Abstract

A plethora of vascular pathologies is associated with inflammation, hypoxia and elevated rates of reactive species generation. A critical source of these reactive species is the purine catabolizing enzyme xanthine oxidoreductase (XOR) as numerous reports over the past 30 years have demonstrated XOR inhibition to be salutary. Despite this long standing association between increased vascular XOR activity and negative clinical outcomes, recent reports reveal a new paradigm whereby the enzymatic activity of XOR mediates beneficial outcomes by catalyzing the one electron reduction of nitrite (NO2−) to nitrite oxide (•NO) when NO2− and/or nitrate (NO3−) levels are enhanced either via dietary or pharmacologic means. These observations seemingly countervail numerous reports of improved outcomes in similar models upon XOR inhibition in the absence of NO2− treatment affirming the need for a more clear understanding of the mechanisms underpinning the product identity of XOR. To establish the micro-environmental conditions requisite for in vivo XOR-catalyzed oxidant and •NO production, this review assesses the impact of pH, O2 tension, enzyme-endothelial interactions, substrate concentrations and catalytic differences between xanthine oxidase (XO) and xanthine dehydrogenase (XDH). As such, it reveals critical information necessary to distinguish if pursuit of NO2− supplementation will afford greater benefit than inhibition strategies and thus enhance the efficacy of current approaches to treat vascular pathology.

Keywords: nitrite, xanthine oxidoreductase, nitric oxide, oxygen tension, inflammation, hypoxia

Introduction

In primates, the molybdopterin-flavin enzyme xanthine oxidoreductase (XOR) catalyzes the final steps in purine catabolism; oxidation of hypoxanthine to xanthine and xanthine to uric acid. Although XOR is reported to be expressed in numerous human tissues including the lung, kidney and myocardium, the greatest XOR specific activity is localized in the splanchnic system [1]. Several inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IFN-γ) as well as hypoxia are noted to induce XOR expression. In particular, vascular endothelial cells respond to hypoxia, cytokine stimulation and shear stress by upregulating XOR and exporting the enzyme to the circulation [1,2]. Structurally, XOR is a 295 kD homodimer with each subunit composed of four redox centers: a molybdopterin cofactor (Mo-co), a flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) and two iron-sulfur centers (Fe/S). The Mo-co is comprised of a pterin derivative and one Mo atom which is pentacoordinated with a dithiolene, two oxygen atoms and a sulfur atom. The Mo-co is the site of hypoxanthine and xanthine oxidation whereas NAD+ and O2 reduction occur at the FAD. The two Fe/S clusters provide the conduit for electron flux between the Mo-co and the FAD. Distinguishable by their specific electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectra, these Fe/S centers are both of the ferredoxin type but are not identical [3–5].

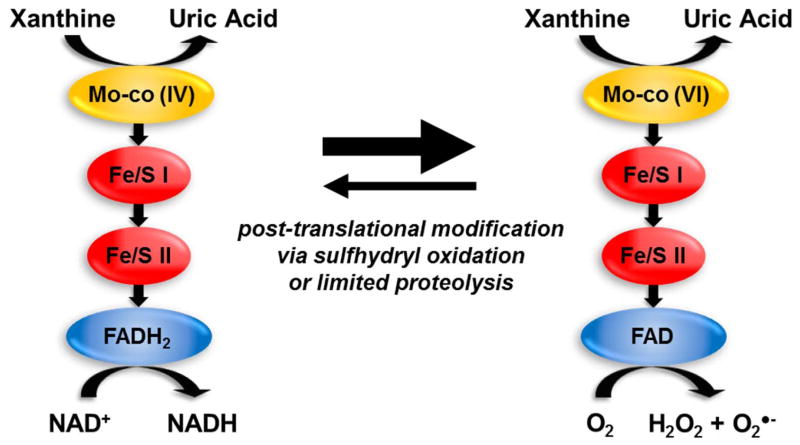

Xanthine oxidoreductase is transcribed as xanthine dehydrogenase (XDH) where its substrate-derived electrons reduce NAD+ to NADH, Fig. 1. However, during hypoxia/inflammation, reversible oxidation of critical cysteine residues (535 and 992) and/or limited proteolysis converts XDH to xanthine oxidase (XO) [6]. In the oxidase form, affinity for NAD+ at the FAD is greatly diminished while affinity for oxygen is enhanced resulting in univalent and divalent electron transfer to O2 to generate O2•− and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), respectively, Fig. 1 [7]. Therefore, when situated at critical sites in the tissue and vasculature, XO can serve as an abundant source of ROS mediating alterations in vascular function by reducing •NO bioavailability via direct reaction with O2•− (•NO + O2•− → ONOO−) or indirectly, by mediating redox-dependent cell signaling reactions [8–10].

Figure 1. Xanthine Oxidoreductase Reactions.

