Abstract

Several studies have reported prevalence rate of reproductive tract infections (RTIs) but very few studies have described health seeking behavior of patients. This paper critically looks at and summarizes the available evidence, systematically. A structured search strategy was used to identify relevant articles, published during years 2000–2012. Forty-one full-text papers discussing prevalence and treatment utilization pattern were included as per PRISMA guidelines. Papers examining prevalence of sexually transmitted diseases used biochemical methods and standard protocol for diagnosis while studies on RTIs used different methods for diagnosis. The prevalence of RTIs has not changed much over the years and found to vary from 11% to 72% in the community-based studies. Stigma, embarrassment, illiteracy, lack of privacy, cost of care found to limit the use of services, but discussion on pathways of nonutilization remains unclear. Lack of methodological rigor, statistical power, specificity in case definitions as well as too little discussion on the limitation of selected method of diagnosis and reliance on observational evidence hampered the quality of studies on RTIs. Raising awareness among women regarding symptoms of RTIs and sexually transmitted infections and also about appropriate treatment has remained largely a neglected area and, therefore, we observed absence of health system studies in this area.

Keywords: India, prevalence, reproductive tract infections, review, sexually transmitted infections, treatment utilization

INTRODUCTION

The International Conference on Population and Development held at Cairo in 1994 can be considered as a milestone as it attracted attention on the issue of reproductive and sexual health. Like several other countries in Asia, India launched the Reproductive and Child Health (RCH) program in 1997. The program focuses on maternal and child health services, prevention, screening and management of reproductive tract infections (RTIs), sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and many other services.[1] RTIs and STIs represent a major public health problem as the consequences are numerous. STIs/RTIs can result in pelvic inflammatory diseases, infertility, adverse pregnancy outcomes, and increased susceptibility to HIV. Due to the severe consequences and other associated morbidities, early detection and treatment of RTIs and STIs is important.[2] An estimated 340 million new cases of RTIs, including STIs, emerge every year, with 151 million of them occurring in Asia.[3] District Level Household Survey-3 survey reports 18.3% prevalence of symptoms of RTI/STI in India and only around 40% took treatment.[4] Studies on RTIs suggest that about half the women with RTI do not present symptoms and that RTIs are not limited to high-risk population any more.[5] There is also a need to conduct studies to assess various behavioral and sociodemographic factors, predisposing women to the risk of RTIs/STIs.[6] Increased prevalence of RTIs/STIs constitutes a huge health and economic burden for developing countries and account for economic losses because of ill health.[7] Therefore, some of the studies have demanded a comprehensive culture-sensitive approach for all RTIs/STIs, and their integration and implementation into basic reproductive health services.[8] Although programmatic initiatives in the field of adolescent and youth sexual and reproductive health have begun; findings suggested that married men and women are at risk of adverse sexual and reproductive health outcomes and efforts to reach them are inadequate.[9]

Therefore, a systematic review was undertaken to throw light on the prevalence of and treatment utilization for RTIs/STIs in India. This review paper is based on the following objectives: (a) To study prevalence of RTIs/STIs among Indian women reported in the published studies (year 2000–2012) (b) to study treatment utilization by women for RTIs/STIs as reported in the published studies (year 2000–2012) (c) to understand the factors that influence their utilization as reported in published studies (year 2000–2012). It is hoped that this review would be useful for policy makers especially for designing interventions to remove barriers for treatment utilization.

