Abstract

Idiopathic pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis (IPPFE) is a recently described rare condition, characterized by pleural and subpleural parenchymal fibrosis, predominantly in the upper lobes. The clinical course of this disease is progressive and prognosis is poor, with little information regarding the etiology of IIPPFE. This report describes an IPPFE patient with convincing evidence of inhalational dust and suggests that dust exposure should be considered as a new causative factor of IPPFE.

Keywords: Pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis, idiopathic interstitial pneumonias, dust exposure

Introduction

Idiopathic pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis (IPPFE) is a recently reported group of disorders, first described by Frankel et al. in 2004 [1]. The authors identified five cases of a unique idiopathic pleuroparenchymal lung disease characterized by fibrotic thickening of the pleural and subpleural parenchyma, predominantly in the upper lobes. Such clinicopathological entity did not fit any previously established category of idiopathic interstitial pneumonia. More cases have been reported later and share similar clinical, radiographic and pathologic features. Consequently, in the updated American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society classification of idiopathic interstitial pneumonias [2], IPPFE is included as a separate but well-defined category of rare entities. The authors report a new potential etiology of IPPFE in a female patient.

Case report

A 49-year-old female who is a never-smoker was referred to our hospital with a complaint of chest pain and dyspnea. She has worked in a refractory plant as a cremator for 9 years and had convincing evidences of industrial dust exposure. The patient had no known family history of pulmonary disease. Physical examination showed reduced breath sounds and fine crackles in both lower lobes. Serology tests were negative for autoantibodies, rapid plasma regain and rheumatoid factor. Lung function tests showed restrictive ventilatory defects.

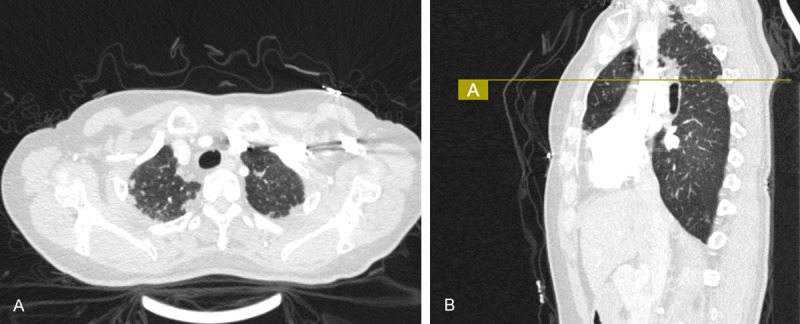

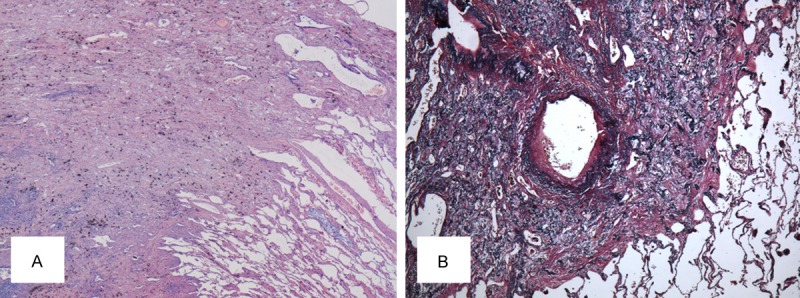

Chest computed tomography (CT) revealed bilateral irregular pleural thickening mainly represented in the upper lobes (Figure 1). An open lung biopsy (Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Surgery) was performed on the right upper lobe. Histopathology examination of the surgical lung biopsy specimen showed markedly thickened visceral pleura and prominent subpleural fibrosis characterized by abnormal increase of elastic tissue and dense collagen, abrupt transition to normal parenchyma was also seen (Figure 2). The clinical imaging and histological features of this patient were compatible with idiopathic pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis (IPPFE).

Figure 1.

Chest CT scan showed: A. Bilateral pleural thickening and irregular pleural-based opacities. B. The radiographic changes mainly represented in the upper lobes. CT, computed tomography.

Figure 2.

Histopathological findings in the surgical lung biopsy specimen. A. Hematoxylin-eosin, original ×20) showed fibrous thickened visceral pleura with an abrupt transition to normal lung parenchyma. B. Elastic fiber staining, original×40) demonstrated an abundance of short, amorphous elastic fibers in the thickened interstitium.

