Abstract

The growing insight into the biological role of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) under physiological and pathological condition and the role it presumably plays in the action of natural and synthetic redox-active drug imparts a need to accurately define the type and magnitude of reactions which may occur with this intriguing and key species of redoxome. Historically, and frequently incorrectly, the impact of catalase-like activity has been assigned to play a major role in the action of many redox-active drugs most so SOD mimics and peroxynitrite scavengers, and in particular MnTBAP3− and Mn salen derivatives. The advantage of one redox-active compound over another has often been assigned to the differences in catalase-like activity. Our studies provide substantial evidence that Mn(III) N-alkylpyridylporphyrins couple with H2O2 in actions other than catalase-related. Herein we have assessed the catalase-like activities of different classes of compounds: Mn porphyrins (MnPs), Fe porphyrins (FePs), Mn(III) salen (EUK-8) and Mn(II) cyclic polyamines (SOD-active M40403 and SOD-inactive M40404). Nitroxide (Tempol), nitrone (NXY-059), ebselen and MnCl2, which have not been reported as catalase-mimics, were used as negative controls, while catalase enzyme was a positive control. The dismutation of H2O2 to O2 and H2O was followed via measuring oxygen evolved with Clark oxygen electrode at 25°C. The catalase enzyme was found to have kcat(H2O2) = 1.5 × 106 M−1 s−1. The yield of dismutation, i.e. the amount of O2 evolved, was assessed also. The magnitude of the yield reflects an interplay between the kcat(H2O2) and the stability of compounds towards H2O2-driven oxidative degradation, and is thus an accurate measure of the efficacy of an catalyst. The kcat(H2O2) values for 12 cationic Mn(III) N-substituted (alkyl and alkoxyalkyl) pyridylporphyrin-based SOD mimics and Mn(III) N,N’-dialkylimidazolium porphyrin, MnTDE-2-ImP5+ ranged from 23 to 88 M−1 s−1. The analogous Fe(III) N-alkylpyridylporphyrins showed ~10-fold higher activity than the corresponding MnPs, but the values of kcat(H2O2) are still ~4 orders of magnitude lower than that of the enzyme. While the kcat(H2O2) values for Fe ethyl and n-octyl analogs were 830 and 360 M1 s−1, respectively, the FePs are more prone to H2O2-driven oxidative degradation therefore allowing for similar yields in H2O2 dismutation as analogous MnPs. The kcat(H2O2) values are dependent upon the electron deficiency of the metal site as it controls the peroxide binding in the 1st step of dismutation process. SOD-like activities depend upon electron-deficiency of the metal site also, as it controls the 1st step of O2.− dismutation. In turn, the kcat(O2.−) parallels the kcat(H2O2). Therefore, the electron-rich anionic non-SOD mimic MnTBAP3− has essentially very low catalase-like activity, kcat(H2O2) = 5.8 M−1 s−1. The catalase-like activity of Mn(III) and Fe(III) porphyrins are at most, 0.0004% and 0.05% of the enzyme activity, respectively. The kcat(H2O2) of 8.2 and 6.5 M−1 s−1 were determined for electron-rich Mn(II) cyclic polyamine-based compounds, M40403 and M40404, respectively. The EUK-8, with modest SOD-like activity, has only slightly higher kcat(H2O2) = 13 M−1s−1. The biological relevance of kcat(H2O2) of MnTE-2-PyP5+, MnTDE-2-ImP5+, MnTBAP3−, FeTE-2-PyP5+, M40403, M40404 and Mn Salen was evaluated in wild type and peroxidase/catalase-deficient E. coli.

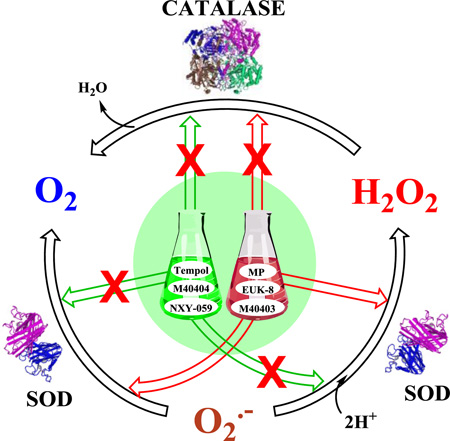

Graphical abstract

Introduction

H2O2 plays a critical role in metabolic processes under physiological and pathological conditions due to its longevity, neutrality and ability to cross membranes [1]. As a messenger it is in the forefront of cellular transcription [1, 2]. Its signaling effects have been extensively addressed in Methods in Enzymology 2013, vol 527. H2O2 also plays a therapeutic role; along with its progeny H2O2 is involved in cancer killing via chemo- and radiotherapy [3, 4]. It deserves mentioning that even H2O2, in its own right, was used as a treatment in stroke therapy supposedly inducing adaptive response [5]. Nature has developed multiple redundant systems to maintain H2O2 at nM intracellular levels which are sufficient enough for its role in cellular signaling. Such are families of glutathione peroxidases (GPx), glutathione reductases, catalases, peroxiredoxins, thioredoxin reductases, glutathione S-transferases, etc. Our first line of defense against oxygen toxicity and an ultimate requirement of all aerobic life is a family of superoxide dismutases, SODs. During the catalysis of O2.− dismutation by enzyme or its mimic (eq (1)) O2.− is oxidized one-electronically into O2 and reduced into H2O2. In order for SOD enzymes to be considered antioxidative systems, the H2O2 production needs to be coupled to its elimination. H2O2 is either reduced 2-electronically into H2O via peroxidases, or dismuted, i.e. oxidized 2-electronically to O2 and reduced to H2O via catalases (eq (2)).

| (1) |

| (2) |

A fine coupling of SODs and H2O2-removing systems exists under physiological conditions but gets perturbed under pathological conditions and frequently in cancer resulting in increased H2O2 levels. The state of oxidative stress and its implications on tumor biology and treatment have been addressed in numerous reports [6–14].

Redox-active drugs, either of synthetic nature such as metalloporphyrins, Mn(III) salens, Mn(III) cyclic polyamines, nitroxides, nitrones, MitoQ, or of natural sources (e.g. flavonoids, catechols) reportedly interfere either directly or indirectly with components of the cellular redox environment, redoxome [15]. Over the last 20 years, our knowledge on redox-active drugs, in particular SOD mimics, has increased and has been summarized in several reviews [8, 16–22]. The small molecular structure of SOD mimics, unlike that of the enzymes, allows them to interact rapidly with many other targets. Mn porphyrin-based SOD mimics are powerful antioxidants, reducing small molecules such as O2, O2.−, ONOO−, CO3.− and ClO−. Yet they also act as pro-oxidants, oxidizing biological targets such as O2.−, thiols (both simple thiols such as glutathione and cysteine and protein thiols), tetrahydrobioterin and ascorbate [21]. Further, Mn porphyrins are able to employ H2O2 to catalyze S-glutathionylation of thiols of signaling proteins affecting in turn cellular transcription. The S-glutathionylation of p50 and p65 subunits of NF-κB [20, 21, 23], as well as complexes I, III and IV of mitochondrial respiration has been reported [21, 24].

Numerous reports have been published on catalase-like (eq (2)) and/or joint catalase- and SOD-like activities (eq (1)) of metalloporphyrins (in particular MnTBAP3− and MnTM-4-PyP5+) and Mn salen compounds; such claims have been used to justify the involvement of O2.− or H2O2 in proposed pathways, while frequently compounds lacked either one or both activities [13, 25–41]. We have therefore decided to quantify the ability of different classes of redox-active compounds (some of whom are potent SOD mimics) to catalyze the H2O2 dismutation (eq (2)). Our goal has been to provide clear evidence that compounds currently used (or misused) as SOD mimics do not possess ability to catalyze H2O2 dismutation to any practical biologically-relevant extent. Yet, H2O2 seems to have major role in biology of metalloporphyrins and their therapeutic effects via pathways discussed elsewhere [21, 42–44].

Experimental

Materials and Methods

Redox-active compounds

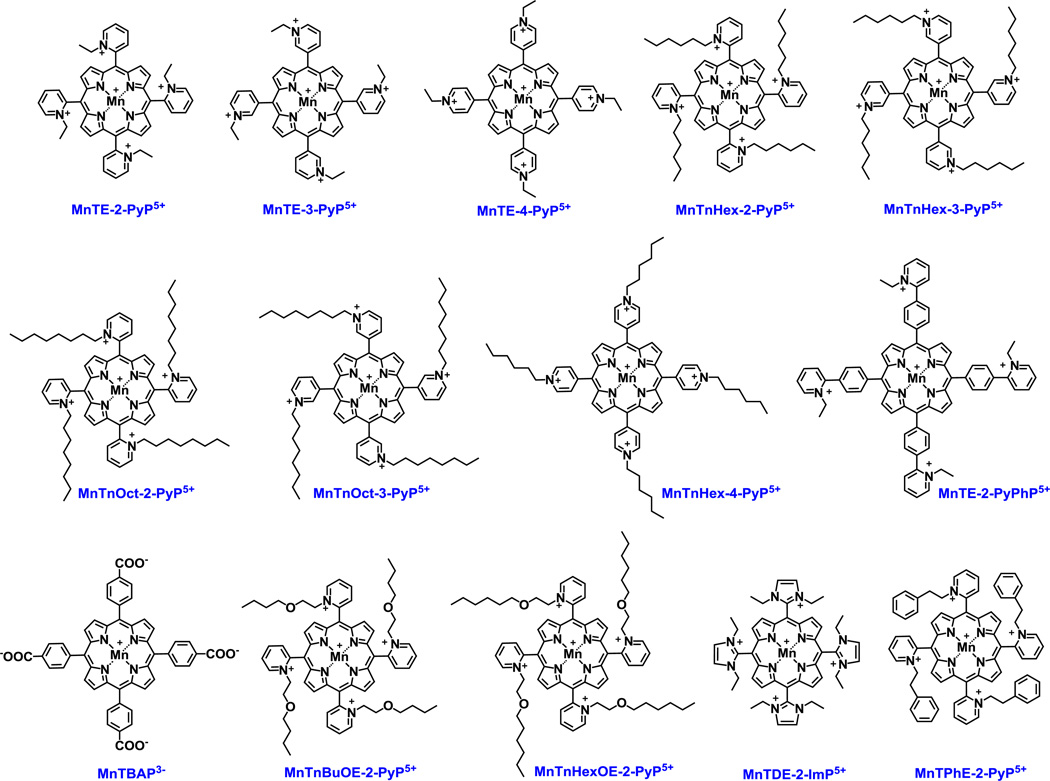

SOD mimics and non-SOD mimics were analyzed. Mn-, Fe porphyrins, Mn Salen and EUK-8 were synthesized as reported [45–50]. Mn(II) cyclic polyamines, M40403 and M40404 were synthesized based on the literature procedures [51]. Nitrone NXY-059 was purchased from Selleckchem, Cat No. S6002, >99 % and nitroxide, Tempol, was obtained from Enzo, Cat No. ALX-430-081-G001, Lot No. L27338C. Catalase enzyme from bovine liver was bought from Sigma, Cat No. C1345-1G, Lot No. 010M7011V. Ebselen was purchased Cayman Chemical Company, Cat No. 70530, Lot No. 0406449-57. Figure 1 shows the structures of Mn porphyrins and Figure 2 the structures of other redox-active drugs studied here.

Figure 1. Structures of the Mn(III) porphyrins whose catalase-like activity was assessed herein.

Different Mn porphyrins are studied, and except MnTBAP3− and MnTE-2-PyPhP5+, all are SOD mimics of similarly high kcat(O2.−). Their SOD-like activity is controlled by the close vicinity (ortho position indicated with number 2) of either pyridyl (Py) or imidazolyl (Im) nitrogens to the metal site which controls kinetics and thermodynamics of the reactions of those Mn complexes with reactive species [13]. The data on those compounds are listed in Tables 1 and 3.

