Abstract

Objectives

Electronic physician claims databases are widely used for chronic disease research and surveillance, but quality of the data may vary with a number of physician characteristics, including payment method. The objectives were to develop a prediction model for the number of prevalent diabetes cases in fee-for-service (FFS) electronic physician claims databases and apply it to estimate cases among non-FFS (NFFS) physicians, for whom claims data are often incomplete.

Design

A retrospective observational cohort design was adopted.

Setting

Data from the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador were used to construct the prediction model and data from the province of Manitoba were used to externally validate the model.

Participants

A cohort of diagnosed diabetes cases was ascertained from physician claims, insured resident registry and hospitalisation records. A cohort of FFS physicians who were responsible for the diagnosis was ascertained from physician claims and registry data.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

A generalised linear model with a γ distribution was used to model the number of diabetes cases per FFS physician as a function of physician characteristics. The expected number of diabetes cases per NFFS physician was estimated.

Results

The diabetes case cohort consisted of 31 714 individuals; the mean cases per FFS physician was 75.5 (median=49.0). Sex and years since specialty licensure were significantly associated (p<0.05) with the number of cases per physician. Applying the prediction model to NFFS physician registry data resulted in an estimate of 18 546 cases; only 411 were observed in claims data. The model demonstrated face validity in an independent data set.

Conclusions

Comparing observed and predicted disease cases is a useful and generalisable approach to assess the quality of electronic databases for population-based research and surveillance.

Keywords: STATISTICS & RESEARCH METHODS, PUBLIC HEALTH, EPIDEMIOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study developed a prediction model to estimate the completeness of non-fee-for-service electronic physician claims for capturing services to populations.

The prediction model developed in this study is an efficient and potentially generalisable tool for routine estimation of the magnitude of administrative data completeness.

This study emphasises that incomplete electronic physician claims data should be supplemented with other data sources, including electronic medical records, to ensure comprehensive data for chronic disease research and surveillance.

The study focuses on completeness of electronic physician claims databases for diabetes; the research should be extended to other chronic diseases to ensure its generalisability.

Introduction

Electronic administrative health databases are widely used for population-based health research and surveillance.1 2 The popularity of these databases has arisen for several reasons: they are available in a timely manner, provide information about large numbers of individuals, and are relatively inexpensive to access and use. Physician claims electronic databases, which contain information on outpatient healthcare contacts, capture information on a larger proportion of the population than inpatient hospital records, but quality of claims databases tends to be poorer than that of hospital records for which standards for data collection and coding exist.3 4 Studies about the quality of claims databases are therefore essential to evaluate and improve their accuracy. However, most studies about physician claims databases have focused only on the validity of diagnosis codes,5–8 while other elements of data quality that could impact on the usefulness of these data for research and surveillance have infrequently been examined.9

Incompleteness of physician claims databases, which can result in substantially biased estimates of disease prevalence and healthcare utilisation, may arise for a number of reasons. The information in these databases is used to remunerate physicians for services provided to patients, usually on a fee-for-service (FFS) basis. However, physicians not remunerated by FFS methods may inconsistently record patient encounters in these databases. Specifically, non-FFS (NFFS) physicians, who are often paid via salaries and contracts, are not always required to use the same claims submission processes as FFS physicians,10 a process known as shadow billing. Incomplete capture of NFFS physician claims can have serious consequences; previous research has demonstrated substantial underestimation of diabetes prevalence associated with a lack of shadow billing.11

Possible methods to estimate completeness of electronic administrative databases12–16 include: (1) comparing observed to expected numbers of cases, where expected cases are estimated from a parametric or non-parametric model, (2) comparing the number of cases ascertained in administrative databases to cases ascertained from a validated database, (3) using capture-recapture models and (4) conducting database audits. These methods have primarily been applied to cancer registry and hospital records, but not to physician claims databases. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to develop a population-based model to predict prevalent diabetes cases from FFS physician claims and apply it to estimate cases among NFFS physicians, for whom claims data may be incomplete. We focus on diabetes because administrative health databases have demonstrated good sensitivity and specificity for case identification using electronic administrative databases and surveillance of diabetes is of interest worldwide.6

