Abstract

Background

Suicide is a leading cause of death for young people. Children living in sub-Saharan Africa, where HIV rates are disproportionately high, may be at increased risk.

Aims

To identify predictors, including HIV status, of suicidal ideation and behaviour in Rwandan children aged 10–17.

Method

Matched case–control study of 683 HIV-positive, HIV-affected (seronegative children with an HIV-positive caregiver), and unaffected children and their caregivers.

Results

Over 20% of HIV-positive and affected children engaged in suicidal behaviour in the previous 6 months, compared with 13% of unaffected children. Children were at increased risk if they met criteria for depression, were at high-risk for conduct disorder, reported poor parenting or had caregivers with mental health problems.

Conclusions

Policies and programmes that address mental health concerns and support positive parenting may prevent suicidal ideation and behaviour in children at increased risk related to HIV.

Across 90 countries, suicide has been found to be the third leading cause of death for females and the fourth leading cause for males aged 15–19 years old, accounting for more than 9% of the deaths of young people.1 Younger adolescents are also affected, with suicide being the tenth leading cause of death for adolescents aged 10–14 years old.2 A cross-national survey of adults estimated lifetime prevalence rates of suicidal ideation at 9.2% and suicide attempt at 2.7%, with the strongest risk factors comprising being female, less educated and having a mental health disorder.3 Although suicide risk has been understudied in sub-Saharan Africa, there is some evidence to suggest that rates of suicidal ideation and attempt might be higher among individuals living in this region, with studies finding rates of suicidal behaviour among schoolchildren ranging from 19.6% in Uganda to a high of 31.9% in Zambia.4 One study in South Africa found that more than one in five adolescents aged 13–19 reported having attempted suicide in the past 6 months.5 These observed elevated rates of suicidal ideation and behaviour in youth in sub-Saharan Africa may be a result, in part, of disproportionately high rates of stressors with known associations with suicidality, such as HIV, which has been observed to increase psychosocial stress and hopelessness.6–8 Additionally, children affected by HIV have been found to be at increased risk for mental health problems because of, in part, parental loss and disrupted parent–child relationships, increased risk of family conflict, stigma, community rejection, economic insecurity, poor educational outcomes, caregiver depression and physical impairment;9–15 some of these factors have also been associated with increased suicide risk in youth in sub-Saharan Africa.16

Many countries in sub-Saharan Africa, including Rwanda, have made significant progress in improving the health outcomes of individuals who are living with HIV.17–19 With increasing access to antiretroviral therapy,18,19 HIV is rapidly becoming a chronic illness in many countries. However, the broader consequences of HIV on individuals and within families, including possible increased risk for suicide, remain largely unaddressed. As global attention concerning children directly and indirectly affected by HIV/AIDS expands, greater understanding is needed on suicide risk among children living with HIV, children affected by HIV (children with an HIV-positive (HIV+) caregiver or a caregiver who died because of AIDS) and those unaffected by HIV, and the risk and protective factors that may influence this risk. This study is a secondary analysis of existing data from a case–control study conducted to compare mental health problems among children living with HIV, children affected by HIV and children unaffected by HIV.15 The matched nature of the design allows us to examine suicidal ideation and behaviour and how these experiences may be associated with HIV status. Furthermore, the study aims to understand how differences in demographics, mental health, parenting, harsh discipline, community social support and stigma predict suicidal ideation and behaviour while accounting for the influence of HIV.

Method

Population and study design

This study was conducted by the Harvard School of Public Health, the Rwandan Ministry of Health, and Partners In Health/Inshuti Mu Buzima (PIH/IMB), a non-governmental organisation supporting health system strengthening in Rwanda. The study was conducted within the catchment area of two district hospitals located in southern Kayonza and Kirehe Districts, which serve as referral hubs for 24 health centres that provide routine HIV services.18,20 In the catchment area of these hospitals, an electronic medical record (EMR) system is maintained for patients receiving HIV care.

