Abstract

Bismuth triple therapy was the first truly effective Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy. The addition of a proton pump inhibitor largely overcame the problem of metronidazole resistance. Resistance to its being the primary first line therapy have centered on convenience (the large number of tablets required) and side effects causing difficulties with patient adherence. Understanding why the regimen is less successful in some regions remains unexplained in part because of the lack of studies including susceptibility testing. A number of modifications have been proposed such as twice-a-day therapy which addresses both major criticism but the studies with susceptibility testing required to prove its effectiveness in high metronidazole resistance areas are lacking. Most publications lack the data required to understand why they were successful or failed (e.g., detailed resistance and adherence data) and are therefore of little value. We discuss and provide recommendations regarding variations including substitution of doxycycline, amoxicillin, and twice a day therapy. We describe what is known and unknown and provide suggestions regarding what is needed to rationally and effectively use bismuth quadruple therapy. Its primary use is when penicillin cannot be used or when clarithromycin and metronidazole resistance is common. Durations of therapy less than 14 days are not recommended.

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, therapy, bismuth, tetracycline, metronidazole, proton pump inhibitors, side effects, adherence, antimicrobial resistance, susceptibility testing, review

Background

Eberle, in 1834, noted that bismuth, primarily as the white oxide, was introduced into medicine in 1697 by Jacobi and that its use was later popularized by Drs. Odier of Geneva and De la Roche, of Paris 1. Throughout the 19th century, bismuth salts were widely and successfully used in gastroenterology 2. Bismuth continued to be used as a primary or adjuvant therapy for dyspepsia and peptic ulcer until being replaced successively by antacids, histamine-2 receptor antagonists, and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). Bismuth also had a long history of use as an antimicrobial especially for the treatment of syphilis 3. In the United States bismuth subsalicylate (e.g., as Pepto Bismol) was also used for dyspepsia and diarrhea and later to treat and prevent travelers diarrhea 4. In travelers diarrhea bismuth was shown to function as a topical antimicrobial thus linking its use as an anti-infective to it subsequent use for treatment of H. pylori-related peptic ulcer disease 5-7.

The most widely used forms of bismuth in use for gastroenterology at the time of the discovery of H. pylori were bismuth subnitrate, subsalicylate, and subcitrate. In the 1970s, Gist-Brocades introduced a proprietary preparation of colloidal bismuth subcitrate (De-Nol) as an anti-ulcer therapy by Gist-Brocades in the 1970's. The original De-Nol formulation was a colloidal suspension in ammonia water and had the very pungent odor of ammonia. This was also a time of great interest in ulcer pathogenesis and ulcer treatments. Many groups were also active in the study of ulcer in experimental animals. Colloidal bismuth subcitrate was shown to be able to coat and thus potentially protect the ulcer base, a property not seen with other bismuth preparations 8-11. Over time, the list of its properties potentially important in the treatment of peptic ulcer grew large (Box 1) 12.

Box 1. Pharmacodynamic properties reported for bismuth subcitrate.

Bactericidal effect on H. pylori

Binding to the ulcer base

Inactivation of pepsin

Binding of bile acids

Stimulation of prostaglandin biosynthesis

Suppression of leukotriene biosynthesis

Stimulation of complexation with mucus

Inhibition of various enzymes

Binding of epithelial growth factor

Stimulation of lateral epithelial growth

Bismuth in the era of new concepts regarding pathogenesis and treatment of peptic ulcer

In the mid-20th century, peptic ulcer and its complications was a major medical problem in western countries. The importance of peptic ulcer was illustrated by the awarding of a Nobel prize to James Black in 1988 for the discovery of the histamine-2 receptor antagonists (in 1972) and for beta blockers (in 1964). The late 1970's and early 1980's saw the introduction of a number of new anti-ulcer agents (e.g., sucralfate, histamine-2 receptor antagonists, synthetic prostaglandins, a tablet formulation of De-Nol, and finally the PPIs). An epidemic of bismuth neurotoxicity occurred in France which lead to the removal of bismuth from many countries 3;13. However, in Europe considerable interest in colloidal bismuth subcitrate continued based on studies showing that both endoscopically and histologically ulcer healing was more complete and recurrences less frequent following treatment with DeNol compared to other agents. One particularly important comparison of liquid colloidal bismuth subcitrate and cimetidine randomized 46 patients with active duodenal ulcers 14. Forty (25 cimetidine, 15 bismuth) had symptomatic follow-up and 39 had endoscopic follow-up for up to 1 year. Ulcer relapse confirmed by endoscopy occurred in 79% of the cimetidine group compared to 27% of those received bismuth. Most importantly, H. pylori was present at follow-up in 100% of those who received cimetidine whereas 10 of the 15 receiving bismuth (43%) showed healing of gastritis, elimination of H. pylori, and no ulcer relapse at the 1 year follow-up. At that time peptic ulcer disease was thought to be incurable; “once an ulcer, always an ulcer” was the current dogma. Those results showed that the natural history of ulcer might be changed and provided a potential biologic basis for observation of a reduced rate of ulcer relapse following ulcer healing with bismuth subcitrate 15-22. It also was a harbinger of the results of subsequently published randomized studies proving that H. pylori eradication prevented duodenal and gastric ulcer recurrences among those not also taking NSAIDs 23.

The initial trials of bismuth as an antimicrobial therapy for H. pylori eradication reported H. pylori eradication rates ranging from 10% to 30% 12. However, the duration of those early experiments were typically short and subsequent experience has suggested that these were either possibly over estimated, or changes in the formulation of bismuth subcitrate (e.g., from liquid to tablet) may have reduced its effectiveness. Because the liquid formulation was not well accepted by patients it was replaced by a “swallow tablet” produced by spray drying the liquid preparation. The fact that long term follow-up of duodenal ulcer recurrence identified late recurrences and loss of statistical significance compared to H2-receptor antagonists 18 are consistent with current notions that bismuth alone rarely cures H. pylori infections and that all currently available preparations are similar in anti-H. pylori effect. However, head to head comparisons of bismuth preparation alone or part of multi-drug therapy are generally lacking. As noted above, following the epidemic of bismuth neurotoxicity in France 3, many countries removed all bismuth preparations from their pharmacopeias and thus bismuth compounds are not universally available for the treatment of H. pylori infections. When used short term as for anti-H. pylori therapy bismuth therapy has proven to be both safe and effective.

Bismuth quadruple therapy for H. pylori eradication

Starting in the mid to late 1980s, there were numerous clinical trials attempting to cure H. pylori infections 12. When a single antibiotic proved ineffective, dual and triple drug therapies were tried and eventually an effective regimen consisting of bismuth subcitrate, tetracycline and metronidazole was identified by Tom Borody in Australia 12;24;25. That original study used bismuth subcitrate 120 mg and tetracycline 500 mg both q.i.d. for 28 days and metronidazole 200 mg q.i.d. for 14 days. They reported a success rate of 94 of 100 subjects. Subsequently, metronidazole resistance was found to reduce the regimens effectiveness. However, the addition of a PPI proved to enhance its effectiveness irrespective of the presence or absence of metronidazole resistance 26;27. The regimen, often called bismuth quadruple therapy consist of a PPI, a bismuth, metronidazole and tetracycline. The dosages, duration of therapy and administration in relation to meals differs as will be discussed below.

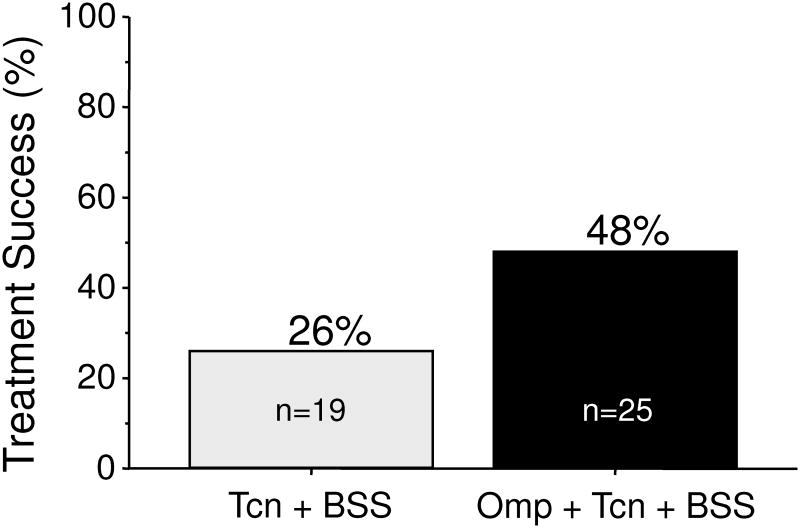

Antimicrobial resistance generally renders that particular antibiotic ineffective for resistant infections (e.g., it functionally drops out of the regimen). The fact that the addition of a PPI appeared to negate the effect of metronidazole resistance suggested that metronidazole was possibly unnecessary and that the combination of a PPI, bismuth, and tetracycline components might suffice. That hypothesis was examined in 44 patients with peptic ulcer disease who received either tetracycline 500 mg and bismuth subsalicylate (Pepto Bismol) 2 tablets both q.i.d. with or without omeprazole 40 mg in the a.m. for 14 days. The overall cure rate was 48% which was clinically unacceptably low. However, the addition of omeprazole was able to approximately double the efficacy of tetracycline and bismuth dual therapy (Figure 1) 28.

Figure 1. Effect of removing the metronidazole and or the PPI from bismuth quadruple therapy.

Peptic ulcer patients received either TCN (tetracycline HCl 500 mg, q.i.d, and BSS (bismuth subsalicylate (Pepto Bismol) 2 tablets q.i.d. with or without Omp (omeprazole 40 mg in the a.m.) for 14 days.

Data from Al-Assi MT, Genta RM, Graham DY. Short report: omeprazole-tetracycline combinations are inadequate as therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1994;8:259-262.

