Abstract

JC virus (JCV) is highly prevalent in humans, and may cause progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), JCV granule cell neuronopathy (JCV GCN), JCV encephalopathy (JCVE) and JCV meningitis (JCVM) in immunocompromised individuals. There is no treatment for JCV, and a growing number of multiple sclerosis patients treated with immunomodulatory medications have developed PML. Antiviral agents against JCV are therefore highly desirable but remain elusive, due to the difficulty of determining their effect in vitro. A JCV strain carrying a fluorescent protein gene would greatly simplify and accelerate the drug screening process. To achieve this goal, we selected the 366 bp improved Light, Oxygen or Voltage-sensing domain (iLOV) of plant phototropin gene and created two full-length JCV-iLOV constructs on the prototype JCV Mad1 backbone. The iLOV gene was inserted either before the early regulatory T gene (iLOV-T), or after the late Agno gene (iLOV-Agno). Both JCV iLOV strains were replication-competent in vitro and emitted a fluorescent signal detectable by confocal microscope, but JCV iLOV-T exhibited higher cellular and supernatant viral loads compared to JCV iLOV-Agno. JCV iLOV-T could also produce infectious pseudovirions. These data suggest that JCV iLOV constructs may become valuable tools for anti-JCV drug screening.

Keywords: JC virus, iLOV, drug screening, therapy, PML

Introduction

JC virus (JCV) is a prevalent polyomavirus in human populations. Seroprevalence varies from 39% to 91% depending on assays and cohorts (Antonsson et al., 2010; Egli et al., 2009; Kean et al., 2009; Matos et al., 2010). The virus remains quiescent in most healthy individuals without causing clinically-apparent disease. However it can reactivate in the setting of immunosuppression and cause devastating diseases of the CNS including progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) (Gheuens et al., 2013; Wollebo et al., 2015), JCV granule cell neuronopathy (JCV GCN) (Dang and Koralnik, 2013; Koralnik et al., 2005), JCV encephalopathy (JCVE) (Dang et al., 2012b; Wuthrich et al., 2009) and JCV meningitis (JCVM) (Agnihotri et al., 2014) for which there is no cure. Limitations preventing the development of novel therapies for JCV include the lack of an animal model and difficulties to determine antiviral activity of potential drugs in vitro. Current techniques consist of measurement of JC viral load in cells and supernatant as well as expression of JCV VP1 protein, which are labor intensive and require harvesting of samples at various time points. Hence, a fast and convenient viral load detection method would greatly expedite the screening process. Fluorescent tagging of JC virions has been previously used (O'Hara et al., 2014; Yatawara et al., 2015) to screen small-molecule entry inhibitor of JCV infection. However, this method is not appropriate for screening of modulators of JCV replication. We therefore developed JCV constructs containing a fluorescent reporter gene allowing for an expedited screen of anti-JCV agents.

Materials and Methods

1. Materials

Three improved Light, Oxygen or Voltage-sensing domain (iLOV) of plant phototropin gene sequences were kindly provided by Dr. John M. Christie from University of Glasgow (Chapman et al., 2008). Among the three iLOV genes, phiLOV 2.9 was selected and codon-optimized for human cell line expression.