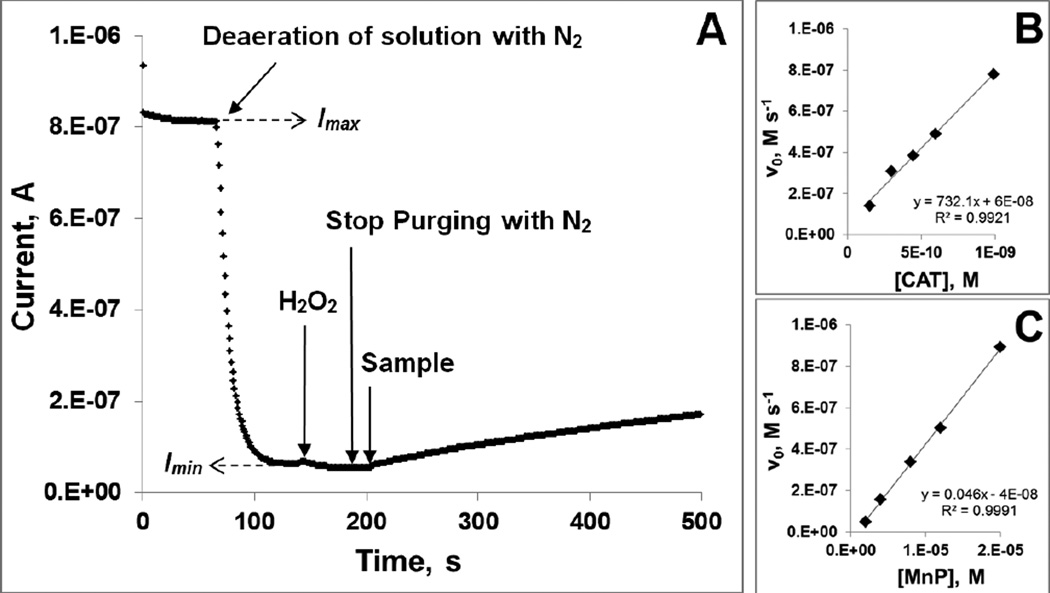

Figure 2. Structures of other redox-active drugs whose catalase-like activity was assessed herein.

Compounds include SOD mimics of different magnitudes of SOD-like activities, such as Fe porphyrins, as well as compounds such as nitrones and nitroxides which are not SOD mimics but can cycle with other reactive species whereby eventually removing O2.− also [19]. Nitrone can trap free radicals such as O2.− and form nitroxide and thus affect O2.− levels. Nitroxide in turn can be oxidized with CO3.− to oxoammonium cation which then rapidly oxidizes O2.− closing the catalytic cycle. Mn(II) cyclic polyamine, M40403 is a very potent SOD mimic, but its SOD-inactive analog, M40404, is not. If Mn complexes fall apart they would release Mn. Moreover Mn(II) low molecular weight complexes, and in particular Mn(II) lactate, are SOD mimics also [19, 21]. The kinetic and thermodynamic data on these compounds are listed in Tables 2 and 3. The data for Fe corrole are taken from literature [19, 21, 52, 53].

Assessing the ability of redox-active drugs to catalyze H2O2 dismutation

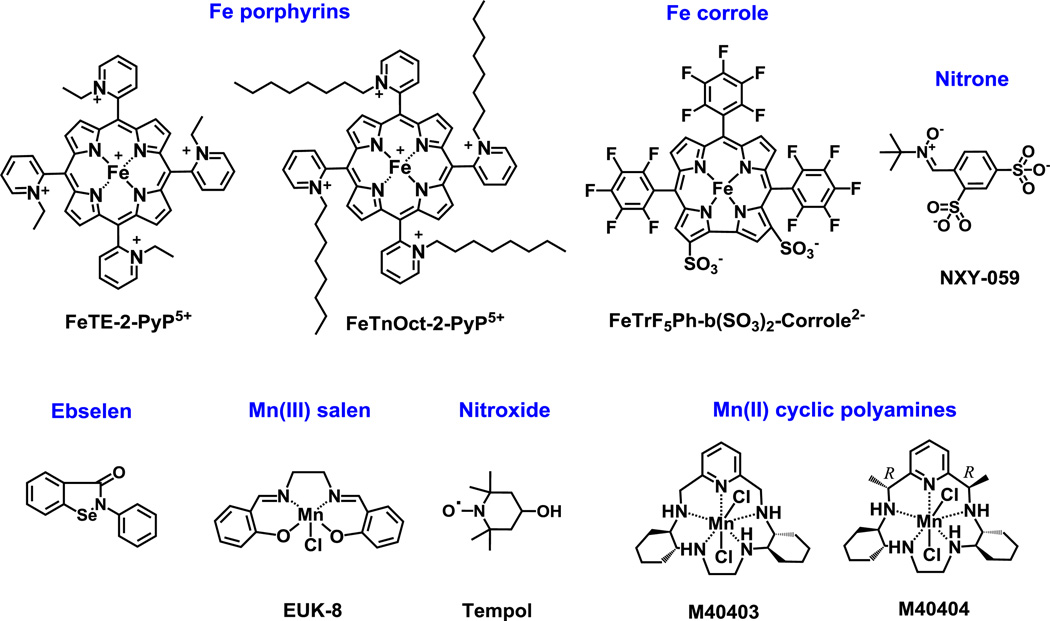

The experiments were carried out at (25±1)°C in 0.05 M tris buffer, pH 7.8, 0.1 mM EDTA. Prior to measurements, the solutions were purged with air (~21% oxygen). The O2-sensitive Clark electrode (0.1 M KCl as filling solution) connected to a potentiostat was used. A potential of E = −0.8 V vs Ag/AgCl was applied to the electrode and once the initial current was stabilized (Imax, corresponding to the [O2] = 0.255 mM [54] in air-saturated solution), the solution was purged with N2 until the current was stabilized again (Imin, corresponding to the [O2] ≈ 0 mM). This allows the calculation of O2 concentration in the solution (in µM) as [O2]obs = ((Iobs − Imin) × 255) / (Imax − Imin), where Iobs is the current observed at any given time after purging. This calibration procedure is followed by the addition of H2O2 up to 1 mM concentration, whereas the redox-active drugs or catalase were then added at 2–20 µM or 0.1–1 pM, respectively, to start the dismutation reaction (eq (2)). The increase in current, Iobs, corresponding to the increase of O2 concentration, Δ[O2], as a function of time was followed for at least 300 s. The initial reaction rate, ν0 = kcat [catalyst]0 [H2O2]0, was calculated from the slope of the initial linear kinetics as ν0 = ([O2]obs(t2) − [O2]obs(t1)) / (t2-t1). Under pseudo first-order conditions, kcat [H2O2]0 = kobs, and the ν0 = kobs [catalyst]0. When the values of ν0 were plotted against the catalyst concentrations, the slope, kobs, is obtained. Finally, since Δ[H2O2] = 2 Δ[O2], then the second order rate constant in M−1 s−1, could be calculated as kcat = 2 kobs / [H2O2]0. The data obtained for Mn porphyrin, MnTnBuOE-2-PyP5+ and for catalase itself are presented in Figure 3. Under identical conditions, when 0.05 M tris buffer was replaced with 0.05 M potassium phosphate buffer, no significant difference in kinetic parameters was observed for interaction of ortho, meta, and para isomers of MnTEPyP with H2O2.

Figure 3. Assessment of the catalase-like activity of redox-active therapeutics.

Experimental set-up for the determination of catalase-like activity (A); The determination of the kobs from the dependence of initial rates, ν0 on the concentration of either catalase enzyme (B) or MnTnBuOE-2-PyP5+ (C). Experiments were carried out at (25±1)°C in 0.05 M tris buffer, pH 7.8 and 0.1 mM EDTA.

The other parameters that describe the catalysis of H2O2 dismutation by redox-active compounds are the turnover number (TON), which describes the maximal yield of O2 evolution (thus yield of H2O2 dismutation, in %), and turnover frequency (TOF). Briefly, the reaction run under same experimental conditions as described above with 20 µM catalyst and 1 mM H2O2, was followed until no further evolution of O2 was registered. This maximal amount of O2 evolved (in µM), [O2]max, was calculated as: [O2]max = ((Iobs − Imin) × 255) / (Imax − Imin), where Iobs is the current observed at maximal point of O2 evolution, and Imax and Imin currents corresponding to air-saturated and N2-purged solutions, respectively. The maximal yield of O2 production (in %) was further calculated as % yield (O2) = ([O2]max / 500) × 100%, where 500 corresponds to [H2O2]0 / 2 = 500 µM, i.e. the maximal possible O2 concentration. TON was calculated as maximal number of O2 moles produced per mole of a catalyst. Initial rates for the reactions, calculated from the slopes of initial linear segments of kinetic curves, were expressed in µM s−1. The TOF values (s−1), which present the ratios of initial rates and concentrations of catalysts, are given in Table 3.

Table 3. The reduction potential E1/2 vs NHE, kcat(H2O2) for the catalysis of H2O2 dismutation and log kcat(O2.−) for the catalysis of O2.− dismutation of various redox-active compounds and catalase.

If not indicated, the data are taken from [19, 21, 22, 49, 50]. The catalysis of H2O2 dismutation was followed in 0.05 M tris buffer at (25±1) °C with Clark oxygen electrode. In case of Fe(III) porphyrins, Mn(III) salen and Mn(II) cyclic polyamines the E1/2 relates to the MIII/MII redox couple, while it relates to MIV/MIII redox couple in case of Fe(III) corrole. The catalysis of O2.− dismutation was followed in 0.05 M potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.8 at (25±1) °C as described in references [49, 50, 83]. The kcat(H2O2) value for Fe corrole was determined at 37 °C [53], while kcat(O2.−) was measured at (25±1) °C [52].

| Compound | E1/2, mV vs NHE | kcat (H2O2), M−1 s−1 | log kcat (O2.−) |

|---|---|---|---|

| FeTE-2-PyP5+, a | +211 | 803.5 | 8.05 |

| FeTnOct-2-PyP5+, a | +261 | 368.4 | 7.09 |

| FeTrF5Ph-β(SO3)2-corrole2− | +1050b | 6400c | 6.48d |

| MnCl2 | +850e | none | 6.11–6.95 |

| Mn Salen, EUK-8 | +130 | 13.5 | 6.36f |

| M40403 | +525(ACN) | 8.2 | 7.08 |

| M40404 | +452(ACN) | 6.5 | none |

| Nitroxide, Tempol | +810g | none | < 3 at pH 7.8 |

| Nitrone, NXY-059 | none | ||

| Ebselen | none | ||

| Catalase enzyme | 1.5 × 106 |

Degradation of MnPs with H2O2

The degradation of MnTE-2-PyP5+, MnTnBuOE-2-PyP5+, MnTnHex-2-PyP5+, MnTnOct-2-PyP5+, MnTnHexOE-2-PyP5+, MnTDE-2-ImP5+ and MnTBAP3− was followed in 0.05 M tris buffer, pH 7.8, 0.1 mM EDTA at (25±1)°C. 10 µM MnPs were mixed with 0.5 mM H2O2 and the absorbance at Soret band was followed for 60 s.

Evaluation of the redox-active drugs in an E. coli model of H2O2-induced damage

Ability of selected compounds to protect cells against damage imposed by H2O2 was tested on the following E. coli strains: GC4468 (F−Δlac U169 rpsL), provided by Dr. D. Touati (Institute Jacques Monod, CNRS, Paris, France); AB1157 [F− thr-1 leuB6 proA2 his-4 thi-1 argE2 lacY1 galK2 rpsL surE44 ara-14 xyl-15 mtl-1 tsx-33]; MG1655, F− lambda- ilvG-rfb-50 rph-1 (parental to LC106), LC106 [same as MG1655 plus Δ(ahpC-ahpF′) kan::′ahpF Δ(katG17::Tn10)1 Δ(katE12::Tn10)1] [55] provided by Dr. J. Imlay (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL). Representative compounds were analyzed: MnTE-2-PyP5+, MnTDE-2-ImP5+, MnTBAP3−, FeTE-2-PyP5+, M40403, M40404, Mn Salen and Tempol. Overnight cultures were grown in Luria-Bertoni (LB) medium. They were then diluted to OD600 ~ 0.01 with the same medium and grown to early log phase. Cultures were then diluted with LB medium to OD700 0.08 and were either not incubated or incubated for 60 min with or without 20 µM of the tested compounds; OD at 700 was used to avoid interference with the absorbance of the compounds. Since the effect of H2O2 depends on the number of cells, cultures were diluted after incubation to an OD700 value of exactly 0.08. Then 100 µl aliquots were placed in a 96-well plate. After incubation with compounds cells were washed with PBS. To half of the wells H2O2 was added at a final concentration of 5.0 mM for the parental and 0.5 mM for the mutant cells. Plates were incubated 15 minutes at 37°C on a shaking (200 rpm) platform. At the end of the incubation 1,000 units/ml of catalase were added to each well to stop the action of H2O2. Controls incubated without any additions, with compounds only, with H2O2 only, and with catalase added before H2O2, were run in parallel. Varying the length of pre-incubation of cultures with MnPs (up to 3 hours) or using E. coli with different genetic backgrounds (GC4468 and AB1157) did not change the outcome of study. The same results were obtained when viability was assessed by plating and counting colonies.

