Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to identify the challenges faced by primary care physicians (PCPs) when prescribing medications for patients with chronic diseases in a teaching hospital in Malaysia.

Design/setting

3 focus group discussions were conducted between July and August 2012 in a teaching primary care clinic in Malaysia. A topic guide was used to facilitate the discussions which were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim and analysed using a thematic approach.

Participants

PCPs affiliated to the primary care clinic were purposively sampled to include a range of clinical experience. Sample size was determined by thematic saturation of the data.

Results

14 family medicine trainees and 5 service medical officers participated in this study. PCPs faced difficulties in prescribing for patients with chronic diseases due to a lack of communication among different healthcare providers. Medication changes made by hospital specialists, for example, were often not communicated to the PCPs leading to drug duplications and interactions. The use of paper-based medical records and electronic prescribing created a dual record system for patients’ medications and became a problem when the 2 records did not tally. Patients sometimes visited different doctors and pharmacies for their medications and this resulted in the lack of continuity of care. PCPs also faced difficulties in addressing patients’ concerns, and dealing with patients’ medication requests and adherence issues. Some PCPs lacked time and knowledge to advise patients about their medications and faced difficulties in managing side effects caused by the patients’ complex medication regimen.

Conclusions

PCPs faced prescribing challenges related to patients, their own practice and the local health system when prescribing for patients with chronic diseases. These challenges must be addressed in order to improve chronic disease management in primary care and, more importantly, patient safety.

Keywords: PRIMARY CARE, PRESCRIBING, CHRONIC DISEASE MANAGEMENT, MEDICATION SAFETY, PATIENT SAFETY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The qualitative approach employed in this study allowed free expression of the challenges and experiences faced by primary care physicians when prescribing for patients with chronic diseases.

Since this study was conducted in the primary care clinic within a teaching hospital, the issues highlighted may not be applicable to the other types of primary care setting.

The views and challenges expressed by the primary care physicians in this study might be different from those of family medicine specialists as they were not included in this study.

Background

Medication plays an important part in chronic disease management, and prescribing for patients with chronic disease has become increasingly challenging.1 2 With the rising prevalence of patients with multimorbidities, their medication regimens are getting more complex.3 Clinical practice guidelines often only provide recommendations for disease-specific conditions but do not guide prescribers in prescribing for patients with multimorbidities.4 The rapid expansion of drug choices further complicates the situation as prescribers need to carefully deliberate the suitability of each treatment option for a particular patient in terms of cost, effectiveness and side effects.5

These challenges might lead to inappropriate prescribing for patients with chronic diseases which in turn lead to adverse drug events and poor disease control.6–8 Moreover, the majority of patients with chronic diseases are elderly who are at high risk for adverse drug events.9 10 Inappropriate prescribing for chronic diseases also has a significant economic impact due to increased hospitalisation, number of outpatient visits and medical costs.11–13 This is a major concern in the delivery of healthcare.14

In many health systems, chronic care is shifting from secondary to primary care with the aim to mitigate rising healthcare burdens in hospitals, as well as to improve the cost-effectiveness of healthcare delivery.15 16 Patients with chronic diseases often receive care from multiple practitioners and institutions and this requires a high level of coordination.16 17 Primary care practice plays an important role in integrating the care of these patients as a whole without focusing on a specific disease, organ or system. Primary care physicians (PCPs) are therefore responsible for managing complex medication regimens prescribed by different healthcare providers.

There is a considerable amount of literature available on the prevalence and factors associated with inappropriate prescribing in primary care.18–20 Others focused on specific disease conditions (eg, dementia),21 target groups (eg, elderly)9 11 22 or specific medications (eg, antidepressant).23 This failed to capture the real challenges faced by PCPs in managing patients with chronic diseases who mostly present with multimorbidities. Very few studies have specifically explored the challenges faced by PCPs when prescribing for patients with multiple chronic diseases. Therefore, this study aimed to identify the challenges faced by PCPs in prescribing for patients with chronic diseases in a teaching hospital in Malaysia.

Methods

Design and setting

Primary care services in Malaysia comprise of private general practices, government primary care clinics in the community and government primary care clinics within teaching hospitals. In this study, we conducted focus group discussions (FGDs) with PCPs from an urban primary care clinic located within a teaching hospital in Malaysia. The PCPs consisted of service medical officers, family medicine trainees and family medicine specialists, where family medicine trainees form the majority. Family medicine trainees are medical officers who are pursuing their 4-year training as a specialist in family medicine, while service medical officers are doctors who are employed to provide clinical services at the primary care clinic.