For XDH, xanthine is oxidized to uric acid at the Mo-co and electrons transferred via 2 Fe/S centers to the FAD where NAD+ is reduced to NADH (left). For XO, xanthine is oxidized to uric acid at the Mo-co and electrons are transferred to the FAD where O2 is reduced to O2•− and H2O2 (right). Conversion from XDH to XO is mediated by post-translational modification.

Oxidant Formation

In the literature XO is rarely recognized as a direct source of H2O2 and mainly referred to as a source of O2•− with H2O2 formation resulting from reaction of O2•− with superoxide dismutase (SOD) or spontaneous dismutation. However, XO is actually a H2O2-producing enzyme that also produces some O2•− under physiological conditions. For example, achievement of 100% O2•− production from XO requires 100% O2 and pH 10 whereas at pH 7.0 and 21% O2, XO generates ~25% O2•− and ~75% H2O2 [11]. At normal pH and hypoxia, XO-catalyzed H2O2 increases approaching 90–95% of total electron flux though the enzyme [12]. Thus, under conditions such as ischemia and/or hypoxia, where both O2 tension and pH are reduced, H2O2 formation is favored suggesting that XOR may participate in the numerous signaling cascades where H2O2 has been implicated [13,14]. While the post-translational conversion of XDH to XO has become synonymous with the conversion from a “good” housekeeping enzyme to a “bad” ROS-producing enzyme, it is critical to recognize that XDH can also reduce O2 and generate ROS. For example, ischemia/hypoxia either localized, regional or systemic mediate O2-dependent alterations in cellular respiration leading to decreased mitochondrial NADH oxidation and thus significant decreases NAD+ concentration [15]. Although NAD+ is the preferred electron acceptor for XDH, when levels of this substrate are low XDH will utilize O2 and thus care should be taken not to exclusively associate XDH as the form of XOR that does not produce ROS [16]. In the aggregate, XO is primarily a source of H2O2 that also produces O2•− while, under certain circumstances, both forms of the enzyme are capable of producing oxidants.

XOR-Endothelium Interaction

Intravenous administration of heparin in the clinic and in animal models of vascular disease results in elevated XO activity in the plasma suggesting XO is bound to the vascular endothelium [17–19]. During ischemic/hypoxic conditions XDH released into the circulation is rapidly (<1 min) converted to XO and subsequently binds to negatively charged glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) on the surface of endothelial cells [18,20]. Although XO exhibits a net negative charge at physiological pH, pockets of cationic amino acid motifs on the surface of the protein confer high affinity for GAGs (Kd = 6 nM) [18,21–23]. Sequestration of XO by vascular endothelial GAGs amplifies local XO concentration and significantly alters XO kinetic properties. For example, when compared to XO in free in solution, GAG-immobilized XO demonstrates an increased Km for xanthine (6.5 vs. 21.2 μM) and an increased Ki for allo/oxypurinol (85 vs. 451 nM) [23]. In addition to affecting kinetic properties at the Mo-co, binding of XO to GAGs confers alterations to the FAD resulting in reduction of O2•− production by 34% and thus elevation of H2O2 formation [23]. Combined, XO-GAG interaction results in: 1) diminished affinity for hypoxanthine/xanthine, 2) resistance to inhibition by the pyrazalopyrimidine-based inhibitors allo/oxypurinol and 3) diminished O2•− production and thus enhanced H2O2 generation. This vascular milieu where XO is sequestered on the surface of the endothelium is prime for prolonged enhancement of oxidant formation that is partially resistant to inhibition by the most commonly prescribed clinical agents.

