Abstract

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are a public health problem, and their prevalence is rising even in developed nations, in the era of HIV/AIDS. While the consequences of STIs can be serious, the good news is that many of these complications are preventable if appropriate screening is done in high-risk individuals, when infection is strongly suspected. The diagnostic tests for STIs serve many purposes. Apart from aiding in the diagnosis of typical cases, they help diagnose atypical cases, asymptomatic infections and also multiple infections. But, the test methods used must fulfill the criteria of accuracy, affordability, accessibility, efficiency, sensitivity, specificity and ease of handling. The results must be rapid, cost-effective and reliable. Most importantly, they have to be less dependent on collection techniques. The existing diagnostic methods for STIs are fraught with several challenges, including delay in results, lack of sensitivity and specificity. With the rise of the machines in diagnostic microbiology, molecular methods offer increased sensitivity, specificity and speed. They are especially useful for microorganisms that cannot be, or are difficult to cultivate. With the newer diagnostic technologies, we are on the verge of a major change in the approach to STI control. When diagnostic methods are faster and results more accurate, they are bound to improve patient care. As automation and standardization increase and human error decreases, more laboratories will adopt molecular testing methods. An overview of these methods is given here, including a note on the point-of-care tests and their usefulness in the era of rapid diagnostic tests.

Keywords: Molecular diagnosis, nucleic acid tests, point-of-care tests, sexually transmitted diseases, sexually transmitted infections

INTRODUCTION

Sexually transmitted infections (STI) are a group of infectious diseases where the epidemiologically important mode of transmission occurs during sexual intercourse or intimate genital contact.[1] There are severe complications implicated with untreated STIs, and they are also known to amplify the risk of HIV transmission.[2] Also, human papillomavirus (HPV) which causes genital warts, is implicated in cancer of the cervix in women.[3]

According to the WHO global summit (2012),[4] there are 340 million new cases of syphilis, gonorrhea, chlamydiasis and trichomoniasis in the 15–49 age group. HPV infections constitute 5,00,000 cases/year of which 80% are reportedly from developing countries.[4,5] A large proportion of STIs are asymptomatic or sub-clinical and hence go undiagnosed. But, the good news is that many STIs are preventable with appropriate screening, especially in high-risk individuals.

The diagnostic tests for STIs help diagnose typical cases, and also atypical, asymptomatic and multiple infections. Their nondiagnostic uses include-screening high-risk groups, monitoring treatment, surveillance, outbreak investigations, validation of syndromic management, detection of antimicrobial resistance patterns (e.g., in Neisseria gonorrhea), ensuring quality assurance in laboratory tests and research purposes.[6]

The laboratory diagnosis of STIs include:

Direct microscopy to demonstrate the organism

Culture/isolation of organisms

Antigen detection

Serology for detection of antibodies

Tests that detect microbial metabolites (e.g., Whiff test)

Molecular methods of diagnosis.