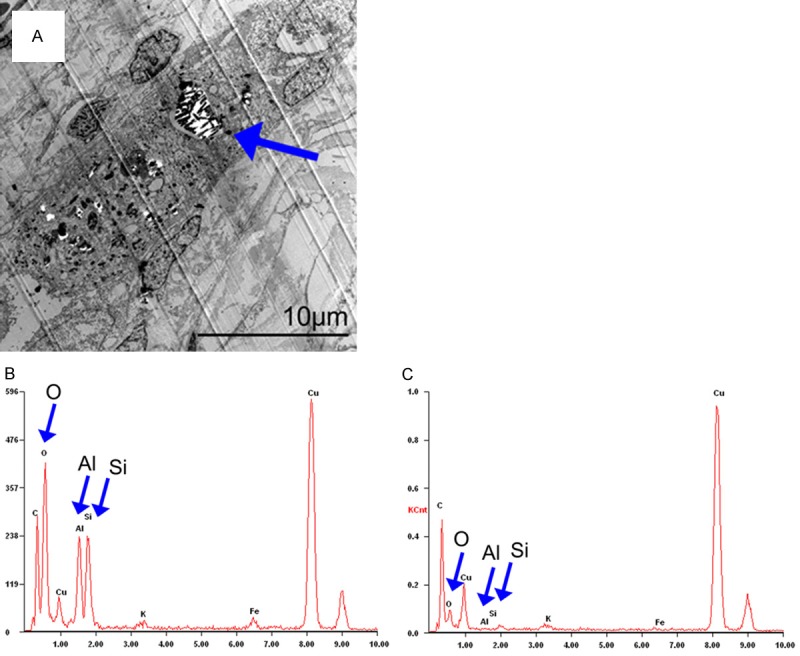

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) has been used to identify a few suspicious particles that were discovered through polarized optical microscope (POM). The TEM examination showed dust-like crystal structures in the lung tissue (Figure 3A), and X-ray microelemental analysis revealed an abnormally high concentration of aluminum, silicon and oxygen (Figure 3B, 3C). It can be speculated that these particles were inhalational dust, probably aluminosilicate (the main crude material for refractories industries), since the patient once worked in a refractory plant.

Figure 3.

A. Electron microscopy revealed alveolar macrophages containing dust-like phagocytic vacuoles (arrow). B. X-ray microelemental analysis revealed aluminum, silicon and oxygen (Al, Si and O as indicated by arrow) to be a significant component of biopsied lung tissue. C. X-ray microelemental analysis of normal lung tissue.

Discussion

We report a patient with well-documented dust exposure in which clinical presentation, imaging, and histopathological features are compatible with IPPFE. In this case, IPPFE may have been causally related to prior exposure to dust. Based on an extensive review of the literature, the case reported here suggests a new potential etiology of IPPFE.

Although there is insufficient knowledge about the etiology of IPPFE, several observations that may be of relevance to cause this condition have been reported. A few cases have underlying diseases or conditions such as bone-marrow transplantation [3,4], lung transplantation [5] or antineoplastic therapy [1,6]. Reddy et al. believed that repeated inflammatory damage in a predisposed individual have a role in its pathogenesis [7]. Frankel et al. reported two cases that were siblings revealed that genetic predisposition is probably another factor [1]. New data has been published suggesting that asinine herpesvirus may associate with some donkey pulmonary fibrosis which was categorized as being consistent with IPPFE [8]. The potential role of dust exposure as a cause for IPPFE has not been discussed previously. Although two patients reported suspected asbestos exposure [9,10], none of them offered convincing evidence of asbestos exposure, and the ferruginous bodies were universally absent.

In our patient, previous causes of IPPFE were ruled out according to her clinical presentation and laboratory findings. Based on the presence of dust-like crystal structures and the increased aluminum, silicon and oxygen in the lung biopsy specimen that compatible with the patient’s history of occupational exposure to aluminosilicate, we feel it is reasonable to speculate that dust exposure should be considered as a possible causative factor in the pathophysiology of IPPFE.

Kang et al. and Jung et al. reported TGF-α increased in the mice stimulated by Asian sand dust which has similar composition of aluminosilicate [11,12]. While TGF-α upregulation causes pleural and parenchymal fibrosis with markedly increased elastin expresses in a murine model [13,14]. This gives us a hint that TGF-α may play an important role in the pathogenesis of dust-related IPPFE.

