung et al14 | 2010 | 933 | NSCLC | ADC: 95 | D: 166 (18) | 1-year | 38 | Non-postrecurrence therapy |

| SCC: 46 | Single: 106 | 2-year | 19 | Recurrence-free interval ≤ 16 months | ||||

| Other: 25 | Multiple: 60 | |||||||

| Hung et al9 | 2013 | 283 | ADC: 283 | ADC: 283 | 57 (20) | 2-year | 72.3 | Solid predominant (P = .074; not significant); non-papillary predominant (P = .056; not significant) |

| 5-year | 31.6 | |||||||

Abbreviations: ADC, adenocarcinoma; D, distant metastasis; LR, locoregional recurrence; NA, not applicable; NSCLC, non–small-cell lung cancer; PRS, postrecurrence survival; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

Table A2.

Characteristics of the 188 Patients Who Experienced Recurrence

| Characteristic | No. | % |

|---|---|---|

| Location | ||

| Locoregional | 59 | 31 |

| Regional lymph nodes | 13 | |

| Same side | 34 | |

| Residual lobe (sublobar resection) | 9 | |

| Staple line | 5 | |

| Distant metastasis | 100 | 53 |

| Single site | 73 | |

| Multisite | 27 | |

| Both (locoregional and distant) | 29 | 15 |

| Intrathoracic only | 102 | 54 |

| Extrathoracic | 86 | 46 |

| Distant metastasis location* | ||

| Bone | 39 | |

| Contralateral lung | 34 | |

| Brain | 29 | |

| Pleural disease | 27 | |

| Distant lymph node | 18 | |

| Adrenal | 13 | |

| Liver | 10 | |

| Chest wall | 7 | |

| Other | 8 | |

| Detection method | ||

| Scheduled computed tomography scan | 123 | 65 |

| Locoregional | 56 | |

| Distant metastasis | 67 | |

| Symptoms | 60 | 32 |

| Locoregional | 2 | |

| Distant metastasis | 58 | |

| Other (carcinoembryonic antigen) | 4 | 2 |

| Unknown | 1 | 1 |

| Initial therapy of recurrence | 157 | 84 |

| Single therapy | 120 | 64 |

| Chemotherapy | 49 | |

| Radiation therapy | 37 | |

| Surgery | 32 | |

| Radiofrequency ablation | 2 | |

| Multimodality therapy | 37 | 20 |

| Chemotherapy + radiation therapy | 17 | |

| Surgery + radiation therapy | 11 | |

| Surgery + chemotherapy | 8 | |

| Surgery + chemotherapy + radiation therapy | 1 | |

| Palliative therapy | 2 | 1 |

| Observation | 5 | 3 |

| Unknown | 24 | 13 |

Sites of multiple metastases were counted individually.

Table A3.

First-Line Chemotherapy Regimen (N = 49)

| Regimen | No. of Patients |

|---|---|

| Platinum-based chemotherapy | |

| Cisplatin (1) or carboplatin (1) + paclitaxel | 2 |

| Cisplatin (1) or carboplatin (2) + docetaxel | 3 |

| Cisplatin (1) or carboplatin (4) + gemcitabine | 5 |

| Cisplatin (2) or carboplatin (3) + pemetrexed | 5 |

| Bevacizumab/platinum combination | |

| Bevacizumab + carboplatin (3) + paclitaxel | 3 |

| Bevacizumab + cisplatin (4) or carboplatin (5) + pemetrexed | 9 |

| EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor | |

| Erlotinib | 8 |

| Gefitinib | 1 |

| Single-agent chemotherapy | |

| Paclitaxel | 1 |

| Pemetrexed | 5 |

| Gemcitabine | 1 |

| Other | |

| Clinical trial | 3 |

| Mitomycin + vinorelbine | 1 |

| Unknown* | 2 |

Platinum-based therapy was administered at an outside hospital; additional details are unknown.

Table A4.