METHODOLOGY

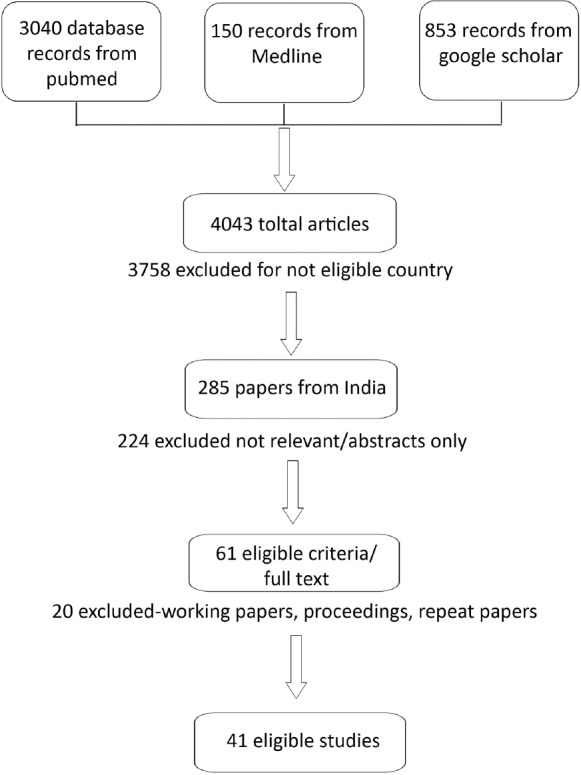

Studies reporting prevalence of RTIs and STIs and utilization of healthcare services for treating these conditions were included in this literature-based analysis. Search for the articles published from 2000 up-to-the mid of 2012 was conducted using PubMed, Medline, and Google scholar. Following keywords were used; prevalence of RTIs/STIs, health service utilization and RTIs/STIs, treatment and RTIs/STIs, health seeking behavior and RTIs/STIs. An additional step was taken to visit websites of selected journals (only those journals which are indexed in the selected repositories) and search relevant articles for making review more exhaustive. Figure 1 describes the process of selection of papers. Forty-one eligible papers were analyzed after obtaining their full text, carefully. Results were categorized based on the objectives of the review and presented in a tabular format.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the studies included in the systematic review

