Abstract

Autogenous bone is the gold standard material for bone grafting in craniofacial and orthopedic regenerative medicine. However, due to complications associated with harvesting donor bone, clinicians often use commercial graft materials that may lose their osteoinductivity due to processing. This study was aimed to functionalize one of these materials, anorganic bovine bone (ABB), with osteoinductive peptides to enhance regenerative capacity. Two peptides known to induce osteoblastic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells were evaluated: (1) DGEA, an amino acid motif within collagen I and (2) a biomimetic peptide derived from bone morphogenic protein 2 (BMP2pep). To achieve directed coupling of the peptides to the graft surface, the peptides were engineered with a heptaglutamate domain (E7), which confers specific binding to calcium moieties within bone mineral. Peptides with the E7 domain exhibited greater anchoring to ABB than unmodified peptides, and E7 peptides were retained on ABB for at least 8 weeks in vivo. To assess the osteoinductive potential of the peptide-conjugated ABB, ectopic bone formation was evaluated utilizing a rat subcutaneous pouch model. ABB conjugated with full-length recombinant BMP2 (rBMP2) was also implanted as a model for current clinical treatments utilizing rBMP2 passively adsorbed to carriers. These studies showed that E7BMP2pep/ABB samples induced more new bone formation than all other peptides, and an equivalent amount of new bone as compared with rBMP2/ABB. A mandibular defect model was also used to examine intrabony healing of peptide-conjugated ABB. Bone healing was monitored at varying time points by positron emission tomography imaging with 18F-NaF, and it was found that the E7BMP2pep/ABB group had greater bone metabolic activity than all other groups, including rBMP2/ABB. Importantly, animals implanted with rBMP2/ABB exhibited complications, including inflammation and formation of cataract-like lesions in the eye, whereas no side effects were observed with E7BMP2pep/ABB. Furthermore, histological analysis of the tissues revealed that grafts with rBMP2, but not E7BMP2pep, induced formation of adipose tissue in the defect area. Collectively, these results suggest that E7-modified BMP2-mimetic peptides may enhance the regenerative potential of commercial graft materials without the deleterious effects or high costs associated with rBMP2 treatments.

Introduction

Bone replacement grafts are becoming increasingly common, with several million bone graft procedures performed annually worldwide.1,2 Bone grafts are used in orthopedic medicine for nonunion fractures and spinal fusion, and in neurosurgery for calvarial deformities and trauma repair. In craniofacial and dental applications, bone grafts are utilized for filling defects, periodontal regeneration, and implant site development. Autogenous bone is considered the ideal graft material to replace missing bone as it contains the minerals, osteoinductive proteins, and osteoprogenitor cells that promote bone growth. Autogenous bone harvested from sites, such as the iliac crest, is thought to offer the greatest osteogenic potential. Alternatively, for dental applications, intraoral bone can be harvested from the symphysis of the chin, ramus of the mandible, or maxillary tuberosity; however, osteogenicity of intraoral bone is questionable.3,4

Unfortunately, the benefits of autogenous bone are counterbalanced by several drawbacks. Harvesting bone from the patient is associated with increased morbidity, requirement for a second surgery, and quantities of donor bone are limited.5–8 To circumvent these issues, clinicians often use graft materials from commercial or bone bank sources. There are a variety of options, including mineralized and demineralized cadaveric allograft with cortical and/or cancellous components, as well as xenograft and alloplast materials from bovine, porcine, coral, and synthetic origins. Allograft tissues, while abundant, present risks of disease transmission and immunogenicity, and must therefore be sterilized and processed to remove cellular material. Processed allografts retain their osteoconductive properties, but lose any osteogenic, and most osteoinductive, potential.9 Moreover, the osteoinductivity of allograft depends on the age and other factors related to the donor at the time of harvest.10 Xenograft and alloplast materials offer other alternatives to autogenous bone, but these are also processed or manufactured in a way that leaves them devoid of organic components. These serve merely as scaffolds for native bone formation to occur. Re-establishing the osteoinductive potential of allograft, xenograft, and alloplast materials would provide a major advance toward more effective bone regenerative therapies. One approach for achieving this goal is to functionalize the graft surface with bone-inducing factors.

The activity of osteoinductive factors delivered to sites of injured or deficient bone is dependent upon the local concentration of the molecule. One such factor is the osteoinductive protein, bone morphogenic protein 2 (BMP2), which has a short half-life and must be delivered on a carrier to keep concentrations high enough to influence healing. BMP2 is typically passively adsorbed onto a carrier; however, supraphysiological doses are required for clinical efficacy because much of the BMP2 is rapidly released from the carrier shortly after implantation.11,12 The dissemination of BMP2 away from the graft site is associated with significant side effects, including inflammation and ectopic calcification.12–14 To overcome these problems, many groups are investigating methods for improving the coupling of BMP2 and other osteoinductive factors to carriers. We and others have focused on modifying bioactive peptides with a calcium-binding domain to anchor the peptides onto the surface of calcium-containing bone replacement materials.15–26 Specifically, our group has engineered osteoinductive peptides with a heptaglutamate (E7) domain. The E7 domain, which is a natural motif found within bone sialoprotein, binds tightly and specifically to calcium phosphate crystals within bone (hydroxyapatite [HA]) or synthetic biomaterials designed for bone applications. In prior studies we used a number of approaches to establish that E7 domains are highly effective in anchoring a wide variety of peptides to multiple types of substrates, including allograft, xenograft, and alloplast.15,22–24,26 For example, E7-modified peptides display tight coupling to synthetic HA disks, β-tricalcium phosphate, electrospun scaffolds with nanoHA particles, calcium sulfate bone cement, anorganic bovine bone (ABB; BioOss), and two types of allograft (OraGRAFT and MinerOss). Quantitative measurements indicate that the binding/retention of peptides can be improved between 14- and 63-fold by adding an E7 domain to the peptide, depending upon the specific carrier substrate.22,24 The current study investigated the regenerative potential of a commercial xenograft material, ABB, functionalized with E7-modified osteoinductive peptides. ABB is widely used for bone grafting, particularly in some European countries that prohibit the use of allograft materials. ABB is also used in combination with allograft in certain clinical procedures to extend the longevity of the graft, as ABB resorbs more slowly than allograft. Two types of peptides were coupled to ABB: DGEA (Asp-Gly-Glu-Ala) and a biomimetic peptide derived from BMP2 (BMP2pep). DGEA is a motif within collagen I that binds to the surface of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and stimulates osteoblastic differentiation.18,27,28 BMP2pep is derived from the knuckle domain of BMP2, which binds to type II BMP receptors to initiate signaling cascades that promote osteoblastogenesis.29,30 A number of reports have suggested that knuckle domain BMP2 peptides can substitute for full-length, recombinant BMP2 (rBMP2) in stimulating new bone synthesis (reviewed in31). In the present investigation, we evaluated the osteoinductive potential of ABB functionalized with DGEA or BMP2pep, each modified with or without an E7 domain, in two in vivo models: (1) ectopic bone growth in a subcutaneous pouch and (2) bone regeneration in a critical-size mandibular defect. ABB coated with rBMP2 was also examined to compare the responses elicited by peptides with the full-length BMP2 protein.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of peptides

DGEA, E7DGEA, BMP2pep, and E7BMP2pep were synthesized by the American Peptide Company (Sunnyvale, CA). The BMP2pep was derived from the knuckle domain within BMP2 and encompasses the amino acid sequence KIPKASSVPTELSAISTLYL. The E7BMP2pep sequence is comprised of EEEEEEEKIPKASSVPTELSAISTLYL. For some experiments, fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) was conjugated to the C-termini of peptides to facilitate detection of peptide binding to ABB. The lyophilized peptides were reconstituted in 70% deionized water and 30% acetonitrile to a concentration of 1 mg/mL. These were then aliquoted and stored at −20°C until use.