Predominant Morphology of Primary and Metastatic Sites

| Patient | Primary Site |

Metastatic Site |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major Type | Secondary Type | Site | Major Type | Secondary Type | |

| 1 | Acinar | Papillary | Brain | Papillary | Acinar |

| 2 | Acinar | Micropapillary | Brain | Micropapillary | Papillary |

| 3 | Acinar | Papillary | Brain | Micropapillary | Acinar |

| 4 | Acinar | Papillary | Brain | Solid | Acinar |

| 5 | Acinar | Papillary | Brain | Solid | Papillary |

| 6 | Acinar | Solid | Brain | Solid | — |

| 7 | Acinar | Solid | Adrenal | Solid | — |

| 8 | Papillary | Lepidic | Brain | Papillary | Micropapillary |

| 9 | Papillary | Acinar | Brain | Micropapillary | Papillary |

| 10 | Papillary | Acinar | Brain | Micropapillary | Papillary |

| 11 | Papillary | Micropapillary | Brain | Micropapillary | Solid |

| 12 | Papillary | Solid | Adrenal | Solid | Acinar |

| 13 | Micropapillary | Papillary | Brain | Papillary | Micropapillary |

| 14 | Micropapillary | Papillary | Brain | Micropapillary | Papillary |

| 15 | Solid | Micropapillary | Brain | Solid | Micropapillary |

| 16 | Solid | Micropapillary | Brain | Solid | Micropapillary |

| 17 | Solid | Acinar | Brain | Solid | Acinar |

| 18 | Solid | Papillary | Adrenal | Solid | Micropapillary |

| 19 | Solid | Acinar | Brain | Solid | Papillary |

| 20 | Solid | Acinar | Brain | Solid | — |

| 21 | Solid | Papillary | Brain | Solid | — |

| 22 | Solid | Acinar | Adrenal | Solid | — |

| 23 | Solid | — | Adrenal | Solid | — |

| 24 | Colloid | Acinar, solid | Brain | Solid | Acinar |

Fig A1.

Overall survival of patients with stage I lung adenocarcinoma for each architectural grade.

Fig A2.

(A) Predominant morphology of primary site and metastatic site. (B) Morphology component of primary site and metastatic site. ACI, acinar predominant (invasive adenocarcinoma); COL, colloid predominant (invasive adenocarcinoma); LEP, lepidic predominant; MIP, micropapillary predominant (invasive adenocarcinoma); PAP, papillary predominant (invasive adenocarcinoma); SOL, solid predominant (invasive adenocarcinoma).

Footnotes

Supported in part by Grants No. R21 CA164568-01A1, R21 CA164585-01A1, R01 CA136705-06, U54 CA137788, P30 CA008748, and P50 CA086438-13 from the National Institutes of Health and Grants No. PR101053 and LC110202 from the US Department of Defense (P.S.A.).

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest are found in the article online at www.jco.org. Author contributions are found at the end of this article.

The sponsors had no role in study design, collaboration, or analysis of data or manuscript preparation.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Disclosures provided by the authors are available with this article at www.jco.org.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Prasad S. Adusumilli

Financial support: Prasad S. Adusumilli

Administrative support: William D. Travis, David R. Jones, Prasad S. Adusumilli

Provision of study materials or patients: James Huang, William D. Travis, Nabil P. Rizk, Prasad S. Adusumilli

Collection and assembly of data: Hideki Ujiie, Kyuichi Kadota, Ming-Ching Lee, Prasad S. Adusumilli

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Solid Predominant Histologic Subtype in Resected Stage I Lung Adenocarcinoma Is an Independent Predictor of Early, Extrathoracic, Multisite Recurrence and of Poor Postrecurrence Survival

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or jco.ascopubs.org/site/ifc.

