Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to identify the supportive care needs and unmet needs of women with breast cancer (BC) in rural Scotland.

Methods

In 2013, a survey of supportive care needs of rural women with BC was conducted using the short-form Supportive Care Needs Survey (SCNS-SF34). Semi-structured interviews were subsequently conducted with a purpose sample of questionnaire respondents.

Results

Forty-four women with BC completed the survey and ten were interviewed. Over half of participants reported at least one moderate to high unmet need (56.8 %, n = 25), a tenth reported low needs (11.4 %, n = 5), and around a third reported no unmet needs for all 34 items (31.8 %, n = 14). The most prevalent moderate to high needs were ‘being informed about cancer in remission’ (31.8 %, n = 14), ‘fears about the cancer spreading’ (27.3 %, n = 12), ‘being adequately informed about the benefits and side-effects of treatment’ and ‘concerns about the worries of those close to you’ (both 25.0 %, n = 11). Interviews highlighted the following unmet needs: information about treatment and side effects, overview of care, fear of recurrence, impact on family and distance from support.

Conclusions

Rural women with BC report similar unmet needs to their urban counterparts. Fear of recurrence is a key unmet need that should be addressed for all women with BC. However, they also report unique unmet needs because of rural location. Thus, it is critical that cancer services address the additional unmet needs of rural women with BC and, in particular, needs relating to distance from services.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00520-014-2501-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Rural, Breast cancer, Supportive care needs, Unmet needs

Introduction

Female breast cancer (BC) is one of the most common cancers occurring worldwide [1]. For the age group 55 to 64 years old, 5-year relative survival rate for female BC is over 80 % in high-income countries including the UK [2]. A significant proportion of women with BC experience physical and emotional difficulties within the first year following diagnosis and treatment and years later [3, 4].

‘Unmet needs’ refers to the gap between a person’s experience of services and the actual services required or desired [5]. A substantial proportion of women with BC perceive significant unmet needs throughout the cancer trajectory, with information and psychological needs being the most prevalent [6]. Evidence suggests that the primary concern is ‘fear of the cancer returning’ [6].

There are unmet need differences between rural and urban women with BC that likely have implications for supportive cancer care [7, 8]. In particular, the need to travel long distances or stay away from home for treatment causes disruption to family life and work and invokes a sense of isolation and displacement [7, 8]. Rural women with BC have less access to mental health services and cancer support groups compared to urban women with BC and experience less favourable personal attitudes and social norms regarding mental health resource use as a function of living in smaller rural communities [9].

Rural Scotland accounts for 94 % of the landmass, and around a fifth of the Scottish population (1 million) live in rural areas [10]. The rural population is growing at a faster rate than the rest of Scotland [10]; hence, it is important the supportive care needs of people living in rural areas are known. The aim of this study was to identify the supportive care needs and unmet needs of women with BC in rural Scotland.

Materials and methods

Design

In 2013, a mixed method study involving a survey of supportive care needs and semi-structured telephone interviews of rural women with BC was conducted. Two members of Breast Cancer Care’s Service User Research Partnership (SURP) who had personal and direct experience of BC were co-researchers. The academic co-researchers provided training so that the service user co-researchers were able to conduct interviews and analyse data. A personal account of their experience as service user co-researchers is provided in a supplementary file.

Inclusion criteria

Study participants met the following criteria:

Living in a rural area of Scotland (as defined by residential postcode)

Diagnosed and living with breast cancer

Could communicate in English

Sampling and recruitment strategy

A Scotland rural area is defined as a settlement with a population of less than 3000 [11]. A purposive sample of women with BC living in rural areas was obtained from Breast Cancer Care’s electronic database. This identified 180 eligible individuals. Breast Cancer Care posted letters of invitation to participate in the study and a self-completion questionnaire (with appended consent form) to all eligible individuals. Women who completed the questionnaire and were ≤5 years of diagnosis were approached to participate in a telephone interview because this group reported higher unmet needs when compared to those >5 years since diagnosis. Thus, an attempt was made to interview all 21 of the eligible women (i.e. ≤5 years from date of BC diagnosis).