Nitrite Reductase Activity

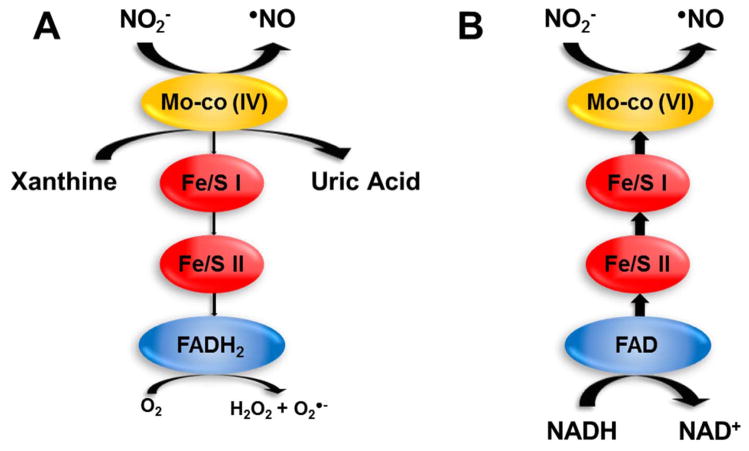

For over 40 years, dogma dictates that elevation of XO activity during hypoxia/ischemia/inflammation equates to increased XO-derived ROS generation and ultimately to poor clinical outcomes. However, recent reports have proposed a paradigm shift by demonstrating XO-mediated formation of salutary •NO under similar pathologic conditions. Indeed, under anoxic conditions and acidic pH, XO demonstrates a nitrite reductase activity by catalyzing the reduction of NO2− to •NO in the presence of either xanthine or NADH as reducing substrates (sources of electrons) [24–27]. The Mo-co has been identified as the site of NO2− reduction where xanthine oxidation directly reduces the cofactor; alternatively, NADH can indirectly provide reducing equivalents via electron donation at the FAD with subsequent retrograde flow to the Mo-co, Fig. 2. This catalytic activity has also been demonstrated is tissue homogenates in the presence of xanthine or aldehyde [28]. In addition to in vitro/ex vivo biochemical studies, diminution or ablation of NO2−-mediated beneficial effects upon co-treatment with allo/oxypurinol has been observed in vivo suggesting XOR involvement as a NO2− reductase. For example, XOR inhibition has diminished protective effects mediated by NO2− therapy both clinically and in animal models of intimal hyperplasia following vessel injury [29], acute lung injury and ventilator-induced pulmonary pathology [30,31], ischemia/reperfusion (I/R)-induced damage in lung transplantation [32], pulmonary hypertension [33], myocardial infarction [34] and renal [35], cardiac [36] and liver [37] I/R injury. It is also important to note that circulating NO2− concentration and subsequent •NO levels may be enhanced in an XOR-dependent manner by supplemental nitrate (NO3−). In this case it is hypothesized that XOR serves first as a NO3− reductase (NO3− + 1e− → NO2−) and ultimately a NO2− reductase (NO2− + 1e− → •NO) [38]. In these experiments, germ-free mice, void of bacterial NO3− reductases, were treated with NaNO3−. While NO3− treatment resulted in elevation of plasma NO2− levels it was not seen when mice received co-treatment with allopurinol and thus is consistent with previous biochemical reports demonstrating NO3− reductase activity for XOR [39]. Taken together, these recent reports serve to promote a new paradigm where XOR, in the presence of supplemental NO2− or NO3−, may adopt a protective role under conditions where it was previously assumed that inhibition therapy would provide optimal benefit.

Figure 2. Nitrite Reductase Activity of XOR.

(A) Under low O2 tensions, NO2− undergoes a 1 electron reduction to •NO at the Mo-cofactor (electrons are donated directly to Mo by xanthine). The thickness of the arrows represents the degree of electron flux while the size of the font represents level of substrate or product formation. (B) Again, under low O2 tensions, NO2− is reduced to •NO at the Mo-cofactor while electrons are supplied by NADH and transferred retrograde to reduce the Mo-co.

While the concept of XOR-derived •NO formation is enticing, it is remains underdeveloped for several reasons: 1) in vitro demonstration of •NO formation from XOR and NO2− has required anoxic conditions and concentrations of NO2− several orders of magnitude greater than those encountered in vivo, 2) other mechanisms for hypoxic and acidic reduction of NO2− to •NO including heme-based reactions [40–42] have not been clearly delineated from XO-mediated effects 3) reports have relied upon inhibition of XOR with allo/oxypurinol, an inhibitor known to have off target effects on alternative purine catabolism pathways including those affecting adenosine [43,44] or 4) by systemic molybdopterin enzyme inactivation by dietary supplementation with sodium tungstate (NaW), a process that mediates the replacement of the active site Mo with tungsten (W) rendering XOR as well as aldehyde oxidase (AO), sulfite oxidase (SO) and mitochondrial amidoxime reducing component or mARC inactive [45,46]. This is crucial as the molybdopterin enzymes AO, SO and mARC have also been reported to demonstrate NO2− reductase activity [47–50]. In toto, these issues reveal a current state of uncertainty regarding the biological relevance of XO-mediated •NO formation. The following will address these issues and generate a working hypothesis focused on a micro-environmental setting where XO-catalyzed NO2− reduction may be operative.