2. Methods

2.1 iLOV-T construction

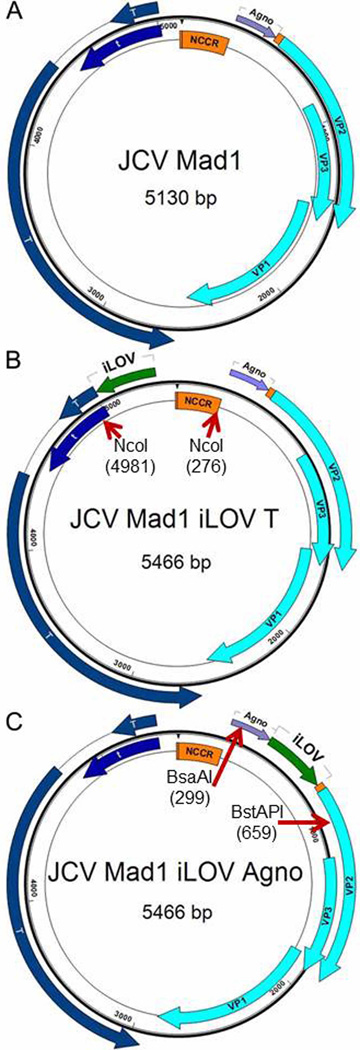

The iLOV-T construct was obtained by synthesis of a JCV Mad1 fragment from nt 4970 to 290, containing the reverse complement of codon-optimized iLOV gene at position 5013 (Invitrogen-now Thermo Fisher Scientific, Grand Island, NY 14072, USA). This fragment was digested with Nco1 and substituted for the JCV Mad1 wild-type fragment at the Nco1 sites at position 4981 and 276. The DNA sequence accuracy was verified by sequencing. The Genomic map of parental wild type JCV Mad1 and iLOV-T construct is shown in Fig. 1 panels A, B.

Fig. 1.

Genomic maps of parental JCV strain Mad1 and two improved Light, Oxygen and Voltage sensing domain of plant phototropin (iLOV) constructs: iLOV-Agno and iLOV-T. A: JCV Mad1. JCV Mad1 strain has 5130bp double stranded circular DNA genome which can be divided into non coding control region (NCCR) and coding regions. Coding sequences can be further divided into an early gene group which includes the T and t regulatory protein genes and a late gene group which includes the Agno protein and three viral protein (VP) genes - VP1, 2 and 3. There is a 33bp intercoding region between the end codon of the Agno gene and the start codon of VP2 gene. B: JCV iLOV-T. This construct has a 5466bp genome, as a result of inserting a 336bp improved iLOV gene at position 5013 before the start codon of T gene. The iLOV gene has been optimized for expression in human cell lines. C: JCV iLOV-Agno. This construct has a 5466bp genome, as a result of inserting the 336bp iLOV gene right after the end codon of Agno gene.

2.2 iLOV-Agno construction

The iLOV-Agno construct was obtained by synthesis of a JCV Mad1 fragment from nt 290 to 670, containing the codon-optimized iLOV gene at position 493. This fragment was digested with BsaAI and BstAPI and substituted for the JCV Mad1 wild-type fragment at the BsaAI and BstAPI sites at position 299 and 659. The DNA sequence accuracy was verified by sequencing. The Genomic map of iLOV-Agno is shown in Fig. 1 panel C.

2.3 Viral replication kinetic studies

JCV Mad1 and two iLOV mutants were transfected to 293FT cells. Cells and supernatant were harvested twice a week and DNA was digested with DpnI to remove input plasmid. The JC viral load was then measured by QPCR targeting a region of the VP2 gene, as previously described (Dang et al., 2012a).

2.4 Detection of iLOV signal by confocal fluorescent microscope

293FT cells were grown to 80% confluency in non-fluorescence glass bottom 6-well plate (MatTeK, 200 Homer Ave, Ashland, MA 01721, USA) before transfection with JCV strains. iLOV observation was made 5 days post transfection using an Olympus reversible confocal microscope FV-1100. To detect the iLOV signal, the excitation was set to 450nm as described previously (Chapman et al., 2008) and the emission to 490 nm.

