Abstract

Background: Acupuncture at specific acupoints has experimentally been found to reduce chronically elevated blood pressure.

Objective: To examine effectiveness of electroacupuncture (EA) at select acupoints to reduce systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressures (DBP) in hypertensive patients.

Design: Two-arm parallel study.

Patients: Sixty-five hypertensive patients not receiving medication were assigned randomly to one of the two acupuncture intervention (33 versus 32 patients).

Intervention: Patients were assessed with 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. They were treated with 30-minutes of EA at PC 5-6+ST 36-37 or LI 6-7+GB 37-39 once weekly for 8 weeks. Four acupuncturists provided single-blinded treatment.

Main outcome measures: Primary outcomes measuring effectiveness of EA were peak and average SBP and DBP. Secondary outcomes examined underlying mechanisms of acupuncture with plasma norepinephrine, renin, and aldosterone before and after 8 weeks of treatment. Outcomes were obtained by double-blinded evaluation.

Results: After 8 weeks, 33 patients treated with EA at PC 5-6+ST 36-37 had decreased peak and average SBP and DBP, compared with 32 patients treated with EA at LI 6-7+GB 37-39 control acupoints. Changes in blood pressures significantly differed between the two patient groups. In 14 patients, a long-lasting blood pressure–lowering acupuncture effect was observed for an additional 4 weeks of EA at PC 5-6+ST 36-37. After treatment, the plasma concentration of norepinephrine, which was initially elevated, was decreased by 41%; likewise, renin was decreased by 67% and aldosterone by 22%.

Conclusions: EA at select acupoints reduces blood pressure. Sympathetic and renin-aldosterone systems were likely related to the long-lasting EA actions.

Key Words: : Neiguan-Jianshi and Zusanli-Shangjuxu, Pianli-Wenliu and Guanming-Xuanzhong, Point Specificity

Introduction

Hypertension is one of the most common clinical disorders in the world. Approximately 1 billion individuals worldwide are affected by hypertension.1 In the United States, nearly a third of the adult population is hypertensive, and the prevalence of hypertension increases with age. The lifetime risk for hypertension in middle-aged adults approaches 90% in the United States.2 Many patients (46%) with known cardiovascular disease are hypertensive, and 72% of them have experienced a stroke that accounted for approximately 15% of the 2.4 million deaths in 2009.3 In 2008, the estimated direct and indirect cost of hypertension was $69.9 billion. It has been suggested that individuals with blood pressure (BP) levels greater than 120/80 mmHg (systolic/diastolic blood pressure [SBP/DBP]) consider complementary methods to help decrease blood pressure, when clinically appropriate.4

To search for a therapy that offers minimal adverse effects, we need targeted approaches directed at the underlying mechanisms of hypertension. Although Western medical science has developed many treatment strategies to control hypertension, antihypertensive medical therapies are not perfect and are often associated with adverse effects. In this regard, drug therapy indiscriminately blocks many receptors, leading to unwanted responses,5–7 including serious injuries associated with falls in older patients.8 Therefore, it is imperative to identify more effective approaches to achieve optimal control of hypertension.

Adverse effects of currently available therapy to control hypertension have sparked a growing interest in alternative medical treatments, such as acupuncture.9,10 However, despite the increasing worldwide interest in complementary medical therapy, including acupuncture,10 many Western physicians are reluctant to recommend this medical modality because its efficacy in the treatment of hypertension remains controversial and the physiologic mechanisms that account for its hypotensive actions are not clear.4,9

Several studies have evaluated the BP-lowering actions of acupuncture in patients with hypertension, but their findings are inconclusive.4 Some researchers have suggested that acupuncture can decrease elevated blood pressure,11–13 while others have concluded that there is little or no effect.14,15 Prior acupuncture studies had weaknesses. For example, the sample sizes were small and were not calculated a priori, randomization has been rare, and many studies lacked adequate control groups using acupoints that can serve as effective controls.11,16 The follow-up period after treatment generally has been nonexistent or inadequate.

Some studies relied on Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) theory involving meridian and Qi hypotheses to apply stimulation rather than applying modern scientific principles to guide the acupuncture therapy.5,17 The practice of TCM depends on history and physical examination to classify patients and to guide the selection of acupoints, ultimately leading to the selection of different acupoints for individual patients.18 Hence, standardized approaches to select acupoints for stimulation are not used in TCM-based studies. While acupuncturists using TCM usually stimulate several acupoints, some of these acupoints have minimal input to cardiovascular centers of the brain.14,19–21 Furthermore, patients in many studies were receiving antihypertensive medications.13,22,23 While this trial design addresses the added value of acupuncture, it can lead to variable results if patients change medication dosing during the clinical trial. Additionally, most studies relied on intermittent cuff BP measurements rather than ambulatory monitoring. Intermittent cuff measurements can introduce observer bias24 and do not reflect BP throughout the day. Thus, rigorous, properly designed clinical trials to evaluate the influence of acupuncture in hypertension are required.

Mechanistic laboratory studies have demonstrated that acupuncture modulates neurohumoral regulatory systems and hence cardiovascular function.25–28 We have demonstrated in a series of experimental investigations the mechanisms and actions of acupuncture in models of elevated BP associated with reflex sympathoexcitation.29 These studies suggest that bilateral electroacupuncture (EA) at select acupoints inhibits sympathetically mediated demand-induced myocardial ischemia by lowering blood pressure to decrease oxygen demand.29 Using a point-specific approach to acupoint stimulation, we further demonstrated that acupuncture at Neiguan-Jianshi and Zusanli-Shangjuxu (PC 5-6 and ST 36-37), in contrast to EA at Pianli-Wenliu and Guanming-Xuanzhong (LI 6-7 and GB 37-39), modulates elevated BP.30,31 We also have shown that low-frequency, low-intensity EA (intensity just below motor threshold) causes the largest decreases in reflex-induced hypertension.29,30,32 Repeated EA (PC 5-6+ST 36-37) prolongs the lowering of blood pressure.33,34 These experimental findings provided guidance in formulating the current study, which was designed to test the overall hypothesis that weekly EA at PC 5-6+ST 36-37 (active) but not LI 6-7+GB 37-39 (control) acupoints for 8 weeks decreases BP for a prolonged period in patients with mild to moderate hypertension. We used 24-hour ambulatory BP measurements to monitor EA inhibition of peak and average SBP and DBP and to identify high and low responders to EA. We also prospectively investigated the subhypothesis that EA application to active points for 8 weeks reduces peak and average SBP in high responders through reduction in sympathetic activity and therefore ultimately circulating norepinephrine, renin, and aldosterone.

