The suspected culprit in Alzheimer’s disease has been γ-secretase, an enzyme that cleaves type 1 transmembrane proteins. Its targets include the amyloid precursor protein (APP), generating the β-amyloid (Aβ) peptides that give rise to the characteristic brain plaques of Alzheimer’s disease patients. Presenilin is the presumptive catalytic subunit of γ-secretase, and mutations in the PSEN1 and PSEN2 genes that encode this subunit are the most common cause of familial Alzheimer’s disease. On page xxx of this issue, Wang et al. (1) report that mutations in PSEN1 are also associated with a severe skin disorder, acne inversa. Mutations in genes encoding two other subunits of γ-secretase are also linked to this severe skin condition. The finding raises questions about the function of γ-secretase in human diseases, with implications for the development of therapeutics.

A key unresolved question is whether PSEN mutations cause familial Alzheimer’s disease through loss of presenilin function and/or through increased production of longer Aβ peptides (2, 3). PSEN mutations in familial Alzheimer’s disease are almost exclusively missense, and the absence of nonsense or frameshift mutations argues against haploinsufficiency (only a single functional copy of a gene) and favors a disease mechanism based on gain of function by the mutant protein. However, the distribution of pathogenic mutations throughout the PSEN coding sequence is most compatible with a loss of protein function. Indeed, PSEN mutations that cause familial Alzheimer’s disease impair the proteolytic activity of the mutant protein (2), and inactivation of presenilins in the adult mouse brain causes neurodegeneration (4), whereas Aβ overproduction does not (5). In addition, γ-secretase inhibitors can mimic the effects of pathogenic PSEN mutations on APP processing, suggesting that overproduction of longer Aβ is a manifestation of partial loss of presenilin function (2).

Wang et al. reveal that mutations in PSEN1, as well as in the PSENEN and NCSTN genes that encode the PEN2 and nicastrin subunits of γ-secretase, respectively, cause acne inversa. Six different mutations in these three genes were identified in six families with dominant transmission of a rare atypical form of acne inversa. Remarkably, all of the mutations segregated with the disease with complete penetrance despite the genetic heterogeneity among the families. Because all of the mutations are predicted to inactivate protein function, haploinsufficiency of these genes appears to lead to acne inversa. This is consistent with mouse studies showing that γ-secretase deficiency produces follicular hyperkeratosis (6, 7), the initiating event in acne inversa. Similar disorders are observed in mice with skin-specific inactivation of the Notch1 gene, which encodes another transmembrane protein cleaved by γ-secretase, suggesting that Notch1 is the enzyme’s relevant substrate in acne inversa (8).

What do these findings from a disparate clinical disorder tell us about familial Alzheimer’s disease? The major implication is that inactivating and missense mutations in PSEN1 produce different clinical phenotypes, hinting at different disease mechanisms. Although Notch1 appears to be the relevant substrate in acne inversa, it is unclear whether Notch1 is involved in presenilin-dependent neuronal survival in the aging brain. Furthermore, the absence of dementia in the families with acne inversa suggests that PSEN1 haploinsufficiency is unlikely to cause familial Alzheimer’s disease, although the acne inversa–affected family transmitting the PSEN1 mutation includes just four affected individuals, and delayed onset and/or subtle signs of dementia cannot be excluded.

Conversely, Wang et al. note that acne inversa has not been reported in association with Alzheimer’s disease, which is surprising given the 1 to 4% prevalence of acne inverse in the general population (9). Moreover, some PSEN1 mutations in familial Alzheimer’s disease cause a complete loss of Notch processing in cultured cells (10), which would be expected to mimic the phenotypic effects of the PSEN1 mutation in familial acne inversa. In addition, loss of a single Psen1 allele in mice does not produce skin disorders, which occur only with more severe reductions of presenilin expression. These inconsistencies raise the possibility that loss-of-function mutations in PSEN1 may not always produce acne inversa with full penetrance, and that genetic modifiers may contribute to development of acne inversa in the reported families.

