Abstract

Hypersensitivity to mosquito bites (HMB) is a cutaneous disorder belonging to the group of Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)-associated T/natural killer (NK)-cell lymphoproliferative diseases, and is primarily mediated by EBV-infected NK cells. It is characterized by intense local skin reactions accompanied by general symptoms after mosquito bites, and infiltration of EBV-infected NK cells into the bite sites. However, the mechanisms underlying these reactions have not been fully examined. We recently described the activation of circulating basophils by mosquito extracts in vitro in a patient with HMB. To further investigate this finding, we studied four additional patients with HMB. All patients showed typical clinical features of HMB after mosquito bites and they had NK lymphocytosis and high peripheral blood EBV DNA loads. We found evidence of EBV infection in NK cells through in situ hybridization that detected EBV-encoded small RNA-1, and flow cytometry showed HLA-DR expression on almost all NK cells. Basophil activation tests with the extracts of epidemic mosquitoes Culex pipiens pallens and Aedes albopictus showed positive responses to one or both extracts in all samples from patients with HMB, suggesting the presence of mosquito antigen-specific IgE and its binding to basophils. In particular, the extract of Aedes albopictus was able to activate basophils in all available patient samples. These results indicate that basophils and/or mast cells activated by mosquito bites may be involved in initiation and development of severe skin reactions to mosquito bites in HMB.

Keywords: Basophils, Epstein–Barr virus, hypersensitivity to mosquito bites, IgE, natural killer cells

More than 90% of humans are infected with the Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) and the infection persists for life.1 EBV mostly infects B cells in healthy persons who are often asymptomatic or may occasionally develop infectious mononucleosis (IM).2 It rarely infects T or natural killer (NK) cells in healthy children and young adults, and the chronic proliferation of those EBV-infected cells causes EBV-associated T/NK-cell lymphoproliferative diseases.3 EBV-associated T/NK-cell lymphoproliferative diseases present with diverse clinical and pathological findings, and were classified into the following disorders at the 2012 lymphoma workshop of the European Association for Haematopathology meeting: (i) chronic active EBV infection (CAEBV); (ii) systemic, malignant EBV-positive lymphoproliferative diseases; (iii) extranodal NK-cell/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type; and (iv) nodal T-cell/NK-cell lymphoma.4 CAEBV include the systemic type, hydroa vacciniforme and hypersensitivity to mosquito bites (HMB).

Hypersensitivity to mosquito bites is a cutaneous disorder characterized by intense local skin reactions manifesting as erythema, bullae, ulcers and scar formation accompanied by systemic symptoms, including high fever, lymphadenopathy, liver dysfunction and the hemophagocytic syndrome after mosquito bites.5 HMB has also been regarded as severe mosquito allergy, but such severe skin lesions and clonal proliferation of EBV-infected cells do not occur in simple allergy. The major cellular targets of latent EBV infection in HMB are NK cells, and NK cell lymphocytosis and high IgE levels are characteristic laboratory findings.6 The pathogenesis of HMB has not been well defined. The mosquito bite site in patients with HMB showed perivascular mononuclear cell infiltration with an increased number of EBV-infected NK cells and CD4+ T cells.7 In addition, it has been reported that CD4+ T cells from patients responded markedly to mosquito salivary gland extracts in vitro and that these CD4+ T cells stimulated by the mosquito antigen were able to induce reactivation of latent EBV infection and the proliferation of NK cells in vitro.5,8 Thus, CD4+ T cells and EBV-infected NK cells are considered to be involved in the pathogenesis of HMB. Nevertheless, our previous study demonstrated that there were not only T and NK cells but also many CD203c+ cells, representing basophils and/or mast cells, in the blister fluids from a patient with HMB.9 In addition, we found basophil activation with exposure to the extract of Aedes albopictus (Ae. albopictus) in the basophil activation test (BAT). These findings suggest the possible involvement of mosquito-specific IgE and CD203c+ cells in the severe skin reactions to mosquito bites in HMB.

Basophils and mast cells are similar in terms of expression of the high-affinity IgE receptor and the secretion of cytokines and inflammatory mediators upon stimulation.10 Therefore, in human studies, basophils have often been utilized as surrogates of tissue-resident mast cells in vitro because basophils are easily accessible in the peripheral blood, in contrast to mast cells.11,12 BAT is a flow cytometry-based test that measures basophil activation markers like CD63 and CD203c on the surface of basophils after in vitro stimulation with allergens. Because BAT has high sensitivity and specificity, it has been recently applied as an in vitro diagnostic method for various IgE-mediated allergic diseases.13

There are no studies apart from our previous study that examine basophils in patients with HMB. The present study aims to clarify the existence of mosquito antigen-specific IgE in HMB by using BAT and shows that in addition to mosquito antigen-specific CD4+ T cells and EBV-infected NK cells, basophils and/or mast cells activated by mosquito bites may be involved in the pathogenesis of HMB.

