Abstract

Background

Activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) is recommended for monitoring anticoagulant activity in dabigatran-treated patients; however, there are limited data in Japanese patients. To clarify the relationship between plasma dabigatran concentration and aPTT, we analyzed plasma dabigatran concentration and aPTT at various time points following administration of oral dabigatran in a Japanese hospital.

Methods

We enrolled 149 patients (316 blood samples) with non-valvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF) who were taking dabigatran. Patients had a mean age of 66.6±10.0 years (range: 35–84) and 66% were men. Plasma dabigatran concentrations and aPTT were measured using the Hemoclot® direct thrombin inhibitor assay and Thrombocheck aPTT-SLA®, respectively. Samples were classified into eight groups according to elapsed times in hours since oral administration of dabigatran.

Results

Significantly higher dabigatran concentrations were observed in samples obtained from patients with low creatinine clearance (CLCr) (CLCr<50 mL/min). Dabigatran concentrations and aPTT were highest in the 4-h post-administration range. Additionally, there was a significant correlation between plasma dabigatran concentrations and aPTT (y=0.063x+32.596, r2=0.648, p<0.001). However, when plasma dabigatran concentrations were 200 ng/mL or higher, the correlation was lower (y=0.040x+38.034 and r2=0.180); these results were evaluated by a quadratic curve, resulting in an increased correlation (r2=0.668).

Conclusions

There was a significant correlation between plasma dabigatran concentrations and aPTT. Additionally, in daily clinical practice in Japan, plasma dabigatran concentrations and aPTT reached a peak in the 4-h post administration range. Considering the pharmacokinetics of dabigatran, aPTT can be used as an index for risk screening for excess dabigatran concentrations in Japanese patients with NVAF.

Keywords: Dabigatran, Anticoagulants, aPTT, Non-valvular atrial fibrillation

1. Introduction

Dabigatran (Boehringer Ingelheim, Ingelheim, Germany) is a direct thrombin inhibitor, which can be orally administered, and is used to decrease the risk of ischemic stroke in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF). In early phase studies of dabigatran in healthy men, plasma dabigatran concentrations were found to rapidly increase and reach a peak value within 1.5–3 h after oral administration of the drug [1–4]. However, the timing of peak plasma dabigatran concentration in daily clinical practice is not fully understood. When dabigatran was first approved for use, monitoring of clotting time was considered unnecessary; however, cases of large hemorrhage with a markedly prolonged clotting time have been observed. Additionally, in certain situations, monitoring of plasma concentrations and/or the anticoagulant action of dabigatran is required as risk screening for effects of excess dabigatran [5–7]. Therefore, it is recommended that activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) be used as a parameter for monitoring anticoagulant activity in dabigatran-treated patients [1,8,9]. The relationship between aPTT and dabigatran therapy has recently gained a lot of attention; however, there are limited data in Japanese patients [10–14].

Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the correlation between dabigatran concentration and aPTT prolongation in Japanese NVAF patients in daily clinical practice. Additionally, the time-dependent change of these parameters according to the elapsed time after oral dabigatran administration was investigated.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Study population

We measured plasma dabigatran concentrations and aPTT in 316 samples obtained from 149 patients with NVAF who were receiving oral dabigatran therapy without concomitant use of other anticoagulants from November 2012 to December 2013 in Tenri Hospital. Blood sampling was performed at least one week after patients initiated dabigatran therapy. The precise elapsed time after oral administration of dabigatran was calculated as the difference in time between a patient taking dabigatran and the time of blood sampling. On the day of blood sampling, we asked patients to come to the hospital after having breakfast and taking dabigatran as prescribed. A laboratory medical technologist recorded the last time of taking dabigatran according to the patient. The present protocol was examined and approved by the Ethical Review Board in Tenri Hospital (IRB approval number #568, approval date 21 August 2013), and all participants provided written informed consent before their participation in the study according to the guidelines established in the Declaration of Helsinki. Plasma dabigatran concentrations were measured using the Hemoclot® thrombin inhibitor assay (Hyphen Biomed, France) and aPTT was measured using aPTT-SLA® (Sysmex, Kobe, Japan) as the reagent. The standard median of the aPTT reagent used in the present assessment was 30.75 s.

