Abstract

Aim

To determine the frequency and topographic distribution of cerebral microbleeds (CMBs) in dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) in comparison to CMBs in Alzheimer disease dementia (AD).

Methods

Consecutive probable DLB (n= 23) patients who underwent 3-tesla T2* weighted gradient-recalled-echo MRI, and age and gender matched probable Alzheimer’s disease patients (n=46) were compared for the frequency and location of CMBs.

Results

The frequency of one or more CMBs was similar among patients with DLB (30%) and AD (24%). Highest densities of CMBs were found in the occipital lobes of patients with both DLB and AD. Patients with AD had greater densities of CMBs in the temporal lobes and deep or infratentorial regions compared to DLB (p<0.05)

Conclusion

CMBs are as common in patients with DLB as in patients with AD, with highest densities observed in the occipital lobes, suggesting common pathophysiologic mechanisms underlying CMBs in both diseases.

Keywords: Dementia with Lewy bodies, Cerebral Microbleeds, Alzheimer disease, Cerebral amyloid angiopathy, T2* weighted gradient-recalled-echo MRI

Introduction

Hypointense foci on T2* Gradient Recalled Echo MRI associated with cerebral microbleeds (CMBs) are found in approximately 24% to 33% of Alzheimer disease dementia (AD) patients.[1; 2; 3; 4] Although the number of CMB in patients with dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) appear to be similar to AD patients, the regional density of CMBs referenced to lobar volumes have not been established in DLB.[5] Lobar microbleeds, particularly in the occipital, posterior temporal and patietal lobes are typically associated with amyloid deposition and cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) [6; 7; 8]. Because a majority of patients with DLB have high amyloid-β (Aβ) deposition on PET imaging,[9; 10; 11] we hypothesized that patients with DLB are at an increased risk for CMBs as much as patients with AD. In this study, we investigated the density and topographic distribution of CMB in patients with DLB compared to AD.

Methods

1. Subjects and clinical evaluations

Consecutive patients with probable DLB (n=23) with median age of 69 (interquartile range [IQR] 64–74) years from the Mayo Clinic Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC), underwent a 3T MRI examination from June 2010 until March 2012. Age and sex 2:1 matched patients with AD dementia (n=46) from the ADRC were included as referent group. History of cardiovascular disease, stroke, hypertension and diabetes were recorded through self report at the time of MRI.

Patients with DLB fulfilled the Consortium criteria for probable DLB [12] and patients with AD dementia fulfilled the NINCDS-ADRDA criteria for probable AD [13]. Patients were excluded if they had history of traumatic brain injury, hydrocephalus, intracranial mass, or other neurologic diseases that may influence imaging findings.

This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board, and informed consent for participation was obtained from every subject.

2. MRI studies

2.1. MRI acquisition

A standardized MRI imaging protocol was performed on all subjects included in the study using a 3.0 Tesla scanner, including 1) a 3D magnetization prepared rapid acquisition gradient echo (MPRAGE) sequence (TR/TE/T1= 2300/3/900ms; flip angle=8°; FOV=26cm; in-plane matrix=256×256; phase FOV=0.94; slice thickness=1.2 mm; and 2) T2* a GRE sequence (TR/TE=200/20ms; flip angle=12°; FOV=20cm; in-plane matrix=256×224; phase FOV=1.00; slice thickness=3.3mm).

2.2. Identification of CMBs

All CMBs and superficial siderosis were identified by a trained neurologist and secondarily confirmed by two radiologists experienced in reading the T2* GRE images (K.K. and C.R.J.), who were blinded to the diagnostic group. Definite CMBs were defined as small homogenous hypointense lesions up to 10 mm in diameter in the gray or white matter on T2* GRE images as previously described. [1] Occasionally, it was not possible to make a definitive decision, such as distinguishing a CMB from a vascular flow-void. In such instances, the CMB was labeled as “possible CMB” and was not included in the analysis.

2.3. Tracking and registration of CMB to a common template

The location of each observed CMB was recorded in the coordinate system of the image on which it was made. Findings observed on these images were propagated into the coordinate system of the image under evaluation. A T1 (MPRAGE) image of the subject was registered and resampled into the space of the image under evaluation. The T1 image carries an in-house modified automated anatomic labeling atlas [14] defining bilateral frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital lobar regions and deep/infratentorial gray and white matter regions. Because the lobar regions differ in volume, we calculated the regional CMB densities as referenced to the volume of the region rather than simply count per region, combining the right and left hemispheres.