Peptide binding to ABB in vitro

ABB (BioOss, particle size: 0.25–1.0 mm) was obtained from GeistlichPharma North America, Inc. (Princeton, NJ). Fifty milligrams of ABB graft particles were measured and placed into a 12-well plate. ABB grafts were hydrated in 0.75 mL of tris-buffered saline (TBS). Equimolar solutions of the various peptides were prepared in TBS. After aspiration of the hydrating solution, 0.75 mL of the BMP2pep-FITC or E7BMP2pep-FITC solutions (10 or 100 μM) were added to each bone graft. As a “no peptide control,” ABB particles were hydrated in TBS lacking any peptide. The plate was covered in aluminum foil and placed on a shaker at room temperature for 30 min. After this incubation, the peptide solutions or TBS were aspirated and the grafts washed three times in TBS for 10 min on a shaker to remove unbound or loosely bound peptide. A portion of the graft material was removed and imaged using a Nikon fluorescent microscope.

Peptide retention on ABB in vivo

To examine peptide retention in vivo, equimolar solutions (100 μM) of BMP2pep-FITC or E7BMP2pep-FITC in TBS were prepared under sterile conditions. The peptides were conjugated onto the ABB grafts for 30 min and washed three times in TBS for 10 min each before implantation into rat subcutaneous pouches. Male Sprague Dawley rats (325–350g) were obtained from Harlan Laboratories (Indianapolis, IN). Rats were anesthetized with 1–3% isoflurane with an oxygen flow rate of 1–2 L/min. The backs of the rats were shaved and four 15 × 15 mm subcutaneous pouches were created in each animal by sharp and blunt dissection. The grafts were implanted into the pouches and the wounds closed with surgical staples. For postoperative analgesia, buprenorphine (0.1 mg/kg) was administered subcutaneously immediately following surgery. The staples were removed after 7 days. The rats were euthanized and the grafts explanted at 8 weeks. The grafts were imaged using a Nikon fluorescent microscope. All animal procedures were performed with prior approval from the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

Ectopic bone growth in subcutaneous implants

ABB particles (50 mg) were incubated for 30 min in equimolar sterile solutions (100 μM) of DGEA, E7DGEA, BMP2pep, or E7BMP2pep (note that all peptides for bone formation studies lacked the FITC tag). In addition, some ABB samples were coated for 30 min with rBMP2 (100 ng/mL), and as a negative control, ABB was incubated in TBS (uncoated). Full-length rBMP2 was obtained from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, cat #: 355-BM-010/CF). The ABB specimens were implanted into rat subcutaneous pouches created as described above. After 8 weeks, the rats were euthanized and a section of tissue removed and placed in 10% neutral buffered formalin. The samples were paraffin-embedded, sectioned, and stained with Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Islets of new bone formation within the grafted tissues were observed, and the total area of these islets was quantified under blinded conditions using Nikon Elements software. In addition, the area of remaining ABB particles was quantified, and the area of new bone islets was normalized to the ABB particulate area. Additional quantification of the average size of the islets of new bone formed was performed.

Bone formation elicited by grafts implanted into critical-size mandibular defects

Surgical procedure

Equimolar sterile solutions (100 μM) of DGEA, E7DGEA, BMP2pep, or E7BMP2pep were incubated with 35 mg of ABB for 30 min. ABB particles were also coated with rBMP2 or TBS (uncoated), as described above. Bilateral incisions were made in the rat skin at the inferior border of the posterior mandible exposing the masseter muscle. Incision of the muscle was made and muscular flap was elevated on the buccal avoiding critical structures in the area. A 5 mm circular defect was created at the angle of the exposed mandible using a stainless steel trephine bur (TRE04 from Biomet 3i, Palm Beach Gardens, FL) that was mounted in a dental implant console. A through and through defect was created under copious irrigation. After some hemostasis was obtained through pressure with sterile gauze, the modified bone grafts (35 mg) were inserted into the defects. A fast absorbing collagen wound dressing (Helitape obtained from Integra Miltex, York, PA) was placed over the defect to aid in clot formation. Also, some defects were left ungrafted to serve as a sham control group. The muscle and skin layers were sutured independently using resorbable 4-0 vicryl sutures. For postoperative analgesia, the rats were administered buprenorphine (0.1 mg/kg) and carprofen (5 mg/kg) immediately after surgery and then an additional dose of carprofen (5 mg/kg) 24 h postoperatively. The rats were fed a soft diet (Diet Gel 76A obtained from ClearH20, Portland, ME) once a day for at least 2 weeks. They also had access to standard laboratory food and water ad libitum.

Radioimaging utilizing computed tomography/positron emission tomography

18F-Sodium Fluoride (18F-NaF) was used for the positron emission tomography (PET) analysis and was obtained from PETNET Solutions, Inc. (Knoxville, TN). The radioisotope was injected into the penile vein of the anesthetized rats at a concentration of 1 mCi/300 μL. The rats were imaged at 4, 8, and 12 weeks on a FLEX Triumph PET/CT system (Gamma Medica, Salem, NH). For PET, the system provided a 2.2 mm axial spatial resolution and 5.9% sensitivity at the center of field of view (FOV) and an axial FOV of 37.5 mm. PET images were reconstructed with maximum likelihood expectation maximization algorithm (10 iterations) in high resolution mode. For computed tomography (CT), the voltage of the X-ray tube was 80 kV and the anode current was 0.11 mA. Two hundred fifty-six projections were acquired in fly gantry-motion mode. ImageJ was used to analyze the images (all analyses performed under blinded conditions). The experimental area was measured along with two reference areas per animal. A ratio of the experimental area over the average reference area for each animal was then calculated. This was done to control for potential differences in radioisotope injections in each animal.

Histological evaluation

The rats were euthanized at 12 weeks and the mandibles harvested and placed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 48 h and then switched to 70% ethanol. Representative samples from each group were paraffin embedded, sectioned, and stained with H&E. The remaining samples were embedded in plastic, sectioned, and stained with Sanderson rapid bone stain with acid fuchsin counterstain. Processing of the Sanderson-stained sections was performed by Schupbach Ltd. Service (Horgen, Switzerland).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA). If the ANOVA test was significant, pairwise t-tests were conducted. Tukey's procedure was used to correct for multiple comparisons. A significance level of α = 0.05 was used for all tests. For the subcutaneous pouch model, eight specimens per group were analyzed. The area of new bone formation, ratio of new bone to graft particles, and average islet size were calculated. For the PET/CT imaging of the mandibular defects, the sample size varied between groups. For the 4-week time point, the following number of samples was evaluated: uncoated (9), DGEA (7), E7DGEA (6), BMP2pep (8), E7BMP2pep (8), rBMP2 (8), and SHAM (4). For the 8-week time point, sample sizes were: uncoated (9), DGEA (6), E7DGEA (6), BMP2pep (8), E7BMP2pep (8), rBMP2 (9), and SHAM (5). For the 12-week time point, sample sizes were: uncoated (7), DGEA (6), E7DGEA (6), BMP2pep (8), E7BMP2pep (8), rBMP2 (9), and SHAM (4). For each time point, the ratio of 18F-NaF activity in the defect area was calculated as a ratio to the 18F-NaF activity in the reference area for each animal.

