Abstract

Cervical cancer is the most frequent cancer among women aged between 15 years and 44 years in Kenya, resulting in an estimated 4,802 women being diagnosed with cervical cancer and 2,451 dying from the disease annually. It is often detected at its advanced invasive stages, resulting in a protracted illness upon diagnosis. This qualitative study looked at the illness trajectories of women living with cervical cancer enrolled for follow-up care at Kenyatta National Hospital cancer treatment center and the Nairobi Hospice, both in Nairobi county, Kenya. Using the qualitative phenomenological approach, data were collected through 18 in-depth interviews with women living with cervical cancer between April and July 2011. In-depth interviews with their caregivers, key informant interviews with health care workers, and participant observation field notes were used to provide additional qualitative data. These data were analyzed based on grounded theory’s inductive approach. Two key themes on which the data analysis was then anchored were identified, namely, psychosocial challenges of cervical cancer and structural barriers to quality health care. Findings indicated a prolonged illness trajectory with psychosocial challenges, fueled by structural barriers that women were faced with after a cervical cancer diagnosis. To address issues relevant to the increasing numbers of women with cervical cancer, research studies need to include larger samples of these women. Also important are studies that allow in-depth understanding of the experiences of women living with cervical cancer.

Keywords: qualitative, illness trajectories, women, cervical cancer

Introduction

Cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer among women worldwide with 528,000 new cases reported in 2012, 84% of which were from developing countries.1 In Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), about 60%–75% of women who develop cervical cancer live in rural areas, and mortality is very high. “Affecting relatively young women, cervical cancer is the largest single cause of years of life lost to cancer in the developing world.”2 Women in SSA lose more years to cervical cancer than to any other type of cancer, and it affects women at a time in their life when they are critical to the social and economic stability of their families.3

Kenya has a population of 12.92 million women aged 15 years and older who are at risk of developing cervical cancer. This is the most frequent cancer among women aged between 15 years and 44 years, resulting in an estimated 4,802 women being diagnosed with cervical cancer and 2,451 dying from the disease annually.4 Further, Kenya ranks at number 16 out of the 20 high-cervical cancer disease burden countries with an age-standardized ratio of 40.1 per 100,000 worldwide.1

According to the World Health Organization, health is not merely the absence of disease or infirmity but a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being.5 Health is more than just a means of living longer. The real purpose of health is to allow a more satisfying and meaningful life, to enjoy a higher quality of life (QOL). We can view QOL in terms of physical pain or depression. We can also look at how health determines whether we can work, maintain activities of daily life, and remain independent for as long as possible.6 Beyond diagnosis with cervical cancer, what is the illness trajectory, and how is it relating to the QOL of the patient?

Studies in Kenya have so far looked at awareness and prevention of cervical cancer and the knowledge and attitudes of women.7,8 Consequently, there have been scaled-up campaigns to create awareness and promote uptake of screening services toward prevention of cervical cancer. Despite availability of nationwide screening services for cervical cancer, women still present with late-stage invasive disease, and as such, the diagnosis is made at advanced stage of the disease, which carries a high morbidity and mortality rate.

Through qualitative approaches, we can better understand cultural and contextual factors of cervical cancer and other chronic illnesses survivorship.9 Fewer studies have however looked at cancer patients’ illness experiences without distinctly looking at cervical cancer patient illness trajectories; yet, they affect a significant number of women.4,10

This study explored illness trajectories of cervical cancer patients receiving care in Kenya.

Materials and methods

Study design

This qualitative study utilized the phenomenological approach to scientific inquiry as it sought to engage the respondents in sharing their cervical cancer illness trajectories. Phenomenology is the direct investigation and description of phenomena as consciously experienced, without theories about their causal explanations or their objective reality. It therefore seeks to understand how people construct meaning.9 Small samples are most suitable for this type of research. Large samples can become unwieldy.9 Qualitative methodological approaches for data collection, analysis, and presentation were utilized in exploring the illness trajectories of women living with cervical cancer.