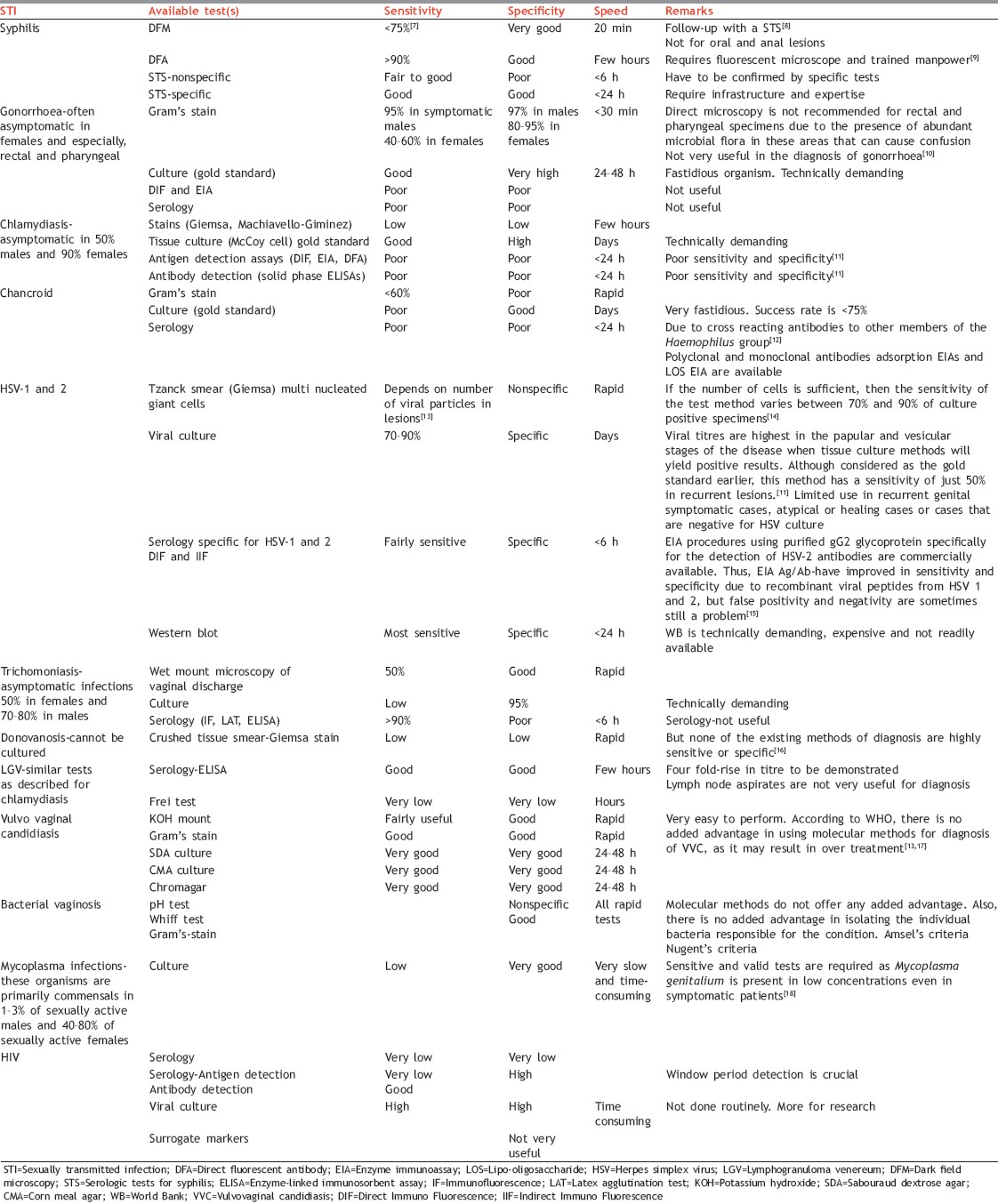

The merits and demerits of existing diagnostic tests for various STIs have been highlighted in Table 1.[7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18] From the table, it is evident that many of the routinely performed tests lack sensitivity, specificity and speed. The molecular diagnostic methods promise to deliver on all these counts.

Table 1.

Challenges in routine diagnostic tests for STIs

OVERVIEW OF MOLECULAR METHODS FOR DIAGNOSIS OF SEXUALLY TRANSMITTED INFECTIONS

The molecular methods are useful for microorganisms that are difficult to culture. They have a fairly recent history of just over 40 years. They are increasingly being accepted by clinicians as viable options in their practice. In 1961 Marmur and Doty described the nucleic acid hybridization (NAH) technique. It gained immense popularity, especially DNA probes, although limited by its sensitivity. All this changed in 1983, when Kary Mullis conceived and developed the polymerase chain reaction (PCR).[19]

What are NATs? Nucleic acid tests are techniques that detect specific sequences in DNA or RNA of a microorganism that may be associated with disease. There are 3 broad types of assays used in molecular diagnostics:[20]

Hybridization techniques – e.g., NAH

Amplification techniques – e.g., PCR

Assays used in Epidemiological investigations – e.g., strain typing and identification.