2.2. Data analyses

Continuous variables were described as mean±standard deviation or median and interquartile range (25th–75th percentile), depending on the normality of the distribution. Comparisons were made with the χ2 test for categorical variables, as appropriate, and with the Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables. Interpretation of the intensity of the relationship between plasma dabigatran concentrations and aPTT was performed using Pearson׳s correlation coefficient method. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. These analyses were performed using Stat Flex (Artech, version 6, Osaka, Japan).

3. Results

3.1. Baseline characteristics

Patients had a mean age of 66.6±10.0 years (range: 35–84) and 66% were men. Analyses were performed based on samples, and there were no significant differences between the baseline characteristics of patients and samples (Table 1). The dosage of dabigatran was 110 mg twice a day in 259 (82%) samples and 150 mg twice a day in 57 (18%) samples. The mean value of creatinine clearance (CLCr) based on the Cockcroft-Gault formula was 75.8±25.4 mL/min, and CLCr<50 mL/min was observed in 40 (13%) samples. No samples were obtained from patients with CLCr<30 mL/min. Prescription of a P-glycoprotein (PGP) inhibitor was observed in 55 (17%) samples: verapamil (n=35), cyclosporine (n=9), diltiazem (n=5), atorvastatin (n=3), and amiodarone (n=3). Patients receiving 110 mg of dabigatran, compared with those receiving 150 mg, had a significantly higher age, lower values of estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and CLCr, lighter weight, and were mostly women. Higher plasma dabigatran concentrations and longer aPTT values were observed in patients taking 150 mg dabigatran compared with patients taking 110 mg; however, this difference was not significant (Table 2).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics.

| Patient | Sample | p Value | Dosage of dabigatran |

p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=149 | n=316 | 110 mg×2 | 150 mg×2 | |||

| n=259 (82%) | n=57 (18%) | |||||

| Elapsed time after oral administration (min) | 203 (130–345) | 169 (115–300) | 0.072 | 160 (112–290) | 200 (120–355) | 0.12 |

| Age (year) | 66.6±10.0 | 67.6±9.4 | 0.40 | 69.1±8.8 | 60.4±8.8 | <0.001 |

| Males, n (%) | 98 (66%) | 202 (64%) | 0.70 | 154 (60%) | 48 (84%) | <0.001 |

| Weight (kg) | 62.7±10.3 | 62.9±10.3 | 0.97 | 61.6±9.5 | 69.1±11.4 | <0.001 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 69.6±16.0 | 67.7±15.6 | 0.19 | 66.9±15.7 | 71.7±14.2 | 0.019 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.82±0.19 | 0.83±0.20 | 0.66 | 0.83±0.21 | 0.84±0.15 | 0.34 |

| Creatinine clearance (mL/min) | 77.8±25.1 | 75.8±25.4 | 0.27 | 72.5±23.7 | 90.9±27.7 | <0.001 |

| Creatinine clearance <50 mL/min, n (%) | 14 (9%) | 40 (13%) | 0.31 | 37 (14%) | 3 (5.3%) | 0.064 |

| P-glycoprotein inhibitor, n (%) | 19 (13%) | 55 (17%) | 0.20 | 49 (19%) | 6 (11%) | 0.13 |

Values are expressed as mean±standard deviation, median and interquartile range, or number (n) and %.

eGFR=Estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Table 2.

Dabigatran concentrations and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) according to the dabigatran dosage.

| Total | Dosage of dabigatran |

p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=316 | 110 mg×2 | 150 mg×2 | ||

| n=259 (82%) | n=57 (18%) | |||

| Plasma concentrations of dabigatran (ng/mL) | 89 (41–165) | 79 (40–150) | 128 (54–183) | 0.09 |

| aPTT (s) | 38.7 (34.4–44.6) | 38.3 (34.6–44.5) | 39.7 (33.4–45.4) | 0.80 |

Values are expressed as median and interquartile range.

