Abstract

Individuals suffering from an alcohol-use disorder (AUD) constitute a major health concern. Preclinical studies in our laboratory show that acute and chronic intraperitoneal (i.p.) administration of ivermectin (IVM) reduces alcohol intake and preference in mice. To enable clinical investigation to use IVM for the treatment of an AUD, development of an oral formulation that can be used in animals as well as long-term preclinical toxicology studies are required. The present work explores the use of a promising alternative dosage form of IVM, fast-dissolving oral films (Cure Pharmaceutical®), to test the efficacy and safety of oral IVM in conjunction with alcohol exposure. We tested the effect of IVM (0.21 mg) using a fast-dissolving oral film delivery method on reducing 10% v/v alcohol (10E) intake in female C57BL/6 mice using a 24-h access two-bottle choice paradigm for 6 weeks (5 days per week). Differences in ethanol intake, preference for ethanol, water intake, fluid intake, food intake, changes in mouse and organ weights, as well as histological changes to kidney, liver, and brain were analyzed. The IVM group drank significantly less ethanol over the 30-day period compared to the placebo (blank strip) and the no-treatment groups. Organ weights did not differ between the groups. Histological evaluation showed no differences in the brain and kidney between groups. In the liver, there was a slight increase in the incidence of microvesicular fatty and degenerative changes of the animals receiving the thin strips. No overt hepatocellular necrosis or perivascular inflammation was noted. Overall, these data support the use of this novel method of oral drug delivery for longer-term studies and should facilitate FDA required preclinical testing that is necessary to repurpose IVM for treatment of an AUD.

Keywords: medications development, alcoholism therapy, drug repositioning, drug delivery

Introduction

There is a large number of individuals suffering from an alcohol-use disorder (AUD) throughout the world (Bouchery, Harwood, Sacks, Simon, & Brewer, 2011; Grant et al., 2004; Harwood, 2000). This disorder is the third leading risk factor for premature death and disabilities and is responsible for 4% of all deaths (World Health Organization, 2011). In the United States, the costs associated with individuals suffering from an AUD account for nearly half of the total cost of untreated addiction, totaling over $185 billion annually (Research Society on Alcoholism, 2011). A significant portion of this cost is due to reduced, lost, and foregone earnings. The remainder of the cost comes from medical and treatment expenses, decline in workforce productivity, accidents, violence, and premature death. Despite the known harm caused by ethanol, current pharmacological treatment strategies are limited and have yielded only modest positive results, as indicated by the continued high prevalence of AUD. Although treatments for AUD have improved somewhat over the past two decades (Miller, Book, & Stewart, 2011), the continued high rate of AUD illustrates the need to develop new, more effective interventions.

Pharmacotherapies for AUD are used less often than psychosocial interventions (Fuller & Hiller-Sturmhöfel, 1999). However, without a pharmacological adjunct to psychosocial therapy, nearly three-quarters of patients resume drinking within 1 year (Johnson, 2008). The limited use of pharmacotherapy for AUD is due, in part, to the relative lack of options to successfully treat these disorders (Edlund, Booth, & Han, 2012). To address this issue, our research group is investigating the utility of ivermectin (IVM) as a novel pharmacotherapy for the treatment and/or prevention of AUD (Asatryan et al., 2014; Wyatt et al., 2014; Yardley et al., 2012, 2014).

IVM is a broad-spectrum antiparasitic avermectin (Geary, 2005; Molinari, Soloneski, & Larramendy, 2010; Richard-Lenoble, Chandenier, & Gaxotte, 2003). The current therapeutic potential of IVM is attributed to action on a non-mammalian, glutamate-gated inhibitory chloride channel (Cully et al., 1994; Dent, Davis, & Avery, 1997; Vassilatis et al., 1997). Studies in humans and rodents suggest additional sites of action for IVM not related to these receptors (Sung, Huang, Fan, Lin, & Lin, 2009), including nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) (Krause et al., 1998; Sattelle et al., 2009) and P2X4 purinergic receptors (P2X4Rs) (Asatryan et al., 2010; Wyatt et al., 2014).