Results

Addition of an E7 domain facilitates greater binding of BMP2-mimetic peptide to ABB

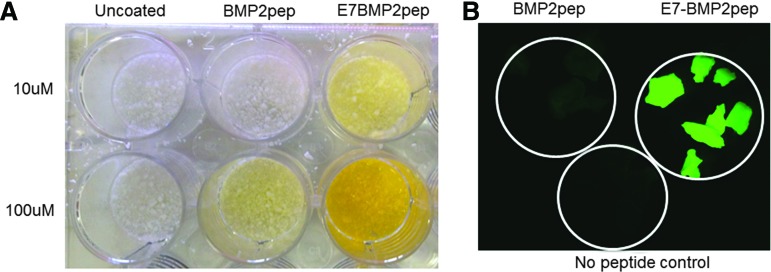

Prior studies from our group have shown that the addition of an E7 domain to the DGEA peptide significantly increases peptide binding and retention on multiple types of graft materials, including ABB.15,22–24 To determine whether the E7 domain similarly directs enhanced binding of the BMP2pep, equimolar solutions of E7BMP2pep-FITC and BMP2pep-FITC were incubated with ABB for 30 min and then samples were imaged. In addition to fluorescing, the FITC tag has a yellow tint that can be seen by the naked eye. As shown in Figure 1A, E7BMP2pep-FITC is bound to ABB in greater quantities than BMP2pep-FITC. This result was confirmed by visualizing the samples under a fluorescent microscope (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

E7 domain directs greater loading of BMP2pep onto ABB particles. (A) ABB particles were incubated with equimolar concentrations of the FITC-tagged peptides (either 10 or 100 μM) for 30 min, and then samples were washed with TBS. Increased binding of E7BMP2pep, relative to BMP2pep, was apparent on the particles by the naked eye (yellow tint). (B) ABB particles were conjugated with E7BMP2pep-FITC, BMP2pep-FITC (both peptides at 10 μM), or with saline (no peptide control) for 30 min. Imaging of samples using a fluorescent microscope revealed greater binding of E7BMP2pep compared with BMP2pep. ABB, anorganic bovine bone; BMP2, bone morphogenic protein 2; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; TBS, tris-buffered saline. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

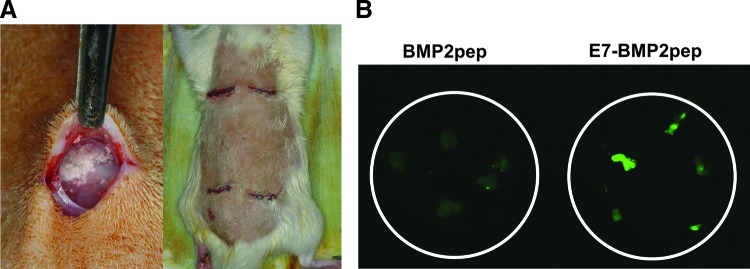

E7BMP2pep is retained on ABB for at least 8 weeks in vivo

To investigate the capacity of the E7 domain to enable peptide retention under physiological conditions, a rat subcutaneous pouch was utilized (Fig. 2A). ABB particles were conjugated with BMP2pep-FITC or E7BMP2pep-FITC, and then samples were implanted into subcutaneous pouches for 8 weeks. The grafts were explanted and imaged under a fluorescent microscope. It was observed that E7BMP2pep was still present on the ABB surface at the 8-week time point (Fig. 2B), which is clearly a sufficient interval to influence bony healing. These results are consistent with our prior work showing that E7DGEA peptides remain on the ABB surface following an 8-week implantation in subcutaneous pouches.24

FIG. 2.

E7BMP2pep is retained on ABB graft for at least 8 weeks in vivo. (A) ABB particles were conjugated with BMP2pep-FITC or E7BMP2pep-FITC and placed into rat subcutaneous pouches for 8 weeks. (B) Grafts were retrieved, washed, and imaged by fluorescent microscopy. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

