Abstract

Background:

Periodontal plastic surgical procedures aimed at coverage of exposed root surface. Owing to the second surgical donor site and difficulty in procuring a sufficient graft for the treatment of root coverage procedures, various alternative additive membranes have been used. A recent resorbable amniotic membrane, not only maintains the structural and anatomical configuration of regenerated tissues, but also enhances gingival wound healing, provides a rich source of stem cells. Therefore, amniotic membrane is choice of material these days in augmenting the better results in various periodontal procedures.

Aim:

The aim of this observational case series was to evaluate the effectiveness, predictability and the use of a novel material, amniotic membrane in the treatment of shallow-to-moderate isolated recession defects.

Materials and Methods:

A total of three cases, showing Miller's Class I or Class II gingival recession, participated in this study. Recession depth, recession width, keratinized gingiva (KG) tissue width, clinical attachment level (CAL) were recorded at baseline, 3 and 6 months postoperatively.

Results:

Six months following root coverage procedures, the mean root coverage was found to be 70.2 ± 6.8%. CAL significantly decreased from 6.4 ± 0.54 mm preoperatively to 3.5 ± 0.9 mm postoperatively at 6 months while KG showed significant improvement from 3.2 ± 0.28 mm preoperatively to 5.9 ± 0.74 mm postoperatively at 6 months.

Conclusion:

Autogenous graft tissue procurement significantly increases patient morbidity while also lengthening the duration of surgery in placing the graft, while self-adherent nature of amniotic membrane significantly reduces surgical time and made the procedure easier to perform, making it membrane of choice.

Keywords: Amniotic membrane, gingival recession, guided tissue regeneration

INTRODUCTION

Gingival recession is the term for the exposure of root surface due to apical migration of gingival margins. Many patients seek treatment because of concerns about esthetic appearance, root sensitivity, or fear of early loss of the affected teeth. However, other complications can also arise, such as root caries and tooth discoloration[1] as it has a multifactorial etiology associated with anatomical factors, or physiological or pathological factors.[2]

The goal of treating gingival recession is to restore the gingival margin to the cementoenamel junction (CEJ) and create normal sulcus with a functional attachment.[3] Various periodontal plastic surgical techniques have been used for its treatment including pedicle soft tissue graft, free soft tissue graft, and subepithelial connective tissue graft (SCTG).[4,5,6] Although these procedures produces predictable root coverage, the healing but results in the formation of a long junctional epithelium with minor amounts of connective tissue attachment with little or no new cementum or bone.[7]

Tinti and Vincenzi[8] in 1990 used the principles of guided tissue regeneration (GTR) to obtain coverage of the denuded root surface along with regeneration of the entire attachment apparatus.

Today, the concept of excluding the gingival epithelium with the mere use of barrier membranes has evolved to the incorporation of the correct signaling molecules like the growth factors and the presence of correct cell population like the stem cells, fibroblast, and cementoblast directly into the wound to promote regeneration. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are one of the major cells population that play an important role in mediating each phase of the wound healing process: Inflammatory, proliferative, and remodeling.

Recently, the fetal derived MSCs from the placenta or other gestational tissues like the amniotic fluid, umbilical cord are novel materials with rich stem cell reserves. The use of placental tissue for the treatment of wound started > 100 years ago when Davis in 1910 first used these fetal membranes as skin substitutes for the treatment of open wounds.[9]

Diño et al.[10] demonstrated for the 1st time that amniotic membrane could be separated, sterilized and safely used at a later date. Amnion-derived cells with multipotent differentiation ability have attracted lot of attention in the regeneration of periodontal tissues.

Amnion lines the innermost portion of the amniotic sac of the placenta. Its structure consists of a single layer of epithelium cells, thin reticular fibers (basement membrane), a thick compact layer, and a fibroblast layer. The basement membrane contains collagen type III, IV, and V and cell-adhesion bioactive factors including fibronectin and laminins.[11] Data suggest the amnion basement membrane closely mimics the basement membrane of human oral mucosa.[12]

Despite the introduction of allograft dermis tissue products and biologic mediators, autograft tissue remains the “gold standard” of periodontal plastic surgery as it provides excellent predictability, improved long-term root coverage, and superior esthetics over other treatment options.[13] Despite these clinical outcomes, the use of autograft tissue has drawbacks. Autogenous graft tissue is limited in supply, and its procurement significantly increases patient morbidity while also lengthening the duration of surgery.[14]