Uses of molecular techniques in management of sexually transmitted infections

Detection of microorganisms that are difficult/impossible to culture.[19,21] E.g., HPV, Treponema pallidum

Identification of organisms isolated in pure culture

Rapid identification of organisms, from clinical specimens

Differentiation between closely related organisms (e.g., herpes simplex virus [HSV]-1 and 2)

Understanding the epidemiology and pathophysiology of STIs (e.g., DNA fingerprint analysis)

Improving sensitivity and specificity of serological assays by using cloned proteins and recombinant antigens.

TYPES OF MOLECULAR METHODS

Nucleic acid hybridization techniques

These assays rely on sensitivity and specificity of hybridization reactions (binding) between probe and target nucleic acid (NA). The DNA/RNA of the microorganism in the clinical specimen is called the target NA, while the complementary, single stranded DNA/RNA oligonucleotide NA attached to a reporter chemical/radionucleotide/fluorescent dye, is called the probe NA.

Amplification techniques

There is an exponential increase in target NA copies, such that their numbers are high enough to be identified by various detection methods. The amplification may be of Target, Probe or Signal.

Strain typing and identification

These assays determine strain relatedness between NAs from various sources for epidemiological investigations.

Basic steps in molecular diagnosis involve

Specimen collection

Specimen processing-extraction and purification of NA from clinical samples

Amplification or hybridization - depending on the test method used

Detection of end products of amplification or hybridization, by appropriate methods.

Nucleic acid hybridization

Two single NA strands with complementary base sequences specifically bond with each other forming a double-stranded molecule (duplex or hybrid). The single stranded molecules may be DNA or RNA. Thus, hybrids may be DNA-DNA, DNA-RNA or RNA-RNA. The target (template) may be in situ, free in solution or immobilized on a solid support.

Hybrid capture technology

This is an example of in vitro NAH assay using a microtitre plate and chemiluminiscence for the qualitative detection of NA targets in specimens (sensitivity - 85% and specificity-nearly 100%).

Applications of nucleic acid hybridization technology

Direct detection of microorganisms from specimens, using chemiluminiscence labeled probes.[21,22] E.g., HBV, HSV, PACE-2 (GenProbe). Also used for confirmation of microorganisms isolated in pure cultures.

Amplification techniques

There are three types of amplification methods:

Target amplification

Here the target NA in the sample is amplified and then detected by various methods. It is very popular and includes PCR, real-time PCR and reverse transcription-PCR.

Signal amplification

Here the signal is amplified after hybridizing a probe to an organism's NA (target). Cross-contamination is less common in this. E.g., branched chain DNA detection. These assays are available for quantification of RNA from HCV and HIV, and DNA from HBV.

Probe amplification

An example of this technique is ligase chain reaction in which DNA ligase enzyme is used to seal the gap between two probes annealed to the target DNA. The sealed probe is then used as a target for amplification in subsequent steps. Once used to identify Chlamydia trachomatis (CT) and N. gonorrhea(NG) from clinical specimens, the test has now lost its popularity.

The following section will describe the most popular amplification method used in molecular diagnosis of STIs:

Polymerase chain reaction

This technique is akin to a “Xerox machine” in which millions of identical copies of the target NA are generated.

Steps in polymerase chain reaction

NA (DNA) extraction from specimen

Denaturation of DNA strands

Annealing (attachment) of oligonucleotide primers to single stranded DNA strands

Primer extension to form complementary strands (amplification)

Detection of products of amplification (amplicons).

Advantages of polymerase chain reaction

Rapid detection time

Increased sensitivity and specificity

Some provide quantitative data (e.g., viral load in real-time PCR)

Automated NA isolation systems possible.