Methods

Data sources for prediction model

Data to construct the prediction model were from the eastern Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador (NL), which has a population of approximately 515 000 according to the 2011 Statistics Canada Census. NL physicians remunerated by NFFS methods do not submit shadow-billed claims to the provincial ministry of health,17 while physicians remunerated by FFS methods submit all of their claims to the ministry. NL has a larger proportion of NFFS physicians than most other Canadian provinces.18

Physician claims, physician registry records, hospital discharge abstracts and insured resident registry records from 1 April 2002 to 31 March 2004 were used to conduct the study. We selected these years because the NL physician registry contains comprehensive information on all registered physicians in this time period but is incomplete in later years; the registry includes information about physician remuneration methods, sex, age, specialty, year the medical degree was obtained and health region of the practice location. Each physician claim contains a single three-digit diagnosis code recorded using the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth revision (ICD-9) and date of service. Hospital discharge abstracts contain dates of admission and discharge and up to 20 ICD-9 and ICD-10-CA diagnosis codes. The resident registry contains dates of health insurance coverage, sex, date of birth and health region for all residents eligible for health insurance benefits. Physician claims, hospital separation abstracts and insured resident registry records are linkable using a unique, anonymised patient identifier. Physician claims and the physician registry are also linkable using an anonymised physician identifier.

Study cohort for prediction model

The diabetes case cohort comprised all individuals who met a validated case definition, which requires at least one hospitalisation or at least two physician billing claims (ICD-9 code 250; ICD-10-CA code E10-E14) within a 730-day period.5 19 Individuals <20 years of age or without health insurance coverage at the date of the case-qualifying diagnosis were excluded. For cases ascertained from hospital discharge abstracts, the date of the case-qualifying diagnosis was the date of hospital admission; for cases ascertained from physician claims, the date of the case-qualifying diagnosis was the date of the physician claim for the second diagnosis within the 730-day period. Diabetes cases were classified into three mutually exclusive groups: (1) cases ascertained only from hospital discharge abstracts, (2) cases ascertained from physician claims for which the case-qualifying diagnosis was from a FFS physician and (3) cases ascertained from physician claims for which the case-qualifying diagnosis was from a NFFS physician. The last group is comprised of cases from the claims of a small number of NFFS physicians who receive a portion of their remuneration by FFS payments. While cases in the latter two groups could have a hospital discharge abstract with a diabetes diagnosis, they qualified as a case based on having at least two physician billing claims with a diabetes diagnosis.

The physician cohort included all members of the physician registry who had at least one claim for an individual in the diabetes case cohort. Each physician was assigned to each member of the diabetes case cohort in the second and third groups based on the physician identification number found on the billing claim for the case-qualifying diabetes diagnosis.

Statistical analyses for prediction model

The diabetes case and physician cohorts were described using means, SDs, medians, frequencies and percentages. The mean and median number of diabetes cases per physician was estimated and stratified by physician cohort characteristics.

A multivariable generalised linear regression model with a γ distribution was fit to the number of diabetes cases for each FFS physician.20 The model covariates were years since specialty was received (quartiles; reference=lowest quartile), physician sex (reference=female), health region of practice (reference=Labrador, a remote region of NL) and specialty (reference=specialist). Years since specialty was highly correlated with years since medical degree and age (r≥0.80), hence the latter two variables were excluded. A main effects model was compared with a model with main and two-way interaction effects.20 Penalised goodness-of-fit measures, including the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC),21 were used to select the best fit model. The ratio of the deviance to degrees of freedom was used to assess model dispersion.

Model validation

We selected the Canadian province of Manitoba (MB) for external validation, which has a population of 1.2 million according to the 2011 Statistics Canada Census. NFFS physicians in this province submit shadow-billed claims to the provincial ministry of health. Watson et al22 reported that among family physicians practising in Winnipeg, the only major centre in MB (680 000+population), up to 90% of physicians remunerated by NFFS methods submit claims for services provided to patients. However, rates of shadow billing are expected to be lower in other regions of the province.

The same data sources were available in MB as in NL, with minor differences in database characteristics. Specifically, physician claims in MB contain diagnosis codes based on ICD-9-CM (ie, Clinical Modification).23 The MB physician registry does not contain information on year of medical degree. Five health regions, defined by the ministry of health for planning the delivery of healthcare services, were used to identify patient residence and physician practice locations.