Hideki Ujiie

No relationship to disclose

Kyuichi Kadota

No relationship to disclose

Jamie E. Chaft

Honoraria: DAVA Oncology

Consulting or Advisory Role: Myriad Genetics, Biodesix, Otsuka

Research Funding: Eli Lilly (Inst)

Daniel Buitrago

No relationship to disclose

Camelia S. Sima

Employment: Genentech/Roche

Ming-Ching Lee

No relationship to disclose

James Huang

Research Funding: Bristol-Myers Squibb

William D. Travis

No relationship to disclose

Nabil P. Rizk

No relationship to disclose

Charles M. Rudin

Consulting or Advisory Role: AbbVie, AVEO Pharmaceuticals, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Celgene

Research Funding: BioMarin Pharmaceutical

David R. Jones

No relationship to disclose

Prasad S. Adusumilli

Research Funding: Myriad Genetics

REFERENCES

- 1.Martini N, Bains MS, Burt ME, et al. Incidence of local recurrence and second primary tumors in resected stage I lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1995;109:120–129. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(95)70427-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldstraw P, Crowley J, Chansky K, et al. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: Proposals for the revision of the TNM stage groupings in the forthcoming (seventh) edition of the TNM Classification of malignant tumours. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2:706–714. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31812f3c1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. Aberle DR, Adams AM, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:395–409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kovalchik SA, Tammemagi M, Berg CD, et al. Targeting of low-dose CT screening according to the risk of lung-cancer death. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:245–254. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1301851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Black WC, Gareen IF, Soneji SS, et al. Cost-effectiveness of CT screening in the National Lung Screening Trial. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1793–1802. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1312547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoshizawa A, Motoi N, Riely GJ, et al. Impact of proposed IASLC/ATS/ERS classification of lung adenocarcinoma: Prognostic subgroups and implications for further revision of staging based on analysis of 514 stage I cases. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:653–664. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sica G, Yoshizawa A, Sima CS, et al. A grading system of lung adenocarcinomas based on histologic pattern is predictive of disease recurrence in stage I tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:1155–1162. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181e4ee32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kadota K, Suzuki K, Kachala SS, et al. A grading system combining architectural features and mitotic count predicts recurrence in stage I lung adenocarcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:1117–1127. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hung JJ, Jeng WJ, Chou TY, et al. Prognostic value of the new International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer/American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society lung adenocarcinoma classification on death and recurrence in completely resected stage I lung adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 2013;258:1079–1086. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31828920c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shimada Y, Saji H, Yoshida K, et al. Prognostic factors and the significance of treatment after recurrence in completely resected stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Chest. 2013;143:1626–1634. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Song IH, Yeom SW, Heo S, et al. Prognostic factors for post-recurrence survival in patients with completely resected Stage I non-small-cell lung cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2014;45:262–267. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezt333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakagawa T, Okumura N, Ohata K, et al. Postrecurrence survival in patients with stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2008;34:499–504. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2008.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hung JJ, Hsu WH, Hsieh CC, et al. Post-recurrence survival in completely resected stage I non-small cell lung cancer with local recurrence. Thorax. 2009;64:192–196. doi: 10.1136/thx.2007.094912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hung JJ, Jeng WJ, Hsu WH, et al. Prognostic factors of postrecurrence survival in completely resected stage I non-small cell lung cancer with distant metastasis. Thorax. 2010;65:241–245. doi: 10.1136/thx.2008.110825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Travis WD, Brambilla E, Noguchi M, et al. International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer/American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society international multidisciplinary classification of lung adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:244–285. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318206a221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Guidelines for surveillance following therapy for NSCLC. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp#detection.