Disadvantages of polymerase chain reaction

Cost, instrumentation, requirement of trained manpower and space, false positive (contamination), nonspecific amplification or no amplification.

Types of polymerase chain reaction

Conventional polymerase chain reaction

As described above.

Real-time polymerase chain reaction

This is an innovative breakthrough for the detection of PCR products. Here the target amplicons are detected in real-time (30-40 min) as they accumulate after each cycle once a threshold is reached. Thus, the detection is exponential, rather than an end-point analysis, and uses the fluorescence-based technology. Also, it is a closed system with no accumulation of hazardous waste, no contamination, no postamplification processing and the imaging system is a part of the real-time instrumentation. It is cost-effective, with a high throughput and sensitivity and specificity. Quantitation is also possible, such as viral load estimation in HIV infection.

Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

This is a very sensitive technique for detecting and quantifying mRNA, especially useful to detect RNA viruses from clinical specimens. This method uses the enzyme Reverse Transcriptase to synthesize a complementary strand of DNA (cDNA) from an RNA template. The resulting cDNA serves as a target and is amplified just as described in conventional PCR.

Multiplex polymerase chain reaction

Here, it is possible to simultaneously detect two or more different targets in one PCR tube. Inclusion of internal controls is important to make the assay results dependable. E.g., both CT and NG in a single PCR tube. There is also a multiplex PCR available for the detection of organisms causing genital ulcer disease (T. pallidum, Haemophilus ducreyi and HSV 1 and 2).

Nested polymerase chain reaction

A very sensitive and specific PCR technique involving two different, consecutive PCRs. The amplicons derived from the first PCR reaction, serve as the targets for the second PCR. The second primer pair is complementary to an internal region of amplicons derived from first PCR. This increases its specificity.

Broad-range

Polymerase chain reaction-used to identify broad taxonomic groups of organisms.

Transcription mediated amplification

This is an isothermic amplification procedure at 41°C, that does not require a thermal cycler. Transcription mediated amplification (TMA) targets rRNA sequences of microorganisms, producing 100–1000 transcripts in each cycle, using two enzymes. The RNA transcripts are detected by hybridization probe assay. The commercial APTIMA system automates the TMA method for laboratories with high volume.[23]

Nucleic acid sequence based amplification

Another isothermic technique very similar to TMA, used mostly for RNA viruses. It is a self-sustained sequence replication, where three enzymes are used, and the amplification process results in formation of RNA amplicons. NA sequence based amplification (NASBA) is useful in detecting many RNA viruses such as HIV-1.

Strain typing and identification (DNA/genetic fingerprinting)[19]

These typing methods determine the genetic relatedness in microorganisms. They are based on the mutations that accumulate over time in many organisms. These methods are broadly divided into nonamplified and amplified methods. For a detailed description of these methods, the reader is advised to refer to appropriate literature.

DNA microarray (gene chip/DNA chip)

This is a novel and exciting method of evaluating the gene expression from an entire organism, or even from several organisms, as per requirement. It consists of a microscopic grouping of DNA molecules attached to a solid support mechanism, in the form of spots, called reporters. Fluorescently labeled DNA/RNA strands from specimens are incubated with these chips and a scanner reads the fluorescence of hybrids only. A DNA microarray has the potential to detect nearly all pathogens simultaneously.[24]

Proteomics

This is also a molecular level diagnostic technology, but here, unlike NAs like DNA or RNA, proteins at the cellular level are studied. The proteome of an organism is the sum of proteins found during all changing conditions of the cell. Proteomics is used to determine protein expression in disease conditions, including infectious diseases.

Common fallacies in molecular assays

False positive reactions may occur due to carry-over contamination (amplicons) from previously amplified products.[21,25] There may be exogenous target DNA in reagents, water, kits, sterile blood culture material etc., Poor primer design may also lead to nonspecific reactions.

False negative reactions-may occur due to inadvertent loss of template NA target due to poor extraction, handling and storage protocols, poor primer design (nonconserved regions at primer sites).