Setting

The study was conducted among women on follow-up for care and treatment at Kenyatta National Hospital and the Nairobi Hospice both in Nairobi, Kenya. The cancer treatment center at Kenyatta National Hospital receives an estimated 2,500 new cancer cases including cervical cancer patients each year from all regions of Kenya. Given the advanced stage of diagnosis that requires radiotherapy and chemotherapy treatment, many of the patients are referred to Kenyatta National Hospital, which treats chronically ill patients from all over the country.11 Nairobi Hospice offers palliative care to patients assessed to be chronically ill and referred there from Kenyatta National Hospital and other health facilities.

Sampling

Purposive non-probability sampling was used to select the sample population of 18 cervical cancer patients. The staff-in-charge in the health facilities helped identify the cervical cancer patients under their care, who are medically stable to participate in the study. Eighteen women on follow-up for care for cervical cancer who were medically stable to engage in the study were identified by the nurse-in-charge at the Kenyatta National Hospital cancer treatment center, and at the Nairobi Hospice and handed over to the first author who collected the study data.

Approval from the Institute of Gender, Anthropology and African Studies (IAGAS), University of Nairobi was granted to conduct the study. Ethical clearance from the Ethics Review Committee (ERC), Kenyatta National Hospital / University of Nairobi and a research permit from the National Council of Science and Technology were sought prior to the study. The ethical considerations included ensuring maximum comfort of the respondents during the study, their voluntary engagement in the study, as well as no direct benefits to the respondents or their families for participating in the study. In addition, the researcher noted how important the information the respondents gave was in informing the study. The confidentiality of the respondents was maintained, and acknowledgments have been made to appreciate their resourcefulness in informing the study. Having informed the study respondents on the details of the study, the researcher requested their voluntary participation. The cervical cancer patients were also informed of the involvement of their families by way of interacting with their caregivers. Verbal and written consent was sought from each of the respondents. Once they agreed, the cervical cancer patients were then recruited as respondents for the study. Eighteen cervical cancer patients who were medically stable to give verbal and written consent were selected and engaged as respondents in in-depth interviews. From those who consented, permission to interview their caregivers during one of their subsequent clinic visits was also sought. Consent from the caregiver was later sought.

Data collection

Data on the illness trajectories of the women were collected between April and July 2011 by use of in-depth interviews at the respective health service provider centers where respondents were sampled from and enrolled into the study. Since the respondents had a 2-week return date to their respective facility (Kenyatta National Hospital or Nairobi Hospice), interviews were conducted during a subsequent hospital visit as was convenient to the respondents, first for the respondent and thereafter for the caregiver at a different visit. The caregiver in this study was an adult family member, preferably the spouse who took care of the cervical cancer patient. The key informant interviews and field notes of observation helped gather additional information on patients’ illness trajectories.

All the interviews were tape-recorded with the permission of the respondents, and field notes captured.

Data analysis

Data from the in-depth interviews were transcribed and translated verbatim into English as most of the interviews were conducted in Swahili. Names of respondents were replaced with pseudonyms on the transcripts for anonymity. Once transcribed, the transcripts were reviewed for accuracy and read through repeatedly to identify and list inductive codes. Data were analyzed based on grounded theory’s inductive approach where the data were used to inform theory.

A codebook was developed and used to code the transcripts manually. After coder agreement and transcripts review, guided by the study questions, key themes were identified, and the analysis was completed based on these two themes, namely psychosocial challenges of cervical cancer and structural barriers to quality health care. Additional information was included from the key informant interviews and field notes taken during the interviews.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics

The age range of the respondents was 35–80 years, with an average of 57.5 years. All of them were either married (12) or widows (six) with an average of five children each. The children were aged between 7 years and 51 years. Most (16 out of 18) of the respondents were involved in economic activities before the onset of their illness. Ten (55.6%) of the caregivers were female, while eight (44.4%) were male. The caregiver in this study is an adult family member who takes care of the cervical cancer patient including accompanying her for the clinic visits scheduled fortnightly at Kenyatta National Hospital and once a month at Nairobi Hospice as at the time of the study.

