Abstract Abstract

In heart failure with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (HFrEF), adrenergic activation is a key compensatory mechanism that is a major contributor to progressive ventricular remodeling and worsening of heart failure. Targeting the increased adrenergic activation with β-adrenergic receptor blocking agents has led to the development of arguably the single most effective drug therapy for HFrEF. The pressure-overloaded and ultimately remodeled/failing right ventricle (RV) in pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is also adrenergically activated, which raises the issue of whether an antiadrenergic strategy could be effectively employed in this setting. Anecdotal experience suggests that it will be challenging to administer an antiadrenergic treatment such as a β-blocking agent to patients with established moderate-severe PAH. However, the same types of data and commentary were prevalent early in the development of β-blockade for HFrEF treatment. In addition, in HFrEF approaches have been developed for delivering β-blocker therapy to patients who have extremely advanced heart failure, and these general principles could be applied to RV failure in PAH. This review examines the role played by adrenergic activation in the RV faced with PAH, contrasts PAH-RV remodeling with left ventricle remodeling in settings of sustained increases in afterload, and suggests a possible approach for safely delivering an antiadrenergic treatment to patients with RV dysfunction due to moderate-severe PAH.

Keywords: right ventricle, adrenergic mechanisms, β-adrenergic receptors, β-blockers, pulmonary arterial hypertension

Much progress has been made in targeting the pulmonary circulation in pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH).1-5 Some of these effective approaches, such as endothelin antagonists2,3 and phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors,4,5 may also produce favorable effects on right ventricle (RV) remodeling. However, these effects have been difficult to document, and the primary mode of action appears to be on the pulmonary circulation.6

It is generally believed that the failing RV needs more attention in therapeutic targeting in PAH.7,8 Assuming this reasoning is valid, what are some viable approaches to primary targeting of the RV in PAH?

In heart failure with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (HFrEF), adrenergic activation is a key compensatory mechanism that is a major contributor to progressive ventricular remodeling and worsening of heart failure.9-11 Most importantly, targeting the increased adrenergic activation with β-adrenergic receptor blocking agents has led to the development of arguably the single most effective drug therapy in HFrEF.11

The pressure-overloaded and ultimately remodeled/failing RV in PAH is also adrenergically activated,12,13 which raises the issue of whether an antiadrenergic strategy could be effectively employed in this setting. This review will state the case for an antiadrenergic approach to preventing or reversing RV dysfunction in PAH and will provide some thoughts on how such a treatment could be safely and effectively delivered.

Adrenergic mechanisms in heart failure from left or biventricular dysfunction

There is an extensive body of work spanning >50 years on the role played by the adrenergic nervous system in heart failure.11 Following any type of myocardial damage, adrenergic activation instantaneously occurs and is the major means of delivering an increase in heart rate and contractility, two of the four compensatory mechanisms available for stabilizing cardiac function (Fig. 1).14,15 Movement of ventricular chambers to a higher position on the Frank-Starling curve takes hours to days, and producing more contractile elements via hypertrophy has a time frame of days to weeks.

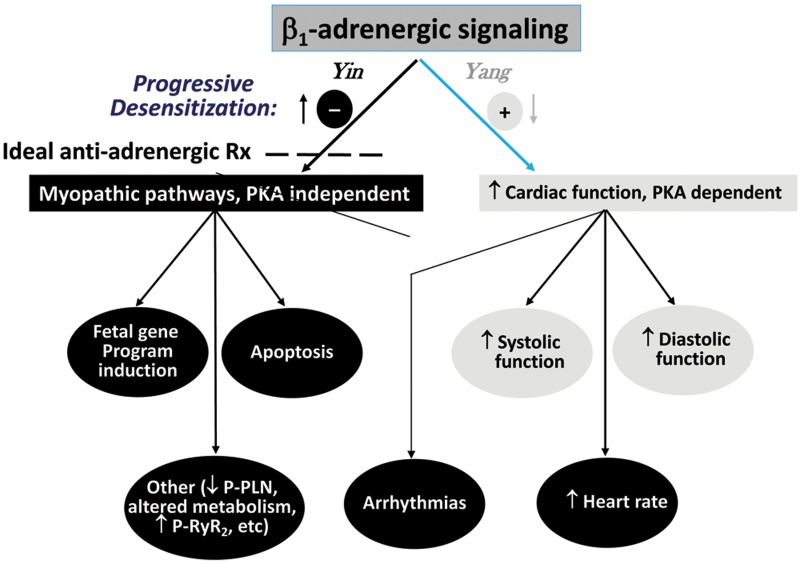

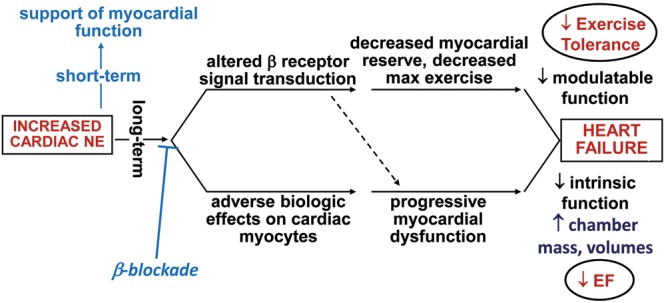

Figure 1.

Role played by compensatory mechanisms in initially supporting/stabilizing cardiac function after a myocardial insult myocardium, then producing secondary myocardial damage to intrinsic function in the form of remodeling as well as attenuation of modulatable function (adapted from Bristow and Gilbert15). RAAS: renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system.