The clinical application of amniotic membrane for GTR, while fulfilling the current mechanical concept of GTR, amends it with the modern concept of biological GTR. Benefits of using this technique comprising amniotic membrane, not only maintains the structural and anatomical configuration of regenerated tissues, but also contribute to the enhancement of healing through reduction of postoperative scarring and subsequent loss of function and providing a rich source of stem cells. In line with our proposal, it has been demonstrated that amniotic membrane enhances gingival wound healing properties and reduces scarring.[15]

The use of amniotic membrane is a novelty in the dentistry field, as it reduces the drawbacks of other materials. The aim of this case series was the use of amniotic membrane in the treatment of shallow-to-moderate gingival recession defects.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of amniotic membrane

In the production of the amnion allograft used in this study, prescreened, consenting mothers donate the amnion and associated tissues during elective cesarean section surgery. All donated tissue follows strict guidelines for procurement, processing, and distribution, as dictated by the Tissue Bank, (Tata Memorial Hospital, Mumbai). These safety measures include testing for serological infectious diseases such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 1 and 2 antibodies, human T-lymphotropicvirus type 1 and 2 antibodies, hepatitis C antibody, hepatitis B surface antigen, hepatitis B core total antibody, serological test for syphilis, HIV type 1 nucleic acid test, and hepatitis C virus nucleic acid test. Upon collection of the maternal tissue, the amnion and chorion tissues are carefully separated, and the amnion is cleansed prior to processing. The allograft is terminally sterilized, dehydrated, perforated, and terminally sterilized.

Patient selection

Three systemically healthy patients, nonsmoker, with the Miller's Class II gingival recession, referred to the Department of Periodontology, Subharti Dental College and Hospital, Meerut. These patients were explained the procedure in detail and were included for the study with their consent. Selected teeth in all cases were maxillary canine.

Presurgical treatment

The patients were educated and motivated with an emphasis on proper oral hygiene maintenance. All the patients underwent the initial phase of treatment, which consisted of thorough scaling and root planing.

Measurements

All measurements were performed by one examiner. The participants were evaluated for the following clinical parameters: Recession depth (RD), recession width (RW), clinical attachment level (CAL), width of keratinized gingiva (KG) at baseline, 3 and 6 months postoperatively for isolated recession on maxillary canine. Reference point for CAL was taken from CEJ up to the base of the gingival sulcus. KG width was measured from margin of the gingiva up to the mucogingival junction.

Preoperatively, the first patient presented a 4 mm RD and 6 mm RW on left maxillary canine [Figure 1]. RD and RW measured 3.9 mm and 5.8 mm, and 3.13 mm and 5.15 mm for the second [Figure 2] and the third patient [Figure 3], respectively.

Figure 1.

Preoperative of the first patient

Figure 2.

Preoperative of the second patient

Figure 3.

Preoperative of the third patient

Preoperative measurements for CAL was 7 mm, 6 mm and 6.1 mm while KG is 3.5 mm, 3 mm, and 3 mm for the first, second, and third patient, respectively.

Surgical procedure

Measurements were recorded, and the surgical area was prepared with adequate anesthesia using 2% lignocaine hydrochloride containing 1:80,000 adrenaline.

Double papilla flap technique was employed by giving two horizontal incisions at CEJ followed by vertical incisions placed at the line angles. The releasing incision was extended into alveolar mucosa without making contact with the bone. A partial thickness pedicle flap with sufficient mesial and distal interdental papilla was raised by giving scalloped internal bevel incision. Interdental papilla was undermined while lifting the papilla gently and separating from the underlying connective tissue. It was made sure that mesial and distal papilla flaps were wider than the recipient site to cover the root and to provide a margin for attachment to the connective tissue.

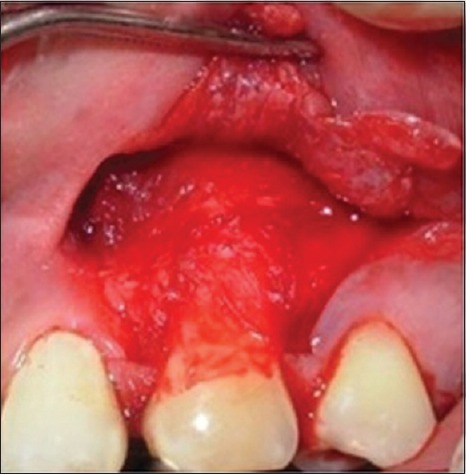

Amniotic membrane was placed on the denuded root and flap was sutured [Figure 4]. Care was taken to prevent the movement of the membrane during flap closure. Patients were advised not to brush on the treated site for 3 weeks and instead 0.2% chlorhexidine rinse was prescribed for 3 weeks. Antibiotics and analgesics were prescribed postoperatively. The patient was examined at 1st and 4th week to assess healing and then followed-up at 3 and 6 months for reassessment of clinical parameters.