Internal validation was conducted for both the NL and MB models. Measures of prediction accuracy, which included bias, mean absolute error (MAE) and root mean square error (RMSE),24 were calculated based on 10-fold cross-validation.25 26

Model prediction

The final fitted model for NL was used to predict the number of prevalent diabetes cases per NFFS physician. However, given that not all NFFS physicians provide services to patients with diabetes, we used the ratio of FFS physicians in the physician cohort to the total number of FFS physicians in the province27 to select a random prediction sample. A similar process was used to predict the number of cases from the MB data. In MB, we also compared the predicted number of diabetes cases for NFFS physicians to the observed number of cases from the shadow-billed claims of NFFS physicians.

The total number of prevalent diabetes cases in each province was estimated as the sum of: (1) observed cases ascertained from hospital discharge abstracts only, (2) observed cases ascertained from claims of FFS physicians, (3) predicted cases for NFFS physicians. Denominators of the prevalence estimates were based on 2001 Statistics Canada Census data; 95% CIs were calculated using the binomial distribution.

All analyses were conducted using SAS V.9.3. Data access approval was provided by the Newfoundland and Labrador Centre for Health Information and the Manitoba Health Information Privacy Committee.

Results

Descriptive analyses

A total of 31 714 prevalent diabetes cases were identified from the NL administrative data (table 1); 91.1% (n=28 989) of cases were identified from billing claims of physicians remunerated by FFS, while 1.3% (n=411) of cases were ascertained from billing claims submitted by NFFS physicians who received a portion of their remuneration by FFS. Almost two-thirds (60.7%) of diabetes cases from FFS physician claims were residents of the Eastern health region, which contains the largest city in NL (200 000+ population); 40.5% were 65+ years.

Table 1.

Characteristics of diabetes case cohort by ascertainment source and province

| Case characteristics | Cases ascertained from hospital discharge abstracts |

Cases ascertained from physician billing claims for FFS physicians |

Cases ascertained from physician billing claims for NFFS physicians* |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Per cent | n | Per cent | n | Per cent | |

| Newfoundland and Labrador (N=31 714) | ||||||

| Total | 2405 | 100.0 | 28 898 | 100.0 | 411 | 100.0 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 1158 | 48.1 | 13 872 | 48.0 | 217 | 52.8 |

| Female | 1247 | 51.9 | 15 026 | 51.9 | 194 | 47.2 |

| Age group (years) | ||||||

| <35 | 39 | 1.6 | 1448 | 5.0 | 30 | 7.3 |

| 35–49 | 168 | 7.0 | 4932 | 17.1 | 84 | 20.4 |

| 50–64 | 570 | 23.7 | 10 808 | 37.4 | 136 | 33.1 |

| 65+ | 1628 | 67.7 | 11 710 | 40.5 | 161 | 39.2 |

| Health region of residence | ||||||

| Eastern | 1201 | 49.9 | 17 547 | 60.7 | 110 | 26.8 |

| Central | 523 | 21.7 | 5909 | 20.4 | 258 | 62.8 |

| Western | 389 | 16.2 | 4840 | 16.7 | 7 | 1.7 |

| Labrador | 267 | 11.1 | 464 | 1.6 | 35 | 8.5 |

| Missing | 25 | 1.0 | 138 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.2 |

| Manitoba (N=51 031) | ||||||

| Total | 2250 | 100.0 | 42 933 | 100.0 | 5848 | 100.0 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 1161 | 51.6 | 22 078 | 51.4 | 2764 | 47.3 |

| Female | 1089 | 48.4 | 20 855 | 48.6 | 3084 | 52.7 |

| Age group (years) | ||||||

| <35 | 71 | 3.2 | 1952 | 4.6 | 375 | 6.4 |

| 35–49 | 236 | 10.5 | 7636 | 17.8 | 1358 | 23.2 |

| 50–64 | 534 | 23.7 | 15 319 | 35.7 | 2120 | 36.3 |

| 65+ | 1409 | 62.6 | 18 026 | 42.0 | 1995 | 34.1 |

| Health region of residence | ||||||

| Winnipeg | 1180 | 62.6 | 25 949 | 60.4 | 1409 | 24.1 |

| Interlake-Eastern | 262 | 11.6 | 4503 | 10.5 | 970 | 16.6 |

| Northern | 189 | 8.4 | 1951 | 4.5 | 1562 | 26.7 |

| Prairie Mountain | 370 | 16.4 | 6400 | 14.9 | 1067 | 18.3 |

| Southern | 249 | 11.1 | 4130 | 9.6 | 840 | 14.4 |

*These cases were ascertained from the claims of NFFS physicians receiving partial FFS remuneration in Newfoundland and Labrador, and from the claims of NFFS physicians who shadow bill in Manitoba.