2.5 Detection of JC VP1 protein by intracellular staining (ICS)

293FT cells were transfected or infected with JCV Mad1 or iLOV-constructs: Lab-Tek II (Thermo Fisher Scientific) chamber slides were first treated with 1ml 0.01% Poly-L-ornithine solution (Sigma Adlrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) at 37°C for 1 hr. Poly-L-ornithine solution was removed and slides were rinsed three times with sterile Milli Q water (filtered with 0.2um filter unit). After the final rinse, chamber slides were coated with 1ml 5µg/ml laminin solution (VWR International LLC, 47743-734, Radnor Corporate Center, Building One, Suite 200, P.O. Box 6660, 100 Matsonford Road, Radnor, PA 19087-8660, USA), at 37°C for 1 hr and slides were rinsed with 2ml 1 × HBSS+. 293FT cells were seeded in laminin-coated slides, and were transfected after reaching 80% confluency with 1ug linearized JCV Mad1 or iLOV constructs recovered from 0.7% Agarose gel after EcoRI digestion. ICS was performed 18 days post transfection by fixing cells with 0.5ml 4% paraformadehyde (Sigma Aldrich) solution (dissolved in 1 × HBSS+) at room temperature (RT) for 30min. Cells were washed with 2ml 1 × HBSS+ and 0.5ml 4°C Cytofix/Cytoperm buffer was added (BD, 2350 Qume Drive, San Jose, CA, 95131 USA), followed by incubation at 4°C for 20min and a blocking step with 0.5ml MEM/10% Goat serum at RT for 30 min. JC VP1 protein was stained with anti SV40 VP1 monoclonal mouse Ab PAB597 at a concentration of 1:100 in MEM/1% goat serum (Dang et al., 2012b). Slides were incubated at RT for 30min, washed once with 1ml 1 × HBSS+/1% goat serum and incubated with 0.5ml 1:500 diluted goat anti mouse IgG-Alexa Fluor 568 in MEM/1% goat serum at RT 30min. Slides were then washed twice with 1ml 1 × HBSS+/1% goat serum, and once with 0.5ml 1 × Thimerosal (Sigma Aldrich). The slides were then mounted with coverslip and pictures were taken with a Leica DM500B fluorescent microscope. For the infection experiment, 80% confluent 293FT cultured in chamber slides were infected with supernatant collected from the transfection experiment at 7 days post transfection, and the same ICS protocol was used to detect VP1 at 7 days post infection.

2.6 Statistical analysis

To compare viral loads between different strains and compartments, we used non-parametric statistical tests for continuous variables (Kruskal-Wallis). Two-sided p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. We used Prism 6.0 and STATA 13 software to complete the analyses.