Among P2XR family members, IVM is a selective positive modulator of P2X4Rs and has been used to differentiate the role of P2X4Rs from other P2X family members in ATP-mediated processes (Jelinková et al., 2006; Khakh, Proctor, Dunwiddie, Labarca, & Lester, 1999; Silberberg, Li, & Swartz, 2007). Studies from our laboratory using two-electrode voltage clamp methods demonstrate that IVM interferes with and antagonizes the inhibitory effect of ethanol on P2X4Rs (Asatryan et al., 2010). Furthermore, we have shown that IVM decreases ethanol consumption across multiple murine models of ethanol intake (Asatryan et al., 2014; Wyatt et al., 2014; Yardley et al., 2012, 2014) and reduces response for alcohol under an operant self-administration progressive ratio schedule (Kosten, 2011). We found that both acute and multi-day administration of IVM (1.25–10 mg/kg) reliably decreases ethanol intake and preference (Yardley et al., 2012, 2014) without causing overt signs of toxicity and having minimal effect on major domains of neuropsychiatric toxicity (Bortolato et al., 2013). In these aforementioned studies, administration of IVM was achieved using an intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection method.

For translation of a drug from the pre-clinical to clinical arena, efficacy and subsequent safety studies must be performed using the intended clinical route of administration, and it is important that methods used in rodents for such evaluations provide reliable and reproducible results. Current methods of oral delivery, including oral gavage (Brown, Dinger, & Levin, 2000; Germann & Ockert, 1994; Zhang, 2011), peanut butter mixture (Silverman, Oliver, Karras, Gastrell, & Crawley, 2013), gelatin molds (Froehlich, Hausauer, Federoff, Fischer, & Rasmussen, 2013), adding the drug to drinking water or a sucrose solution, and using pre-mixed drug-chocolate pellets (Zhang, 2011), all have significant limitations that can jeopardize the reliability of the data. Taken together, the disadvantages associated with the current methods of drug delivery have prompted interest in developing alternative methods to improve oral delivery in rodents, such as pre-coating the gavage needle with sucrose (Hoggatt et al., 2010).

Fast-dissolving oral films represent another alternative approach for the oral delivery of a drug (for review, see Bala, Pawar, Khanna, & Arora, 2013; Ghodake et al., 2013; Mandeep, Rana, & Nimrata, 2013; Panda, Dey, & Rao, 2012; Saini, Kumar, Sharma, & Visht, 2012). At the present time, the majority of research on the use of fast-dissolving oral films is focused on humans. However, some of the noted benefits are also applicable in preclinical drug delivery studies. For example, fast-dissolving oral films provide a safe passage of oral delivery compared to intragastric oral gavage and offer a less stressful drug delivery experience for the animal.

The present study tests the hypothesis that 0.21 mg IVM, the highest dose tested in previous IVM studies conducted by our laboratory, administered via fast-dissolving oral films, is able to decrease ethanol intake in mice over a 30-day period using a 24-h two-bottle choice paradigm without causing significant pathological changes in the kidney, liver, and brain. Importantly, this study represents the first long-term ethanol/IVM administration study, which is essential if IVM is to be repurposed as a pharmacotherapy for AUD.

Materials and methods

Animals

Studies were performed on drug-naïve C57BL/6 female mice that were approximately 10–12 weeks old at the time of testing, obtained from our internal breeding colony at the University of Southern California (USC). Prior to initiating the study, mice were transferred to the testing room and remained group-housed with 3–5 mice per cage for 1 week. Mice were then single-housed in polycarbonate/polysulfone cages on a 12-h reverse light/dark cycle with lights off at 12:00 noon. The holding room was maintained at approximately 22 °C. All procedures in this study were performed in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and all efforts were made to minimize animal suffering. The USC Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved the protocols.

Drugs

Fast-dissolving oral films containing 6 mg of IVM were kindly provided by Cure Pharmaceutical (Oxnard, CA). The film was cut up into smaller sections using a standard single quarter-inch hole-punch to produce pieces containing approximately 0.21 mg IVM each. Ethanol (190 proof USP, Sigma, USA) was diluted in water to achieve a 10% v/v solution (10E). Sucrose (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was diluted in water to achieve a 4.25 % w/v solution.