Toxicity of H2O2 (and hence possible protection by compounds of interest) was assessed by the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) test and by plating and counting colonies. The MTT test was carried out as described previously [56]. Formazan crystals were solubilized with 10% SDS in 10 mM HCl. At the end of the incubation 10 µl of MTT reagent (25 mg MTT in 5.0 ml PBS) were added to all wells. The plates were incubated in dark for 30 min on a shaker at 37°C. Afterwards, the 100 µl aliquots of SDS solution (10% SDS in 10 mM HCl) were added to each well and plates were incubated for 1 h at room temperature. The absorbance of each well was measured at 570 nm and 700 nm (background) using a microplate reader. For plating and counting colonies, after treatment samples were diluted in sterile PBS and plated on LB plates solidified with 1.5% agar. Colonies were counted 24 and 48 hours later. Student t-test was used to determine statistical significance. Results are presented as mean ± S.E.

Accumulation of MnTE-2-PyP5+ and FeTE-2-PyP5+ in E. coli

Mn porphyrins were incubated with LC106, catalase/peroxidase mutant in LB medium for 1 hour with 20 µM of either MnTE-2-PyP5+ or FeTE-2-PyP5+. The cells were then washed, centrifuged and the pellet suspended in 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate. The uv/vis spectral analysis was performed as described in [57].

Results and discussion

The following thermodynamic and kinetic data on metalloporphyrins are summarized in Table 1: rate constants for the catalysis of H2O2 dismutation, kcat(H2O2) in M−1 s−1; log values of the rate constants for the catalysis of O2.− dismutation, log kcat(O2.−); proton dissociation constants for the first axial water, pKa(ax); proton dissociation constants for the 3rd basic pyrrolic nitrogen proton of the corresponding metal-free porphyrin, pKa3; and the metal-centered reduction potentials, E1/2 in mV vs NHE, for MnIIIP/MnIIP redox couple. The data for other redox active therapeutics on the catalysis of dismutation of O2.− and H2O2, along with relevant reduction potentials are provided in Table 2. The kcat(H2O2) for catalase enzyme was determined in parallel under same experimental conditions to allow for comparison. Some of the data are determined in this work, while the others are taken from literature for the sake of discussion. Among Mn porphyrins, only ortho cationic Mn(III) and Fe(III) N-substituted pyridylporphyrins and di-ortho Mn(III) N,N’-diethylimidazolylporphyrin, MnTDE-2-ImP5+ have minor catalase-like activity, described by kcat(H2O2), ranging between 0.0004 and 0.05 % of enzyme activity. MnTBAP3− has often been incorrectly described as SOD and catalase-mimic and was frequently misused in studies with a goal to provide the evidence for the involvement of O2.− and H2O2 in pathways explored. It has no SOD-like activity and 10-fold lower kcat(H2O2) than the cationic MnPs such as MnTE-2-PyP5+ [28, 58]. MnTBAP3− possesses modest ability to reduce ONOO− [17, 58–61]. Recently Doctorovich’s group reported that MnTBAP3− reacts rapidly with HNO [62]. Future research will hopefully address the origin of the therapeutic effects continuously demonstrated with MnTBAP3−; for details on possible mechanisms involved in its therapeutic efficacy see also reference [58].

Table 1. The metal-centered reduction potential E1/2 vs NHE for MnIIIP/MnIIP, kcat(H2O2) for the catalysis of H2O2 dismutation in M−1 s−1, log kcat(O2.−) for the catalysis of O2.− dismutation, the proton dissociation constant for 1st axial water of metalloporphyrins, pKa(ax) and the proton dissociation constant for the 3rd basic pyrrolic nitrogen proton of the corresponding metal-free porphyrin, pKa3.

The catalysis of H2O2 dismutation by MnPs was followed in 0.05 M tris buffer, pH 7.8 at (25±1)°C by Clark oxygen electrode. The values for the catalysis of O2.− dismutation, determined by cyt c assay in 0.05 M potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.8 at 25±1°C, are taken from [19, 21, 49, 50]. All E1/2 values for MnIIIP/MnIIP redox couple are reported vs the normal hydrogen electrode (NHE), using the potential of MnTE-2-PyP5+, E1/2 = + 228 mV vs NHE at pH 7.8, as a reference.

| N | Compound | E1/2 (MnIIIP/MnIIP), mV vs NHE | log kcat (O2.−)a | kcat (H2O2), M−1 s−1 | pKa(ax) | pKa3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH 7.8 | pH 7.8 | pH 7.8 | ||||

| 1 | MnTBAP3− | −194 | 3.16 | 5.84 | 12.6 | 5.5 |

| 2 | MnTE-2-PyPhP5+ | −65 | 5.55 | 21.10 | 12.1 | |

| 3 | MnTE-3-PyP5+ | 54 | 6.65 | 63.25 | 11.5 | ~1.8 |

| 4 | MnTE-4-PyP5+ | 70 | 6.86 | 52.08 | ~11.6 | ~1.4 |

| 5 | MnTnHex-3-PyP5+ | 66 | 6.64 | 46.21 | ~11.5 | |

| 6 | MnTnHex-4-PyP5+ | 68 | 6.75 | 59.05 | ~11.6 | |

| 7 | MnTnOct-3-PyP5+ | 74 | 6.53 | 67.44 | ~11.5 | |

| 8 | MnTE-2-PyP5+ | 228 | 7.76 | 63.32 | 10.7 | −0.9 |

| 9 | MnTPhE-2-PyP5+ | 259 | 7.66 | 23.54 | ~10.8 | |

| 10 | MnTnBuOE-2-PyP5+ | 277 | 7.83 | 88.47 | 10.7 | |

| 11 | MnTnHexOE-2-PyP5+ | 313 | 7.92 | 34.66 | 10.6 | |

| 12 | MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ | 314 | 7.48 | 28.31 | 11.0 | |

| 13 | MnTnOct-2-PyP5+ | 340 | 7.71 | 27.62 | 10.7 | |

| 14 | MnTDE-2-ImP5+ | 346 | 7.83 | 27.59 |

in the absence of SOD enzyme, O2.− self-dismutes at pH 7.8 with rate constant of log k(O2.−)self-dismutation ~5.7. Therefore, the compounds cannot be functional SOD mimics, if they disproportionate O2.− with a log value of rate constant equal to or lower than 5.7.

We have estimated several values of pKa(ax). based on established relationships [25, 50, 68]. The lengthening of methyl chains (in MnTM-2 (or 3 or 4)-PyP5+) to ethyl chains (in MnTE-2(or 3 or 4)-PyP5+) has essentially no impact on log kcat(O2.−) and E1/2 vs NHE for MnIIIP/MnIIP, assuming therefore safely that it also has no significant impact on pKa(ax).

Table 2.

The initial rates of O2 evolution (vo, nM s−1), maximal amount of O2 produced (max µM O2), yield in O2 (expressed as %), turnover number (TON), and turnover frequency (TOF, s−1).

| N | Compound | vo (nM s−1) | Endpoint (max µM O2) | TON | O2 yield (%) | TOF (s−1, based on initial rate) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | MnTBAP3− | 126.1 | 249.75 | 12.49 | 49.95 | 0.0063 |

| 2 | MnTE-2-PyPhP5+ | 133.7 | 203.35 | 10.17 | 40.67 | 0.0067 |

| 3 | MnTE-3-PyP5+ | 700.1 | 132.72 | 6.64 | 26.54 | 0.0350 |

| 4 | MnTnHex-3-PyP5+ | 416.0 | 78.73 | 3.94 | 15.75 | 0.0208 |

| 5 | MnTnHex-4-PyP5+ | 556.3 | 116.49 | 5.82 | 23.30 | 0.0278 |

| 6 | MnTE-4-PyP5+ | 585.0 | 126.31 | 6.32 | 25.26 | 0.0293 |

| 7 | MnTnOct-3-PyP5+ | 563.4 | 111.06 | 5.55 | 22.21 | 0.0282 |

| 8 | MnTE-2-PyP5+ | 617.0 | 223.10 | 11.15 | 44.62 | 0.0309 |

| 9 | MnTPhE-2-PyP5+ | 307.4 | 124.52 | 6.23 | 24.90 | 0.0154 |

| 10 | MnTnBuOE-2-PyP5+ | 913.7 | 180.33 | 9.02 | 36.07 | 0.0457 |

| 11 | MnTnHexOE-2-PyP5+ | 400.5 | 159.72 | 7.99 | 31.94 | 0.0200 |

| 12 | MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ | 367.2 | 212.42 | 10.62 | 42.48 | 0.0184 |

| 13 | MnTnOct-2-PyP5+ | 289.9 | 197.55 | 9.88 | 39.51 | 0.0145 |

| 14 | MnTDE-2-ImP5+ | 291.8 | 250.85 | 12.54 | 50.17 | 0.0146 |

| 15 | M40403 | 29.2 | 19.51 | 0.98 | 3.90 | 0.0015 |

| 16 | Mn Salen, EUK-8 | 137.0 | 21.4 | 1.07 | 4.28 | 0.0068 |

| 17 | MnCl2 | 22.2 | 7.28 | 0.36 | 1.46 | 0.0011 |

Catalysis of H2O2 dismutation by Mn porphyrins

In our aqueous system, the catalysis of H2O2 dismutation by metal complex presumably occurred via MnIIIP/(O)2MnVP redox couple. The involvement of di-oxo species has been suggested for imidazolyl analog, MnTDE-2-ImP5+, whose chemistry is similar to that of MnP pyridyl analogs [63]. The dismutation involves 2-electron transfer as described by equations (3a) and (3b). (Note that axially ligated water molecules are indicated in equations (as they are involved in electron transfer) but are omitted throughout the text, Tables and Figures).

| (3a) |

| (3b) |

In vivo, the cellular reductants (ascorbate or simple thiols or tetrahidrobopterin or thiol-bearing proteins) would rapidly reduce FeIIIPs and MnIIIPs to their corresponding MIIPs [20, 21, 43, 64, 65]. In such scenario the dismutation would most likely involve the MnIIP/O=MnIVP redox couple as indicated in equations [4a] and [4b].

| (4a) |

| (4b) |

Further, a very likely in vivo scenario involving MnP and H2O2, given the low concentrations of H2O2 and high concentrations of cellular reductants, would be as follows: MnP gets oxidized with H2O2, acting as H2O2 reductase (eqs (3a) and (4a)) and the high-valent oxo complex gets reduced back with cellular reductants instead with H2O2 (eqs (3b) and (4b)) [21, 43, 44]. Such scenario was proposed for the peroxynitrite reductase activity of MnP; when coupled with cellular reductants the action of MnP upon ONOO− becomes catalytic [66–68]. Similar scenario has been also proposed for O2.− dismutation: instead of oxidizing and reducing O2.−, MnP would act as superoxide reductase closing a catalytic cycle with cellular reductants [19, 21].

The E1/2 values reported for O=MnIVP/MnIIIP as well as for (O)2MnVP/MnIIIP are essentially identical for different Mn and Fe porphyrins [66, 69–76]. For example the E1/2 values for the MnIIIP/MnIIP redox couple of MnTE-2-PyP5+, MnTE-3-PyP5+, MnTnBu-2-PyP5+, and MnTnBuOE-2-PyP5+ differ by as much as 223 mV (Table 1). Yet, the E1/2 values for their O=MnIVP/MnIIIP redox couple differ by 32 mV only and are +509, +529, and +509, and +541 mV vs SHE at pH 11, respectively (values vs NHE and vs SHE differ by ~5.7 mV) [77]. Further, E1/2 values for the O=MnIVP/MnIIIP redox couple of MnTM-2-PyP5+, MnTM-3-PyP5+ and MnTM-4-PyP5+ differ by 14 mV only and are +540, +526 and +532 mV vs NHE at pH 11, while E1/2 values for their MnIIIP/MnIIP redox couples differ by up to 168 mV (Table 1) [66]. Finally, E1/2 for (O)2MnVP/MnIIIP redox couple for MnTM-4-PyP5+, MnTM-2-PyP5+ and MnTDM-2-ImP5+ at pH 11 are all around +800 mV vs NHE, while the E1/2 for their MnIIIP/MnIIP redox couples differ by up to 286 mV (Table 1) [78]. The E1/2 for two-electron transfer (from Mn +2 to +4) involving MnIIP/O=MnIVP redox couple is somewhat different for each Mn porphyrin as it reflects the differences in E1/2 for their MnIIIP/MnIIP redox couples.