Results

1. Viral replication kinetics of JCV Mad1 and of the two JCV iLOV constructs

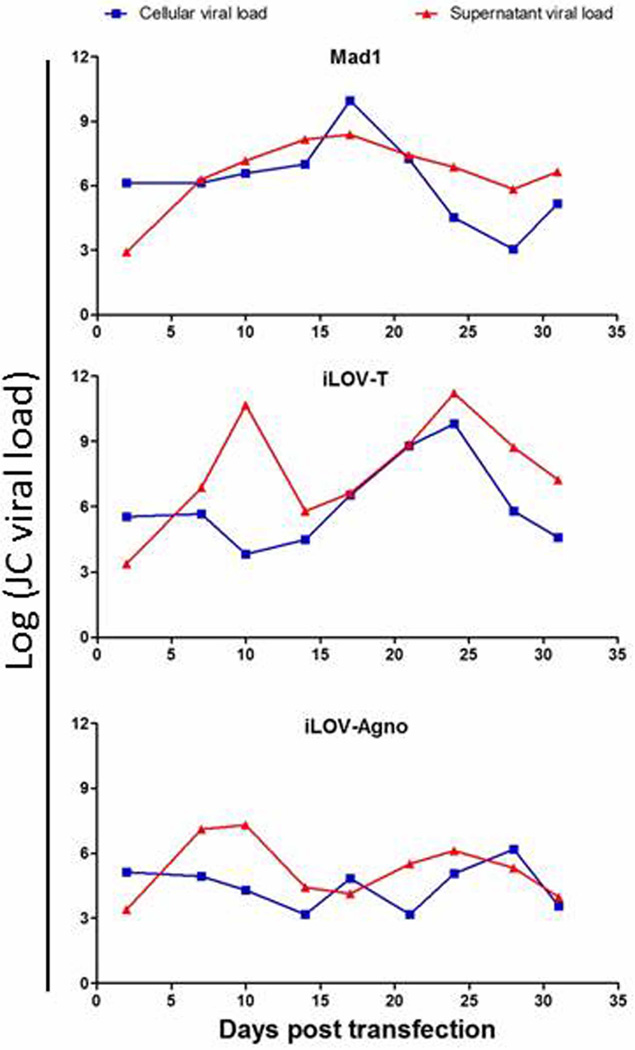

To determine whether JCV iLOV constructs could replicate in a permissive cell line, the different viral strains were transfected in 293FT and cells and supernatant were harvested twice a week over a 31-day period (Fig. 2). JCV Mad1 and iLOV-T had comparable replication patterns in the cellular and supernatant samples, but iLOV-Agno displayed significantly lower viral loads when compared with Mad1 (p=0.04) in the cellular compartment. iLOV-Agno viral loads also tended to be lower when compared with iLOV-T (p=0.06) in the cellular samples. Lastly, in the supernatant compartment, iLOV-Agno viral loads were significantly lower compared to iLOV-T viral loads (p=0.04) and tended to be lower when compared to Mad1 viral loads (p=0.06). These results indicate that both JCV iLOV constructs are replication-competent and can readily be maintained in culture in vitro.

Fig. 2.

Viral replication kinetic of JCV Mad1 and two JCV iLOV constructs. The JC viral load in transfected 293FT cells and culture medium is measured by QPCR targeting the JCV VP2 gene as described previously (Dang et al., 2012a). QPCR results are expressed in copies cps/ug of cellular DNA and cps/mL of supernatant. A: JCV Mad1 replication kinetic plot; B: JCV iLOV-T; C: JCV iLOV-Agno.

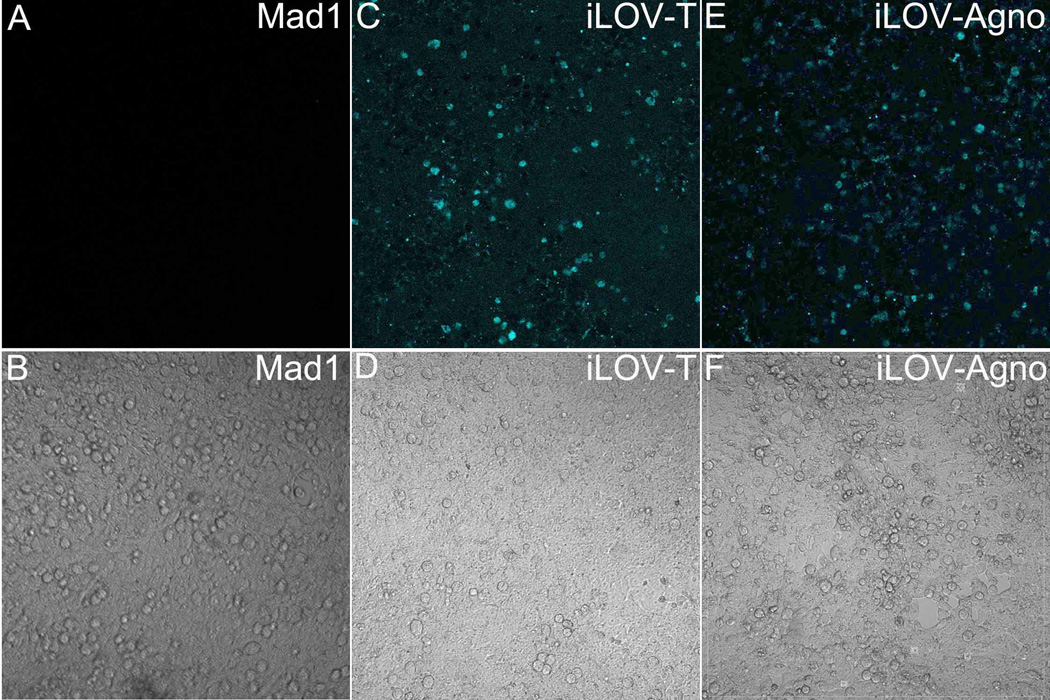

2. Detection of iLOV fluorescent signal with confocal microscope

To characterize iLOV expression, images of 5 days-transfected cell cultures were captured with setting of excitation laser light of 450nm and emission light of 490nm which is different from the reported 495nm (Chapman et al., 2008) due to the limit of our Olympus FV-1100 microscope. The actual color of iLOV signal is green, but iLOV was assigned to light blue for the purpose of this study. All three transfected 293FT samples were estimated to be 99% confluent as observed by differential interference contrast (DIC) (Fig. 3 B, D and F). No iLOV signal was detected in Mad1-transfected sample (Fig. 3A). Conversely, both iLOV-T and iLOV-Agno showed expression of iLOV protein (Fig. 3 C and E). These results indicate that iLOV expression can be readily detected by reversible confocal microscopy with 450nm and 490nm settings, despite the fact that their viral fitness was lower than the Mad-1 prototype.