A significant obstacle to assessing of the biological relevance of XO-mediated •NO formation is the substantive difference in affinity between hypoxanthine/xanthine (Km = 6.5 μM) and NO2− (Km = 2.5 mM) for the Mo-co of XO [7,26]. At first glance it would be appropriate to conclude this reaction would never occur due to: 1) the vast difference in Km values and 2) normal tissue NO2− concentration (~0.3 μM) is greater than an order of magnitude lower than the Km-NO2− and 3) hypoxia results in diminution of NO2− levels [51]. However, hypoxia enhances NO3− levels from 30–40 μM to 120–150 μM depending upon the tissue [51]. This increase in NO3− is not trivial as reports indicate XOR-dependent reduction of organic NO3− to NO2− and then to •NO with Km values ranging from 330–500 μM for glycerol trinitrate (GTN) to 32 mM for inorganic nitrate (NaNO3) [52,53]. On the other hand, the Km for xanthine is 6.5 μM and levels of xanthine above 20 μM, commonly seen under pathologic conditions, are reported to induce substrate-dependent inhibition of NO2− reduction (Ki = 55 μM) [26, 54–56]. Therefore, when assessed together, it would seem that the potential to encounter a scenario whereby reduction in xanthine concentration and elevation in NO2− + NO3− levels would overcome the difference in Km for the Mo-co is, at best, improbable. However, it can be hypothesized that NADH, not hypoxanthine/xanthine, may be the major source of electrons necessary to reduce the Mo-co and drive NO2− reduction. Under ischemia or hypoxia, O2-dependent alterations in cellular respiration lead to decreased mitochondrial NADH oxidation and thus significant elevation of NADH concentration [15]. Enhancement of NADH levels may serve to efficiently reduce the Mo-co via retrograde electron flow from the FAD, Fig. 2. This process would also impact affinity of xanthine at the Mo-co as xanthine-Mo-co reaction is dependent on the Mo-co being oxidized. In addition, immobilization of XO on GAGs confers a diminution in affinity for xanthine (see above) which could further facilitate capacity for NO2− + NO3− to compete for reaction. Regardless of the potential shifts in affinity away from xanthine and towards NO2−, it remains unclear how such vast differences in Km values can be surmounted to generate operative NO2− reductase activity from XO.

Another obstacle to the assessment of the biological relevance of XO-mediated •NO formation is oxygen tension. Nitrite reductase activity of XO is extremely oxygen sensitive [24,58]. This is primarily due to oxidation of the Mo-co via O2-dependent electron withdrawal at the FAD. Therefore, the presence of O2 results in a more electron deficient Mo-co resulting in lower capacity to donate an electron to NO2− (this concept is extensively reviewed [59]). The O2 tension whereby the NO2− reductase activity of XOR may become effective is ultimately kinetically governed at the FAD cofactor. First, one must consider that O2 tensions must drop to or below Km for O2 at the FAD (27 μM or ~2% O2) in order to diminish inhibitory actions of O2 and thus facilitate NO2− reaction at the Mo-co [59]. Second, local NADH levels must be considered as hypoxia-mediated elevation in NADH can serve to provide competition for O2 at the FAD while concomitantly reducing the enzyme, Fig. 2. Third, pH is also crucial as hypoxanthine and xanthine oxidation at the Mo-co is a base-catalyzed process with a pH optimum of 8.9 [11]. The reduction of NO2− at the Mo-co is an acid-catalyzed process with a pH optimum of (6–6.5) [24]. Considering in vivo vascular microenvironments encountered during inflammatory conditions demonstrate pH’s that fall below 7.0, it is logical to assume that this setting would shift affinity away from xanthine and towards NO2− reaction at the Mo-co. This concept was observed when pH was sequentially lowered from 8.0→5.0 while using either NADH or xanthine as reducing substrates [58]. Thus, the combination of low O2 tension, elevated NADH concentration and lower pH is conducive for XO-catalyzed NO2− formation. However, it must be considered that XDH and not XO may be the major XOR isoform driving NO2− reduction as the Km O2 for the FAD of XDH is 260 μM versus 27 μM for XO suggesting O2-mediated inhibition would be insignificant for XDH [3,60].

Regardless of the recognized biochemical obstacles for XOR-derived •NO formation in purified enzyme preparations, the in vivo impact of NO2− supplementation has demonstrated significant XO dependence. For example, XOR inhibition has diminished or abolished salutary actions of NO2− therapy in a variety of vascular models including wire-induced vessel injury, lung injury, ischemia/reperfusion, pulmonary hypertension, myocardial infarction [29–37]. These studies have utilized varied pharmacologic approaches to diminish XO enzymatic activity including allo/oxypurinol, febuxostat and dietary supplementation with NaW (sodium tungstate) which serves to strengthen the argument for XO-dependent NO2− reduction to •NO as the central mechanism driving beneficial outcomes. In addition to NO formation, the presence of NO2− serves to “inhibit” XO-derived reactive species formation by diverting electrons destined for O2 reduction to •NO generation and effectively providing a 2-fold beneficial impact (see Fig. 2). However, administration of NO2− is not uniform among all reports and must be further studied to optimize the beneficial impact while avoiding the potential for adventitious nitrosamine formation. This is especially relevant in the stomach where acid pH can facilitate the formation of these carcinogenic compounds. Future in vivo studies will not only define these optimal NO2− doses but reveal the potential for utilizing the enzymatic activity of XO, upregulated by inflammatory/hypoxic processes, to be quite promising.