When considering global myocardial function and patterns of dysfunction, it is useful to subdivide into intrinsic and modulatable categories (Fig. 1).15 Intrinsic function refers to the myocardial components responsible for systolic and diastolic function in the basal or resting state, while modulatable function encompasses those mechanisms responsible for increasing cardiac function in response to stress and an increased workload. In the most common form of heart failure, HFrEF, both types of function are easily detected with widely available clinical tests. Intrinsic ventricular chamber function is typically measured by the ejection fraction, a quantitative chamber volume imaging calculation that has the systolic function index stroke volume as the numerator in the equation (stroke volume/end-diastolic volume), while modulatable function is measured with an exercise test. Activation of compensatory mechanisms supports intrinsic function for a period of time but also produces secondary damage in the form of progressive pathological ventricular chamber remodeling.10,14 After a few days, modulatable function, mostly delivered by increased β-adrenergic signaling, is attenuated by the multiple types of desensitization changes that affect receptors and G proteins.11 Hence, the compensatory mechanisms evoked to temporally stabilize a damaged/failing heart are ineffective long term, and we have learned that inhibiting them in certain ways generally results in improved outcomes.

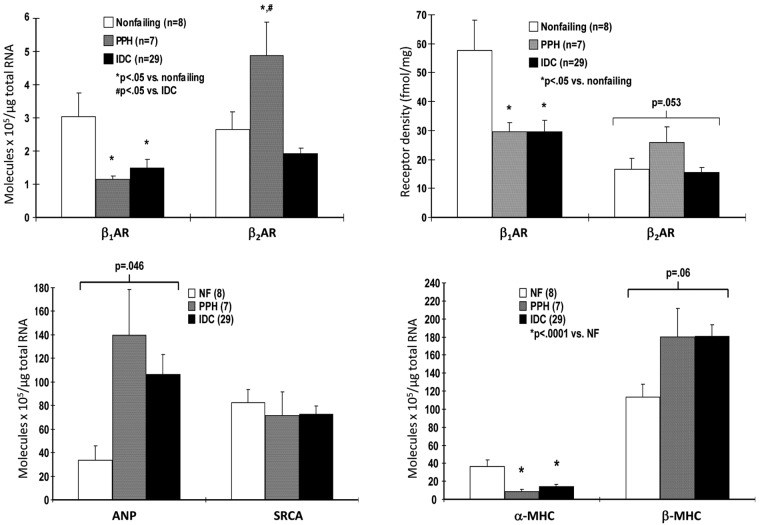

Adrenergic activation is important in all three types of compensatory mechanisms listed in Figure 1. It contributes to volume expansion through β1-adrenergic receptor (β1-AR) activation of the renin-angiotensin system via renin release,16 to subsequent angiotensin II–mediated vasopressin release,17 and to hypertrophy through both α1-AR18 and β1-AR19 direct effects on contractile proteins, and through β1-receptor stimulation it is the major means of increasing heart rate and contractile function. In HFrEF as opposed to physiological stress, such as from exercise, adrenergic activation is sustained, at levels high enough to produce desensitization to β-AR signaling through protein kinase A (PKA)–dependent signaling pathways while also maintaining or actually increasing heightened signaling through biologically adverse PKA-independent signaling (Fig. 2).11 The results are adverse effects on intrinsic myocardial function from progressive chamber remodeling and attenuation of modulatable function via β-AR desensitization phenomena (Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

β1-adrenergic receptor (β1-AR) signaling pathways can generally be divided into those that are protein kinase A (PKA) dependent and those that are independent. In the failing human heart, the benefit (“yang”) of supporting cardiac function mostly derives from PKA-dependent pathways, which undergo desensitization in response to increased adrenergic drive. In contrast, PKA-independent pathways, as illustrated by Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II signaling,19 upregulate with β-adrenergic desensitization changes and produce adverse biologic effects, including fetal gene program induction and apoptosis.11 The ideal antiadrenergic therapy would selectively inhibit PKA-independent pathways or enhance PKA-dependent signaling beyond the level of β1-AR blockade that inhibits both types of signaling. P-PLN: phosphorylated phospholamban; P-RyR2: phosphorylated ryanodine receptor 2.

Figure 3.

Adverse effects of the compensatory mechanism effector–increased adrenergic drive. Both modulatable (upper-pathway) and intrinsic (lower-pathway) functions are adversely affected by sustained β-adrenergic activation (adapted from Bristow and Gilbert15). NE: norepinephrine; EF: ejection fraction.

Given these realities and the large therapeutic effects of β-blocker therapy in chronic HFrEF,11 it is logical to consider RV dysfunction and remodeling from PAH to be a candidate for an antiadrenergic intervention.

Similarities and differences between RV and left ventricle (LV) remodeling in PAH/RV failure (RVF) and HFrEF

There are marked differences between the RV and the LV that include embryologic origin, shape, structure, and circulatory environment.8,20 Therefore, it is not a given that the RV would behave phenotypically the same as the LV in response to myocardial damage, that RV and LV adrenergic mechanisms are similar and similarly activated compensatorially, or that once the RV is remodeled, an antiadrenergic treatment would be able to reverse remodeling.

Table 1 gives magnetic resonance imaging data for the RV in PAH, using methods described elsewhere.21 Of 18 patients with mean pulmonary arterial pressures ranging from 51 to 78 mmHg, 4 (21%) had compensated concentric hypertrophy (increased RV mass, no increase in end-diastolic volume, increased RV free wall thickness, RV ejection fraction [RVEF] of ≥0.40), 7 (37%) had concentric hypertrophy with myocardial failure (concentric hypertrophy with RVEF of <0.40), 2 (11%) had compensated eccentric hypertrophy (increased mass, increased trend toward increased end-diastolic volume, no increased free wall thickness, RVEF of ≥0.40), 3 (16%) had eccentric hypertrophy with failure (RVEF of <0.40), and 2 (11%) had concentric remodeling and failure (RVEF of <0.40, no increase in RV mass). This is a truly diverse array of structural phenotypes, reminiscent of what is observed in LV hypertrophy due to either systemic hypertension22,23 or aortic stenosis.24 To compare data from these multiple studies, in Figure 4 the RV data from Table 1 and the LV hypertrophy structural phenotype data22-24 are reclassified into concentric hypertrophy (increased wall thickness and mass, no increase in end-diastolic volume), eccentric hypertrophy (increased diastolic volume and mass, no increase in wall thickness), and concentric remodeling (increased wall thickness without an increase in mass or diastolic volume) categories irrespective of EF. The LV remodeling data from the three increased afterload studies22-24 overlap with the RV data (Fig. 4). Thus, in response to increased afterload, there is no obvious difference in structural remodeling between the RV and the LV.

