Abstract

Study Objectives

To review the clinical presentation, evaluation and management of normal-weight, overweight and obese adolescent and young adult women with PCOS over 2-year follow-up.

Design

Retrospective chart review

Participants

173 adolescent and young adult women, aged 12–22 years, diagnosed with PCOS

Interventions

Demographic, health data, and laboratory measures were abstracted from 3 clinic visits: baseline and 1- and 2- year follow-up. Subjects were classified as normal-weight (NW), overweight (OW) or obese (OB). Longitudinal data were analyzed using repeated measures ANOVA.

Main Outcome Measures

BMI, self-reported concerns, lifestyle changes.

Results

Most patients (73%) were OW or OB. Family history of type II diabetes was greater in OW (38%) and OB (53%) as compared to NW (22%) patients (p=0.002). Acanthosis nigricans was identified in OW (62%) and OB (21%) patients, but not NW patients (0%; p <0.001). OW and OB patients had higher fasting insulin (p<0.001) and lower HDL cholesterol (p=0.005) than NW patients, although screening rates were low. BMI Z-scores decreased in both OW and OB patients over time (0.07 units/year; p<0.001).

Conclusions

Most patients with PCOS were OW/OB. Substantial clinical variability existed in CVD screening; among those screened, OW and OB patients had greater CVD risk factors. Despite self-reported concerns about weight and diabetes risk among OW/OB patients, no clinically significant change in BMI percentile occurred. Evidence-based interventions and recommendations for screening tests are needed to address CVD risk in adolescents and young adults with PCOS.

Keywords: obesity, insulin resistance, PCOS, cardiovascular risk factors, adolescents

Introduction

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a very common endocrinopathy, occurring in 5–10% of adolescent girls and women of reproductive age1. PCOS is a chronic condition characterized by oligomenorrhea and/or anovulation and clinical and/or biochemical demonstration of androgen excess, with or without polycystic ovaries on ultrasound. Clinical findings of PCOS are heterogeneous, and may include irregular menstrual cycles, hirsutism, acne, obesity, acanthosis nigricans, and infertility.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is one of the leading causes of mortality and morbidity in adult women in the United States2. Women with PCOS are at risk for CVD, as comorbidities of PCOS include obesity, insulin resistance, Type II diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia. Approximately half the adult women with PCOS are overweight or obese3. The majority of adults with PCOS have insulin resistance (IR), impaired glucose tolerance (IGT), or compensatory hyperinsulinemia4; these abnormalities are independent of BMI5, 6. Women with PCOS have a 10-fold increased risk of developing Type II diabetes and a 2–3 times higher prevalence of metabolic syndrome compared to age-matched and weight-matched controls7.

PCOS is increasingly recognized at earlier ages. Adolescents with PCOS exhibit clinical, metabolic, and endocrine features similar to those of adults5, 8. Obesity is seen in over half of adolescent girls with PCOS9. PCOS is the leading cause of glucose intolerance and insulin resistance in adolescent females10, and young women with PCOS have 10-fold higher rates of type II diabetes than young women without PCOS7. Adolescents with PCOS are more than 4 times more likely to have metabolic syndrome than the general adolescent population, even after controlling for weight11. Obese young women with PCOS demonstrate early evidence of CVD, with a 5-fold higher prevalence of sub-clinical coronary atherosclerosis, compared to age- and BMI-matched controls12.

To our knowledge, no studies to date have examined the longitudinal evaluation and management of cardiovascular risk factors, self-reported concerns, or lifestyle changes in adolescents with PCOS in the routine clinical setting. The objectives of the present study were to review the clinical presentation, evaluation, and management of normal-weight (NW), overweight (OW), and obese (OB) adolescents and young adult women with PCOS seen at an Adolescent Clinic in a large tertiary-care pediatric hospital over time.

Materials and Methods

Using ICD-9 diagnosis codes, we identified 928 patients with PCOS who were seen from January 2006 through December 2008 in the Adolescent Medicine Practice at Boston Children’s Hospital (BCH). From this group, 180 patients were randomly selected using statistical software. The study was approved by the BCH Committee on Clinical Investigations. PCOS was defined using the Androgen Excess- PCOS Society (AE-PCOS) Consensus Criteria13: ovulatory dysfunction plus clinical or biochemical evidence of hyperandrogenism (hirsutism, elevated serum androgens) with the exclusion of secondary causes (pregnancy, congenital adrenal hyperplasia, androgen-secreting tumors, hyperprolactinemia, hypothyroidism). Eligible patients had been diagnosed with PCOS between ages 12–22 years, and had laboratory studies performed to exclude secondary causes of ovulatory dysfunction. Subjects were excluded from this sample if they did not meet the full AE-PCOS diagnostic criteria for PCOS, if they were outside the eligible age range, or if they had an alternative cause of ovulatory dysfunction, leaving a total of 173 patients in our cohort.