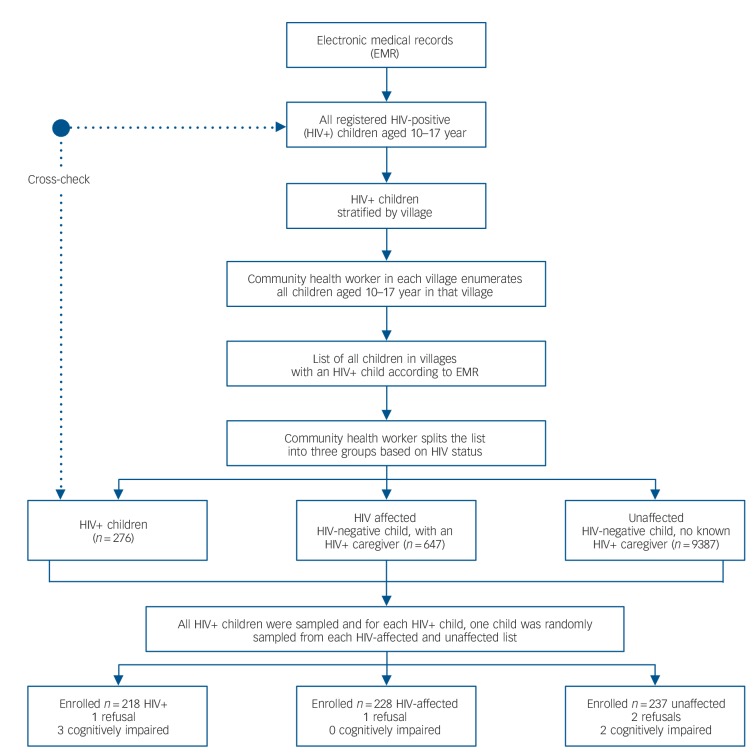

A case–control study design was used to enrol a sample of n = 683 children stratified by HIV status from March to December 2012.15 Sampling followed a multiple-step process (Fig. 1). First, the EMR identified children living with HIV aged 10–17 who were then stratified by village. For each village with an EMR-identified child living with HIV, a community health worker compiled lists of all children aged 10–17. Rwandan community health workers track approximately 50 households per village, making this procedure feasible. Second, specialised community health workers knowledgeable of all residents in their assigned villages who were living with HIV stratified the lists by HIV status, which revealed 37 additional children living with HIV who were added to the final HIV+ list. Children residing with a caregiver living with HIV or who had a caregiver who died because of AIDS made up the list of HIV-affected children. The remaining children, confirmed by community health workers to be neither living with HIV or affected by HIV in their family, made up the list of unaffected children. If the index child from the HIV+ list consented to participate, a random number generator was used to select HIV-affected and unaffected children in the same village. If the child or their caregivers did not provide assent/consent, a different participant was randomly sampled and invited to participate. This procedure allowed for a case–control design matched on village to control for geographic differences. Matching on age and gender was not necessary given the relatively large sample size, which led to approximately equal distribution of demographic variables across groups.

Fig. 1.

Sampling procedure.

A target sample size of 250 participants per group (n = 750) was estimated to yield 82% power to detect standardised expected group mean differences, equivalent to 0.25 standard deviations at α = 0.05.21 The number of eligible children living with HIV fell just short of this target, with 683 children and one of their caregivers participating in the study (participation rate over 95%). Children living with HIV were ineligible if they moved outside the study area, had since tested HIV-negative, were under 10 years of age or lived in a child-headed household. Eligible children were aged 10–17 years and had lived in Kayonza or Kirehe Districts for at least 1 month. For each child, a cohabiting adult caregiver (selected as ‘knowing the child best’) reported on their own mental health, the child's mental health, family and community relationships and family socioeconomic status (SES). Exclusion criteria were active psychosis or severe cognitive impairment in the invited child (as identified by study psychologists). Although no exclusions were made because of cognitive impairment, five of the younger children were not able to fully complete the self-report because of poor comprehension of the items; for two of these children, caregivers completed caregiver reports. During data collection, local psychologists travelled with the research team to respond to serious risk-of-harm situations (for example suicidality) and make referrals to the health system and local service programmes as appropriate. Overall, 5% of the sample received additional referral to mental health services as a result of such immediate risk-of-harm issues. This study received approval from the Harvard School of Public Health Office of Human Research Administration and the Rwanda National Ethics Committee. Independent parental/guardian informed consent and child assent was obtained for all study participants.

Procedures

Rwandan research assistants orally conducted all assessments in Kinyarwanda, the local language, with oversight from the study field coordinators and investigators. Children and caregivers were assessed for mental health problems as well as protective and risk factors. Research assistants received 2 weeks of training in research ethics, data-collection methods and interviewing children and parents. Interviews were carried out in participants' homes, with child and caregiver interviews conducted separately. All data were collected on Android smart phones using DataDyne's EpiSurveyor. De-identified data was uploaded to DataDyne's secure website where it was accessed for analysis.

Measures

All measures were subjected to rigorous translation procedures, and measures of suicidal ideation and behaviour, child mental health, good parenting and social support were locally validated with 378 child–caregiver dyads.22–24

Demographics

Children reported their gender, age, and whether they were currently attending school and had experienced the death of a caregiver. Caregivers reported on whether they were a single caregiver (typically a female-headed household), and family SES, which was measured using the wealth index25 from the Rwanda Demographic and Health Survey.26

Child mental health

Children and their caregivers reported on child depression and conduct problems. The 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale for Children (CES-DC)27 assessed symptoms of depression and was scored zero (never) to three (often), and the scale score was the sum. The CES-DC was validated in this population using a process described previously, which identified a cut-off score of 30 as being optimally able to identify children with a clinical depression diagnosis,23 and so children with scores greater than or equal to 30 were classified as probably having depression. The scale demonstrated good internal consistency (α = 0.88).