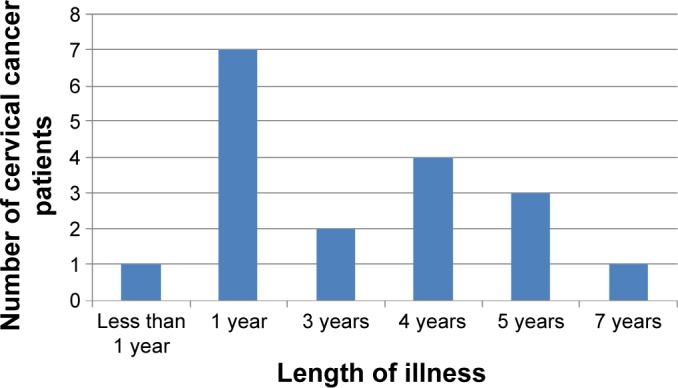

Length of illness

The respondents had lived with cervical cancer for periods ranging from 6 months to 7 years since diagnosis as illustrated in Figure 1. Only one of the respondents had been diagnosed in the last 6 months, while seven had known their diagnosis of cervical cancer for 1 year at the time data were collected. Two had lived with cervical cancer for 3 years since diagnosis, while four had been diagnosed 4 years back. Three others had been diagnosed 5 years back, while one had lived with cervical cancer for 7 years. Over the period of living with cervical cancer, the respondents and their families had faced psychosocial challenges such as below.

Figure 1.

Length of illness.

Anxiety and fear of death

Almost all the respondents mentioned anxiety and fear of death as the first and most recurrent challenge they faced. Since cancer has over time been associated with no cure, once diagnosed, the respondents reported having to battle with feelings and emotions that expressed anxiety and fear of death. The following excerpts illustrate this:

I have also lost so much weight. I fear that I will die soon. [Patient #18, 70 years, widow]

At first when I was told I had cancer, I did not believe it! Of all sicknesses, cervical cancer? I thought I was going to die. I was so worried. [Patient #16, 67 years, widow]

The families of the cervical cancer patients were also faced with the challenge of anxiety and fear as reported by the care-givers. Families have to come to terms with the chronic condition a family member is ailing with as illustrated below:

As I had told you earlier we were finding it very difficult to accept mother’s condition. This was our greatest challenge as a family. In as much as we will all die some day, when a terminal illness comes, the situation is worse. [Caregiver #14, 35 years, daughter]

When mother was diagnosed the whole family was in shock. Cancer of the cervix? You know the perception we have of cancer is that once you have it you die. [Caregiver #16, 45 years, daughter]

High cost of cervical cancer management

The respondents and their caregivers reported economic strain as a major challenge of living with cervical cancer. They noted that when the respondents fall sick, they usually stopped working. The shift in priorities to focus more on the treatment and management of cervical cancer may be temporary or permanent. The net effect of this withdrawal from work often affected the overall family income. This is illustrated by the following excerpt from one of the patients:

We are business people, me and my husband. We sell clothes in Busia. Now when I fell ill I stopped working […] now I am sick we need money for hospital. I left my husband and came to Nairobi where my other family members can look after me until I get better. [Patient #3, 35 years, married]

It is further reinforced by the following excerpt by one of the caregivers:

The greatest challenge is money. Especially in the beginning, you know my wife became sick and before then she was contributing to the family upkeep [the wife stopped working because of her sickness]…We initially sold everything to offset her medical bills. Although now she is recovering it [financial strain brought about by his wife’s cervical cancer condition] is still rubbed on our finances as a family. [Caregiver #1, 59 years, spouse]

Furthermore, resources have to be diverted toward the treatment and management of cervical cancer. They often require substantial resources to access treatment which includes antibiotics, pain relievers, radiotherapy and chemotherapy, as well as other items used in the management of cervical cancer, including diapers and sanitary towels as exemplified by this excerpt:

When the doctor confirmed that I had cervical cancer and recommended that I commence treatment, I did not have money so I went back home… They had to sell a few of our belongings and we came back [to hospital]… This [the treatment] was very expensive. It left us without anything. [Patient #1, 51 years, married]