Medical records of eligible patients were reviewed for details of initial presentation, including demographic data, health history, physical examination findings, and pre-treatment laboratory results. This information was recorded by the treating clinician at time of the patient visit. Menstrual history included age at menarche, pattern of menses, amount/duration of bleeding, and use of hormonal medications. Complaints of acne, hirsutism, hair loss, menstrual irregularity, and weight gain or difficulty maintaining healthy weight were recorded. A positive family history of PCOS, adult-onset diabetes, infertility, or irregular menses was recorded. Self-reported race and ethnicity were obtained from the BCH electronic record.

Height, weight, systolic blood pressure (SBP), and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) were recorded at each visit. Body mass index (BMI) and BMI Z-scores (standard deviations, adjusted for age and sex in patients ages 12–17 years, and adjusted for sex in patients ages 18–22 years) were calculated. Subjects were assigned to one of three weight categories14,15: 1) Normal-weight (NW), a BMI < 85th percentile for age and sex in patients ages 12–17 years, and BMI 18.5–24.9 kg/m2 in patient ages 18–22 years; 2) Overweight (OW), a BMI between 85th to 94th percentile for age and sex in patients ages 12–17 years, and 25.0–29.9 kg/m2 in patients ages 18–22 years; and 3) Obese (OB), a BMI ≥ 95th percentile for age and sex in patients ages 12–17 years, and > 30.0 kg/m2 in patients ages 18–22 years The presence of hypertension (blood pressure ≥95th percentile for age and sex in patients ages 12–17 years16 and ≥ 140 mmHg SBP and 90 mmHg DBP for patients ages 18–22 years17) was recorded, and SBP and DBP Z-scores were calculated for each patient. The presence of hirsutism, acne, androgenic alopecia, acanthosis nigricans, or clitoromegaly on physical exam was noted.

Laboratory investigations included lipid levels (triglycerides, total cholesterol, low density lipoprotein [LDL], high density lipoprotein [HDL]) and measures of glucose metabolism (fasting serum glucose, fasting serum insulin, 2-hour serum glucose).

At 1- and 2-year follow-up visits, BMI, blood pressure, and any additional laboratory studies were collected. Each patient’s subjective report of nutritional changes and exercise, as well as patient concerns about weight, menses, acne, hair growth, diabetes/insulin resistance, fertility, and mood were abstracted from the medical record. If this information was not available in the medical record, it was categorized as “missing.”

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or mean ± standard error for continuous variables, and frequencies (percentages) for categorical variables. One-way ANOVA was used to test for differences between baseline weight status groups on continuous variables. Chi-squared tests or Fisher’s exact test where appropriate were used to test for differences across baseline weight groups on categorical variables. To test for changes between visits, t-tests were used for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. Trends and changes in longitudinal data from all three visits were tested using repeated measures ANOVA.

Results

Baseline data

Demographics

Our final sample consisted of 46 NW patients (26%), 36 OW patients (22%), and 91 OB patients (52%) (Table 1) who had an average age of 15.9 ± 2.1 years. NW patients tended to be older than the OW or OB patients (p=0.04). The ethnic background of the cohort was diverse; 100 patients (65%) self-identified as White, 29 patients (19%) as Black, 12 patients (8%) as Hispanic, 12 patients (8%) as Asian/other. There was no significant difference in ethnicity/race by weight status.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study population at initial visit by weight status

| Participant Characteristic | n (%) or Mean (SD) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Participants (n=173) |

Normal Weight (n=46) |

Overweight (n=36) |

Obese (n=91) |

p-value | ||

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age (years) | 15.9 (2.1) | 16.5 (1.8) | 15.9 (2.2) | 15.6 (2.1) | 0.04 | |

| Race/Ethnicity (n=153) | 0.07 | |||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 100 (65%) | 34 (83%) | 20 (61%) | 46 (58%) | ||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 29 (19%) | 4 (10%) | 7 (21%) | 18 (23%) | ||