- 17.Lou F, Huang J, Sima CS, et al. Patterns of recurrence and second primary lung cancer in early-stage lung cancer survivors followed with routine computed tomography surveillance. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;145:75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lou F, Sima CS, Rusch VW, et al. Differences in patterns of recurrence in early-stage versus locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;98:1755–1760. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.05.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nitadori J, Bograd AJ, Kadota K, et al. Impact of micropapillary histologic subtype in selecting limited resection vs lobectomy for lung adenocarcinoma of 2cm or smaller. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:1212–1220. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Girard N, Deshpande C, Lau C, et al. Comprehensive histologic assessment helps to differentiate multiple lung primary nonsmall cell carcinomas from metastases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1752–1764. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181b8cf03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amini A, Lou F, Correa AM, et al. Predictors for locoregional recurrence for clinical stage III-N2 non-small cell lung cancer with nodal downstaging after induction chemotherapy and surgery. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:1934–1940. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2800-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dignam JJ, Zhang Q, Kocherginsky M. The use and interpretation of competing risks regression models. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:2301–2308. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gray RJ. A class of K-sample tests for comparing the cumulative incidence of a competing risk. Ann Stat. 1988;16:1141–1154. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94:496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hess KR, Serachitopol DM, Brown BW. Hazard function estimators: A simulation study. Stat Med. 1999;18:3075–3088. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19991130)18:22<3075::aid-sim244>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Müller HG, Wang JL. Hazard rate estimation under random censoring with varying kernels and bandwidths. Biometrics. 1994;50:61–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Metzger-Filho O, Sun Z, Viale G, et al. Patterns of recurrence and outcome according to breast cancer subtypes in lymph node-negative disease: Results from International Breast Cancer Study Group trials VIII and IX. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3083–3090. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.1574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saphner T, Tormey DC, Gray R. Annual hazard rates of recurrence for breast cancer after primary therapy. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:2738–2746. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.10.2738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Simes RJ, Zelen M. Exploratory data analysis and the use of the hazard function for interpreting survival data: An investigator's primer. J Clin Oncol. 1985;3:1418–1431. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1985.3.10.1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kadota K, Colovos C, Suzuki K, et al. FDG-PET SUVmax combined with IASLC/ATS/ERS histologic classification improves the prognostic stratification of patients with stage I lung adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:3598–3605. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2414-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nitadori J, Colovos C, Kadota K, et al. Visceral pleural invasion does not affect recurrence or overall survival among patients with lung adenocarcinoma ≤ 2 cm: A proposal to reclassify T1 lung adenocarcinoma. Chest. 2013;144:1622–1631. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-0394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kadota K, Yeh YC, Rizk NP, et al. In patients with stage I lung adenocarcinoma, tumor budding is a significant prognostic factor for recurrence, independent of the IASLC/ATS/ERS classification, and correlates with a protumor immune microenvironment. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8:S415. (abstr MO26.03) [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kadota K, Nitadori JI, Sima CS, et al. Tumor spread through air spaces is an important pattern of invasion and impacts the frequency and location of recurrences following limited resection for small stage I lung adenocarcinomas. J Thorac Oncol. 2015;10:806–814. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yeh YC, Nitadori J, Kadota K, et al. Micropapillary histology is associated with occult lymph node metastasis (pN2) in patients with clinically N2-negative (cN0/N1) lung adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8:S671–S672. (abstr P1.18-019) [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kadota K, Nitadori J, Sarkaria IS, et al. Thyroid transcription factor-1 expression is an independent predictor of recurrence and correlates with the IASLC/ATS/ERS histologic classification in patients with stage I lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer. 2013;119:931–938. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kadota K, Yeh YC, D'Angelo SP, et al. Associations between mutations and histologic patterns of mucin in lung adenocarcinoma: Invasive mucinous pattern and extracellular mucin are associated with KRAS mutation. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38:1118–1127. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bryant CM, Albertus DL, Kim S, et al. Clinically relevant characterization of lung adenocarcinoma subtypes based on cellular pathways: An international validation study. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11712. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clay TD, Do H, Sundararajan V, et al. The clinical relevance of pathologic subtypes in metastatic lung adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Oncol. 2014;9:654–663. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Warth A, Muley T, Meister M, et al. The novel histologic International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer/American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society classification system of lung adenocarcinoma is a stage-independent predictor of survival. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1438–1446. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang Y, Li J, Wang R, et al. The prognostic and predictive value of solid subtype in invasive lung adenocarcinoma. Sci Rep. 2014;4:7163. doi: 10.1038/srep07163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rekhtman N, Ang DC, Riely GJ, et al. KRAS mutations are associated with solid growth pattern and tumor-infiltrating leukocytes in lung adenocarcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2013;26:1307–1319. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2013.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang Y, Wang L, Li Y, et al. Protein expression of programmed death 1 ligand 1 and ligand 2 independently predict poor prognosis in surgically resected lung adenocarcinoma. Onco Targets Ther. 2014;7:567–573. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S59959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]