3. Statistics

Clinical and demographic characteristics including the frequency of CMB in DLB and AD patients were compared using a Student’s t-test or a chi-squared test as appropriate. Mean CMB densities in patients with DLB and AD were compared using Student’s t-tests.

Results

Patients with DLB and AD dementia were matched on age and sex and they did not differ on education, duration of disease, and clinical severity such as CDR-Sum of Boxes and Dementia Rating Scale and history of cardiovascular risk factors or stroke. A significantly higher proportion of patients with AD dementia (73%) were APOE ε4 carriers, compared to patients with DLB (41%). (Table 1)

Table 1.

Subject demographics (all subjects).

| DLB (n = 23) | AD (n = 46) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. Microbleeds Positive (%) | 7 (30) | 11 (24) | 0.56 |

| No. Female (%) | 3 (13) | 13 (28) | 0.16 |

| Age at mri yrs. | 69 (64, 74) | 71 (62, 78) | 0.72 |

| Age at onset. | 63 (57, 70) | 64 (57, 70) | 0.63 |

| Disease duration, yrs. | 6 (4, 10) | 5 (4, 9) | 0.63 |

| Education, yrs. | 16 (14, 18) | 16 (14, 17) | 0.90 |

| APOE ε carrier, n (%) | 9 (41) | 33 (73) | 0.01 |

| CDR-Sum of Boxes score | 6 (4, 8) | 4 (3, 7) | 0.17 |

| Dementia Rating Scale. | 124 (104, 130) | 118 (103, 126) | 0.88 |

| Whole brain density, mean (sd) | 1.39 (2.47) | 5.51 (17.12) | 0.12 |

| Presence of vascular disease and risk factors for vascular disease | |||

| Cardiovascular disease (%) | 4 (19) | 8 (19) | >0.99 |

| Stroke/TIA (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | >0.99 |

| Hypertension (%) | 7 (32) | 25 (54) | 0.08 |

| Diabetes (%) | 2 (9) | 1 (2) | 0.55 |

Unless otherwise indicated, values shown are median (IQR). P values were calculated using Student’s t test or chi-squared test as appropriate. Abbreviations: CDR, Clinical Dementia Rating. Disease duration is years from onset date to scan date.

There were 67 lesions labeled as definite CMB among the AD and DLB subjects. A total of 18 subjects (7 DLB and 11 AD) had at least one definite CMB identified on the T2* scan. The frequency of total MBs was 24% in the AD group and 30% in the DLB group, with no statistically significant difference among the two groups. (Table 1).

One patient with DLB and eight patients with AD dementia had multiple CMBs (2 CMBs in one DLB subject, and respectively 2, 2, 2, 5, 10, 12, 22 MBs in the AD patients. Remaining patients had a single CMB. Three patients with AD (6.5%) had superficial siderosis, in contrast, superficial siderosis was not identified in patients with DLB.

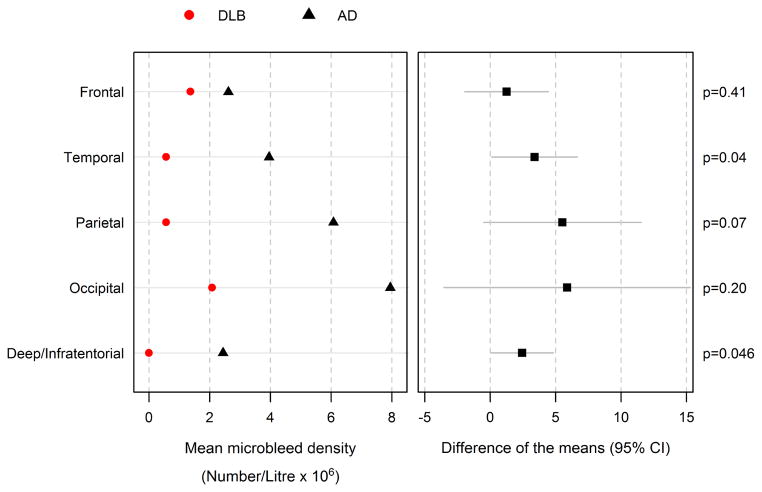

Differences in the regional distribution of CMBs were observed among the DLB and AD groups. Considering the regional volumes, within the AD group, CMBs were most densely concentrated in the occipital lobes followed by parietal and temporal lobes, while lower CMBs were observed in the frontal lobes and deep and infratentorial grey and white matter regions. Within the DLB group, CMBs were concentrated in the occipital and frontal lobes, followed by parietal and temporal lobes. No CMBs were found in the deep or infratentorial regions. Patients with DLB showed a significantly lower mean CMB density in the deep or infratentorial regions (p=0.046) and temporal lobes (p=0.04) compared to patients with AD. (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Mean microbleed density by region and diagnosis (left) and the difference of the Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) group means with 95% confidence intervals (right) P-values are extracted from Student’s t-Test.