Methods

Trial design

We enrolled 98 patients with mild to moderate hypertension, defined as SBP/DBP ≥140–180/90–99 mmHg.35 All patients had an SBP or DBP within the hypertensive range. The power calculation was based on at least 32 patients per group to achieve 76% power and to detect a difference in BP reduction of 6.8 mmHg after two different sets of acupuncture treatments. Figure 1 displays a chart of the patient flow. This prospective study used guidelines shown in Joint National Committee reports 6 and 735,36 and Revised Standards for Reporting Interventions in Clinical Trials of Acupuncture.37

FIG. 1.

Flow diagram of patients screened, enrolled, and assigned to different protocols. BP, blood pressure; CV, cardiovascular; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; EA, electroacupuncture; HTN, hypertension; IRB, institutional review board; UCI, University of California, Irvine.

The clinical coordinator enrolled the participants. Through use of a computer, patients were coded and randomly assigned to acupuncture therapy at one of the two sets of acupoints. Patients were blinded in that they were told they would receive EA treatment at one of two sets of acupoints to determine whether either set would lower their BP. The California-licensed acupuncturists providing EA treatment were aware of which acupoints were stimulated but did not communicate any expectations to the patient. Assessors who analyzed the outcomes (BP and plasma hormone data) were blinded to the acupoints stimulated.

Inclusion Criteria

The human subjects institutional review board at the University of California, Irvine (UCI), approved the treatment protocols. Each patient provided informed written consent. All patients were referred by their primary care physicians. They had no cardiovascular disease except for elevated BP and were not taking antihypertensive medications for at least 72 hours before the study. By using ambulatory monitoring (Spacelabs Healthcare, Snoqualmie, WA), we recorded 24-hour SBP, mean BP, and diastolic BP and heart rate every 30 minutes during daytime and every hour at night. A medical history, physical examination, electrocardiogram, laboratory evaluation, most recent stress test, and cardiac echocardiogram, if applicable, were obtained for each patient. These data confirmed the absence of any cardiovascular disease other than hypertension.

If average BP exceeded 180 mmHg systolic or 110 mmHg diastolic, patients were instructed to resume their antihypertensive medications. No patients fell into this category. Female nonpregnant hypertensive patients were asked to conform to a medically acceptable method of birth control. All procedures were conducted at the Institute of Clinical Translational Sciences (ICTS) in UCI Medical Center and at the UCI campus. Patients were instructed to report any complications, including bleeding, bruising, pain, infection, and any other adverse effects. No complications or adverse effects were noted or reported.

Electroacupuncture

Disposable, sterile stainless steel acupuncture needles were inserted bilaterally into one of two sets of acupoints, including Neiguan, Jianshi (pericardial meridian, PC 6 and 5 points, on the palmar side of both arms, approximately 4 and 6 cm [2 and 3 cun] above the crease of the wrist respectively, between the tendons of the long palmar muscle and radial flexor muscle of the wrist, overlying the median nerve) and Zusanli, Shangjuxi (stomach meridian, ST 36 and 37, on the anterolateral side of the leg, approximately 6 and 12 cm [3 and 6 cun] below the knee and approximately 2 cm [1 cun] lateral to the anterior crest of the tibia, overlying the deep peroneal nerve) or alternatively Guangming, Xuanzhong (gallbladder meridian, GB 37 and 39, positioned approximately 10 and 6 cm [5 and 3 cun] above the lateral ankle, respectively, overlying the superficial peroneal nerve) and Pianli and Wenliu (large intestine meridian, LI 6 and 7, located approximately 6 and 10 cm [3 and 5 cun] above the wrist overlying the superficial radial nerve).38–40 One cun was approximately 2 cm.41 For safety, pairs of ipsilateral acupoints on each side were stimulated during EA so that current flowed between the two adjacent electrodes rather than through the body to the contralateral extremity.42 These two sets of acupoints were stimulated bilaterally (eight needles in total for each patient) to evaluate the effect of EA and specificity of acupoints with respect to lowering BP. Needles were inserted and stimulated for 30 minutes20,21,42 by using currents that were just below motor threshold (1–2 mA and 2–5 Hz). Patients typically described a paresthesia (called De Qi in TCM) during stimulation of acupoints.42

Protocols

Patients entered into the study were treated once weekly with EA at either set of acupoints for 8 weeks. Patients were treated in the supine position. Cuff BP was recorded before and after the 30 minutes of weekly treatment. Ambulatory pressures were measured 24 hours before and after EA treatment. Peak and average SBP, DBP, and mean BP were recorded. Peak BP represented the single highest 24-hour recorded pressure. We evaluated pressures surrounding peak pressure to avoid isolated artifacts. After the initial course of 8 weeks of EA at PC 5-6+ST3 6-37 or LI 6-7+GB 37-39, subgroups of patients were selected for their willingness to continue in the follow-up or crossover study. Thus, after the initial course of 8 weeks of EA treatment, BP in a subset of 21 patients was recorded monthly in the absence of EA for 2 additional months of follow-up to evaluate the long-lasting effect of acupuncture. After EA treatment, 6 patients declined to continue with the follow-up despite encouragement. The crossover protocol was applied sequentially to evaluate the BP responses to randomized stimulation of first one set then the second set of acupoints. After the first 8-week period of treatment, at least a 2-week washout period was implemented. Thereafter, an additional 8 weeks of therapy was provided for the other set of points. Thus, 17 patients received stimulation sequentially at both sets of points.

Laboratory Procedures

Blood was drawn at the onset of the study and within 1 month at end of 8 weeks of EA in a subgroup of patients. Venous blood samples were collected aseptically in EDTA, placed on ice, and immediately spun at 1500 g for 10 minutes. The plasma was then frozen at −80°C until assay.

Renin activity, aldosterone, norepinephrine, and epinephrine were assayed with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay techniques as described in the commercially available kits. Briefly, renin activity, aldosterone, and catecholamines were assayed in duplicate from both time points for each patient. Plasma was extracted and processed as specified before treatment of the microplates. The absorbance was measured spectrophotometrically at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Spetramax Pro 384; Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) with background correction at 600 nm. Concentrations were determined with a standard curve generated by regression curve fit using Softmax Pro (Molecular Devices) software. Kits were acquired from Eagle Biosciences (Nashua, NH; catalog number BCT31-K02) to assay epinephrine and norepinephrine. Plasma renin activity was measured by using a kit from ALPCO Diagnostics (Salem, NH; catalog number 11-RENHU-E02). Plasma aldosterone was measured with a kit from Labor Diagnostika Nord (catalog number MSE-5200; distributed in the United States by Rocky Mountain Diagnostics, Inc., Colorado Springs, CO).

Reinforcement Study

In a preliminary post hoc study, we further evaluated in a group of 7 hypertensive patients the possibility of a long-lasting EA-lowering effect on BP. The EA (PC 5-6+ST 36-37)-responsive patients received 6 additional monthly treatments after the 8-week course (total of 8 months).