Fig. 3.

Detection of iLOV signal by confocal microscope 5 days post transfection of 293FT cells with JCV Mad1 (A,B), JCV iLOV-T (C,D) and JCV iLOV-Agno (D,E). The upper panels (panel A, C, E) show confocal images, where the fluorescent signal of iLOV is assigned to light blue color. The lower panels (B, D, F) are images captured by differential interference contrast (DIC) and show >90% confluence of 293FT cells.

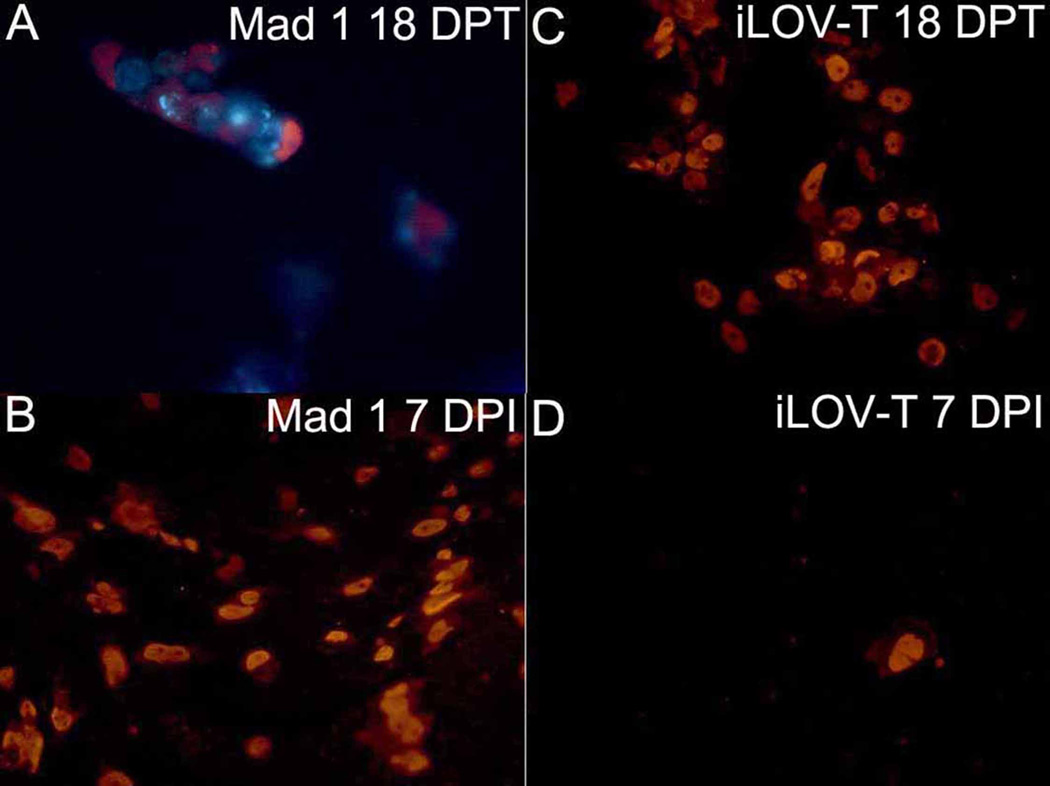

3. Detection of JCV capsid protein VP1 in transfected and infected 293FT cells

To determine whether iLOV constructs could undergo a full replication cycle and produce infectious particles, expression of the JC VP1 protein was examined by ICS. Figure 4 shows that both Mad1 and iLOV-T transfected 293FT cells produce VP1 proteins 18 days post transfection (Fig. 4 A & C) and 7 days post infection with supernatant harvested from transfected cells (Fig. 4 B & D). These results indicate that the presence of iLOV within JCV genome does not prevent full viral replication in vitro and production of infectious viral particles.