RESULTS

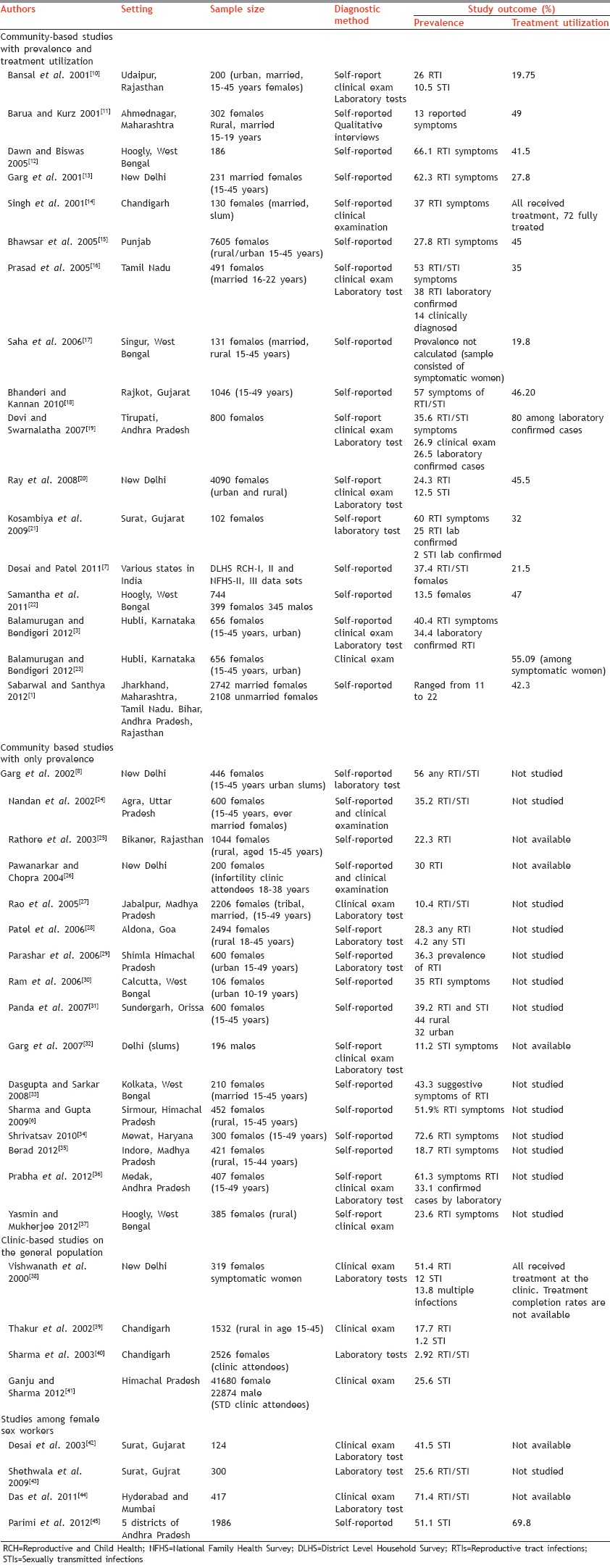

The results of the systematic review are presented in Table 1 under subheadings: (a) Community-based studies with prevalence and treatment utilization (17 studies), (b) community-based only prevalence studies (16 studies), (c) clinic-based studies on population (four studies), and (d) studies among female sex workers (four studies). Almost all studies have included ever-married females in reproductive age group (aged 15–45/49 years). There are 15 studies on rural sample, 19 studies on urban (slum and nonslum) population remaining studies include both. Three studies were multistate studies. Delhi, West Bengal reported six studies each and other northern states (Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Punjab, Chandigarh) reported nine studies. The Southern states (Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu) reported six while eight studies were from the western states (Gujarat, Rajasthan, Goa and Maharashtra). Two studies from Madhya Pradesh and one from Odisha was also noted. We did not come across papers on Kerala, Bihar, and the northeastern population.

Table 1.

Summary of studies included in the review depicting prevalence and treatment use

Prevalence studies: Study design, sample size, and the method of diagnosis

Present review has included 41 papers which reported prevalence of either RTIs or STIs or both. Table 1 provides details of all studies on estimating the prevalence of RTIs/STIs as well that reporting treatment utilization rate. These studies are organized in chronological order. In the case of community-based prevalence studies, self-report was the chief method of diagnosis (12 studies). Studies using self-report have used syndromic diagnosis. Abnormal vaginal discharge, changed color and texture of vaginal discharge, lower abdominal pain, painful micturition, genital ulceration, genital itching, swelling, pain during intercourse, and such symptoms were considered for diagnosis. These studies reported recall period of one to 12 months, and they interviewed respondents in a private setting to obtain information on reproductive history, current symptoms, past sexual behavior, etc. Community-based studies have used cross-sectional study design with a sample size of minimum 130 to more than 7000 females. Two studies[1,7] reporting very large sample size have used secondary data generated from national or sub-national level surveys. Majority of the prevalence studies have used appropriate technique of sample size calculation with exception of a few studies in rural settings where all eligible women were included. Clinic-based studies followed time-space sampling method and their recruitment period ranged from 3 months to a maximum of 3 years. All clinic-based studies have used clinical examination (using speculum), along with self-reporting of symptoms (five studies), and laboratory tests (four studies) while two studies used only laboratory test for diagnosis. Majority of the studies claimed to have followed WHO syndromic approach for diagnosis and management. Cervical and vaginal swabs and blood samples were collected from the clinically diagnosed cases. These studies reported to have followed standard laboratory techniques for detection of classical and other agents of STIs/RTIs.

Prevalence of all RTIs ranged from 11% to 72% in the self-reported community-based studies, whereas 17–40% in studies which have used clinical examination among self-reported symptomatic women. Prevalence changed (7–34%) in the studies where laboratory methods were used to confirm clinical diagnosis and self-reports. Commonly found STIs (gonorrhea, chlamydia, or trichomoniasis) were detected using laboratory methods (total nine studies) and it ranged from approximately one to 15% with the exception of one study.[8] Prevalence of Syphilis ranged from <1% to 4%, Trichomoniasis prevalence from <1% to 10%, and reporting of gonorrhea was negligible. A wide variation in prevalence was noted perhaps due to the use of different methods (clinical, laboratory or self-report) either alone or in combination for the diagnosis of RTIs/STIs. We came across four studies on female sex workers with a sample size ranging from 124 to 1986 female sex workers.[42,43,44,45] These studies reported very high rate of STIs prevalence (around 40%) as compared to the other community-based studies. Three of these studies have used clinical and laboratory methods for confirmation of the diagnosis.