Alcohol Intake Study

The 24-h access two-bottle choice paradigm was performed as previously described (Asatryan et al., 2014; Wyatt et al., 2014; Yardley et al., 2012, 2014). Briefly, mice were single-housed and had access to 2 bottles of water for 3 days. Then, one bottle of water was replaced with a bottle of 10E. After 10 days, when drinking stabilized (± 10% variability from the mean dose of the previous 3 days), mice were assigned to drug treatment groups so that the average 10E intake on day 10 of exposure to ethanol was similar across groups. There were 3 groups: the IVM group which was administered key lime-flavored oral film with 0.21 mg of IVM (n = 8), the placebo group which was administered key lime-flavored oral film with no drug (n = 8), and the control group which was handled and presented with the gavage needle dipped in the sucrose solution, but not given any oral film (n = 6). We used 0.21 mg because it correlated to the highest dose of IVM previously tested (i.e., 10 mg/kg in a 21-g mouse). Mice were treated for 30 days at 9:30 AM each day, 5 days per week (Monday–Friday) for 6 weeks. Animals continued receiving access to both water and alcohol over the weekend, but animals were not treated and fluid volumes were not measured on these days. Fluid volumes, food weights, and mouse weights were recorded immediately prior to treatment. Bottles were alternated every other day to avoid side preferences. Strips were administered using an animal-feeding needle (Cadence Science, Staunton, VA) dipped in a 4.25% sucrose solution to serve as an adhesive for the film strip. As illustrated in Fig. 1, after being presented with the tip of the gavage needle, mice would self-administer the film.

Fig. 1. Method of oral film delivery.

Films were administered using an animalfeeding gavage needle dipped in a 4.25% sucrose solution. After being presented with the tip of the needle (as pictured), mice would self-administer the films.

Analysis of organ tissue samples

The day following the last dose of IVM, 4 animals from the IVM group, 4 from the placebo group, and 3 from the control group were euthanized. Brains, livers, and kidneys were harvested and weighed for each animal (µg). Tibia length was then measured (mm). Organ weights were normalized to tibia length to correct for age, because body weights are susceptible to factors other than drug treatment, in this case, 10E intake. One-way ANOVAs were used to analyze the ratio of organ weights to tibia length. Organs were then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich) for 24 h and dehydrated in 70% ethanol (Koptec) for another 24 h. Tissues were embedded in paraffin, and 4-µm sections were cut from each block and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (both from Sigma-Aldrich). Photographs were taken at 40× magnification and these photographs were analyzed for histopathological changes by an investigator blind to the experimental group. If observed, the alteration was identified and scored as mild, moderate, or severe.

Data analyses

Ethanol dose (g/kg) and preference for ethanol ([mL ethanol/total mL] × 100) were calculated daily. The dependent variables included 10E intake (g/kg), 10E preference (%), water (mL), total fluid intake (mL), food intake (g), and change in mouse weight (g). Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) assessed the effect of 30-day IVM administration with time (day of IVM administration) as the repeated-measures factor on the dependent variables. As previously stated, fluid volumes were measured Monday–Friday immediately prior to treatment. Therefore, although mice were treated for 30 days, values for dependent variables could only be calculated Monday–Thursday because no reading was obtained on Saturday, preventing values from Friday from being calculated. Due to a measurement error, 2 food intake values were removed from the analysis and therefore, the food intake was not analyzed using repeated measures. Significant main effects and interactions of the ANOVAs were further investigated with Tukey post hoc tests. The significance level was set at p ≤ 0.05. Spearman Rank Correlation was used to test for correlation between 10E intake and food intake with p ≤ 0.05.

Results

Alcohol intake study

We tested the effect of 30–day administration of IVM (0.21 mg) via fast-dissolving oral films using a 24-h access two-bottle choice alcohol paradigm in female C57BL/6 mice. On the day prior to treatment, there was no significant difference in the average 10E intake for IVM, placebo, and control groups (i.e., IVM: 14.74 ± 3.14; placebo: 14.74 ± 3.56; and controls: 14.71 ± 2.75 g/kg/24-h). We tested the effect of IVM on 10E intake over the 30-day period (Fig. 2A). When the analysis was conducted across the 30-day treatment time period we found that IVM significantly reduced ethanol intake compared to placebo and control groups [F(2,19) = 16.23, p < 0.001]. When the analysis was conducted across time, there was a significant effect on 10E intake [F(23,437) = 2.893, p < 0.001]. The interaction between group and day, however, was not significant.

Fig. 2. IVM, delivered via fast-dissolving oral film, significantly reduces 10E intake in female C57BL/6 mice.

The graphs illustrate the effects of IVM (0.21 mg; black) compared to placebo (blue) and control (red) groups using 24-h access two-bottle choice paradigm for (a) 10E intake, (b) preference for 10E, (c) water intake, (d) total fluid intake, (e) change in mouse weight, and (f) food intake. The insets represent the average over the 30-day period for control (red), placebo (blue), and IVM (black) groups. Values represent the mean ± SEM for 6–8 female mice/group. *p < 0.05 IVM vs. placebo; **p < 0.01 IVM vs. placebo; ***p < 0.001 IVM vs. placebo; +p < 0.05 IVM vs. control; ++p < 0.01 IVM vs. control.