Statistical Analyses

Demographic information is presented as mean±standard error of the mean. Ambulatory monitoring allowed identification of peak BPs throughout the 24-hour period. BP before or after the peak pressure was assessed and was determined to be in the same range, to rule out isolated artifacts. BPs were averaged throughout the day and night. The actions of EA on BP and heart rate at different time points were compared with one- and two-way repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) to access these primary outcomes. The Student–Newman–Keuls multiple-comparisons procedure was used to evaluate pairwise differences between 2, 4, 6, or 8 weeks of EA and to compare with control values before the onset of treatment.

A two-way repeated-measures ANOVA was used to compare changes in BP from baseline to 2, 4, 6, or 8 weeks between groups of patients treated with EA at control LI 6-7+GB 37-39 and active PC 5-6+ST 36-37 acupoints. A subgroup of patients included in the 2-month follow-up after the initial 8 weeks of weekly acupuncture were evaluated by the one-way repeated-measures ANOVA using intention-to-treat because 2 patients were unavailable for the first or second month visit after acupuncture. Plasma hormone changes after 8-week acupuncture were evaluated with the Student–Newman–Keuls comparison procedure in another subgroup of patients to analyze the secondary outcomes. Statistically significant differences were determined as P≤0.05 (SigmaPlot II, San Jose, CA).

Results

Patient Characteristics

Ninety-eight patients were enrolled and 65 patients completed the study. Thirty-three patients who did not meet the BP criteria were excluded. The patients' average baseline 24-hour SBP, mean BP, and DBP were 123–169, 71–112, and 76–143 mmHg, respectively. Either SBP or DBP or both had to be in the hypertensive range (see Methods section) in order for the patient to be included in the study. The 65 patients were randomly allocated to the treatment: PC 5-6+ST 36-37 or LI 6-7+GB 37-39. Average 24-hour mean BP did not differ among the groups of patients before treatment with EA at PC 5-6+ST 36-37 and LI 6-7+GB 37-39 (P>0.05) (Table 1). The average ages of the hypertensive patients treated with active and control sets of acupoints were 58±2 and 54±2 years and included 30 men and 35 women. Average body mass indexes were 26±1 and 25±1 in the two groups treated with EA at PC 5-6+ST 36-37 and LI 6-7+GB 37-39 (P>0.05) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Treatment Group | PC 5-6+ST 36-37 (active) | LI 6-7+GB 37-39 (control) | Total | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (range) (yr) | 58±2 (38–75) | 54±2 (38–71) | >0.05 | |

| Sex (n) | ||||

| Male | 16 | 14 | 30 | |

| Female | 17 | 18 | 35 | |

| Total | 33 | 32 | 65 | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 26±1 (22–42) | 25±1 (22–30) | >0.05 | |

| Baseline mean arterial pressure (mmHg) | 130±2 | 126±3 | >0.05 | |

| 24-hr peak | ||||

| 24-hr average | 107±2 | 105±4 | >0.05 | |

Values expressed with a plus/minus sign are the mean±standard error of the mean. Values expressed in parentheses are ranges.

Longitudinal Protocols

EA at PC 5-6+ST 36-37 decreased peak SBP and average SBP, DBP, and mean BP during the 8-week course of therapy. After 4 weeks of EA treatment, peak and average SBP decreased gradually and continuously. Peak SBP was decreased by 8 mmHg, while average SBP was decreased 6 mmHg after 8 weeks (P<0.05) (Fig. 2A). In addition, EA decreased both MBP and DBP, while heart rate was not influenced by 8-week treatment at PC 5-6+ST 36-37 (Fig. 2B–D). EA treatment in 32 patients at LI 6-7+GB 37-39 acupoints did not consistently decrease SBP and DBP or heart rate (Fig. 3). Thus, in contrast to EA treatment at LI 6-7+GB 37-39, SBP, DBP, mean BP, and heart rate were reduced after 8 weeks of EA applied to PC 5-6+ST 36-37 acupoints in hypertensive patients.

FIG. 2.

Blood pressures (BPs) averaged over 24 hours and heart rate in 33 hypertensive patients treated with electroacupuncture (EA) at PC 5-6+ST 36-37 active acupoints for 8 weeks. Systolic (A), diastolic (B), and mean (C) BPs were reduced. EA did not alter heart rate (D). BP was significantly reduced after 4 weeks of treatment. DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HR, heart rate; MBP, mean blood pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure. *Significant difference compared to pre-acupuncture (P<0.05). Bracket indicates standard error.

FIG. 3.

Electroacupuncture (EA) at LI 6-7+GB 37-39 acupoints did not consistently alter blood pressure or heart rate in 32 patients. Systolic (A), diastolic (B) and mean (C) blood pressures and heart rates (D) after 8 weeks of EA applied at LI 6-7+GB 37-39 acupoints were not different from values at onset of study. DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HR, heart rate; MBP, mean blood pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Crossover Protocol