Data collection

The short-form Supportive Care Needs Survey (SCNS-SF34) was used to assess unmet needs [12]. It was chosen because it has been validated [13] and currently there is no instrument that has been developed to specifically measure rural dimensions of unmet need in cancer survivors.

Interviews by telephone were conducted to explore unmet needs in more depth. Telephone interviews increase access to geographically dispersed participants [14–16]. The interview schedule (Box 1) was designed to cover those unmet needs that were highlighted in the survey. This approach would yield a more in-depth understanding of supportive care needs from the perspective of women with BC in rural areas.

Box 1: Interview schedule

| Emotional needs: For example, fear of the cancer spreading, feeling sad and anxious or depressed or worried about the people close to them |

| Care process: For example, being treated like a person and not just a number as they went through their diagnosis and treatment |

| Information: For example, about the treatment and the benefits and side effects of the treatment and about recurrence |

| Talking to others: For example, talking to other patients affected by breast cancer |

Data analysis

Sociodemographic data and SCNS-SF34 items were analysed descriptively and reported as mean and standard deviation (SD) and n (%), as appropriate. For each SCNS-SF34 item and domain, the proportion of individuals who reported ‘no need’, ‘low need’ and ‘moderate or high need’ was calculated [13]. Chi-square (χ 2) tests were conducted to examine the association between ‘moderate to high need’ and time since cancer diagnosis (i.e. ≤5 vs. >5 years). Audio-recorded telephone interviews were transcribed verbatim and analysed thematically using the framework approach [17].

A small number of anonymised quotations are included to illustrate unmet need under each theme.

Results

Sample characteristics

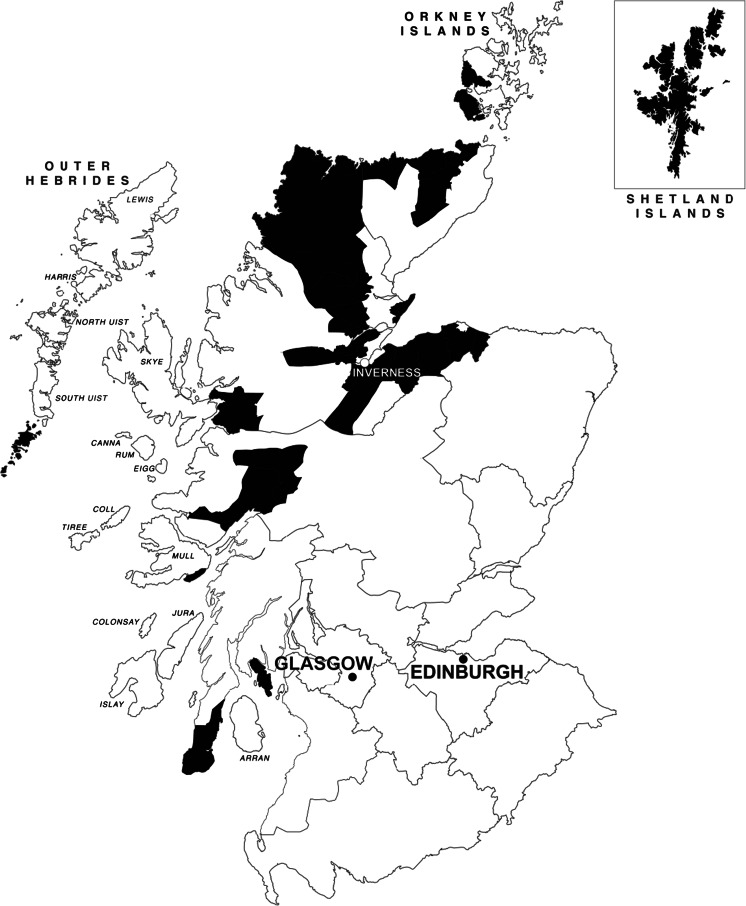

A quarter of women invited to participate in the study returned the questionnaire (44 out of a potential 180). The geographic distribution of returned questionnaires is shown in Fig. 1. Sample characteristics are reported in Table 1. Twenty-one eligible women (i.e. ≤5 years from date of BC diagnosis) were contacted by telephone to invite them to be interviewed. Ten women were interviewed.

Fig. 1.