Materials and Methods

Patients

We evaluated five Japanese patients with HMB. All patients were previously healthy, and their family histories were unremarkable. Table1 presents the clinical and laboratory data of the patients. The data for P1 have been reported elsewhere.9 All but P5 were diagnosed and analyzed within 1 year after onset. P5 was referred to our hospital when he was 19 years old because of a change in his address, and he was analyzed at that time. All patients showed typical clinical features of HMB, such as intense local skin reactions accompanied by general symptoms including fever and abnormal liver function after mosquito bites. Serological tests for EBV showed modestly elevated titers of antiviral capsid antigen immunoglobulin G, positive anti-EBV nuclear antigen titers and the absence of antiviral capsid antigen immunoglobulin M, which indicated past infection in the studied patients. EBV DNA loads in the peripheral blood were markedly increased in all patients. None of the patients had an increase in basophil counts. Consistent with a previous report,6 all patients had elevated levels of serum IgE. Thus, all five patients were diagnosed with HMB according to the diagnostic guidelines.14 Serum mosquito-specific IgE measured by commercial fluorenzymeimmunoassay was negative in P1 and P3 (<0.34 UA/mL), and weakly positive in P2 (0.80 UA/mL). The remaining patients were not tested because no appropriate sample was available. Approval for the study was obtained from the Human Research Committee of Kanazawa University Graduate School of Medical Science, and written informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P5 | Normal range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at onset (years) | 7 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 1 | |

| Age at diagnosis | 7 | 8 | 9 | 11 | 4 | |

| Sex | M | M | M | F | M | |

| Skin findings | Swelling, blistering, necrosis | Swelling, blistering, necrosis | Swelling, blistering, necrosis, hemorrhage, scarring | Swelling, necrosis | Swelling, ulcer | |

| Systemic symptoms | Fever, liver damage | Fever | Fever, liver damage | Fever, liver damage | Fever, liver damage | |

| EBV VCA IgG (fold) | 80 | 80 | 40 | 640 | NA | <10 |

| EBV VCA IgM (fold) | <10 | <10 | NA | <10 | NA | <10 |

| EBNA (fold) | 40 | 20 | 80 | 10 | NA | <10 |

| EBV DNA loads (copies/106 WBC) | 1 300 000 | 66 000 | 28 000 | 21 000 | 37 300† | <20 |

| Lymphocyte subsets (%) | ||||||

| CD3+ T cells | 26.2 | 47.5 | 15.2 | 42.7 | 44.8 | 69.5 ± 4.6 |

| CD4+ T cells | 17.4 | 25.9 | 8.5 | 29.4 | 34.8 | 43.1 ± 6.0 |

| CD8+ T cells | 7.4 | 19.2 | 6.6 | 11.4 | 9.8 | 22.0 ± 5.4 |

| CD20+ B cells | 5.6 | 17.9 | 14.1 | 7.1 | 12.4 | 11.2 ± 3.5 |

| CD56+ NK cells | 55.6 | 33.8 | 59.7 | 33.5 | 28.7 | 12.8 ± 5.3 |

| CD203c+ basophils | 0.28 | 0.68 | 0.16 | 1.10 | NA | 0.53 ± 0.28 |

| Total IgE (IU/mL) | 1338 | 3480 | 10 020 | 3177 | 8910 | <696 |

It was expressed as copies/μg DNA in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. EBNA, Epstein–Barr virus nuclear antigen; EBV, Epstein–Barr virus; NA, not applicable; VCA, viral capsid antigen; WBC, white blood cells.

Cell preparation and in situ hybridization for Epstein–Barr virus-encoded small RNA-1

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated by Ficoll–Hypaque gradient centrifugation. Peripheral blood lymphocytes were prepared from PBMC by depletion of monocytes using anti-CD14 monoclonal antibody (mAb)-coated magnetic beads (Becton Dickinson San Diego, CA, USA). CD4+ T, CD8+ T, CD19+ B and CD56+ NK cells were then purified by positive selection from peripheral blood lymphocytes using the respective mAb-coated magnetic beads (Becton Dickinson). With P5, CD16+ NK cells were purified by positive selection using phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-CD16 mAb and anti-PE-conjugated magnetic beads (Becton Dickinson). B cells were prepared by removal of CD4+, CD8+ and CD16+ cells. The purity of cells from P1 has been reported elsewhere.9 The purity of the isolated CD4+ T, CD8+ T, CD19+ B and CD56+ NK cells from P2 was 95.8%, 93.6%, 99.6% and 96.3%, respectively, as determined by flow cytometric analysis. Separation of lymphocyte subsets from P3 could not be done because of limited sample availability. The purity of the isolated CD4+ T, CD8+ T, CD19+ B and CD56+ NK cells from P4 was 98.4%, 97.9%, 80.7% and 93.2%, respectively. The purity of the isolated CD4+ T, CD8+ T, CD20+ B and CD16+ NK cells from P5 was 98.9%, 86.0%, 58.5% and 76.9%, respectively. Because of the negative selection, isolated B cells exhibited low purity and comprised 28.6% of the contaminating CD56+ NK cells from P5. In situ hybridization for EBV-encoded small RNA-1 (EBER-1) was performed as described previously.15