Although PSEN mutations in familial Alzheimer’s disease impair protein function, the missense nature of these mutations suggests that expression of the mutant protein is necessary to produce the disease. PSEN mutations could enhance production of longer Aβ by decreasing the proteolytic efficiency of the mutant protein (11). This model, however, is not compatible with the inability of presenilins bearing some pathogenic mutations to generate Aβ (12). Alternatively, mutant presenilin could influence the activity of wild-type presenilin in a dominant-negative manner (2). Such a “gain of negative function” model would reconcile the dominant inheritance of PSEN mutations with their deleterious effects on protein function. That presenilin is the only γ-secretase subunit targeted by mutations in familial Alzheimer’s disease further suggests that γ-secretase–independent functions of presenilins may be important in disease pathogenesis. Presenilins are required for synaptic function and neuronal survival in the adult brain (4, 13), establishing important links to neural processes perturbed in Alzheimer’s disease, but the effector mechanisms mediating these essential activities are presently unclear.

A large-scale phase III clinical trial of a γ-secretase inhibitor (semagacestat) in Alzheimer’s disease was halted because the drug worsened cognition and increased the risk of skin cancer (14). Mouse studies suggest that these adverse effects may be attributed to specific inhibition of γ-secretase rather than non-specific effects. The dementia and neurodegeneration caused by presenilin inactivation in the mouse brain predicted that γ-secretase inhibition might exacerbate the clinical features of Alzheimer’s disease (4). In addition, reduced γ-secretase and Notch1 activity in mice causes a high frequency of skin cancer, demonstrating that γ-secretase is a tumor-suppressor in skin (6–8). It remains to be seen whether the adverse effects of γ-secretase inhibitors include acne inversa.

The findings by Wang et al. should spur efforts to dissect the role of γ-secretase in acne inversa, and to examine patients with acne inversa and familial Alzheimer’s disease more closely for evidence of subtle overlap in the clinical features. Better understanding of the molecular mechanisms by which presenilin and γ-secretase dysfunction leads to these disparate conditions will also bolster efforts to devise safe and effective disease-modifying therapies.

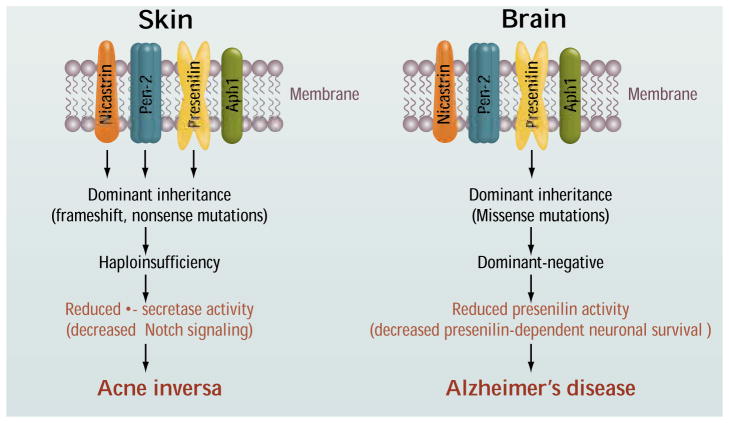

Figure 1. Mutations and mechanisms.

Dominant inactivating mutations in presenilin-1, nicastrin, and PEN2 cause acne inversa as a result of haploinsufficiency. Dominant missense mutations in presenilins-1 and -2 confer a loss of protein function and may cause Alzheimer’s disease through a dominant-negative mechanism.

References

- 1.Wang B, et al. Science. 2010;330:xxx. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shen J, Kelleher RJ., 3rd Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:403. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608332104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. Science. 2002;297:353. doi: 10.1126/science.1072994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saura CA, et al. Neuron. 2004;42:23. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00182-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Irizarry MC, et al. J Neurosci. 1997;17:7053. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-18-07053.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xia X, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:10863. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191284198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li T, et al. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:32264. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703649200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nicolas M, et al. Nat Genet. 2003;33:416. doi: 10.1038/ng1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Danby FW, Margesson LJ. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:779. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Song W, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:6959. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.6959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolfe MS. EMBO Rep. 2007;8:136. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heilig EA, Xia W, Shen J, Kelleher RJ., 3rd J Biol Chem. 2010;285:22350. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.116962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang C, et al. Nature. 2009;460:632. doi: 10.1038/nature08177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. [accessed on 10 October 2010.]; http://newsroom.lilly.com/releasedetail.cfm?releaseID=499794.