PCPs manage patients with both acute and chronic conditions. Patients attending the primary care clinic presented with a broad range of chronic conditions, as the clinic is located within a tertiary teaching hospital. Patients however may be attending other specialist clinics or health institutions located within or outside of our hospital for other chronic conditions. For example, a patient may be seen by an endocrinologist for his diabetes, a psychiatrist for depression and a PCP for hypertension. PCPs prescribed electronically but maintained paper-based medical records, which were kept separately and not shared with other clinicians within the hospital. Patients collected their prescribed medications from the hospital outpatient pharmacy at a subsidised rate.

A qualitative methodology was used in this study as it allowed us to have an in-depth understanding of the prescribing practice and challenges faced by PCPs when prescribing for patients with chronic diseases.24 FGDs were conducted instead of individual interviews as we felt that the group dynamics among peers would stimulate more fruitful and casual discussion on the topic.24

Participants, recruitment and sampling

Purposive sampling was performed to include PCPs with various lengths of clinical experience. We invited potential participants in person or through text message explaining the objectives, date, time and venue of the FGD. Twenty-two PCPs were approached, of which 19 agreed to participate. Three potential participants were not able to participate in the FGDs due to unavailability at the given FGD date and time. We ceased recruitment once no new themes emerged from the analysis (thematic saturation). PCPs were grouped according to their years of clinical experience to facilitate the sharing of ideas and experience among participants.24

Data collection

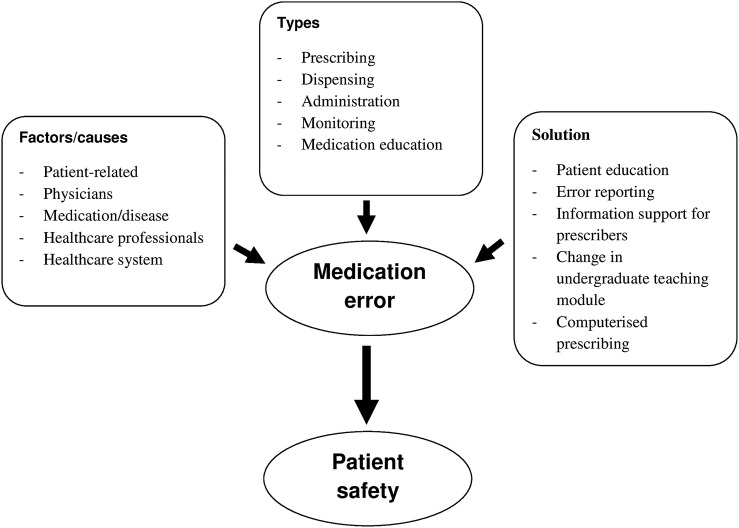

FGDs were conducted between July and August 2012. An academic family medicine specialist affiliated to the primary care clinic of the study site conducted the first FGD (CJN). The remaining two FGDs were conducted by RS, a trained researcher who was not an academic staff, and would therefore not be seen as an authoritative figure by participants. A topic guide (box 1) was developed based on a conceptual framework (figure 1) which was derived from literature review. It covered the types and causes of medication errors in primary care as well as available solutions. PCPs were provided with a participant information sheet prior to giving consent. They were reminded to discuss based on their experiences in managing patients with chronic diseases only and were assured that anonymity will be maintained throughout reporting. We asked open-ended questions and prompted them when important issues were not mentioned. All FGDs were conducted in English, audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Checked transcripts were used as data for analysis. Researchers documented relevant impressions and thoughts after each FGD, while a research assistant took field notes on non-verbal cues during the FGDs.

Box 1. Key topics in the interview guide.

-

What are the common medication errors that you encounter when managing patients with chronic diseases?

Prompts

Prescribing errors

Dispensing errors

Patients’ drug administration errors

Monitoring errors

Side effects

Medication education

-

In your opinion, what are the factors that lead to the medication errors mentioned above?

Prompts

Patient-related

Family

Healthcare system

Healthcare professional

Disease

Medication

-

In your opinion, how are these medication errors avoided in patients with chronic diseases?