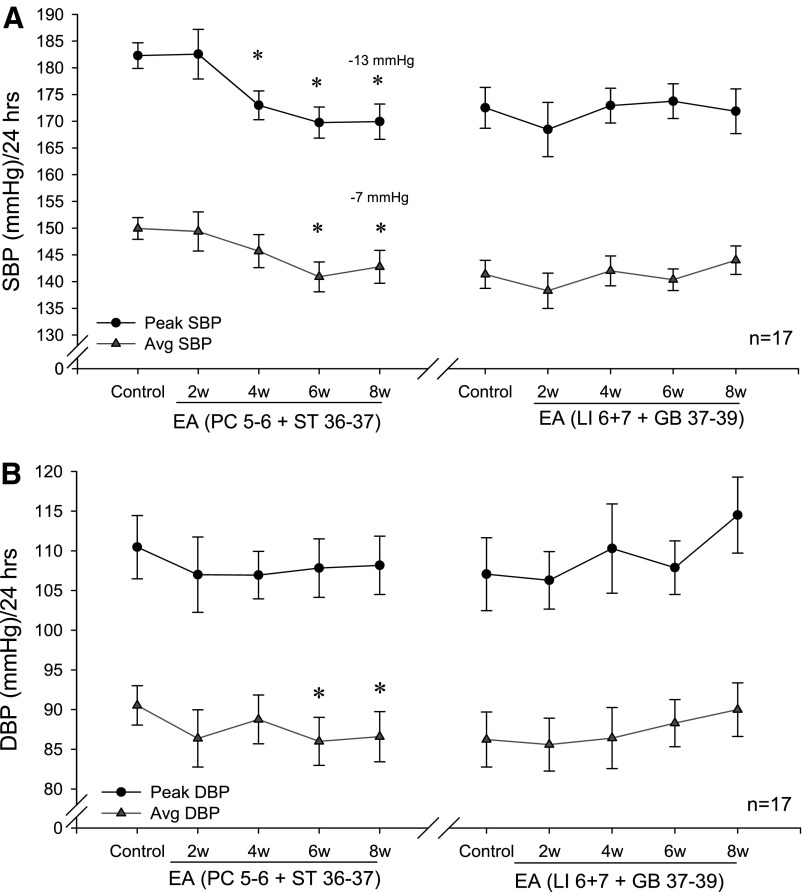

To further evaluate the efficacy of EA, 17 patients were treated sequentially with EA applied at PC 5-6+ST 36-37 for 8 weeks or LI 6-7+GB 37-39 for 8 weeks, rested for at least 2 weeks, then crossed over for 8 additional weeks of therapy to the other set of acupoints. Stimulation of PC 5-6+ST 36-37 decreased peak and average SBP by 13 and 7 mmHg, respectively, while stimulation at the LI 6-7+GB 37-39 acupoints did not alter BP (Fig. 4A). After 8-week EA treatment at active acupoints, DBP decreased by 4 mmHg in contrast to treatment at control sites (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

Effects of electroacupuncture (EA) at PC 5-6+ST 36-37 and LI 6-7+GB 37-39 were evaluated in a crossover study. Seventeen patients were randomly treated with EA at PC 5-6+ST 36-37 or LI 6-7+GB 37-39 acupoints for 8 weeks, followed by a recovery period of 2 weeks. Patients then were treated for 8 weeks by applying EA to the other sets of acupoints. The patients respond differentially to stimulation of the two sets of acupoints, confirming point-specific actions of EA on cardiovascular function. (A) Systolic blood pressure (SBP). (B) Diastolic blood pressure (DBP).

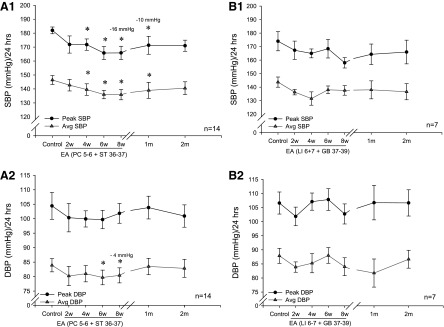

Follow-up Protocol

To evaluate the prolonged action of EA, we evaluated in 21 hypertensive patients the effect of EA for an additional 2 months after the 8-week treatment. In contrast to EA treatment applied to control acupoints, 8 weeks of treatment at PC 5-6+ST 36-37 decreased both peak and average SBP for another month after EA therapy. Average SBP was decreased by 6 mmHg at 8 weeks and 5 mmHg 1 month after therapy (Fig. 5A1). The decrease in average DBP lasted for 2 weeks during EA treatment at active acupoints (Fig. 5A2). Treatment at control sites did not decrease SBP or DBP (Fig. 5B1 and 5B2). Thus, the effectiveness of acupuncture persisted for a month after the course of EA therapy.

FIG. 5.

Effects of electroacupuncture (EA) were evaluated for 2 months in the follow-up study in 21 patients. Peak and average systolic blood pressure (SBP) was reduced for 1 month after EA (PC 5-6+ST 36-37). Peak and average SBPs were reduced at weeks 6 and 8 (A1). While average DBP was reduced at weeks 6 and 8 (A2) during EA. EA at LI 6-7+GB 37-39 acupoints did not consistently decrease blood pressure (B1 and B2). Eight weeks after termination of EA, blood pressures had returned to pretreatment control levels. DBP, diastolic blood pressure.

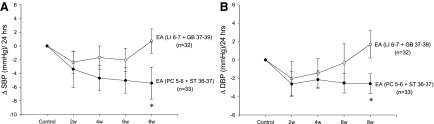

Group Comparison

Post hoc analyses demonstrated a significant difference in reduction of BP after 8 weeks of EA therapy at the active and control acupoints (Fig. 6). The difference in average SBP was 6.8 mmHg between groups by week 8. The change in average DBP was also different after 8 weeks of acupuncture.

FIG. 6.

Group comparison of the changes in systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) at 2, 4, 6, and 8 weeks with electroacupuncture (EA) treatment at active and control acupoints. The changes in SBP were different at week 8 in the two groups of patients with treatment at PC 5-6+ST 36-37 and LI 6-7+GB 36-37 (A). EA treatment at PC 5-6+ST 36-37 acupoints for 8 weeks decreased average DBP compared with control treatment (B).

High and Low Responders to Acupuncture at PC 5-6+ST 36-37

Group analysis comparing responses to active and control acupoint stimulation demonstrated a difference of 6 and 4 mmHg in SBP and DBP after 8 weeks of EA. Therefore, patients responding to EA treatment at active acupoints with a change of ≥6 mmHg SBP or ≥4 mmHg DBP were labeled as high responders. Peak and average SBPs in the high responders group were reduced by 14±3 mmHg and 9±3 mmHg in 22 of 33 (70%) patients. Average DBP in this subgroup of patients was reduced by 4±1 mmHg.

Hormone Responses

EA did not affect plasma epinephrine (40±6 to 38±8 ng/mL; P>0.05) in 25 patients. Plasma norepinephrine in the high responders was significantly greater than that in the low responders before EA treatment. After 8 weeks of EA treatment, norepinephrine decreased from 398±32 to 234±22 ng/mL in 13 high responders (Fig. 7). Norepinephrine in the low responders remained unchanged with EA treatment. Plasma norepinephrine also was unchanged (274±19 to 345±25 ng/mL) in 6 patients subjected to stimulation of LI 6-7+GB 37-39 acupoints.

FIG. 7.

Electroacupuncture (EA) modulation of plasma norepinephrine. Norepinephrine in 25 hypertensive patients was measured before and after 8 weeks of treatment with EA at PC 5-6+ST 36-37. EA did not influence epinephrine. Baseline norepinephrine was higher before EA (**P<0.05) and decreased by 164 ng/mL in patients responsive to EA (*P<0.05). Norepinephrine was not altered by 8 weeks of EA treatment in 12 patients unresponsive to EA.

Plasma renin activity in 13 high responders to EA at PC 5-6+ST 36-37 decreased from 1.8±0.6 to 0.6±0.2 ng/mL per hour after EA treatment. Treatment with EA at PC 5-6+ST 36-37 acupoints did not alter renin activity (0.8±0.4 versus 0.9±0.4 ng/mL per hour) in 9 low responders. Baseline renin activity tended to be lower in the low responders than the high responders (P=0.102) (Fig. 8). Nine other patients treated with EA at LI 6-7+GB 37-39 points for 8 weeks displayed an insignificant change in renin activity (1.5±0.4 versus 2.5±0.8 ng/mL per hour).