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 9 (6%) | 1 (2%) | 4 (12%) | 4 (5%) | ||

| Non-Hispanic Other | 3 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (3%) | 1 (1%) | ||

| Hispanic | 12 (8%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (3%) | 10 (13%) | ||

| BMI | ||||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.7 (7.5) | 21.5 (1.9) | 26.2 (1.7) | 35.4 (5.7) | <.001 | |

| BMI Z-score | 1.5 (0.9) | 0.2 (0.6) | 1.3 (0.2) | 2.2 (0.3) | <.001 | |

| BMI Percentile | 85.9 (19.8) | 58.3 (20.5) | 90.2 (3.5) | 98.0 (1.3) | <.001 | |

| Blood Pressure | ||||||

| Systolic BP (mm Hg) | 119.4 (14.6) | 114.8 (11.1) | 117.9 (20.6) | 122.2 (12.6) | 0.01 | |

| SBP Z-score | 0.8 (1.4) | 0.4 (1.1) | 0.7 (2.1) | 1.1 (1.2) | 0.07 | |

| Diastolic BP (mm Hg) | 66.9 (8.0) | 64.5 (7.9) | 67.1 (6.7) | 68.0 (8.4) | 0.06 | |

| DBP Z-score | 0.1 (0.7) | −0.1 (0.7) | 0.1 (0.6) | 0.2 (0.7) | 0.20 | |

| Family History | ||||||

| PCOS | 17 (10%) | 6 (13%) | 4 (10%) | 7 (8%) | 0.53 | |

| Diabetes (Type II) | 73 (41%) | 10 (22%) | 15 (38%) | 48 (53%) | 0.00 | |

| Infertility/Irregular Menses | 46 (26%) | 12 (26%) | 14 (36%) | 20 (22%) | 0.25 | |

| Physical Exam Findings | ||||||

| Acanthosis nigricans | 64 (36%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (21%) | 56 (62%) | <.001 | |

| Acne | 78 (44%) | 20 (43%) | 19 (49%) | 39 (43%) | 0.82 | |

| Hirsutism | 107 (61%) | 33 (72%) | 24 (62%) | 50 (55%) | 0.16 | |

Family History

A positive family history of PCOS (n=17, 10%) or infertility/irregular menses (n=46, 26%) was common. There were no differences between NW, OW, or OB patients in regards to these variables. A family history of type II diabetes was more prevalent in OB (53%) and OW (38%) patients as compared to NW patients (22%; p=0.002).

Clinical features

At baseline, SBP and DBP Z-scores were similar between NW and OW patients. Acanthosis nigricans was identified in OB and OW patients (62% vs. 21%), but not in NW patients (p <0.001). Rates of hirsutism and acne did not differ between weight groups (p >0.05).

Laboratory Studies

Fasting glucose and insulin were performed for 73 (41%) and 63 (35.7%) patients respectively, the majority of whom were OW or OB (Table 2). Among NW patients with a family history of diabetes type II (10 patients), 5 patients had fasting insulin performed, 4 patients had fasting glucose performed, and 2 patients had 2-hour glucose performed. Almost 24% of the total sample underwent a 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test; of those subjects, 85% were OB. Although there were no differences in fasting glucose between weight groups, OB and OW patients had higher fasting insulin than NW patients (26.7 ± 2.3 mcU/mL vs. 14.3 ± 2.1 mcU/mL vs. 9.6 ± 2.3 mcU/mL; p<0.001). Lipid measurements were performed on 22% to 45% of total cohort, the majority of who was OB. Total cholesterol, LDL, and triglycerides did not differ between groups. OB and OW patients had lower HDL than NW patients (44.6 ± 1.9 mg/dL vs. 48.0 ± 4.9 mg/dL vs. 59.3 ± 3.8 mg/dL; p=0.005).

Table 2.

Laboratory values at initial visit by weight status (N=173)

| Participant Characteristic | Mean ± Standard Error | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | All Participants |

N | Normal Weight (n=46) |

N | Overweight (n=36) |

N | Obese (n=91) |

p-value | |

| Fasting Glucose (mg/dL) | 73 | 83.8 ± 1.0 | 7 | 83.7 ± 2.0 | 16 | 82.0 ± 1.6 | 50 | 84.4 ± 1.3 | 0.61 |

| Fasting Insulin (mcU/mL) | 63 | 21.7 ± 1.8 | 9 | 9.6 ± 2.3 | 13 | 14.3 ± 2.1 | 41 | 26.7 ± 2.3 | <.001 |

| 2-Hour Glucose (mg/dL) | 42 | 101.5 ± 3.9 | 2 | 88.5 ± 4.5 | 4 | 91.3 ± 10.9 | 36 | 103.3 ± 4.4 | 0.52 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 63 | 120.3 ± 8.1 | 11 | 94.6 ± 9.8 | 10 | 143.0 ± 27.8 | 42 | 121.7 ± 9.7 | 0.22 |

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 82 | 167.7 ± 4.0 | 17 | 160.2 ± 7.2 | 14 | 169.9 ± 11.1 | 51 | 169.6 ± 5.1 | 0.63 |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 57 | 102.0 ± 4.5 | 11 | 92.9 ± 6.5 | 9 | 101.1 ± 12.4 | 37 | 104.9 ± 5.9 | 0.59 |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 76 | 47.8 ± 1.7 | 14 | 59.3 ± 3.8 | 12 | 48.0 ± 4.9 | 50 | 44.6 ± 1.9 | 0.01 |

LH, luteinizing hormone; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; DHEAS, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate; SHBG, sex hormone binding globulin; LDL, low density lipoprotein; HDL, high density lipoprotein.