Flow cytometric analysis

For the analysis, whole blood samples were used within 24 h after collection. None of the patients were receiving any treatment at the time of sample collection. The distribution of lymphocyte subsets was analyzed using FACSCalibur flow cytometer using CellQuest software (BD Bioscience, Tokyo, Japan). HLA-DR was the activation marker that was evaluated on CD3+ T cells and CD16+ or CD56+ NK cells. A total of 12 healthy subjects and 4 volunteers with simple mosquito allergies were also studied as controls. Simple mosquito allergy was defined as large local reactions but not systemic reactions after mosquito bites.16 Those with simple mosquito allergies were excluded from the group of healthy controls. The following mAb were used: FITC-conjugated anti-HLA-DR, and PE-conjugated anti-CD3 or anti-CD56 (Becton Dickinson PharMingen, San Diego, CA, USA); PE-conjugated anti-CD4, anti-CD8 or anti-CD20 (DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark); and PE-conjugated anti-CD16 (Immunotech, Marseille, France). Analysis of differences among the data groups was performed using Student’s t-test for unpaired samples. P-values < 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

Mosquito extracts and basophil activation test

We prepared mosquito extracts and performed BAT using blood samples from five patients with HMB, 12 healthy controls and five volunteers with simple mosquito allergy as described previously.9 Two mosquito species, Culex pipiens pallens (C. p. pallens) and Ae. Albopictus, which are endemic in Japan, were used (Sumika Technoservice, Takarazuka, Hyogo, Japan). Mosquito extracts were composed of whole bodies. A total of 100 mosquitoes were homogenized in 2 mL of phosphate-buffered saline, and the samples were centrifuged at 3000 g for 10 min. The supernatants were then centrifuged at 14 000 g for 10 min. The mosquito extracts were stored at −80°C until use. The total protein concentrations of the extracts of C. p. pallens and Ae. albopictus were 7.0 and 6.6 mg/mL, respectively, as assessed by BCA protein assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA).17 For BAT,18 peripheral whole blood was obtained, washed twice in PBS and suspended in RPMI1640 medium (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) containing 10% FBS and antibiotics. Aliquots (200 μL) were incubated with or without 10−1 or 10−2 dilutions of the mosquito extracts at 37°C for 40 min. Cells were then washed and incubated with FITC-conjugated anti-CD63 and PE-conjugated anti-CD203c mAbs (Immunotech) on ice in the dark for 20 min. Stained cells were analyzed in a FACSCalibur flow cytometer and basophils were detected on the basis of forward side scatter characteristics and expression of CD203c. Results of activated basophils were given as the percentage of basophils expressing CD63 among the total number of identified basophils and CD203c expression was evaluated by the mean fluorescence intensity. Analysis of differences among the data groups was performed using Student’s t-test for unpaired samples. P-values < 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Cellular target of Epstein–Barr virus in hypersensitivity to mosquito bites