Geographic distribution of questionnaire responses

Table 1.

Sample sociodemographic and clinical characteristics

| Percentage (n) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 100 (44) | |

| Postcode area (description) | ||

| IV | Inverness-shire, Ross-shire, Sutherland, Island of Skye | 54.5 (24) |

| PA | Argyll and Bute, Islands of Mull, Iona, Tiree, Coll | 13.6 (6) |

| K | Caithness and Orkney Islands | 11.4 (5) |

| PH | South-Western Highlands, including Islands of Eigg, Rum and Canna | 9.1 (4) |

| ZE | Shetland Islands | 6.8 (3) |

| HS | Outer Hebrides | 4.5 (2) |

| Age (mean [SD]) | ||

| At survey | 59.1 [10.0] | |

| At diagnosis | 52.2 [9.5] | |

| Relationship status | ||

| Married/civil partnership and living with husband/wife/partner | 75.0 (33) | |

| Separated or divorced | 13.6 (6) | |

| Single | 6.8 (3) | |

| Widowed/partner died | 4.5 (2) | |

| Employment status | ||

| Paid employment or self-employed | 43.2 (19) | |

| Retired from paid work | 36.4 (16) | |

| In full-time education/employment training | 6.8 (3) | |

| Permanently unable to work because of long-term sickness or disability | 6.8 (3) | |

| Looking after home or family | 4.5 (2) | |

| Doing something else | 2.3 (1) | |

| Currently receiving medical treatment for breast cancer | ||

| Yes | 43.2 (19) | |

| No | 56.8 (25) | |

| Currently receiving medical treatment not related to breast cancer | ||

| Yes | 54.5 (24) | |

| No | 45.5 (20) | |

| Time since diagnosis | ||

| ≤18 months | 11.4 (5) | |

| 18 months to 5 years | 36.4 (16) | |

| >5 years | 52.3 (23) | |

| Breast cancer treatment (at any time) | ||

| Surgery | 100 (44) | |

| Chemotherapy | 63.6 (28) | |

| Radiotherapy | 52.3 (23) | |

| Hormone therapy | 72.7 (32) | |

| Biological therapy | 13.6 (6) | |

| Complementary therapy | 6.8 (3) | |

| Breast cancer treatment (at time of survey) | ||

| Surgery | 0 (0) | |

| Chemotherapy | 2.3 (1) | |

| Radiotherapy | 2.3 (1) | |

| Hormone therapy | 43.2 (19) | |

| Biological therapy | 0 (0) | |

| Complementary therapy | 2.3 (1) | |

Supportive Care Needs Survey results

SCNS-SF34 results are reported in Table 2. Over half of participants reported at least one moderate to high unmet need (56.8 %, n = 25), a tenth reported low needs (11.4 %, n = 5), and around a third reported no unmet needs for all 34 items (31.8 %, n = 14). The most prevalent moderate to high need was ‘being informed about cancer in remission’ (31.8 %, n = 14), ‘fears about the cancer spreading’ (27.3 %, n = 12), ‘being adequately informed about the benefits and side-effects of treatment’ and ‘concerns about the worries of those close to you’ (both 25.0 %, n = 11).

Table 2.

SCNS-SF34 items

| Rank | Item | Moderate/high need, % (n) | Domain |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Being informed about cancer which is under control or diminishing (i.e. remission) | 31.8 (14) | Health system and information |

| 2 | Fears about the cancer spreading | 27.3 (12) | Psychological |

| 3 | Being adequately informed about the benefits and side effects of treatments before you choose to have them | 25.0 (11) | Health system and information |

| 3 | Concerns about the worries of those close to you | 25.0 (11) | Psychological |

| 5 | Having access to professional counselling (e.g. psychologist, social worker, counsellor, nurse specialist) if you, family or friends need it | 22.7 (10) | Health system and information |

| 5 | Not being able to do the things you used to do | 22.7 (10) | Physical and daily living |

| 7 | Being given written information about the important aspects of your care | 20.5 (9) | Health system and information |

| 7 | Being treated like a person and not just another case | 20.5 (9) | Health system and information |

| 7 | Having one member of hospital staff with whom you can talk to about all aspects of your condition, treatment and follow-up | 20.5 (9) | Health system and information |