Discussion

This study showed that CMBs are common in patients with DLB. Approximately one third of patients with DLB had one or more CMBs. While the frequency of CMBs was similar in AD (24%) and DLB (30%), differences were found in the lobar distributions.

We observed the highest concentration of CMBs in the occipital lobes of patients with AD, which is consistent with the established topographic distribution of CMBs in older adults. [1; 2; 3; 4] CMBs that concentrate more in the posterior brain regions, particularly the occipital lobes, are thought to be associated with CAA. [2; 15; 16] Although we found the highest concentration of CMBs in the occipital lobes in patients with DLB, it is not possible to link the occipital CMB in patients with DLB to CAA, because distribution of CAA in DLB subjects (with or without AD co-pathology) has not been established.

Interestingly, patients with DLB had a higher concentration of CMBs not only in the occipital region, but also in the frontal lobe. High CMB load in the frontal lobes is consistent with a previous study [5], which reported a higher numbers of frontal CMB in patients with DLB compared to AD. However in contrast to our findings, occipital lobe CMB involvement was less than frontal lobe involvement in DLB patients.[5] This discrepancy may be due to our use of CMB densities in each lobe, normalizing the counts with the lobar volumes. Reporting CMB counts rather than densities in two regions that differ in volume may be misleading. Another possible explanation to the discrepancies could be the variability due to the small sample size in both studies.

In individuals with CAA, lobar CMBs tend to be located in the posterior brain regions. A high occipital CMB density in AD patients supports the hypothesis that CAA is one of the underlying pathologies associated with the occipital CMBs in AD. [2] However, the distribution of CAA in patients with DLB with or without additional AD pathology has not been established. Therefore it is not possible to explain the higher occipital or frontal lobe CMB densities observed in patients with DLB with CAA. However, DLB patients are characterized by Aβ deposition in the frontal lobes on PET imaging, [11] and CMB is associated with Aβ deposition.[1; 3] Therefore CMBs in DLB may be associated with the increased vascular permeability during Aβ clearance, implicated for amyloid related imaging abnormalities (ARIA) in AD immunotherapy trials[17]

In the current study none of the DLB patients had CMBs in the deep or infratentorial regions. While this could be due to the limitations of our sample size, CMBs located in the deep or infratentorial regions were associated with cardiovascular risk factors, presence of lacunar infarcts and white matter hyperintensities suggesting hypertensive and atherosclerotic microangiopathy is the underlying etiology. [18] Based on the absence of deep or infratentorial CMBs in the current study, hypertensive and atherosclerotic microangiopathy is less likely to be contributing to CMB pathophysiology in DLB than in AD. Interestingly DLB patients in the current study were less likely to report hypertension in their clinical history (32%) than AD (54%), however this difference did not reach statistical significance (p=0.08).

The main limitation of our study is the relatively small sample size therefore the findings need to be confirmed in a larger cohort. Furthermore, the cases were not pathologically confirmed to have LB disease and AD pathology. A high frequency of CMBs in patients with DLB has important therapeutic implications. High numbers of CMBs increase the risk of ARIA with vasogenic edema and effusions (ARIA-E) in amyloid-modifying immunotherapies [19; 20]. Patients with DLB with high Aβ load are candidates for such therapies however; they may be at risk for ARIA-E as much as patients with AD. Furthermore, CMBs have to be considered before starting anticoagulation therapy to elderly adults with dementia because of the higher risk of further brain hemorrhage. Understanding the pathophysiology of cerebral CMB in patients with DLB would help with decisions on such therapeutic approaches in DLB patients.

Highlights.