Prompts

Education

Error reporting

Information support for prescribers

Undergraduate teaching module

Computerised prescribing

Role of pharmacist

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of types, causes and interventions to reduce medication errors in primary care.

Data analysis

We used thematic analysis to analyse the data, which was managed using a computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software Nvivo V.10 (QSR International Pty Ltd, Doncaster, Victoria, Australia). The data were analysed inductively starting with the first transcript. RS familiarised herself with the data by reading the first transcript to identify and index the themes.25 All data relevant to each theme were identified and examined through constant comparison.25 These themes were further refined and reduced in number by grouping them into larger categories.25 The research team (RS, CJN and PSML) met over several meetings to discuss the list of themes and categories, which were refined iteratively through consensus until the team agreed on the final coding framework. RS used the final coding framework to code the remaining two transcripts. New themes that emerged were added to the list on consultation with the research team. Thematic saturation occurred at the third FGD.

The research team consisted of a family medicine specialist (CJN) and two pharmacists (PSML and RS). All researchers were conscious of their personal and professional biases, and therefore constantly reflected and debated during data collection and analysis to improve the credibility of the data.

Results

Three FGDs were conducted, each lasting 50–100 min. Eight male and 11 female PCPs participated in this study, aged 30–62 years. Their years of clinical experience ranged from 5–37 years. Participants were grouped into year 3 family medicine trainees (n=7), year 4 family medicine trainees (n=7) and service medical officers (n=5).

The challenges faced by PCPs in prescribing for patients with chronic diseases are summarised in box 2.

Box 2. Challenges faced by primary care physicians when prescribing for chronic diseases.

Lack of communication among healthcare providers

Transition from paper to electronic prescribing

‘Doctor and pharmacy hopping’ by patients

Patients’ changing living and care arrangements

Dealing with patients’ beliefs, demands and medication-taking behaviour

Providing medication advice to patients

Managing complex drug regimens and side effects

Lack of communication among healthcare providers

Patients with multiple chronic diseases attended several specialists’ clinics as well as the primary care clinic for different conditions. A lack of communication between specialists and PCPs was a challenge when prescribing medications as changes in medication regimen by specialists were often not communicated to PCPs. For example, PCPs were also not informed of any changes made to patients’ medications during admission to the hospital. This increased the risk of drug duplications and interactions and might affect patient safety.

I have a patient that was actually under another clinic and under me. He was started on an ARB (angiotensin receptor blocker) and I was not aware of it. I started ACE (angiotensin-converting-enzyme) inhibitor. It happened because I did not know what was going on with the other clinic follow up. So, yeah! I am causing more harm to the patient because of poor records.

[D1, year 3 family medicine trainee]

When a patient was discharged from the ward, a lot of things can happen in the ward. They changed the medication for example. When they come (to see me), they do not have the records. So, we are quite stuck there.

[D14, year 4 family medicine trainee]

Transition from paper to electronic prescribing

The transition from paper to electronic prescribing (e-prescribing) has introduced a new challenge to PCPs prescribing practice. When PCPs prescribed electronically, they often did not document the medications that they had prescribed in the paper-based medical records. This became a problem when the e-prescribing system was inaccessible, as PCPs could not retrieve information on patients’ medication history. There were also some instances when the medication list on the paper records and the electronic records differed, and PCPs faced a dilemma as to which was the correct information to follow.

Some of us may not write down exactly what the patient is taking anymore because we are doing two jobs. We need to write the medication in the folder and prescribe in the computer. But when patients have 10 medications or so, it is quite a hassle to write down everything.

[D17, service medical officer]

And when the e-prescribing system is down, you check the patient folders and you find that it (medication list) is not updated. You then do not know what medications the patient is on.

[D19, service medical officer]

Sometimes, the medication list on e-prescribing and the notes (medical folders) is not the same and you don't know which one to trust.

[D4, year 3 family medicine trainee]

‘Doctor and pharmacy hopping’ by patients

Some patients were ‘doctor and pharmacy hopping’. They visited different doctors and community pharmacies for the same symptom. This became a problem when PCPs did not know what medications patients were prescribed (or supplied with), giving rise to the risk of drug duplication.

There are patients who are given some medications from our hospital pharmacy, and then they go outside of the hospital to get more medications. So that one you really can't control. We don't know what they are on. Sometimes they have duplicate medications. The brand is different, so they think it is a different medication.