| 10 | Uncertainty about the future | 20.5 (9) | Psychological |

| 10 | Keeping a positive outlook | 20.5 (9) | Psychological |

| 12 | Being given information (written, diagrams, drawings) about aspects of managing your illness and side effects at home | 18.2 (8) | Health system and information |

| 12 | Being informed about your test results as soon as feasible | 18.2 (8) | Health system and information |

| 12 | Pain | 18.2 (8) | Physical and daily living |

| 15 | Being informed about things you can do to help yourself to get well | 15.9 (7) | Health system and information |

| 15 | Worry that the results of treatment are beyond your control | 15.9 (7) | Psychological |

| 15 | Work around the home | 15.9 (7) | Physical and daily living |

| 18 | Being given explanations of those tests for which you would like explanations | 13.6 (6) | Health system and information |

| 18 | Feelings about death and dying | 13.6 (6) | Psychological |

| 18 | Learning to feel in control of your situation | 13.6 (6) | Psychological |

| 18 | Anxiety | 13.6 (6) | Psychological |

| 18 | Reassurance by medical staff that the way you feel is normal | 13.6 (6) | Patient care and support |

| 18 | Hospital staff attending promptly to your physical needs | 13.6 (6) | Patient care and support |

| 18 | Hospital staff acknowledging, and showing sensitivity to, your feelings and emotional needs | 13.6 (6) | Patient care and support |

| 25 | Feelings of sadness | 11.4 (5) | Psychological |

| 26 | Being treated in a hospital or clinic that is as physically pleasant as possible | 9.1 (4) | Health system and information |

| 26 | Feeling down or depressed | 9.1 (4) | Psychological |

| 26 | More choice about which cancer specialists you see | 9.1 (4) | Patient care and support |

| 26 | Lack of energy/tiredness | 9.1 (4) | Physical and daily living |

| 26 | Changes in sexual feelings | 9.1 (4) | Sexuality |

| 26 | Changes in your sexual relationships | 9.1 (4) | Sexuality |

| 32 | Feeling unwell a lot of the time | 6.8 (3) | Physical and daily living |

| 32 | More choice about which hospital you attend | 6.8 (3) | Patient care and support |

| 34 | To be given information about sexual relationships | 4.5 (2) | Sexuality |

Eleven moderate to high needs were reported by more than 20 % of participants; six were from the ‘health system and information’ domain, four were from the ‘psychological’ domain, and one was from the ‘physical and daily living’ domain (Table 2).

Health systems and information and psychological needs were the most frequently reported domains of unmet needs, followed by physical and daily living, patient care and support, and sexuality. With the exception of the physical and daily living domain, women ≤5 years reported greater unmet need than those >5 years from diagnosis, and statistically significantly higher needs were observed for the health systems and information domain among women ≤5 years from diagnosis compared to those >5 years since cancer diagnosis (66.7 vs. 21.7 %; Pearson’s χ 2 = 9.03, p = 0.003) (Table 3).

Table 3.

SCNS-SF34 Domains

| Moderate to high need, % (n) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time since diagnosis | ||||

| Domain | Total | ≤5 years | >5 years | Significancea |

| Health systems and information | 43.2 (19) | 66.7 (14) | 21.7 (5) | 0.003 |

| Psychological | 43.2 (19) | 57.1 (12) | 30.4 (7) | 0.074 |

| Physical and daily living | 29.5 (13) | 28.6 (6) | 30.4 (7) | 0.892 |

| Patient care and support | 25.0 (11) | 28.6 (6) | 21.7 (5) | 0.601 |

| Sexuality‡ | 9.1 (4) | 9.5 (2) | 8.7 (2) | 0.924 |

aPearson’s chi-square test (χ 2) except where marked (‡) when Fisher’s exact test reported due to violation of χ 2 assumptions. Statistically significant differences at p < 0.05 are in italics

Interview findings

Initial coding of the data was closely mapped to the areas that were directly addressed during the semi-structured telephone interview (see Box 1). By re-reading and analysing quotations within the first list of themes and re-categorising key quotations, a final set of five key unmet needs was produced (see Box 2). Most of these needs are applicable to women with BC living in urban areas [6], but this study explores these needs from the perspective of women in rural areas.