Even today, it remains unclear how the PPI helps overcome metronidazole resistance. Metronidazole is a prodrug activated by enzymes within the bacterial cell. Resistance as assessed in vitro is associated with inactivation of one or more of those enzymes. Part of its effectiveness may be topical and the concentration of metronidazole present in the stomach is very high suggesting that as yet recognized enzyme pathways in the bacterial cell remain or become active at increased pH. The ability to partially overcome resistance is both metronidazole dose and treatment duration dependent 29-33. It is also unclear whether the ability to overcome the effect of metronidazole resistance is largely restricted to bismuth-containing regimens or even to bismuth - tetracycline containing regimens. The Homer study examined omeprazole, metronidazole and amoxicillin (i.e., no bismuth) and also showed an overall effect of dose and duration on effectiveness but the benefit was not directly related to improved outcomes with resistant strains34.

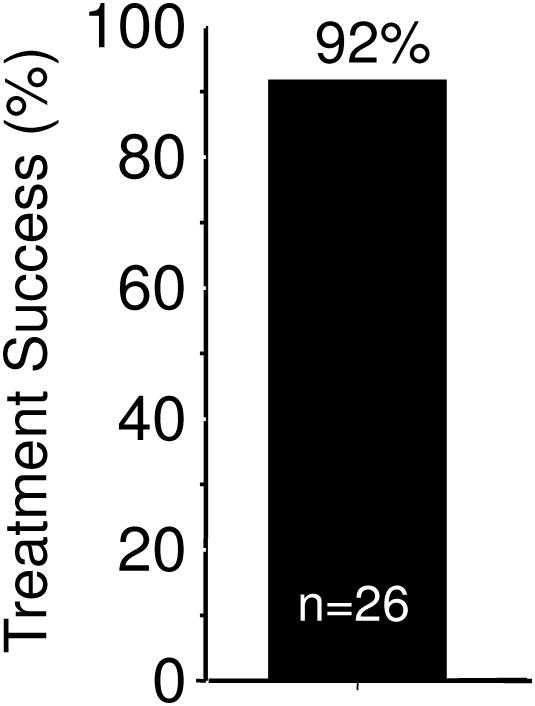

When H. pylori infected subjects with pretreatment confirmed metronidazole resistant infections received a 14 day bismuth quadruple regimen consisting of tetracycline 500 mg and bismuth subsalicylate (Pepto Bismol) 2 tablets both q.i.d. with meals, plus metronidazole 500 mg t.i.d. and omeprazole 20 mg in the a.m., the cure rate was 92% (Figure 2)29 which was approximately what was expected in a metronidazole susceptible population (there was no control group). This direct experiment confirm that the addition of a PPI could partially or possibly completely negate the deleterious effects of metronidazole resistance in bismuth quadruple therapy. Another experiment with 43 metronidazole resistant strains (77% with MIC ≥256 by Etest) reported a per protocol cure rate of 92.1% (81.4% ITT) 35. Two subjects dropped out after 7 days and both failed therapy. A large study from China found studies a large population of subjects with multidrug resistant H. pylori (susceptible to amoxicillin and tetracycline) and reported that among 101 patient with metronidazole resistant strains 14 day bismuth quadruple therapy cured 93.1% per protocol, which was similar to the effectiveness of bismuth quadruple therapy where amoxicillin was substituted for metronidazole (i.e., 94.6% of 93 subjects per protocol) 36.

Figure 2. Effect of 14-day bismuth quadruple therapy in patients with pretreatment proven metronidazole resistant infections.

Therapy consisted of tetracycline HCL 500 mg and bismuth subsalicylate (Pepto Bismol) 2 tablets both q.i.d. with meals, plus metronidazole 500 mg t.i.d. and omeprazole 20 mg in the a.m.. Data from Graham DY, Osato MS, Hoffman J, et al. Metronidazole containing quadruple therapy for infection with metronidazole resistant Helicobacter pylori: a prospective study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2000;14:745-750.

The effect of metronidazole resistance as examined by meta-analysis

A number of meta-analyses involving bismuth quadruple therapy have focused on understanding the results in terms of antimicrobial resistance (e.g., 31-33;37). The beneficial effect of adding a PPI in relation to metronidazole resistance was confirmed in an analysis of 93 studies (10,178 participants) that showed that metronidazole resistance reduced efficacy of bismuth, metronidazole, tetracycline therapy (of different durations and dosing) on average by 26%. The reduction was only 14% following the addition of a gastric acid inhibitor and it was concluded that even in areas with a high prevalence of metronidazole resistance, the quadruple regimen plus a PPI eradicated more than 85% of H. pylori infections when given for 10-14 days 37.

Calculation of the effectiveness of bismuth quadruple therapy

In most western countries and in Korea and China the an unsatisfactory outcome with bismuth quadruple therapy (e.g., <90% or <85% treatment success per protocol) can be identified if one examines the duration of therapy, the doses used, patient adherence to the regimen and whether metronidazole resistance was present. With clarithromycin-containing triple and quadruple therapies the outcome can be reliably predicted provided one has data concerning the effectiveness of that therapy in relation to antimicrobial resistance (i.e., with susceptible strains and with resistance with each individual antimicrobial and with combinations of antimicrobials) 38;39. Similar calculations can theoretically be made for bismuth quadruple therapy based on the duration and the effectiveness of therapy in the presence of metronidazole resistance. Unfortunately, there is a paucity of data even from western countries and essentially from areas where tetracycline resistance is likely to be an issue (e.g., Iran or Turkey).

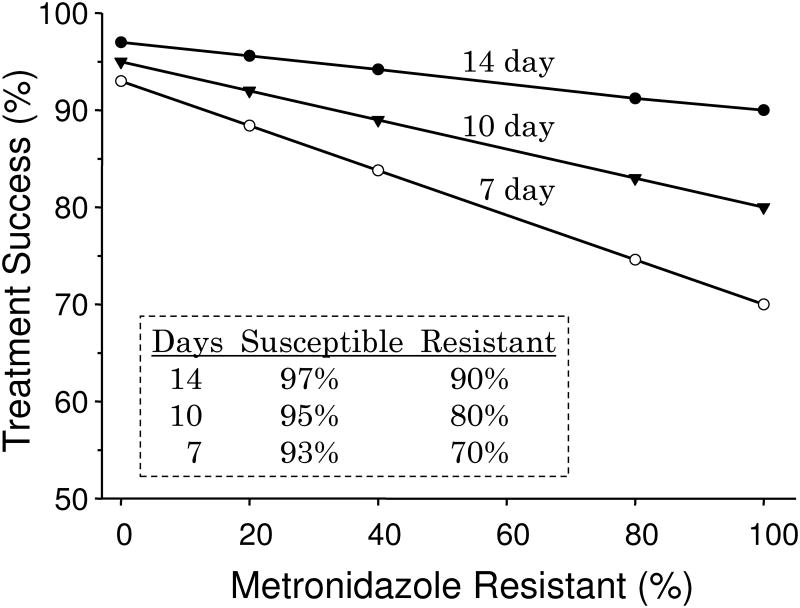

The data for Figure 3 was derived empirically from the results of clinical trials but provides reasonably accurate estimation in areas where bismuth quadruple therapy produces 90% or greater results with 14 day and full dose therapy. The formula is [(success rate with susceptible strains times proportion with susceptible strains) + (success rate with resistant strains time proportion with resistant strains) = outcome per protocol]. For example, for a 7 day regimen with 25% resistant strains (i.e., 75% susceptible) the result would be (75 × 93%) + (25 × 70%) or ∼87% per protocol. It shows that the population result (per protocol) is expected to fall below 90% with 10 day therapy with 40% metronidazole resistance or below 90% with 7 day therapy with 20% metronidazole resistance. Intention to treat results would be expected to be somewhat lower. The cure rate of those individuals with resistant strains receiving 7 and 10 day therapy would be approximately 70% and 80% respectively suggesting that if metronidazole resistance is possibly present and 14 day therapy would be the most prudent recommendation. Poor adherence (e.g., the patient taking on 5 days of a 14 day prescription) would have a marked effect on outcome and as side effects are common, poor adherence is a major issue with bismuth quadruple therapy. Another factor that would influence the outcome is the method used to assess metronidazole resistance. Assessment by Etest tends to over estimate the presence of metronidazole resistance. For example in one study 20 of the 37 subjects test (54%) were judged to be metronidazole resistant by Etest and only 12 were confirmed by agar dilution 40. In a large study the change in susceptibility result was approximately 17% 41. We recommend that for clinical trials all resistance results with Etest be confirmed with agar dilution 40.

Figure 3. Empirically derived estimation of effectiveness of 14-day bismuth quadruple therapy in regions where success is known to be dependent on doses, duration, metronidazole resistance, and adherence.

The formula is [(success rate with susceptible strains times proportion with susceptible strains) + (success rate with resistant strains time proportion with resistant strains) = outcome per protocol].

Adherence (compliance) with bismuth quadruple therapy

Adherence to the protocol

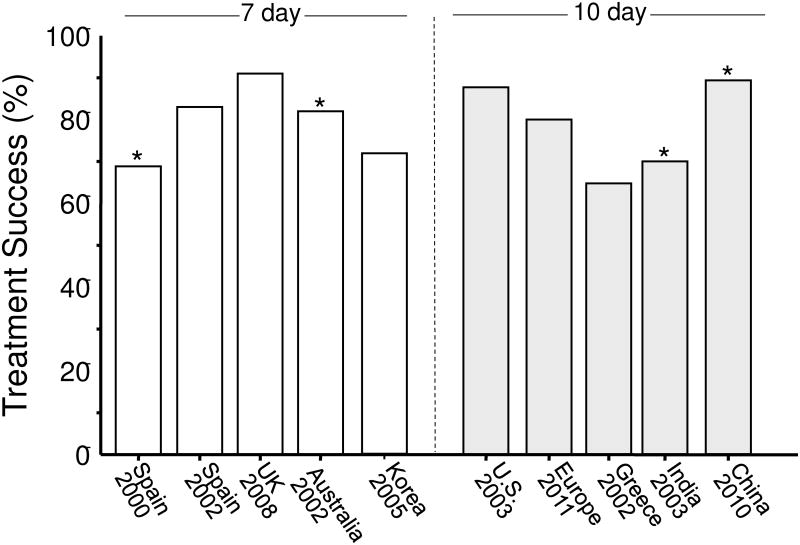

Many anti-H. pylori regimens are somewhat complicated and require taking drugs 2 to 4 times daily. In order to achieve the high degrees of success reported in clinical studies it is important the both the clinician and the patient adhere to the details of successful protocols. Arbitrary changes in the protocol (e.g., dose, duration, formulation) are similar to making arbitrary changes in a published recipe for French bread and then being surprised when the product is less than anticipated. Figure 4 shows the outcome (ITT) of the bismuth quadruple therapy arms of recent comparative trials with legacy triple therapy 42. When one examines the details of the studies, one finds that what was called bismuth quadruple therapy often differed in terms of doses given. These studies used either 7 or 10 days to be the same as the triple therapy despite the evidence that all of these regimens do better with 14 days.