Table 1.

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging data from 5 controls and 18 pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) patients

| Category | mPAP, mmHg | RVeDV, mL | RVEF, % | RVth, cm | RV mass, g |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls (n = 5) | 18 ± 5 | 87 ± 25 | 56 ± 3 | 0.34 ± 0.05 | 28 ± 7 |

| ConCmpHty (n = 4) | 78 ± 12* | 141 ± 20 | 48 ± 1 | 1.0 ± 0.2* | 142 ± 24* |

| ConFailHty (n = 7) | 60 ± 6* | 133 ± 11 | 29 ± 3* | 0.86 ± 0.07* | 100 ± 12* |

| EccCmpHty (n = 2) | 59 ± 12* | 182 ± 64 | 41 ± 0 | 0.55 ± 0.05 | 152 ± 44* |

| EccFailHty (n = 3) | 51 ± 5* | 149 ± 27 | 33 ± 3* | 0.60 ± 0 | 89 ± 12* |

| Fail, concentric remodeling (n = 2) | 51 ± 6* | 98 ± 18 | 34 ± 1* | 0.85 ± 0.15* | 50 ± 4 |

Data are mean ± standard deviation. Hypertrophy (Hty): right ventricle (RV) mass > mean + 2 SD from normal values (>56 g); concentric (Con) Hty: RV thickness (RVth) of ≥.70 cm; eccentric (Ecc) Hty: RVth of <.70 cm; RV failure (Fail): ejection fraction of <40%. Controls were 3 idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy and 2 cardiac transplant patients (2 women, 3 men; age: 47 ± 12 years); PAH patients were 11 women and 7 men (age: 37 ± 10 years). The data in Table 1 were collected under a University of Colorado Institutional Review Board–approved protocol conforming with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all patients provided written consent. mPAP: mean pulmonary arterial pressure; RVeDV: right ventricular end-diastolic volume; RVEF: RV ejection fraction.

P < 0.050 vs. controls.

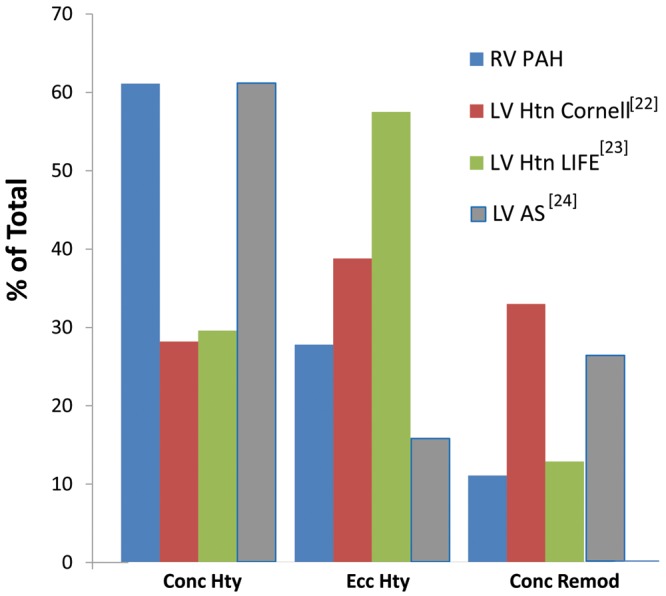

Figure 4.

Increased afterload produces diverse structural phenotypes in both the left ventricle (LV) and the right ventricle (RV). Data in Table 1 and from Koren et al.,22 Gerdts et al.,23 and Dweck et al.24 are categorized as concentric hypertrophy (Conc Hty; increased wall thickness and mass, no increase in end-diastolic volume), eccentric hypertrophy (Ecc Hty; increased diastolic volume and mass, no increase in wall thickness), or concentric remodeling (Conc Remod; increased wall thickness without an increase in mass or diastolic volume) irrespective of ejection fraction. PAH: pulmonary arterial hypertension; Htn: hypertension; AS: aortic stenosis.