[D13, year 4 family medicine trainee]

Patients’ changing living and care arrangements

In line with the Asian culture, most elderly patients live with their children. However, elderly patients who have several children are sometimes ‘rotated’ between the homes of different children. These elderly patients may then be accompanied by different carers to different doctors for their follow-up visits at different healthcare institutions. There was a lack of continuity of care and prescribing for this group of patients becomes a challenge.

I have a few patients who stay at their children's place of one month here, one month there and so on. And they don't bring their medication with them. So what happens is the son brings to one clinic and the daughter brings to another clinic. The patients end up with so many duplicate medications. They then come back to us with all those medications and we do not know which one is which anymore!

[D10, year 4 family medicine trainee]

Dealing with patients’ beliefs, demands and medication-taking behaviour

Patients had their own beliefs and preferences in starting, maintaining or changing their medications. While some patients requested more medications, some believed that modern medications are injurious to health and therefore reduced or stopped their medications. Patients also did not follow PCPs advice in altering the medications prescribed by specialists as they believed that the specialists knew better.

Sometimes patients say, I want medicine for this, I want medicine for that. And if we don't prescribe them, they become so upset. They are already on many medicines plus with all these medicines they want to take, there can be a lot of interactions.

[D10, year 4 family medicine trainee]

When you tell them (patients) to take 4 tablets, they think it is a large dose and will harm them. So they (patients) reduce the dose themselves.

[D19, service medical officer]

We are supposed to be the coordinator of their medication, but patients sometimes are reluctant to change the medication given by specialists. I have a patient attending the skin clinic for urticaria and treated with cetirizine. (Patient) also has allergic rhinitis, seen by ENT specialist and given loratadine. So I told the patient to take either one but she refused because the medications were given by specialists and they (specialists) know the best.

[D4, year 3 family medicine trainee]

Patients’ medication-taking behaviour also affected PCPs’ prescribing practice. Patients did not take their medications due to various reasons such as convenience and belief that their disease has been ‘cured’. Some patients took their spouses’ medications when they ran out of their own medications.

Sometimes we prescribe half a tablet daily…and they take one tablet every other day as they find it inconvenient to break the tablet into half.

[D2, year 3 family medicine trainee]

When we tell them (patients) that their cholesterol levels are normal, they will stop their (cholesterol) medication. They think that once it's normal, it will stay normal. So, they will stop themselves. They don't listen to our advice.

[D12, year 4 family medicine trainee]

Some patients even take their spouses’ medication when they run out of their own medication.

[D6, year 3 family medicine trainee]

Providing medication advice to patients

PCPs generally agreed that their role as prescriber includes advising patients on their medications. PCPs however struggled to do this due to lack of time during the consultation or lack of knowledge on proper use of medication.

During busy clinics we have no time to tell the patient what are the possible side effects of the medications. That can be considered as a prescribing error.

[D15, service medical officer]

Sometimes I do not know…when they are supposed to take the medicine, whether it is before meal or after meals. So I will tell them (patients) to check with the dispenser later.

[D1, year 3 family medicine trainee]

PCPs were also not aware of the dosage available at the pharmacy. The same medication that the patient is on might be dispensed at different strengths based on drug availability at the pharmacy. This has led to confusion among patients and drug administration errors in the home.

I feel that doctors should explain to the patient about what you are giving to the patient. But the problem is we (PCPs) don't know what is the dosage strength supplied to the patient. For example we prescribe 8 mg but patients are given 4 mg tablets. Since we told them (patients) to take 1 tablet, they took 1 tablet of the 4 mg and ended up with sub-optimal treatment.

[D7, year 3 family medicine trainee]

Managing complex drug regimens and side effects

The more comorbidities a patient has, the more complex his or her medication regimen becomes. When patients developed side effects to any of these medications, PCPs faced difficulties in identifying the causative agent and managing the side effects.

Side effect due to medication is a major problem, especially when the patient is on so many medications for a long time. It is very, very difficult for us to really identify which medication is causing the side effect.

[D3, year 3 family medicine trainee]

Discussion

Our study highlighted the prescribing challenges faced by PCPs in their daily practices when managing patients with chronic diseases. A lack of communication among healthcare providers and the transition from paper to e-prescribing were examples of healthcare system-related challenges. In addition, patients’ help-seeking behaviour, social context, belief and demands about medications and non-adherence to medication instructions influenced the prescribing patterns of PCPs. PCPs also faced difficulties in advising patients about medications and managing side effects due to complex medication regimens.