FIG. 8.

Electroacupuncture (EA) modulation of plasma renin activity. Renin activity in 13 of 22 hypertensive patients responsive to EA at PC 5-6+ST 36-37 was decreased significantly after 8 weeks of treatment. Nine low responders with lower renin activities before EA were unchanged by 8 weeks of therapy.

Plasma aldosterone was reduced by EA, from 143±10 to 111±11 pg/mL, in 5 EA-responsive patients. Blood samples were insufficient to assay aldosterone in the low responders to EA PC 5-6+ST 36-37 acupoints. Plasma aldosterone was not altered (from 156±43 to 161±46 pg/mL) in 7 patients treated with EA at LI 6-7+GB 37-39 acupoints.

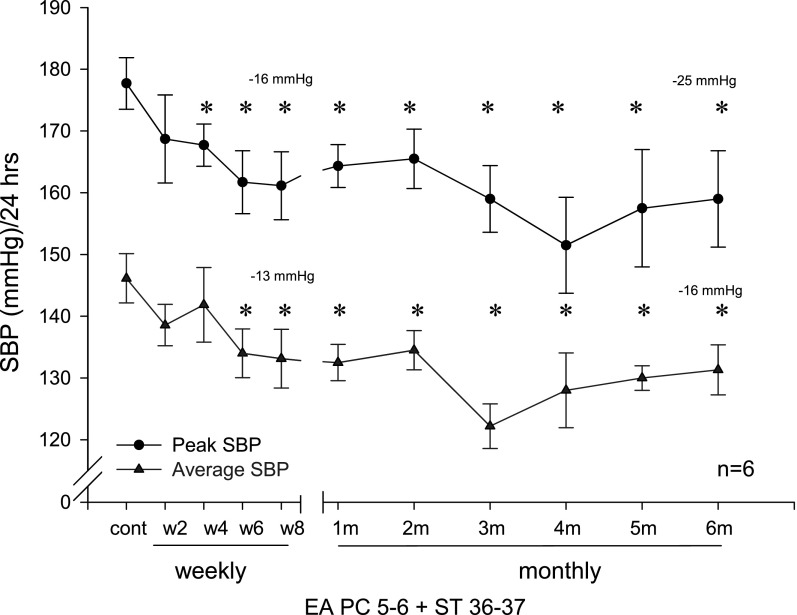

Reinforcement Protocol (PC 5-6+ST 36-37)

The effectiveness of EA persisted in a small group of 7 high responders during a 6-month period when reinforcement therapy was applied once monthly after an initial period of 8 weeks of weekly acupuncture (Fig. 9). Average SBP was reduced by 13 mmHg after 8 weeks of treatment and decreased by 16 mmHg, compared with pretreatment levels, after 6 months of reinforcement EA. Compared with pretreatment values, peak SBP was reduced by 16 mmHg after 8 weeks of treatment and 25 mmHg after 6 months of therapy.

FIG. 9.

Action of electroacupuncture over a 6-month period assessed during monthly reinforcement therapy in a subgroup of 7 hypertensive patients. After 8 weeks of weekly EA, continued monthly EA treatment maintained a low systolic blood pressure (SBP) relative to pre-EA control.

Discussion

The present study investigated acupuncture's BP-lowering effect in patients with mild to moderate hypertension not receiving antihypertensive medication. Weekly acupuncture treatment at PC 5-6+ST 36-37 for 8 weeks decreased both SBP and DBP in hypertensive patients. The BP-lowering effect of acupuncture was slow in onset and long-lasting. Peak and average SBP decreased by 8 and 6 mmHg, respectively, in response to EA applied to PC 5-6+ST 36-37 acupoints in these patients. DBP was reduced by 4 mmHg after 8 weeks of treatment. Weekly stimulation at these points reduced elevated SBP and DBP by 4 weeks of therapy.

To avoid any influence of changes in medication dosage and to observe the BP response to stand-alone therapy, none of the enrolled patients were taking antihypertensive medications. Our observations contrast with those described in a recent review, which concluded that acupuncture is effective only as an adjunct therapy to antihypertensive drug treatment.43,44 In fact, the current study demonstrated improvements in both SBP and DBP with acupuncture in the absence of antihypertensive drugs. A previous study of patients mostly receiving medications reported a decrease in SBP of 6.4 mmHg after 22 treatments over a 6-week period.13 Although the current study applied only about one third of the number of treatments and did so less frequently and over a longer period to patients not receiving antihypertensive medication, the reduction in average SBP appears similar to that seen in other trials. This decrease in peak SBP, as noted below, may reflect differences in application of acupuncture and importantly may reduce the risk for aneurysms, stroke, and other cardiovascular diseases.45,46

Generally, acupuncture treatment at variable points selected by acupuncturists is not standardized but rather is based on TCM symptom diagnosis of hypertensive patients.13,17,44,47 In contrast, we used a standardized set of acupoints that experimentally have been shown to stimulate underlying neural pathways that project to the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus midbrain periaqueductal gray and brain stem cardiovascular centers, which regulate sympathetic outflow. Stimulation at the PC 5-6 and ST 36-37 acupoints is clinically used to treat several cardiovascular conditions, including angina, hypertension, and arrhythmias.28,48–51 Conversely, acupuncture at LI 6-7 and GB 37-39 acupoints, which provide less input to cardiovascular regions in the brain,19,31 has been used to treat noncardiovascular conditions, such as throat pain, headache, and leg pain.20,31,32,52,53 Similar to experimental observations using low-current, low-frequency EA at PC 5-6+ST 36-37,29,30,42 stimulation of these acupoints in hypertensive patients in the present study was substantially more effective in lowering BP than EA at LI 6-7+GB 37-39. Hence, we consider LI 6-7+GB 37-39 acupoints to be point-specific control points.

Approximately 70% of patients were highly responsive to acupuncture, a rate that is similarly efficacious to that noted in previous studies of elevated BP and pain.42,54,55 At the end of 8 weeks of treatment, the efficacy of EA in the high responders was higher than in group overall (average SBP, 11 versus 6 mmHg; peak SBP, 16 versus 8 mmHg). Furthermore, a small subgroup of high responders demonstrated an average SBP decrease of 16 mmHg over a 6-month period of monthly reinforcement treatment. Experimental studies suggest that responsiveness may be related to cholecystokinin-8 in the brain, which antagonizes EA-related opioid actions in brain stem regions that regulate sympathetic outflow during EA.27,56 Experimental studies have shown that EA-associated reductions in reflex elevations in BP are related to decreased sympathetic outflow.31,57,58 The present study also found that, compared with low responders, highly responsive patients began the study with higher baseline plasma levels of norepinephrine and responded to EA with decreases in circulating norepinephrine and renin activity. In this regard, the study demonstrated that elevated norepinephrine and renin in hypertensive patients likely participate in the long-lasting BP changes occurring with a course of acupuncture therapy. Although the sample sizes on plasma hormones are small, the data imply that repeated acupuncture application influences sympathetic outflow and the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system.