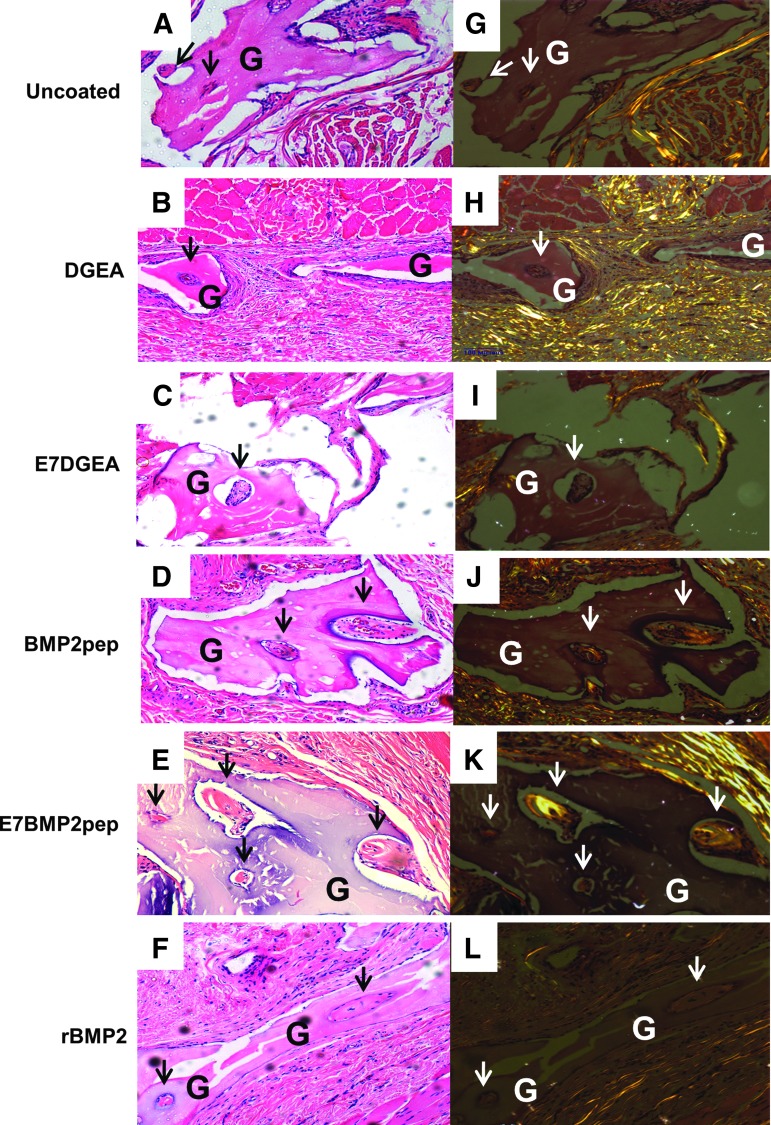

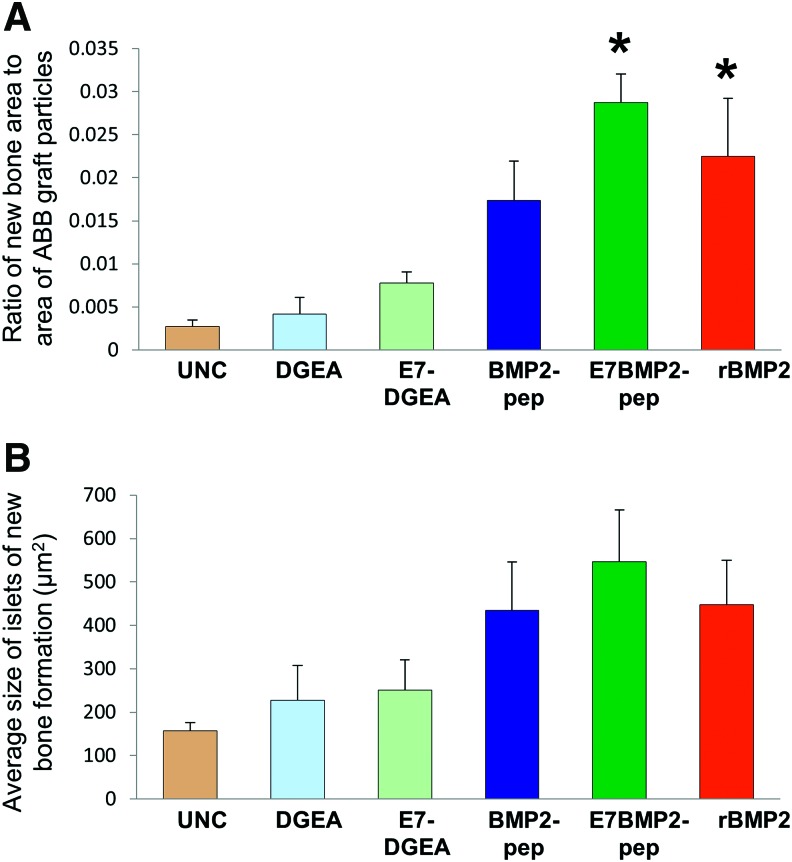

ABB conjugated with E7BMP2pep stimulates ectopic bone formation

ABB particles were conjugated with the following peptides for 30 min: DGEA, E7DGEA, BMP2pep, and E7BMP2pep (peptides for these studies lacked FITC tags). In addition, ABB was conjugated with full-length rBMP2, or incubated in saline as a negative control (uncoated). The samples were then implanted into subcutaneous pouches. At 8 weeks, the grafts were retrieved, along with a block of soft tissue surrounding the graft, and H&E staining was performed (Fig. 3A–F). Islets of new bone synthesis forming on the implanted graft particles were noted within the sections (indicated by arrows). To confirm that the islets were vital bone, polarized light images were taken (Fig. 3G–L). The total area of new bone formation was calculated using Nikon Elements software. To compensate for any potential variation in the amount of bone graft implanted, or differences in surface area, the area of ABB particulate was also measured and a ratio of the newly formed bone to ABB graft particles was calculated. It was observed that the E7BMP2pep/ABB and rBMP2/ABB groups were the only groups that stimulated a greater amount of new bone synthesis as compared with uncoated ABB samples (Fig. 4A). Additionally, the average size of the islets of new bone was measured and there appeared to be a trend toward greater islet size in the E7BMP2pep/ABB group, but this was not statistically significant (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 3.

Histological images of subcutaneous ABB grafts. ABB was incubated with either TBS (uncoated), peptides (DGEA, E7DGEA, BMP2pep, E7BMP2pep), or rBMP2 full-length protein. The grafts were then implanted into rat subcutaneous pouches and retrieved after 8 weeks. The tissue sections with embedded grafts were stained with H&E (A–F) and polarized light images were taken at 20× magnification (G–L). Arrows represent islets of new bone synthesis forming on implanted graft particles (G). rBMP2, recombinant BMP2; H&E, Hematoxylin and eosin.

FIG. 4.

E7BMP2pep stimulates new bone formation within subcutaneous graft sites. (A) The total area of new bone formation within grafts harvested from subcutaneous pouches was calculated from H&E-stained sections using Nikon NIS Elements. To compensate for any potential variation in the amount of ABB graft implanted, or differences in ABB surface area, the area of ABB particulate in each section was also measured, and the ratio of new bone to ABB graft was calculated. (B) The average size of the islets of new bone was measured. All measurements were conducted under blinded conditions. For (A, B), values represent means and standard error of the means (n = 8 samples per group). * denotes significant difference relative to uncoated sample (p < 0.05). Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

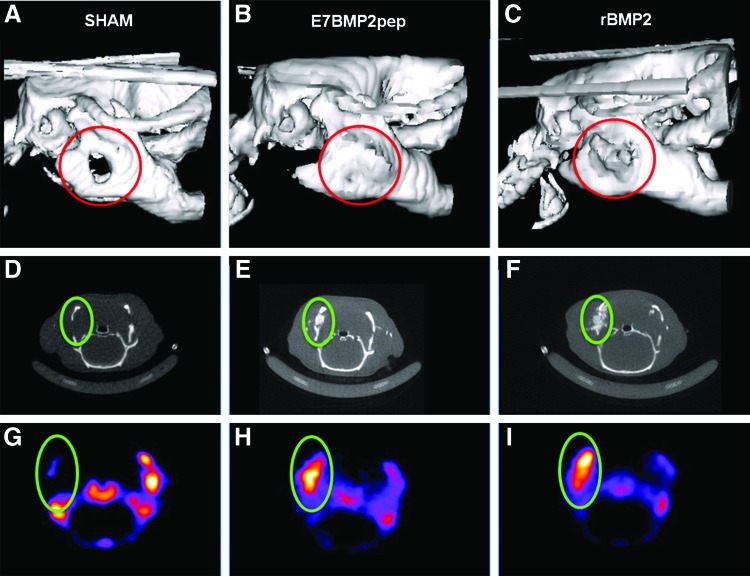

ABB conjugated with E7BMP2pep induces greater bone activity than all other groups in an intrabony model