10E preference was also significantly lower in the IVM group across the 30-day period when the analysis was conducted across treatment [F(2,19) = 17.00, p < 0.001] (Fig. 2B). There was no significant effect on preference when analyzed across time. Furthermore, no significant interaction between time and treatment was observed.

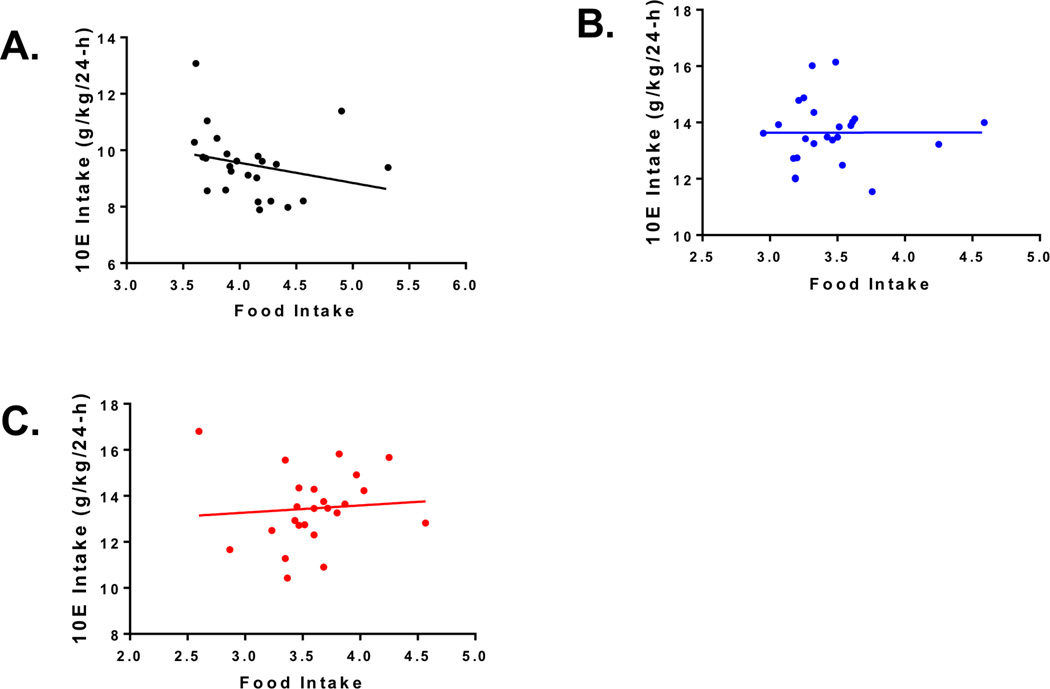

In addition, we found that IVM significantly increased water intake [F(2,19) = 12.29, p < 0.01] when analyzed across treatment, but there was no significant main effect of time on water intake (Fig. 2C) and there was no significant interaction between treatment and time. There was no main effect of treatment on total fluid intake, but there was a significant main effect when the analysis was conducted across time [F(23,437) = 4.40, p < 0.001] (Fig. 2D). No significant interaction between treatment and time was observed. Finally, there was no significant main effect of treatment or time on change in body weight (Fig. 2E). However, IVM did significantly increase food intake when the analysis was conducted across treatment [F(2,454) = 51.1, p < 0.001] (Fig. 2F). There was a significant main effect of time to significantly alter food intake when the analysis was conducted across time [F(23,454) = 6.56, p < 0.001], but no significant interaction between treatment and time. Interestingly, there was a significant negative correlation between alcohol intake and food intake in the IVM group (p = 0.025; Fig 3A) but not in the placebo (Fig. 3B) or control group (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3. Decrease in ethanol intake correlates with increase in food intake.

The graphs illustrate the relationship between ethanol intake and food intake for the three groups: IVM (black, R2 = 0.207, p = 0.025), placebo (blue, R2 = 0.00706, p = 0.697), and control (red, R2 = 0.0864, p = 0.164).