Conclusion

We report the first case of IPPFE probably attributable to dust exposure. Identification of the etiology can help us understand the disease mechanisms and put forward effective treatments since supportive care and ultimately lung transplantation are only options for these patients at present.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Scientific Research Fund (81570053), the Shanghai Science and Technology Committee of Medical Key Technology Research Fund (09411951600), the Medical Key Special Fund from the Shanghai Municipal Health Medical Bureau (20134034) and the Medical Science and Technology Development Research Center Fund of the Ministry of Health (W2013GJ61).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Frankel SK, Cool CD, Lynch DA, Brown KK. Idiopathic Pleuroparenchymal Fibroelastosis: Description of a Novel Clinicopathologic Entity. Chest. 2004;126:2007–13. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.6.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Travis WD, Costabel U, Hansell DM, King TE Jr, Lynch DA, Nicholson AG, Ryerson CJ, Ryu JH, Selman M, Wells AU, Behr J, Bouros D, Brown KK, Colby TV, Collard HR, Cordeiro CR, Cottin V, Crestani B, Drent M, Dudden RF, Egan J, Flaherty K, Hogaboam C, Inoue Y, Johkoh T, Kim DS, Kitaichi M, Loyd J, Martinez FJ, Myers J, Protzko S, Raghu G, Richeldi L, Sverzellati N, Swigris J, Valeyre D ATS/ERS Committee on Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: Update of the international multidisciplinary classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:733–48. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201308-1483ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.von der Thüsen JH, Hansell DM, Tominaga M, Veys PA, Ashworth MT, Owens CM, Nicholson AG. Pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis in patients with pulmonary disease secondary to bone marrow transplantation. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:1633–9. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2011.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fujikura Y, Kanoh S, Kouzaki Y, Hara Y, Matsubara O, Kawana A. Pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis as a series of airway complications associated with chronic graft-versus-host disease following allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Intern Med. 2014;53:43–6. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.53.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirota T, Fujita M, Matsumoto T, Higuchi T, Shiraishi T, Minami M, Okumura M, Nabeshima K, Watanabe K. Pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis as a manifestation of chronic lung rejection? Eur Respir J. 2013;41:243–5. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00103912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beynat-Mouterde C, Beltramo G, Lezmi G, Pernet D, Camus C, Fanton A, Foucher P, Cottin V, Bonniaud P. Pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis as a late complication of chemotherapy agents. Eur Respir J. 2014;44:523–7. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00214713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reddy TL, Tominaga M, Hansell DM, von der Thusen J, Rassl D, Parfrey H, Guy S, Twentyman O, Rice A, Maher TM, Renzoni EA, Wells AU, Nicholson AG. Pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis: a spectrum of histopathological and imaging phenotypes. Eur Respir J. 2012;40:377–85. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00165111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miele A, Dhaliwal K, Du Toit N, Murchison JT, Dhaliwal C, Brooks H, Smith SH, Hirani N, Schwarz T, Haslett C, Wallace WA, McGorum BC. Chronic pleuropulmonary fibrosis and elastosis of aged donkeys: similarities to human pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis. Chest. 2014;145:1325–32. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Piciucchi S, Tomassetti S, Casoni G, Sverzellati N, Carloni A, Dubini A, Gavelli G, Cavazza A, Chilosi M, Poletti V. High resolution CT and histological findings in idiopathic pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis: features and differential diagnosis. Respir Res. 2011;12:111. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-12-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Becker CD, Gil J, Padilla ML. Idiopathic pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis: an unrecognized or misdiagnosed entity? Mod Pathol. 2008;21:784–7. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2008.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kang IG, Jung JH, Kim ST. Asian sand dust enhances allergen-induced th2 allergic inflammatory changes and mucin production in BALB/c mouse lungs. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2012;4:206–13. doi: 10.4168/aair.2012.4.4.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jung JH, Kang IG, Cha HE, Choe SH, Kim ST. Effect of Asian sand dust on mucin production in NCI-H292 cells and allergic murine model. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;146:887–94. doi: 10.1177/0194599812439011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hardie WD, Piljan-Gentle A, Dunlavy MR, Ikegami M, Korfhagen TR. Dose-dependent lung remodeling in transgenic mice expressing transforming growth factor-alpha. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2001;281:L1088–94. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.281.5.L1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hardie WD, Le Cras TD, Jiang K, Tichelaar JW, Azhar M, Korfhagen TR. Conditional expression of transforming growth factor-alpha in adult mouse lung causes pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;286:L741–9. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00208.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]