FFS, fee-for-service; NFFS, non-FFS.

In the MB external validation data, 51 031 prevalent diabetes cases were identified (table 1), of which 84.1% were ascertained from the billing claims of FFS physicians. Three-quarters (75.9%) of prevalent cases ascertained from the shadow-billed claims of NFFS physicians were from non-Winnipeg health regions.

There were 388 individuals in the NL physician cohort (table 2). Among FFS physicians (93.3%), the majority were general practitioners (80.4%), and most were from the Eastern health region (71.3%). The MB physician cohort contained more than 1200 physicians, of which 80.4% were FFS physicians. Among these FFS physicians, more than half (57.8%) were in the 40–64 years age group. The NFFS physicians (n=270) were primarily <40 years (68.5%) and almost 80% practiced outside of the urban Winnipeg health region.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the physician cohort by method of remuneration and province

| Physician characteristics | Newfoundland and Labrador (N=388) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FFS (n=362) |

NFFS* (n=26) |

|||

| n | Per cent | n | Per cent | |

| Specialty | ||||

| General practitioner | 291 | 80.4 | 22 | 84.6 |

| Specialist | 71 | 19.6 | 4 | 15.4 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 257 | 70.9 | 19 | 73.1 |

| Female | 105 | 29.0 | 7 | 26.9 |

| Age group (years) | ||||

| <40 | 85 | 23.5 | 15 | 57.7 |

| 40–64 | 269 | 74.3 | 11 | 42.3 |

| 65+ | 8 | 2.2 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Health region of practice | ||||

| Eastern | 258 | 71.3 | 6 | 23.1 |

| Central | 56 | 15.5 | 13 | 50.0 |

| Western | 42 | 11.6 | 3 | 11.5 |

| Labrador | 6 | 1.7 | 4 | 15.4 |

| Medical degree, years† | 22.5 (10.7) | 22.0 | 15.0 (9.7) | 14.0 |

| Specialty, years† | 17.2 (10.1) | 17.0 | 6.8 (8.9) | 3.5 |

|

Manitoba (N=1229) |

||||

| FFS (n=989) | NFFS (n=270) | |||

| n | Per cent | n | Per cent | |

| Specialty | ||||

| General practitioner | 770 | 77.9 | – | – |

| Specialist | 219 | 22.1 | – | – |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 741 | 74.9 | 201 | 74.4 |

| Female | 248 | 25.1 | 69 | 25.6 |

| Age group (years) | ||||

| <40 | 301 | 30.4 | 185 | 68.5 |

| 40–64 | 572 | 57.8 | – | – |

| 65+ | 116 | 11.8 | – | – |

| Missing | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Health region of practice | ||||

| Winnipeg | 659 | 66.6 | 57 | 21.1 |

| Interlake-Eastern | 61 | 6.2 | 40 | 14.8 |

| Northern | 25 | 2.5 | 63 | 23.3 |

| Prairie Mountain | 152 | 15.4 | 62 | 23.0 |

| Southern | 92 | 9.3 | 48 | 17.8 |

| Specialty, years* | 12.1 (9.9) | 10.0 | 5.2 (6.4) | 3.0 |

*In Newfoundland and Labrador, NFFS physicians identified in claims data received partial FFS remuneration, while in Manitoba, NFFS physicians identified in claims data shadow bill.

†Reported values are mean (SD) and median; some cells cannot be reported, in accordance with Manitoba Health requirements, because of small numbers.

FFS, fee-for-service; NFFS, non-FFS.