Utilization of health services and factors affecting treatment utilization

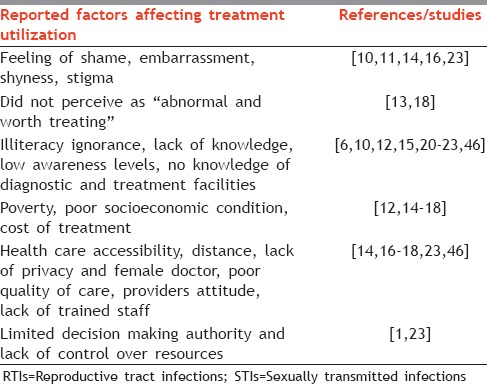

Totally, 18 studies have reported health seeking behavior or use of health care services for RTIs/STIs. Treatment utilization ranged from 16% to 55% in the community-based studies. Some studies[14,19] provided treatment as a part of their research, hence service utilization rates were very high (>70%) in those studies. These factors can be broadly categorized as: (a) Social and cultural factors (feeling of shame, embarrassment, shyness, stigmatizing attitude, limited decision making by women, lack of control over resources, did not perceive as abnormal and worth treating), (b) environmental factors (lack of accessibility, illiteracy, ignorance, lack of knowledge), (c) economic factors (poor socioeconomic conditions and treatment cost), and (d) health care facility factors (lack of privacy, absence of female doctor, perceived poor quality of care). Table 2 describes the factors which are identified in various studies as barriers for treatment utilization. It was observed that the treatment options in RTIs/STIs ranged from self-treatment, home remedies to visiting traditional healers, visiting unqualified practitioners to contacting qualified allopathic providers and many times patients display poor health seeking behavior in terms of delay in seeking help, partial treatment, use of ineffective means, or nontreatment.[47] The determinants for accessing reproductive health care were found to be many; resources available at the household level, social factors, availability of services, health care quality, distance, providers attitude.[18] Studies discussing reasons for nonutilization mentioned that the problem of RTIs/STIs morbidity in women was largely due to ignorance, illiteracy, lack of awareness and outside exposure, low female literacy.[13,14,15,19] Lack of female doctors at health facilities, afraid of the results of the laboratory tests and perception that the physicians had judgmental procedures prevented them from using services.[10,11,23,38] Stigma, embarrassment, and low status of females,[16] as well as shyness of genital examination, affect their treatment utilization negatively.[1,15,16] Cost of care,[14,17] preference for a traditional healer, faith in home remedies[23] deterred them from seeking appropriate treatment. Prevalence of these factors and practices led to the preference for quacks, spiritual, and traditional healers over the modern medicine practitioners.[17,47]

Table 2.

Factors affecting treatment utilization for RTIs/STIs

DISCUSSION

This review identified literature which investigated the prevalence of RTI and STIs and factors affecting utilization of services. The search was done using broad terms and including three major on-line repositories to minimize the potential for any selection bias. The search was spread as wide as feasible given time and resource constraints. A major challenge was not to include unpublished research and those published in journals which are not indexed in the selected repositories. In a relatively poorly researched field, we came across many working papers, booklets, technical reports, unpublished dissertations. However, we decided not to include them in the present review. Future reviewers may endeavor to widen the search to include these forms of literature. In order to minimize reviewer's bias, relevance, findings, and quality of each paper was assessed by the two researchers. Studies not included in the final paper were also scrutinized by the researchers. We did not come across any review paper on this subject matter. In addition, we did not include papers for which we were not able to obtain full papers due to resource constraints, although University has subscriptions to most of the prominent journals in this subject.