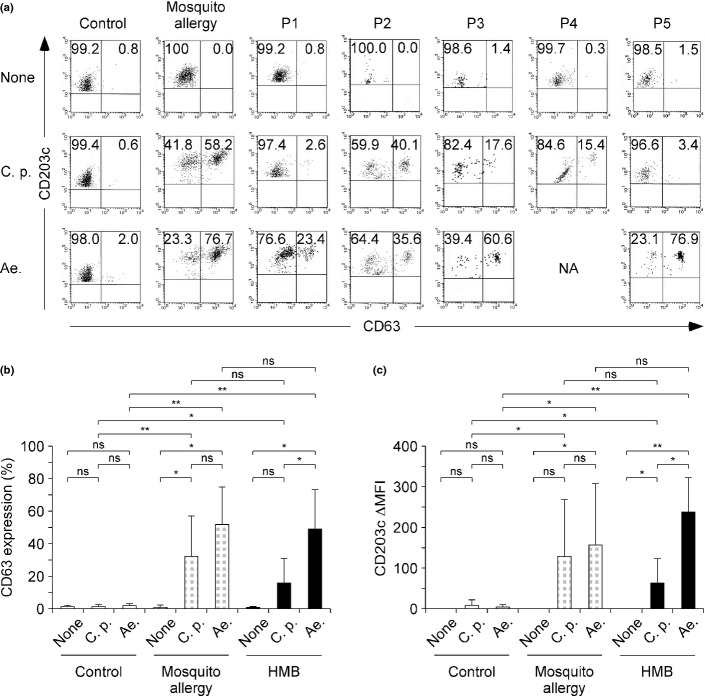

To determine which populations of lymphocytes were infected with EBV, we performed in situ hybridization to identify EBER-1 in each lymphocyte subpopulation that had been isolated from patients with HMB. Figure1(a) shows representative pictures of in situ hybridization for EBER-1 where P1 had a number of EBER-1-positive cells among CD56+ NK cells, in contrast to EBER-1 positivity in CD4+, CD8+ T and CD19+ B cells. Figure1(b) shows the percentages of EBER-1-positive cells in the population of PBMC and isolated lymphocyte subpopulations. The average (± standard deviation) percentage of EBER-1-positive cells among PBMC was 25.0 ± 11.4%. In the isolated cell subpopulations of four patients, the dominant population of EBER-1-positive cells was CD56+ NK cells (61.8 ± 14.1%). Very few T and B cells were positive for EBER-1 in these patients. In spite of the low purity of B cells in P5, the percentage of EBER-1-positive cells was 1.7%.

Figure 1.

Cellular target of Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) infection. (a) EBV-encoded small RNA-1 (EBER-1) in situ hybridization of the lymphocyte subpopulations in a representative patient with hypersensitivity to mosquito bites. (b) The percentages of EBER-1-positive cells in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) and the lymphocyte subpopulations of patients with hypersensitivity to mosquito bites are shown.

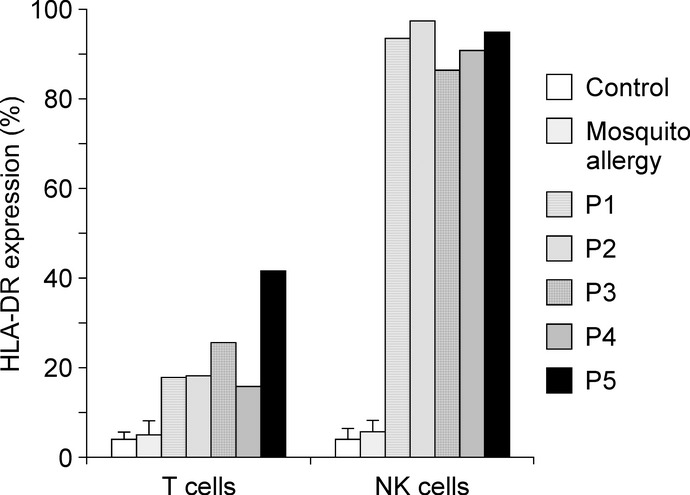

Increased subpopulation of activated NK cells

Consistent with the findings of a previous report,19 the number of CD56+ NK cells was increased in all patients (Table1) but not for those with simple mosquito allergy (11.1 ± 2.7%). As shown in Figure2, the majority of these NK cells expressed HLA-DR (92.6 ± 4.2%), whereas a small number of NK cells in controls and simple mosquito allergy patients expressed HLA-DR (4.0 ± 2.5%, 5.7 ± 2.6%, respectively). The NK lymphocytosis likely caused a relative decrease in the percentage of T cells. Although some T cells expressed HLA-DR (23.8 ± 10.6%), the CD4/8 ratios were normal in patients with HMB. Our data showed that NK cells had significantly more HLA-DR expression than T cells in the group with HMB (P < 0.001).

Figure 2.

Expression of HLA-DR on T and natural killer (NK) cells. The percentages of HLA-DR+ cells among CD3+ T and CD56+ NK cells in the peripheral blood of healthy controls (n = 12), simple mosquito allergy patients (n = 4) and patients with hypersensitivity to mosquito bites are shown. Error bars indicate standard deviation.