Table 3 describes the mean and median number of prevalent diabetes cases per FFS physician. In NL, the average number of prevalent cases per FFS physician was 75.5 and the median was 49.0. The mean and median were higher for general practitioners than for specialists and also for males than females. For MB, the average number of prevalent diabetes cases per FFS physician was 43.4 and the median was 25.0.

Table 3.

Mean (SD) and median number of prevalent cases in the diabetes case cohort per fee-for-service physician in the physician cohort

| Physician characteristics | Median | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | ||

| Newfoundland and Labrador | ||

| Province | 75.5 (84.6) | 49.0 |

| Specialty | ||

| General practitioner | 79.0 (66.2) | 66.0 |

| Specialist | 61.0 (136.8) | 9.0 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 89.3 (94.1) | 75.0 |

| Female | 41.5 (37.2) | 32.5 |

| Age group (years) | ||

| <40 | 54.9 (64.8) | 32.5 |

| 40–64 | 99.9 (98.3) | 91.0 |

| 65+ | 63.8 (68.6) | 34.5 |

| Health region of practice | ||

| Eastern | 67.8 (73.1) | 42.0 |

| Central | 87.8 (87.7) | 59.0 |

| Western | 108.1 (129.5) | 86.0 |

| Labrador | 47.6 (47.9) | 38.5 |

| Manitoba | ||

| Province | 43.4 (74.2) | 25.0 |

| Specialty | ||

| General practitioner | 45.1 (45.7) | 35.0 |

| Specialist | 37.6 (132.8) | 3.0 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 47.7 (76.0) | 33.0 |

| Female | 30.5 (67.2) | 17.0 |

| Age group (years) | ||

| <40 | 25.5 (34.2) | 14.5 |

| 40–64 | 52.1 (90.4) | 34.0 |

| 65+ | 47.1 (49.8) | 34.5 |

| Health region of practice | ||

| Interlake-Eastern | 45.9 (37.8) | 48.0 |

| Northern | 49.4 (59.4) | 20.0 |

| Prairie Mountain | 42.4 (39.7) | 35.0 |

| Southern | 35.1 (29.1) | 28.0 |

| Winnipeg | 44.3 (86.7) | 20.0 |

Prediction model

For NL, the main effects model provided a good fit to the data, as judged by the ratio of model deviance to degrees of freedom (ratio=1.0) and the AIC was smaller for a main effects model than for one with main and two-way interaction effects (3833.1 vs 3830.4); likelihood ratio tests revealed statistically significant main effects for sex (p<0.0001) and years since specialty (p=0.0006).

The regression analyses produced similar results in the MB external validation data; the ratio of model deviance to degrees of freedom was close to 1.0 for the main effects model. The model with main and two-way interaction effects resulted in a negligible decrease in the AIC. The main effects of sex (p<0.0001), specialty (p=0.0021) and years since specialty licensure (p<0.0001) were statistically significant.

With respect to the internal cross-validation, for the NL model absolute bias estimates ranged from 0.2% to 12.9% across the 10 data folds, while for the MB model the estimates ranged from 0.6% to 13.8%. The MAE ranged from 40.1 to 67.5 for the NL model and from 26.7 to 43.2 for the MB model. Finally, the RMSE ranged from 56.5 to 131.2 for the NL model and from 33.8 to 151.0 for the MB model.

Using the MB model results, we compared the observed and expected number of prevalent diabetes cases per FFS and NFFS physician (table 4) for the entire province and by health region of practice. The provincial and regional figures were similar for FFS physicians, supporting the internal validity of the model. For NFFS physicians, the expected number of cases was 51% higher than the observed number for the entire province. When we examined these values by health region, we found that the expected value was 8.2% lower than the observed value for the Winnipeg health region. However, for the remaining health regions, the expected values were much higher than the observed values.

Table 4.