Longitudinal data

Clinical features

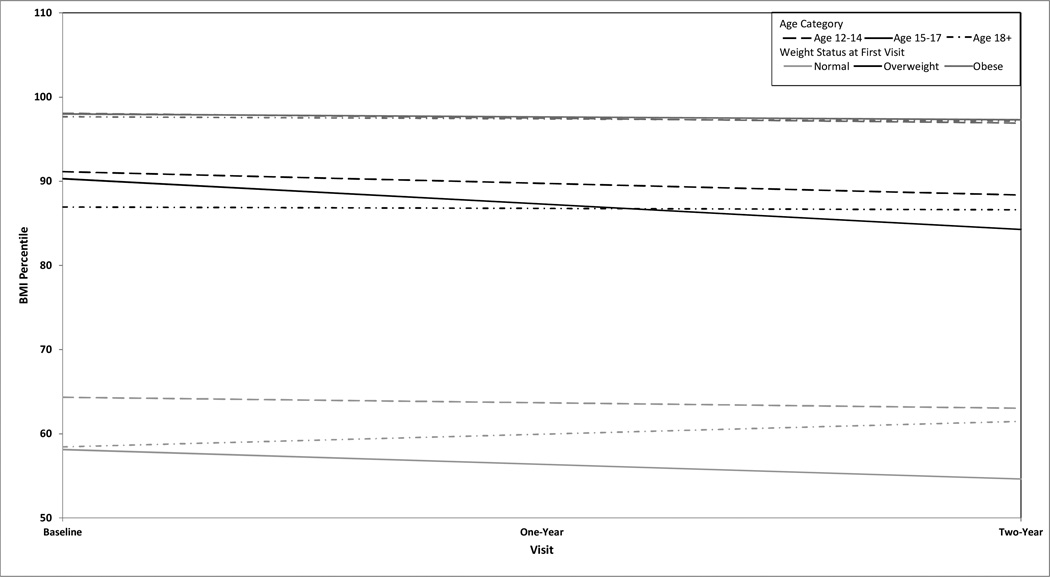

BMI Z-scores were tracked over time. The BMI Z-score declined in OB (decrease of 0.07 units/year; p<0.001) and OW (decrease of 0.08 units per year; p =0.01) patients, but not in the NW group (decrease of 0.01 units per year; p =0.72). These changes in BMI Z-score correspond to a BMI percentile change/year of −0.4 ± 0.1% in OB patients (p <0.001) and −2.2 ± 0.7% in OW patients (p=0.002) (Figure 1). Despite these changes, both OW and OB patients remained within their same weight categories at 1- and 2-year follow-up.

Figure 1.

BMI trend at 1- and 2-year follow-up by age category and weight status.

Patient age had some impact upon changes in weight status over the 2-year follow-up. Overall, younger OB patients demonstrated reductions in BMI percentile (ages 12–14 years = −0.58 ± 0.16; p<0.001 and ages 15–17 years= −0.35 ± 0.17; p=0.041), while older OB patients did not (age ≥ 18 years = −0.26 ± 0.23; p=0.272). Only OW patients aged 15–17 years had changes in BMI percentile over time (−3.02 ± 1.05; p=0.007); the other age groups showed no change. NW patients had no significant changes in BMI percentile over time regardless of age category.

No significant changes occurred in SBP Z-score over time in any weight category, across age groups, over 2- year follow-up. DBP Z-score only changed in NW patients aged 18 years or older (0.41 ± 0.17 per year; p=0.04).

Medications

At baseline visit, a total of 10 patients were taking a combined estrogen/progestin medication (9 patients) or progestin-only medication (1 patient); no patients were taking metformin. There were no statistical differences between patients by weight category and baseline medications. Medication use by weight category at baseline is as follows: OB (4 combined, 0 progestin only, 0 metformin); OW (1 combined, 0 progestin only, 0 metformin); NW (4 combined, 1 progestin only, 0 metformin).