Impact of electron-density of the metal center of Mn porphyrins on the catalysis of H2O2 dismutation

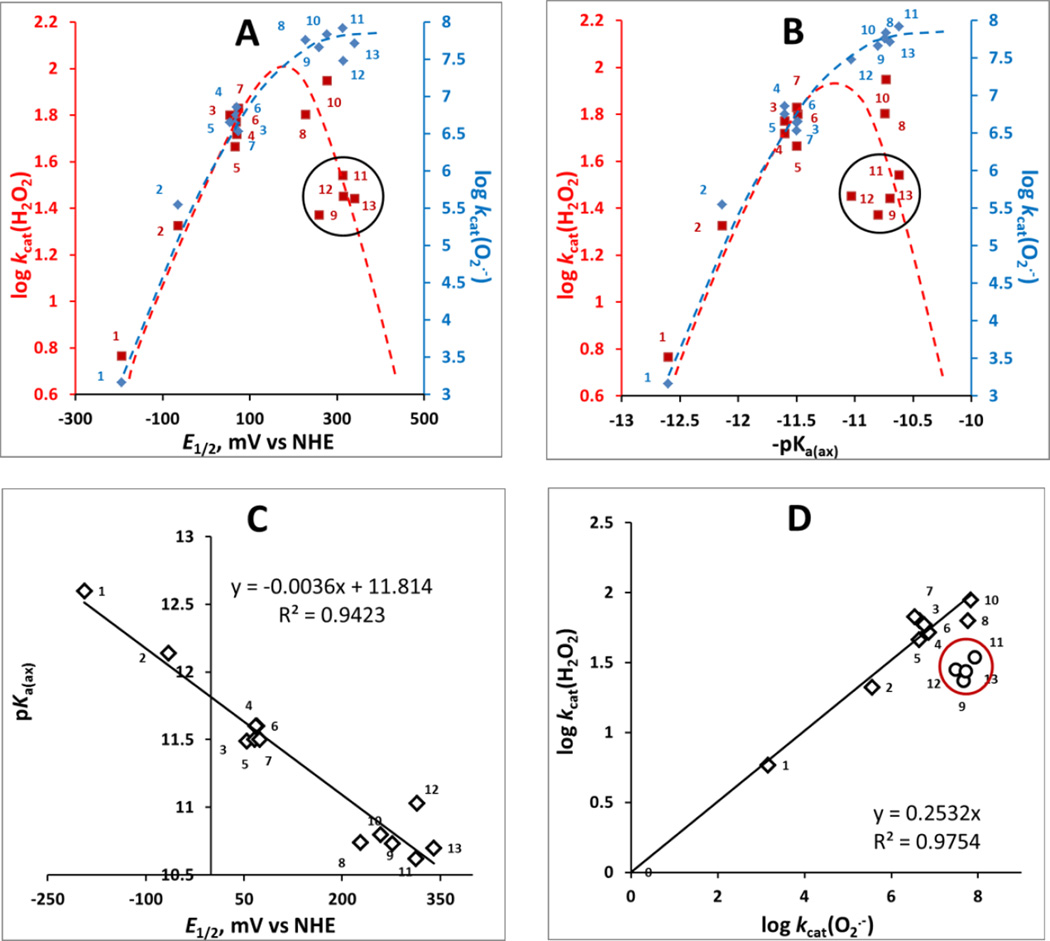

The H2O2 dismutation involves oxidation of MnIIIP to (O)2MnVP (eq 3a) and subsequent reduction of (O)2MnVP back to MnIIIP (eq 3b). Oxidation of MnIIIP to (O)2MnVP involves H2O2 binding to the metal site of metalloporphyrins in a 1st step; thus the reduction of H2O2 occurs via inner-sphere electron transfer. The two-electron transfer in a 2nd step of catalysis, resulting in (O)2MnVP (eq (3a)), appears to be similar for all MnPs due to nearly identical E1/2 values for (O)2MnVP/MnIIIP (see above under Catalysis of H2O2 dismutation by Mn porphyrins). The 1st step is dependent upon the electron density of the metal site; the more electron-deficient the metal site is, the higher its affinity for H2O2 binding. The electron-deficiency of the metal site is best described with proton-dissociation constant of the 1st axial water, pKa(ax), which refers to the following equilibrium: (H2O)2MnP5+ ↔ (HO)(H2O)MnP4+ + H+. With more electron-deficient Mn site, the axial binding of water oxygen is stronger. That results in weakening of the H—OH bond. Consequently, proton dissociates more readily from the axial water giving rise to (HO)(H2O)MnP4+. In turn, MnPs with more electron-deficient metal center, such as MnTE-2-PyP5+, have lower value of pKa(ax) than those with electron-rich Mn, such as MnTBAP3− (Table 1). The pKa(ax) was previously shown to relate linearly but inversely to E1/2 of MnIIIP/MnIIP redox couple; such relationship is here confirmed on new MnPs (Figure 4C) [50, 68]. Consequently, plots A and B in Figure 4 are essentially of identical shape. In other words, both pKa(ax) and E1/2 of MnIIIP/MnIIP redox couple describe the propensity of MnP to react with any species which involves its binding to the Mn site, such as ONOO−, H2O2 and ClO−. In summary, high electron-deficiency of Mn site supports: (i) low pKa(ax); (ii) high E1/2; (iii) high propensity of Mn to acquire electrons via axial binding of either water or any other species; and therefore (iv) high kcat(H2O2). Similar impact of electron-density of Mn site was demonstrated in the catalysis of O2.− dismutation [25]; in such case, though, the electron hopping (outer-sphere electron transfer), and not O2.− binding to the metal site, is predominantly involved in the catalysis of O2.− dismutation. However, higher electron-deficiency is necessary for Mn site to be reduced from +3 to + 2 in a 1st step of dismutation process. In turn, the higher the E1/2 of MnIIIP/MnIIP redox couple the higher is the log kcat(O2.−) (Figure 4A). Consequently, the catalase-like activity, log kcat(H2O2) parallels the SOD-like activity, log kcat(O2.−) (Figure 4C); in other words the more potent the SOD mimic is, the more able it is to catalyze H2O2 dismutation.

Figure 4. The relation between the log kcat(H2O2) and log kcat(O2.−) each with E1/2 of MnIIIP/MnIIIP redox couple in mV vs NHE (A) and with proton dissociation constant of axial water, pKa(ax) (B); the relation between the pKa(ax) and E1/2 for MnIIIP/MnIIP redox couple (C); and the relationship between the log kcat(H2O2) and log kcat(O2.−) (D).

The ability of MnP to catalyze H2O2 dismutation depends on H2O2 binding in a 1st step of dismutation process and thus on the electron-deficiency of the metal site which is described with pKa(ax) (B). The E1/2 for any couple that involves species in high-oxidation states (eqs [3] and [4]) are similar for all Mn porphyrins (see under Catalysis of H2O2 dismutation by Mn porphyrins); thus the 2nd step, electron transfer, has no impact on the magnitude of kcat(H2O2). In turn, the pKa(ax) was reported and confirmed here with new MnPs [49] to parallel the E1/2 of MnIIIP/MnIIP redox couple (C) [50, 68]. Consequently, the log kcat(H2O2) paralells the E1/2 of MnIIIP/MnIIP redox couple (A) though this couple is not involved in H2O2 dismutation. Since the E1/2 of MnIIIP/MnIIP redox couple controls the catalysis of O2.− dismutation also, the log kcat(H2O2) is proportional to log kcat(O2.−) (D). Please note that in plots A and B blue rhombs relate to O2.− dismutation while red squares relate to H2O2 dismuation. To help identify MnPs on plots please consult also Table 1. We have drawn dashed lines to indicate different trends in the catalysis of O2.− (blue) and H2O2 dismutations by MnPs (red). Please note that with a predominantly outer-sphere electron transfer in catalysis of O2.− dismutation (which involves electron hoping and not O2.− binding) we have a different behavior when compared to the catalysis of H2O2 dismutation by MnPs; the latter involves binding of H2O2 to the metal site (plots A and B). In such scenario, steric hindrance, imposed by longer alkyl chains with and without polar oxygen atoms within chains, plays significant role. Encircled are the MnPs with long and bulky ortho N-pyridyl substituents: MnTnOct-2-PyP5+, MnTnHex-2-PyP5+, MnTnHexOE-2-PyP5+, MnTPhE-2-PyP5+.

Those Mn porphyrins that bear sterically hindered moieties, such as long or bulky ortho N-pyridyl substituents (MnTnOct-2-PyP5+, MnTnHex-2-PyP5+, MnTnHexOE-2-PyP5+, MnTPhE-2-PyP5+ (encircled in Figure 4, plots A, B and D), while having similar E1/2 value for MnIIIP/MnIIP redox couple, have the kcat(H2O2) values 2–3-fold lower than that of MnTE-2-PyP5+. Sterics plays larger role with inner- (H2O2 dismutation) than with outer-sphere electron transfer (O2.−dismutation). Thus during H2O2 dismutation longer pyridyl substituents hinder the approach of H2O2 to the metal site. Besides sterics, the electronic factors contribute to the magnitude of kcat(H2O2) also. MnTnBuOE-2-PyP5+ has long butoxyethyl pyridyl substituents each of which contains one oxygen atom. The oxygen atoms are exposed to the immediate environment of porphyrin and facilitate the approach of H2O2 via hydrogen bonding (#10 red square in Figure 4). Same dramatic impact of hydrogen bonding was demonstrated on the metalation rate of H2TnBuOE-2-PyP4+ [47]. With MnTnHexOE-2-PyP5+, however, oxygen atoms are buried deeper into the hexoxyethyl chains resulting in lesser impact; in turn the log kcat(H2O2) is closer to the value for alkyl analogs, MnTnHex(or Oct)-2-PyP5+ [49]. The hindrance of the oxygen atoms from the solvent is also reflected in the lipophilicity of MnTnHexOE-2-PyP5+ which is closer to the one of the alkyl analog of same number of carbon atoms in pyridyl substituents, MnTnNon-2-PyP5+.

Impact of stability of Mn porphyrins towards H2O2 – driven oxidative degradation on the catalysis of H2O2 dismutation

The interplay between the kcat(H2O2) and the stability of MnPs towards degradation determines the yield of H2O2 dismutation – i.e. the yield in O2 evolution. The O2 yield describes best the quality of an catalyst. In addition to O2 yield (%), the maximal amount of O2 (µM) produced during catalysis, the turnover number (TON), and turn-over frequency (TOF, s−1) were determined (Table 2). The two-electron process during H2O2 dismutation involves the formation of species in high-oxidation states of Mn with high oxidizing power. Such species can either oxidize H2O2 closing the catalase-like cycle, or oxidize itself or another catalyst with its subsequent degradation [79]. Therefore the stability of Mn porphyrins towards oxidative degradation was assessed.