Organ weight and histology study

At necropsy, brain, right kidney, and liver were harvested from animals from each treatment group and weighed. No differences were seen in the organ weights (Table 1). Sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin were analyzed for possible histopathological changes. No changes were observed on the histological appearance of the brain or kidney tissue (Fig. 4). We did observe slight, diffuse microvesicular fatty changes and degeneration in the liver, but this most likely was due to the alcohol intake of the animals (Table 2). The incidence of these observations were increased slightly in the animals that received thin strips, but it was considered to be due to a combination of increased caloric and fat intake associated with this treatment.

Table 1.

The organ weights collected during necropsy were normalized to tibia length (µg/mm)

| Control (µg/mm) | Placebo (µg/mm) | IVM (µg/mm) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liver | 51.614 | 35.342 | 55.404 |

| 54.753 | 57.945 | 53.532 | |

| 51.926 | 59.537 | ||

| 48.757 | 48.970 | ||

| Average +/− SEM | 53.184 +/− 1.570 | 48.493 +/− 4.780 | 54.361 +/− 2.191 |

| Right Kidney | 6.743 | 6.627 | 8.000 |

| 8.423 | 8.508 | 8.645 | |

| 6.485 | 8.546 | 7.511 | |

| 8.675 | 7.647 | ||

| Average +/− SEM | 7.217 +/− 0.608 | 8.089 +/− 0.489 | 7.951 +/− 0.253 |

| Brain | 21.928 | 21.199 | 22.622 |

| 22.958 | 23.995 | 21.139 | |

| 21.036 | 22.836 | 21.743 | |

| 21.340 | 21.648 | ||

| Average +/− SEM | 21.974 +/− 0.555 | 22.343 +/− 0.664 | 21.788 +/− 0.308 |

No significant differences were observed in the weight for brain, liver, and right kidney. These same organs were used for histopathological analysis.

Fig. 4.

Representative histological micrographs of brain, liver, and kidney tissue for each experimental group (i.e., control, placebo, and IVM).

Table 2.

Histopathological analysis of liver sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin

| Group | Score per micrograph | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Control | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Placebo | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Placebo | 0 | 1 | 1* |

| Placebo | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Placebo | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| IVM | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| IVM | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| IVM | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| IVM | 1 | 1* | 1 |

Three images were taken from each liver section for analysis. A score of 1 indicates that the animals had slight liver changes consistent with alcohol intake. A score of zero indicates that no change was observed. Two animals had slight inflammation observed (marked by *).

Discussion

AUD is a chronic disorder and it is unlikely that acute treatment of IVM would be sufficient to successfully treat patients suffering from this disorder. As such, the present study tested the hypothesis that IVM (0.21 mg), administered via fast-dissolving oral films, is able to significantly decrease 10E intake in mice over a 30-day period using the 24-h access two-bottle choice paradigm. The significant reduction in both 10E intake and preference compared to placebo and control groups supports the hypothesis and adds to the evidence that IVM can be developed for the prevention and/or treatment of AUD. Furthermore, histological evaluation showed no significant differences in the brain and kidney between groups. No overt hepatocellular necrosis or perivascular inflammation was noted in the liver, suggesting prolonged use of IVM is well tolerated. However, further evaluation is needed to support these observations.

In this study, we found that the IVM-treated group consumed a significantly greater amount of water compared to placebo and control groups. This increase in water intake may be compensation for the significant decrease in 10E intake. In support of this notion, the total fluid intake among the 3 groups was similar. Moreover, there was no significant difference in body weight change between the 3 groups, but interestingly, the IVM group consumed significantly more food. The significant negative correlation between alcohol intake and food intake in the IVM group suggests that the increased food intake is an attempt to counteract the caloric loss resulting from the decreased 10E consumption. Interestingly, transient increases in 10E intake were observed throughout the study, but we did not observe any clear pattern of changes linked, for example, to occurring only on Mondays. Possible reasons for this fluctuation could be related to the method of drug delivery used (discussed below). Taken together, these data fit well with previously reported studies on the effect of IVM on alcohol intake.

Although the exact mechanism responsible for IVM’s effect on ethanol intake remains unknown, previous work from our laboratory supports a role of both P2X4Rs (Bortolato et al., 2013; Wyatt et al., 2014) and gamma-aminobutyric acid receptors (GABAARs) (Bortolato et al., 2013). Additionally, IVM has been reported to act on nAChRs (Krause et al., 1998; Sattelle et al., 2009), which are known to be important targets of ethanol (for review, see Chatterjee & Bartlett, 2010; Hendrickson, Guildford, & Tapper, 2013). Although clinical resistance to IVM, as an antiparasitic, after chronic administration has been reported (Currie, Harumal, McKinnon, & Walton, 2004), additional research in this area, in regard to its effects on alcohol intake, is warranted. The present study begins to explore this issue by testing the effects of chronic IVM administration on alcohol intake.