At 1-year follow-up visits, 110 total patients had been prescribed a combined estrogen/progestin medication, 8 had been prescribed progestin-only medication, 32 had been prescribed metformin, and 20 had been prescribed spironolactone. Prescribing patterns at 1-year follow-up were: OB (52 combined, 4 progestin only, 27 metformin, 9 spironolactone); OW (24 combined, 1 progestin only, 5 metformin, 3 spironolactone); NW (34 combined, 3 progestin only, 0 metformin, 8 spironolactone).

At 2 –year follow-up, 70 total patients had been prescribed combined estrogen/progestin medication, 3 had been prescribed progestin only medication, 25 metformin and 19 were prescribed spironolactone. Prescribing patterns at 2-year follow-up were: OB (31 combined, 0 progestin only, 21 metformin, 8 spironolactone); OW (16 combined, 1 progestin only, 4 metformin, 2 spironolactone); NW (23 combined, 2 progestin only, 0 metformin, 9 spironolactone).

Across weight categories, prescribed medications were not associated with changes in BMI. Within age categories, there were differences in prescribing by weight category. Among 15–17 year old patient, NW patients were more likely to be prescribed combined estrogen/progestin at one-year follow-up, while OB patients in the same age group were more likely to receive metformin therapy at follow-up visits. OW or OB patients 18 years or older were more likely to have been prescribed metformin at two-year follow-up. No other age group and weight category difference in prescribing was readily apparent.

Laboratory Studies

Measures of insulin resistance and glucose metabolism were not commonly monitored over time. Less than 10% of patients who had studies performed at baseline had laboratory testing repeated.