Box 2: Unmet needs

| Information about treatment and side effects |

| Overview of care |

| Fears about cancer |

| Impact on family |

| Distance from support |

Information

The Supportive Care Needs (SCN) survey found that a quarter of participants had unmet needs relating to ‘being adequately informed about the benefits and side-effects of treatment’ (25.0 %, n = 11). Interviews highlighted that lack of information made it difficult for these patients to manage treatment side effects. Participants reported lack of information about chemotherapy, radiotherapy, breast reconstruction, hormone therapy and type of surgery. One participant said:

You’re just thrown in there… it’s just like nobody prepares you… it should be written down; what the side effects are, what they are for, what its actually for, none of that information was actually given.

Another participant also reported lack of information about side effects of medication (in her case tamoxifen). She reported limited support in managing side effects, although she eventually received some good advice from her GP, which was to switch the time of day she took tamoxifen. She said:

With the chemotherapy and radiotherapy I felt I hadn’t been given enough information or support when I started taking the Tamoxifen”… {I was} told to persevere with the Tamoxifen for 6 months… {I had} dreadful hot flushes and sweating… {My GP} said, “Oh well you know you have to take it”.

Overview of care

Participants described the difficulties that they encountered when making appointments for treatments or consultations. Several participants reported having to chase appointments and being drip-fed information rather than being given a total overview of their care. One participant said:

What would have been very helpful would have been if there was one point of contact…I felt as though they were drip-feeding me information… {I was} having to chase… appointments… sometimes I had to phone 4 different people… If they gave you some timelines for treatment and they explained it to you.

Another participant described the delays that she faced while waiting to find out about chemotherapy appointments. After waiting 4 weeks for a letter regarding chemotherapy, she phoned up to complain. She also described the difficulties she faced during treatment. She said:

It’s a bit of a production line going in for chemo… waiting for your drugs to arrive, the drugs didn’t arrive but nobody actually comes to tell you what’s going on, you’re sitting there for 2 or 3 h waiting on…I was starting to get annoyed because some of my friends had come and, and gone out and had all theirs…I just want it over with cause I know that it’s going to make me feel so rubbish.

However, other participants could not fault the way that their care was provided. One participant, for instance, felt that communication and information had met her needs and spoke highly of the support she received, especially from the breast care nurses at the hospital.

Fear of recurrence

The SCN survey found that the most prevalent moderate to high needs were ‘being informed about cancer in remission’ (31.8 %, n = 14) and ‘fears about the cancer spreading’ (27.3 %, n = 12). Participants described a process of having to trust their body again so that they did not always think that it was cancerous. A participant said that she knew that if she, ‘worried about everything every day she would not be able to live her life’. Nevertheless, she did worry ‘if it’s coming back’. She said, ‘the hardest part is… not knowing if it’s there, I remember sort of thinking, how can you have cancer and not know it’s there’.

Another participant did not think that the health care she received provided, ‘you with enough support’ to manage the anxiety associated with the on-going fear of the cancer re-occurring. Another participant, however, reported receiving good support from the Maggie’s Centre (a cancer information and support centre) but said that, ‘they might think I was dwelling on things too much’ if she kept going back. Nevertheless, fear of recurrence was a persistent issue for her since she said, ‘I’d like to say that 1 day I didn’t wake up and think of cancer but it hasn’t happened yet’. Thus, in spite of receiving support, it clearly had not prevented her from having an on-going fear of recurrence. Similarly, another participant reported that she continues to worry about recurrence. She said, ‘And I do worry, I still very much worry about a recurrence, about it coming back’.

Impact on family

In the SCN survey, a quarter of participants identified as a need ‘concerns about the worries of those close to you’ (both 25.0 %, n = 11). A participant referred to the impact of cancer on her marriage, which she felt powerless to change. She said:

{there were} massive difficulties for my husband and myself. It changed the relationship and it was very difficult. I carried on for a long time. I tried to protect everyone but I felt powerless. It had an effect on me.