Cerebral microbleeds (CMB) as common in dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) as in Alzheimer’s disease (AD)

Highest CMB densities were observed in the occipital lobes,

CMB densities were lower in the deep/infratentorial region and temporal lobes in DLB compared to AD

Acknowledgments

Funding: Financial support for the conduct of the research was provided by the NIH (R01 AG040042, P50 AG016574, R01 AG11378) the Mangurian Foundation for Lewy body research, and the Robert H. and Clarice Smith and Abigail Van Buren Alzheimer s Disease Research Program. Sponsors did not have any role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Abbreviations

- DLB

dementia with Lewy bodies

- AD

Alzheimer disease

- CAA

Cerebral amyloid angiopathy

- CMB

Cerebral Microbleed

- GRE

Gradient-recalled-echo MRI

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement:

Drs. Gungor, Sarro, Gunter, and Graff-Radford, Ms. Tosakulwong, Mr. Przybelski, and Ms. Zuk report no disclosures.

Dr. Boeve has served as an investigator for a clinical trial sponsored by GE Healthcare. He receives royalties from the publication of a book entitled Behavioral Neurology Of Dementia (Cambridge Medicine, 2009). He serves on the Scientific Advisory Board of the Tau Consortium. He receives research support from the NIH (U01 AG045390, U54 NS092089, P50 AG016574, UO1 AG006786, RO1 AG015866, RO1 AG032306, RO1 AG041797), and the Mangurian Foundation for Lewy body research.

Dr. Ferman is funded by the NIH (P50-AG16574/P1) and the Mangurian Foundation for Lewy body research

Dr. Smith is funded by the NIH (P50-AG16574).

Dr. Knopman serves as Deputy Editor for Neurology®; serves on a Data Safety Monitoring Board for Lundbeck Pharmaceuticals and for the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer’s Disease Treatment Unit. He is participating in clinical trials sponsored by Lilly Pharmaceuticals and TauRx Pharmaceuticals. He receives research support from the NIH.

Dr. Petersen serves on scientific advisory boards for Elan Pharmaceuticals, Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, and GE Healthcare and receives research support from the NIH (P50-AG16574 [PI] and U01-AG06786 [PI], R01-AG11378 [Co-I], and U01–24904 [Co-I]).

Dr. Jack serves as a consultant for Eli Lilly. He receives research funding from the National Institutes of Health (R01-AG011378, RO1-AG037551, U01-HL096917, U01-AG032438, U01-AG024904), and the Alexander Family Alzheimer’s Disease Research Professorship of the Mayo Foundation Family.

Dr. Kantarci serves on the data safety monitoring board for Pfizer Inc and Johnson Alzheimer Immunotherapy; serves on the data safety monitoring board for Takeda Global Research & Development Center, Inc; and she is funded by the NIH (R01AG040042, P50 AG44170, P50 AG16574, U19 AG10483, U01 AG042791) and Minnesota Partnership for Biotechnology and Medical Genomics (PO03590201).