A recent meta-analysis noted substantial variability in findings between high-quality acupuncture BP-lowering trials with Jadad scores of 4–5.44 The present study relied heavily on our past experimental observations that evaluated the response to EA in acute reflex-induced hypertension.19,20,59,60 These previous studies guided our selection of sets of standardized acupuncture points (including points that have strong and others that exert negligible effects on elevated BP), as well as the frequency, intensity, and duration of EA stimulation. For example, EA at PC 5-6 and ST 36-37 acupoints have been shown experimentally to decrease elevated BP and sympathetic outflow, including renal nerve activity for prolonged periods.20,57 Mechanisms underlying the long-lasting acupuncture effects includes central neural processing through several neurotransmitter systems acting in long-loop neuronal pathways, extending from the ventral hypothalamus through the midbrain to the medulla, and reverberating circuitry as well as transcriptional regulation by enkephalins following repetitive application.21,33,59–62 The present study demonstrates that EA modulation of peak SBP and average SBP lasted for at least a month after EA and that BP eventually returned to pretreatment values by 2 months. Although EA lowering of SBP and DBP was slow in onset, the reductions were effective in a small subgroup of patients and could be prolonged by monthly reinforcement therapy for at least 6 months.

As such, our observations in hypertensive patients confirm our experimental observations, which have suggested that the effects of EA are slow in onset and long-lasting.31 The delayed onset of the EA-associated hypotensive response may explain why one study of limited duration did not observe EA hypotensive responses.63 In addition, a study that evaluated the duration of post-EA treatment 3 months after termination may have missed the long-lasting (1-month) acupuncture effect.13

In conclusion, our study suggests that EA has a stronger effect on elevations in SBP than on elevations in DBP. The efficacy of EA in treating systolic hypertension may be especially important for patients who are >60 years of age.46 With advancing age, small artery constriction and reduced compliance boost the reflected component of the pulse wave and hence increase SBP, the principal component of BP that is modulated by acupuncture.64,65 Furthermore, EA-associated reductions in SBP decrease the double product and myocardial oxygen consumption29 and are beneficial in reducing demand-induced ischemia.29,42 Spikes in SBP related to stress and the resulting increase in oxygen demand place patients with coronary disease at greater risk for ischemia, as demonstrated by Holter monitoring detection of transient ST-segment changes consistent with ischemia.29,66

Because EA decreases both peak and average SBP, this therapy may decrease the risk for stroke, peripheral artery disease, heart failure, and myocardial infarction in hypertensive patients.46 Even small increases in SBP and DBP increase the risk for aneurysm.46 Thus, although decreases in SBP and DBP were relatively small, in the 4–13 mmHg range, these small reductions by EA potentially are clinically meaningful. It is clear, however, that further studies aimed at acupuncture's potential to reduce cardiovascular risk are warranted.

Acknowledgment

We are grateful to Dr. Liang-Wu Fu, who provided critical comments in the preparation of the manuscript, and to Drs. Frank Zaldivar and Fadia Haddad, for their assistance in plasma hormone measurements. We also would like to thank Hanna Liu for her technical assistance. All studies were conducted in the Institute for Clinical and Translational Sciences at the University of California, Irvine.

This work was funded by Adolph Coors Foundation, DANA Foundation, Susan Samueli Center for Integrative Medicine at the University of California, Irvine, Pioneer Talent of TCM, Shanghai, and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health grant UL1TR000153. The study is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT00932139). This study was published in abstract form: FASEB J 2014;28:686.4.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

CME Quiz Questions

Article Learning Objectives:

After studying this article, participants should have gained an evidence-based understanding for acupuncture's role in hypertension management as well as be able to explain acupuncture's effect on reducing sympathetic outflow and influencing the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system.

Publication date: August 3, 2015

Expiration date: August 31, 2016

Disclosure Information:

Authors have nothing to disclose.

Richard C. Niemtzow, MD, PhD, MPH, Editor-in-Chief, has nothing to disclose.

Members of publisher's editorial staff have nothing to disclose.

Online CME Questions:

-

1. This study demonstrated that:

a) All acupuncture points produce blood pressure lowering.

b) Acupuncture is not capable of lowering blood pressure.

c) Acupuncture at certain acupuncture points (PC 5–6 +ST 36–37) lowers blood pressure, while acupuncture at other points (LI 6–7 + GB 37–39) does not.

d) Acupuncture at certain acupuncture points (LI 6–7 +GB 37–39) lowers blood pressure, while acupuncture at other points (PC 5–6 + ST 36–37) does not.

-

2. In this study:

a) Acupuncture's blood pressure–lowering effect was investigated in patients with mild-to moderate-hypertension not on any anti-hypertensive medications.

b) Acupuncture once weekly for 8 weeks at PC 5–6 + ST 36–37 decreased both systolic and diastolic BP in hypertensive patients.

c) Acupuncture's blood pressure–lowering effect was slow in onset and long-lasting.

d) Acupuncture's blood pressure–lowering effect was investigated in normal patients without hypertension.

e) a, b, and c are all true.

-

3. This study:

a) Demonstrated improvements in both SBP and DBP with acupuncture in the absence of anti-hypertensive drugs.

b) Found that patients highly responsive to acupuncture's blood pressure–lowering effect began the study with higher baseline plasma levels of norepinephrine and responded to electroacupuncture with decreases in circulating norepinephrine and renin activity.

c) Suggests that repeated acupuncture application influences sympathetic outflow and the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system.

d) Found no effect on plasma catecholamines or renin levels.

e) a, b, and c are all true.

-

4. This study:

a) Used an acupuncture protocol of daily acupuncture treatment as is common in China.

b) For safety, pairs of ipsilateral acupoints on each side were stimulated during electroacupuncture, so that current flowed between the two adjacent electrodes rather than through the body to the contralateral extremity.

c) Treated patients once weekly for 8 weeks with electroacupuncture at PC 5–6 + ST 36–37 for 30 minutes with a current just below motor threshold (1–2 mA, 2–5 Hz).

d) b and c are both true.

-

5. The authors suggest that:

a) Acupuncture has no potential role in decreasing cardiovascular risk.

b) Because electroacupuncture decreases both peak and average systolic blood pressure, this therapy may decrease the risk of stroke, peripheral artery disease, heart failure, and heart attack in hypertensive patients.

c) It is clear that further studies aimed at acupuncture's potential to reduce cardiovascular risk are warranted.

d) b and c are both true.