A couple of participants were concerned about the impact that their cancer had or might have on their children. One participant said that she was, ‘so concerned about my daughter really’. (P02). She spoke about a higher chance of cancer recurrence, which her daughter ‘bore [it] in mind without dwelling on it too much’. Another participant said: ‘My main concern, I was concerned what would happen to my child if anything happened to me’.

In contrast, another participant spoke about the help that she received during treatment to support her family. She reports how grateful she was for the efforts made by the breast care nurse at the hospital who went to great lengths to ensure that, throughout her chemotherapy, she was not away from her children overnight. This required partnership arrangements between the local health centre who ensured that her bloods were taken at 8:00 am so that she was in the surgery when there were no other people and less risk of infection and the airline company who ensured that her blood tests got to the hospital on the first flight on Monday morning so that she could be informed by 4 o-clock that day whether she should take the Tuesday morning flight for her chemotherapy. She said:

They arranged like to be done in 1 day—like all those appointments at the hospitals…. so I wasn’t there for weeks trying to get appointments… {name of nurse}, the Breast Care Nurse at the Western didn’t want me away from home for months because of the kids so she tried to fit everything in so that I would go up 1 day, get seen by all the {three} hospitals stay overnight and home the next day.

Distance from support

The SCN survey did not directly address supportive care needs arising from a patient being away from home for treatment or living some distance away from support services and support groups. Nevertheless, during the telephone interviews, participants raised support issues arising from travel distance such as travel costs, being away from home and therefore away from support and access difficulties to support. One participant described some of the difficulties that she encountered during treatment due to living on a remote island. She said:

We have no mobile phone signal and it costs £60 in a taxi to get the ferry. And then if it’s cancelled because of the weather… The logistics are bad. If you have radiotherapy you have to live on the mainland and you are away from all of your support.

She was unable to attend appointments in the city where the hospital was located without an overnight stay and therefore requested to continue her treatment at another hospital in another city because she could stay with family. Her access to psychological support involved an overnight stay. Hence, after her initial appointments, she continued speaking with the therapist on a fortnightly basis by telephone.

Several participants commented that they were unable to access support groups due to the distance that they would have to travel to attend a group. One participant reported how she was signposted to a support group that was 80 miles away from her home and met in the evening. Another participant felt that there were no opportunities for her to meet with women her own age. Although she attended a support group, most women who met were much older than her.

Discussion

Implications for services

This is the first study to identify supportive care needs of women with BC living in rural areas of Scotland. The SCN survey found that over half of women reported at least one moderate to high unmet need. The most prevalent moderate to high needs were about ‘being informed about cancer in remission’, ‘fears about the cancer spreading’, ‘being adequately informed about the benefits and side-effects of treatment’ and ‘concerns about the worries of those close to you’. The findings therefore echo those found in other studies about the supportive care needs of women with BC [6]. Fear of recurrence is a critical unmet need among women with BC in rural and urban areas and should be a cancer care service priority. When the study findings are compared with literature about urban women with BC [6, 18, 19], it is clear that unmet needs are not specific to rural women but apply to women with BC irrespective or where they happen to live. The study therefore lends support to those rejecting the dominant deficit discourse of rurality, which is that rural health experience is different and deficient and rural dwellers are inevitably disadvantaged [20].

The semi-structured qualitative interviews provided more depth about unmet needs and highlighted that some women with BC living in rural areas lacked information about treatment and side effects, faced difficulties making appointments and obtaining results, did not feel adequately supported to address fear of recurrence, were concerned about the impact of cancer on their family, and faced difficulties due to travel distance from treatment centres. Again, many of these needs are also evident among women with BC in urban areas [6]. For instance, our study found that women in rural areas were worried about cancer recurrence and concerned about the impact of cancer on family members, which are also issues of concern for urban women with BC [18, 19]. A failure to coordinate a patient’s care and provide an overview of care from diagnosis to long-term follow-up is clearly distressing for women with breast cancer. Several of the women who participated in the study advised that they would like to have had more support coordinating their care, particularly as navigating the breast cancer pathway is not straightforward and can involve dealing with different medical staff.