Conduct problems were measured using the short form of the Youth Conduct Problems Scale–Rwanda (YCPS-R), a locally-derived scale based on qualitative data,24 as standardised measures of conduct disorder did not match well with the local construct.28 The scale contains 11 items scored zero (never) to three (often) and was scored as the sum. The internal reliability in this sample was excellent (α = 0.89). A validity study of the YCPS-R identified scores of 5 for the child report, 9 for the caregiver report on females and 14 for the caregiver report on males as being the cut-off scores best able to identify children diagnosed with conduct disorder;24 these were used as cut-off scores for conduct problems. Although the YCPS-R questions used in the validity study were the same as those used in this study, the time frame during the validity study was 1 week whereas the one used in this study was 6 months, and so in this study, the YCPS-R cut-offs should be viewed as identifying children at higher risk of conduct disorder, rather than children scoring above the diagnostic threshold.

Parenting

Children and caregivers reported on the good parenting and severe physical punishment the children received, and caregivers reported on caregiver mental health. Good parenting, a protective factor derived from previous qualitative research,29 was assessed by 16 locally derived items and 16 items from the Parental Acceptance and Rejection Questionnaire.30 Parenting was scored on a four-point Likert scale, zero (never) to three (every day), and the scale score was the mean. The local parenting scale performed well in validity testing (α = 0.94, test–re-test r = 0.87) and the combined scale had excellent internal reliability in this sample (α = 0.93). Severe physical punishment was measured using the severe physical punishment subscale of UNICEF's Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey's Child Discipline module,31 that includes two items (‘You were slapped in the face, in the head, or in the ears’ and ‘You were severely beaten’), scored zero for no, one for yes, and the scale was scored as a binary variable of whether or not the child reported either form of punishment in the past month. Caregiver mental health was assessed using the Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL-25),32 a 25-item measure of depression and anxiety previously tested and validated for use in Rwanda (α = 0.94 in this sample).33

Community support and HIV-related stigma

Children and caregivers reported on the community support and HIV-related stigma received and experienced by the child. Community support was measured using an adapted Inventory of Socially Supportive Behaviors (ISSB).34 The ISSB assesses how often an individual receives informational, instrumental and emotional support on a five-point Likert scale (zero to four) ranging from ‘never’ to ‘nearly all the time’. The adapted Rwandan scale contains 33 items (23 from the original ISSB and 10 drawn from qualitative data). The scale demonstrated good internal consistency (α = 0.95). HIV-related stigma was measured by 13 items adapted from the Young Carer's Project.35 Frequency of experiencing interpersonal interactions indicative of stigma was reported on a three-point Likert scale (zero to two) of ‘never’, ‘sometimes’ or ‘often/a lot’. When a stigma item was endorsed, children were then asked to report why they thought it happened. If children endorsed HIV as the reason for experiencing any of the stigma items, then they received a score of one, all other children received a score of zero.

Suicidal ideation and behaviour

Children and caregivers responded to two items from the Youth Self-Report (YSR) Internalizing Subscale36 to assess child suicidal ideation and behaviour during the previous 6 months. Suicidal ideation was assessed by ‘You thought about killing yourself’ and suicidal behaviour was assessed by ‘You deliberately tried to hurt or kill yourself’. If either the child or caregiver endorsed these items, children were deemed to have had suicidal ideation or behaviour. Although only two items from the YSR were used in this analysis, the complete YSR Internalizing Subscale had 16 items and it demonstrated strong internal reliability (α = 0.89) in this sample.

Analyses

Summary statistics were computed for each outcome and predictor variable. Univariate logistic regressions were run to assess the relationship between each predictor variable (including HIV status) and suicidal ideation and behaviour in the past 6 months. Multicollinearity between predictor variables was assessed by examination of the correlation matrix and by computing the variance inflation factors (VIF) using the Stata version 12 command COLLIN.37 If predictor variables were not multicollinear, they were included in multiple logistic regressions predicting suicidal ideation and behaviour. All analyses were conducted using Stata version 12.

Results

Demographics

The final sample contained a total of n = 683 children, 218 of whom were living with HIV, 228 HIV-affected, and 237 unaffected by HIV in their family. The mean age of the children was 13.60 (s.d. = 2.19), and 51.54% were females. Half of the children (52.05%) were being raised by a single caregiver, almost one-third (28.97%) had experienced the death of a caregiver, but 90.40% were currently attending school. Mental health problems were common in the sample, with 25.70% of children scoring above the diagnostic threshold for depression, and 30.10% of children scoring in the high-risk range for conduct problems. See Tables 1 and 2 for summary statistics of all study variables.

Table 1.