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kantarci K, Gunter JL, Tosakulwong N, Weigand SD, Senjem MS, Petersen RC, Aisen PS, Jagust WJ, Weiner MW, Jack CR., Jr Focal hemosiderin deposits and beta-amyloid load in the ADNI cohort. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9:S116–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pettersen JA, Sathiyamoorthy G, Gao FQ, Szilagyi G, Nadkarni NK, St George-Hyslop P, Rogaeva E, Black SE. Microbleed topography, leukoaraiosis, and cognition in probable Alzheimer disease from the Sunnybrook dementia study. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:790–5. doi: 10.1001/archneur.65.6.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yates PA, Sirisriro R, Villemagne VL, Farquharson S, Masters CL, Rowe CC. Cerebral microhemorrhage and brain beta-amyloid in aging and Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2011;77:48–54. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318221ad36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nagasawa J, Kiyozaka T, Ikeda K. Prevalence and clinicoradiological analyses of patients with Alzheimer disease coexisting multiple microbleeds. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2014;23:2444–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2014.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fukui T, Oowan Y, Yamazaki T, Kinno R. Prevalence and clinical implication of microbleeds in dementia with lewy bodies in comparison with microbleeds in Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra. 2013;3:148–60. doi: 10.1159/000351423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Charidimou A, Gang Q, Werring DJ. Sporadic cerebral amyloid angiopathy revisited: recent insights into pathophysiology and clinical spectrum. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012;83:124–37. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2011-301308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cordonnier C, Al-Shahi Salman R, Wardlaw J. Spontaneous brain microbleeds: systematic review, subgroup analyses and standards for study design and reporting. Brain. 2007;130:1988–2003. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greenberg SM, Vernooij MW, Cordonnier C, Viswanathan A, Al-Shahi Salman R, Warach S, Launer LJ, Van Buchem MA, Breteler MM. Cerebral microbleeds: a guide to detection and interpretation. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:165–74. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70013-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burack MA, Hartlein J, Flores HP, Taylor-Reinwald L, Perlmutter JS, Cairns NJ. In vivo amyloid imaging in autopsy-confirmed Parkinson disease with dementia. Neurology. 2010;74:77–84. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c7da8e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edison P, Rowe CC, Rinne JO, Ng S, Ahmed I, Kemppainen N, Villemagne VL, O’Keefe G, Nagren K, Chaudhury KR, Masters CL, Brooks DJ. Amyloid load in Parkinson’s disease dementia and Lewy body dementia measured with [11C]PIB positron emission tomography. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 2008;79:1331–8. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.127878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kantarci K, Lowe VJ, Boeve BF, Weigand SD, Senjem ML, Przybelski SA, Dickson DW, Parisi JE, Knopman DS, Smith GE, Ferman TJ, Petersen RC, Jack CR., Jr Multimodality imaging characteristics of dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurobiology of aging. 2012;33:2091–105. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McKeith IG, Dickson DW, Lowe J, Emre M, O’Brien JT, Feldman H, Cummings J, Duda JE, Lippa C, Perry EK, Aarsland D, Arai H, Ballard CG, Boeve B, Burn DJ, Costa D, Del Ser T, Dubois B, Galasko D, Gauthier S, Goetz CG, Gomez-Tortosa E, Halliday G, Hansen LA, Hardy J, Iwatsubo T, Kalaria RN, Kaufer D, Kenny RA, Korczyn A, Kosaka K, Lee VM, Lees A, Litvan I, Londos E, Lopez OL, Minoshima S, Mizuno Y, Molina JA, Mukaetova-Ladinska EB, Pasquier F, Perry RH, Schulz JB, Trojanowski JQ, Yamada M. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: third report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2005;65:1863–72. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000187889.17253.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–44. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tzourio-Mazoyer N, Landeau B, Papathanassiou D, Crivello F, Etard O, Delcroix N, Mazoyer B, Joliot M. Automated anatomical labeling of activations in SPM using a macroscopic anatomical parcellation of the MNI MRI single-subject brain. Neuroimage. 2002;15:273–89. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Attems J, Jellinger KA, Lintner F. Alzheimer’s disease pathology influences severity and topographical distribution of cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Acta neuropathologica. 2005;110:222–31. doi: 10.1007/s00401-005-1064-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson KA, Gregas M, Becker JA, Kinnecom C, Salat DH, Moran EK, Smith EE, Rosand J, Rentz DM, Klunk WE, Mathis CA, Price JC, Dekosky ST, Fischman AJ, Greenberg SM. Imaging of amyloid burden and distribution in cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Ann Neurol. 2007;62:229–34. doi: 10.1002/ana.21164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sperling RA, Jack CR, Jr, Black SE, Frosch MP, Greenberg SM, Hyman BT, Scheltens P, Carrillo MC, Thies W, Bednar MM, Black RS, Brashear HR, Grundman M, Siemers ER, Feldman HH, Schindler RJ. Amyloid-related imaging abnormalities in amyloid-modifying therapeutic trials: Recommendations from the Alzheimer’s Association Research Roundtable Workgroup. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:367–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.05.2351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vernooij MW, van der Lugt A, Ikram MA, Wielopolski PA, Niessen WJ, Hofman A, Krestin GP, Breteler MM. Prevalence and risk factors of cerebral microbleeds: the Rotterdam Scan Study. Neurology. 2008;70:1208–14. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000307750.41970.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sperling R, Salloway S, Brooks DJ, Tampieri D, Barakos J, Fox NC, Raskind M, Sabbagh M, Honig LS, Porsteinsson AP, Lieberburg I, Arrighi HM, Morris KA, Lu Y, Liu E, Gregg KM, Brashear HR, Kinney GG, Black R, Grundman M. Amyloid-related imaging abnormalities in patients with Alzheimer’s disease treated with bapineuzumab: a retrospective analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11:241–9. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70015-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Werring DJ, Sperling R. Inflammatory cerebral amyloid angiopathy and amyloid-modifying therapies: variations on the same ARIA? Ann Neurol. 2013;73:439–41. doi: 10.1002/ana.23891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]