Adrenergic mechanisms in RVF due to PAH: comparison to failing LV or RV in HFrEF

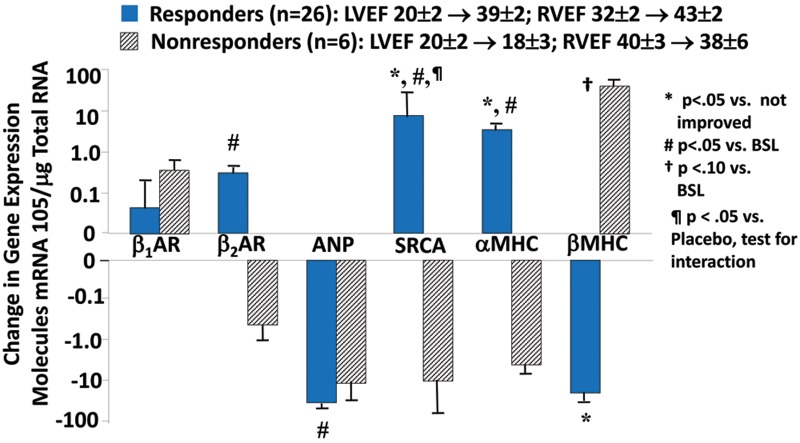

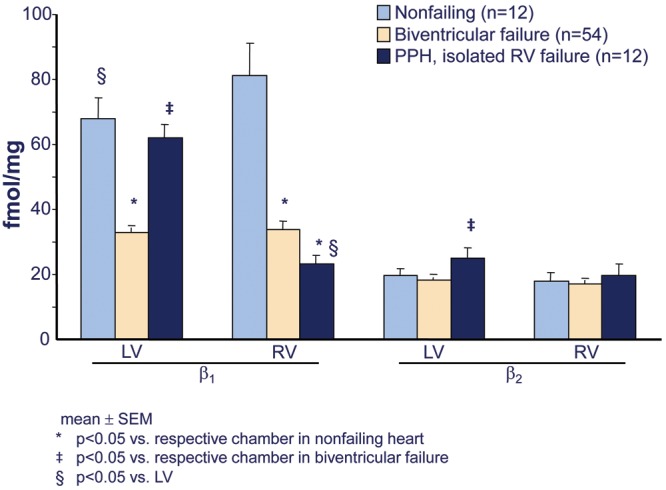

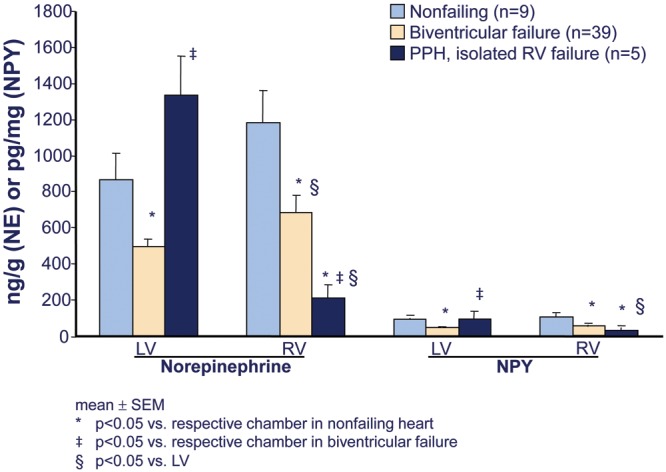

Similar to the failing LV in HFrEF, the RV in PAH is adrenergically activated, to approximately the same extent.13 As a consequence of this activation, RV β1-ARs in PAH are downregulated, to a similar degree as in failing LV or RV in HFrEF (Fig. 5).25 Downregulation of β1-ARs in the myocardium is a biosensor of exposure to excessive adrenergic stimulation.11 Another biomarker of chronic adrenergic activation in human ventricular myocardium is norepinephrine (NE) depletion, resulting from depletion of neuronal stores.11 Levels of both NE and the adrenergic cotransmitter neuropeptide Y are decreased in failing RVs of PAH hearts, again similar to failing RVs and LVs explanted from end-stage HFrEF patients (Fig. 6).25 In contrast to the changes in failing RVs, in the LVs of PAH hearts explanted at the time of heart-lung transplantation there is no downregulation of β1-ARs (Fig. 5) or depletion of adrenergic neurotransmitters (Fig. 6).25 Therefore, in RVs failing as result of PAH, (1) adrenergic activation and its biologic signal transduction consequences are similar to those in LVs and RVs failing as a result of dilated cardiomyopathies and HFrEF and (2) adrenergic activation in PAH RVs is chamber specific,25 meaning that it occurs only in the chamber that is failing.

Figure 5.

Chamber-specific downregulation of β1-adrenergic receptors in failing right ventricles (RVs) from patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). Shown are β1- and β2-adrenergic receptor densities in crude myocardial membranes prepared from ventricular free wall 1-g tissue aliquots of nonfailing organ donor controls with normal left ventricular ejection fractions whose hearts could be placed for transplantation, idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy with biventricular failure hearts removed from transplant recipients, and hearts removed from heart-lung transplant recipients who had PAH and from primary or idiopathic pulmonary hypertension (PPH). Adapted from data in Bristow et al.25 PPH: patients with PAH; LV: left ventricle.

Figure 6.

Chamber-specific norepinephrine (NE) and neuropeptide Y (NPY) depletion in failing right ventricles (RVs) from patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). Shown are ventricular free wall tissue NE and NPY levels from a subset of hearts described in Figure 5 (adapted from data in Bristow et al.25). PPH: patients with PAH; LV: left ventricle.

As in HFrEF, the renin angiotensin system (RAS) is both systemically26,27 and RV locally27 activated in PAH. In response to myocardial stress, adrenergic activation and upregulation of RAS are integrated, in part by β1-AR stimulation of renin release in the kidney16,28 and prejunctional angiotensin II type 1 receptor (AT1R) stimulation of NE release in the heart.29 Consequently, it is not surprising that in PAH the failing RV undergoes chamber-specific downregulation of AT1Rs, to a degree present in failing RVs or LVs from HFrEF hearts.27 Gene expression of myocardial AT1Rs is under β1-AR signaling control30 as well as control by angiotensin II,31 and thus decreased AT1R density is a biomarker of increased RAS activity. Unlike for adrenergic activation, there is also an important systemic component of RAS activation, and the nonfailing LV in PAH hearts exhibits upregulation of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) 1.27 As for adrenergic activation, upregulation of the RAS in the PAH heart likely has both adaptive and maladaptive features. For example, patients who are homozygous for the ACE deletion genotype, which is associated with higher ACE activity, have better RV function with the same level of pulmonary hypertension than patients with insertion genotypes.32

The PAH-failing RV exhibits additional changes in gene expression that are similar to those in failing RVs and LVs from HFrEF hearts (Fig. 7).33 These include upregulation of the fetal genes β-myosin heavy chain and atrial natriuretic peptide and downregulation of the adult genes α-myosin heavy chain and SR Ca2+ ATPase (SRCA).33,34 These four genes form the basis of the so-called fetal gene program, whose changes constitute a molecular signature of pathologic hypertrophy and myocardial failure, and all are under β1-AR regulatory control via PKA-independent signaling that includes Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II.11,19

Figure 7.