APPLICATIONS OF MOLECULAR DIAGNOSTIC METHODS FOR SEXUALLY TRANSMITTED INFECTIONS

Gonorrhea

Usually tested along with CT.[26] Available tests include - NAH, nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) and multiplex PCR. Results are available in <24 h. Specimens include endocervical or even vaginal swabs in females. Urethral, rectal and oropharyngeal swabs can also be used. In heterosexual males urethral swab or urine specimens can be used for NAAT. In men having sex with men MSM, in addition to the above, rectal and oropharyngeal swabs may be used.

The sensitivity of NAAT (95%), is superior to culture, especially for rectal and pharyngeal swabs, but specificity is less. Only NAAT for urethral swab is presently Food and Drug Administration (FDA), USA approved. And culture is the only method for antimicrobial susceptibility.

HIV

Qualitative testing for proviral DNA or RNA can be done by PCR for diagnosis. Detection of HIV RNA, DNA or p24 is important for early infant diagnosis and also for detection of HIV infection during the “window period.”

For management and monitoring of treatment, quantitative testing is desirable, such as viral load estimation, which can be accomplished by real-time PCR, TMA, NASBA or signal amplification methods. And for drug resistance testing, genotyping is the method of choice.

Chlamydiasis

Nucleic acid hybridization is useful and sensitive for CT, with results in <24 h. E.g., GenProbe PACE-2 and PACE2C (Probe assay chemiluminiscence enahanced). But these are less sensitive than NAAT methods. NAAT is highly successful for Chlamydia because it reduces the need for strict transport and storage of specimens. Also, it can be combined with N. gonorrhea, and is highly sensitive and specific, with freedom to use a wide variety of specimen types. It also removes the bias of subjective analysis.[27]

Herpes simplex virus 1 and 2

Nucleic acid amplification tests are now the gold standard for HSV 1 and 2. Real-time PCR is ideal for skin lesions and allows detection of asymptomatic HSV shedding. The primers may be common to HSV-1 and 2 or only one, and results are available in 24–48 h. Sensitivity and specificity touch 98% and 100%, respectively.[28] The method is good for cerebrospinal fluid samples too, although not validated for all types of samples. However, it is important to remember that a negative PCR result does not mean absence of infection.

Mycoplasma genitalium infection

Nucleic acid amplification test for Mycoplasma can be performed on first void urine samples in males and vaginal swab in females. TMA can be used with 16s rRNA as the targets. Presently this is only used for research purposes.

Human papillomavirus

Earlier, the Pap test was the gold standard to diagnose these infections, but now, PCR is recommended by FDA, USA, as first line test.

Chancroid

DNA probes and PCR are useful options for H. ducreyi, since diagnosis by culture and smear have very poor sensitivity.

Lympho granuloma venereum

Polymerase chain reaction is available. The pmpH gene deletion is seen only in lympho granuloma venereum isolates, which may prove useful in its diagnosis.

Trichomoniasis

Several molecular methods are available for its diagnosis. These can be useful if properly standardized.[29]

Bacterial vaginosis

Although NAAT methods are available, the diagnosis of BV by molecular methods is not really indicated. Affirm VP-III – uses DNA hybridization to detect Gardnerella vaginalis.[30]

Other sexually transmitted infections

The genital ulcer multiplex PCR (test), uses primers for Syphilis, HSV, Chancroid and Donovanosis, in a single test procedure. Currently, this is not available in most countries.

Point-of-care tests

After a description of molecular methods of diagnosing STIs, some notes on point-of-care test (POCT) will be useful, as some of these are based on principles of molecular methods.

What are point-of-care tests?

Tests that offer immediate results, wherein patients can receive diagnosis and treatment in a single visit. These tests can be used at home or the site of service delivery, by trained or untrained users. They are easy to use, compact, durable and noninvasive with no stringent storage requirements. The turn-around-time to results is <20 min, and both sensitivity and specificity are >95%.