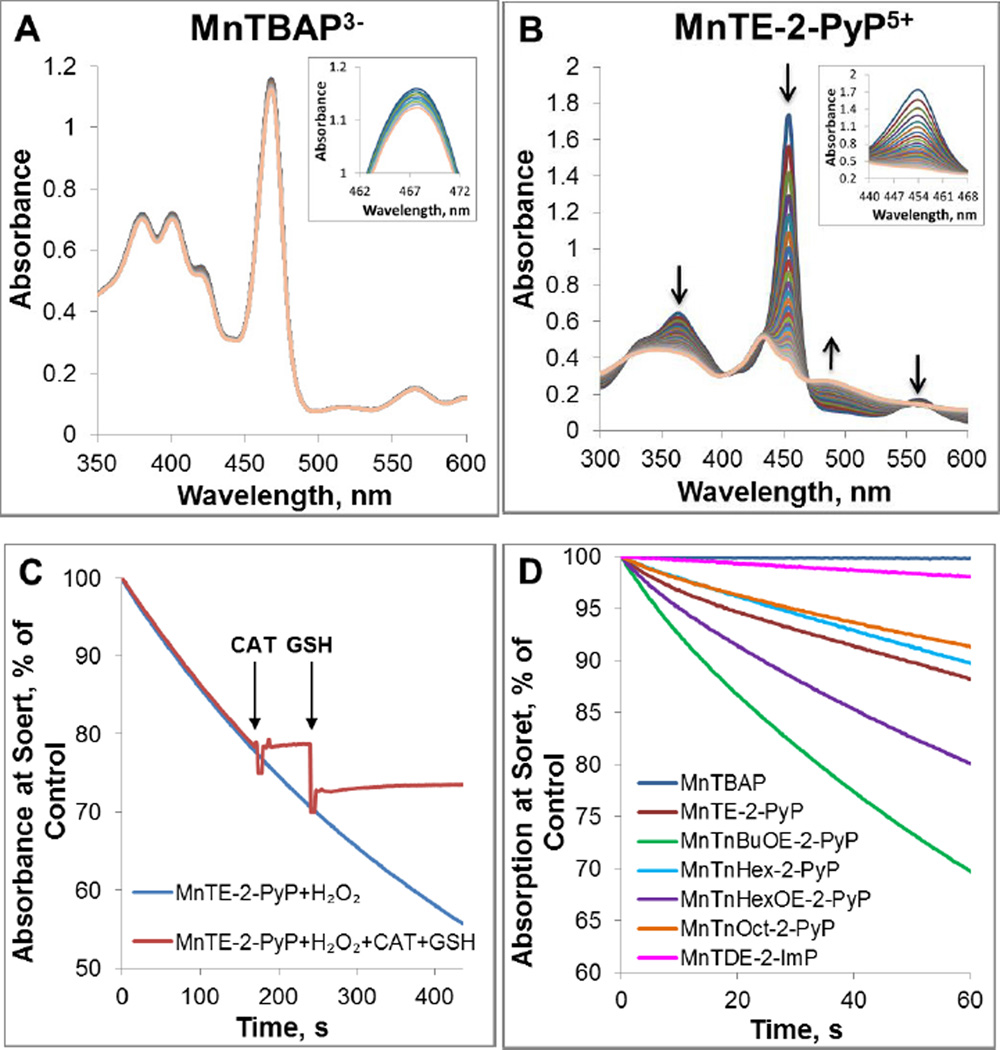

Stability of MnP towards oxidative degradation is influenced by: (i) the protonation equilibrium at inner pyrrolic nitrogens of the corresponding metal-free ligand, pKa3; and (ii) steric and electronic factors. The first two pyrrolic nitrogen protons of the metal-free porphyrin are very acidic and their dissociation constants are not accessible experimentally. The pKa3 of 3rd (basic) inner pyrrolic nitrogen proton (H3P+ <==> H2P + H+) has been determined for ortho, meta and para isomers of MnTMPyP5+ and MnTBAP3− (Table 1) [25]. Based on established relationships [19, 21, 25] the pKa3 of isomeric ethyl analogs, MnTEPyP5+, are presumably very similar. The higher the pKa3 is, the less prone the protons are to leave pyrrolic nitrogens. The affinity of pyrrolic nitrogens to protons reflects in turn their affinity to manganese in Mn complex: the higher the pKa3, the more stable is the metal complex. The pKa3 is inversely proportional to E1/2 of MnIIIP/MnIIP redox couple, i.e., the higher the E1/2 the less stable are the Mn porphyrins. MnTBAP3− with pKa3 of 5.5 is much more stable complex than MnTE-2-PyP5+ which has pKa3 of −0.9 [25]. Such stability towards the loss of Mn contributes also to the stability of MnPs towards oxidative degradation. This is also exemplified with Fe corrole; its high metal/ligand stability contributes to its stability as a catalyst of H2O2 dismutation (see below under Fe corrole). With pKa3 =5.5, the anionic electron-rich MnTBAP3− is a stable metal complex; during 30 min it does not undergo any degradation with H2O2 (Figure 5A and D). However, cationic, electron-deficient MnTE-2-PyP5+, with ~ 6 log units lower pKa3 = −0.9, undergoes much faster degradation (Figure 5B and D). When left in the presence of H2O2 for ~200 s, MnTE-2-PyP5+ was degraded to a point of no return; in turn the addition of GSH fails to restore it (Figure 5C) [66, 67].

Figure 5. Degradation of Mn porphyrins with H2O2.

Spectral changes were measured within first 30 minutes for Mn porphyrins MnTBAP3− (A) and MnTE-2-PyP5+ (B)). Time-dependent reduction in the absorbance at the Soret band for each MnP is shown in inset. (C) Time-dependent degradation of MnTE-2-PyP5+ with H2O2. The degradation of MnTE-2-PyP5+ was terminated with the addition of catalase. Subsequent addition of GSH did not cause any change in the absorbance indicating irreversible degradation of MnP to non-porphyrin species over the course of ~200 s of reaction. The drop in absorbance is due to a sample dilution. Experiments were carried out at (25±1)°C in 0.05 M tris buffer, pH 7.8 and 0.1 mM EDTA with 10 µM MnP and 0.5 mM H2O2. (D) The H2O2-driven degradation of several MnPs whose structures impose different steric and electronic effects upon H2O2 approach.

To address the impact of sterics and electronics, the H2O2-driven oxidative degradation of several other MnPs were explored and shown in Figure 5: two alkoxyalkyl derivatives, MnTnBuOE-2-PyP5+ (#10) and MnTnHexOE-2-PyP5+ (#11), and N,N’-diethylimidazolyl derivative, MnTDE-2-ImP5+ (#14) (Figure 5D). The steric and electronic factors of those MnPs are different from each other and from those of ortho Mn(III) N-alkylpyridylporphyrins. MnTnBuOE-2-PyP5+ and MnTnHexOE-2-PyP5+ have oxygen atoms in pyridyl substituents, while MnTDE-2-ImP5+ is di-ortho N,N’-diethylimidazolyl analog with alkyl chains placed vertically above and below the porphyrin plane.

All have similar values of thermodynamic parameters as ortho Mn(III) N-alkylpyridylporphyrins (such as E1/2 and pKa(ax)). They also have similar values for kcat(O2.−) as catalysis of O2.− dismutation has predominantly outer-sphere character and does not involve O2.− binding to the Mn site. Yet their structural differences greatly impact their ability to catalyze H2O2 dismutation which process involves H2O2 binding to the metal site. The higher stability of MnTDE-2-imP5+ towards H2O2, than that of ortho Mn(III) N-substituted pyridylporphyrins, is afforded by the protection of Mn site with alkyl chains placed both above and below the porphyrin plane (Figure 5D). In the case of alkoxyalkyl MnTnBuOE-2-PyP5+, oxygen atoms within N-substituents facilitate the catalysis of H2O2 dismutation via hydrogen bonding, but destabilize the complex towards oxidative degradation (Figures 5D). Another alkoxyalkyl analog, MnTnHexOE-2-PyP5+, is similarly lipophilic to MnP with identical number of carbon atoms in pyridyl substituents, MnTnNon-2-PyP5+. This indicates that oxygen atoms in MnTnHexOE-2-PyP5+ have less impact on molecule-solvent interactions than in MnTnBuOE-2-PyP5+ and thus are only marginally involved in facilitation of H2O2 dismutation. For that same reason MnTnHexOE-2-PyP5+ is more stable towards degradation (Figure 5D). In turn the kcat(H2O2) of MnTnHexOE-2-PyP5+ is 2.3-fold lower than MnTnBuOE-2-PyP5+ and similar to its alkyl analogs, MnTnHex(or Oct)-2-PyP5+ (Table 1). The interplay between their ability to catalyze H2O2 dismutation and their stability towards oxidative degradation gave rise to the similar O2 production yields of MnTnBuOE-2-PyP5+ (#10) and MnTnHexOE-2-PyP5+ (#11) (Table 2).

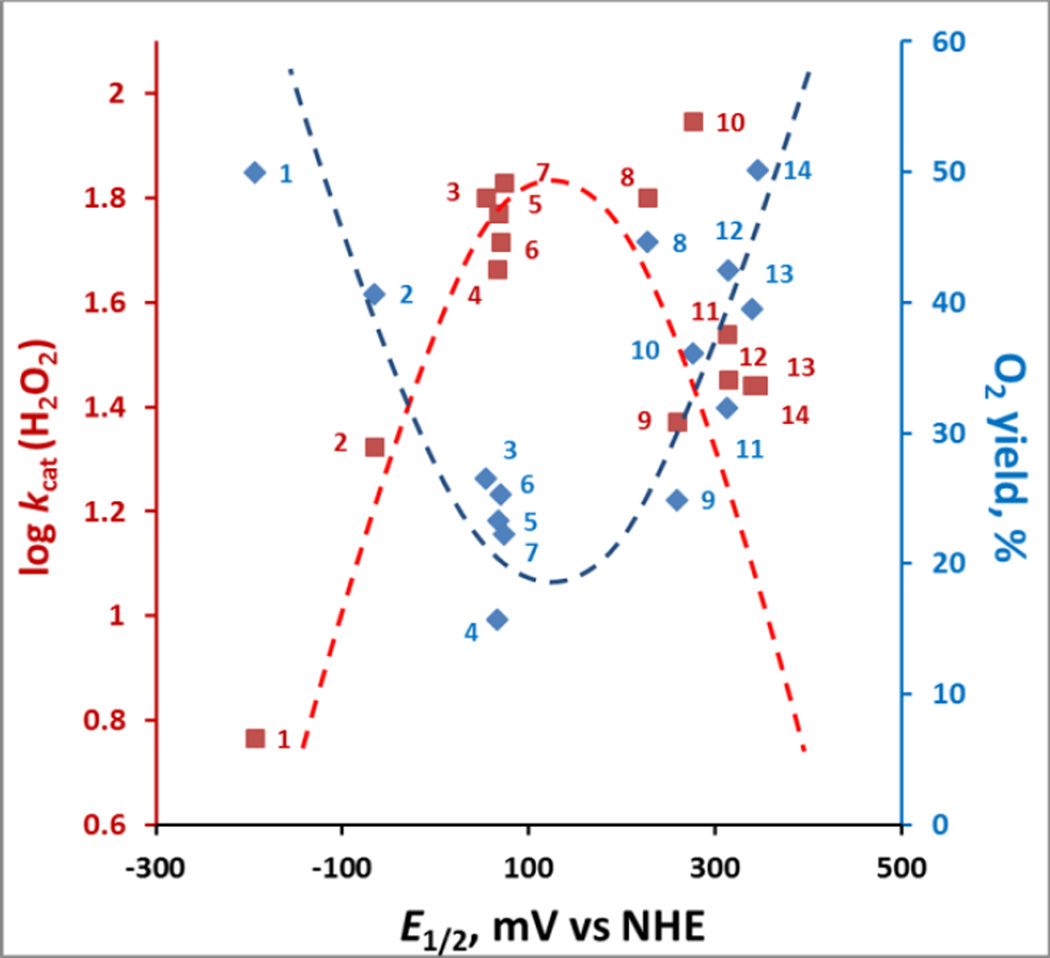

Correlation between the rate of H2O2 dismutation and its yield

The impact of steric and electronic effects as well as of the Mn site electron density on the catalysis of H2O2 dismutation are best demonstrated in Figure 6 where the O2 yield and the log kcat(H2O2) are correlated with E1/2 of MnIII/MnII redox couple. The bell-shaped relationships indicate that there is an interplay between the log kcat(H2O2) and stability of the compounds which controls the yield of H2O2 dismutation. Mn(III) N-alkylpyridylporphyrins, whose metal sites are electron- deficient (higher E1/2 and lower values of pKa(ax)) and favor H2O2 binding, such as MnTE-2-PyP5+(#8), are faster in catalyzing H2O2 dismutation than anionic electron-rich porphyrins such as MnTBAP3− (#1). While MnTBAP3− catalyzes H2O2 dismutation with a very low rate constant (due to vastly unfavorable E1/2), the higher metal/ligand stability allows it to resist oxidative degradation and thus be able to give rise to a yield even slightly higher than that of a less stable MnTE-2-PyP5+. Differences in electronic and steric factors of alkoxyalkyl derivatives MnTnHexOE-2-PyP5+ (#11) and MnTnBuOE-2-PyP5+ (#10) result in different log kcat(H2O2) and stabilities to oxidative degradation. Yet both afford similar O2 yield which is an ultimate measure of their catalytic potency. The increased stability of MnTDE-2-ImP5+ (#14) (see above) affords highest yield among cationic Mn porphyrins.

Figure 6. The relationships between the kinetic (log kcat(H2O2)) and thermodynamic parameter (E1/2 for MIII/MII redox couple) each with thermodynamic parameter, yield of O2.

While of similar E1/2, the presence of relatively approachable oxygen atoms in alkoxyalkyl chains in MnTnBuOE-2-PyP5+ (#10) relative to MnTnHexOE-2-PyP5+ (#11) resulted in 2.3-fold higher kcat(H2O2); yet, yields in O2 are identical, due to larger stability of latter compound (Figure 5). MnTDE-2-ImP5+ (#14), with identical kcat(H2O2) but higher stability than MnTnBuOE-2-PyP5+, has higher yield which is also the highest among cationic MnPs. The interplay between the ability of MnPs to catalyze H2O2 dismutation (red line) and their stability to oxidative degradation determines the yield of H2O2 dismutation and the efficacy of catalyst (blue line). Dashed lines are meant to indicate the trends.

H2O2 dismutation by other metal complexes

Mn(II) cyclic polyamines

Mn(II) cyclic polyamine M40403, a potent SOD mimic, has essentially no catalase-like activity (Table 3). When compared to metalloporphyrins, M40403 with Mn in its +2 oxidation state has sufficient electron density not to favor H2O2 binding; its kcat(H2O2) = 8.18 M−1 s−1. The same reasoning may apply to MnCl2 with Mn in +2 oxidation state. The metal/ligand stability of Mn(II) cyclic polyamine M40403 is only log K =13.6 [80], which would favor catalyst decomposition. Its turnover number is therefore extremely low, TON = 0.98 (Table 2). No differences in any of the parameters were found between SOD-active M40403 and SOD-inactive M40404 analog. The vastly stronger metal complex MnTBAP3−, with essentially identically low kcat(H2O2) = 5.84 M−1 s−1 has ~10-fold higher TON of 12.49, equal to the one of MnTE-2-PyP5+(TON = 11.15). The latter however is ~10-fold stronger catalase mimic kcat(H2O2) = 63.32 M−1 s−1, yet less stable metal complex (Tables 1, 2 and 3).