Univariate logistic regressions predicting suicidal ideation and behaviour in past 6 months for HIV status, demographics and child mental health

| Suicidal ideation |

Suicidal behaviour |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Yes | No (n = 542) | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Yes (n= 125) | No (n = 558) | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | N | |

| HIV status, unaffected: n (%) | 237 (34.70) | 44 (18.57) | 193 (81.43) | Reference | 30 (12.66) | 207 (87.34) | Reference | 683 |

| HIV status, affected: n (%) | 228 (33.38) | 51 (22.37) | 177 (77.63) | 1.26 (0.80–1.99) | 49 (21.49) | 179 (78.51) | 1.89* (1.15–3.10) | 683 |

| HIV status, HIV-positive: n (%) | 218 (31.92) | 46 (21.10) | 172 (78.90) | 1.17 (0.74–1.86) | 46 (21.10) | 172 (78.90) | 1.85* (1.12–3.05) | 683 |

| Female, n (%) | 351 (51.54) | 75 (21.37) | 276 (78.63) | 1.09 (0.75–1.58) | 69 (19.66) | 282 (80.34) | 1.20 (0.81–1.77) | 681 |

| Age, mean (s.d.) | 13.60 (2.19) | 14.12 (2.08) | 13.47 (2.20) | 1.15** (1.05–1.25) | 14.25 (2.19) | 13.46 (2.20) | 1.18*** (1.08–1.29) | 681 |

| Death of caregiver, n (%) | 195 (28.97) | 44 (22.56) | 151 (77.44) | 1.17 (0.78–1.76) | 42 (21.54) | 153 (78.46) | 1.41 (0.93–2.14) | 673 |

| Single caregiver, n (%) | 355 (52.05) | 87 (24.51) | 268 (75.49) | 1.64** (1.12–2.40) | 81 (22.82) | 274 (77.18) | 1.90** (1.27–2.84) | 682 |

| Not in school, n (%) | 65 (9.60) | 22 (33.85) | 43 (66.15) | 2.19** (1.26–3.80) | 19 (29.23) | 46 (70.77) | 2.04* (1.15–3.63) | 677 |

| Socioeconomic status, mean (s.d.) | <0.001 (1.00) | −0.06 (1.05) | 0.02 (0.99) | 0.92 (0.76–1.12) | −0.16 (0.92) | 0.04 (1.02) | 0.81* (0.65–1.00) | 681 |

| Depression, child reported: n (%) | 175 (25.70) | 78 (44.57) | 97 (55.43) | 5.65*** (3.80–8.42) | 60 (34.29) | 115 (65.71) | 3.54*** (2.36–5.32) | 681 |

| Depression, caregiver reported: n (%) | 164 (24.15) | 60 (36.59) | 104 (63.41) | 3.14*** (2.11–4.67) | 55 (33.54) | 109 (66.46) | 3.26*** (2.16–4.92) | 679 |

| Conduct problems, child reported: n (%) | 205 (30.10) | 80 (39.02) | 125 (60.98) | 4.35*** (2.95–6.42) | 66 (32.20) | 139 (67.80) | 3.36*** (2.25–5.01) | 681 |

| Conduct Problems, caregiver reported: n (%) | 123 (18.01) | 47 (38.21) | 76 (61.79) | 3.05*** (1.99–4.67) | 49 (39.84) | 74 (60.16) | 4.20*** (2.72–6.49) | 683 |

P<0.05,

P<0.01,

P<0.001.

Table 2.

Univariate logistic regressions predicting suicidal ideation and behaviour in past 6 months for parenting, community support and HIV-related stigma

| Suicidal ideation |

Suicidal behaviour |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Yes | No (n = 542) | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Yes (n = 125) | No (n = 558) | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | N | |

| Parenting | ||||||||

| Caregiver mental health, mean (s.d.) | 1.09 (0.63) | 1.34 (0.66) | 1.02 (0.61) | 2.21*** (1.64–2.99) | 1.23 (0.64) | 1.06 (0.62) | 1.53** (1.13–2.08) | 683 |

| Good parenting, child reported: mean (s.d.) | 2.38 (0.55) | 2.07 (0.63) | 2.46 (0.49) | 0.30*** (0.22–0.42) | 2.01 (0.66) | 2.47 (0.48) | 0.26*** (0.18–0.37) | 681 |

| Good parenting, caregiver reported, mean (s.d.) | 2.58 (0.33) | 2.46 (0.33) | 2.60 (0.30) | 0.31*** (0.18–0.52) | 2.45 (0.39) | 2.60 (0.31) | 0.30*** (0.18–0.51) | 682 |

| Severe physical punishment, child reported: n (%) | 161 (23.57) | 41 (25.47) | 120 (74.53) | 2.42*** (1.62–3.61) | 41 (25.47) | 120 (74.53) | 1.78** (1.17–2.72) | 683 |

| Severe physical punishment, caregiver reported: n (%) | 68 (9.96) | 24 (35.29) | 44 (64.71) | 2.32** (1.36–3.97) | 18 (26.47) | 50 (73.53) | 1.71 (0.96–3.05) | 683 |