Observed and predicted average number of diabetes cases per fee-for-service (FFS) and non-FFS (NFFS) physician in Manitoba's physician cohort

| FFS |

NFFS |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed | Predicted | Observed | Predicted | |

| Entire province | 43.4 | 43.8 | 21.7 | 32.7 |

| Health region of practice | ||||

| Interlake-Eastern | 45.9 | 49.7 | 20.7 | 31.9 |

| Northern | 49.4 | 43.3 | 15.1 | 30.6 |

| Prairie Mountain | 42.4 | 44.0 | 16.0 | 39.4 |

| Southern | 35.1 | 36.0 | 17.1 | 21.8 |

| Winnipeg | 44.3 | 44.3 | 39.5 | 37.4 |

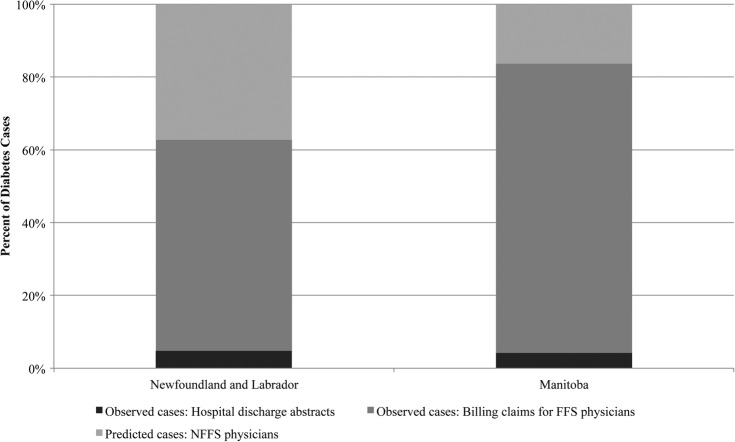

Figure 1 shows the percentage of diabetes cases ascertained from each data source in both provinces. In NL, the prediction model resulted in a 37.2% increase in the number of diabetes cases ascertained from the administrative databases, while in MB it resulted in a 16.3% increase. In NL, crude diabetes prevalence based on cases ascertained only from hospital data and FFS physician claims was 8.1%, while the estimate based on observed and expected cases was 13.0% (95% CI 12.9% to 13.0%). In MB, the crude diabetes prevalence estimate based on cases ascertained from hospital data and FFS physician claims was 5.6%, while the estimate based on both observed and expected cases was 6.7% (95% CI 6.7% to 6.8%).

Figure 1.

Per cent of observed and predicted diabetes cases by ascertainment data source and Canadian province (FFS, fee-for-service; NFFS, non-FFS).

Discussion

This study developed a prediction model for linked administrative health databases to estimate the completeness of electronic physician claims data; the model was applied to estimate under-ascertainment of prevalent diabetes cases but could be applied to other chronic or acute conditions that are primarily managed or treated in non-acute care settings. When the model was applied to data from the Canadian province of NL, the results revealed that close to 40% of diabetes cases were missed because NFFS physicians do not report contacts with patients in claims data. When the model was externally validated in MB, a province in which some NFFS physicians submit some claims, the modelling results indicated that <20% of diabetes cases were missed, but this percentage varied substantially by region; there was less bias in the Winnipeg health region, which contains the largest city in MB, and more substantial bias in non-Winnipeg health regions where there is a higher proportion of NFFS physicians.

Data from the 2005 Canadian Community Health Survey,28 a national survey used for regional chronic disease surveillance, revealed a crude diabetes prevalence of 6.8% for NL and 4.4% for MB for the population 12+years, a difference of more than 50%. When we compared crude prevalence estimates for the two provinces using only FFS claims and hospital records, rates in NL were just 8.9% higher than those in MB. However, after adjustment for potential missed cases using our prediction model, crude prevalence was 45.1% higher in NL than in MB, producing a similar difference in estimates to those observed in survey data.

Incomplete capture of claims for NFFS physicians is similar to unit non-response in survey data, both of which can bias parameter estimates and increase variance estimates. Unit non-response in surveys is often difficult to adjust for, because information about non-responders is rarely available to the researcher. In fact, administrative data have been used in previous research to estimate the effect of survey non-response bias in estimates of healthcare use.29 However, our study suggests that the use of administrative data for evaluating survey non-response should be adopted with caution, as administrative databases may themselves be incomplete.

While the proposed prediction model provides a useful tool to estimate bias in disease prevalence due to incomplete claims data, it is equally important to consider how other databases can be used to address gaps in these data. Electronic medical records are increasingly being adopted in population-based chronic disease research and surveillance studies,30 and could represent an important additional source of data for case ascertainment. Pharmacy databases have also been used for case ascertainment31 when the medications used for disease treatment have high specificity for case capture.