Mn salen, EUK-8

Mn salen complexes were claimed to be advantageous over Mn porphyrins due to their combined SOD- and catalase-like activities. The reported data show no catalase-like activity which was confirmed in this work on EUK-8 analog [41, 81].

Fe porphyrins

FePs are more sensitive to oxidative degradation with H2O2 than are MnPs. In turn, despite an order of magnitude higher kcat(H2O2), FePs are not superior catalysts to MnPs (Tables 2 and 3).

Fe corrole

Among Fe corroles, anionic disulfonato Fe corrole, FeTrF5Ph-β(SO3)2-corrole2− has the highest catalase-like activity, while cationic Mn corroles have no catalase-like activity [82]. When normalized to same conditions, Fe corrole has only a few fold-higher catalase-like activity than Fe porphyrins: log kcat(H2O2) for Fe corrole = 3.81 at 37 °C [53], while log kcat(H2O2) = 3.28 at 37°C for FeTE-2-PyP5+ [calculated using Arrhenius equation and log kcat(H2O2) = 2.90 at 25 °C]. Yet, FeTrF5Ph-β(SO3)2-corrole2− is 37-fold less potent SOD mimic. The reason for higher catalase-like activity is the tri-anionic nature of a corrole ligand which gives rise to much stronger metal/ligand interactions and in turn higher stability of Fe/corrole complex than that observed with Fe/porphyrin complex. The higher stability of Fe/corrole complex allows it to survive longer redox-cycling with H2O2 and in turn gives rise to larger turnover number. The oxidizing potential of high-valent Fe corrole and its cycling with cellular reductants has only vaguely been discussed in the literature but is likely playing a role in vitro and in vivo due to the high levels of endogenous reductants. Its excellent catalase-activity has been discussed as the “main superiority of FeTrF5Ph-β(SO3)2-corrole2− relative to other synthetic metal complexes”. Yet, a Mn(III) meso bis(N-methylpyridium-4-yl)-mono-pentafluorophenylcorrole, with no catalase-like activity, was superior to FeTrF5Ph-β(SO3)2-corrole2− in several in vitro and in vivo experiments [82].

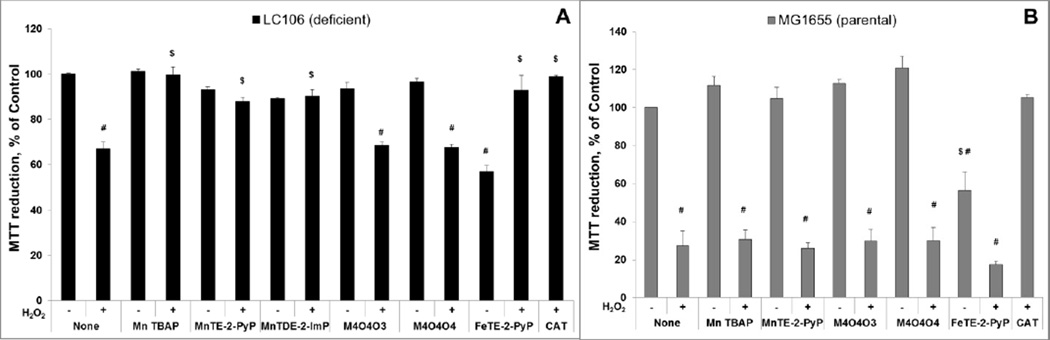

Evaluation of the redox-active drugs in an E. coli model of H2O2-induced damage

Hydrogen peroxide is unavoidable product of aerobic metabolism and organisms have developed efficient systems for its removal. Such systems and the mechanisms of their regulation are particularly well studied in E. coli. As in mammalian cells, the protection against H2O2 in E. coli is so efficient that peroxide concentration is normally kept below 10 nM [84, 85]. On such background it would be practically impossible to notice protection by compounds which display only a tiny fraction of the activity of natural enzymes. Therefore E. coli LC106 mutant, lacking both catalase and peroxidase activities [55], was used in our study along with its parental strain MG1655. Two different experimental scenarios were performed. In 1st scenario, we have added compounds simultaneously with H2O2 to E. coli culture so that they interact with each other in the medium. In 2nd scenario, E. coli culture was incubated with compounds for 1 hour, which allowed them to accumulate within E. coli. The culture was then exposed to H2O2.

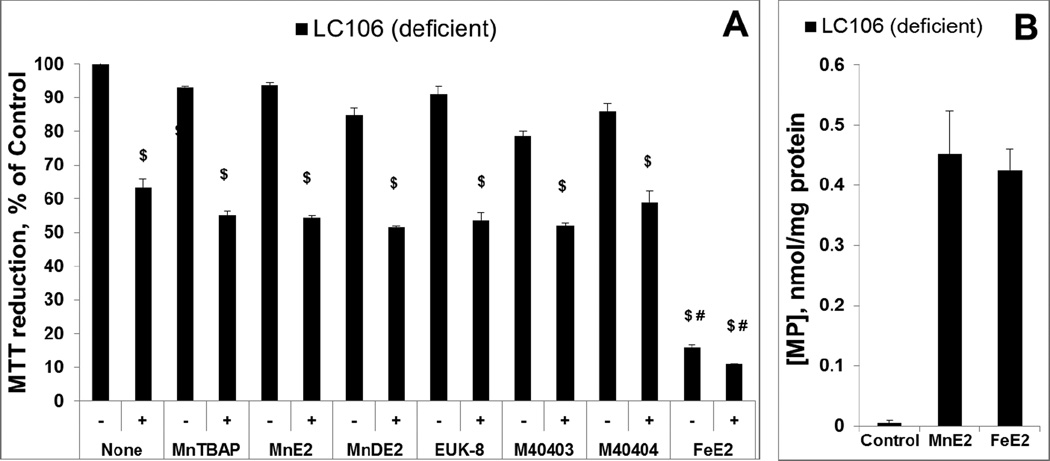

1. Under 1st experimental conditions 20 µM compounds were added in parallel with 0.5 mM H2O2 to the medium containing catalase/peroxidase-deficient LC106 strain (Figure 7A). Among tested Mn complexes, only MnTE-2-PyP5+, MnTDE-2-ImP5+ and MnTBAP3− were protective to catalase/peroxidase deficient LC106 strain (Figure 7). The higher stability of MnTBAP3− compensated for the lower kcat(H2O2) relative to MnTE-2-PyP5+ and MnTDE-2-ImP5+ (see Discussion and Tables 1–2). In turn, these MnPs were able to protect E. coli against H2O2 toxicity to a similar extent (Figure 7A). Mn(II) cyclic polyamines, M40403 and M40404 contain Mn in +2 oxidation state and are thus very unstable complexes [19, 43]. In turn, they undergo fast degradation with H2O2 affording low yield of H2O2 dismutation (Table 2). Consequently no protection of E. coli against exogenous H2O2 was demonstrated with M40403 and M40404 (Figure 7A). FeTE-2-PyP5+ was protective to a similar extent as MnTE-2-PyP5+, MnTDE-2-ImP5+ and MnTBAP3−. While FeTE-2-PyP5+ has a higher kcat(H2O2), it undergoes much faster oxidative degradation, releasing “free” Fe which is schematically depicted in Figure 9. The accumulation of “free” Fe within cell (its transport from the medium into the cell) is tightly controlled by E. coli and is in turn precluded to any dangerous level [50]. In turn under such conditions FeTE-2-PyP5+ was beneficial: in mutual interactions both FeTE-2-PyP5+ and H2O2 were removed from the culture which prevented significant cellular accumulation of FeTE-2-PyP5+ to toxic levels as seen in 2nd experiment (for details on the impact of Fe porphyrin on the growth of E. coli see [50]) (Figure 8 and Figure 9). Data are in agreement with the lack of toxicity of extracellular Fe reported by others [86, 87]. As anticipated, Mn salen (EUK-8) and tempol showed no effect in such scenario (data not shown). EUK-8 has low kcat(H2O2) and low yield (Table 1 and 2), while no catalase-like activity (no kcat(H2O2)) was demonstrated with Tempol (Table 3). None of the tested compounds protected the parental strain MG1655 against 10-fold higher 5 mM H2O2 (Figure 7B). When compared to mutant LC106, 10-fold higher concentration of H2O2 (5 mM H2O2) is required to cause comparable viability loss in the parental strain MG1655 under same experimental conditions. The low catalase-like activity and low stability of the compounds precludes dismutation of 5 mM H2O2 to significant extent (Figure 7B).

Figure 7. Evaluation of redox-active drugs in an E. coli model of H2O2-induced damage - drugs were added to E coli–containing medium in parallel with H2O2.

20 µM compounds were exposed to H2O2 for 15 min. The parental (MG1655) strain (A) and catalase/peroxidase-deficient mutant (LC106) (B) were studied; with parental MG1655 5 mM H2O2, and with catalase/peroxidase LC106 0.5 mM H2O2 was used. The viability was measured via MTT test and expressed as a percentage of the MTT reduction by non-treated cells. At 5 mM H2O2, no compound was efficacious in protecting parental strain. At 0.5 mM H2O2, the Mn complexes that are relatively stable, or have modest kcat(H2O2), that results in relatively high O2 production yield, were able to dismute and remove H2O2, protecting cell against it. Such interaction, in the case of Fe porphyrin, eliminated both the toxicity of FeP and H2O2. Student t-test was used to determine the statistical significance. Mean ± S.E is presented. # statistical significance (p<0.05) compared to untreated cells; $ statistical significance (p<0.05) compared to cells treated with H2O2 only.

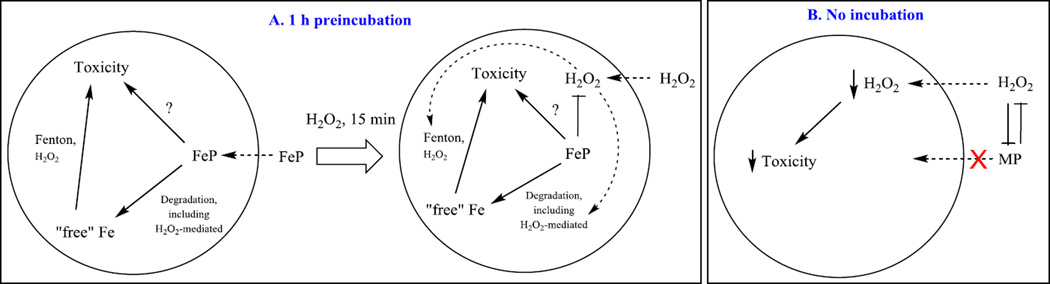

Figure 9. Proposed mechanism of FeP/H2O2 interactions impacting E. coli survival.

In plot (A), FeP was added to E.coli-containing medium for 1 hour prior to 15 min-exposure of culture to H2O2. At 15 min, all H2O2 was removed by the addition of catalase. In plot (B), FeP was added in parallel with H2O2. Under such conditions cycling of FeP with H2O2 releases ”free” Fe from the porphyrin ring, whose uptake is tightly controlled by E.coli; in turn FeP toxicity, seen when cells were preincubated with FeP (Figure 8), was avoided (Figure 7). In pre-incubation scenario (A), the toxicity of FeP may arise from: (i) Fenton chemistry of either “free” Fe released from Fe porphyrin or of Fe site of FeIIP4+; (ii) high-valent oxo FeP species of high oxidizing power; and (iii) direct interaction of FeP with specific cellular proteins/targets. In scenario where FeP catalyst and H2O2 were added simultaneously (plot B), their mutual interaction dismuted (removed) H2O2 only when 0.5 mM H2O2 (LC106) was applied to the cells but not 5 mM (MG1655). Their interaction also degrades FeP and in turn cells do not accumulate it within cell, where, otherwise, it might have caused toxicity as shown in (A). The accumulation of “free” Fe is tightly controlled by cell to avoid Fenton-based toxicity. MP – metalloporphyrin, either MnP or FeP.

Figure 8. Evaluation of metal complexes in an E. coli model (catalase/peroxidase-deficient LC106 strain) of H2O2-induced damage – drugs were pre-incubated with E. coli prior to H2O2 addition.

Except Mn salen, EUK-8, all other Mn complexes studied are the same as those in Figure 7. Two new abbreviations are introduced, MnE2 being MnTE-2-PyP5+ and MnDE2 being MnTDE-2-ImP5+. After 1 hour pre-incubation of E. coli with 20 µM of the drugs, the catalase/peroxidase mutant (LC106) cells were washed with PBS and exposed to 0.5 mM H2O2. After 15 min of incubation, H2O2 was decomposed by adding 1,000 units/ml of catalase (A). The viability was measured via MTT test and expressed as a percentage of the MTT reduction by non-treated cells. None of the compounds were toxic, but were also not able to suppress H2O2 toxicity. Fe porphyrin, FeTE-2-PyP5+, was toxic under given conditions. To verify the presence of pentacationic porphyrins in cells, the accumulation of MnTE-2-PyP5+ vs FeTE-2-PyP5+ during 1 hour of incubation was determined and appeared similar (plot B). Student t-test was used to determine the statistical significance. Mean ± S.E is presented. $statistical significance (p<0.05) compared to untreated cells; # statistical significance (p<0.05) compared to cells treated with H2O2 only.