Need for point-of-care tests

World over, it is now being increasingly recognized that failure of health services is often due to unaffordability and inaccessibility of facilities (WHO-2004). Also, syndromic case management is not always a reliable method, especially for vaginal discharges.[31]

The use of simple POCTs increases specificity of syndromic management reduces over-treatment and screens for asymptomatic STIs.

Characteristics of point-of-care tests

Any POCT, to be useful, should fulfill the A-S-S-U-R-E-D characteristics[32]

A = Affordable

S = Sensitive

S = Specific

U = User friendly (easy-to-use, minimal training)

R = Robust (store at room temp.) and Rapid (result in <20 min)

E = Equipment-free

D = Deliverable to end-users.

In addition, the test kit should have self-contained quality controls, and be amenable to safe waste disposal methods, at minimal cost. Thus, the treatment, counseling and partner notification of clients can be accomplished in the same visit.

Principles and types of point-of-care tests[33]

The POCTs currently available may be based on any of the following principles:

Agglutination/Precipitation Reactions, E.g., Rapid plasma regain.

Immuno chromatography (ICT): (a) Lateral flow format. (b) Multiplex ICT. E.g., (HIV + Syphilis), (HIV + Syphilis + HBV/HCV), (Non treponemal + Treponemal tests). (c) Flow through format. E.g., Dot-blot tests. (d) Rapid test readers/scanners to remove observer bias, increase sensitivity and for quantitation.

Emerging technologies: E.g., (a) Microfluidic assays - detect multiple analytes from single specimen (E.g., HIV and T. pallidum). (b) Rapid Molecular assays.

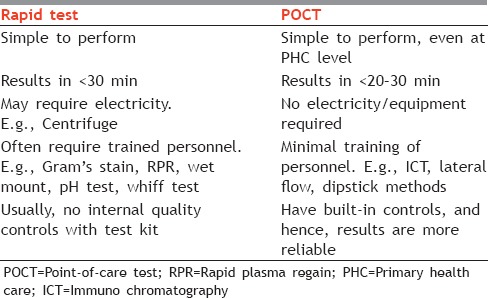

It is important to differentiate between Rapid tests and POCTs [Table 2] because the two are often used and understood to be synonymous.

Table 2.

Differences between Rapid test and POCT

Syphilis

The use of POCT in pregnant women and at-risk populations helps in reducing the disease burden in sexually active adults, very useful, especially in rural antenatal clinics.[34] POCT for multiple STIs (E.g., HIV + Syphilis) and also for simultaneous detection of nontreponemal and treponemal antibodies for syphilis hold the promise of eliminating mother-to-child transmission of HIV and congenital syphilis.[35]

Gonorrhea

Many POCTs designed for gonorrhea have low sensitivity and specificity compared to NAAT. There is a growing need for POCT to test for resistance in gonococci. POCT based on isothermal amplification technologies for CT and NG is being developed.[36]

HIV

The Ora-Quick HIV test is an FDA approved POCT that detects both HIV-1 and 2 in 20 min, (specificity - 99.98% and sensitivity - 93%). A POCT based on NAAT is being developed for pediatric setting. A simplified technology for CD4 count testing and viral load assay is also in the offing.[36]

Point-of-care tests for other sexually transmitted infections

A self-testing POCT kit for Trichomonas vaginalis is available and can be easily used with training. A POCT for Bacterial vaginosis, which detects the sialase activity in vaginal fluid, although shown to have excellent sensitivity (88%) and specificity (95%) in comparison to Gram-stain, has no substantial evidence on its linkage to care.[30,36]

Point-of-care tests in the pipeline

A multi-assay, battery-operated device may soon become available with fully-automated test-specific cartridges, bar-codes, built-in internal controls, an analyzer, and bar-code.[37]

Another novel technology, a microwave accelerated, metal-enhanced fluorescence test (MAMEF), is a microwave based cell lysis and DNA fragmentation, followed by DNA detection.[38]

There are still some challenges to be addressed in POCTs, such as, quality assurance methods, linkage to patient care, and applications for partner services and surveillance.