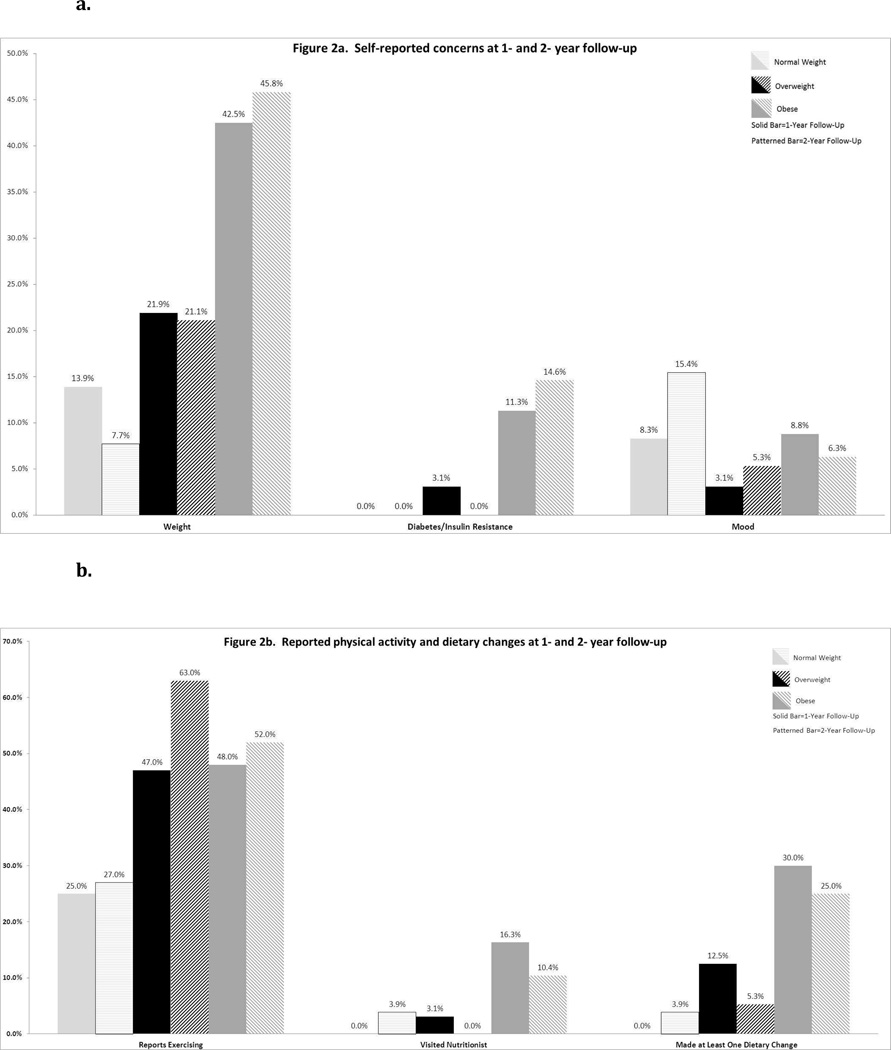

Self-reported concerns and lifestyle changes

Self-reported concerns, including weight dissatisfaction, fear of diabetes, and disturbances of mood varied by weight groups (Figure 2a). OW and OB patients had more concerns about weight and diabetes/insulin resistance than NW patients (p≤0.05 at both follow-up points). BMI Z-scores did not change over the subsequent year in patients reporting concerns about weight or diabetes at the one-year assessment. NW patients appeared more likely to report concerns about mood as compared to OW and OB patients, but these differences were not statistically significant. Self-reported lifestyle changes were also assessed by weight category (Figure 2b). OB and OW patients reported more participation in exercise than NW patients at 1-year (p=0.056) and 2-year (p=0.04) follow-up. OB patients were more likely to have had a visit with a nutritionist (16% and 10% at 1- and 2- year, respectively). While OB patients were more likely to have made ≥1 general dietary change at 1-year (p<0.001) and 2-year (p=0.03), few patients overall reported specific nutritional changes, such as smaller portions, less sugared beverages, or specific diet plan (low fat, low glycemic index, low carbohydrate).

Figure 2.

Self-reported concerns (Figure 2a), physical activity and dietary changes (Figure 2b) at 1- and 2-year follow-up.

Discussion

In this study of a large clinical sample of adolescent and young adult women with PCOS, overall screening rates for CVD risk factors were quite low. OW and OB patients with PCOS were more likely to be screened and subsequently diagnosed with CVD risk factors as compared to their NW counterparts.

The majority of patients with PCOS in our sample were overweight or obese (73.8%), regardless of ethnic background, as has been previously shown16, 1, 17; this prevalence is higher than that described in adults3. NW patients tended to be older than OW/OB patients at their baseline visit, suggesting that NW patients with PCOS are diagnosed or referred for tertiary-care evaluation at a later age. While adults with PCOS have insulin resistance regardless of weight status5, 6, we found that OW and OB patients had a higher rate of hyperinsulinemia risk factors than NW patients, as evidenced by the presence of acanthosis nigricans and a greater prevalence of a family history of Type II diabetes.

Known lipid abnormalities in adults with PCOS include elevated LDL, elevated triglycerides, and low HDL18, 19. In our cohort, HDL was lower in OW and OB patients than NW patients, as is seen in association with insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome. LDL was not higher in OB patients, as has been previously shown5.

Our data reflect substantial clinical variability in the diagnosis of PCOS and screening for CVD risk factors. This practice heterogeneity has also been studied by the North American Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology (NASPAG) research committee. In a study of 127 clinical providers, 61% reported obtaining a lipid panel, 60% glucose, 41% insulin and 25% hemoglobin A1c20. This variability likely reflects the lack of specific guidelines for cardiovascular risk factor screening and management in adolescents with PCOS, and highlights the need for further studies such as ours to better guide clinical care.

The AE-PCOS society released guidelines for assessing CVD risk factors in PCOS in May 201021, after these data were collected. These guidelines note the importance of lifetime CVD prevention due to the prevalence of insulin resistance in adults with PCOS, which exists regardless of weight status22. They state that women with PCOS should be screened for CVD risk factors: 1) waist circumference, BMI, and BP determined at every visit; 2) a complete fasting lipid profile obtained at initial evaluation, and reassessed every 2 years or sooner if weight gain occurs; and 3) a 2-hour oral glucose challenge performed for patients with a BMI > 30 kg/m2 or in lean women with family history of Type II diabetes. In our sample, waist circumference was not measured during clinical visits. While 46% of the total cohort had baseline total cholesterol screening, fewer had screening for triglycerides (35.7%), LDL (32.3%), or HDL (43.1%). Less than half (45%) of OB patients in our population had baseline fasting insulin, and only 39% of OB patients in our population had an OGTT performed. The clinical variability in evaluation for diabetes mellitus and hyperinsulinemia reflects the lack of clear guidelines for practitioners caring for adolescent and young adult women with PCOS. If the adult-focused guidelines were followed, the 10 NW patients with family history of Type II diabetes should have had an OGTT performed; however, while 9 of these patients had any glucose or insulin screening, none of them had an OGTT performed. Our findings reflect actual clinical care at a subspecialty clinic, and demonstrate the lack of evidence-based algorithms for adolescent and young adult women with PCOS available for providers to follow to best manage these patients.