| Community support, mean (s.d.) | ||||||||

| Child reported | 1.90 (0.76) | 1.64 (0.73) | 1.97 (0.75) | 0.56*** (0.43–0.72) | 1.59 (0.79) | 1.97 (0.74) | 0.51*** (0.39–0.67) | 681 |

| Caregiver reported | 1.56 (0.69) | 1.46 (0.70) | 1.58 (0.69) | 0.76* (0.58–1.00) | 1.42 (0.76) | 1.59 (0.67) | 0.69* (0.52–0.93) | 683 |

| HIV-related stigma, n (%) | ||||||||

| Child reported | 110 (16.11) | 35 (31.82) | 75 (68.18) | 2.06** (1.31–3.23) | 28 (25.45) | 82 (74.55) | 1.68* (1.04–2.71) | 683 |

| Caregiver reported | 188 (27.53) | 42 (22.34) | 146 (77.66) | 1.15 (0.77–1.73) | 41 (21.81) | 147 (78.19) | 1.36 (0.90–2.07) | 683 |

P<0.05,

P<0.01,

P<0.001.

Suicidal ideation and behaviour and HIV status

Of the 683 children, 141 (20.64%) had reported suicidal ideation and 125 (18.30%) had reportedly engaged in self-harm or attempted suicide during the previous 6 months. As hypothesised, children who were living with HIV (OR = 1.85, 95% CI = 1.12–3.05) or HIV-affected (OR = 1.89, 95% CI = 1.15–3.10) were at greater risk of suicidal behaviour compared with children who were not affected by HIV, with 21.10% of those living with HIV and 21.49% of HIV-affected children endorsing suicidal behaviour compared with 12.66% of children not affected by HIV (Table 1). HIV status was not significantly predictive of suicidal ideation.

Predictors of suicidal ideation and behaviour: unadjusted logistic regression results

Results of the univariate logistic regressions indicated that older children, those with a single caregiver, and those not in school were at increased risk for suicidal ideation and behaviour, whereas those living in families with higher SES were at decreased risk for suicidal behaviour (Table 1). Neither gender nor having a caregiver die predicted suicidal ideation or behaviour. Child depression and conduct problems both substantially increased the risk of suicidal ideation and behaviour.

Children with self-reported depression scores above the diagnostic cut-off were 5.65 times more likely to have suicidal ideation and 3.54 times more likely to have suicidal behaviour than those below clinical cut-off. Children whose caregivers reported that their depression scores were above the diagnostic cut-off were more than three times more likely to have suicidal ideation and behaviour. Children at high risk for conduct problems were also much more likely to have suicidal ideation and behaviour, with increased odds of 4.35 and 3.36, respectively (P<0.001, Table 1).

Good parenting was associated with decreased risk of ideation (OR = 0.30, P<0.001) and behaviour (OR = 0.26, P<0.001), whereas children who reported experiencing severe physical punishment had more then double the risk of suicidal ideation (OR = 2.42, P<0.001) and almost double the risk of suicidal behaviour (OR = 1.78, P = 0.008, Table 2). Children whose caregivers reported more mental health problems themselves were also at increased risk for suicidal ideation (OR = 2.21, P<0.001) and behaviour (OR = 1.53, P = 0.006). Finally, community support predicted less suicidal ideation (OR = 0.56, P<0.001) and behaviour (OR = 0.51, P<0.001) whereas child-reported HIV-related stigma was associated with significantly increased risk of ideation (OR = 2.06, P = 0.002) and behaviour (OR = 1.68, P = 0.04, Table 2).

Predictors of suicidal ideation and behaviour: multiple logistic regression results

Results of the mulicollinearity analysis found no evidence of collinearity between predictors, as the highest correlation was r = −0.48 between the dummy codes for those living with HIV and HIV-affected, and the mean VIF was 1.31, with the highest VIF being 2.07. Results of the multiple regressions are presented in Table 3. Results indicated that child mental health symptoms significantly increased the odds of suicidal ideation and behaviour, whereas child report of good parenting decreased the odds. Caregiver mental health symptoms increased the odds of child suicidal ideation, but not behaviour. After accounting for these factors, none of the other predictors were significantly associated with suicidal ideation or behaviour.

Table 3.