Figure 4. Intention-to-treat results of recent studies of 7 or 10 day bismuth quadruple therapy with various doses and drugs used for the comparison against clarithromycin-containing triple therapy generally in areas of high clarithromycin and variable metronidazole resistance.

Data from Malfertheiner P, Bazzoli F, Delchier JC, et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication with a capsule containing bismuth subcitrate potassium, metronidazole, and tetracycline given with omeprazole versus clarithromycin-based triple therapy: a randomised, open-label, non-inferiority, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2011;377:905-913; and original study publications.

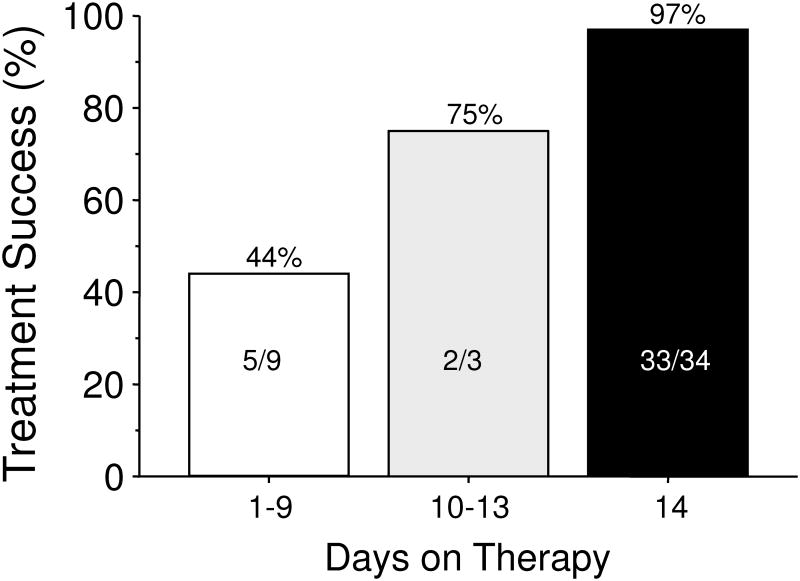

From the first part of this paper, one would expect outstanding results from bismuth quadruple therapy and here neither 7 nor 10 day regimens provided acceptably high intention to treat success. An example is a 14 day treatment trial using a formulation in which the antibiotics and bismuth are contained within the same capsules (i.e., Pylera) and omeprazole 20 mg b.i.d. 43. Forty-seven subjects were entered and 12 (25.5%) failed to take the planned 14 days of therapy. The most common for early stopping was the presence of an adverse event. As would be expected, treatment success increased as the duration of therapy increased (Table 1, Figure 5) 43. The cure rate ITT was 70% and PP was >95%. All those with metronidazole resistant strains who completed therapy were cured.

Table 1. Duration of Therapy and Treatment Success.

| Days therapy Completed | Status | Total | Reason Stopped | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Infected | Eradicated | |||

| 2 | 2*Both | 0 | 2 | Adverse events |

| 3 | 1* | 0 | 1 | |

| 6 | 0 | 2 | 2 | Adverse event |

| 7 | 1** | 0 | 1 | Adverse event |

| 8 | 0 | 2 | 2 | |

| 9 | 1* | 0 | 1 | Adverse event |

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 11 | 1** | 0 | 1 | Protocol violation |

| 12 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| 13 | 0 | 2 | 2 | |

| 14 | 1* | 33 | 34 | Completed study |

|

| ||||

| Total | 7 | 40 | 47 | |

= susceptible,

= resistant

Figure 5. Effect of treatment duration on treatment success of bismuth quadruple therapy.

Therapy consisted of bismuth quadruple therapy (Pylera) plus omeprazole 20 mg b.i.d. for 14 days. Thirty-nine percent of strains cultured were metronidazole resistance. All (100%) of those receiving therapy for 14 days with resistant strains were cured. The duration of therapy was patient-determined based on withdrawal for side effects or other reasons. The number and success for each duration is shown.

Data from Salazar CO, Cardenas VM, Reddy RK, Dominguez DC, Snyder LK, Graham DY. Greater than 95% success with 14-day bismuth quadruple anti-Helicobacter pylori therapy: A pilot study in US Hispanics. Helicobacter 2012;17:382-389.

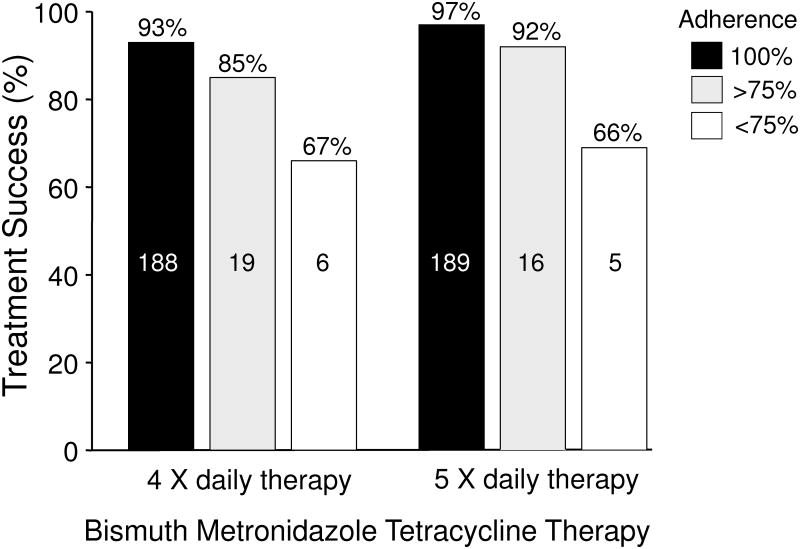

Soon after the introduction of bismuth, metronidazole, and tetracycline therapy it became apparent that side effects were common; side effects tend to cause reduce adherence to the regimen prescribed. With the exception of temporary discoloration of the tongue, bismuth is generally an innocuous medication when used for term use therapy. In contrast, tetracycline and metronidazole either separately or together frequently are associated with complaints. As part of the initial development of the regimen, Borody et al. examined whether increasing the frequency of administration without increasing the dosages would improve adherence 44. They compared two 14 day regimes of 4 vs. 5 drug administrations per day (between 7 a.m. and 11 p.m.). The doses used were 108 mg of bismuth subcitrate in both arms, 500 mg of tetracycline q.i.d. vs. 250 mg 5 times daily, and 250 mg of metronidazole q.i.d. vs. 200 mg 5 times per day (i.e., the total amount of tetracycline was reduced from 2 g to 1.25 g, the dose of metronidazole was 1 gram but was less per dose. The antisecretory agent was ranitidine 300 mg at night; resistance was presumably rare). The per protocol cure rate was slightly higher with the 5 day regimen (96% vs. 92%, P = 0.07) (Figure 6) 44. More importantly, side effects were significantly reduced (P <0.001) suggesting that it is possible to provide a more acceptable regimen. de Boer who performed many of the initial Dutch trials examining dose, duration and the use of PPI's, used a 7-point approach of patient education/motivation starting with taking time to talk to the patient and explain the rationale. He then went on to explain the potential difficulties and side effects that might occur and provided details about how to take the medications 45. He and Borody had good but not perfect adherence. It was previously shown that structured counseling and follow-up resulted in improved outcomes with clarithromycin triple therapy 46. Their results are likely applicable to all H. pylori therapies.

Figure 6. Results of changing the doses and timing of administration and adherence on outcome of bismuth triple therapy plus ranitidine.

Therapy consisted of two 14 day regimes of 4 vs. 5 drug administrations per day (between 7 a.m. and 11 p.m.). The doses used were 108 mg of bismuth subcitrate in both arms, 500 mg of tetracycline q.i.d. vs. 250 mg 5 times daily, and 250 mg of metronidazole q.i.d. vs. 200 mg 5 times per day (i.e., the total amount of tetracycline was reduced from 2 g to 1.25 g, the dose of metronidazole was 1 gram but was less per dose plus ranitidine 300 mg at night.

Data from Borody TJ, Brandl S, Andrews P, et al. Use of high efficacy, lower dose triple therapy to reduce side effects of eradicating Helicobacter pylori. Am J Gastroenterol 1994;89:33-38.

One approach to enhance compliance is to enhance convenience. Triple therapy has long been available in dose packs. The US commercial formulation bismuth quadruple therapy was also formulated in a convenience pack (Helidac) and the newer formulation Pylera is prepackaged into capsules containing bismuth subcitrate potassium, metronidazole, and tetracycline 42;43. None of these packs have proven to improve adherence or result in a clear reduction in side effects. Studies of compliance have not shown that reduced adherence was related to the number of tablets per day required for H. pylori quadruple therapy 32;37. The number of tablets/capsules per day can also be reduced in traditional therapy by using 500 mg/capsule of tetracycline and of metronidazole and bismuth b.i.d. (e.g., 36) to be equal to or less than that needed for current prepackaged quadruple therapy products.

All H. pylori regimens are associated with side effects. A meta-analysis recently compared the side effects of bismuth quadruple therapy with other common H. pylori regimens and reported that side effects were not greater with the exception of the cosmetic event, black stools. This confirmed the results of prior meta-analyses 31;32;37;47-49. Despite these encouraging words, those taking care of patients with H. pylori recognized that all the regimens have a high incidence of side effects and that failure to motivate the patients regarding finishing the regimen often results in drop outs and in clinical studies, loss to follow-up 42;43 that can likely be reduced by patient education 50.