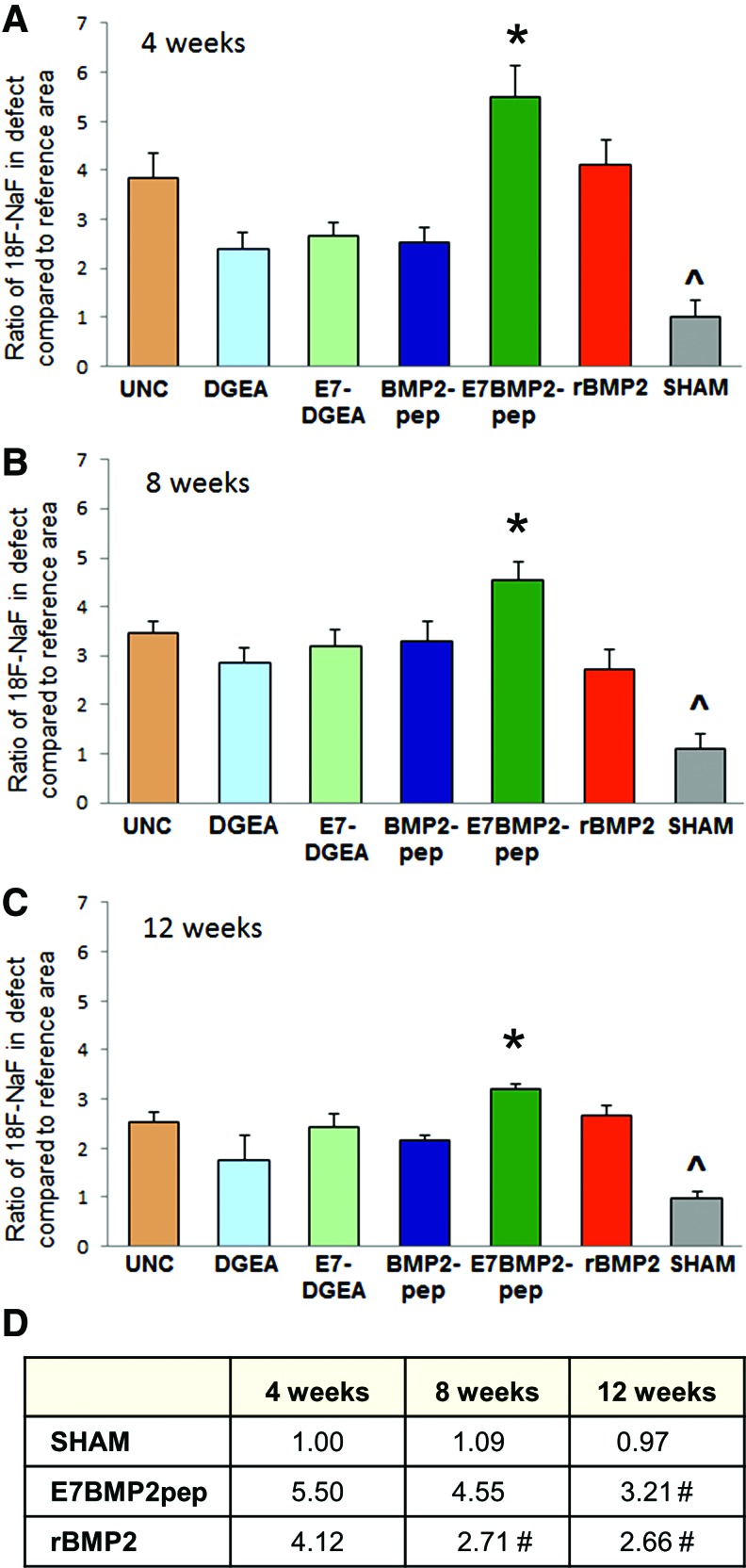

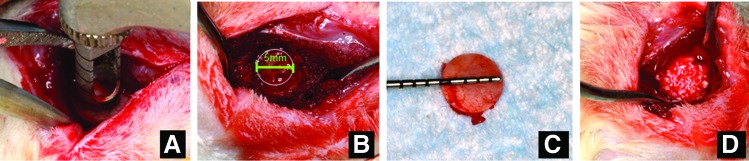

To test the capacity of peptide-conjugated ABB to regenerate bone in an intrabony model, grafts were implanted into a critical-size (5 mm) defect created at the angle of the rat mandible (Fig. 5). ABB particles were conjugated for 30 min with peptides, rBMP2, or left uncoated, and then implanted into the defect. Some defects were left unfilled to serve as a sham control. CT/PET (18F-NaF) was performed at 4, 8, and 12 weeks. 18F-NaF PET is a well-established method for detecting osteoblastic activity within a site of bone regeneration. 18F is incorporated into the HA crystals within the bone.32,33 It can also be used in conjunction with PET/CT scans, which have high sensitivity and produce good quality images.32 ImageJ was used to measure isotope uptake at the defect area and then a ratio was calculated comparing activity in the defect to a reference area within each animal (Fig. 6). Results from these assays (Fig. 7A–C) indicated that all of the defects implanted with ABB, including those with uncoated particles, had more new bone activity than the sham controls, consistent with the expectation that the critical-size defect cannot heal without intervention. Strikingly, the E7BMP2pep-conjugated ABB implants induced significantly greater new bone activity compared to all other groups, including rBMP2/ABB. This was observed at all three time points. The numerical values for bone activity in selected groups are listed in Figure 7D. These reveal a difference in the temporal pattern of bone activity for E7BMP2pep/ABB compared with rBMP2/ABB. The amount of bone activity in the E7BMP2pep/ABB group is statistically equivalent at 4 and 8 weeks, and then begins to decline at 12 weeks. In contrast, there is a significant drop in the activity of the rBMP2/ABB samples between 4 and 8 weeks, while the 8- and 12-week samples in the rBMP2/ABB group are equivalent. These findings are consistent with the concept that rBMP2 is rapidly released from the ABB carrier, whereas the E7BMP2pep is retained on the carrier for a sustained interval due to E7-directed peptide coupling to ABB. It is possible that the decreased activity in the E7BMP2pep group at 12 weeks (although still higher than the rBMP2/ABB group at 12 weeks) may be due to the natural process of bone remodeling occurring at this time point. This is advantageous because it would not be desirable to have bone activity remain indefinitely high.

FIG. 5.

Mandibular defect surgical procedure. (A) A trephine was used to create 5 mm circular defects at the angle of the mandible bilaterally. (B, C) Five millimeters circular osteotomy was created and bone removed. (D) Grafts were placed in the defect area before suturing. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

FIG. 6.

Representative examples of CT and PET images. (A–C) 3D reconstruction of CT scan at 12 weeks. (D–F) Cross-section of defect area from CT scan. (G–I) PET images of the defect area showing radioisotope activity. CT, computed tomography; PET, positron emission tomography. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

FIG. 7.

Quantification of PET/CT imaging reveals greater bone activity elicited by E7BMP2pep. Quantification was performed under blinded conditions at 4 weeks (A), 8 weeks (B), and 12 weeks (C) using ImageJ to measure radioisotope uptake at the defect area. A ratio was calculated comparing the osteoblastic activity within the defect area to a reference area (normal, unwounded bone) within each animal. Shown on the graphs are the means and standard error of the means. For each time point, * denotes values significantly greater than all other groups (p < 0.05), and ^ denotes values significantly lower than all other groups (p < 0.05). (D) The mean ratios for the sham, E7BMP2pep, and rBMP2 groups are depicted. As indicated, E7BMP2pep activity levels remain high at the 4- and 8-week time points and then taper off by 12 weeks. This is compared with rBMP2 activity levels, which are high at 4 weeks, but decline by 8 weeks. # indicates significant difference from the 4-week time point within a given group (p < 0.05). Samples sizes for the various time points were as follows: 4 weeks: uncoated (9), DGEA (7), E7DGEA (6), BMP2pep (8), E7BMP2pep (8), rBMP2 (8), and SHAM (4); 8 weeks: uncoated (9), DGEA (6), E7DGEA (6), BMP2pep (8), E7BMP2pep (8), rBMP2 (9), and SHAM (5), and 12 weeks: uncoated (7), DGEA (6), E7DGEA (6), BMP2pep (8), E7BMP2pep (8), rBMP2 (9), and SHAM (4). Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