However, our study suggests that there are supportive care needs that are particularly acute for women living in rural areas and which are exacerbated as a consequence of geographical location. Our study confirms other research that has reported the need to travel long distances or stay away from home for treatment is a unique supportive care need for rural women with BC [7–9]. In this respect, the deficit model of rurality applies [20]. Women living in rural areas identified supportive care needs specific to their remote geographical location that may present particular challenges for health care providers. First, due to greater travel distances, rural women with BC may need to draw on the support of generalist local health care providers rather than breast cancer specialists to address their needs. Telehealth offers potential for these rural generalists to receive support, gain working knowledge of specialty conditions (such as BC) and deliver high-quality services for their rural patients [21]. Indeed, eHealth/telemedicine is identified as an effective way to improve rural health experience [22]. Second, our study highlights that rural women with BC travel considerable distances to receive treatment, which results in disruptions to work and family routines that may far exceed those experienced by women in urban areas. Distance has been consistently documented as an issue in rural health literature [23–25]. Some of the women interviewed highlighted how service providers were alert to these difficulties and made efforts to make appointments to minimise disruption. This type of sensitivity to the needs of rural women is commendable and should be replicated.

Limitations

There are several study limitations. First, there is inevitably a limit to the generalisability of these findings beyond this sample, which was drawn exclusively from a BC charity database. Second, a further potential bias is the low response rate (n = 44; 25 %) and future rural-based studies should therefore consider alternative methods to administer a survey [21]. Third, we did not include an urban comparator group, which would have enabled us to draw direct comparisons between rural and urban unmet needs. Fourth, we are unable to report the extent to which supportive care needs change over time and therefore recommend longitudinal studies are conducted to address this limitation. Fifth, the survey instrument was not designed to examine supportive care needs in rural areas, which means that unmet needs arising from rurality may go underreported. Nevertheless, the interviews that we conducted raised a key unmet need highly relevant to rural women with BC, which was travel distance from treatment hubs. Research instruments sensitive to supportive care needs in rural areas should be developed.

Recommendations for policy and practice

Rural women with BC report similar unmet needs to their urban counterparts. Fear of recurrence is a key unmet need that should be addressed for all women with BC. However, they also report unique unmet needs because of rural location. Thus, it is critical that cancer services address the additional unmet needs of rural women with BC and, in particular, needs relating to distance from services. We recommend the following changes in policy and practice to address unmet needs of rural women with BC, many of which may be equally relevant for urban women with BC:

Address lack of or inadequate information about treatment and side effects. This information should be specifically tailored to the experience and needs of the patient. That is, provide individualised rather than general information.

Fit appointments around the needs of the patient to minimise disruption to work or family routines. That is, fit treatment around the needs of the patient and not the needs of the service.

Address lack of care coordination from the point of diagnosis to long-term follow-up. Patients need to have a total overview of their care and be able to visualise where they are on the care pathway. That is, give a total overview of their care from start to finish.

Address lack of support to manage fear of recurrence.

Address lack of support to manage the impact of cancer on the family.

Consider a greater role for generalist health professionals to address support care needs of rural women with breast cancer.

Consider a greater role for health technologies. Telemedicine can transcend geographical distance and permit women living in rural areas to share experiences and learn from and teach each other and should be encouraged for the provision of information and support to women in rural settings, where such services may be especially beneficial [26].

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

(DOCX 21 kb)

(DOCX 23 kb)

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all of the women affected by breast cancer who participated in the study. All who took part gave most generously of their time. We would also like to thank the Self Management IMPACT Fund for Scotland provided by the Scottish Government and administered by Health and Social Care Alliance Scotland (the ALLIANCE) for funding this study.

Conflicts of interest

None.

References

- 1.Cancer Research UK (CRUK) (2014) http://publications.cancerresearchuk.org/downloads/Product/CS_KF_WORLDWIDE.pdf. Accessed 9 July 2014