Lack of effective communication among healthcare providers was the main issue faced by most of the participants in this study. This problem however is not unique to the Malaysian healthcare system. Studies have identified a communication gap between primary and secondary care due to poorly documented and disorganised medical records.19 26 27 Our findings further suggest that this gap prevented PCPs from coordinating the care of patients with chronic diseases, potentially leading to prescribing errors affecting patient safety.19 27 28 Electronic medical records and patient-held records could be the possible solutions for this problem.29 30 By facilitating information sharing and improving the communication between different specialties, these technological interventions can assist the role of PCPs in coordinating the care of patients with multimorbidities.29 30

E-prescribing was introduced in an effort to improve prescribing practice and to reduce medication errors.31 Our study, however, highlights the problems associated with implementing a new computer system into practice. PCPs felt burdened as they needed to record patients’ medication twice, and therefore had the tendency to skip the paper records due to time constraints. This became a problem when the two records did not tally or when the e-prescribing system was not accessible. In future, PCPs adopting e-prescribing into practice should be made aware of this potential challenge during the transition phase, and the importance of proper paper records should be emphasised until e-prescribing is fully adopted into practice.

Similar to other studies, our participants struggled to advise patients about medications due to time constraints, high workload and lack of knowledge on proper drug use.32 33 It is however important to educate patients about their medications and promote adherence, as inappropriate medication use by patients is one of the main contributing factors of poor disease control and adverse drug events.7 34 35 PCPs can overcome this problem by working closely with pharmacists. The role of pharmacists in patient care has been expanding recently with more health systems promoting the integration of pharmacists into primary care.36 Besides improving the health and safety outcomes of patients with chronic diseases,37 38 this interprofessional collaboration could help to foster knowledge exchange and enhance safety netting in reducing medication errors.36 39 40

Another important factor that affects patient's medication use is their social circumstances. Patients are more likely to comply with a treatment regimen which causes minimal disruption to their present lifestyle.41 42 This was illustrated in one of the participants’ response which described how one patient self-adjusted his medication dose as it was inconvenient to break the tablet into half. Another example is when an elderly patient cared for by different children was brought to different institutions for medical treatment leading to duplicate medications. PCPs therefore should explore, consider and address patients’ social circumstances prior to prescribing to avoid medication errors.43

Multimorbidities and the resulting increase in number of prescribed medications have been identified in previous research as risk factors for adverse drug events.11 19 44–46 It was therefore not surprising that PCPs faced difficulties in identifying and managing side effects due to complex medication regimen. But this could also mean that PCPs lacked the knowledge and skills for doing so.19 27 28 PCPs should therefore be provided with adequate training in prescribing this specific group of patients in order to improve management of chronic diseases in primary care.

This study is one of the first to explore the challenges faced by PCPs in prescribing for patients with chronic diseases. This is an important first step in order to improve the care of this patient group. However, it should be noted that being part of a teaching hospital, there are more teaching involved and junior PCPs are constantly under the guidance and supervision of more senior PCPs and family medicine specialists. This could limit the applicability of our findings as the setting is different from the majority of primary care practices elsewhere.

No family medicine specialists were interviewed in this study, and their challenges and views could have been different from the medical officers and trainees that participated in our study. This study was part of a larger study which aimed to look at the problems and needs of PCPs, pharmacists and patients in medication management for chronic diseases in primary care. Many of the issues reported by PCPs in this study were related to pharmacists and patients. Therefore, the views from pharmacists and patients themselves are important to provide a clearer picture of the real challenge in medication use for chronic diseases in primary care. These findings will be reported separately.