Chamber-specific downregulation in gene expression of β1-adrenergic receptors (β1-ARs) and α-myosin heavy chain (αMHC) and upregulation of atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) and β-myosin heavy chain (βMHC) in failing right ventricles (RVs) from patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). Shown is messenger RNA (left upper and lower panels) and β-AR protein expression (right upper panel) from intact hearts measured, respectively, by quantitative polymerase chain reaction and radioligand binding in endomyocardial biopsy samples from controls without heart failure (nonfailing), patients with PAH (PPH), and idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy (IDC) hearts. Adapted from data in Lowes et al.33 NF: nonfailing; SRCA: sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase.

Could an antiadrenergic treatment be effective in RVF due to PAH?

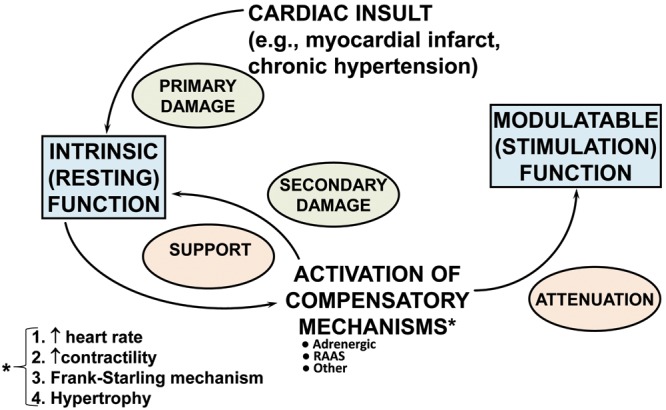

In PAH12 as well as in biventricular failure due to HFrEF,35,36 a biomarker of cardiac adrenergic activation, systemic plasma NE, which mostly originates from cardiac spillover,37 is directly related to increased mortality. Antiadrenergic therapy in the form of β1- or β1/β2-AR blockade partially reverses the structural and molecular remodeling abnormalities in failing LVs and RVs from HFrEF hearts.10,14,38-41 The failing, remodeled HFrEF RV clearly has a reverse-remodeling14 response to β-blocker therapy that is similar to the LV, as shown in a phase 2 placebo-controlled study we performed with carvedilol (Fig. 8).38,39 In Figure 9 it can seen that in HFrEF due to idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy, β-blocker therapy with either carvedilol or metoprolol tartrate markedly improves LVEF and RVEF in ∼80% of the treated patients.34 In patients responding to β-blockade, compared with nonresponders this reverse remodeling effect is associated with a partial reversal in the fetal gene program in endomyocardial myocardial biopsy samples obtained from the interventricular septum, with an increase in pretreatment downregulated SRCA and α-myosin heavy chain and a decrease in pretreatment upregulated β-myosin heavy chain.34 More importantly, these salutary structural and molecular effects are associated with moderate improvements in survival and important morbidity end points, such as hospitalizations.11 In addition, in PAH animal models β-blockers clearly have beneficial effects.42-44 Why, then, has there not been an attempt to develop an antiadrenergic therapeutic strategy in PAH, where the status of the RV function is a major determinant of outcome?45 The reasons are that even slow, gradual withdrawal of adrenergic support to the failing RV in PAH is difficult and may be accompanied by depression of RV function and reflex vasoconstriction, and additionally inhibition of vascular β2-ARs could exacerbate pulmonary hypertension. These observations are supported by anecdotal cases in portopulmonary hypertension of marked deterioration in cardiac function and clinical condition when β-blockers have been initiated46 or clinical improvement when β-blockers have been withdrawn.47 These reports are similar to the early skepticism regarding the use of β-blockers in HFrEF.11 Similar to the earlier reports in HFrEF, the initiating dose of β-blockade was higher46 than what has been used successfully in biventricular failure or than what is recommended in guidelines or on product labels, and the withdrawal study47 was conducted in patients treated with β-blockers that are not well tolerated (propranolol)11 or that have not been used (atenolol) in HFrEF. Certainly in HFrEF, patients can have advanced heart failure and LV dysfunction to the point where β-blockers do more harm than good, for example, in the majority of patients with New York Heart Association (NYHA) class IV HFrEF.48,49 However, the vast majority of class III and some class IV HFrEF patients can tolerate β-blockade as described in prescribing information, starting with very low doses (e.g., carvedilol at 3.125 mg twice a day [b.i.d.] or metoprolol succinate at 12.5 mg/d) and slowly uptitrating to target amounts over a 2–3 month period. In PAH, there is a recent report of β-blockers being tolerated by a subset of moderate-severe PAH patients with comorbidities for which β-blockers were indicated,50 so in theory some PAH patients can tolerate β-blockade. Although there are no published reports of RV function or heart failure clinical status improving following administration of β-blockers to human subjects with PAH, a small phase 2 trial is being conducted with carvedilol using a starting dose of 3.125 mg b.i.d. and an apparent target dose of 6.25 mg b.i.d.51

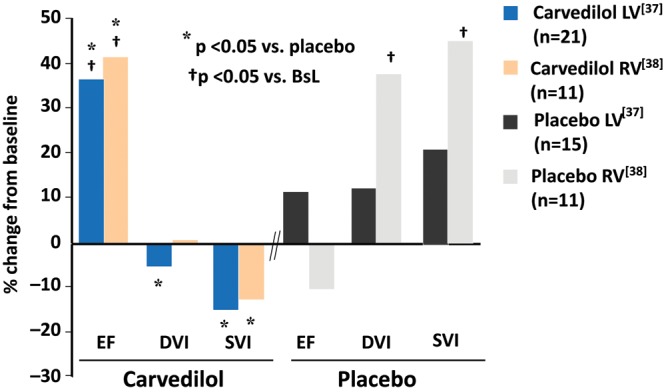

Figure 8.