Summary

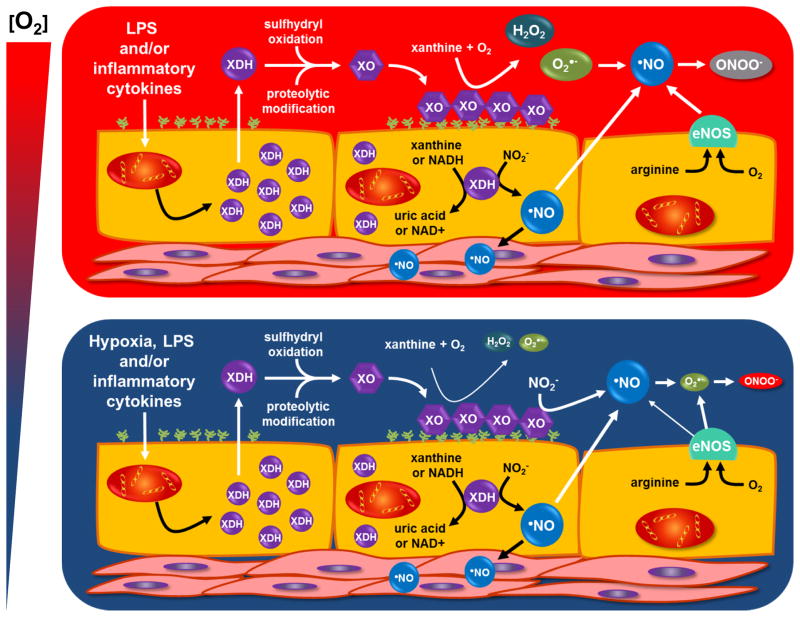

Consideration of XOR as a significant source of •NO during ischemic/hypoxic conditions seems to countervail studies reporting XOR inhibition resulting in a reduction in symptoms and enhanced function. In addition, several substantive biochemical issues frustrate the designation of XOR as a biologically relevant source of •NO. Yet, in vivo XOR inhibition studies were not conducted in models where NO2− levels were elevated and in vitro biochemical studies have not considered all possible permutations, especially XO vs. XDH, whereby Mo-co and FAD kinetics may be altered to favor NO2− reduction. Herein, we have discussed several key factors (acidic pH, elevated levels of NADH, O2 tension, immobilization-induced kinetic alterations and enzyme isoform) that contribute to a local milieu where XOR-mediated NO2− reduction may be relevant. A summary of our working hypothesis is represented in cartoon format, Fig. 3. Inflammatory conditions in the absence of hypoxia result in enhanced XDH expression and export to the circulation where XDH is rapidly converted to XO with subsequent sequestration by endothelial GAGs either locally or in a distal vascular beds. With abundant O2 and xanthine, XO-dependent ROS formation is dominant while eNOS is the primary source of •NO. Under these conditions it is possible that, in the presence of elevated NO2−, intracellular XDH could serve as a nitrite reductase. As tissue O2 concentrations decrease, approaching and falling below the Km for O2 at the FAD (~27 μM or ~1.5% O2), XO as well as XDH can assume NO2− reductase activity while eNOS-mediated O2 formation is blunted by lack of requisite substrate (O2) and may become uncoupled resulting in O2•− generation. At this point XO and/or XDH may become a significant source of •NO. It is interesting to note that the Km O2 for eNOS is 23 μM; a value very similar to the Km O2 for XO (27 μM) and thus may represent the O2 tension where •NO production is transferred from eNOS to XOR [61]. The degree to which this hypothesis is accurate remains unclear; however, it is clear that further investigation is warranted to more precisely define the mechanisms underpinning XOR-mediated •NO formation and the potential impact this process may have on therapeutic strategies to address vascular disease.

Figure 3. XOR-Catalyzed NO Production in the Vasculature.

(top panel) Under oxygenated conditions, inflammation results in enhanced XDH expression and export to the circulation where XDH is rapidly converted to XO with subsequent sequestration by endothelial GAGs. With abundant O2 and xanthine, XO-dependent ROS formation is dominant while eNOS is the primary source of •NO. XO-derived O2•− effectively reduces •NO bioavailability by its diffusion limited reaction with eNOS-derived •NO to form peroxynitrite (O=NOO−). Under these conditions it is possible that, in the presence of elevated NO2−, intracellular XDH could serve as a NO2− reductase. (bottom panel) Under hypoxic conditions (O2 tensions approaching and falling below the Km for O2 at the FAD (~27 μM or ~1.5% O2), XO as well as XDH can assume NO2− reductase activity while eNOS-mediated •NO formation is diminished due to the absence of the substrate, O2 (noted by a diminished arrow thickness). Under these conditions, eNOS may become uncoupled resulting in O2•− generation. It is at this point that XO and/or XDH may become a significant source of •NO.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, NHLBI (1RO1HL121155) and by a University of Pittsburgh, Department of Anesthesiology Grant. Nadia Cantu-Medellin is thanked for her assistance in graphic design.