In addition to supporting the use of chronic IVM administration for the treatment of AUD, this study also supports the use of fast-dissolving oral films as a method for chronic drug delivery in rodents. For example, intragastric gavage is a commonly used drug delivery technique in rodents when testing chronically. Several studies, however, have shown that gavage of certain vehicles can actually increase stress response in male CD rats (Brown et al., 2000). Furthermore, data from a 2-year gavage carcinogenicity study conducted in Fischer 344 rats suggest that the high mortality rate observed was partially due to chronic irritation caused by repeated intragastric gavage (Germann & Ockert, 1994). Similarly, repeated dosing using this method has been shown to cause respiratory interference and abdominal distension, among other adverse events that can jeopardize the integrity of the study (Zhang, 2011). Taken together, these studies suggest that fast-dissolving oral films can provide a less stressful drug delivery experience compared to intragastric oral gavage.

Several study limitations should be noted. First, we did not monitor the estrous cycle in these mice. However, because we had both a control and placebo group, it is unlikely that the differences in 10E intake between the groups were due to changes in the estrous cycle. Another limitation for this study was related to the potential difference in actual dose delivered, because the dose given to each animal was constant at 0.21 mg and was not based on weight. Therefore, dosing likely fluctuated, to some extent, within the IVM group throughout the study. Furthermore, it was unclear if the mice were consuming the whole strip as delivered or if some of the strip dissolved prior to consumption. Next, partial buccal absorption that may have occurred based on the physical properties of the thin strip may have somewhat altered the day-to-day results. However, it is unlikely that any of these later three potential issues would have significantly altered the overall results, because we have previously reported a similar degree of reduction of ethanol intake when testing between 5.0–10 mg/kg of IVM (Yardley et al., 2012). Only female mice were tested in this study. As male and female mice exhibit different drinking behaviors, it will be important, in a future investigation, to also evaluate the effects of long-term IVM administration on alcohol intake in male mice. However, as male C57BL/6 mice consume lower levels of ethanol than females in the 24-h two-bottle choice model (Yardley et al., 2012), it is unlikely that we would find differences in organ toxicity from what we have reported in the current study. Finally, we only tested the highest dose of IVM used in previous studies from our laboratory to assess potential toxicities of the drug when administered in the presence of ethanol. It is very unlikely that a lower dose of IVM would lead to observable organ damage if the highest dose of IVM tested failed to do so.

We have shown that longer-term delivery of IVM resulted in a net reduction of 10E intake and preference across time without causing significant changes in organ morphology. Future studies should investigate the effect of chronic IVM administration in models of high alcohol intake (e.g., intermittent limited access or drinking in the dark paradigms). Moreover, additional studies are necessary to determine the pharmacokinetics (PK) of IVM delivered via fast-dissolving oral films to establish the concentration of IVM in the brain and plasma compared to levels obtained when IVM is administered via injection.

It is interesting to note that this dose is comparable to approximately a 10 mg/kg dose, the highest dose we tested i.p., which is more than three times the dose we are currently using in our clinical studies. The lack of pathological changes in the brain, kidney, and liver associated with IVM treatment suggest that long-term IVM administration can be tolerated, which is necessary if IVM is to be repositioned as a treatment for chronic disease such as AUD. Long-term studies with more power should be conducted before definitive conclusions can be drawn.

In conclusion, our data support the use of fast-dissolving oral films as an effective form of oral drug delivery in mice and the continued development of long-term use of IVM as a therapeutic agent for the prevention and/or treatment of AUD.

Highlights.

Ivermectin (IVM; 0.21 mg) decreased alcohol intake over a 30 day period

IVM had no effect on the histological appearance of brain or kidney tissue

IVM did not cause hepatocellular necrosis or perivascular inflammation in liver

Oral films represent a promising method for chronic drug delivery in rodents

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by research grants SC CTSI NIH/NCRR/NCATS -- TL1TR000132 (M.M.Y.) and UL1TR000130 (D.L.D.), AA022448 (D.L.D.), and the USC School of Pharmacy.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

DLD is an inventor on a patent for the use of IVM for the treatment of alcohol-use disorders. The authors have no other conflict of interest and are entirely responsible for the scientific content of the paper.