Carvedilol produces similar reverse structural remodeling effects in the right ventricle (RV) and the left ventricle (LV) of patients with heart failure with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction and biventricular dysfunction. Shown is the effect of carvedilol versus placebo on radionuclide-measured ejection fraction (EF), diastolic volume index (DVI), and systolic volume index (SVI) as percent change from baseline after 4 months of treatment (adapted from data in Hasking et al.37 [LV] and Quaife et al.38 [RV]). All patients with RV also had LV measurements; RV volumes could not be measured for technical reasons in 14 patients. BsL: baseline.

Figure 9.

β-Blockade produces a partial reversal in ventricular myocardial gene expression abnormalities in idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy (IDC) patients with heart failure with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction who have a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) increase at 6 months by ≥5 EF units (responders) compared with nonresponders (LVEF change of <5 EF units). Changes from baseline in myocardial gene expression were measured by quantitative polymerase chain reaction in distal right ventricular (RV) septal endomyocardial biopsy samples from patients with IDC treated for 6 months with carvedilol or metoprolol tartrate (adapted from data in Lowes et al.34). SRCA: sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase; BSL: baseline. Other abbreviations are as in Figure 7. LVEF and right ventricular ejection fraction (RVEF) data are in EF units (fraction × 100).

There is an approach that could theoretically make it easier and potentially safer to administer β-blocking agents to moderate-severe PAH patients, which was developed to initiate in HFrEF patients with severe heart failure who have NYHA class IV and/or are dependent on inotropic support. This is the simultaneous administration of a positive inotropic agent that acts beyond the level of β-receptor blockade,52-54 which results in no attenuation of pharmacologic inotropic support to the heart54 and an apparent full therapeutic response to β-blockade.52 In addition, as in HFrEF55 inotropic support to the failing RV in PAH56 reduces systemic adrenergic stimulation. The inotropic agents used in the HFrEF studies are type 3 phosphodiesterase inhibitors, which are vasodilators in addition to being positive inotropes and lusitropes and therefore should be well tolerated by PAH patients. The safety of this combination has been demonstrated in a large advanced HFrEF clinical trial that did not demonstrate evidence of efficacy in the entire cohort, despite having evidence of benefit in various subgroups that had more severe LV dysfunction.57 The recent discovery of a polymorphism in the PDE3A gene that could affect efficacy58 adds further interest to this possible approach. In addition, there are other positive inotropic agents in clinical development that do not act within the β-adrenergic signaling pathway that could also be used in a β-blocker-positive inotrope combination. Finally, although digoxin has been shown to have inotropic activity in the failing RV in PAH,56 it should be used with caution in this setting because of its narrow therapeutic index, and levels should be kept <1.2 ng/mL.59

Summary

Compared with failing LVs in HFrEF, the hypertrophied RV in PAH exhibits similar structural/geometric remodeling responses to increased afterload, nearly identical levels of adrenergic activation, and similar molecular phenotypes. Compared with the HFrEF failing RV, the remodeled RV in PAH exhibits nearly identical biomarker evidence of adrenergic activation and molecular phenotypes. Antiadrenergic therapy by β-blockade can partially reverse remodeling of both the structural/geometric phenotype and the molecular phenotype in HFrEF LVs and RVs, suggesting that a similar beneficial response could be achieved in PAH RVs.

Source of Support: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) “Clinical Heart and Heart-Lung Transplantation” project grant (E. Stinson, principal investigator; MRB, project leader 1983–1988); NHLBI 1R01 HL 48013, 2R01 48013, 3R01 48013, and 1R01 HL616401 (MRB, principal investigator); Leducq Transatlantic Networks of Excellence FLQ-06 CVD 02 (MRB, core member/principal investigator).

Conflict of Interest: MRB is an officer and director of and holds equity in ARCA Biopharma, a biotechnology company developing pharmacogenetically targeted therapies for arrhythmias and heart failure. RAQ: none declared.