3.2. Effect of reduced renal function on dabigatran concentrations

Significantly higher dabigatran concentrations were observed in samples from patients with reduced renal function (CLCr<50 mL/min) compared with those with normal renal function (CLCr≥50 mL/min) (120 [69–219] and 81 [40–152] ng/mL, respectively, p=0.009) (Table 3). aPTT values appeared to be elongated in patients with reduced renal function compared with those with normal renal function but the difference was not significant.

Table 3.

Dabigatran concentrations and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) according to renal function.

| Total | Creatinine clearance |

p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=316 | ≥30–<50 mL/min | ≥50 mL/min | ||

| n=40 (13%) | n=276 (87%) | |||

| Dose of dabigatran, 150 mg×2/day, n (%) | 57 (18%) | 3 (7.5%) | 54 (20%) | 0.064 |

| Elapsed time after oral administration (min) | 169 (115–300) | 143 (109–266) | 172 (115–306) | 0.35 |

| Plasma concentrations of dabigatran (ng/mL) | 89 (41–165) | 120 (69–219) | 81 (40–152) | 0.009 |

| aPTT (s) | 38.7 (34.4–44.6) | 44.0 (36.2–47.0) | 38.3 (34.3–44.5) | 0.16 |

Values are expressed as median and interquartile range, or number (n) and %.

3.3. Elapsed time after oral administration of dabigatran

The median elapsed time after oral administration of dabigatran to blood sampling was 169 min (115–300 min), and in 87% of the samples, this time ranged from 0 to 240 min. In 286 (91%) samples, dabigatran was administered to patients between 5:00 am and 9:00 am. Samples from patients who were administered dabigatran during this time period, were classified into eight groups according to elapsed time from administration, ranging from 0 to 6 h (groups 1–7) and after 7 h (group 8). Further analyses and comparisons were performed among these eight groups. There was no significant difference dosage of dabigatran among the eight groups.