CONCLUSION

With the increasing availability of newer diagnostic technologies, we are on the verge of a major change in the approach to STI control. When diagnostic methods are faster and results more accurate, they are bound to improve patient care. As automation and standardization increase and human error decreases, more laboratories will adopt molecular testing methods. An effective STI control strategy is based on an accessible and well-trained healthcare workforce, suitable infrastructure, partner notification, disease surveillance, health promotion and outbreak investigation. For this, primary care physicians will continue to play a crucial role in ensuring the success of this important program.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: The author reports no conflict of interest relevant to this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Steen R, Wi TE, Kamali A, Ndowa F. Control of sexually transmitted infections and prevention of HIV transmission: Mending a fractured paradigm. Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87:858–65. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.059212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marfatia YS, Naik E, Singhal P, Naswa S. Profile of HIV seroconcordant/discordant couples a clinic based study at Vadodara, India. Indian J Sex Transm Dis. 2013;34:5–9. doi: 10.4103/2589-0557.112862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grulich AE, Jin F, Conway EL, Stein AN, Hocking J. Cancers attributable to human papillomavirus infection. Sex Health. 2010;7:244–52. doi: 10.1071/SH10020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012. World Health Organization. Global incidence and prevalence of selected curable sexually transmitted infections-2008. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. World Health Organization. Global strategy for the prevention and control of sexually transmitted infections, 2006-2015. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuypers J, Gaydos CA, Peeling RW. Principles of laboratory diagnosis of STIs. In: Holmes KK, editor. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 4th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical; 2008. pp. 937–58. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pierce EF, Katz KA. Darkfield microscopy for point-of-care syphilis diagnosis. MLO Med Lab Obs. 2011;43:30–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wheeler HL, Agarwal S, Goh BT. Dark ground microscopy and treponemal serological tests in the diagnosis of early syphilis. Sex Transm Infect. 2004;80:411–4. doi: 10.1136/sti.2003.008821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wicher K, Horowitz HW, Wicher V. Laboratory methods of diagnosis of syphilis for the beginning of the third millennium. Microbes Infect. 1999;1:1035–49. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(99)80521-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tapsall J. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001. Antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malhotra M, Sood S, Mukherjee A, Muralidhar S, Bala M. Genital Chlamydia trachomatis: An update. Indian J Med Res. 2013;138:303–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lewis DA. Chancroid: Clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and management. Sex Transm Infect. 2003;79:68–71. doi: 10.1136/sti.79.1.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Unemo M, Ballard R, Ison C, Lewis D, Ndowa F, Peeling R. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. Laboratory Diagnosis of Sexually Transmitted Infections, Including Human Immunodeficiency Virus. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh A, Preiksaitis J, Ferenczy A, Romanowski B. The laboratory diagnosis of herpes simplex virus infections. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2005;16:92–8. doi: 10.1155/2005/318294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ashley RL. Sorting out the new HSV type specific antibody tests. Sex Transm Infect. 2001;77:232–7. doi: 10.1136/sti.77.4.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Farrell N. Donovanosis. Sex Transm Infect. 2002;78:452–7. doi: 10.1136/sti.78.6.452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sobel JD. Vulvovaginal candidosis. Lancet. 2007;369:1961–71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60917-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Svenstrup HF, Dave SS, Carder C, Grant P, Morris-Jones S, Kidd M, et al. A cross-sectional study of Mycoplasma genitalium infection and correlates in women undergoing population-based screening or clinic-based testing for Chlamydia infection in London. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e003947. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mahlen SD. Applications of molecular diagnostics. In: Mahon CR, Lehman DC, Manuselis G, editors. Text book of Diagnostic Microbiology. 3rd ed. St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier Publishers; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kiechle FL. What is molecular diagnostics? [Last accessed on 2014 May 29]. Available from: http://www.gomolecular.com/discover/what_is_molecular_diagnostics.html .