With these limitations in mind, it can be concluded that the prevalence of RTIs ranged from nearly 11% to 72% and nearly half of the syndromically diagnosed cases were confirmed by laboratory tests. The prevalence of RTI has not changed much over the years. Substantial number of studies has used clinical approach for diagnosis though self-report was a common method for reporting prevalence. Wherever possible, clinical and laboratory findings should support self-reported morbidity to know the exact prevalence of these diseases in the community.[3,20] The high heterogeneity in the results of these studies was most probably result of the wide variation in approaches used by researchers even when investigating the same research question and most probably using same case definition.

Treatment utilization ranged from 16% to 55% in the community-based studies where treatment was not provided as a part of the study. As each study, in this review, deals with a specific setting, factors affecting utilization and service choice vary from one study to another. Several sociocultural, economic, environmental factors affected health care utilization. Nonetheless, seeking treatment from appropriate care provider is very important as early health seeking from qualified, competent practitioner will reduce the progress of the disease or infection and further reduce the complications.[23]

Treatment utilization studies were heavily depended on reporting of treatment use and lack evidence on treatment completion rate, cure rates, quality of care, and more importantly qualitative data on how barriers influence behavior. The papers identified and reviewed here did not allow us to understand the ways in which these factors work to prevent utilization of services. The methodological shortcomings were many including lack of statistical rigor, limited discussion of the problem of infection; lack of specificity in case definitions; reliance on observational evidence than biochemical tests for calculating prevalence. These and such methodological limitations prevented us from drawing strong conclusions. We are aware about the study limitations and believe that there is much scope for dedicated epidemiological research pertaining to RTIs and STIs, which is of relevance to millions of women and girls across the world.

CONCLUSION

With this review, we hope to have provided the basis for future research in the area of health care utilization for RTIs/STIs. The purpose of this paper was to collate the available evidence from India and to critically appraise it for academic interest as well as to develop leads for policy. It can be concluded from the review that RTIs/STIs remain neglected area which results in poor utilization of services irrespective of its high prevalence. More methodologically consistent research is required in the area of RTIs/STIs. Raising awareness and access to appropriate services for treating RTIs/STIs appear to be eluding despite implementation of RCH policy over two decades.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding for this research is provided by the University of Pune under the scheme of University with Potential of Excellence granted by the University Grants Commission, New Delhi. The authors would like to thank all those who have conducted research in this area through the years and made this review possible.