Figure 4.

Placement of amniotic membrane

RESULTS

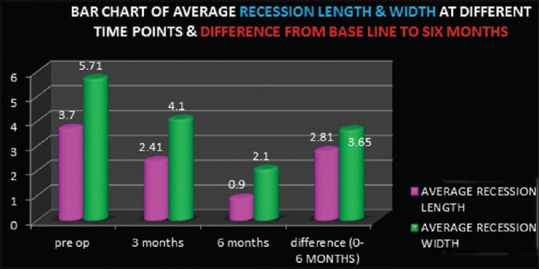

All the three patients completed the study. At the end of 6 months, statistically significant difference was found from baseline to 3 months and from 3 to 6 months [Figure 5].

Figure 5.

Bar chart of average recession length and width at baseline, 3 months, 6 months and difference from baseline to 6 months

Since at the time of study, isolated gingival recession pertaining to canine only was undertaken specifically, so recession coverage pertaining to adjacent teeth have been undertaken later.

Postoperative results at 6 months showed a decrease in RD to 1.2 mm and 2.2 mm in RW [Figure 6] for the first patient. Six months postoperatively, RD and RW in second patient decreases to 0.5 mm and 2 mm [Figure 7] while in third patient RD decreases to 1 mm while RW decreased to 2 mm [Figure 8].

Figure 6.

Six months postoperative of first patient

Figure 7.

Six months postoperative of the second patient

Figure 8.

Six months postoperative of the third patient

Clinical attachment level decreases to 4.2 mm, 2.5 mm, and 4 mm at 6 months postoperatively for the first, second, and third patient, respectively, showing a mean decrease of 2.81 ± 0.68 mm. KG increases to 6.3, 6.5 mm, 6.3 mm, and 5.13 mm for the three patients, respectively, at 6 months postoperatively, showing mean KG width increase up to 2.9 ± 0.7 mm. The mean root coverage at the end of 6 months was found 70.2 ± 6.8%.

DISCUSSION

The ultimate goal of periodontal plastic surgical procedure for recession coverage is the complete regeneration of the supporting components of the periodontium, resulting in complete coverage of the denuded root surfaces in an esthetic as well as a functional manner. Several studies have shown the effectiveness and predictability of GTR for root coverage.[16,17] Histologically, new bone and cementum with inserting fibers have been shown to form after recession coverage by GTR.[18]

Amniotic membrane as a GTR membrane consists of a single layer of epithelium cells, thin reticular fibers (basement membrane), a thick compact layer, and a fibroblast layer. The basement membrane contains collagen type III, IV, and V and cell-adhesion bioactive factors including fibronectin and laminins.[11] Of particular interest is the fact that this amnion layer possesses several types of laminins, with laminin-5 being the most prevalent. It plays a role in the cellular adhesion of gingival cells and concentrations of this glycoprotein in amniotic allograft may be useful for periodontal grafting procedures.[11]

Amnion tissue contains growth factors that may aid in the formation of granulation tissue by stimulating fibroblast growth and neovascularization.[19] In addition, the cells found within tissue exhibit characteristics associated with stem cells and may enhance clinical outcomes.[20]

Amnion has shown an ability to form an early physiologic “seal” with the host tissue precluding bacterial contamination[21] and multiple studies support amnion's ability to decrease the host immunologic response via mechanisms such as localized suppression of polymorphonuclear cell migration.[22]

Gurinsky[14] found an average increase of 3.2 mm (±1.71) of new gingival tissue representing 97% (±0.5) defect coverage in gingival recession using dehydrated amnion allograft which provides good results in terms of root coverage, increased tissue thickness, and increased attached gingival tissue. Processed dehydrated allograft amnion demonstrated excellent esthetic results in terms of texture and color match. There were no adverse reactions during the course of this study and patients reported relatively little postoperative discomfort. The ability of processed dehydrated allograft amnion to self-adhere eliminates the need for sutures, making the procedure less technically demanding and significantly decreasing surgical time. The ability to self-adhere makes processed dehydrated allograft amnion an attractive option for multi-teeth procedures and recession defects in particularly hard to reach areas like the molar region.

Velez et al.[23] showed the use of cryopreserved amniotic membrane (CAM) in helping cicatrization and wound healing after dental implant surgery. CAM supports the growth of epithelium thus facilitating migration and reinforcing adhesion.