Fig. 4.

Intracellular staining (ICS) of JC virus VP1 protein in 293FT cells transfected or infected with JCV Mad1 (A,B) or JCV iLOV-T (C,D). JCV VP1 ICS is performed as described previously, using fluorescent reporter Alexa Fluor 568. 293FT cells 18 days post transfection (upper panels) or 7 days post infection (lower panels) are shown. Cells that are red express JCV VP1 protein

Discussion

A straightforward method to readily characterize JC virus kinetics in vitro would be a significant step towards the development of antiviral therapies. Fluorescent tagging of JC virions has been previously used (O'Hara et al., 2014; Yatawara et al., 2015) but only pertains to screening of entry blockers since the dye is present on the virion’s surface, and replicating virus will lack fluorescence. Therefore, screening for other compounds which can interrupt JCV DNA replication, RNA transcription, protein expression, virion packaging and transportation requires a different detection method. The ideal candidate would be a JCV molecular clone containing a fluorescent gene that remains replication- competent and produces infectious viral particles.

For this purpose, we developed JCV constructs containing a fluorescent protein gene capable of generating fluorescent signal during the viral cycle and thereby serve as an indicator for viral replication. The choice of the iLOV gene was influenced by a previous study of the JCV-related simian polyomavirus 40 (SV40), which has a genomic DNA of 5703 bp, and remains capable of replication after addition of extraneous sequence smaller than 460 bp (Chang and Wilson, 1986). This study suggested that DNA packaging in the 40 nm viral capsid is a limitation that may apply to JCV as well. Since the parental JCV genome of the Mad1 strain is 5130 bp (Fig. 1A), we postulated that only a fluorescent protein gene shorter than 570bp could be successfully packaged in the JCV capsid. Based on this assumption, we excluded the commonly used green fluorescent protein (717 bp) and yellow fluorescent protein (720 bp). Hence, we chose the 336 bp-long iLOV gene as the best label candidate.

JCV Mad1 genome has a 5130bp genome which can be categorized into three groups: non-coding control region (NCCR); early genes (including T and t regulatory protein genes which are expressed in the early stage of viral cycle) and late genes (including Agno protein gene, VP2, 3 and VP1 gene which are only expressed in the late stage of the viral cycle). In the iLOV-T construct, the iLOV gene is inserted right before the start codon of T gene, and will allow the study of the early events associated with JCV transcription. In the iLOV-Agno construct, the iLOV gene is inserted after the end codon of Agno gene, and can therefore serve to analyze the completion of the viral replication cycle associated with the production of mature viral particles.

Both iLOV constructs are 5466bp long and remain replication-competent in vitro, although they appear to have different kinetic profiles. Whether this is due to difference in RNA production, viral capsid formation or cytopathic effect will require further study. While mature viral particles have a capsid made of 72 pentamers of VP1 protein combined to either VP2 or VP3, they are not known to contain the t, T or agnoprotein. Additional experiments will be necessary to determine whether iLOV protein is incorporated in mature virions.

Our study has limitations. The optimal wave-length of iLOV excitation is 450 nm, and detection is 495 nm (Chapman et al., 2008). We used detection at 490 nm based on the configuration of our confocal microscope. In addition, confocal microscopy is time consuming and impractical for measurement of viral kinetics in vitro. Development of time-lapse photography with optimal excitation and detection wave-length will be necessary to characterize the full potential of the JCV-iLOV constructs in dissecting early and late event of the viral cycle and implement their use in screening antiviral compounds in vitro.

In conclusion we have adapted and optimized the fluorescent iLOV gene and created replication-competent JCV-iLOV constructs that can readily be detected in vitro. The location of iLOV close to early or late JCV genes will be a valuable tool in studying the kinetics of viral replication and for testing of therapies against JCV.

Highlights.

We construct two fluorescent gene iLOV-labelled replication-competent JCV mutants.

iLOV/JCV mutants infected cells can generate visible green fluorescence signal.

These mutants can be used to directly monitor JCV replication in vitro.