Footnotes

Source of Support: University of Pune through UGC-UPE II project.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sabarwal S, Santhya KG. Treatment-seeking for symptoms of reproductive tract infections among young women in India. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2012;38:90–8. doi: 10.1363/3809012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geneva: World Health organization; 2005. World Health Organization. Sexually Transmitted and Other Reproductive Tract Infections. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balamurugan SS, Bendigeri N. Community-based study of reproductive tract infections among women of the reproductive age group in the Urban health training centre area in Hubli, Karnataka. Indian J Community Med. 2012;37:34–8. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.94020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mumbai, India: International Institute for Population Sciences; 2010. District Level Household Survey-3, 2007-2008; Ministry of health and family welfare. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramarao S, Townsend JW, Khan ME. A model of costs of RTI case management services in Uttar Pradesh. Soc Change. 1996:1–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharma S, Gupta B. The prevalence of reproductive tract infections and sexually transmitted diseases among married women in the reproductive age group in a rural area. Indian J Community Med. 2009;34:62–4. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.45376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Desai G, Patel R. Incidence of reproductive tract infections and sexually transmitted diseases in Indial: Levels and differentials. J Fam Welf. 2011;57:48–60. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garg S, Sharma N, Bhalla P, Sahay R, Saha R, Raina U, et al. Reproductive morbidity in an Indian urban slum: Need for health action. Sex Transm Infect. 2002;78:68–9. doi: 10.1136/sti.78.1.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Santhya K, Jeejebhoy S. New Delhi: Population Council; 2012. The Sexual and Reproductive Health Rights of Young People in India: A Review of Situation; pp. 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bansal K, Singh K, Bhatnagar S. Prevalence of lower RTI among married females in the reproductive age group (15-45) Health Popul Perspect Issues. 2001;24:157–63. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barua A, Kurz K. Reproductive health-seeking by married adolescent girls in Maharashtra, India. Reprod Health Matters. 2001;9:53–62. doi: 10.1016/s0968-8080(01)90008-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dawn A, Biswas R. Reproductive tract infection: An experience in rural West Bengal. Indian J Public Health. 2005;49:102–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garg S, Meenakshi M, Singh M, Mehra M. Perceived reproductive morbidity and health care seeking behavior among women in an urban slum. Health Popul Perspect Issues. 2001;24:178–88. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh MM, Devi R, Garg S, Mehra M. Effectiveness of syndromic approach in management of reproductive tract infections in women. Indian J Med Sci. 2001;55:209–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhawsar R, Singh J, Khanna A. Determinants of RTI/STI's among women in Punjab and their health seeking behavior. J Fam Welf. 2005;51:24–35. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prasad JH, Abraham S, Kurz KM, George V, Lalitha MK, John R, et al. Reproductive tract infections among young married women in Tamil Nadu, India. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2005;31:73–82. doi: 10.1363/3107305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saha A, Sarkar S, Mandal N, Sardar J. Health care seeking behaviour with special reference to reproductive tract infections and sexually transmitted Diseases in rural women of West Bengal. Indian J Community Med. 2006;31:284–5. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhanderi MN, Kannan S. Untreated reproductive morbidities among ever married women of slums of Rajkot City, Gujarat: The role of class, distance, provider attitudes, and perceived quality of care. J Urban Health. 2010;87:254–63. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9423-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Devi S, Swarnalatha N. Prevalence of RTI/STI among reproductive age women (15-49 Years) in urban slums of Tirupati town, Andhra Pradesh. Health Popul Perspect Issues. 2007;30:56–70. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ray K, Bala M, Bhattacharya M, Muralidhar S, Kumari M, Salhan S. Prevalence of RTI/STI agents and HIV infection in symptomatic and asymptomatic women attending peripheral health set-ups in Delhi, India. Epidemiol Infect. 2008;136:1432–40. doi: 10.1017/S0950268807000088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kosambiya JK, Desai VK, Bhardwaj P, Chakraborty T. RTI/STI prevalence among urban and rural women of Surat: A community-based study. Indian J Sex Transm Dis. 2009;30:89–93. doi: 10.4103/2589-0557.62764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Samantha A, Ghosh S, Mukherjee S. Prevalence and health seeking behavior of reproductive tract infections/sexually transmitted infections symptomatic: A cross sectional study of a rural community in the Hooghly District, West Bengal, India. Indian J Public Health. 2011;55:38–41. doi: 10.4103/0019-557X.82547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Balamurugan S, Bendigeri N. Health care-seeking behavior of women with symptoms of reproductive tract infections in urban field practice area, Hubli, Karnataka. National Journal of Research in Community Medicine. 2012;1:123–77. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.94020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nandan D, Misra S, Sharma A, Jain M. Estimation of prevalence of RTI's/STD's among women of reproductive age group in district Agra. Indian J Community Med. 2002;XXVII:110–3. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rathore M, Swami S, Gupta B, Sen V, Vyas B, Bhargav A, et al. Community based study of self-reported morbidity of reproductive tract among women of reproductive age in rural area of Rajasthan. Indian J Community Med. 2003;XXVIII:117–21. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pawanarkar J, Chopra K. Prevalence of lower reproductive tract infections in infertile women. Health Popul Perspect Issues. 2004;27:67–75. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rao V, Savargaonkar D, Anvikar A, Bhondeley M, Tiwary B, Ukey M, et al. Reproductive tract infections in tribal women of central India. (last updated in 2006) [Last accessed on 2014 October 10 th]. Available from: www.rmrct.org/files_rmrc_web/centre's_publication/NSTH_06/NSTH06_33.V.G.Rao.pdf .