- 21.Quinn TC. Recent advances in diagnosis of sexually transmitted diseases. Sex Transm Dis. 1994;21:S19–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Millar BC, Xu J, Moore JE. Molecular diagnostics of medically important bacterial infections. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2007;9:21–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gill P, Ghaemi A. Nucleic acid isothermal amplification technologies: A review. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids. 2008;27:224–43. doi: 10.1080/15257770701845204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cho JC, Tiedje JM. Bacterial species determination from DNA-DNA hybridization by using genome fragments and DNA microarrays. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:3677–82. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.8.3677-3682.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tabrizi SN, Unemo M, Limnios AE, Hogan TR, Hjelmevoll SO, Garland SM, et al. Evaluation of six commercial nucleic acid amplification tests for detection of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and other Neisseria species. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:3610–5. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01217-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bowden FJ, Tabrizi SN, Garland SM, Fairley CK. Infectious diseases 6: Sexually transmitted infections: New diagnostic approaches and treatments. Med J Aust. 2002;176:551–7. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2002.tb04554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schachter J, Moncada J, Liska S, Shayevich C, Klausner JD. Nucleic acid amplification tests in the diagnosis of chlamydial and gonococcal infections of the oropharynx and rectum in men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35:637–42. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31817bdd7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muralidhar S, Talwar R, Kumar DA, Kumar J, Bala M, Khan N, et al. Genital ulcer disease: How worrisome is it today. A status report from New Delhi, India? J Sex Transm Dis. 2013:8. doi: 10.1155/2013/203636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Talaro KP, Talaro A. Foundations in Microbiology. 4th ed. New York: McGraw Hill; 2002. Tools of the laboratory: The methods for studying microorganisms; pp. 58–86. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hobbs MM, Seña AC. Modern diagnosis of Trichomonas vaginalis infection. Sex Transm Infect. 2013;89:434–8. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2013-051057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gazi H, Degerli K, Kurt O, Teker A, Uyar Y, Caglar H, et al. Use of DNA hybridization test for diagnosing bacterial vaginosis in women with symptoms suggestive of infection. APMIS. 2006;114:784–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2006.apm_485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huppert J, Hesse E, Gaydos CA. What's the point How point-of-care STI tests can impact infected patients? Point Care. 2010;9:36–46. doi: 10.1097/POC.0b013e3181d2d8cc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peeling RW, Holmes KK, Mabey D, Ronald A. Rapid tests for sexually transmitted infections (STIs): The way forward. Sex Transm Infect. 2006;82 Suppl 5:v1–6. doi: 10.1136/sti.2006.024265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hsieh YH, Hogan MT, Barnes M, Jett-Goheen M, Huppert J, Rompalo AM, et al. Perceptions of an ideal point-of-care test for sexually transmitted infections – A qualitative study of focus group discussions with medical providers. PLoS One. 2010;5:e14144. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.The Use of Rapid Syphilis Tests. The Sexually Transmitted Diseases Diagnostic Initiative (SDI). Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases (TDR) Sponsored by UNICEF/UNDP/World bank/WHO. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Castro AR, Esfandiari J, Kumar S, Ashton M, Kikkert SE, Park MM, et al. Novel point-of-care test for simultaneous detection of nontreponemal and treponemal antibodies in patients with syphilis. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:4615–9. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00624-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tucker JD, Bien CH, Peeling RW. Point-of-care testing for sexually transmitted infections: Recent advances and implications for disease control. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2013;26:73–9. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e32835c21b0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang Y, Agreda P, Kelley S, Gaydos C, Geddes CD. Development of a microwave-accelerated metal-enhanced fluorescence 40 second, <100 cfu/ml point of care assay for the detection of Chlamydia trachomatis. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2011;58:781–4. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2010.2066275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]