Similarly, caregivers illustrated the high cost of treatment and management of cervical cancer as in the following excerpt:

They [doctors] then recommended that my mother start on chemotherapy and radiotherapy. When they quoted the price, it was too expensive and I could not raise that kind of money so we just went home… [Caregiver #11, 43 years, daughter]

Transport and accommodation were reported as an added expense to the treatment of cervical cancer, as the respondents and their caregivers mostly traveled from outside Nairobi. Fourteen out of the 18 respondents reside outside Nairobi where the referral hospital is located. The regular hospital visits for treatment and follow-up for which the respondents were accompanied by their caregivers required transport and accommodation arrangements. This was an extra expense on their already strained budgets. The following excerpts illustrate this:

Coming to hospital is a great challenge. We live in Kirinyaga, coming all the way and that I have to always come with someone, the fare sometimes is too much. [Patient #5, 52 years, married]

Being a referral hospital, KNH interacts with patients referred from all over the country. Some cervical cancer patients come from far and often are accompanied by their family members due to their health condition, the transport and accommodation costs become an added expense on their already constrained budgets. [Health care worker #1, Kenyatta National Hospital]

Strained family relationships post-diagnosis

The respondents and their caregivers reported that the illness led to strained family relationships post diagnosis. The strained relationship was reported to be between the patient and other family members. In one instance, a cervical cancer patient noted that her health condition had caused a strained relationship with her mother-in-law. The mother-in-law developed a negative attitude toward her ailing daughter-in-law, as illustrated below:

My mother-in-law is the one who has been on my case [has been constantly picking arguments with me] since I started ailing. Initially I was affected by her attitude such that I even developed High Blood Pressure… I never take to heart what she says. [Patient #11, 62 years, married]

The strained family relationships would also come about in a situation where the patients and their caregivers disagreed on the treatment and management of cervical cancer. The result is strife between the patient and caregiver as illustrated by the following excerpt by one of the caregivers:

My mother seems unhappy with the treatment I opted for her [the cervical cancer patient is the caregiver’s mother]… Kama ameandikiwa [If this is her destiny] – cervical cancer – then let it be but without complicating it. However this is my opinion. My mother does not like it at all. She even says that I have refused to pay for her treatment. She does not understand that the money is more than what I can afford. [Caregiver #18, 45 years, daughter]

This is further reinforced by the following excerpt from the patient herself, confirming what her daughter had said:

The doctor recommended that nichomwe [radiotherapy and chemotherapy]. My daughter said we did not have that kind of money and we went home…We came back to KNH, and they referred us to Nairobi hospice…But I am not happy with this [palliative care as the treatment option]. [Patient #18, 70 years, widow]

Body image and sexual health concerns

The respondents reported that their sense of womanhood had been greatly affected by cervical cancer. They went on to mention that the nature of treatment of cervical cancer sometimes required surgery which removed their uterus. They also noted that the intensity of radiotherapy and chemotherapy usually left the women in their reproductive age infertile and physically scarred, a factor that greatly affected their body image and sexuality. The following excerpts from a cervical cancer patient and a health care worker illustrate this:

Losing the ability to have children has been a hard thing to reconcile myself with…I know I have children already, but losing my uterus is like being stripped of one of the things that defines me as a woman. Because of this, I feel like I have lost a large part of my identity as a female. [Patient #6, 38 years, married]

In cases where the cervical cancer in a patient is diagnosed in the early stages, then surgery is usually the form of treatment given. In the case of surgery, at times the whole uterus is removed rendering the woman infertile. The patients often find the situation damaging and it takes a lot of follow up, counseling and re assurance for a patient to feel whole again after such a procedure. [Health care worker #3, Kenyatta National Hospital]

The respondents also said that the illness had impacted on their body image and hence their sexuality in terms of how the patients now related sexually with their spouses post-diagnosis and therapy for cervical cancer. Once on treatment, the respondents had to disengage from any sexual activities until assessed as fit by a health practitioner. The following excerpts by spouses of cervical cancer patients illustrate this:

I even at times fear that I will hurt her [his wife if they have sex]. It has taken me [spouse] several trips with her [cervical cancer patient] to the clinic so that I can ask the doctor again and again about cervical cancer and whether it is okay to engage in marital affairs [sexual activities]. [Caregiver #4, 44 years, spouse]

Our sex life had to come to a stop when my wife became sick. But you know after all these years of marriage, we need each other even without sex, and as you can see we are old and that is no longer a necessity… [Caregiver #10, 50 years, spouse]

In addition, the symptoms of cervical cancer, which included bleeding and pain during sexual intercourse, were reported as making intercourse less desirable. Since cervical cancer is a gynecological condition, sexual relations are further affected with spouses afraid of infection as illustrated by the following excerpts:

You know even after my wife was okay I could not bring myself to… [Have sex with her]… you know, because I was afraid of getting infected or something. [Caregiver #6, 42 years, spouse]

Cervical cancer? How did she get it? You know I wanted to know if it was sexually transmitted, may I also have gotten it… We talked a lot about her illness and we even went for a HIV test which came out negative…This affected our sexual relationship a lot. [Caregiver #12, 63 years, spouse]

Fear of stigma and avoidance

The respondents reported the fear of stigma and avoidance as a challenge in living with cervical cancer. They noted that since cervical cancer was a chronic illness that affected the reproductive health system, it made the condition sensitive. The respondents also noted that the symptoms it manifested including heavy bleeding and odorous discharge made it difficult for them to associate freely with people. This fear of being stigmatized made patients and their families keep cervical cancer a secret. Excerpts by two respondents illustrate this:

At first I kept quiet of my condition because I was ashamed. I had never seen anything like it. I was even at times having smelly discharge and blood with clots. When it became too much I had to act. So I gathered my children home and told them. This is when they decided to take me to hospital. [Patient #7, 70 years, widow]

The extended family only knows that my wife was sick and now she is well. We have kept the details of her illness to ourselves. We felt they [the extended family members] would not understand and we did not want any negative reactions regarding my wife’s illness. [Caregiver #10, 50 years, spouse]

This is further reinforced by the following excerpt by one of the caregivers:

You know back in the village I now know 3 elderly women who died of cucu’s [Grandmother’s] condition [cervical cancer]. They died in their silence. They were ashamed of their sickness [cervical cancer], because a lot of people in the rural areas do not understand the nature and cause of this illness… [Caregiver #7, 27 years, granddaughter]

Barriers to quality health care

Respondents also talked about avoidance by family and friends. Further, as the respondents shared on their illness trajectories, two barriers that affected the quality of health care for the cervical cancer patients were identified as access to health care and inadequate information on cervical cancer.

Access to health care

Respondents noted that distance to health facility and time taken to see the doctor were hindrances to accessing health care which was by referral at Kenyatta National Hospital. Most of the respondents (14 out of 18) resided from outside Nairobi, the location of the referral hospital. The patients and their caregivers had to travel long distances to get to the hospital. The patients reported that if by chance one missed their set appointment, it would be very difficult to see the doctor.

The patients and their caregivers reported that many patients with all forms of cancer queued for treatment, yet there was only one radiotherapy machine at Kenyatta National Hospital. They noted that a cervical cancer patient could delay starting treatment for up to 3 months, due to the high demand for the services. This aspect made access to timely health care a major challenge as illustrated in the following excerpts:

The machines here have disappointed us more than once. You know my mother was scheduled to start treatment in May 2010 but due to demand she was delayed until July 2010. Maybe if the treatment had been initiated immediately she would be much better. [Caregiver #17, 31 years, son]

After her [the cervical cancer patient] radiotherapy treatment we were then referred again to Kampala… It is really difficult to get your patient to hospital especially if you come from outside Nairobi… Then now with the broken down machine sending patients to Kampala… [Caregiver #1, 59 years, spouse]