Limitations of the study include the restricted set of explanatory variables available to develop the prediction model. Residual confounding due to factors such as physician productivity,10 type of practice and even characteristics of the patients seen by a physician may affect prediction accuracy.32 Strengths of the study include the use of a validated case definition to ascertain diabetes cases and the internal and external validation process.

Further research could examine the validity of the prediction model by applying it to other chronic diseases and in other jurisdictions;33 the utility of the model is not limited to Canadian administrative data, as a similar approach has been proposed to evaluate the completeness of cancer registry data.16 Simulation could also be used to assess the impact of patient, physician and health system characteristics on estimates of completeness.34 For example, the model assumes that physician characteristics will have the same distribution and association with the number of prevalent diabetes cases in FFS and NFFS populations, which may not be a valid assumption.35

In summary, this study revealed that completeness of physician claims data are associated with method of physician remuneration and that a predictive model can be used to estimate the magnitude of data incompleteness for disease surveillance. This predictive model makes use of routinely collected linked data, and therefore is feasible to implement over time and across jurisdictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to Manitoba Health, Healthy Living, and Seniors (HIPC 2012/2013-04) and the Newfoundland and Labrador Centre for Health Information for the provision of data.

Footnotes

Contributors: LML, GK, HQ, MS and KS designed the analysis and acquired the study data. JPK, XY, NM and WK conducted the analyses. LML, JPK and NM drafted the manuscript and all remaining authors read and revised it substantially. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript before submission.