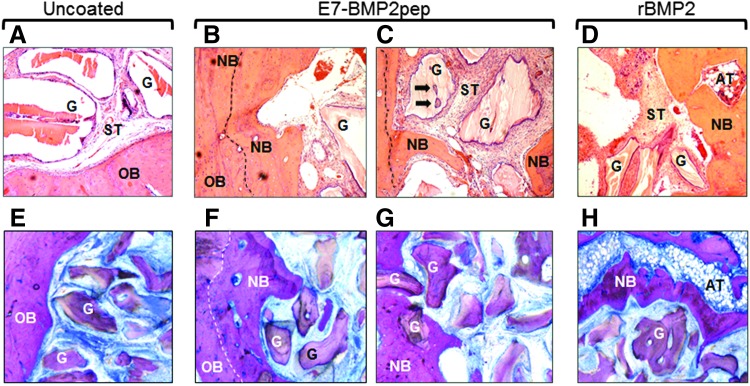

E7BMP2pep-conjugated ABB induces new bone formation as indicated by histology

At 12 weeks, the mandibles with ABB implants were harvested and evaluated by histology. A representative group stained by H&E showed new bone extending into defects implanted with either E7BMP2pep/ABB (Fig. 8B, C) or rBMP2/ABB (Fig. 8D), whereas minimal new bone in-growth was evident in uncoated ABB samples (Fig. 8A). As well, islets of new bone were apparent on some of the graft particles in the E7BMP2pep/ABB group (Fig. 8C, arrows). Sanderson bone stain with acid fuchsin counterstaining was performed on the remaining samples (Fig. 8E–H). In these specimens it was observed that many of the ABB particles conjugated with E7BMP2pep were completely encased within newly formed bone (Fig. 8G). We also noted in both the H&E and Sanderson-stained samples that ABB conjugated with rBMP2 (but not any of the peptides) induced large areas of adipose tissue (AT) rather than bone (Fig. 8D, H), consistent with the known potential of BMP2 to stimulate either adipogenesis or osteogenesis.

FIG. 8.

H!istological images of mandibular defects at 12 weeks. (A–D) H&E staining of retrieved tissues from uncoated ABB, E7BMP2pep-coated ABB, and rBMP2-coated ABB (20×). (E–H) Sanderson rapid bone stain with acid fuchsin counterstain of the uncoated ABB, E7BMP2pep/ABB, and rBMP2/ABB groups. In uncoated samples (A, E), the outline of the defect is apparent, and residual graft particles are surrounded by soft tissue rather than new bone. In the E7BMP2pep/ABB group (B, C, F, G), new bone forming from the periphery of the old bone and extending into the defect area is evident. Mineralization fronts are indicated by dashed lines. Additionally, islets of new bone have formed on the residual graft particles (arrows). In the rBMP2/ABB group (D, H), new bone has formed from the periphery of the defect, however, AT is also observed within the defect area. OB, old bone; NB, new bone; ST, soft tissue; AT, adipose tissue; G, graft particle.

Adverse side effects are associated with grafts conjugated with rBMP2, but not E7BMP2pep

Another noteworthy finding emerging from the mandibular implant studies was that animals implanted with rBMP2-conjugated ABB developed complications similar to those observed clinically with rBMP2, particularly inflammation. Fifty percent of the rats grafted with rBMP2/ABB developed significant swelling. Of these, 30% had to be euthanized because the inflammation did not resolve. Several of the rats in the rBMP2/ABB group also developed cataract-like lesions in their eyes that caused them to go blind; these animals were also euthanized. None of the rats in any other group had to be euthanized because of these complications.

Discussion

Given the disadvantages associated with autogenous bone grafts, clinicians commonly use commercial or bone bank graft sources. However, most of the available allograft, xenograft, and alloplast bone replacement products lack osteogenic and osteoinductive capacity due to processing or manufacturing methods. To enhance the osteoinductivity of these materials, many groups are investigating the potential utility of passively absorbing growth and/or differentiation factors onto the graft surface. Alternatively, osteoinductive molecules have been covalently linked to, or embedded within, synthetic biomaterials, including calcium phosphates, hydrogels, and others.34–38 As an additional approach, bioactive molecules can be anchored onto calcium-containing substrates through the use of negatively charged domains that bind to positively charged calcium ions. Examples of such domains include bisphosphonates39–42 as well as sequences comprised of negatively charged amino acids, including glutamate, aspartate, or the noncanonical amino acids, γ-carboxyglutamate and phosphoserine.15–17,19,23,25,43–45 For delivery of bioactive peptides, polyglutamate or polyaspartate domains offer some advantages over other types of calcium-binding modules. Aspartate and glutamate residues are readily available, and the polyglutamate/polyaspartate motifs can be synthesized as contiguous sequence with the bioactive part of the peptide using a commercial peptide synthesizer. In contrast, bisphosphonate groups must be chemically linked to the peptide and the use of bisphosphonate as an anchoring domain introduces a non-needed pharmacological agent into the graft site.

The concept underlying the polyglutamate coupling approach derives from the mechanism employed by native bone-binding proteins to anchor to bone. Bone matrix proteins such as bone sialoprotein and osteocalcin have polyglutamate/polyaspartate sequences, and these bind to HA, a calcium phosphate crystal within bone mineral.16,46–48 The co-opting of this mechanism to enhance binding of synthetic peptides to calcium substrates offers a practical strategy for coupling biologics to existing commercial bone graft materials. Large quantities of highly pure peptides can be produced in a cost-efficient manner. Moreover, polyglutamate-modified peptides exhibit near maximal binding to graft materials within 30–60 min,15,22 suggesting that off-the-shelf graft materials could be conjugated with the peptides shortly before surgical placement. In addition, the length of the polyglutamate domain can be varied to tailor peptide release kinetics.23 A final advantage is that polyglutamate domains bind effectively to a multiplicity of materials used for bone repair, including several types of allograft, alloplast, and xenograft.15,22–24 We have also shown that cargo-bearing protein nanocage structures modified with polyglutamate domains exhibit specific binding to synthetic HA and bone allograft,49 demonstrating that the polyglutamate–calcium bond is sufficiently strong to anchor particles to graft materials. Thus, polyglutamate domains can be employed in a wide variety of therapeutic settings.

In the current investigation we evaluated the osteoinductive potential of two peptides, each modified with or without an E7 domain: DGEA and BMP2pep. DGEA was chosen because in prior studies DGEA (adsorbed to synthetic HA) promoted in vitro osteoblastic differentiation of MSCs, as well as new bone formation in a tibial implant model.15 These responses were enhanced when DGEA was modified with an E7 domain to increase peptide coupling to the carrier.15 DGEA and E7DGEA peptides were compared herein with BMP2pep and E7BMP2pep, and also with rBMP2. Results indicate that greater new bone formation was elicited by E7BMP2pep-conjugated ABB relative to all other peptides when examined in both the subcutaneous implant and mandibular defect models. The lack of effect of E7DGEA in these studies was somewhat surprising, and may be related to either the different implant sites examined in this study or to the use of ABB as a carrier rather than synthetic HA. When compared with rBMP2/ABB, it was found that E7BMP2pep/ABB stimulated equivalent bone formation in the subcutaneous implant model, whereas in the mandibular defect model, E7BMP2pep/ABB induced significantly greater new bone activity than rBMP2/ABB at all time points examined. This is a significant finding because E7BMP2pep is a 27 amino acid sequence that can be produced by a commercial peptide synthesizer rather than through recombinant protein engineering (as required for rBMP2), thus reducing the cost and eliminating the need for host cell systems, which can introduce antigenic or pathogenic contaminants. We hypothesize that the greater efficacy of the E7BMP2pep is due to the sustained retention of E7BMP2pep on the ABB surface, which keeps the E7BMP2pep localized to the bone defect site. Supporting this hypothesis, bone activity within mandibular defects remained equivalently high at 4 and 8 weeks in the E7BMP2pep/ABB group, whereas a precipitous drop in activity between 4 and 8 weeks was observed for rBMP2/ABB samples, consistent with the rapid release of rBMP2 from carriers.