3.4. Distribution of dabigatran concentrations and aPTT

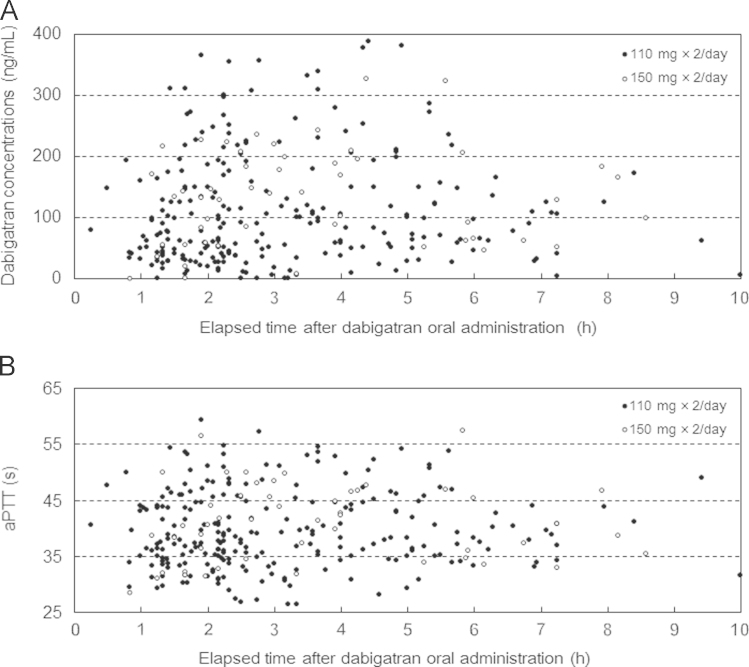

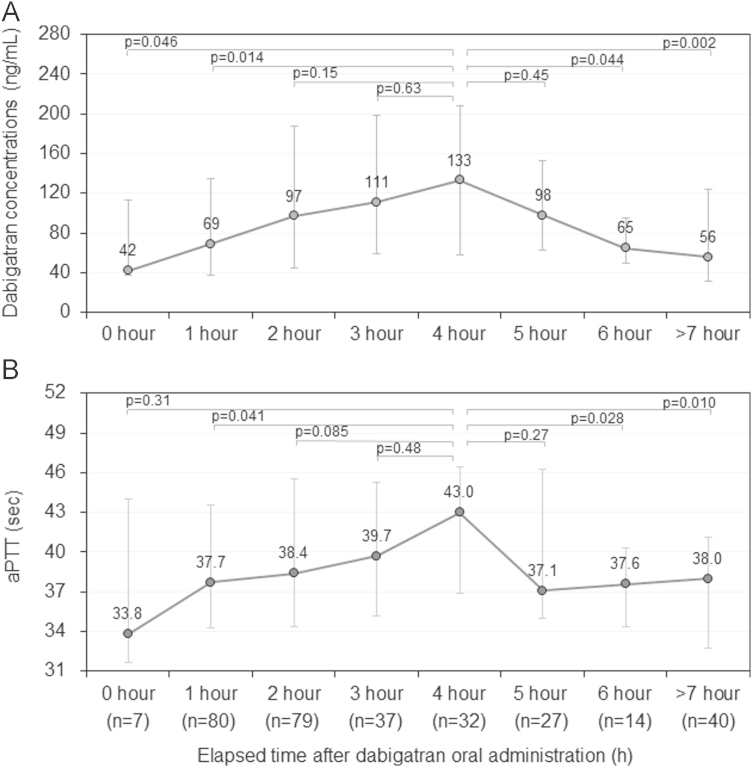

The median dabigatran concentration was 89 ng/mL (41–165 ng/mL), and 54 (17%) samples had dabigatran concentrations of 200 ng/mL or higher (Table 2 and Fig. 1A). When the median dabigatran concentration for each of the eight groups was compared, the 4-h range group showed the highest value of 133 ng/mL, followed by 111 ng/mL in the 3-h range group, and 98 ng/mL in the 5-h range group (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 1.

(A) Distribution of plasma dabigatran concentrations and elapsed time after dabigatran oral administration. (B) Distribution of activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) and elapsed time after dabigatran oral administration.

Fig. 2.

(A) Distribution of plasma dabigatran concentrations according to elapsed time after dabigatran oral administration (hour range). (B) Distribution of activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) according to elapsed time after dabigatran oral administration (hour range). Values are expressed as median and interquartile range.

The median aPTT was 38.7 s (34.4–44.7 s) and none of the samples showed an aPTT of ≥60 s (Table 2 and Fig. 1B). When the median values of aPTT were compared among the eight groups, the 4-h range group showed the highest value of 43.0 s, followed by 39.7 s in the 3-h range group, and 38.4 s in the 2-h range group (Fig. 2B).