References

- 1.Barst RJ, Rubin LJ, Long WA, McGoon MD, Rich S, Badesch DB, Groves BM, et al.; Primary Pulmonary Hypertension Study Group. A comparison of continuous intravenous epoprostenol (prostacyclin) with conventional therapy for primary pulmonary hypertension. N Engl J Med 1996;334(5):296–301. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Provencher S, Sitbon O, Simonneau G. Treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension with bosentan: from pathophysiology to clinical evidence. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2005;6(8):1337–1348. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Barst RJ. A review of pulmonary arterial hypertension: role of ambrisentan. Vasc Health Risk Manag 2007;3(1):11–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Croom KF, Curran MP. Sildenafil: a review of its use in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Drugs 2008;68(3):383–397. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Rosenzweig EB. Tadalafil for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2010;11(1):127–132. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Seferian A, Simonneau G. Therapies for pulmonary arterial hypertension: where are we today, where do we go tomorrow? Eur Respir Rev 2013;22(129):217–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Vonk Noordegraaf A, Galiè N. The role of the right ventricle in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir Rev 2011;20(122):243–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Rich S. Right ventricular adaptation and maladaptation in chronic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Cardiol Clin 2012;30(2):257–269. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Kaye D, Esler M. Sympathetic neuronal regulation of the heart in aging and heart failure. Cardiovasc Res 2005;66(2):256–264. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Mann DL, Bristow MR. Mechanisms and models in heart failure: the biomechanical model and beyond. Circulation 2005;111(21):2837–2849. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Bristow MR. Treatment of chronic heart failure with β-adrenergic receptor antagonists: a convergence of receptor pharmacology and clinical cardiology. Circ Res 2011;109(10):1176–1194. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Nootens M, Kaufmann E, Rector T, Toher C, Judd D, Francis GS, Rich S. Neurohormonal activation in patients with right ventricular failure from pulmonary hypertension: relation to hemodynamic variables and endothelin levels. J Am Coll Cardiol 1995;26(7):1581–1585. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Mak S, Witte KK, Al-Hesayen A, Granton JJ, Parker JD. Cardiac sympathetic activation in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2012;302(10):R1153–R1157. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Eichhorn EJ, Bristow MR. Medical therapy can improve the biologic properties of the chronically failing heart: a new era in the treatment of heart failure. Circulation 1996;94(9):2285–2296. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Bristow MR, Gilbert EM. Improvement in cardiac myocyte function by biologic effects of medical therapy: a new concept in the treatment of heart failure. Eur Heart J 1995;16(suppl. F):20–31. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.McLeod AA, Brown JE, Kuhn C, Kitchell BB, Sedor FA, Williams RS, Shand DG. Differentiation of hemodynamic, humoral and metabolic responses to β1- and β2-adrenergic stimulation in man using atenolol and propranolol. Circulation 1983;67(5):1076–1084. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Mouw D, Bonjour JP, Malvin RL, Vander A. Central action of angiotensin in stimulating ADH release. Am J Physiol 1971;220(1):239–242. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Waspe LE, Ordahl CP, Simpson PC. The cardiac β-myosin heavy chain isogene is induced selectively in α1-adrenergic receptor–stimulated hypertrophy of cultured rat heart myocytes. J Clin Invest 1990;85(4):1206–1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Sucharov CC, Mariner PD, Nunley KR, Long CS, Leinwand LA, Bristow MR. A β1-adrenergic receptor, CaM kinase II dependent pathway mediates cardiac myocyte fetal gene induction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2006;291(3):H1299–H1308. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Buckberg GD. The ventricular septum: the lion of right ventricular function, and its impact on right ventricular restoration. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2006;29(suppl. 1):S272–S278. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Quaife RA, Lynch D, Badesch DB, Voelkel NF, Lowes BD, Robertson AD, Bristow MR. Right ventricular phenotypic characteristics in subjects with primary pulmonary hypertension or idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. J Card Fail 1999;5(1):46–54. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Koren MJ, Devereux RB, Casale PN, Savage DD, Laragh JH. Relation of left ventricular mass and geometry to morbidity and mortality in uncomplicated essential hypertension. Ann Intern Med 1991;114(5):345–352. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Gerdts E, Cramariuc D, de Simone G, Wachtell K, Dahlöf B, Devereux RB. Impact of left ventricular geometry on prognosis in hypertensive patients with left ventricular hypertrophy (the LIFE study). Eur J Echocardiogr 2008;9(6):809–815. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Dweck MR, Joshi S, Murigu T, Gulati A, Alpendurada F, Jabbour A, Maceira A, et al. Left ventricular remodeling and hypertrophy in patients with aortic stenosis: insights from cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2012;14:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Bristow MR, Minobe W, Rasmussen R, Larrabee P, Skerl L, Klein JW, Anderson FL, et al. β-Adrenergic neuroeffector abnormalities in the failing human heart are produced by local, rather than systemic mechanisms. J Clin Invest 1992;89(3):803–815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.de Man FS, Tu L, Handoko ML, Rain S, Ruiter G, François C, Schalij I, et al. Dysregulated renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system contributes to pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012;186(8):780–789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Zisman LS, Asano K, Dutcher DL, Ferdensi A, Robertson AD, Jenkin M, Bush EW, Bohlmeyer T, Perryman MB, Bristow MR. Differential regulation of cardiac angiotensin converting enzyme binding sites and AT1 receptor density in the failing human heart. Circulation 1998;98(17):1735–1741. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Weber F, Brodde OE, Anlauf M, Bock KD. Subclassification of human beta-adrenergic receptors mediating renin release. Clin Exp Hypertens A 1983;5(2):225–238. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Münch G, Kurz T, Urlbauer T, Seyfarth M, Richardt G. Differential presynaptic modulation of noradrenaline release in human atrial tissue in normoxia and anoxia. Br J Pharmacol 1996;118(7):1855–1861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Dockstader K, Nunley K, Medway AM, Nelson P, Liggett S, Bristow MR, Sucharov CC. Analysis of temporal expression of mRNAs and miRNAs in Arg- and Gly389 polymorphic variants of the β1-adrenergic receptor. Physiol Genomics 2011;43(23):1294–1306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Kato M, Egashira K, Takeshita A. Cardiac angiotensin II receptors are downregulated by chronic angiotensin II infusion in rats. Jpn J Pharmacol 2000;84(1):75–77. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Abraham WT, Raynolds MV, Badesch DB, Wynne KM, Groves BM, Roden RL, Robertson AD, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme DD in patients with primary pulmonary hypertension: increased frequency and association with preserved hemodynamics. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst 2003;4(1):27–30. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Lowes BD, Minobe WA, Abraham WT, Rizeq MN, Bohlmeyer TJ, Quaife RA, Roden RL, et al. Changes in gene expression in the intact human heart: down-regulation of α-myosin heavy chain in hypertrophied, failing ventricular myocardium. J Clin Invest 1997;100(9):2315–2324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Lowes BD, Gilbert EM, Abraham WT, Minobe WA, Larrabee P, Ferguson D, Wolfel EE, et al. Myocardial gene expression in dilated cardiomyopathy treated with beta-blocking agents. N Engl J Med 2002;346(18):1357–1365. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Cohn JN, Levine TB, Olivari MT, Garberg V, Lura D, Francis GS, Simon AB, Rector T. Plasma norepinephrine as a guide to prognosis in patients with chronic congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med 1984;311(13):819–823. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Bristow MR, Krause-Steinrauf H, Nuzzo R, Liang CS, Lindenfeld J, Lowes BD, Hattler B, et al. Effect of baseline or changes in adrenergic activity on clinical outcomes in the beta-blocker evaluation of survival trial (BEST). Circulation 2004;110(11):1437–1442. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Hasking GJ, Esler MD, Jennings GL, Burton D, Johns JA, Korner PI. Norepinephrine spillover to plasma in patients with congestive heart failure: evidence of increased overall and cardiorenal sympathetic nervous activity. Circulation 1986;73(4):615–621. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Quaife RA, Gilbert EM, Christian PE, Datz FL, Mealey PC, Volkman K, Olsen SL, Bristow MR. Effects of carvedilol on systolic and diastolic left ventricular performance in idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol 1996;78(7):779–784. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Quaife RA, Christian PE, Gilbert EM, Datz FL, Volkman K, Bristow MR. Effects of carvedilol on right ventricular function in chronic heart failure. Am J Cardiol 1998;81(2):247–250. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Kao DP, Lowes BD, Gilbert EM, Minobe W, Epperson LE, Meyer L, Ferguson D, et al. Therapeutic molecular phenotype of β-blocker–associated reverse-remodeling in nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2015 8(2):270–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Kao DP, Zolty R, Gilbert EM, Lowes BD, Bristow MR. Myocardial gene expression associated with right- and left-ventricular remodeling with beta-blockade in idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. J Cardiac Failure 2012;18(8):S33–S34.