How to make bismuth quadruple therapy more acceptable

As noted previously, Borody et al. attempted to reduce the side effects by changing the frequency of dose administration and the doses with some success. The current “standard regimen” consists of a PPI b.i.d., tetracycline 500 mg q.i.d., at least 1,500 of metronidazole, and bismuth q.i.d.. Shorter durations have been recommended but this is generally a marketing ploy as bismuth quadruple therapy is generally reserved for patients where metronidazole resistance is likely and duration and doses are important for excellent outcome 51. While 14 days of full dose therapy might be ideal, duration and dose of metronidazole have not been systematically examined in relation to metronidazole resistance. There are in fact some data suggesting that the doses considered ideal may be more than necessary. For example, there are a number of trials in which bismuth quadruple therapy was administered twice rather than 3 or 4 times a day (Table 2) 40;52-58. We show data from 11 arms and 9 studies (Table 2). Cure rates for 10-14 day studies were over 86% PP except in one instance where a low dose PPI was used. Seven day appeared to be possibly inferior to 10 or 14 days. Drugs included bismuth subcitrate and bismuth subsalicylate, 1 to 1.5 grams of tetracycline, and 800 to 1000 mg of metronidazole along with full dose PPI except in the one instance where lansoprazole 15 mg b.i.d. was used. Studies were done in high [China, Turkey, and Italy (Sardinia)] and moderate metronidazole resistance areas (USA). Clearly, comparative studies are needed to assess efficacy as well as side effects in comparison to three and four times daily bismuth quadruple therapy and to address whether a.m. and p.m. and noon and p.m. administrations are equivalent. In these studies drugs were given with or after meals. The was also one study of b.i.d. omeprazole 20 mg, amoxicillin 1 g as a substitute for tetracycline, tinidazole 500 mg and bismuth subcitrate 240 mg givem every 12 hours for only 7 days that achieved a PP cure rate of 86% (84.1% ITT) that was not followed up with another study of longer duration 59.

Table 2. Summary of b.i.d. bismuth-containing traditional quadruple therapies.

| Year | Location | Bismuth* | Tetracyc | Metro | Meals | PPI** | Days | # | PP% | ITT% | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1997 | USA | BSS 524 b.i.d. | 500 b.i.d. | 500 b.i.d. | a.m., p.m. | L 15 b.i.d. | 10 | 46 | 75 | 70 | 110 |

| 2002 | Italy | BSC 240 b.i.d. | 500 b.i.d. | 500 b.i.d. | Noon, p.m. | P 20 b.i.d. | 14 | 118 | 98 | 95 | 52 |

| 2003 | Italy | BSC 240 b.i.d. | 500 b.i.d. | 500 b.i.d. | Noon, p.m. | P 20 b.i.d. | 14 | 71 | 97 | 93 | 53 |

| 2004 | USA | BSS 524 b.i.d. | 500 b.i.d. | 500 b.i.d. | a.m., p.m. | R 20 b.i.d. | 14 | 37 | 92.3 | 92.3 | 110 |

| 2006 | Italy | BSC 240 b.i.d. | 500 b.i.d. | 500 b.i.d. | a.m., p.m. | E 20 b.i.d. | 10 | 95 | 95 | 91 | 55 |

| 2009 | China | BSC 220 b.i.d. | 750 b.i.d. | 400 b.i.d. | a.m., p.m. | P 40 b.i.d | 7 | 43 | 82.9 | 79.1 | 57 |

| 2009 | China* | BSC 220 b.i.d. | 750 b.i.d. | 400 b.i.d. | a.m., p.m. | P 40 b.i.d | 10 | 45 | 90.9 | 88.9 | 57 |

| 2010 | China* | BSC 220 b.i.d. | 750 b.i.d. | 400 b.i.d. | a.m., p.m. | P 40 b.i.d | 10 | 85 | 91.6. | 89.9 | 58 |

| 2011 | Italy | BSC 240 b.i.d. | 500 b.i.d. | 500 b.i.d. | Noon, p.m. | P 20 b.i.d. | 14 | 202 | 98 | 92 | 111 |

| 2011 | Italy | BSC 240 b.i.d. | 500 b.i.d. | 500 b.i.d. | Noon, p.m. | P 20 b.i.d. | 10 | 215 | 95 | 92 | 111 |

| 2013 | Turkey | BSC 600 b.i.d. | 500 b.i.d. | 500 b.i.d. | a.m., p.m. | O 20 b.i.d. | 14 | 38 | 86.8 | 73.3 | 112 |

| 2005 | Iran | BSC 240 b.i.d. | 500 b.i.d. | 500 b.i.d | a.m., p.m. | O 20 b.i.d. | 14 | 76 | - | 76.3 | 113 |

| 2006 | Iran* | BSC 240 b.i.d. | 750 b.i.d. | 500 b.i.d. | a.m., p.m. | O 20 b.i.d. | 3 | 40 | 54 | 50 | 75 |

| 2006 | Iran* | BSC 240 b.i.d. | 750 b.i.d. | 500 b.i.d. | a.m., p.m. | O 20 b.i.d. | 7 | 41 | 45.9 | 41.4 | 75 |

| 2006 | Iran* | BSC 240 b.i.d. | 750 b.i.d. | 500 b.i.d. | a.m., p.m. | O 20 b.i.d. | 14 | 40 | 40 | 35 | 75 |

Doses are in mg

BSC= Bismuth Subcitrate, BSS = Bismuth Subsalicylate, Tetracyc = tetracycline, Metro = metronidazole

P = pantoprazole, R = rabeprazole, L = lansoprazole, O = omeprazole

extension of the same study

These results cannot be considered generalizable until the results can be correlated with metronidazole susceptibility; further studies without concomitant susceptibility testing should be strongly discouraged. Twice a day therapy offers the potential of effectiveness, less cost, and fewer side effects.

Doxycycline

The original experience with doxycycline was that it could not substitute successfully for tetracycline in bismuth triple therapy 60. Since that time it has been recommended not to substitute doxycycline for tetracycline. However, randomized trials comparing tetracycline and doxycycline in full dose 14 day traditional bismuth quadruple therapy are lacking. In the US, tetracycline has often became largely unavailable and many pharmacies attempted to substitute doxycycline for tetracycline HCl. In our experience, that substitution led to unsatisfactory results. Most available doxycycline data relates to substitution of doxycycline for tetracycline and amoxicillin for metronidazole all given b.i.d. 61-63 (Table 3). The three studies from Italy suggest that this might be an effective regimen whereas the one from China did not. The study from China, a high metronidazole resistance country, also compared 10 day therapy with doxycycline or tetracycline and the results were both poor 64. Further studies with 14 day therapy and with 200 mg of doxycycline b.i.d. are needed. However, to be useful they must also provide susceptibility testing to that the results can be correlated with metronidazole susceptibility/resistance. Before doxycycline can be recommended as part of traditional bismuth quadruple therapy studies that include susceptibility data are needed; until then doxycycline is probably best avoided.

Table 3. Summary of b.i.d. PPI, bismuth, doxycycline and amoxicillin containing quadruple therapies.

| Year | Location | Bismuth* | Doxycyc | Amox | Meals | PPI** | Days | # | PP | ITT | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | Italy | BSC 240 b.i.d. | 100 b.i.d. | 1000 b.i.d. | a.m., p.m. | 0 20 b.i.d. | 7 | 89 | 92 | 91 | 61 |

| 2009 | Turkey | RBC 400 b.i.d | 100 b.i.d. | 1000 b.i.d | a.m., p.m. | Ranit b.i.d. | 14 | 57 | 45.7 | 36.9 | 114 |

| 2012 | China | BSC 220 b.i.d. | 100 b.i.d. | 1000 b.i.d. | a.m., p.m. | E 20 b.i.d. | 10 | 43 | 72.5 | 64.1 | 64 |

| 2015 | Italy | BSC 240 b.i.d | 100 b.i.d. | 1000 b.i.d. | a.m., p.m. | E 20 b.i.d. | 10 | 52 | 90.1 | 88.5 | 63 |

| 2015 | Italy | BSC 240 b.i.d | 200 b.i.d. | 1000 b.i.d. | a.m., p.m. | E 20 b.i.d. | 10 | 51 | 94 | 92.1 | 63 |

Doses are in mg

BSC= Bismuth Subcitrate, Doxycyc = doxycycline, Amox = amoxicillin

P = pantoprazole, R = rabeprazole, L = lansoprazole, O = omeprazole, Ranit = ranitidine bismuth citrate

Examination of outcome in region where bismuth quadruple therapy frequently fails (e.g., Turkey and Iran)