This monitoring method will greatly facilitate the screening of anti-JCV therapies.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Dr. John M. Christie from the University of Glasgow for the iLOV gene sequences he kindly provided, and Dr. Christian Wüthrich for capturing the ICS pictures. I.J.K. is supported in part by NIH National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke grants R01 NS047029 and R01 NS074995.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Agnihotri SP, Wuthrich C, Dang X, Nauen D, Karimi R, Viscidi R, Bord E, Batson S, Troncoso J, Koralnik IJ. A fatal case of JC virus meningitis presenting with hydrocephalus in a human immunodeficiency virus-seronegative patient. Ann Neurol. 2014;76:140–147. doi: 10.1002/ana.24192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonsson A, Green AC, Mallitt KA, O'Rourke PK, Pawlita M, Waterboer T, Neale RE. Prevalence and stability of antibodies to the BK and JC polyomaviruses: a long-term longitudinal study of Australians. J Gen Virol. 2010;91:1849–1853. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.020115-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang XB, Wilson JH. Formation of deletions after initiation of simian virus 40 replication: influence of packaging limit of the capsid. J Virol. 1986;58:393–401. doi: 10.1128/jvi.58.2.393-401.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman S, Faulkner C, Kaiserli E, Garcia-Mata C, Savenkov EI, Roberts AG, Oparka KJ, Christie JM. The photoreversible fluorescent protein iLOV outperforms GFP as a reporter of plant virus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:20038–20043. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807551105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang X, Koralnik IJ. Gone over to the dark side: Natalizumab-associated JC virus infection of neurons in cerebellar gray matter. Ann Neurol. 2013;74:503–505. doi: 10.1002/ana.23985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang X, Vidal JE, Oliveira AC, Simpson DM, Morgello S, Hecht JH, Ngo LH, Koralnik IJ. JC virus granule cell neuronopathy is associated with VP1 C terminus mutants. J Gen Virol. 2012a;93:175–183. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.037440-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang X, Wuthrich C, Gordon J, Sawa H, Koralnik IJ. JC virus encephalopathy is associated with a novel agnoprotein-deletion JCV variant. PLoS One. 2012b;7:e35793. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egli A, Infanti L, Dumoulin A, Buser A, Samaridis J, Stebler C, Gosert R, Hirsch HH. Prevalence of polyomavirus BK and JC infection and replication in 400 healthy blood donors. J Infect Dis. 2009;199:837–846. doi: 10.1086/597126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gheuens S, Wuthrich C, Koralnik IJ. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy: why gray and white matter. Annu Rev Pathol. 2013;8:189–215. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-020712-164018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kean JM, Rao S, Wang M, Garcea RL. Seroepidemiology of human polyomaviruses. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000363. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koralnik IJ, Wuthrich C, Dang X, Rottnek M, Gurtman A, Simpson D, Morgello S. JC virus granule cell neuronopathy: A novel clinical syndrome distinct from progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Ann Neurol. 2005;57:576–580. doi: 10.1002/ana.20431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matos A, Duque V, Beato S, da Silva JP, Major E, Melico-Silvestre A. Characterization of JC human polyomavirus infection in a Portuguese population. J Med Virol. 2010;82:494–504. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Hara BA, Rupasinghe C, Yatawara A, Gaidos G, Mierke DF, Atwood WJ. Gallic acid-based small-molecule inhibitors of JC and BK polyomaviral infection. Virus Res. 2014;189:280–285. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wollebo HS, White MK, Gordon J, Berger JR, Khalili K. Persistence and pathogenesis of the neurotropic polyomavirus JC. Ann Neurol. 2015;77:560–570. doi: 10.1002/ana.24371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuthrich C, Dang X, Westmoreland S, McKay J, Maheshwari A, Anderson MP, Ropper AH, Viscidi RP, Koralnik IJ. Fulminant JC virus encephalopathy with productive infection of cortical pyramidal neurons. Ann Neurol. 2009;65:742–748. doi: 10.1002/ana.21619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yatawara A, Gaidos G, Rupasinghe CN, O'Hara BA, Pellegrini M, Atwood WJ, Mierke DF. Small-molecule inhibitors of JC polyomavirus infection. J Pept Sci. 2015;21:236–242. doi: 10.1002/psc.2731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]