Multiple logistic regressions predicting suicidal ideation and behaviour in 6 months

| Suicidal ideation |

Suicidal behaviour |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted OR | 95% CI | P | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | P | |

| HIV status | ||||||

| HIV-affected | 0.86 | 0.49–10.53 | 0.62 | 1.62 | 0.88–2.98 | 0.12 |

| HIV-positive | 1.04 | 0.52–2.08 | 0.91 | 1.80 | 0.87–3.69 | 0.11 |

| Demographics | ||||||

| Female | 1.00 | 0.63–1.57 | 0.99 | 1.28 | 0.80–2.05 | 0.30 |

| Age | 1.05 | 0.94–1.17 | 0.41 | 1.11 | 0.99–1.25 | 0.08 |

| Death of caregiver | 1.01 | 0.59–1.73 | 0.97 | 1.05 | 0.61–1.81 | 0.86 |

| Single caregiver | 1.03 | 0.64–1.68 | 0.90 | 1.14 | 0.69–1.87 | 0.61 |

| Not in school | 1.22 | 0.57–2.63 | 0.61 | 0.92 | 0.43–1.98 | 0.83 |

| Socioeconomic status | 1.26 | 1.00–1.59 | 0.06 | 1.09 | 0.84–1.40 | 0.52 |

| Child mental health | ||||||

| Depression, child reported | 3.16 | 1.97–5.09 | <0.001 | 1.78 | 1.07–2.97 | 0.03 |

| Depression, caregiver reported | 1.93 | 1.15–3.23 | 0.01 | 2.02 | 1.19–3.44 | 0.009 |

| Conduct problems, child reported | 2.45 | 1.52–3.95 | <0.001 | 1.75 | 1.06–2.89 | 0.03 |

| Conduct problems, caregiver reported | 1.18 | 0.67–2.09 | 0.57 | 2.38 | 1.36–4.19 | 0.003 |

| Parenting | ||||||

| Caregiver mental health | 1.54 | 1.03–2.29 | 0.03 | 0.90 | 0.60–1.37 | 0.64 |

| Good parenting, child reported | 0.60 | 0.38–0.95 | 0.03 | 0.44 | 0.27–0.71 | 0.001 |

| Good parenting, caregiver reported | 0.65 | 0.32–1.31 | 0.22 | 0.70 | 0.34–1.41 | 0.32 |

| Severe physical punishment, child reported | 1.26 | 0.75–2.12 | 0.37 | 1.01 | 0.58–1.77 | 0.97 |

| Severe physical punishment, caregiver reported | 1.31 | 0.65–2.64 | 0.45 | 0.86 | 0.40–1.83 | 0.69 |

| Community support and HIV-related stigma | ||||||

| Community support, child reported | 0.86 | 0.60–1.22 | 0.40 | 0.85 | 0.59–1.23 | 0.39 |

| Community support, caregiver reported | 0.79 | 0.56–1.13 | 0.20 | 0.75 | 0.52–1.09 | 0.13 |

| HIV-related stigma, child reported | 1.11 | 0.58–2.13 | 0.76 | 0.70 | 0.36–1.38 | 0.31 |

| HIV-related stigma, caregiver reported | 0.81 | 0.03–8.07 | 0.65 | 1.01 | 0.58–1.77 | 0.97 |

Child mental health

Results of the multiple logistic regression found that children who self-reported and whose caregivers reported depression symptoms above the diagnostic threshold were two to three times more likely to have suicidal ideation and two times more likely to have suicidal behaviour than those with depression symptoms below the diagnostic threshold. Moreover, children who were at high risk for conduct problems were 2.5 times more likely to have suicidal ideation and 1.75 times more likely to have suicidal behaviour. Children whose caregivers reported that they were high risk for conduct problems were more than twice as likely to have suicidal behaviour, but were no more likely to have suicidal ideation compared with those at low risk for conduct problems.

Parenting

Child report of good parenting was associated with decreased risk of suicidal ideation (OR = 0.60, P = 0.03) and behaviour (OR = 0.44, P = 0.001), however caregiver report of good parenting was not associated with any differences in suicide risk. Caregiver mental health problems increased the risk of suicidal ideation (OR = 1.54, P = 0.03), but was not associated with risk for suicidal behaviour.

Discussion

Main findings

Throughout the world suicidal ideation and behaviour, particularly by children, is often hidden, unrecognised and misunderstood. However, suicidal behaviour in children demands attention, as the results of this study found alarmingly high rates of suicidal ideation and behaviour in this sample in sub-Saharan Africa, particularly among youth who are living with HIV and who have a caregiver living with HIV – more than one in five of these children reported a previous suicide or self-harm attempt in the past 6 months. Children who are living with HIV or who are affected by HIV may be at higher risk of suicide because of higher rates of mental health concerns, poorer parenting and caregivers with their own mental health concerns. These risk factors seem to put children at higher risk regardless of HIV status and may also make it much harder for these children to access care and support.

Attention to mental health globally is sparse, particularly in much of sub-Saharan Africa and other low- and middle-income country settings where mental health services and human resources for mental healthcare are extremely limited and risk factors, such as poverty, are high. Child and caregiver mental health and parenting factors remained the strongest predictors of suicidal ideation and behaviour even after accounting for other risk factors such as SES, death of caregivers, and social support and HIV-related stigma. The results of this study demonstrate the importance of tackling child and adult mental health concerns and supporting positive parenting skills with families in low- and middle-income countries, in addition to addressing poverty and social support.