Abbreviations

- GAGs

glycosaminoglycans

- GTN

glycerol trinitrate

- H2O2

hydrogen peroxide

- •NO

nitric oxide

- NOS

nitric oxide synthase

- O2•

superoxide

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SOD

superoxide dismutase

- XDH

xanthine dehydrogenase

- XO

xanthine oxidase

- XOR

xanthine oxidoreductase

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Harrison R. Structure and function of xanthine oxidoreductase: where are we now? Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;33(6):774–97. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00956-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kelley EE, Hock T, Khoo NK, Richardson GR, Johnson KK, Powell PC, et al. Moderate hypoxia induces xanthine oxidoreductase activity in arterial endothelial cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;40(6):952–9. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Enroth C, Eger BT, Okamoto K, Nishino T, Nishino T, Pai EF. Crystal structures of bovine milk xanthine dehydrogenase and xanthine oxidase: Structure-based mechanism of conversion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(20):10723–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.20.10723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nishino T, Okamoto K. The role of the [2Fe-2s] cluster centers in xanthine oxidoreductase. J Inorg Biochem. 2000;82(1–4):43–9. doi: 10.1016/s0162-0134(00)00165-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iwasaki T, Okamoto K, Nishino T, Mizushima J, Hori H. Sequence motif-specific assignment of two [2Fe-2S] clusters in rat xanthine oxidoreductase studied by site-directed mutagenesis. J Biochem. 2000;127(5):771–8. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parks DA, Skinner KA, Tan S, Skinner HB. Xanthine oxidase in biology and medicine. In: Gilbert DL, Colton CA, editors. Reactive oxygen species in biological systems. New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum; 1999. pp. 397–420. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harris CM, Massey V. The Oxidative Half-reaction of Xanthine Dehydrogenase with NAD; Reaction Kinetics and Steady-state Mechanism. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(45):28335–41. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.45.28335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aslan M, Freeman BA. Oxidant-mediated impairment of nitric oxide signaling in sickle cell disease--mechanisms and consequences. Cell Mol Biol. 2004;50(1):95–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aslan M, Ryan TM, Adler B, Townes TM, Parks DA, Thompson JA, et al. Oxygen radical inhibition of nitric oxide-dependent vascular function in sickle cell disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(26):15215–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.221292098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Butler R, Morris AD, Belch JJ, Hill A, Struthers AD. Allopurinol normalizes endothelial dysfunction in type 2 diabetics with mild hypertension. Hypertension. 2000;35:746–751. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.35.3.746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fridovich I. Quantitative aspects of the production of superoxide anion radical by milk xanthine oxidase. J Biol Chem. 1970;245(16):4053–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kelley EE, Khoo NK, Hundley NJ, Malik UZ, Freeman BA, Tarpey MM. Hydrogen peroxide is the major oxidant product of xanthine oxidase. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;48(4):493–8. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stone JR, Yang S. Hydrogen peroxide: a signaling messenger. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8(3–4):243–70. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Veal EA, Day AM, Morgan BA. Hydrogen Peroxide Sensing and Signaling. Molecular Cell. 2007;26(1):1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou L, Stanley WC, Saidel GM, Yu X, Cabrera ME. Regulation of lactate production at the onset of ischaemia is independent of mitochondrial NADH/NAD+: insights from in silico studies. J Physiol. 2005;569(Pt 3):925–37. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.093146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harris CM, Massey V. The reaction of reduced xanthine dehydrogenase with molecular oxygen. Reaction kinetics and measurement of superoxide radical. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(13):8370–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.13.8370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Granell S, Gironella M, Bulbena O, Panes J, Mauri M, Sabater L, et al. Heparin mobilizes xanthine oxidase and induces lung inflammation in acute pancreatitis. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(2):525–30. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000049948.64660.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Houston M, Estevez A, Chumley P, Aslan M, Marklund S, Parks DA, et al. Binding of xanthine oxidase to vascular endothelium. Kinetic characterization and oxidative impairment of nitric oxide-dependent signaling. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(8):4985–94. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.8.4985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Landmesser U, Spiekermann S, Dikalov S, Tatge H, Wilke R, Kohler C, et al. Vascular oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction in patients with chronic heart failure: role of xanthine-oxidase and extracellular superoxide dismutase. Circulation. 2002;106(24):3073–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000041431.57222.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parks DA, Williams TK, Beckman JS. Conversion of xanthine dehydrogenase to oxidase in ischemic rat intestine: a reevaluation. Am J Physiol. 1988;254(5 Pt 1):G768–74. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1988.254.5.G768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fukushima T, Adachi T, Hirano K. The heparin-binding site of human xanthine oxidase. Biol Pharm Bull. 1995;18(1):156–8. doi: 10.1248/bpb.18.