- 2.Katanoda K, Matsuda T. Five-year relative survival rate of breast cancer in the USA, Europe and Japan. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2014;44(6):611. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyu073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ganz PA, Kwan L, Stanton AL, et al. Physical and psychosocial recovery in the year after primary treatment of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(9):1101–1109. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.8043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tomich PL, Hegelson VS. Five years later a cross-sectional comparison of breast cancer survivors with health women. Psycho-Oncology. 2002;11:54–169. doi: 10.1002/pon.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carr W, Wolfe S. Unmet needs as sociomedical indicators. Int J Health Serv. 1976;6:417–429. doi: 10.2190/MCG0-UH8D-0AG8-VFNU. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fiszer C, Dolbeault SS, Brédart A. Prevalence, intensity, and predictors of the supportive care needs of women diagnosed with breast cancer: a systematic review. Psycho-Oncology. 2014;23:361–374. doi: 10.1002/pon.3432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bettencourt BA, Schlegel RJ, Talley AE, Molix LA. The breast cancer experience of rural women: a literature review. Psycho-Oncology. 2007;16:875–887. doi: 10.1002/pon.1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Butow PN, Phillips F, Schweder J, et al. Psychosocial well-being and supportive care needs of cancer patients living in urban and rural/regional areas a systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20(1):1–22. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1270-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andrykowski MA, Burris JL. Use of formal and informal mental health resources by cancer survivors: differences between rural and nonrural survivors and a preliminary test of the theory of planned behaviour. Psycho-Oncology. 2010;19:1148–1155. doi: 10.1002/pon.1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Statistics (2011), Rural Scotland key facts, Scottish Government, 2011

- 11.Geographic Information Science & Analysis Team (2010) Scottish Government urban/rural classification, 2009–2010, Scottish Government, Edinburgh

- 12.Boyes A, Girgis A, Lecathelinais C. Brief assessment of adult cancer patients’ perceived needs: development and validation of the 34-item Supportive Care Needs Survey (SCNS-SF34) J Eval Clin Pract. 2009;15:602–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2008.01057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boyes AW, Girgis A, D’Este C, Zucca A. Prevalence and correlates of cancer survivors’ supportive care needs 6 months after diagnosis: a population-based cross-sectional study. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:150. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sturges JE, Hanrahan KJ. Comparing telephone and face-to-face qualitative interviewing: a research note. Qual Res. 2004;4(1):107–118. doi: 10.1177/1468794104041110. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sweet L. Telephone interviewing: is it compatible with interpretive phenomenological research? Contemp Nurse. 2002;12:58–63. doi: 10.5172/conu.12.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tausig JE, Freeman EW. The next best thing to being there: conducting the clinical research interview by telephone. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1988;58:418–427. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1988.tb01602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spencer L, Ritchie J, O’Connor W. Analysis: practices, principles and processes. In: Richie J, Lewis J, editors. Qualitative research practice. London: Sage; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simard S, Thewes B, Humphris G, Dixon M, Hayden C, Mireskandari S, Ozakinci G. Fear of cancer recurrence in adult cancer survivors: a systematic review of quantitative studies. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7:300–322. doi: 10.1007/s11764-013-0272-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Northouse LL. The impact of cancer in women on the family. Cancer Pract. 1995;3(3):134–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bourke L, Taylor J, Humphreys JS, Wakerman J. “Rural health is subjective, everyone sees it differently”: understandings of rural health among Australian stakeholders. Health Place. 2013;24:65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schopp LH, Johnstone B, Reid-Arndt S (2005) Telehealth brain injury training for rural behavioral health generalists: supporting and enhancing rural service delivery networks. Prof Psychol: Res Pract 36(2). Special Section: Rural Practice and Training: 158–163.

- 22.Johansson AM, Lindberg SS. The views of health-care personnel about video consultation prior to implementation in primary health care in rural areas. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2014;15:170–179. doi: 10.1017/S1463423613000030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen J. The effect of distance on use of outpatient services in a rural mental health center. Hosp Commun Psychiatr. 1972;23(3):79–80. doi: 10.1176/ps.23.3.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hartley D. Rural health disparities, population health, and rural culture. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(10):1675–1678. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.94.10.1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eberhardt MS, Pamuk ER. The importance of place of residence: examining health in rural and nonrural areas. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(10):1682–1686. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.94.10.1682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Solberg S, Church J, Curran V. Experiences of rural women with breast cancer receiving social support via audioconferencing. J Telmed Telecare. 2003;9(5):282–287. doi: 10.1258/135763303769211300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 21 kb)

(DOCX 23 kb)