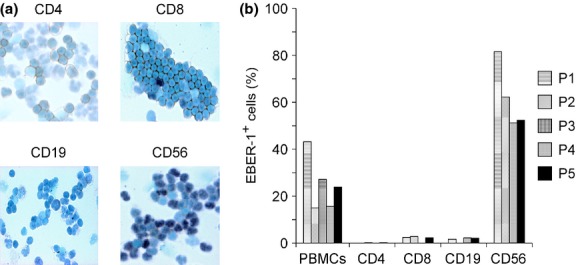

Basophil activation test experiments

As shown in Figure3(a), basophil activation occurred with exposure to the extracts of epidemic mosquitoes in all samples from patients with HMB, but no activation occurred in the absence of stimulation. Basophils from normal controls were not activated by mosquito antigens. When we examined in detail basophil activation on exposure to the respective antigens in samples from patients with HMB, we detected basophil activation on exposure to the extract of Ae. Albopictus, except in P4. Basophils from P2, P3 and P4 were activated by the extract of C. p. pallens. Both the extracts activated basophils in P2 and P3.

Figure 3.

Results of basophil activation tests. (a) Expression of CD63 and CD203c on basophils stimulated in vitro by the antigens of Culex pipiens pallens (C. p.) or Aedes albopictus (Ae.) from representative individuals of normal control or simple mosquito allergy and patients with hypersensitivity to mosquito bites (HMB). The percentage of cells gated in each region is shown. (b) The percentages of CD63+ cells within the population of basophils stimulated by the antigens of Culex pipiens pallens or Aedes albopictus in the healthy control group (n = 12), simple mosquito allergy (n = 5) and HMB group (n = 5 or 4, respectively). (c) The difference in mean fluorescence intensity (ΔMFI) of CD203c on basophils. ΔMFI of CD203c was calculated by subtracting the MFI of unstimulated cells from those of stimulated cells. Error bars indicate standard deviation of mean. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.001 based on Student’s t-test. NA, not applicable; ns, not significant.

When we compared the extent of CD63 and CD203c expression between the HMB group and the healthy control group, the HMB group showed a significantly higher percentage of CD63+ basophils that were stimulated by the extracts of C. p. pallens or Ae. Albopictus (P < 0.05 and P < 0.001, respectively) (Fig.3b). Furthermore, both C. p. pallens and Ae. Albopictus significantly upregulated CD203c expression in the HMB group more than the control group (P < 0.05 and P < 0.001, respectively) (Fig.3c). In the HMB group, there were significantly more basophils that upregulated CD63 and CD203c expression after exposure to Ae. Albopictus compared with C. p. pallens (P < 0.05 and P < 0.05, respectively) (Fig.3b,c). Similar to HMB, basophil activation by mosquito extracts was detected in all samples from simple mosquito allergy patients.

Discussion

We demonstrated basophil activation by mosquito antigens in HMB. In particular, the extract of Ae. albopictus was able to activate basophils in all available patient samples. Ae. albopictus has been known to have a larger variety and amount of allergens in the saliva compared with other species of mosquitoes.20 Furthermore, Ae. albopictus is the most common species associated with systemic allergic reactions to mosquito bites.21 In fact, the antigen of Ae. albopictus tended to induce more basophil activation than C. p. pallens in our patients with HMB. However, it remains unclear whether the antigen of Ae. albopictus causes more intense clinical symptoms in patients with HMB. In contrast, the extract of C. p. pallens activated basophils from three patients with HMB, two of whom showed basophil activation after exposure to either extract. These different profiles of response to the mosquito antigens may simply reflect the frequency of exposure to bites of each species. Because the saliva of Ae. Albopictus contains allergens that are common among different species, it is possible that basophil activation by C. p. pallens is the consequence of the cross-reactivity of such allergens.21

Studies of T cells from patients with HMB show that mosquito antigens activate and induce proliferation of CD4+ T cells and that these mosquito antigen-specific T cells induce EBV reactivation in NK cells.5,8 It is well known that significant numbers of EBV-infected NK cells and reactive T cells infiltrate into the bite sites in HMB.7 Therefore, mosquito antigen-specific CD4+ T and EBV-infected NK cells have been considered to be responsible for intense skin lesions as well as systemic symptoms in HMB. In the present study, we demonstrated the presence of mosquito-specific IgE and basophil activation by mosquito antigens in vitro. The discrepancy regarding mosquito-specific IgE between the BAT data and the commercial fluorenzymeimmunoassay may be due to the different sensitivity of each method used for assessing mosquito-specific IgE. It seems reasonable that mosquito antigens can bind to mosquito-specific IgE attached to the high-affinity IgE receptor of basophils and/or mast cells at the bite sites, resulting in activation of such cells in HMB. In two patients whose basophils were evaluated after successful hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, basophil activation by mosquito antigens was no longer detected in vitro (data not shown). Indeed, these post-stem cell transplantation patients have had no symptoms after mosquito bites.