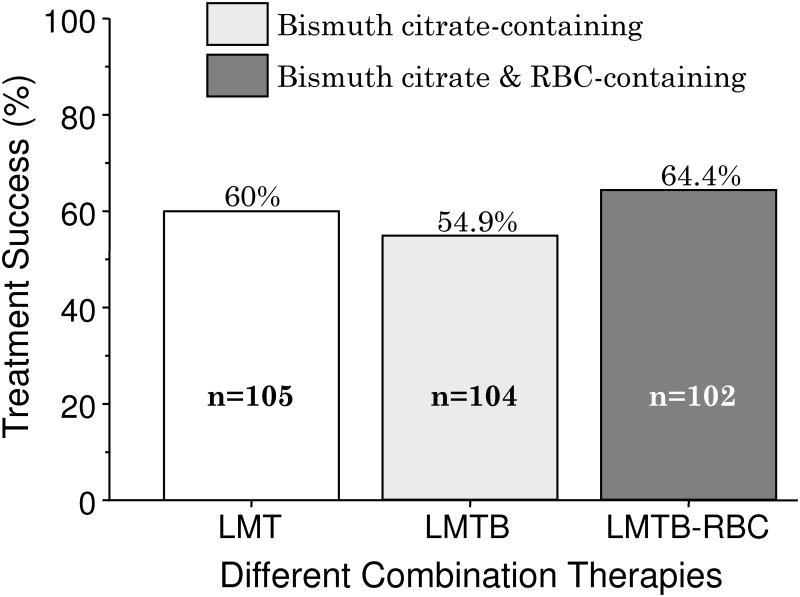

In the west, China, and Korea the results with bismuth triple therapy generally follow expectations and poor results can be understood when one takes into account the doses used, the duration of therapy and patient adherence. However, even when these factors are taken into account, the results with bismuth quadruple therapy have often been unsatisfactory in Turkey and Iran 65-74 (Table 4). Data from Turkey is especially interesting as there have been a number of studies that used full doses, 14 day duration and yet the results have been poor (Table 4). The recent study by Songur et al. is particularly interesting 68. The treated approximately 100 subjects with bismuth quadruple therapy. The study was randomized and used standard dose PPI, full dose tetracycline but on 1 gram of metronidazole (500 mg b.i.d.) and for only 10 days despite this being a high metronidazole resistance area. They reported acceptable compliance but achieved a cure rate of only 54.9% PP 68. Importantly, another group was randomized to receive PPI and antibiotics but no bismuth and achieved essentially the same result (60%) as when the regimen included bismuth (Table 4 and Figure 7) 68. Bismuth provided no additional benefit to antibiotics and PPI suggested the bismuth preparation utilized might have been biologically inactive. Fortunately they also randomized a group to receive traditional PPI-BMT plus a second bismuth preparation, ranitidine bismuth citrate 400 mg b.i.d. (i.e., the 5 drug regimen PPI-BMT-RBC) again with no significant additional benefit (i.e., 64% cured) (Figure 7) 68. Unfortunately, no susceptibility testing was done to assess metronidazole resistance, tetracycline resistance, and combined metronidazole and tetracycline resistance). The drugs were: the bismuth was DE-NOL, obtained from Genesis/Zentiva, the tetracycline HCL was in 500mg capsules from Mustafa Nevzat, and the metronidazole was tablets from Eczacibasi (information courtesy of Prof. Yildiran Songur).

Table 4. Summary of bismuth and metronidazole containing quadruple therapies in Turkey and Iran.

| Year | Location | Bismuth* | Tetracyc | Metro | PPI** | Days | # | PP | ITT | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | Turkey | BSC 300 q.i.d. | 500 q.i.d. | 500 q.i.d. | O 20 b.i.d. | 14 | 32 | 63.5 | 63.5 | 65 |

| 2004 | Turkey | RBC 400 b.i.d. | 1000 b.i.d. | 500 t.i.d. | none | 14 | 27 | 44.4 | 44.4 | 66 |

| 2007 | Turkey | BSS 200 q.i.d. | 500 q.i.d. | 500 t.i.d. | L 30 b.i.d. | 14 | 120 | 82.3 | 70 | 67 |

| 2009 | Turkey | BSC 300 q.i.d. | 500 q.i.d. | 500 b.i.d. | L 30 b.i.d. | 10 | 104 | 54.9 | 47.1 | 68 |

| 2010 | Turkey | BSC 400 b.i.d. | 500 q.i.d. | 500 t.i.d. | P 40 b.i.d. | 14 | 92 | 86.5 | 83.6 | 69 |

| 2011 | Turkey | BSS 200 q.i.d. | 500 q.i.d. | 500 t.i.d. | L 30 b.i.d. | 14 | 100 | 82.3 | 70 | 70 |

| 2013 | Turkey | BSC 300 q.i.d. | 500 q.i.d. | 500 t.i.d. | L 30 b.i.d. | 14 | 25 | 92 | 92 | 71 |

| 2014 | Turkey | BSC 120 q.i.d. | 500 q.i.d. | 500 t.i.d. | R 20 b.i.d. | 14 | 40 | 76.5 | 77.5 | 72 |

| 2014 | Iran | BSC 240 q.i.d | 500 q.i.d. | 500 q.i.d. | O 20 b.i.d. | 14 | 18 | 89 | 89 | 73 |

| 2014 | Iran | BSC ?mg b.i.d. | 500 q.i.d. | 250 q.i.d. | O 20 b.i.d. | 14 | 55 | 72 | ? | 74 |

Doses are in mg

BSC= Bismuth Subcitrate, BSS = bismuth subsalicylate, RBC = ranitidine bismuth citrate, Tetracyc = tetracycline, Metro = metronidazole, P = pantoprazole, R = rabeprazole, L = lansoprazole, O = omeprazole

Figure 7. Results of randomized 14-day trial in Turkey showing poor results irrespective of the addition of bismuth.

Therapy consisted of 10-day regimens consisting of lansoprazole 30 mg b.i.d. metronidazole 500 mg b.i.d., tetracycline 500 mg q.i.d. (LMT) with more traditional bismuth quadruple therapy (LMTB) and that regimen with the addition of ranitidine bismuth subcitrate 400 mg b.i.d. (LMTB-RBC).

Data from Songur Y, Senol A, Balkarli A, et al. Triple or quadruple tetracycline-based therapies versus standard triple treatment for Helicobacter pylori treatment. Am J Med Sci 2009;338:50-53.

There are few publications regarding antimicrobial susceptibility to metronidazole and tetracycline available from Turkey 75. However, a good number are available from Iran 76-87. In both countries metronidazole resistance is high and widespread. In contrast to most other regions, tetracycline resistance is relatively common (e.g., ∼10%). While, there are essentially no data regarding the effects of tetracycline resistance on bismuth quadruple therapy, we suspect it might be a critical variable. The general rule of antimicrobial therapy is that when the same drugs are used, the results are similar everywhere such that knowledge from one region is transferable to any other regions. The general lack of pretreatment susceptibility testing worldwide has been the major factor preventing tailoring therapy based on the local or regional patten of antimicrobial susceptibility. Unexplained and unexplainable treatment failures or successes add data but not useful knowledge. Studies of antimicrobial therapy for H. pylori, especially comparative studies that do not include the information needed to explain the results are likely not ethical as no generalizable conclusions are possible.

Bismuth, tetracycline, amoxicillin, PPI quadruple therapy

Amoxicillin was found not be inferior to metronidazole in bismuth triple therapy 32;88. Its role in quadruple therapy has not been extensively studied 89-91 (Table 5). As noted previously, in China the combination of bismuth subcitrate b.i.d., tetracycline 500 mg q.i.d., and high dose amoxicillin (1,000 mg t.i.d.) for 14 days cured 94.6% of 93 subjects per protocol 36. Additional studies of 14 day therapy are needed before a reliable estimation of its value can be rendered.

Table 5. Summary of bismuth, tetracycline, and amoxicillin containing quadruple therapies.

| Year | Location | Bismuth* | Tetracy | Amox | PPI** | Days | # | PP | ITT | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2003 | Taiwan | BSC 120 t.i.d. | 500 q.i.d. | 1000 b.i.d. | O 20 b.i.d. | 7 | 50 | 88.6 | 78 | 89 |

| 2009 | Turkey | RBC 400 b.i.d | 500 q.i.d. | 1000 b.i.d | Ranit b.i.d. | 14 | 58 | 40.5 | 34.5 | 114 |

| 2011 | Taiwan | BSC 120 q.i.d. | 500 q.i.d. | 500 q.i.d. | E 40 b.i.d. | 7 | 58 | 64 | 62 | 115 |

| 2006 | Korea | BSC 300 q.i.d. | 500 q.i.d. | 1000 b.i.d*. | P 40 b.i.d. | 7 | 29 | 17.4 | 16 | 90 |

| 2011 | Turkey | BSS 300 q.i.d. | 500 q.i.d. | 1000 b.id. | E 40 b.i.d. | 14 | 100 | 89.7 | 79 | 91 |

Doses are in mg

BSC= Bismuth Subcitrate,

amoxicillin-claulanate, Ranit - Ranitidine bismuth citrate, Tetracy = tetracycline, Amox = amoxicillin

O = omeprazole, E = esomeprazole, P = pantoprazole

Bismuth sequential therapies

Sequentially administered drugs were attempted in some early regimes (e.g., Logan et al. in 1994 92), however the first true sequential therapy was a bismuth-containing regimen used to treat patient who had failed therapy with then standard bismuth, metronidazole, tetracycline triple therapy (n=31) or dual PPI plus amoxicillin therapy (n =88) 93. The study was done in Greece which has a high background rate of metronidazole resistance and was typically an outlier in terms of cure rates from BMT triple therapy 32. The regimen consisted of 60 mg of omeprazole and 2 grams of amoxicillin days 1 through 10, followed by metronidazole 1.5 grams and bismuth citrate 120 mg q.i.d. for 10 days with the bismuth being continued for 6 weeks (i.e., until day 52). The cure rate per protocol was 95% (113/119). Seven subjects were lost to follow-up and 5 withdrew because of side effects (4%) and thus ITT analysis yielded 85%. More recently, Uygun et al. 94 proposed a different bismuth sequential regimen consisting of pantoprazole 40 mg and bismuth subcitrate 300 mg b.i.d. both for 14 days, amoxicillin 1 gram b.i.d. for the first 7 days, and tetracycline 500 mg q.i.d. and metronidazole 500 mg t.i.d., both for the last 7 days. One hundred forty-two subjects entered and the per protocol cure rate was 92% (ITT 81%, largely due to loss of follow-up). A prior study by the same group of 14 day PPI, bismuth, amoxicillin, tetracycline concomitant regimen from Turkey with 100 subjects achieved a per protocol cure rate of 89.7% 91.

Information needed to obtain generalizable results

As a general rule, data needed to explain poor results should be collected and published. When unexpected poor results occur one should provide results in relation to antimicrobial susceptibility/resistance. In this era of generic drugs, one should also provide details about the manufacture of the drugs used because fake and inferior drugs are now wildly available especially in developing countries. In the past when faced with unexpectedly poor results, we have confirmed the potency of the antibiotics used before publishing the results. We propose a check list for planning and reporting bismuth quadruple studies to ensure that the results will be interpretable and generalizable (Box 2). Table 6 shows the results of use of a check list to study why there was considerable variability in results from Korea 30;95-104.

Box 2. Check list for bismuth quadruple treatment trials.