Conclusions

PCPs faced multiple challenges related to the healthcare system, patients and themselves when prescribing for patients with chronic diseases. The lack of a conducive platform for interprofessional communication among healthcare providers was of particular concern and has significant implication on patient safety. It is therefore imperative to investigate and establish effective interventions to enhance interprofessional collaboration with the aim of improving patient care in chronic diseases management.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their appreciation to all the participants for agreeing to spend time participating in this study despite their busy schedule.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors were involved in designing the study and developing the methods. RS and PSML obtained funding and ethics approval. CJN conducted the first FGD. RS coordinated the running of the study, conducted the remaining two FGDs, checked, read and coded the transcripts. All authors were involved in developing the analytical framework and contributed to the analysis. RS drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the analysis and critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study was funded by University of Malaya postgraduate research grant PV018/2012A.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: University Malaya Medical Centre Medical Ethics Committee (Ref. No. 890.104).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M et al. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. Lancet 2012;380:37–43. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60240-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hunt LM, Kreiner M, Brody H. The changing face of chronic illness management in primary care: a qualitative study of underlying influences and unintended outcomes. Ann Fam Med 2012;10:452–60. 10.1370/afm.1380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roberts ER, Green D, Kadam UT. Chronic condition comorbidity and multidrug therapy in general practice populations: a cross-sectional linkage study. BMJ Open 2014;4:e005429 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyd CM, Darer J, Boult C et al. Clinical practice guidelines and quality of care for older patients with multiple comorbid diseases: implications for pay for performance. JAMA 2005;294:716–24. 10.1001/jama.294.6.716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hill J. Prescribing in type 2 diabetes: choices and challenges. Nurs Stand 2010;25:55–8. 10.7748/ns2010.10.25.5.55.c8025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gandhi TK, Weingart SN, Borus J et al. Adverse drug events in ambulatory care. N Engl J Med 2003;348:1556–64. 10.1056/NEJMsa020703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kunac DL, Tatley MV. Detecting medication errors in the New Zealand pharmacovigilance database: a retrospective analysis. Drug Saf 2011;34:59–71. 10.2165/11539290-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sarkar U, Handley MA, Gupta R et al. What happens between visits? Adverse and potential adverse events among a low-income, urban, ambulatory population with diabetes. Qual Saf Health Care 2010;19:223–8. 10.1136/qshc.2008.029116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gurwitz JH, Field TS, Harrold LR et al. Incidence and preventability of adverse drug events among older persons in the ambulatory setting. JAMA 2003;289:1107–16. 10.1001/jama.289.9.1107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olaniyan JO, Ghaleb M, Dhillon S et al. Safety of medication use in primary care. Int J Pharm Pract 2015;23:3–20. 10.1111/ijpp.12120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akazawa M, Imai H, Igarashi A et al. Potentially inappropriate medication use in elderly Japanese patients. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 2010;8:146–60. 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2010.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuo GM, Phillips RL, Graham D et al. Medication errors reported by US family physicians and their office staff. Qual Saf Health Care 2008;17:286–90. 10.1136/qshc.2007.024869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lau DT, Kasper JD, Potter DE et al. Hospitalization and death associated with potentially inappropriate medication prescriptions among elderly nursing home residents. Arch Intern Med 2005;165:68–74. 10.1001/archinte.165.1.68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS. To err is human: building a safer health system. Washington DC: Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Starfield B. Primary care: balancing health needs, services and technology. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rothman AA, Wagner EH. Chronic illness management: what is the role of primary care? Ann Intern Med 2003;138:256–61. 10.7326/0003-4819-138-3-200302040-00034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vogeli C, Shields AE, Lee TA et al. Multiple chronic conditions: prevalence, health consequences, and implications for quality, care management, and costs. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22(Suppl 3):391–5. 10.1007/s11606-007-0322-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahmad F, Ismail SB, Yusof HM. Prescription errors in Hospital Universiti Sains Malaysia, Kelantan, Malaysia. Int Med J 2006;13:101–4. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen YF, Avery AJ, Neil KE et al. Incidence and possible causes of prescribing potentially hazardous/contraindicated drug combinations in general practice. Drug Saf 2005;28:67–80. 10.2165/00002018-200528010-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dhabali AA, Awang R, Zyoud SH. Pharmaco-epidemiologic study of the prescription of contraindicated drugs in a primary care setting of a university: a retrospective review of drug prescription. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 2011;49:500–9. 10.5414/CP201524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lau DT, Mercaldo ND, Harris AT et al. Polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate medication use among community-dwelling elders with dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2010;24:56–63. 