Immediate allergic skin reactions via IgE-dependent mechanisms soon after mosquito bites are also seen in simple mosquito allergy.22 In fact, we demonstrated basophil activation by mosquito antigens in all samples from simple mosquito allergy patients. Subsequent bite-induced indurations in simple mosquito allergy correlate with T-cell proliferation responses to mosquito antigens. However, unlike simple mosquito allergy, patients with HMB exhibit severe skin reactions and systemic symptoms that might be the result of activation of mosquito-specific CD4+ T cells and EBV-infected NK cells. Basophils and/or mast cells activated by the mosquito antigens may produce humoral factors such as cytokines that potentially activate CD4+ T cells and NK cells at the reaction sites. In fact, activated basophils have been reported to produce various cytokines, including IL-4, IL-9 and IL-13.23,24 IL-4 is known to induce proliferation of T cells, differentiation of naïve CD4+ T cells into Th2 cells and a class switch to IgE in B cells.25–27 IL-13 can also promote a class switch to IgE in B cells in vitro.28 IL-9 has been showed to increases the number of EBV-infected NK cell lines of nasal NK/T lymphoma in vitro.29 An analysis of serum cytokines from patients with HMB showed high levels of IL-13, which might explain the high serum IgE levels.30 Further analysis of these cytokines in serum or local skin lesions is needed to reveal the inflammatory processes in HMB. Taken together, these findings suggest that antigen-induced activation of basophils and/or mast cells that bind to mosquito-specific IgE could be the initial event and an additional mechanism leading to severe local skin reactions and systemic symptoms in HMB.

Our immunological analysis clearly demonstrated prominent EBV infection in NK cells, the proliferation of NK cells and HLA-DR expression on almost all NK cells in HMB. Normal NK cells do not usually express HLA-DR.31,32 Consistent with our previous study,9 the percentage of activated NK cells expressing HLA-DR was much higher than that of EBV-infected NK cells in all patients with HMB. The reason why the majority of non-infected NK cells expressed HLA-DR is unclear. In contrast to NK cells, the minority of T cells expressed HLA-DR in our patients. These findings differ from those of IM, in which many T cells express HLA-DR.33 The difference in HLA-DR expression on T cells between HMB and IM may be due to the types of antigens of EBV-infected cells. EBV-infected B cells in IM express all EBV latent proteins, whereas EBV-infected T/NK cells in CAEBV do not express EBNA-3 family proteins that are dominant in cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) responses.34,35 The absence of these antigens is thought to impair CTL recognition of infected cells in CAEBV. Thus, a low percentage of activated T cells in HMB may be associated with markedly reduced CTL activity.36

From the clinical perspective, our results suggest an auxiliary method for the diagnosis of HMB. Although the proposed guidelines have been shown to be helpful for the diagnosis of HMB, the analysis of EBV viral load, clonality and cellular target of EBV is only available in specialized laboratories. We demonstrated that the existence of mosquito antigen-specific IgE by BAT and selective activation and expansion of NK cells, both of which reflect the pathogenesis of HMB, were important features in HMB. These findings may help in the diagnosis of HMB, although each isolated finding might not be specific. Mosquito antigen-specific IgE has already been reported in patients with simple mosquito allergy.22 Similarly, an increased subpopulation of HLA-DR+ NK cells has been found in patients with infections caused by herpes simplex virus, dengue virus and Mycobacterium tuberculosis, as well as aggressive NK cell leukemia.37–40 However, concurrent assessment of basophil activation by mosquito extracts and NK cells might provide clues that lead to the diagnosis of HMB. Further studies on whether this auxiliary method is useful as a screening test of HMB are needed.

Limitations of the present study include the small sample size, the ethnically homogeneous sample, and the absence of patients with other forms of EBV infection. It has been reported that the symptoms of HMB also occur in patients with T-cell type CAEBV or NK cell leukemia/lymphoma.3,41 Further evaluation of patients with various types of EBV infection or patients with a different ethnic background is necessary. It is also necessary to assess whether mosquito-specific IgE is present in cases of EBV-associated T/NK-cell lymphoproliferative diseases without HMB. In addition, we used whole body extracts that were easy to prepare. However, this might not be ideal because they contained many extraneous proteins that were not present in mosquito saliva.42 Although saliva from living mosquitoes would be the best source of antigens, it is technically difficult and time-consuming to obtain large enough quantities of saliva.21,42 It has been reported that recombinant Aedes aegypti salivary antigens can be used in the in vitro and in vivo diagnosis of mosquito allergy and are more sensitive than whole body extracts.43,44 These antigens may increase the sensitivity and specificity of BAT.