Strengths and limitations

Study limitations must be acknowledged, including the fact that there was no capability to conduct clinical testing at the time of data collection in order to confirm HIV status biomarkers for children and their caregivers. However, the community health workers in Rwanda provide directly observed therapy to all patients living with HIV in the PIH/IMB supported districts, and so we are confident about the correct categorisation of children by HIV status. Also, reports of suicidal ideation and behaviour, child mental health, and risk and protective factors such as good parenting, social support, HIV-related stigma and harsh punishment were collected through retrospective self-reports, and may be subject to recall and reporting bias. However, we believe a strength of the study is that this information was reported by both the child and one of their caregivers, which may help to offset some of the self-reporting concerns. Additionally, many of the measures, including those for mental health, good parenting and social support, were previously validated in Rwanda, increasing the likelihood of valid and reliable results.

Implications

Effective suicide prevention is a societal challenge that would benefit from coordinated responses by family, educational and community partners, in addition to health service providers and systems. Suicide prevention public health campaigns that seek to broaden awareness of, and sensitivity to, mental health needs and suicide risk factors and behaviour is needed at the individual, family and community level, as many people may be unaware of the risk of suicidal ideation in children and ways to prevent and address it. Moreover, national health systems may need to provide training and assistance to local community providers, such as community health workers, to develop and maintain case identification, referral and service delivery programmes for children and adults with mental health concerns that can be sustained in low-resource settings.38 In addition, prevention interventions such as the Family Strengthening Intervention39 that seeks to improve parenting skills and prevent child mental health problems in families affected by HIV in Rwanda may help address some of these needs.

Acknowledgments

This work was made possible by the collaboration and dedication of the Rwandan Ministry of Health and Partners In Health/Inshuti Mu Buzima. We are endlessly grateful to the local research team who carried out these interviews and to the study participants and their families who shared their experiences with us.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

None.

Funding

This study was primarily funded by the Harvard University Center for AIDS Research (CFAR) Grant#P30 AI060354, which supported design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. Additional funding was from Grant#1K01MH07724601 A2 from the National Institute of Mental Health, the Peter C. Alderman Foundation, the Harvard Center for the Developing Child, the François-Xavier Bagnoud Center for Health and Human Rights, the Harvard School of Public Health Career Incubator Fund and the Julie Henry Family Development Fund.