Pretreatment susceptibility results for metronidazole and tetracycline

Confirmation of Etest determined metronidazole resistance by agar dilution

Treatment failures in relation to the number of days of full doses of medicine taken

Effect of the minimal inhibitory concentration of metronidazole on treatment failure

Effect of the minimal inhibitory concentration of tetracycline on treatment failure

Names and location of manufacturer of each component of the treatment regimen

Dosing for each drug in relation to meals and time of day

Treatment results in relation of resistance for each antibiotic and combination of antibiotics

- Results should include a number of different subgroups including:

- Intention to treat (all who received at least one dose)

- Modified intention to treat (all those with a determination of outcome)

- Per protocol (all those who completed the study)

- Per protocol per adherence (results for those taking drugs for different number of days such as <7, >7 but <10, 10, >10 but <14, and 14 days).

Table 6. Use of a check list to identify possible reasons for lower than expected results in some clinical trials in Korea.

| Factors that affect the eradication rate | Possibility on affecting the results in Koreans | |

|---|---|---|

| Regimen | Drugs used (manufacturer) | Low (To be considered as less important factor because there are not that much manufacturers. Most of the Korean studies used similar quadruple drugs provided by the same company.) |

| Dose, frequency (interval), formulation (tablet, capsule), duration | Low - dose, interval, formulation High – duration (Korean papers with 14 days showed better eradication rates than those with 7 days, although few studies showed similar eradication rates.) |

|

| Relation to meals | Low (Most of the studies recommended after the meals) | |

| PPI, mucolytics, probiotics | High - PPI (type of PPI differs a lot between the studies) Uncertain - other medications (insufficient data in Korea) |

|

| Study | Diagnosis methods used before and after eradication | High (due to the risk of false UBT results) |

| Antimicrobial resistance | High (resistance rates differ between the provinces) | |

| Odds of reinfection | Low (most of the reinfections might be recrudenscences) | |

| Patient | Compliance with instructions | High (although most of the pts followed the instructions, approximately 10-20% skipped due to busy schedule or side effects of the drug) |

| Side effects of medications | High | |

| Genetic polymorphisms that affect drug metabolism | Low (most of the Korean genetic studies show that there is not that much differences among Koreans) |

Issues ripe for systematic study

Relation of drug administration and meals

The relation between treatment outcome and drug administration in relation to meals remains largely unstudied. This issue encompasses the proportion of the benefit derived from the topical action of the drugs vs. the systemic antimicrobial activity. It has been proposed that administration with meals will enhance retention within the stomach and distribution of the drugs over the surface of the stomach. These potential benefits come with dilution of the drug concentration by the food and liquids ingested as well as potential binding of the drugs to food components or drug components (e.g., bismuth and tetracycline). Pharmacists will often “warn” patients to separate the ingestion of tetracycline from food or milk. Those of us who advocate taking the drugs with meals must also caution patients to ignore that warning. While the use of intravenously administered drugs has not been studied systematically, at a minimum it has not shown any advantage and 1 hour topical therapy in which the duodenum was blocked with a balloon proved effective in most patients 105. Often the relation of drug administration and meals is not reported. However, success and failures have been reported with many different combinations of before, during, and after meals but not in relation to the presence of metronidazole susceptibility. Similarly, the effective of formulation has achieved little attention. With amoxicillin-PPI dual therapy there appeared to be no advantage to administration capsules before meals, however, there appeared to be an advantage of using a liquid formulation of amoxicillin 106;107. This observation has not been followed up or systematically examined for other regimens. Nonetheless, drug administration should be specified and the issue is worthy of further study.

Reduction of side-effects with bismuth quadruple therapy

Possibilities include administration in relation to meals, dose reduction of the more noxious components (tetracycline and metronidazole) directly or by altering the frequency of administration. As noted above, there are data that twice-a-day dosing may provide a high cure rate with fewer side effects and accomplishes a reduction in total antibiotic dose. An advance would need to be proven in the presence of metronidazole resistance and could be most efficiently be examined in randomized trials in patients with proven metronidazole resistance as confirmed by agar dilution susceptibility tests. Ideally, the subjects should be treatment naïve as it is as yet unclear whether metronidazole resistance arising from recent treatment failure with a metronidazole-containing regimen is identical in outcome to treatment naïve subjects. At least, the analysis should also look at the two groups separately and in addition in relation to the minimal inhibitory concentration (e.g., <256 or >256 μg/mL).

Studies that are needed are morning and evening vs. noon and evening twice-a-day therapy, the best twice a day regimen vs. q.i.d., and depending on the results, possibly t.i.d. vs. q.i.d. therapy. For q.i.d. therapy it appears likely that one can reduce the dosage of tetracycline to approximately 1 gram without loss of effectiveness whereas at least 1.5 grams of metronidazole appears best. Since twice-a-day therapy has only 1 gram of metronidazole and 1 gram of tetracycline, it would seem that lower dose metronidazole should suffice but the current data suggest otherwise. Only randomized studies in metronidazole resistant infection can address the question. Studies from China and elsewhere have clearly confirmed that twice a day bismuth therapy is sufficient 108.

PPI dosage

With PPI, amoxicillin, clarithromycin triple therapy, higher dose PPI therapy (e.g., double dose) typically improves outcome. The effectiveness of both amoxicillin and clarithromycin are greater at higher pH. If the pH is consistently above 6, the clarithromycin is often no longer needed. However, tetracycline and metronidazole are relatively pH insensitive antimicrobials. The interaction of bismuth salts with acid leads to the formation of bismuth oxychloride which some believe is the antimicrobially active form. The fact that PPI adjuvant therapy helps overcome metronidazole suggests that higher doses may be better. Systematic studies are needed.

Efficient study design

Efficient study design implies that the variables are controlled as much as possible and that stopping rules are in place to limit exposure when it becomes clear that a regimen cannot succeed 109. The use of stopping rules allows most efficient use of resources and has been used successfully with bismuth quadruple therapy 63.

Recommendations

All therapy should be guided by the regional, local, and patient-specific antimicrobial resistance patterns and knowledge about the effective of anti-H. pylori regimens available locally. Patient-specific information is obtained from knowledge of about resistance patterns and the patient's history of antimicrobial use and/or by testing directly (e.g., by culture) or indirectly (by molecular testing of stool or biopsy samples) for resistance. Bismuth quadruple therapy is an excellent alternate first-line regimen in regions where it has proven to be effective. However, generally 14 day therapy with a PPI, amoxicillin, and clarithromycin or metronidazole or concomitant therapy with all 4 drugs is better tolerated. The primary indications for bismuth quadruple therapy are intolerance to amoxicillin (e.g., allergy) and prior failure with a PPI-amoxicillin-containing triple therapy 38;39.

If the infection is susceptible to metronidazole a 10 day course is satisfactory, however, in low metronidazole resistant areas triple therapy with a PPI, amoxicillin, and metronidazole for 14 days is effective and generally better tolerated. The main role of bismuth quadruple therapy is for those intolerant to penicillin derivatives or the presence of modest to high levels of metronidazole and clarithromycin resistance. In the presence of metronidazole resistance doses and duration are critical for good treatment success. Recommended therapy is a double dose PPI (40 mg of omeprazole or equivalent) at least 1,500 mg of metronidazole, 1,500 to 2,000 mg of tetracycline q.i.d., and a bismuth salt at least twice-a-day for 14 days. Unless proven effective in the local population doxycycline is not recommended as a substitute for tetracycline hydrochloride.

The decision to treat an H. pylori infection carries with it an obligation to provide specific patient education and counseling regarding the goals of therapy, the side effects possibly anticipated (e.g., abdominal pain, nausea, black stools with bismuth) and the necessity to complete the full 14 days. Bismuth quadruple therapy still remains to be optimized but this must be done in relation to metronidazole and for some regions, tetracycline resistance.

In most of the world resistance to amoxicillin and/or tetracycline is rare and, in contrast to metronidazole, clarithromycin, and fluoroquinolones, resistance to amoxicillin and/or tetracycline rarely develops after failed therapy. As such, treatment failure does not preclude using either or both again after treatment failure with bismuth quadruple therapy 98

Key Points.

Bismuth quadruple therapy consisting of a proton pump inhibitor, bismuth, metronidazole and tetracycline, is a good alternative first-line therapy especially useful when penicillin cannot be used or when clarithromycin and metronidazole resistance is common.

The literature is confusing because bismuth quadruple therapy is used to denote regimens that differ greatly in terms of duration, doses, and administration in relation to meals.

Proton pump inhibitor can help negate the deleterious effects of metronidazole resistance in bismuth quadruple therapy. The optimum dose of proton pump inhibitor is unclear. Double dose twice a day is recommended.

In the presence of metronidazole resistance, the optimum duration is 14 days along with 1500 to 1600 mg of metronidazole in divided dosages. The optimum doses and dosing intervals for tetracycline and bismuth are as yet unclear.

Poor patient adherence is a major issue with bismuth quadruple therapy. Patient education and counseling regarding the goals of therapy, the side effects and the necessity to complete the full 14 days should be provided.

As will all therapies, the decision to use bismuth quadruple therapy should be guided by the regional, local, and patient-specific antimicrobial resistance patterns and knowledge about effectiveness locally.

Twice-a-day dosing may provide a high cure rate with fewer side effects, accomplishes a reduction in total antibiotic dose, and improve adherence. However, its effectiveness in relation to metronidazole resistance remains unclear.

Acknowledgments

Supportive foundations: Dr. Graham is supported in part by the Office of Research and Development Medical Research Service Department of Veterans Affairs, Public Health Service grants DK067366 and DK56338 which funds the Texas Medical Center Digestive Diseases Center. The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the VA or NIH.

Footnotes

Author contributions: Each of the authors have been involved equally and have read and approved the final manuscript. Each meets the criteria for authorship established by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors and verify the validity of the results reported.

Potential conflicts: Dr. Graham is a unpaid consultant for Novartis in relation to vaccine development for treatment or prevention of H. pylori infection. Dr. Graham is a also a paid consultant for RedHill Biopharma regarding novel H. pylori therapies, for Otsuka Pharmaceuticals regarding diagnostic testing, and for BioGaia regarding use of probiotics for H. pylori infections. Dr. Graham has received royalties from Baylor College of Medicine patents covering materials related to 13C-urea breath test. Dr. Lee has nothing to declare.