In conclusion, our study demonstrated the activation of circulating basophils by mosquito extracts in vitro and suggested the involvement of activated basophils and/or mast cells carrying mosquito-specific IgE on their cell membranes in the initiation and development of severe skin reactions to mosquito bites in HMB.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan; and a Grant from the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare of Japan, Tokyo.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- Cohen JI, Kimura H, Nakamura S, Ko YH, Jaffe ES. Epstein–Barr virus-associated lymphoproliferative disease in non-immunocompromised hosts: a status report and summary of an international meeting, 8–9 September 2008. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1472–82. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus SE, Cohen JI, Tosato G, Meier J. NIH conference. Epstein–Barr virus infections: biology, pathogenesis, and management. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118:45–58. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-1-199301010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura H, Ito Y, Kawabe S, et al. EBV-associated T/NK-cell lymphoproliferative diseases in nonimmunocompromised hosts: prospective analysis of 108 cases. Blood. 2012;119:673–86. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-10-381921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attygalle AD, Cabecadas J, Gaulard P, et al. Peripheral T-cell and NK-cell lymphomas and their mimics; taking a step forward – report on the lymphoma workshop of the XVIth meeting of the European Association for Haematopathology and the Society for Hematopathology. Histopathology. 2014;64:171–99. doi: 10.1111/his.12251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asada H, Miyagawa S, Sumikawa Y, et al. CD4+ T-lymphocyte-induced Epstein–Barr virus reactivation in a patient with severe hypersensitivity to mosquito bites and Epstein–Barr virus-infected NK cell lymphocytosis. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:1601–7. doi: 10.1001/archderm.139.12.1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura H, Hoshino Y, Kanegane H, et al. Clinical and virologic characteristics of chronic active Epstein–Barr virus infection. Blood. 2001;98:280–6. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.2.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S, Ko YH. Epstein–Barr virus-associated T/natural killer-cell lymphoproliferative disorders. J Dermatol. 2014;41:29–39. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.12322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asada H, Saito-Katsuragi M, Niizeki H, et al. Mosquito salivary gland extracts induce EBV-infected NK cell oncogenesis via CD4 T cells in patients with hypersensitivity to mosquito bites. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125:956–61. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada T, Yokoyama T, Nakagawa H, et al. Flow cytometric analysis of skin blister fluid induced by mosquito bites in a patient with chronic active Epstein–Barr virus infection. Int J Hematol. 2009;90:611–5. doi: 10.1007/s12185-009-0442-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGowan EC, Saini S. Update on the performance and application of basophil activation tests. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2013;13:101–9. doi: 10.1007/s11882-012-0324-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karasuyama H, Mukai K, Tsujimura Y, Obata K. Newly discovered roles for basophils: a neglected minority gains new respect. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:9–13. doi: 10.1038/nri2458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausmann OV, Gentinetta T, Bridts CH, Ebo DG. The basophil activation test in immediate-type drug allergy. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2009;29:555–66. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2009.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturm GJ, Bohm E, Trummer M, Weiglhofer I, Heinemann A, Aberer W. The CD63 basophil activation test in Hymenoptera venom allergy: a prospective study. Allergy. 2004;59:1110–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2004.00400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okano M, Kawa K, Kimura H, et al. Proposed guidelines for diagnosing chronic active Epstein–Barr virus infection. Am J Hematol. 2005;80:64–9. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasahara Y, Yachie A, Takei K, et al. Differential cellular targets of Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) infection between acute EBV-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and chronic active EBV infection. Blood. 2001;98:1882–8. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.6.1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Z, Simons FE. Advances in mosquito allergy. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;7:350–4. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e328259c313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada T, Schurman SH, Otsu M, et al. Somatic mosaicism in Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome suggests in vivo reversion by a DNA slippage mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:8697–702. doi: 10.1073/pnas.151260498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauswirth AW, Natter S, Ghannadan M, et al. Recombinant allergens promote expression of CD203c on basophils in sensitized individuals. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;110:102–9. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.125257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokura Y, Tamura Y, Takigawa M, et al. Severe hypersensitivity to mosquito bites associated with natural killer cell lymphocytosis. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:362–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Z, Li H, Simons FE. Immunoblot analysis of salivary allergens in 10 mosquito species with worldwide distribution and the human IgE responses to these allergens. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998;101:498–505. doi: 10.1016/S0091-6749(98)70357-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Z, Beckett AN, Engler RJ, Hoffman DR, Ott NL, Simons FE. Immune responses to mosquito saliva in 14 individuals with acute systemic allergic reactions to mosquito bites. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:1189–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Z, Yang M, Simons FE. Immunologic mechanisms in mosquito allergy: correlation of skin reactions with specific IgE and IgG antibodies and lymphocyte proliferation response to mosquito antigens. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1996;77:238–44. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)63262-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider E, Thieblemont N, De Moraes ML, Dy M. Basophils: new players in the cytokine network. Eur Cytokine Netw. 2010;21:142–53. doi: 10.1684/ecn.2010.0197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blom L, Poulsen BC, Jensen BM, Hansen A, Poulsen LK. IL-33 induces IL-9 production in human CD4+ T cells and basophils. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21695. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagihara Y, Kajiwara K, Basaki Y, et al. Cultured basophils but not cultured mast cells induce human IgE synthesis in B cells after immunologic stimulation. Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;111:136–43. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00474.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu-Li J, Shevach EM, Mizuguchi J, Ohara J, Mosmann T, Paul WE. B cell stimulatory factor 1 (interleukin 4) is a potent costimulant for normal resting T lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1987;165:157–72. doi: 10.1084/jem.165.1.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J, Guo L, Min B, et al. Growth factor independent-1 induced by IL-4 regulates Th2 cell proliferation. Immunity. 2002;16:733–44. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00317-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Punnonen J, Aversa G, Cocks BG, et al. Interleukin 13 induces interleukin 4-independent IgG4 and IgE synthesis and CD23 expression by human B cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:3730–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagato T, Kobayashi H, Kishibe K, et al. Expression of interleukin-9 in nasal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma cell lines and patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:8250–7. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura H, Hoshino Y, Hara S, et al. Differences between T cell-type and natural killer cell-type chronic active Epstein–Barr virus infection. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:531–9. doi: 10.1086/427239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima M, Almeida J, dos Anjos Teixeira M, Queiros ML, Justica B, Orfao A. The “ex vivo” patterns of CD2/CD7, CD57/CD11c, CD38/CD11b, CD45RA/CD45RO, and CD11a/HLA-DR expression identify acute/early and chronic/late NK-cell activation states. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2002;28:181–90. doi: 10.1006/bcmd.2002.0506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo N, Tokura Y, Ishihara S, Takeoka Y, Tagawa S, Takigawa M. Disordered expression of inhibitory receptors on the NK1-type natural killer (NK) leukaemic cells from patients with hypersensitivity to mosquito bites. Clin Exp Immunol. 2000;120:413–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2000.01253.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomkinson BE, Wagner DK, Nelson DL, Sullivan JL. Activated lymphocytes during acute Epstein–Barr virus infection. J Immunol. 1987;139:3802–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callan MF. The immune response to Epstein–Barr virus. Microbes Infect. 2004;6:937–45. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2004.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray RJ, Kurilla MG, Brooks JM, et al. Identification of target antigens for the human cytotoxic T cell response to Epstein–Barr virus (EBV): implications for the immune control of EBV-positive malignancies. J Exp Med. 1992;176:157–68. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.1.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugaya N, Kimura H, Hara S, et al. Quantitative analysis of Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)-specific CD8+ T cells in patients with chronic active EBV infection. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:985–8. doi: 10.1086/423285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M, Osborne NR, Zeng W, et al. Herpes simplex virus antigens directly activate NK cells via TLR2, thus facilitating their presentation to CD4 T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2012;188:4158–70. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azeredo EL, De Oliveira-Pinto LM, Zagne SM, Cerqueira DI, Nogueira RM, Kubelka CF. NK cells, displaying early activation, cytotoxicity and adhesion molecules, are associated with mild dengue disease. Clin Exp Immunol. 2006;143:345–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.02996.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokkali S, Das SD, Selvaraj A. Differential upregulation of chemokine receptors on CD56 NK cells and their transmigration to the site of infection in tuberculous pleurisy. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2009;55:352–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2008.00520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki R, Suzumiya J, Nakamura S, et al. Aggressive natural killer-cell leukemia revisited: large granular lymphocyte leukemia of cytotoxic NK cells. Leukemia. 2004;18:763–70. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokura Y, Ishihara S, Tagawa S, Seo N, Ohshima K, Takigawa M. Hypersensitivity to mosquito bites as the primary clinical manifestation of a juvenile type of Epstein–Barr virus-associated natural killer cell leukemia/lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:569–78. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.114751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wongkamchai S, Khongtak P, Leemingsawat S, et al. Comparative identification of protein profiles and major allergens of saliva, salivary gland and whole body extracts of mosquito species in Thailand. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2010;28:162–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Z, Xu W, Lam H, Cheng L, James AA, Simons FE. A new recombinant mosquito salivary allergen, rAed a 2: allergenicity, clinical relevance, and cross-reactivity. Allergy. 2006;61:485–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2006.00985.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Z, Xu W, James AA, et al. Expression, purification, characterization and clinical relevance of rAed a 1 – a 68-kDa recombinant mosquito Aedes aegypti salivary allergen. Int Immunol. 2001;13:1445–52. doi: 10.1093/intimm/13.12.1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]