2. Catalase/peroxidase-deficient E.coli strain was incubated with metal complexes for 1 hour, which allows them to accumulate within the cell and act intracellularly (Figure 8) [57]. We have reported that cationic Mn(III) N-substituted Mn and Fe pyridylporphyrins have different chemistry and in turn different biology. Neither MnTE-2-PyP5+ nor FeTE-2-PyP5+ at 20 µM concentration protected E.coli (catalase/peroxidase-deficient strain) against 0.5 mM H2O2 (Figure 8A) when pre-incubated for 1 hour prior addition of H2O2. As with 1st experiment, addition of catalase to the medium, prior to the addition of H2O2, completely prevented the H2O2-induced loss of viability (data not shown). The same conclusion is valid for other Mn complexes.

Relative to the 1st study, the lack of effect is presumably due to the low kcat(H2O2) and low intracellular levels of compounds and H2O2. Therefore, neither MnTE-2-PyP5+ nor FeTE-2-PyP5+ no any other metal complex studied can be considered catalase mimic under biologically relevant conditions. None of the Mn compounds, including MnTE-2-PyP5+, were toxic in contrast to FeTE-2-PyP5+ which exerted toxicity to both strains (Figure 8A, data not shown for MG1655); the data are in agreement with our earlier observations [50].

To provide evidence that the efficacy in protecting cell against H2O2 toxicity is due to the ability of pentacationic porphyrins to cross E.coli membrane, we have measured the accumulation of MnTE-2-PyP5+ and FeTE-2-PyP5+ in catalase/peroxidase deficient LC106 strain (Figure 8B). The data obtained on LC106 strain are in agreement with our earlier observations on the accumulation of Mn porphyrins in cell wall and cytosol of SOD-deficient JI132strain and wild type AB1157 E.coli strains [50, 57]. The accumulation of Mn porphyrins increases with their lipophilicity, which is in turn controlled by the length of N-alkylpyridyl chains [57, 88, 89]. Accumulation of Mn porphyrins in yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae [90], and in mammalian cells [91] was reported also. Importantly, several Mn porphyrins were found to accumulate in mouse heart and brain mitochondria [20, 92–94]. Efficacy studies, where different Mn porphyrins mimicked MnSOD, support their mitochondrial localization [21, 43].

Fe porphyrin accumulates in E. coli to a similar level as MnTE-2-PyP5+, supposedly via heme uptake mechanism. The toxicity of FeP is not yet fully explored. Based on aqueous chemistry and in vitro studies [19, 21, 25, 50] various factors may contribute to the toxicity of FePs, such as: (i) Fenton chemistry of either “free” Fe released from Fe porphyrin or of Fe site of FeIIP4+; (ii) high-valent oxo FeP species of high oxidizing power; and (iii) direct interaction of FeP with specific cellular proteins/targets (Figure 9).

Our results provide substantial evidence that even the most efficient SOD mimics (like MnTE-2-PyP5+ and M40403) do not have sufficient catalase-like activity in order to protect organisms from H2O2 under biological nano- and submicromolar levels of H2O2 in catalase-like fashion.

Conclusions

Mn- and Fe(III) porphyrins possess at most 0.0004% and 0.05% of the activity of catalase, while the values are orders of magnitude lower for other redox-active compounds often studied in various oxidative stress in vitro and in vivo models. In vivo efficacy in suppressing H2O2-mediated loss of viability has been evaluated in wild type and catalase/peroxidase-deficient E. coli strains. When the compounds were allowed to accumulate within the cell to act there as catalase mimics, the protection against extracellular H2O2 was not observed. Protection against H2O2 has only been demonstrated when E. coli was incubated simultaneously with high medium concentrations of FeP/MnP and H2O2. Under such conditions the interaction of FeP/MnP with H2O2 happens (dismutation with subsequent degradation), resulting in a release of “free” Mn/Fe. Since the uptake of “free” Fe is tightly controlled by E. coli, we did not observe any toxicity that might have been otherwise seen with intracellular “free” Fe.

Removal of H2O2 with Mn and Fe porphyrins in a catalase-like fashion, given low kcat(H2O2), and low intracellular H2O2 concentrations, seems not to be biologically relevant.

Emerging data point out to the involvement of H2O2 in the oxidation of thiols catalyzed by Mn porphyrins whereby signaling proteins are inhibited; in other words rather than simply removing H2O2, during its reduction, Mn porphyrins use it for therapeutic advantage affecting favorably cellular transcription [23, 24, 43, 44, 95]. Such scenario predicts that MnP mechanism of action is most likely of peroxidase-or thiol-oxidase- rather than catalase-type [21, 43, 65]. Studies are in progress to gain further insight into H2O2-related mechanism(s) of action(s) of Mn porphyrins.

Highlights.

-

-

Catalase-like activity of different classes of redox active compounds, described by kcat(H2O2) and yield of O2 evolution, was assessed

-

-

Mn(III) and Fe(III) porphyrins have catalase-like activity in the range of 0.0004% to 0.05% of the enzyme activity, respectively

-

-

Mn salen EUK-8 has 0.00135% of enzyme activity, while M40403, M40404 and Tempol have no detectable catalase-like activity

-

-

Low catalase-like activities of compounds studied must be taken into account when drawing conclusions on their mechanism(s) of action(s) in vitro an in vivo

Acknowledgement

Authors acknowledge financial help from NIH U19AI067798 and IBH General Research Funds (AT, IBH). IBH is a consultant with BioMimetix Pharmaceutical, Inc. and hold equities in BioMimetix Pharmaceutical Inc. JSR, CGCM and RSS acknowledge CAPES and CNPq Research Councils. RG acknowledges the financial support from State Committee of Science in Armenia (SCS 13-1D053) and ANSEF Biotech-3204. LB acknowledges support by grants MB02/12 and SRUL02/13 from Kuwait University, and the technical assistance of Milini Thomas. D. L. and I. I.–B. gratefully acknowledge the support by the intramural grant from University Erlangen-Nuremberg (Emerging Initiative: Medicinal Redox Inorganic Chemistry). Dr. Ines Batinic-Haberle and Dr. Tovmasyan are grateful for the support from NIH 1R03-NS082704-01.The authors are grateful to Dr. J. Imlay (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL) and Dr. D. Touati (Institute Jacques Monod, CNRS, Paris, France) for providing the strains used in this study.

Abbreviations

- O2•−

superoxide

- ONOO−

peroxynitrite

- ClO−

hypochlorite

- MnTE-2-PyP5+

Mn(III) meso-tetrakis(N-ethylpyridinium-2-yl)porphyrin (also known as AEOL10113)

- MnTE-3(or 4)-PyP5+

Mn(III) meso-tetrakis(N-ethylpyridinium-3(or 4)-yl)porphyrin

- MnTnHex-2(3 or 4)-PyP5+

Mn(III) meso-tetrakis(N-n-hexylpyridinium-2(3 or 4)-yl)porphyrin

- MnTnOct-2(or 3)-PyP5+

Mn(III) meso-tetrakis(N-n-octylpyridinium-2(or 3)-yl)porphyrin

- MnTPhE-2-PyP5+

Mn(III) meso-tetrakis (N-(2’-phenylethyl)pyridinium-2-yl)porphyrin

- MnTnHexOE-2-PyP5+

Mn(III) meso-tetrakis(N-(2’-n-hexoxyethyl)pyridinium-2-yl)porphyrin

- MnTE-2-PyPhP5+

Mn(III) meso-tetrakis(phenyl-4’-(N-ethylpyridinium-2-yl))porphyrin

- MnTnBuOE-2-PyP5+

Mn(III) meso-tetrakis(N-(n-butoxyethyl)pyridinium-2-yl)porphyrin

- MnTDE-2-ImP5+

Mn(III) meso-tetrakis[N,N’-diethylimidazolium-2-yl)porphyrin, AEOL10150

- MnIIITBAP3−

Mn(III) meso-tetrakis(4-carboxyphenyl)porphyrin (also abbreviated as MnTBAP)

- FeTE-2-PyP5+

Fe(III) meso-tetrakis(N-ethylpyridinium-2-yl)porphyrin

- FeTnOct-2-PyP5+

Fe(III) meso-tetrakis(N-n-octylpyridinium-2-yl)porphyrin

- FeTrF5Ph-β(SO3)2-corrole2−

Fe(III) meso-tris(pentafluorophenyl)-β-bis(sulfonato)corrole

- EUK-8

Mn(III) salen

- tempol

4-OH-2,2,6,6,-tetramethylpiperidine-1-oxyl

- NXY-059

2,4-disulfophenyl-N-tert-butylnitrone (also known as OKN -007)

- E1/2

half-wave reduction potential

- SOD

superoxide dismutase

- NHE

normal hydrogen electrode

- TON

turnover number

- TOF

turnover frequency; charges and axial ligands of MnPs and FePs are omitted in text and some Figures for simplicity