3.5. Relationship between plasma dabigatran concentrations and aPTT

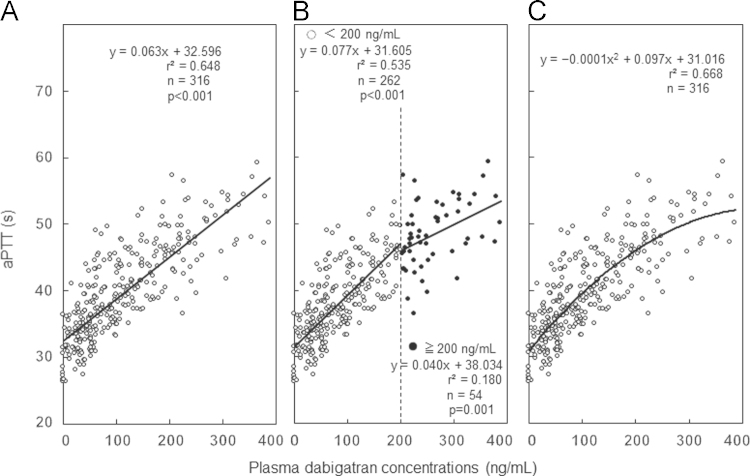

There was a significant correlation between dabigatran concentration and aPTT (y=0.063x+32.596, r2=0.648, p<0.001) (Fig. 3A). Additional analysis was performed for two levels of plasma dabigatran concentrations: <200 ng/mL and ≥200 ng/mL. The regression line was y=0.077x+31.605 (r2=0.535) for <200 ng/mL (n=262) and showed a significant linear relationship (p<0.001). For ≥200 ng/mL (n=54), the regression line was y=0.040x+38.034 (r2=0.180), which again showed a linear relationship (p=0.001), but the slope was diminished and the correlation value was lower compared with that for <200 ng/mL (Fig. 3B). Therefore, we evaluated this relationship by quadratic curve: y=−0.0001x2+0.097x+31.016. A better correlation value of r2=0.668 was observed with this regression curve compared with the regression line (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Relationship between plasma dabigatran concentrations and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT). (A) Regression line of dabigatran concentrations. (B) Regression line at two levels of plasma dabigatran concentrations: <200 ng/mL and ≥200 ng/mL. (C) Regression curve between plasma dabigatran concentrations and aPTT.

4. Discussion

4.1. Major findings

The main findings of this study are as follows: there was a significant correlation between the concentration of dabigatran and aPTT; peak dabigatran concentrations and the longest aPTT values were observed in the 4-h post dabigatran administration range; and significantly higher dabigatran concentrations were observed in patients with reduced renal function compared with those with normal renal function.

4.2. Measurement of dabigatran concentrations

Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) is considered the most precise method for measuring plasma dabigatran concentrations [1]; however, LC–MS/MS requires high expenditure and extensive procedures for sample pretreatment [1]. The LC–MS/MS system and coagulation assays were previously evaluated [2,8,15,16], and a good correlation was observed between the clotting time measured by the Hemoclot® direct thrombin inhibitor assay and plasma dabigatran concentrations measured using the LC–MS/MS system [15]. Therefore, the measurements obtained by the Hemoclot® direct thrombin inhibitor assay can be considered the estimated plasma concentration of dabigatran.

Our study indicates that measurement of plasma concentrations with Hemoclot® is ideal for monitoring the risk of bleeding due to excess accumulation of dabigatran. However, the expense of Hemoclot® direct thrombin inhibitor assay is not reimbursed by the Japanese social insurance system. On the other hand, monitoring with aPTT could be performed in any hospital in Japan and therefore it is important to clarify the relationship between dabigatran concentration and aPTT prolongation in a clinical setting. Our data showed a significant relationship between serum dabigatran concentration and aPTT, thereby supporting the use of aPTT as a surrogate test for dabigatran concentration.

4.3. Reduced renal function

We confirmed that higher dabigatran concentrations were observed in patients with reduced renal function (CLCr, 30–50 mL/min). Stangier et al. reported that, after oral administration of a single dose of 150 mg dabigatran, the area under the curve values for the plasma concentration-time were 1.5-, 3.2-, and 6.3-fold higher in people with a CLCr of 50–80 mL/min, 30–50 mL/min, and <30 mL/min, respectively, compared with values in healthy people [17]. Therefore, dabigatran is regarded as a contraindication for patients with CLCr<30 mL/min. However, there are no specific recommendations to reduce the dose of dabigatran in patients with reduced renal function and therefore, a reliable method for monitoring dabigatran use is greatly anticipated to ensure its safe use in patients with reduced renal function.