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adachi T, Fukushima T, Usami Y, Hirano K. Binding of human xanthine oxidase to sulphated glycosaminoglycans on the endothelial-cell surface. Biochem J. 1993;289(Pt 2):523–7. doi: 10.1042/bj2890523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kelley EE, Trostchansky A, Rubbo H, Freeman BA, Radi R, Tarpey MM. Binding of xanthine oxidase to glycosaminoglycans limits inhibition by oxypurinol. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(36):37231–4. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402077200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Godber BLJ, Doel JJ, Sapkota GP, Blake DR, Stevens CR, Eisenthal R, et al. Reduction of nitrite to nitric oxide catalyzed by xanthine oxidoreductase. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(11):7757–63. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.11.7757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Millar TM, Stevens CR, Benjamin N, Eisenthal R, Harrison R, Blake DR. Xanthine oxidoreductase catalyses the reduction of nitrates and nitrite to nitric oxide under hypoxic conditions. FEBS Lett. 1998;427(2):225–8. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00430-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li H, Samouilov A, Liu X, Zweier JL. Characterization of the magnitude and kinetics of xanthine oxidase-catalyzed nitrite reduction. Evaluation of its role in nitric oxide generation in anoxic tissues. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(27):24482–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011648200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maia LB, Moura JJ. Nitrite reduction by xanthine oxidase family enzymes: a new class of nitrite reductases. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2011;16(3):443–60. doi: 10.1007/s00775-010-0741-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li H, Cui H, Kundu TK, Alzawahra W, Zweier JL. Nitric oxide production from nitrite occurs primarily in tissues not in the blood: critical role of xanthine oxidase and aldehyde oxidase. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(26):17855–63. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801785200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alef MJ, Vallabhaneni R, Carchman E, Morris SM, Jr, Shiva S, Wang Y, et al. Nitrite-generated NO circumvents dysregulated arginine/NOS signaling to protect against intimal hyperplasia in Sprague-Dawley rats. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(4):1646–56. doi: 10.1172/JCI44079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Samal AA, Honavar J, Brandon A, Bradley KM, Doran S, Liu Y, et al. Administration of nitrite after chlorine gas exposure prevents lung injury: Effect of administration modality. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;53(7):1431–9. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pickerodt PA, Emery MJ, Zarndt R, Martin W, Francis RC, Boemke W, et al. Sodium nitrite mitigates ventilator-induced lung injury in rats. Anesthesiology. 2012;117(3):592–601. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182655f80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sugimoto R, Okamoto T, Nakao A, Zhan J, Wang Y, Kohmoto J, et al. Nitrite reduces acute lung injury and improves survival in a rat lung transplantation model. Am J Transplant. 2012;12(11):2938–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zuckerbraun BS, Shiva S, Ifedigbo E, Mathier MA, Mollen KP, Rao J, et al. Nitrite potently inhibits hypoxic and inflammatory pulmonary arterial hypertension and smooth muscle proliferation via xanthine oxidoreductase-dependent nitric oxide generation. Circulation. 2010;121(1):98–109. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.891077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baker JE, Su J, Fu X, Hsu A, Gross GJ, Tweddell JS, et al. Nitrite confers protection against myocardial infarction: role of xanthine oxidoreductase, NADPH oxidase and K(ATP) channels. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;43(4):437–44. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.07.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tripatara P, Patel NS, Webb A, Rathod K, Lecomte FM, Mazzon E, et al. Nitrite-derived nitric oxide protects the rat kidney against ischemia/reperfusion injury in vivo: role for xanthine oxidoreductase. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18(2):570–80. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006050450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Webb A, Bond R, McLean P, Uppal R, Benjamin N, Ahluwalia A. Reduction of nitrite to nitric oxide during ischemia protects against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004 Sep 14;101(37):13683–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402927101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lu P, Liu F, Yao Z, Wang CY, Chen DD, Tian Y, et al. Nitrite-derived nitric oxide by xanthine oxidoreductase protects the liver against ischemia-reperfusion injury. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2005;4(3):350–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang L, Borniquel S, Lundberg JO. Enhanced xanthine oxidoreductase expression and tissue nitrate reduction in germ free mice. Nitric Oxide. 2010;22(2):191–5. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Millar TM, Stevens CR, Benjamin N, Eisenthal R, Harrison R, Blake DR. Xanthine oxidoreductase catalyses the reduction of nitrates and nitrite to nitric oxide under hypoxic conditions. FEBS Lett. 1998;427(2):225–8. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00430-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vitturi DA, Patel RP. Current perspectives and challenges in understanding the role of nitrite as an integral player in nitric oxide biology and therapy. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;51(4):805–12. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bueno M, Wang J, Mora AL, Gladwin MT. Nitrite signaling in pulmonary hypertension: mechanisms of bioactivation, signaling, and therapeutics. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2012;18(14):1797–809. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weitzberg E, Hezel M, Lundberg JO. Nitrate-nitrite-nitric oxide pathway: implications for anesthesiology and intensive care. Anesthesiology. 