References

- 1.Eberle J. A treatise of the Materia Medica and Therapeutics. 4th. Philadelphia: Crigg & Elliot; 1834. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brinton W. Ulcer of the stomach successfully treated. Assoc Med J. 1855:1125–1126. doi: 10.1136/bmj.s3-3.155.1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salvador JA, Figueiredo SA, Pinto RM, Silvestre SM. Bismuth compounds in medicinal chemistry. Future Med Chem. 2012;4:1495–1523. doi: 10.4155/fmc.12.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DuPont HL. Bismuth subsalicylate in the treatment and prevention of diarrheal disease. Drug Intell Clin Pharm. 1987;21:687–693. doi: 10.1177/106002808702100901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Graham DY, Estes MK, Gentry LO. Double-blind comparison of bismuth subsalicylate and placebo in the prevention and treatment of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli-induced diarrhea in volunteers. Gastroenterology. 1983;85:1017–1022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Graham DY, Klein PD, Opekun AR, et al. In vivo susceptibility of Campylobacter pylori. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989;84:233–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Graham DY, Evans DG. Prevention of diarrhea caused by enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli: lessons learned with volunteers. Rev Infect Dis. 1990;12(Suppl 1):S68–S72. doi: 10.1093/clinids/12.supplement_1.s68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hall DW. Review of the modes of action of colloidal bismuth subcitrate. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1989;157:3–6. doi: 10.3109/00365528909091043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koo J, Ho J, Lam SK, Wong J, Ong GB. Selective coating of gastric ulcer by tripotassium dicitrato bismuthate in the rat. Gastroenterology. 1982;82:864–870. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sandha GS, LeBlanc R, van Zanten SJ, et al. Chemical structure of bismuth compounds determines their gastric ulcer healing efficacy and anti-Helicobacter pylori activity. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:2727–2732. doi: 10.1023/a:1026667714603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wieriks J, Hespe W, Jaitly KD, Koekkoek PH, Lavy U. Pharmacological properties of colloidal bismuth subcitrate (CBS, DE-NOL) Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1982;80:11–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borsch GM, Graham DY. Helicobacter pylori. In: Collen MJ, Benjamin SB, editors. Pharmacology of Peptic Ulcer Disease, In: Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. Vol. 99. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1991. pp. 107–148. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lambert JR. Pharmacology of bismuth-containing compounds. Rev Infect Dis. 1991;13(Suppl 8):S691–S695. doi: 10.1093/clinids/13.supplement_8.s691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coghlan JG, Gilligan D, Humphries H, et al. Campylobacter pylori and recurrence of duodenal ulcers--a 12- month follow-up study. Lancet. 1987;2:1109–1111. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)91545-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martin DF, Hollanders D, May SJ, Ravenscroft MM, Tweedle DE, Miller JP. Difference in relapse rates of duodenal ulcer after healing with cimetidine or tripotassium dicitrato bismuthate. Lancet. 1981;1:7–10. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(81)90114-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vantrappen G, Schuurmans P, Rutgeerts P, Janssens J. A comparative study of colloidal bismuth subcitrate and cimetidine on the healing and recurrence of duodenal ulcer. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1982;80:23–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller JP, Hollanders D, Ravenscroft MM, Tweedle DE, Martin DF. Likelihood of relapse of duodenal ulcer after initial treatment with cimetidine or colloidal bismuth subcitrate. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1982;80:39–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kang JY, Piper DW. Cimetidine and colloidal bismuth in treatment of chronic duodenal ulcer. Comparison of initial healing and recurrence after healing. Digestion. 1982;23:73–79. doi: 10.1159/000198690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shreeve DR, Klass HJ, Jones PE. Comparison of cimetidine and tripotassium dicitrato bismuthate in healing and relapse of duodenal ulcers. Digestion. 1983;28:96–101. doi: 10.1159/000198970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bianchi PG, Lazzaroni M, Petrillo M, De NC. Relapse rates in duodenal ulcer patients formerly treated with bismuth subcitrate or maintained with cimetidine. Lancet. 1984;2:698. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)91258-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hamilton I, O'Connor HJ, Wood NC, Bradbury I, Axon AT. Healing and recurrence of duodenal ulcer after treatment with tripotassium dicitrato bismuthate (TDB) tablets or cimetidine. Gut. 1986;27:106–110. doi: 10.1136/gut.27.1.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bianchi PB, Lazzaroni M, Parente F, Petrillo M. The influence of colloidal bismuth subcitrate on duodenal ulcer relapse. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1986;122:35–38. doi: 10.3109/00365528609102584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Graham DY, Lew GM, Klein PD, et al. Effect of treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection on the long- term recurrence of gastric or duodenal ulcer. A randomized, controlled study. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116:705–708. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-116-9-705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Borody TJ, Cole P, Noonan S, et al. Recurrence of duodenal ulcer and Campylobacter pylori infection after eradication. Med J Aust. 1989;151:431–435. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1989.tb101251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.George LL, Borody TJ, Andrews P, et al. Cure of duodenal ulcer after eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Med J Aust. 1990;153:145–149. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1990.tb136833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Borody TJ, Andrews P, Fracchia G, Brandl S, Shortis NP, Bae H. Omeprazole enhances efficacy of triple therapy in eradicating Helicobacter pylori. Gut. 1995;37:477–481. doi: 10.1136/gut.37.4.477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Boer W, Driessen W, Jansz A, Tytgat G. Effect of acid suppression on efficacy of treatment for Helicobacter pylori infection. Lancet. 1995;345:817–820. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)92962-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Al-Assi MT, Genta RM, Graham DY. Short report: omeprazole-tetracycline combinations are inadequate as therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1994;8:259–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1994.tb00285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Graham DY, Osato MS, Hoffman J, et al. Metronidazole containing quadruple therapy for infection with metronidazole resistant Helicobacter pylori: a prospective study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:745–750. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2000.00770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee BH, Kim N, Hwang TJ, et al. Bismuth-containing quadruple therapy as second-line treatment for Helicobacter pylori infection: effect of treatment duration and antibiotic resistance on the eradication rate in Korea. Helicobacter. 2010;15:38–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2009.00735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.*Fischbach LA, Goodman KJ, Feldman M, Aragaki C. Sources of variation of Helicobacter pylori treatment success in adults worldwide: a meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31:128–139. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.1.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.*Fischbach LA, van ZS, Dickason J. Meta-analysis: the efficacy, adverse events, and adherence related to first-line anti-Helicobacter pylori quadruple therapies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:1071–1082. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.*van der Wouden EJ, Thijs JC, van Zwet AA, Sluiter WJ, Kleibeuker JH. The influence of in vitro nitroimidazole resistance on the efficacy of nitroimidazole-containing anti-Helicobacter pylori regimens: a meta- analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1751–1759. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bardhan K, Bayerdorffer E, Veldhuyzen van Zanten SJ, et al. The HOMER sudy: the effect of increasing the dose of metronidazole when given with omeprazole and amoxicillin to cure Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 2000;5:196–201. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5378.2000.00030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miehlke S, Kirsch C, Schneider-Brachert W, et al. A prospective, randomized study of quadruple therapy and high-dose dual therapy for treatment of Helicobacter pylori resistant to both metronidazole and clarithromycin. Helicobacter. 2003;8:310–319. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5378.2003.00158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liang X, Xu X, Zheng Q, et al. Efficacy of bismuth-containing quadruple therapies for clarithromycin-, metronidazole-, and fluoroquinolone-resistant Helicobacter pylori infections in a prospective study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:802–807. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.*Fischbach L, Evans EL. Meta-analysis: the effect of antibiotic resistance status on the efficacy of triple and quadruple first-line therapies for Helicobacter pylori. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:343–357. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Graham DY, Lee YC, Wu MS. Rational Helicobacter pylori therapy: Evidence-based medicine rather than medicine-based evidence. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:177–186. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu JY, Liou JM, Graham DY. Evidence-based recommendations for successful Helicobacter pylori treatment. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;8:21–28. doi: 10.1586/17474124.2014.859522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Graham DY, Belson G, Abudayyeh S, Osato MS, Dore MP, El-Zimaity HM. Twice daily (mid-day and evening) quadruple therapy for H. pylori infection in the United States. Dig Liver Dis. 2004;36:384–387. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2004.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Osato MS, Reddy R, Reddy SG, Penland RL, Graham DY. Comparison of the Etest and the NCCLS-approved agar dilution method to detect metronidazole and clarithromycin resistant Helicobacter pylori. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2001;17:39–44. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(00)00320-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Malfertheiner P, Bazzoli F, Delchier JC, et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication with a capsule containing bismuth subcitrate potassium, metronidazole, and tetracycline given with omeprazole versus clarithromycin-based triple therapy: a randomised, open-label, non-inferiority, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2011;377:905–913. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Salazar CO, Cardenas VM, Reddy RK, Dominguez DC, Snyder LK, Graham DY. Greater than 95% success with 14-day bismuth quadruple anti-Helicobacter pylori therapy: A pilot study in US Hispanics. Helicobacter. 2012;17:382–389. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2012.00962.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Borody TJ, Brandl S, Andrews P, Ferch N, Jankiewicz E, Hyland L. Use of high efficacy, lower dose triple therapy to reduce side effects of eradicating Helicobacter pylori. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:33–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.de Boer WA. How to achieve a near 100% cure rate for H. pylori infection in peptic ulcer patients. A personal viewpoint. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1996;22:313–316. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199606000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Al-Eidan FA, McElnay JC, Scott MG, McConnell JB. Management of Helicobacter pylori eradication--the influence of structured counselling and follow-up. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;53:163–171. doi: 10.1046/j.0306-5251.2001.01531.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.*Ford AC, Malfertheiner P, Giguere M, Santana J, Khan M, Moayyedi P. Adverse events with bismuth salts for Helicobacter pylori eradication: systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:7361–7370. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.7361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.