Continuing Medical Education–Journal Based CME Objectives:

Articles in Medical Acupuncture will focus on acupuncture research through controlled studies (comparative effectiveness or randomized trials); provide systematic reviews and meta-analysis of existing systematic reviews of acupuncture research and provide basic education on how to perform various types and styles of acupuncture. Participants in this journal-based CME activity should be able to demonstrate increased understanding of the material specific to the article featured and be able to apply relevant information to clinical practice.

CME Credit

You may earn CME credit by reading the CME-designated article in this issue of Medical Acupuncture and taking the quiz online. A score of 75% is required to receive CME credit. To complete the CME quiz online, go to www.medicalacupuncture.org/cme AAMA members will need to login to their member account. Non-members have opportunity to participate for small fee.

Accreditation: The American Academy of Medical Acupuncture is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME). Designation: The AAMA designates this journal-based CME activity for a maximum of 1 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

References

- 1.Hajjar I, Kotchen JM, Kotchen TA. Hypertension: trends in prevalence, incidence, and control. Annu Rev Public Health. 2006;27:465–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vasan RS, Beiser A, Seshadri S, et al. Residual lifetime risk for developing hypertension in middle-aged women and men: the Framingham Heart study. JAMA. 2002;287(8):1003–1010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Go AS, Bauman MA, Coleman King SM, et al. An effective approach to high blood pressure control: a science advisory from the American Heart Association, the American College of Cardiology, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(12):1230–1238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brook RD, Appel LJ, Rubenfire M, et al. Beyond medications and diet: alternative approaches to lowering blood pressure: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Hypertension. 2013;61:1360–1383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mayer DJ. Acupuncture: an evidence-based review of the clinical literature. Annu Rev Med. 2000;51:49–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.MacPherson H, Thomas K, Walters S, Fitter M. A prospective survey of adverse events and treatment reactions following 34,000 consultations with professional acupuncturists. Acupunct i. 2001;19(2):93–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diao D, Wright JM, Cundiff DK, Gueyffier F. Pharmacotherapy for mild hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;8:CD006742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tinetti ME, Han L, McAvay GJ, et al. Anti-hypertensive medications and cardiovascular events in older adults with multiple chronic conditions. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e90733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eisenberg DM, Davis R, Ettner S, et al. Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990–1997: results of a follow-up national survey. JAMA. 1998;280(18):1569–1575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization (WHO). Traditional Medicine. Report No.: A56/18. Geneva, Switzerland; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang CL. Clinical investigation of acupuncture therapy. Clin J Med. 1956;42:514–517 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tam KC, Yiu HH. The effect of acupuncture on essential hypertension. Am J Chin Med (Gard City N Y). 1975;3(4):369–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flachskampf FA, Gallasch J, Gefeller O, et al. Randomized trial of acupuncture to lower blood pressure. Circulation. 2007;115(24):3121–3129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalish LA, Buczynski B, Connell P, et al. Stop Hypertension with the Acupuncture Research Program (SHARP): clinical trial design and screening results. Control Clin Trials. 2004;25(1):76–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sugioka K, Mao W, Woods J, Mueller RA. An unsuccessful attempt to treat hypertension with acupuncture. Am J Chin Med (Gard City N Y). 1977;5(1):39–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Acupuncture Research Group of An Hui Medical University. Primary observation of 179 hypertensive cases treated with acupuncture. Acta Acad Med An Hui. 1961;4:6–13 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Macklin EA, Wayne PM, Kalish LA, et al. Stop Hypertension with the Acupuncture Research Program (SHARP): results of a randomized, controlled clinical trial. Hypertension. 2006;48(5):838–845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qi L. Recent advances in the study of theraputic effect on hypertension by acupuncture and moxibustion. Shanghai J Acup Moxib. 1994;13:87–89 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li P, Tjen-A-Looi SC, Longhurst JC. Excitatory projections from arcuate nucleus to ventrolateral periaqueductal gray in electroacupuncture inhibition of cardiovascular reflexes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;209(6):H2535–2542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li P, Tjen-A-Looi SC, Guo ZL, Fu L-W, Longhurst JC. Long-loop pathways in cardiovascular electroacupuncture responses. J Appl Physiol. 2009;106(2):620–630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li P, Tjen-A-Looi SC, Longhurst JC. Nucleus raphé pallidus participates in midbrain-medullary cardiovascular sympathoinhibition during electroacupuncture. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2010;299(5):R1369–1376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ballegaard S, Muteki T, Harada H, et al. Modulatory effect of acupuncture on the cardiovascular system: a cross-over study. Acupunct Electrother Res. 1993;18(2):103–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sternfeld M, Fink A, Bentwich Z, Eliraz A. The role of acupuncture in asthma: changes in airways dynamics and LTC4 induced LAI. Am J Chin Med. 1989;17(3-4):129–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dan N. Clinical observation on the effect of acupuncture on hypertension by ambulatory blood pressure monitor. Chin J Comb Trad Chin Med West Med. 1998;18:26–27 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li P, Yao T. Mechanism of the Modulatory Effect of Acupuncture on Abnormal Cardiovascular Functions. Shanghai, China: Shanghai Medical University Press; 1992 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li P, Yao T. Pressor effect of electroacupuncture or somatic nerve stimulation on experimental hypotension. In: Li P, Yao T, eds. Mechanism of the Modulatory Effect of Acupuncture on Abnormal Cardiovascular Functions. Shanghai, China: Shanghai Medical University Press; 1992:32–40 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li M, Tjen-A-Looi SC, Guo ZL, Longhurst JC. Electroacupuncture modulation of reflex hypertension in rats: role of cholecystokinin octapeptide. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. Amsterdam, The Netherlands 2013;305(4):R404–413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li P. Neural mechanisms of the effect of acupuncture on cardiovascular diseases. In: Sato A, Li P, Campbell JL, eds. Acupuncture: Is There a Physiological Basis? Satellite Symposium on the 34th World Congress of the IUPS Auckland, New Zealand 24 August 2001, ICS 1238, 1e (International Congress). Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier Science; 2002:71–77 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li P, Pitsillides KF, Rendig SV, Pan HL, Longhurst JC. Reversal of reflex-induced myocardial ischemia by median nerve stimulation: a feline model of electroacupuncture. Circulation. 1998;97(12):1186–1194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li P, Rowshan K, Crisostomo M, Tjen-A-Looi SC, Longhurst JC. Effect of electroacupuncture on pressor reflex during gastric distention. Am J Physiol. 2002;283:R1335–R1345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tjen-A-Looi SC, Li P, Longhurst JC. Medullary substrate and differential cardiovascular responses during stimulation of specific acupoints. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004;287(4):R852–R62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou W, Fu LW, Tjen-A-Looi SC, Li P, Longhurst JC. Afferent mechanisms underlying stimulation modality-related modulation of acupuncture-related cardiovascular responses. J Appl Physiol. 2005;98(3):872–880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li M, Tjen-A-Looi SC, Guo ZL, Longhurst JC. Repetitive electroacupuncture causes prolonged increased met-enkephalin expression in the rVLM of conscious rats. Auton Neurosci. 2012;170(1-2):30–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li M, Chi S, Tjen-A-Looi SC, Longhurst JC. Repetitive electroacupuncture attenuates cold-induced hypertension and simultaneously enhances rVLM preproenkephalin mRNA expression. FASEB J. 2013;27:926.14 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289(19):2560–2572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaplan NM. The 6th Joint National Committee Report (JNC-6): new guidelines for hypertension therapy from the USA. Keio J Med. 1998;47(2):99–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.MacPherson H, Altman DG, Hammerschlag R, et al. Revised STandards for Reporting Interventions in Clinical Trials of Acupuncture (STRICTA): extending the CONSORT statement. J Altern Complement Med. 2010;16(10):ST1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bang HX. Standard Acupuncture Nomenclature. Manila: World Health Organization, Regional Office for the Western Pacific; 1984 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yin CS, Park HJ, Seo JC, Lim S, Koh HG. Evaluation of the cun measurement system of acupuncture point location. Am J Chin Med. 2005;33(5):729–735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Coyle M, Aird M, Cobbin DM, Zaslawski C. The Cun measurement system: an investigation into its suitability in current practice. Acupunct Med. 2000;18(1):10–14 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cardarelli F, Shields MJ. Scientific Unit Conversion: A Practical Guide to Metrication, 2nd ed. London: Springer Science and Business Media; 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li P, Ayannusi O, Reid C, Longhurst JC. Inhibitory effect of electroacupuncture (EA) on the pressor response induced by exercise stress. Clin Auton Res. 2004;14(3):182–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Turnbull F, Patel A. Acupuncture for blood pressure lowering: needling the truth. Circulation. 2007;115(24):3048–3049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li DZ, Zhou Y, Yang YN, et al. Acupuncture for essential hypertension: a meta-analysis of randomized sham-controlled clinical trials. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2014;2014:279478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kurl S, Laukkanen JA, Niskanen L, et al. Cardiac power during exercise and the risk of stroke in men. Stroke. 2005;36(4):820–824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rapsomaniki E, Timmis A, George J, et al. Blood pressure and incidence of twelve cardiovascular diseases: lifetime risks, healthy life-years lost, and age-specific associations in 1.25 million people. Lancet. 2014;383(9932):1899–1911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yin C, Seo B, Park HJ, et al. Acupuncture, a promising adjunctive therapy for essential hypertension: a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Neurol Res. 2007;29 Suppl 1:S98–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li P, Tjen-A-Looi SC., Longhurst JC. Acupuncture's role in cardiovascular homeostasis. In: Xia Ying, Dong Guanghong, Wu Gen-Cheng, eds. Current Research in Acupuncture. New York: Springer Science+Business Media; 2013:457–486 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yao T, Li P. Depressor effect of electroacupuncture or somatic nerve stimulation in experimental hypertensive animals. In: Li P, Yao T, eds. Mechanism of the Modulatory Effect of Acupuncture on Abnormal Cardiovascular Functions. Shanghai: Shanghai Med. University Press; 1992:13–31 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cheung L, Li P, Wong C. The Mechanism of Acupuncture Therapy and Clinical Case Studies. New York: Taylor and Francis; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li P, Tjen ALS. Mechanism of the inhibitory effect of electroacupuncture on experimental arrhythmias. J Acupunct Meridian Stud. 2013;6(2):69–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li P, Cheng L, Liu D, et al. Long-lasting inhibitory effect of electroacupuncture in hypertensive patients: role of catecholamine, renin and angiotensin. FASEB J. 2014;28:686.4 [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhou WY, Tjen-A-Looi SC, Longhurst JC. Brain stem mechanisms underlying acupuncture modality-related modulation of cardiovascular responses in rats. J Appl Physiol. 2005;99(3):851–860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cao X. Acupuncture Analgesia. Neurobiology. Shanghai, China: Shanghai Medical University Press; 1990:287 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Han J-S, Ding XZ, Fan SG. Cholecystokinin octapeptide (CCK-8): antagonism to electroacupuncture analgesia and a possible role in electroacupuncture tolerance. Pain. 1986;27(1):101–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhou W, Fu LW, Tjen-A-Looi SC, Guo ZL, Longhurst JC. Role of glutamate in a visceral sympathoexcitatory reflex in rostral ventrolateral medulla of cats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291(3):H1309–1318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tjen-A-Looi SC, Li P, Longhurst JC. Prolonged inhibition of rostral ventral lateral medullary premotor sympathetic neuron by electroacupuncture in cats. Auton Neurosci. 2003;106(2):119–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Moazzami A, Tjen-A-Looi SC, Guo ZL, Longhurst JC. Serotonergic projection from nucleus raphe pallidus to rostral ventrolateral medulla modulates cardiovascular reflex responses during acupuncture. J Appl Physiol. 2010;108(5):1336–1346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tjen-A-Looi SC, Li P, Longhurst JC. Role of medullary GABA, opioids, and nociceptin in prolonged inhibition of cardiovascular sympathoexcitatory reflexes during electroacupuncture in cats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293(6):H3627–3635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tjen-A-Looi SC, Li P, Longhurst JC. Midbrain vIPAG inhibits rVLM cardiovascular sympathoexcitatory responses during acupuncture. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290(6):H2543–2553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tjen-A-Looi SC, Li P, Longhurst JC. Processing cardiovascular information in the vlPAG during electroacupuncture in rats: roles of endocannabinoids and GABA. J Appl Physiol. 2009;106(6):1793–1799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li P, Tjen-A-Looi SC, Guo ZL, Longhurst JC. An arcuate-ventrolateral periaqueductal gray reciprocal circuit participates in electroacupuncture cardiovascular inhibition. Auton Neurosci. 2010;158(1-2):13–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Robinson RC, Wang Z, Victor RG, et al. Lack of effect of repetitive acupuncture on clinic and ambulatory blood pressure. Am J Hypertens. 2014;17:33A [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stokes GS. Systolic hypertension in the elderly: pushing the frontiers of therapy—a suggested new approach. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2004;6(4):192–197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nichols WW, O'Rourke MF, Avolio AP, et al. Effects of age on ventricular-vascular coupling. Am J Cardiol. 1985;55(9):1179–1184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gibson CM, Ciaglo LN, Southard MC, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic value of ambulatory ECG (Holter) monitoring in patients with coronary heart disease: a review. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2007;23(2):135–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References

To receive CME credit, you must complete the quiz online at: www.medicalacupuncture.org/cme