Our study allowed longitudinal follow-up. During these 2 years, NW patients had no changes in BMI; this finding held true even when data were stratified by age group. OW and OB patients demonstrated statistically significant, but not clinically significant, decreases in BMI Z-scores over time (Figure 1) across all age groups. Neither OW or OB patients were able to improve weight status and move to a healthier weight category over time; patients in both categories maintained a BMI percentile above the 85th or 95th percentile, respectively. Age somewhat impacted the trajectory of BMI for OB patients. The youngest OB patients (ages 12–17 years) demonstrated decreases in BMI percentiles over two years. In contrast, BMI percentiles did not change for the oldest OB patients (≥ 18 years). While numbers screened were small, and interpretation of these findings is limited by small sample size for older patient, our data suggest that older adolescents and young adults may have a more difficult time implementing nutritional and exercise changes.

Lifestyle change is the hallmark of all therapies for PCOS23. Only a 5–7% decrease in body weight can improve menstrual function and ovulation24, as well as lower risk of progression from IGT to diabetes25. The lack of a clinically significant change in weight status lies in contrast to the patients’ self-reported weight concerns (Figure 2a). Positive lifestyle changes that would support healthy weight loss were rare in our cohort. Less than 50% of OW or OB patients exercised, and less than 20% had visited with a nutritionist. Although 43% OW and OB patients stated they had made ≥1 dietary change, less than 15% reported any specific alterations (Figure 2b). Our findings emphasize the need for effective counseling on concrete options for lifestyle modification, including nutrition and exercise. Multidisciplinary clinics with medical providers, nutritionists, and health psychologists may be an effective approach26, however, studies are limited.

One strength of this study is that our cohort is representative of typical clinical care for adolescent and young adult women with PCOS, and that much can be learned from these “real life” data. To our knowledge, ours is the first study to follow an adolescent and young adult population with PCOS longitudinally in a “real life” outpatient setting, outside of a clinical trial. Additionally, it has assessed patients’ self-reported concerns and lifestyle changes over time. However, this study has limitations inherent to a retrospective chart review. As data were not systematically collected, variability in the collection and recording of data by providers occurred during visits. The small number of patients who had laboratory screening could have impacted study results. The study was not able to evaluate the extent of the medical or nutritional counseling that took place during visits. Given the small number of patients prescribed medications in this sample, we could not evaluate whether medications contributed to BMI change.

In summary, patients with PCOS are at increased risk for cardiovascular and metabolic abnormalities during adolescence and adulthood. Despite these risks, there is substantial variability in CVD screening and management among providers. In our study, the majority of patients with PCOS were OW or OB; among those screened, OW or OB patients demonstrated greater prevalence of hyperinsulinemia and dyslipidemia. Despite reported concerns about weight and nutrition from the OB patients, no clinically significant changes in BMI were seen; at 2-year follow-up, BMI percentiles for OB patients remained in the “obese” range. Data on adolescent and young adult women with PCOS are limited, and there are no current evidence-based guidelines regarding appropriate investigations or management of adolescent and young adult women with PCOS. Increased awareness of co-morbidities and long-term cardiovascular and metabolic risks in adolescents with PCOS is required to allow for earlier detection and treatment. Effective interventions and evidence-based recommendations for optimal screening tests and intervals are needed to address cardiovascular risk in adolescent and young adult women with PCOS.

Acknowledgments

Tamara Baer’s work on this study was supported in part by the Leadership Education in Adolescent Health Training grant #T71MC00009 from the Maternal and Child Health Bureau, Health Resources and Services Administration. Amy DiVasta’s work on this study was supported by NICHD K23 HD060066. The authors have no financial relationships to disclose.

Tamara Baer wrote the first draft of the paper, and did not receive any honorarium, grant or other payment to produce this manuscript. Tamara Baer is the reprint request author.

Source of funding: Tamara Baer’s work on this study was supported in part by the Leadership Education in Adolescent Health Training grant #T71MC00009 from the Maternal and Child Health Bureau, Health Resources and Services Administration. Amy DiVasta’s work on this study was supported by NICHD K23 HD060066.

Abbreviations

- PCOS

Polycystic ovary syndrome

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- NW

normal-weight

- OW

overweight

- OB

obese

- BMI

body mass index

- IR

insulin resistance

- IGT

impaired glucose tolerance

- BCH

Boston Children’s Hospital

- AE-PCOS

Androgen Excess- PCOS Society

- SBP

systolic blood pressure

- DBP

diastolic blood pressure

- LDL

low density lipoprotein

- HDL

high density lipoprotein

- SD

standard deviation

- LH

luteinizing hormone

- FSH

follicle-stimulating hormone

- DHEAS

dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate

- SHBG

sex hormone binding globulin

- OGTT

oral glucose tolerance test

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

None of the authors have conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Orsino A, Van Eyk N, Hamilton J. Clinical features, investigations and management of adolescents with polycystic ovary syndrome. Paediatr Child Health. 2005;10:602. doi: 10.1093/pch/10.10.602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Deaths, percent of total deaths, and death rates for the 15 leading causes of death in 5-year age groups, by race and sex: United States. [Accessed on April 17, 2013];2010 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/dvs/LCWK1_2010.pdf.