Sheik et al.[24] studied the use of dehydrated human amniotic membrane allografts to promote healing in patients with refractory nonhealing wounds and found excellent results with no recurrence of wounds in long-term follow-up.

Nanditha et al.[25] performed a study involving clinical evaluation of the efficacy of a GTR membrane (HEALIGUIDE®) and demineralized bone matrix (OSSEOGRAFT®) as a space maintainer in the treatment of Miller's Class I gingival recession and found the mean reduction in RD from a mean value of 2.62 ± 0.45 mm preoperatively to 0.76 ± 0.59 mm 9 months postoperatively while in this study results demonstrate a highly significant reduction in RL from a mean value of 3.54 ± 0.4 mm preoperatively to a mean value of 1.63 ± 0.39 mm 6 months postoperatively.

Babu et al.[26] studied comparative evaluation of a bioabsorbable collagen membrane and SCTG in the treatment of localized gingival recession and the change in width of KG following these two procedures. Both the grafts were covered with coronally advanced flap. Six months following root coverage procedures, the mean root coverage was found to be 84.84% ±16.81% and 84.0% ±15.19% in SCTG group and GTRC group (GTR-based collagen membrane), respectively. The mean KG width increase was 1.50 ± 0.70 mm and 2.30 ± 0.67 mm in the SCTG and GTRC group, respectively, which was not statistically significant. They concluded that resorbable collagen membrane can be a reliable alternative to autogenous CTG in the treatment of gingival recession.

Shetty et al.[27] studied bilateral multiple recession coverage with platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) in comparison with amniotic membrane. Both the recessions were planned for root coverage with coronally advanced flap and additive membrane. They found that the clinical outcome of the surgical procedure accounted for 100% root coverage, an enhanced gingival biotype, with both the membranes. Furthermore, the results were stable even after 7 months in the amniotic membrane-treated site. Hence, the use of amniotic membrane as a novel approach to root coverage is more advantageous than PRF owing to the laboratory preparation of the autologous biomaterial and use of the amniotic membrane as an additive material alternate to subepithelial connective tissue in reducing the need for a second surgical site is better advocated.

Owing to results in this study, amniotic membrane can be a reliable alternative to autogenous CTG in the treatment of gingival recession for, the former eliminates donor site morbidity, reduces the need for multiple surgeries and expense, saves time that would be required for harvesting a CTG, and offers unlimited graft availability of uniform thickness. Although this case series provides initially promising results for utilization of processed dehydrated allograft amnion in particular mucogingival defects, the limited number of patients, lack of controls, lack of maintaining oral hygiene status, and short duration of this study, results were not comparable to other studies. To confirm the use of amniotic membrane as a good alternative for treatment of gingival recession, more longitudinal studies are required in this field of periodontal plastic surgery.