2010;113(6):1460–75. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181fcf3cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Takano Y, Hase-Aoki K, Horiuchi H, Zhao L, Kasahara Y, Kondo S, et al. Selectivity of febuxostat, a novel non-purine inhibitor of xanthine oxidase/xanthine dehydrogenase. Life Sci. 2005;76(16):1835–47. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Becker MA, Schumacher HR, Jr, Wortmann RL, MacDonald PA, Eustace D, Palo WA, et al. Febuxostat compared with allopurinol in patients with hyperuricemia and gout. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(23):2450–61. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hille R, Nishino T, Bittner F. Molybdenum enzymes in higher organisms. Coord Chem Rev. 2011;255(9–10):1179–205. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.11.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Havemeyer A, Bittner F, Wollers S, Mendel R, Kunze T, Clement B. Identification of the missing component in the mitochondrial benzamidoxime prodrug-converting system as a novel molybdenum enzyme. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(46):34796–802. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607697200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang J, Fischer K, Zhao X, Tejero J, Kelley EE, Wang L, Shiva S, Frizzell S, Zhang Y, Basu P, Schwarz G, Gladwin MT. Novel function of sulfite oxidase as a nitrite reductase that generates nitric oxide. Free Rad Biol Med. 2010;49:S122. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang J, Krizowski S, Fischer-Schrader K, Niks D, Tejero J, Sparacino-Watkins C, et al. Sulfite Oxidase Catalyzes Single-Electron Transfer at Molybdenum Domain to Reduce Nitrite to Nitric Oxide. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014 Oct 14; doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5397. Epub: ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li H, Kundu TK, Zweier JL. Characterization of the magnitude and mechanism of aldehyde oxidase-mediated nitric oxide production from nitrite. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(49):33850–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.019125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sparacino-Watkins CE, Tejero J, Sun B, Gauthier MC, Thomas J, Ragireddy V, et al. Nitrite reductase and nitric-oxide synthase activity of the mitochondrial molybdopterin enzymes mARC1 and mARC2. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(15):10345–58. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.555177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kleinbongard P, Dejam A, Lauer T, Rassaf T, Schindler A, Picker O, et al. Plasma nitrite reflects constitutive nitric oxide synthase activity in mammals. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;35(7):790–6. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(03)00406-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Doel JJ, Godber BLJ, Eisenthal R, Harrison R. Reduction of organic nitrates catalysed by xanthine oxidoreductase under anaerobic conditions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1527(1–2):81–7. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(01)00148-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li H, Cui H, Liu X, Zweier JL. Xanthine Oxidase Catalyzes Anaerobic Transformation of Organic Nitrates to Nitric Oxide and Nitrosothiols: Characterization of the mechanism and the link between organic nitrate and guanylyl cyclase activation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(17):16594–600. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411905200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lartigue-Mattei C, Chabard JL, Bargnoux H, Petit J, Berger JA, Ristori JM, et al. Plasma and blood assay of xanthine and hypoxanthine by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry: physiological variations in humans. J Chromatogr. 1990;529(1):93–101. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(00)83810-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pesonen EJ, Linder N, Raivio KO, Sarnesto A, Lapatto R, Hockerstedt K, et al. Circulating xanthine oxidase and neutrophil activation during human liver transplantation. Gastroenterology. 1998;114(5):1009–15. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70321-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Quinlan GJ, Lamb NJ, Tilley R, Evans TW, Gutteridge JM. Plasma hypoxanthine levels in ARDS: implications for oxidative stress, morbidity, and mortality. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155(2):479–84. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.2.9032182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Himmel HM, Sadony V, Ravens U. Quantitation of hypoxanthine in plasma from patients with ischemic heart disease: adaption of a high-performance liquid chromatographic method. J Chromatogr. 1991;568(1):105–15. doi: 10.1016/0378-4347(91)80344-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li H, Samouilov A, Liu X, Zweier JL. Characterization of the effects of oxygen on xanthine oxidase-mediated nitric oxide formation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(17):16939–46. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M314336200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cantu-Medellin N, Kelley EE. Xanthine oxidoreductase-catalyzed reduction of nitrite to nitric oxide: Insights regarding where, when and how. Nitric Oxide. 2013;34:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2013.02.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Amaya Y, Yamazaki K, Sato M, Noda K, Nishino T. Proteolytic conversion of xanthine dehydrogenase from the NAD-dependent type to the O2-dependent type. Amino acid sequence of rat liver xanthine dehydrogenase and identification of the cleavage sites of the enzyme protein during irreversible conversion by trypsin. J Biol Chem. 1990;265(24):14170–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stuehr DJ, Santolini J, Wang ZQ, Wei CC, Adak S. Update on mechanism and catalytic regulation in the NO synthases. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(35):36167–70. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R400017200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]