10.1097/WAD.0b013e31819d6ec9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carey IM, De Wilde S, Harris T et al. What factors predict potentially inappropriate primary care prescribing in older people? Analysis of UK primary care patient record database. Drugs Aging 2008;25:693–706. 10.2165/00002512-200825080-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coupland CA, Dhiman P, Barton G et al. A study of the safety and harms of antidepressant drugs for older people: a cohort study using a large primary care database. Health Technol Assess 2011;15:1–202, iii–iv 10.3310/hta15280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bowling A. Qualitative and combined research methods, and their analysis. England: McGraw-Hill, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. Analysing qualitative data. BMJ 2000;320:114–16. 10.1136/bmj.320.7227.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO et al. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA 2007;297:831–41. 10.1001/jama.297.8.831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ramaswamy R, Maio V, Diamond JJ et al. Potentially inappropriate prescribing in elderly: assessing doctor knowledge, confidence and barriers. J Eval Clin Pract 2011;17:1153–9. 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01494.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Slight SP, Howard R, Ghaleb M et al. The causes of prescribing errors in English general practices: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract 2013;63:713–20. 10.3399/bjgp13X673739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.DesRoches CM, Campbell EG, Rao SR et al. Electronic health records in ambulatory care—a national survey of physicians. N Engl J Med 2008;359:50–60. 10.1056/NEJMsa0802005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ko H, Turner T, Jones C et al. Patient-held medical records for patients with chronic disease: a systematic review. Qual Saf Health Care 2010;19:1–7. 10.1097/QMH.0b013e3181d1391c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ammenwerth E, Schnell-Inderst P, Machan C et al. The effect of electronic prescribing on medication errors and adverse drug events: a systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2008;15:585–600. 10.1197/jamia.M2667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ostbye T, Yarnall KS, Krause KM et al. Is there time for management of patients with chronic diseases in primary care? Ann Fam Med 2005;3:209–14. 10.1370/afm.310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tarn DM, Heritage J, Paterniti DA et al. Physician communication when prescribing new medications. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1855–62. 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rasmussen JN, Chong A, Alter DA. Relationship between adherence to evidence-based pharmacotherapy and long-term mortality after acute myocardial infarction. JAMA 2007;297:177–86. 10.1001/jama.297.2.177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stempel DA, Roberts CS, Stanford RH. Treatment patterns in the months prior to and after asthma-related emergency department visit. Chest 2004;126:75–80. 10.1378/chest.126.1.75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dolovich L, Pottie K, Kaczorowski J et al. Integrating family medicine and pharmacy to advance primary care therapeutics. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2008;83:913–17. 10.1038/clpt.2008.29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carter BL, Bergus GR, Dawson JD et al. A cluster randomized trial to evaluate physician/pharmacist collaboration to improve blood pressure control. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2008;10:260–71. 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2008.07434.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nkansah NT, Brewer JM, Connors R et al. Clinical outcomes of patients with diabetes mellitus receiving medication management by pharmacists in an urban private physician practice. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2008;65:145–9. 10.2146/ajhp070012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Williams ME, Pulliam CC, Hunter R et al. The short-term effect of interdisciplinary medication review on function and cost in ambulatory elderly people. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004;52:93–8. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52016.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zarowitz BJ, Stebelsky LA, Muma BK et al. Reduction of high-risk polypharmacy drug combinations in patients in a managed care setting. Pharmacotherapy 2005;25:1636–45. 10.1592/phco.2005.25.11.1636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vermeire E, Hearnshaw H, Van Royen P et al. Patient adherence to treatment: three decades of research. A comprehensive review. J Clin Pharm Ther 2001;26:331–42. 10.1046/j.1365-2710.2001.00363.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nair KM, Levine MA, Lohfeld LH et al. “I take what I think works for me”: a qualitative study to explore patient perception of diabetes treatment benefits and risks. Can J Clin Pharmacol 2007;14:e251–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bajcar JM, Kennie N, Einarson TR. Collaborative medication management in a team-based primary care practice: an explanatory conceptual framework. Res Social Adm Pharm 2005;1:408–29. 10.1016/j.sapharm.2005.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guthrie B, McCowan C, Davey P et al. High risk prescribing in primary care patients particularly vulnerable to adverse drug events: cross sectional population database analysis in Scottish general practice. BMJ 2011;342:d3514 10.1136/bmj.d3514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hanlon JT, Schmader KE, Koronkowski MJ et al. Adverse drug events in high risk older outpatients. J Am Geriatr Soc 1997;45:945–8. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb02964.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Laroche ML, Charmes JP, Nouaille Y et al. Is inappropriate medication use a major cause of adverse drug reactions in the elderly? Br J Clin Pharmacol 2007;63:177–86. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02831.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]