CONCLUSION

Amniotic membrane provides an effective alternative to autograft tissue in the treatment of shallow-to-moderate Miller's Class I and II recession defects. In addition, the self-adherent nature of the amniotic membrane significantly reduced surgical time, easier to perform relative to other techniques. The results obtained in this study could be taken as indirect evidence of new attachment formation. Since alveolar bone and periodontal ligament formation is a process that requires several months, the improvement in CAL and pocket probing depth could be noticed up to the stage at which new tissue formation occurred. Further research and long-term clinical trials investigating the full potential of this potential stem reservoir are still warranted to strengthen the fact that amniotic membrane is indeed a reservoir for regeneration and repair.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors extend their sincere appreciation to Dr. Astrid Lobo Gajiwala, Head (Tissue Bank), Tata Memorial Hospital, Tissue Bank, Dr. E. Borges Road, Parel (Mumbai – 400 012) for providing amniotic membrane.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahathya RS, Deepalakshmi D, Ramakrishnan T, Ambalavanan N, Emmadi P. Subepithelial connective tissue grafts for the coverage of denuded root surfaces: A clinical report. Indian J Dent Res. 2008;19:134–40. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.40468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saygun I, Karacay S, Ozdemir A, Sagdic D. Multidisciplinary treatment approach for the localized gingival recession: A case report. Turk J Med Sci. 2005;35:57–63. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller PD., Jr Regenerative and reconstructive periodontal plastic surgery. Mucogingival surgery. Dent Clin North Am. 1988;32:287–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grupe HE, Warren RF. Repair of gingival defects by a sliding flap operation. J Periodontol. 1956;27:92–5. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Langer B, Langer L. Subepithelial connective tissue graft technique for root coverage. J Periodontol. 1985;56:715–20. doi: 10.1902/jop.1985.56.12.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wennström JL. Mucogingival therapy. Ann Periodontol. 1996;1:671–701. doi: 10.1902/annals.1996.1.1.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Majzoub Z, Landi L, Grusovin MG, Cordioli G. Histology of connective tissue graft. A case report. J Periodontol. 2001;72:1607–15. doi: 10.1902/jop.2001.72.11.1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tinti C, Vincenzi GP. The treatment of gingival recession with “guided tissue regeneration” procedure by means of Gore-Tex membrane. Quintessence Int. 1990;6:465–8. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Naughton GK. From lab bench to market: Critical issues in tissue engineering. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;961:372–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb03127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diño BR, Eufemio G, De Villa M, Reysio-Cruz M, Jurado RA. The use of fetal membrane homografts in the local management of burns. J Philipp Med Assoc. 1965;41(Suppl):890–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pakkala T, Virtanen I, Oksanen J, Jones JC, Hormia M. Function of laminins and laminin-binding integrins in gingival epithelial cell adhesion. J Periodontol. 2002;73:709–19. doi: 10.1902/jop.2002.73.7.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koizumi NJ, Inatomi TJ, Sotozono CJ, Fullwood NJ, Quantock AJ, Kinoshita S. Growth factor mRNA and protein in preserved human amniotic membrane. Curr Eye Res. 2000;20:173–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang LH, Neiva RE, Soehren SE, Giannobile WV, Wang HL. The effect of platelet-rich plasma on the coronally advanced flap root coverage procedure: A pilot human trial. J Periodontol. 2005;76:1768–77. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.10.1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gurinsky B. A novel dehydrated amnion allograft for use in the treatment of gingival recession: An observational case series. J Impact Adv Clin Dent. 2009;1:65–73. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rinastiti M, Harijadi, Santoso AL, Sosroseno W. Histological evaluation of rabbit gingival wound healing transplanted with human amniotic membrane. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;35:247–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2005.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nevins ML. Aesthetic and regenerative oral plastic surgery: Clinical applications in tissue engineering. Dent Today. 2006;25(142):144–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harris RJ. Gingival augmentation with an acellular dermal matrix: Human histologic evaluation of a case – Placement of the graft on periosteum. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2004;24:378–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gottlow J, Karring T, Nyman S. Guided tissue regeneration following treatment of recession-type defects in the monkey. J Periodontol. 1990;61:680–5. doi: 10.1902/jop.1990.61.11.680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takashima S, Yasuo M, Sanzen N, Sekiguchi K, Okabe M, Yoshida T, et al. Characterization of laminin isoforms in human amnion. Tissue Cell. 2008;40:75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.tice.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Toda A, Okabe M, Yoshida T, Nikaido T. The potential of amniotic membrane/amnion-derived cells for regeneration of various tissues. J Pharmacol Sci. 2007;105:215–28. doi: 10.1254/jphs.cr0070034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Talmi YP, Sigler L, Inge E, Finkelstein Y, Zohar Y. Antibacterial properties of human amniotic membranes. Placenta. 1991;12:285–8. doi: 10.1016/0143-4004(91)90010-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hao Y, Ma DH, Hwang DG, Kim WS, Zhang F. Identification of antiangiogenic and antiinflammatory proteins in human amniotic membrane. Cornea. 2000;19:348–52. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200005000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Velez I, Parker WB, Siegel MA, Hernandez M. Cryopreserved amniotic membrane for modulation of periodontal soft tissue healing: A pilot study. J Periodontol. 2010;81:1797–804. doi: 10.1902/jop.2010.100060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sheikh ES, Sheikh ES, Fetterolf DE. Use of dehydrated human amniotic membrane allografts to promote healing in patients with refractory non healing wounds. Int Wound J. 2014;11:711–7. doi: 10.1111/iwj.12035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nanditha S, Priya MS, Sabitha S, Arun KV, Avaneendra T. Clinical evaluation of the efficacy of a GTR membrane (HEALIGUIDE) and demineralised bone matrix (OSSEOGRAFT) as a space maintainer in the treatment of Miller's Class I gingival recession. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2011;15:156–60. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.84386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Babu HM, Gujjari SK, Prasad D, Sehgal PK, Srinivasan A. Comparative evaluation of a bioabsorbable collagen membrane and connective tissue graft in the treatment of localized gingival recession: A clinical study. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2011;15:353–8. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.92569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shetty SS, Chatterjee A, Bose S. Bilateral multiple recession coverage with platelet-rich fibrin in comparison with amniotic membrane. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2014;18:102–6. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.128261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]