Funding: This research was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (funding reference number 123357). LML was supported by a Research Chair from the Manitoba Health Research Council.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: University of Manitoba Health Research Ethics Board and the NL Health Research Ethics Board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Virnig BA, Mcbean M. Administrative data for public health surveillance and planning. Annu Rev Public Health 2001;22:213–30. 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.22.1.213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dombkowski KJ, Wasilevich EA, Lyon-Callo S et al. Asthma surveillance using medicaid administrative data: a call for a national framework. J Public Health Manag Pract 2009;15:485–93. 10.1097/PHH.0b013e3181a8c334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Potter BK, Manuel D, Speechley KN et al. Is there value in using physician billing claims along with other administrative health care data to document the burden of adolescent injury? An exploratory investigation with comparison to self-reports in Ontario, Canada. BMC Health Serv Res 2005;5:15 10.1186/1472-6963-5-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henderson T, Shepheard J, Sundararajan V. Quality of diagnosis and procedure coding in ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care 2006;44:1011–19. 10.1097/01.mlr.0000228018.48783.34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hux JE, Ivis F, Flintoft V et al. Diabetes in Ontario: determination of prevalence and incidence using a validated administrative data algorithm. Diabetes Care 2002;25:512–16. 10.2337/diacare.25.3.512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saydah SH, Geiss LS, Tierney E et al. Review of the performance of methods to identify diabetes cases among vital statistics, administrative, and survey data. Ann Epidemiol 2004;14:507–16. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2003.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quan H, Khan N, Hemmelgarn BR et al. Validation of a case definition to define hypertension using administrative data. Hypertension 2009;54:1423–8. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.139279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tu K, Campbell NRC, Chen ZL et al. Accuracy of administrative databases in identifying patients with hypertension. Open Med 2007;1:E3–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saez M, Barcelo MA, Coll De TG. A selection-bias free method to estimate the prevalence of hypertension from an administrative primary health care database in the Girona Health Region, Spain. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 2009;93:228–40. 10.1016/j.cmpb.2008.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wranik DW, Durier-Copp M. Physician remuneration methods for family physicians in Canada: expected outcomes and lessons learned. Health Care Anal 2009;18:35–59. 10.1007/s10728-008-0105-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alshammari AM, Hux JE. The impact of non-fee-for-service reimbursement on chronic disease surveillance using administrative data. Can J Public Health 2009;100:472–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crocetti E, Miccinesi G, Paci E et al. An application of the two-source capture-recapture method to estimate the completeness of the Tuscany Cancer Registry, Italy. Eur J Cancer Prev 2001;10:417–23. 10.1097/00008469-200110000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dockerty JD, Becroft DM, Lewis ME et al. The accuracy and completeness of childhood cancer registration in New Zealand. Cancer Causes Control 1997;8:857–64. 10.1023/A:1018412311997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schouten LJ, Straatman H, Kiemeney LA et al. The capture-recapture method for estimation of cancer registry completeness: a useful tool? Int J Epidemiol 1994;23:1111–16. 10.1093/ije/23.6.1111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brenner H, Stegmaier C, Ziegler H. Estimating completeness of cancer registration: an empirical evaluation of the two source capture-recapture approach in Germany. J Epidemiol Community Health 1995;49:426–30. 10.1136/jech.49.4.426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Das B, Clegg LX, Feuer EJ et al. A new method to evaluate the completeness of case ascertainment by a cancer registry. Cancer Causes Control 2008;19:515–25. 10.1007/s10552-008-9114-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Newfoundland and Labrador Centre for Health Information. Enhancing chronic disease surveillance in Newfoundland and Labrador: adjustment of rates based on physician payment methods. Newfoundland and Labrador centre for health information. St. John's, NL: Newfoundland and Labrador Centre for Health Information, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Canadian Institute for Health Information. National Physician Database, 2008–2009. Ottawa, Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clottey C, Mo F, Lebrun B et al. The development of the national diabetes surveillance system (NDSS) in Canada. Chronic Dis Can 2001;22:67–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mcculloch CE, Searle SR. Generalized, linear, and mixed models. New York: Wiley, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bozdogan H. Model selection and Akaike's information criterion (AIC): the general theory and its analytical extensions. Psychometrika 1987;52:345–70. 10.1007/BF02294361 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watson DE, Katz A, Reid RJ et al. Family physician workloads and access to care in Winnipeg: 1991 to 2001. CMAJ 2004;171:339–42. 10.1503/cmaj.1031047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lix LM, Walker R, Quan H et al. Features of physician billing claims databases in Canada. Chronic Dis Can 2012;32:186–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dunn G, Mirandola M, Amaddeo F et al. Describing, explaining or predicting mental health care costs: a guide to regression models—methodological review. Br J Psychiatry 2003;183:398–404. 10.1192/bjp.183.5.398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Austin PC, Rothwell DM, Tu JV. A comparison of statistical modeling strategies for analyzing length of stay after CABG surgery. Health Serv Outcomes Res Methodol 2002;3:107–33. 10.1023/A:1024260023851 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuwornu JP, Lix LM, Quail J et al. A comparison of statistical models for analyzing episode-of-care costs for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Health Serv Outcomes Res Methodol 2013;13:203–8. 10.1007/s10742-013-0112-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Canadian Institute for Health Information. The status of alternate payment programs for physicians in Canada: 2002–2003 and preliminary information for 2003–2004. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanmartin C, Gilmore J. Diabetes prevalence and care practices. Health Rep 2008;19:59–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gundgaard J, Ekholm O, Hansen EH et al. The effect of non-response on estimates of health care utilisation: linking health surveys and registers. Eur J Public Health 2008;18:189–94. 10.1093/eurpub/ckm103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Desai JR, Wu P, Nichols GA et al. Diabetes and asthma case identification, validation, and representativeness when using electronic health data to construct registries for comparative effectiveness and epidemiologic research. Med Care 2012;50(Suppl):S30–5. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318259c011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maio V, Yuen E, Rabinowitz C et al. Using pharmacy data to identify those with chronic conditions in Emilia Romagna, Italy. J Health Serv Res Policy 2005;10:232–8. 10.1258/135581905774414259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hanley JA, Dendukuri N. Efficient sampling approaches to address confounding in database studies. Stat Methods Med Res 2009;18:81–105. 10.1177/0962280208096046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kleinberg S, Elhadad N. Lessons learned in replicating data-driven experiments in multiple medical systems and patient populations. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2013;2013:786–95. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Silcocks PB, Robinson D. Simulation modelling to validate the flow method for estimating completeness of case ascertainment by cancer registries. J Public Health (Oxf) 2007;29:455–62. 10.1093/pubmed/fdm053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vergouwe Y, Steyerberg EW, Eijkemans MJ et al. Substantial effective sample sizes were required for external validation studies of predictive logistic regression models. J Clin Epidemiol 2005;58:475–83. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.06.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]