- 28.Patel V, Weiss HA, Mabey D, West B, D'souza S, Patil V, et al. The burden and determinants of reproductive tract infections in India: A population based study of women in Goa, India. Sex Transm Infect. 2006;82:243–9. doi: 10.1136/sti.2005.016451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parashar A, Gupta B, Bhardwaj R. Prevalence of RTI among women of reproductive age group in Shimla city. Indian J Community Med. 2006;31:15–7. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ram R, Bhattacharya S, Bhattacharya K, Baur B, Sarkar T, Bhattacharya A, et al. Reproductive tract infection among female adolescents. Indian J Community Med. 2006;31:32–3. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Panda S, Bebarrta S, Parida S, Panigrahi O. Prevalence of RTI/STI among women of reproductive age group in district Sundergarh, Orissa. Indian J Practicing Doct. 2007;4.1:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garg S, Singh MM, Nath A, Bhalla P, Garg V, Gupta VK, et al. Prevalence and awareness about sexually transmitted infections among males in urban slums of Delhi. Indian J Med Sci. 2007;61:269–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dasgupta A, Sarkar M. A study on reproductive tract infections among married women in the reproductive age group (15-45 years) in a slum of Kolkata. J Obstet Gynecol India. 2008;58:518–22. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shrivatsav L. Reproductive tract infections among women of rural community in Mewat, India. J Health Manage. 2010;12:519–38. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berad A. Epidemiological study of Reproductive tract infections in rural area of Indore district. Webmedcentral Infect Dis. 2012;3:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prabha ML, Sasikala G, Bala S. Comparison of syndromic diagnosis of reproductive tract infections with laboratory diagnosis among rural married women in Medak district, Andhra Pradesh. Indian J Sex Transm Dis. 2012;33:112–5. doi: 10.4103/2589-0557.102121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yasmin S, Mukherjee A. A cyto-epidemiological study on married women in reproductive age group (15-49 years) regarding reproductive tract infection in a rural community of West Bengal. Indian J Public Health. 2012;56:204–9. doi: 10.4103/0019-557X.104233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vishwanath S, Talwar V, Prasad R, Coyaji K, Elias CJ, de Zoysa I. Syndromic management of vaginal discharge among women in a reproductive health clinic in India. Sex Transm Infect. 2000;76:303–6. doi: 10.1136/sti.76.4.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thakur J, Swami H, Bhatia, S Efficacy of Syndromic management of reproductive tract. Indian J Community Med. 2002;27:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sharma M, Sethi S. Seroprevalence of reproductive tract infections in women in Northen India - A relatively low prevalence area. Sex Transm Infect. 2003;79:495–500. doi: 10.1136/sti.79.6.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ganju SA, Sharma NL. Initial assessment of scaled-up sexually transmitted infection intervention in Himachal Pradesh under National AIDS Control Program - III. Indian J Sex Transm Dis. 2012;33:20–4. doi: 10.4103/2589-0557.93809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Desai VK, Kosambiya JK, Thakor HG, Umrigar DD, Khandwala BR, Bhuyan KK. Prevalence of sexually transmitted infections and performance of STI syndromes against aetiological diagnosis, in female sex workers of red light area in Surat, India. Sex Transm Infect. 2003;79:111–5. doi: 10.1136/sti.79.2.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shethwala ND, Mulla SA, Kosambiya JK, Desai VK. Sexually transmitted infections and reproductive tract infections in female sex workers. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2009;52:198–9. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.48916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Das A, Prabhakar P, Narayanan P, Neilsen G, Wi T, Kumta S, et al. Prevalence and assessment of clinical management of sexually transmitted infections among female sex workers in two cities of India. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2011;2011:494769. doi: 10.1155/2011/494769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Parimi P, Mishra R, Tucker S, Sagrutti N. Mobilizing community collectivization among female sex workers to promote STI service utilization from the government healthcare system in Andhra Pradesh. India J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012;66:I62–8. doi: 10.1136/jech-2011-200832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rode S. Determinants of RTI/STI's Prevalence Among Women in Haryana. Working Papers/Health Studies. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Agarwal P, Kandpal S, Negi K, Gupta P. Health seeking behaviour for RTI's/STI's: Study of a rural community in Dehradun. Health Popul Perspect Issues. 2009;32:66–72. [Google Scholar]