*Gene E, Calvet X, Azagra R, Gisbert JP. Triple vs. quadruple therapy for treating Helicobacter pylori infection: a meta-analysis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:1137–1143. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hojo M, Miwa H, Nagahara A, Sato N. Pooled analysis on the efficacy of the second-line treatment regimens for Helicobacter pylori infection. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:690–700. doi: 10.1080/003655201300191941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Delchier JC, Malfertheiner P, Thieroff-Ekerdt R. Use of a combination formulation of bismuth, metronidazole and tetracycline with omeprazole as a rescue therapy for eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40:171–177. doi: 10.1111/apt.12808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Graham DY, Dore MP. Variability in the outcome of treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection: a critical analysis. In: Hunt RH, Tytgat GNJ, editors. Helicobacter pylori Basic mechanisms to clinical cure 1998. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1998. pp. 426–440. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dore MP, Graham DY, Mele R, et al. Colloidal bismuth subcitrate-based twice-a-day quadruple therapy as primary or salvage therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:857–860. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dore MP, Marras L, Maragkoudakis E, et al. Salvage therapy after two or more prior Helicobacter pylori treatment failures: the super salvage regimen. Helicobacter. 2003;8:307–309. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5378.2003.00150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dore MP, Farina V, Cuccu M, Mameli L, Massarelli G, Graham DY. Twice-a-day bismuth-containing quadruple therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication: a randomized trial of 10 and 14 days. Helicobacter. 2011;16:295–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2011.00857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dore MP, Maragkoudakis E, Pironti A, et al. Twice-a-day quadruple therapy for eradication of Helicobacter pylori in the elderly. Helicobacter. 2006;11:52–55. doi: 10.1111/j.0083-8703.2006.00370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Graham DY, Hoffman J, El-Zimaity HM, Graham DP, Osato M. Twice a day quadruple therapy (bismuth subsalicylate, tetracycline, metronidazole plus lansoprazole) for treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11:935–938. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1997.00219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zheng Q, Dai J, Li X, Ziao S. Comparison of the efficacy of pantoprazole-based triple therapy versus quadruple therapy in the treatment of Helicobacter pylori infections: a single-center, randomized, open and parallel-controlled study. Chin J Gastroenterol. 2009;14:8–11. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zheng Q, Chen WJ, Lu H, Sun QJ, Xiao SD. Comparison of the efficacy of triple versus quadruple therapy on the eradication of Helicobacter pylori and antibiotic resistance. J Dig Dis. 2010;11:313–318. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2980.2010.00457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Garcia N, Calvet X, Gene E, Campo R, Brullet E. Limited usefulness of a seven-day twice-a-day quadruple therapy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;12:1315–1318. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200012120-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Borody TJ, George LL, Brandl S, et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication with doxycycline-metronidazole-bismuth subcitrate triple therapy. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1992;27:281–284. doi: 10.3109/00365529209000075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cammarota G, Martino A, Pirozzi G, et al. High efficacy of 1-week doxycycline- and amoxicillin-based quadruple regimen in a culture-guided, third-line treatment approach for Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:789–795. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.01910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang Z, Wu S. Doxycycline-based quadruple regimen versus routine quadruple regimen for rescue eradication of Helicobacter pylori: an open-label control study in Chinese patients. Singapore Med J. 2012;53:273–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ciccaglione A, Cellini L, Grossi L, Manzoli L, Marzio L. A triple and quadruple therapy with doxycycline and bismuth for first-line treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection: a pilot study. Helicobacter. 2015 doi: 10.1111/hel.12209. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kohanteb J, Bazargani A, Saberi-Firoozi M, Mobasser A. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing of Helicobacter pylori to selected agents by agar dilution method in Shiraz-Iran. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2007;25:374–377. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.37342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gumurdulu Y, Serin E, Ozer B, et al. Low eradication rate of Helicobacter pylori with triple 7-14 days and quadruple therapy in Turkey. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:668–671. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i5.668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Altintas E, Ulu O, Sezgin O, Aydin O, Camdeviren H. Comparison of ranitidine bismuth citrate, tetracycline and metronidazole with ranitidine bismuth citrate and azithromycin for the eradication of Helicobacter pylori in patients resistant to PPI based triple therapy. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2004;15:90–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Uygun A, Kadayifci A, Safali M, Ilgan S, Bagci S. The efficacy of bismuth containing quadruple therapy as a first-line treatment option for Helicobacter pylori. J Dig Dis. 2007;8:211–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2980.2007.00308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Songur Y, Senol A, Balkarli A, Basturk A, Cerci S. Triple or quadruple tetracycline-based therapies versus standard triple treatment for Helicobacter pylori treatment. Am J Med Sci. 2009;338:50–53. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e31819c7320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Demir M, Gokturk S, Ozturk NA, Serin E, Yilmaz U. Bismuth-based first-line therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Digestion. 2010;82:47–53. doi: 10.1159/000236024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Uygun A, Kadayifci A, Yesilova Z, Safali M, Ilgan S, Karaeren N. Comparison of sequential and standard triple-drug regimen for Helicobacter pylori eradication: a 14-day, open-label, randomized, prospective, parallel-arm study in adult patients with nonulcer dyspepsia. Clin Ther. 2008;30:528–534. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Onal IK, Gokcan H, Benzer E, Bilir G, Oztas E. What is the impact of Helicobacter pylori density on the success of eradication therapy: a clinico-histopathological study. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2013;37:642–646. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sapmaz F, Kalkan IH, Guliter S, Atasoy P. Comparison of Helicobacter pylori eradication rates of standard 14-day quadruple treatment and novel modified 10-day, 12-day and 14-day sequential treatments. Eur J Intern Med. 2014;25:224–229. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2013.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hosseini SM, Sharifipoor F, Nazemian F, Ghanei H, Zivarifar HR, Fakharian T. Helicobacter pylori eradication in renal recipient: triple or quadruple therapy? Acta Med Iran. 2014;52:271–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Talaie R. Efficacy of standard triple therapy versus bismuth-based quadruple therapy for eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection. J Paramedical Sciences. 2014;5:9–14. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Goral V, Zeyrek FY, Gul K. Antibiotic resistance in Helicobacter pylori infection. T Klin J Gastroenterohepatol. 2000;11:87–92. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Abadi AT, Taghvaei T, Mobarez AM, Carpenter BM, Merrell DS. Frequency of antibiotic resistance in Helicobacter pylori strains isolated from the northern population of Iran. J Microbiol. 2011;49:987–993. doi: 10.1007/s12275-011-1170-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fallahi GH, Maleknejad S. Helicobacter pylori culture and antimicrobial resistance in Iran. Indian J Pediatr. 2007;74:127–130. doi: 10.1007/s12098-007-0003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Farshad S, Alborzi A, Japoni A, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Helicobacter pylori strains isolated from patients in Shiraz, Southern Iran. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:5746–5751. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i45.5746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Khademi F, Faghri J, Poursina F, et al. Resistance pattern of Helicobacter pylori strains to clarithromycin, metronidazole, and amoxicillin in Isfahan, Iran. J Res Med Sci. 2013;18:1056–1060. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kohanteb J, Bazargani A, Saberi-Firoozi M, Mobasser A. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing of Helicobacter pylori to selected agents by agar dilution method in Shiraz-Iran. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2007;25:374–377. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.37342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Milani M, Ghotaslou R, Akhi MT, et al. The status of antimicrobial resistance of Helicobacter pylori in Eastern Azerbaijan, Iran: comparative study according to demographics. J Infect Chemother. 2012;18:848–852. doi: 10.1007/s10156-012-0425-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mohammadi M, Doroud D, Mohajerani N, Massarrat S. Helicobacter pylori antibiotic resistance in Iran. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:6009–6013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i38.6009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Shokrzadeh L, Jafari F, Dabiri H, et al. Antibiotic susceptibility profile of Helicobacter pylori isolated from the dyspepsia patients in Tehran, Iran. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:261–264. doi: 10.4103/1319-3767.82581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Siavoshi F, Safari F, Doratotaj D, Khatami GR, Fallahi GH, Mirnaseri MM. Antimicrobial resistance of Helicobacter pylori isolates from Iranian adults and children. Arch Iran Med. 2006;9:308–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Siavoshi F, Saniee P, Latifi-Navid S, Massarrat S, Sheykholeslami A. Increase in resistance rates of H. pylori isolates to metronidazole and tetracycline--comparison of three 3-year studies. Arch Iran Med. 2010;13:177–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Talebi Bezmin AA, Ghasemzadeh A, Taghvaei T, Mobarez AM. Primary resistance of Helicobacter pylori to levofloxacin and moxifloxacine in Iran. Intern Emerg Med. 2012;7:447–452. doi: 10.1007/s11739-011-0563-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zendedel A, Moradimoghadam F, Almasi V, Zivarifar H. Antibiotic resistance of Helicobacter pylori in Mashhad, Iran. J Pak Med Assoc. 2013;63:336–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.van der Hulst RW, Keller JJ, Rauws EA, Tytgat GN. Treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection: a review of the world literature. Helicobacter. 1996;1:6–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.1996.tb00003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chi CH, Lin CY, Sheu BS, Yang HB, Huang AH, Wu JJ. Quadruple therapy containing amoxicillin and tetracycline is an effective regimen to rescue failed triple therapy by overcoming the antimicrobial resistance of Helicobacter pylori. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:347–353. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Cheon JH, Kim SG, Kim JM, et al. Combinations containing amoxicillin-clavulanate and tetracycline are inappropriate for Helicobacter pylori eradication despite high in vitro susceptibility. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:1590–1595. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kadayifci A, Uygun A, Polat Z, et al. Comparison of bismuth-containing quadruple and concomitant therapies as a first-line treatment option for Helicobacter pylori. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2012;23:8–13. doi: 10.4318/tjg.2012.0392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Logan RP, Gummett PA, Misiewicz JJ, Karim QN, Walker MM, Baron JH. One week's anti-Helicobacter pylori treatment for duodenal ulcer. Gut. 1994;35:15–18. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Tzivras M, Balatsos V, Souyioultzis S, Tsirantonaki M, Skandalis N, Archimandritis A. High eradication rate of Helicobacter pylori using a four-drug regimen in patients previously treated unsuccessfully. Clin Ther. 1997;19:906–912. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(97)80044-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]