References

- Asatryan L, Popova M, Perkins D, Trudell JR, Alkana RL, Davies DL. Ivermectin antagonizes ethanol inhibition in purinergic P2X4 receptors. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2010;334:720–728. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.167908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asatryan L, Yardley MM, Khoja S, Trudell JR, Hyunh N, Louie SG, et al. Avermectins differentially affect ethanol intake and receptor function: implications for developing new therapeutics for alcohol use disorders. The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;17:907–916. doi: 10.1017/S1461145713001703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bala R, Pawar P, Khanna S, Arora S. Orally dissolving strips: A new approach to oral drug delivery system. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Investigation. 2013;3:67–76. doi: 10.4103/2230-973X.114897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bortolato M, Yardley MM, Khoja S, Godar SC, Asatryan L, Finn DA, et al. Pharmacological insights into the role of P2X4 receptors in behavioural regulation: lessons from ivermectin. The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;16:1059–1070. doi: 10.1017/S1461145712000909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchery EE, Harwood HJ, Sacks JJ, Simon CJ, Brewer RD. Economic costs of excessive alcohol consumption in the U.S., 2006. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2011;41:516–524. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AP, Dinger N, Levine BS. Stress produced by gavage administration in the rat. Contemporary Topics in Laboratory Animal Science. 2000;39:17–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee S, Bartlett SE. Neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors as pharmacotherapeutic targets for the treatment of alcohol use disorders. CNS & Neurological Disorders Drug Targets. 2010;9:60–76. doi: 10.2174/187152710790966597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cully DF, Vassilatis DK, Liu KK, Paress PS, Van der Ploeg LH, Schaeffer JM, et al. Cloning of an avermectin-sensitive glutamate-gated chloride channel from Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1994;371:707–711. doi: 10.1038/371707a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currie BJ, Harumal P, McKinnon M, Walton SF. First documentation of in vivo and in vitro ivermectin resistance in Sarcoptes scabiei. Clinical Infectious Disease. 2004;39:e8–e12. doi: 10.1086/421776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dent JA, Davis MW, Avery L. avr-15 encodes a chloride channel subunit that mediates inhibitory glutamatergic neurotransmission and ivermectin sensitivity in Caenorhabditis elegans. The EMBO Journal. 1997;16:5867–5879. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.19.5867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edlund MJ, Booth BM, Han X. Who seeks care where? Utilization of mental health and substance use disorder treatment in two national samples of indviduals with alcohol use disorders. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2012;73:635–646. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froehlich JC, Hausauer BJ, Federoff DL, Fischer SM, Rasmussen DD. Prazosin reduces alcohol drinking throughout prolonged treatment and blocks the initiation of drinking in rats selectively bred for high alcohol intake. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2013;37:1552–1560. doi: 10.1111/acer.12116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller RK, Hiller-Sturmhöfel S. Alcoholism treatment in the United States. An overview. Alcohol Research & Health. 1999;23:69–77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geary TG. Ivermectin 20 years on: maturation of a wonder drug. Trends in Parasitology. 2005;21:530–532. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2005.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germann PG, Ockert D. Granulomatous inflammation of the oropharyngeal cavity as a possible cause for unexpected high mortality in a Fischer 344 rat carcinogenicity study. Laboratory Animal Science. 1994;44:338–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghodake PP, Karande KM, Osmani RA, Bhosale RR, Harkare BR, Kale BB. Mouth Dissolving Films: Innovative Vehicle for Oral Drug Delivery. International Journal of Pharma Research & Review. 2013;2:41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Pickering RP. The 12-month prevalence and trends in DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: United States, 1991–1992 and 2001–2002. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004;74:223–234. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harwood H. Updating estimates of the economic costs of alcohol abuse in the United States: Estimates, update methods, and data. NIAAA Newsletter. 2000 http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/economic-2000/alcoholcost.PDF.