- 42.Voelkel NF, McMurtry IF, Reeves JT. Chronic propranolol treatment blunts right ventricular hypertrophy in rats at high altitude. J Appl Physiol 1980;48(3):473–478. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Bogaard HJ, Natarajan R, Mizuno S, Abbate A, Chang PJ, Chau VQ, Hoke NN, et al. Adrenergic receptor blockade reverses right heart remodeling and dysfunction in pulmonary hypertensive rats. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010;182(5):652–660. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.de Man FS, Handoko ML, van Ballegoij JJ, Schalij I, Bogaards SJ, Postmus PE, van der Velden J, et al. Bisoprolol delays progression towards right heart failure in experimental pulmonary hypertension. Circ Heart Fail 2012;5(1):97–105. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.D’Alonzo GE, Barst RJ, Ayres SM, Bergofsky EH, Brundage BH, Detre KM, Fishman AP, et al. Survival in patients with primary pulmonary hypertension: results from a national prospective registry. Ann Intern Med 1991;115(5):343–349. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Peacock A, Ross K. Pulmonary hypertension: a contraindication to the use of β-adrenoceptor blocking agents. Thorax 2010;65(5):454–455. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Provencher S, Herve P, Jaïs X, Lebrec D, Humbert M, Simonneau G, Sitbon O. Deleterious effects of β-blockers on exercise capacity and hemodynamics in patients with portopulmonary hypertension. Gastroenterology 2006;130(1):120–126. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Krum H, Sackner-Bernstein JD, Goldsmith RL, Kukin ML, Schwartz B, Penn J, Medina N, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the long-term efficacy of carvedilol in patients with severe chronic heart failure. Circulation 1995;92(6):1499–1506. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Anderson JL, Krause-Steinrauf H, Goldman S, Clemson BS, Domanski MJ, Hager WD, Murray DR, et al.; β-Blocker Evaluation of Survival Trial (BEST) Investigators. Failure of benefit and early hazard of bucindolol for class IV heart failure. J Card Fail 2003;9(4):266–277. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.So PP, Davies RA, Chandy G, Stewart D, Beanlands RS, Haddad H, Pugliese C, Mielniczuk LM. Usefulness of beta-blocker therapy and outcomes in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Cardiol 2012;109(10):1504–1509. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Carvedilol PAH: a pilot study of efficacy and safety. ClinicalTrials.gov. Accessed June 29, 2015. http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02120339?term=beta+blockers+pulmonary+hypertension&rank=1.

- 52.Shakar SF, Abraham WT, Gilbert EM, Robertson AD, Lowes BD, Ferguson DA, Bristow MR. Combined oral positive inotropic and beta-blocker therapy for the treatment of refractory class IV heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 1998;31(6):1336–1340. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Lowes BD, Tsvetkova T, Eichhorn EJ, Gilbert EM, Bristow MR. Milrinone vs. dobutamine in heart failure subjects treated chronically with carvedilol. Int J Cardiol 2001;81(2–3):141–149. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Metra M, Nodari S, D’Aloia, Robertson AD, Bristow MR, Dei Cas L. Beta-blocker therapy influences the hemodynamic response to intoropic agents in patients with heart failure: a randomized comparison of dobutamine and enoximone before and after chronic treatment with metoprolol or carvedilol. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002;40(7):1248–1258. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 55.Port JD, Bristow MR. Altered beta-adrenergic receptor gene regulation and signaling in chronic heart failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2001;33:887–905. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.Rich S, Seidlitz M, Dodin E, Osimani D, Judd D, Genthner D, McLaughlin V, Francis G. The short-term effects of digoxin in patients with right ventricular dysfunction from pulmonary hypertension. Chest 1998;114(3):787–792. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57.Metra M, Eichhorn E, Abraham WT, Linseman J, Böhm M, Corbalan R, DeMets D, et al.; ESSENTIAL Investigators. Effects of low-dose oral enoximone administration on mortality, morbidity and exercise capacity in patients with advanced heart failure: the randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel group ESSENTIAL trials. Eur Heart J 2009;30(24):3015–3026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Bristow MR, Taylor MR, Slavov D, Nelson P, Nunley K, Medway AM, Sucharov CC. A polymorphism in the PDE3A gene promoter that prevents cAMP-induced increases in transcriptional activity, and may protect against PDE3A inhibitor drug tolerance. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;55:A20.

- 59.Rathore SS, Curtis JP, Wang Y, Bristow MR, Krumholz HM. Serum digoxin concentration and the efficacy of digoxin therapy in the treatment of heart failure: an analysis of the Digitalis Investigation Group (DIG) trial. JAMA 2003;289:871–878. [DOI] [PubMed]