Inadequate information on cervical cancer

The respondents reported that they had no prior knowledge of cervical cancer until diagnosed. The respondents noted that the symptoms of cervical cancer were not obvious to them. They often confused the symptoms as minor issues that would soon go away, for example, lower abdominal pains. It is until advanced symptoms like heavy bleeding manifested that the patients reported to have sought treatment. They noted that lack of information on cervical cancer was a challenge as it prolonged their suffering as they sought for diagnosis, yet the cancer was advancing. Citations from two respondents exemplify this:

My problem started in 2008… I only came to know that it was cervical cancer when the bleeding increased and I was admitted in hospital where the diagnosis was later made. If I at least knew the signs and symptoms maybe I would have suspected early enough before the cancer became serious. [Patient #14, 61 years, married]

I started having lower abdominal pains. Then after we had sex with my husband I would bleed. This is when I went to hospital [in 1998]. I however just used to be treated and given medication without knowing what was wrong with me. It was only in 2008 that I came to know that I had cervical cancer. [Patient#10, 45 years, married]

The caregivers also reported that they did not know much about cervical cancer until someone from their family was diagnosed with the condition. They noted that the information on cervical cancer, its risk factors, prevention, intervention, and treatment was not readily available to the public. This is illustrated by the following excerpts:

I wish people can be educated more on cervical cancer. What are the signs and symptoms? What causes it and the risk factors associated to cervical cancer. Maybe if my mother had this knowledge she would have been diagnosed early before her situation got to where it is now… [Caregiver #17, 31 years, son]

Information on the nature and treatment on cervical cancer was the greatest challenge. You know the initial idea one gets when they hear cancer is impending death. However when we saw the doctor and we were explained to us … since I understood the condition better … People need to be educated more on cervical cancer. [Caregiver #4, 44 years, spouse]

Discussion

In Kenya, most cancers are often diagnosed at the advanced stages of the disease. A woman diagnosed with cervical cancer has to now live with a chronic disease faced with structural, physiological and psychological, as well as socioeconomic challenges.12 The management of cervical cancer poses psychosocial and medical challenges that cause disruptions in the lives of the women.

The psychosocial challenges of women living with cervical cancer as illustrated in this study included the high cost of cervical cancer management, anxiety and fear of death, strained family relationships post-diagnosis, body image and sexual health concerns, as well as fear of stigmatization and avoidance. These challenges faced by cancer patients have been reported in other studies.11,13–17

A multiethnic cancer study that included Latinas, non-Latina whites, and African Americans found significantly higher concerns about pain, survival, and sexuality among Latinas.18 Additionally, studies investigating Latino cancer patients’ QOL found that cultural beliefs, family, and religion had significant influences on QOL, including pain expression and management.19

It is evident that cervical cancer places a large burden on patients, their families, their communities, and their health care providers, and affects the well-being of the patient as illustrated in the findings.

Studies elsewhere that include ethnic minority women (specifically African American) have found that breast cancer and its treatments result in physical, economic, and employment problems, familial and marital relationship challenges, and concerns with body image and sexuality.20,21 Cervical cancer management in Kenya at present requires efforts to strengthen the capacity of patients, families, community members, and community support structures to contribute to sufferers’ QOL both at home and in hospital. Although considerable information about self-management by patients with heart disease, cancer, respiratory disease, and diabetes is available, very little exploration of management tasks by patients and caregivers with these conditions is available to inform intervention research on chronic illness management in Kenya. Further research on the management tasks by patients and caregivers is necessary to inform policy and improve service delivery.

Further research on the barriers to cervical cancer management and the role of caregivers in cervical cancer illness trajectories is recommended to provide a broader perspective into the management of cervical cancer and other reproductive health conditions affecting women in Kenya.

Study limitations

The major limitation of this study lies in the use of a small non-probabilistic sample size, which was appropriate for the phenomenological approach used for scientific inquiry. Since this was a qualitative study, the intent was not to generalize the findings.22 The study was intended to provide deeper insights on cervical cancer management through the illness trajectories of women living with cervical cancer in Kenya. In view of these limitations, the study findings should be used with caution in unrelated contexts or settings.