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Sies H. Role of metabolic H2O2 generation: redox signaling and oxidative stress. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:8735–8741. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R113.544635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forman HJ, Maiorino M, Ursini F. Signaling functions of reactive oxygen species. Biochemistry. 2010;49:835–842. doi: 10.1021/bi9020378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang B, Wang Y, Su Y. Peroxiredoxins, a novel target in cancer radiotherapy. Cancer Lett. 2009;286:154–160. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holley AK, Miao L, St Clair DK, St Clair WH. Redox-modulated phenomena and radiation therapy: the central role of superoxide dismutases. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;20:1567–1589. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.5000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Armogida M, Nistico R, Mercuri NB. Therapeutic potential of targeting hydrogen peroxide metabolism in the treatment of brain ischaemia. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;166:1211–1224. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.01912.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gao MC, Jia XD, Wu QF, Cheng Y, Chen FR, Zhang J. Silencing Prx1 and/or Prx5 sensitizes human esophageal cancer cells to ionizing radiation and increases apoptosis via intracellular ROS accumulation. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2011;32:528–536. doi: 10.1038/aps.2010.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kwei KA, Finch JS, Thompson EJ, Bowden GT. Transcriptional repression of catalase in mouse skin tumor progression. Neoplasia. 2004;6:440–448. doi: 10.1593/neo.04127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miriyala S, Spasojevic I, Tovmasyan A, Salvemini D, Vujaskovic Z, St Clair D, Batinic-Haberle I. Manganese superoxide dismutase, MnSOD and its mimics. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1822:794–814. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nonn L, Berggren M, Powis G. Increased expression of mitochondrial peroxiredoxin-3 (thioredoxin peroxidase-2) protects cancer cells against hypoxia and drug-induced hydrogen peroxidedependent apoptosis. Mol Cancer Res. 2003;1:682–689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sampson N, Koziel R, Zenzmaier C, Bubendorf L, Plas E, Jansen-Durr P, Berger P. ROS signaling by NOX4 drives fibroblast-to-myofibroblast differentiation in the diseased prostatic stroma. Mol Endocrinol. 2011;25:503–515. doi: 10.1210/me.2010-0340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shen KK, Ji LL, Chen Y, Yu QM, Wang ZT. Influence of glutathione levels and activity of glutathione-related enzymes in the brains of tumor-bearing mice. Biosci Trends. 2011;5:30–37. doi: 10.5582/bst.2011.v5.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sorokina LV, Solyanik GI, Pyatchanina TV. The evaluation of prooxidant and antioxidant state of two variants of lewis lung carcinoma: a comparative study. Exp Oncol. 2010;32:249–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Castello PR, Drechsel DA, Day BJ, Patel M. Inhibition of mitochondrial hydrogen peroxide production by lipophilic metalloporphyrins. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;324:970–976. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.132134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hempel N, Carrico PM, Melendez JA. Manganese superoxide dismutase (Sod2) and redoxcontrol of signaling events that drive metastasis. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2011;11:191–201. doi: 10.2174/187152011795255911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buettner GR, Wagner BA, Rodgers VG. Quantitative redox biology: an approach to understand the role of reactive species in defining the cellular redox environment. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2013;67:477–483. doi: 10.1007/s12013-011-9320-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Batinic Haberle I, Tovmasyan A, Spasojevic I. The complex mechanistic aspects of redoxactive compounds, commonly regarded as SOD mimics. BioInorg React Mech. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Batinic-Haberle I, Rajic Z, Tovmasyan A, Reboucas JS, Ye X, Leong KW, Dewhirst MW, Vujaskovic Z, Benov L, Spasojevic I. Diverse functions of cationic Mn(III) N-substituted pyridylporphyrins, recognized as SOD mimics. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;51:1035–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.04.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Batinic-Haberle I, Reboucas JS, Benov L, Spasojevic I. Chemistry, biology and medical effects of water soluble metalloporphyrins. In: Kadish KM, Smith KM, Guillard R, editors. Handbook of Porphyrin Science. Singapore: World Scientific; 2011. pp. 291–393. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Batinic-Haberle I, Reboucas JS, Spasojevic I. Superoxide dismutase mimics: chemistry, pharmacology, and therapeutic potential. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;13:877–918. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Batinic-Haberle I, Spasojevic I, Tse HM, Tovmasyan A, Rajic Z, St Clair DK, Vujaskovic Z, Dewhirst MW, Piganelli JD. Design of Mn porphyrins for treating oxidative stress injuries and their redox-based regulation of cellular transcriptional activities. Amino Acids. 2012;42:95–113. doi: 10.1007/s00726-010-0603-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Batinic-Haberle I, Tovmasyan A, Roberts ER, Vujaskovic Z, Leong KW, Spasojevic I. SOD Therapeutics: Latest Insights into Their Structure-Activity Relationships and Impact on the Cellular Redox-Based Signaling Pathways. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;20:2372–2415. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.5147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tovmasyan A, Sheng H, Weitner T, Arulpragasam A, Lu M, Warner DS, Vujaskovic Z, Spasojevic I, Batinic-Haberle I. Design, mechanism of action, bioavailability and therapeutic effects of mn porphyrin-based redox modulators. Med Princ Pract. 2013;22:103–130. doi: 10.1159/000341715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jaramillo MC, Briehl MM, Crapo JD, Batinic-Haberle I, Tome ME. Manganese porphyrin, MnTE-2-PyP5+, Acts as a pro-oxidant to potentiate glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis in lymphoma cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;52:1272–1284. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jaramillo MC, Briehl MM, Batinic Haberle I, Tome ME. Inhibition of the Electron Transport Chain Via the Pro-Oxidative Activity of Manganese Porphyrin-Based SOD Mimetics Modulates Bioenergetics and Enhances the Response to Chemotherapy. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2013;65:S25. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Batinić-Haberle I, Spasojević I, Hambright P, Benov L, Crumbliss AL, Fridovich I. Relationship among Redox Potentials, Proton Dissociation Constants of Pyrrolic Nitrogens, and in Vivo and in Vitro Superoxide Dismutating Activities of Manganese(III) and Iron(III) Water-Soluble Porphyrins. Inorg Chem. 1999;38:4011–4022. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Day BJ, Batinic-Haberle I, Crapo JD. Metalloporphyrins are potent inhibitors of lipid peroxidation. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;26:730–736. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(98)00261-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kachadourian R, Johnson CA, Min E, Spasojevic I, Day BJ. Flavin-dependent antioxidant properties of a new series of meso-N,N'-dialkyl-imidazolium substituted manganese(III) porphyrins. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;67:77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2003.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muscoli C, Cuzzocrea S, Ndengele MM, Mollace V, Porreca F, Fabrizi F, Esposito E, Masini E, Matuschak GM, Salvemini D. Therapeutic manipulation of peroxynitrite attenuates the development of opiate-induced antinociceptive tolerance in mice. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3530–3539. doi: 10.1172/JCI32420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Doctrow SR, Huffman K, Marcus CB, Tocco G, Malfroy E, Adinolfi CA, Kruk H, Baker K, Lazarowych N, Mascarenhas J, Malfroy B. Salen-manganese complexes as catalytic scavengers of hydrogen peroxide and cytoprotective agents: structure-activity relationship studies. J Med Chem. 2002;45:4549–4558. doi: 10.1021/jm020207y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Day BJ. Catalase and glutathione peroxidase mimics. Biochem Pharmacol. 2009;77:285–296. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gauuan PJ, Trova MP, Gregor-Boros L, Bocckino SB, Crapo JD, Day BJ. Superoxide dismutase mimetics: synthesis and structure-activity relationship study of MnTBAP analogues. Bioorg Med Chem. 2002;10:3013–3021. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(02)00153-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trova MP, Gauuan PJ, Pechulis AD, Bubb SM, Bocckino SB, Crapo JD, Day BJ. Superoxide dismutase mimetics. Part 2: synthesis and structure-activity relationship of glyoxylate- and glyoxamide-derived metalloporphyrins. Bioorg Med Chem. 2003;11:2695–2707. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(03)00272-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Day BJ, Fridovich I, Crapo JD. Manganic porphyrins possess catalase activity and protect endothelial cells against hydrogen peroxide-mediated injury. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1997;347:256–262. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1997.0341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reboucas JS, Spasojevic I, Batinic-Haberle I. Pure manganese(III) 5,10,15,20-tetrakis(4- benzoic acid)porphyrin (MnTBAP) is not a superoxide dismutase mimic in aqueous systems: a case of structure-activity relationship as a watchdog mechanism in experimental therapeutics and biology. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2008;13:289–302. doi: 10.1007/s00775-007-0324-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Noritake Y, Umezawa N, Kato N, Higuchi T. Manganese salen complexes with acid-base catalytic auxiliary: functional mimetics of catalase. Inorg Chem. 2013;52:3653–3662. doi: 10.1021/ic302101c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kubota R, Asayama S, Kawakami H. A bioinspired polymer-bound Mn-porphyrin as an artificial active center of catalase. Chem Commun (Camb) 2014;50:15909–15912. doi: 10.1039/c4cc06286h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kash JC, Xiao Y, Davis AS, Walters KA, Chertow DS, Easterbrook JD, Dunfee RL, Sandouk A, Jagger BW, Schwartzman LM, Kuestner RE, Wehr NB, Huffman K, Rosenthal RA, Ozinsky A, Levine RL, Doctrow SR, Taubenberger JK. Treatment with the reactive oxygen species scavenger EUK-207 reduces lung damage and increases survival during 1918 influenza virus infection in mice. Free Radic Biol Med. 2014;67:235–247. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Agrawal S, Dixit A, Singh A, Tripathi P, Singh D, Patel DK, Singh MP. Cyclosporine A and MnTMPyP Alleviate alpha-Synuclein Expression and Aggregation in Cypermethrin-Induced Parkinsonism. Mol Neurobiol. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s12035-014-8954-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dixit A, Srivastava G, Verma D, Mishra M, Singh PK, Prakash O, Singh MP. Minocycline, levodopa and MnTMPyP induced changes in the mitochondrial proteome profile of MPTP and maneb and paraquat mice models of Parkinson's disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1832:1227–1240. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kubota R, Imamura S, Shimizu T, Asayama S, Kawakami H. Synthesis of water-soluble dinuclear mn-porphyrin with multiple antioxidative activities. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2014;5:639–643. doi: 10.1021/ml400493f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sharpe MA, Ollosson R, Stewart VC, Clark JB. Oxidation of nitric oxide by oxomanganesesalen complexes: a new mechanism for cellular protection by superoxide dismutase/catalase mimetics. Biochemical J. 2002;366:97–107. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Batinic-Haberle I, Spasojevic I. Complex chemistry and biology of redox-active compounds, commonly known as SOD mimics, affect their therapeutic effects. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;20:2323–2325. doi: 10.1089/ars.2014.5921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Batinic-Haberle I, Tovmasyan A, Spasojevic I. An educational overview of the chemistry, biochemistry and therapeutic aspects of Mn porphyrins - From superoxide dismutation to HO-driven pathways. Redox Biol. 2015;5:43–65. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2015.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tovmasyan A, Weitner T, Jaramillo M, Wedmann R, Roberts E, Leong KW, Filipovic M, Ivanovic-Burmazovic I, Benov L, Tome M, Batinic-Haberle I. We have come a long way with Mn porphyrins: from superoxide dismutation to H2O2-driven pathways. Free Rad Biol Med. 2013;65:S133. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Batinić-Haberle I, Spasojević I, Stevens RD, Hambright P, Fridovich I. Manganese(III) meso-tetrakis(ortho-N-alkylpyridyl)porphyrins. Synthesis, characterization, and catalysis of O2/·- dismutation. Journal of the Chemical Society, Dalton Transactions. 2002:2689–2696. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Batinic-Haberle I, Spasojevic I, Stevens RD, Hambright P, Neta P, Okado-Matsumoto A, Fridovich I. New class of potent catalysts of O2.-dismutation. Mn(III) ortho-methoxyethylpyridyl- and di-ortho-methoxyethylimidazolylporphyrins. Dalton Trans. 2004:1696–1702. doi: 10.1039/b400818a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rajic Z, Tovmasyan A, Spasojevic I, Sheng H, Lu M, Li AM, Gralla EB, Warner DS, Benov L, Batinic-Haberle I. A new SOD mimic, Mn(III) ortho N-butoxyethylpyridylporphyrin, combines superb potency and lipophilicity with low toxicity. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;52:1828–1834. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Spasojevic I, Batinic-Haberle I, Stevens RD, Hambright P, Thorpe AN, Grodkowski J, Neta P, Fridovich I. Manganese(III) biliverdin IX dimethyl ester: a powerful catalytic scavenger of superoxide employing the Mn(III)/Mn(IV) redox couple. Inorg Chem. 2001;40:726–739. doi: 10.1021/ic0004986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tovmasyan A, Carballal S, Ghazaryan R, Melikyan L, Weitner T, Maia CG, Reboucas JS, Radi R, Spasojevic I, Benov L, Batinic-Haberle I. Rational Design of Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) Mimics: The Evaluation of the Therapeutic Potential of New Cationic Mn Porphyrins with Linear and Cyclic Substituents. Inorg Chem. 2014;53:11467–11483. doi: 10.1021/ic501329p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tovmasyan A, Weitner T, Sheng H, Lu M, Rajic Z, Warner DS, Spasojevic I, Reboucas JS, Benov L, Batinic-Haberle I. Differential Coordination Demands in Fe versus Mn Water-Soluble Cationic Metalloporphyrins Translate into Remarkably Different Aqueous Redox Chemistry and Biology. Inorg Chem. 2013;52:5677–5691. doi: 10.1021/ic3012519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Aston K, Rath N, Naik A, Slomczynska U, Schall OF, Riley DP. Computer-aided design (CAD) of Mn(II) complexes: superoxide dismutase mimetics with catalytic activity exceeding the native enzyme. Inorg Chem. 2001;40:1779–1789. doi: 10.1021/ic000958v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Haber A, Aviram M, Gross Z. Variables that influence cellular uptake and cytotoxic/cytoprotective effects of macrocyclic iron complexes. Inorg Chem. 2012;51:28–30. doi: 10.1021/ic202204u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mahammed A, Gross Z. Highly efficient catalase activity of metallocorroles. Chem Commun (Camb) 2010;46:7040–7042. doi: 10.1039/c0cc01989e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Benson BB, Krause D., Jr The Concentration and Isotopic Fractionation of Gases Dissolved in Freshwater in Equilibrium with the Atmosphere. 1. Oxygen. Limnology and Oceanography. 1980;25:662–671. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu Y, Bauer SC, Imlay JA. The YaaA protein of the Escherichia coli OxyR regulon lessens hydrogen peroxide toxicity by diminishing the amount of intracellular unincorporated iron. Journal of Bacteriology. 2011;193:2186–2196. doi: 10.1128/JB.00001-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thomas M, Craik J, Tovmasyan A, Batinic-Haberle I, Benov L. Amphiphilic cationic Zn-porphyrins with high photodynamic antimicrobial activity. Future Microbiology. 2014 doi: 10.2217/fmb.14.148. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kos I, Benov L, Spasojevic I, Reboucas JS, Batinic-Haberle I. High lipophilicity of meta Mn(III) N-alkylpyridylporphyrin-based superoxide dismutase mimics compensates for their lower antioxidant potency and makes them as effective as ortho analogues in protecting superoxide dismutase-deficient Escherichia coli. J Med Chem. 2009;52:7868–7872. doi: 10.1021/jm900576g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Celic T, Spanjol J, Bobinac M, Tovmasyan A, Vukelic I, Reboucas JS, Batinic-Haberle I, Bobinac D. Mn porphyrin-based SOD mimic, MnTnHex-2-PyP and non-SOD mimic, MnTBAP suppressed rat spinal cord ischemia/reperfusion injury via NF-kappaB pathways. Free Radic Res. 2014:1–35. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2014.960865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Batinic-Haberle I, Cuzzocrea S, Reboucas JS, Ferrer-Sueta G, Mazzon E, Di Paola R, Radi R, Spasojevic I, Benov L, Salvemini D. Pure MnTBAP selectively scavenges peroxynitrite over superoxide: comparison of pure and commercial MnTBAP samples to MnTE-2-PyP in two models of oxidative stress injury, an SOD-specific Escherichia coli model and carrageenan-induced pleurisy. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;46:192–201. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.09.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]