Another key observation is that the E7BMP2pep did not elicit any deleterious side effects, in contrast to animals implanted with rBMP2. In the mandibular defect model, 30% of the animals in the rBMP2/ABB group had unresolved inflammation, and required euthanasia. An additional 20% of animals in this group had to be euthanized due to the formation of cataract-like lesions that caused blindness. It is well-accepted that many of the side effects associated with clinical use of rBMP2, particularly inflammation and ectopic bone formation, occur as a result of rBMP2 dissemination away from the graft site. We hypothesize that this issue is alleviated through the use of the E7 domain, which keeps BMP2 mimetics localized to the graft site. Another intriguing result was that rBMP2-conjugated grafts stimulated adipose tissue formation, rather than bone, in many of the specimens. BMPs are known to stimulate both osteogenesis and adipogenesis, depending upon the microenvironment.50,51 The complexities inherent in BMP2-related signaling pathways may be related to the observation that clinical responses to rBMP2 are often unpredictable.52 Given these issues, a method that enables controlled and localized delivery of BMP2, utilizing lower doses that do not evoke harmful side effects, would have a major impact on treatment outcomes.

In conclusion, results from this study demonstrate that modification of the osteoinductive BMP2pep with an E7 domain markedly increased peptide binding to bone graft materials, enabling peptide retention on the grafts for at least 8 weeks in vivo. Correspondingly, better anchoring of the E7BMP2pep translated to an enhanced bone inductive response in two implant models. Importantly, E7BMP2pep stimulated at least equivalent, and by some measures greater, new bone formation than materials conjugated with full-length rBMP2. Finally, no harmful side effects were elicited by E7BMP2pep in contrast to the substantial inflammation observed with rBMP2-modified implants. Taken together, these results suggest that E7BMP2pep may be applied to a diverse range of bone graft products to endow these materials with osteoinductive capability.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH grant R01 DE024670 (S.L.B., M.S.R.) and a grant from the Osseointegration Foundation (S.L.B., M.S.R.). Dr. Bain was supported by the Dental Academic Research Training Program T32 DE017607, and NIH postdoctoral fellowship 1F32DE022997. The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance with statistical analyses by Dr. Charity Morgan, Director of the UAB Biostatistics Core Facility. Additionally, the UAB Histomorphometry Core Facility provided assistance with histology.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Giannoudis P.V., Dinopoulos H., and Tsiridis E. Bone substitutes: an update. Injury 36 Suppl 3, S20, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marino J.T., and Ziran B.H. Use of solid and cancellous autologous bone graft for fractures and nonunions. Orthop Clin North Am 41, 15, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ellegaard B., and Loe H. New attachment of periodontal tissues after treatment of intrabony lesions. J Periodontol 42, 648, 1971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Renvert S., Garrett S., Shallhorn R.G., and Egelberg J. Healing after treatment of periodontal intraosseous defects. III. Effect of osseous grafting and citric acid conditioning. J Clin Periodontol 12, 441, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goulet J.A., Senunas L.E., DeSilva G.L., and Greenfield M.L. Autogenous iliac crest bone graft. Complications and functional assessment. Clin Orthop Relat Res 339, 76, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Banwart J.C., Asher M.A., and Hassanein R.S. Iliac crest bone graft harvest donor site morbidity. A statistical evaluation. Spine 20, 1055, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brighton C.T., Shaman P., Heppenstall R.B., Esterhai J.L., Jr., Pollack S.R., and Friedenberg Z.B. Tibial nonunion treated with direct current, capacitive coupling, or bone graft. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 321, 223, 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernyhough J.C., Schimandle J.J., Weigel M.C., Edwards C.C., and Levine A.M. Chronic donor site pain complicating bone graft harvesting from the posterior iliac crest for spinal fusion. Spine 17, 1474, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kurien T., Pearson R.G., and Scammell B.E. Bone graft substitutes currently available in orthopaedic practice: the evidence for their use. Bone Joint J 95-B, 583, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang M., Powers R.M., Jr., and Wolfinbarger L., Jr. Effect(s) of the demineralization process on the osteoinductivity of demineralized bone matrix. J Periodontol 68, 1085, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bose S., and Tarafder S. Calcium phosphate ceramic systems in growth factor and drug delivery for bone tissue engineering: a review. Acta Biomater 8, 1401, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haidar Z.S., Hamdy R.C., and Tabrizian M. Delivery of recombinant bone morphogenetic proteins for bone regeneration and repair. Part A: current challenges in BMP delivery. Biotechnol Lett 31, 1817, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shimer A.L., Oner F.C., and Vaccaro A.R. Spinal reconstruction and bone morphogenetic proteins: open questions. Injury 40 Suppl 3, S32, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buttermann G.R. Prospective nonrandomized comparison of an allograft with bone morphogenic protein versus an iliac-crest autograft in anterior cervical discectomy and fusion. Spine J 8, 426, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Culpepper B.K., Phipps M.C., Bonvallet P.P., and Bellis S.L. Enhancement of peptide coupling to hydroxyapatite and implant osseointegration through collagen mimetic peptide modified with a polyglutamate domain. Biomaterials 31, 9586, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fujisawa R., Mizuno M., Nodasaka Y., and Kuboki Y. Attachment of osteoblastic cells to hydroxyapatite crystals by a synthetic peptide (Glu7-Pro-Arg-Gly-Asp-Thr) containing two functional sequences of bone sialoprotein. Matrix Biol 16, 21, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fujisawa R., Wada Y., Nodasaka Y., and Kuboki Y. Acidic amino acid-rich sequences as binding sites of osteonectin to hydroxyapatite crystals. Biochim Biophys Acta 1292, 53, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gilbert M., Giachelli C.M., and Stayton P.S. Biomimetic peptides that engage specific integrin-dependent signaling pathways and bind to calcium phosphate surfaces. J Biomed Mater Res A 67, 69, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Itoh D., Yoneda S., Kuroda S., Kondo H., Umezawa A., Ohya K., Ohyama T., and Kasugai S. Enhancement of osteogenesis on hydroxyapatite surface coated with synthetic peptide (EEEEEEEPRGDT) in vitro. J Biomed Mater Res 62, 292, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murphy M.B., Hartgerink J.D., Goepferich A., and Mikos A.G. Synthesis and in vitro hydroxyapatite binding of peptides conjugated to calcium-binding moieties. Biomacromolecules 8, 2237, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sawyer A.A., Hennessy K.M., and Bellis S.L. The effect of adsorbed serum proteins, RGD and proteoglycan-binding peptides on the adhesion of mesenchymal stem cells to hydroxyapatite. Biomaterials 28, 383, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Culpepper B.K., Bonvallet P.P., Reddy M.S., Ponnazhagan S., and Bellis S.L. Polyglutamate directed coupling of bioactive peptides for the delivery of osteoinductive signals on allograft bone. Biomaterials 34, 1506, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Culpepper B.K., Webb W.M., Bonvallet P.P., and Bellis S.L. Tunable delivery of bioactive peptides from hydroxyapatite biomaterials and allograft bone using variable-length polyglutamate domains. J Biomed Mater Res A 102, 1008, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bain J.L., Culpepper B.K., Reddy M.S., and Bellis S.L. Comparing variable-length polyglutamate domains to anchor an osteoinductive collagen-mimetic peptide to diverse bone graft materials. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 29, 1437, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brounts S.H., Lee J.S., Weinberg S., Lan Levengood S.K., Smith E.L., and Murphy W.L. High affinity binding of an engineered, modular peptide to bone tissue. Mol Pharm 10, 2086, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sawyer A.A., Weeks D.M., Kelpke S.S., McCracken M.S., and Bellis S.L. The effect of the addition of a polyglutamate motif to RGD on peptide tethering to hydroxyapatite and the promotion of mesenchymal stem cell adhesion. Biomaterials 26, 7046, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anderson J.M., Kushwaha M., Tambralli A., Bellis S.L., Camata R.P., and Jun H.W. Osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells directed by extracellular matrix-mimicking ligands in a biomimetic self-assembled peptide amphiphile nanomatrix. Biomacromolecules 10, 2935, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hennessy K.M., Pollot B.E., Clem W.C., Phipps M.C., Sawyer A.A., Culpepper B.K., and Bellis S.L. The effect of collagen I mimetic peptides on mesenchymal stem cell adhesion and differentiation, and on bone formation at hydroxyapatite surfaces. Biomaterials 30, 1898, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.He X., Ma J., and Jabbari E. Effect of grafting RGD and BMP-2 protein-derived peptides to a hydrogel substrate on osteogenic differentiation of marrow stromal cells. Langmuir 24, 12508, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saito A., Suzuki Y., Ogata S., Ohtsuki C., and Tanihara M. Activation of osteo-progenitor cells by a novel synthetic peptide derived from the bone morphogenetic protein-2 knuckle epitope. Biochim Biophys Acta 1651, 60, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Senta H., Park H., Bergeron E., Drevelle O., Fong D., Leblanc E., Cabana F., Roux S., Grenier G., and Faucheux N. Cell responses to bone morphogenetic proteins and peptides derived from them: biomedical applications and limitations. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 20, 213, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hetzel M., Arslandemir C., Konig H.H., Buck A.K., Nussle K., Glatting G., Gabelmann A., Hetzel J., Hombach V., and Schirrmeister H. F-18 NaF PET for detection of bone metastases in lung cancer: accuracy, cost-effectiveness, and impact on patient management. J Bone Miner Res 18, 2206, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hawkins R.A., Choi Y., Huang S.C., Hoh C.K., Dahlbom M., Schiepers C., Satyamurthy N., Barrio J.R., and Phelps M.E. Evaluation of the skeletal kinetics of fluorine-18-fluoride ion with PET. J Nucl Med 33, 633, 1992 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Durrieu M.C., Pallu S., Guillemot F., Bareille R., Amedee J., Baquey C.H., Labrugere C., and Dard M. Grafting RGD containing peptides onto hydroxyapatite to promote osteoblastic cells adhesion. J Mater Sci Mater Med 15, 779, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mariner P.D., Wudel J.M., Miller D.E., Genova E.E., Streubel S.O., and Anseth K.S. Synthetic hydrogel scaffold is an effective vehicle for delivery of INFUSE (rhBMP2) to critical-sized calvaria bone defects in rats. J Orthop Res 31, 401, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nelson M., Balasundaram G., and Webster T.J. Increased osteoblast adhesion on nanoparticulate crystalline hydroxyapatite functionalized with KRSR. Int J Nanomedicine 1, 339, 2006 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang C., Cheng K., Weng W., and Yang C. Immobilization of RGD peptide on HA coating through a chemical bonding approach. J Mater Sci Mater Med 20, 2349, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boerckel J.D., Kolambkar Y.M., Stevens H.Y., Lin A.S., Dupont K.M., and Guldberg R.E. Effects of in vivo mechanical loading on large bone defect regeneration. J Orthop Res 30, 1067, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gittens S.A., Bagnall K., Matyas J.R., Lobenberg R., and Uludag H. Imparting bone mineral affinity to osteogenic proteins through heparin-bisphosphonate conjugates. J Control Release 98, 255, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schuessele A., Mayr H., Tessmar J., and Goepferich A. Enhanced bone morphogenetic protein-2 performance on hydroxyapatite ceramic surfaces. J Biomed Mater Res A 90, 959, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Uludag H., Gao T., Wohl G.R., Kantoci D., and Zernicke R.F. Bone affinity of a bisphosphonate-conjugated protein in vivo. Biotechnol Prog 16, 1115, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Uludag H., Kousinioris N., Gao T., and Kantoci D. Bisphosphonate conjugation to proteins as a means to impart bone affinity. Biotechnol Prog 16, 258, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee J.S., Lee J.S., and Murphy W.L. Modular peptides promote human mesenchymal stem cell differentiation on biomaterial surfaces. Acta Biomater 6, 21, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sakuragi M., Kitajima T., Nagamune T., and Ito Y. Recombinant hBMP4 incorporated with non-canonical amino acid for binding to hydroxyapatite. Biotechnol Lett 33, 1885, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yokogawa K., Miya K., Sekido T., Higashi Y., Nomura M., Fujisawa R., Morito K., Masamune Y., Waki Y., Kasugai S., and Miyamoto K. Selective delivery of estradiol to bone by aspartic acid oligopeptide and its effects on ovariectomized mice. Endocrinology 142, 1228, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ganss B., Kim R.H., and Sodek J. Bone sialoprotein. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 10, 79, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hoang Q.Q., Sicheri F., Howard A.J., and Yang D.S. Bone recognition mechanism of porcine osteocalcin from crystal structure. Nature 425, 977, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stayton P.S., Drobny G.P., Shaw W.J., Long J.R., and Gilbert M. Molecular recognition at the protein-hydroxyapatite interface. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 14, 370, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Culpepper B.K., Morris D.S., Prevelige P.E., and Bellis S.L. Engineering nanocages with polyglutamate domains for coupling to hydroxyapatite biomaterials and allograft bone. Biomaterials 34, 2455, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zara J.N., Siu R.K., Zhang X., Shen J., Ngo R., Lee M., Li W., Chiang M., Chung J., Kwak J., Wu B.M., Ting K., and Soo C. High doses of bone morphogenetic protein 2 induce structurally abnormal bone and inflammation in vivo. Tissue Eng Part A 17, 1389, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Heinecke K., Seher A., Schmitz W., Mueller T.D., Sebald W., and Nickel J. Receptor oligomerization and beyond: a case study in bone morphogenetic proteins. BMC Biol 7, 59, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chenard K.E., Teven C.M., He T.C., and Reid R.R. Bone morphogenetic proteins in craniofacial surgery: current techniques, clinical experiences, and the future of personalized stem cell therapy. J Biomed Biotechnol 2012, 601549, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]