Conclusion

Cervical cancer places a large burden on women, their families, their communities, and their health care providers in Kenya as in the study findings. Positive results for chronic diseases like cervical cancer can only be achieved when patients, families, societies, and health care teams join their efforts in an organized and motivated way.

To address issues relevant to the increasing numbers of women with cervical cancer in Kenya, research studies need to include larger samples of these women. Also important are studies that allow in-depth understanding of the experiences of women living with cervical cancer.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the invaluable input of the respondents. Their voluntary effort and participation in this study are highly regarded. We also appreciate the support of the Institute of Anthropology, Gender and African Studies (IAGAS), University of Nairobi, Kenya.

Footnotes

Authors’ contribution

Mariah Ngutu conceptualized the study and participated in its design, data collection, data analysis, and writing of manuscript. Isaac K Nyamongo participated in the study design, supervision of data collection, analysis, revision and approval of the manuscript.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M, et al. Cancer Incidence Mortality Worldwide GLOBOCAN (10): IARC Cancer Base 11 [Internet] Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2013. [Accessed December 13, 2013]. Available from: http://globocan.iarc.fr. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jan MA, Goldie SJ. Introducing HPV vaccine in developing countries – key challenges and issues. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1908–1910. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp078053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anorlu RI. Cervical cancer: the sub-Saharan perspective. Reprod Health Matters. 2008;16(32):41–49. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(08)32415-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Information Centre on HPV and Cervical Cancer (HPV Information Centre) WHO/ICO Human . Papillomavirus and Related Cancers in Kenya. 2014. (Summary Report). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Official Records of the World Health Organization 1948 No.2. Available from: http://www.who.int/about/definition/en/print.html.

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Measuring Healthy Days. Atlanta, GA: CDC; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Balogun M, Odukoya O, Oyediran M, Ojomu P. Cervical cancer awareness and preventive practices: a challenge for female urban slum dwellers in Lagos, Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health. 2012;16(1):77–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gatune J, Nyamongo I. An ethnographic study of cervical cancer among women in rural Kenya: is there a folk causal model? Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2005;15:1049–1059. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2005.00261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Manen M. Researching Lived Experience: Human Science for an Action Sensitive Pedagogy. London, ON: Althouse; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mulemi BA. Coping with Cancer and Adversity: Hospital Ethnography in Kenya. Leiden: African Studies Centre; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mulemi B. Patients’ perspectives on hospitalization: experiences from a cancer ward in Kenya. Anthropol Med. 2008;15(2):117–131. doi: 10.1080/13648470802122032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sellors J, Muhombe K, Castro W. Palliative Care for Women with Cervical Cancer: A Kenya Field Manual. Seattle, WA: PATH; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Bank . World Development Report 1993: Investing in Health. New York: Oxford University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sherris J, Herdman C, Elias C. Beyond our borders: cervical cancer in the developing world. West J Med. 2001;175(4):231–233. doi: 10.1136/ewjm.175.4.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.International Agency for Research on Cancer IARC . IARC Monographs. Vol. 9. Lyon: IARC Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 16.WHO . Global Action Against Cancer Now. Updated version. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alliance for Cervical Cancer Prevention (ACCP) Women’s Stories, Women’s Lives: Experiences with Cervical Cancer Screening and Treatment. Seattle: ACCP; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spencer SM, Lehman JM, Wynings C, et al. Concerns about breast cancer and relations to psychosocial well-being in a multiethnic sample of early stage patients. Health Psychol. 1999;18:159–168. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.18.2.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Juarez G, Ferrell B, Borneman T. Influence of culture on cancer pain management in Hispanic patients. Cancer Pract. 1998;6:262–269. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.1998.00020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ashing-Giwa K, Ganz P, Petersen L. Quality of life in African American and White long-term breast cancer survivors. Cancer. 1999;85(2):418–426. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990115)85:2<418::aid-cncr20>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ashing-Giwa K, Ganz P. Understanding the experience of breast cancer in African-American women. J Psychosoc Oncol. 1997;15(2):19–35. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Polit DF, Hungler BP. Nursing Research Principles and Methods. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1995. [Google Scholar]