References

- 1. Wasserman D, Cheng Q, Jiang G-X. Global suicide rates among young people aged 15–19. World Psychiatry 2005; 4: 114–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Patton GC, Coffey C, Sawyer SM, Viner RM, Haller DM, Bose K, et al. Global patterns of mortality in young people: a systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet 2009; 374: 881–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, Alonso J, Angermeyer M, Beautrais A, et al. Cross-national prevalence and risk factors for suicidal ideation, plans and attempts. Br J Psychiatry 2008; 192: 98–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Swahn M, Bossarte R, Elimam DM, Gaylor E, Jayaraman S. Prevalence and correlates of suicidal ideation and physical fighting: a comparison between students in Botswana, Kenya, Uganda, Zambia and the USA. Int Public Health J 2010; 2: 195–206. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shilubane HN, Ruiter RA, van den Borne B, Sewpaul R, James S, Reddy PS. Suicide and related health risk behaviours among school learners in South Africa: results from the 2002 and 2008 national youth risk behaviour surveys. BMC Public Health 2013; 13: 926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cooperman NA, Simoni JM. Suicidal ideation and attempted suicide among women living with HIV/AIDS. J Behav Med 2005; 28: 149–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Komiti A, Judd F, Grech P, Mijch A, Hoy J, Lloyd JH, et al. Suicidal behaviour in people with HIV/AIDS: a review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2001; 35: 747–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gielen AC, McDonnell KA, O'Campo PJ, Burke JG. Suicide risk and mental health indicators: Do they differ by abuse and HIV status? Womens Health Issues 2005; 15: 89–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Doku P. Parental HIV/AIDS status and death, and children's psychological wellbeing. Int J Ment Health Syst 2009; 3: 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Murphy DA, Greenwell L, Mouttapa M, Brecht ML, Schuster MA. Physical health of mothers with HIV/AIDS and the mental health of their children. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2006; 27: 386–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lester P, Jane Rotheram-Borus M, Lee S-J, Comulada S, Cantwell S, Wu N, et al. Rates and predictors of anxiety and depressive disorders in adolescents of parents with HIV. Vuln Child Youth Stud 2006; 1: 81–101. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Smith Fawzi MC, Eustache E, Oswald C, Surkan P, Louis E, Scanlan F, et al. Psychosocial functioning among HIV-affected youth and their caregivers in Haiti: implications for family-focused service provision in high HIV burden settings. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2010; 24: 147–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cluver LD, Orkin M, Gardner F, Boyes ME. Persisting mental health problems among AIDS-orphaned children in South Africa. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2012; 53: 363–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gadow KD, Angelidou K, Chernoff M, Williams PL, Heston J, Hodge J, et al. Longitudinal study of emerging mental health concerns in youth perinatally infected with HIV and peer comparisons. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2012; 33: 456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Betancourt T, Scorza P, Kanyanganzi F, Fawzi MCS, Sezibera V, Cyamatare F, et al. HIV and child mental health: a case-control study in Rwanda. Pediatrics 2014; 134: e464–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Swahn MH, Palmier JB, Kasirye R, Yao H. Correlates of suicide ideation and attempt among youth living in the slums of Kampala. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2012; 9: 596–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Farmer P, Nutt C, Wagner CM, Sekabaraga C, Nuthulanganti T, Weigel JL, et al. Reduced premature mortality in Rwanda: lessons from success. BMJ 2013; 346: f65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rich ML, Miller AC, Niyigena P, Franke MF, Niyonzima JB, Socci A, et al. Excellent clinical outcomes and high retention in care among adults in a community-based HIV treatment program in rural Rwanda. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2012; 59: e35–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. UNAIDS Country Progress Report: Rwanda. UNAIDS, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Merkel E, Gupta N, Nyirimana A, Niyonsenga SP, Nahimana E, Stulac SN, et al. Clinical outcomes among HIV-positive adolescents attending an integrated and comprehensive adolescent-focused HIV care program in rural Rwanda. J HIV/AIDS Soc Serv 2013; 12: 437–50. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Forsyth BW, Damour L, Nagler S, Adnopoz J. The psychological effects of parental human immunodeficiency virus infection on uninfected children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1996; 150: 1015–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Scorza P, Stevenson A, Canino G, Mushashi C, Kanyanganzi F, Munyanah M, et al. Validation of the “World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule for Children, WHODAS-Child” in Rwanda. PLoS One 2013; 8: e57725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Betancourt T, Scorza P, Meyers-Ohki S, Mushashi C, Kayiteshonga Y, Binagwaho A, et al. Validating the center for epidemiological studies depression scale for children in Rwanda. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2012; 51: 1284–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ng LC, Kanyanganzi F, Munyanah M, Mushashi C, Betancourt TS. Developing and validating the Youth Conduct Problems Scale-Rwanda: a mixed methods approach. PLoS One 2014; 9: e100549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rutstein SO, Johnson K. The DHS Wealth Index. ORC Macro, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ministry of Health. ICF International Rwanda Demographic and Health Survey. Ministry of Health, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Radloff LS. The Use of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale in adolescents and young adults. J Youth Adolesc 1991; 20: 149–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Betancourt TS, Rubin-Smith JE, Beardslee WR, Stulac SN, Fayida I, Safren S. Understanding locally, culturally, and contextually relevant mental health problems among Rwandan children and adolescents affected by HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care 2011; 23: 401–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Betancourt TS, Meyers-Ohki SE, Stulac SN, Barrera AE, Mushashi C, Beardslee WR. Nothing can defeat combined hands (Abashize hamwe ntakibananira): protective processes and resilience in Rwandan children and families affected by HIV/AIDS. Soc Sci Med 2011; 73: 693–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rohner RP, Saavedra JM, Granum EO. Development and Validation of the Parental Acceptance and Rejection Questionnaire: Test Manual. JSAS Catalog of Selected Documents in Psychology (Manuscript 1635) American Psychological Association, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 31. UNICEF Child Disciplinary Practices at Home: Evidence from a Range of Low- and Middle-Income Countries. UNICEF, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Rickels K, Uhlenhuth EH, Covi L. The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL): a self-report symptom inventory. Behav Sci 1974; 19: 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bolton P. Cross-cultural validity and reliability testing of a standard psychiatric assessment instrument without a gold standard. J Nerv Ment Dis 2001; 189: 238–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Barerra M, Sandler IN, Ramsay TB. Preliminary development of a scale of social support. Studies on college students. Am J Community Psychol 1981; 9: 435–47. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Boyes ME, Mason SJ, Cluver LD. Validation of a brief stigma-by-association scale for use with HIV/AIDS-affected youth in South Africa. AIDS Care 2013; 25: 215–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Achenbach TM. Manual for the Youth Self-Report and 1991 Profile. University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ender P. Collinearity Diagnostics. UCLA Office of Academic Computing, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Betancourt TS, Beardslee WR, Kirk CM, Hann K, Zombo M, Mushashi C, et al. Working with vulnerable populations: examples from trials with children and families in adversity due to war and HIV/AIDS. In Global Mental Health Trials (eds Thornicroft G, Patel V.). Oxford University Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Betancourt TS, Ng L, Kirk CM, Munyanah M, Mushashi C, Ingabire C, et al. Family-based prevention of mental health problems in children affected by HIV and AIDS: an open trial. AIDS 2014; 28 (suppl 3): S359–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]