4.4. Timing of peak dabigatran concentrations and peak aPTT after administration

Early phase studies of dabigatran have shown that dabigatran concentrations rapidly increase and reach a peak value within 1.5–3 h after oral administration [1–4]. The timing of peak dabigatran concentration in the present study was approximately 2 h later compared with previous studies in which blood sampling was performed in healthy men with an empty stomach [1,18]. A possible reason for the difference observed between the studies could be a delay in dabigatran absorption in our study since most of the patients administered dabigatran after breakfast. Our result is consistent with that of Stangier׳s study, which demonstrated that plasma dabigatran concentrations reached a peak value 2 h after oral administration when dabigatran was administered on an empty stomach, but reached a peak value 2 h later, when it was administered after a meal [18].

4.5. Correlation between plasma dabigatran concentrations and aPTT

The sensitivity of dabigatran depends on the type of aPTT reagent [9,19–21], which could be a possible explanation for the differences observed between studies. The regression line between the plasma concentration of dabigatran and aPTT in this study for all samples, showed a significant linear relationship with a moderate correlation. When the concentration of dabigatran was <200 ng/mL, plasma dabigatran concentrations and aPTT showed a moderate correlation (r2=0.535), which suggested that dabigatran concentrations are able to be estimated by aPTT. However, when plasma dabigatran concentrations exceeded 200 ng/mL, the slope was diminished and the correlation value decreased to r2=0.180, suggesting that aPTT does not prolong in proportion to the plasma dabigatran concentration. When aPTT exceeds 45.2 s, corresponding to a dabigatran concentration of 200 ng/mL, it is plausible that dabigatran concentrations could be higher than expected. Plasma concentrations of dabigatran exceeding 200 ng/mL, as measured by Hemoclot®, have been reported to be related to hemorrhagic events [5], and this relationship has been described in the European Heart Rhythm Association Practical Guide on the use of new oral anticoagulants [22]. These findings suggested that it was better to estimate the plasma concentration of dabigatran from aPTT on the regression quadratic curve rather than the regression line, especially for high plasma concentrations of dabigatran.

4.6. Clinical implications

To monitor the risk of bleeding due to excessive accumulation of dabigatran, measurement of the trough dabigatran value immediately before its administration is reasonable. However, it is also reasonable to monitor peak dabigatran concentration for a period after breakfast, since the half-life of dabigatran concentration is as short as 12 h and dabigatran is administered after breakfast by many patients. Our study clarified the pharmacokinetics and the timing of peak dabigatran concentration and peak aPTT in daily clinical practice.

4.7. Study limitations

First, our database consisted of a cohort from a single hospital, and therefore, the results should be carefully interpreted since the patients׳ backgrounds, the criteria for use, and patient management in one hospital might be different from that in other institutions. The second limitation of the study was the absence of hemorrhagic events, which meant that we were not able to analyze how high dabigatran concentrations and related high aPTT predispose the risk of hemorrhagic events.

5. Conclusions

There was a significant correlation between plasma dabigatran concentrations and aPTT. Plasma dabigatran concentrations and aPTT reached a peak in the 4-h post administration range. Considering the pharmacokinetics of dabigatran, aPTT could be used as a parameter in risk screening for excess effects in Japanese patients who are taking dabigatran. Further studies are required to establish an ideal method for monitoring the safe use of dabigatran.

Funding

This research received no grants from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to the outstanding efforts of the laboratory medical technologists in Tenri Hospital for data collection and blood sampling.