- 3.Gambineri A, Pelusi C, Vicennati V, et al. Obesity and the polycystic ovary syndrome. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2002;26:883. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barbieri RL, Smith S, Ryan KJ. The role of hyperinsulinemia in the pathogenesis of ovarian hyperandrogenism. Fertil Steril. 1988;50:197. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)60060-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silfen ME, Denburg MR, Manibo AM, et al. Early endocrine, metabolic, and sonographic characteristics of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): comparison between nonobese and obese adolescents. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:4682. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morales AJ, Laughlin GA, Butzow T, et al. Insulin, somatotropic, and luteinizing hormone axes in lean and obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome: common and distinct features. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:2854. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.8.8768842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nestler JE. Metformin for the treatment of the polycystic ovary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:47. doi: 10.1056/NEJMct0707092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hart R, Doherty DA, Mori T, et al. Extent of metabolic risk in adolescent girls with features of polycyctic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:2347. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Leo V, Musacchio MC, Morgante G, et al. Metformin treatment is effective in obese teenage girls with PCOS. Human Reprod. 2006;21:2252. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palmert MR, Gordon CM, Kartashov AI, et al. Screening for abnormal glucose tolerance in adolescents with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:1017. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.3.8305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coviello AD, Legro RS, Dunaif A. Adolescent girls with polycystic ovary syndrome have an increased risk of the metabolic syndrome associated with increasing androgen levels independent of obesity and insulin resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:492. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shroff R, Kerchner A, Maifeld M, et al. Young obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome have evidence of early coronary atherosclerosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:4609. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Azziz R, Carmina E, Dewailly D, et al. Positions statement: criteria for defining polycystic ovary syndrome as a predominantly hyperandrogenic syndrome: an Androgen Excess Society guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:4237. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barlow SE. the Expert Committee: Expert committee recommendations regarding the prevention, assessment, and treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity: summary report. Pediatrics. 2007;120:S164. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2329C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the NIH. Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults. [on August 21, 2014];NIH publication. 1998 Sep;:98–4083. Retrieved from http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/files/docs/guidelines/ob_gdlns.pdf.

- 16.US Department of Health and Human Services. The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. [Accessed October 11, 2013]; Retrieved from http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/prof/heart/hbp/hbp_ped.pdf.

- 17.American Academy of Pediatrics. Expert panel on integrated guidelines for cardiovascular health and risk in children and adolescents: summary report. Pediatrics. 2011;128:S213–S256. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2107C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bekx MT, Connor EC, Allen DB. Characteristics of adolescents presenting to a multidisciplinary clinic for polycystic ovary syndrome. J Pediatri Adolesc Gynecol. 2010;23:7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geier LM, Bekx MD, Connor EL. Factors contributing to initial weight loss among adolescents with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2012;25:367. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2012.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Legro RS, Kunselman AR, Dunaif A. Prevalence and predictors of dyslipidemia in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Am J Med. 2001;111:607. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00948-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mather KJ, Kwan F, Corenblum B. Hyperinsulinemia in polycystic ovary syndrome correlates with increased cardiovascular risk independent of obesity. Fertil Steril. 2000;73:150. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(99)00468-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bonny AE, Appelbaum H, Connor EL, et al. Clinical variability in approaches to polycystic ovary syndrome. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2012;25:259. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2012.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wild RA, Carmina E, Diamanti-Kandarakis E, et al. Assessment of cardiovascular risk and prevention of cardiovascular disease in women with the polycystic ovary disease: a consensus statement by the Androgen Excess and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (AE-PCOS) Society. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:2038. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Flannery CA, Rackow B, Cong X, et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome in adolescence: impaired glucose tolerance occurs across the spectrum of BMI. Pediatr Diabetes. 2013;14:42. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2012.00902.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 108: Polycystic ovary syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:936. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181bd12cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pasquali R, Antenucci D, Casimirri F, et al. Clinical and hormonal characteristics of obese amenorrheic hyperandrogenic women before and after weight loss. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1989;68:173. doi: 10.1210/jcem-68-1-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Practice Committee of American Society of Reproductive Medicine: Use of insulin-sensitizing agents in the treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2008;90:S69. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Geier LM, Bekx MT, Connor EL. Factors contributing to initial weight loss among adolescents with PCOS. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2012;25:367. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2012.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]