- Hendrickson LM, Guildford MJ, Tapper AR. Neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: common molecular substrates of nicotine and alcohol dependence. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2013;4:29. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoggatt AF, Hoggatt J, Honerlaw M, Pelus LM. A spoonful of sugar helps the medicine go down: a novel technique to improve oral gavage in mice. Journal of the American Association for Laboratory Animal Science. 2010;49:329–334. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jelinková I, Yan Z, Liang Z, Moonat S, Teisinger J, Stojilkovic SS, et al. Identification of P2X4 receptor-specific residues contributing to the ivermectin effects on channel deactivation. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2006;349:619–625. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.08.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BA. Update on neuropharmacological treatments for alcoholism: Scientific basis and clinical findings. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2008;75:34–56. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khakh BS, Proctor WR, Dunwiddie TV, Labarca C, Lester HA. Allosteric control of gating and kinetics at P2X(4) receptor channels. The Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;19:7289–7299. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-17-07289.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosten TA. Pharmacologically targeting the P2rx4 gene on maintenance and reinstatement of alcohol self-administration in rats. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 2011;98:533–538. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2011.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause RM, Buisson B, Bertrand S, Corringer PJ, Galzi JL, Changeux JP, et al. Ivermectin: a positive allosteric effector of the alpha7 neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Molecular Pharmacology. 1998;53:283–294. doi: 10.1124/mol.53.2.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandeep K, Rana AC, Nimrata S. Fast dissolving films: An innovative drug delivery system. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Research and Allied Sciences. 2013;2:14–24. [Google Scholar]

- Miller PM, Book SW, Stewart SH. Medical treatment of alcohol dependence: a systematic review. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 2011;42:227–266. doi: 10.2190/PM.42.3.b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molinari G, Soloneski S, Larramendy ML. New ventures in the genotoxic and cytotoxic effects of macrocyclic lactones, abamectin and ivermectin. Cytogenetic and Genome Research. 2010;128:37–45. doi: 10.1159/000293923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panda BP, Dey NS, Rao MEB. Development of Innovative Orally Fast Disintegrating Film Dosage Forms: A Review. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Nanotechnology. 2012;5:1666–1674. [Google Scholar]

- Research Society on Alcoholism. Impact of alcoholism and alcohol induced disease on America. 2011 from http://www.rsoa.org/2011-04-11RSAWhitePaper.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Richard-Lenoble D, Chandenier J, Gaxotte P. Ivermectin and filariasis. Fundamental & Clinical Pharmacology. 2003;17:199–203. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-8206.2003.00170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saini P, Kumar A, Sharma P, Visht S. Fast Disintegrating Oral Films: A Recent Trend of Drug Delivery. International Journal of Drug Development and Research. 2012;4:80–94. [Google Scholar]

- Sattelle DB, Buckingham SD, Akamatsu M, Matsuda K, Pienaar IS, Jones AK, et al. Comparative pharmacology and computational modelling yield insights into allosteric modulation of human alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2009;78:836–843. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silberberg SD, Li M, Swartz KJ. Ivermectin interaction with transmembrane helices reveals widespread rearrangements during opening of P2X receptor channels. Neuron. 2007;54:263–274. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman JL, Oliver CF, Karras MN, Gastrell PT, Crawley JN. AMPAKINE enhancement of social interaction in the BTBR mouse model of autism. Neuropharmacology. 2013;64:268–282. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung YF, Huang CT, Fan CK, Lin CH, Lin SP. Avermectin intoxication with coma, myoclonus, and polyneuropathy. Clinical Toxicology (Philadelphia, Pa.) 2009;47:686–688. doi: 10.1080/15563650903070901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassilatis DK, Arena JP, Plasterk RH, Wilkinson HA, Schaeffer JM, Cully DF, et al. Genetic and biochemical evidence for a novel avermectin-sensitive chloride channel in Caenorhabditis elegans: Isolation and characterization. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:33167–33174. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.52.33167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global status report on alcohol and health. 2011:1–286.

- Wyatt LR, Finn DA, Khoja S, Yardley MM, Asatryan L, Alkana RL, et al. Contribution of P2X4 receptors to ethanol intake in male C57BL/6 mice. Neurochemical Research. 2014;3:1127–1139. doi: 10.1007/s11064-014-1271-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yardley M, Wyatt L, Khoja S, Asatryan L, Ramaker MJ, Finn DA, et al. Ivermectin reduces alcohol intake and preference in mice. Neuropharmacology. 2012;63:190–201. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yardley MM, Neely M, Huynh N, Asatryan L, Louie SG, Alkana RL, et al. Multiday administration of ivermectin is effective in reducing alcohol intake in mice at doses shown to be safe in humans. Neuroreport. 2014;25:1018–1023. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0000000000000211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L. Voluntary oral administration of drugs in mice. Protocol Exchange. 2011 http://www.nature.com/protocolexchange/protocols/2099. [Google Scholar]