References

- 1.Stangier J, Rathgen K, Stähle H. The pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and tolerability of dabigatran etexilate, a new oral direct thrombin inhibitor, in healthy male subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;64:292–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2007.02899.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Ryn J, Stangier J, Haertter S. Dabigatran etexilate – a novel, reversible, oral direct thrombin inhibitor: interpretation of coagulation assays and reversal of anticoagulant activity. Thromb Haemost. 2010;103:1116–1117. doi: 10.1160/TH09-11-0758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stangier J, Clemens A. Pharmacology, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of dabigatran etexilate, an oral direct thrombin inhibitor. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2009;15:9S–16S. doi: 10.1177/1076029609343004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hori M, Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD. Efficacy and safety of dabigatran vs. warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation, sub-analysis in Japanese population in RE-LY trial. Circ J. 2011;75:800–805. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-11-0191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huisman MV, Lip GY, Diener HC. Dabigatran etexilate for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation: resolving uncertainties in routine practice. Thromb Haemost. 2012;107:838–847. doi: 10.1160/TH11-10-0718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pengo V, Crippa L, Falanga A. Questions and answers on the use of dabigatran and perspectives on the use of other new oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation. A consensus document of the Italian Federation of Thrombosis Centers. Thromb Haemost. 2011;106:868–876. doi: 10.1160/TH11-05-0358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamashita T, Horioka S, Matsuhashi N, et al. Relation between frequency of activated partial prothrombin time measurements and clinical outcomes in patients after initiation of dabigatran: a two-center cooperative study. J Arrhythmia [in press]. 〈10.1016/j.joa.2014.05.001〉 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Antovic JP, Skeppholm M, Eintrei J. Evaluation of coagulation assays versus LC–MS/MS for determinations of dabigatran concentrations in plasma. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;69:1875–1881. doi: 10.1007/s00228-013-1550-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hapgood G, Butler J, Malan E. The effect of dabigatran on the activated partial thromboplastin time and thrombin time as determined by the Hemoclot thrombin inhibitor assay in patient plasma samples. Thromb Haemost. 2013;110:308–315. doi: 10.1160/TH13-04-0301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suzuki S, Otsuka T, Sagara K. Dabigatran in clinical practice for atrial fibrillation with special reference to activated partial thromboplastin time. Circ J. 2012;76:755–757. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-11-1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suzuki S, Sagara K, Otsuka T. Blue letter effects: changes in physicians׳ attitudes toward dabigatran after a safety advisory in a specialized hospital for cardiovascular care in Japan. J Cardiol. 2013;62:366–373. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2013.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawabata M, Yokoyama Y, Sasano T. Bleeding events and activated partial thromboplastin time with dabigatran in clinical practice. J Cardiol. 2013;62:121–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Härtter S, Yamamura N, Stangier J. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in Japanese and Caucasian subjects after oral administration of dabigatran etexilate. Thromb Haemost. 2012;107:260–269. doi: 10.1160/TH11-08-0551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamashita T., Watanabe E., Ikeda T. Observational study of the effects of dabigatran on gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. J Arrhythmia. 2014;30:478–484. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stangier J, Feuring M. Using the HEMOCLOT direct thrombin inhibitor assay to determine plasma concentrations of dabigatran. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2012;23:138–143. doi: 10.1097/MBC.0b013e32834f1b0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Douxfils J, Dogné JM, Mullier F. Comparison of calibrated dilute thrombin time and aPTT tests with LC–MS/MS for the therapeutic monitoring of patients treated with dabigatran etexilate. Thromb Haemost. 2013;110:543–549. doi: 10.1160/TH13-03-0202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stangier J, Rathgen K, Stähle H. Influence of renal impairment on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of oral dabigatran etexilate: an open-label, parallel-group, single-centre study. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2010;49:259–268. doi: 10.2165/11318170-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stangier J. Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the oral direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran etexilate. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2008;47:285–295. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200847050-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Douxfils J, Mullier F, Robert S. Impact of dabigatran on a large panel of routine or specific coagulation assays. Laboratory recommendations for monitoring of dabigatran etexilate. Thromb Haemost. 2012;107:985–997. doi: 10.1160/TH11-11-0804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lindahl TL, Baghaei F, Blixter IF. Effects of the oral, direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran on five common coagulation assays. Thromb Haemost. 2011;105:371–378. doi: 10.1160/TH10-06-0342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Helin TA, Pakkanen A, Lassila R. Laboratory assessment of novel oral anticoagulants: method suitability and variability between coagulation laboratories. Clin Chem. 2013;59:807–814. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2012.198788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heidbuchel H, Verhamme P, Alings M. European Heart Rhythm Association Practical Guide on the use of new oral anticoagulants in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. Europace. 2013;15:625–651. doi: 10.1093/europace/eut083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]